Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is now the leading cause of chronic liver disease globally, mirroring the increasing prevalence of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Early detection of hepatic steatosis is vital for cardiometabolic risk assessment; however, conventional imaging is costly and impractical for population screening. This study aimed to develop interpretable machine-learning models to predict ultrasound-detected MASLD using routinely available clinical and biochemical data. Methods: We analyzed data from 644 adults (50% with MASLD on ultrasonography). Preprocessing, imputation, and feature selection were implemented within a single scikit-learn pipeline to avoid information leakage. An Elastic Net–regularized logistic regression identified the top 20 predictors, which were subsequently used across nine supervised machine learning (ML) classifiers. Model performance was evaluated via repeated stratified 5-fold cross-validation (25 resamples) using accuracy, F1 score, sensitivity, specificity, Youden’s J, balanced accuracy, and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC). Interpretability was assessed using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). Results: Participants with MASLD exhibited greater adiposity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia compared with controls [p < 0.05 for body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, glucose, HbA1c, triglycerides). Elastic Net selection highlighted Weight, Ponderal Index, Fibrosis-4 Index (FIB-4), blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/Creatinine ratio, Aspartate Aminotransferase to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI), and Visceral Adiposity Index as the strongest predictors. Logistic Regression and Gradient Boosting achieved the best performance (accuracy = 0.65 ± 0.03; AUROC = 0.71 ± 0.04; balanced accuracy = 0.66 ± 0.06), outperforming rule-based indices such as Fatty Liver Index (FLI) and Hepatic Steatosis Index (HSI) reported in the literature. SHAP analysis confirmed clinically coherent feature effects, with higher anthropometric and hepatic injury indices increasing predicted MASLD probability. Conclusions: Routinely available clinical and biochemical parameters can predict hepatic steatosis with moderate accuracy using transparent, interpretable ML models. Logistic Regression and Gradient Boosting provided the best discrimination and generalizability, offering a pragmatic, low-cost approach for early MASLD screening in primary and metabolic care settings.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Modeling

2.2. Preprocessing and Feature Selection (Single Pipeline)

2.3. Data Splitting and Resampling

2.4. Classifiers

2.5. Evaluation Metrics and Interpretability

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Model Development and Evaluation

3.3. Elastic Net–Based Variable Selection

3.4. Accuracy

3.5. F1 Score

3.6. Sensitivity

3.7. Specificity

3.8. Youden’s J

3.9. AUROC

3.10. Balanced Accuracy

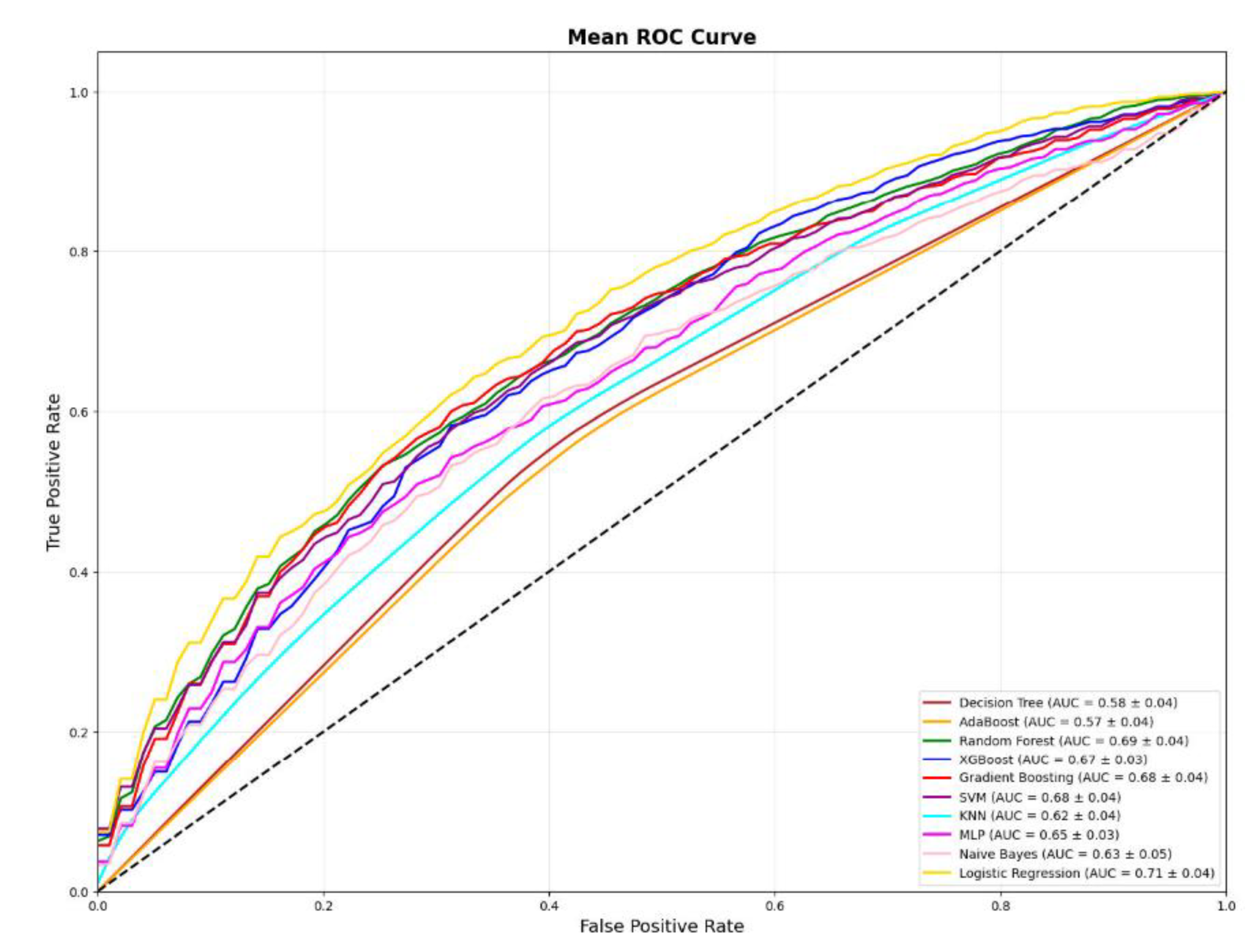

3.11. ROC Visualization

3.12. Predictive Values (PPV/NPV)

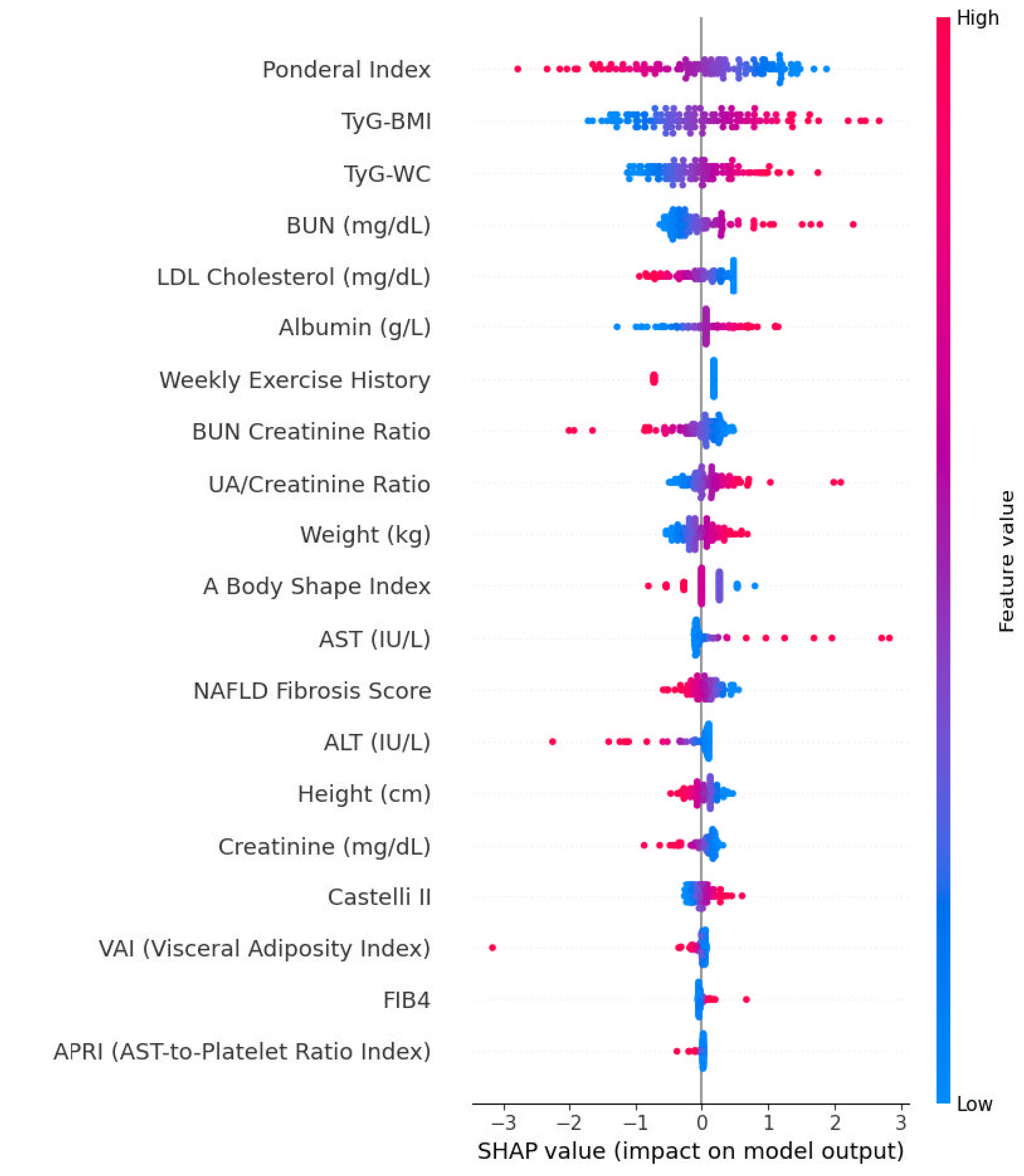

3.13. SHAP Summaries and Directionality

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease |

| ML | Machine learning |

References

- Chan, W. , et al., Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review. JOURNAL OF OBESITY & METABOLIC SYNDROME, 2023. 32(3): p. 197-213.

- Li, Y. , et al., Updated mechanisms of MASLD pathogenesis. LIPIDS IN HEALTH AND DISEASE, 2024. 23(1).

- Hong, S. , et al., From NAFLD to MASLD: When metabolic comorbidity matters. ANNALS OF HEPATOLOGY, 2024. 29(2).

- Zazueta, A. , et al., Alteration of Gut Microbiota Composition in the Progression of Liver Damage in Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MOLECULAR SCIENCES, 2024. 25(8).

- Fan, J. , et al., Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Fatty Liver Disease (Version 2024). JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND TRANSLATIONAL HEPATOLOGY, 2024. 12(11): p. 955-974.

- Lu, H. , et al., Identification of hub gene for the pathogenic mechanism and diagnosis of MASLD by enhanced bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. PLOS ONE, 2025. 20(5).

- DiBattista, J. , et al., Accuracy of Non-invasive Indices for Diagnosing Hepatic Steatosis Compared to Imaging in a Real-World Cohort. DIGESTIVE DISEASES AND SCIENCES, 2022. 67(11): p. 5300-5308.

- Wu, J. , et al., Population-specific cut-off points of fatty liver index for the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis. JOURNAL OF HEPATOLOGY, 2021. 75(3): p. 726-728.

- Su, P. , et al., Comparison of Machine Learning Models and the Fatty Liver Index in Predicting Lean Fatty Liver. DIAGNOSTICS, 2023. 13(8).

- Frey, L. , et al., Use of machine learning for early prediction of short-term mortality in veterans with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. PLOS ONE, 2025. 20(10).

- Chen, H. , et al., Development and validation of machine learning models for MASLD: based on multiple potential screening indicators. FRONTIERS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY, 2025. 15.

- Soliman, R., A. Helmy, and G. Shiha, Precision in Diagnosis of Liver Fibrosis in MASLD: Machine Learning-Based Scores May Be More Accurate Than Conventional NITs. LIVER INTERNATIONAL, 2025. 45(4).

- Huang, D., H. El-Serag, and R. Loomba, Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. NATURE REVIEWS GASTROENTEROLOGY & HEPATOLOGY, 2021. 18(4): p. 223-238.

- Lazarus, J. , et al., A global action agenda for turning the tide on fatty liver disease. HEPATOLOGY, 2024. 79(2): p. 502-523.

- Bedogni, G. , et al., The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC GASTROENTEROLOGY, 2006. 6.

- Alqahtani, S. , et al., Identification and Characterization of Cefazolin-Induced Liver Injury. CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY, 2015. 13(7): p. 1328-+.

- Daghestani, M. , et al., Adverse Effects of Selected Markers on the Metabolic and Endocrine Profiles of Obese Women With and Without PCOS. FRONTIERS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY, 2021. 12.

- Cubillos, G. , et al., Development of a novel deep learning method that transforms tabular input variables into images for the prediction of SLD. SCIENTIFIC REPORTS, 2025. 15(1).

- Lim, D. , et al., Use of Machine Learning to Predict Onset of NAFLD in an All-Comers Cohort-Development and Validation in 2 Large Asian Cohorts. GASTRO HEP ADVANCES, 2024. 3(7): p. 1005-1011.

- Fabbrini, E., S. Sullivan, and S. Klein, Obesity and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Biochemical, Metabolic, and Clinical Implications. HEPATOLOGY, 2010. 51(2): p. 679-689.

- Demirci, S. and S. Sezer, Fatty Liver Index vs. Biochemical-Anthropometric Indices: Diagnosing Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease with Non-Invasive Tools. DIAGNOSTICS, 2025. 15(5).

- Qian, X. , et al., Value of triglyceride glucose-body mass index in predicting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. FRONTIERS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY, 2025. 15.

- Sheng, G. , et al., The usefulness of obesity and lipid-related indices to predict the presence of Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. LIPIDS IN HEALTH AND DISEASE, 2021. 20(1).

- Xuan, Y. , et al., Elevated ALT/AST ratio as a marker for NAFLD risk and severity: insights from a cross-sectional analysis in the United States. FRONTIERS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY, 2024. 15.

- Rigor, J. , et al., Noninvasive fibrosis tools in NAFLD: validation of APRI, BARD, FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score, and Hepamet fibrosis score in a Portuguese population. POSTGRADUATE MEDICINE, 2022. 134(4): p. 435-440.

- Ouzan, D. , et al., Using the FIB-4, automatically calculated, followed by the ELF test in second line to screen primary care patients for liver disease. SCIENTIFIC REPORTS, 2024. 14(1).

- Yang, C. , et al., A Bidirectional Relationship Between Hyperuricemia and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. FRONTIERS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY, 2022. 13.

- Francoz, C. , et al., Hepatorenal Syndrome. CLINICAL JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF NEPHROLOGY, 2019. 14(5): p. 774-781.

- Bucurica, S. , et al., Exploring the Relationship between Lipid Profile, Inflammatory State and 25-OH Vitamin D Serum Levels in Hospitalized Patients. BIOMEDICINES, 2024. 12(8).

- Belalcazar, S. , et al., CONVENTIONAL BIOMARKERS FOR CARDIOVASCULAR RISKS AND THEIR CORRELATION WITH THE CASTELLI RISK INDEX-INDICES AND TG/HDL-C. ARCHIVOS DE MEDICINA, 2020. 20(1): p. 11-22.

- Xiao, L. , et al., Development and Validation of Machine Learning-Based Marker for Early Detection and Prognosis Stratification of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. ADVANCED SCIENCE, 2025. 12(33).

- Verschuren, L. , et al., Development of a novel non-invasive biomarker panel for hepatic fibrosis in MASLD. NATURE COMMUNICATIONS, 2024. 15(1).

- Yu, Y. , et al., Predicting metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease using explainable machine learning methods. SCIENTIFIC REPORTS, 2025. 15(1).

- Koliaki, C. , et al., Metabolically Healthy Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): Navigating the Controversies in Disease Development and Progression. CURRENT OBESITY REPORTS, 2025. 14(1).

- Weng, S. , et al., Prediction of Fatty Liver Disease in a Chinese Population Using Machine-Learning Algorithms. DIAGNOSTICS, 2023. 13(6).

- Collins, G. , et al., TRIPOD plus AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ-BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL, 2024. 385.

| Features | Normal USG | Hepatosteatosis in USG | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 322 (50) | 322 (50) | - |

| Demographic and Anthropometric Characteristics | |||

| Age | 62,36 ± 19,12 [60,26 - 64,46] | 59,81 ± 15,95 [58,06 - 61,56] | 0.004 (mwu) |

| Sex (Female) | 179 (55.59) | 170 (52.8) | 0.477 (chi2) |

| Educational Status | 57 (17.7) | 57 (17.7) | 1.0 (chi2) |

| Smoking | 131 (40.68) | 144 (44.72) | 0.3 (chi2) |

| Height (cm) | 164,19 ± 10,18 [163,08 - 165,31] | 165,91 ± 9,98 [164,82 - 167,01] | 0.043 (mwu) |

| Weight (kg) | 70,43 ± 14,58 [68,83 - 72,03] | 79,82 ± 18,24 [77,82 - 81,82] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 87,71 ± 17,17 [85,83 - 89,59] | 95,65 ± 18,24 [93,65 - 97,65] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Body Mass Index | 26,24 ± 5,77 [25,61 - 26,87] | 29,02 ± 6,57 [28,3 - 29,74] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Weekly Exercise History | 71 (22,05) | 44 (13,66) | 0.005 (chi2) |

| Hemodynamic Parameters | |||

| SBP (mmHg) | 124,29 ± 16,14 [122,52 – 126,06] | 126,64 ± 17,28 [124,75 – 128,54] | 0.026 (mwu) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 72,63 ± 9,73 [71,56 – 73,69] | 75,15 ± 11,1 [73,93 – 76,37] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Heart Rate (beats/min) | 80,35 ± 12,87 [78,94 – 81,76] | 82,67 ± 13,16 [81,23 – 84,11] | 0.031 (mwu) |

| Clinical Comorbidities and Medication Use | |||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 116 (36,02) | 165 (51,24) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Hypertension | 157 (48,76) | 175 (54,35) | 0.156 (chi2) |

| Dyslipidemia | 59 (18,32) | 103 (31,99) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease | 73 (22,67) | 82 (25,47) | 0.407 (chi2) |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 14 (4,35) | 17 (5.28) | 0.581 (chi2) |

| Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (in females) | 1 (0.56) | 2 (1.18) | 0.563 (chi2) |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome | 0 (0) | 5 (1.55) | 0.025 (chi2) |

| Metformin Use | 40 (12,42) | 83 (25,78) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Pioglitazone Use | 3 (0.93) | 4 (1.24) | 0.704 (chi2) |

| SGLT2i Use | 26 (8,07) | 45 (13,98) | 0.017 (chi2) |

| Statin Use | 39 (12,11) | 65 (20,19) | 0.005 (chi2) |

| Hematologic Parameters | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11,12 ± 2,56 [10,84 – 11,4] | 11,81 ± 2,61 [11,52 – 12,09] | <0.001 (t-test) |

| WBC (10³/µL) | 8,41 ± 3,6 [8,01 – 8,8] | 8,82 ± 3,52 [8,43 – 9,2] | 0.11 (mwu) |

| Lymphocyte Count (10³/µL) | 2,16 ± 3,04 [1,83 – 2,5] | 2,1 ± 1,52 [1,93 – 2,27] | 0.004 (mwu) |

| Neutrophil Count (10³/µL) | 5,83 ± 3,34 [5,46 – 6,19] | 5,96 ± 3,35 [5,59 – 6,33] | 0.63 (mwu) |

| Monocyte Count (10³/µL) | 0,74 ± 0,78 [0,66 – 0,83] | 0,79 ± 0,84 [0,69 – 0,88] | 0.339 (mwu) |

| Platelet Count (10³/µL) | 253,55 ± 113,88 [241,07 – 266,04] | 262,55 ± 103,84 [251,16 – 273,93] | 0.29 (mwu) |

| Biochemical Parameters | |||

| Fasting Plasma Glucose (mg/dL) | 126,06 ± 63,27 [119,12 – 133] | 144,47 ± 81,2 [135,57 – 153,37] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 28,06 ± 23,42 [25,49 – 30,63] | 27,79 ± 23,97 [25,16 – 30,42] | 0.71 (mwu) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1,28 ± 1,08 [1,16 – 1,4] | 1,19 ± 0,8 [1,1 – 1,28] | 0.658 (mwu) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m²) | 70,74 ± 34,64 [66,94 – 74,54] | 73,12 ± 33,29 [69,47 – 76,77] | 0.287 (mwu) |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 152,09 ± 52,52 [146,34 – 157,85] | 159,67 ± 54,58 [153,69 – 165,66] | 0.039 (mwu) |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 91,07 ± 39,71 [86,72 – 95,42] | 94,37 ± 40,61 [89,92 – 98,82] | 0.271 (mwu) |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 38,64 ± 14,27 [37,07 – 40,2] | 37,32 ± 13,71 [35,81 – 38,82] | 0.202 (mwu) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 134,36 ± 153,57 [117,53 – 151,2] | 170,91 ± 116,66 [158,12 – 183,7] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| AST (IU/L) | 38,76 ± 87,87 [29,13 – 48,4] | 43,94 ± 93,24 [33,71 – 54,16] | 0.198 (mwu) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 40,6 ± 98,78 [29,77 – 51,43] | 39,87 ± 78,22 [31,3 – 48,45] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| GGT (IU/L) | 66,91 ± 106,53 [55,23 – 78,59] | 88,3 ± 175,22 [69,09 – 107,51] | 0.167 (mwu) |

| HbA1c (%) | 6,51 ± 2,34 [6,26 – 6,77] | 7,11 ± 2,78 [6,81 – 7,41] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Albumin (g/L) | 36,03 ± 5,05 [35,47 – 36,58] | 37,69 ± 4,56 [37,19 – 38,19] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Direct Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0,3 ± 0,64 [0,23 – 0,37] | 0,31 ± 0,56 [0,25 – 0,37] | 0.714 (mwu) |

| Indirect Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0,35 ± 0,27 [0,32 – 0,38] | 0,4 ± 0,45 [0,35 – 0,45] | 0.488 (mwu) |

| TSH (mIU/L) | 2,02 ± 3,1 [1,68 – 2,36] | 2,65 ± 6,72 [1,91 – 3,38] | 0.12 (mwu) |

| Free T4 (ng/dL) | 1,26 ± 0,27 [1,23 – 1,29] | 1,24 ± 0,23 [1,21 – 1,26] | 0.49 (mwu) |

| Uric Acid (mg/dL) | 5,53 ± 2,06 [5,3 – 5,75] | 5,75 ± 1,79 [5,55 – 5,94] | 0.096 (mwu) |

| Ferritin (mg/dL) | 221,65 ± 251,39 [194,09 – 249,21] | 241,63 ± 305,89 [208,1 – 275,17] | 0.227 (mwu) |

| Vitamin B12 (ng/L) | 448,49 ± 294,9 [416,16 – 480,82] | 445,07 ± 269,07 [415,57 – 474,57] | 0.199 (mwu) |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (IU/L) | 111,11 ± 96,62 [100,51 – 121,7] | 107,58 ± 92,81 [97,41 - 117,76] | 0.561 (mwu) |

| Abbreviations: MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease; USG: Ultrasonography; BMI: Body mass index; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; HR: Heart rate; DM: Diabetes mellitus; HTN: Hypertension; DLP: Dyslipidemia; ASCVD: Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CVD: Cerebrovascular disease; PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome; OSA: Obstructive sleep apnea; SGLT2i: Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor; Hb: Hemoglobin; WBC: White blood cell; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transferase; BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG: Triglycerides; HbA1c: Glycated hemoglobin; TSH: Thyroid-stimulating hormone; FT4: Free thyroxine; UA: Uric acid; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; APRI: AST-to-platelet ratio index; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4 index; VAI: Visceral adiposity index; TyG-BMI: Triglyceride-glucose index adjusted for BMI; TyG-WC: Triglyceride-glucose index adjusted for waist circumference; ABSI: A body shape index. | |||

| Features | Normal USG | Hepatosteatosis in USG | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 322 (50) | 322 (50) | - |

| Body Composition Indices | |||

| Waist-to-Height Ratio | 0,54 ± 0,11 [0,52 - 0,55] | 0,58 ± 0,11 [0,57 - 0,59] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| A Body Shape Index | 0,08 ± 0,01 [0,08 - 0,08] | 0,08 ± 0,01 [0,08 - 0,08] | 0.074 (mwu) |

| Body Fat Percentage | 35,63 ± 10,98 [34,43 - 36,84] | 38,08 ± 11,74 [36,8 - 39,37] | 0.006 (t-test) |

| Ponderal Index | 16,13 ± 4,43 [15,65 - 16,62] | 17,59 ± 4,39 [17,11 - 18,07] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Conicity Index | 1,23 ± 0,17 [1,21 - 1,25] | 1,27 ± 0,16 [1,25 - 1,28] | 0,004 (t-test) |

| Relative Fat Mass | 31,84 ± 10,38 [30,7 - 32,97] | 34,4 ± 10,04 [33,3 - 35,5] | 0.002 (t-test) |

| Metabolic Indices | |||

| Triglyceride-Glucose Index | 8,76 ± 0,75 [8,68 - 8,84] | 9,14 ± 0,81 [9,05 - 9,22] | <0.001 (t-test) |

| TyG/HDL Ratio | 4,73 ± 11,37 [3,49 - 5,98] | 5,6 ± 5,85 [4,96 - 6,24] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| AIP (Atherogenic Index of Plasma) | 0,12 ± 0,34 [0,09 - 0,16] | 0,25 ± 0,33 [0,22 - 0,29] | <0.001 (t-test) |

| LAP (Lipid Accumulation Product) | 43,9 ± 84,95 [34,59 - 53,22] | 68,88 ± 62,3 [62,05 - 75,71] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| VAI (Visceral Adiposity Index) | 3,31 ± 7,41 [2,5 - 4,12] | 3,95 ± 4,2 [3,49 - 4,41] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| TyG-BMI | 230,16 ± 55,79 [224,05 - 236,28] | 266,41 ± 71,26 [258,6 - 274,22] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| TyG-WC | 769,58 ± 171 [750,83 - 788,33] | 876,31 ± 195 [854,93 - 897,69] | <0.001 (t-test) |

| TyG-WHtR | 4,7 ± 1,08 [4,58 - 4,82] | 5,29 ± 1,2 [5,16 - 5,42] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Cardiovascular Indices | |||

| Castelli I | 4,41 ± 2,68 [4,12 - 4,7] | 4,7 ± 2,26 [4,46 - 4,95] | 0.004 (mwu) |

| Castelli II | 2,55 ± 1,38 [2,4 - 2,7] | 2,75 ± 1,33 [2,6 - 2,89] | 0.047 (mwu) |

| Non-HDL Cholesterol | 113,46 ± 49,47 [108,03 - 118,88] | 122,36 ± 52,14 [116,64 - 128,07] | 0.02 (mwu) |

| Remnant Cholesterol | 22,39 ± 30,81 [19,01 - 25,77] | 27,99 ± 26,75 [25,06 - 30,92] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Pulse Pressure | 51,66 ± 12,98 [50,24 - 53,09] | 51,49 ± 14,05 [49,95 - 53,03] | 0.783 (mwu) |

| Rate Pressure Product | 9977,79 ± 2025,54 [9755,71 - 10199,87] | 10463,94 ± 2157,03 [10227,45 - 10700,43] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Liver Indices | |||

| De Ritis Ratio | 1,25 ± 0,56 [1,19 - 1,32] | 1,19 ± 0,63 [1,12 - 1,26] | 0.006 (mwu) |

| APRI (AST-to-Platelet Ratio Index) | 0,77 ± 5,61 [0,16 - 1,39] | 0,87 ± 5,69 [0,25 - 1,5] | 0.893 (mwu) |

| FIB4 | 2,23 ± 5,71 [1,6 - 2,85] | 2,43 ± 8,33 [1,52 - 3,35] | 0.088 (mwu) |

| Hepatic Steatosis Index | 36,08 ± 8,07 [35,19 - 36,96] | 39,41 ± 7,95 [38,53 - 40,28] | <0.001 (t-test) |

| NAFLD Fibrosis Score | -0,93 ± 1,99 [-1,15 - -0,71] | -0,88 ± 2,06 [-1,11 - -0,65] | 0.768 (t-test) |

| Albumin-Bilirubin Score | -2,41 ± 0,56 [-2,47 - -2,35] | -2,51 ± 0,59 [-2,57 - -2,44] | 0.003 (mwu) |

| HALP Score | 43,02 ± 54,53 [37,04 - 49] | 44,43 ± 57,84 [38,09 - 50,77] | 0.024 (mwu) |

| Immune/Hematologic Scores | |||

| NLR | 3,79 ± 2,9 [3,47 - 4,11] | 3,64 ± 3,09 [3,3 - 3,98] | 0.16 (mwu) |

| PLR | 158,85 ± 96,2 [148,3 - 169,4] | 148,72 ± 79,59 [139,99 - 157,44] | 0.401 (mwu) |

| MLR | 0,43 ± 0,27 [0,4 - 0,46] | 0,45 ± 0,53 [0,39 - 0,5] | 0.279 (mwu) |

| SII | 985,99 ± 936,22 [883,35 - 1088,64] | 962,46 ± 1118,44 [839,83 - 1085,08] | 0.682 (mwu) |

| SIRI | 2,8 ± 2,92 [2,48 - 3,12] | 2,94 ± 3,67 [2,54 - 3,35] | 0.644 (mwu) |

| Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) | 46,84 ± 16,49 [45,04 - 48,65] | 48,19 ± 9,37 [47,16 - 49,22] | <0.001 (mwu) |

| Renal Indices | |||

| BUN Creatinine Ratio | 33,74 ± 71,53 [25,89 - 41,58] | 29,68 ± 54,69 [23,68 - 35,67] | 0.359 (mwu) |

| UHR (Uric Acid-to-HDL Ratio) | 0,17 ± 0,12 [0,16 - 0,18] | 0,18 ± 0,1 [0,17 - 0,19] | 0.031 (mwu) |

| UA/Creatinine Ratio | 6,5 ± 7,65 [5,66 - 7,34] | 6,48 ± 6,05 [5,81 - 7,14] | 0.055 (mwu) |

| Abbreviations: USG: Ultrasonography; MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease; BMI: Body mass index; WHtR: Waist-to-height ratio; ABSI: A Body Shape Index; PI: Ponderal Index; CI: Conicity Index; RFM: Relative Fat Mass; TyG: Triglyceride–glucose index; TyG/HDL: Triglyceride–glucose to HDL cholesterol ratio; AIP: Atherogenic Index of Plasma; LAP: Lipid Accumulation Product; VAI: Visceral Adiposity Index; TyG-BMI: Triglyceride–glucose index adjusted for BMI; TyG-WC: Triglyceride–glucose index adjusted for waist circumference; TyG-WHtR: Triglyceride–glucose index adjusted for waist-to-height ratio; Castelli I: Total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio; Castelli II: LDL cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio; Non-HDL-C: Non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; RC: Remnant cholesterol; PP: Pulse pressure; RPP: Rate pressure product; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; APRI: AST-to-platelet ratio index; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4 index; HSI: Hepatic Steatosis Index; NFS: NAFLD Fibrosis Score; ALBI: Albumin–bilirubin score; HALP: Hemoglobin–albumin–lymphocyte–platelet score; NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; MLR: Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio; SII: Systemic immune–inflammation index; SIRI: Systemic inflammation response index; PNI: Prognostic Nutritional Index; BUN/Cr: Blood urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio; UHR: Uric acid-to-HDL cholesterol ratio; UA/Cr: Uric acid-to-creatinine ratio | |||

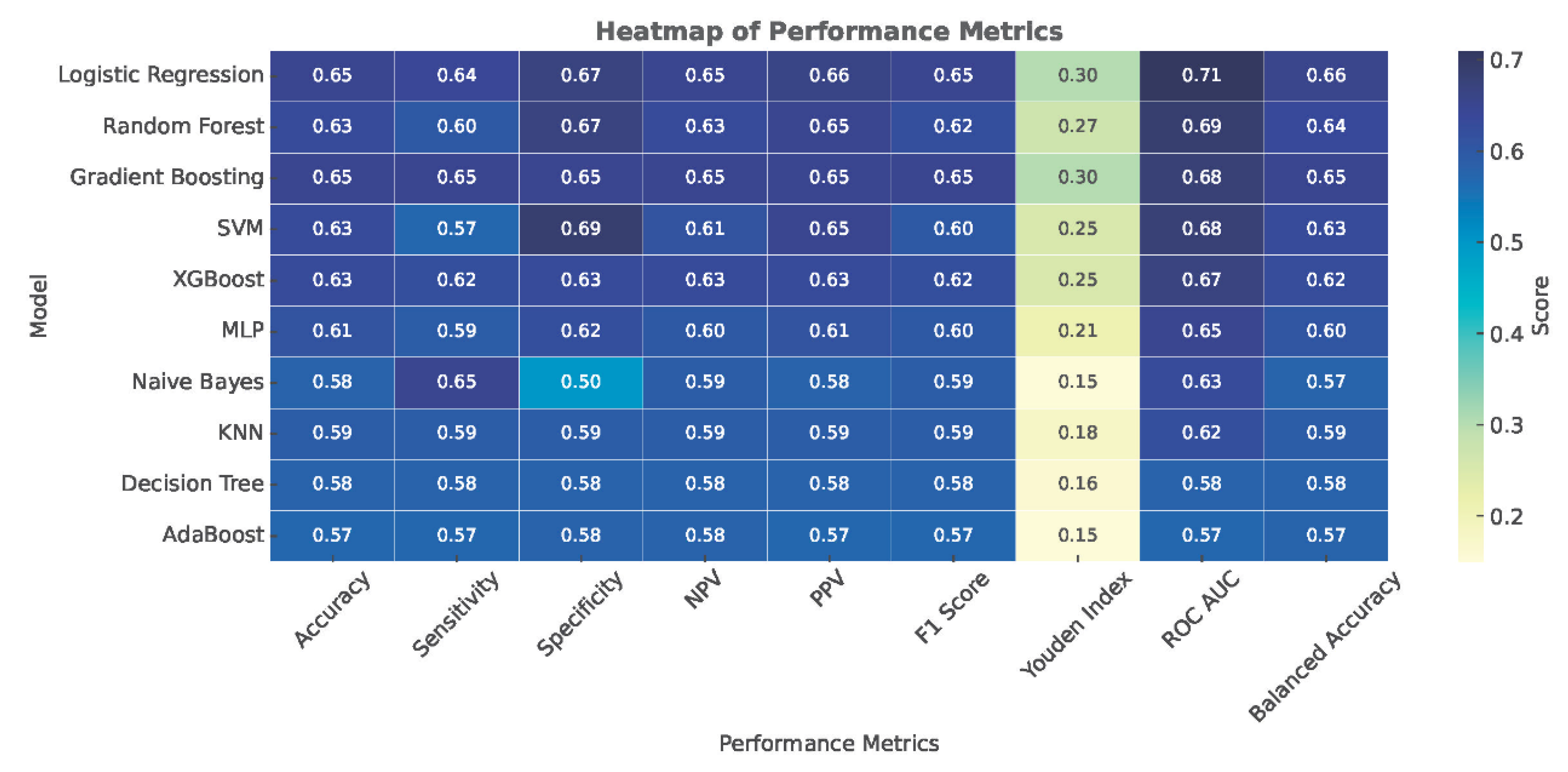

| Model | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | NPV | PPV | F1 Score | Youden Index | ROC AUC | Balanced Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 0.67 ± 0.06 | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.65 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 0.66 ± 0.06 |

| Random Forest | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 0.67 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.04 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 0.69 ± 0.04 | 0.64 ± 0.04 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.06 | 0.65 ± 0.06 | 0.65 ± 0.04 | 0.65 ± 0.04 | 0.65 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 0.65 ± 0.06 |

| SVM | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.69 ± 0.06 | 0.61 ± 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.05 | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 0.63 ± 0.05 |

| XGBoost | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 0.67 ± 0.03 | 0.62 ± 0.06 |

| MLP | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.07 | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.04 |

| Naive Bayes | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.65 ± 0.20 | 0.50 ± 0.22 | 0.59 ± 0.09 | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.11 | 0.15 ± 0.12 | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 0.57 ± 0.21 |

| KNN | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 0.59 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.06 |

| Decision Tree | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.16 ± 0.08 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.06 |

| AdaBoost | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.57 ± 0.07 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.57 ± 0.05 | 0.15 ± 0.08 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.57 ± 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).