1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a major global health challenge, affecting approximately 64.3 million individuals worldwide and contributing signicantly to hospitalization and premature death [

1]. Acute HF, characterized by the rapid onset or worsening of symptoms, imposes a considerable healthcare burden, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where resources are limited and access to optimal care is constrained [

2,

3].

Non-cardiac comorbidities (NCCs), including diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), obesity, and anaemia, are increasingly recognized as key prognostic determinants of poor outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute HF [4-6]. These comorbidities can exacerbate haemodynamic stress, impair therapeutic response, and complicate clinical management. In high-income countries, large registries such as the ESC-HFA EURObservational Research Programme Heart Failure Long-Term Registry have documented that up to 80% of patients hospitalized with acute HF present with at least one NCC, which is associated with prolonged hospital stay, increased in-hospital mortality, and suboptimal use of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) [

5].

In contrast, data on the burden of NCCs among adult patients with acute HF in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) remain sparse. The region faces a double burden of communicable diseases like human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) and non-communicable diseases such as hypertension and diabetes that may uniquely shape the comorbidity profiles and HF trajectories [

7,

8]. Patients in SSA often present with HF at a younger age, and the distribution of HF phenotypes including HF with reduced ejection fraction (EF) (HFrEF), mildly reduced EF (HFmrEF), and preserved EF (HFpEF), may differ substantially from that seen in high-income countries [9-11].

Given these demographic and epidemiological distinctions, understanding the prevalence and clinical impact of NCCs in SSA is critical for developing context-appropriate strategies to improve outcomes. Furthermore, characterizing NCCs patterns across HF phenotypes may offer valuable insights for risk stratification and personalized treatment. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the prevalence of NCCs and evaluate their association with in-hospital outcomes among adults hospitalized with acute HF in Johannesburg, South Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

This was a cross-sectional observational study conducted at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH), a 1088-bed state-owned tertiary referral healthcare facility in Johannesburg, South Africa between February and November 2023. The baseline characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, and the primary outcomes of the study have been published [

11].

2.2. Study population

We enrolled 406 consecutive adult patients admitted with acute HF, defined according to the 2021 ESC guidelines [

2]. Eligible participants were aged ≥18 years, had New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II-IV symptoms, and elevated N-terminal proB natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). We excluded patients with cardiogenic shock requiring multiple inotropes, acute myocardial infarction with indication for urgent revascularization, systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥160 mmHg (recorded at the time of recruitment) on ≥3 antihypertensive drugs, serum potassium >5.1 mmol/L, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <15 mL/min/1.73 m², or recent HF rehospitalization (

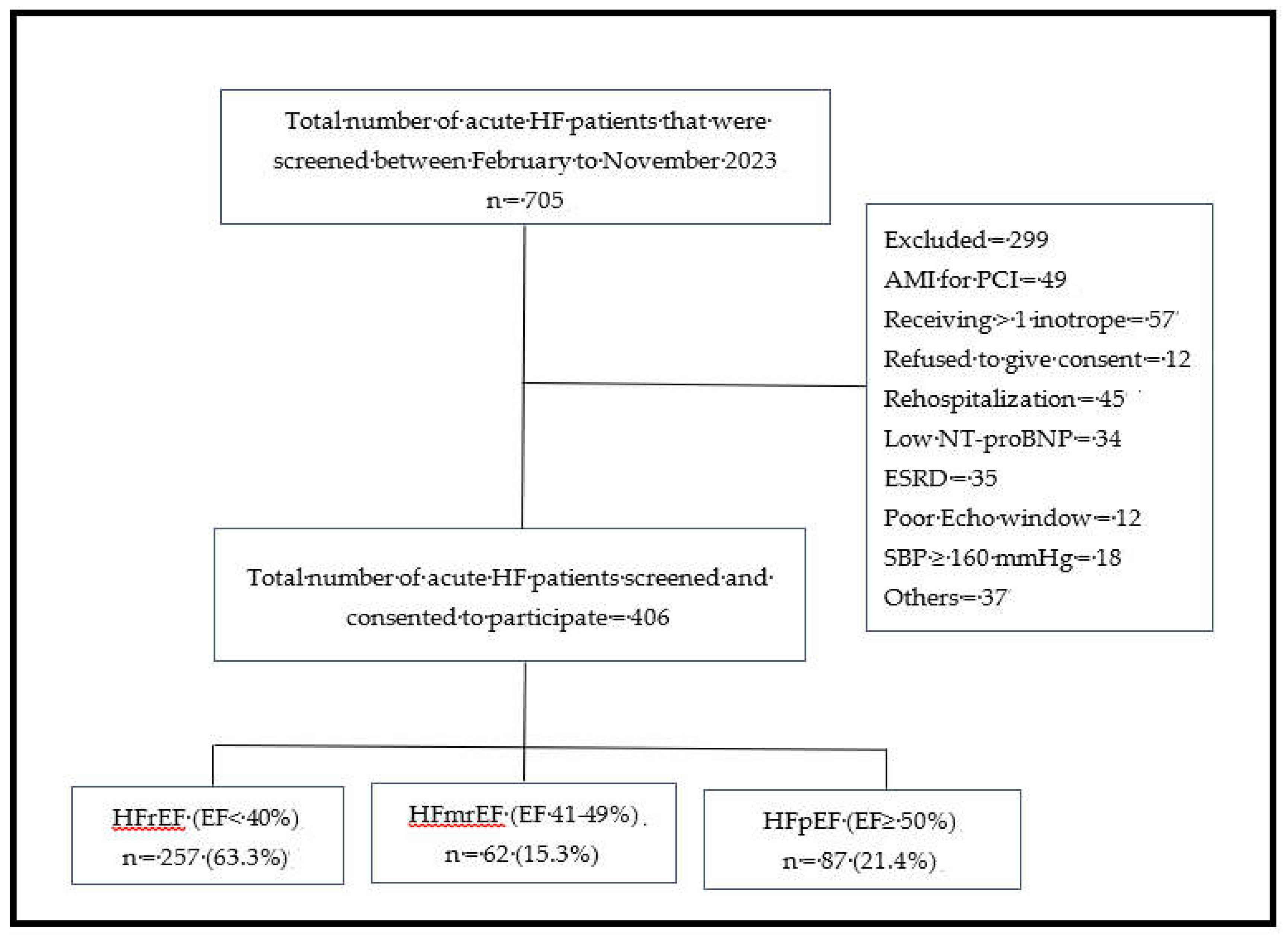

Figure 1).

2.3. Data collection and variables

Baseline sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected on the day of recruitment and entered into a secure REDCap database hosted at the University of the Witwatersrand. Blood pressure and anthropometric measurements were obtained according to standard procedures, body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg/height2 (m²).

2.4. Echocardiographic assessment

All patients underwent 2-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography, including tissue Doppler and speckle tracking, using Vivid

TM iq and Vivid E95 (GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, USA) equipped with 4VC and M5Sc-D transducers and operating at frequencies from 1.5 to 4.0 MHz and 1.4 to 4.6 MHz, respectively. All measurements were performed in accordance with the European and American Society of Echocardiography recommendations [

12]. Left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) was calculated using the modified Simpson’s method and used to classify heart failure (HF) phenotypes as HFrEF (<40%), HFmrEF (40-49%), and HFpEF (≥50%). Measurements were averaged over three to five cardiac cycles in patients with sinus rhythm and five to ten cycles in those with atrial fibrillation.

2.5. Laboratory analysis

Venous blood samples were analyzed at the National Health Laboratory Service. Parameters included serum sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine, NT-proBNP, full blood count, C-reactive protein (CRP), HbA1c, troponin T, and lipid profile. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the CKD-EPI equation.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the distribution of patients with acute HF based on subtypes of heart failure. AMI = Acute myocardial infarction; Echo =Echocardiography; EF = Ejection fraction; ESRD = End stage renal disease; HFmrEF = heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the distribution of patients with acute HF based on subtypes of heart failure. AMI = Acute myocardial infarction; Echo =Echocardiography; EF = Ejection fraction; ESRD = End stage renal disease; HFmrEF = heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

2.6. Non-cardiac comorbidities

We evaluated ten NCCs among the patients admitted with acute HF based on their relevance in HF outcomes. These included; (1) anaemia: haemoglobin <12 g/dL (women), <13 g/dL (men); (2) CKD: eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m²; (3) diabetes mellitus: HbA1c ≥6.5%, documented diagnosis, or medication use; (4) obesity: BMI ≥30 kg/m²; (5) dyslipidaemia: Low density lipoprotein-C (LDL-C) ≥3.37 mmol/L; (6) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); (7) retroviral infection; (8) cancer; (9) thyroid disorders; and (10) systemic lupus erythematosus.

Outcomes. The primary outcomes were all-cause in-hospital mortality and length of hospital stay.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and compared across NCC groups using the Chi-squared (χ²) test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed data were expressed as means ± standard deviations and compared using one-way ANOVA. Non-normally distributed data were reported as median with interquartile ranges (IQR) and compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction.

Associations between NCCs burden and in-hospital outcomes were examined using a two-step analytical approach. First, univariate analyses were performed to assess the crude associations between individual NCC (and comorbidity burden categories) and in-hospital mortality (binary outcome) and length of hospital stay (continuous outcome). Second, multivariable models were constructed to adjust for potential confounders. Variables with p < 0.20 in univariate analyses, as well as key clinically relevant covariates (age, sex, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), and NT-proBNP level were included in the final models. Logistic regression was used for in-hospital mortality and results were expressed as adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In contrast, linear regression was applied to assess predictors of hospital stay duration, with results presented as β coefficients and 95% CI. Model calibration and discrimination were assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and R² statistics for logistic models.

To further assess the robustness of the results, a sensitivity analysis was performed using propensity score-based inverse probability weighting (IPW). Propensity scores were estimated by logistic regression including age, sex, systolic blood pressure, and NT-proBNP as covariates. The inverse of the estimated probabilities was then used to weight each observation to create a pseudo-population in which covariate distributions were balanced between patients with high (≥3 NCCs) and low (<3 NCCs) comorbidity burden. Weighted average treatment effects (ATE) were estimate to evaluate the causal impact of high comorbidity burden on in-hospital mortality and length of hospital stay. Covariate balance before and after weighting was assessed using standardized mean differences, with values <0.1 indicating adequate balance. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA SE version 18.5 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Clinical characteristics

Of the 705 patients screened, 406 were included in the final analysis. Some of the reasons for exclusion included refusal to provide consent (n = 12), end-stage renal disease (n = 35), acute coronary syndrome requiring percutaneous coronary intervention (n = 49), NT-proBNP levels below the diagnostic threshold (n = 34), rehospitalization for HF (n = 45), and cardiogenic shock requiring inotropic support or a left ventricular assist device (n = 57) (

Figure 1). The distribution of the HF phenotypes was as follows: HFrEF 257 (63.3%, 95% CI: 59-68%), HFmrEF 62 (15.3%, 95% CI: 12-19%), and HFpEF 87 (21.4%, 95% CI: 18-26%).

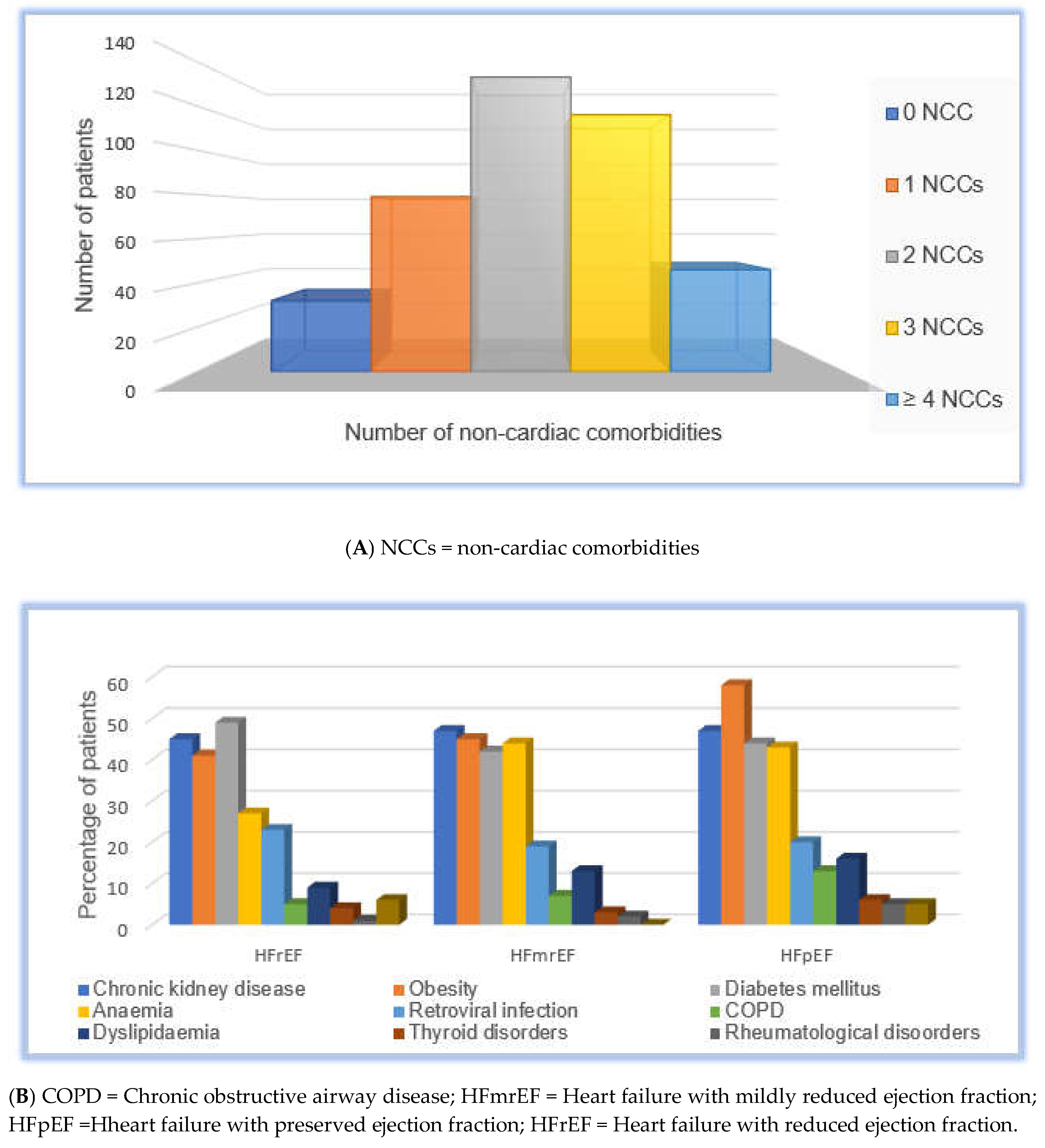

3.2. Distribution and burden of non-cardiac comorbidities

Non-cardiac comorbidities (NCCs) were highly prevalent: diabetes mellitus (47%), chronic kidney disease (CKD; 46%), obesity (45%), anaemia (33%), retroviral infection (21.4%), COPD (6.9%), dyslipidaemia (11%), thyroid disorders (4.2%), systemic lupus erythematosus (2%), and cancers (4.4%). Two hundred and ninety-five (73%) of patients had multimorbidity: 32 patients (7.9%) had no NCCs, 79 (19.5%) had one, 133 (32.8%) had two, 116 (28.6%) had three, and 46 (11.3%) had four or more NCCs. The overall distribution of the NCC burden is shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 2A.

3.3. Non-cardiac comorbidities stratified by heart failure phenotype

The prevalence of individual NCCs across HF phenotypes is summarized in

Table 2 and

Figure 2B. Obesity was significantly more prevalent in patients with HFpEF (61%) and HFmrEF (45.2%) than in those with HFrEF (41%;

p <0.001). Anaemia was also more common in patients with HFmrEF (44%) and HFpEF (43%) than in those with HFrEF (27%;

p = 0.004). In contrast, CKD and diabetes mellitus were similarly distributed across phenotypes (

p = 0.909 and

p = 0.486, respectively). Retroviral infection was present in 23%, 19%, and 20% of patients with HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF, respectively (

p = 0.861). Other comorbidities, including COPD, dyslipidaemia, thyroid disorders, systemic lupus erythematosus, and cancer, showed statistically non- significant differences according to phenotype.

Association between non-cardiac comorbidity burden and clinical profile

As shown in

Table 1, patients with ≥3 NCCs were older (mean age 59.79 ± 15.18 years for 3 NCCs vs. 47.78 ± 16.0 years for no NCCs; p = 0.004), had higher BMI [median 34.95 (31.6-37.9) kg/m² in ≥4 NCCs vs. 22.95 (21.6-26.65) kg/m² in no NCCs; p < 0.001], and worse renal function [median eGFR: 41.5 (30-48) mL/min/1.73m² in ≥4 NCCs vs. 77.5 (65-88.5) mL/min/1.73m² in no NCCs; p < 0.001]. Plasma NT-proBNP levels were numerically higher in patients with more comorbidities but did not differ significantly across groups (p = 0.162). Echocardiographic measures, including LVIDd, left ventricular EF, and LVMI, varied with the comorbidity burden. Patients with ≥4 NCCs had the highest PWTd and preserved right ventricular function, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.462 and P = 0.312, respectively). Left ventricular EF increased across the categories of comorbidity from a median of 25.5% in patients without NCCs to 39% in those with ≥4 NCCs (p = 0.014).

3.4. Medication use and treatment patterns

Loop diuretic use was high across all the groups (>95%). The use of MRAs decreased with increasing comorbidity burden (88% in patients with no NCCs vs. 72% in those with ≥4 NCCs), although this trend was not statistically significant (

p = 0.268). Conversely, calcium channel blocker (CCB) use was significantly higher in patients with ≥4 NCCs (26%) than in those with fewer or no comorbidities (

p = 0.012) (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and comorbidities stratified by number of non-cardiac comorbidities.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and comorbidities stratified by number of non-cardiac comorbidities.

| Variables |

No NCCs

(n = 32) |

1 NCCs

(n = 79) |

2 NCCs

(n = 133) |

3 NCCs

(n = 116) |

≥ 4 NCCs

(n = 46) |

p-value |

| Age, years* |

47.78±16.0 |

52.41±16.51 |

53.88±15.79 |

59.79±15.18 |

55.11±13.25 |

0.004 |

| Female sex, n (%) |

8(25) |

29 (60.3) |

75 (56.4) |

63 (54.3) |

32 (69.6) |

<0.001 |

| NYHA III-IV, n (%) |

17 (53) |

52 (66) |

85 (64) |

74 (64) |

30 (64) |

<0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2! |

22.95 (21.6-26.65) |

26.7 (24.4-29.8) |

28.7 (24.6-34.2) |

30.45 (25.55-35.05) |

34.95 (31.6-37.9) |

<0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg! |

113 (103.5-129.5) |

119 (107-131) |

119 (106-130) |

119 (105-134) |

120 (107-139) |

0.597 |

| DBP, mmHg* |

75.03±15.34 |

75.0±12.51 |

74.0±14.15 |

75.8±14.59 |

75.0v13.24 |

0.561 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL! |

5007 (2244.5-9663.5) |

4528 (2232-11031) |

4605 (1880-9434) |

6578.5 (2050.5 -14479 |

4421 (2126-10368) |

0.162 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L! |

96.5 (76-110.5) |

94 (77-120) |

92 (79-112) |

121.5 (88-154.5) |

138 (106-195) |

<0.001 |

| eGFR, ml/min2! |

77.5 (65-88.5) |

69 (61-90) |

68 (53-87) |

49.5 (36-63.5) |

41.5 (30-48) |

<0.001 |

| CRP, mg/L! |

21.5 (19-72) |

30 (15-69) |

35 (16-69) |

33 (16-580 |

37 (21.5-880 |

0.851 |

| LVEF (%) |

25.5 (19.5-36) |

28 (17-42) |

32 (22-48) |

33.5 (22-48) |

39 (25-57) |

0.014 |

| LAD mm* |

45.19±8.55 |

47.10±7.46 |

47.43±7.07 |

44.93±7.42 |

45.59±8.97 |

0.073 |

| LVIDd, mm* |

57.16±11.09 |

56.44±10.83 |

54.70±11.23 |

54.16±9.45 |

50.89±10.05 |

0.029 |

| PWTd, mm* |

11.69±3.16 |

11.63±2.37 |

12±2.99 |

12.03±2.92 |

12.61±3.50 |

0.462 |

| LVMI, g/m2! |

165.5 (133.5-221) |

147 (123-178) |

157 (130-193) |

151 (126.5-191) |

123 (99-164) |

0.007 |

| RVFAC, %! |

30.5 (21.5-39) |

31 (24-43.5) |

31 (21-42) |

29 (22-43) |

37 (26-44) |

0.312 |

| E/A! |

2.03 (0.93-2.55) |

1.82 (1.18-2.79 |

1.68 (1.09-2.48) |

1.45 (0.85-2.42) |

1.27 (0.87-1.95) |

0.118 |

| E/e’ lateral! |

14.7 (8.14-17.41) |

12.9 (8.9-17.4) |

12 (8.6-17.2) |

12.5 (8.27-18.35) |

13.47 (9.5-20.2) |

0.713 |

| GLS, %! |

-6.2 (-7.3, -4.8) |

-5.3 (-9.9, -3.9) |

-6.5 (-9.5, -4.1) |

-5.6 (-8.9, -4.0) |

-6.4 (-8.5, -3.9) |

0.819 |

| Loop diuretic, n (%) |

31 (97) |

75 (95) |

128 (96) |

113 (97) |

44 (96) |

0.924 |

| ACEIs/ARB, n (%) |

30 (94) |

67 (85) |

113 (85) |

106 (91) |

37 (80) |

0.234 |

| MRA, n (%) |

28 (88) |

66 (84) |

112 (84) |

91 (78) |

33 (72) |

0.268 |

| CCBs, n (%) |

5 (16) |

8 (10) |

9 (7) |

17 (15) |

12 (26) |

0.012 |

| B-blockers, n (%) |

30 (94) |

67 (85) |

118 (89) |

95 (82) |

40 (87) |

0.329 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors, n (%) |

5 (16) |

7 (9) |

15 (11) |

11 (9) |

6 (13) |

0.816 |

| Length of stay, days! |

8 (5-12) |

8 (5-13) |

8 (6-14) |

10 (6.5-15) |

8 (6-150) |

0.229 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) |

0 (0) |

3 (4) |

4 (3) |

4 (3) |

3 (7) |

0.318 |

Figure 2.

(A): Distribution of non-cardiac comorbidity burden. This figure shows the number of non-cardiac comorbidities (NCCs) in the study cohort, grouped into 0, 1, 2, 3, or ≥4 NCCs. (B): Stacked bar chart of individual non-cardiac comorbidities (NCCs) by HF phenotype. This figure shows the prevalence of individual non-cardiac comorbidities by heart failure phenotype. HF phenotypes were categorized as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, mildly reduced ejection fraction, and preserved ejection fraction. NCCs include diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, obesity, anaemia, HIV, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dyslipidaemia, thyroid disorders, systemic lupus erythematosus, and cancer. Each bar represents the proportion of patients with NCC within a phenotype.

Figure 2.

(A): Distribution of non-cardiac comorbidity burden. This figure shows the number of non-cardiac comorbidities (NCCs) in the study cohort, grouped into 0, 1, 2, 3, or ≥4 NCCs. (B): Stacked bar chart of individual non-cardiac comorbidities (NCCs) by HF phenotype. This figure shows the prevalence of individual non-cardiac comorbidities by heart failure phenotype. HF phenotypes were categorized as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, mildly reduced ejection fraction, and preserved ejection fraction. NCCs include diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, obesity, anaemia, HIV, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dyslipidaemia, thyroid disorders, systemic lupus erythematosus, and cancer. Each bar represents the proportion of patients with NCC within a phenotype.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Non-Cardiac Comorbidities by HF Phenotype.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Non-Cardiac Comorbidities by HF Phenotype.

| Variables |

HFrEF

(n = 257) |

HFmrEF

(n = 62) |

HFpEF

(n = 87) |

p-value |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) |

115 (45) |

29 (47) |

41 (47) |

0.909 |

| Obesity, n (%) |

105 (40.9) |

28 (45.2) |

50 (61) |

<0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) |

126 (49) |

26 (42) |

38 (44) |

0.486 |

| Anaemia, n (%) |

69 (27) |

27 (44) |

37 (43) |

0.004 |

| Retroviral infection, n (%) |

58 (23) |

12 (19) |

17 (20) |

0.861 |

| COPD, n (%) |

12 (4.7) |

4 (6.5) |

10 (11.5) |

0.080 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) |

22 (8.7) |

8 (12.90 |

14 (16.1) |

0.122 |

| Thyroid disorders, n (%) |

10 (3.9) |

2 (3.23) |

5 (5.8) |

0.695 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus, n (%) |

3 (1.2) |

1 (1.6) |

4 (4.6) |

0.094 |

| Cancers, n (%) |

14 (5.5) |

0 (0) |

4 (4.6) |

0.173 |

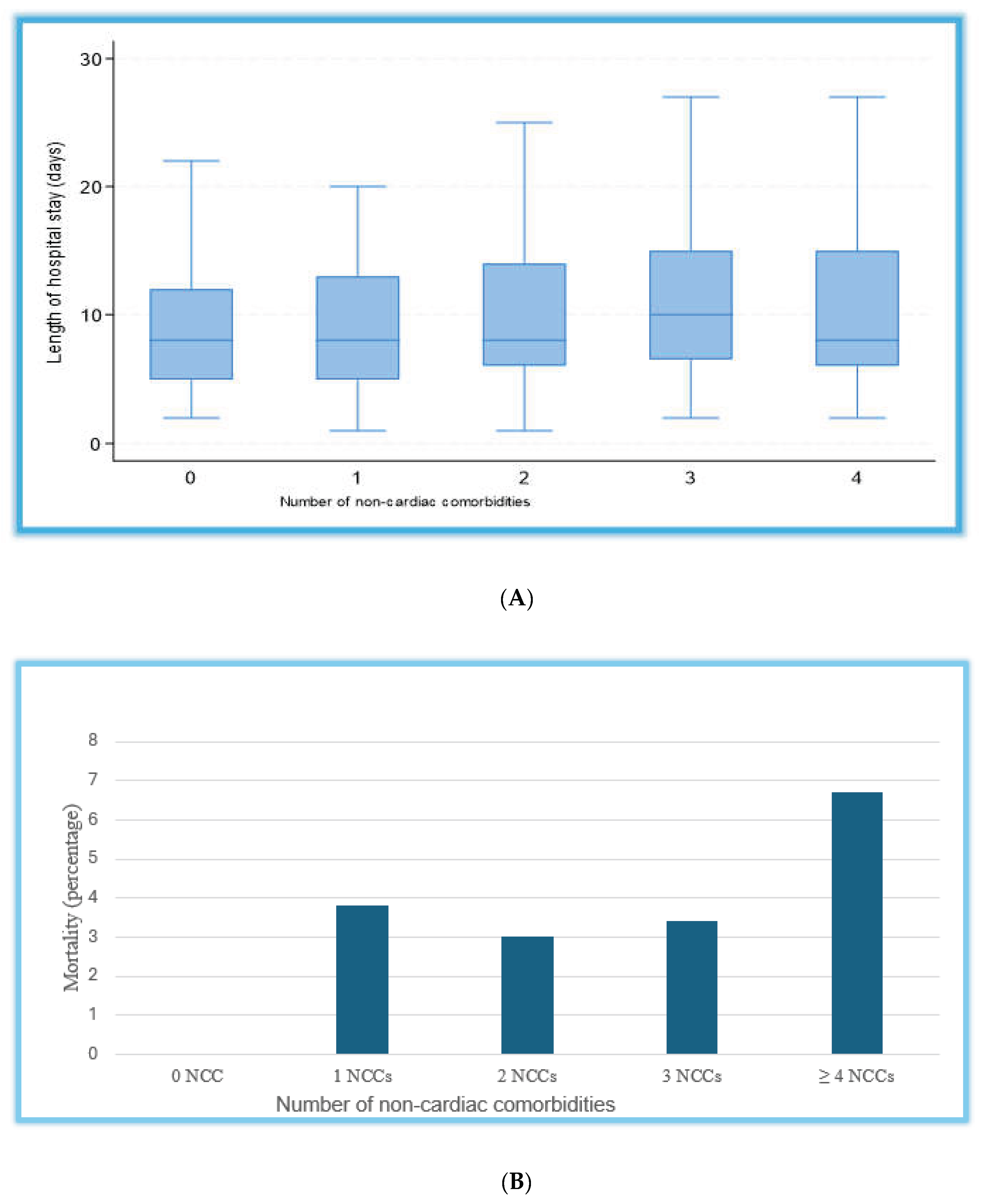

3.5. Length of stay and in-hospital mortality

The overall median length of hospital stay was 8 days (IQR: 5-12), and patients with a higher non-cardiac comorbidity burden tended to have a modestly longer duration of admission (

Figure 3). In univariate analysis, only thyroid disorders and heart rate were significantly associated with the length of hospital stay. In multivariable linear regression analysis, the overall model predicting length of hospital stay was statistically significant (F(17,388) = 2.31, p < 0.001; R² = 0.109). Among individual predictors, the use of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors (RASi) and the presence of thyroid disorders were independently associated with shorter hospital stay (β = -1.84 days, 95% CI: -3.78, -0.12, p = 0.049; β = -4.10 days, 95% CI: -7.75, -0.45, p = 0.028, respectively). In contrast, higher heart rate at admission was associated with prolonged hospitalization (β = +0.05 days per beat per minute, 95% CI: 0.006 to 0.092, p = 0.025). Systolic blood pressure showed a borderline association with shorter stay (β = -0.04 days, 95% CI: −0.083 - 0.004, p = 0.077). Age, sex, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and higher comorbidity burden were not significantly associated with hospital duration after adjustment (Supplementary Table S1).

The all-cause in-hospital mortality was low but increased with the number of NCCs, ranging from 0% in those without NCCs to 7% in patients with four or more NCCs. Specifically, mortality rates were 4% in patients with 1 NCC, 4% in those with 2 NCCs, 3% in those with 3 NCCs, and 7% in those with ≥4 NCCs, with no statistically significant differences between groups (

p = 0.318). These trends are illustrated in

Figure 3B. In a univariate logistic regression, only the SII, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), and NT-proBNP were significantly associated with in-hospital mortality. In multivariable logistic regression analysis (χ²(9) = 24.9, p = 0.003; Pseudo R² = 0.20), higher KCCQ scores and NT-proBNP levels were independently associated with in-hospital mortality. Each one-point increase in KCCQ score was associated with 0.9% higher odds of death (OR 1.009, 95% CI 1.003-1.015, p = 0.005), while each unit increase in NT-proBNP was linked to a small but statistically significant rise in mortality risk (OR 1.00007, 95% CI 1.00002-1.00013, p = 0.014). Other covariates, including age, sex, SBP, diabetes mellitus, CKD, higher non-cardiac comorbidity burden, and RASi use, were not significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (all p > 0.05) (Supplementary Table S2).

Sensitivity analyses of comorbidity burden with in-hospital outcomes

In sensitivity analyses using multivariable and IPW models, a trend toward longer stay was observed among patients with a higher NCC burden, but the association did not reach statistical significance (β = +1.4 days, 95% CI: −0.12–2.9, p = 0.070; ATE = +1.4 days, 95% CI: -0.09-2.91, p = 0.066). Similarly, both the multivariable logistic regression and IPW models demonstrated no significant association between the NCCs and in-hospital mortality (aOR = 2.9, 95% CI: 0.70-11.76, p = 0.142; IPW logit with an ATE = +0.016, 95% CI: -0.03-0.06, p = 0.482) (Supplementary Table S3). The direction and magnitude of these estimates were consistent across analytic approaches, supporting the robustness and internal validity of the observed relationship between multimorbidity and hospital outcomes.

Figure 3.

(A). Boxplot of length of stay by number of non-cardiac comorbidities: This figure shows the distribution of hospital length of stay by non-cardiac comorbidity (NCC) burden. Patients were grouped according to the number of NCCs: 0, 1, 2, 3, and ≥4. The box represents the interquartile range (IQR), the horizontal line indicates the median, and the whiskers denote the range excluding outliers. NCCs = non-cardiac comorbidities. (B). All-cause in-hospital mortality by non-cardiac comorbidities. This figure shows the number of non-cardiac comorbidities (NCCs) in the study cohort, grouped into 0, 1, 2, 3, or ≥4 NCCs. Percentages indicate the mortality in each category.

Figure 3.

(A). Boxplot of length of stay by number of non-cardiac comorbidities: This figure shows the distribution of hospital length of stay by non-cardiac comorbidity (NCC) burden. Patients were grouped according to the number of NCCs: 0, 1, 2, 3, and ≥4. The box represents the interquartile range (IQR), the horizontal line indicates the median, and the whiskers denote the range excluding outliers. NCCs = non-cardiac comorbidities. (B). All-cause in-hospital mortality by non-cardiac comorbidities. This figure shows the number of non-cardiac comorbidities (NCCs) in the study cohort, grouped into 0, 1, 2, 3, or ≥4 NCCs. Percentages indicate the mortality in each category.

4. Discussion

In this single-center observational study of 406 patients hospitalized with acute HF in Johannesburg, South Africa, we observed a substantial burden of NCCs across all HF phenotypes, with more than two-thirds of patients presenting with two or more NCCs. Chronic kidney disease, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and anaemia were the most prevalent comorbidities, reflecting the evolving cardiometabolic profile of HF in sub-Saharan Africa. Lower KCCQ scores and higher NT-proBNP levels were independently associated with increased in-hospital mortality, whereas higher heart rate was linked to prolonged hospitalization. Conversely, the use of RASi and the presence of thyroid disorders were associated with shorter hospital stays.

The clinical course of patients with acute HF is often influenced not only by the underlying cardiac dysfunction but also by a range of precipitating factors noncardiac factors. These NCCS often under-recognized, can significantly complicate management, contributing to longer hospital stays, increased mortality, and challenges in the initiation or up-titration of GDMT [2,4-7]. Our findings are consistent with prior reports showing a high prevalence of NCCs in patients admitted with HF [

4,

6,

13]. In the ESC-HFA EURObservational Long-Term Registry, approximately 80% of patients hospitalized with HF had at least one NCC, and multimorbidity was strongly associated with adverse short- and long-term outcomes [

4]. Similar observations have been reported in Asia and Europe, where 80-85% of patients with acute HF had at least one NCC [

14,

15]. In SSA, the HF comorbidity profiles is uniquely influenced by the double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases. The substantial prevalence of HIV in our cohort, which is often underrepresented in global HF studies, illustrates this distinction [

16,

17]. Similar regional patterns were observed in the INTER-CHF study, which reported higher rates of infectious conditions and anaemia in SSA compared with other regions [

18].

Patients with higher NCC burden in our cohort were older, more often female, and had higher BMI and worse renal function. CKD, anaemia, obesity, and diabetes clustered particularly in HFpEF and HFmrEF phenotypes. This pattern supports emerging pathophysiologic models in which systemic comorbidities drive chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and myocardial fibrosis, processes that are central to the development of diastolic dysfunction and HFpEF [19-23]. Notably, patients with four or more NCCs were significantly less likely to receive GDMT, particularly mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, consistent with prior reports [24-26]. This likely reflects clinical complexity, potential contraindications, and frailty arising from renal dysfunction or hyperkalaemia risk. Real-world data have shown that higher comorbidity burden decreases the likelihood of GDMT intensification, especially in patients with ≥4 comorbidities [

24]. Conversely, the greater use of calcium channel blockers (CCBs) in patients with high NCC likely represents a pragmatic approach targeting hypertension control and symptom management, often at the expense of neurohormonal blockade. In a pooled trials that enrolled patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF, up to 35% of patients were on CCBs, reflecting common practice in multimorbid HF populations [

27].

Interestingly, patients with thyroid disorders in our cohort had significantly shorter hospital stay. This finding contrasts with prior studies, where hypothyroidism and subclinical hyperthyroidism were associated with heightened morbidity and mortality in HF [28-30]. This may reflect the early recognition and management of thyroid disease or the predominance of compensated thyroid states. Thyroid hormones play a significant role in myocardial contractility, vascular tone, and cardiac output; hence, restoration of euthyroidism may facilitate rapid hemodynamic stabilization and alleviation of symptoms during hospitalization [

31,

32]. These results underscore the importance of routine thyroid function assessment and management in HF patients, a frequently underdiagnosed but treatable disorder. Future prospective studies are necessary to elucidate the differential impacts of hypo- and hyperthyroid states, and to assess whether modulation of thyroid hormones can decrease hospitalization duration and enhance recovery in acute HF.

Although crude differences in in-hospital mortality and length of stay were not statistically significant, both outcomes demonstrated a stepwise worsening with increasing NCC burden. This mirrors the global evidence that multimorbidity independently predicts poorer short-term outcomes [33-36]. In SSA, limited access to advanced therapies, specialist care, and fragmented chronic disease management may amplify the impact of high NCC on hospital resources and outcomes [

16,

37]. Lower KCCQ scores were associated with higher in-hospital mortality, reflecting the prognostic importance of patient-reported health status in acute HF. Prior studies have consistently shown that lower KCCQ scores predict rehospitalization and mortality [

38]. Likewise, higher resting heart rate was independently associated with longer hospitalization, consistent with prior research linking tachycardia with greater hemodynamic stress, impaired ventricular efficiency, and worse short-term outcomes in acute HF [

39]. Together, these findings reinforce the clinical importance of integrating objective and patient-reported measures when assessing disease severity and short-term prognosis in patients with acute HF.

Sensitivity analyses using multivariable adjustment and propensity score weighting also showed similar trends, reinforcing the additive impact of multimorbidity on healthcare utilization. While the lack of statistical significance may reflect limited power, exclusion of critically ill patients, and low event rates, the observed patterns are consistent with larger international cohorts, where high comorbidity burden prolongs hospital stay and increases post-discharge readmissions [5,34,40-44]. These findings highlights that, beyond overall comorbidity burden, functional status, neurohormonal modulation, and biomarker indicators of myocardial stress are key determinants of short-term prognosis in patients with acute HF. Hence, integrating multimorbidity assessment and inflammatory profiling into HF care pathways may enhance risk stratification, support personalized management, and guide the development of phenotype-specific HF strategies tailored to the African context.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, as a single-center study conducted at a public tertiary hospital, the findings may not fully represent the comorbidity burden in rural or community settings across SSA, where access to healthcare and disease patterns may differ substantially. Second, the relatively low in-hospital mortality rate may have reduced the statistical power to detect differences across NCC burden categories. Third, the exclusion of patients with severe renal dysfunction, cardiogenic shock, or acute coronary syndromes requiring intervention may underestimate the actual comorbidity burden among critically ill patients. Fourth, the inclusion of diverse HF aetiologies may have introduced heterogeneity, potentially influencing the observed associations between NCCs and HF phenotypes. Finally, as an observational study, causal inference is limited despite adjustment and sensitivity analyses and should be considered as hypothesis generating. Future studies should include consecutive patients with acute HF and provide longitudinal follow-up to better evaluate causal and prognostic relationships between NCCs and outcome across SSA populations.

6. Conclusions

In this single-center cohort of adults hospitalized with acute HF in South Africa, NCCs were highly prevalent, with more than two-thirds of the patients presenting with two or more NCCs. CKD, obesity, diabetes, and anaemia were the most common comorbidities, with obesity and anaemia more common among HFmrEF and HFpEF phenotypes. Although overall in-hospital mortality was low, higher heart rate was independently associated with longer hospitalization, and thyroid disorders and use of RASis were associated with shorter stay. Patients with higher comorbidity burden were older, had worse renal function, and less likely to receive guideline-directed therapies, reflecting the complex interplay among multimorbidity, clinical management, and short-term outcomes.

These findings highlight the importance of systematic assessment of NCCs in acute HF across SSA. Integrating multimorbidity evaluation into routine care may improve risk stratification, guide personalized treatment, and inform context-specific strategies to optimize outcomes. Future multicenter and longitudinal studies are warranted to further clarify the causal relationships between NCCs and outcomes and to develop evidence-based, phenotype-specific HF management models for the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.G.A. and N.T., Methodology, U.G.A, S.N. Software, U.G.A. and C.M., Validation, U.G.A, and N.T., Formal Analysis, U.G.A., Investigation, U.G.A, S.N., Resources, U.G.A, N.T., Data Curation, U.G.A. and C.M., Writing-Original Draft Preparation, U.G.A., Writing-Review & Editing, U.G.A. M.M. N.T., Visualization, U.G.A. S.N. and C.M.; Supervision, N.T. M.M., Project Administration, U.G.A. S.N., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand (Approval no: M220519 and February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Data protection and privacy regulations were strictly observed in capturing, forwarding, processing, and storing of patient data.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript.

aOR Adjusted odds ratio

ATE Average treatment effects

BMI Body mass index

CKD Chronic kidney disease

CMJAH Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital

COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CRP C-reactive proteins

DBP Diastolic blood pressure

eGFR Estimated glomerular filtration rate

EF Ejection fraction

ESC European society of cardiology

GDMT Guideline directed medical therapy

HbA1c Glycated haemoglobin

HFmrEF Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction

HFrEF Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

HFpEF Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

HF Heart failure

HIV Human immunodeficiency virus

IPW Inverse probability weighting

IQR Interquartile range

KCCQ Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

LDL-C Low density lipoprotein-cholesterol

LVIDd Left ventricular internal dimension end-diastole

LVMI Left ventricular mass index

NCCs Non-cardiac comorbidities

NYHA New York Heart Association

NT-proBNP N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide

OR Odds ratio

PWTd Posterior wall thickness in end-diastole

RASi Renin-angiotensin receptor blockers

SSA sub-Saharan Africa

References

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L’H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;118(17):3272-3287.

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Farmakis, D.; Gilard, M.; Heymans, S.; Hoes, A.W.; Jaarsma, T.; Jankowska, E.A,; Lainscak, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; Lyon, A.R.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Mebazaa, A.; Mindham, R.; Muneretto, C.; Francesco, P. M,; Price, S.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Ruschitzka, F.; Kathrine, S. A; ESC Scientific Document Group2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(48):4901.

- Shah, K.S.; Xu, H.; Matsouaka, R.A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Hernandez, A.F.; Devore, A.D.; Yancy, C,W.; Fonarow, G.C. Heart Failure With Preserved, Borderline, and Reduced Ejection Fraction: 5-Year Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(20):2476–2486.

- Chioncel, O.; Benson, L.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Anker, S.D.; Coats, A.J.S.; Filippatos, G.; McDonagh, T.; Margineanu, C.; Mebazaa, A.; Metra, M.; Piepoli, M.F.; Adamo, M.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Ruschitzka, F.; Savarese, G.; Seferovic, P.; Volterrani, M.; Ferrari, R.; Maggioni, A.P.; Lund, L.H. Comprehensive characterization of non-cardiac comorbidities in acute heart failure: an analysis of ESC-HFA EURObservational Research Programme Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023;30(13):1346-1358.

- Savarese, G.; Settergren. C.; Schrage, B.; Thorvaldsen, T.; Löfman, I.; Sartipy, U.; Mellbin, L.; Meyers, A.; Farsani, S.F.; Brueckmann, M.; Brodovicz, K.G.; Vedin, O.; Asselbergs, F.W.; Dahlström, U.; Cosentino, F.; Lund, L, H. Comorbidities and cause-specific outcomes in heart failure across the ejection fraction spectrum: A blueprint for clinical trial design. Int J Cardiol. 2020;313:76-82.

- Streng, K.W., Nauta, J.F.; Hillege, H.L.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.; Lang, C.C.; Metra, M.; Ng, L.L.; Ponikowski, P.; Samani, N.J.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Zannad, F.; Damman, K.; van der Meer, P.; Voors, A.A. Non-cardiac comorbidities in heart failure with reduced, mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol. 2018;271:132-139.

- Mudie, K.; Jin, M.M.; Tan, K.L.; Addo, J.; Dos-Santos-Silva, I.; Quint, J.; Smeeth, L.; Cook, S.; Nitsch, D.; Natamba, B.; Gomez-Olive, F.X.; Ako, A.; Perel, P. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review of large cohort studies. J Glob Health. 2019;9(2):020409.

- Damasceno, A.; Mayosi, B.; Sani, M.; Ogah, O.S.; Mondo, C.; Ojji, D.; Dzudie, A.; Kouam, C.K.; Suliman, A.; Schrueder, N.; Yonga, G.; Ba, S.A.; Maru, F.; Alemayehu, B.; Edwards, C.; Davison, B.A.; Cotter, G.; Sliwa, K. The causes, treatment, and outcome of acute heart failure in 1006 Africans from 9 countries. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1386-1394.

- Dzudie, A.; Hongieh, A.M.; Nkoke, C.; Barche, B.; Damasceno, A.; Edwards, C.; Davison, B.; Cotter, G.; Sliwa, K. THEUS-HF investigators. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of black African heart failure patients with preserved, mid-range, and reduced ejection fraction: a post hoc analysis of the THESUS-HF registry. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8:238–249.

- Ntusi, N.A.B. Cardiovascular disease in HIV infection in South Africa: not just a Western problem. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(12):707–708.

- Adamu, U.G.; Maseko, M.; & Tsabedze, N. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of adults with acute heart failure in a South African teaching hospital. ESC Heart Fail. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Bierig, M.; Devereux, R.B.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Pellikka, P.A.; Picard, M.H.; Roman, M.J.; Seward, J.; Shanewise, J.S.; Solomon, S.D.; Spencer. K.T.; Sutton, M.S.; Stewart, W.J. Chamber Quantification Writing Group; American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee; European Association of Echocardiography. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440-1463.

- Pandey, A.; Vaduganathan, M.; Arora, S.; Qamar, A.; Mentz, R.J.; Shah, S.J.; Chang, P.P.; Russell, S.D.; Rosamond, W.D.; Caughey, M.C. Temporal Trends in Prevalence and Prognostic Implications of Comorbidities Among Patients With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: The ARIC Study Community Surveillance. Circulation. 2020;142(3):230-243.

- Huo, X.; Zhang, L.; Bai, X.; He, G.; Li, J.; Miao, F.; Lu, J.; Liu, J.; Zheng, X.; Li, J. Impact of Non-cardiac Comorbidities on Long-Term Clinical Outcomes and Health Status After Acute Heart Failure in China. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:883737.

- Tomasoni, D.; Vitale, C.; Guidetti, F.; Benson, L.; Braunschweig, F.; Dahlström, U.; Melin, M.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Lund, L.H.; Metra, M.; Savarese, G. The role of multimorbidity in patients with heart failure across the left ventricular ejection fraction spectrum: Data from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024;26(4):854-868.

- Ntsekhe, M.; Damasceno A. Heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2013;24(5):117–123.

- Sliwa, K.; Carrington, M.J.; Klug, E.; Opie, L.; Lee, G.; Ball, J.; Stewart, S. Incidence and characteristics of newly diagnosed heart failure in urban African patients: the Heart of Soweto Study. Heart. 2010;96(14):1201-1206.

- Dokainish, H.; Teo, K.; Zhu, J.; Roy, A.; AlHabib, K.F.; ElSayed, A.; Palileo-Villaneuva, L.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Karaye, K.; Yusoff, K.; Orlandini, A.; Sliwa, K.; Mondo, C.; Lanas, F.; Prabhakaran, D.; Badr, A.; Elmaghawry, M.; Damasceno, A.; Tibazarwa, K.; Belley-Cote, E.; Balasubramanian, K.; Islam, S,.;Yacoub, M.H.; Huffman, M.D.; Harkness, K.; Grinvalds, A.; McKelvie, R.; Bangdiwala, S,I.; Yusuf, S. INTER-CHF Investigators. Global mortality variations in patients with heart failure: results from the International Congestive Heart Failure (INTER-CHF) prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(7):e665-e672.

- Taderegew, M.M.; Wondie, A.; Terefe, T.F.; Tarekegn, T.T.; GebreEyesus, F.A.; Mengist, S.T.; Amlak, B.T.; Emeria, M.S.; Timerga, A.; Zegeye, B.; Anemia and its predictors among chronic kidney disease patients in Sub-Saharan African countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):e0280817.

- Bae, J.P.; Kallenbach, L.; Nelson, D.R.; Lavelle, K.; Winer-Jones, J.P.; Bonafede, M.; Murakami, M. Obesity and metabolic syndrome in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a cross-sectional analysis of the Veradigm Cardiology Registry. BMC Endocr Disord. 2024;24(1):59.

- Morgen, C.S.; Haase, C.L. Oral TK, Schnecke V, Varbo A, Borlaug BA. Obesity, Cardiorenal Comorbidities, and Risk of Hospitalization in Patients with Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023;98(10):1458-1468.

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschöpe, C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(4):263-71.

- Redfield, M.M. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1868-1877.

- Mebazaa, A.; Davison, B.; Chioncel, O.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Diaz, R.; Filippatos, G.; Metra, M.; Ponikowski, P.; Sliwa, K.; Voors, A.A.; Edwards, C.; Novosadova, M.; Takagi, K.; Damasceno, A.; Saidu, H.; Gayat, E,; Pang, P.S.; Celutkiene, J.; Cotter, G. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapies for acute heart failure (STRONG-HF): a multinational, open-label, randomised, trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10367):1938-1952.

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Anand, I.S.; Ge, J.; Lam, C.S.P.; Maggioni, A.P.; Martinez, F.; Packer, M.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Pieske, B.; Redfield, M.M.; Rouleau, J.L.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Zannad, F.; Zile, M.R.; Desai, A.S.; Claggett, B.; Jhund, P.S.; Boytsov, S.A.; Comin-Colet, J.; Cleland, J.; Düngen, H.D.; Goncalvesova, E.; Katova, T.; Kerr, S.J.F.; Lelonek, M.; Merkely, B.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; Zhou, J.; Rizkala, A.R.; Gong, J.; Shi, V.C.; Lefkowitz, M.P. PARAGON-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17):1609-1620.

- McMurray, J.J.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Rizkala, A.R.; Rouleau, J.L.; Shi, V.C.; Solomon, S.D.; Swedberg, K.; Zile, M.R. PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993–1004.

- Matsumoto, S.; Kondo, T.; Yang, M.; Campbell, R.T.; Docherty, K.F.; de Boer, R.A.; Desai, A.S.; Lam, C.S.P.’ Packer, M.; Pitt, B.; Rouleau, J.L.; Vaduganathan, M.; Zannad, F.; Zile, M.R.; Solomon, S.D.; Jhund, P.S.; McMurray, J.J.V. Calcium channel blocker use and outcomes in patients with heart failure and mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25(12):2202-2214.

- Kannan, L.; Shaw, P, A.; Morley, M, P.; Brandimarto, J.; Fang, J, C.; Sweitzer, N, K.; Cappola, T, P.; Cappola, A, R. Thyroid Dysfunction in Heart Failure and Cardiovascular Outcomes. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(12):e005266.

- Klein, I.; Danzi, S. Thyroid disease and the heart. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1725-35.

- Vale, C.; Neves, J, S.; von Hafe, M.; Borges-Canha, M.; Leite-Moreira, A. The Role of Thyroid Hormones in Heart Failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2019;33(2):179-188.

- Abdel-Moneim, A.; Gaber, A, M.; Gouda, S.; Osama, A.; Othman, S, I.; Allam, G. Relationship of thyroid dysfunction with cardiovascular diseases: updated review on heart failure progression. Hormones (Athens). 2020;19(3):301-309.

- Ahmadi, N.; Ahmadi, F.; Sadiqi, M.; Ziemnicka, K.; Minczykowski, A. Thyroid gland dysfunction and its effect on the cardiovascular system: a comprehensive review of the literature. Endokrynol Pol. 2020;71(5):466-478.

- Pandey, A.; Vaduganathan, M.; Arora, S.; Qamar, A.; Mentz, R. J.; Shah, S. J.; Chang, P. P.; Russell, S. D.; Rosamond, W, D.; Caughey, M. C. Temporal Trends in Prevalence and Prognostic Implications of Comorbidities Among Patients With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: The ARIC Study Community Surveillance. Circulation. 2020;142(3):230-243.

- Gerhardt, T.; Gerhardt, L. M. S.; Ouwerkerk, W.; Roth, G. A.; Dickstein, K.; Collins, S. P.; Cleland, J. G. F.; Dahlstrom, U.; Tay, W. T.; Ertl, G.; Hassanein, M.; Perrone, S. V.; Ghadanfar, M.; Schweizer, A.; Obergfell, A.; Filippatos, G.; Lam, C. S. P. Tromp J, Angermann CE. Multimorbidity in patients with acute heart failure across world regions and country income levels (REPORT-HF): a prospective, multicentre, global cohort study. The Lancet Global Health. 2023;11(12):e1874-1884.

- Lee, K. S.; Park, D. I.; Lee, J.; Oh, O.; Kim, N.; Nam, G. Relationship between comorbidity and health outcomes in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23(1):498.

- Murru, V.; Belfiori, E.; Sestu, A.; Casanova, A.; Serra, C.; Scuteri, A. Patterns of comorbidities differentially impact on in-hospital outcomes in heart failure patients. BMC Geriatr. 2025;25(1):371.

- Siddikatou, D.; Mandeng, M.; Linwa, E.; Ndobo, V.; Nkoke, C.; Mouliom, S.; Ndom, M.S.; Abas, A.; Kamdem, F. Heart failure outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review of recent studies conducted after the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline release. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2025;25(1):302.

- Joseph, S.M.; Novak, E.; Arnold, S.V.; Jones, P. G.; Khattak , H.; Platts, A, E.; Dávila-Román, V. G.; Mann, D.;L, Spertus, J.A. Comparable performance of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in patients with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(6):1139-46. [CrossRef]

- Böhm, M.; Swedberg, K.; Komajda ,M.; Borer, J. S.; Ford, I.; Dubost-Brama A.; Lerebours, G.; Tavazzi, L.; SHIFT Investigators. Heart rate as a risk factor in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): the association between heart rate and outcomes in a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9744):886-94. [CrossRef]

- 40. Tsujimoto T, Kajio, H. Efficacy of Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibitors for Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Mild to Moderate Chronic Kidney Disease. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2018; 25(12):1268-1277.

- Takeuchi, S.; Kohno, T.; Goda, A.; Shiraishi, Y.; Kitamura, M.; Nagatomo, Y.; Takei, M.; Nomoto, M.; Soejima, K.; Kohsaka, S.; Yoshikawa, T. West Tokyo Heart Failure Registry Investigators.. Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibitors for Patients with Mild or Moderate Chronic Kidney Disease and LVEF >40%. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024; 409:132190.

- Hein, A.M.; Scialla, J.J.; Edmonstron, D.; Cooper, L. B.; DeVore, A. D.; Mentz, R.J Medical Management of Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction and Concurrent Renal Dysfunction. JACC Heart Fail.2019; 7(5):371-382.

- Prokopidis, K.; Nortcliffe, A.; Okoye, C.; Venturelli, M.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Isanejad, M. Length of stay and prior heart failure admission in frailty and heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ESC Heart Fail. 2025;12:2417-2426.

- Shuvy, M.; Zwas, D.R.; Keren, A.; Gotsman, I. The age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index: A significant predictor of clinical outcome in patients with heart failure. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;73:103-104.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).