Submitted:

16 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pediatric HBL Patients, FLC Patients, Biliary Atresia Patients and Patient-Derived Cell Lines

2.2. Generation of Primary Cell Lines flc110 and hbl Cells

2.3. Examination of J-PKAc Pathways in HepG2 Cells and Huh6 Cells

2.4. Antibodies

2.5. RNA-Seq Analysis of Tissues from HBL Patients

2.6. Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase-PCR

2.7. Protein Isolation and Western Blotting

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

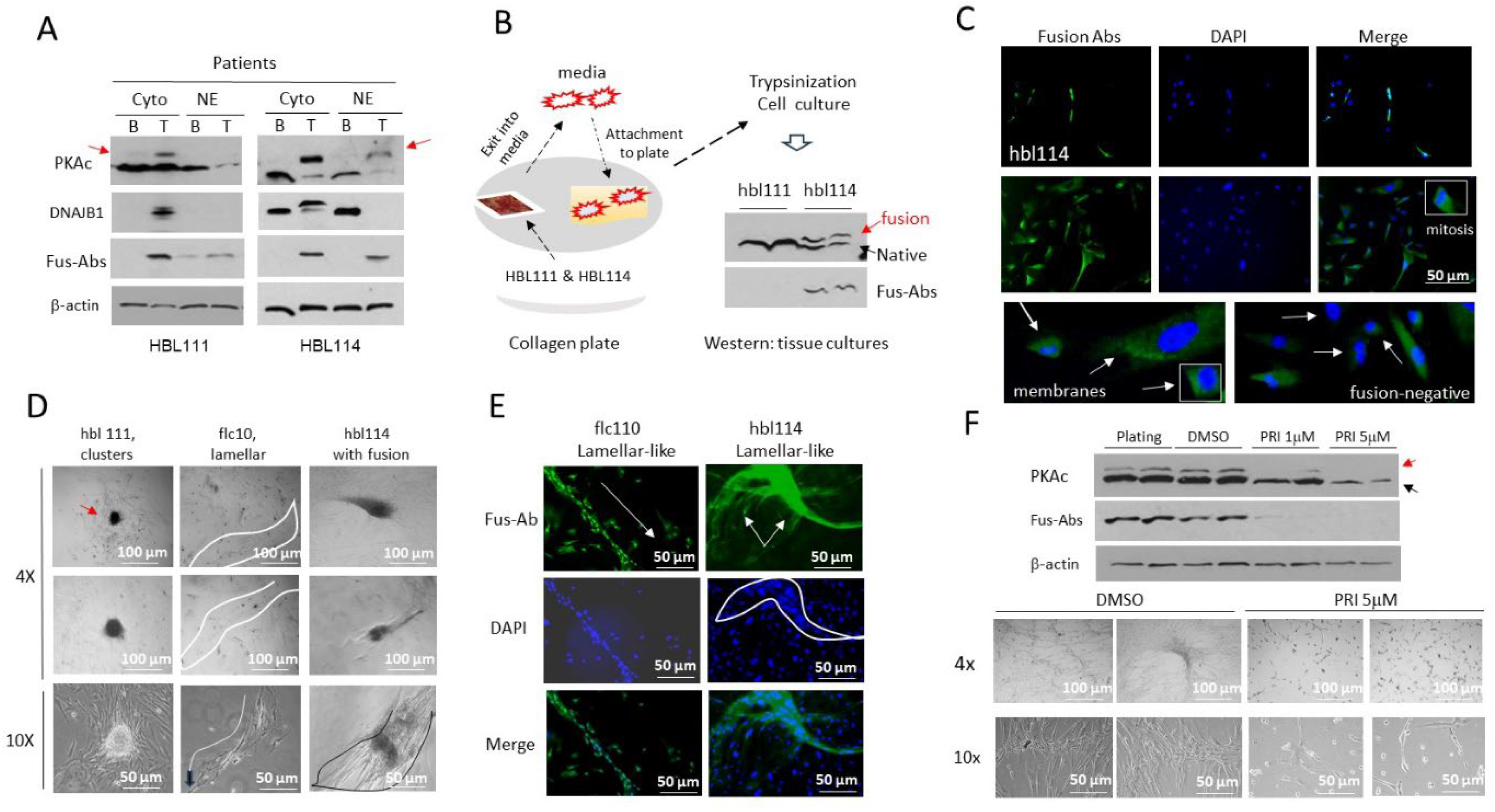

3.1. Identification of the J-PKAc Fusion Kinase in Pediatric Liver Cancers

3.2. RNA-Seq Analysis Showed that J-PKAc-Negative HBL Cells Have High Levels of Complement Cascade and Membrane Attack Complex, While These Pathways Are Reduced in J-PKAc-Positive HBL/HCN-NOS

3.3. The Cell Line flc110 Derived from Fibrolamellar HCC Patient Contains Cells with Disintegrated Fusion-Positive Membrane

3.4. J-PKAc Fusion-Positive HBL/HCN-NOS Tumors Have Increased Activation of Cancer-Related Pathways Compared to Fusion-Negative HBLs

3.5. J-PKAc Increases Expression of Cell Cycle Genes and Reduces Levels of Tumor Suppressors

3.6. Fusion-Positive HBL/HCN-NOS Patients Display Fibrolamellar-Specific Characteristics Including Fibrotic Lamellar-Like Structures

3.7. Members of the Complement Cascade and MAC Are Downregulated in J-PKAc-Positive HBL/HCN-NOS, in Tumors of FLC Patients and in Hepatoblastoma Cells with Ectopic Expression of the J-PKAc

3.8. Alterations of Gene Expression Identified in Fusion-Positive HBLs/HCN-NOS Are Observed in Patients with Fibrolamellar HCC

3.9. J-PKAc Enhances Expression of CEGRs/ALCDs-Dependent Genes in HBL/HCN-NOS Patients

3.10. Ectopic Expression of J-PKAc in Hepatoblastoma Cell Lines HepG2 and Huh6 Enhances ph-S675-b-Catenin and HDAC1-Sp5 Pathways Leading to Alterations Like Those Observed in Fusion-Positive HBLs/HCN-NOSs

3.11. The Cell Line hbl114, Derived from J-PKAc-Positive HBL114, Displays Characteristics of the FLC-Specific Cell Line flc110

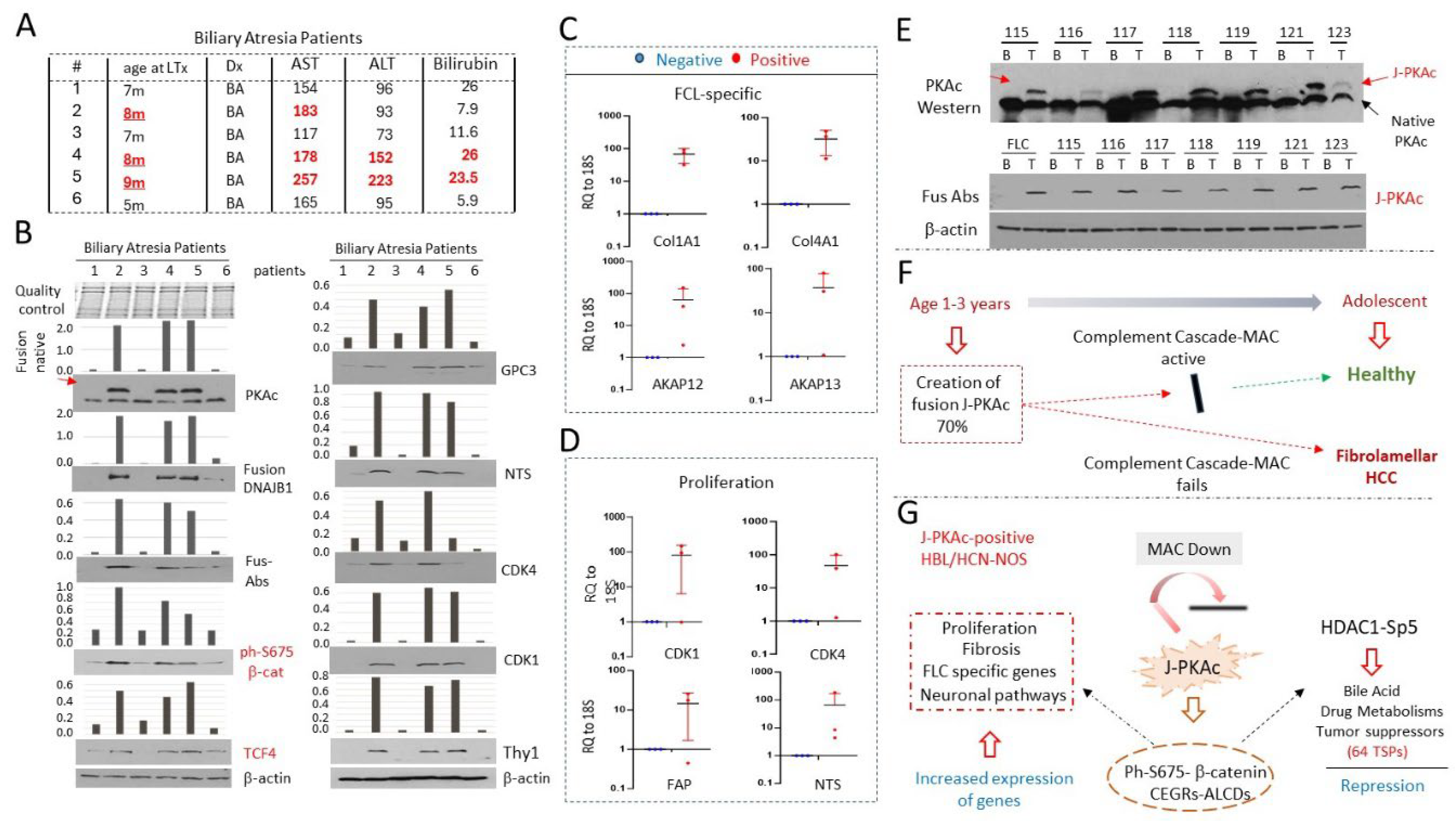

3.12. Livers from Young Patients with Biliary Atresia (BA) Express J-PKAc and Have Transcriptome Profiling which Suggests a Risk for Development of Liver Cancer

3.13. Further Defining the Prevalence of J-PKAc in Pediatric Livers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alshareefy Y, Shen CY, Prekash RJ. Exploring the molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: A state of art review of the current literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2023 Aug;248:154655.

- Lalazar G, Simon SM. Fibrolamellar Carcinoma: Recent Advances and Unresolved Questions on the Molecular Mechanisms. Semin Liver Dis. 2018 Feb;38(1):51-59.

- Honeyman JN, Simon EP, Robine N, Chiaroni-Clarke R, Darcy DG, Lim II, Gleason CE, Murphy JM, Rosenberg BR, Teegan L, Takacs CN, Botero S, Belote R, Germer S, Emde AK, Vacic V, Bhanot U, LaQuaglia MP, Simon SM. Detection of a recurrent DNAJB1-PRKACA chimeric transcript in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Science. 2014 Feb 28;343(6174):1010-4.

- Kastenhuber ER, Lalazar G, Houlihan SL, Tschaharganeh DF, Baslan T, Chen CC, Requena D, Tian S, Bosbach B, Wilkinson JE, Simon SM, Lowe SW. DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion kinase interacts with β-catenin and the liver regenerative response to drive fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 (50):13076-13084.

- Gulati R, Johnston M, Rivas M, Cast A, Kumbaji M, Hanlon M, Lee S, Zhou P, Lake Ch, Scheper E, Min KW, Yoon JH, Karns R, Reid LM, Lopez-Terrada D, Timchenko LT, Parameswaran S, Weirauch MT, Ranganathan S, Bondoc A, Geller J, Tiao G, Shin S, Timchenko NA. β-catenin cancer-enhancing genomic regions axis is involved in the development of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Commun. 2022 6(10):2950-2963.

- Vyas M, Hechtman JF, Zhang Y, Benayed R, Yavas A, Askan G, Shia J, Klimstra DS, Basturk O. DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions occur in oncocytic pancreatic and biliary neoplasms and are not specific for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2020 (4):648-656.

- Ranganathan S, Lopez-Terrada D, Alaggio R. Hepatoblastoma and Pediatric Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Update. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2019 Sep 25:1093526619875228.

- Johnston M, and Timchenko NA. Molecular Signatures of Aggressive Pediatric Liver Cancer. Archives of Stem Cell and Therapy, 2021, 2(1):1-4.

- Johnston ME 2nd, Rivas MP, Nicolle D Gorse A, Gulati R, Kumbaji M, Weirauch MT, Bondoc A, Cairo S, Geller J, Tiao G, Timchenko N. Olaparib Inhibits Tumor Growth of Hepatoblastoma in Patient Derived Xenograft Models. Hepatology. 2021 May 26.

- Gulati R, Hanlon MA, Lutz M, Quitmeyer T, Geller J, Tiao G, Timchenko L, Timchenko NA. Phosphorylation-Mediated Activation of b-Catenin-TCF4-CEGRs/ALCDs Pathway Is an Essential Event in Development of Aggressive Hepatoblastoma. Cancers 2023, 14, 6065.

- Huang G, Jiang H, Lin Y, Wu Y, Cai W, Shi B, Luo Y, Jian Z, Zhou X. lncAKHE enhances cell growth and migration in hepatocellular carcinoma via activation of NOTCH2 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9(5):487.

- Wu WR, Zhang R, Shi XD, Yi C, Xu LB, Liu C. Notch2 is a crucial regulator of self-renewal and tumorigenicity in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2016, 36(1):181-8.

- Fang S, Liu M, Li L, Zhang FF, Li Y, Yan Q, Cui YZ, Zhu YH, Yuan YF, Guan XY. Lymphoid enhancer-binding factor-1 promotes stemness and poor differentiation of hepatocellular carcinoma by directly activating the NOTCH pathway. Oncogene. 2019, 38(21):4061-4074.

- Yoo Y, Park SY, Jo EB, Choi M, Lee KW, Hong D, Lee S, Lee CR, Lee Y, Um JY, Park JB, Seo SW, Choi YL, Kim S, Lee SG, Choi M. Overexpression of Replication-Dependent Histone Signifies a Subset of Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma with Increased Aggressiveness Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13(13):3122.

- Wang J, Hong M, Cheng Y, Wang X, Li D, Chen G, Bao B, Song J, Du X, Yang C, Zheng L, Tong. Targeting c-Myc transactivation by LMNA inhibits tRNA processing essential for malate-aspartate shuttle and tumour progression. Clin Transl Med. 2024 (5):e1680.

- Cedervall J, Zhang Y, Ringvall M, Thulin A, Moustakas A, Jahnen-Dechent W, Siegbahn A, Olsson AK. HRG regulates tumor progression, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and metastasis via platelet-induced signaling in the pre-tumorigenic microenvironment. Angiogenesis. 2013 (4):889-902.

- Zou X, Zhang D, Song, Y Liu S, Long Q, Yao L, Li W, Duan Z, Wu D, Liu L. HRG switches TNFR1-mediated cell survival to apoptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Theranostics. 2020 (23):10434-10447.

- Ma D, Liu P, Wen J, Gu Y, Yang Z, Lan J, Fan H, Liu Z, Guo D. FCN3 inhibits the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma by suppressing SBDS-mediated blockade of the p53 pathway Int J Biol Sci 2023 (2):362-376.

- Liu Z, Lu Q, Zhang Z, Feng Q, Wang X. TMPRSS2 is a tumor suppressor, and its downregulation promotes antitumor immunity and immunotherapy response in lung adenocarcinoma. Respir Res. 2024, 25 (1):238.

- Lv Y, Xie X, Zou G, Kong M, Yang J, Chen J, Xiang B. SOCS2 inhibits hepatoblastoma metastasis via downregulation of the JAK2/STAT5 signal pathway. Sci Rep. 2023, 13(1):21814.

- Zhou SQ, Feng P, Ye ML, Huang SY, He SW, Zhu XH, Chen J, Zhang Q, Li YQ. The E3 ligase NEURL3 suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by promoting vimentin degradation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024, 43(1).

- Kim JW, Marquez CP, Kostyrko K, Koehne AL, Marini K, Simpson DR, Lee AG, Leung SG, Sayles LC, Shrager J, Ferrer I, Paz-Ares L, Gephart MH, Vicent S, Cochran JR, Sweet-Cordero EA. Antitumor activity of an engineered decoy receptor targeting CLCF1-CNTFR signaling in lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2019 (11):1783-1795.

- Zhang Y, Xu P, Park K, Choi Y, Moore DD, Wang L. Orphan receptor small heterodimer partner suppresses tumorigenesis by modulating cyclin D1 expression and cellular proliferation. Hepatology. 2008 (1):289-98.

- Chen W, Lu C, Hong J. TRIM15 Exerts Anti-Tumor Effects Through Suppressing Cancer Cell Invasion in Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Med Sci Monit. 2018; 24:8033-8041.

- Hu X, Villodre ES, Larson R, Rahal OM, Wang X, Gong Y, Song J, Krishnamurthy S, Ueno NT, Tripathy D, Woodward WA, Debeb BG. Decorin-mediated suppression of tumorigenesis, invasion, and metastasis in inflammatory breast cancer. Commun Biol. 2021 Jan 15;4(1):72.

- Li S, Yang H, Li W, Liu JY, Ren LW, Yang YH, Ge BB, Zhang YZ, Fu WQ, Zheng XJ, Du GH, Wang JH. ADH1C inhibits progression of colorectal cancer through the ADH1C/PHGDH /PSAT1/serine metabolic pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022; 43(10):2709-2722.

- Lin YH, Zeng Q, Jia Y, Wang Z, Li L, Hsieh MH, Cheng Q, Pagani CA, Livingston N, Lee J, Zhang Y, Sharma T, Siegwart DJ, Yimlamai D, Levi B, Zhu H. In vivo screening identifies SPP2, a secreted factor that negatively regulates liver regeneration Hepatology. 2023; 78(4):1133-1148.

- Rivas M, Johnston ME 2nd, Gulati R, Kumbaji M, Margues Aguiar TF, Timchenko T, Krepischi A, Shin S, Bondoc A, Tiao G, Geller J, Timchenko N. HDAC1-Dependent Repression of Markers of Hepatocytes and P21 is involved in Development of Pediatric Liver Cancer. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 12(5):1669-1682.

- Gulati R, Lutz M, Hanlon M, Cast A, Karns R, Geller J, Bondoc A, Tiao G, Timchenko L, Timchenko NT. Cellular Origin and Molecular Mechanisms of Lung Metastases in Patients with Aggressive Hepatoblastoma. Hepatol Commun. 2024; 8(2):e0369.

- Garred P, Genster N, Pilely K, Bayarri-Olmos R, Rosbjerg A, Ma YJ, Skjoedt MO. A journey through the lectin pathway of complement-MBL and beyond. Immunol Rev 2016; 274(1):74-97.

- Merle NS & Roumenina LT. The complement system as a target in cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol. 2024 Jul 12:e2350820.

- O’Neill K, Pastar I, Tomic-Canic M, Strbo N. Perforins Expression by Cutaneous Gamma Delta T Cells. Front Immunol. 2020; 11:1839.

- Jane-Wit D, Song G, He L, Jiang Q, Barkestani M, Wang S, Wang Q, Ren P, Fan M, Johnson J, Mullan C. Complement Membrane Attack Complexes Disrupt Proteostasis to Function as Intracellular Alarmins. Res Sq. 2024 Jun 19:rs.3.rs-4504419.

- Spiller OB, Criado-García O, Rodríguez DCS, Morgan BP. Cytokine-mediated up-regulation of CD55 and CD59 protects human hepatoma cells from complement attack. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000, 121(2):234-41.

- Simon EP, Freije CA, Farber BA, Lalazar G, Darcy DG, Honeyman JN, Chiaroni-Clarke R, Dill BD, Molina H, Bhanot UK, La Quaglia MP, Rosenberg BR, Simon SM. Transcriptomic characterization of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Nov 3;112(44):E5916-25. Epub 2015 Oct 21. [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Hazard FK, Zmoos AF, Jahchan N, Chaib H, Garfin PM, Rangaswami A, Snyder MP, Sage J. Genomic analysis of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2015 Jan 1;24(1):50-63. Epub 2014 Aug 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).