1. Introduction

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is recognized as one of the most dangerous forms of air pollution, capable of penetrating deep into the lungs and bloodstream, contributing to cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses. Globally, urban areas face growing exposure, with cities in sub-Saharan Africa showing rapidly increasing PM2.5 levels due to population growth, unregulated transport emissions, open burning, and industrial activities. However, a significant barrier to understanding air quality dynamics in African cities remains the scarcity of long-term ground-based monitoring. This challenge has been compounded by the recent cessation of air quality data sharing by United States embassies across several African countries, cutting off one of the few consistent sources of reference-grade PM2.5 data. Against this backdrop, reanalysis products such as NASA’s Mod(NASA Global Modeling and Assimilation Office [GMAO], 2015) ern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications Version 2 (MERRA-2) provide a valuable alternative. This study leverages the long-term availability and spatial coverage of MERRA-2 data to characterize PM2.5 patterns over Accra, Ghana, offering both historical context and a template for data-driven air quality management.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Source and Derivation

MERRA-2 provides assimilated aerosol diagnostics from satellite and ground observations. PM2.5 concentrations were derived from the tavg1_2d_aer_Nx collection using the following fields: DUSMASS25, OCSMASS, BCSMASS, SSSMASS25, and SO4SMASS. The total surface PM2.5 was calculated following GMAO (2015) recommendations: PM2.5 = DUSMASS25 + OCSMASS + BCSMASS + SSSMASS25 + SO4SMASS * (132.14/96.06).

2.2. Spatial and Temporal Resolution

The native spatial resolution of MERRA-2 is 0.5° latitude by 0.625° longitude (~55 km x 69 km), allowing for regional-scale analysis. Temporal resolution included both daily and monthly averages. Data extraction focused on the grid cell containing Accra Technical University, representing a significant urban area within the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA).

3. Results: Temporal Trends of PM2.5 (1980–2019)

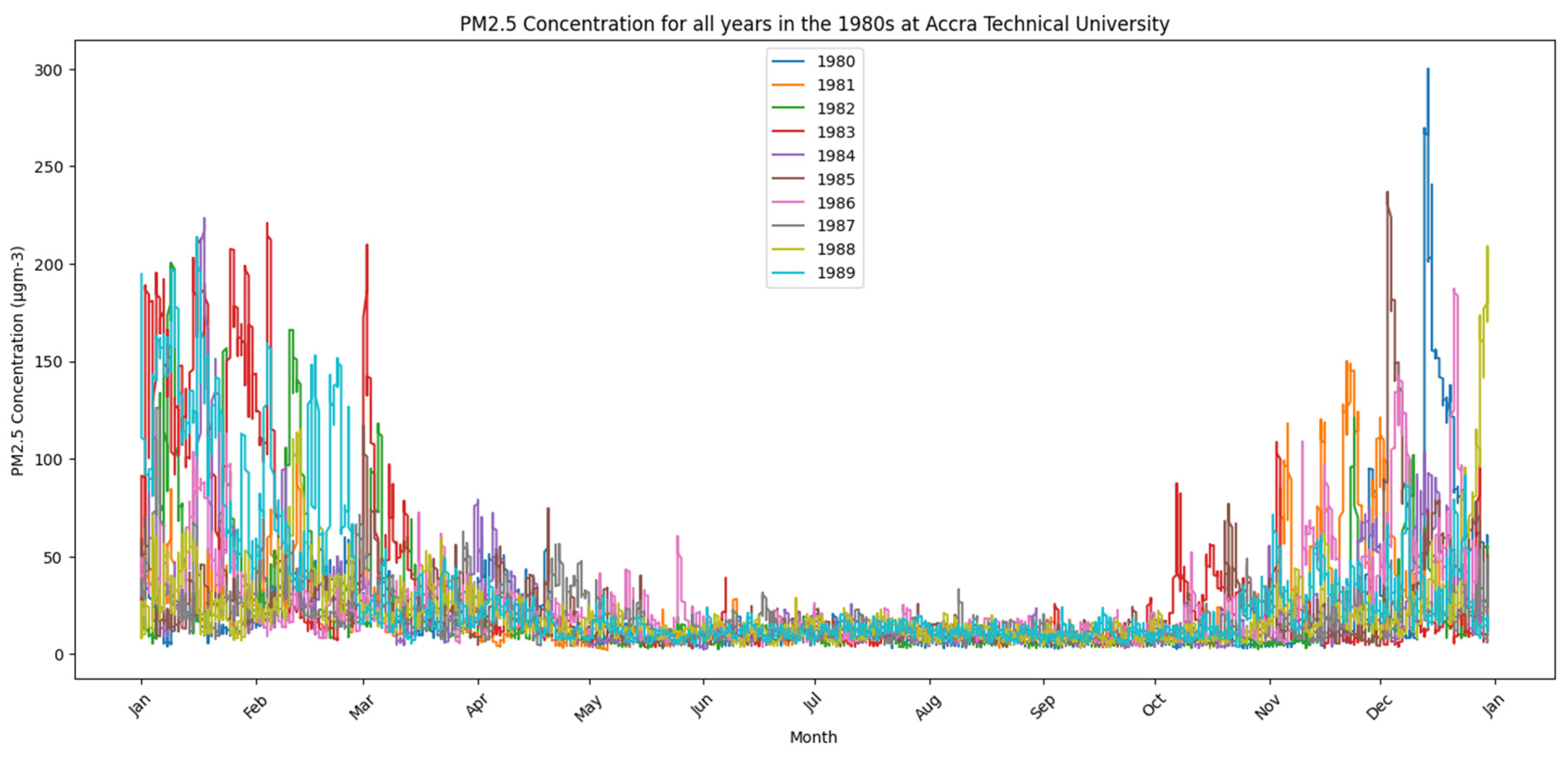

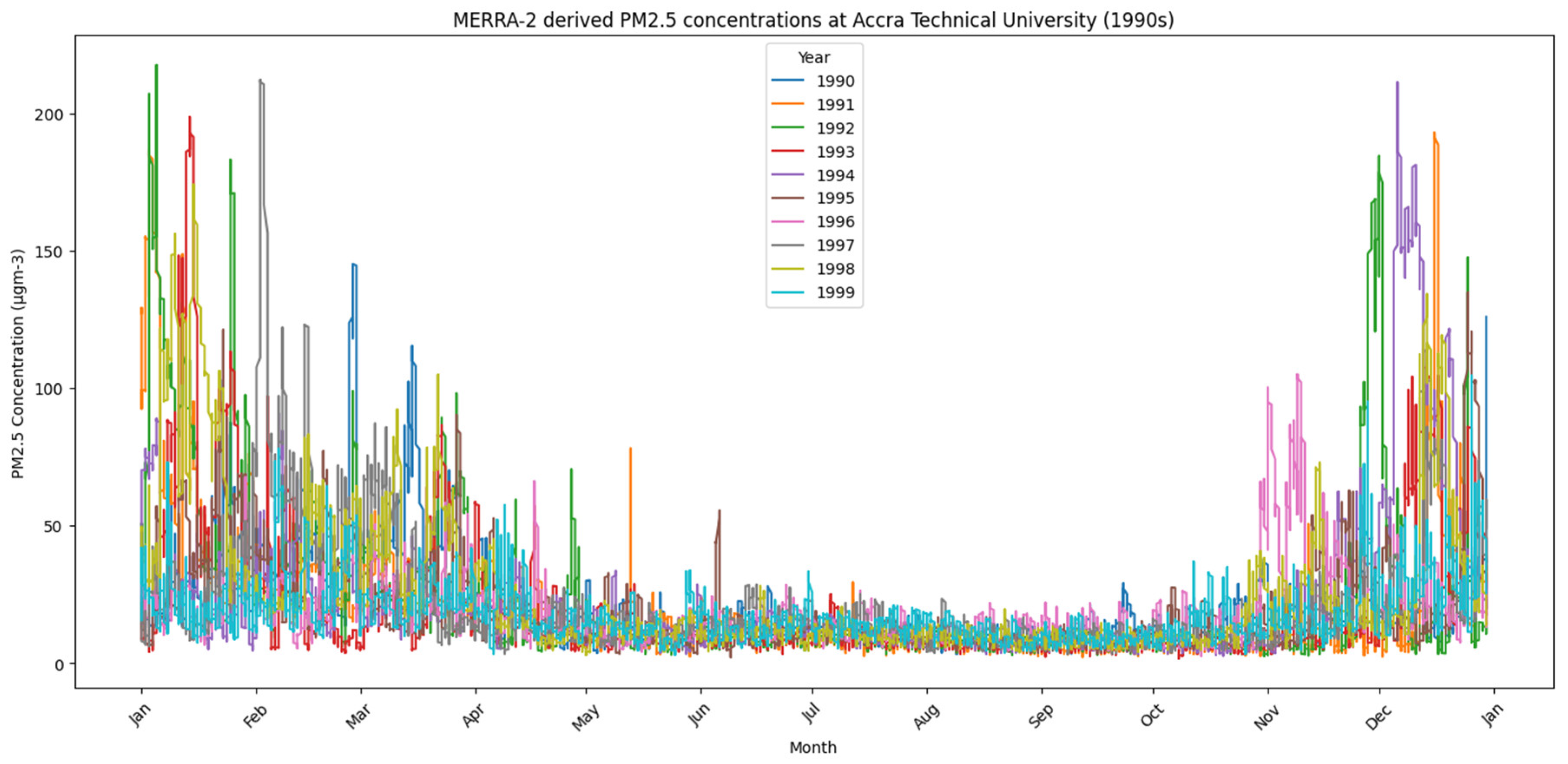

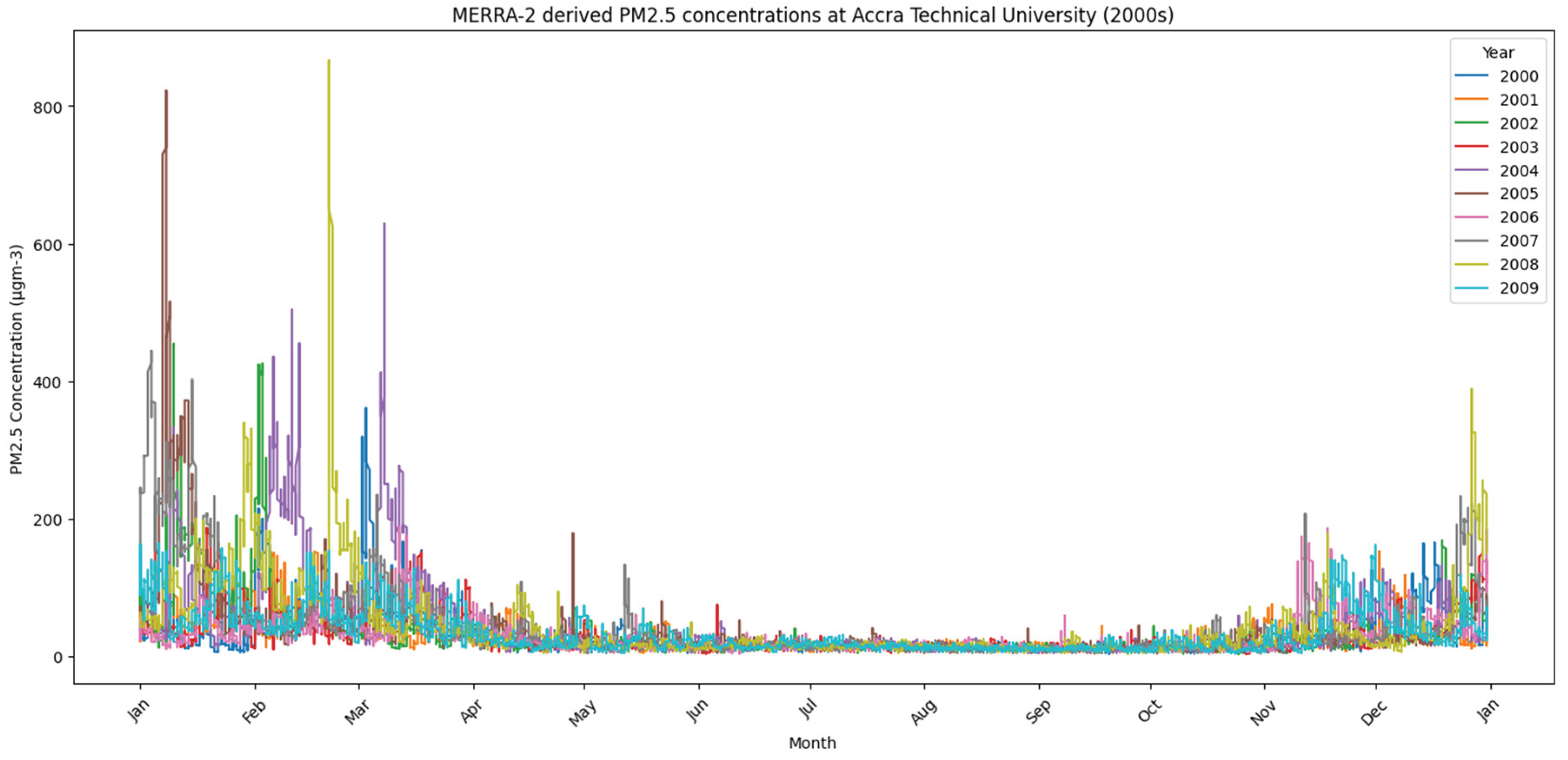

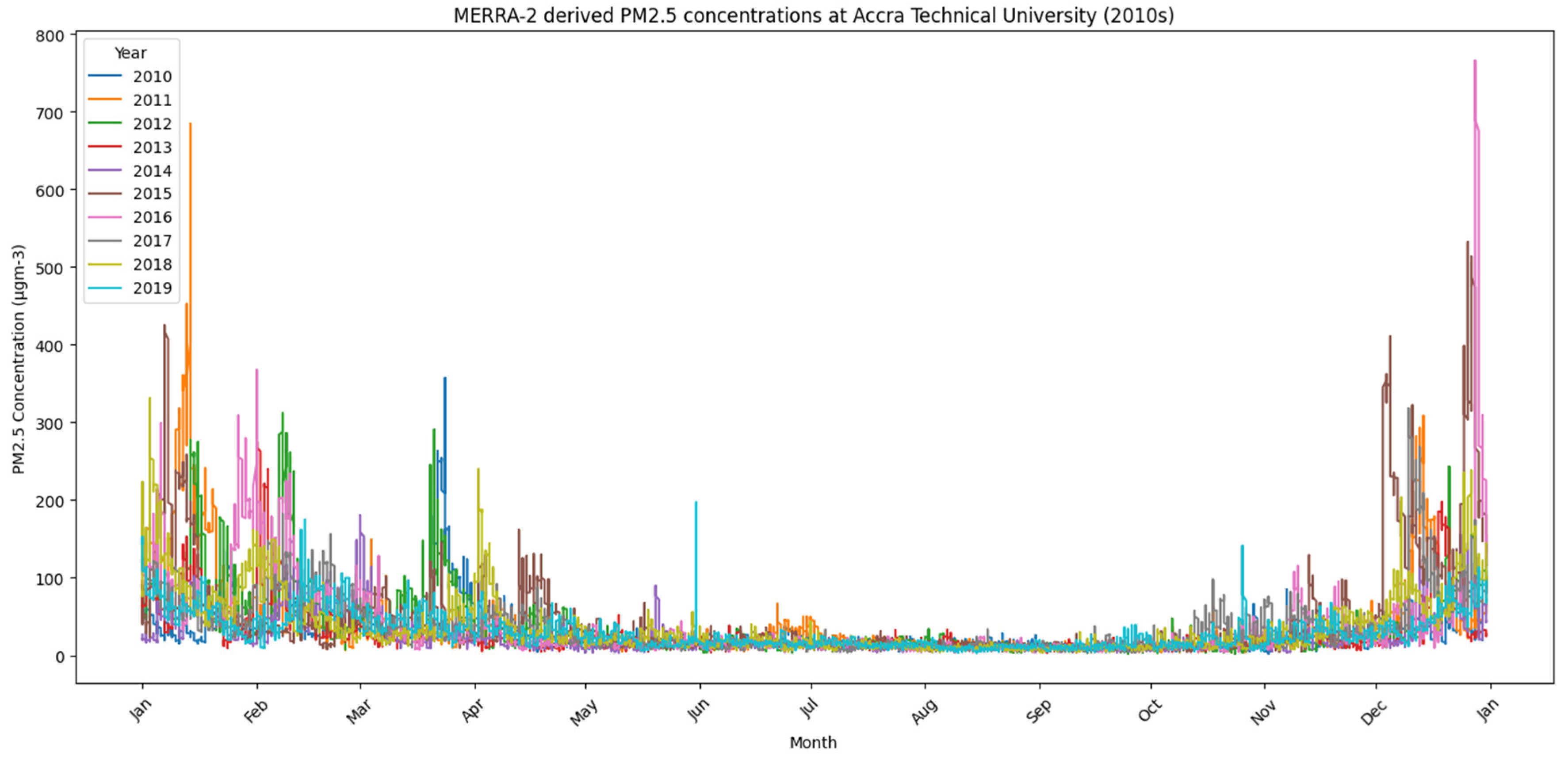

Time-series plots for each decade (1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s) indicate a consistent seasonal trend, with elevated PM2.5 concentrations from November to March, corresponding to the Harmattan season. While year-to-year variability exists, the following general trends were noted: - 1980s: Frequent peaks above 250 µg/m3 in early months, with low background levels mid-year.

4. Discussion

The persistently high PM

2.

5 concentrations in the 2000s and 2010s as shown in

Figure 3 &

Figure 4 respectively, particularly during the Harmattan season, pose significant public health risks—notably for respiratory and cardiovascular health. Based on the findings, it was observed that relatively low PM2.5 concentrations were reported during the first two decades, as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 respectively. Studies in Accra have shown that elevated PM

2.

5 levels at traffic hotspots are associated with increased reports of coughing, chest pain, irregular heartbeat, and other cardiovascular symptoms among street traders and informal workers (Arku et al., 2020). The detrimental impact of air pollution on human health is a pressing concern, particularly in urban environments like Accra, Ghana. Informal e-waste recycling activities, often characterized by inadequate safety measures, contribute significantly to elevated levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5). Occupational exposure to PM2.5 among e-waste workers has been shown to impair pulmonary function, increasing their susceptibility to chronic respiratory diseases such as COPD and bronchitis (Bornman et al., 2022).

These findings underscore the urgent need for interventions to mitigate air pollution and protect the health of vulnerable populations engaged in informal recycling sectors.

Satellite-based health risk assessments have found annual PM2.5 levels in major Ghanaian cities well above WHO guidelines—often exceeding 50 μg/m3—contributing to tens of thousands of premature deaths and reducing life expectancy by several years (Apte et al., 2019). In children with asthma across sub-Saharan Africa, even modest increases in PM2.5 exposure led to higher frequencies of respiratory symptoms and decreased lung function (Epton et al., 2018).

Mechanistically, PM2.5 can penetrate deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction—factors implicated in hypertension, atherosclerosis, arrhythmia, and acute myocardial infarction (Brook et al., 2010; Rajagopalan et al., 2018). Even short-term spikes in particulate concentrations have been linked to increased hospital admissions for heart attacks and strokes (WHO, 2021).

Children, older adults, and outdoor workers—common in Ghanaian urban settings—are especially vulnerable to these impacts.

The extreme values of PM2.5 observed in our analysis—sometimes exceeding 800 μg/m3—underscore the urgent need for better air quality controls and health-focused interventions in Accra. High pollution days exacerbate acute health outcomes, while seasonal mean exposures likely contribute to chronic disease burdens. The sustained nature of exposure indicated by our four-decade time series further suggests that both immediate and long-term health strategies are imperative.

Establishing continuous monitoring (via integrated satellite-ground systems like ours) alongside public health surveillance could help identify exposure–outcome linkages over time. Coupled with targeted policies—such as regulating biomass burning, reducing vehicle emissions, and implementing traffic controls in hotspots—this evidence base supports protective action for high-risk populations. In low-resource settings like Ghana, satellite-derived datasets offer crucial tools to fill monitoring gaps and inform health-protective strategies.

The high PM2.5 concentrations during the Harmattan season are primarily driven by transboundary dust transport from the Sahara Desert, compounded by local emissions. The variability across decades may reflect changes in regional climate conditions, urbanization rates, fuel types, and policy responses. The use of satellite-derived PM2.5 data such as MERRA-2, with a coarse spatial resolution of ~55 km, presents notable limitations in capturing the hyperlocal air quality variations typical of a city like Accra, where emission sources—such as traffic, informal waste burning, and industrial activity—are highly localized. This spatial averaging effect can obscure neighborhood-level pollution hotspots and reduce the utility of the data for targeted interventions. Additionally, satellite-based estimates carry uncertainties stemming from the AOD-to-PM2.5 conversion process, meteorological variability, and retrieval errors under conditions like cloud cover or bright surfaces. In this study, satellite data overestimated PM2.5 in 2020 and underestimated it in 2019, indicating potential annual biases. To address these issues, we integrated data from co-located ground-based low-cost sensors and a reference-grade monitor to validate and contextualize the satellite outputs. By synchronizing datasets temporally and applying statistical validation, we mitigated discrepancies and improved the reliability of spatial interpretations. While satellite data alone may not resolve fine-scale urban gradients, their integration with ground-based monitoring provides a more robust and scalable approach for air quality assessment in resource-constrained settings. This is particularly crucial given the sparse network of ground-based monitors in Ghana.

Another important consideration in the use of satellite-derived PM2.5 data, such as MERRA-2, is its inherently complex or “black box” nature. The data are generated through advanced data assimilation techniques that integrate multiple satellite inputs and meteorological reanalysis fields. While this modeling framework offers consistent, large-scale coverage, its internal processes are not always transparent to non-expert audiences, which can limit public understanding and trust. Additionally, the temporal granularity and latency of MERRA-2—typically designed for climatological analysis rather than real-time monitoring—make it less responsive for short-term decision-making or immediate public health advisories. However, this limitation presents an opportunity rather than a drawback. When MERRA-2 outputs are paired with near-real-time data from low-cost sensors, they can be used to enhance the credibility and spatial coverage of local observations while offering a broader temporal context. To improve public relevance and awareness, findings can be translated into health-oriented messaging through mobile platforms, community dashboards, or simplified infographics. By demystifying the origin and interpretation of satellite-based air quality data, such approaches can help bridge the gap between scientific modeling and community-level action, ultimately making satellite data a more relatable and impactful tool for air quality management.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates the feasibility and value of using MERRA-2 satellite-derived reanalysis data to analyze long-term PM2.5 trends in West Africa. With four decades of data, it provides one of the most comprehensive temporal assessments of air pollution over Accra. In the face of growing health risks and data accessibility challenges, such satellite-derived archives offer a vital resource for environmental research, public health policy, and air quality management.

References

- Apte, J. S., Brauer, M., Cohen, A. J., Ezzati, M., & Pope, C. A. (2019). Ambient PM2.5 reduces global and regional life expectancy. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 6(3), 173–179. [CrossRef]

- Arku, R. E., Birch, A., Shupler, M., & Nethery, E. (2020). Characterizing air pollution exposure for informal street vendors in Accra, Ghana. Atmospheric Environment, 234, 117600.

- Bornman, R., Minet, L., & Green, A. (2022). Health effects of occupational exposure to e-waste among informal workers in Ghana. Environmental Health Perspectives, 130(2), 27001.

- Brook, R. D., Rajagopalan, S., Pope, C. A., Brook, J. R., Bhatnagar, A., & Diez-Roux, A. V. (2010). Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Circulation, 121(21), 2331–2378. [CrossRef]

- Epton, M. J., Dawson, R. D., & Walters, E. H. (2018). Air pollution and children’s respiratory health in sub-Saharan Africa. Pediatric Pulmonology, 53(4), 465–472.

- NASA Global Modeling and Assimilation Office. (2015). MERRA-2 tavg1_2d_aer_Nx: 2-d, time-averaged, single-level, assimilated aerosol diagnostics V5.12.4 [Data set]. Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S., Al-Kindi, S. G., & Brook, R. D. (2018). Air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 72(17), 2054–2070. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). WHO global air quality guidelines: Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. Geneva: World Health Organization.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).