Submitted:

08 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample Description

2.2. Experimental and Control Design

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Model Equations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results and Discussion

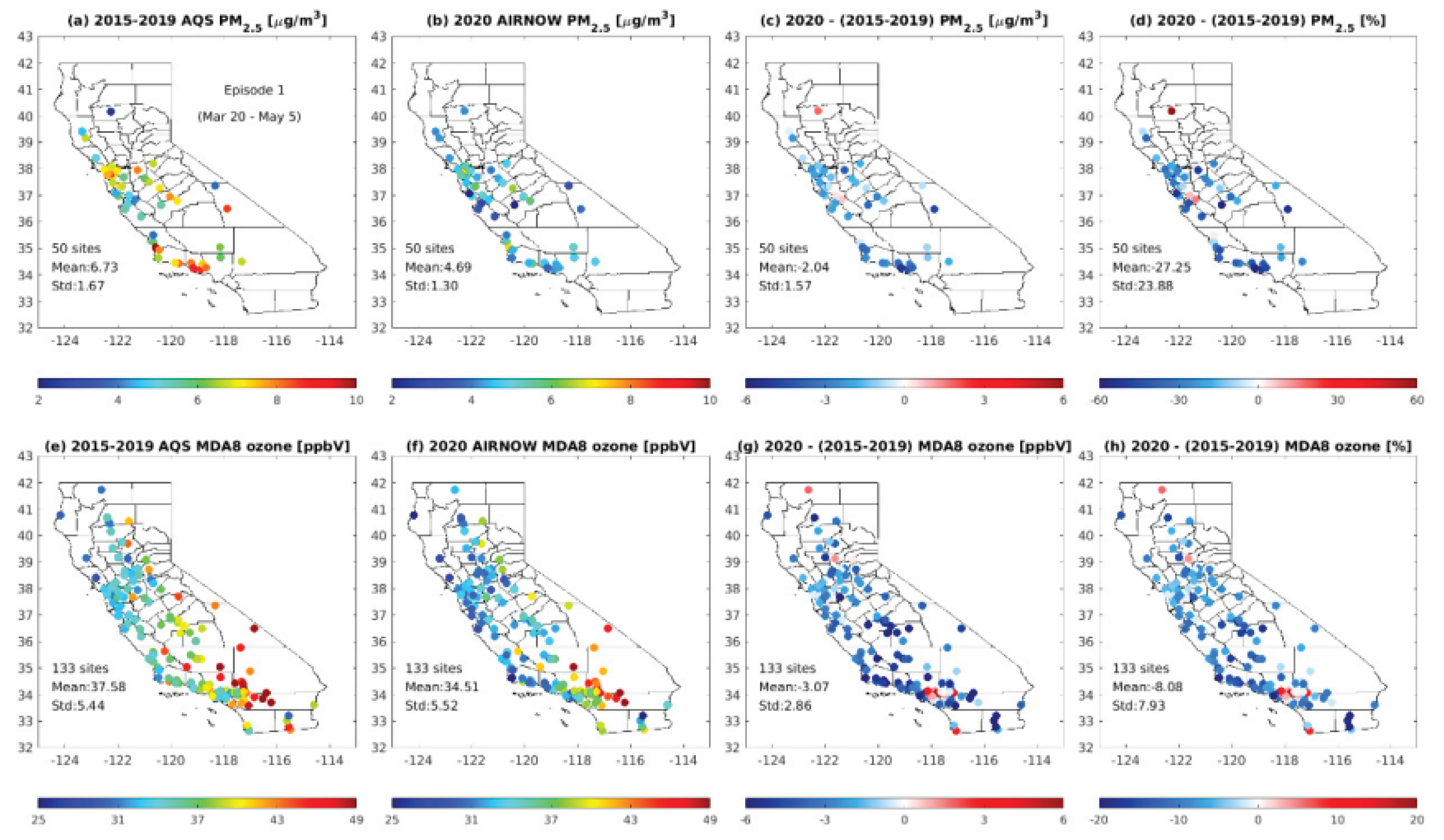

3.1. Lockdown Changes in Aerosols and Related Pollutants

3.2. Regional Precipitation Signals During the Lockdown Window

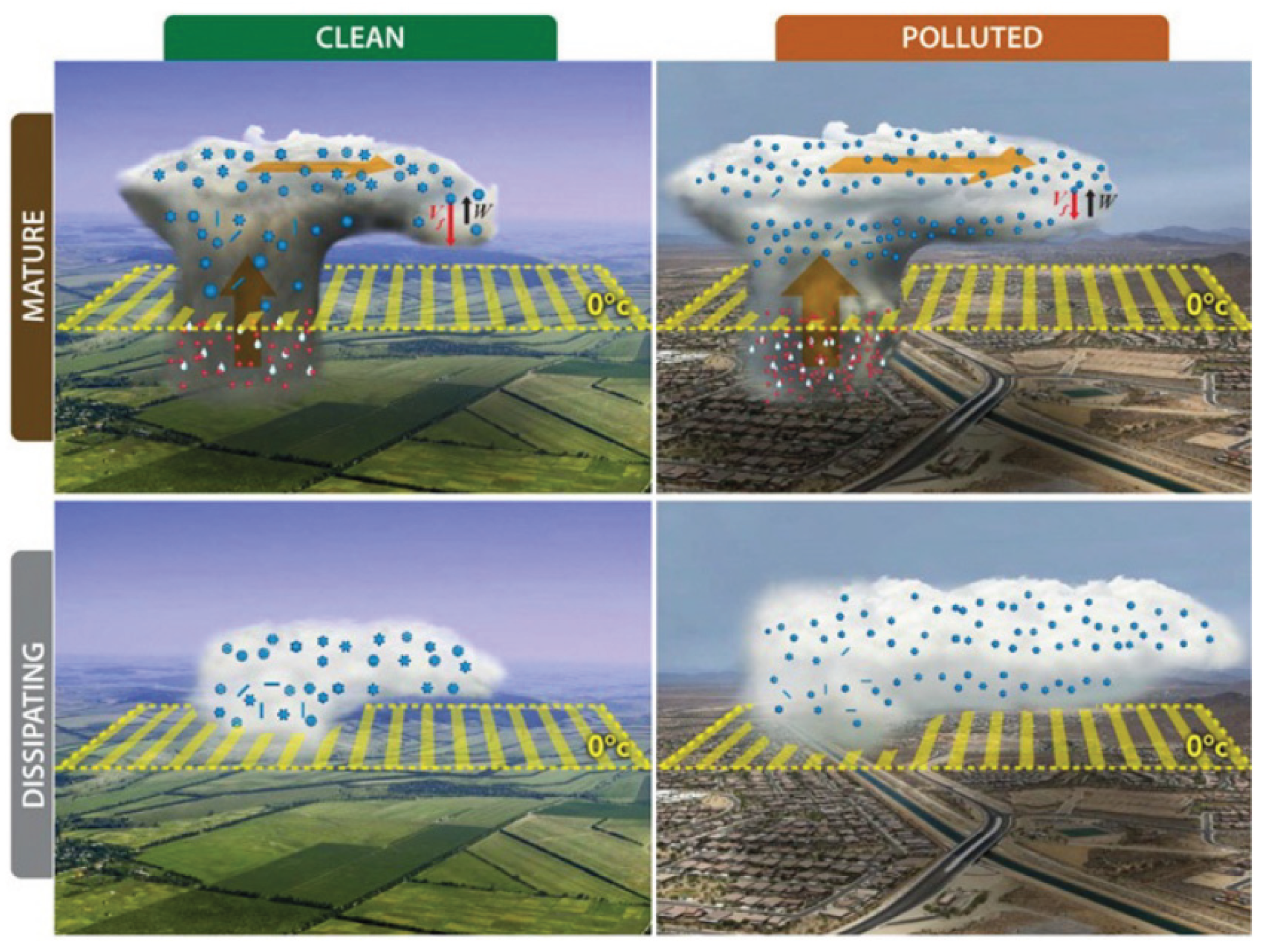

3.3. Site-Scale Links Between AOD and Precipitation

3.4. Context, Limits and Implications

Conclusions

References

- Chandrakar, K. K., Morrison, H., Grabowski, W. W., & Lawson, R. P. (2024). Are turbulence effects on droplet collision–coalescence a key to understanding observed rain formation in clouds?. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(27), e2319664121.

- Joy, K. S., Zaman, S. U., Pavel, M. R. S., Islam, M. S., & Salam, A. (2024). Spatio-temporal variation of aerosol optical depth and black carbon mass concentration over five airports across Bangladesh: emphasis on effect of COVID-19 lockdown. Asian Journal of Atmospheric Environment, 18(1), 15.

- Wójcik-Gront, E., & Gozdowski, D. (2025). Air Pollution Monitoring and Modeling: A Comparative Study of PM, NO2, and SO2 with Meteorological Correlations. Atmosphere, 16(10), 1199.

- Stier, P., van den Heever, S. C., Christensen, M. W., Gryspeerdt, E., Dagan, G., Saleeby, S. M., ... & Tao, W. K. (2024). Multifaceted aerosol effects on precipitation. Nature Geoscience, 17(8), 719-732.

- Wang, S., Murakami, H., & Cooke, W. (2024). Anthropogenic effects on tropical cyclones near Western Europe. npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 7(1), 173.

- Yang, Z., Hu, W., Sengupta, A., Monache, L. D., DeFlorio, M. J., Ghazvinian, M., ... & Kalansky, J. (2025). Improving Weeks 1-2 Temperature Forecasts in the Sierra Nevada Region Using Analog Ensemble Post-Processing with Implications for Better Prediction of Snowmelt, Water Storage, and Streamflow. Journal of Hydrometeorology.

- Scholl, M. A., McCabe, G. J., Olson, C. G., & Powlen, K. A. (2025). Climate change and future water availability in the United States (No. 1894-E). US Geological Survey.

- Stier, P., van den Heever, S. C., Christensen, M. W., Gryspeerdt, E., Dagan, G., Saleeby, S. M., ... & Tao, W. K. (2024). Multifaceted aerosol effects on precipitation. Nature Geoscience, 17(8), 719-732.

- Wang, C., & Chakrapani, V. (2023). Environmental Factors Controlling the Electronic Properties and Oxidative Activities of Birnessite Minerals. ACS Earth and Space Chemistry, 7(4), 774-787.

- Roychoudhury, C., He, C., Kumar, R., & Arellano Jr, A. F. (2025). Diagnosing aerosol–meteorological interactions on snow within Earth system models: a proof-of-concept study over High Mountain Asia. Earth System Dynamics, 16(4), 1237-1266.

- Dash, P. K., Chen, C., Kaminski, R., Su, H., Mancuso, P., Sillman, B., ... & Khalili, K. (2023). CRISPR editing of CCR5 and HIV-1 facilitates viral elimination in antiretroviral drug-suppressed virus-infected humanized mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(19), e2217887120.

- Sun, X., Meng, K., Wang, W., & Wang, Q. (2025, March). Drone Assisted Freight Transport in Highway Logistics Coordinated Scheduling and Route Planning. In 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT) (pp. 1254-1257). IEEE.

- Oyegbile, O. O. Modeling the influence of biomass burning haze on extreme rainfall events (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nottingham).

- Wang, Y., Shen, M., Wang, L., Wen, Y., & Cai, H. (2024). Comparative Modulation of Immune Responses and Inflammation by n-6 and n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Oxylipin-Mediated Pathways.

- Fakoya, A. A., Redemann, J., Saide, P. E., Gao, L., Mitchell, L. T., Howes, C., ... & Flynn, C. J. (2025). Atmospheric processing and aerosol aging responsible for observed increase in absorptivity of long-range-transported smoke over the southeast Atlantic. Atmospheric chemistry and physics, 25(14), 7879-7902.

- Xu, K., Lu, Y., Hou, S., Liu, K., Du, Y., Huang, M., ... & Sun, X. (2024). Detecting anomalous anatomic regions in spatial transcriptomics with STANDS. Nature Communications, 15(1), 8223.

- Silva, K. M. R. D., Herdies, D. L., Kubota, P. Y., Bresciani, C., & Figueroa, S. N. (2025). Impact of Aerosols on Cloud Microphysical Processes: A Theoretical Review. Geosciences (2076-3263), 15(8).

- Althaf, P., Kumar, K. R., & Kannemadugu, H. B. S. (2024). Aerosol optical depth over the Andhra Pradesh state in south India from reanalysis data: Spatiotemporal variabilities and machine learning approach. Earth Systems and Environment, 1-25.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).