1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a major global health burden—third worldwide in incidence and second in cancer-related mortality—with approximately 1.9 million new cases and 900,000 deaths reported in 2020; these figures are projected to rise with population aging and the prevalence of modifiable risk factors [

1]. Despite advances with cytotoxic doublet/triplet chemotherapy, anti-VEGF and anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies, and refined surgical and interventional approaches, outcomes in metastatic CRC (mCRC) remain unsatisfactory; 5-year survival in stage IV disease is still low [

2,

3]. These observations underscore the need to identify molecular biomarkers that can guide management from the outset of care, moving beyond the simple dichotomy of microsatellite stability versus instability (MSS vs. MSI). The evidence summarized here supports a precision-medicine framework aimed at achieving deeper and more durable responses in molecularly selected patients, and at rigorously testing whether microsatellite-stable (MSS) tumors—traditionally considered poor candidates for immunotherapy—can nonetheless benefit, and through which underlying biological mechanisms. Consistent with this rationale, we prioritize mechanism-based therapeutic strategies and advocate for their earlier deployment in the first-line setting.

1.1. Rationale for Focusing on TP53

TP53 mutations occur in approximately half of colorectal cancers (CRCs) and are closely associated with chromosomal instability (CIN), resistance to genotoxic stress, and poorer prognosis [

4,

5]. In metastatic CRC (mCRC),

TP53 alterations frequently co-occur with lesions in the RAS pathway, compounding therapeutic resistance and shaping evolutionary trajectories under treatment pressure [

6]. Loss or mutation of p53 disrupts DNA-damage sensing, cell-cycle checkpoints, apoptosis, and tumor–microenvironment (TME) crosstalk, thereby influencing intrinsic tumor fitness and the likelihood of benefit from systemic therapies.

TP53 should no longer be relegated to a purely prognostic aside; it represents a logical starting point for composite, precision-oriented decision-making.

1.2. The Current Immunotherapy Baseline

Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) has transformed outcomes for the minority of patients with mismatch-repair–deficient/microsatellite-instability–high (dMMR/MSI-H) mCRC. In KEYNOTE-177, first-line pembrolizumab significantly prolonged progression-free survival versus chemotherapy and yielded durable overall survival [

7]. Nivolumab, alone or with low-dose ipilimumab, demonstrated consistent activity in previously treated MSI-H/dMMR disease (CheckMate 142) [

8]. However, these successes have not extended to the much larger population with mismatch-repair–proficient/microsatellite-stable (pMMR/MSS) tumors, where PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy has limited efficacy; accordingly, guidelines endorse ICB as standard of care only for MSI-H/dMMR disease and recommend clinical-trial enrollment in most other settings [

9,

10].

1.3. Centrality of Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB)

Tumor mutational burden (TMB) integrates the cumulative imprint of genomic damage and correlates with neoantigen load and responsiveness to ICB across tumor types [

11,

12,

13]. MSI-H tumors occupy the high end of the TMB spectrum, whereas most MSS CRCs—including many

TP53-mutated cases—fall within low-to-intermediate ranges. Notably, a subset of MSS/

TP53-mutated mCRC exhibits intermediate-to-high TMB that may suffice for immune recognition when combined with strategies that increase antigen visibility, reverse immune exclusion, and attenuate dominant immunosuppressive circuits. Framed in this way,

TP53 is not merely a passenger but a driver of mutational processes that shape TMB, immunoediting, and ultimately sensitivity to ICB. Historically, clinical oncology has emphasized

TP53’s prognostic and chemoresistance roles while paying comparatively less attention to its immunologic consequences—potentially obscuring opportunities precisely in patients whose TMB lies near an actionable threshold.

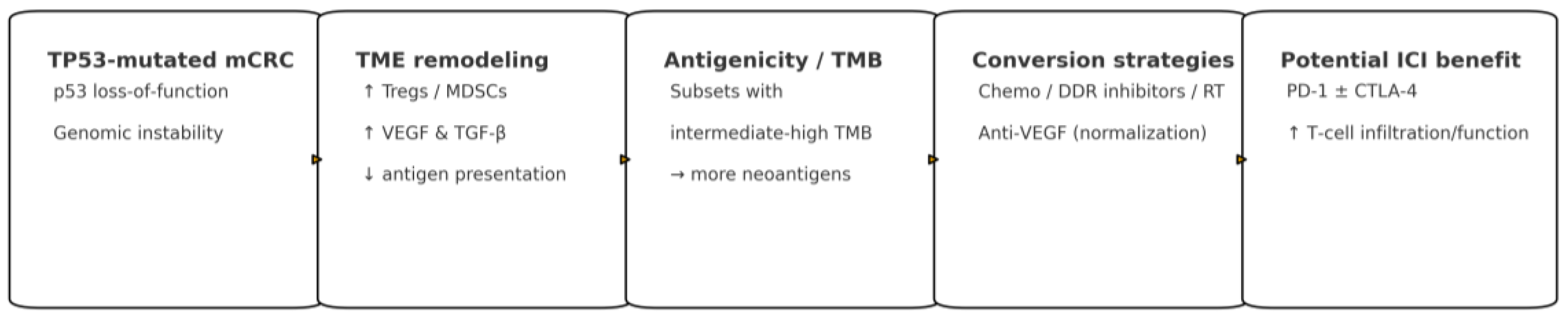

1.4. How TP53 Reshapes the TME

Loss of wild-type p53 can dampen antigen-presentation programs, favor PD-L1 upregulation, and recruit immunosuppressive myeloid and regulatory T-cell populations (MDSCs, TAMs, Tregs) within a hypoxic, VEGF- and TGF-β–enriched milieu [

14,

15,

16]. The result is an immune-excluded or inflamed-yet-suppressed phenotype that is poorly permissive to PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy. Conversely,

TP53 loss may heighten replicative stress and cGAS–STING activation in certain contexts, potentially enhancing immunogenicity when paired with appropriate priming and vascular-normalizing partners—an effect most evident when panel-calibrated TMB is higher.

TP53 mutation is not monolithic: conformational versus DNA-contact alterations, truncations, and compound events can exert distinct effects on cellular stress responses and immune signaling [4–68]. Clinically, these nuances matter because they modulate both the

quantity of mutations (and thus putative neoantigens) and the

quality of antigen presentation, helping explain why intermediate TMB may be sufficient for durable immune control in some MSS/

TP53-mutated tumors but not others.

1.5. Signals from Combination Studies

In unselected pMMR/MSS mCRC, adding atezolizumab to FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab (AtezoTRIBE) improved progression-free survival, suggesting that chemotherapy and anti-angiogenic “priming” can unlock ICB benefit in permissive biology [

17]. By contrast, nivolumab plus mFOLFOX6/bevacizumab (CheckMate 9X8) and lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab (LEAP-017) did not meet their primary endpoints [

18,

19]. Complementary evidence from the randomized ROME trial shows that genomically matched, next-generation sequencing (NGS)–guided strategies can improve outcomes and, in select cases, nominate ICB for TMB-high MSS disease [

20].

1.6. Where We Are Going and Why It Matters for Patients

The field is moving from binary eligibility (MSI-H vs. MSS) toward composite, biology-anchored selection that integrates

TP53 status, calibrated TMB, and remediable TME features. For practicing oncologists, the implications are concrete: (i) prioritize early-line regimens that combine PD-1/PD-L1 agents with cytotoxic and anti-VEGF partners in biologically enriched settings; (ii) use dynamic pharmacodynamic readouts (e.g., early ctDNA kinetics, induction of interferon-stimulated gene signatures) to adapt therapy; and (iii) channel patients toward biomarker-anchored trials when single-agent ICB is unlikely to succeed [

7,

8,

9,

10,

13,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Re-centering TMB and the immunologic consequences of

TP53 in mCRC is not academic; it determines who can access effective immunotherapy now and where combination strategies can realistically extend benefit next.

1.7. Organotropism and ctDNA

Liver metastases in mCRC impose systemic immunologic tolerance through antigen-presenting cell sequestration and cytokine gradients that can blunt T-cell priming—a phenomenon increasingly recognized in prospective analyses of ICI-containing regimens. This organotropism intersects with

TP53 and TMB: patients without dominant hepatic disease, or with well-controlled liver burden, appear more likely to benefit from chemo–anti-VEGF–PD-1/PD-L1 strategies when their mutational background is permissive. Finally, dynamic biomarkers—especially early ctDNA decline and induction of interferon-stimulated gene programs—offer real-time confirmation that immune recognition is occurring, enabling escalation or de-escalation before radiographic changes [

7,

8,

9,

10,

13,

17,

18,

19,

20]. These practical considerations underpin the precision-oncology approach advanced in this manuscript and justify a focused appraisal of specific evidence in mCRC.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Quality Framework

This narrative, non-systematic review, was conducted in accordance with the SANRA criteria, with attention to justification of the topic, a focused aim, comprehensive literature coverage, transparent presentation, and appropriate interpretation [

21].

2.2. Data Sources and Scope

We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science for literature published from 2010 through September 30, 2025. To ensure clinical relevance and alignment with contemporary practice, we also reviewed the 2023 ESMO and 2025 NCCN guidelines and hand-searched reference lists of pertinent articles [

9,

10]. The review prioritizes studies in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) but includes earlier-stage data when mechanistically informative (e.g., TP53 biology, TMB, TME features) and clearly applicable to immunotherapy strategies.

2.3. Search Strategy and Selection

The strategy used concept blocks combined with Boolean operators and database-specific subject headings/keywords for: colorectal cancer; TP53 or p53; microsatellite status (MSI/dMMR and MSS) and TMB; immunotherapy (including PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors); and tumor-microenvironment (TME) mechanisms relevant to TP53 (e.g., antigen processing/presentation, cytokine signaling, VEGF, TGF-β).

Two reviewers, MS and FM, independently screened titles/abstracts, followed by full-text assessment against predefined criteria. Eligible studies were clinical trials (phase I–III), real-world cohorts, systematic reviews/meta-analyses, and translational or preclinical investigations that directly examined TP53 status or function, MSI/TMB, TME correlates, or immune-checkpoint inhibition (ICI) in the context of colorectal cancer. We excluded non-English case reports, narrative commentaries without primary data, editorials, and studies with insufficient genomic or immunologic annotation to support the review aims. Preprints were considered only if a peer-reviewed version became available within the search window. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

From each included report we abstracted study design, population and disease setting (with an emphasis on mCRC), TP53 assessment method and genotype (e.g., missense vs truncating, hotspot status), MSI/dMMR vs MSS classification, TMB measurement approach, TME readouts (e.g., antigen-presentation markers, PD-L1, myeloid/TGF-β signatures), intervention details (ICI alone or in combination), and key outcomes (objective response, PFS/OS, and—when available—ctDNA dynamics and translational endpoints).

2.5. Bias and Limitations

Risk of biased interpretation was mitigated through duplicate screening, structured data abstraction, and cross-checking of findings across study types. As a narrative review, this work was not prospectively registered and effect estimates should be interpreted cautiously where confounding and selection biases are likely.

3. Results

MSI-H as a benchmark for checkpoint blockade in mCRC. Microsatellite instability–high (MSI-H) disease provides a paradigm of immunotherapy success and anchors our framework for where—and why—checkpoint blockade can be effective in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). In the phase III KEYNOTE-177 trial, pembrolizumab improved progression-free survival (PFS) versus chemotherapy (median 16.5 vs. 8.2 months; HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.45–0.79) and, with more than 5 years of follow-up, yielded a median overall survival (OS) of 77.5 vs. 36.7 months (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.53–0.99), with 5-year OS rates of 54.8% vs. 44.2% despite extensive cross-over [

7]. The durability and separation of survival curves reinforce MSI-H/dMMR mCRC as a distinctly immunotherapy-sensitive phenotype [

22].

Durability with dual checkpoint blockade. Durable activity has also been observed with nivolumab alone or with low-dose ipilimumab: in CheckMate 142, the ~4-year update reported an objective response rate of 65% (95% CI 55–73), complete responses of 13%, and median PFS and OS not reached [

8]. Taken together, these data establish the biologic and clinical rationale for immunotherapy in MSI-H/dMMR mCRC and define a benchmark for comparison in microsatellite-stable disease [

23].

TP53 as a contextual modifier in the broader CRC population. Against this benchmark, TP53 emerges as a key modifier of outcome in the broader CRC population. Mutations—present in approximately half of cases—show heterogeneous prognostic associations and, in specific contexts (including gain-of-function variants and co-mutation with KRAS), correlate with worse outcomes and reduced chemotherapy benefit [

4,

5,

6]. In routine practice, patients with MSS/TP53-mutated tumors rarely receive immune checkpoint inhibitors outside clinical trials. Large genomic datasets place TP53 alterations predominantly within MSS disease, co-occurring with chromosomal instability and WNT/MAPK pathway events; these molecular constellations align with transcriptomic taxonomies that capture epithelial/proliferative and mesenchymal-like states with distinct immune ecologies [

24,

25].

TMB and the MSS/TP53 interplay. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) further modulates immunogenicity and response to PD-1/PD-L1 therapy across cancers [

11,

12,

13]. While MSI-H usually entails high TMB, a fraction of MSS/TP53-mutated CRCs display intermediate-to-high TMB, suggesting potential for benefit when contextual biomarkers are favorable. Pan-tumor analyses consistently associate higher TMB with improved benefit from checkpoint blockade, while underscoring that tissue context and neoantigen clonality shape the predictive value of TMB (11, 26) In this direction, the randomized phase II ROME trial showed that genomically matched therapy outperformed standard care (PFS 3.5 vs. 2.8 months; HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.53–0.82; P = 0.0002) and improved objective responses (17.5% vs. 10%), supporting NGS-guided strategies that include immunotherapy for TMB-high tumors when appropriate [

20].

Mechanistic basis for immune evasion in TP53-mutated CRC. Mechanistically, TP53 dysfunction reduces antigen visibility and promotes immune escape: wild-type p53 sustains antigen processing/presentation (e.g., TAP1/ERAP1) and represses PD-L1 via the p53–miR-34 axis, so TP53 loss can diminish MHC-I peptide loading and increase PD-L1 expression, weakening cytotoxic T-cell recognition [

14,

15,

16]. These pressures are compounded by TP53-associated chromosomal instability, which generates micronuclei capable of activating cGAS–STING and innate sensing; in CRC, however, such signals are frequently buffered by a TGF-β–rich, myeloid-skewed, immune-excluded microenvironment that limits effector trafficking [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

Therapeutic implications: converting “cold” to “hot”. Together, these results motivate combination strategies in MSS/TP53-mutated CRC aimed at converting “cold” tumors into “hot” ones—boosting antigenicity with DNA-damage–inducing chemotherapy or radiotherapy, restoring trafficking and function via vascular and stromal remodeling with anti-VEGF or TGF-β-pathway modulation, and addressing non-redundant inhibitory axes with dual-checkpoint approaches [

32].

Conceptual synthesis. This framework explains why MSI-H tumors respond to PD-1 blockade and clarifies how, in selected MSS/TP53-mutated subgroups—particularly where TMB is intermediate-to-high and the microenvironment can be favorably reprogrammed—immunotherapy-containing regimens may deliver clinically meaningful benefit.

Figure 1 provides a schematic summary of these concepts.

4. Discussion

This narrative review evaluates the potential of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) strategies in

TP53-mutated colorectal cancer (CRC) and investigates the interplay among

TP53, tumor mutational burden (TMB), and the tumor microenvironment (TME). Randomized studies consistently show that patients with microsatellite instability–high or mismatch-repair–deficient (MSI-H/dMMR) disease derive substantial and durable benefit from programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)–based therapy, whereas outcomes in mismatch-repair–proficient or microsatellite-stable (pMMR/MSS) disease remain modest and variable [

7,

8,

17,

18,

19].

TP53 alterations are among the most common genomic events in CRC and frequently co-occur with canonical chromosomal instability (CIN) and MSS biology. Although

TP53 loss can promote genomic instability, it does not consistently generate a high neoantigen burden. Most

TP53-mutated CRCs are MSS with intermediate-to-low TMB and display an immune-excluded or myeloid-inflamed TME, resulting in limited responses to single-agent ICB and suboptimal outcomes with standard therapies.

Current combination strategies in pMMR/MSS CRC aim to transform a noninflamed TME into an antigen-presenting, inflamed milieu. For example, the phase II AtezoTRIBE trial demonstrated improved progression-free survival (PFS) with atezolizumab plus FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab. By contrast, adding nivolumab to mFOLFOX6/bevacizumab in CheckMate 9X8 and lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in LEAP-017 did not meet primary endpoints [

17,

18,

19]. These findings suggest that benefit is confined to specific biological subsets, such as those with pre-existing interferon signaling, higher (yet MSS-range) TMB, immunogenic subclones, or a TME responsive to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or multikinase inhibition.

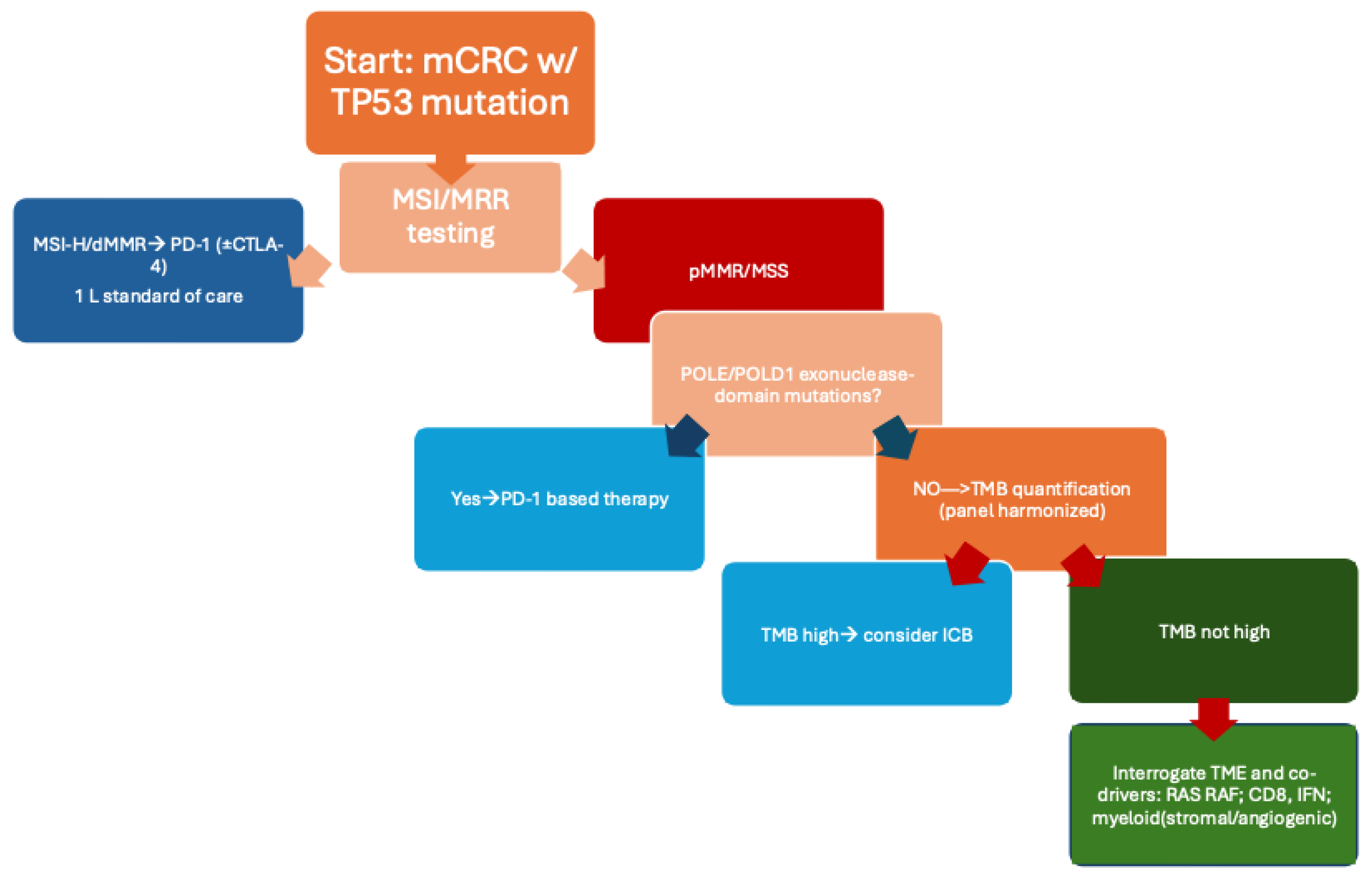

A precision-oncology strategy for

TP53-mutated CRC should integrate genomic and microenvironmental features rather than rely on single biomarkers. Assessment of MSI/MMR status and panel-calibrated TMB can identify tumors with intrinsic antigenicity. Detection of *POLE/

POLD1 exonuclease-domain mutations may indicate ultramutated, ICI-sensitive MSS disease. For the prevalent MSS/

TP53-mutated group, evaluating transcriptomic and spatial features—such as interferon signaling, CD8 infiltration, and myeloid–stromal programs—can inform selection for appropriate ICB combinations, potentially with chemotherapy, anti-VEGF, or multikinase partners [

7,

8,

17,

18,

19]. Therapeutic strategies should be adaptive, with pharmacodynamic markers—such as reductions in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or induction of interferon-stimulated gene signatures—guiding escalation, maintenance, or de-escalation of ICB-containing regimens. This dynamic, biology-driven approach may improve disease control in previously poor-risk MSS/

TP53-mutated subsets.

Figure 2 presents a clinical algorithm for selecting optimal therapeutic strategies in

TP53-mutated CRC.

Framed within precision medicine, these observations argue for composite, context-aware biomarkers that integrate

TP53alteration class (missense vs. truncating; hotspot; clonality), MSI/MMR status, panel-harmonized TMB, and spatial TME metrics to guide therapy from the earliest lines of care. Mechanistically, wild-type p53 sustains antigen processing/presentation and represses PD-L1 via the p53–miR-34 axis; conversely,

TP53 loss can diminish MHC-I peptide loading and increase PD-L1, reducing cytotoxic T-cell recognition [

27,

28,

29]. In parallel,

TP53-associated CIN generates micronuclei that engage cGAS–STING and innate sensing, but these signals are frequently buffered by a TGF-β–rich, myeloid-skewed, immune-excluded microenvironment—clarifying why single-agent ICB underperforms in many MSS/

TP53 tumors and why stromal/vascular modulation may be required [

30,

31].

In contemporary practice, this framework can be operationalized through baseline genotyping and longitudinal monitoring using tissue and liquid biopsy. Regulatory-cleared liquid assays such as Guardant360 CDx and FoundationOne Liquid CDx provide comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) from plasma, enabling detection of targetable alterations, MSI status, and resistance mechanisms when tissue is unavailable or serial sampling is required [

33,

34]. Both platforms have undergone analytical and clinical validation, including U.S. regulatory premarket approval (PMA) for specific indications, supporting their use as adjuncts to tissue testing in advanced solid tumors. Beyond static profiling, ctDNA dynamics offer actionable pharmacodynamic readouts—early ctDNA clearance correlates with benefit and can inform escalation or de-escalation decisions, with growing evidence across CRC settings [

35,

36]. From a health-economics perspective, the value of liquid biopsy hinges on test price, turnaround time, and the extent to which biomarker-guided treatment reduces ineffective therapy and downstream costs; modeling suggests ctDNA-guided strategies can be cost-effective under realistic price thresholds and when they meaningfully alter chemotherapy utilization [

37,

38].

For MSS/

TP53-mutated CRC specifically, we propose an iterative, biology-driven approach: (i) confirm MSS/MMR status and quantify TMB using calibrated panels; (ii) profile

TP53 genotype class and clonality together with co-drivers (e.g.,

KRAS,

BRAF, WNT/MAPK components); (iii) assess TME state via transcriptomic/spatial surrogates (interferon signaling, CD8 density, myeloid/TGF-β signatures); and (iv) integrate on-treatment ctDNA kinetics to refine the likelihood of durable benefit. Patients meeting composite thresholds—such as MSS with intermediate-to-high TMB, favorable interferon/T-cell infiltration, and modifiable stromal programs—may be prioritized for ICB-containing combinations with anti-VEGF or selected multikinase partners, whereas those lacking these features could be directed to alternative investigational strategies or cytotoxic backbones with biomarker-guided intensification. Prospective studies should therefore embed

TP53-anchored composite biomarkers and prespecified translational endpoints, incorporate early radiographic plus ctDNA-based interim assessments, and stratify by MSI/TMB/TME context to de-risk negative trials and accelerate learning. Within this precision-oncology framework, the clinical algorithm in

Figure 2 synthesizes how to triage

TP53-mutated CRC into rational treatment paths, emphasizing readiness for early-line deployment when host and tumor immunity are most malleable.

5. Conclusions

This review reframes immunotherapy in colorectal cancer (CRC) from a binary paradigm to an integrated, biology-driven model in which TP53 functions as a contextual modifier alongside tumor mutational burden (TMB) and the tumor microenvironment (TME). In most CRCs, TP53 alteration aligns with CIN/MSS biology, lower antigenicity, and immune exclusion—features that help explain the modest activity of single-agent PD-1. Yet, within defined contexts—including co-occurring *POLE/POLD1 exonuclease-domain mutations, higher panel-calibrated TMB, and interferon-rich or angiogenesis-normalizable microenvironments—TP53 contributes to identifying patients capable of mounting effective antitumor immunity. Building on these insights, our synthesis supports a shift from single-marker gatekeeping to composite, context-aware decision tools that integrate TP53 genotype class and clonality with MSI/MMR status, harmonized TMB thresholds, and spatially informed TME metrics.

The central clinical message is one of precision inclusion. Rather than excluding MSS/TP53-mutated disease from immunotherapy a priori, oncologists can triage patients based on integrated biology. When intrinsic antigenicity is present—because of ultramutation, clearly elevated TMB on assay-calibrated panels, or strong interferon signaling—PD-1 monotherapy remains a defensible choice. When trafficking barriers or stromal programs dominate—reflected by immune exclusion, myeloid skew, or angiogenic dependence—rational combinations (e.g., PD-1 with anti-VEGF or selected multikinase partners) become the preferred strategy. When antigen generation is limiting, cytotoxic or radiation priming can be sequenced to increase antigen release and presentation before or alongside checkpoint blockade. In each scenario, the role of TP53 is not to serve as a solitary predictor but to anchor the composite, connecting genotype with immune context and therapeutic design.

Equally important is a shift from static to dynamic decision-making. Baseline biology should be complemented by early on-treatment readouts—most notably circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) clearance and induction of immune-activation signatures—that provide real-time evidence of benefit. A practical algorithm emerges: if early ctDNA declines substantially or immune-activation signatures rise, treatment can be maintained or de-escalated to minimize toxicity and preserve quality of life; if molecular response is absent despite adequate exposure, timely escalation or regimen modification can be pursued. This adaptive approach is particularly relevant in the first-line setting, when host and tumor immunity are most amenable to reprogramming and the long-term cost of suboptimal choices is greatest.

Operationalization in routine care is feasible. The initial evaluation should pair tissue-based testing with liquid biopsy when tissue is scarce, archival, or when longitudinal sampling is required. In practice, this means confirming MSI/MMR status; measuring TMB on a validated, panel-harmonized scale; and characterizing TP53 with sufficient granularity to distinguish missense from truncating events, identify hotspot residues, and comment on clonality where possible. Parallel assessment of TME state—via standardized transcriptomic surrogates and, where available, spatial profiling—helps define whether the dominant bottleneck is antigenicity, trafficking, or immune suppression. Embedding these data into tumor-board workflows enables consistent, reproducible decisions traceable to biology rather than to treatment habit.

The novelty of this framework lies in rendering TP53 clinically actionable without reifying it as a single-gene switch. By placing TP53 at the center of a composite biomarker, we bridge well-described mechanistic links—p53-dependent antigen presentation, PD-L1 regulation, genomic instability and innate sensing, and stromal/angiogenic programs—with concrete therapeutic choices. This connection clarifies why MSI-H tumors respond and provides a biologically coherent path to benefit for selected MSS/TP53-mutated patients who would otherwise be categorized as non-responders. The approach is scalable: as new readouts become available (e.g., refined spatial metrics or improved measures of neoantigen clonality), they can be integrated into the composite without forcing wholesale changes in clinical workflow.

Standardization is an immediate next step. For TP53, we advocate reporting that specifies variant class (missense vs. truncating) and hotspot status and, where feasible, incorporates clonality to estimate the fraction of tumor cells affected. For TMB, cross-panel calibration and CRC-appropriate thresholds are required to reduce misclassification at the margins; values should be interpreted alongside expected neoantigen quality and clonality rather than as a raw count alone. For the TME, we encourage a shift toward reproducible, clinically portable measures—interferon signaling, CD8 density, and myeloid/TGF-β programs—that can be prospectively applied in trials and, ultimately, embedded in decision support for routine practice. The same principles apply to ctDNA: assays should be standardized for minimal residual disease and for pharmacodynamic response, with clear definitions of meaningful decline and guidance on how those changes should alter management.

Prospective validation is the logical proving ground. Trials should stratify by TP53-anchored composite criteria; include early radiographic and molecular checkpoints; and predefine rules for escalation, maintenance, or de-escalation linked to on-treatment biology. Early-line studies are likely to yield the greatest benefit, both because immune competence is higher and because successful reprogramming can compound across subsequent lines. Complementary real-world evidence—through registry-based trials and structured learning-health-system datasets—can accelerate external validation and identify subgroups that may be under-represented in traditional studies. Together, these efforts will clarify which combinations deliver durable control with acceptable toxicity and in which biologic niches they should be deployed.

Implementation will also hinge on practicality and equity. Turnaround time, cost, and access determine whether composite biomarker strategies can be delivered outside major centers. Where resources are constrained, a tiered approach can prioritize tests with the greatest immediate impact on decision-making (e.g., MSI/MMR and TMB on a validated panel), adding layers—such as transcriptomic TME surrogates or spatial analysis—when they are likely to change management. Clear reporting templates and shared decision-making with patients can further align therapeutic choices with values and expectations, especially when trade-offs between efficacy, toxicity, and logistics are salient.

Taken together, the evidence supports a transition from exclusion to informed inclusion for MSS/TP53-mutated CRC. By aligning mechanisms with therapy—and by measuring early whether the chosen mechanism is working—clinicians can convert a historically poor-risk category into stratified, treatable subgroups. The goal is not merely incremental benefit but deeper, more durable responses for a larger proportion of patients, achieved with greater predictability and fewer cycles of ineffective treatment. If adopted, this precision framework can change how immunotherapy is used in metastatic CRC and, more broadly, how complex molecular signals are translated into routine, patient-centered care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, MS and FM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical consideration

not applicable.

Consent to participate

not applicable.

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability

Data are cited in the text.

Abbreviations

| CRC |

colorectal cancer. |

| MSI-H |

microsatellite instability-high. |

| dMMR |

deficient mismatch repair. |

| pMMR |

proficient mismatch repair. |

| MSS |

microsatellite stable. |

| ICB |

immune checkpoint blockade. |

| PD-1 |

programmed cell death protein 1. |

| CTLA-4 |

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4. |

| TMB |

tumor mutational burden. |

| TME |

tumor microenvironment. |

| VEGF |

vascular endothelial growth factor. |

| POLE |

DNA polymerase epsilon. |

| POLD1 |

DNA polymerase delta 1. |

| ctDNA |

circulating tumor DNA. |

| CIN |

chromosomal instability. |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71(3), 209-249. [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Colorectal Cancer. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. Accessed October 11, 2025.

- Cremolini, C.; Antoniotti, C.; Stein, A.; Bendell, J.; Gruenberger, T.; Rossini, D.; Masi, G.; Ongaro, E.; Hurwitz, H.; Falcone, A.; et al. Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of FOLFOXIRI Plus Bevacizumab Versus Doublets Plus Bevacizumab as Initial Therapy of Unresectable Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3314–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, M.; Hollstein, M.; Hainaut, P. TP53 Mutations in Human Cancers: Origins, Consequences, and Clinical Use. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 2, a001008–a001008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P.A.; Vousden, K.H. Mutant p53 in Cancer: New Functions and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Fan, Y. Combined KRAS and TP53 mutation in patients with colorectal cancer enhance chemoresistance to promote postoperative recurrence and metastasis. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, T.; Shiu, K.-K.; Kim, T.; Jensen, B.; Jensen, L.; Punt, C.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Alcaide-Garcia, J.; Gibbs, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer: 5-year follow-up from the randomized phase III KEYNOTE-177 study. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 36, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, T.; Lonardi, S.; Wong, K.; Lenz, H.-J.; Gelsomino, F.; Aglietta, M.; Morse, M.; Van Cutsem, E.; McDermott, R.; Hill, A.; et al. Nivolumab plus low-dose ipilimumab in previously treated patients with microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer: 4-year follow-up from CheckMate 142. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Roselló, S.; Arnold, D.; Normanno, N.; Taïeb, J.; Seligmann, J.; De Baere, T.; Osterlund, P.; Yoshino, T.; et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 34, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer. Version 2.2025. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1. Accessed October 11, 2025. Rectal Cancer. Version 3.2025. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1. Accessed October 11, 2025.

- Samstein, R.M.; Lee, C.-H.; Shoushtari, A.N.; Hellmann, M.D.; Shen, R.; Janjigian, Y.Y.; Barron, D.A.; Zehir, A.; Jordan, E.J.; Omuro, A.; et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, Z.R.; Connelly, C.F.; Fabrizio, D.; Gay, L.; Ali, S.M.; Ennis, R.; Schrock, A.; Campbell, B.; Shlien, A.; Chmielecki, J.; et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickler JH, Hanks BA, Khasraw M. Tumor mutational burden as a predictor of immunotherapy response: pitfalls and promises. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(5):1236–1241.

- Blagih, J.; Buck, M.D.; Vousden, K.H. p53, cancer and the immune response. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenhuber, E.R.; Lowe, S.W. Putting p53 in Context. Cell 2017, 170, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniotti, C.; Rossini, D.; Pietrantonio, F.; Catteau, A.; Salvatore, L.; Lonardi, S.; Boquet, I.; Tamberi, S.; Marmorino, F.; Moretto, R.; et al. Upfront FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab with or without atezolizumab in the treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (AtezoTRIBE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, H.-J.; Parikh, A.; Spigel, D.R.; Cohn, A.L.; Yoshino, T.; Kochenderfer, M.; Elez, E.; Shao, S.H.; Deming, D.; Holdridge, R.; et al. Modified FOLFOX6 plus bevacizumab with and without nivolumab for first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: phase 2 results from the CheckMate 9X8 randomized clinical trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e008409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawazoe, A.; Xu, R.-H.; Passhak, M.; Teng, H.-W.; Shergill, A.; Gumus, M.; Qvortrup, C.; Stintzing, S.; Towns, K.; Kim, T.W.; et al. Lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab Versus Standard of Care for Previously Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Final Analysis of the Randomized, Open-Label, Phase III LEAP-017 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2918–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, P.; Curigliano, G.; Biffoni, M.; Lonardi, S.; Scagnoli, S.; Fornaro, L.; Guarneri, V.; De Giorgi, U.; Ascierto, P.A.; Blandino, G.; et al. Genomically matched therapy in advanced solid tumors: the randomized phase 2 ROME trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 3514–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, T.; Shiu, K.-K.; Kim, T.W.; Jensen, B.V.; Jensen, L.H.; Punt, C.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Benavides, M.; Gibbs, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab in Microsatellite-Instability–High Advanced Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2207–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, M.J.; Lonardi, S.; Wong, K.Y.M.; Lenz, H.-J.; Gelsomino, F.; Aglietta, M.; Morse, M.A.; Van Cutsem, E.; McDermott, R.; Hill, A.; et al. Durable Clinical Benefit With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in DNA Mismatch Repair–Deficient/Microsatellite Instability–High Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012, 487, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinney, J.; Dienstmann, R.; Wang, X.; de Reyniès, A.; Schlicker, A.; Soneson, C.; Marisa, L.; Roepman, P.; Nyamundanda, G.; Angelino, P.; et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristescu, R.; Mogg, R.; Ayers, M.; Albright, A.; Murphy, E.; Yearley, J.; Sher, X.; Liu, X.Q.; Lu, H.; Nebozhyn, M.; et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade–based immunotherapy. Science 2018, 362, eaar3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, K.; Chen, X. Differential regulation of cellular target genes by p53 devoid of the PXXP motifs with impaired apoptotic activity. Oncogene 1999, 18, 2149–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Niu, D.; Lai, L.; Ren, E.C. p53 increases MHC class I expression by upregulating the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase ERAP1. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, M.A.; Ivan, C.; Valdecanas, D.; Wang, X.; Peltier, H.J.; Ye, Y.; Araujo, L.; Carbone, D.P.; Shilo, K.; Giri, D.K.; et al. PDL1 Regulation by p53 via miR-34. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, K.J.; Carroll, P.; Martin, C.-A.; Murina, O.; Fluteau, A.; Simpson, D.J.; Olova, N.; Sutcliffe, H.; Rainger, J.K.; Leitch, A.; et al. cGAS surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. Nature 2017, 548, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauriello, D.V.F.; Palomo-Ponce, S.; Stork, D.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Badia-Ramentol, J.; Iglesias, M.; Sevillano, M.; Ibiza, S.; Cañellas, A.; Hernando-Momblona, X.; et al. TGFβ drives immune evasion in genetically reconstituted colon cancer metastasis. Nature 2018, 554, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, P.S.; Chen, D.S. Top 10 Challenges in Cancer Immunotherapy. Immunity 2020, 52, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanman, R.B.; A Mortimer, S.; A Zill, O.; Sebisanovic, D.; Lopez, R.; Blau, S.; A Collisson, E.; Divers, S.G.; Hoon, D.S.B.; Kopetz, E.S.; et al. Analytical and Clinical Validation of a Digital Sequencing Panel for Quantitative, Highly Accurate Evaluation of Cell-Free Circulating Tumor DNA. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0140712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, R.; Li, M.; Hughes, J.; Delfosse, D.; Skoletsky, J.; Ma, P.; Meng, W.; Dewal, N.; Milbury, C.; Clark, T.; et al. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne Liquid CDx, a novel 324-Gene cfDNA-based comprehensive genomic profiling assay for cancers of solid tumor origin. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0237802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Lahouel, K.; Lo, S.N.; Wang, Y.; Kosmider, S.; Wong, R.; Shapiro, J.; Lee, M.; Harris, S.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis Guiding Adjuvant Therapy in Stage II Colon Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2261–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Wang, Y.; Lo, S.N.; Lahouel, K.; Cohen, J.D.; Wong, R.; Shapiro, J.D.; Harris, S.J.; Khattak, A.; Burge, M.E.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis guiding adjuvant therapy in stage II colon cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomized DYNAMIC trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Greuter, M.J.E.; Schraa, S.J.; Vink, G.R.; Phallen, J.; Velculescu, V.E.; Meijer, G.A.; Broek, D.v.D.; Koopman, M.; Roodhart, J.M.L.; et al. Early evaluation of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ctDNA-guided selection for adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II colon cancer. Ther. Adv. Med Oncol. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, Z.; Wagner, S.; Agyekum, A.; Pumpalova, Y.S.; Prest, M.; Lim, F.; Rustgi, S.; Kastrinos, F.; Grady, W.M.; Hur, C. Cost-Effectiveness of Liquid Biopsy for Colorectal Cancer Screening in Patients Who Are Unscreened. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2343392–e2343392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).