Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.3 Methods

2.3.1. WUI Definition and Conceptual Framework

2.3.2. Fuel Type Mapping

2.3.3. Dwelling Characterization

2.3.4. Classification of WUI Types

2.3.5. Fire Mapping

2.3.6. Risk Assessment Concept and Workflow

2.3.6.1 Hazard

2.3.6.2 Susceptibility

3. Results

3.1. Fire History and Frequency (1983-2023)

| Burn Frequency | Area (ha) | % of total burned area | % of Attica |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 66,529.97 | 64.99% | 22.74% |

| 2 | 25,835.84 | 25.24% | 8.83% |

| 3 | 7,214.60 | 7.05% | 2.47% |

| 4 | 2,606.71 | 2.55% | 0.89% |

| 5 | 139.55 | 0.14% | 0.05% |

| 6 | 34.07 | 0.03% | 0.01% |

| 7 | 3.75 | <0.01% | <0.01% |

| 8 | 1.59 | <0.01% | <0.01% |

| Total | 102,366.08 | 100% | 34.99% |

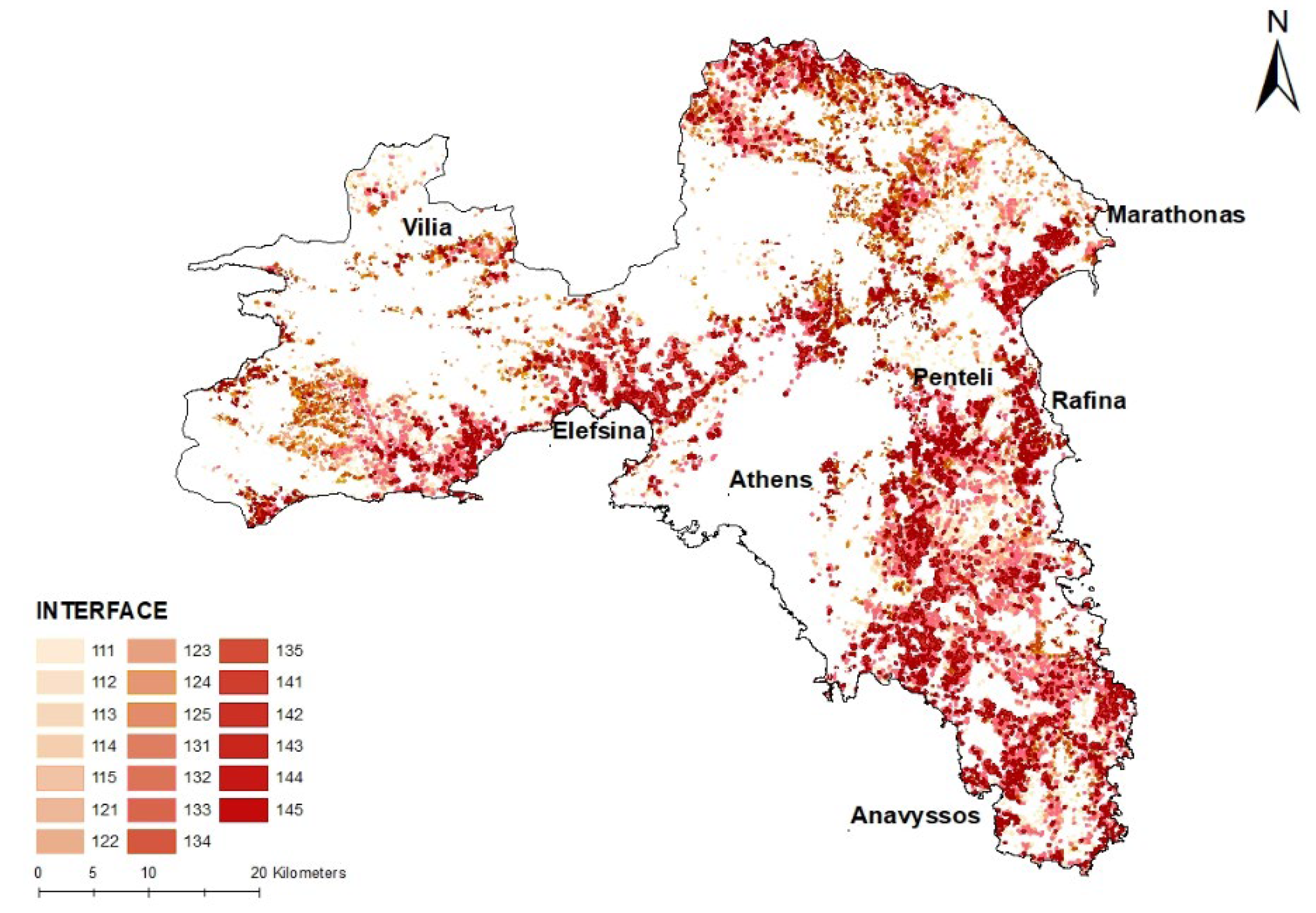

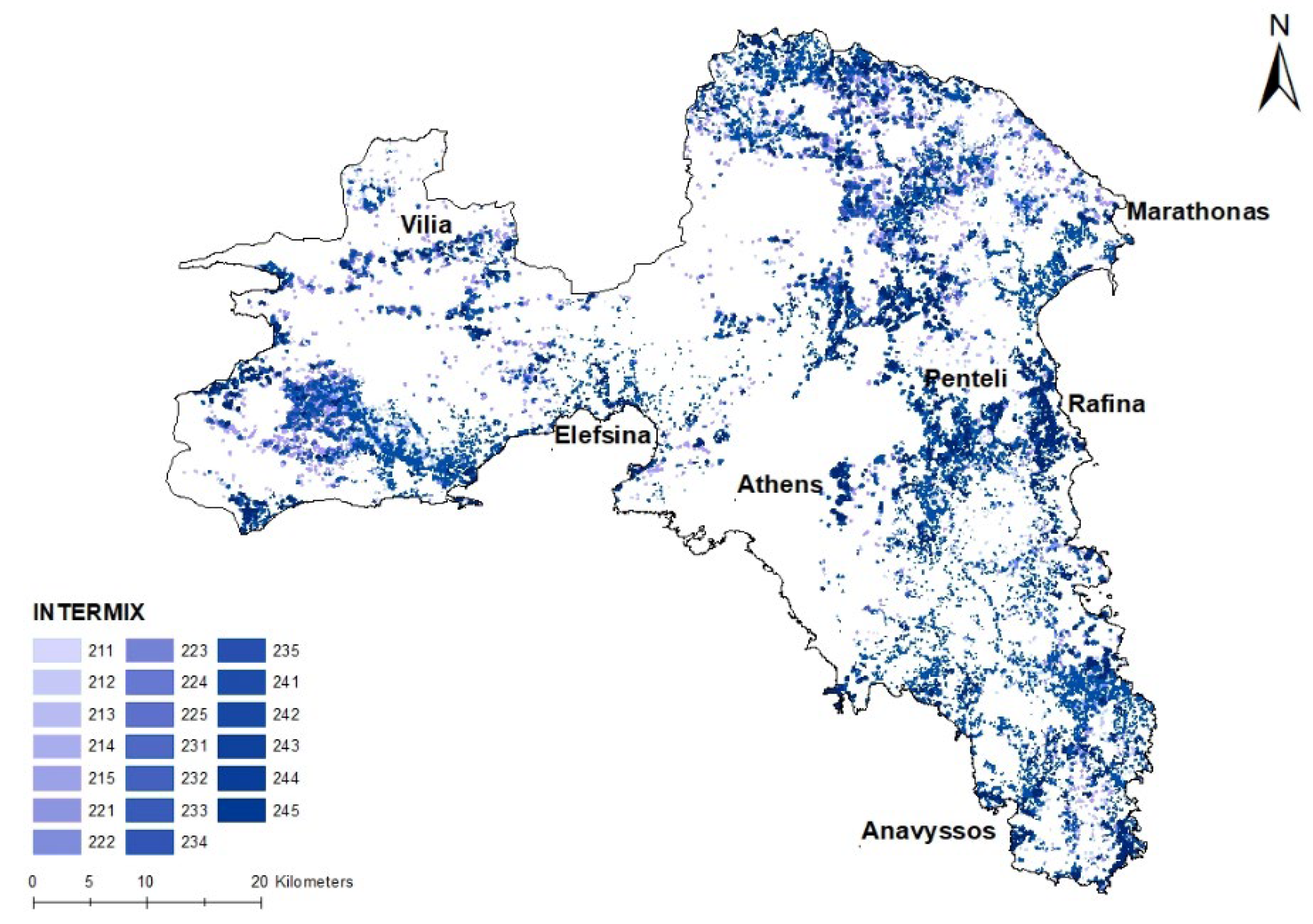

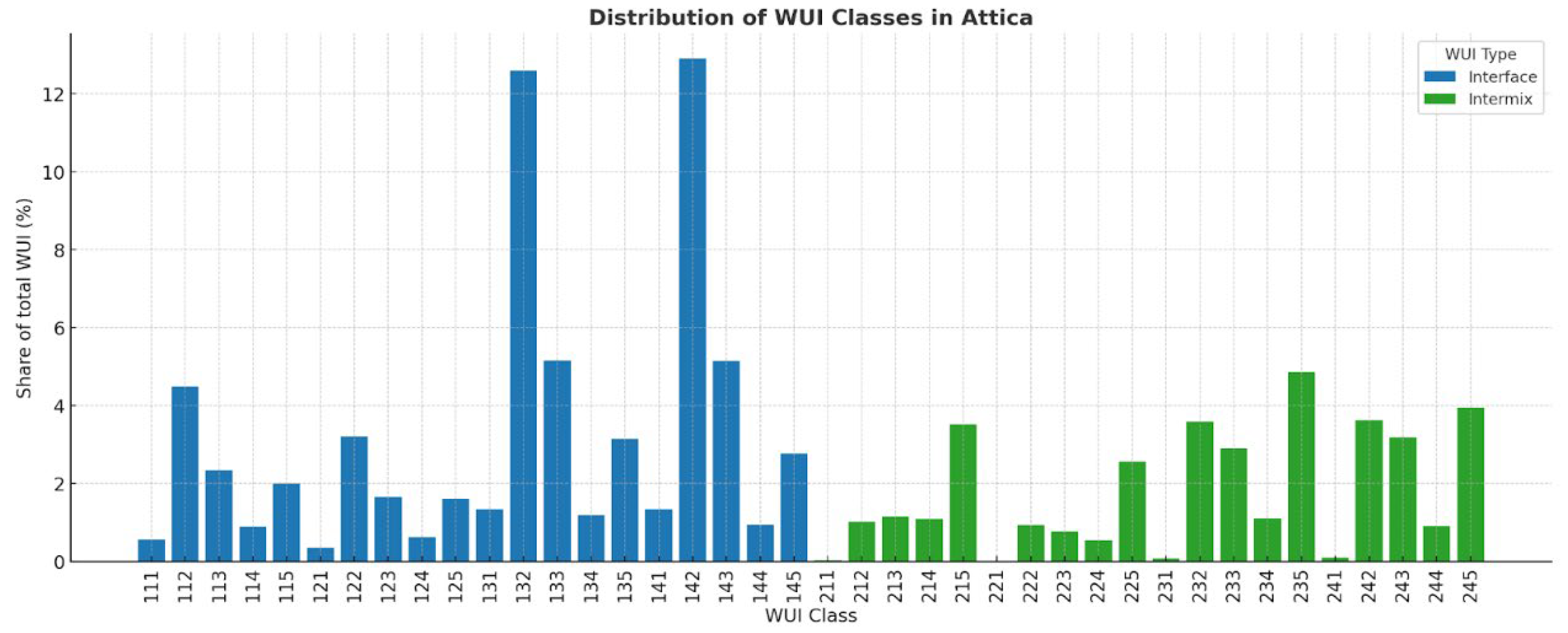

3.2. WUI Distribution

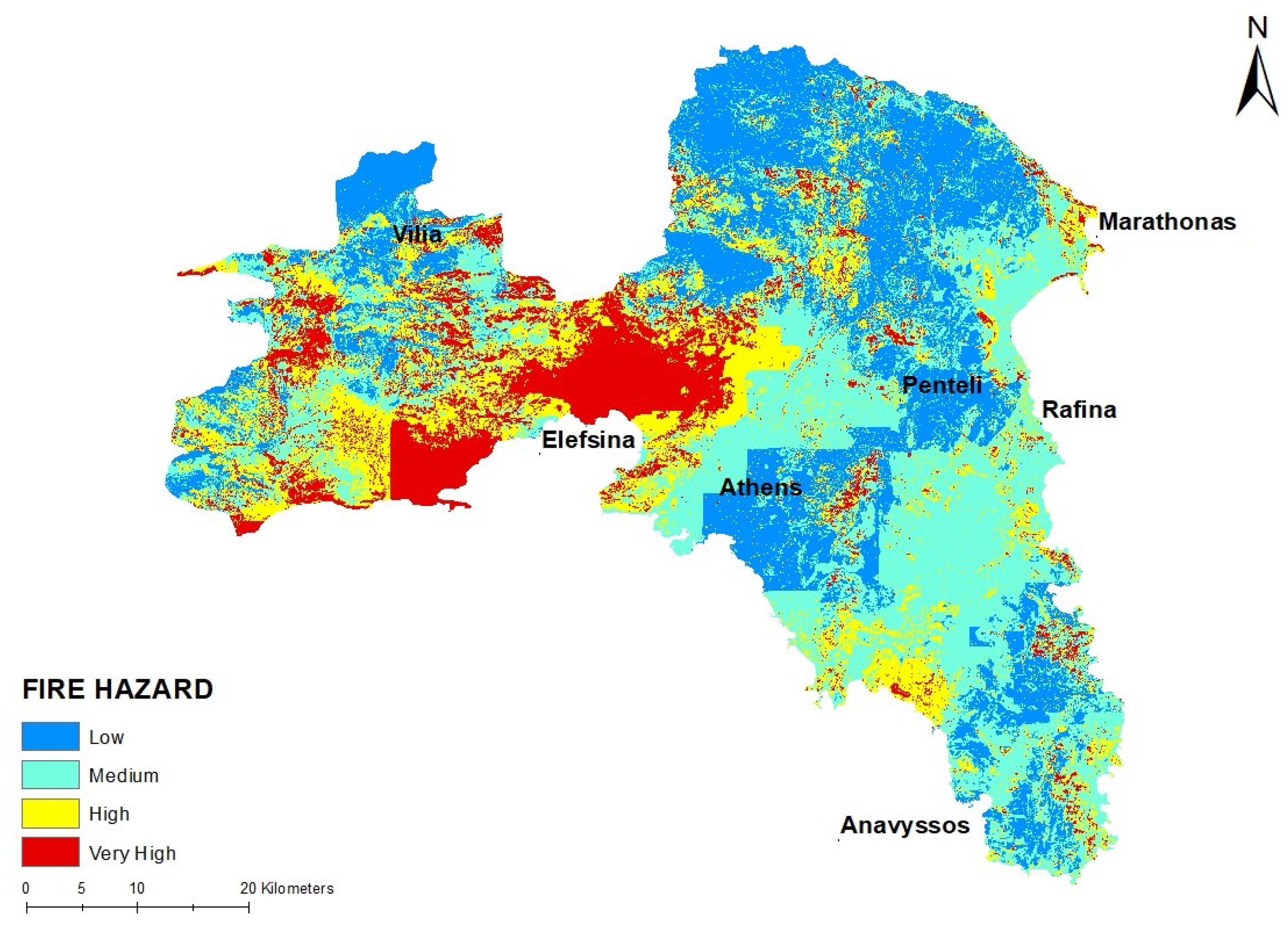

3.3. Hazard

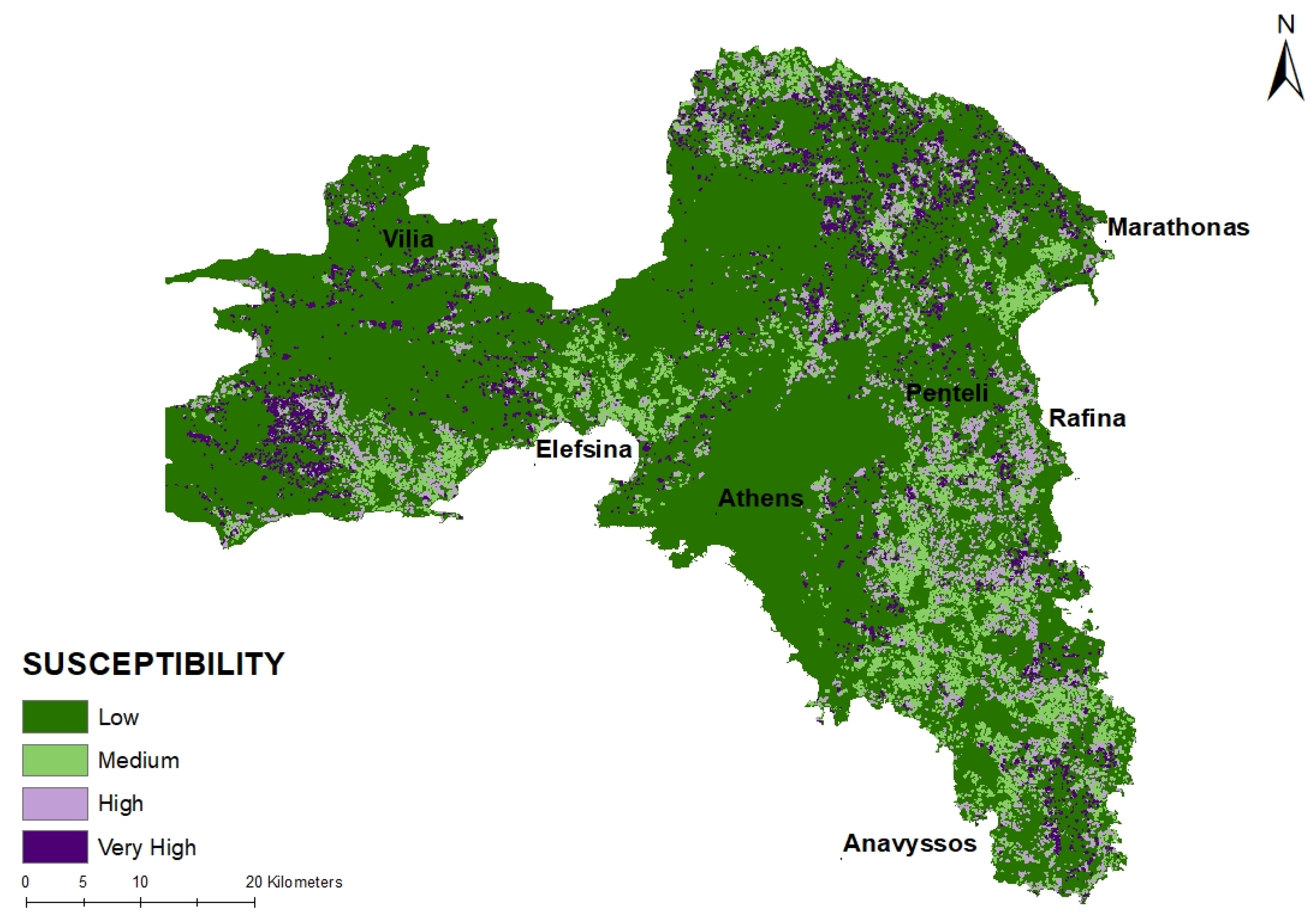

3.4. Susceptibility

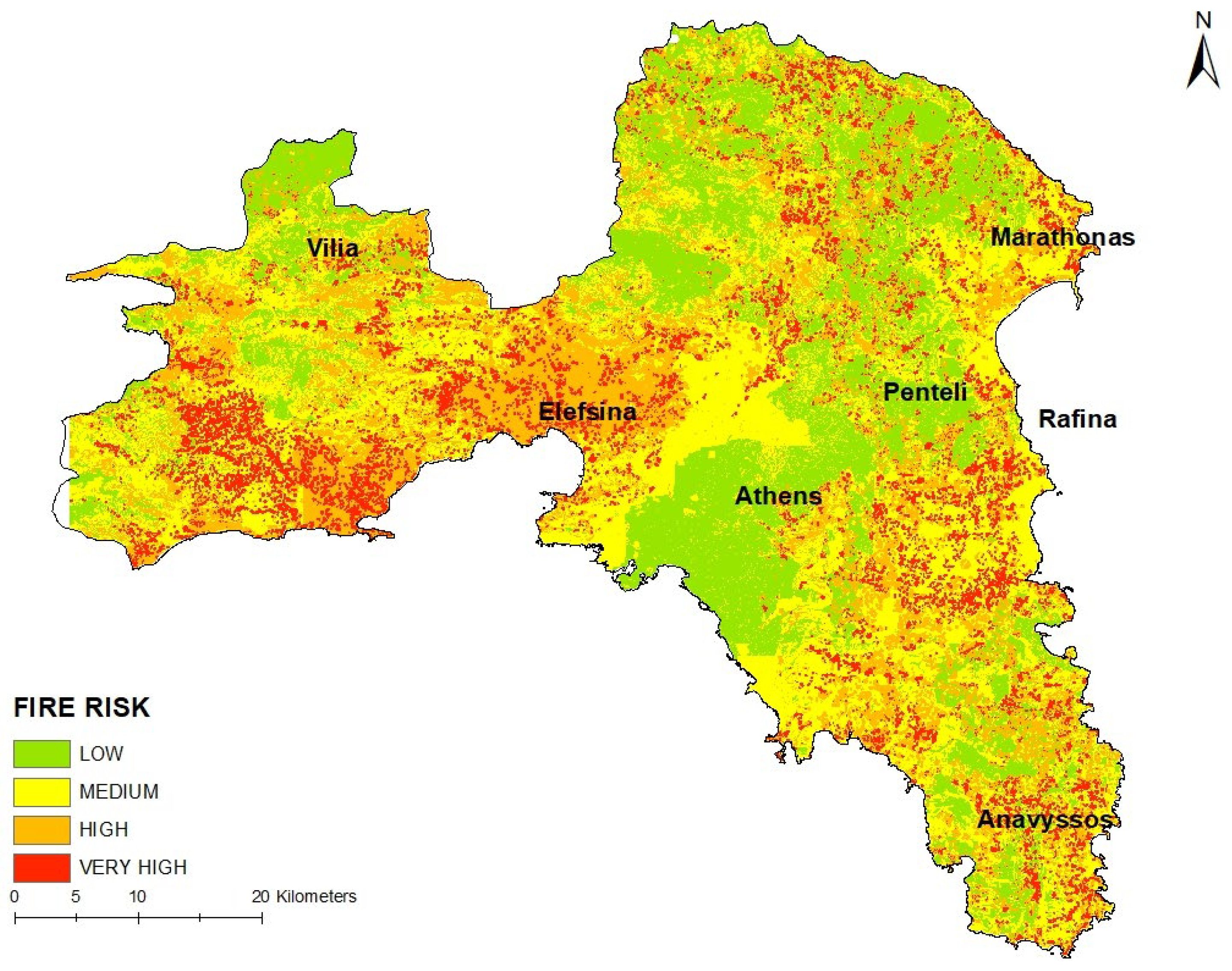

3.5. Integrated Wildfire Risk

4. Discussion

4.1 Key Findings

4.2. WUI Delineation: Methodological Positioning and Comparability

4.3 Integrated Wildfire Risk: Patterns and Drivers

4.4 Implications for Fire-Risk Reduction and Planning

4.5 Limitations

4.6 Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2023.

- Tedim, F.; Leone, V.; Amraoui, M.; Bouillon, C.; Coughlan, M.R.; Delogu, G.M.; Fernandes, P.M.; Ferreira, C.; McCaffrey, S.; McGee, T.K.; et al. Defining Extreme Wildfire Events: Difficulties, Challenges, and Impacts. Fire 2018, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldammer, J.G.; Statheropoulos, M.; Andreae, M.O. Chapter 1 Impacts of Vegetation Fire Emissions on the Environment, Human Health, and Security: A Global Perspective. In Developments in Environmental Science; Elsevier, 2008; Vol. 8, pp. 3–36. ISBN 978-0-08-055609-3.

- Radeloff, V.C.; Hammer, R.B.; Stewart, S.I.; Fried, J.S.; Holcomb, S.S.; McKeefry, J.F. The Wildland–Urban Interface in the United States. Ecological Applications 2005, 15, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.I.; Radeloff, V.C.; Hammer, R.B.; Hawbaker, T.J. Defining the Wildland–Urban Interface. Journal of Forestry 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkin, D.E.; Cohen, J.D.; Finney, M.A.; Thompson, M.P. How Risk Management Can Prevent Future Wildfire Disasters in the Wildland-Urban Interface. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Massada, A.; Radeloff, V.; Stewart, S. Biotic and Abiotic Effects of Human Settlements in the Wildland-Urban Interface. BioScience 2014, 64, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, V.C.; Helmers, D.P.; Kramer, H.A.; Mockrin, M.H.; Alexandre, P.M.; Bar-Massada, A.; Butsic, V.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Martinuzzi, S.; Syphard, A.D.; et al. Rapid Growth of the US Wildland-Urban Interface Raises Wildfire Risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018, 115, 3314–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modugno, S.; Balzter, H.; Cole, B.; Borrelli, P. Mapping Regional Patterns of Large Forest Fires in Wildland–Urban Interface Areas in Europe. Journal of Environmental Management 2016, 172, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabokidis, K.; Palaiologou, P.; Gerasopoulos, E.; Giannakopoulos, C.; Kostopoulou, E.; Zerefos, C. Effect of Climate Change Projections on Forest Fire Behavior and Values-at-Risk in Southwestern Greece. Forests 2015, 6, 2214–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Ascoli, D.; Safford, H.; Adams, M.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Catry, F.X.; Armesto, J.; Bond, W.; González, M.E.; et al. Wildfire Management in Mediterranean-Type Regions: Paradigm Change Needed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Moreno, J.M.; Camia, A. Analysis of Large Fires in European Mediterranean Landscapes: Lessons Learned and Perspectives. Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 294, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomiadis, E.; Soulis, K.X.; Efthimiou, N. Using SCS-CN and Earth Observation for the Comparative Assessment of the Hydrological Effect of Gradual and Abrupt Spatiotemporal Land Cover Changes. Water 2020, 12, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiana-Martín, L. Spatial Planning Experiences for Vulnerability Reduction in the Wildland-Urban Interface in Mediterranean European Countries. European Countryside 2017, 9, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthimiou, N.; Psomiadis, E.; Panagos, P. Fire Severity and Soil Erosion Susceptibility Mapping Using Multi-Temporal Earth Observation Data: The Case of Mati Fatal Wildfire in Eastern Attica, Greece. CATENA 2020, 187, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulos, G. The Forest Fires of 1995 and 1998 on Penteli Mountain. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Workshop “Improving Dispatching for Forest Fire Control”; Chania, 2002; pp. 85–94.

- Arianoutsou, M.; Athanasakis, G.; Kazanis, D.; Christopoulou, A. Attica: A Hot Spot for Forest Fires in Greece. Fire 2024, 7, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMSN170 - Copernicus EMS Mapping | Copernicus EMS On Demand Mapping. Available online: https://mapping.emergency.copernicus.eu/activations/EMSN170/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Operational Mapping and Post-Disaster Hazard Assessment by the Development of a Multiparametric Web App Using Geospatial Technologies and Data: Attica Region 2021 Wildfires (Greece). Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/14/7256?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- EMSR300 - Copernicus EMS Mapping | Copernicus EMS On Demand Mapping. Available online: https://mapping.emergency.copernicus.eu/activations/EMSR300/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Amiridis, V.; Zerefos, C.; Kazadzis, S.; Gerasopoulos, E.; Eleftheratos, K.; Vrekoussis, M.; Stohl, A.; Mamouri, R.E.; Kokkalis, P.; Papayannis, A.; et al. Impact of the 2009 Attica Wild Fires on the Air Quality in Urban Athens. Atmospheric Environment 2012, 46, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restoration of the Forest Ecosystem after the Fire of 2007. Φορέας Διαχείρισης Δρυμού Πάρνηθας 2021.

- Population Censuses 1821 - 2021 - ELSTAT. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/el/census_priv_results_1821-2021 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Salvati, L.; Zitti, M. Sprawl and Mega-Events: Economic Growth and Recent Urban Expansion in a City Losing Its Competitive Edge (Athens, Greece). Urbani izziv 2017, 28, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontos, K.; Antonoglou, D.; Salvati, L.; Maialetti, M.; Kontogiannis, G. Revisiting the Spatial Cycle: Intra-Regional Development Patterns and Future Population Dynamics in Metropolitan Athens, Greece. Economies 2024, 12, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaridis, D.; Symeonakis, E.; Chorianopoulos, I.; Koukoulas, S. Incorporating Density in Spatiotemporal Land Use/Cover Change Patterns: The Case of Attica, Greece. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Neary, D.G. An Overview of FIre Effects on Soils. Southwest Hydrology 2004, 3, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, L.H.; Huffman, E.L. Post-Fire Soil Water Repellency. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2004, 68, 1729–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Llovet, J.; Rodrigo, A.; Vallejo, R. Are Wildfires a Disaster in the Mediterranean Basin? - A Review. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2008, 17, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Viedma, O.; Arianoutsou, M.; Curt, T.; Koutsias, N.; Rigolot, E.; Barbati, A.; Corona, P.; Vaz, P.; Xanthopoulos, G.; et al. Landscape – Wildfire Interactions in Southern Europe: Implications for Landscape Management. Journal of Environmental Management 2011, 92, 2389–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arianoutsou, M.; Kazanis, D.; Kokkoris, Y.; Skourou, P. Land-Use Interactions with Fire in Mediterranean Pinus Halepensis Landscapes of Greece: Patterns of Biodiversity. 2002.

- Lampin-Maillet, C.; Jappiot, M.; Long, M.; Bouillon, C.; Morge, D.; Ferrier, J.-P. Mapping Wildland-Urban Interfaces at Large Scales Integrating Housing Density and Vegetation Aggregation for Fire Prevention in the South of France. Journal of Environmental Management 2010, 91, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, A.; Serra, P.; Modugno, S. Identifying Dynamics of Fire Ignition Probabilities in Two Representative Mediterranean Wildland-Urban Interface Areas. Applied Geography 2011, 31, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.M.; Flannigan, M.D. Mapping Canadian Wildland Fire Interface Areas. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2018, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar del Hoyo, L.; Martín Isabel, M.P.; Martínez Vega, F.J. Logistic Regression Models for Human-Caused Wildfire Risk Estimation: Analysing the Effect of the Spatial Accuracy in Fire Occurrence Data. Eur J Forest Res 2011, 130, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulos, G. Forest Fires, Their Management in Greece and Its Reflection in Attica (in Greek with English abstract). GEOGRAPHIES (1109-186X) 2016, 72–88.

- Zoka, M.; Stasinos, N.; Tsoutsos, M.-C.; Kokkalidou, M.; Girtsou, S.; Yfantidou, A.; Stathopoulos, N.; Kontoes, C. Detailed Wildfire Vulnerability Assessment In Selected Wildland Urban Interface Residential Areas In The Region Of Attica, Greece. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; July 2024; pp. 3316–3321.

- Zikeloglou, I.; Lekkas, E.; Lozios, S.; Stavropoulou, M. Is Early Evacuation the Best and Only Strategy to Protect and Mitigate the Effects of Forest Fires in WUI Areas? A Qualitative Research on the Residents’ Response during the 2021 Forest Fires in NE Attica, Greece. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2023, 88, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouvardos, K.; Kotroni, V.; Giannaros, T.M.; Dafis, S. Meteorological Conditions Conducive to the Rapid Spread of the Deadly Wildfire in Eastern Attica, Greece. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2019, 100, 2137–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Massada, A.B.; Butsic, V.; Keeley, J.E. Land Use Planning and Wildfire: Development Policies Influence Future Probability of Housing Loss. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e71708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Boca, R.; Strobl, P.; Kucera, J.; Pekkarinen, A. Forest Fires in the European Mediterranean Region: Mapping and Analysis of Burned Areas. In Earth Observation of Wildland Fires in Mediterranean Ecosystems; Chuvieco, E., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009; ISBN 978-3-642-01753-7. [Google Scholar]

- Politi, N.; Vlachogiannis, D.; Sfetsos, A.; Gounaris, N. Fire Weather Assessment of Future Changes in Fire Weather Conditions in the Attica Region. Environmental Sciences Proceedings 2023, 26, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erni, S.; Wang, X.; Swystun, T.; Taylor, S.W.; Parisien, M.-A.; Robinne, F.-N.; Eddy, B.; Oliver, J.; Armitage, B.; Flannigan, M.D. Mapping Wildfire Hazard, Vulnerability, and Risk to Canadian Communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2024, 101, 104221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.M.; Carrega, P.; Ren, Y.; Caillouet, P.; Bouillon, C.; Robert, S. How Wildfire Risk Is Related to Urban Planning and Fire Weather Index in SE France (1990–2013). Science of The Total Environment 2018, 621, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-García, V.; Beltrán-Marcos, D.; Calvo, L. Building Patterns and Fuel Features Drive Wildfire Severity in Wildland-Urban Interfaces in Southern Europe. Landscape and Urban Planning 2023, 231, 104646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampin-Maillet, C.; Jappiot, M.; Long, M.; Morge, D.; Ferrier, J.-P. Characterization and Mapping of Dwelling Types for Forest Fire Prevention. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2009, 33, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, S.J.; Rowell, E.M.; Hudak, A.T.; Keane, R.E.; Loudermilk, E.L.; Lutes, D.C.; Ottmar, R.D.; Chappell, L.M.; Hall, J.A.; Hornsby, B.S. Fuels and Consumption. In Wildland Fire Smoke in the United States: A Scientific Assessment; Peterson, D.L., McCaffrey, S.M., Patel-Weynand, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 1–49. ISBN 978-3-030-87045-4. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, A.T.; Baik, J.; Echeverri Figueroa, V.; Rini, D.; Moritz, M.A.; Roberts, D.A.; Sweeney, S.H.; Carvalho, L.M.V.; Jones, C. Developing Effective Wildfire Risk Mitigation Plans for the Wildland Urban Interface. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2023, 124, 103531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calviño-Cancela, M.; Chas-Amil, M.L.; García-Martínez, E.D.; Touza, J. Wildfire Risk Associated with Different Vegetation Types within and Outside Wildland-Urban Interfaces. Forest Ecology and Management 2016, 372, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Marcos, D.; Calvo, L.; Fernández-Guisuraga, J.M.; Fernández-García, V.; Suárez-Seoane, S. Wildland-Urban Interface Typologies Prone to High Severity Fires in Spain. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 894, 165000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, Carl H.; Benson, Nathan C. The Normalized Burn Ratio, a Landsat TM Radiometric Index of Burn Severity Incorporating Multi-Temporal Differencing | Fire Research and Management Exchange System; 1999; p. 39.

- Novo, A.; Fariñas-Álvarez, N.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.; González-Jorge, H.; Fernández-Alonso, J.M.; Lorenzo, H. Mapping Forest Fire Risk—A Case Study in Galicia (Spain). Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Aguado, I.; Yebra, M.; Nieto, H.; Salas, J.; Martín, M.P.; Vilar, L.; Martínez, J.; Martín, S.; Ibarra, P.; et al. Development of a Framework for Fire Risk Assessment Using Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System Technologies. Ecological Modelling 2010, 221, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.H.; Thompson, M.P.; Calkin, D.E. A Wildfire Risk Assessment Framework for Land and Resource Management; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Ft. Collins, CO, 2013; p. RMRS-GTR-315.

- Chuvieco, E.; Yebra, M.; Martino, S.; Thonicke, K.; Gómez-Giménez, M.; San-Miguel, J.; Oom, D.; Velea, R.; Mouillot, F.; Molina, J.R.; et al. Towards an Integrated Approach to Wildfire Risk Assessment: When, Where, What and How May the Landscapes Burn. Fire 2023, 6, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, G.; Vujović, F.; Golijanin, J.; Šiljeg, A.; Valjarević, A. Modelling of Wildfire Susceptibility in Different Climate Zones in Montenegro Using GIS-MCDA. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Ning, Z.; Dahal, R.; Yang, S. Wildfire Susceptibility of Land Use and Topographic Features in the Western United States: Implications for the Landscape Management. Forests 2023, 14, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganteaume, A.; Barbero, R.; Jappiot, M.; Maillé, E. Understanding Future Changes to Fires in Southern Europe and Their Impacts on the Wildland-Urban Interface. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience 2021, 2, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, M.A. The Challenge of Quantitative Risk Analysis for Wildland Fire. Forest Ecology and Management 2005, 211, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.; Paula, S. Fuel Shapes the Fire-Climate Relationship: Evidence from Mediterranean Ecosystems. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2012, 21, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, R.B.; Stewart, S.I.; Radeloff, V.C. Demographic Trends, the Wildland–Urban Interface, and Wildfire Management. Society & Natural Resources 2009, 22, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, R.V. The Wildland–Urban Interface: Evaluating the Definition Effect. Journal of Forestry 2010, 108, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Li, S.; Nguyen, P.; Banerjee, T. Examining the Existing Definitions of Wildland-urban Interface for California. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketchpaw, A.R.; Li, D.; Khan, S.N.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L. Using Structure Location Data to Map the Wildland–Urban Interface in Montana, USA. Fire 2022, 5, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, P.M.; Stewart, S.I.; Mockrin, M.H.; Keuler, N.S.; Syphard, A.D.; Bar-Massada, A.; Clayton, M.K.; Radeloff, V.C. The Relative Impacts of Vegetation, Topography and Spatial Arrangement on Building Loss to Wildfires in Case Studies of California and Colorado. Landscape Ecol 2016, 31, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.N.; Figueiredo, A.; Pinto, C.; Lourenço, L. Assessing Wildfire Hazard in the Wildland–Urban Interfaces (WUIs) of Central Portugal. Forests 2023, 14, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannaros, T.M.; Papavasileiou, G.; Lagouvardos, K.; Kotroni, V.; Dafis, S.; Karagiannidis, A.; Dragozi, E. Meteorological Analysis of the 2021 Extreme Wildfires in Greece: Lessons Learned and Implications for Early Warning of the Potential for Pyroconvection. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, G.K.; Holden, Z.A.; Morgan, P.; Crimmins, M.A.; Heyerdahl, E.K.; Luce, C.H. Both Topography and Climate Affected Forest and Woodland Burn Severity in Two Regions of the Western US, 1984 to 2006. Ecosphere 2011, 2, art130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, N.; Mahler, P.; Beverly, J.L. Optimizing Fuel Treatments for Community Wildfire Mitigation Planning. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 370, 122325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agee, J.K.; Skinner, C.N. Basic Principles of Forest Fuel Reduction Treatments. Forest Ecology and Management 2005, 211, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M. Fire-Smart Management of Forest Landscapes in the Mediterranean Basin under Global Change. Landscape and Urban Planning 2013, 110, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, M.M.; Sadler, R.J.; Wittkuhn, R.S.; McCaw, L.; Grierson, P.F. Long-Term Impacts of Prescribed Burning on Regional Extent and Incidence of Wildfires—Evidence from 50 Years of Active Fire Management in SW Australian Forests. Forest Ecology and Management 2009, 259, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Keeley, J.E. Factors Associated with Structure Loss in the 2013–2018 California Wildfires. Fire 2019, 2, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.D. Preventing Disaster: Home Ignitability in the Wildland-Urban Interface. Journal of Forestry 2000, 98, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffault, J.; Mouillot, F. Contribution of Human and Biophysical Factors to the Spatial Distribution of Forest Fire Ignitions and Large Wildfires in a French Mediterranean Region. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2017, 26, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Calcerrada, R.; Novillo, C.J.; Millington, J.D.A.; Gomez-Jimenez, I. GIS Analysis of Spatial Patterns of Human-Caused Wildfire Ignition Risk in the SW of Madrid (Central Spain). Landscape Ecol 2008, 23, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catry, F.X.; Rego, F.C.; Bação, F.L.; Moreira, F. Modeling and Mapping Wildfire Ignition Risk in Portugal. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, R.E. Wildland Fuel Fundamentals and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-09014-6. [Google Scholar]

- Varela Fire Weather Index (FWI) Classification for Fire Danger Assessment Applied in Greece. Tethys 2015. [CrossRef]

| Utilisation | Data | Data Characteristic | Acquisition Date/ Date of Creation |

|---|---|---|---|

| WUI mapping | Urban structures | UCR-STAR (Database); Building footprints (https://star.cs.ucr.edu/) | 2014-2021 |

| Corine Land Cover | Copernicus Database; Static, classified, continental-scale land cover map, utilising a Minimum Mapping Unit (MMU) of 25ha for areal phenomena (https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover) | 2018 | |

| Reference Parcels | Land Parcel Identification System (LPIS) | 2020 | |

| Forest maps | National Cadastral Organization | 2022 | |

| Dominant leaf type, Tree cover density, Small woody features maps | Copernicus Database; High resolution (vector/raster 5m/100m) (https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products) | 2018 | |

| Comparison of vegetation data/ building structures validation | Orthophoto maps | Aerial photographs orthorectified (1 m spatial resolution) | 2014 |

| DEM/slope | Topographic maps | Hellenic Military Geographical Service at 1:5.000 scale/maps | 1988-1994 |

| Risk Assessment | FWI90 Index | Modified from Politi et al (2023)[43]. National Centre for Scientific Research “Demokritos”; FWI threshold value of the 90th percentile for RCP 4.5 |

2025-2049 |

| Historical Burn Scar delineation |

Landsat 4, 5, 7, 8, 9 | U.S. Geological Survey; Spectral bands Near-Infrared and SWIR (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) | 1983-2023 |

| Final class | Description | Final class | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 111 | Interface, Isolated dwelling, Broadleaf | 211 | Intermix, Isolated dwelling, Broadleaf |

| 112 | Interface, Isolated dwelling, Shrubs | 212 | Intermix, Isolated dwelling, Shrubs |

| 113 | Interface, Isolated dwelling, Coniferous | 213 | Intermix, Isolated dwelling, Coniferous |

| 114 | Interface, Isolated dwelling, Mixed type 1 | 214 | Intermix, Isolated dwelling, Mixed type 1 |

| 115 | Interface, Isolated dwelling, Mixed type 2 | 215 | Intermix, Isolated dwelling, Mixed type 2 |

| 121 | Interface, Scattered dwelling, Broadleaf | 221 | Intermix, Scattered dwelling, Broadleaf |

| 122 | Interface, Scattered dwelling, Shrubs | 222 | Intermix, Scattered dwelling, Shrubs |

| 123 | Interface, Scattered dwelling, Coniferous | 223 | Intermix, Scattered dwelling, Coniferous |

| 124 | Interface, Scattered dwelling, Mixed type 1 | 224 | Intermix, Scattered dwelling, Mixed type 1 |

| 125 | Interface, Scattered dwelling, Mixed type 2 | 225 | Intermix, Scattered dwelling, Mixed type 2 |

| 131 | Interface, Dense cluster dwelling, Broadleaf | 231 | Intermix, Dense cluster dwelling, Broadleaf |

| 132 | Interface, Dense cluster dwelling, Shrubs | 232 | Intermix, Dense cluster dwelling, Shrubs |

| 133 | Interface, Dense cluster dwelling, Coniferous | 233 | Intermix, Dense cluster dwelling, Coniferous |

| 134 | Interface, Dense cluster dwelling, Mixed type 1 | 234 | Intermix, Dense cluster dwelling, Mixed type 1 |

| 135 | Interface, Dense cluster dwelling, Mixed type 2 | 235 | Intermix, Dense cluster dwelling, Mixed type 2 |

| 141 | Interface, Very dense cluster dwelling, Broadleaf | 241 | Intermix, Very dense cluster dwelling, Broadleaf |

| 142 | Interface, Very dense cluster dwelling, Shrubs | 242 | Intermix, Very dense cluster dwelling, Shrubs |

| 143 | Interface, Very dense cluster dwelling, Coniferous | 243 | Intermix, Very dense cluster dwelling, Coniferous |

| 144 | Interface, Very dense cluster dwelling, Mixed type 1 | 244 | Intermix, Very dense cluster dwelling, Mixed type 1 |

| 145 | Interface, Very dense cluster dwelling, Mixed type 2 | 245 | Intermix, Very dense cluster dwelling, Mixed type 2 |

| Class | Area (ha) | % of Attica | % of WUI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 111 | 431.34 | 0.147% | 0.56% |

| 112 | 3,448.62 | 1.179% | 4.48% |

| 113 | 1,795.39 | 0.614% | 2.33% |

| 114 | 684.27 | 0.234% | 0.89% |

| 115 | 1537.4 | 0.526% | 2.00% |

| 121 | 269.13 | 0.092% | 0.35% |

| 122 | 2,472.54 | 0.845% | 3.21% |

| 123 | 1266.33 | 0.433% | 1.65% |

| 124 | 478.94 | 0.164% | 0.62% |

| 125 | 1,228.66 | 0.420% | 1.60% |

| 131 | 1,025.42 | 0.351% | 1.33% |

| 132 | 9,690.65 | 3.313% | 12.60% |

| 133 | 3,957.57 | 1.353% | 5.15% |

| 134 | 904.59 | 0.309% | 1.18% |

| 135 | 2,412.53 | 0.825% | 3.14% |

| 141 | 1,031.54 | 0.353% | 1.34% |

| 142 | 9,921.46 | 3.392% | 12.90% |

| 143 | 3,952.69 | 1.351% | 5.14% |

| 144 | 719.64 | 0.246% | 0.94% |

| 145 | 2,120.22 | 0.725% | 2.76% |

| 211 | 26.53 | 0.009% | 0.03% |

| 212 | 775.5 | 0.265% | 1.01% |

| 213 | 883.96 | 0.302% | 1.15% |

| 214 | 837.88 | 0.286% | 1.09% |

| 215 | 2,699.03 | 0.923% | 3.51% |

| 221 | 13.44 | 0.005% | 0.02% |

| 222 | 716.14 | 0.245% | 0.93% |

| 223 | 588.07 | 0.201% | 0.76% |

| 224 | 415.93 | 0.142% | 0.54% |

| 225 | 1,959.54 | 0.670% | 2.55% |

| 231 | 51.39 | 0.018% | 0.07% |

| 232 | 2,753.54 | 0.941% | 3.58% |

| 233 | 2,227.63 | 0.762% | 2.90% |

| 234 | 842.16 | 0.288% | 1.10% |

| 235 | 3,738.68 | 1.278% | 4.86% |

| 241 | 73.78 | 0.025% | 0.10% |

| 242 | 2,786.98 | 0.953% | 3.62% |

| 243 | 2,442.26 | 0.835% | 3.18% |

| 244 | 696.82 | 0.238% | 0.91% |

| 245 | 3,031.28 | 1.036% | 3.94% |

| Total: | 76,909.47 | 26.292% | 100.00% |

| Hazard level | Area (ha) | % of Attica |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 89,831.48 | 30.85% |

| Moderate | 107,295.65 | 36.85% |

| High | 54,440.38 | 18.70% |

| Very High | 39,624.79 | 13.61% |

| Total | 291,192.30 | 100.00% |

| Susceptibility level | Area (ha) | % of Attica |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 221,582.66 | 75.88% |

| Moderate | 28,364.49 | 9.71% |

| High | 24,394.94 | 8.35% |

| Very High | 17,672.12 | 6.05% |

| Total | 292,014.21 | 100.00% |

| Risk level | Area (ha) | % of Attica |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 83,341.02 | 28.75% |

| Moderate | 97,127.78 | 33.51% |

| High | 71,438.89 | 24.64% |

| Very High | 37,978.20 | 13.10% |

| Total | 289,885.89 | 100.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).