Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

12 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Computational Work

2.2. Tumor Cell Fractionation and Immunoblotting.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Human HB Cell Lines: Still a Dismal State of Affairs

3.1. Background

3.2. The Current Status of Human HB Cell Lines

3.3. HepG2 Cells

| Name of cell line | Patient origin | Relevant mutations, de-regulated oncogenes and/or tumor suppressors |

Comments | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HepG2 | 15 yo male | β−cat (in-frame deletion), Tert promoterG222A | [41,42,45,49,50] | |

| Huh6 | 1 yo male | β−cateninG34V | [37,49,51,52] | |

| HepT1 | 3 yo female | [53] | ||

| HepT3 | 9 mo male | [54] | ||

| Hep293TT | 5 yo female | β−catenin (in-frame deletion) | [55] | |

| HepU1, HepU2 | 3 yo male | 2 lines from same HB | [56] | |

| HB1 | 6 mo male | High MYC & H-RAS expression | [57] | |

| OHR | 4 mo male | TP53, β−cateninR281H | [58] |

3.4. Huh6 Cells

3.5. Molecular Heterogeneity of Human HB Cell Lines

3.6. The Oncogenic Drivers of Human HB

| Name of driver | Function | % tumors | Form of de-regulation* | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β−catenin | oncogene | ~60-80 | PM, DEL | [10,25,44,46,50,73] |

| Hippo/YAP/TAZ | oncogene | ~50-60 | O | [40,80,82,85] |

| NFR2/NFE2L2 | oncogene | ~50 | A, PM | [13,73,81] |

| TERT | oncogene | 6 | pMut+ | [73,74] |

| MYC | oncogene | ~25-5- | CNV, OE | [10,14,54] |

| APC | TS | 15 | TRUNC | [83,87,88,89] |

| AXIN1/2 | TS | 8 | PM | [48,90,91] |

| ARID1A | TS | 6 | O | [74] |

| CDKN2A | TS | 50 | pMe, O | [34,92,93] |

4. Murine HB Cell Lines: Recent Progress and the Meeting of (Some) Unfulfilled Needs

4.1. Background

4.2. Chemically-Induced Murine HB Cell Lines

4.3. Genetically-Defined Murine HB Cell Lines: Enforced Over-Expression of Mutant Forms of β-Catenin, YAP and NRF2

4.4. Genetically-Defined Murine HB Cell Lines: Enforced Over-Expression of MYC.

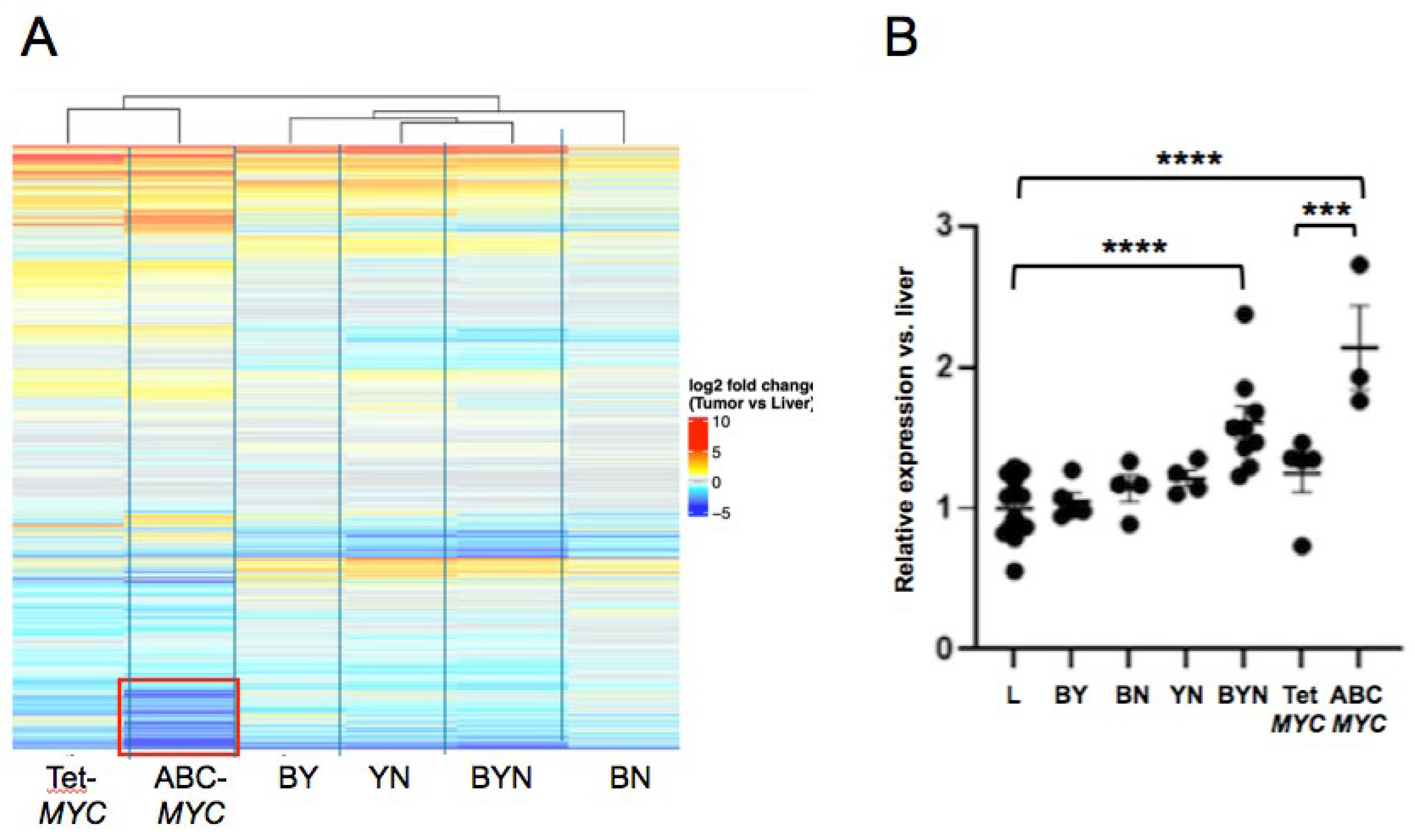

5. Relatedness of Murine HB Cell Lines

5.1. Genetic Relatedness

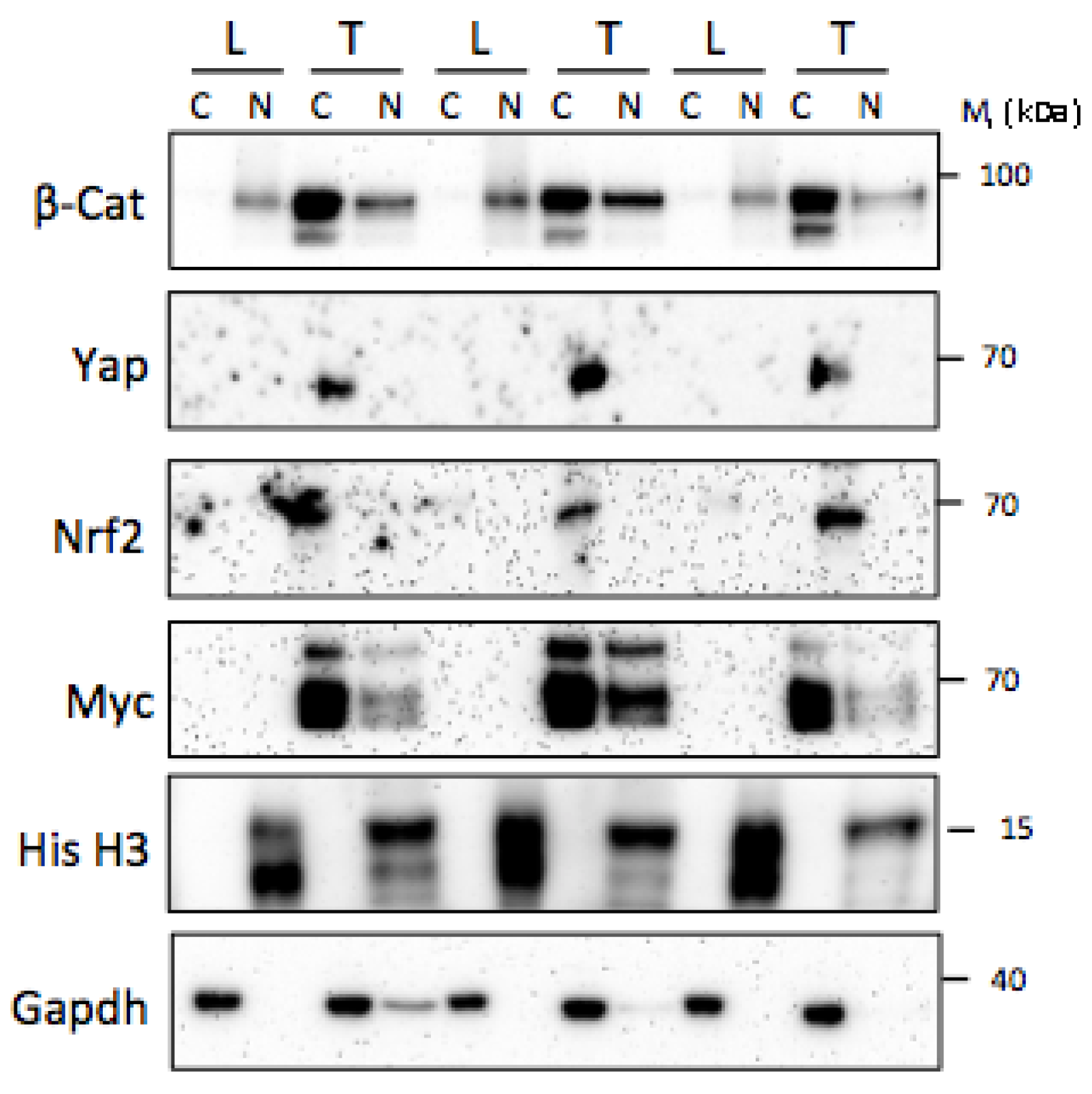

5.2. Post-Translational Relatedness

6. Caveats to the Use of Murine Cell Lines for Drug Screening

7. Advantages and Disadvantages of Human and Murine Cell Lines

7.1. Background

7.2. Human Cell Lines

7.3. Murine Cell Lines

8. Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B: | A patient-derived mutant form of the β-catenin transcription factor |

| BN: | Tumor or cell line driven by the combination of B and N oncoproteins |

| BY: | Tumor or cell line driven by the combination of B and Y oncoproteins |

| BYN: | Tumor or cell line driven by the combination of B, Y and N oncoproteins |

| DEN: | dienthylnitrosamine |

| EC: | Endothelial cell |

| Fah: | fumarylacetoacetate hydrolyase |

| HB: | Hepatoblastoma |

| HCC: | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| N: | A patient-derived constitutively active form of the NRF2 transcription factor |

| PB: | Phenobarbitol |

| TF: | Transcription factor |

| TS: | Tumor suppressor |

| Y: | A constitutively activated form of the yes-associated protein transcription factor (YAPS127A) |

| YN: | Tumor or cell line driven by the combination of Y and N oncoproteins |

References

- Kahla, J.A.; Siegel, D.A.; Dai, S.; Lupo, P.J.; Foster, J.H.; Scheurer, M.E.; Heczey, A.A. Incidence and 5-year survival of children and adolescents with hepatoblastoma in the United States. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29763. [CrossRef]

- Pio, L.; O'Neill, A.F.; Woodley, H.; Murphy, A.J.; Tiao, G.; Franchi-Abella, S.; Fresneau, B.; Watanabe, K.; Alaggio, R.; Lopez-Terrada, D.; et al. Hepatoblastoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2025, 11, 36. [CrossRef]

- Trobaugh-Lotrario, A.D.; Feusner, J.H. Relapsed hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012, 59, 813-817. [CrossRef]

- Trobaugh-Lotrario, A.D.; Katzenstein, H.M. Chemotherapeutic approaches for newly diagnosed hepatoblastoma: past, present, and future strategies. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012, 59, 809-812. [CrossRef]

- Lim, I.I.P.; Bondoc, A.J.; Geller, J.I.; Tiao, G.M. Hepatoblastoma-The Evolution of Biology, Surgery, and Transplantation. Children (Basel) 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Sindhi, R.; Rohan, V.; Bukowinski, A.; Tadros, S.; de Ville de Goyet, J.; Rapkin, L.; Ranganathan, S. Liver Transplantation for Pediatric Liver Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, A.K.; Spector, L.G.; Fortuna, G.; Marcotte, E.L.; Poynter, J.N. Trends in International Incidence of Pediatric Cancers in Children Under 5 Years of Age: 1988-2012. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2019, 3, pkz007. [CrossRef]

- Dembowska-Baginska, B.; Wieckowska, J.; Brozyna, A.; Swieszkowska, E.; Ismail, H.; Broniszczak-Czyszek, D.; Stefanowicz, M.; Grajkowska, W.; Kalicinski, P. Health Status in Long-Term Survivors of Hepatoblastoma. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Hiyama, E.; Hishiki, T.; Watanabe, K.; Ida, K.; Ueda, Y.; Kurihara, S.; Yano, M.; Hoshino, K.; Yokoi, A.; Takama, Y.; et al. Outcome and Late Complications of Hepatoblastomas Treated Using the Japanese Study Group for Pediatric Liver Tumor 2 Protocol. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 2488-2498. [CrossRef]

- Cairo, S.; Armengol, C.; De Reynies, A.; Wei, Y.; Thomas, E.; Renard, C.A.; Goga, A.; Balakrishnan, A.; Semeraro, M.; Gresh, L.; et al. Hepatic stem-like phenotype and interplay of Wnt/beta-catenin and Myc signaling in aggressive childhood liver cancer. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 471-484. [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Reixach, J.; Torrens, L.; Simon-Coma, M.; Royo, L.; Domingo-Sabat, M.; Abril-Fornaguera, J.; Akers, N.; Sala, M.; Ragull, S.; Arnal, M.; et al. Epigenetic footprint enables molecular risk stratification of hepatoblastoma with clinical implications. J Hepatol 2020, 73, 328-341. [CrossRef]

- Hooks, K.B.; Audoux, J.; Fazli, H.; Lesjean, S.; Ernault, T.; Dugot-Senant, N.; Leste-Lasserre, T.; Hagedorn, M.; Rousseau, B.; Danet, C.; et al. New insights into diagnosis and therapeutic options for proliferative hepatoblastoma. Hepatology 2018, 68, 89-102. [CrossRef]

- Sumazin, P.; Chen, Y.; Trevino, L.R.; Sarabia, S.F.; Hampton, O.A.; Patel, K.; Mistretta, T.A.; Zorman, B.; Thompson, P.; Heczey, A.; et al. Genomic analysis of hepatoblastoma identifies distinct molecular and prognostic subgroups. Hepatology 2017, 65, 104-121. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Solinas, A.; Cairo, S.; Evert, M.; Chen, X.; Calvisi, D.F. Molecular Mechanisms of Hepatoblastoma. Semin Liver Dis 2021, 41, 28-41. [CrossRef]

- Malone, E.R.; Oliva, M.; Sabatini, P.J.B.; Stockley, T.L.; Siu, L.L. Molecular profiling for precision cancer therapies. Genome Med 2020, 12, 8. [CrossRef]

- Pleasance, E.; Bohm, A.; Williamson, L.M.; Nelson, J.M.T.; Shen, Y.; Bonakdar, M.; Titmuss, E.; Csizmok, V.; Wee, K.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; et al. Whole-genome and transcriptome analysis enhances precision cancer treatment options. Ann Oncol 2022, 33, 939-949. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.P.; Rai, S.; Pandey, A.; Singh, N.K.; Srivastava, S. Molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer: An emerging therapeutic opportunity for personalized medicine. Genes Dis 2021, 8, 133-145. [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Duan, J.J.; Bian, X.W.; Yu, S.C. Triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtyping and treatment progress. Breast Cancer Res 2020, 22, 61. [CrossRef]

- Dharia, N.V.; Kugener, G.; Guenther, L.M.; Malone, C.F.; Durbin, A.D.; Hong, A.L.; Howard, T.P.; Bandopadhayay, P.; Wechsler, C.S.; Fung, I.; et al. A first-generation pediatric cancer dependency map. Nat Genet 2021, 53, 529-538. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Singh, S.; Cheng, C.; Natarajan, S.; Sheppard, H.; Abu-Zaid, A.; Durbin, A.D.; Lee, H.W.; Wu, Q.; Steele, J.; et al. Genome-wide mapping of cancer dependency genes and genetic modifiers of chemotherapy in high-risk hepatoblastoma. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4003. [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, H.; Rauenzahn, S.; Shim, J.S.; Karikari, C.A.; Feldmann, G.; Hua, L.; Kamiyama, M.; Schuler, F.W.; Lin, M.T.; Beaty, R.M.; et al. Personalized chemotherapy profiling using cancer cell lines from selectable mice. Clin Cancer Res 2013, 19, 1139-1146. [CrossRef]

- Katti, A.; Diaz, B.J.; Caragine, C.M.; Sanjana, N.E.; Dow, L.E. CRISPR in cancer biology and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2022, 22, 259-279. [CrossRef]

- Mirabelli, P.; Coppola, L.; Salvatore, M. Cancer Cell Lines Are Useful Model Systems for Medical Research. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Wang, S.; Gou, X. A review for cell-based screening methods in drug discovery. Biophys Rep 2021, 7, 504-516. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Meyfeldt, J.; Wang, H.; Kulkarni, S.; Lu, J.; Mandel, J.A.; Marburger, B.; Liu, Y.; Gorka, J.E.; Ranganathan, S.; et al. beta-Catenin mutations as determinants of hepatoblastoma phenotypes in mice. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 17524-17542. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, J.; Edmunds, L.R.; Kulkarni, S.; Dolezal, J.; Tao, J.; Ranganathan, S.; Jackson, L.; Fromherz, M.; Beer-Stolz, D.; et al. Coordinated Activities of Multiple Myc-dependent and Myc-independent Biosynthetic Pathways in Hepatoblastoma. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 26241-26251. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646-674. [CrossRef]

- Adeshakin, F.O.; Adeshakin, A.O.; Afolabi, L.O.; Yan, D.; Zhang, G.; Wan, X. Mechanisms for Modulating Anoikis Resistance in Cancer and the Relevance of Metabolic Reprogramming. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 626577. [CrossRef]

- Claveria-Cabello, A.; Herranz, J.M.; Latasa, M.U.; Arechederra, M.; Uriarte, I.; Pineda-Lucena, A.; Prosper, F.; Berraondo, P.; Alonso, C.; Sangro, B.; et al. Identification and experimental validation of druggable epigenetic targets in hepatoblastoma. J Hepatol 2023, 79, 989-1005. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.; Clouaire, T.; Bao, X.X.; Kemp, S.E.; Xenophontos, M.; de Las Heras, J.I.; Stancheva, I. Immortality, but not oncogenic transformation, of primary human cells leads to epigenetic reprogramming of DNA methylation and gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, 3529-3541. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, Q.; Ju, Y.; Song, G. Role of the mechanical microenvironment in cancer development and progression. Cancer Biol Med 2020, 17, 282-292. [CrossRef]

- Pipiya, V.V.; Gilazieva, Z.E.; Issa, S.S.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Solovyeva, V.V. Comparison of primary and passaged tumor cell cultures and their application in personalized medicine. Explor Target Antitumor Ther 2024, 5, 581-599. [CrossRef]

- Rikhi, R.R.; Spady, K.K.; Hoffman, R.I.; Bateman, M.S.; Bateman, M.; Howard, L.E. Hepatoblastoma: A Need for Cell Lines and Tissue Banks to Develop Targeted Drug Therapies. Front Pediatr 2016, 4, 22. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, J.; Chen, K.; Ma, B.; Henchy, C.; Knapp, J.; Ranganathan, S.; Prochownik, E.V. Efficient derivation of immortalized, isogenic cell lines from genetically defined murine hepatoblastomas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2025, 780, 152478. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Toksoz, A.; Henchy, C.; Knapp, J.; Lu, J.; Ranganathan, S.; Wang, H.; Prochownik, E.V. Derivation of Genetically Defined Murine Hepatoblastoma Cell Lines with Angiogenic Potential. Cancers 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Aden, D.P.; Fogel, A.; Plotkin, S.; Damjanov, I.; Knowles, B.B. Controlled synthesis of HBsAg in a differentiated human liver carcinoma-derived cell line. Nature 1979, 282, 615-616. [CrossRef]

- Doi, I. Establishment of a cell line and its clonal sublines from a patient with hepatoblastoma. Gan 1976, 67, 1-10.

- Zheng, M.H.; Zhang, L.; Gu, D.N.; Shi, H.Q.; Zeng, Q.Q.; Chen, Y.P. Hepatoblastoma in adult: review of the literature. J Clin Med Res 2009, 1, 13-16. [CrossRef]

- NCI. Cancer Disparities. 2025.

- Prochownik, E.V. Reconciling the Biological and Transcriptional Variability of Hepatoblastoma with Its Mutational Uniformity. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Arzumanian, V.A.; Kiseleva, O.I.; Poverennaya, E.V. The Curious Case of the HepG2 Cell Line: 40 Years of Expertise. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Terrada, D.; Cheung, S.W.; Finegold, M.J.; Knowles, B.B. Hep G2 is a hepatoblastoma-derived cell line. Hum Pathol 2009, 40, 1512-1515. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Ho, S.S.; Greer, S.U.; Spies, N.; Bell, J.M.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Arthur, J.G.; Byeon, S.; Pattni, R.; et al. Haplotype-resolved and integrated genome analysis of the cancer cell line HepG2. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 3846-3861. [CrossRef]

- Blaker, H.; Hofmann, W.J.; Rieker, R.J.; Penzel, R.; Graf, M.; Otto, H.F. Beta-catenin accumulation and mutation of the CTNNB1 gene in hepatoblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1999, 25, 399-402.

- de La Coste, A.; Romagnolo, B.; Billuart, P.; Renard, C.A.; Buendia, M.A.; Soubrane, O.; Fabre, M.; Chelly, J.; Beldjord, C.; Kahn, A.; et al. Somatic mutations of the beta-catenin gene are frequent in mouse and human hepatocellular carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 8847-8851. [CrossRef]

- Jeng, Y.M.; Wu, M.Z.; Mao, T.L.; Chang, M.H.; Hsu, H.C. Somatic mutations of beta-catenin play a crucial role in the tumorigenesis of sporadic hepatoblastoma. Cancer Lett 2000, 152, 45-51. [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.L.; Liu, S.; Yan, W.W.; Dong, B. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling as a useful therapeutic target in hepatoblastoma. Biosci Rep 2019, 39. [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, K.; Roberts, L.R.; Aderca, I.N.; Dong, X.; Qian, C.; Murphy, L.M.; Nagorney, D.M.; Burgart, L.J.; Roche, P.C.; Smith, D.I.; et al. Mutational spectrum of beta-catenin, AXIN1, and AXIN2 in hepatocellular carcinomas and hepatoblastomas. Oncogene 2002, 21, 4863-4871. [CrossRef]

- Woodfield, S.E.; Shi, Y.; Patel, R.H.; Jin, J.; Major, A.; Sarabia, S.F.; Starosolski, Z.; Zorman, B.; Gupta, S.S.; Chen, Z.; et al. A Novel Cell Line Based Orthotopic Xenograft Mouse Model That Recapitulates Human Hepatoblastoma. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 17751. [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Denkhaus, D.; Albrecht, S.; Leuschner, I.; von Schweinitz, D.; Pietsch, T. Childhood hepatoblastomas frequently carry a mutated degradation targeting box of the beta-catenin gene. Cancer Res 1999, 59, 269-273.

- Marayati, R.; Julson, J.R.; Bownes, L.V.; Quinn, C.H.; Hutchins, S.C.; Williams, A.P.; Markert, H.R.; Beierle, A.M.; Stewart, J.E.; Hjelmeland, A.B.; et al. Metastatic human hepatoblastoma cells exhibit enhanced tumorigenicity, invasiveness and a stem cell-like phenotype. J Pediatr Surg 2022, 57, 1018-1025. [CrossRef]

- Tokiwa, T.; Doi, I.; Sato, J. Preparation of single cell suspensions from hepatoma cells in culture. Acta Med Okayama 1975, 29, 147-150.

- Pietsch, T.; Fonatsch, C.; Albrecht, S.; Maschek, H.; Wolf, H.K.; von Schweinitz, D. Characterization of the continuous cell line HepT1 derived from a human hepatoblastoma. Lab Invest 1996, 74, 809-818.

- Weber, R.G.; Pietsch, T.; von Schweinitz, D.; Lichter, P. Characterization of genomic alterations in hepatoblastomas. A role for gains on chromosomes 8q and 20 as predictors of poor outcome. Am J Pathol 2000, 157, 571-578. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.T.; Rakheja, D.; Hung, J.Y.; Hornsby, P.J.; Tabaczewski, P.; Malogolowkin, M.; Feusner, J.; Miskevich, F.; Schultz, R.; Tomlinson, G.E. Establishment and characterization of a cancer cell line derived from an aggressive childhood liver tumor. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009, 53, 1040-1047. [CrossRef]

- Scheil, S.; Hagen, S.; Bruderlein, S.; Leuschner, I.; Behnisch, W.; Moller, P. Two novel in vitro human hepatoblastoma models, HepU1 and HepU2, are highly characteristic of fetal-embryonal differentiation in hepatoblastoma. Int J Cancer 2003, 105, 347-352. [CrossRef]

- Manchester, K.M.; Warren, D.J.; Erlandson, R.A.; Wheatley, J.M.; La Quaglia, M.P. Establishment and characterization of a novel hepatoblastoma-derived cell line. J Pediatr Surg 1995, 30, 553-558. [CrossRef]

- Kanno, S.; Tsunoda, Y.; Shibusawa, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Okamoto, S.; Matsumura, M.; Gomi, A.; Suzuki, M.; Iijima, T.; Yatsuzuka, M. [Establishment of a human hepatoblastoma (immature type) cell line OHR]. Hum Cell 1989, 2, 211.

- Hayashi, S.; Fujita, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Akita, M.; Satomi, A. Isolation and identification of cancer stem cells from a side population of a human hepatoblastoma cell line, HuH-6 clone-5. Pediatr Surg Int 2011, 27, 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Grobner, S.N.; Worst, B.C.; Weischenfeldt, J.; Buchhalter, I.; Kleinheinz, K.; Rudneva, V.A.; Johann, P.D.; Balasubramanian, G.P.; Segura-Wang, M.; Brabetz, S.; et al. The landscape of genomic alterations across childhood cancers. Nature 2018, 555, 321-327. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Edmonson, M.N.; Gawad, C.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Rusch, M.C.; Easton, J.; et al. Pan-cancer genome and transcriptome analyses of 1,699 paediatric leukaemias and solid tumours. Nature 2018, 555, 371-376. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Sakairi, T.; Goto, K.; Tsuchiya, T.; Sugimoto, J.; Mutai, M. Establishment and characterization of a cell line from a chemically-induced mouse hepatoblastoma. J Vet Med Sci 2000, 62, 263-267. [CrossRef]

- Min, Q.; Molina, L.; Li, J.; Adebayo Michael, A.O.; Russell, J.O.; Preziosi, M.E.; Singh, S.; Poddar, M.; Matz-Soja, M.; Ranganathan, S.; et al. beta-Catenin and Yes-Associated Protein 1 Cooperate in Hepatoblastoma Pathogenesis. Am J Pathol 2019, 189, 1091-1104. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, C.; Wang, L.; Jian, X.; Ma, M.; Li, T.; Hao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J.; et al. Trans-Ancestry Mutation Landscape of Hepatoblastoma Genomes in Children. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 669560. [CrossRef]

- Bondoc, A.; Glaser, K.; Jin, K.; Lake, C.; Cairo, S.; Geller, J.; Tiao, G.; Aronow, B. Identification of distinct tumor cell populations and key genetic mechanisms through single cell sequencing in hepatoblastoma. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 1049. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Davidoff, A.M.; Murphy, A.J. From preneoplastic lesion to heterogenous tumor: recent insights into hepatoblastoma biology and therapeutic opportunities. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 198. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Chen, F.; Gong, D.; Zeng, L.; Xiang, D.; He, Y.; Chen, L.; Yan, J.; Zhang, S. Establishment of childhood hepatoblastoma xenografts and evaluation of the anti-tumour effects of anlotinib, oxaliplatin and sorafenib. Pediatr Surg Int 2022, 38, 465-472. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, T.Z. Immune exclusion in hepatoblastoma: Is beta-catenin to blame again? J Hepatol 2025, 83, 286-289. [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.; Guillorit, H.; Mora Charrot, L.; Laborde, R.; Dugot-Senant, N.; Izotte, J.; Rousseau, B.; Grosset, C.F. Design of a Neonatal Orthotopic Metastatic Xenograft Model of Hepatoblastoma in Mice. Oncology 2025, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Munter, D.; de Faria, F.W.; Richter, M.; Aranda-Pardos, I.; Hotfilder, M.; Walter, C.; Paga, E.; Inserte, C.; Albert, T.K.; Roy, R.; et al. Multiomic analysis uncovers a continuous spectrum of differentiation and Wnt-MDK-driven immune evasion in hepatoblastoma. J Hepatol 2025, 83, 367-382. [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Jin, C.; Dong, Q. Intratumoral Heterogeneity and Immune Microenvironment in Hepatoblastoma Revealed by Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. J Cell Mol Med 2025, 29, e70482. [CrossRef]

- Krijgsman, D.; Kraaier, L.; Verdonschot, M.; Schubert, S.; Leusen, J.; Duiker, E.; de Kleine, R.; de Meijer, V.; de Krijger, R.; Zsiros, J.; et al. Hepatoblastoma exhibits a predominantly myeloid immune landscape and reveals opportunities for macrophage targeted immunotherapy. BioRxiv 2023.

- Eichenmuller, M.; Trippel, F.; Kreuder, M.; Beck, A.; Schwarzmayr, T.; Haberle, B.; Cairo, S.; Leuschner, I.; von Schweinitz, D.; Strom, T.M.; et al. The genomic landscape of hepatoblastoma and their progenies with HCC-like features. J Hepatol 2014, 61, 1312-1320. [CrossRef]

- Nagae, G.; Yamamoto, S.; Fujita, M.; Fujita, T.; Nonaka, A.; Umeda, T.; Fukuda, S.; Tatsuno, K.; Maejima, K.; Hayashi, A.; et al. Genetic and epigenetic basis of hepatoblastoma diversity. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5423. [CrossRef]

- Pire, A.; Hirsch, T.Z.; Morcrette, G.; Imbeaud, S.; Gupta, B.; Pilet, J.; Cornet, M.; Fabre, M.; Guettier, C.; Branchereau, S.; et al. Mutational signature, cancer driver genes mutations and transcriptomic subgroups predict hepatoblastoma survival. Eur J Cancer 2024, 200, 113583. [CrossRef]

- Armengol, C.; Cairo, S.; Fabre, M.; Buendia, M.A. Wnt signaling and hepatocarcinogenesis: the hepatoblastoma model. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2011, 43, 265-270. [CrossRef]

- Buendia, M.A. Genetic alterations in hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma: common and distinctive aspects. Med Pediatr Oncol 2002, 39, 530-535. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Terrada, D.; Gunaratne, P.H.; Adesina, A.M.; Pulliam, J.; Hoang, D.M.; Nguyen, Y.; Mistretta, T.A.; Margolin, J.; Finegold, M.J. Histologic subtypes of hepatoblastoma are characterized by differential canonical Wnt and Notch pathway activation in DLK+ precursors. Hum Pathol 2009, 40, 783-794. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, B.T.; Tamai, K.; He, X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell 2009, 17, 9-26. [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Calvisi, D.F.; Ranganathan, S.; Cigliano, A.; Zhou, L.; Singh, S.; Jiang, L.; Fan, B.; Terracciano, L.; Armeanu-Ebinger, S.; et al. Activation of beta-catenin and Yap1 in human hepatoblastoma and induction of hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 690-701. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, J.; Mandel, J.A.; Zhang, W.; Schwalbe, M.; Gorka, J.; Liu, Y.; Marburger, B.; Wang, J.; Ranganathan, S.; et al. Patient-Derived Mutant Forms of NFE2L2/NRF2 Drive Aggressive Murine Hepatoblastomas. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 12, 199-228. [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Han, Z.; Fang, F.; Chen, L. Yap Expression Is Closely Related to Tumor Angiogenesis and Poor Prognosis in Hepatoblastoma. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2022, 41, 929-939. [CrossRef]

- Kurahashi, H.; Takami, K.; Oue, T.; Kusafuka, T.; Okada, A.; Tawa, A.; Okada, S.; Nishisho, I. Biallelic inactivation of the APC gene in hepatoblastoma. Cancer Res 1995, 55, 5007-5011.

- Li, H.; Wolfe, A.; Septer, S.; Edwards, G.; Zhong, X.; Abdulkarim, A.B.; Ranganathan, S.; Apte, U. Deregulation of Hippo kinase signalling in human hepatic malignancies. Liver Int 2012, 32, 38-47. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.O.; Camargo, F.D. Hippo signalling in the liver: role in development, regeneration and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 19, 297-312. [CrossRef]

- Watt, K.I.; Judson, R.; Medlow, P.; Reid, K.; Kurth, T.B.; Burniston, J.G.; Ratkevicius, A.; De Bari, C.; Wackerhage, H. Yap is a novel regulator of C2C12 myogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010, 393, 619-624. [CrossRef]

- Aretz, S.; Koch, A.; Uhlhaas, S.; Friedl, W.; Propping, P.; von Schweinitz, D.; Pietsch, T. Should children at risk for familial adenomatous polyposis be screened for hepatoblastoma and children with apparently sporadic hepatoblastoma be screened for APC germline mutations? Pediatr Blood Cancer 2006, 47, 811-818. [CrossRef]

- Oda, H.; Imai, Y.; Nakatsuru, Y.; Hata, J.; Ishikawa, T. Somatic mutations of the APC gene in sporadic hepatoblastomas. Cancer Res 1996, 56, 3320-3323.

- Yang, A.; Sisson, R.; Gupta, A.; Tiao, G.; Geller, J.I. Germline APC mutations in hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018, 65. [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Weber, N.; Waha, A.; Hartmann, W.; Denkhaus, D.; Behrens, J.; Birchmeier, W.; von Schweinitz, D.; Pietsch, T. Mutations and elevated transcriptional activity of conductin (AXIN2) in hepatoblastomas. J Pathol 2004, 204, 546-554. [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Kusafuka, T.; Udatsu, Y.; Okada, A. Sequence variants of the Axin gene in hepatoblastoma. Hepatol Res 2003, 25, 174-179. [CrossRef]

- Iolascon, A.; Giordani, L.; Moretti, A.; Basso, G.; Borriello, A.; Della Ragione, F. Analysis of CDKN2A, CDKN2B, CDKN2C, and cyclin Ds gene status in hepatoblastoma. Hepatology 1998, 27, 989-995. [CrossRef]

- Shim, Y.H.; Park, H.J.; Choi, M.S.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.J.; Jang, J.J.; Yu, E. Hypermethylation of the p16 gene and lack of p16 expression in hepatoblastoma. Mod Pathol 2003, 16, 430-436. [CrossRef]

- Kerins, M.J.; Ooi, A. A catalogue of somatic NRF2 gain-of-function mutations in cancer. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 12846. [CrossRef]

- Itoh, K.; Mimura, J.; Yamamoto, M. Discovery of the negative regulator of Nrf2, Keap1: a historical overview. Antioxid Redox Signal 2010, 13, 1665-1678. [CrossRef]

- Fukutomi, T.; Takagi, K.; Mizushima, T.; Ohuchi, N.; Yamamoto, M. Kinetic, thermodynamic, and structural characterizations of the association between Nrf2-DLGex degron and Keap1. Mol Cell Biol 2014, 34, 832-846. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Yamamoto, M. Molecular mechanisms activating the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway of antioxidant gene regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2005, 7, 385-394. [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Ohta, T.; Tong, K.I.; Kokubu, A.; Odogawa, R.; Tsuta, K.; Asamura, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Hirohashi, S. Cancer related mutations in NRF2 impair its recognition by Keap1-Cul3 E3 ligase and promote malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 13568-13573. [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, C.; Enriquez, C.; Gonzalez, C.; Aguirre-Martinez, G.; Buc Calderon, P. The Multifaceted Roles of NRF2 in Cancer: Friend or Foe? Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.K.M.; Leprivier, G. The impact of oncogenic RAS on redox balance and implications for cancer development. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 955. [CrossRef]

- Prochownik, E.V.; Li, Y. The ever expanding role for c-Myc in promoting genomic instability. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 1024-1029. [CrossRef]

- Vafa, O.; Wade, M.; Kern, S.; Beeche, M.; Pandita, T.K.; Hampton, G.M.; Wahl, G.M. c-Myc can induce DNA damage, increase reactive oxygen species, and mitigate p53 function: a mechanism for oncogene-induced genetic instability. Mol Cell 2002, 9, 1031-1044. [CrossRef]

- Nault, J.C.; Zucman-Rossi, J. TERT promoter mutations in primary liver tumors. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2016, 40, 9-14. [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.S.; Niu, X.J.; Wang, W.H. Genetic alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma: An update. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 9069-9095. [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.J.; Rube, H.T.; Xavier-Magalhaes, A.; Costa, B.M.; Mancini, A.; Song, J.S.; Costello, J.F. Understanding TERT Promoter Mutations: A Common Path to Immortality. Mol Cancer Res 2016, 14, 315-323. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.; Singh, V.K.; Backerholm, A.; Ogren, L.; Lindberg, M.; Soczek, K.M.; Hoberg, E.; Luijts, T.; Van den Eynden, J.; Falkenberg, M.; et al. Mechanistic basis of atypical TERT promoter mutations. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 9965. [CrossRef]

- Croci, O.; De Fazio, S.; Biagioni, F.; Donato, E.; Caganova, M.; Curti, L.; Doni, M.; Sberna, S.; Aldeghi, D.; Biancotto, C.; et al. Transcriptional integration of mitogenic and mechanical signals by Myc and YAP. Genes Dev 2017, 31, 2017-2022. [CrossRef]

- Ibar, C.; Irvine, K.D. Integration of Hippo-YAP Signaling with Metabolism. Dev Cell 2020, 54, 256-267. [CrossRef]

- Rennoll, S.; Yochum, G. Regulation of MYC gene expression by aberrant Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer. World J Biol Chem 2015, 6, 290-300. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, J.; Ou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Weng, W.; Pan, Q.; Sun, F. Mutual interaction between YAP and c-Myc is critical for carcinogenesis in liver cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013, 439, 167-172. [CrossRef]

- Yochum, G.S.; Sherrick, C.M.; Macpartlin, M.; Goodman, R.H. A beta-catenin/TCF-coordinated chromatin loop at MYC integrates 5' and 3' Wnt responsive enhancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 145-150. [CrossRef]

- Yen, T.; Stanich, P.P.; Axell, L.; Patel, S.G. APC-Associated Polyposis Conditions. In GeneReviews((R)), Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; Seattle (WA), 1993.

- Shen, G.; Shen, H.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Q.; Liu, H. DNA methylation in Hepatoblastoma-a literature review. Ital J Pediatr 2020, 46, 113. [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.Y.; Sharpless, N.E. The regulation of INK4/ARF in cancer and aging. Cell 2006, 127, 265-275. [CrossRef]

- LaPak, K.M.; Burd, C.E. The molecular balancing act of p16(INK4a) in cancer and aging. Mol Cancer Res 2014, 12, 167-183. [CrossRef]

- Engeland, K. Cell cycle regulation: p53-p21-RB signaling. Cell Death Differ 2022, 29, 946-960. [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.; Petreaca, B.; Petreaca, R. Frequent homozygous deletions of the CDKN2A locus in somatic cancer tissues. Mutat Res 2019, 815, 30-40. [CrossRef]

- Randle, D.H.; Zindy, F.; Sherr, C.J.; Roussel, M.F. Differential effects of p19(Arf) and p16(Ink4a) loss on senescence of murine bone marrow-derived preB cells and macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 9654-9659. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.P.; Zhou, Y.L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, J.J.; Li, J.H.; Li, X.Y.; Li, C.Y.; Lou, Y.J.; Mai, W.Y.; et al. CDKN2A deletions are associated with poor outcomes in 101 adults with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Hematol 2021, 96, 312-319. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Nakajima, R.; Shirasawa, M.; Fikriyanti, M.; Zhao, L.; Iwanaga, R.; Bradford, A.P.; Kurayoshi, K.; Araki, K.; Ohtani, K. Expanding Roles of the E2F-RB-p53 Pathway in Tumor Suppression. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S. The mutational landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol 2015, 21, 220-229. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Shen, W. ARID1A mutations in cancer development: mechanism and therapy. Carcinogenesis 2023, 44, 197-208. [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R. ARID1A loss in cancer: Towards a mechanistic understanding. Pharmacol Ther 2018, 190, 15-23. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Tang, C. The Role of ARID1A in Tumors: Tumor Initiation or Tumor Suppression? Front Oncol 2021, 11, 745187. [CrossRef]

- Orlando, K.A.; Nguyen, V.; Raab, J.R.; Walhart, T.; Weissman, B.E. Remodeling the cancer epigenome: mutations in the SWI/SNF complex offer new therapeutic opportunities. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2019, 19, 375-391. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhou, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Ren, X.; Liu, J.; Kuang, M.; et al. Intratumoral erythroblastic islands restrain anti-tumor immunity in hepatoblastoma. Cell Rep Med 2023, 4, 101044. [CrossRef]

- Sakairi, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Goto, K.; Okada, M.; Kusakabe, M.; Tsuchiya, T.; Sugimoto, J.; Sano, F.; Mutai, M.; Morohashi, T. Immunohistochemical characterization of hepatoblastomas in B6C3F1 mice treated with diethylnitrosamine and sodium phenobarbital. J Vet Med Sci 2001, 63, 1121-1125. [CrossRef]

- Sakairi, T.; Okada, M.; Ikeda, I.; Utsumi, H.; Kohge, S.; Sugimoto, J.; Sano, F.; Takagi, S. Evaluation of gene expression related to hepatic cell maturation and differentiation in a chemically induced mouse hepatoblastoma cell line. Exp Mol Pathol 2007, 83, 419-427. [CrossRef]

- Aleksic, K.; Lackner, C.; Geigl, J.B.; Schwarz, M.; Auer, M.; Ulz, P.; Fischer, M.; Trajanoski, Z.; Otte, M.; Speicher, M.R. Evolution of genomic instability in diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Hepatology 2011, 53, 895-904. [CrossRef]

- Connor, F.; Rayner, T.F.; Aitken, S.J.; Feig, C.; Lukk, M.; Santoyo-Lopez, J.; Odom, D.T. Mutational landscape of a chemically-induced mouse model of liver cancer. J Hepatol 2018, 69, 840-850. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Lim, S.G.; Soo, R.; Hsieh, W.S.; Guo, J.Y.; Putti, T.; Tao, Q.; Soong, R.; Goh, B.C. Lack of somatic mutations in EGFR tyrosine kinase domain in hepatocellular and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2006, 16, 73-74. [CrossRef]

- Prior, I.A.; Hood, F.E.; Hartley, J.L. The Frequency of Ras Mutations in Cancer. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 2969-2974. [CrossRef]

- Tannapfel, A.; Sommerer, F.; Benicke, M.; Katalinic, A.; Uhlmann, D.; Witzigmann, H.; Hauss, J.; Wittekind, C. Mutations of the BRAF gene in cholangiocarcinoma but not in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2003, 52, 706-712. [CrossRef]

- Klaunig, J.E.; Weghorst, C.M.; Pereira, M.A. Effect of phenobarbital on diethylnitrosamine and dimethylnitrosamine induced hepatocellular tumors in male B6C3F1 mice. Cancer Lett 1988, 42, 133-139. [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, L.R.; Otero, P.A.; Sharma, L.; D'Souza, S.; Dolezal, J.M.; David, S.; Lu, J.; Lamm, L.; Basantani, M.; Zhang, P.; et al. Abnormal lipid processing but normal long-term repopulation potential of myc-/- hepatocytes. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 30379-30395. [CrossRef]

- Baena, E.; Gandarillas, A.; Vallespinos, M.; Zanet, J.; Bachs, O.; Redondo, C.; Fabregat, I.; Martinez, A.C.; de Alboran, I.M. c-Myc regulates cell size and ploidy but is not essential for postnatal proliferation in liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 7286-7291. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.A.; Schorl, C.; Patel, A.; Sedivy, J.M.; Gruppuso, P.A. Postnatal liver growth and regeneration are independent of c-myc in a mouse model of conditional hepatic c-myc deletion. BMC Physiol 2012, 12, 1. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xiang, Y.; Potter, J.; Dinavahi, R.; Dang, C.V.; Lee, L.A. Conditional deletion of c-myc does not impair liver regeneration. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 5608-5612. [CrossRef]

- Dolezal, J.M.; Wang, H.; Kulkarni, S.; Jackson, L.; Lu, J.; Ranganathan, S.; Goetzman, E.S.; Bharathi, S.S.; Beezhold, K.; Byersdorfer, C.A.; et al. Sequential adaptive changes in a c-Myc-driven model of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 10068-10086. [CrossRef]

- Levens, D. Cellular MYCro economics: Balancing MYC function with MYC expression. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2013, 3. [CrossRef]

- Shachaf, C.M.; Kopelman, A.M.; Arvanitis, C.; Karlsson, A.; Beer, S.; Mandl, S.; Bachmann, M.H.; Borowsky, A.D.; Ruebner, B.; Cardiff, R.D.; et al. MYC inactivation uncovers pluripotent differentiation and tumour dormancy in hepatocellular cancer. Nature 2004, 431, 1112-1117. [CrossRef]

- Soucek, L.; Evan, G.I. The ups and downs of Myc biology. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2010, 20, 91-95. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Stevens, T.; Knapp, J.; Lu, J.; Prochownik, E.V. MYC Binding Near Transcriptional End Sites Regulates Basal Gene Expression, Read-Through Transcription, and Intragenic Contacts. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, 12, e14601. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.H. The ultrasonographic appearance of cystic hepatoblastoma. Radiology 1981, 138, 141-143. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Wong, K.; Nathan, P.C.; Shaikh, F.; Ngan, B.Y.; Sayed, B.A.; Doria, A.S. A Malignant Hepatoblastoma Mimicking a Benign Mesenchymal Hamartoma: Lessons Learned. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2023, 45, e530-e533. [CrossRef]

- Kreuger, I.Z.M.; Slieker, R.C.; van Groningen, T.; van Doorn, R. Therapeutic Strategies for Targeting CDKN2A Loss in Melanoma. J Invest Dermatol 2023, 143, 18-25 e11. [CrossRef]

- Witkiewicz, A.K.; Knudsen, K.E.; Dicker, A.P.; Knudsen, E.S. The meaning of p16(ink4a) expression in tumors: functional significance, clinical associations and future developments. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 2497-2503. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Dolezal, J.M.; Wang, H.; Jackson, L.; Lu, J.; Frodey, B.P.; Dosunmu-Ogunbi, A.; Li, Y.; Fromherz, M.; Kang, A.; et al. Ribosomopathy-like properties of murine and human cancers. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0182705. [CrossRef]

- Lagopati, N.; Belogiannis, K.; Angelopoulou, A.; Papaspyropoulos, A.; Gorgoulis, V. Non-Canonical Functions of the ARF Tumor Suppressor in Development and Tumorigenesis. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan, E.A.; Wallis, R.; Mossa, F.; Bishop, C.L. The paradox of senescent-marker positive cancer cells: challenges and opportunities. NPJ Aging 2024, 10, 41. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, E.L.; Wadhwa, R.; Kaul, S.C. Senescence and immortalization of human cells. Biogerontology 2000, 1, 103-121. [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, T.; Ohata, H.; Sato, A.; Yamawaki, K.; Enomoto, T.; Okamoto, K. Tumor-derived spheroids: Relevance to cancer stem cells and clinical applications. Cancer Sci 2017, 108, 283-289. [CrossRef]

- Elster, J.D.; McGuire, T.F.; Lu, J.; Prochownik, E.V. Rapid in vitro derivation of endothelium directly from human cancer cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e77675. [CrossRef]

- Sajithlal, G.B.; McGuire, T.F.; Lu, J.; Beer-Stolz, D.; Prochownik, E.V. Endothelial-like cells derived directly from human tumor xenografts. Int J Cancer 2010, 127, 2268-2278. [CrossRef]

- Testa, U.; Pelosi, E.; Castelli, G. Endothelial Progenitors in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1263, 85-115. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Flaherty, P. Assay Methods. Protocol: Endothelial Cell Tube Formation Assay. 2013.

- Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.; Xiong, F.; Zhang, S.; Gong, Z.; Li, X.; Cao, K.; Deng, H.; He, Y.; et al. The role of microenvironment in tumor angiogenesis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2020, 39, 204. [CrossRef]

- Aird, W.C. Endothelial cell heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012, 2, a006429. [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.M.; Chen, S.H.; Rodor, J.; de Rooij, L.; Baker, A.H.; Carmeliet, P. Deciphering endothelial heterogeneity in health and disease at single-cell resolution: progress and perspectives. Cardiovasc Res 2023, 119, 6-27. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Gao, R.R.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, J.; Chen, Q. Dissecting endothelial cell heterogeneity with new tools. Cell Regen 2025, 14, 10. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Kim, K.; Sheng, Y.; Cho, J.; Qian, Z.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Hu, G.; Pan, D.; Malik, A.B.; Hu, G. YAP Controls Endothelial Activation and Vascular Inflammation Through TRAF6. Circ Res 2018, 123, 43-56. [CrossRef]

- Quan, Y.; Shan, X.; Hu, M.; Jin, P.; Ma, J.; Fan, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Fan, X.; Gong, Y.; et al. YAP inhibition promotes endothelial cell differentiation from pluripotent stem cell through EC master transcription factor FLI1. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2022, 163, 81-96. [CrossRef]

- Musick, S.R.; Smith, M.; Rouster, A.S.; Babiker, H.M. Hepatoblastoma. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL), 2025.

- Schady, D.A.; Roy, A.; Finegold, M.J. Liver tumors in children with metabolic disorders. Transl Pediatr 2015, 4, 290-303. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Xin, B.; Watanabe, K.; Ooshio, T.; Fujii, K.; Chen, X.; Okada, Y.; Abe, H.; Taguchi, Y.; Miyokawa, N.; et al. Oncogenic Determination of a Broad Spectrum of Phenotypes of Hepatocyte-Derived Mouse Liver Tumors. Am J Pathol 2017, 187, 2711-2725. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.F.; Carter, A.M.; Kostova, K.K.; Woodruff, J.F.; Crowley, D.; Bronson, R.T.; Haigis, K.M.; Jacks, T. Complete deletion of Apc results in severe polyposis in mice. Oncogene 2010, 29, 1857-1864. [CrossRef]

- Donehower, L.A.; Harvey, M.; Slagle, B.L.; McArthur, M.J.; Montgomery, C.A., Jr.; Butel, J.S.; Bradley, A. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature 1992, 356, 215-221. [CrossRef]

- Pedraza-Farina, L.G. Mechanisms of oncogenic cooperation in cancer initiation and metastasis. Yale J Biol Med 2006, 79, 95-103.

- Pelengaris, S.; Khan, M.; Evan, G.I. Suppression of Myc-induced apoptosis in beta cells exposes multiple oncogenic properties of Myc and triggers carcinogenic progression. Cell 2002, 109, 321-334. [CrossRef]

- Regua, A.T.; Arrigo, A.; Doheny, D.; Wong, G.L.; Lo, H.W. Transgenic mouse models of breast cancer. Cancer Lett 2021, 516, 73-83. [CrossRef]

- Strasser, A.; O'Connor, L.; Huang, D.C.; O'Reilly, L.A.; Stanley, M.L.; Bath, M.L.; Adams, J.M.; Cory, S.; Harris, A.W. Lessons from bcl-2 transgenic mice for immunology, cancer biology and cell death research. Behring Inst Mitt 1996, 101-117.

- Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. The multistep nature of cancer. Trends Genet 1993, 9, 138-141. [CrossRef]

- Benanti, J.A.; Wang, M.L.; Myers, H.E.; Robinson, K.L.; Grandori, C.; Galloway, D.A. Epigenetic down-regulation of ARF expression is a selection step in immortalization of human fibroblasts by c-Myc. Mol Cancer Res 2007, 5, 1181-1189. [CrossRef]

- Chalak, M.; Hesaraki, M.; Mirbahari, S.N.; Yeganeh, M.; Abdi, S.; Rajabi, S.; Hemmatzadeh, F. Cell Immortality: In Vitro Effective Techniques to Achieve and Investigate Its Applications and Challenges. Life (Basel) 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Kerai, P.; Lleonart, M.; Bernard, D.; Cigudosa, J.C.; Peters, G.; Carnero, A.; Beach, D. Immortalization of primary human prostate epithelial cells by c-Myc. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 2179-2185. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, W.C. Immortalization and transformation of human cells. Mol Cells 2002, 13, 351-361.

- Ko, A.; Han, S.Y.; Choi, C.H.; Cho, H.; Lee, M.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Song, J.S.; Hong, K.M.; Lee, H.W.; Hewitt, S.M.; et al. Oncogene-induced senescence mediated by c-Myc requires USP10 dependent deubiquitination and stabilization of p14ARF. Cell Death Differ 2018, 25, 1050-1062. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mannava, S.; Grachtchouk, V.; Zhuang, D.; Soengas, M.S.; Gudkov, A.V.; Prochownik, E.V.; Nikiforov, M.A. c-Myc depletion inhibits proliferation of human tumor cells at various stages of the cell cycle. Oncogene 2008, 27, 1905-1915. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Walsh, R.; Robinson, K.L.; Burchard, J.; Bartz, S.R.; Cleary, M.; Galloway, D.A.; Grandori, C. Gene expression signature of c-MYC-immortalized human fibroblasts reveals loss of growth inhibitory response to TGFbeta. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 2540-2548. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; van Riggelen, J.; Yetil, A.; Fan, A.C.; Bachireddy, P.; Felsher, D.W. Cellular senescence is an important mechanism of tumor regression upon c-Myc inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 13028-13033. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, D.; Mannava, S.; Grachtchouk, V.; Tang, W.H.; Patil, S.; Wawrzyniak, J.A.; Berman, A.E.; Giordano, T.J.; Prochownik, E.V.; Soengas, M.S.; et al. C-MYC overexpression is required for continuous suppression of oncogene-induced senescence in melanoma cells. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6623-6634. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, J.; Stevens, T.; Roberts, A.; Mandel, J.; Avula, R.; Ma, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Land, C.V.; et al. Premature aging and reduced cancer incidence associated with near-complete body-wide Myc inactivation. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 112830. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Stevens, T.; Lu, J.; Airik, M.; Airik, R.; Prochownik, E.V. Disruption of Multiple Overlapping Functions Following Stepwise Inactivation of the Extended Myc Network. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Buendia, M.A.; Armengol, C.; Cairo, S. Molecular classification of hepatoblastoma and prognostic value of the HB 16-gene signature. Hepatology 2017, 66, 1351-1352. [CrossRef]

- Katzenstein, H.M.; Langham, M.R.; Malogolowkin, M.H.; Krailo, M.D.; Towbin, A.J.; McCarville, M.B.; Finegold, M.J.; Ranganathan, S.; Dunn, S.; McGahren, E.D.; et al. Minimal adjuvant chemotherapy for children with hepatoblastoma resected at diagnosis (AHEP0731): a Children's Oncology Group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019, 20, 719-727. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, D.; Briem-Richter, A.; Sornsakrin, M.; Fischer, L.; Nashan, B.; Ganschow, R. The use of everolimus in pediatric liver transplant recipients: first experience in a single center. Pediatr Transplant 2011, 15, 510-514. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, F.; Henningsen, B.; Lederer, C.; Eichenmuller, M.; Godeke, J.; Muller-Hocker, J.; von Schweinitz, D.; Kappler, R. Rapamycin blocks hepatoblastoma growth in vitro and in vivo implicating new treatment options in high-risk patients. Eur J Cancer 2012, 48, 2442-2450. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Sun, X.; Zhao, H.; Guan, H.; Gao, S.; Zhou, P.K. Double-strand DNA break repair: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. MedComm (2020) 2023, 4, e388. [CrossRef]

- Park, W.S.; Oh, R.R.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, P.J.; Shin, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Park, Y.G.; et al. Nuclear localization of beta-catenin is an important prognostic factor in hepatoblastoma. J Pathol 2001, 193, 483-490. [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, M.; Mo, Y.Y. p53 and c-myc: how does the cell balance "yin" and "yang"? Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 1303. [CrossRef]

- Fontana, R.; Ranieri, M.; La Mantia, G.; Vivo, M. Dual Role of the Alternative Reading Frame ARF Protein in Cancer. Biomolecules 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Hientz, K.; Mohr, A.; Bhakta-Guha, D.; Efferth, T. The role of p53 in cancer drug resistance and targeted chemotherapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 8921-8946. [CrossRef]

- Sklar, M.D.; Prochownik, E.V. Modulation of cis-platinum resistance in Friend erythroleukemia cells by c-myc. Cancer Res 1991, 51, 2118-2123.

- Witkiewicz, A.K.; Ertel, A.; McFalls, J.; Valsecchi, M.E.; Schwartz, G.; Knudsen, E.S. RB-pathway disruption is associated with improved response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2012, 18, 5110-5122. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, L.; Dai, G.; Xia, K.; Liu, G.; Song, Q.; Tao, C.; Gao, T.; Guo, W. Telomerase reverse transcriptase promotes chemoresistance by suppressing cisplatin-dependent apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 7070. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Hu, F.; Liu, X.; Tao, Q. Blockade of telomerase reverse transcriptase enhances chemosensitivity in head and neck cancers through inhibition of AKT/ERK signaling pathways. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 35908-35921. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzin, F.; Benary, U.; Baluapuri, A.; Walz, S.; Jung, L.A.; von Eyss, B.; Kisker, C.; Wolf, J.; Eilers, M.; Wolf, E. Different promoter affinities account for specificity in MYC-dependent gene regulation. Elife 2016, 5. [CrossRef]

- Schuhmacher, M.; Eick, D. Dose-dependent regulation of target gene expression and cell proliferation by c-Myc levels. Transcription 2013, 4, 192-197. [CrossRef]

- Bissig-Choisat, B.; Kettlun-Leyton, C.; Legras, X.D.; Zorman, B.; Barzi, M.; Chen, L.L.; Amin, M.D.; Huang, Y.H.; Pautler, R.G.; Hampton, O.A.; et al. Novel patient-derived xenograft and cell line models for therapeutic testing of pediatric liver cancer. J Hepatol 2016, 65, 325-333. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Knapp, J.; Henchy, C.; Lu, J.; Stevens, T.; Ranganathan, S.; Prochownik, E.V. Gas1-Mediated Suppression of Hepatoblastoma Tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol 2025, 195, 982-994. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.K.; Oh, Y.; Hong, J.; Lee, S.H.; Hur, J.K. Development of CRISPR technology for precise single-base genome editing: a brief review. BMB Rep 2021, 54, 98-105. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, K.; Lai, L. Base editors: development and applications in biomedicine. Front Med 2023, 17, 359-387. [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, A.Y.; Adams, E.W.; Nguyen, M.T.A.; Lek, M.; Isaacs, F.J. Precision multiplexed base editing in human cells using Cas12a-derived base editors. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 5061. [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.; Oberholzer, J.; Occhiodoro, T.; Morel, P.; Lou, J.; Trono, D. Reversible immortalization of human primary cells by lentivector-mediated transfer of specific genes. Mol Ther 2000, 2, 404-414. [CrossRef]

- Wright, W.E.; Pereira-Smith, O.M.; Shay, J.W. Reversible cellular senescence: implications for immortalization of normal human diploid fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol 1989, 9, 3088-3092. [CrossRef]

- Otero-Albiol, D.; Santos-Pereira, J.M.; Lucena-Cacace, A.; Clemente-Gonzalez, C.; Munoz-Galvan, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Carnero, A. Hypoxia-induced immortalization of primary cells depends on Tfcp2L1 expression. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 177. [CrossRef]

- de Jong, Y.P. Mice Engrafted with Human Liver Cells. Semin Liver Dis 2024, 44, 405-415. [CrossRef]

- Grompe, M. Fah Knockout Animals as Models for Therapeutic Liver Repopulation. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017, 959, 215-230. [CrossRef]

- Strom, S.C.; Davila, J.; Grompe, M. Chimeric mice with humanized liver: tools for the study of drug metabolism, excretion, and toxicity. Methods Mol Biol 2010, 640, 491-509. [CrossRef]

- Takeishi, K.; Collin de l'Hortet, A.; Wang, Y.; Handa, K.; Guzman-Lepe, J.; Matsubara, K.; Morita, K.; Jang, S.; Haep, N.; Florentino, R.M.; et al. Assembly and Function of a Bioengineered Human Liver for Transplantation Generated Solely from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Rep 2020, 31, 107711. [CrossRef]

| Name of cell lines(s) | Relevant mutations de-regulated oncogenes, and/or tumor suppressors |

Comments | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MHB-2 and others | H-Ras, B-Raf, EGFR ~20%: Ctnnb1 & Apc mutations in older mice |

DEN/PB-treated mouse*, DEN-induced only resemble HCCs, non-tumorigenic | [62,127,128] |

| BY 1-5, BY21 | β−catenindel90, YAPS127A | Immortalized via Crspr mutagenesis of Cdkn2a | [34] |

| BYN 1-3 | β−catenindel90, YAPS127A, NRF2L30P | Immortalized via Crspr mutagenesis of Cdkn2a | [34] |

| BN 1,2 | β−catenindel90, NRF2L30P | Immortalized via Crspr mutagenesis of Cdkn2a | [35] |

| YN1-3 | YAPS127A, NRF2L30P | Immortalized via Crspr mutagenesis of Cdkn2a | [35] |

| NEJF1,2,3,4,5,6,10 | ABC-MYC | [20] |

| Species | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Human |

|

|

| Mouse |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).