Submitted:

09 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrumental Aspects

2.1.1. Geology of the Study Area

2.1.2. Data Acquisition

2.1.3. Earthquake Related Data

2.2. Theoretical Aspects

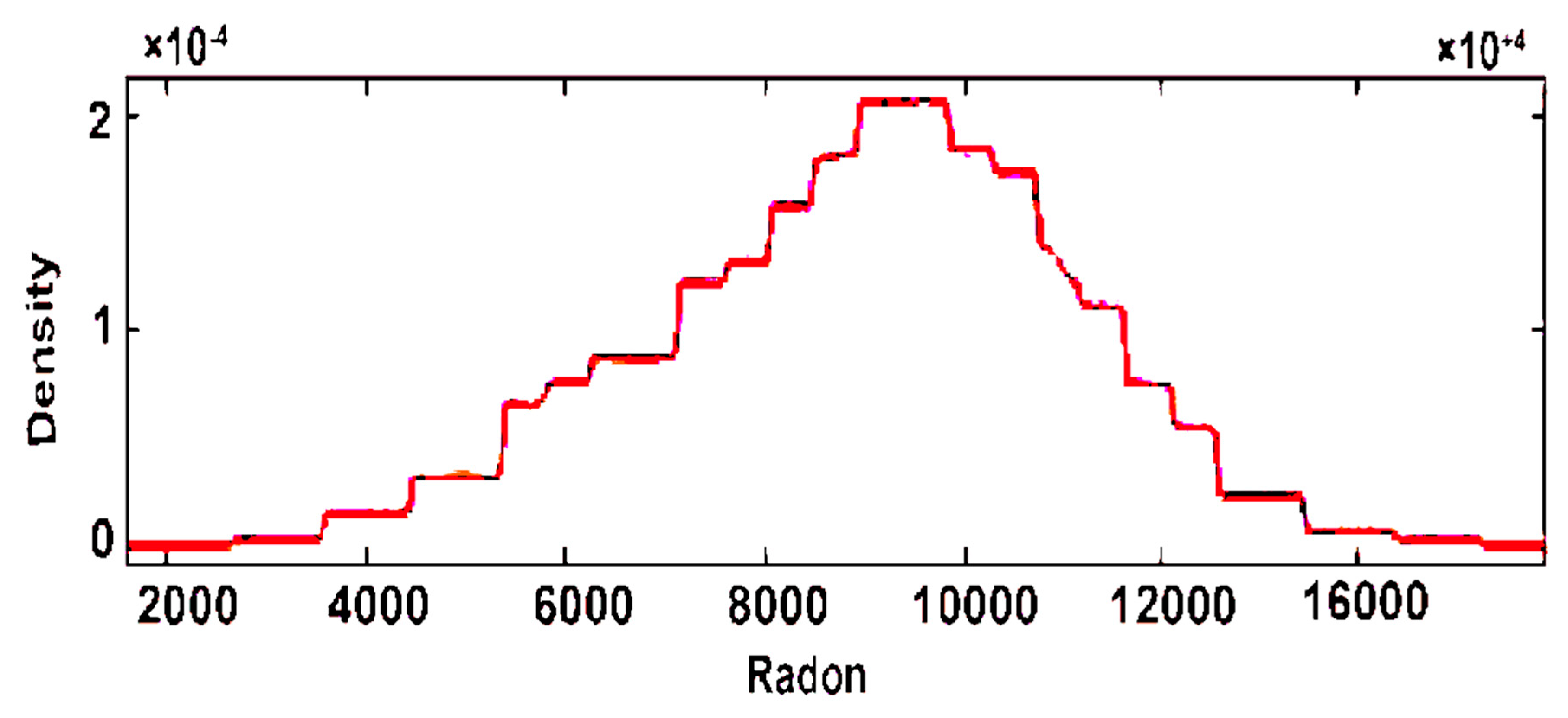

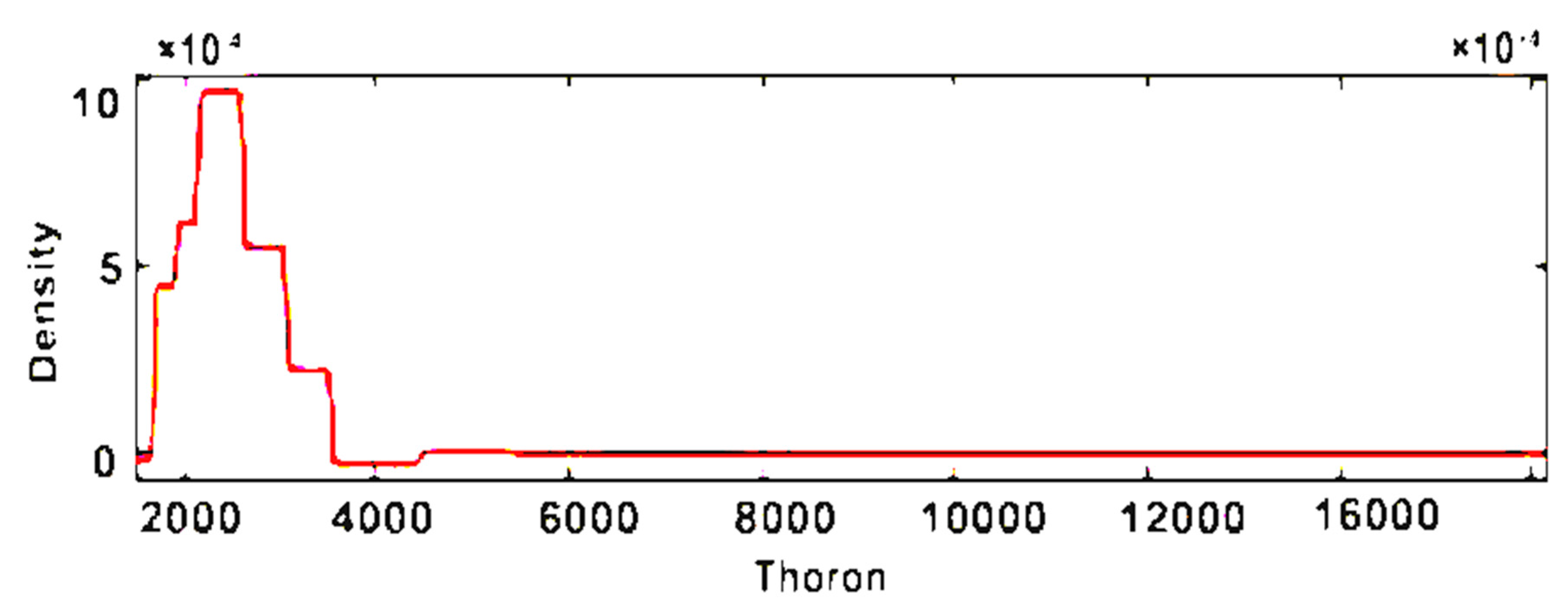

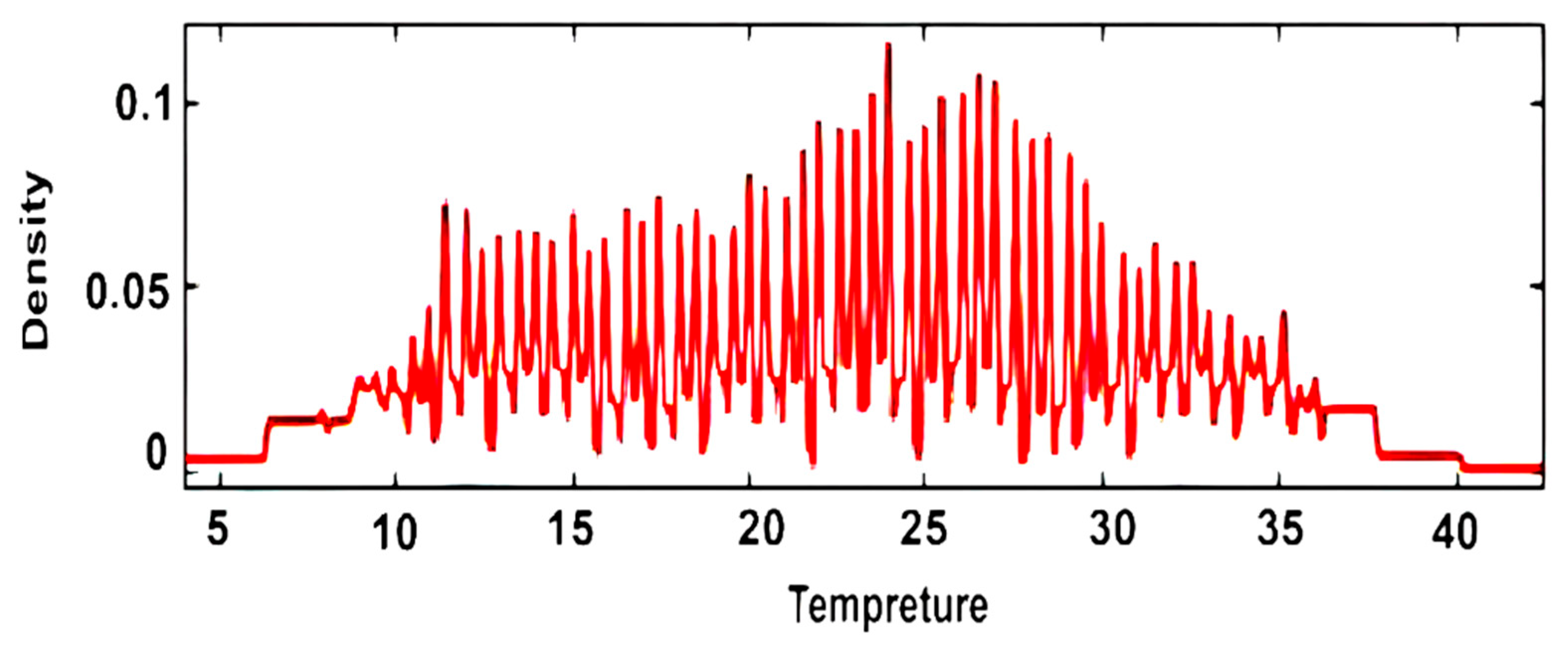

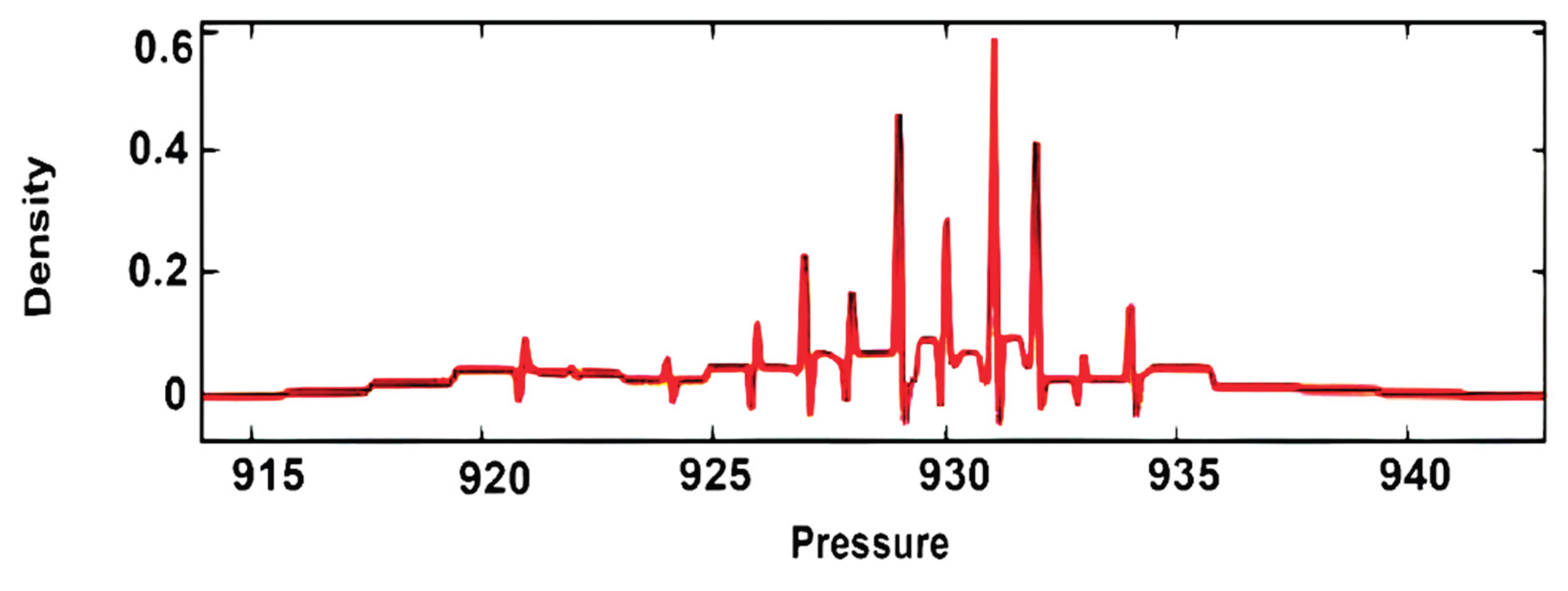

2.2.1. Kernel Density Estimation

2.2.2. Histogram-Based Density Estimation

2.2.3. Wavelet-Based Density Estimation

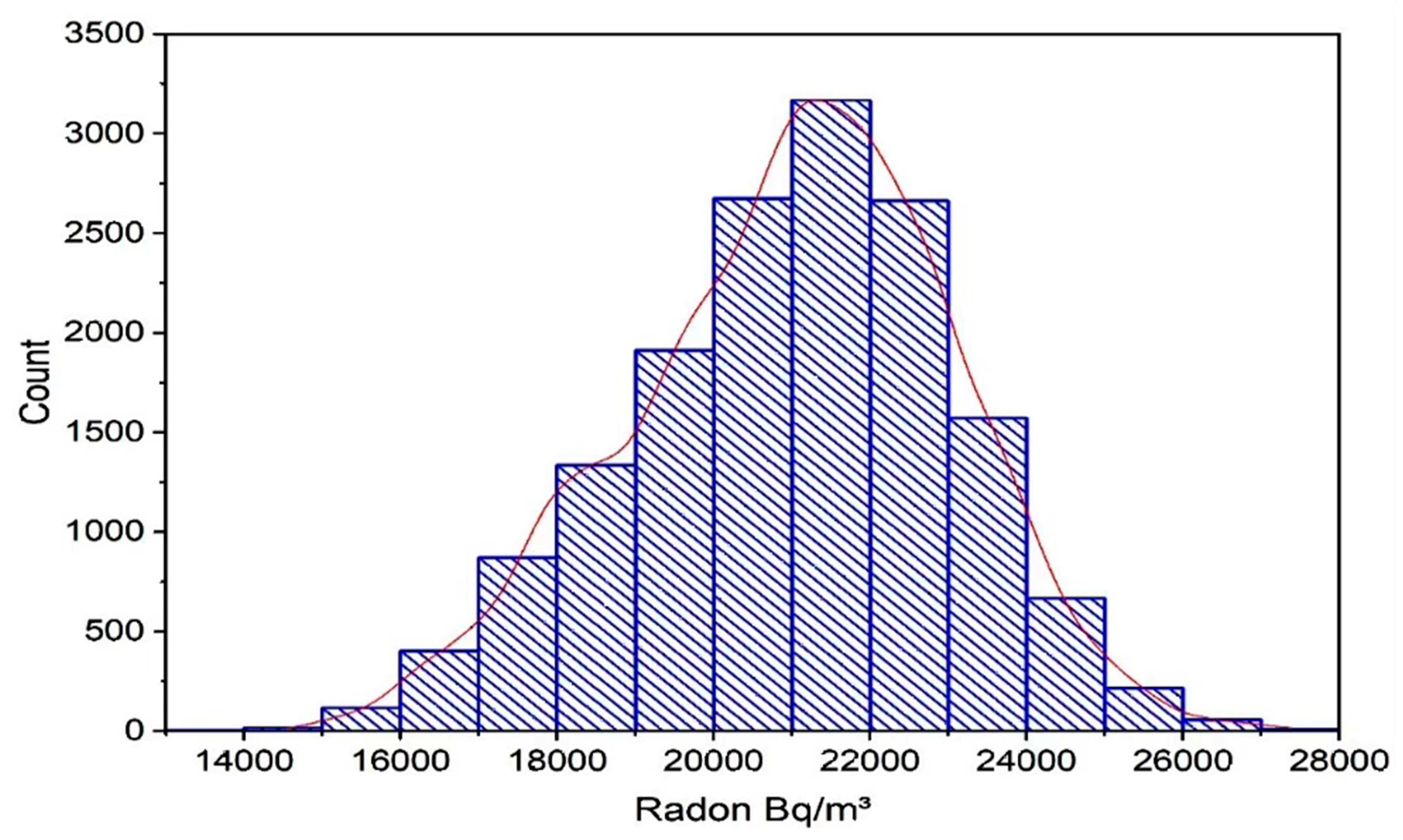

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woith, H.; Petersen, G.; Hainzl, S.; Dahm, T. Review: Can Animals Predict Earthquakes? Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2018, 108, 1031–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuyep, L.C; Kadiri, U.A.; Monday, I.A.; Nansak, N.E. Z, L.T.,; Habila Y.O.; Ezisi P. Geo-Chemical Techniques for Earthquake Forecasting in Nigeria. Asian J. Geogr. Res.. 2021, 4, 29–45, AJGR.72897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placinta, A.O.; Borleanu, F.; Moldovan, I.A.; Coman, A. Correlation between Seismic Waves Velocity Changes and the Occurrence of Moderate Earthquakes at the Bending of the Eastern Carpathians (Vrancea). Acoust. 2022, 4, 934–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Ge, Z. Cascading multi-segment rupture process of the 2023 Turkish earthquake doublet on a complex fault system revealed by teleseismic P wave back projection method. Earthq. Sci. 2024, 37, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Cantzos, D.; Alam, A.; Dimopoulos, S.; Petraki, E. Electromagnetic and Radon Earthquake Precursors. Geosciences 2024, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Picozza, P.; Sotgiu, A. A Critical Review of Ground Based Observations of Earthquake Precursors. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 676766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, M.; Nagahama, H.; Muto, J.; Hirano, M.; Yasuoka, Y. Detection of atmospheric radon concentration anomalies and their potential for earthquake prediction using Random Forest analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetia, T.; Baruah, S.; Dey, C.; Baruah, S.; Sharma, S. Seismic induced soil gas radon anomalies observed at multiparametric geophysical observatory, Tezpur (Eastern Himalaya), India: An appraisal of probable model for earthquake forecasting based on peak of radon anomalies. Nat. Hazards 2022, 111, 3071–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, D.; Sabatino, G.; Magazù, S.; Bella, M.D.; Tripodo, A.; Gattuso, A.; Italiano, F. Distribution of soil gas radon concentration in north-eastern Sicily (Italy): Hazard evaluation and tectonic implications. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S.; Herrera, V.M.V. Earthquake Precursors: The Physics, Identification, and Application. Geosciences 2024, 14, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO) Radon. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/radon-and-health (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Kashkinbayev, Y.; Bakhtin, M.; Kazymbet, P.; Lesbek, A.; Kazhiyakhmetova, B.; Hoshi, M.; Altaeva, N.; Omori, Y.; Tokonami, S.; Sato, H.; et al. Influence of Meteorological Parameters on Indoor Radon Concentration Levels in the Aksu School. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Lv, W.; Huang, R.; Feng, Y.; Luo, O.; Yin, C.; Yang, Y. Impact of environmental factors on atmospheric radon variations at China Jinping Underground Laboratory. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Featured anomaly detection methods and applications. PhD thesis, University of Exeter, Computer Science Department, United Kingdom, June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rafique, M.; Tareen, A.D.K.; Mir, A.A.; Sajjad, M.; Nadeem, A.; Asim, K.M.; Kearfott, K.J. Delegated Regressor, A Robust Approach for Automated Anomaly Detection in the Soil Radon Time Series Data. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C. A Tutorial on Kernel Density Estimation and Recent Advances. Biostatistics & Epidemiology 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzen, E. On Estimation of a Probability Density Function and the Mode. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1962, 33, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxhammar, R.; Falkman, G.; Sviestins, E. Anomaly detection in sea traffic - A comparison of the Gaussian Mixture Model and the Kernel Density Estimator. In Proceedings of the 2th International Conference on Information Fusion, Seattle, WA, USA, 6–9 July 2009; pp. 756–763. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5203766.

- Ramanna, C. K.; Dodagoudar, G. R. Seismic hazard analysis using the adaptive Kernel density estimation technique for Chennai City. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2012, 169, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, J.; Karim, R. Adaptive kernel density-based anomaly detection for nonlinear systems. Knowledge-Based Systems 2018, 139, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordestani, M.; Alkhateeb, A.; Rezaeian, I.; Rueda, L.; Saif, M. A new clustering method using wavelet based probability density functions for identifying patterns in time-series data. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE EMBS International Student Conference (ISC), Ottawa, ON, Canada; 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Treviño, E.S.; Barria, J.A. Online wavelet-based density estimation for non-stationary streaming data, Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2012, 56, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, M.; Rahman, A.-U.; Samiullah; Khan, A. Extent and evaluation of flood resilience in Muzaffarabad City, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. Journal of Himalayan Earth Sciences 2021, 54, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Baig, M. S.; Lawrence, R.D.; Snee, L.W. Precambrian to early Cambrian orogeny in the northwest Himalaya, Pakistan. Geolog. Mag. 1988, 125, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Wang, N.; Zhao, G.; Barkat, A. Implication of Radon Monitoring for Earthquake Surveillance Using Statistical Techniques: A Case Study of Wenchuan Earthquake Geofluids. 2020, 2429165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, H.; Nakata, T.; Tsutsumi, H.; Kondo, H.; Sugito, N.; Awata, Y.; Kausar, A.B. Surface rupture of the 2005 Kashmir, Pakistan, earthquake and its active tectonic implications. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2008, 98, 521–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS (United States Geological Survey), M 7.6 - 21 km NNE of Muzaffarabad, Pakistan- Pakistan earthquake 2005. Available online: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/usp000e12e/executive (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- SARAD GmbH. 2025. Available online: https://www.sarad.de/product-detail.php (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- National Seismic Monitoring Centre, Islamabad. Available online: https://seismic.pmd.gov.pk/(accessed on Saturday, 1 November, 2025 10:01 PM).

- Dobrovolsky, I.P.; Zubkov, S.I.; Miachkin, V.I. Estimation of the size of earthquake preparation zones. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1979, 117, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, M.; Lazzari, M.; Murgante, B. Kernel Density Estimation Methods for a Geostatistical Approach in Seismic Risk Analysis: The Case Study of Potenza Hilltop Town (Southern Italy). In Lecture Notes in Computer Science Computational Science and Its ApplicationICCSA 2008; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Laganà, A., Taniar, D., Mun, Y., Gavrilova, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008; Volume 5072, pp. 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador Luna, D.; Alonso-Chaves, F.M.; Fernández, C. Kernel Density Estimation for the Interpretation of Seismic Big Data in Tectonics Using QGIS: The Türkiye–Syria Earthquakes (2023). Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.P. Machine learning - a probabilistic perspective. In Adaptive computation and machine learning series. 2012. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:17793133.

- Frehner, R.; Wu, K.; Sim, A.; Kim, J.; Stockinger, J. Detecting Anomalies in Time Series Using Kernel Density Approaches. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 33420–33439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Gao, J.; Li, B.; Wu, O.; Du, J.; Maybank, S. Anomaly Detection Using Local Kernel Density Estimation and Context-Based Regression. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020, 32, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torshizian, H.; Afzal, P.; Rahbar, K.; Yasrebi, A.B.; Wetherelt, A.; Fyzollahhi, N. Application of modified wavelet and fractal modeling for detection of geochemical anomaly. Geochem 2021, 81, 125800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ma, J.; Ye, Y. Regularizing autoencoders with wavelet transform for sequence anomaly detection. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 134, 109084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Rashid, M.M; Johnson, F.; Sharma, A. A wavelet-based tool to modulate variance in predictors: An application to predicting drought anomalies. Environmental Modelling & Software 2021, 135, 104907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Dong, Q.; Hao, M.; Wang, C.; Cao, J. Magnetic anomaly detection based on fast convergence wavelet artificial neural network in the aeromagnetic field. Measurement 2021, 176, 109097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halidou, A.; Mohamadou, Y.; Ari, A. A. A.; Zacko, E. J. G. Review of wavelet denoising algorithms. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 41539–41569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Osama, M.; Rafique, M.; Tareen, A.D.K.; Lone, K.J.; Qureshi, S.A.; Kearfott, K.J.; Aftab, A.; Nikolopoulos, D. Time-frequency analysis of radon and thoron data using continuous wavelet transform. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfaoui, S.; Ben Mabrouk, A.; Cattani, C. Wavelet Analysis: Basic Concepts and Applications, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, US, 2021; pp. 1–254, eBook ISBN 9781003096924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, K. A.; Wegman, E. Nonparametric density estimation of streaming data using orthogonal series. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2009, 53, 3980–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Sharma, A.; Johnson, F. mAssessing the sensitivity of hydro-climatological change detection methods to model uncertainty and bias. Advances in Water Resources 2019, 134, 103430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.V.; Barnard, V.O. Optimal Location Estimation and Anomaly Quantification for a Mobile Information Carrier: Prior Feeds for Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Civil, Structural and Transportation Engineering, Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada, 4–6 June 2023; Avestia Publishing article number 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, T.K.; Jain, M.K.; Yadav, B.K.; Agarwal, A. Multiscale investigation of precipitation extremes over Ethiopia and teleconnections to large-scale climate anomalies. Stoc. Env. Res. Risk 2022, 36, 1503–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

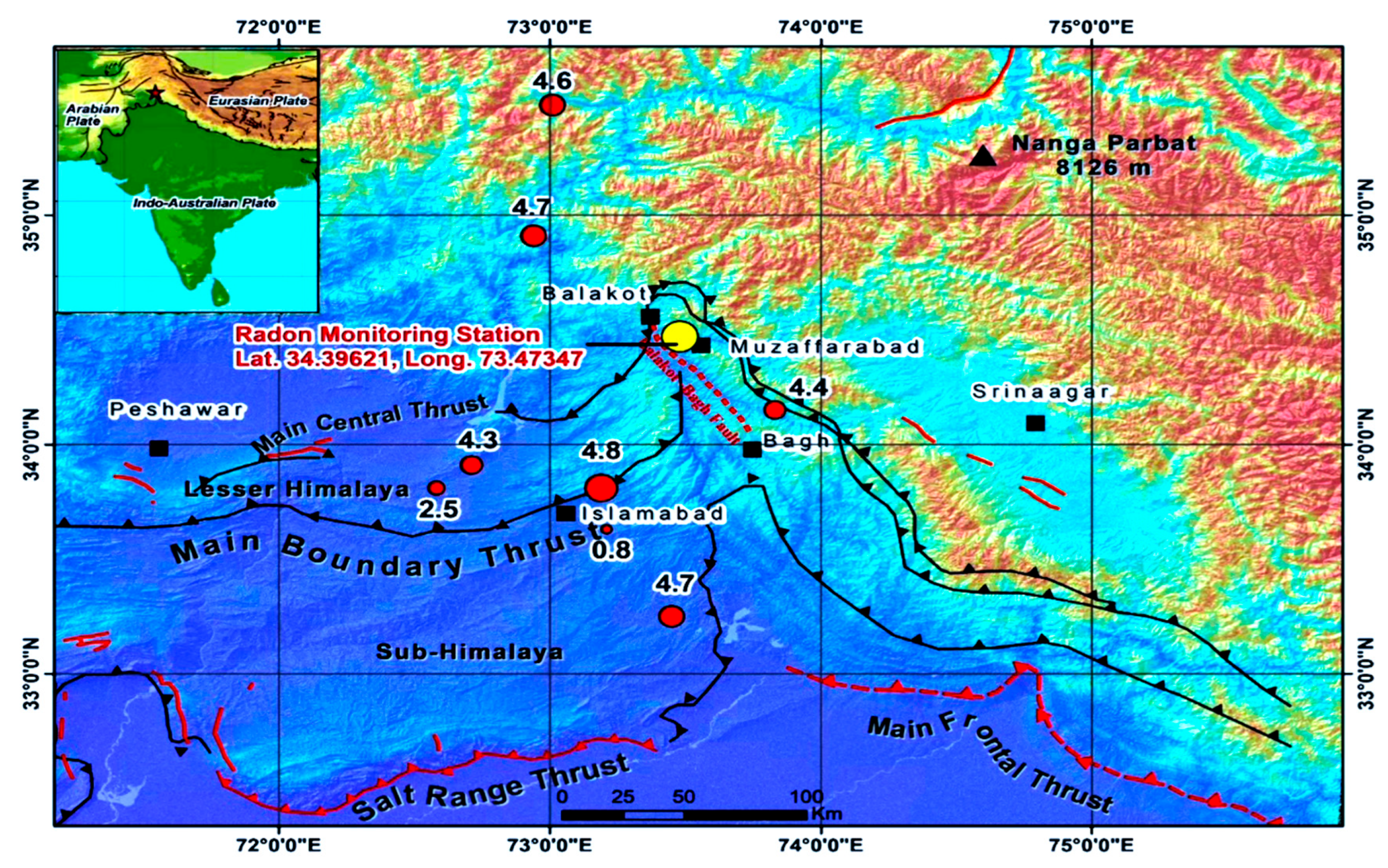

| EQ | Date | Magnitude | Latitude N |

Longitude E |

Depth (km) |

(km) |

(km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ1 | 21/03/2017 | 4.3 | 33.91 N | 72.71 E | 25 | 86.00 | 70.60 |

| EQ2 | 23/03/2017 | 2.5 | 33.81 N | 72.58 E | 156 | 103.0 | 11.89 |

| EQ3 | 27/08/2017 | 4.8 | 33.81 N | 73.19 E | 10 | 66.34 | 115.9 |

| EQ4 | 23/09/2017 | 4.6 | 35.48 N | 73.01 E | 61 | 135.0 | 95.06 |

| EQ5 | 09/12/2017 | 4.7 | 33.25 N | 76.45 E | 101 | 300.0 | 104.9 |

| EQ6 | 03/02/2018 | 0.8 | 33.63 N | 73.21 E | 157 | 142.9 | 2.208 |

| EQ7 | 28/02/2018 | 4.4 | 34.15 N | 73.83 E | 134 | 41.78 | 77.98 |

| EQ8 | 14/03/2018 | 4.9 | 33.93 N | 77.12 E | 10 | 343.0 | 127.9 |

| EQ9 | 15/03/2018 | 4.7 | 33.1 N | 76.14 E | 45 | 284.5 | 105.0 |

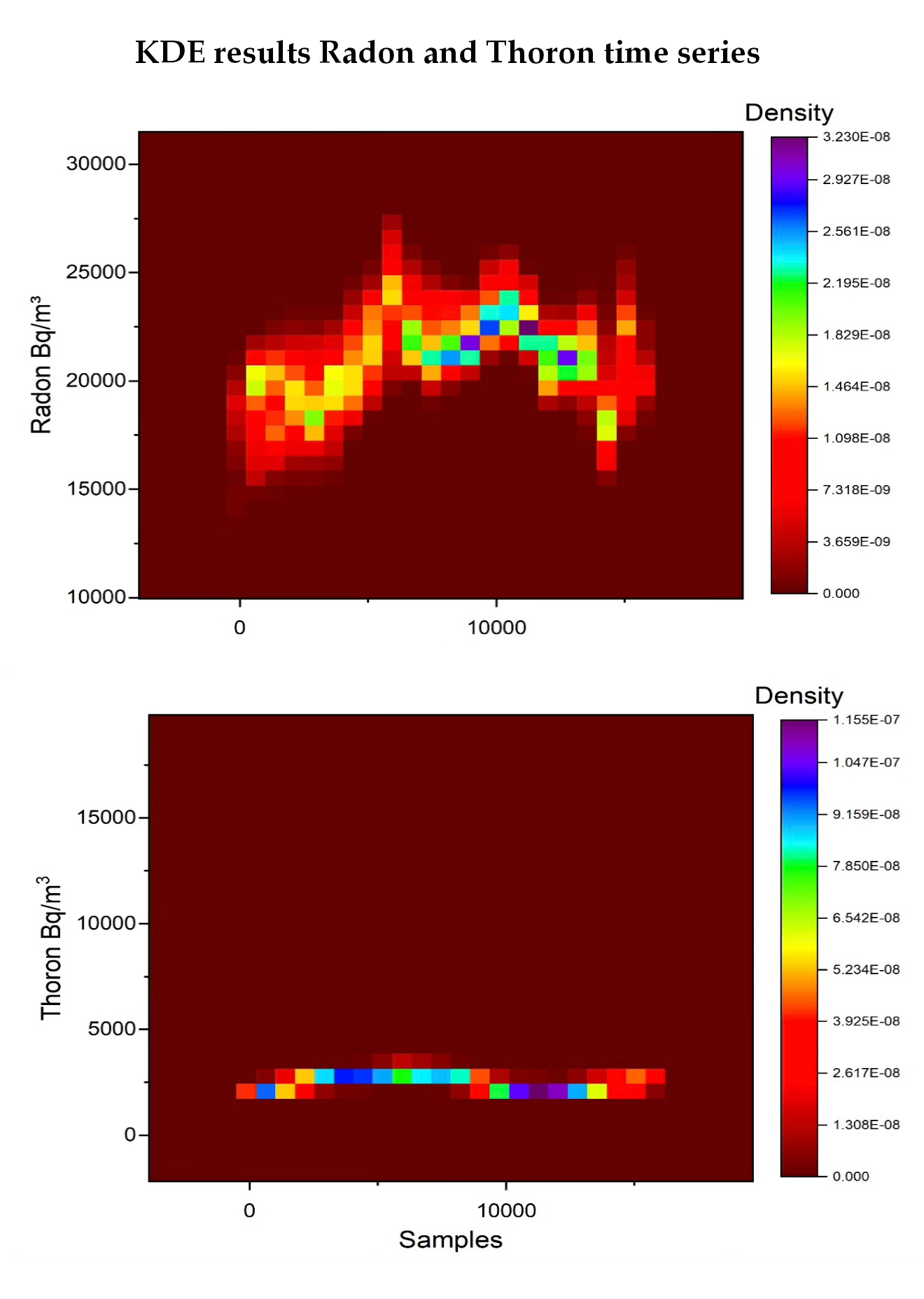

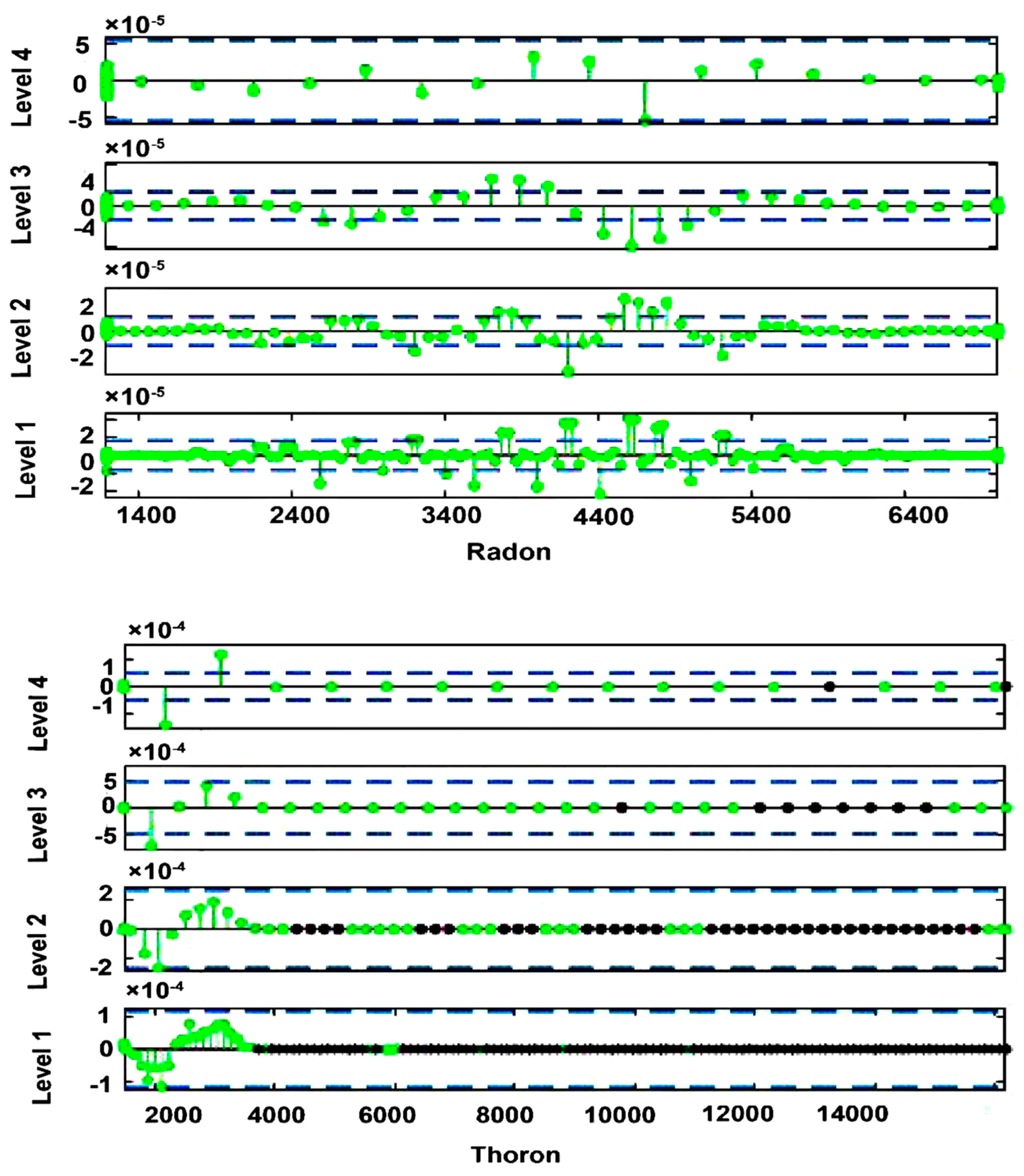

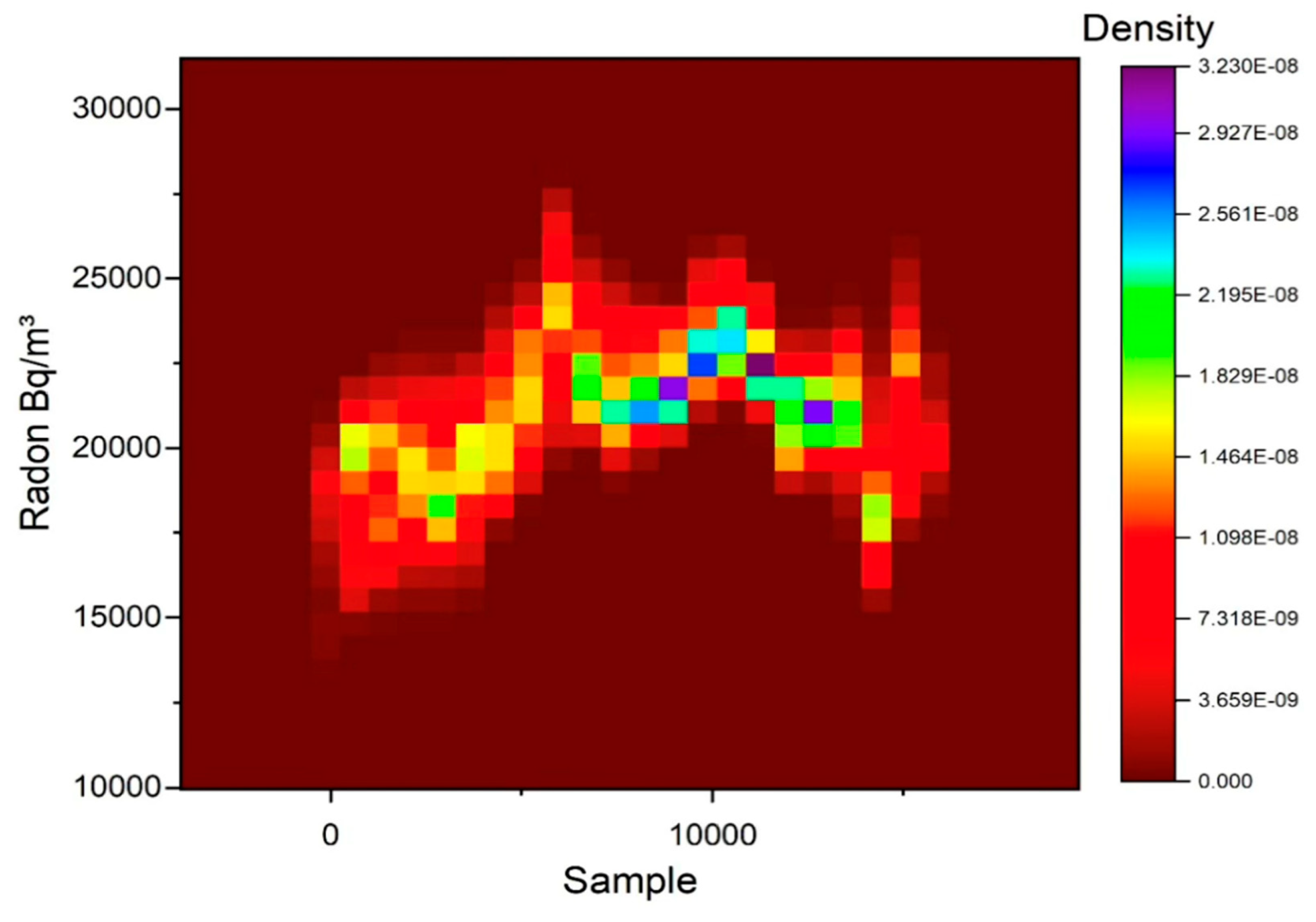

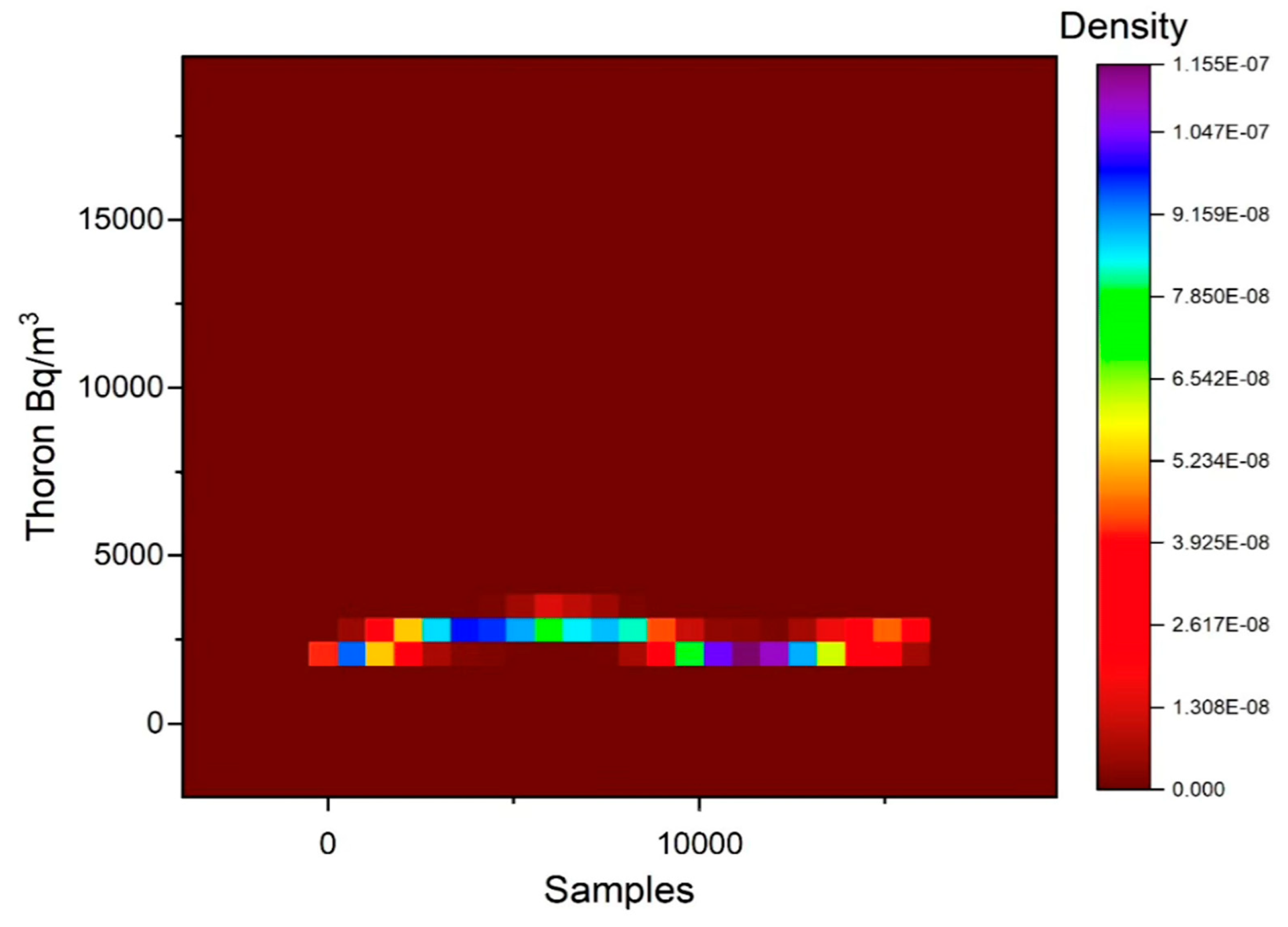

| EQ | Radon time series | Thoron time series | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KDE | WBDE | KDE | WBDE | ||

| EQ1 | 1.46E-08 | 0.11E-04 | 1.30E-08 | 4.63E-04 | |

| EQ2 | 1.09E-08 | 0.26E-04 | 2.62E-08 | 6.71E-04 | |

| EQ3 | 1.83E-08 | 0.95E-04 | 7.85E-08 | 0.12E-04 | |

| EQ4 | 1.46E-08 | 1.23E-04 | 9.16E-08 | 0.12E-04 | |

| EQ5 | 2.19E-08 | 1.12E-04 | 9.16E-08 | 0.12E-04 | |

| EQ6 | 7.32E-09 | 1.56E-04 | 1.55E-07 | 0.12E+04 | |

| EQ7 | 2.93E-08 | 0.42E+04 | 1.05E-07 | 0.12E+04 | |

| EQ8 | 3.65E-09 | 0.31E+04 | 3.93E-08 | 0.12E+04 | |

| EQ9 | 7.32E -09 | 0.11E+04 | 2,62E-08 | 0.12E+04 | |

| Cut-off limit | 3.14E -08 | 4.14E+03 | 1.63E -07 | 1,80E +02 | |

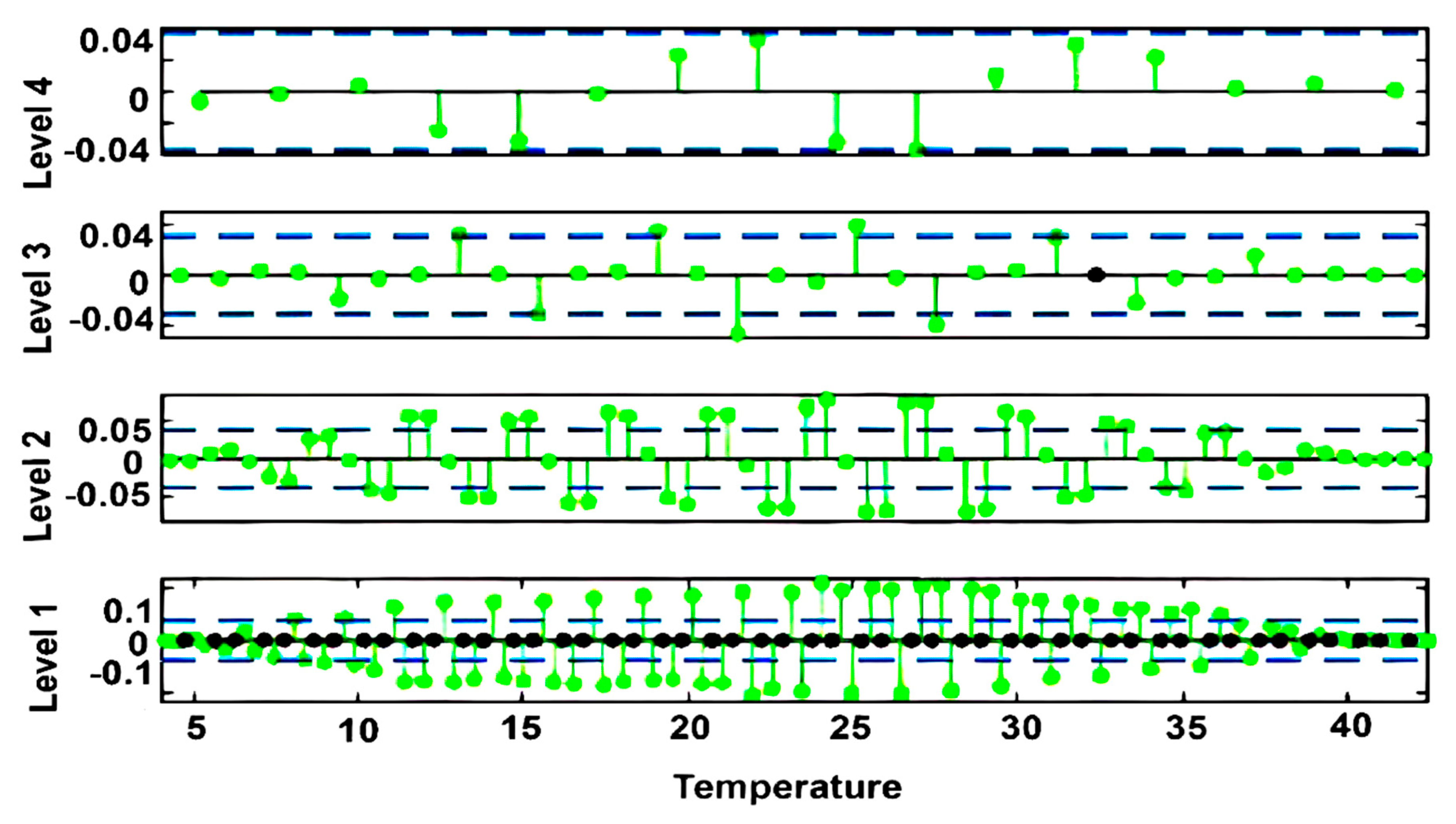

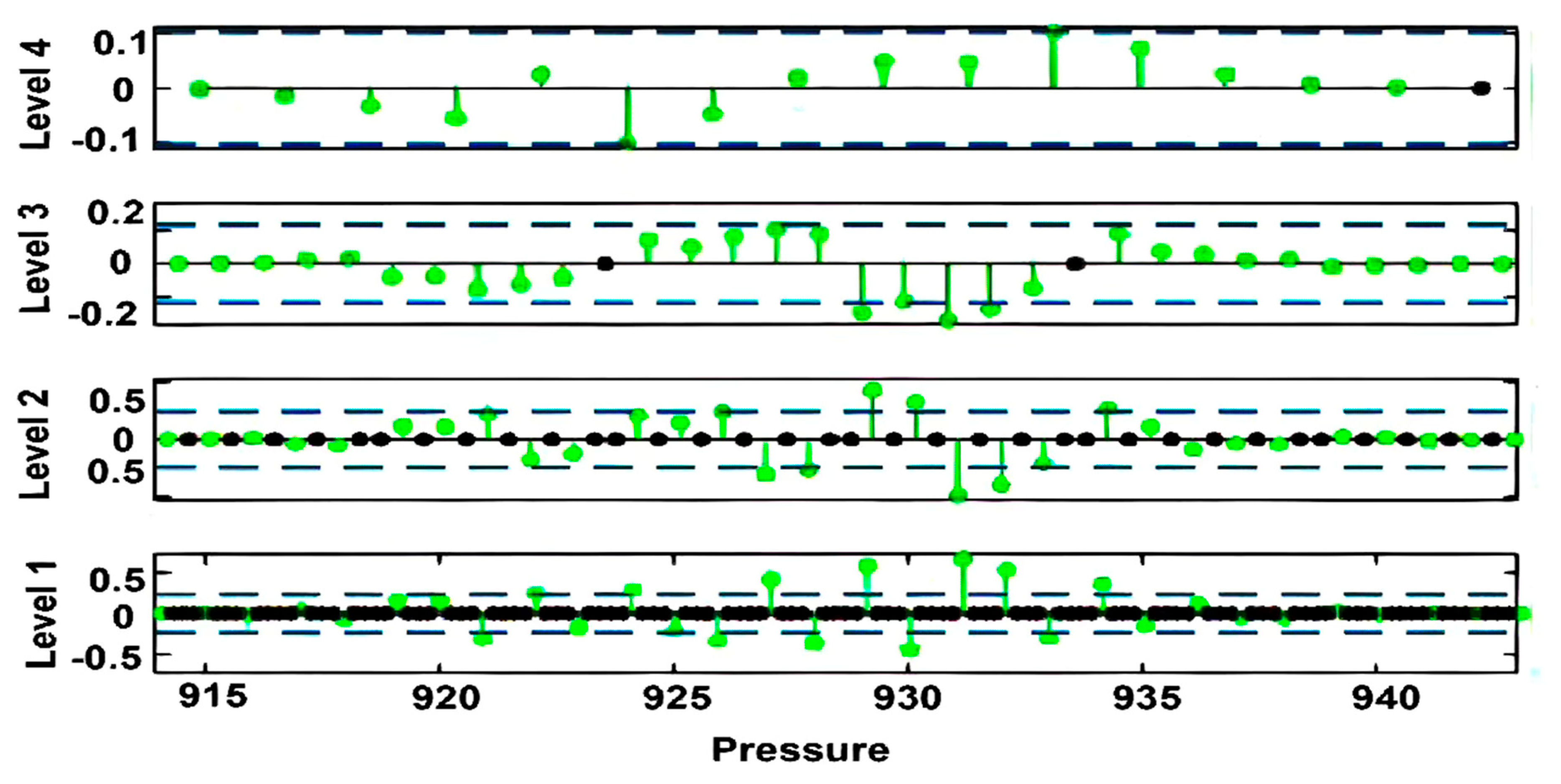

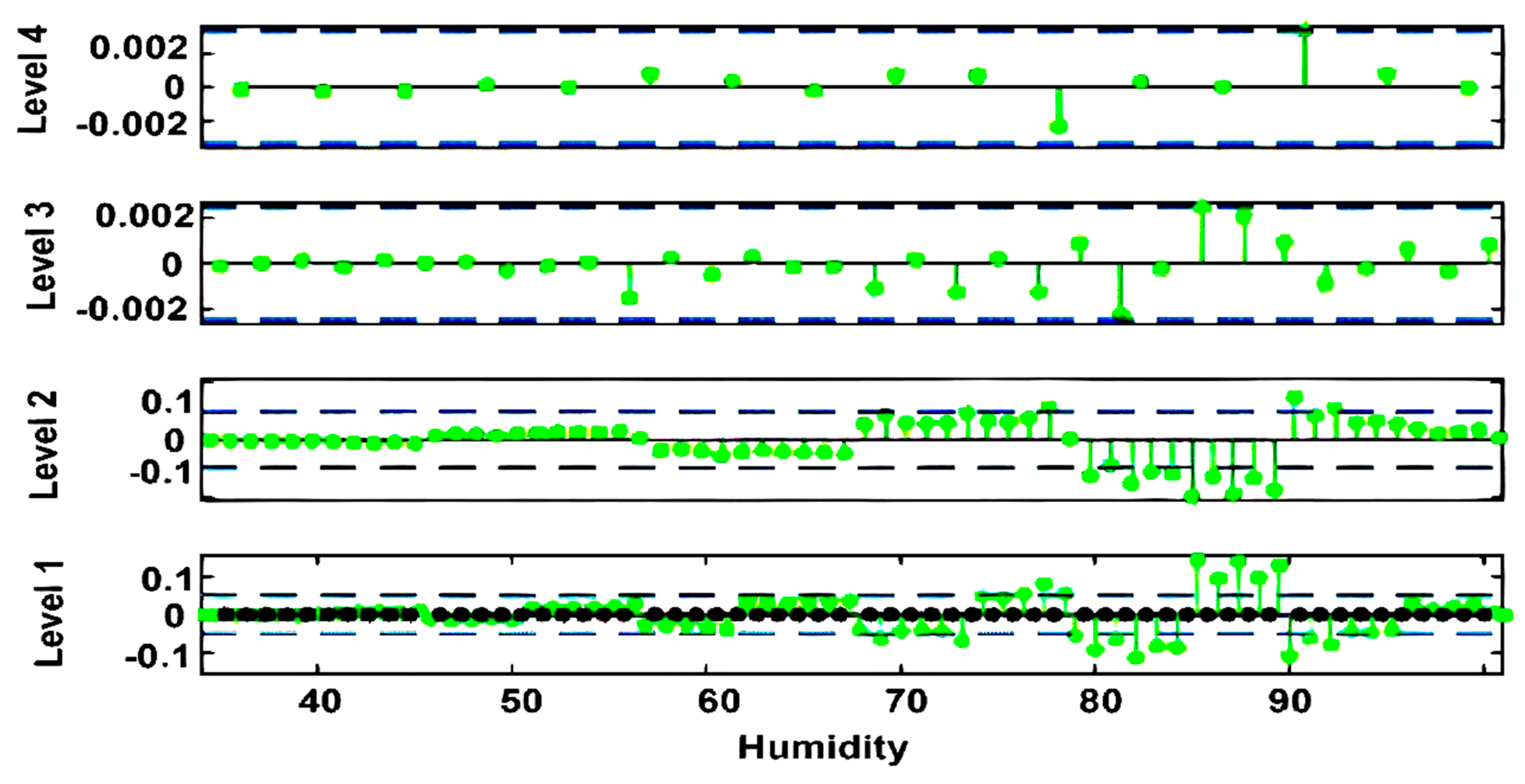

| Type of Variables | Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|

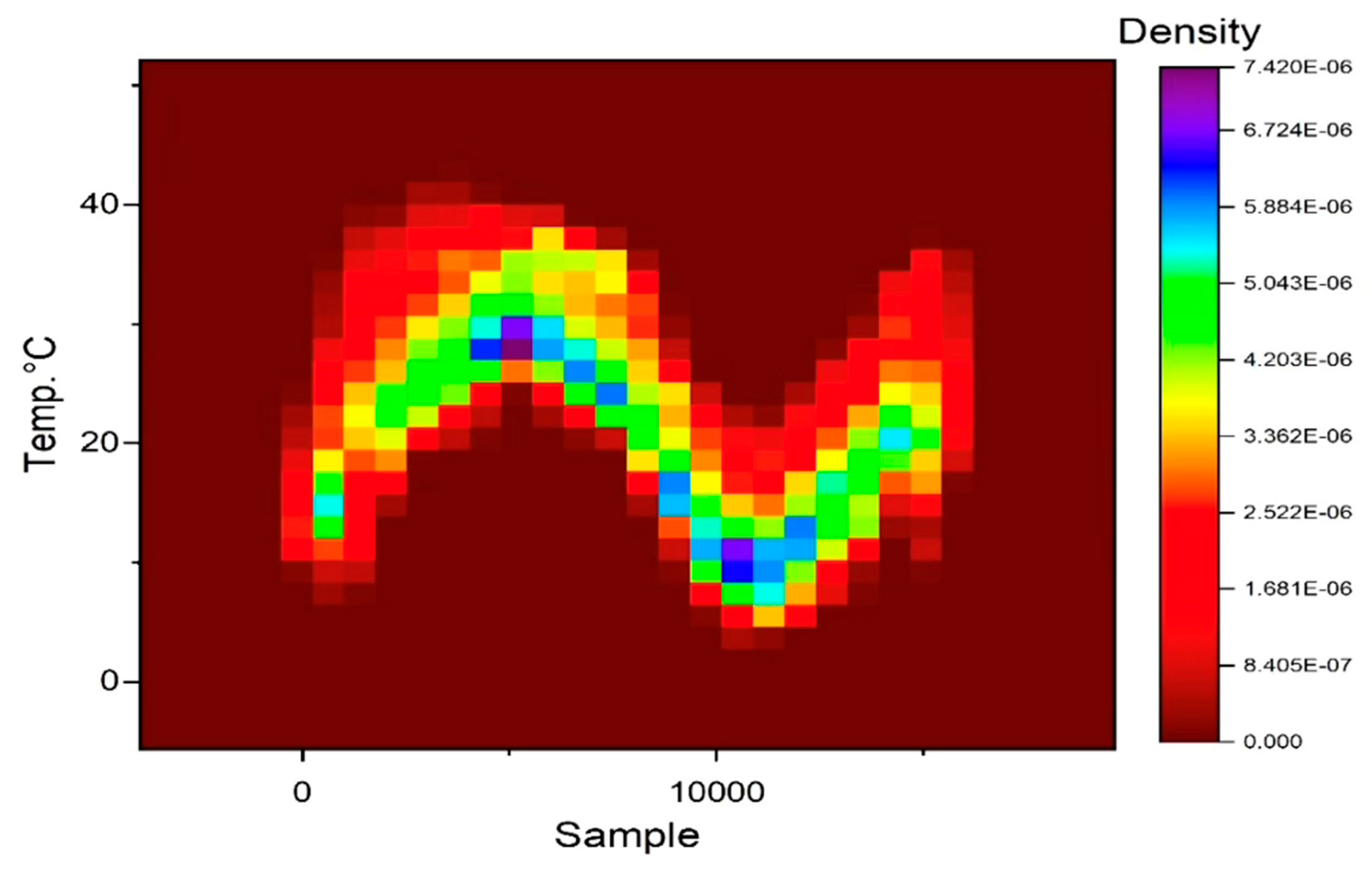

| Radon vs Temperature | -0.141 |

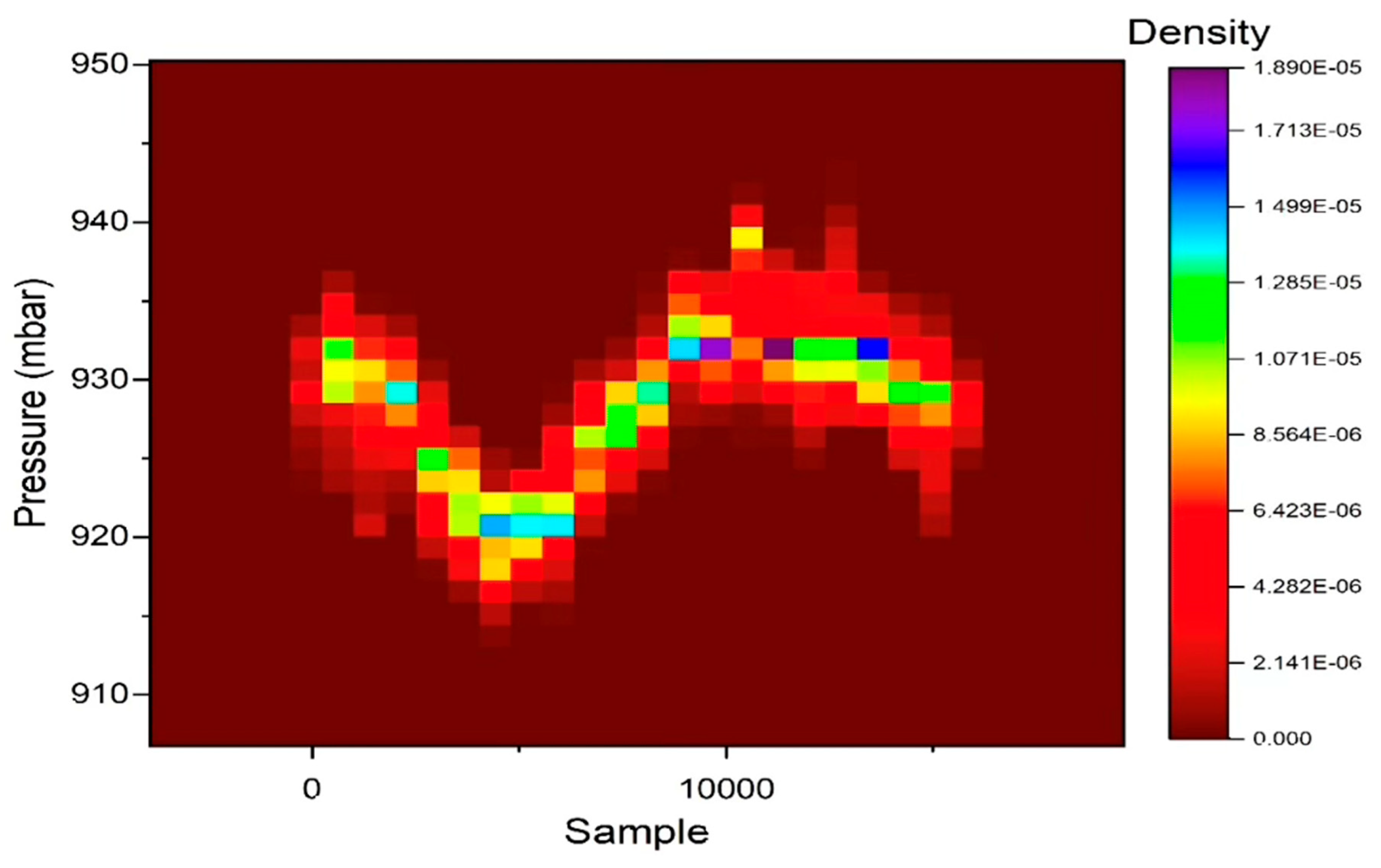

| Radon vs Pressure | 0.121 |

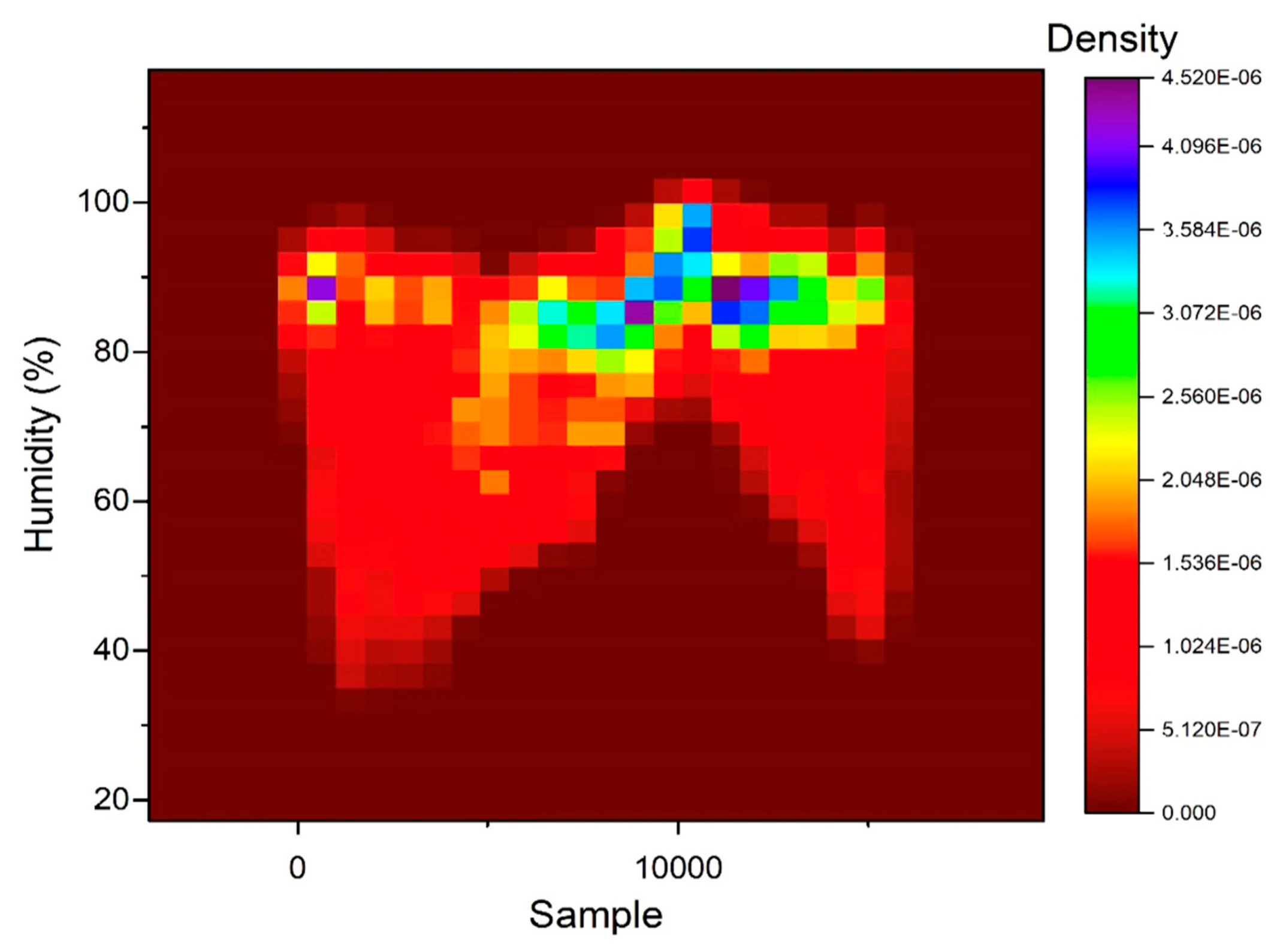

| Radon vs Humidity | 0.432 |

| Thoron vs Temperature | 0.579 |

| Thoron vs Pressure | -0.510 |

| Thoron vs Humidity | -0.211 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).