Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

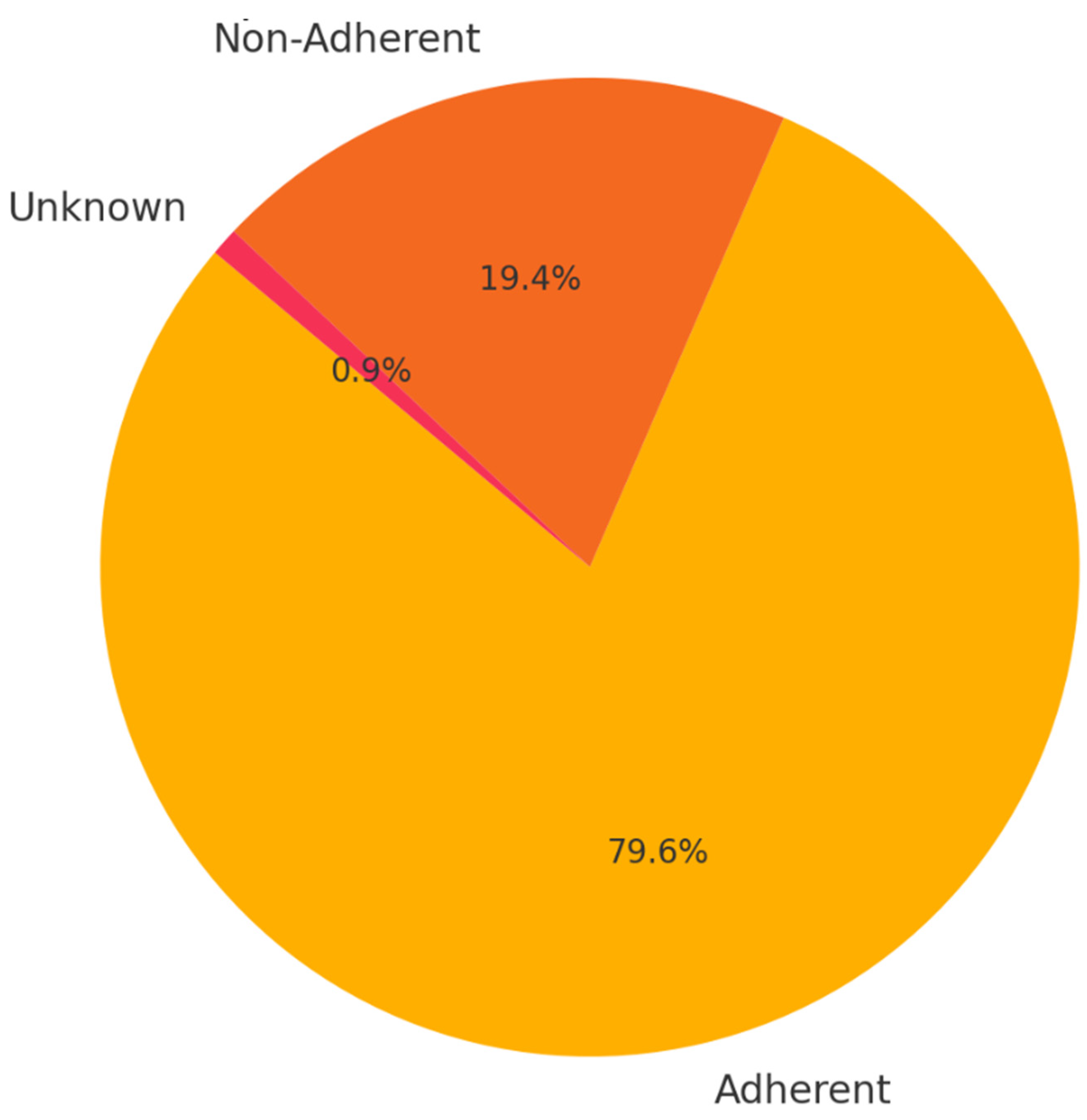

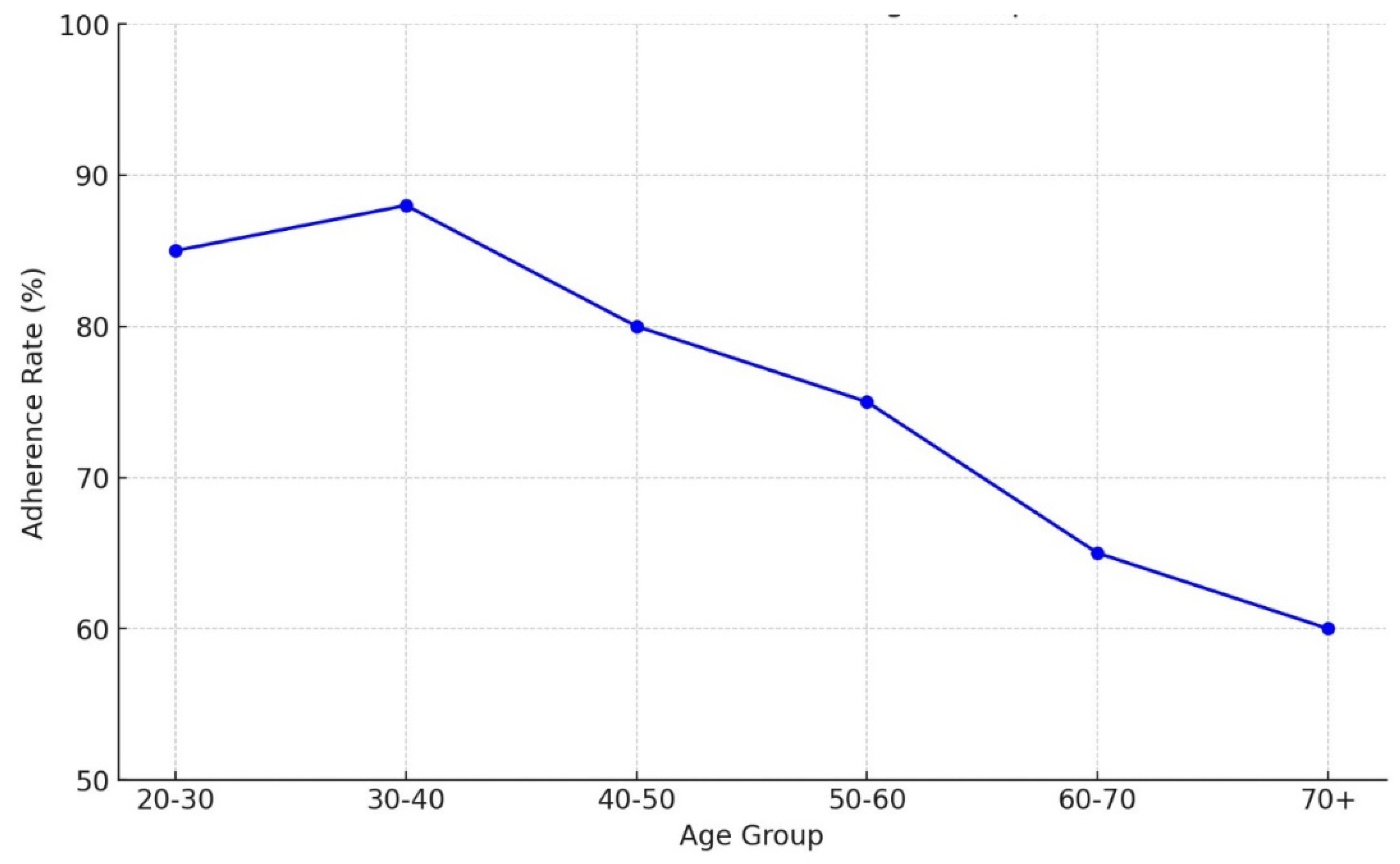

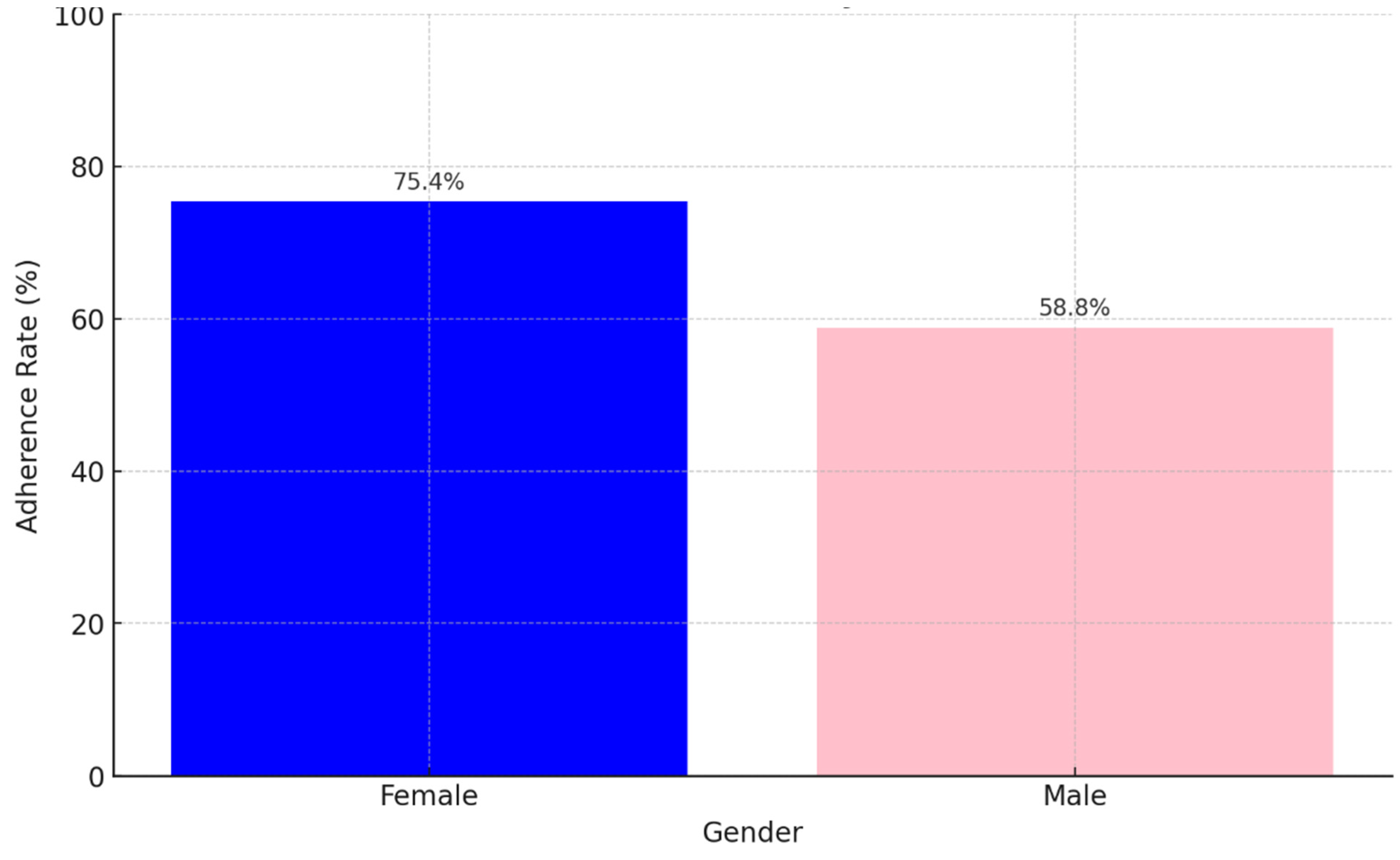

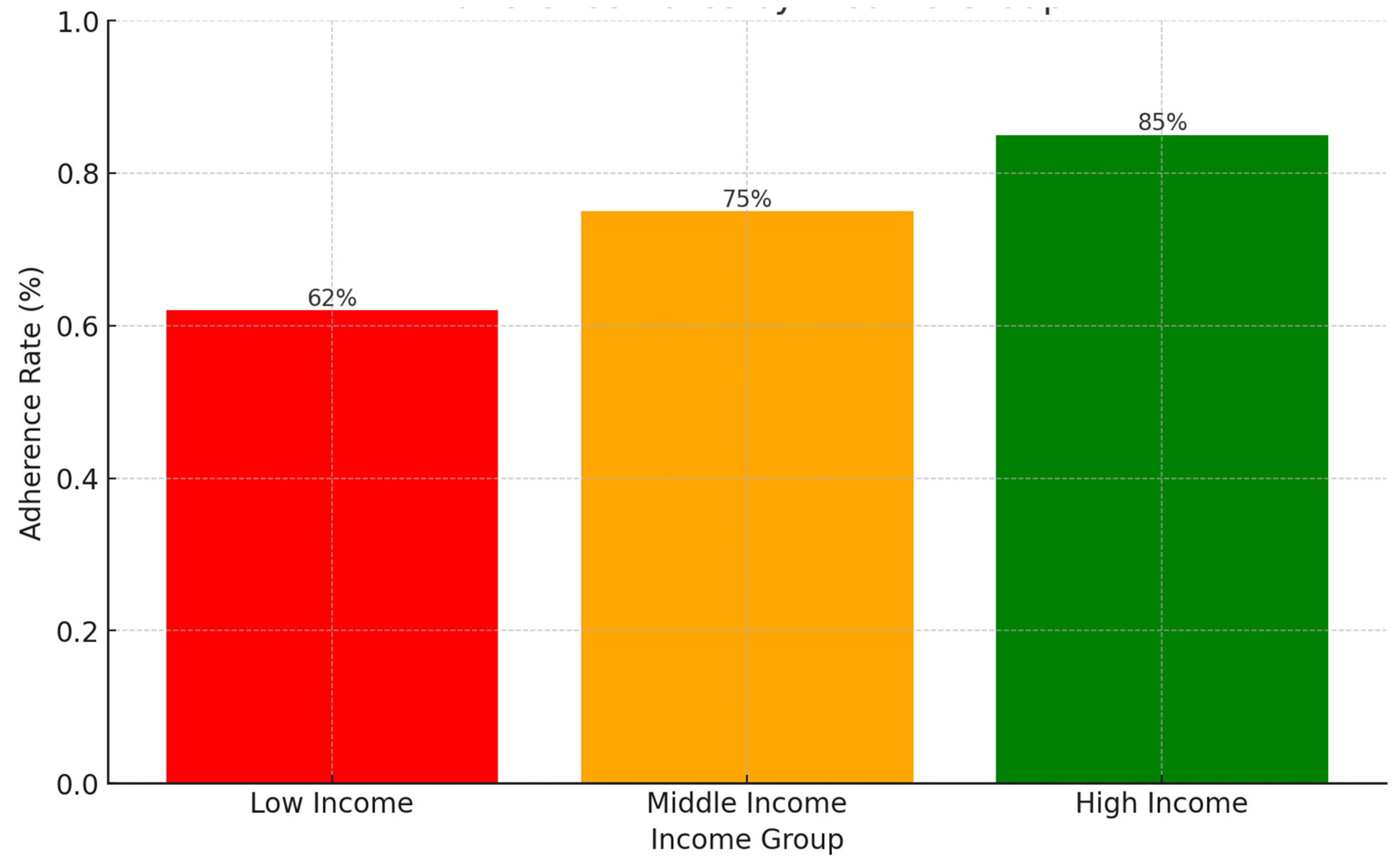

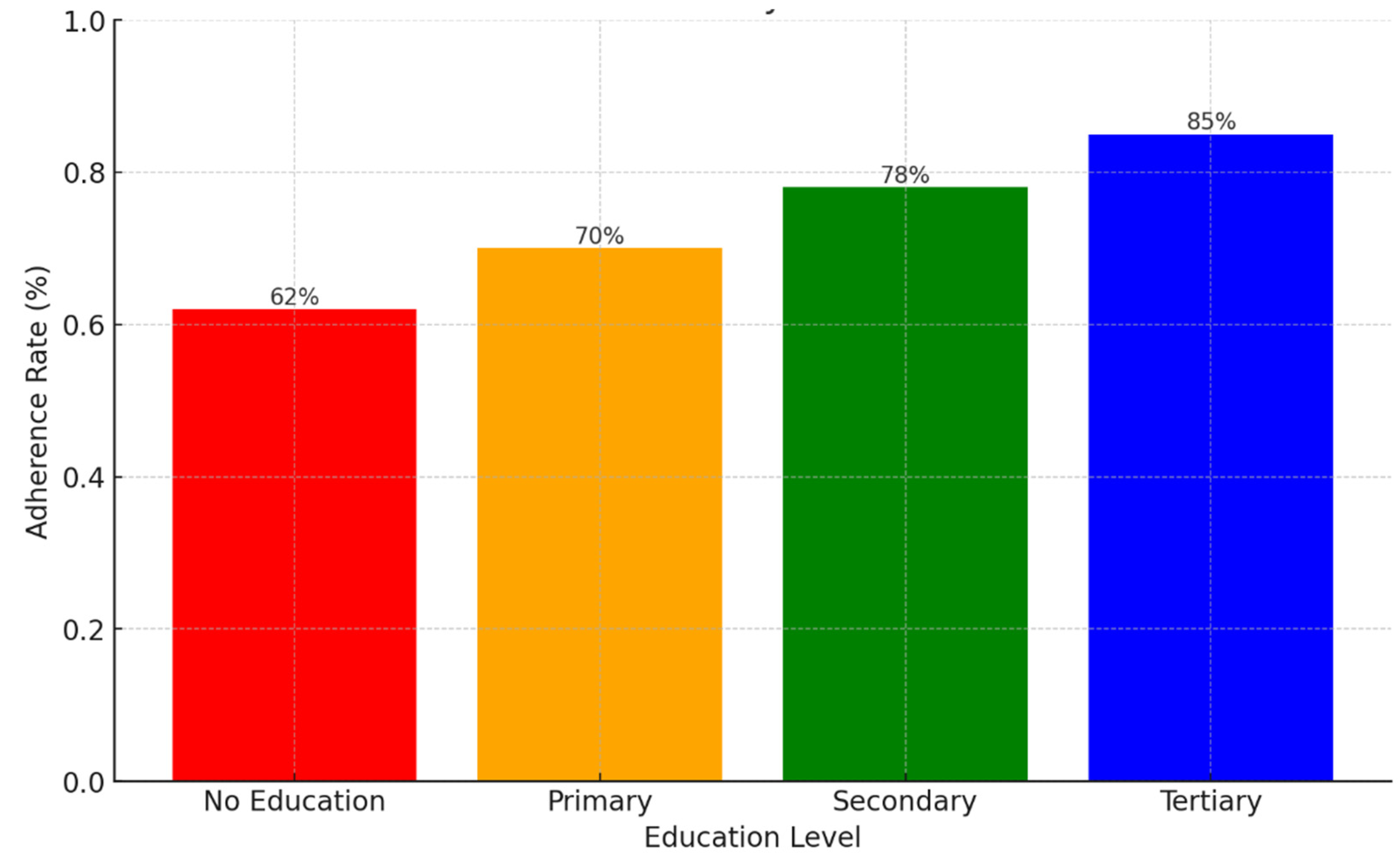

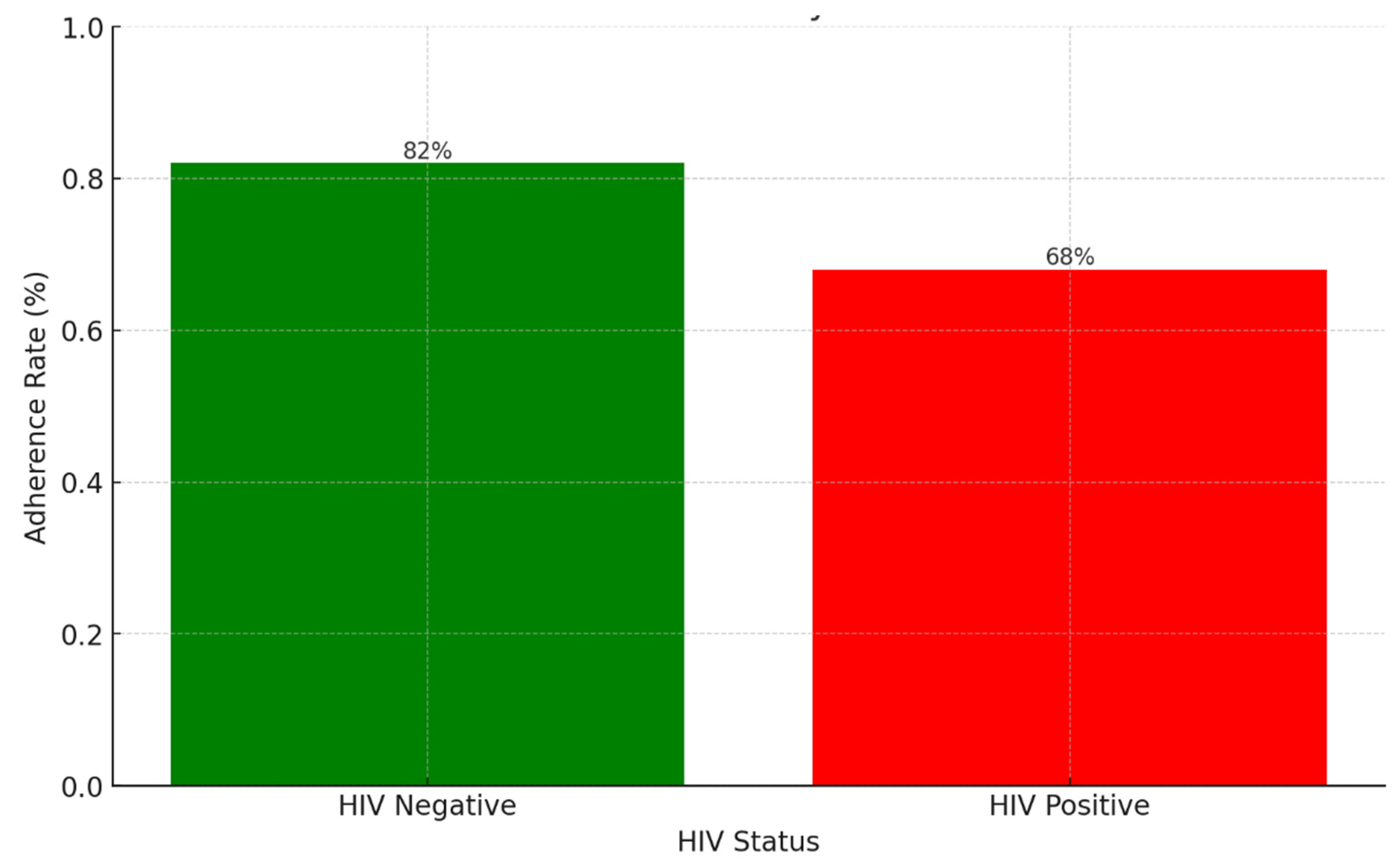

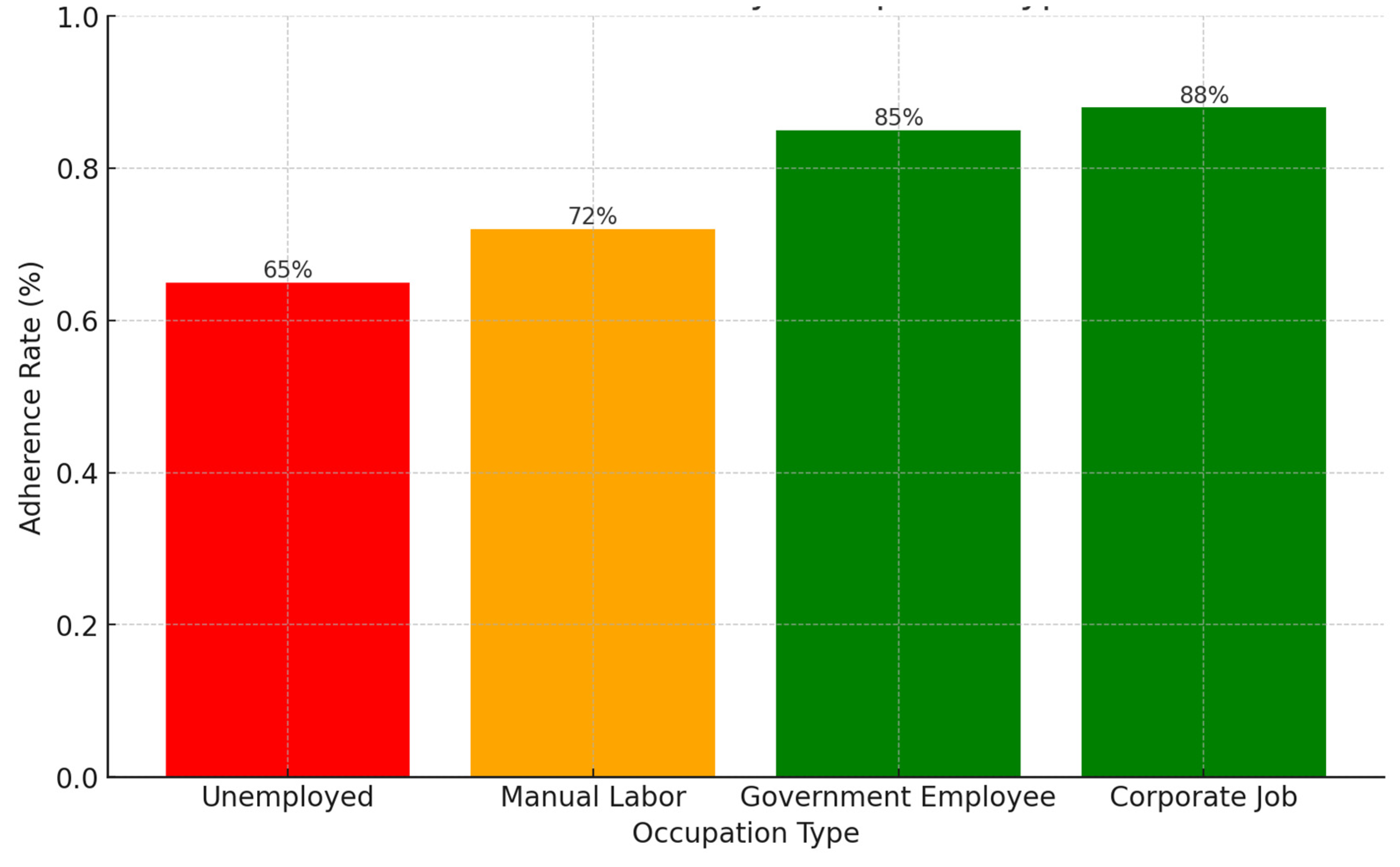

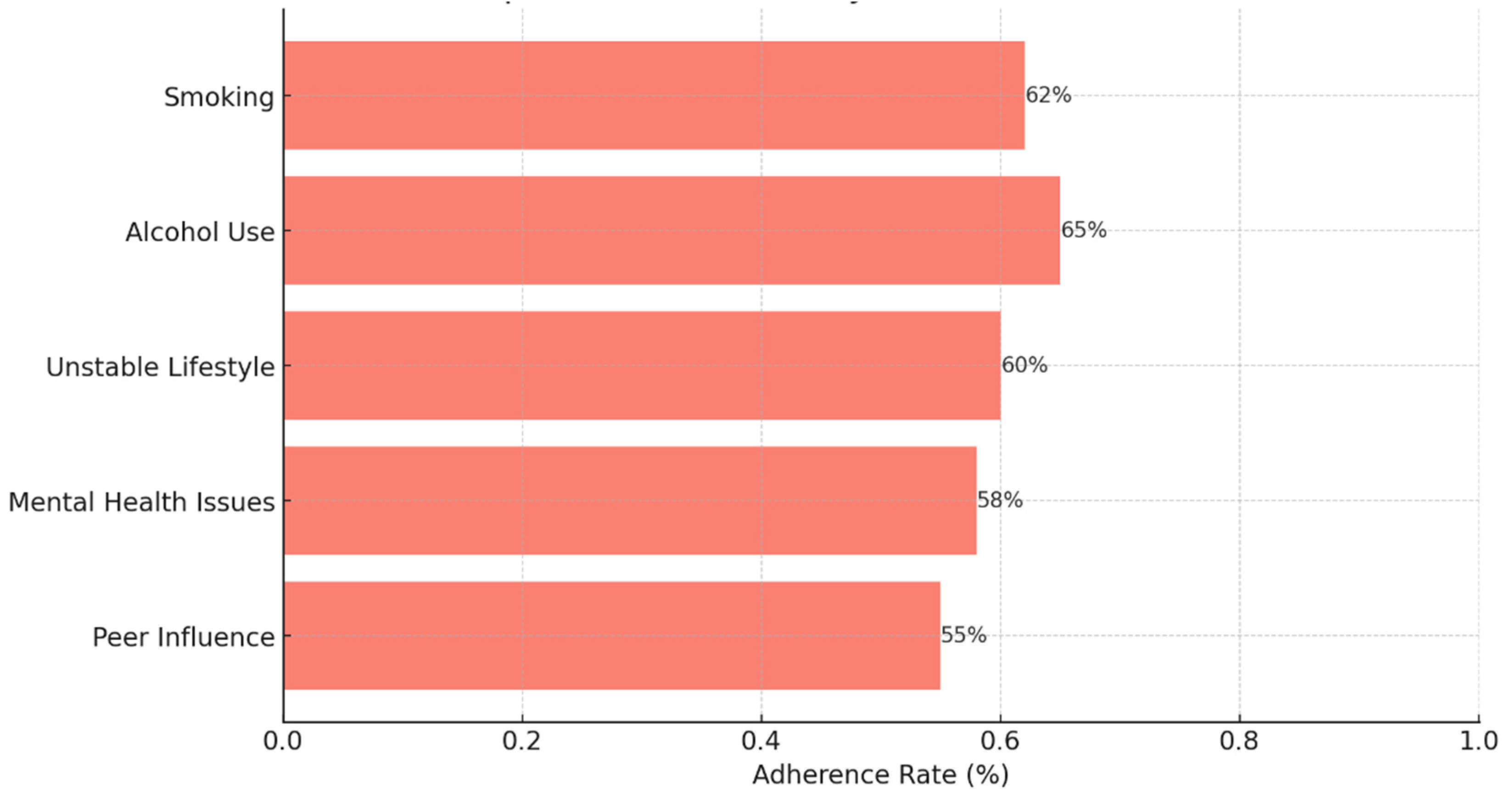

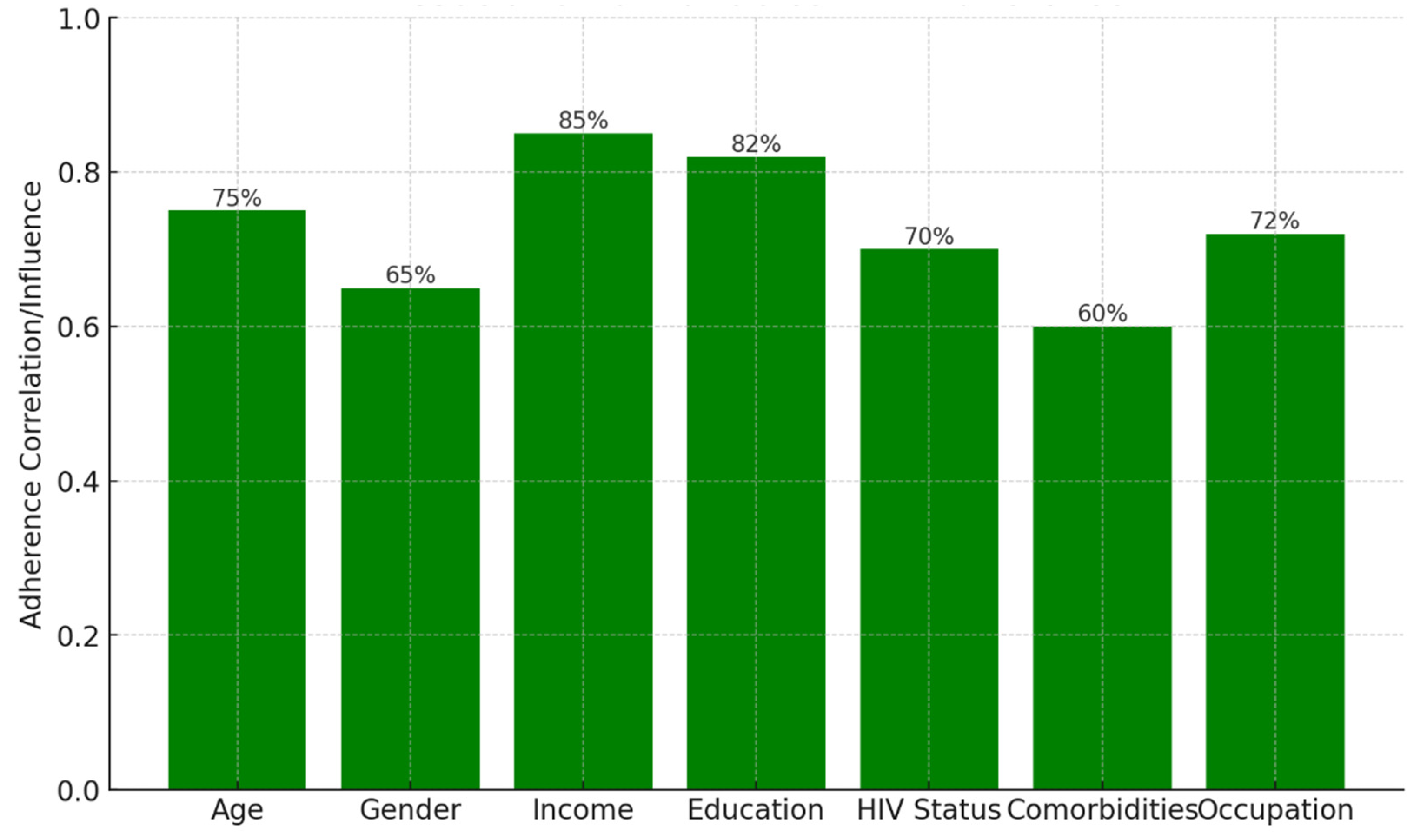

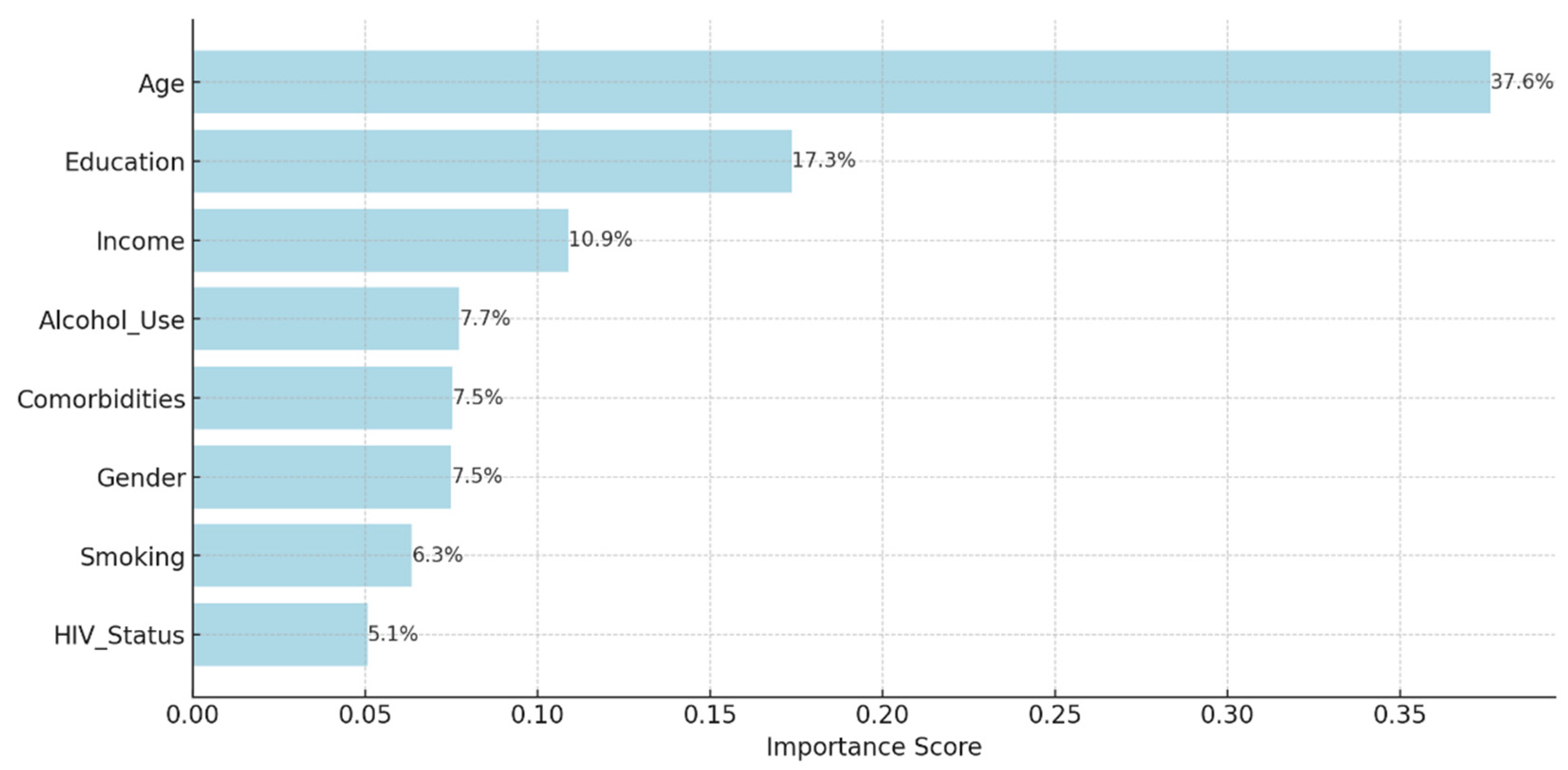

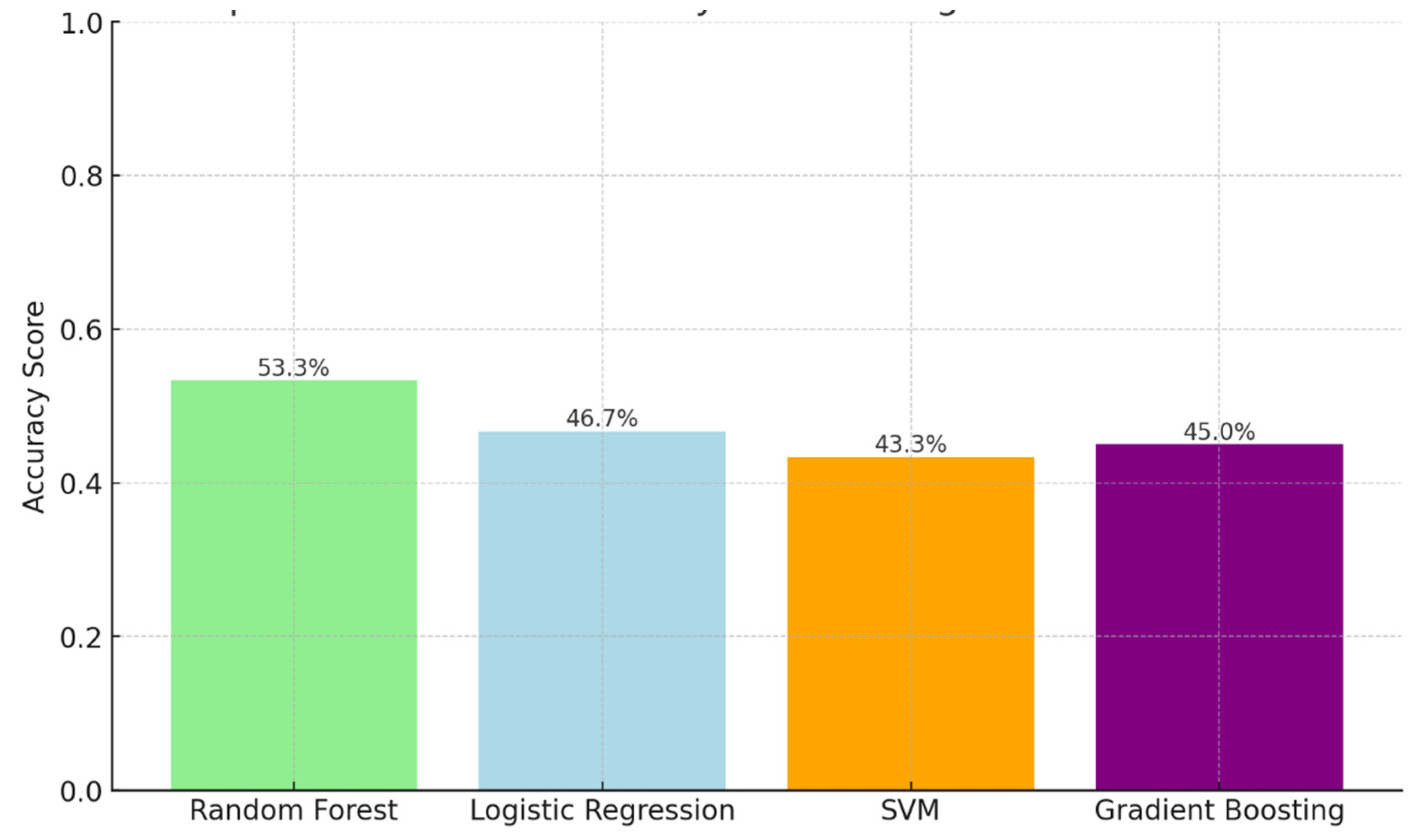

Background: Drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) is a formidable challenge to global health. Patients are compelled to adhere to intricate medication regimens over extended periods, and any failure to comply with these treatment protocols can lead to treatment failure, increased mortality rates, and a heightened risk of developing further drug resistance. This study identifies the key factors that influence treatment adherence among patients with DR-TB. Furthermore, it rigorously evaluates the predictive accuracy of machine learning models in assessing treatment adherence, with a strong focus on socioeconomic, demographic, and clinical factors. Methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients with DR-TB in rural Eastern Cape. Data were collected from medical records. Four different models were developed and tested to evaluate their effectiveness in predicting treatment adherence: Random Forest, Logistic regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Gradient Boosting. Results: The Random Forest model achieved an accuracy of 53.3% in predicting treatment adherence. An analysis of feature importance indicated that age, income, education, social history, patient category, and comorbidities were the most significant factors influencing adherence. Patients with higher incomes, higher levels of education, and fewer comorbidities were more likely to follow their treatment plans. Conclusion: Socioeconomic and clinical factors, such as income, education level, and the presence of comorbidities, significantly influence adherence to DR-TB treatment. These findings indicate that machine-learning models, particularly Random Forest algorithms, can effectively assist in clinical decision-making by identifying patients who may be at risk of not adhering to their treatment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Operational Definition

2.2.1. Treatment Adherence

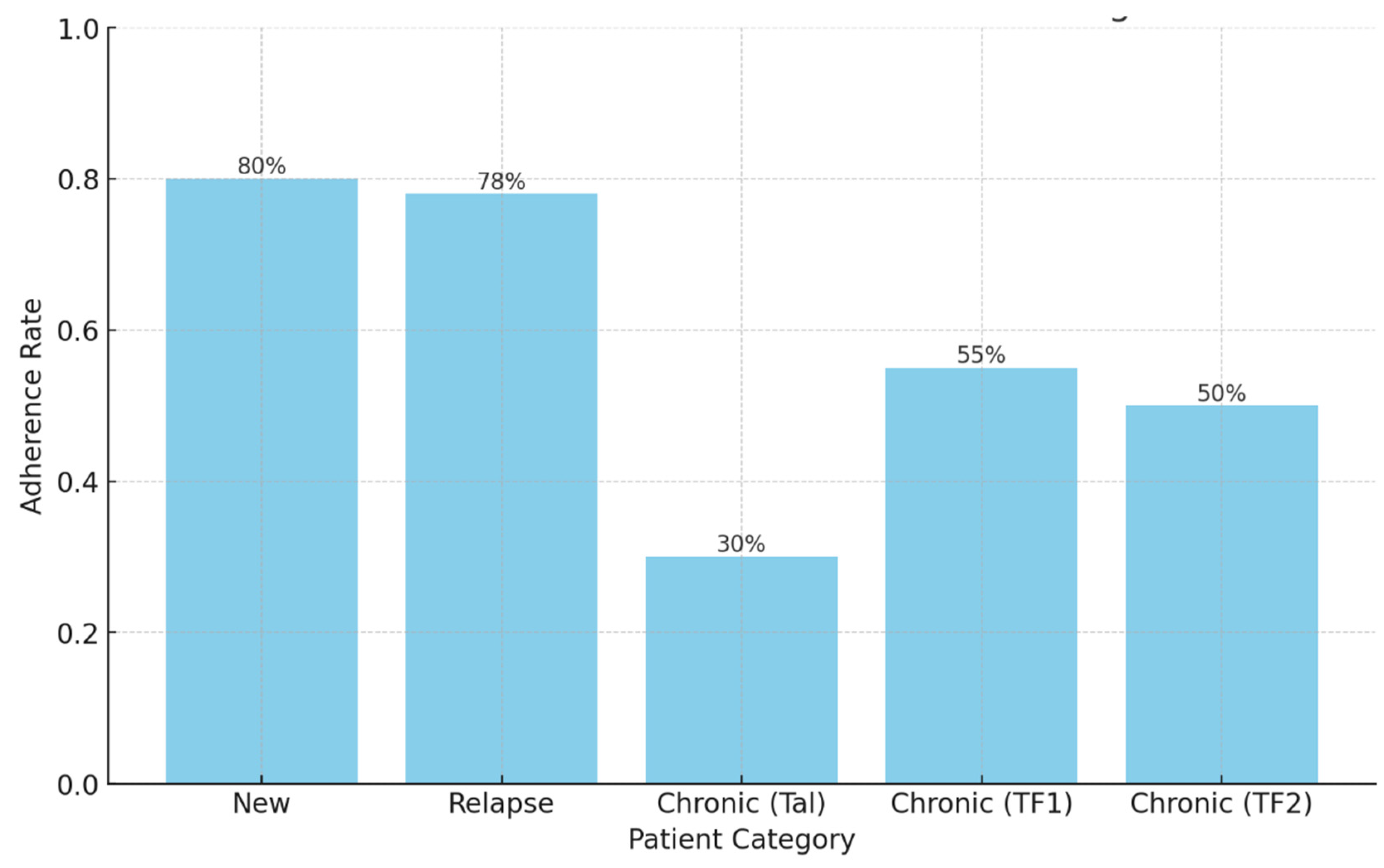

2.2.2. New patients are patients who have never been treated for TB or have taken anti-TB medications for less than 4 weeks.

2.2.3. Relapse patients are patients who were previously treated for TB, were declared cured or completed treatment at the end of their most recent course of treatment, and are now diagnosed with a recurrent episode of TB (either a true relapse or a new episode of TB caused by reinfection).

2.2.4. TAL These are patients previously treated for TB and declared lost to follow-up (LTFU) at the end of their most recent course of treatment.2.2.5. TF1 are those patients who have previously been treated for TB with first-line drugs such as isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin and whose treatment failed at the end of their most recent course of treatment.2.2.6. TF2 are those who have previously been treated for DR-TB with second-line drugs such as bedaquiline, linezolid, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, clofazimine, cycloserine, para-aminosalicylic acid, propylthiouracil, and amikacin and whose treatment failed at the end of their most recent course of treatment.

2.2.5. TF1 are those patients who have previously been treated for TB with first-line drugs such as isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin and whose treatment failed at the end of their most recent course of treatment.2.2.6. TF2 are those who have previously been treated for DR-TB with second-line drugs such as bedaquiline, linezolid, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, clofazimine, cycloserine, para-aminosalicylic acid, propylthiouracil, and amikacin and whose treatment failed at the end of their most recent course of treatment.

2.2.6. TF2 are those who have previously been treated for DR-TB with second-line drugs such as bedaquiline, linezolid, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, clofazimine, cycloserine, para-aminosalicylic acid, propylthiouracil, and amikacin and whose treatment failed at the end of their most recent course of treatment.

2.3. Model Development

2.4. Training the Model

2.5. Evaluating Feature Importance

2.6. Result Interpretation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bea, S.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.H.; Jang, S.H.; Son, H.; Kwon, J.W.; Shin, J.Y. Adherence and Associated Factors of Treatment Regimen in Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis Patients. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Mar 15;12:625078. [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, C. R.; Jr.; Barry, C. E.; 3rd, Lange, C. Treatment of tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med., 2015, 373 (22), 2149–2160. [CrossRef]

- Furin, J.; Cox, H.; Pai, M. Tuberculosis. Lancet, 2019, 393 (10181), 1642–1656. [CrossRef]

- Alipanah, N.; Jarlsberg, L.; Miller, C.; Linh, N. N.; Falzon, D.; Jaramillo, E.; et al. Adherence interventions and outcomes of tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials and observational studies. PLoS Med. 2018, 15 (7), e1002595. [CrossRef]

- Pradipta, I. S. ; Idrus, L. R. ; Probandari, A. ; Lestari, B. W. ; Diantini, A. ; Alffenaar, J. W. C. ; et al. Barriers and strategies to successful tuberculosis treatment in a high-burden tuberculosis setting: a qualitative study from the patient’s perspective. BMC Public Health, 2021, 21, 1903–1912. [CrossRef]

- Pradipta, I. S.; Idrus, L. R. ; Probandari, A. ; Puspitasari, I. M. ; Santoso, P. ; Alffenaar, J.W. C., et al. Barriers to optimal tuberculosis treatment services at community health centers: a qualitative study from a high prevalent tuberculosis country. Front. Pharmacol.2022a, 13, 857783. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.Q.; Wang, J.; Sam, N. B.; Luo, J.; Liu, J.; and Pan, H.F. Factors associated with non-adherence for prescribed treatment in 201 patients with multidrug-resistant and rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis in Anhui province, China. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res.2022, 28, e935334. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: WHO; 2003. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42682. (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- 9. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis: Module 4: Treatment: Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis Treatment. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240048126 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Mekonnen, H.S.; Azagew, A.W. Non-adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment, reasons and associated factors among TB patients attending at Gondar town health centers, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 691.

- Rossetto, M. ; Brand, É.M. ; Rodrigues, R.M. ; Serrant, L. ; Teixeira, L.B. Factors associated with hospitalization and death among TB/HIV co-infected persons in Porto Alegre, Brazil. PLoS One. 2019 Jan 2;14(1):e0209174.

- Sinshaw, Y.; Alemu, S.; Fekadu, A.; Gizachew, M. Successful TB treatment outcome and its associated factors among TB/HIV co-infected patients attending Gondar University Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: an institution based cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017 Dec;17(1):132.

- Kimeu, M. ; Burmen, B. ; Audi, B. ; Adega, A.; Owuor, K.; Arodi ,S.; et al. The relationship between adherence to clinic appointments and year-one mortality for newly enrolled HIV infected patients at a regional referral hospital in Western Kenya, January 2011-December 2012. AIDS care. 2016 Apr 2;28(4):409–15.

- Ayele, A.A.; Asrade Atnafie, S.; Balcha, D.D.; Weredekal, A.T.; Woldegiorgis, B.A.; Wotte, M.M.; Gebresillasie, B.M. Self-reported adherence and associated factors to isoniazid preventive therapy for latent tuberculosis among people living with HIV/AIDS at health centers in Gondar town, North West Ethiopia. Patient Prefer. Adher. 2017, 11, 743–749.

- Shamu, S.; Slabbert, J.; Guloba, G.; Blom, D.; Khupakonke, S.; Masihleho, N.; Kamera, J.; Johnson, S.; Farirai, T.; Nkhwashu, N. Linkage to care of HIV positive clients in a community-based HIV counselling and testing programme: a success story of non-governmental organisations in a South African district. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210826. [CrossRef]

- Hosu, M.C.; Faye, L.M.; Apalata, T. Comorbidities and Treatment Outcomes in Patients Diagnosed with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Rural Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Diseases 2024, 12, 296. [CrossRef]

- Akanbi, K.; Ajayi, I.; Fayemiwo, S.; Gidado, S.; Oladimeji, A.; Nsubuga, P. Predictors of tuberculosis treatment success among TB-HIVco-infected patients attending major tuberculosis treatment sites in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;32(Suppl 1):7. [CrossRef]

- Samuels, J.P.; Sood, A.; Campbell, J.R.; Ahmad Khan, F.; Johnston, J.C. Comorbidities and treatment outcomes in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):4980. [CrossRef]

- Gachara, G.; Mavhandu, L. G.; Rogawski, E. T.; Manhaeve, C.; Bessong P.O. Evaluating adherence to antiretroviral therapy using pharmacy refill records in a rural treatment site in South Africa. AIDS Res. Treat. 2017, 5456219. [CrossRef]

- Navasardyan, I.; Miwalian, R.; Petrosyan, A.; Yeganyan, S.; Venkataraman, V. HIV-TB Coinfection: Current Therapeutic Approaches and Drug Interactions. Viruses. 2024 Feb 21;16(3):321. [CrossRef]

- Tibble, H.; Flook, M.; Sheikh, A.; Tsanas, A.; Horne, R.; Vrijens, B.; De Geest, S.; Stagg, H.R. Measuring and reporting treatment adherence: What can we learn by comparing two respiratory conditions? British J Clin. Pharmacol, 2021, 87(3), 825-836.

- Thamineni, R.; Peraman, R.; Chenniah, J.; Meka, G.; Munagala, A.K.; Mahalingam, V.T.; Ganesan, R.M. Level of adherence to anti-tubercular treatment among drug-sensitive tuberculosis patients on a newly introduced daily dose regimen in South India: A cross-sectional study. Trop. Med. Int. Health, 2022, 27(11), 1013-1023.

- Vernon, A.; Fielding, K.; Savic, R.; Dodd, L.; Nahid, P. The importance of adherence in tuberculosis treatment clinical trials and its relevance in explanatory and pragmatic trials. PLoS Med, 2019, 16(12), e1002884.

- Yin, X.; Tu, X.; Tong, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, Y.; Cao, S.; Fan, H.; Wang, F.; Gong, Y.; Yin, P.; Lu, Z. Development and validation of a tuberculosis medication adherence scale. PLoS One, 2012, 7(12), e50328. [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Horne, R.; Hankins, M.; Chisari, C. The medication adherence report scale: a measurement tool for eliciting patients’ reports of nonadherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020; 86: 1281–1288. [CrossRef]

- Agresti, A.; & Finlay, B. Statistical Methods for the Social Sciences, 2014, (4th Edition). Pearson Education.

- Mugusi, F.M. ; Mehta, S. ; Villamor, E. et al. Factors associated with mortality in HIV-infected and uninfected patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Public Health 9, 409, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Gale, C. P. ; et al. "Trends in hospital treatments, including revascularisation, following acute myocardial infarction, 2003–2010: a multilevel and relative survival analysis for the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR)." Heart 100.7.2014: 582-589.

- Schaffer, A.L.; Buckley, N.A.; Pearson, S.A. Who benefits from fixed-dose combinations? Two-year statin adherence trajectories in initiators of combined amlodipine/atorvastatin therapy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26 (12):1465-73.

- Subbaraman, R.; Thomas, B.E.; Kumar, J.V.; Lubeck-Schricker, M.; Khandewale, A.; Thies, W., Eliasziw, M.; Mayer, K.H.; Haberer, J.E. Measuring tuberculosis medication adherence: a comparison of multiple approaches in relation to urine isoniazid metabolite testing within a cohort study in India. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8(11), ofab532).

- Charalambous, S.; Maraba, N.; Jennings, L.; Rabothata, I.; Cogill, D.; Mukora, R.; Hippner, P.; Naidoo, P.; Xaba, N.; Mchunu, L.; Velen, K. Treatment adherence and clinical outcomes amongst in people with drug-susceptible tuberculosis using medication monitor and differentiated care approach compared with standard of care in South Africa: a cluster randomized trial. eClinicalMedicine, 2024, 75, 102745.

- Krasniqi, S.; Jakupi, A.; Daci, A.; Tigani, B.; Jupolli-Krasniqi, N.; Pira, M.; Zhjeqi, V.; Neziri, B. Tuberculosis treatment adherence of patients in Kosovo. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2017(1), 4850324.

- Karumbi, J.; Garner, P. Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 (5), CD003343. [CrossRef]

- Woimo, T. T.; Yimer, W. K.; Bati, T.; and Gesesew, H. A. The prevalence and factors associated for anti-tuberculosis treatment non-adherence among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in public health care facilities in South Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 2017, 17 (1), 269–310. [CrossRef]

- Lemma T.L.; Ersido T.; Beyene H.T.; Shiferaw A.A. Non-adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment and associated factors among TB patients in public health facilities of Hossana town, Southern Ethiopia, 2022. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1360351. [CrossRef]

- Freire, I.L.S.; dos Santos, F.R.; de Menezes, L.C.C.; de Medeiros, A.B.; de Lima Enfermeira, R.F.; and da Silva, B.C.O. Adherence of elderly people to tuberculosis treatment. Revista de Pesquisa, Cuidado é Fundamental Online, 2019, 11(3), 555-559.

- Mantarro, S.; Capogrosso-Sansone, A.; Tuccori, M.; Blandizzi, C.; Montagnani, S.; Convertino, I.; Antonioli, L.; Fornai, M.; Cricelli, I.; Pecchioli, S.; Cricelli, C. Allopurinol adherence among patients with gout: an Italian general practice database study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2015, 69 (7), 757–765. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.; Levy, G. D.; Wu, Y. L.; Zheng, C.; Koblick, R.; Cheetham, T. C. Patient and clinical characteristics associated with gout flares in an integrated healthcare system. Rheumatol. Int. 2015, 35 (11), 1799–1807. [CrossRef]

- Chang, T. E.; Park, S.; Yang, Q.; Loustalot, F.; Butler, J.; Ritchey, M. D. Association between long-term adherence to class-I recommended medications and risk for potentially preventable heart failure hospitalizations among younger adults. PLoS One, 2019, 14 (9), e0222868. [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.T.; Sajith, M.; Bansode, M.P. Assessment of factors associated with low adherence to pharmacotherapy in elderly patients. J Young Pharmacists, 2017, 9(2), 272.

- Alumkulova, G.; Hazoyan, A.; Zhdanova, E.; Kuznetsova, Y.; Tripathy, J. P.; Sargsyan, A.; & Ortuño-Gutiérrez, N. Discharge outcomes of severely sick patients hospitalized with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, comorbidities, and serious adverse events in Kyrgyz republic, 2020–2022. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 2023, 8(7), 338. [CrossRef]

- Gebreweld, F.H.; Kifle, M.M.; Gebremicheal, F.E.; Simel, L.L.; Gezae, M.M.; Ghebreyesus, S.S.; Mengsteab, Y.T.; Wahd, N.G. Factors influencing adherence to tuberculosis treatment in Asmara, Eritrea: a qualitative study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2018 Jan 5;37(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.M.; Dodd, P.J.; Grant, A.D.; Fielding, K.L.; Churchyard, G.J.; White, R.G. Tuberculosis prevention in South Africa. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 7;10(4):e0122514. [CrossRef]

- Nieuwlaat, R.; Wilczynski, N.; Navarro, T.; Hobson, N.; Jeffery, R.; Keepanasseril, A.; Agoritsas, T.; Mistry, N.; Iorio, A.; Jack, S.; Sivaramalingam, B.; Iserman, E.; Mustafa, R.A.; Jedraszewski, D.; Cotoi, C.; Haynes, R.B. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Nov 20; 2014(11):CD000011. [CrossRef]

- Baryakova, T.H.; Pogostin, B.H.; Langer, R.; McHugh, K.J. Overcoming barriers to patient adherence: the case for developing innovative drug delivery systems. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023 May;22(5):387-409. Epub 2023 Mar 27. [CrossRef]

- Kvarnström, K.; Westerholm, A.; Airaksinen, M.; Liira, H. Factors Contributing to Medication Adherence in Patients with a Chronic Condition: A Scoping Review of Qualitative Research. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Jul 20;13 (7):1100. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Saxena, D.; Raval, D.; Halkarni, N.; Doshi, R. ; Joshi, M. ; et al. Tuberculosis monitoring encouragement adherence drive (TMEAD): toward improving the adherence of the patients with drug-sensitive tuberculosis in Nashik, Maharashtra. Front. public Heal.2022, 10, 1021427. [CrossRef]

- Sazali, M.F.; Rahim, S.S.S.A.; Mohammad, A.H.; Kadir, F.; Payus, A.O.; Avoi, R.; Jeffree, M.S.; Omar, A.; Ibrahim, M.Y.; Atil, A.; Tuah, N.M.; Dapari, R.; Lansing, M.G.; Rahim, A.A.A.; Azhar, Z.I. Improving Tuberculosis Medication Adherence: The Potential of Integrating Digital Technology and Health Belief Model. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2023 Apr;86(2):82-93. Epub 2022 Dec 23. [CrossRef]

- Batte, C.; Namusobya, M.; Kirabo, R.; Mukisa, J.; Adakun, S.; & Katamba, A. Prevalence and factors associated with non-adherence to multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) treatment at Mulago National Referral Hospital, Kampala, Uganda. African Health Sciences, 2021, 21(1), 238-47. [CrossRef]

- Daftary, A.; Padayatchi, N.; & O’Donnell, M. R. Preferential adherence to antiretroviral therapy over tuberculosis treatment: a qualitative study of drug-resistant TB/HIV co-infected patients in South Africa. Global Public Health, 2014, 9(9), 1107-1116. [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, K.W.; Humble, S.; McQueen, A.; Hunleth, J.M.; Chang, S.H.; Herrick, C.J.; James, A.S. Medication Adherence and Characteristics of Patients Who Spend Less on Basic Needs to Afford Medications. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021 May-Jun;34(3):561-57. [CrossRef]

- Appiah, M.A.; Arthur, J.A.; Gborgblorvor, D.; Asampong, E.; Kye-Duodu, G.; Kamau, E.M.; Dako-Gyeke, P. Barriers to tuberculosis treatment adherence in high-burden tuberculosis settings in Ashanti region, Ghana: a qualitative study from patient's perspective. BMC Public Health. 2023 Jul 10;23(1):1317. [CrossRef]

- Zenbaba, D.; Bonsa, M.; Sahiledengle, B. Trends of unsuccessful treatment outcomes and associated factors among tuberculosis patients in public hospitals of Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia: A 5-year retrospective study. Heliyon. 2021 Sep 1;7(9):e07982.

- M'imunya, J.M.; Kredo, T.; Volmink, J. Patient education and counseling for promoting adherence to treatment for tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 May 16;2012(5): CD006591. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Chung, H.; Muntaner, C. Lee, M.; Kim, Y.; Barry, C.E.; Cho, S.N. The impact of social conditions on patient adherence to pulmonary tuberculosis treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016 Jul;20(7):948-54. [CrossRef]

- Fagundez, G.; Perez-Freixo, H.; Eyene, J.; Momo, J.C.; Biyé, L.; Esono, T.; Ondó Mba Ayecab, M.; Benito, A.; Aparicio, P.; Herrador, Z. Treatment Adherence of Tuberculosis Patients Attending Two Reference Units in Equatorial Guinea. PLoS One. 2016 Sep 13;11(9):e0161995. [CrossRef]

- Leddy, A.M.; Jagannath, D.; Triasih, R.; Wobudeya, E.; Bellotti de Oliveira, M.C.; Sheremeta, Y.; Becerra, M.C.; Chiang, S.S. Social Determinants of Adherence to Treatment for Tuberculosis Infection and Disease Among Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults: A Narrative Review. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2022 Oct 31;11(Supplement_3): S79-S84. [CrossRef]

- Olivier, C.; and Luies, L. WHO Goals, and Beyond: Managing HIV/TB Co-infection in South Africa. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 5, 251,2023. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, F.; Gandhi, N.R.; Brust, J.C.M; Mlisana, K.; Moodley, P.; Allana, S.; Campbell, A.; Shah, S. Treatment Adherence Among Persons Receiving Concurrent Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis and HIV Treatment in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019 Oct 1;82(2):124-130. [CrossRef]

- Danarastri, S.; Perry, K.E.; Hastomo, Y.E.; Priyonugroho, K. Gender differences in health-seeking behavior, diagnosis and treatment for TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022 Jun 1;26(6):568-570. [CrossRef]

- Gast, A.; and Mathes, T. Medication Adherence Influencing Factors—An (Update) Overview of Systematic Reviews. Systematic Review,2019, 8, Article Number: 112. [CrossRef]

- Tupasi, T. E.; Garfin, A. M. C.; Kurbatova, E. V.; Mangan, J. M.; Orillaza-Chi, R.; Naval, L. C.; & Sarol, J. N. Factors associated with loss to follow-up during treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, the Philippines, 2012–2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2016, 22(3), 491-502. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Poonguzhali, S.; Muniyandi, M.; Ovung, S.; Chandra, S.; Subbaraman, R.; & Nagarajan, K. Psycho-socio-economic issues challenging multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients: a systematic review. Plos One, 2016, 11(1), e0147397. [CrossRef]

- Pizzol, D.; Gennaro, F. D.; Chhaganlal, K.; Fabrizio, C.; Monno, L.; Putoto, G.; & Saracino, A. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis in Beira, Mozambique. African Health Sciences, 2017, 17(3), 773. [CrossRef]

- Nyamagoud, S. B.; Viswanatha Swamy, A. H.; Chathamvelli, A.; Patil, K.; Pai, A.; & Baadkar, A. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, practice and medication adherence among tuberculosis patients in tertiary care hospital. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation, 2023, 14(1), 135-140. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhao, A.; & Lu, Z. Non-adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment among internal migrants with pulmonary tuberculosis in shenzhen, china: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health,2015, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Lucya, V.; and Sulistiawati, M. The effect of audio-visual daily reminder on medicine treatment compliance in tuberculosis patients in puskesmas garuda, bandung city. Risenologi, 2022, 7(1a), 26-30. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Khan, O.; Seo, J. H.; Kim, D. Y.; Park, K.; Jung, S.; & Jang, H. Impact of physician's education on adherence to tuberculosis treatment for patients of low socioeconomic status in bangladesh. Chonnam Medical Journal,2013, 49(1), 27. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.; Dhande, D. J.; Sachdeva, K. S.; Sreenivas, A.; Kumar, A. M. V.; Satyanarayana, S.; & Lo, T. Patient and provider reported reasons for loss to follow up in MDRTB treatment: a qualitative study from a drug-resistant tb center in India. Plos One,2015, 10(8), e0135802. [CrossRef]

- Tesfahuneygn, G.; Medhin, G.; & Legesse, M. Adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment and treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients in Alamata district, northeast Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes, 2015, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Kizito, E.; Musaazi, J.; Mutesasira, K.; Twinomugisha, F.; Namwanje, H.; Kiyemba, T.; & Zawedde-Muyanja, S. Risk factors for mortality among patients diagnosed with Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis in uganda- a case-control study. BMC Infectious Diseases, 2021, 21(1). [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, C.; Khan, M.; Yoong, J.; Xu, L.; & Coker, R. Financial barriers and coping strategies: a qualitative study of accessing multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and tuberculosis care in Yunnan, China. BMC Public Health, 2017, 17(1). [CrossRef]

- Anye, L. C.; Bissong, M. E. A.; Njundah, A. L.; & Fodjo, J. N. S. Depression, anxiety and medication adherence among tuberculosis patients attending treatment centres in Fako division, Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. BJPsych Open, 2023, 9(3). [CrossRef]

- Tola, H. H.; Shojaeizadeh, D.; Tol, A.; Garmaroudi, G.; Yekaninejad, M. S.; Kebede, A.; & Klinkenberg, E. A psychological and educational intervention to improve tuberculosis treatment adherence in Ethiopia based on health belief model: a cluster randomized control trial. Plos One,2016, 11(5), e0155147. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).