Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

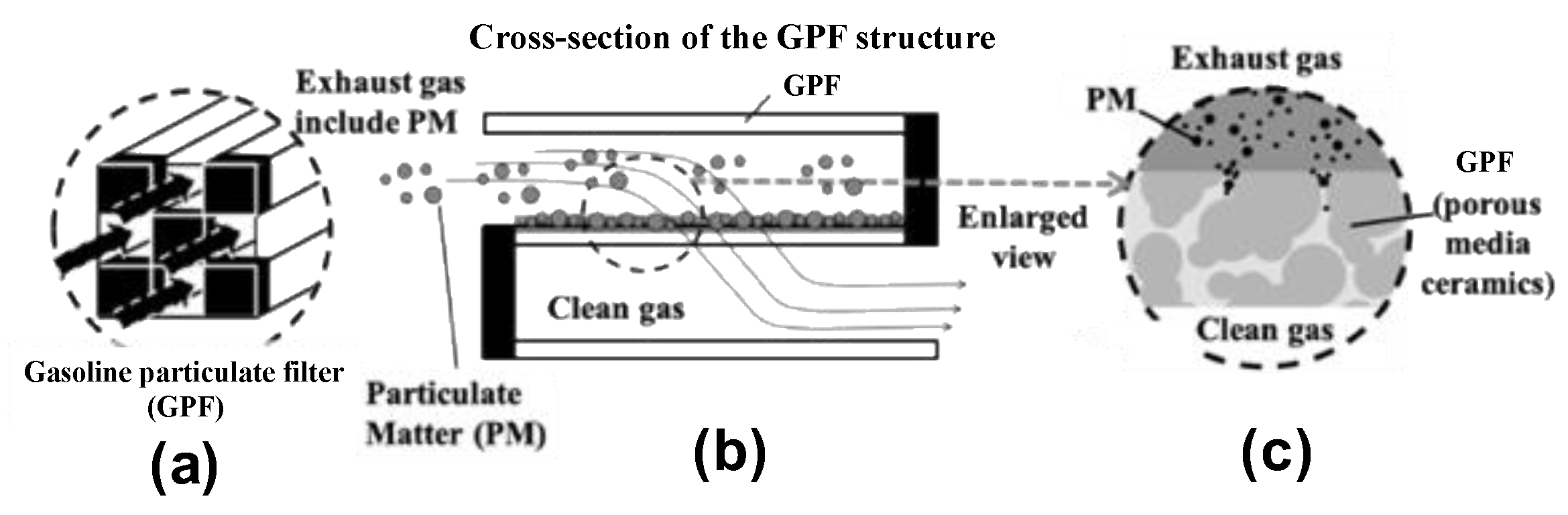

1. Introduction

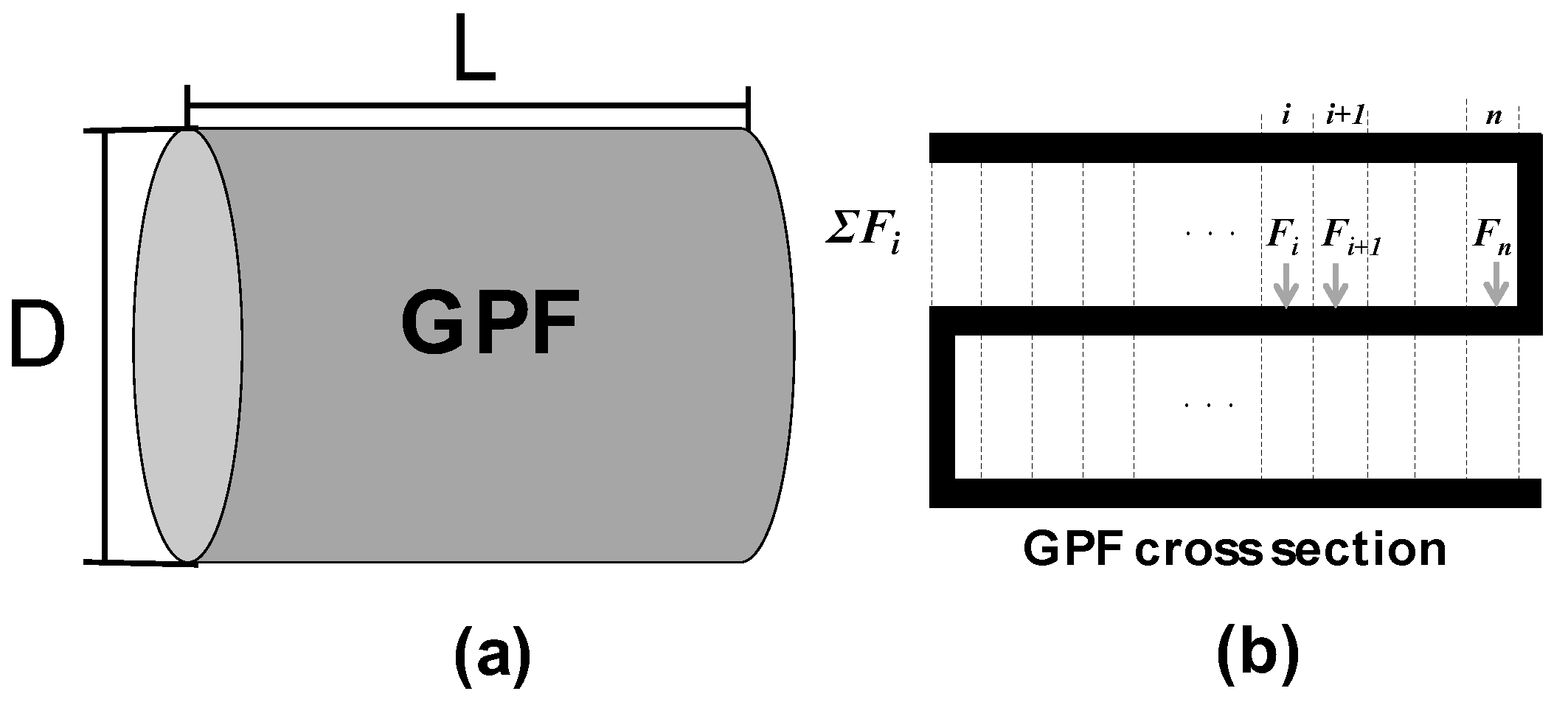

2. Calculation Model

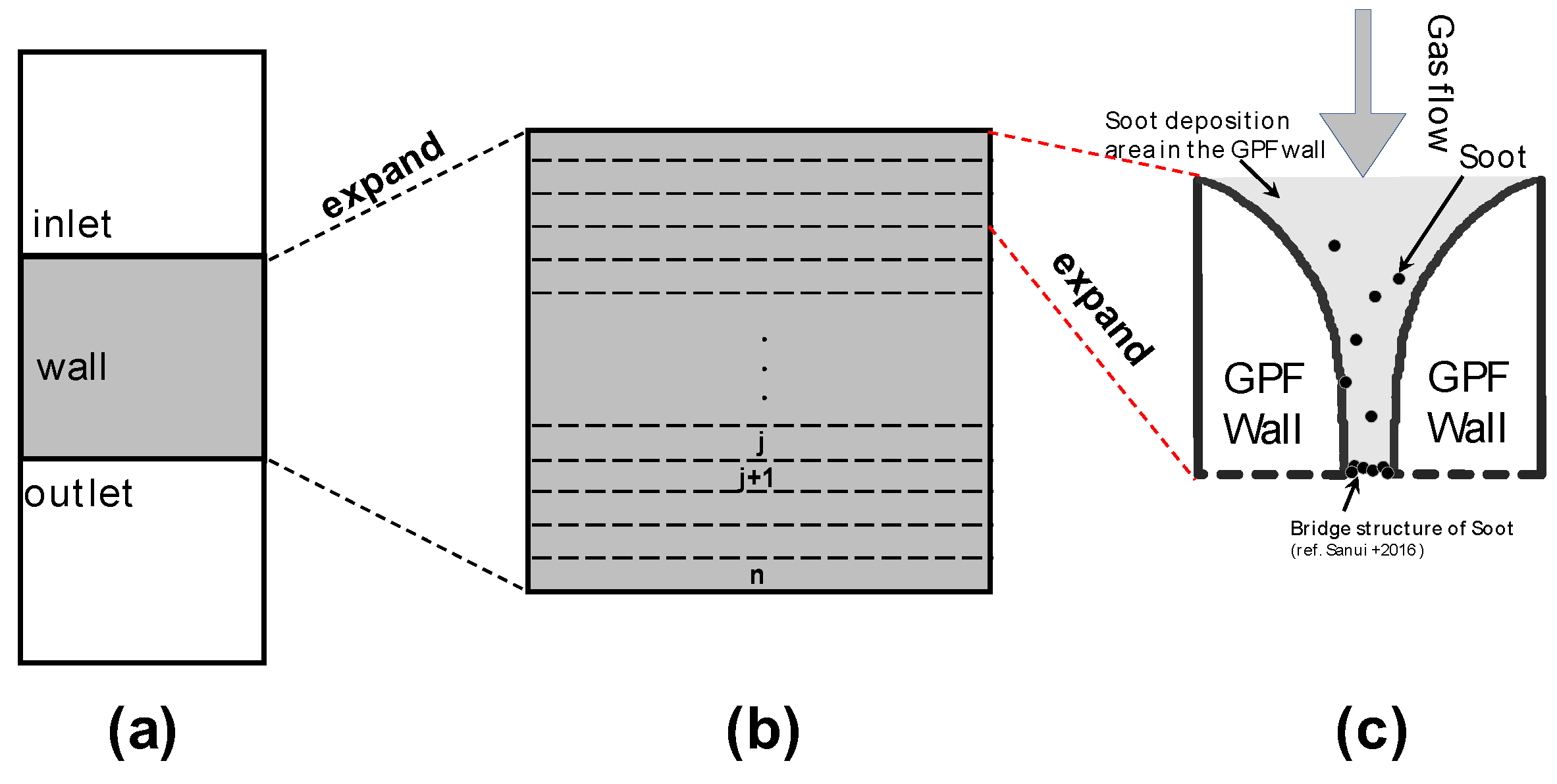

2.1. Exhaust Gas Flow in the Axial Direction (x-Direction) of the GPF

2.2. PM Deposition Within the GPF Wall

2.3. Treatment of Temperature

2.4. PM Oxidation

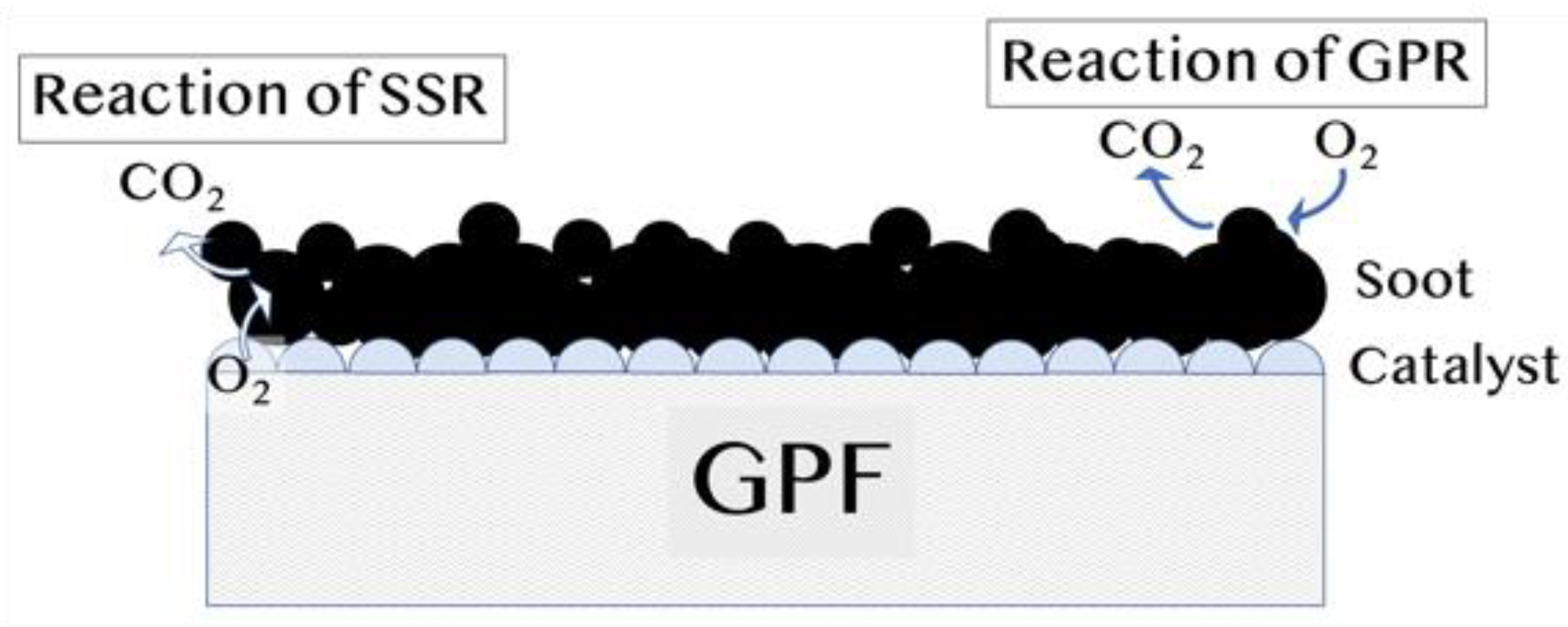

2.5. Catalytic Reaction and Gas-Phase O₂ Reaction

- Solid-state reaction (SSR), where PM reacts in contact with the catalyst

- Gas-phase reaction (GPR), where PM is not in contact with the catalyst, reacts with gaseous oxygen

| Frequency factor: A | Activation energy: E [kJ/mol] | |

| SSR | 6.2×107, 6.2×106 | 100, 120 |

| GPR | 2×109 | 195 |

3. Results

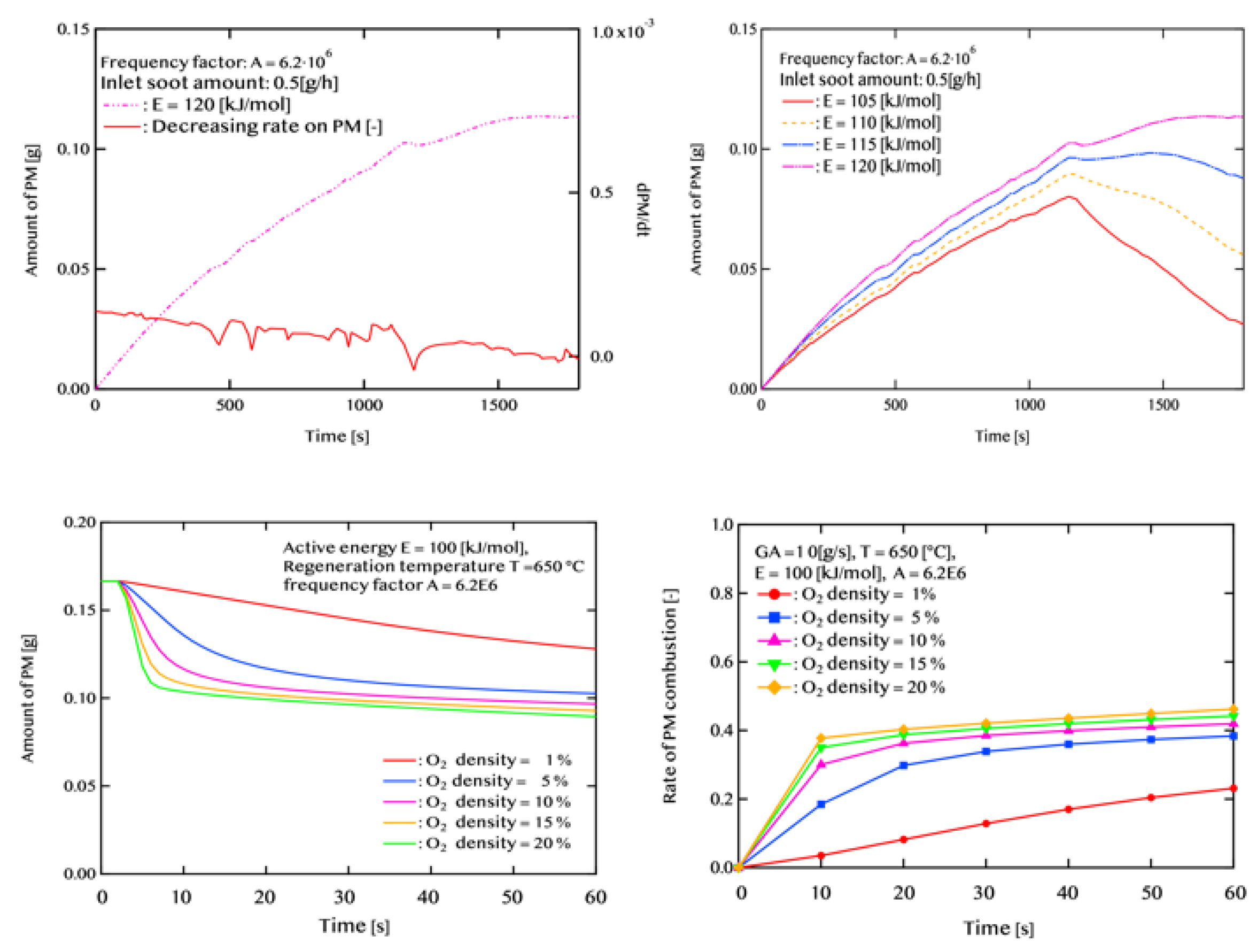

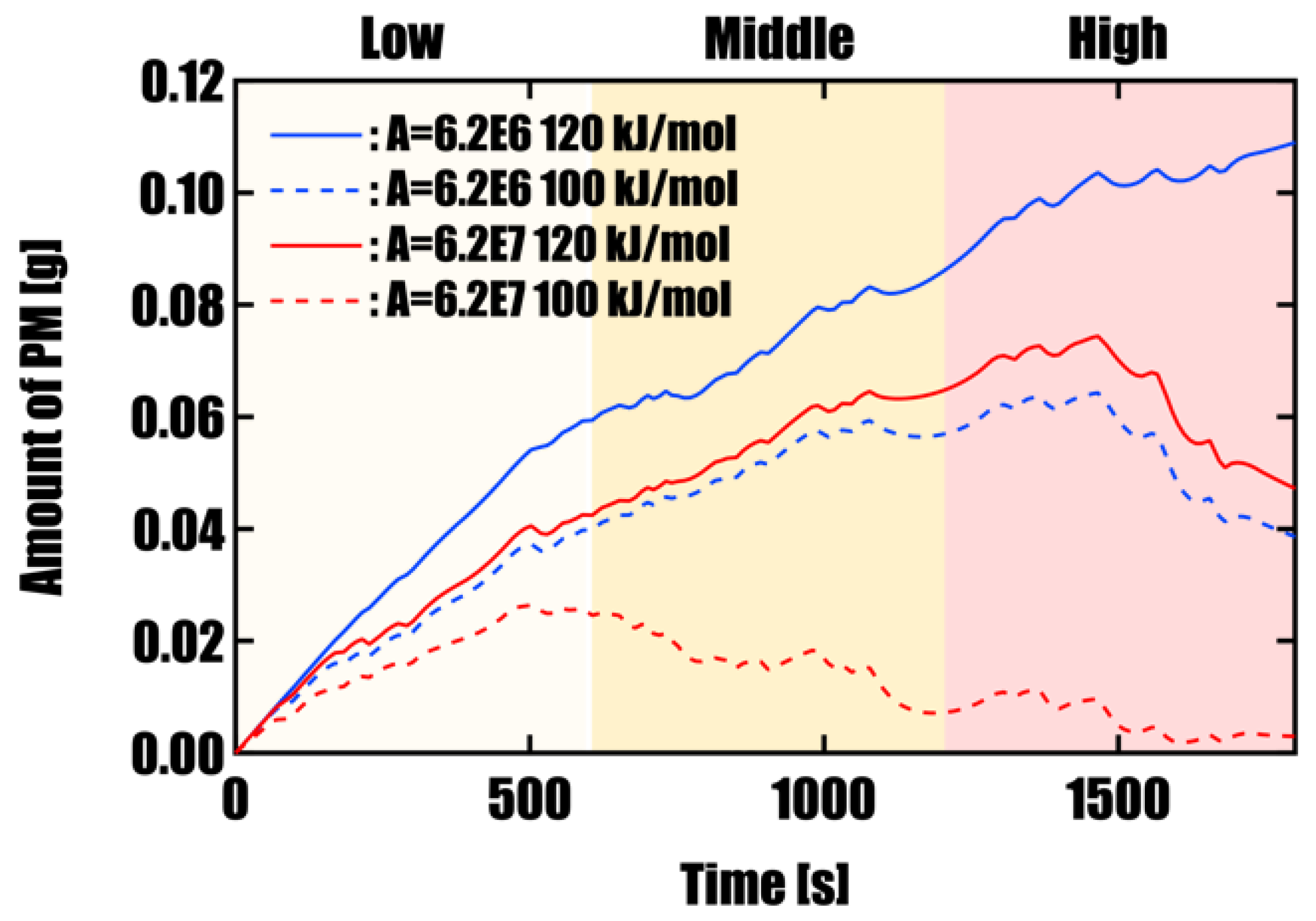

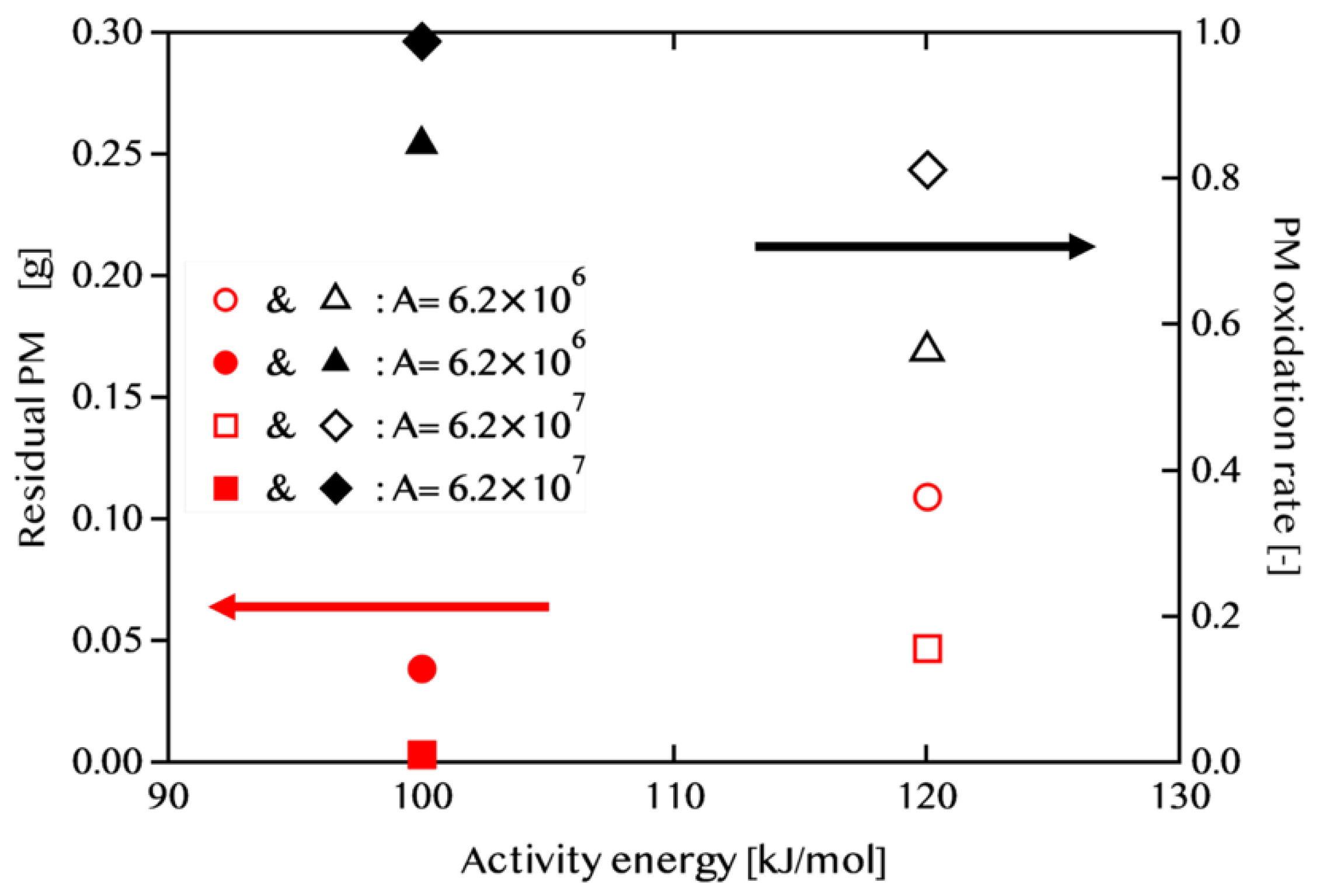

3.1. Effect of Activation Energy ΔE on PM Oxidation Performance

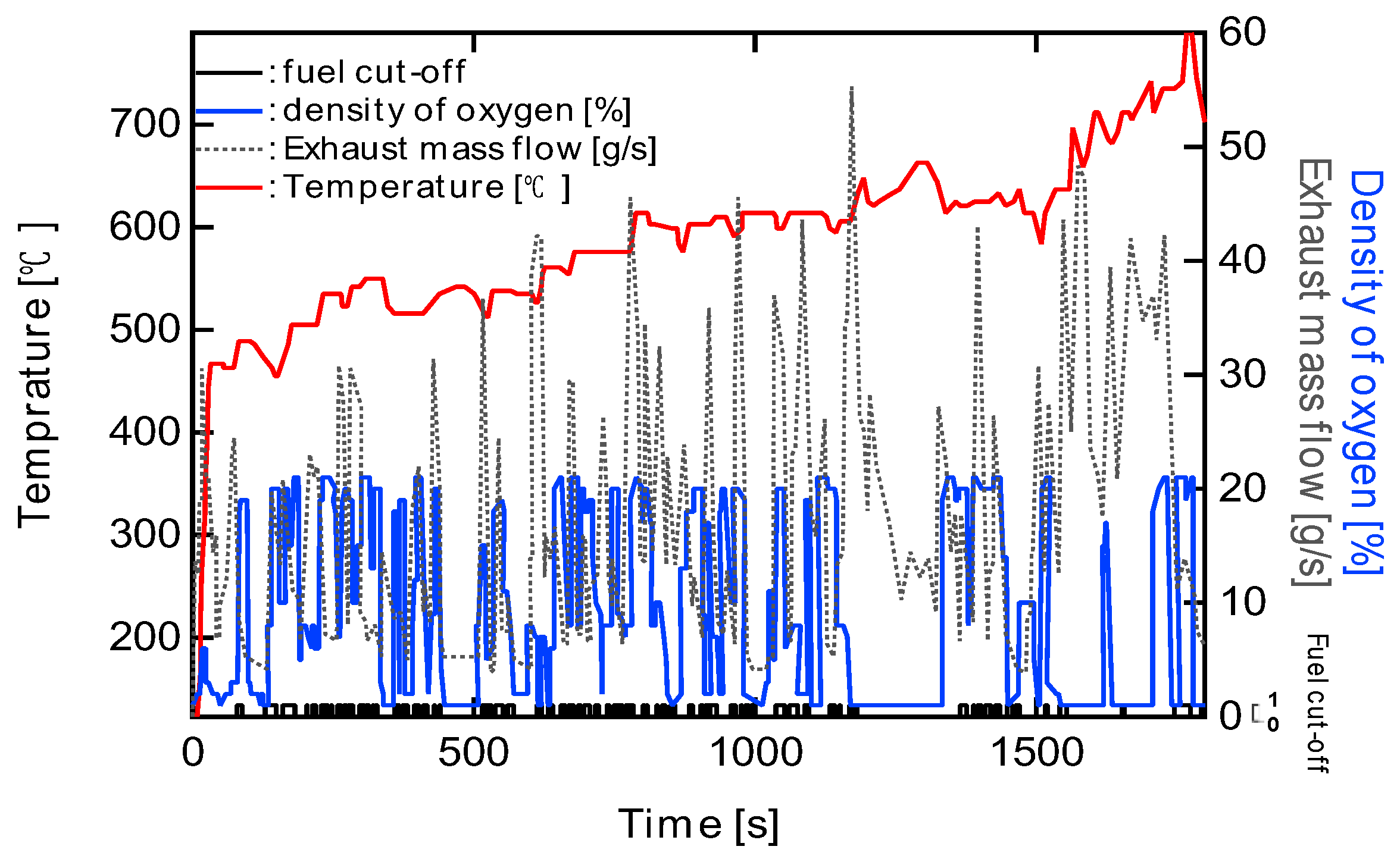

3.2. Effect of Forced Fuel Cut (FC) on PM Oxidation

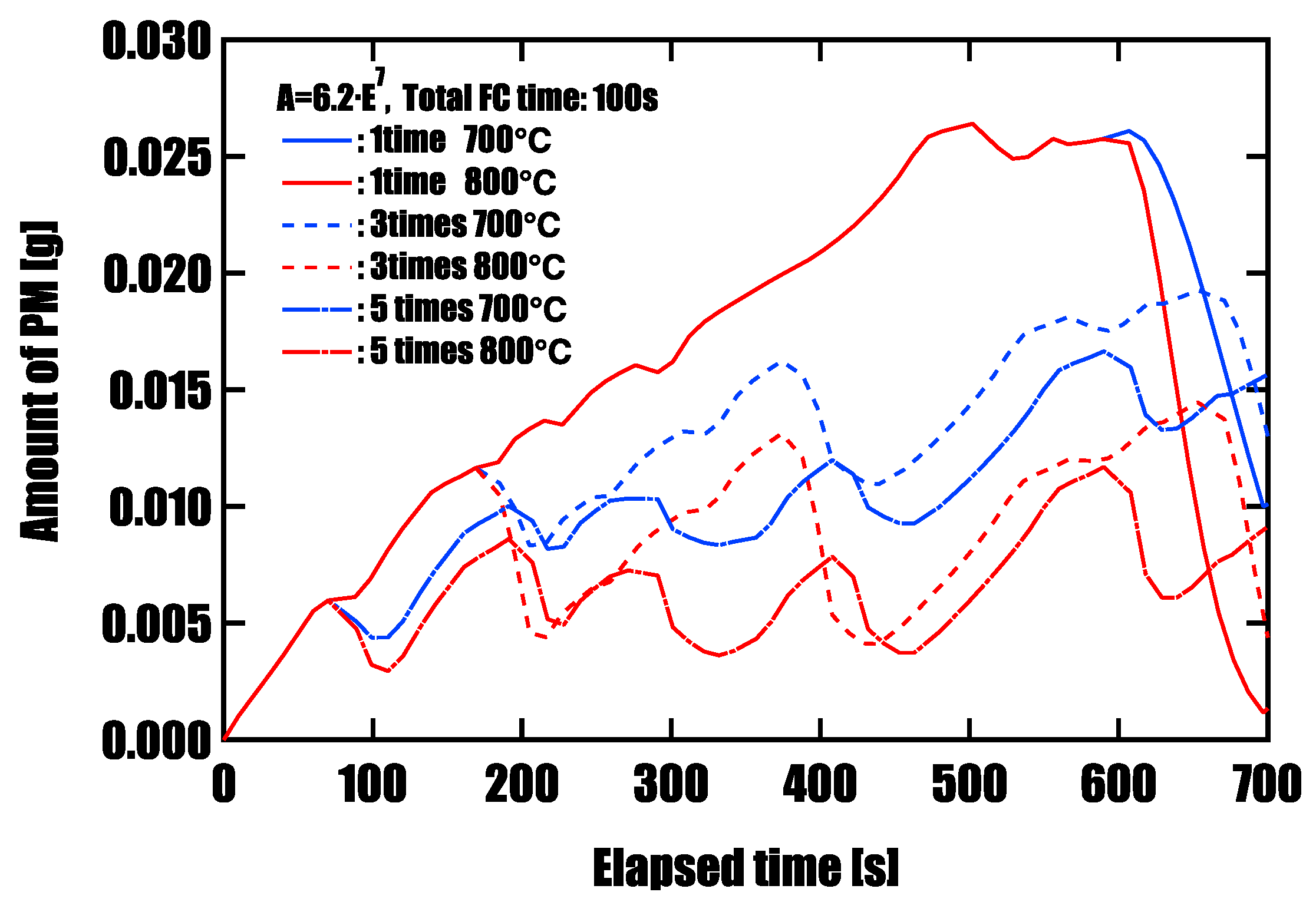

4. Conclusion

-

Effect of Catalyst Performance (Activation Energy and Pre-exponential Factor)Simulations under four different conditions, varying activation energy (E) and pre-exponential factor (A), revealed that PM oxidation performance highly depends on catalyst activity. Under high-activity conditions (E = 100 kJ/mol, A = 6.2 × 10⁷), an oxidation rate of 98.8% was achieved within a single WLTC cycle, and the final residual PM mass was as low as 0.003 g. In contrast, under conventional catalyst performance (E = 120 kJ/mol, A = 6.2 × 10⁶), oxidation was insufficient, with residual PM reaching 0.11 g, highlighting the limitations in regeneration under such conditions.

-

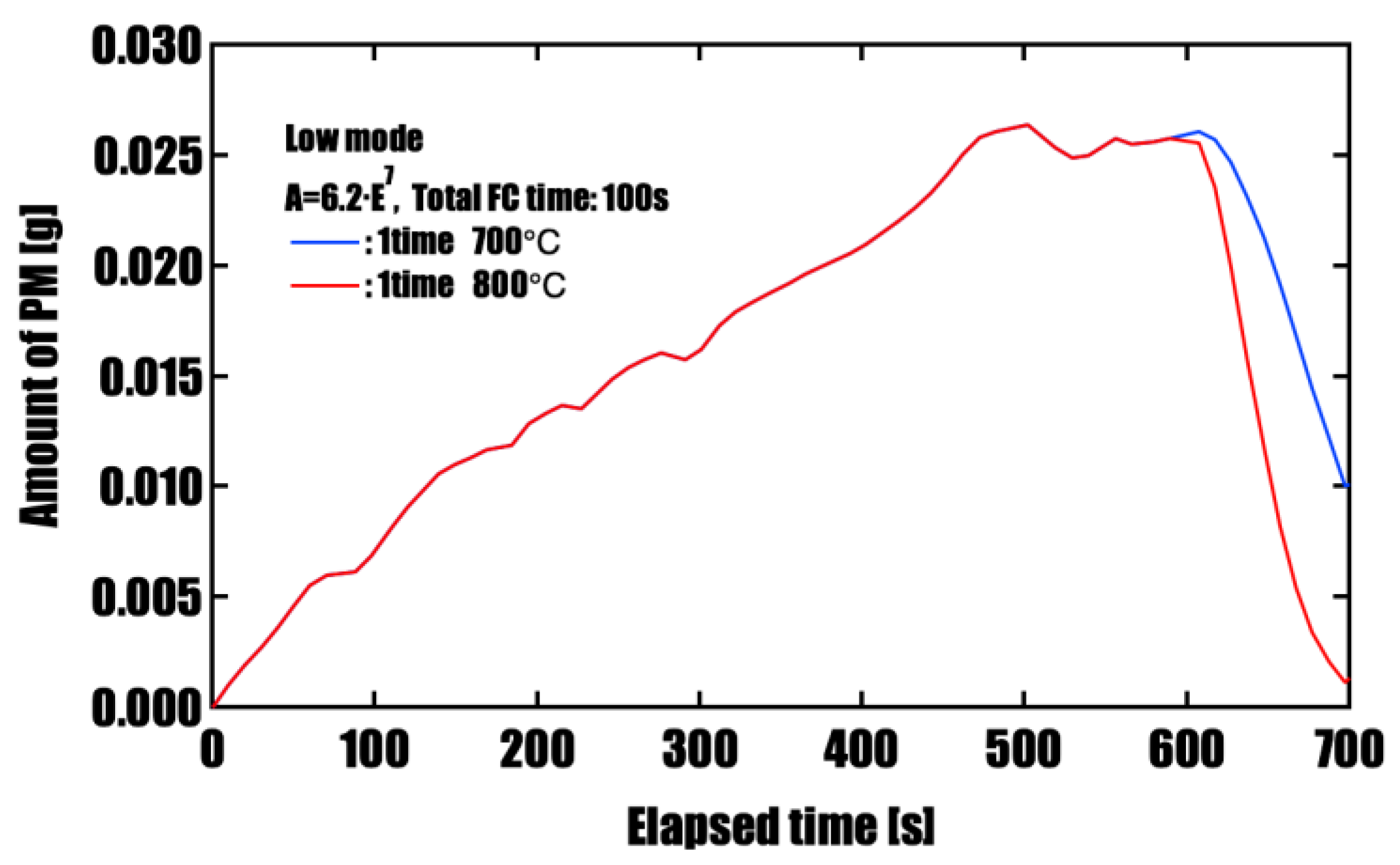

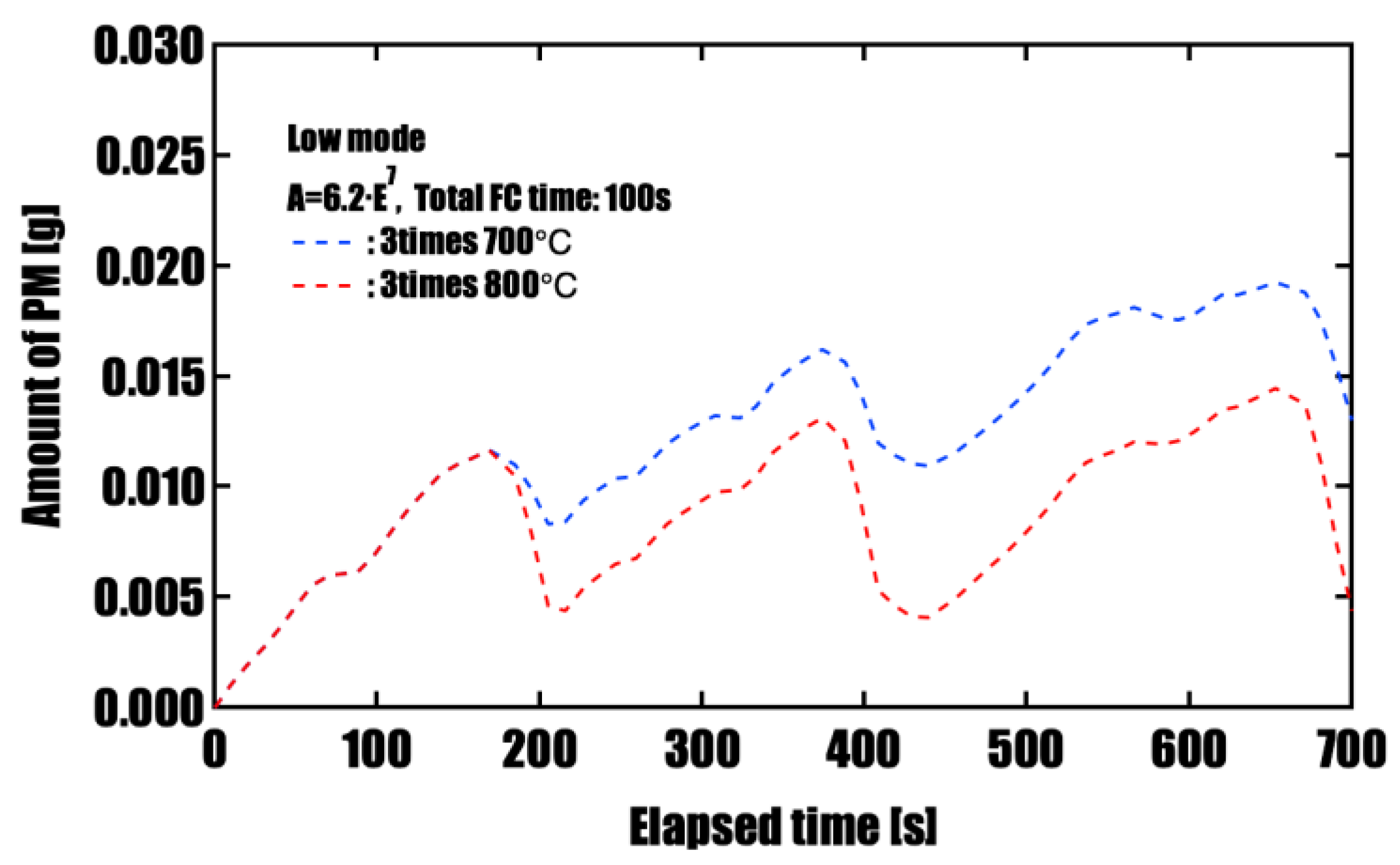

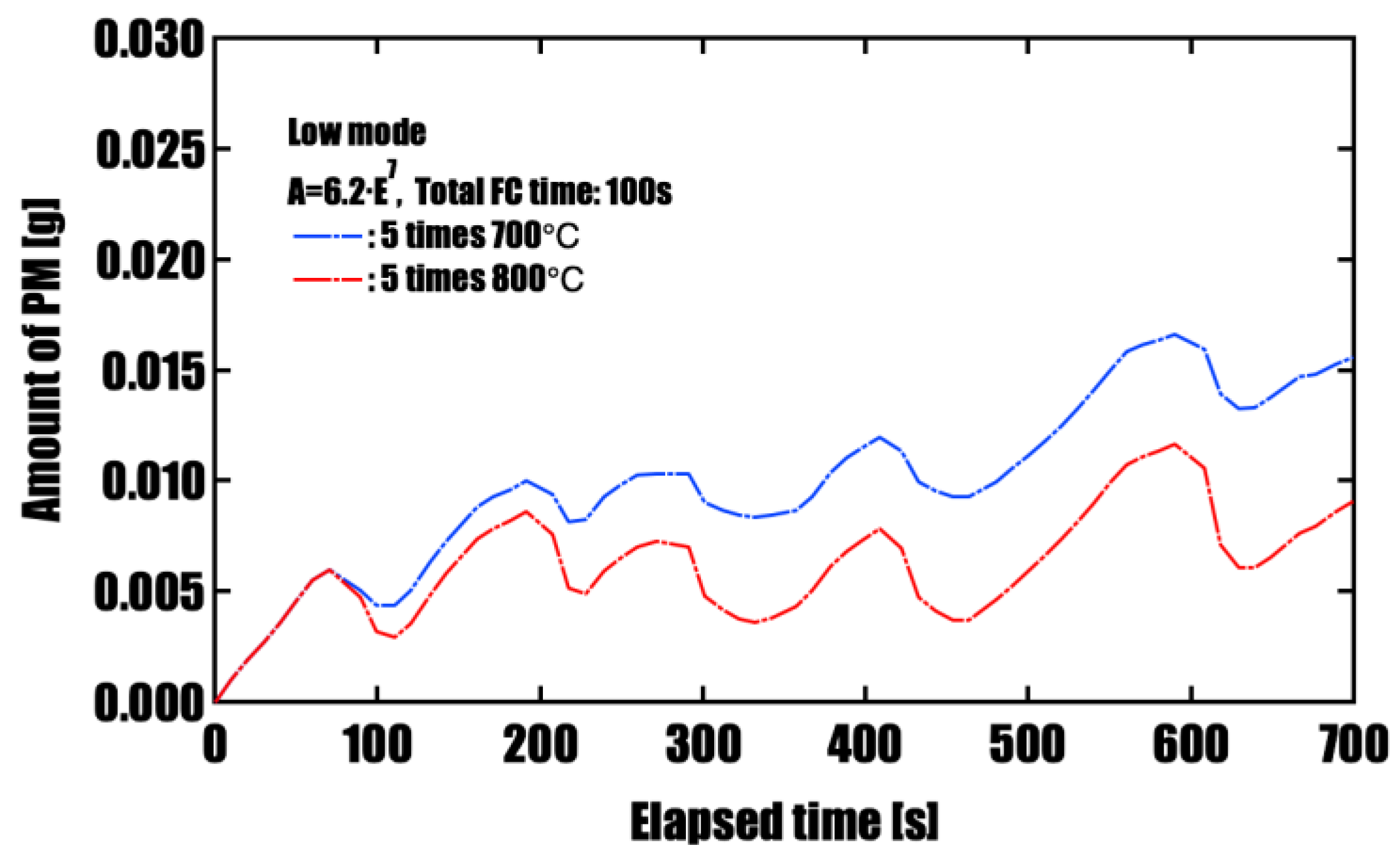

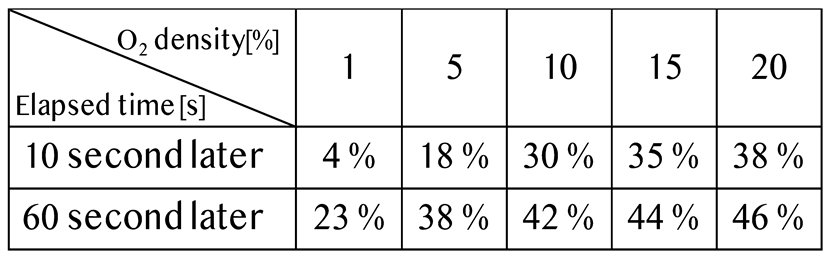

Effectiveness of Forced Fuel Cut (FC) IntroductionUnder conditions of limited catalyst performance, temporarily raising the exhaust oxygen concentration to 20% through forced fuel cut (FC) was shown to promote PM oxidation effectively. Especially in the low-speed mode, where exhaust temperatures remain around 500 °C, introducing a single continuous 100-second FC event yielded the highest oxidation effect, reducing PM by approximately 96%. This is attributed to the synergistic effects of sustained oxygen supply and heat release from oxidation reactions, which accelerated and maintained the reaction. On the other hand, when FC was divided into three or five intervals, the oxidation rate slightly decreased, but peak PM accumulation was effectively suppressed. This suggests that a split FC introduction may help reduce pressure drop and improve filter regeneration stability. Therefore, optimizing the FC strategy is crucial to meet multiple performance demands, such as regeneration efficiency and pressure loss reduction, and strategic control tailored to the operating conditions is required.

-

Future Issues and OutlookThe present model analyzed regeneration behavior separately for each speed phase. Future work must include continuous PM accumulation calculations, catalyst aging effects, and exhaust gas fluctuations to more accurately simulate real driving conditions. Moreover, for the practical implementation of forced FC, a comprehensive evaluation of control feasibility, user impact, and safety will be essential.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Definitions/Abbreviations

| Cg | Specific heat of exhaust gas [J/(kg·K)] |

| D | Diameter of GPF [m] |

| dc | Density of cordierite [kg/m³] |

| E | Activation energy [J/mol] |

| ΣF | Total flow rate [m³/s] |

| i | Cell number in x-direction [-] |

| j | Number in y-direction (wall thickness direction) within each cell i [-] |

| L | Total length of GPF [m] |

| N | Cell number counted from the inlet in x-direction [-] |

| PM | Amount of particulate matter (PM) [mol] |

| Q | Heat capacity [J/K] |

| R | Gas constant [J/(K·mol)] |

| Rpm | Amount of PM reaction [mol] |

| S | Flow amount of gas [kg] |

| T | Temperature used in PM combustion reaction rate equation [°C] |

| Tw | Wall temperature [°C] |

| TR | Corrected temperature [°C] |

| TPM | PM combustion heat temperature [°C] |

| ΔT | Temperature change [°C] |

| V | Volume of computational unit cell [m³] |

| vi | Flow velocity [m/s] |

| VO2 | O₂ concentration [mol/m³] |

| WT | Wall thickness of GPF [m] |

| α | Superficial velocity of each cell [m/s] |

| μ | Permeability of GPF wall [-] |

| σ | Cross-sectional area of each cell [m²] |

| φ | Porosity [-] |

| λ | Pipe friction coefficient [-] |

| ρ | Fluid density [kg/m³] |

| Lwp+PM | Length [m] |

| Dwalls | Diameter [m] |

References

- Zissis C. Samaras, Anastasios Kontses, Athanasios Dimaratos, Dimitrios Kontses, Andreas Balazs, Stefan Hausberger, Leonidas Ntziachristos, Jon Andersson, Norbert Ligterink, Paivi Aakko-Saksa, Panagiota Dilara, “A European Regulatory Perspective towards a Euro 7 Proposal”, SAE Technical Papers, 2022-37-0032,2022.

- Chris Morgan*, John Goodwin, “Impact of the Proposed Euro 7 Regulations on Exhaust Aftertreatment System Design”, Johnson Matthey Technol. Rev., 67, (2), 239–245, 2023. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Environmental Studies, Research Project Report No. 123 (in Japanese).

- T. W. Chan, M. Saffaripour, F. Liu, J. Hendren, K. A. Thomson, J. Kubsh, R. Brezny, and G. Rideout, “Characterization of Real-Time Particle Emissions from a Gasoline Direct Injection Vehicle Equipped with a Catalyzed Gasoline Particulate Filter During Filter Regeneration,” Emission Control Science and Technology, 2, pp. 75–88, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. H. Bock, M. M. Baum, J. A. Moss, A. E. Castonguay, S. Jocic, and W. F. Northrop, “Dicarboxylic Acid Emissions from a GDI Engine Equipped with a Catalytic Gasoline Particulate Filter,” Fuel, 275, 117940, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Akihama, “Particulate Matter (PM): Automobile Exhaust Gas Regulations and the Need for Modeling of Generation—Gasoline Direct Injection Engine/Vehicle,” Journal of the Combustion Society of Japan, 59(187), pp. 49–54, 2017 (in Japanese).

- J. Jang, J. Lee, Y. Choi, and S. Park, “Reduction of Particle Emissions from Gasoline Vehicles with Direct Fuel Injection Systems Using a Gasoline Particulate Filter,” Science of the Total Environment, 644, pp. 1418–1428, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Arunachalam, G. Pozzato, M. A. Hoffman, and S. Onori, “Modeling the Thermal and Soot Oxidation Dynamics Inside a Ceria-Coated Gasoline Particulate Filter,” Control Engineering Practice, 94, 104199, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, F. Yan, N. Fang, D. Yan, G. Zhang, Y. Wang, and W. Yang, “An Experimental Investigation of the Impact of Washcoat Composition on Gasoline Particulate Filter (GPF) Performance,” Energies, 13, 693, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Reinharter, “Investigation of Gasoline Particulate Filters (GPF) System Requirements and Their Integration in Future Passenger Car Series Applications,” Master’s Thesis, 2015.

- M. Nakamura, K. Yokota, and M. Ozawa, “Numerical Simulation of PM Deposition and Oxidation Using a One-Dimensional Model: A Study Considering Driving Modes,” Transactions of the Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan, 53(2), pp. 360–365, 2022.

- M. Nakamura, K. Yokota, and M. Ozawa, “One-Dimensional Simulation of PM Deposition and Regeneration Considering Driving Modes (Part 2),” Proceedings of the 2021 JSAE Spring Congress (in Japanese).

- M. Nakamura, K. Yokota, and M. Ozawa, “PM Deposition and Oxidation in Catalyzed Diesel Particulate Filters,” Transactions of the Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan, 51(2), 2020 (in Japanese).

- M. Nakamura, K. Yokota, M. Hattori, and M. Ozawa, “PM Deposition and Oxidation in Catalyzed Diesel Particulate Filters—Thermal Analysis in GPF (Part 2),” Transactions of the Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan, 51(2), 2019 (in Japanese).

- K. Yokota, M. Nakamura, M. Hattori, and M. Ozawa, “One-Dimensional Simulation of PM Deposition and Oxidation in Catalyzed Diesel Particulate Filters—Effect of GPF Geometry (Part 3),” Transactions of the Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan, 51(5-2), 2020 (in Japanese).

- M. Nakamura, K. Yokota, and M. Ozawa, “One-Dimensional Simulation of PM Deposition and Oxidation in Catalyzed Diesel Particulate Filters—Analysis of PM Combustion Behavior with Catalysts (Part 4),” Transactions of the Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan, 52(2), pp. 257–262, 2021 (in Japanese).

- M. Nakamura and M. Ozawa, “Effect of Surface Cavity Shape on PM Deposition and Pressure Drop in DPF Porous Material,” Journal of the Society of Materials Science, Japan, 76, pp. 562–567, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Nakamura, K. Yokota, M. Hattori, and M. Ozawa, “Numerical Calculation of PM Trapping and Oxidation of Diesel Particulate Filter with Catalyst,” SAE Technical Paper, 2020-01-2169, 2020.

- M. Nakamura, K. Yokota, K. Okai, and M. Ozawa, “Development of Converter Model for Catalysts in Particulate Filters,” Transactions of the Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan, 54(2-1), 2023 (in Japanese).

- M. Nakamura, K. Yokota, and M. Ozawa, “One-Dimensional Simulation of PM Deposition and Regeneration in Particulate Filters—Evaluation of Catalyst Loading Position,” Transactions of the Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan, 53(5-2), 2022 (in Japanese).

- Maki Nakamura, Koji Yokota, Masakuni Ozawa, “Numerical calculation optimization for particulate matter (PM) trapping and oxidation of catalytic diesel particulate filter (DPF)”, Applied Sciences, 15(5), 2356, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Sanui and K. Hanamura, “Electron Microscopic Time-Lapse Visualization of Surface Cavity Filtration in the Particulate Matter Trapping Process,” Journal of Microscopy, 263(3), pp. 250–259, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Maki Nakamura and Masakuni Ozawa, “Phenomena of PM deposition and oxidation in the diesel particulate filter”, SAE2019-01-2288, 2019.

- M. Yu, D. Luss, and V. Balakotaiah, “Analysis of Flow Distribution and Heat Transfer in a Diesel Particulate Filter,” Chemical Engineering Journal, 226, pp. 68–78, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Huang, Y. Liu, Z. Meng, Y. Peng, H. Li, Z. Zhang, Q. Zhang, Z. Qin, J. Mao, and J. Fang, “Effect of Different Aging Conditions on the Soot Oxidation by Thermogravimetric Analysis,” ACS Omega, 5, pp. 30568–30576, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Liang, X. Lv, Y. Wang, L. He, Y. Wang, K. Fu, Q. Liu, and K. Wang, “Experimental Investigation of Diesel Soot Oxidation Reactivity Along the Exhaust After-Treatment System Components,” Fuel, 302, 121047, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Hu, Z. Lu, H. Zhang, B. Song, and Y. Quan, “Effect of Oxidation Temperature on Oxidation Reactivity and Nanostructure of Particulate Matter from a China VI GDI Vehicle,” Atmospheric Environment, 256, 2021. [CrossRef]

|

| Number of FC installations | Temperature [℃] | Maximum deposited volume [g] | Final residual volume [g] |

| 1 time (100 s) | 700 | 0.026 | 0.010 |

| 1 time (100 s) | 800 | 0.026 | 0.001 |

| 3 times (30+30+40 s) | 700 | 0.019 | 0.013 |

| 3 times (30+30+40 s) | 800 | 0.019 | 0.004 |

| 5 times (20 s × 5) | 700 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

| 5 times (20 s × 5) | 800 | 0.016 | 0.009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).