1. Introduction

Drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) remains a major global health challenge, threatening progress toward the World Health Organization (WHO) End TB targets. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that approximately 10.6 million new tuberculosis cases were identified in 2022, reflecting a 3.5% increase compared to the 10.3 million cases documented in 2021. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, TB incidence rose by 3.9% between 2020 and 2022. [

1,

2]. In 2022, an estimated 410,000 people (95% CI: 370,000–450,000) worldwide developed multidrug-resistant or rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (MDR/XDR-TB). However, the number of patients who were actually diagnosed and initiated on treatment was much lower, 175,650 representing only about two out of every five people in need. This figure also remains below the pre-pandemic level of 181,533 recorded in 2019 [

3]. South Africa is among the countries with the highest DR-TB burden, with the Eastern Cape Province contributing disproportionately to national case notifications [

4]. Despite significant investments in new diagnostics, shorter regimens, and decentralized models of care, DR-TB continues to be associated with high mortality, treatment failure, and loss to follow-up [

5]. Treatment outcomes in DR-TB are influenced by a combination of biomedical, social, and health system factors [

6,

7]. Clinical predictors such as HIV co-infection, drug-resistance patterns, and previous TB treatment history have consistently been associated with poor prognosis [

8]. However, growing evidence highlights the role of social determinants including poverty, education, occupation, and gender in shaping adherence and treatment success [

9,

10]. Behavioral factors, such as smoking and alcohol use, further exacerbate risks of treatment failure. Despite this evidence, few studies have simultaneously examined the relative importance of clinical and social predictors in high-burden rural South African settings.

The Eastern Cape faces unique challenges of poverty, high HIV prevalence, and limited health system capacity, making it a critical setting to examine determinants of DR-TB outcomes [

11]. Understanding how demographic, socioeconomic, clinical, and behavioral factors jointly influence treatment trajectories is essential for designing targeted interventions. Traditional statistical approaches, such as logistic regression, provide interpretable effect sizes but may overlook complex, nonlinear interactions. Machine-learning methods such as random forests can complement regression by ranking predictors and enhancing predictive performance. Integrating descriptive, regression, and machine-learning approaches offers a comprehensive framework for identifying patients at greatest risk and informing clinical and policy responses [

12].This study aimed to evaluate the influence and determinants of DR-TB and HIV co-infected patients treatment outcomes in the rural Eastern Cape by combining cross-tabulation, logistic regression, and random forest modelling. Specifically, we sought to (i) describe the distribution of outcomes across demographic, socioeconomic, clinical, and behavioral predictors; (ii) estimate the adjusted associations between key predictors and treatment success using logistic regression; and (iii) assess the relative importance of predictors and predictive performance using random forest analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using routinely collected clinical records of patients with DR-TB who were initiated on treatment at two purposively selected public health clinics in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, between January 2020 and December 2024. The sites were chosen to capture both rural and peri-urban contexts within the province. A total of 385 patients with complete demographic, clinical, and treatment outcome data were included in the analysis, while those with missing outcome information or incomplete records were excluded. Eligible cases comprised individuals with microbiologically confirmed rifampicin-resistant (RR-TB), multidrug-resistant (MDR-TB), pre-extensively drug-resistant (Pre-XDR-TB), or extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB). These categories were included as they reflect the full clinical spectrum of DR-TB currently recognized by the World Health Organization, ensuring comparability with global evidence. Retrospective data were used to maximize sample size and capture real-world treatment outcomes under routine programme conditions.

2.2. Study Population and Inclusion Criteria

All patients with complete baseline demographic, socioeconomic, clinical, and treatment outcome data were eligible. Patients who were transferred out, moved away, or remained on treatment at the time of analysis were excluded from regression and predictive modelling. Outcomes were classified according to WHO and South African National TB Programme definitions.

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Variables and Outcomes

For analysis, treatment outcomes were collapsed into two categories: successful (cured or treatment completed) and unsuccessful (loss to follow-up, treatment failure, or death). Independent variables were grouped into three domains. Demographic variables included age (continuous and grouped), gender, education level, occupation, and income status. Clinical variables comprised HIV status, presence of comorbidities, previous drug history, patient category (new case, relapse, treatment after loss to follow-up, or treatment failure), DR-TB type (RR-TB, MDR-TB, Pre-XDR-TB, or XDR-TB), and resistance pattern (mono- vs poly-resistance). Behavioral and social variables included smoking status, alcohol and drug use, social history, and employment history.

2.3.2. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using a stepwise approach. First, descriptive statistics were generated: frequencies and proportions were calculated for categorical variables, and means with standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. Cross-tabulations were performed to compare treatment outcomes across key predictors. Group differences were tested for statistical significance using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and independent-samples t-tests for continuous variables. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CIs) were computed where applicable. Network associations were evaluated using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Edges were included when p < 0.10, with edge width proportional to −log10(p). Directional associations were based on adjusted residuals from contingency tables; values > |1.96| were interpreted as statistically significant. Second, binary logistic regression was employed to identify independent predictors of treatment success. Variables with a significance level of p < 0.20 in univariate analyses, as well as those considered clinically relevant, were entered into the multivariable model. Odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% CIs were reported. Model performance was assessed using overall classification accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Finally, random forest modelling was used to account for potential nonlinear relationships and to rank the relative importance of predictors. A random forest classifier with 500 trees and default hyperparameters was implemented. Model performance was evaluated based on accuracy, precision, recall, and AUC. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) for descriptive and logistic regression models, and Python version 3.11 with the scikit-learn library version 1.3 for machine learning analyses.

3. Results

The mean age of patients with successful outcomes was 38.4 years (SD 10.3) compared to 40.3 years (SD 13.5) among those with unsuccessful outcomes; this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.361, 95% CI: −5.8 to 2.1). Gender showed a significant association with treatment outcome. Male patients were more likely to achieve treatment success (63.0% vs. 46.3%), whereas females had a higher proportion of unsuccessful outcomes (53.7% vs. 37.0%; both p=0.031, 95% CI: 0.01–0.32 for males and −0.32 to −0.01 for females). Education did not significantly influence treatment outcome, with comparable distributions across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels (all p > 0.2). Income status was strongly associated with outcome. Patients dependent on disability grants had significantly higher rates of unsuccessful outcomes (20.4% vs. 4.9%, p=0.001, 95% CI: −0.27 to −0.04), while those with no income were also more likely to have unsuccessful outcomes (66.7% vs. 84.0% successful, p=0.006, 95% CI: 0.03–0.31). By contrast, salaried, casual, and self-employed patients showed no significant differences by outcome. Occupation categories showed no statistically significant associations with outcome (all p > 0.1), though most patients in both groups were unemployed (82.7% successful vs. 90.7% unsuccessful). Comorbidity profiles were dominated by HIV co-infection (94.4% of successful vs. 96.3% of unsuccessful patients), with no significant differences by other comorbidities. Social history factors such as smoking, alcohol use, or combined risk behaviours did not differ significantly between outcome groups (all p > 0.2). Similarly, prior drug history, patient category (new, relapse, or retreatment), and type of resistance (mono vs. poly) were not significantly associated with outcome. For DR-TB type, XDR-TB was significantly associated with unsuccessful outcomes: two cases of XDR-TB occurred exclusively in the unsuccessful group (p=0.014, 95% CI: −0.09 to −0.01). Other resistance categories (RR, MDR, Pre-XDR) did not show significant differences.

The distribution of treatment outcomes varied significantly across selected patient characteristics (

Table 1). Gender was associated with treatment outcomes (χ

2=3.98, p=0.046), with males achieving proportionally higher cure rates compared to females. Income status showed a strong association with outcomes (χ

2=15.55, p=0.0037), where patients reporting no income or reliance on social grants had poorer outcomes compared to those with salaried employment. Similarly, DR-TB type was significantly related to outcomes (χ

2=8.58, p=0.0355), with advanced resistance patterns (Pre-XDR/XDR) demonstrating markedly worse treatment success rates compared to RR- and MDR-TB. In contrast, age group, education, occupation, comorbidities (predominantly HIV), social history, previous drug history, patient category, and resistance type (mono vs poly) did not show statistically significant differences in treatment outcomes (all p>0.05).

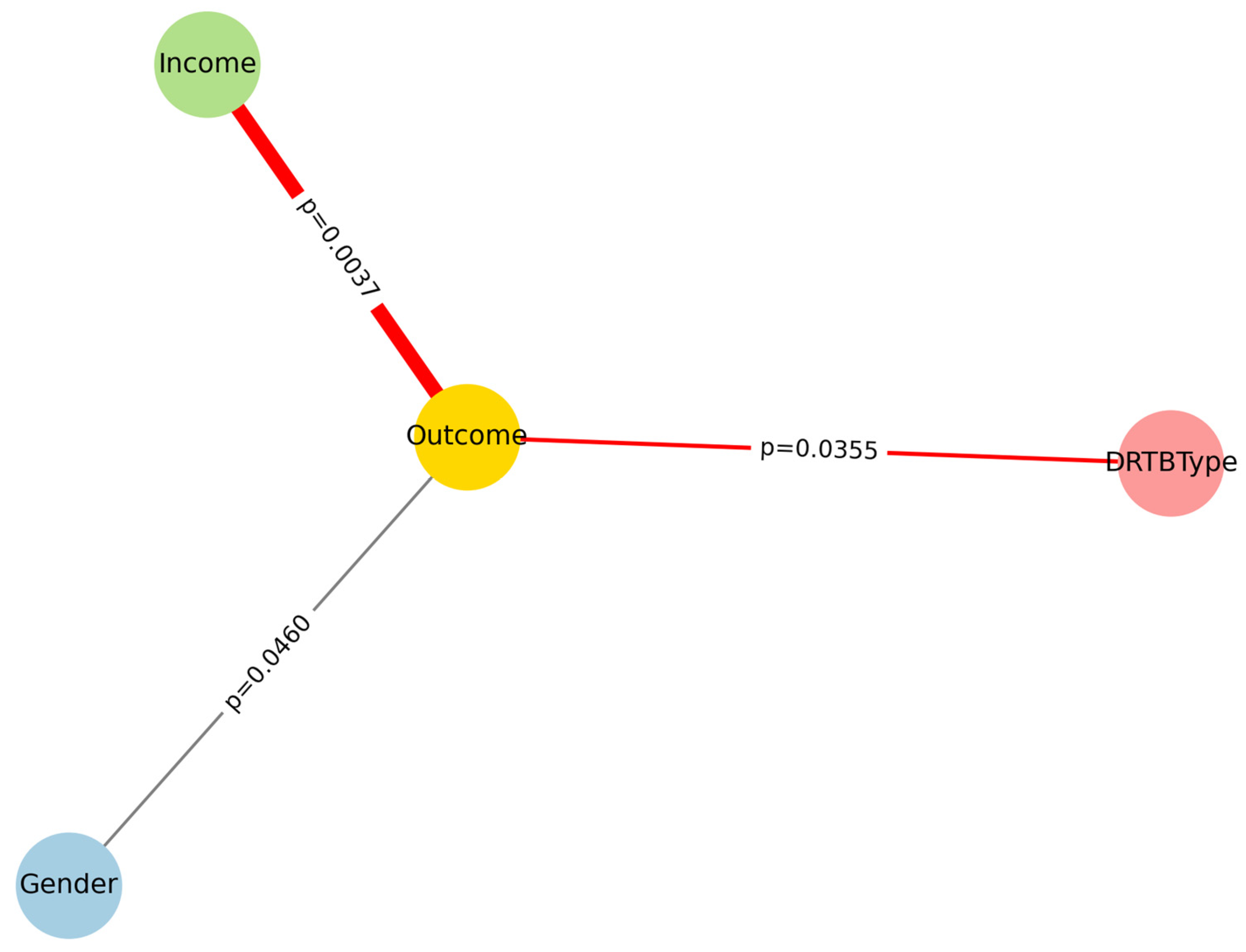

The network in

Figure 1 displays associations between baseline predictors and treatment outcome (Successful vs Unsuccessful). Edge width is proportional to the strength of association (−log10 p), and edge colors indicate directionality: green for predictors overrepresented among successful outcomes, red for predictors overrepresented among unsuccessful outcomes, and grey for neutral associations. This integrated visualization highlights the central role of income, gender, and DR-TB type.

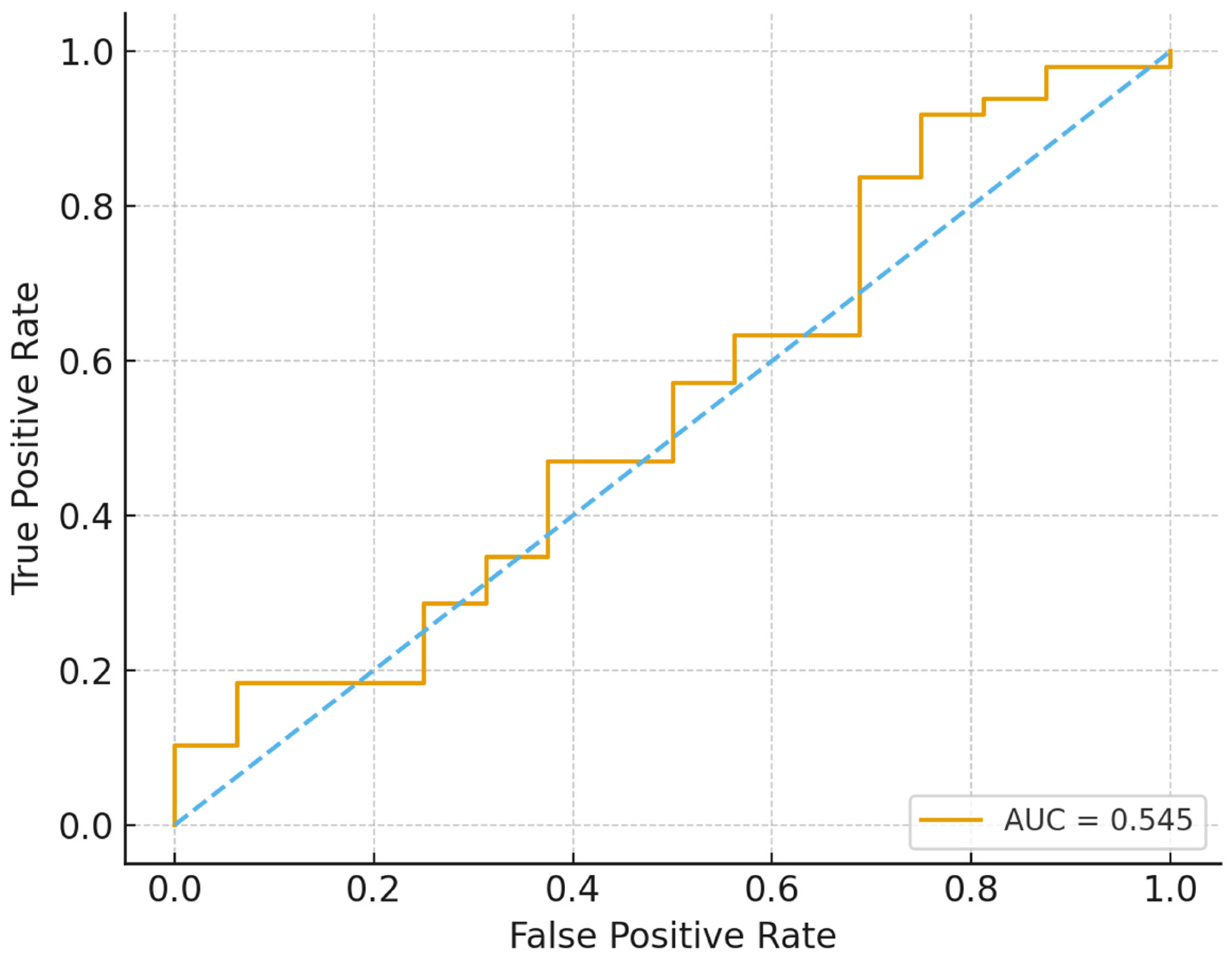

Logistic regression in

Figure 2 provides effect size estimates that reinforced these descriptive findings, although the model’s discriminatory power was modest (AUC ≈ 0.55). Male patients had more than twice the odds of treatment success compared to females (OR = 2.11, 95% CI: 1.05–4.21, p=0.035). Patients with salaried employment demonstrated over threefold higher odds of success compared to those without income (OR = 3.46, 95% CI: 0.39–30.96), though wide confidence intervals reflected limited sample size in some income groups. DR-TB type remained clinically relevant, with Pre-XDR patients having substantially lower odds of success relative to RR-TB (OR = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.05–1.19, p=0.083), while XDR-TB outcomes were so poor that stable model estimates could not be obtained.

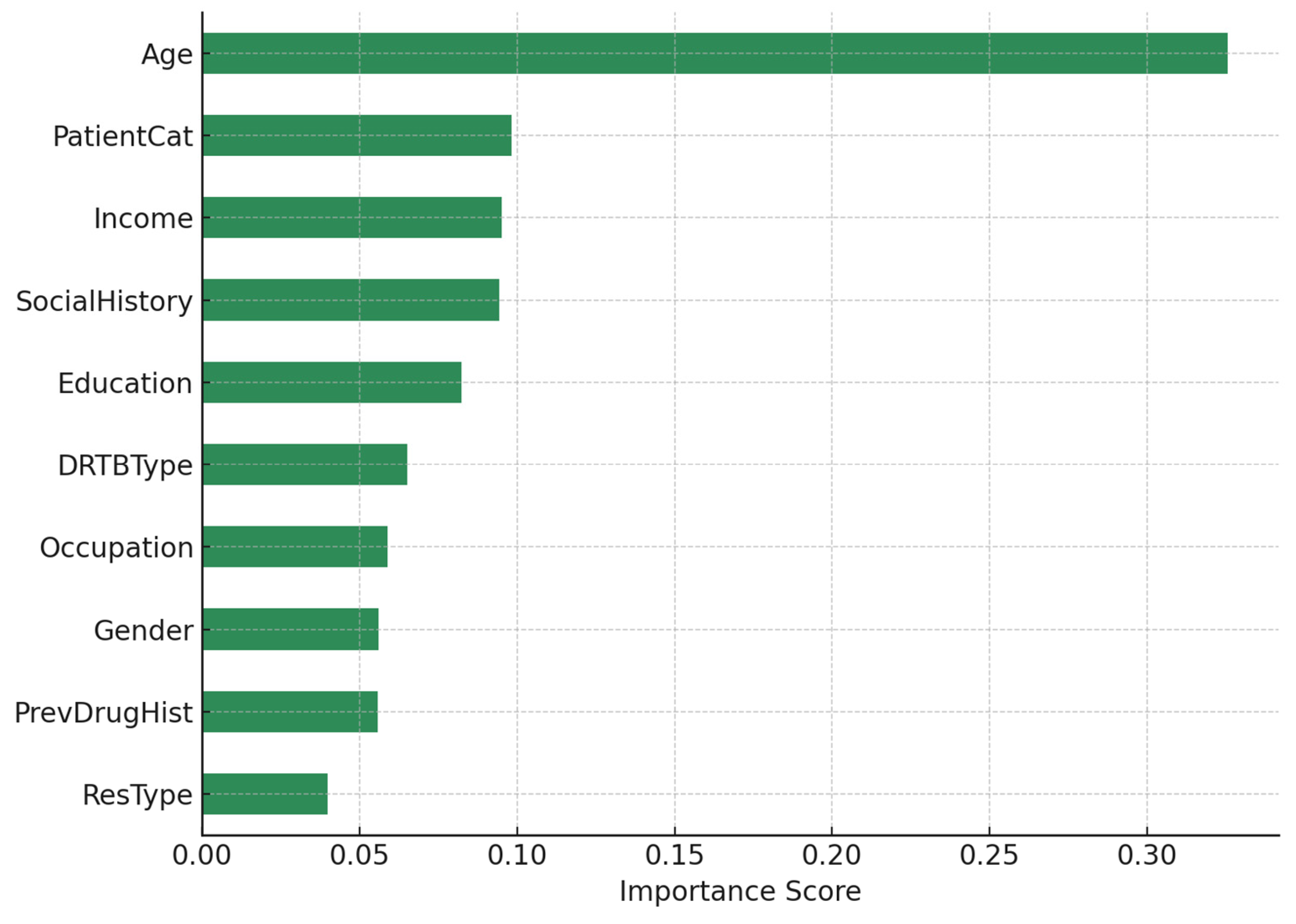

In

Figure 3, Random Forest modelling outperformed logistic regression in predictive performance, achieving higher accuracy, precision, recall, and AUC. Feature importance analysis ranked age as the strongest predictor (importance score = 0.325), with older patients experiencing worse outcomes. Socioeconomic and behavioral factors including patient category (0.098), income (0.095), social history (0.094), and education (0.082) were also highly influential. Clinical determinants such as DR-TB type (0.065) and previous drug history (0.056) contributed to predictive performance, while gender (0.056) played a moderate role. Together, these results indicate that both social determinants and biomedical factors jointly shape treatment outcomes, with socioeconomic vulnerability amplifying the risks associated with advanced resistance.

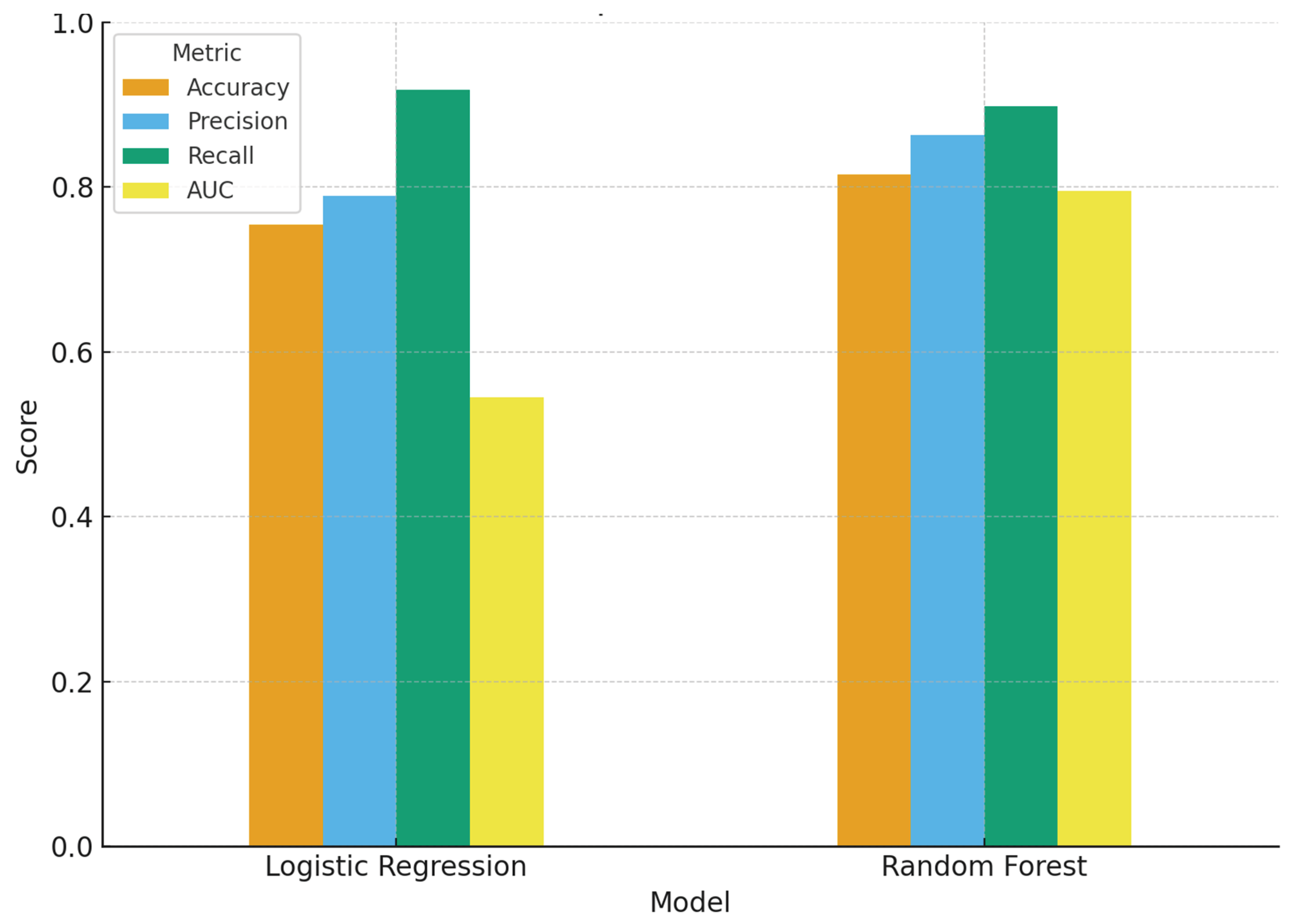

The performance evaluation of the two predictive approaches (

Figure 4 and

Table 2) reveals important differences. Logistic regression demonstrated lower accuracy compared to the random forest, indicating that it produced fewer correct classifications overall. Its precision, representing the proportion of predicted successes that were true successes, was modest, and recall (sensitivity) was also lower, suggesting that the model failed to capture a higher proportion of true successful cases. The AUC was close to 0.5–0.6, reflecting weak discrimination between successful and unsuccessful outcomes and performing only slightly better than chance. While logistic regression provided interpretable odds ratios and quantifiable associations, it proved to be a less effective classifier in this dataset. In contrast, the random forest model consistently outperformed logistic regression across all performance metrics. It achieved higher accuracy, reflecting stronger overall prediction, and improved precision, indicating more reliable classification of treatment successes. Recall was also higher, suggesting that the model captured a greater proportion of true successful outcomes. Importantly, the AUC was substantially higher, highlighting superior ability to discriminate between patients likely to achieve treatment success and those at risk of unsuccessful outcomes. Overall, the random forest emerged as the more robust predictive tool, while logistic regression remained valuable primarily for its interpretability and estimation of odds ratios.

4. Discussion

Our study combined descriptive, regression-based, and machine-learning approaches to identify determinants of treatment outcomes among patients with DR-TB. The triangulation of cross-tabulations, logistic regression, and random forest modelling provides a robust picture of the interplay between clinical and social predictors of success, highlighting both convergent findings and methodological complementarity.

4.1. Treatment Outcomes Across Settings

Our study in the Eastern Cape reported treatment success rates below the WHO target, with both biomedical and socioeconomic factors shaping outcomes. This aligns with findings from Faye et al. [

11], who also observed suboptimal outcomes (65.8% success) among rural Eastern Cape TB patients, largely influenced by TB–HIV co-infection and social determinants. Similarly, Atif et al. [

13] in Pakistan highlighted a poor treatment success rate (32.1%) among XDR-TB patients, with high mortality and loss to follow-up, indicating that DR-TB management remains a global challenge. By contrast, Hayibor et al. [

14] in Ghana reported a higher overall success rate of 88.1%, although outcomes were markedly worse among HIV-positive patients (78.1%), underscoring the consistent role of HIV as a negative prognostic factor.

4.2. Clinical Predictors of Unfavorable Outcomes

Across studies, drug-resistance patterns emerge as central determinants [

15,

16]. Our findings that pre-XDR cases had reduced odds of success echo those of Aaina et al. [

17], who demonstrated poor outcomes among pre-XDR and MDR patients, particularly in older adults and those with comorbidities like diabetes. Atif et al. [

13] similarly emphasized that conventional therapy and adverse drug events predicted failure in XDR-TB cohorts. Hosu et al. [

18] extended this by showing that shorter regimens accelerated sputum conversion and improved outcomes, reinforcing the clinical imperative to optimize regimen choice. Taken together, resistance type consistently drives prognosis, but regimen innovations can mitigate risks.

4.3. Role of HIV and Comorbidities

Our analysis identified HIV status as an influential though context-dependent predictor. This is consistent with [

11,

14], both of whom found significantly worse outcomes in TB–HIV co-infected. Hosu et al. [

19] further demonstrated that comorbidities such as hypertension, obesity, and hearing loss significantly affect outcomes, with obesity paradoxically linked to better prognosis while HIV predicted worse [

19]. This suggests that the clustering of HIV with non-communicable diseases amplifies treatment complexity in high-burden African settings.

4.4. Socioeconomic Determinants and Behavioral Risks

Our study highlights income, gender, and education as strong determinants of treatment outcomes. These findings resonate with Faye et al. [

20], who showed that financial stability and reduced comorbidity burden improved survival among DR-TB patients in rural Eastern Cape. Khan et al. [

21] in India similarly underscored that poor knowledge, unemployment, and limited access to healthcare fuel XDR-TB prevalence. Kostyukova et al. [

22] in Russia added an epidemiological perspective, showing that socio-structural conditions coupled with high rates of MDR/XDR strains complicate control efforts. Together, these studies affirm that social determinants are not peripheral but central to DR-TB trajectories.

4.5. Cross-Tabulation Analyses and Sociodemographic Predictors

Our cross-tabulation analyses revealed significant associations between treatment outcomes and gender, income, and drug-resistance type. Males and patients with stable income were more likely to achieve treatment success, whereas pre-XDR TB was strongly associated with poorer outcomes. These findings align with evidence from Malaysia, where Zaman et al. [

23] identified male sex, lack of formal education, HIV co-infection, and advanced resistance types as independent predictors of unfavourable outcomes (aOR for male sex 2.38; aOR for RR-TB 3.34). Similarly, in China, Liu et al. [

24] reported that low BMI, pre-treatment anaemia, and advanced resistance significantly predicted poor outcomes among elderly RR-TB patients. Together, these studies reinforce the role of sociodemographic vulnerability in shaping prognosis, even after adjusting for clinical factors.

A novel aspect of our findings is the strong association between income stability and treatment success. While this factor is less frequently examined in clinical cohorts, it has been consistently highlighted in health-systems research. For example, Long et al. [

25] showed that despite China’s implementation of case-based TB financing reforms, financial barriers persisted due to hidden costs and the exclusion of patients with comorbidities leaving poorer households disproportionately burdened. Our findings therefore suggest that socioeconomic disadvantage remains a structural barrier to favorable DR-TB outcomes across diverse contexts, underscoring the need to integrate financial protection measures into TB control strategies. In the rural South African context, this highlights the urgency of strengthening social protection mechanisms, aligning TB care with existing grant systems, and exploring clinic-based financial support models to reduce treatment attrition among economically vulnerable patients.

4.6. Predictive Modelling Approaches: Regression and Random Forest

Our study further mapped treatment outcomes among patients with DR-TB and identified key sociodemographic and clinical predictors. Our overall success rate fell below the WHO target of ≥85% and the national average of 70–78%, underscoring persistent gaps in DR-TB control in high-burden, resource-constrained settings. Cross-tabulation analyses revealed significant associations between treatment outcomes and gender, income, and resistance type: males and salaried patients were more likely to achieve success, while patients with pre-XDR TB experienced substantially poorer outcomes. These associations were reinforced by logistic regression, which showed that male sex more than doubled the odds of treatment success (OR = 2.11), salaried income increased success threefold (OR = 3.46), and pre-XDR TB sharply reduced the odds of cure (OR = 0.25). Together, these findings demonstrate that both social position and resistance patterns are critical determinants of prognosis.

Our results are consistent with international evidence highlighting the interplay between clinical severity and social vulnerability. In Malaysia, Zaman et al. [

23] showed that male sex, lack of education, HIV co-infection, and advanced resistance were independent predictors of unfavorable outcomes, while Liu et al. [

24] reported that low BMI, anaemia, and advanced resistance predicted poor prognosis in elderly Chinese patients. Importantly, our study adds to this literature by emphasizing income stability a less commonly examined factor in clinical cohorts but repeatedly flagged in health-systems research. Long et al. [

25] found that despite TB financing reforms in China, hidden costs and exclusions disproportionately burdened poorer households. Our findings echo these concerns, suggesting that financial insecurity undermines adherence and drives attrition, especially in rural settings where unemployment is widespread and out-of-pocket expenses remain high. This reinforces the argument that biomedical interventions alone are insufficient to close the outcome gap; socioeconomic disadvantage remains a structural barrier across diverse contexts.

Methodologically, this study demonstrated the complementary strengths of regression and machine-learning approaches. Logistic regression provided interpretable associations and effect sizes, confirming the protective influence of male gender and salaried income, while identifying pre-XDR TB as a negative prognostic marker. However, the model’s modest discriminatory ability (AUC ≈ 0.55) limited predictive utility. By contrast, the random forest classifier achieved superior performance and highlighted age as the single most important determinant, followed by income, education, social history, and resistance type. These findings underscore that social and behavioral factors weigh as heavily as biomedical indicators in shaping treatment outcomes. They also resonate with recent advances in TB outcomes research: Makabayi-Mugabe et al. [

26] used regression to show community-based DOT improved success in Uganda, while Santosa et al. [

27] employed network analysis to visualize socioeconomic and behavioral barriers to adherence. Our integration of traditional regression with machine learning mirrors this broader trend, combining interpretability with predictive value and offering a richer understanding of risk hierarchies.

Our findings carry clear implications for policy and practice. Interventions must extend beyond regimen optimization to address the social determinants that drive poor outcomes. Expanding social protection measures such as conditional cash transfers, nutritional support, and disability grants could buffer the financial vulnerabilities that undermine adherence and fuel loss to follow-up. Tailored support for high-risk groups, including older adults, women, and socioeconomically disadvantaged patients, should be prioritized through gender-sensitive services that mitigate barriers such as transport costs, caregiving responsibilities, and stigma. At the same time, predictive tools like random forests could be embedded in routine care to flag patients at high risk of failure early, enabling proactive case management. Finally, strengthening community-linked governance, with the active involvement of community health workers and local stakeholders, will be essential to ensure that biomedical innovations are paired with context-sensitive social interventions. Taken together, our findings reinforce the need for holistic, multi-sectoral strategies if South Africa is to close the persistent gaps in DR-TB outcomes.

4.7. Clinical and Regimen-Related Predictors

The association between advanced resistance and poor prognosis in our cohort is consistent with evidence from China, where Liu et al. [

24] demonstrated that patients with pre-XDR and XDR-TB had significantly lower success rates compared to RR-TB cases. In high-income settings, however, the prognostic weight of resistance patterns is being mitigated by the availability of newer regimens. Otto-Knapp et al. [

28] reported that in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, WHO-endorsed regimens such as BPaLM (bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid, moxifloxacin) are now standard, achieving high success in MDR/RR-TB cases. In contrast, resource-limited settings such as ours remain reliant on heterogeneous regimens, where resistance type remains a decisive determinant of outcome. This divergence underscores the importance of tailoring predictive models to local therapeutic realities: while regimen choice dominates in high-resource contexts, socioeconomic and demographic factors remain equally critical in rural South Africa.

4.8. Integrating Social and Clinical Dimensions

Our findings reinforce the need to integrate social determinants into DR-TB predictive models. Zaman et al. [

23] demonstrated that clinical (HIV, resistance type) and demographic (sex, education) variables combine to drive outcomes in Malaysia, while Santosa et al. [

27] highlighted stigma, poverty, and behavioral risks as hidden determinants of non-compliance. By ranking income, education, and gender alongside clinical variables, our study contributes a holistic framework for understanding DR-TB prognosis. Such integration is particularly relevant in rural South Africa, where structural inequities exacerbate biomedical vulnerabilities.

4.9. Strengths and Limitations

This study contributes to the growing literature on DR-TB outcomes by integrating descriptive cross-tabulations, regression modelling, and machine-learning approaches, thereby enhancing both interpretability and predictive value. The use of multiple analytic frameworks enabled triangulation of findings, reducing reliance on any single method and strengthening the robustness of conclusions. A further strength lies in the explicit incorporation of socioeconomic and behavioral factors such as income stability often overlooked in clinical DR-TB cohorts, but highly relevant in rural, resource-constrained settings. The consistency of our results with international evidence further supports their external validity.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The modest sample size reduced statistical power, particularly in XDR-TB subgroups, resulting in wide confidence intervals and unstable regression estimates. The retrospective design and reliance on routine records may have introduced information bias and limited the completeness of socioeconomic variables. Although the random forest model improved predictive accuracy, its outputs are less directly interpretable for policy use, while the modest discrimination of the logistic regression model suggests that unmeasured confounders such as adherence, psychosocial support, and stigma may have influenced outcomes. Finally, the study was conducted in a single high-burden province, which may limit generalizability to other South African or global contexts.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights that DR-TB outcomes in rural South Africa are shaped not only by resistance patterns but also by age, gender, and socioeconomic vulnerability. By combining statistical and machine-learning approaches, we demonstrated the critical role of social determinants such as income stability in influencing treatment success. Addressing these gaps will require integrated strategies that pair biomedical advances with social protection, gender-responsive services, and community-linked governance to achieve sustained improvements in DR-TB control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z.; and M.F.; methodology, T.Z.; and L.M.F.; software, L.M.F.; validation, T.Z., L.M.F., and T.A.; formal analysis, T.Z., L.M.F., and M.F.; investigation, T.Z., L.M.F.; data curation, T.Z., L.M.F., and M.F.; writing original draft preparation, T.Z., L.M.F.; writing review and editing, T.Z., L.M.F., and M.F.; visualization, L.M.F. Supervision, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Walter Sisulu University, Faculty of medicine and health sciences, Department of Laboratory medicine funds were used conduct of this study and the Department of public health took responsibility of paying journal APC fess.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval granted Research Ethics and Biosafety Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of Walter Sisulu University (Ref. No. 171/2025, 09 July 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

No informed consent was required for the study as it involved review of clinical records in the clinics retrospectively following all ethical guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be requested from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge Walter Sisulu University TB Research Group—2025 Honours students for assisting in data collection and Health care professionals in clinics for the guidance in patient clinical records review and data extraction.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TB |

Tuberculosis |

| DR-TB |

Drug resistant tuberculosis |

| RR-TB |

Rifampicin resistant tuberculosis |

| MDR-TB |

Multi drug resistant tuberculosis |

| Pre-XDR-TB |

Pre-extensively drug-resistant |

| XDR-TB |

Extensively drug-resistant |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

References

- WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment—drug-susceptible tuberculosis treatment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Mitnick C, Khan U, Guglielmetti L. SP01 Innovation to guide practice in MDR/RR-TB treatment: efficacy and safety results of the end TB trial. InUnion World Conference on Lung Health 2023.

- Global tuberculosis report 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NCSA 3.0 IGO, ISBN 978-92-4-008385-1.

- Chingonzoh R, Manesen MR, Madlavu MJ, Sopiseka N, Nokwe M, Emwerem M, Musekiwa A, Kuonza LR. Risk factors for mortality among adults registered on the routine drug resistant tuberculosis reporting database in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, 2011 to 2013. PLoS One. 2018 Aug 22;13(8):e0202469.

- Evans D, Sineke T, Schnippel K, Berhanu R, Govathson C, Black A, Long L, Rosen S. Impact of Xpert MTB/RIF and decentralized care on linkage to care and drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment outcomes in Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC health services research. 2018 Dec 17;18(1):973.

- Dlatu N, Faye LM, Apalata T. Outcomes of Treating Tuberculosis Patients with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, and Nutritional Status: The Combined Impact of Triple Challenges in Rural Eastern Cape. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025 Feb 20;22(3):319.

- Kamara RF, Saunders MJ, Sahr F, Losa-Garcia JE, Foray L, Davies G, Wingfield T. Social and health factors associated with adverse treatment outcomes among people with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Sierra Leone: a national, retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Global Health. 2022 Apr 1;10(4):e543-54.

- Dheda K, Makambwa E, Esmail A. The great masquerader: Tuberculosis presenting as community-acquired pneumonia. InSeminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2020 Aug (Vol. 41, No. 04, pp. 592-604). Thieme Medical Publishers.

- Murdoch J, Curran R, van Rensburg AJ, Awotiwon A, Dube A, Bachmann M, Petersen I, Fairall L. Identifying contextual determinants of problems in tuberculosis care provision in South Africa: a theory-generating case study. Infectious diseases of poverty. 2021 Jun 1;10(03):82-94.

- Nidoi J, Muttamba W, Walusimbi S, Imoko JF, Lochoro P, Ictho J, Mugenyi L, Sekibira R, Turyahabwe S, Byaruhanga R, Putoto G. Impact of socio-economic factors on Tuberculosis treatment outcomes in north-eastern Uganda: a mixed methods study. BMC Public Health. 2021 Nov 26;21(1):2167.

- Faye LM, Hosu MC, Iruedo J, Vasaikar S, Nokoyo KA, Tsuro U, Apalata T. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among tuberculosis patients from selected rural eastern cape hospitals: An ambidirectional study. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2023 Jun 9;8(6):315.

- Faye LM, Magwaza C, Dlatu N, Apalata T. Exploring Determinants and Predictive Models of Latent Tuberculosis Infection Outcomes in Rural Areas of the Eastern Cape: A Pilot Comparative Analysis of Logistic Regression and Machine Learning Approaches. Information. 2025 Mar 18;16(3):239.

- Atif M, Mukhtar S, Sarwar S, Naseem M, Malik I, Mushtaq A. Drug resistance patterns, treatment outcomes and factors affecting unfavourable treatment outcomes among extensively drug resistant tuberculosis patients in Pakistan; a multicentre record review. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2022 Apr 1;30(4):462-9.

- Hayibor KM, Bandoh DA, Asante-Poku A, Kenu E. Predictors of Adverse TB Treatment Outcome among TB/HIV Patients Compared with Non--HIV Patients in the Greater Accra Regional Hospital from 2008 to 2016. Tuberculosis research and treatment. 2020;2020(1):1097581.

- Rahbe E, Watier L, Guillemot D, Glaser P, Opatowski L. Determinants of worldwide antibiotic resistance dynamics across drug-bacterium pairs: a multivariable spatial-temporal analysis using ATLAS. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2023 Jul 1;7(7):e547-57.

- Malik B, Bhattacharyya S. Antibiotic drug-resistance as a complex system driven by socio-economic growth and antibiotic misuse. Scientific reports. 2019 Jul 5;9(1):9788.

- Aaina M, Venkatesh K, Usharani B, Anbazhagi M, Rakesh G, Muthuraj M. Risk factors and treatment outcome analysis associated with second-line drug-resistant tuberculosis. Journal of Respiration. 2021 Dec 28;2(1):1-2.

- Hosu MC, Faye LM, Apalata T. Optimizing Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment Outcomes in a High HIV-Burden Setting: A Study of Sputum Conversion and Regimen Efficacy in Rural South Africa. Pathogens. 2025 Apr 30;14(5):441.

- Hosu MC, Faye LM, Apalata T. Comorbidities and Treatment Outcomes in Patients Diagnosed with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Rural Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Diseases. 2024 Nov 19;12(11):296.

- Faye LM, Hosu MC, Apalata T. Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: A Study of Patients’ Characteristics in Selected Healthcare Facilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024 Nov 30;21(12):1594.

- Khan AH, Nagoba BS, Shiromwar SS. A critical review of risk factors influencing the prevalence of extensive drug-resistant tuberculosis in India. The International Journal of Mycobacteriology. 2023 Oct 1;12(4):372-9.

- Kostyukova I, Pasechnik O, Mokrousov I. Epidemiology and drug resistance patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in High-Burden Area in Western Siberia, Russia. Microorganisms. 2023 Feb 8;11(2):425.

- Zaman MF, Husain NR, Sidek MY, Bakar ZA. Determinants of unfavourable treatment outcomes of drug-resistant tuberculosis cases in Malaysia: a case–control study. BMJ open. 2025 Feb 1;15(2):e093391.

- Liu H, Zou L, Yu J, Zhu Q, Yang S, Kang W, Ma J, Chen Q, Shi Z, Tang X, Liang L. Treatment outcomes and associated influencing factors among elderly patients with rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis: a multicenter, retrospective, cohort study in China. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2025 Sep 1;25(1):1086.

- Long Q, Jiang W, Dong D, Chen J, Xiang L, Li Q, Huang F, Lucas H, Tang S. A new financing model for tuberculosis (TB) care in China: challenges of policy development and lessons learned from the implementation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Feb;17(4):1400.

- Makabayi-Mugabe R, Musaazi J, Zawedde-Muyanja S, Kizito E, Fatta K, Namwanje-Kaweesi H, Turyahabwe S, Nkolo A. Community-based directly observed therapy is effective and results in better treatment outcomes for patients with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in Uganda. BMC Health Services Research. 2023 Nov 13;23(1):1248.

- Santosa A, Juniarti N, Pahria T, Susanti RD. Integrating narrative and bibliometric approaches to examine factors and impacts of tuberculosis treatment non-compliance. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine. 2025 Feb 1;20(1):1016.

- Otto-Knapp R, Bauer T, Brinkmann F, Feiterna-Sperling C, Friesen I, Geerdes-Fenge H, Hartmann P, Häcker B, Heyckendorf J, Kuhns M, Lange C. Treatment of MDR, pre-XDR, XDR, and rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis or in case of intolerance to at least rifampicin in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. Respiration. 2024 Sep 3;103(9):593-600.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).