1. Introduction

Drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) remains one of the most complex challenges facing global TB control efforts, particularly in low-resource, high-burden settings. South Africa continues to be one of the countries with the highest burden of both multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB), accounting for a significant proportion of global DR-TB cases [

1]. Within South Africa, the rural Eastern Cape province is disproportionately affected due to its high levels of poverty, limited healthcare infrastructure, and co-existing HIV epidemic [

2] similar to other African countries [

3,

4].

While pharmacological management of DR-TB has improved over the past decade with the introduction of shorter regimens and new drugs like bedaquiline and delamanid, treatment outcomes remain suboptimal. Data indicate that cure and treatment completion rates for DR-TB are still well below global targets, with high rates of loss to follow-up (LTFU), mortality, and treatment failure, especially in rural settings [

5,

6]. These poor outcomes are often driven not just by biological or pharmacological factors, but by systemic weaknesses in clinical governance and public health response such as fragmented TB/HIV integration, inconsistent patient follow-up, and insufficient community-level engagement [

7].

Clinical governance is the framework through which healthcare organizations are accountable for continually improving the quality of their services [

8,

9]. Clinical and care governance while ensuring accountability in quality of health services rendered, also enhances better social care [

10]; thus playing a critical role in ensuring the effectiveness of DR-TB programs. In the context of rural South Africa, the implementation of robust governance structures is often hindered by workforce shortages, limited training, and data management challenges. Similarly, public health interventions such as community-based care models, digital adherence technologies, and psychosocial support systems remain underutilized despite their proven efficacy in improving treatment adherence and retention [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Survival analysis provides a valuable methodological lens for understanding the temporal dynamics of DR-TB treatment, including when adverse events such as death or LTFU are most likely to occur. These insights can inform clinical audits, trigger early interventions, and strengthen public health planning at both facility and policy levels. This study aims to apply survival analysis techniques to a cohort of DR-TB patients in rural Eastern Cape, with the dual objectives of identifying high-risk periods and population subgroups and informing improvements in clinical governance and public health strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study employed a retrospective cohort design to investigate treatment outcomes and associated risk factors among patients diagnosed with DR-TB in the rural Eastern Cape province of South Africa. The region is characterized by a high burden of both TB and HIV, limited healthcare infrastructure, and socioeconomic deprivation.

2.2. Study Population

The cohort consisted of 323 patients diagnosed with laboratory-confirmed DR-TB and initiated on treatment between February 2018 and December 2021. Patients were enrolled from multiple rural healthcare facilities offering decentralized DR-TB care in the Eastern Cape.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study included patients who had confirmed diagnosis of DR-TB, initiated treatment during the study period, and had complete clinical records with adequate follow-up data. Patients were excluded if they had missing or incomplete key clinical variables or if they were transferred into the study facilities without sufficient treatment history to assess outcomes accurately.

2.4. Data Collection

Patient demographic, clinical, and treatment outcome data were extracted from facility TB registers and medical records using a standardized data abstraction tool. Variables collected included age, sex, BMI, TB category, HIV status, comorbidities, drug resistance type, previous TB treatment history, and final treatment outcome.

2.5. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was time to an unfavorable treatment outcome, including LTFU, treatment failure, death, or transfer out. Favorable outcomes were defined as cure or treatment completion according to WHO definitions. Patients still on treatment at the end of the follow-up period were censored.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to estimate time-to-event distributions, and log-rank tests assessed differences across subgroups. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to identify predictors of unfavorable outcomes, with variables significant at p < 0.1 in univariate analysis included in the multivariate model. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using Python version 3.8. and R version 4.1.1 software. A p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Among the 323 patients included in the study, 56% were male and the median age was 33 years (IQR: 26–42). The majority (62%) were HIV-positive. Most patients had pulmonary TB (99%), with MDR-TB (43%) and RR-TB (45%) being the most common resistance patterns. Education levels were low, with 20% having no formal education and only 10% having tertiary education. Most participants had no income (83%) and were classified as minors or unemployed (

Table 1).

3.2. Treatment Outcomes

Treatment outcomes were as follows: cure (36.2%), treatment completion (26.0%), LTFU (9.0%), treatment failure (2.2%), death (9.3%), transfer out (9.3%), and still on treatment at study close (8.1%). The median treatment duration was 10 months (IQR: 9–11).

Clinical characteristics in

Table 1 significantly influenced treatment outcomes among DR-TB patients. Normal BMI was associated with higher cure and completion rates, while underweight patients faced increased mortality and LTFU. New TB cases had the best outcomes, whereas those with prior treatment—especially PT2—were more likely to fail treatment. HIV co-infection was common and linked to higher rates of death and failure, while HIV-negative patients had better outcomes. Most patients had no comorbidities, but those with conditions like diabetes tended to remain on treatment longer. Polyresistant and MDR-TB were more frequent and associated with worse outcomes. The median treatment duration was 10 months, varying by outcome. HIV status, treatment history, BMI, and resistance type were key predictors of treatment success. The median treatment duration was 10 months (IQR: 9–11 months), with those who completed treatment averaging 11 months (IQR: 10–12), while LTFU cases had a shorter median duration of 9 months (IQR: 6–10). Transferred-out patients had the shortest treatment period (median 2 months, IQR: 1–5), suggesting early discontinuation or referral. These findings highlight the influence of clinical and demographic factors—particularly prior treatment history, HIV status, BMI, and drug resistance type—on treatment outcomes and duration in DR-TB patients.

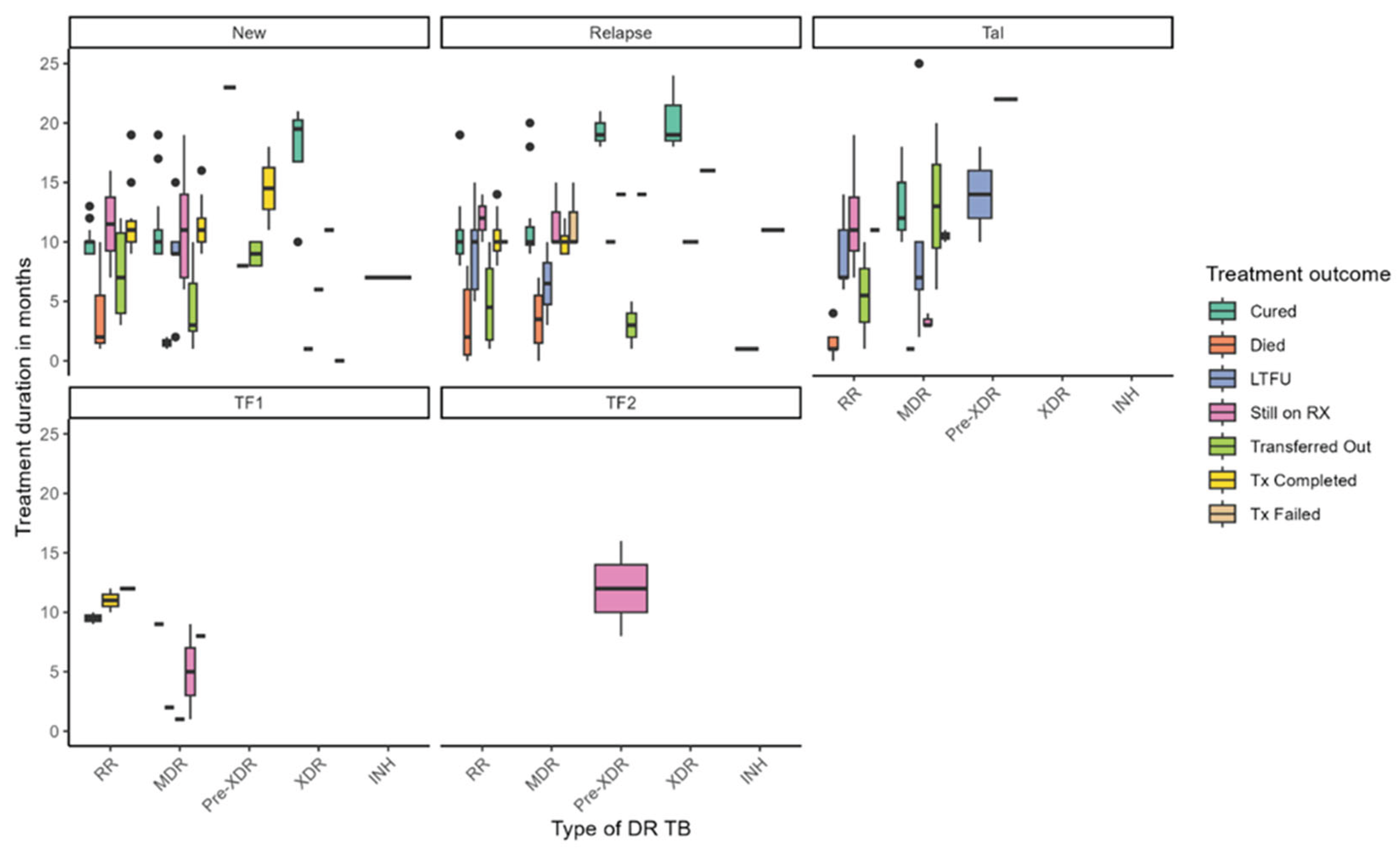

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of treatment duration and outcomes across different types of DR-TB, stratified by TB history—New, Relapse, TAL, and treatment failure categories (TF1, TF2). Treatment durations varied widely across DR-TB types, with median durations ranging from approximately 4 to over 20 months. Longer treatment durations were generally associated with favorable outcomes such as cure and treatment completion, while shorter durations were linked to LTFU and mortality. Notably, patients with Pre-XDR-TB under the TF2 failure category exhibited the longest treatment durations, exceeding 12 months. Among new TB cases, individuals with MDR-TB and Pre-XDR-TB experienced extended treatment courses, whereas RR-TB patients with TF1 failure had shorter durations. Treatment outcomes also varied substantially by resistance type: cure rates were highest among patients with MDR-TB and RR-TB, particularly in new cases. At the same time, mortality was more prevalent in XDR-TB and Pre-XDR-TB groups and occurred earlier in treatment. LTFU was observed across all DR-TB categories but was more frequent in MDR-TB and RR-TB cases. Patients Still on RX appeared across various subgroups, indicating ongoing clinical challenges, while transferred-out cases were more common among those with longer treatment durations. Treatment failure was primarily concentrated in pre-XDR-TB cases. These findings underscore the complexity of managing DR-TB and highlight the influence of resistance type and treatment history on both duration and outcomes. They point to the need for tailored strategies to reduce mortality, enhance treatment adherence, and support patients throughout prolonged treatment regimens.

3.3. Survival Analysis Findings

Survival analysis revealed that the risk of adverse treatment outcomes was most pronounced during the first 6 to 8 months of therapy, with the highest incidence of mortality and LTFU occurring during this period. Conversely, the likelihood of cure and treatment completion peaked between 9 and 12 months. In multivariate Cox regression in

Table 2, both primary (HR = 0.39; 95% CI: 0.23–0.68; p = 0.0017) and secondary education (HR = 0.50; 95% CI: 0.31–0.85; p = 0.0103) were significantly protective, suggesting that educational attainment plays a key role in fostering treatment adherence and engagement. Surprisingly, patients with pre-XDR TB (HR = 0.13; 95% CI: 0.03–0.81; p = 0.034) and XDR TB (HR = 0.16; 95% CI: 0.03–0.94; p = 0.043) were associated with lower hazard of poor outcomes, possibly reflecting early mortality or transfer bias. Additionally, HIV-negative status was linked with an increased risk of unfavorable outcomes (HR = 1.74; 95% CI: 1.13–2.66; p = 0.010), highlighting a potential gap in support systems for patients not enrolled in HIV care programs. Subgroup analyses further revealed that young adults aged 20–29 experienced disproportionately high LTFU rates, while HIV-positive and underweight individuals had elevated mortality, underscoring the need for targeted interventions within these high-risk groups.

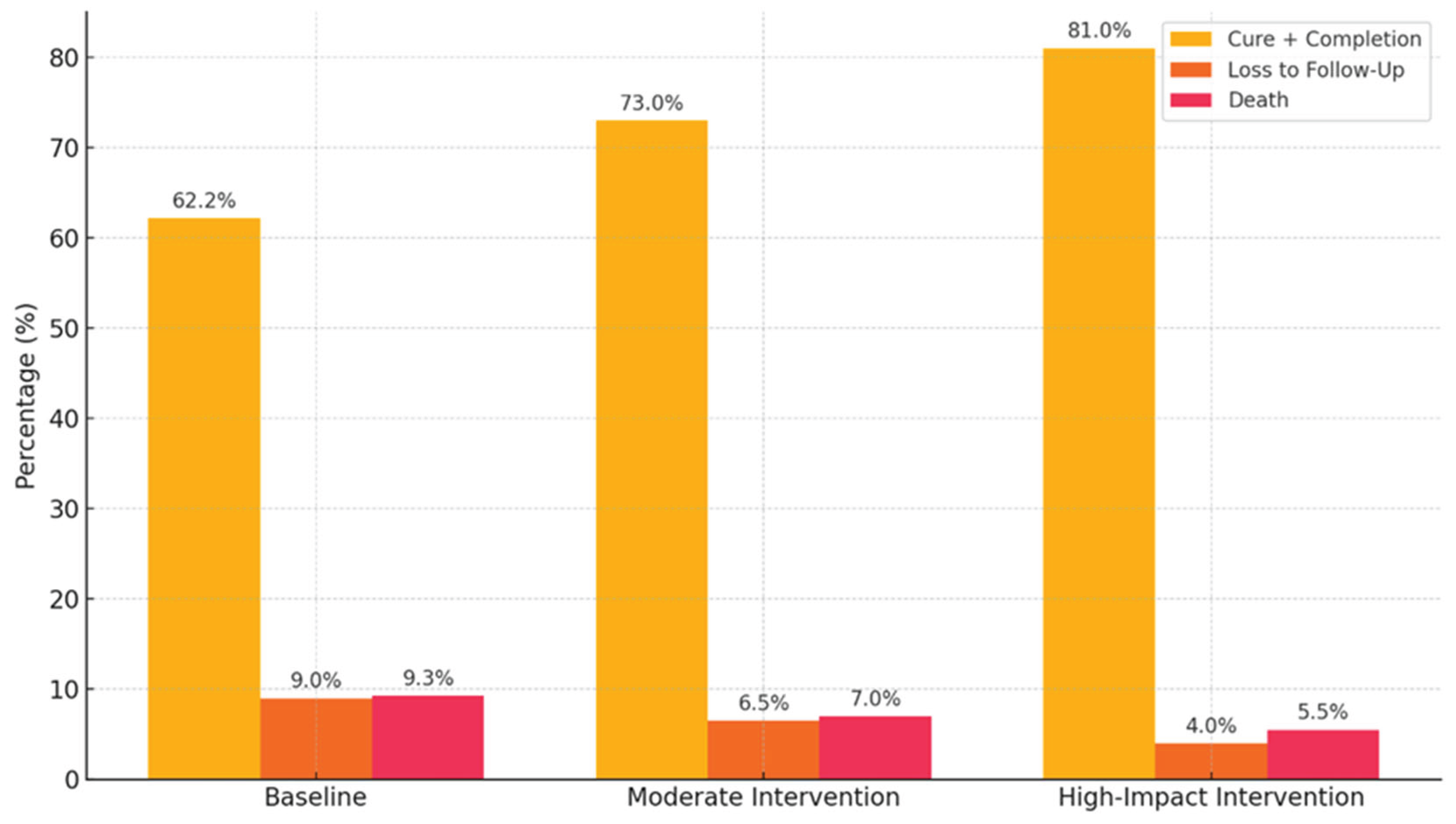

Assessing the potential impact of enhanced clinical governance interventions (e.g., improved patient follow-up, TB/HIV integration, health worker accountability) on treatment outcomes specifically loss to follow-up, mortality, and treatment completion among DR-TB patients, a predictive analysis approach was employed to evaluate the potential impact of enhanced clinical governance on DR-TB treatment outcomes using proxy indicators derived from the existing dataset. Given the abstract nature of clinical governance, variables such as education level (as a proxy for health communication), previous TB treatment history (reflecting follow-up system gaps), HIV co-infection status (indicating TB/HIV service integration), treatment duration and timing of loss to follow-up, and occupation or income (as indicators of social support) were used to analyze governance-related influences. A logistic regression framework was applied to estimate the likelihood of favorable outcomes—defined as cure or treatment completion—versus unfavorable outcomes, including LTFU, death, treatment failure, or transfer. The analysis incorporated hypothetical scenarios reflecting incremental improvements in clinical governance: a baseline using current data, a moderate intervention scenario (30% reduction in LTFU and 15% increase in adherence among HIV-positive individuals), and a high-impact scenario simulating a 50% reduction in LTFU, full TB/HIV integration, and targeted support for previously treated patients. Predicted probabilities of treatment success were calculated for each scenario, offering insights into the potential gains achievable through strategic system-level reforms.

Figure 2 presents simulated results of strengthening clinical governance through targeted interventions that hold substantial promise for improving DR-TB treatment outcomes. Enhanced patient follow-up systems could significantly reduce LTFU, particularly among younger, male patients who are most vulnerable to disengagement from care. Simultaneously, integrating TB and HIV services at the primary care level would likely reduce early mortality by enabling timely co-treatment and improving adherence. Educational interventions such as structured counseling and community outreach are essential for improving outcomes among patients with limited literacy, empowering them to engage more effectively with care. Combined, these strategies within a robust clinical governance framework supported by adherence audits and digital follow-up tools could improve treatment success rates by up to 20 percentage points in high-impact rural settings.

4. Discussion

This study underscores critical gaps in DR-TB care that have far-reaching implications for clinical governance and public health systems in rural South Africa. High rates of LTFU and mortality, particularly among HIV-positive individuals, young adults, and those with poor socioeconomic status, highlight systemic weaknesses in adherence support, care continuity, and service integration.

The higher mortality rates observed in patients with pre-XDR-TB and XDR-TB compared to other TB patients may be attributed to a combination of biological, immunological, and treatment-related factors. These factors contribute to the severity and complexity of the disease, leading to poorer outcomes. XDR-TB characterized by resistance to first line and second-line drugs, complicate treatment alternatives thereby leading to higher mortality rates [

15]. Patients often present with significant comorbid conditions, such as malnutrition (BMI < 18.5 kg/m²) and chronic diseases, which exacerbate their health status and increase mortality risk [

16]. A substantial proportion of XDR-TB patients are co-infected with HIV, which severely compromises the immune system and contributes to higher mortality rates [

17,

18]. Previous studies have documented significant association between previous anti-TB treatment (ATT) history and the incidence of pre-XDR-TB and XDR-TB [

19,

20].

The protective effect of basic education suggests that public health interventions must incorporate health literacy components while also addressing structural barriers like transportation, income insecurity, and treatment fatigue [

21,

22]. Strengthening clinical governance requires systematic follow-up mechanisms, audit-based accountability, and investment in human resources and digital health solutions [

23,

24,

25]. Unexpected findings such as hazard among XDR-TB patients may reflect data limitations or programmatic decisions to transfer patients to higher-level facilities early in treatment. Nevertheless, the use of survival analysis in this context is a powerful tool for identifying critical intervention windows and improving patient tracking in clinical settings thus providing insights that can inform treatment strategies and improve patient outcomes [

26,

27,

28].

A coordinated, multi-sectoral approach is necessary to improve DR-TB outcomes combining strong clinical oversight, patient-centered community engagement, and adaptive public health policy tailored to vulnerable subgroups. This combined strategy not only aligns with global TB elimination targets but also fortifies health systems to combat syndemics like TB/HIV, fostering resilience against future health crises.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study carry important implications for policy and practice, particularly in rural, high-burden settings. Targeted clinical governance reforms such as structured patient tracking systems, community-based adherence support, and digital monitoring tools have the potential to significantly improve DR-TB treatment outcomes. Realizing these improvements require sustained investment in human resource development, the establishment of patient navigation systems, and the integration of TB services with broader health platforms, particularly HIV care, can lead to more effective management of DR-TB and better health outcomes in rural communities. Importantly, the study supports the adoption of multi-sectoral strategies that align clinical governance with public health objectives, with a particular focus on high-risk subgroups including youth, individuals with prior TB treatment, and people living with HIV. Strengthening coordination across these levels of care is essential to closing the gaps in treatment retention and survival.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.H. and U.T.; methodology, U.T.; software, U.T.; L.M.F.; validation, U.T., M.C.H. N.D.; and L.M.F.; formal analysis, U.T.; investigation, M.C.H.; U.T.; L.M.F.; resources, L.M.F.; data curation, M.C.H.; L.M.F.; N.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.H.; L.M.F.; writing—review and editing, M.C.H., U.T.; N.D.; L.M.F.; T.A.; visualization, U.T.; L.M.F.; M.C.H.; supervision, T.A.; project administration, L.M.F.; funding acquisition, L.M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by South African Medical Research Council Pilot grant and The APC was funded by Walter Sisulu University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee of Walter Sisulu University (ref. no. 026/2019) and permission to carry out the study was obtained from the Eastern Cape Department of Health (ref. No. EC_201904_011).

Informed Consent Statement

This study involved retrospective review of medical records and as such there was no reason for written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be requested from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the gatekeepers in the healthcare facilities who granted us access to medical records. The authors are grateful for the assistance rendered by colleagues during data collection and management.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| DR-TB |

Drug-resistant tuberculosis |

| LTFU |

Loss to Follow Up |

| IQR |

Inter quartile range |

| HR |

Hazard ratio |

| MDR-TB |

Multidrug resistant tuberculosis |

| XDR-TB |

Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| WHO |

World Health Organizstion |

| Tal |

Treatment after loss to follow up |

| TF1 |

Treatment failure after first line drug |

| TF2 |

Treatment failure after second line drug |

| PT1 |

Previously treated with first line drug |

| PT2 |

Previously treated with second line drug |

| UNK |

Unknown |

| HTN |

Hypertension |

| T2DM |

Type 2 Diabetes mellitus |

| PTB |

Pulmonary tuberculosis |

| EPTB |

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis |

| TB |

Tuberculosis |

| RR-TB |

Rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis |

| INH-R |

Isoniazid resistant |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| UIF |

Unemployment Insurance Fund |

| DG |

Disability Grant |

| ATT |

Anti-tuberculosis treatment |

References

- Global tuberculosis report 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/373828/9789240083851-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Faye, L.M.; Hosu, MC.; Iruedo, J.; Vasaikar, S.; Nokoyo, K.A.; Tsuro, U.; Apalata, T. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among tuberculosis patients from selected rural eastern cape hospitals: An ambidirectional study. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2023, 8, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katana, G.G.; Ngari, M.; Maina, T.; Sanga, D.; Abdullahi, O.A. Tuberculosis poor treatment outcomes and its determinants in Kilifi County, Kenya: a retrospective cohort study from 2012 to 2019. Arch Public Health 2022, 80, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opito, R.; Kwenya, K.; Ssentongo, S.M.; Kizito, M.; Alwedo, S.; Bakashaba, B.; Miya, Y.; Bukenya, L.; Okwir, E.; Onega, L.A.; Kazibwe, A. Treatment success rate and associated factors among drug susceptible tuberculosis individuals in St. Kizito Hospital, Matany, Napak district, Karamoja region. A retrospective study. PLoS One. 2024, 19, e0300916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andargie, A.; Molla, A.; Tadese, F.; Zewdie, S. Lost to follow-up and associated factors among patients with drug resistant tuberculosis in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0248687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibuule, D.; Aiases, P.; Ruswa, N.; Rennie, T.W.; Verbeeck, R.K.; Godman, B.; Mubita, M. Predictors of loss to follow-up of tuberculosis cases under the DOTS programme in Namibia. ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, N. Structure and agency in the economics of public policy for TB control. Faculty of Health Sciences Department of Public Health and Family Medicine, 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11427/31228 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Clinical Governance Standards: Scope. Available online: https://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.scot/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Clinical-Governance-Standards-Scope-May-2025.pdf (accessed on 28 May, 2025).

- Macfarlane, A.J.R. What is clinical governance? BJA Educ 2019, 19, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadifar, M.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Arab-Zozani, M.; Bakhtiari, A.; Behzadifar, M.; Beyranvand, T.; Yousefzadeh, N.; Azari, S.; Sajadi, H.S.; Saki, M.; Saran, M. The challenges of implementation of clinical governance in Iran: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Health Res. Policy Syst, 2019, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.B.; Davies, G.; Malwafu, W.; Mangochi, H.; Joekes, E.; Greenwood, S.; Corbett, L.; Squire, S.B. Poor outcomes in recurrent tuberculosis: More than just drug resistance? PLoS One 2019, 14, e0215855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, V.C.; Thomas, C.K.J.; Jabbarpour, Y.; Scheufele, E.L.; Arriaga, Y.E.; Ajinkya, M.; Rhee, K.B.; Bazemore, A. Digital health interventions to enhance prevention in primary care: scoping review. JMIR Med Inform. 2022, 10, e33518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipschitz, J.M.; Pike, C.K.; Hogan, T.P.; Murphy, S.A.; Burdick, K.E. The engagement problem: a review of engagement with digital mental health interventions and recommendations for a path forward. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 2023, 10, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E.E.; Wolfe, E.C.; Huguenel, B.M.; Wilhelm, S. Lessons and untapped potential of smartphone-based physical activity interventions for mental health: narrative review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2024, 12, e45860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jassal, M.; Bishai, W.R. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis, 2009, 9, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bei, C.; Fu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, H.; Yin, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xie, B.; Li, F.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y. H.; Yang, L.; Zhou, J. Mortality and associated factors of patients with extensive drug-resistant tuberculosis: an emerging public health crisis in China. BMC Infect. Dis, 2018, 18, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M.R.; Padayatchi, N.; Kvasnovsky, C.; Werner, L.; Master, I.; Horsburgh Jr, C.R. Treatment outcomes for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV co-infection. Emerging Infect. Dis, 2013, 19, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayowa, J.R.; Kalyango, J.N.; Baluku, J.B.; Katuramu, R.; Ssendikwanawa, E.; Zalwango, J.F.; Akunzirwe, R.; Nanyonga, S.M.; Amutuhaire, J.S.; Muganga, R.K.; Cherop, A. Mortality rate and associated factors among patients co-infected with drug resistant tuberculosis/HIV at Mulago National Referral Hospital, Uganda, a retrospective cohort study. PLOS Global Public Health, 2023, 3, e0001020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinulingga, H.E.; Sinaga, B.Y.; Siagian, P.; Ashar, T. Profile and risk factors of pre-XDR-TB and XDR-TB patients in a national reference hospital for Sumatra region of Indonesia. Narra J, 2023, 3, e407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parolina, L.E.; Otpuschennykova, O.; Kazimirova, N.; Doktorova, N. Social determinants and co-morbidities of patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. European Respir. J 2020, 56 Suppl. 64, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, E.; Mitchell, C.H.; Ngo-Huang, A.; Manne, R.; Stout, N.L. Addressing social determinants of health to reduce disparities among individuals with cancer: insights for rehabilitation professionals. Curr Oncol. Rep. 2023, 25, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, K.I.; Wiedt, T.L.; Daniels, E.C.; Yabroff, K.R.; Guerra, C.E.; Wender, R.C. Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: a blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2020, 70, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavamabad, L.H.; Vosoogh-Moghaddam, A.; Zaboli, R.; Aarabi, M. Establishing clinical governance model in primary health care: A systematic review. J Educ Health Promot, 2021, 10, 338. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, A. Clinical Governance and Risk Management for Medical Administrators; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.; Jones, S. Clinical governance in practice: closing the loop with integrated audit systems. J. Psychiatric Mental Health Nurs 2006, 13, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadhil, E.A.; Al-Sarray, B. Unified Machine Learning Techniques for High-Dimensional Survival Data Analysis. Iraqi J Sci 2024, 6660–6660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denfeld, Q.E.; Burger, D.; Lee, C.S. Survival analysis 101: an easy start guide to analysing time-to-event data. Eur. J. Cardiovasc Nurs 2023, 22, 332–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, N.R.; Gouda, D.; Bhuyan, S.K.; Bhuyan, R. Survival Analysis in Oral Cancer Patients: A Reliable Statistical Analysis Tool. Natl J. Comm. Med. 2023, 14, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).