1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent. In 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 10.8 million people developed TB and 1.25 million died from the disease, including 161,000 deaths among people living with HIV. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) further complicates this picture, posing a critical threat to global health security and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) control. Despite available tools, progress towards the End TB strategy targets is stalling, underscoring the WHO emphasis on robust laboratory networks for TB detection including MDR/TB, treatment monitoring, and policy guidance (1) .

National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratories (NTRLs) form the cornerstone of the national TB response by serving as the highest authority for testing algorithms and quality assurance. Their mandate also includes performing specialized diagnostics like drug susceptibility testing, conducting research, evaluating new tools, and overseeing laboratory workforce development.

Without well-resourced National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratories, surveillance systems for TB cannot provide the reliable data required for effective national planning or meaningful contributions to global monitoring (2). The value of such laboratories is demonstrated by the WHO’s supranational reference laboratory (SRL) network for TB, which strengthens surveillance through proficiency testing, method harmonization, and rapid drug resistance detection. In Europe, NTRLs are essential for providing timely, standardized data on drug resistance, which directly guides the public health response (3,4). NTRLs supervise external quality assessment (EQA) and facilitate the ongoing evolution of national TB diagnostic algorithms. Over the years, they have played a major role in promoting the adoption of novel technologies, such as Line Probe Assays (LPA), molecular WHO-recommended diagnostics (GeneXpert, TrueNat etc), and targeted genomic sequencing. NTRLs act as both policy anchors and technical leaders. By ensuring diagnostic accuracy within national reporting systems, NTRLs support the larger surveillance system to monitor changes in TB epidemiology and better understand the efficacy and impact of disease control interventions (2–4).

These functions are particularly critical in sub-Saharan Africa, where health systems contend with challenges such as underfunding, limited laboratory infrastructure, and a historical reliance on external facilities for advanced testing. The absence of local capacity for Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture drug susceptibility testing (DST), and advanced technologies such as sequencing platforms has historically delayed diagnosis and compromised patient management (5,6).

Targeted investments in NTRLs have yielded measurable gains in TB disease control across diverse settings. In India, scaling up rapid molecular diagnostics at reference laboratories significantly improved the detection of rifampicin resistance, directly informing national treatment policies (7) . Similarly, a WHO-supported collaboration with a supranational reference laboratory in Uganda strengthened proficiency-testing, leading to substantial improvement in DST reliability (8). In Portugal, adoption of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) at the NTRL shortened resistance profiling turnaround times and enhanced outbreak investigations (9). In Benin, the SRL in Cotonou has reinforced quality assurance across national and regional TB networks, supporting EQA and acting as a training hub for Central and West Africa (10). Collectively, these examples demonstrate that strategic investments in laboratory systems strengthening, NTRLs, and SRLs lead to meaningful improvements in TB disease control and patient outcomes.

Therefore, the main aim of this study was to conduct an operational research and program evaluation to assess the progress of TB diagnostic capacity and laboratory network performance in the republic of Congo between 2018 and 2024. As key indicators of progress we specifically focused on diagnostic coverage, drug-resistant TB detection, specimen referral, HIV integration, quality assurance, and regional research collaboration.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

An operational research and program evaluation was in the republic of Congo between 2018 and 2024.

The study documented and analyzed the outcomes of a nationwide Tuberculosis laboratory system strengthening intervention over an eight-year period, comparing key indicators before and after the establishment of the National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory.

2.2. Setting:

The study was conducted in the Republic of Congo (which has a population of around 6.1 million). In scope, the intervention was national involving the entire network of public health facilities providing TB diagnostics.

2.3. Data Source:

The programmatic data source included the routine, aggregated data from the National Tuberculosis Program (NTP) were the primary sources. Particularly

- ✓

Annual reports on TB case notifications (bacteriologically confirmed, drug-resistant).

- ✓

Laboratory service data: test volumes

- ✓

Records of the diagnostic network (number of sites).

- ✓

Frequency and volume of facility involved in referral TB sample

Together with the Global Fund and other partners (WHO, UNDP, Red Cross) documentation, provided on project implementation, procurement, and technical assistance.

2.4. Quality Management System Records

Data from the External Quality Assessment (EQA) programs and the WHO SLIPTA audit report were also used to measure improvements in laboratory quality.

2.5. Laboratory Strengthening Intervention

With technical and financial support from the Global fund, WHO, UNDP and the Red Cross, the NTRL was established and operationalized to enhance the national diagnostic capabilities. Key interventions included:

- ✓

Infrastructure development with construction, equipping and biosafety certification of central NTRL, including BSL-2 and BSL-3 laboratories to enable safe processing of DR and TB specimens and culture

- ✓

Diagnostic Network decentralization with a strategic expansion of TB diagnostic network at countrywide level

- ✓

Scale-up of molecular WHO-approved rapid diagnostic (mWRD) platforms

- ✓

Implementation of a national specimen transport system ensuring timely sample referral and result feedback.

- ✓

Training and capacity building for laboratory staff in biosafety, molecular diagnostics and data management.

- ✓

Establishment of a national quality management system including external quality assessment (EQA) and WHO SLIPTA audits.

2.6. Data Analysis

All data were entered into Microsoft Excel 365 and analyzed using GraphPad prism 8 and Joinpoint Regression Program (v5.2.0, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA) (11). Descriptive statistics summarized key programmatic indicators, including the number of diagnostic centers and GeneXpert sites, Xpert MTB/RIF and MTB/XDR testing volumes, and HIV testing coverage among TB patients. Joinpoint regression analysis was applied to evaluate temporal trends, identify statistically significant changes in linear trends, and calculate annual percentage change (APC) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), with p-values <0.05 considered significant. This was based on grid search method with minimum number of two observations from a Joinpoint. The parametric method and permutation test were employed for model selection. In this model, period in calendar years was the only independent variable, while all the other variables were treated as dependent, assuming homoscedasticity over time for each test. The calculated APC represents the average yearly rate of change, reflecting the trend’s slope over time (12).

Additional analyses included calculation of absolute and relative changes in TB case detection, MDR/XDR-TB diagnoses, and referral network expansion.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

As this study was based on the analysis of aggregated, routine program-level data for public health monitoring and evaluation, formal individual patient consent was not required. All data were handled in strict accordance with national health data protection policies, ensuring patient confidentiality was maintained. All activities described were conducted under the authority and oversight of the Republic of the Congo’s National Tuberculosis Program. For any questions regarding research integrity, please contact Prof. Franck Hardain OKEMBA-OKOMBI, Director of the National Tuberculosis Control Program, franckokemba@gmail.com

3. Results

3.1. Expansion of the National Tuberculosis Diagnostic Network

Between 2018 and 2024, the republic of Congo achieved substantial progress in strengthening its TB diagnostic network under the coordination of the NTRL. Before establishment (2018) and subsequent operationalization of the NTRL, the country had only 38 to 40 diagnostic and testing centers nationwide.

The NTRL now offers comprehensive TB testing services including microscopy, GeneXpert, line probe assays (LPA), and culture. By October 2025, the number of health facilities significantly increased and reached 113 in 2025 (APC +10.9%, 95% CI: +2.5 to +20, p<0.01)

Table 1.

3.2. Establishing In-Country Capacity for MDR/XDR-TB Testing

Until 2021 the number of facilities offering mWRD was three, countrywide. By 2025, molecular testing capacity had expanded, with 49 facilities performing mWRD across 11/12 departments, enabling decentralization of test with now the proportion of bacteriologically confirmed case of 73% representing a substantial increase (APC+6.8% 95CI 2.5–11.4, p=0.006)

Table 1.

A major step toward drug-resistant TB control was achieved in 2022, when the NTRL acquired a ten-color GeneXpert system enabling in-country detection of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB.

Table 1

Previously (before establishment and during subsequent operationalization, 2022) extended resistance profiles were scarce. In 2023, testing identified 17 mono-resistant, 49 MDR, 36 pre-XDR, and 2 XDR TB cases. In 2024, the number increased to 67 mono-resistant, 90 MDR, 86 pre-XDR, and 2 XDR

Table 2.

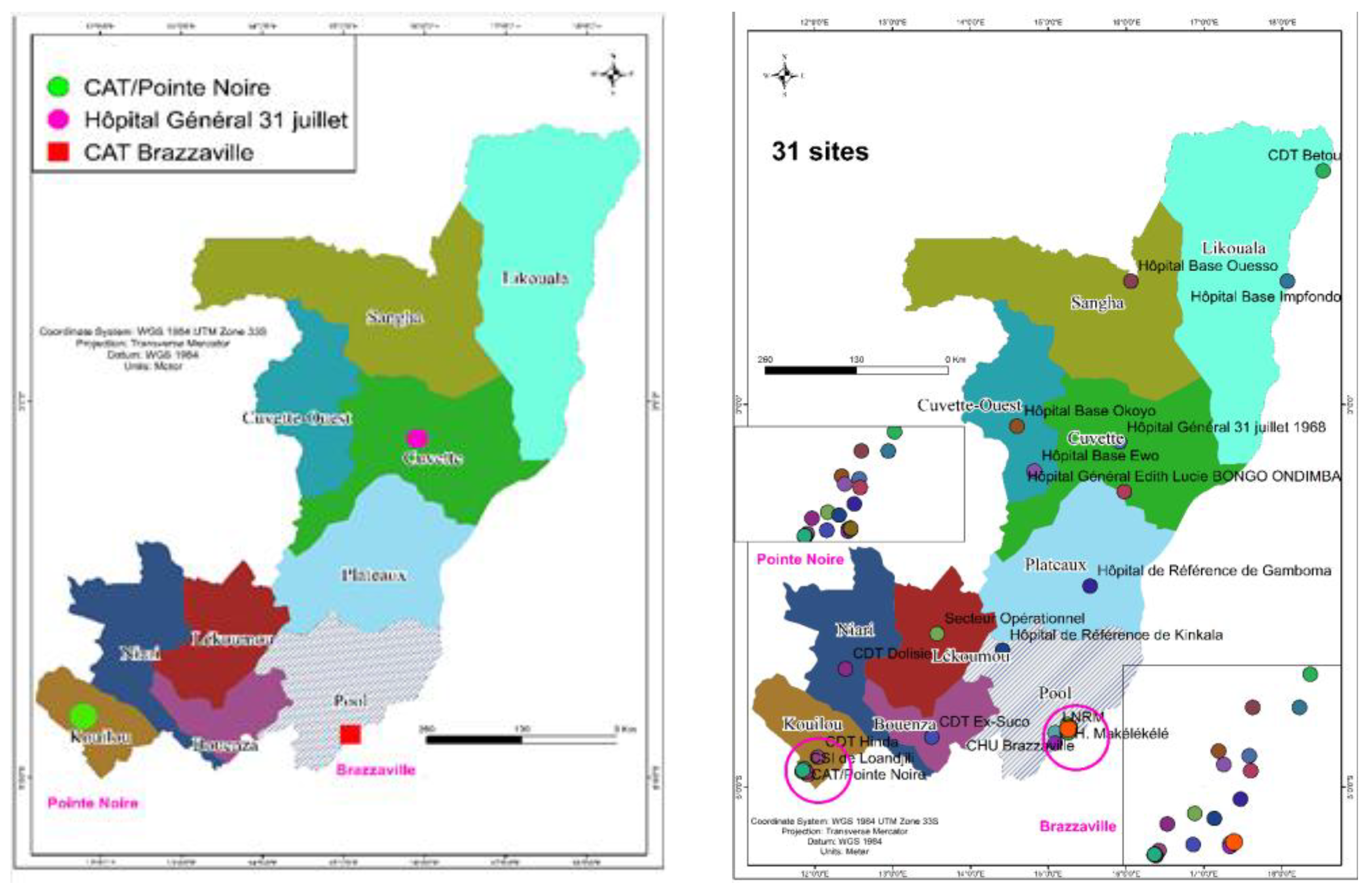

Prior to 2018 (and up to 2022), only three facilities were equipped with the Xpert MTB/RIF tool; by 2024, the number had increased to 31 sites (

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

The number of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra tests rose from 11,609 in 2023 to 22,300 in 2023, reaching 27,318 in 2024 representing an annual percentage change (APC) of 53.46%

Table 2.

3.3. Expansion of the Sample Transport and Referral Network

To enhance access to diagnostics across the country, a national specimen referral network was implemented based on a hub-and-spoke model with defined circuits, fixed schedules, and trained drivers for safe sample handling.

In 2022 (year of establishment), 123 sputum samples were referred from 10 diagnostic and treatment centers (CDTs) in 2 departments. The number rose to 2,154 samples from 29 CDTs in 8 departments in 2023, and 5,160 samples from 49 CDTs in 11 departments in 2024

Table 1.

The transport system also proved adaptable beyond TB. In 2024, it supported emergency sample transfers for suspected monkeypox (MPOX) cases and discussions are ongoing with the National HIV Program to expand the network to cover HIV viral load and early infant diagnosis (EID) specimen transport, maximizing existing logistics capacity.

3.4. Integration of HIV Testing in TB Services

Between 2018 and 2024, the proportion of TB patients tested for HIV increased from 29% to 90%, with an annual percentage change (APC) of 26.2 (95% CI: 2.6–52.6; p < 0.05)

Table 1. This proportion was stable (around 26% for many years prior to 2018).

3.5. Implementation of External Quality Assessment (EQA) Systems

By late 2024, a comprehensive External Quality Assessment (EQA) framework was established under NTRL supervision for all TB testing centers nationwide.

The Supranational Reference Laboratory (SRL) in Cotonou (Benin) provides EQA for microscopy to the NTRL.

Longhorn Vaccines and Diagnostics, LLC (USA) oversees EQA for GeneXpert testing to the NTRL.

The NTRL, in turn, provides EQA for both microscopy and GeneXpert to all active TB centers across the Republic of Congo.

Prior to the establishment of the NTRL, external quality assurance (EQA) for microscopy was limited to a single in-country diagnostic and treatment center (CDT) by the Supranational Reference Laboratory (SRL) in Cotonou, with no subsequent cascade of EQA to other facilities.

3.6. Research Collaborations

Strategic partnerships have expanded substantially. The NTRL currently trains an increasing number of students and collaborates with:

National universities: Marien Ngouabi University and Denis Sassou Nguesso University.

Public research institutes: National Public Health Laboratory, University Hospital of Brazzaville, National Institute for Health Research, and Institute for Research in Exact and Natural Sciences.

Private institutions: Congolese Foundation for Medical Research.

Regionally, the NTRL contributes to ongoing multinational studies with the National Reference Laboratory for Mycobacteria (DRC), CERMEL (Gabon), the Pasteur Institute of Cameroon, and IRESSEF (Senegal). These collaborations position NTRL as an emerging research hub for Central Africa.

3.7. Achievements and Remaining Challenges

Major overall achievement is summarized in

Table 1 and 2. By 2024, the NTLR now ensures national coordination of TB diagnostics and drug resistance surveillance, culture-based therapeutic monitoring, quality assurance across the laboratory network, and integration of advanced molecular epidemiology. The NTLR also made it possible to systematically diagnose HIV in TB patients with a HIV testing rate among TB patients increasing significantly over time.

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the expansion and strengthening of the National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory (NTRL) network in the Republic of Congo between 2018 and 2025, focusing on diagnostic coverage, drug-resistant TB detection, specimen referral, HIV integration, quality assurance, and regional research collaboration. This evaluation provides critical insight into the progress achieved, identifies persisting gaps, and informs strategies to accelerate progress toward WHO End TB targets.

The modernization of the National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory in the Republic of the Congo has markedly reshaped the country’s TB diagnostic landscape. Over less than a decade, the country leapfrogged from a limited diagnostic capacity, reliant on just three GeneXpert sites and outsourcing drug-resistance management to a nationally coordinated network equipped for comprehensive bacteriological testing. These achievements underscore how strategic investments in laboratory systems, human resources, and sample transport can directly translate into increased case detection, improved surveillance, and faster patient management (13).

The rapid decentralization of services, evidenced by the diagnostic network’s expansion from 40 to 113 facilities and GeneXpert sites from 3 to 31 directly aligns with WHO guidelines for universal rapid diagnostics. The WHO recommendations promote universal access to WHO-approved rapid diagnostics (mWRD) as the initial diagnostic test for all presumptive TB cases. Consequently, the observed rise in bacteriological confirmation and rifampicin resistance detection marks a critical improvement in case finding and reporting, establishing a foundation for achieving the End TB Strategy’s 2030 milestones (14).

A critical objective of the NTRL expansion was establishing in-country capacity for multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant TB testing. Until 2021, limited facilities offered advanced molecular WHO-approved rapid diagnostics (mWRD), necessitating costly and time-consuming referrals abroad, to the national center of the Democratic Republic of Congo. By 2025, 49 facilities across 11 of 12 departments were equipped to perform mWRD, significantly decentralizing testing and increasing bacteriological confirmation to 73%. The introduction of a ten-color GeneXpert system and the Xpert MTB/XDR assay in addition to culture (late 2024) allowed in-country detection of second-line resistance, facilitating timely treatment initiation and surveillance. The increase in detected cases MDR, pre-XDR, and XDR reflects improved diagnostic coverage rather than an actual rise in resistance, consistent with observations from other resource-limited settings (15,16). Together, these innovations have not only curtailed diagnostic delays but also enhanced patient management and treatment follow-up by facilitating more timely and appropriate therapeutic interventions.

To overcome geographic and logistical barriers, the NTRL implemented a national specimen transport system using a hub-and-spoke model, representing one of the most impactful interventions. The network expanded from 123 sputum samples referred from 10 centers in 2022 (first year of implementation) to 5,160 samples from 49 centers by 2024. Such systems are critical for linking peripheral health facilities with central laboratories, improving timely diagnosis, and enabling equitable access to care. This network substantially reduced diagnostic inequities between urban and rural populations by ensuring that all presumptive TB patients could access GeneXpert testing, regardless of location. Its successful integration into the national health system demonstrates how logistics platforms for one disease can be leveraged for broader health security, as illustrated by its rapid adaptation to emergency sample transfers for suspected monkeypox cases (during the 2024 epidemic), and discussions are ongoing with the national program of HIV to integrate HIV viral load and early infant diagnosis (EID) specimen transport. Such cross-programmatic use aligns with WHO and Global Fund calls for laboratory network integration to maximize efficiency and sustainability (17–19).

A systematic integration of HIV testing in TB services represents another key achievement. HIV testing coverage among TB patients increased from 29% in 2016 to 90% in 2024, reflecting WHO guidance on collaborative TB/HIV activities. This integration supports early detection of coinfection, timely antiretroviral therapy initiation, and reduced TB-related mortality (18).

Reliable and accurate diagnostics are essential for patient management and surveillance. By late 2024, the NTRL had established a comprehensive external quality assessment (EQA) framework covering all TB centers nationwide. The Supranational Reference Laboratory in Cotonou (Benin) provides microscopy EQA to NTRL, Longhorn Vaccines and Diagnostics (USA) oversees GeneXpert EQA to NTRL, and the NTRL provides both microscopy and GeneXpert EQA to national facilities. This multi-tiered approach ensures consistent quality and strengthens confidence in national TB surveillance data. The two-star WHO SLIPTA rating obtained by the NTRL demonstrates significant progress toward international laboratory accreditation standards (20,21). Sustaining and improving this rating will require continued mentorship, periodic audits, and investment in quality management systems

Strategic research partnerships have positioned NTRL as an emerging hub for TB research in Central Africa. Collaborations include national universities, public research institutes, private research foundations, and regional reference laboratories such as CERMEL (Gabon), Pasteur Institute of Cameroon, and IRESSEF (Senegal). These partnerships enhance research capacity, foster regional knowledge exchange, and facilitate high-quality epidemiological studies.

Nonetheless, several challenges remain. Sustaining infrastructure functionality requires continuous financial investment, reliable reagent and consumable supply chains, and ongoing workforce development to fully operationalize available technologies. The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for molecular surveillance remains underutilized and will be crucial for high-resolution monitoring of transmission dynamics and resistance evolution. Ensuring long-term sustainability, data-driven decision-making, and domestic resource mobilization will be essential to consolidate gains and achieve national TB elimination goals.

Evidence from India, Uganda, Portugal, and Congo confirms that NTRL investments yield significant public health returns. This enhanced diagnostic access, accuracy, and surveillance quality, even in resource-limited settings. Securing long-term sustainability for the NTRL is both a technical necessity and a strategic imperative for containing TB and strengthening national health security. Continued political commitment, domestic financing, and integration of TB diagnostics into broader disease surveillance frameworks will be also critical to maintaining momentum and achieving national and global End TB targets.

The country’s successful strengthening of its National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory offers a critical model for other high-burden countries, yielding clear policy implications. To replicate this success, governments must formally prioritize the NTRL as indispensable public health infrastructure within their national TB strategic plans, backed by dedicated and sustainable budget lines for its continuous operations, maintenance, and essential consumables. This foundation must be supported by a long-term investment in human resources, expanding technical capacity through robust staff development and continuous training. Furthermore, the strategic value of this laboratory investment should be leveraged beyond TB, integrating its capabilities into broader health agendas such as antimicrobial resistance (AMR) monitoring and pandemic preparedness. Finally, fostering regional collaboration for external quality assessment, mentorship, and data-sharing will amplify the impact of national investments, creating a resilient and interconnected laboratory network capable of effectively controlling TB and strengthening overall health security.

5. Conclusion

The Republic of Congo NTRL demonstrates how sustained long-term investments over a 7-8 year period have led to significant advances in technical capacity, expanding access to rapid molecular diagnostics and drug susceptibility testing, improved MDR-TB detection, and enhanced surveillance accuracy.

Author Contributions

DOEA and FHOO designed the study. DOEA contributed to the study design and collected the data. STB, JTK, FHM and ADK analyzed the data. DOEA and DA had overall responsibility for the study. AJ, DA, JEB, NS, LC and HTA edited and revised drafts and finalized the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, read, and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Tuberculosis Control Program (NTCP) and the Ministry of Health and Population of the Republic of Congo, as well as by technical and financial partners, notably the Global Fund through the GC7 grant, with UNDP as the principal recipient and the NTCP as the sub-recipient.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all members of the NTRL and the technical assistants and collaborators who have supported our work over the years. We also express our gratitude to the National Tuberculosis Control Program and the Ministry of Health and Population for their support. This work was made possible with the assistance of technical and financial partners, including the Global Fund, UNDP and WHO, as well as through the collaboration of all national and international institutions involved in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AI declaration

No AI tools were used for data collection, data analysis, or interpretation of study results.

References

- Global tuberculosis report 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240101531.

- Global tuberculosis report 2019 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-tuberculosis-report-2019.

- Klaos K, Holicka Y, Groenheit R, Ködmön C, Van Der Werf MJ, Nikolayevskyy V. Current state of national TB laboratory networks in Europe: achievements and challenges. int j tuberc lung dis. 2022 Jan 1;26(1):71–3.

- Drobniewski FA, Nikolayevskyy V, Hoffner S, Pogoryelova O, Manissero D, Ozin AJ. The added value of a European Union tuberculosis reference laboratory network – analysis of the national reference laboratory activities. Eurosurveillance. 2008 Mar 18;13(12):9–10.

- Laboratory Professionals in Africa : The Backbone of Quality Diagnostics. 2014 Nov [cited 2025 Nov 4]; Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/21115.

- Petti CA, Polage CR, Quinn TC, Ronald AR, Sande MA. Laboratory medicine in Africa: a barrier to effective health care. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Feb 1;42(3):377–82.

- Husain AA, Kupz A, Kashyap RS. Controlling the drug-resistant tuberculosis epidemic in India: challenges and implications. Epidemiol Health. 2021 Apr 7;43:e2021022.

- Strengthening laboratory capacity to diagnose multidrug-resistant tuberculosis [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/activities/strengthening-laboratory-capacity-to-diagnose-multidrug-resistant-tuberculosis.

- Pinto M, Macedo R. Whole-genome sequencing-based surveillance system for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Portugal. Tuberculosis. 2025 Dec 1;155:102691.

- TB-Lab – SRL Cotonou [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://srlcotonou.org/nos-projets/tb-lab/.

- Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000 Feb 15;19(3):335–51.

- Lungu P, Kasapo C, Mihova R, Chimzizi R, Sikazwe L, Banda I, et al. A 10-year Review of TB Notifications and Mortality Trends Using a Joint Point Analysis in Zambia - a High TB burden country. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2022 Nov;124:S30–40.

- Chekol L, Waktola E, Nawaz S, Tadesse L, Muluye S, Bonger Z, et al. Laboratory capacity expansion: lessons from establishing molecular testing in regional referral laboratories in Ethiopia. Int Health. 2025 Mar 1;17(2):123–7.

- Implementing the End TB Strategy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/activities/implementing-the-end-tb-strategy.

- Summary of changes to recommendations. In: WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis: Module 6: Tuberculosis and comorbidities [Internet] [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK603421/.

- Global Plan to End TB | Stop TB Partnership [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.stoptb.org/what-we-do/advocate-endtb/global-plan-end-tb.

- Molecular diagnostics integration global meeting report [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://wkc.who.int/resources/publications/i/item/molecular-diagnostics-integration-global-meeting-report.

- Integrated Laboratory Systems and Diagnostic Networks [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://resources.theglobalfund.org/en/c19rm/integrated-laboratory-systems-and-diagnostic-networks/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Laboratory Systems Strengthening [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/resilient-sustainable-systems-for-health/laboratory-systems/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Maruta T, Motebang D, Mathabo L, Rotz PJ, Wanyoike J, Peter T. Impact of mentorship on WHO-AFRO Strengthening Laboratory Quality Improvement Process Towards Accreditation (SLIPTA). African Journal of Laboratory Medicine. 2012 Feb 1;1(1):e1–8.

- Perovic O, Yahaya AA, Viljoen C, Ndihokubwayo JB, Smith M, Coulibaly SO, et al. External Quality Assessment of Bacterial Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing in African National Public Health Laboratories, 2011-2016. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019 Dec 13;4(4):144.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).