1. Introduction

Mechanical metamaterials are architected solids whose effective properties are governed primarily by geometry rather than base material composition. These engineered structures enable functionalities such as lightweight energy absorption, programmable deformation, multistability, and shape morphing, with applications in aerospace structures, biomedical devices, soft robotics, and protective systems [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Recent work has shown that controlled buckling, snap-through, and phase-transition-like transformations can be used to realize tunable force–displacement or stress–strain responses on demand, rather than relying on the intrinsic response of a homogeneous material [

8,

9]. As a result, the design of metamaterials is increasingly viewed not only as structural layout design, but as direct control over nonlinear mechanical behavior for specific functions [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Although many classes of high-performance metamaterials have been demonstrated, their design remains challenging. Conventional “forward” workflows typically begin with a candidate topology inspired by natural templates such as cellular, porous, or origami-like patterns, and then iterate through simulation and manual refinement [

8,

14,

15]. This approach has produced notable successes, including ultralight lattices and multistable snapping systems, but it is time-consuming, problem-specific, and scales poorly when the goal is to match a prescribed mechanical response under large deformation [

5,

7]. In modern applications, designers increasingly require materials whose global response is staged or switchable — for example, an initially compliant regime for impact mitigation, followed by a stiffening or locking regime for load-bearing [

4,

6,

9]. Achieving such behavior by manual tuning is difficult because performance, manufacturability, and stability must be balanced simultaneously [

10,

12,

16].

Inverse design aims to address this challenge by reversing the traditional workflow: instead of starting from geometry and predicting behavior, it starts from the desired mechanical response and searches for a compatible microstructure [

17,

18,

19]. This paradigm is particularly attractive for metamaterials, where the mapping from geometry to response is often nonlinear, history-dependent, and governed by local instabilities such as buckling and self-contact [

20]. With recent advances in machine learning, inverse design is increasingly seen as a path toward performance-by-design structures in both structural and functional materials [

10,

11,

12,

13,

21].

Current machine-learning-based inverse design strategies can be broadly grouped into two categories. The first category is

parametric or low-dimensional design. In these approaches, the metamaterial is represented using a finite set of geometric parameters, and surrogate models or neural networks are trained to map those parameters to mechanical performance [

22,

23,

24,

25]. These models can then be coupled with heuristic or evolutionary optimizers to efficiently explore the parameter space and produce customized load–displacement curves for specific structure families [

22,

26]. Although computationally efficient and interpretable, such methods are constrained by the assumed parameterization. They typically operate within a predefined family of unit cells (e.g., shells, graded lattices, or spinodoid structures), and may struggle to capture drastic topological changes or complex post-buckling behavior [

24,

25,

26].

The second category is

non-parametric generative design, in which the microstructure is treated directly as an image-, voxel-, or implicit-surface field rather than a hand-crafted geometric template [

27,

28,

29,

30]. This class of methods leverages deep generative models to learn high-dimensional structure–property relationships from data. Convolutional neural networks and generative adversarial networks (GANs) have been used to synthesize topologies with target stiffness or target bulk modulus, and to encode the geometry of cellular materials in an implicit representation [

27,

28,

31,

32]. Variational autoencoders (VAEs) take a related approach by embedding complex microstructures into a smooth latent space, which can then be searched or optimized for target properties [

26,

33,

34].

More recently, diffusion models have emerged as a powerful alternative for generative inverse design. These models iteratively transform random noise into structured outputs by learning a reverse denoising process [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Unlike GANs, diffusion models are known for their sampling stability and controllability. They have been applied to reconstruct complex microstructures, generate energy-absorbing metamaterials tailored to specified loading curves, and model time-dependent deformation fields in nonlinear metamaterials under load [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. These advances suggest that generative modeling can move beyond “shape suggestion” and toward direct synthesis of structures with prescribed mechanical behavior.

However, important challenges remain for the inverse design of

hyperelastic metamaterials that undergo large strain, geometric nonlinearity, and path-dependent softening. Under compression, such microstructures often exhibit multiple sequential regimes: an initially compliant phase dominated by bending, followed by buckling and stress softening, and eventually densification accompanied by contact and rapid stiffening [

9,

20,

45,

46]. Capturing these regimes is essential for applications such as impact mitigation and reusable energy absorption. At the same time, it is difficult for standard optimization-based approaches because the mapping from topology to force–displacement behavior is strongly nonconvex and not easily parameterized [

22,

24,

26]. While recent diffusion-based studies have demonstrated controllable generation for elastoplastic or energy-absorbing systems [

39,

40,

44], there is still limited work on learning a direct mapping from a target nonlinear force–displacement curve to a manufacturable hyperelastic porous topology that remains physically realistic under large deformation, including buckling and post-buckling contact.

A key difficulty in this field lies in the intrinsic ill-posedness of the inverse mapping between geometry and mechanical response. For hyperelastic porous microstructures, the mapping from a target force–displacement curve to geometry is inherently ill-posed for four coupled reasons: (i) non-uniqueness—distinct topologies can realize nearly identical curves, while similar patterns may diverge; (ii) nonconvexity and mode switching introduced by buckling, contact, and densification; (iii) high sensitivity of the response to small geometric perturbations (e.g., manufacturing tolerances); and (iv) the limited descriptive power of low-dimensional features such as volume fraction. These challenges motivate the adoption of a probabilistic, condition-guided generative formulation that can naturally represent one-to-many mappings instead of enforcing a single deterministic inverse. Representative examples illustrating these phenomena are provided in

Section 3.

To address this gap, we propose

HyperDiff, a conditional diffusion-based inverse design framework for hyperelastic porous microstructures with nonlinear mechanical responses, as outlined in

Figure 1. The core idea is to treat the desired global response — here expressed as a force–displacement curve — as a conditioning signal for a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) [

35,

36]. The diffusion model is implemented using a U-Net backbone with residual connections and attention-based conditioning [

28,

37,

39,

47,

48], which enables it to generate candidate microstructure topologies directly in image form. To supply meaningful training data, we construct an integrated pipeline that (i) procedurally generates porous microstructures, (ii) calibrates a hyperelastic constitutive model for the base material using tensile experiments, (iii) simulates large-deformation compression via finite element analysis to obtain full force–displacement curves, and (iv) encodes those curves in a compact form suitable for conditional generation [

10,

16,

45,

46,

49]. The resulting framework links data generation, inverse design, forward simulation, and experimental validation.

In summary, this work demonstrates that conditional diffusion modeling can be used to generate diverse and physically consistent microstructures that reproduce prescribed nonlinear force–displacement behavior, including regimes dominated by bending, buckling, softening, and densification. By focusing on hyperelastic, large-strain responses — a setting where topology, instability, and contact play central roles — this study aims to contribute to the practical integration of generative AI tools into the design workflow of nonlinear architected materials [

9,

12,

13,

21,

44].

The remainder of this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the theoretical basis of denoising diffusion probabilistic models and details the proposed

HyperDiff framework.

Section 3 describes the dataset generation pipeline, including GRF-based topology synthesis, material characterization, and finite element (FE) simulation of force–displacement responses.

Section 4 explains the model training strategy, including conditioning, data normalization, and key hyperparameters.

Section 5 reports numerical results on both test and interpolated targets to assess performance and generalization.

Section 6 presents experimental verification via quasi-static compression tests and compares measurements with simulations. Finally,

Section 8 summarizes the main findings, discusses limitations, and outlines future directions.

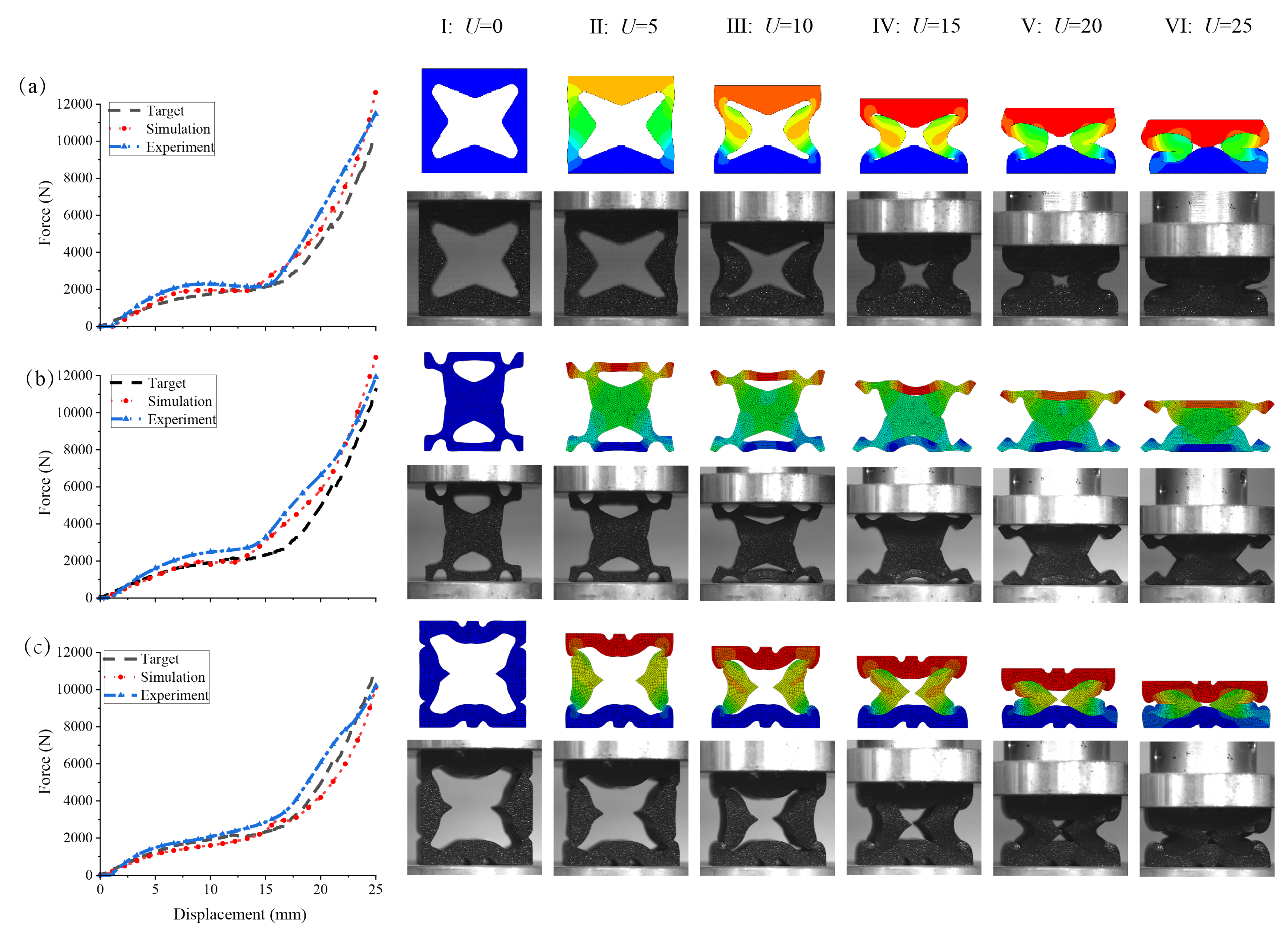

6. Experimental Verification

To validate the predictive accuracy and physical consistency of the proposed

HyperDiff framework, a series of quasi-static compression experiments were performed on representative energy-absorbing metamaterial specimens. The samples were fabricated via

3D printing (additive manufacturing) and tested using a universal testing machine under a constant compression rate of 2 mm/min, ensuring quasi-static loading conditions. During the tests, force and displacement data were synchronously recorded to accurately capture the mechanical responses. The experimental setup enabled continuous observation of deformation patterns and ensured repeatability of the results. A comprehensive comparison between experimental and simulation results is presented in

Figure 8.

As shown in

Figure 8, the left column presents the force–displacement curves obtained from the target, numerical simulation, and experimental measurements (black dashed, red dotted, and blue dash–dot lines, respectively). The normalized root-mean-square error (NRMSE) was used to evaluate prediction accuracy. For the representative case shown, the NRMSE between the experimental and target curves was 9.41%, between the simulated and target curves 6.10%, and between the experimental and simulated curves 4.42%. These results confirm that the

HyperDiff model can accurately reproduce the nonlinear mechanical behavior of the designed metamaterials.

The right-hand side of

Figure 8 illustrates the deformation sequences (stages I–VI) under progressive compression. The top row shows the simulated von Mises stress contours, while the bottom row presents the corresponding experimental deformation images. As strain increased, small internal pores closed first (stages II–III). When the displacement reached approximately 15 mm (stage IV), the central pore was nearly closed. Further loading caused contact between the upper and lower beams and the compression plate, leading to a rapid increase in tangent stiffness. The regions of high stress in the simulations correspond closely to the zones of visible large-strain localization and contact-induced densification in the experiments, indicating that the model captures the essential physical mechanisms rather than merely fitting data correlations. This agreement reinforces the interpretability and physical reliability of the proposed framework.

A detailed analysis of the first case in

Figure 8 is presented as a representative example. The other tested specimens exhibited consistent deformation modes and response trends, demonstrating the robustness of both the model and experimental validation process.

7. Discussion

The results in

Section 5 and

Section 6 show that

HyperDiff can recover the main features of nonlinear force–displacement responses for hyperelastic porous microstructures across both numerical simulations and experiments. This section provides a mechanics-aware interpretation of these results, explains how the conditional diffusion process organizes structure–response relations, and outlines the scope and limitations of the present framework.

7.1. From a Difficult Inverse Problem to a Tractable Generative View

Inverse design in the large-deformation hyperelastic regime is challenging because the macroscopic response arises from multiple sequential mechanisms—early-stage bending compliance, instability-induced softening, contact-mediated load transfer, and late-stage densification. These mechanisms lead to a highly nonconvex, inherently one-to-many mapping between topology and response. Small geometric perturbations can trigger a completely different instability path, while distinct microstructures may yield similar global responses. Under such conditions, parametric regression or gradient-based optimization often becomes trapped in local minima and lacks generality across design families.

The present framework addresses this difficulty by shifting from “solve-for-the-one” to “sample-from-the-set.” Instead of pursuing a deterministic inverse map, HyperDiff learns the conditional distribution of admissible topologies given a target response. This generative perspective is consistent with the physical nature of the problem: for a prescribed force–displacement curve, multiple feasible microstructures usually exist. Sampling diverse candidates and retaining those verified by forward analysis thus provides a pragmatic and robust solution.

7.2. A Mechanics-Aware Reading of the Diffusion Process

Although diffusion models are typically introduced as statistical denoisers, the present results suggest a mechanics-aware interpretation in this context. The U-Net backbone with residual connections captures local void morphologies, while spatial transformers ensure global coherence consistent with compression load paths. During denoising, structural features emerge in a physically ordered sequence: early iterations determine initial compliance (void slenderness and ligament curvature), mid-stage updates control buckling onset and amplitude, and later iterations form load-bearing bridges that sustain densification.

Hence, the iterative sampling process does not merely “reconstruct an image,” but instead relaxes toward configurations that are both statistically plausible and mechanically admissible under the given conditioning signal. This explains why the generated microstructures reproduce not only the overall force–displacement trends but also the observed deformation stages in both simulation and experiment.

7.3. Conditioning Via Force–Displacement Curves as Energy-Trend Guidance

A distinctive element of HyperDiff lies in its conditioning strategy based on a compact B-spline representation of the target force–displacement curve. Although no explicit energy integration is enforced, the curve inherently reflects the cumulative exchange of mechanical work during loading; the corresponding B-spline coefficients thus serve as a concise descriptor of the system’s energy-evolution trend. Conditioning on this vector provides temporal (stage-wise) and mechanical (stiffness/softening/densification) context to the generator. Empirically, this guidance enables the model to converge toward structures that exhibit the correct sequence of deformation mechanisms, not merely the right scalar magnitudes.

This interpretation also clarifies the difference from encodings that treat the curve as a generic signal: here, the conditioning is designed to carry physically meaningful information. Extending the conditioning vector with explicit cumulative-energy or stage-indicator terms is straightforward if finer phase control is desired in future studies.

7.4. Applicability, Robustness, and Boundaries

The current implementation focuses on two-dimensional unit cells at a fixed image resolution and on quasi-static compression of a calibrated hyperelastic material. Within this scope, the method is robust: it achieves low deviations on held-out targets, maintains accuracy on interpolated curves, and yields printed samples whose deformation patterns match simulations. These results support that the learned topology–response relationships are physically meaningful rather than numerical coincidences.

At the same time, clear boundaries exist. Out-of-plane effects are excluded by design; rate dependence, viscoelasticity, and thermal coupling are not considered; and the minimum printable feature size is constrained by the image resolution. Diffusion-based sampling is computationally more demanding than direct regression, but the gain in solution diversity is valuable in nonconvex design spaces. These factors should be kept in mind when generalizing beyond the current dataset.

7.5. Relation to Prior Inverse Design Studies

Compared with inverse design frameworks developed for elastoplastic or energy-absorbing systems, the present study targets the finite-strain hyperelastic regime, where geometric and constitutive nonlinearities interact. Methodologically, the main differences are: (i) a generative, distributional formulation of the inverse problem; (ii) a physically meaningful conditioning vector encoding the energy-evolution trend; and (iii) validation of both global responses and stage-wise deformation modes through numerical and experimental means. These aspects explain the consistent performance observed for highly nonlinear targets that typically challenge deterministic regressors.

7.6. Practical Implications

In practice, HyperDiff can be used in two complementary modes. First, as a design exploration tool, it rapidly proposes multiple distinct microstructures for a single target, allowing post-selection under additional criteria such as manufacturability or stress localization. Second, as a front-end generator, it provides physically consistent initial designs for subsequent physics-based optimization. Both usages exploit the model’s diversity while maintaining mechanical consistency.

Summary. When conditioned on an energy-trend encoding of the desired response, the diffusion model acts as a probabilistic sampler over physically feasible topologies in a nonconvex design space. This perspective reconciles data-driven generation with mechanics-based understanding and explains the cross-consistency observed between simulations and experiments.

Figure 1.

Overall technical roadmap of the proposed HyperDiff framework for the inverse design of hyperelastic porous microstructures. The workflow integrates data generation, conditional diffusion modeling, and multi-physics validation. (a) Diverse microstructure topologies are generated using Gaussian random fields (GRF) and analyzed via finite element simulations under quasi-static compression to obtain nonlinear force–displacement curves, forming a large structure–response dataset. (b) The desired target mechanical curve is encoded as a compact conditional vector that guides the diffusion model during denoising. (c) Starting from random noise, the model progressively reconstructs candidate microstructures consistent with the specified mechanical behavior. (d) The framework yields multiple physically admissible and topologically diverse solutions that reproduce the target nonlinear response, enabling one-to-many, data-driven inverse design of hyperelastic metamaterials.

Figure 1.

Overall technical roadmap of the proposed HyperDiff framework for the inverse design of hyperelastic porous microstructures. The workflow integrates data generation, conditional diffusion modeling, and multi-physics validation. (a) Diverse microstructure topologies are generated using Gaussian random fields (GRF) and analyzed via finite element simulations under quasi-static compression to obtain nonlinear force–displacement curves, forming a large structure–response dataset. (b) The desired target mechanical curve is encoded as a compact conditional vector that guides the diffusion model during denoising. (c) Starting from random noise, the model progressively reconstructs candidate microstructures consistent with the specified mechanical behavior. (d) The framework yields multiple physically admissible and topologically diverse solutions that reproduce the target nonlinear response, enabling one-to-many, data-driven inverse design of hyperelastic metamaterials.

Figure 2.

Network overview and core modules of HyperDiff. (a) Denoising diffusion with a U-Net backbone. Starting from pure Gaussian noise , the model iteratively predicts and reconstructs a clear microstructure . The lower row shows the multi-scale U-Net with encoder–decoder symmetry and skip connections (red). Channel sizes and spatial resolutions are indicated as . Green blocks denote residual blocks; orange blocks denote spatial transformers; blue markers indicate max pooling / up sampling; convolutions perform channel projection. (b) Residual block (green region). Each block uses GroupNorm and SiLU activations with two convolutions, and injects the diffusion time-step via FiLM-style feature-wise modulation (time embedding → scale/shift). A residual shortcut preserves stable gradients and enables dynamic, time-aware local denoising. (c) Spatial transformer (orange region). Features are normalized, reshaped, and linearly projected, followed by self-attention and multi-head attention. The target force–displacement curve is encoded as a condition vector and fused as keys/values, enabling cross-attention guidance that propagates global mechanical constraints over the spatial field. A feed-forward network and output projection ( conv) complete the block, with residual connections for stability.

Figure 2.

Network overview and core modules of HyperDiff. (a) Denoising diffusion with a U-Net backbone. Starting from pure Gaussian noise , the model iteratively predicts and reconstructs a clear microstructure . The lower row shows the multi-scale U-Net with encoder–decoder symmetry and skip connections (red). Channel sizes and spatial resolutions are indicated as . Green blocks denote residual blocks; orange blocks denote spatial transformers; blue markers indicate max pooling / up sampling; convolutions perform channel projection. (b) Residual block (green region). Each block uses GroupNorm and SiLU activations with two convolutions, and injects the diffusion time-step via FiLM-style feature-wise modulation (time embedding → scale/shift). A residual shortcut preserves stable gradients and enables dynamic, time-aware local denoising. (c) Spatial transformer (orange region). Features are normalized, reshaped, and linearly projected, followed by self-attention and multi-head attention. The target force–displacement curve is encoded as a condition vector and fused as keys/values, enabling cross-attention guidance that propagates global mechanical constraints over the spatial field. A feed-forward network and output projection ( conv) complete the block, with residual connections for stability.

Figure 3.

Dataset construction and physical simulation framework for HyperDiff. (a) Microstructure generation based on a 2D Gaussian random field (GRF). A continuous GRF is thresholded to produce binary topologies, followed by connectivity filtering, symmetry reconstruction, and contour smoothing from rough to smooth edges. This process yields physically consistent and geometrically diverse unit cells. (b) Material calibration using uniaxial tensile tests. The TPU specimen geometry and testing setup are shown, together with the engineering, true, and fitted stress–strain curves. A second-order Ogden model accurately captures the nonlinear hyperelastic behavior. (c) Finite element simulations and force–displacement responses. Different generated microstructures are compressed under displacement control. The von Mises stress contours and corresponding force–displacement curves reveal characteristic deformation stages of elastic response, buckling, and densification. These results form a physically grounded dataset for training the conditional diffusion model.

Figure 3.

Dataset construction and physical simulation framework for HyperDiff. (a) Microstructure generation based on a 2D Gaussian random field (GRF). A continuous GRF is thresholded to produce binary topologies, followed by connectivity filtering, symmetry reconstruction, and contour smoothing from rough to smooth edges. This process yields physically consistent and geometrically diverse unit cells. (b) Material calibration using uniaxial tensile tests. The TPU specimen geometry and testing setup are shown, together with the engineering, true, and fitted stress–strain curves. A second-order Ogden model accurately captures the nonlinear hyperelastic behavior. (c) Finite element simulations and force–displacement responses. Different generated microstructures are compressed under displacement control. The von Mises stress contours and corresponding force–displacement curves reveal characteristic deformation stages of elastic response, buckling, and densification. These results form a physically grounded dataset for training the conditional diffusion model.

Figure 4.

Representative FE samples illustrating multi-stage deformation and response diversity (Cases 1–14). Each row shows a unique topology, its von Mises stress field under large deformation, and the corresponding force–displacement curve. The dataset spans bending-dominated compliance, buckling-induced softening (plateaus), and contact-driven densification, revealing a strongly nonconvex structure–response landscape.

Figure 4.

Representative FE samples illustrating multi-stage deformation and response diversity (Cases 1–14). Each row shows a unique topology, its von Mises stress field under large deformation, and the corresponding force–displacement curve. The dataset spans bending-dominated compliance, buckling-induced softening (plateaus), and contact-driven densification, revealing a strongly nonconvex structure–response landscape.

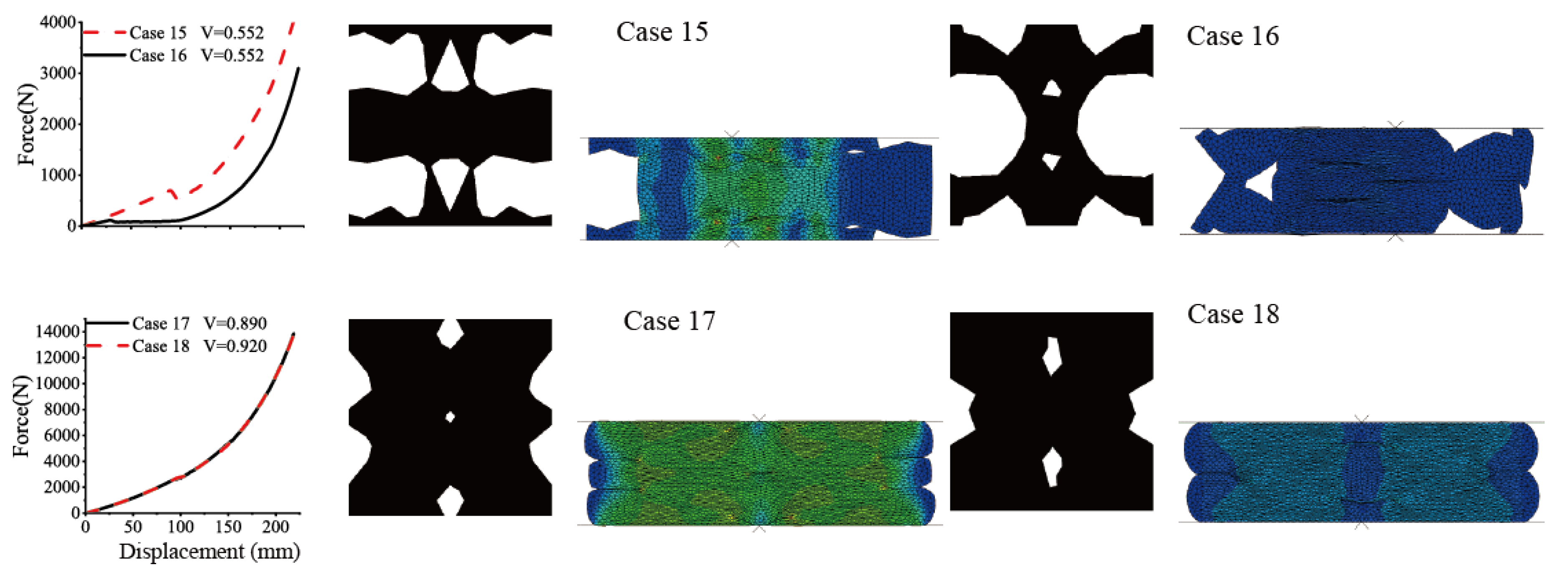

Figure 5.

Non-unique and weakly identifiable structure–property mappings (Cases 15–18).Top: distinct topologies with the same volume fraction yield markedly different force–displacement curves (mode switching under similar global descriptors). Bottom: topologies with different porosities produce nearly identical responses (one-to-many mapping). These comparisons highlight non-uniqueness, nonconvexity, and the limits of low-dimensional parametrizations, motivating a probabilistic inverse formulation.

Figure 5.

Non-unique and weakly identifiable structure–property mappings (Cases 15–18).Top: distinct topologies with the same volume fraction yield markedly different force–displacement curves (mode switching under similar global descriptors). Bottom: topologies with different porosities produce nearly identical responses (one-to-many mapping). These comparisons highlight non-uniqueness, nonconvexity, and the limits of low-dimensional parametrizations, motivating a probabilistic inverse formulation.

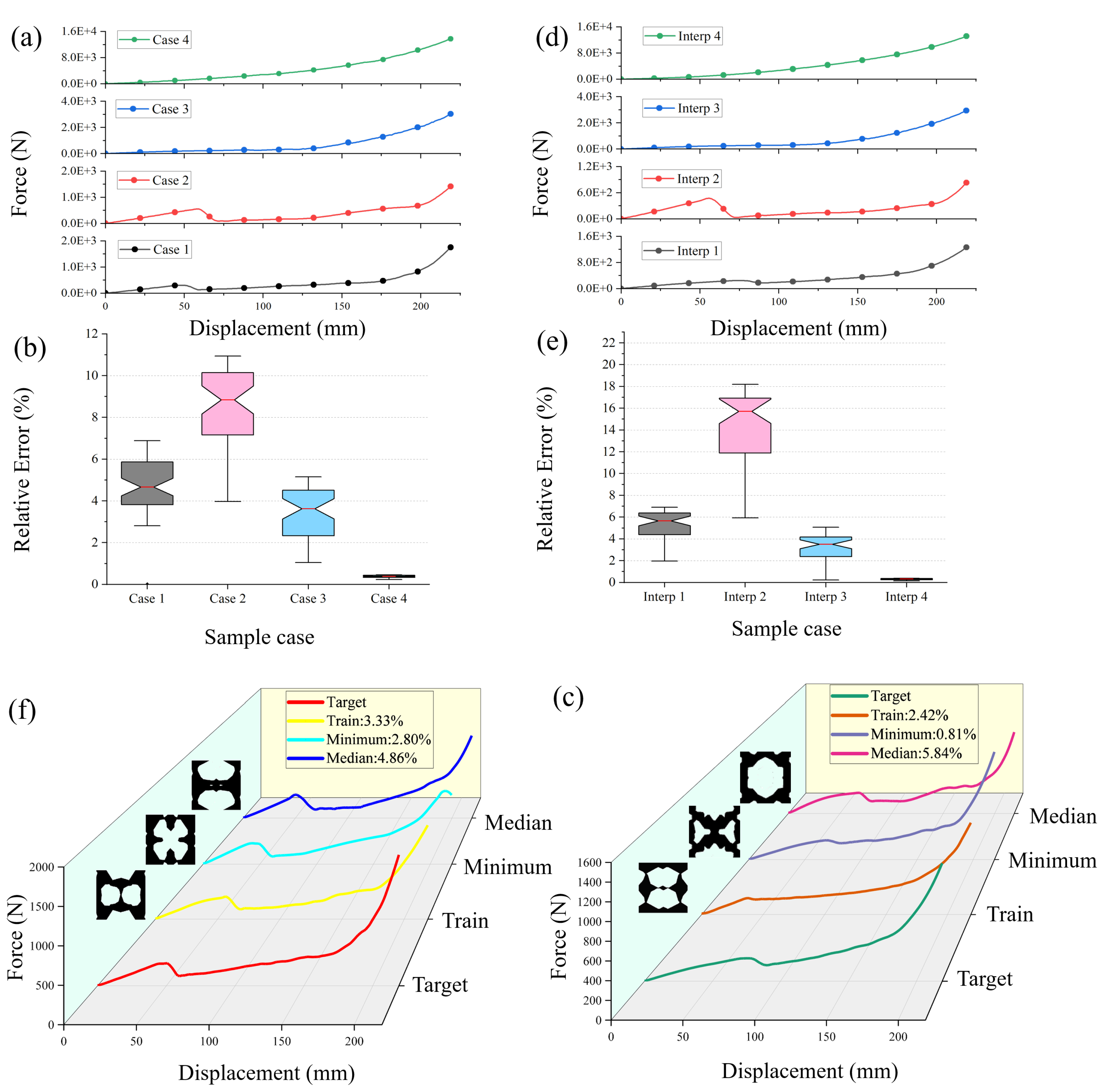

Figure 6.

Comprehensive evaluation of HyperDiff on test targets (left) and interpolated targets (right).Top row: per-case profiles of the normalized pointwise relative error along the displacement axis for four test cases (left) and four interpolated cases (right). Middle row: per-case NRMSE% distributions over 50 stochastic generations (center line = median; box = interquartile range; whiskers = 10–90th percentile). Bottom row: representative force–displacement overlays for Case 1 (left) and Interp. 1 (right); the target curve is compared to its nearest neighbor in the training set (NN-train) and the generated minimum/median samples. Legends report the corresponding percentage errors. Small topology thumbnails highlight one-to-many design diversity. Additional cases are detailed in fig:detailedresults.

Figure 6.

Comprehensive evaluation of HyperDiff on test targets (left) and interpolated targets (right).Top row: per-case profiles of the normalized pointwise relative error along the displacement axis for four test cases (left) and four interpolated cases (right). Middle row: per-case NRMSE% distributions over 50 stochastic generations (center line = median; box = interquartile range; whiskers = 10–90th percentile). Bottom row: representative force–displacement overlays for Case 1 (left) and Interp. 1 (right); the target curve is compared to its nearest neighbor in the training set (NN-train) and the generated minimum/median samples. Legends report the corresponding percentage errors. Small topology thumbnails highlight one-to-many design diversity. Additional cases are detailed in fig:detailedresults.

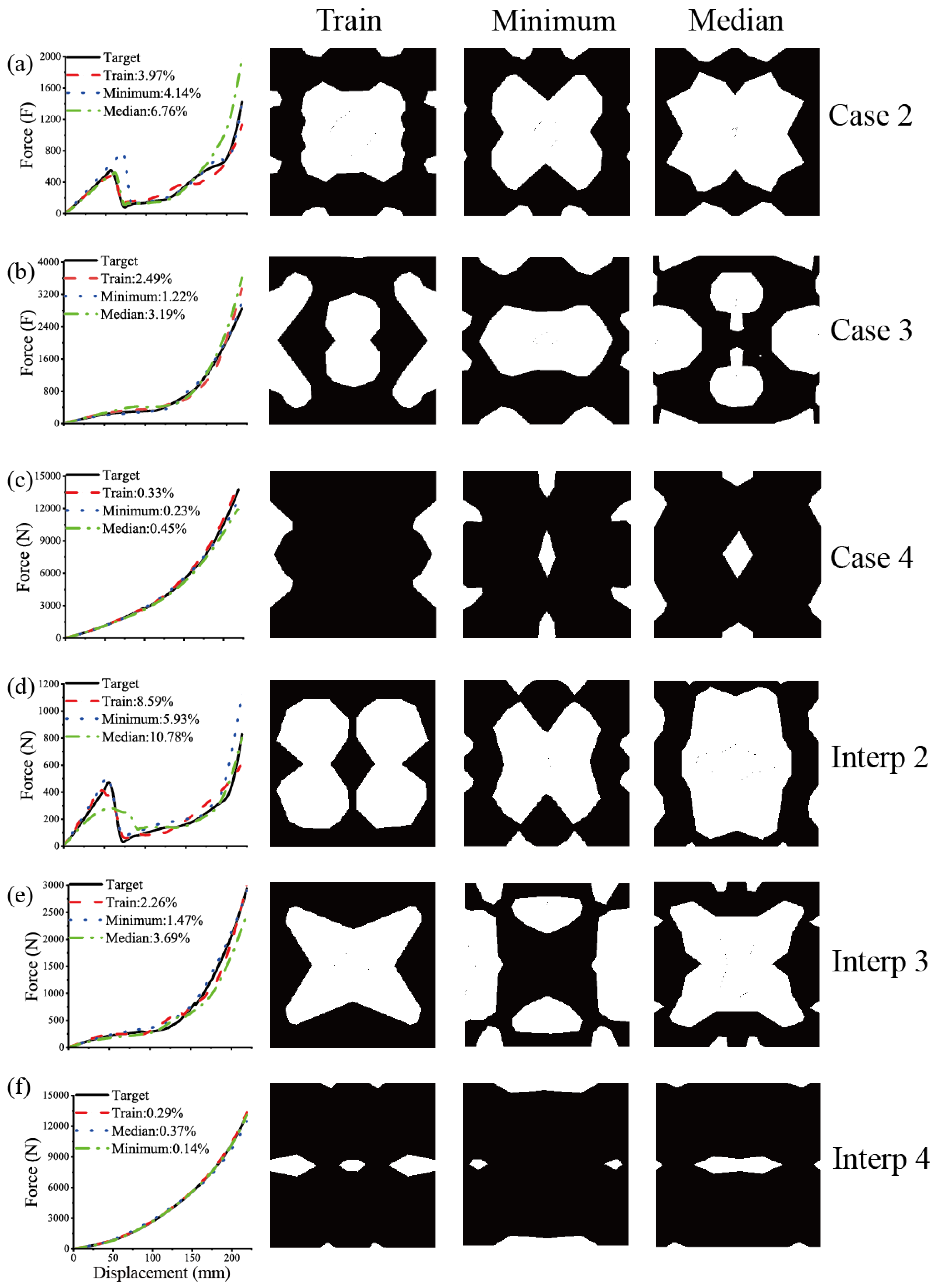

Figure 7.

Detailed overlays and corresponding topologies for the remaining test and interpolated targets. For each subfigure, the left panel shows the force–displacement overlay (Target, NN-train, Minimum, Median) with overall NRMSE%, and the three right panels show the corresponding topologies (Train, Minimum, Median).

Figure 7.

Detailed overlays and corresponding topologies for the remaining test and interpolated targets. For each subfigure, the left panel shows the force–displacement overlay (Target, NN-train, Minimum, Median) with overall NRMSE%, and the three right panels show the corresponding topologies (Train, Minimum, Median).

Figure 8.

Experimental verification of energy-absorbing metamaterials generated byHyperDiff. Comparison between simulation and experiment under quasi-static compression. The left panels show force–displacement curves (black dashed = target, red dotted = simulation, blue dash–dot = experiment). Vertical ticks on each curve mark six representative loading stages (I–VI) corresponding to global compression displacements and . The right panels display the corresponding deformation sequences, where the upper rows are simulated von Mises stress contours and the lower rows are experimental images. Regions of high simulated stress spatially coincide with the zones of visible large-strain localization and contact-induced densification observed in the experiments, indicating that the proposed model captures the essential deformation mechanisms and nonlinear responses of hyperelastic porous metamaterials. Here, U denotes the imposed displacement of the upper platen in millimeters (mm).

Figure 8.

Experimental verification of energy-absorbing metamaterials generated byHyperDiff. Comparison between simulation and experiment under quasi-static compression. The left panels show force–displacement curves (black dashed = target, red dotted = simulation, blue dash–dot = experiment). Vertical ticks on each curve mark six representative loading stages (I–VI) corresponding to global compression displacements and . The right panels display the corresponding deformation sequences, where the upper rows are simulated von Mises stress contours and the lower rows are experimental images. Regions of high simulated stress spatially coincide with the zones of visible large-strain localization and contact-induced densification observed in the experiments, indicating that the proposed model captures the essential deformation mechanisms and nonlinear responses of hyperelastic porous metamaterials. Here, U denotes the imposed displacement of the upper platen in millimeters (mm).

Table 1.

Fitted Ogden model parameters for the TPU material.

Table 1.

Fitted Ogden model parameters for the TPU material.

| Parameter |

Ogden model |

|

12.7464 |

|

0.0000 |

|

0.0000 |

|

0.0108 |

|

12.3711 |

|

0.0000 |

Table 2.

Key hyperparameters used for model training.

Table 2.

Key hyperparameters used for model training.

| Hyperparameter |

Value |

| Batch size |

64 |

| Learning rate |

|

| Decay steps |

25 |

| Decay factor |

0.99 |

| Input channels |

1 |

| Output channels |

1 |

| Base channels |

32 |

| Residual blocks |

1 |

| Attention layers enabled |

[False, True, False, True, False] |

| Channel multipliers |

[1, 1, 2, 2, 2] |

| Attention heads |

1 |

| Transformer layers |

1 |

| Condition embedding dimension |

[48] |

| Noise scale range () |

(1e-4, 0.02) |

| DDPM timesteps |

1000 |

| Loss function |

L2 loss (MSE) |

| Image resolution |

px |

| Training iterations |

100,000 |