Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

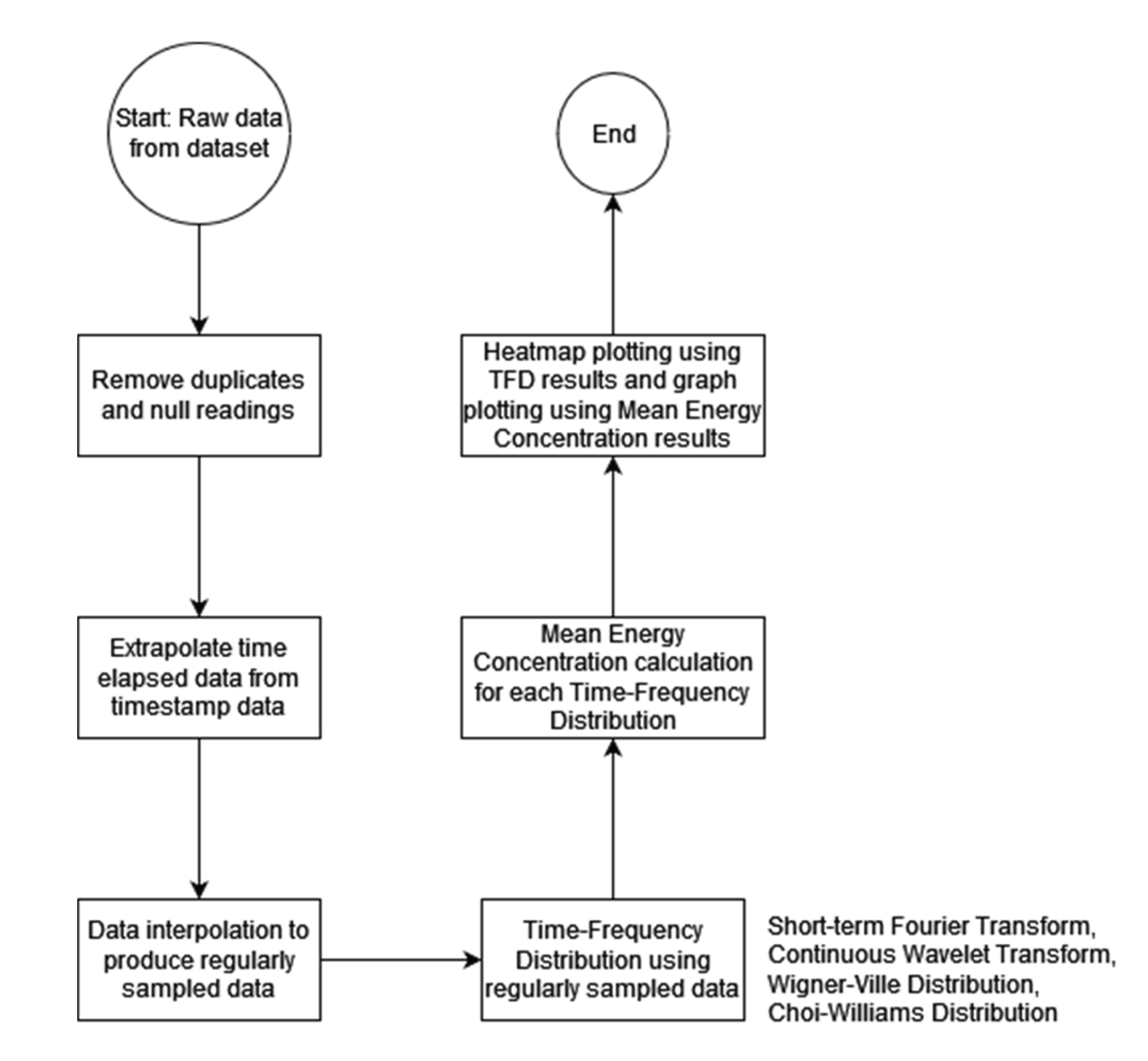

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Data Interpolation

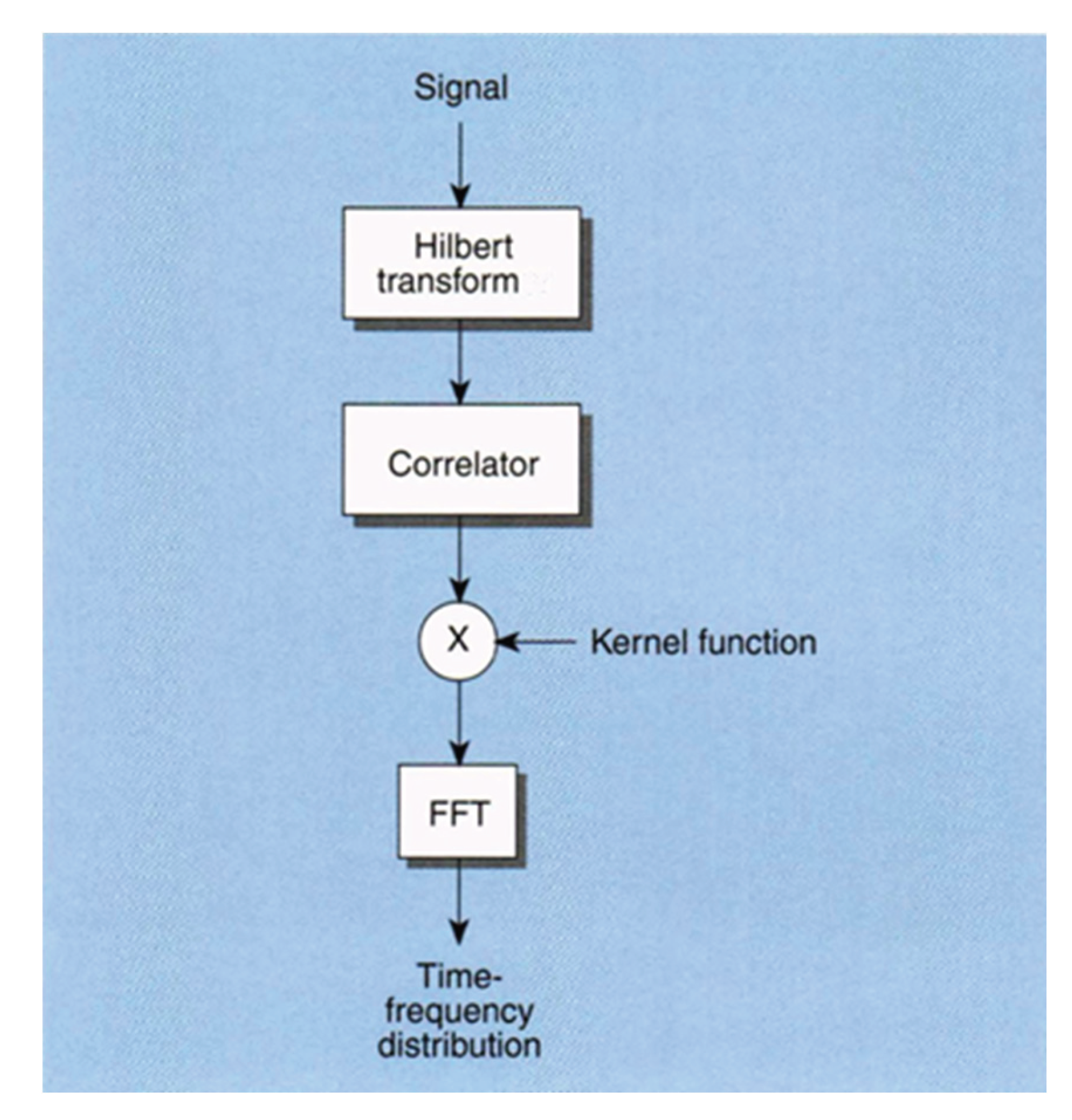

2.3. Time-Frequency Distributions (TFDs)

2.4. Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT)

2.5. Wigner-Ville Distribution (WVD)

2.6. Choi-Williams Distribution

2.7. Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT)

2.8. Mean Energy Concentration

2.9. Analysis Procedure

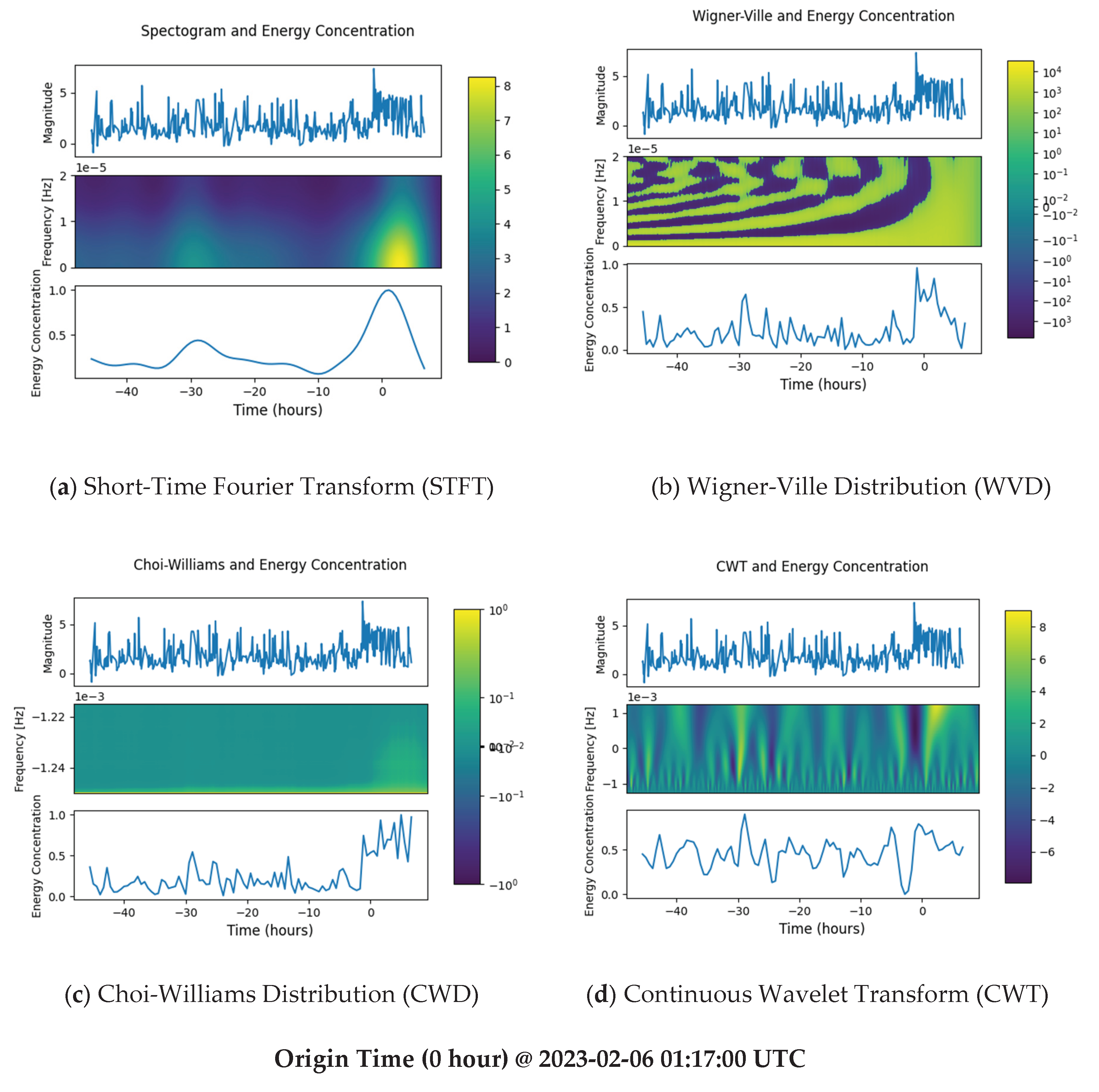

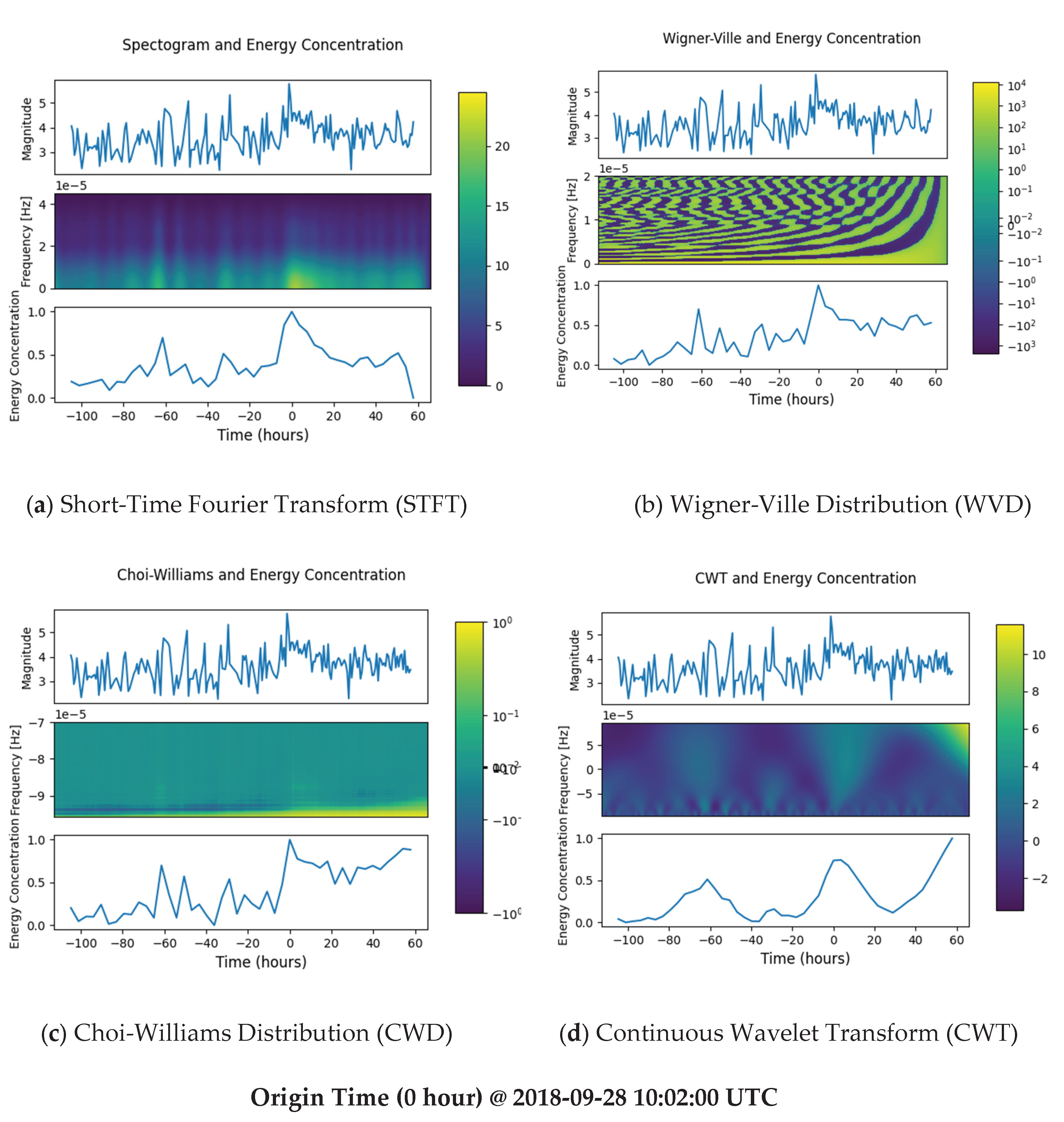

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Endpoint Effect

4.2. TFD Comparisons

4.3. Limitations and Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TFD | Time-Frequency Distribution |

| FM | Frequency Modulation |

| EEW | Earthquake Early Warning |

| MEM | Micro-electro-mechanical |

| WT | Wavelet Transform |

| FFT | Fast-Fourier Transform |

| STFT | Short-Time Fourier Transform |

| WVD | Wigner-Ville Distribution |

| CWD | Choi-Williams Distribution |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| UTC | Universal Time Coordinated |

References

- Zaccagnino, D.; Doglioni, C. The Impact of Faulting Complexity and Type on Earthquake Rupture Dynamics. Commun Earth Environ 2022, 3, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, T.C.; Kanamori, H. A Moment Magnitude Scale. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 1979, 84, 2348–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Lin, J.; Lu, Z. Time-Frequency Energy Distribution of Ground Motion and Its Effect on the Dynamic Response of Nonlinear Structures. Sustainability 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tang, J. On Vibration Suppression and Energy Dissipation Using Tuned Mass Particle Damper. J Vib Acoust 2017, 139, 11008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.F.; Nagarajaiah, S. State of the Art of Structural Control. Journal of Structural Engineering 2003, 129, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, S. T: Great Quake Debate, 2020.

- Can You Predict Earthquakes? Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/can-you-predict-earthquakes (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Earthquakes: Prediction, Forecasting and Mitigation Available online:. Available online: https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/earthquake-briefing (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Keilis-Borok, V. Earthquake Prediction: State-of-the-Art and Emerging Possibilities. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 2002, 30, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodera, Y.; Hayashimoto, N.; Moriwaki, K.; Noguchi, K.; Saito, J.; Akutagawa, J.; Adachi, S.; Morimoto, M.; Okamoto, K.; Honda, S.; et al. First-Year Performance of a Nationwide Earthquake Early Warning System Using a Wavefield-Based Ground-Motion Prediction Algorithm in Japan. Seismological Research Letters 2020, 91, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Wu, D.J.; Zhu, W.; Cai, M.; Ellsworth, W.L. DeepShake: Shaking Intensity Prediction Using Deep Spatiotemporal RNNs for Earthquake Early Warning. Seismological Research Letters 2022, 93, 1636–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Allen, R.M.; Schreier, L.; Kwon, Y.W. Earth Sciences: MyShake: A Smartphone Seismic Network for Earthquake Early Warning and Beyond. Sci Adv 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Jiang, P.; Ma, Q.; Su, J.; Cai, Y.; Zheng, Y. Chinese Nationwide Earthquake Early Warning System and Its Performance in the 2022 Lushan M6.1 Earthquake. Remote Sens (Basel) 2022, 14, 4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Yu, Y. ZHANG Heng’s Seismometer and Longxi Earthquake in AD 134. Acta Seismologica Sinica 2006, 19, 704–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, R.J. Earthquake Prediction: A Critical Review. Geophys J Int 1997, 131, 425–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M. On the Apparently Inappropriate Use of Multiple Hypothesis Testing in Earthquake Prediction Studies. Seismological Research Letters 2019, 90, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrowsmith, S.J.; Trugman, D.T.; MacCarthy, J.; Bergen, K.J.; Lumley, D.; Magnani, M.B. Big Data Seismology. Reviews of Geophysics 2022, 60, e2021RG000769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L, S.; N, A.; Prasanna, K.; Haneesh, A.N. FM Radio Wave Based Early Earthquake Detection. 2021 8th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom) 2021, 736–741. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, A. How Machine Learning Might Unlock Earthquake Prediction Available online:. Available online: https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/12/29/1084699/machine-learning-earthquake-prediction-ai-artificial-intelligence/ (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Mignan, A.; Broccardo, M. Neural Network Applications in Earthquake Prediction (1994–2019): Meta-Analytic and Statistical Insights on Their Limitations. Seismological Research Letters 2020, 91, 2330–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgmann, R. Reliable Earthquake Precursors? Science (1979) 2023, 381, 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bletery, Q.; Nocquet, J.-M. The Precursory Phase of Large Earthquakes. Science (1979) 2023, 381, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.L.; Coppersmith, K.J. New Empirical Relationships among Magnitude, Rupture Length, Rupture Width, Rupture Area, and Surface Displacement. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 1994, 84, 974–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, J.P. Richter Scale Available online:. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/science/Richter-scale (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Naddaf, M. Turkey–Syria Earthquake: What Scientists Know. Nature 2023, 614, 398–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BNPB: Kerugian Akibat Gempa Palu Capai Rp18,4 Triliun. CNN Indonesia 2018.

- Loft, P. 20 February 2023.

- Dal Zilio, L.; Ampuero, J.-P. Earthquake Doublet in Turkey and Syria. Commun Earth Environ 2023, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Impact of Kaikōura Quake Revealed. New Zealand Government 2017.

- Demiralp, S. The Economic Impact of the Turkish Earthquakes and Policy Options 2023.

- AFP Quake Could Cost US$17bil. Star 2024.

- Rundle, J.B.; Donnellan, A.; Fox, G.; Ludwig, L.G.; Crutchfield, J. Does the Catalog of California Earthquakes, With Aftershocks Included, Contain Information About Future Large Earthquakes? Earth and Space Science 2023, 10, e2022EA002521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, I.; Rundle, J.B.; Zhang, T. Nowcasting ETAS Earthquakes: Information Entropy of Earthquake Catalogs 2023.

- Rundle, J.B.; Giguere, A.; Turcotte, D.L.; Crutchfield, J.P.; Donnellan, A. Global Seismic Nowcasting With Shannon Information Entropy. Earth and Space Science 2019, 6, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, Z.; Yao, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, C.; Jia, K. Small Earthquakes Can Help Predict Large Earthquakes: A Machine Learning Perspective. Applied Sciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejdić, E.; Djurović, I.; Jiang, J. Time–Frequency Feature Representation Using Energy Concentration: An Overview of Recent Advances. Digit Signal Process 2009, 19, 153–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriu, S.; Romica, T. Time-Frequency Representations of Earthquake Motion Records. 2003, 11. 11.

- Huerta-Lopez, C.I.; Shin, Y.; Powers, E.J.; Roesset, J.M. Time-Frequency Analysis of Earthquake Records. In Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Auckland; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Upegui-Botero, F.M.; Huerta-López, C.I.; Caro-Cortes, J.A.; Mart\’\inez-Cruzado, J.A.; Suarez-Colche, L.E. Joint Time-Frequency Analysis of Seismic Records. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th world conference on earthquake engineering.

- Liu, W.; Cao, S.; Chen, Y. Seismic Time-Frequency Analysis via Empirical Wavelet Transform. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2016, 13, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Bonar, D.; Sacchi, M. Seismic Denoising by Time-Frequency Reassignment. CSEG Expanded Abstracts 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero-Moreno, C.; Escalante-Ramirez, B. Seismic Signal Detection with Time-Frequency Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Third International Symposium on Time-Frequency and Time-Scale Analysis (TFTS-96).

- Hussein, A.F.; Hashim, S.J.; Aziz, A.F.A.; Rokhani, F.Z.; Adnan, W.A.W. Performance Evaluation of Time-Frequency Distributions for ECG Signal Analysis. J Med Syst 2018, 42, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, A.F.; Hashim, S.J.; Rokhani, F.Z.; Wan Adnan, W.A. An Automated High-Accuracy Detection Scheme for Myocardial Ischemia Based on Multi-Lead Long-Interval ECG and Choi-Williams Time-Frequency Analysis Incorporating a Multi-Class SVM Classifier. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dincer, B. EarthQuake Turkey 06 Feb 2023 - Latest 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/brsdincer/earthquake-turkey-06-feb-2023-latest (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- BMKG Earthquakes in Indonesia 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/dsv/5415797 (accessed on 22 May 023). [CrossRef]

- PHIVOLCS Latest Earthquake Information Available online:. Available online: https://earthquake.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph/EQLatest-Monthly/2022/2022_July.html (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- GeoNet Quake Search Available online:. Available online: https://quakesearch.geonet.org.nz/csv?bbox=172.8479,-43.3012,177.7368,-39.0704&startdate=2016-11-01T0:00:00&enddate=2016-11-30T23:00:00 (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Earthquake Information Available online:. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/multi/quake/index.html?lang=en (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Cochran, W.T.; Cooley, J.W.; Favin, D.L.; Helms, H.D.; Kaenel, R.A.; Lang, W.W.; Maling, G.C.; Nelson, D.E.; Rader, C.M.; Welch, P.D. What Is the Fast Fourier Transform? Proceedings of the IEEE 1967, 55, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RP, C.S.C.C. Numerical Methods for Engineers 2002.

- Hlawatsch, F.; Auger, F. Time-Frequency Analysis; ISTE; Wiley, 2013; ISBN 9781118623831.

- Li, G.Z.; Ren, X.; Zhang, B.; Zong, G. Analysis of Time-Frequency Energy for Environmental Vibration Induced by Metro. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Advances in Experimental Structural Engineering, United States.

- Najmi, A.H. The Wigner Distribution: A Time-Frequency Analysis Tool. Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig 1994, 15, 298. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.R.; de Oliveira, L.F.; Nadal, J. Reducing Cross Terms Effects in the Choi–Williams Transform of Mioelectric Signals. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2013, 111, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L. Time-Frequency Analysis; Electrical engineering signal processing; Prentice Hall PTR, 1995; ISBN 9780135945322.

- Choi, H.-I.; Williams, W.J. Improved Time-Frequency Representation of Multicomponent Signals Using Exponential Kernels. IEEE Trans Acoust 1989, 37, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallat, S. A Wavelet Tour of Signal Processing, Third Edition: The Sparse Way; 3rd ed.; Academic Press, Inc.: USA, 2008; ISBN 0123743702. [Google Scholar]

- LV, C.; ZHAO, J.; WU, C.; GUO, T.; CHEN, H. Optimization of the End Effect of Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT). Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2017, 30, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keilis-Borok, V.; Ismail-Zadeh, A.; Kossobokov, V.; Shebalin, P. Non-Linear Dynamics of the Lithosphere and Intermediate-Term Earthquake Prediction. Tectonophysics 2001, 338, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonlinear Dynamics of the Lithosphere and Earthquake Prediction; Keilis-Borok, V. I., Soloviev, A.A., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003; ISBN 978-3-642-07806-4. [Google Scholar]

- Shafi, I.; Ahmad, J.; Shah, S.I.; Kashif, F.M. Techniques to Obtain Good Resolution and Concentrated Time-Frequency Distributions: A Review. EURASIP J Adv Signal Process 2009, 2009, 673539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, M. Why Is Earthquake Prediction Research Not Progressing Faster? Tectonophysics 2001, 338, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Lei, Y.; Liu, R.; Yang, Y.; Wei, T.; Gao, J. Sparse Time-Frequency Analysis of Seismic Data: Sparse Representation to Unrolled Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, D. “This Is Not a ‘What If’ Story”: Tokyo Braces for the Earthquake of a Century. The Guardian 2019.

- Are You Ready For “The Big One”? Lockforce 2022.

| Earthquake | Number of samples | Average Sampling Period (s) |

|---|---|---|

| Turkey-Syria | 9399 | 275.681 |

| Sulawesi | 2709 | 924.244 |

| Luzon | 1801 | 1485.441 |

| Kaikōura | 7767 | 332.316 |

| Noto | 554 | 4653.032 |

| Earthquake | Mean Energy Peak Timestamp (UTC) | Mean Energy Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Minor EQ 1 | 2023-02-04 21:32:44 | 44.04% (STFT), 54.59% (CWD), 64.93% (WVD) |

| Major EQ | 2023-02-06 03:32:44 (STFT), 2023-02-06 01:19:24 (CWD, WVD) |

100% (STFT), 74.69% (CWD), 96.05% (WVD) |

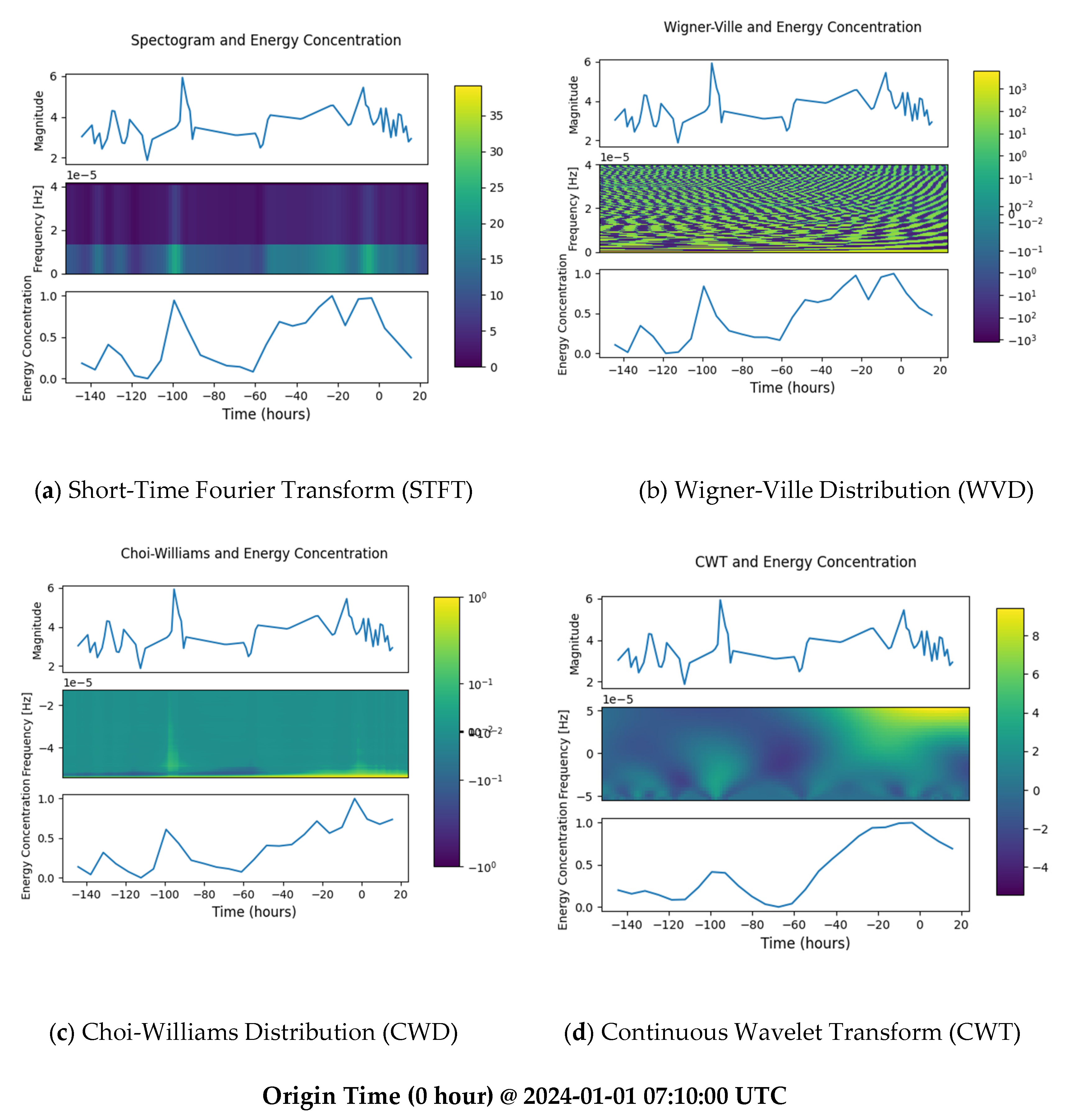

| Earthquake | Mean Energy Peak Timestamp (UTC) | Mean Energy Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Minor EQ 1 | 2018-09-25 23:08:33 | 69.75% (STFT), 69.91% (CWD), 70.07% (WVD), 51.23% (CWT) |

| Minor EQ 2 | 2018-09-27 04:01:53 (STFT), 2018-09-27 07:38:44 (CWD, WVD) |

51.22% (STFT), 53.85% (CWD), 51.06% (WVD) |

| Major EQ | 2023-02-06 12:31:53 | 100% (STFT, CWD, WVD) 73.63% (CWT) |

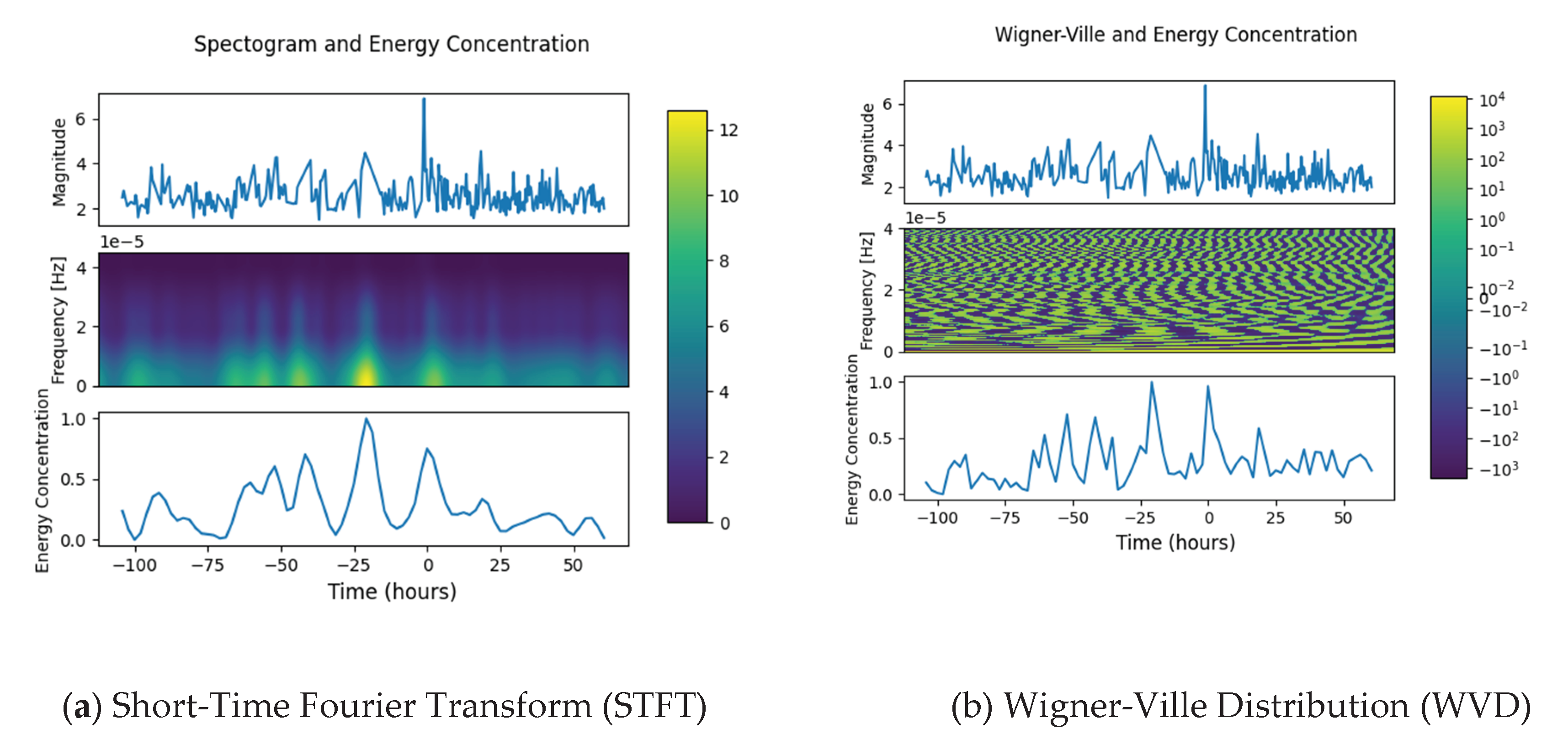

| Earthquake | Mean Energy Peak Timestamp (UTC) | Mean Energy Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Minor EQ 1 | 2022-07-25 04:37:00 | 60.51% (STFT), 66.94% (CWD), 71.01% (WVD), 72.44% (CWT) |

| Minor EQ 2 | 2022-07-25 15:02:00 | 70.30% (STFT), 58.35% (CWD), 68.48% (WVD), 68.08% (CWT) |

| Minor EQ 3 | 2022-07-26 11:52:00 | 100% (STFT, WVD, CWT), 87.63% (CWD) |

| Major EQ | 2022-07-27 08:42:00 | 75.04% (STFT), 100% (CWD), 96.16% (WVD), 75.45% (CWT) |

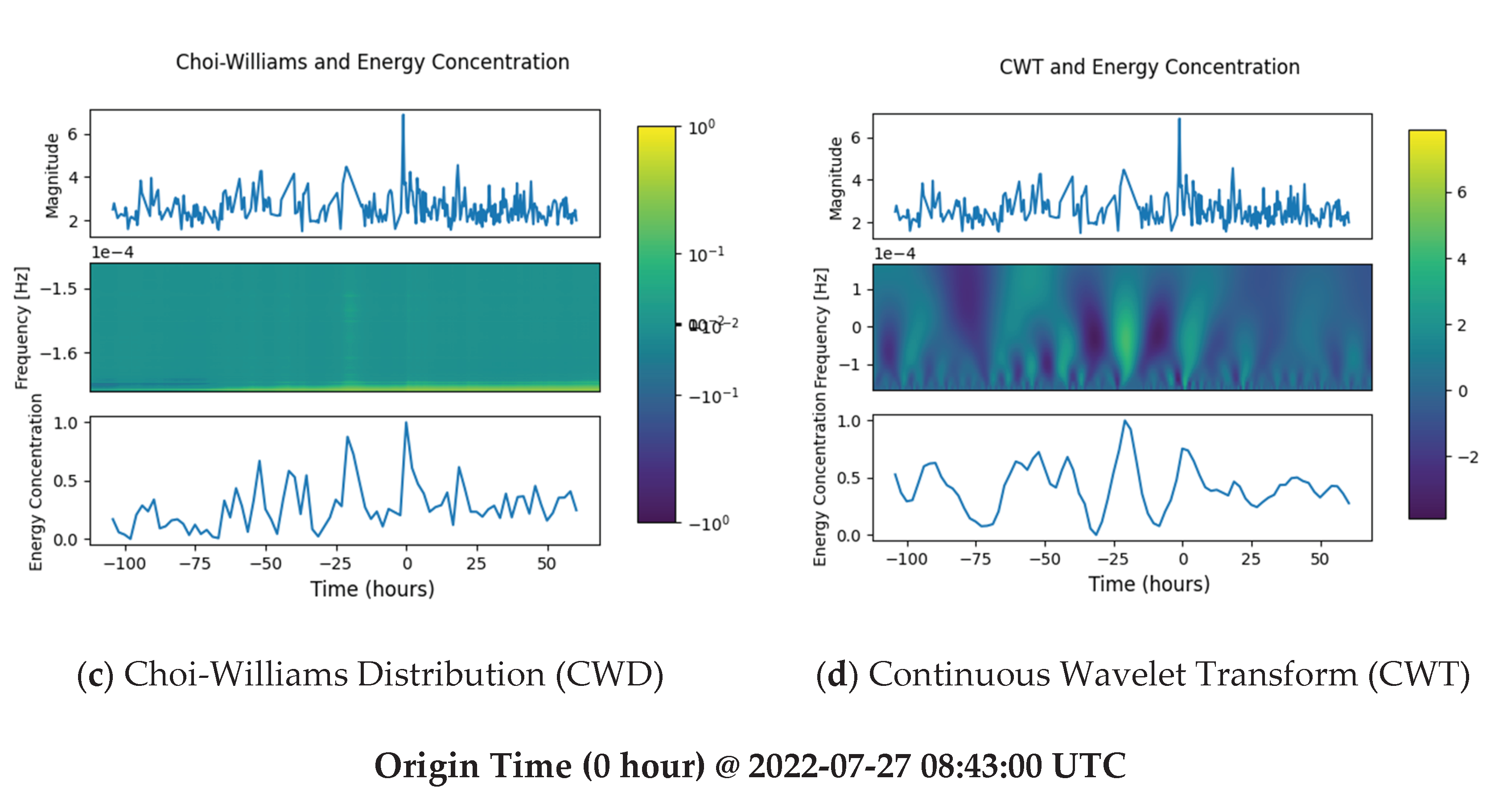

| Earthquake | Mean Energy Peak Timestamp (UTC) | Mean Energy Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Minor EQ 1 | 2016-11-10 18:47:35 (STFT) 2016-11-10 17:40:55 (CWD) 2016-11-10 18:14:15 (WVD) 2016-11-10 18:47:35 (CWT) |

41.63% (STFT), 34.02% (CWD), 36.07% (WVD), 93.29% (CWT) |

| Major EQ | 2016-11-13 11:47:35 (STFT) 2016-11-13 10:07:35 (CWD) 2016-11-13 10:40:55 (WVD) 2016-11-13 11:14:15 (CWT) |

100% |

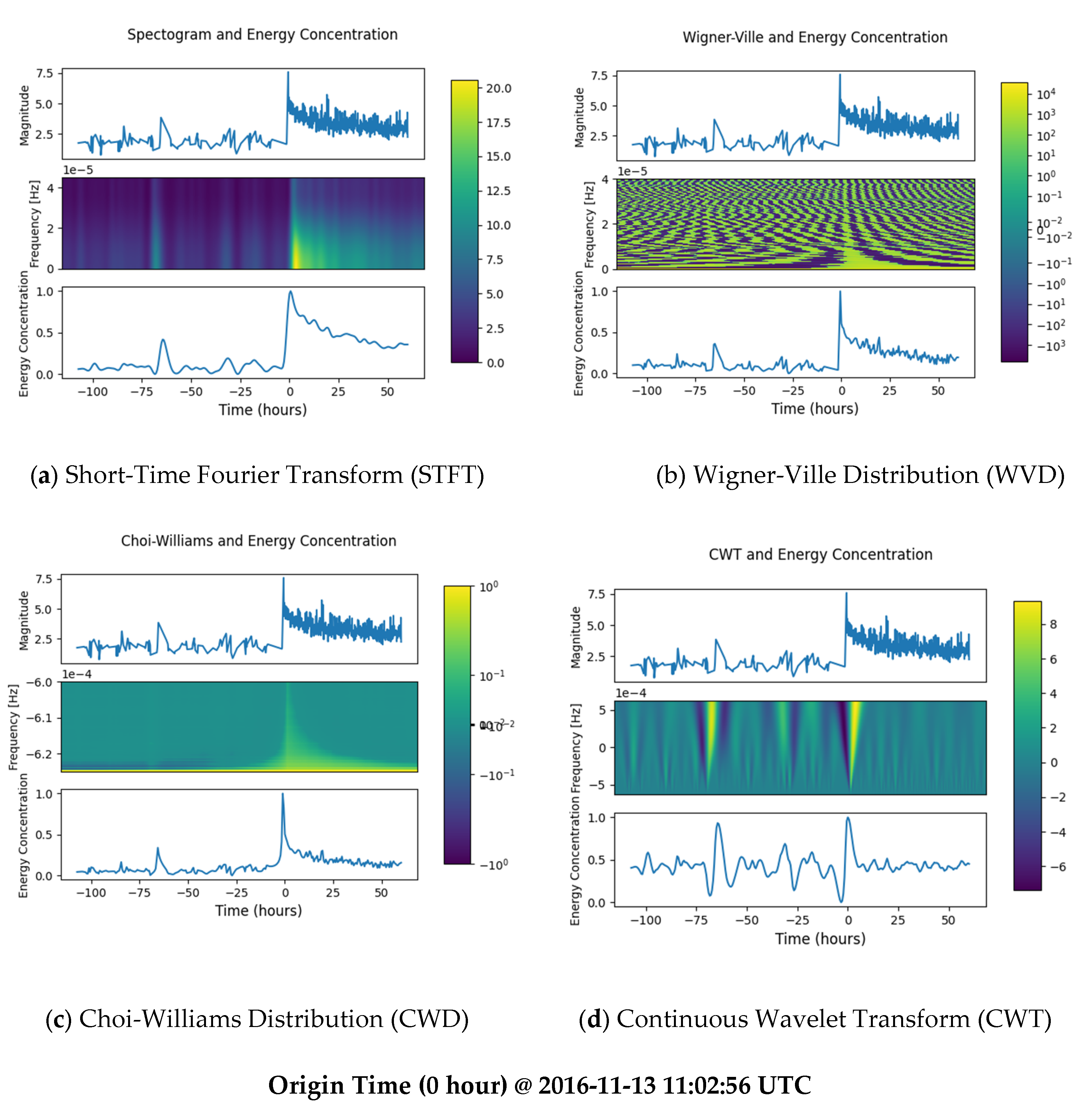

| Earthquake | Mean Energy Peak Timestamp (UTC) | Mean Energy Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Minor EQ 1 | 2023-12-28 03:48:20 | 94.53% (STFT), 61.00% (CWD), 84.12% (WVD), 41.56% (CWT) |

| Minor EQ 2 | 2023-12-30 06:55:00 | 68.67% (STFT), 40.78% (CWD), 67.02% (WVD) |

| Minor EQ 3 | 2023-12-31 08:28:20 | 100% (STFT), 71.58% (CWD), 97.76% (WVD), 93.89% (CWT) |

| Major EQ | 2024-01-01 03:38:20 | 97.35% (STFT), 100% (CWD, WVD, CWT) |

| Earthquake | Percentage between Mw 1.0 – 4.0 | Percentage Mw > 4.0 |

|---|---|---|

| Turkey-Syria | 58.94 | 8.715 |

| Sulawesi | 69.62 | 30.38 |

| Luzon | 97.08 | 2.96 |

| Kaikōura | 93.83 | 5.71 |

| Noto | 79.57 | 20.43 |

| Earthquake | No. of peaks | Estimate time between peaks |

|---|---|---|

| Turkey-Syria | 2 | 13 hours |

| Sulawesi | 3 | 30 hours |

| Luzon | 4 | 23 hours |

| Kaikōura | 2 | 60 hours |

| Noto | 4 | 20 hours |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).