Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

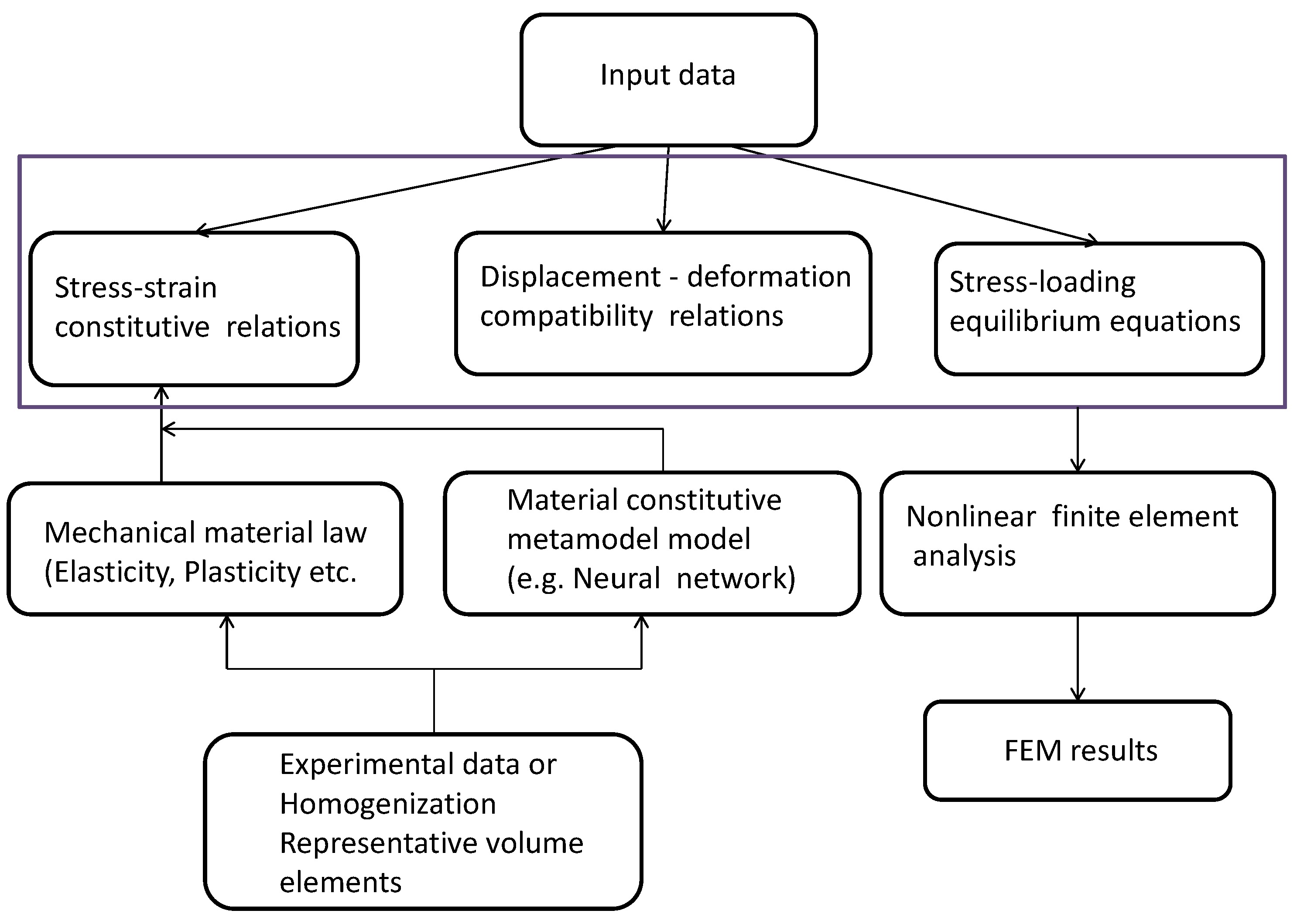

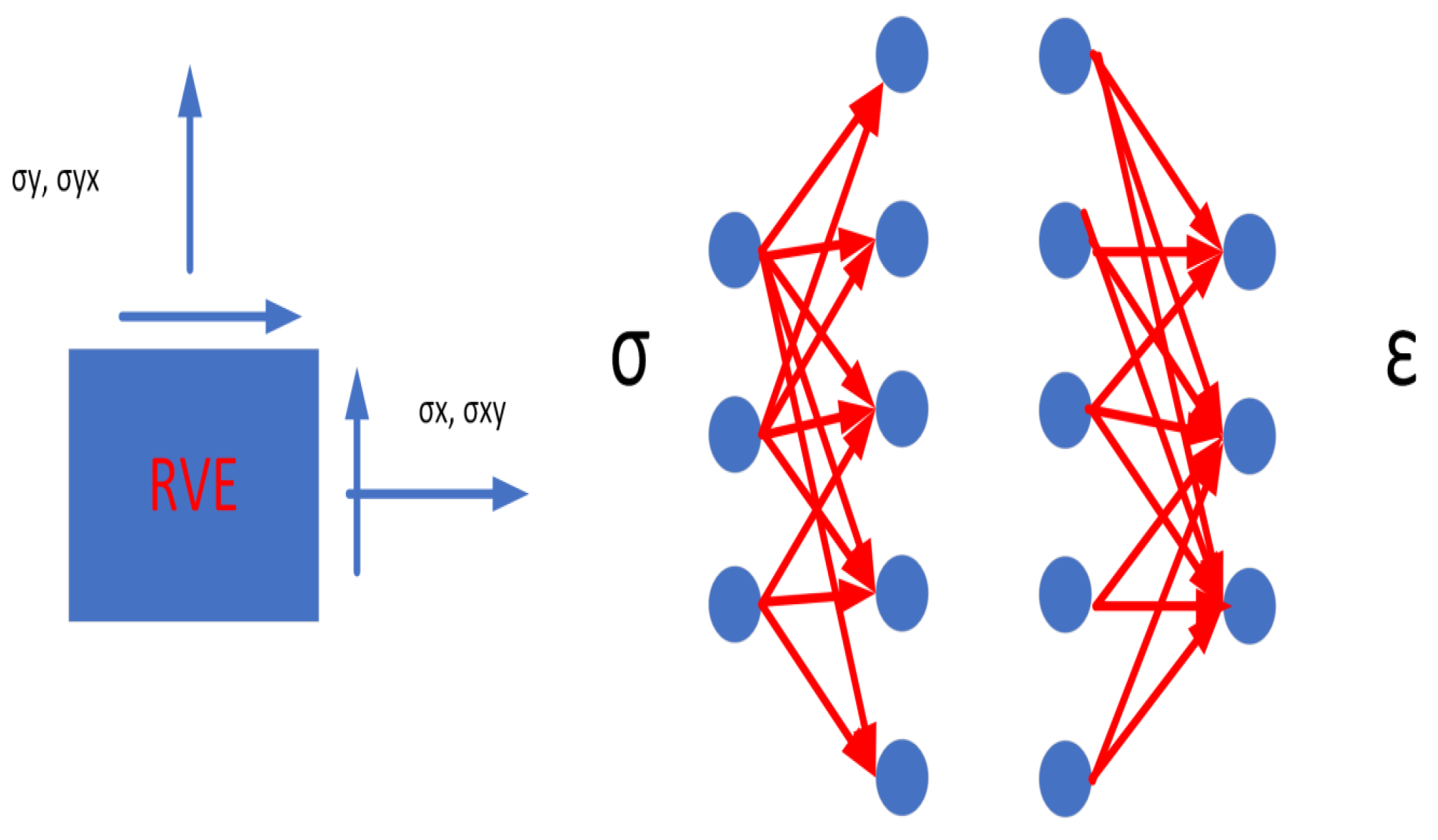

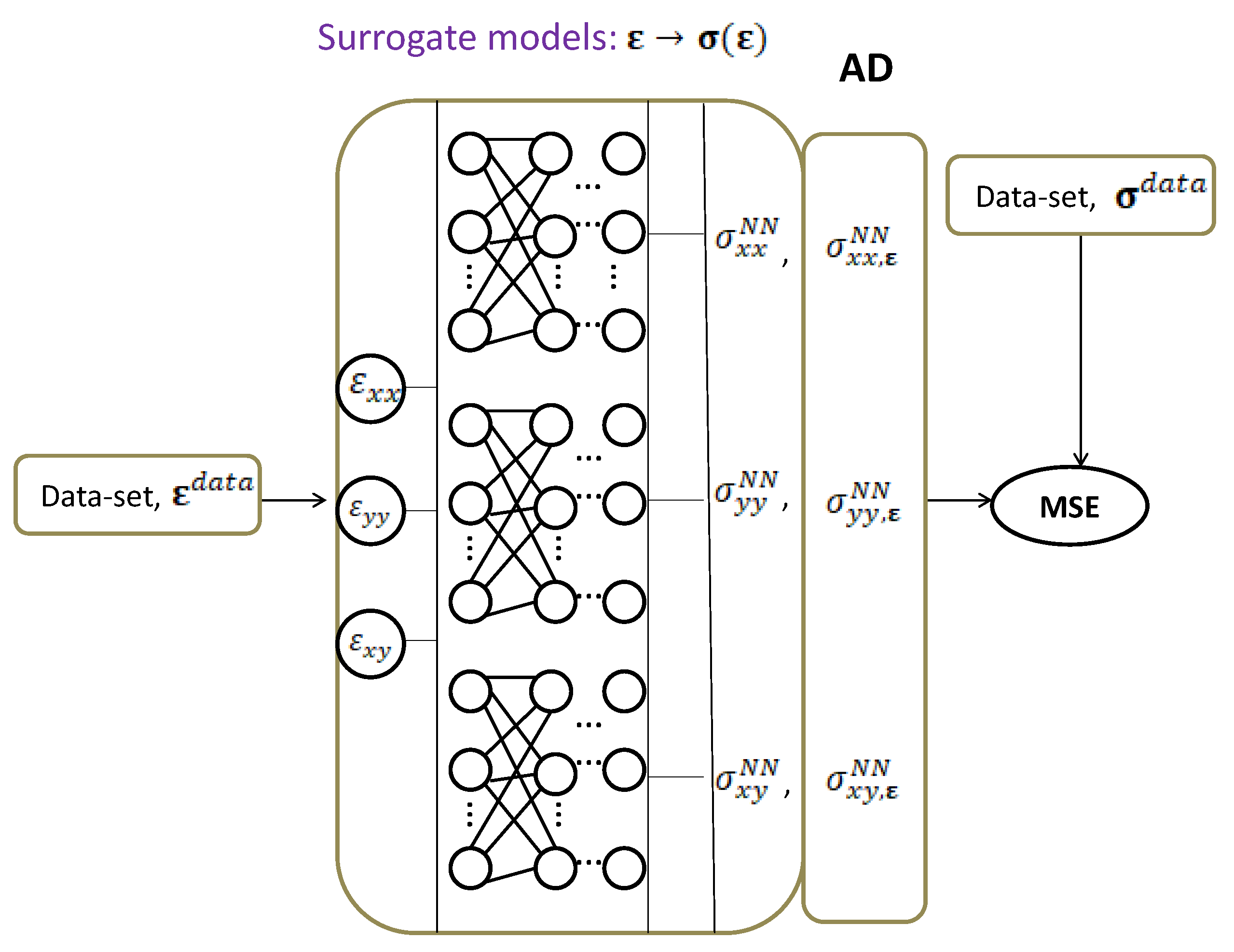

A neural network model for a constitutive law in nonlinear structures is proposed. The neural model is constructed based on a data set of responses of representative volume elements, calculated by finite elements. An open scientific software machine learning platform Tensorflow and an application programming interface, intended for a deep learning Keras library, provided by Python are used for the development of the artificial neural network. The tangential stiffness matrix within a multi-scale model is calculated via the method of automatic differentiation of Tensorflow. The results are compared with given data set. The loss function, including the Sobolev metrics is computed. The results can be integrated into a multiscale finite element analysis and provide results with less effort. The technique is also tested on hyperelastic materials.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Constitutive Metamodel, Based on Responses of Representative Volume Elements

3. Feedforward and Backpropagation in the Neural Model with a Computation of Tangential Stiffness Matrix

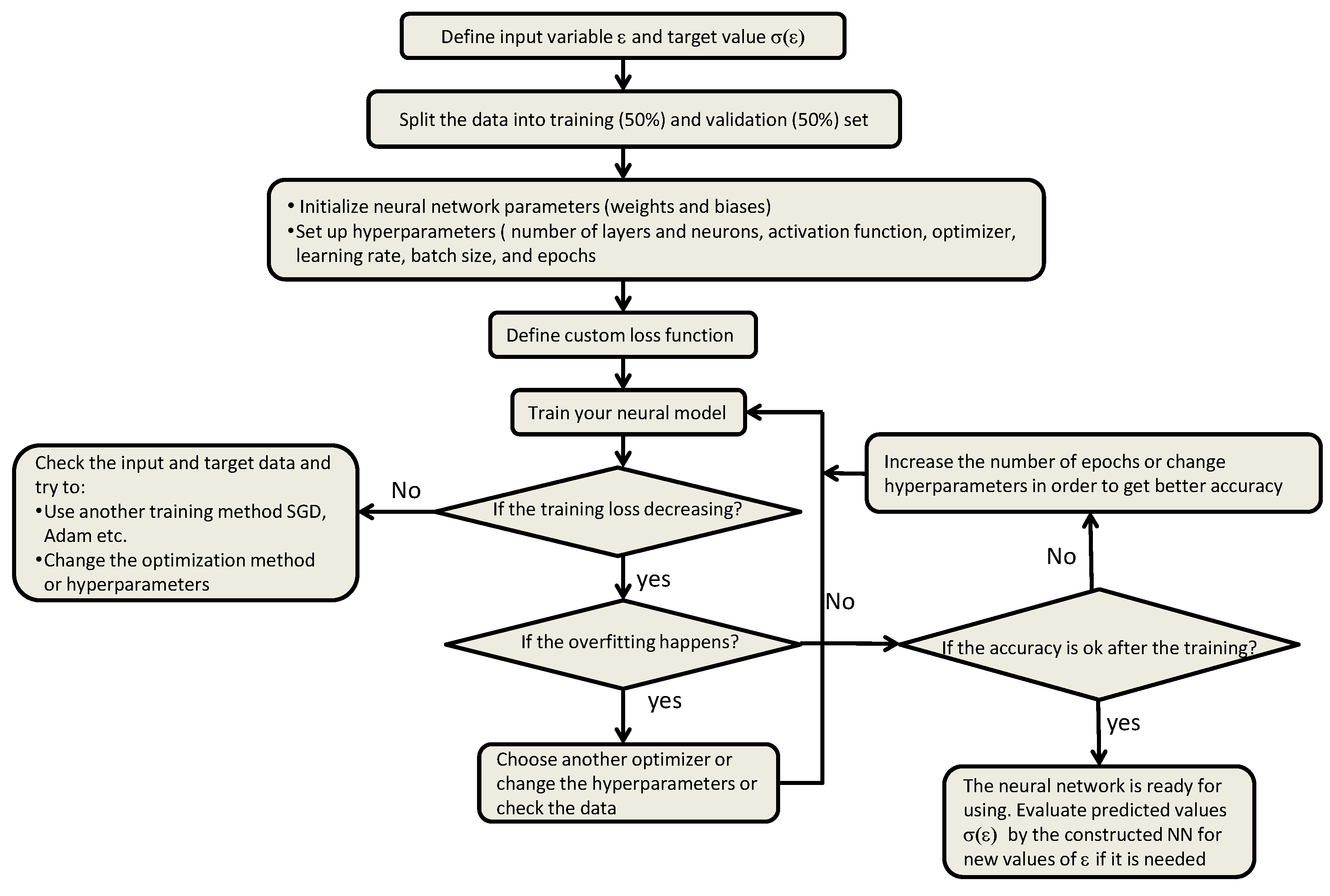

4. Computational Procedure

-

Import all necessary Python’s libraries: import tensorflow as tf, import keras, import matplotlib.pyplot as plt, import csv.(There are three distinct parts that define the TensorFlow: workflow, preprocessing of data, building the model, and training the model to make predictions.The Keras library is an open-source library of the TensorFlow platform that provides a Python interface for creation of artificial neural networks.Matplotlib is a library for creating static, animated, and interactive visualizations in Python. With Matplotlib.pyplot some plots are created in the code.The library csv allows writing and reading data in the CSV (Comma Separated Values), preferred by Excel.)

- Set up an input for neural surrogate networks from the data set of the strain tensor. There are three inputs, for each NN and each input is a vector of values.

- Set up output, training and test samples for the neural networks, data-set of the stress tensor for fitting while minimizing the error loss function.

- Set up a number of training iterations, epochs and batches for the neural networks.

- Read the data set, and if are avalable, from txt/csv files with np.genfromtxt function. A half of the data set are used for training and the other half for the test.

- Normalize the and data set if it is necessary withwhere is the new segment, and and use the chain rule for normalizing and computing derivatives, i.e.

- Create a class/function object in Python allowing Automatic Differentiation using Tensorflow tf.GradientTape module.

- Set up a number of neurons and layers for the NNs.

- Group layers (input, hidden and output), neurons into an object with training/inference features for the surrogate net metamodels with dimensions, with three inputs and one output, based on the Keras’ modules, tf.keras.Input, tf.keras.layers.Dense, tf. keras.models.Model, tf.keras.layers.Input.

- Call the class/function for Automatic Differentiation, defined in Step 7.

- Define the input and the output for the NNs using module tf. keras.models.Model for inputs and training items in the list of outputs.

- Create training and test data. The training variables for the inputs and for the output and In case of the Sobolev function are also included if the corresponding data are available.

- Choose an activation function. Here the tanh function is used.

- Compile the residual neural models using Keras’ module keras.models.Model.compile with the help of the built in Adam’s optimizer and Mean Square Error modules.

- Train the neural metamodels (the residual with the surrogate models) with using keras.models.Model.fit the training input and output data (backpropagation).

- Go back to the true values from the normalized output results and the derivatives.

- Plot graphs for the model accuracy, model loss and prediction results of the outputs of the NNs with the use of plot and history() functions, readily available for use inside Python and save the obtained data with, e.g. np.savetxt() and the figures with save plt.safefig().

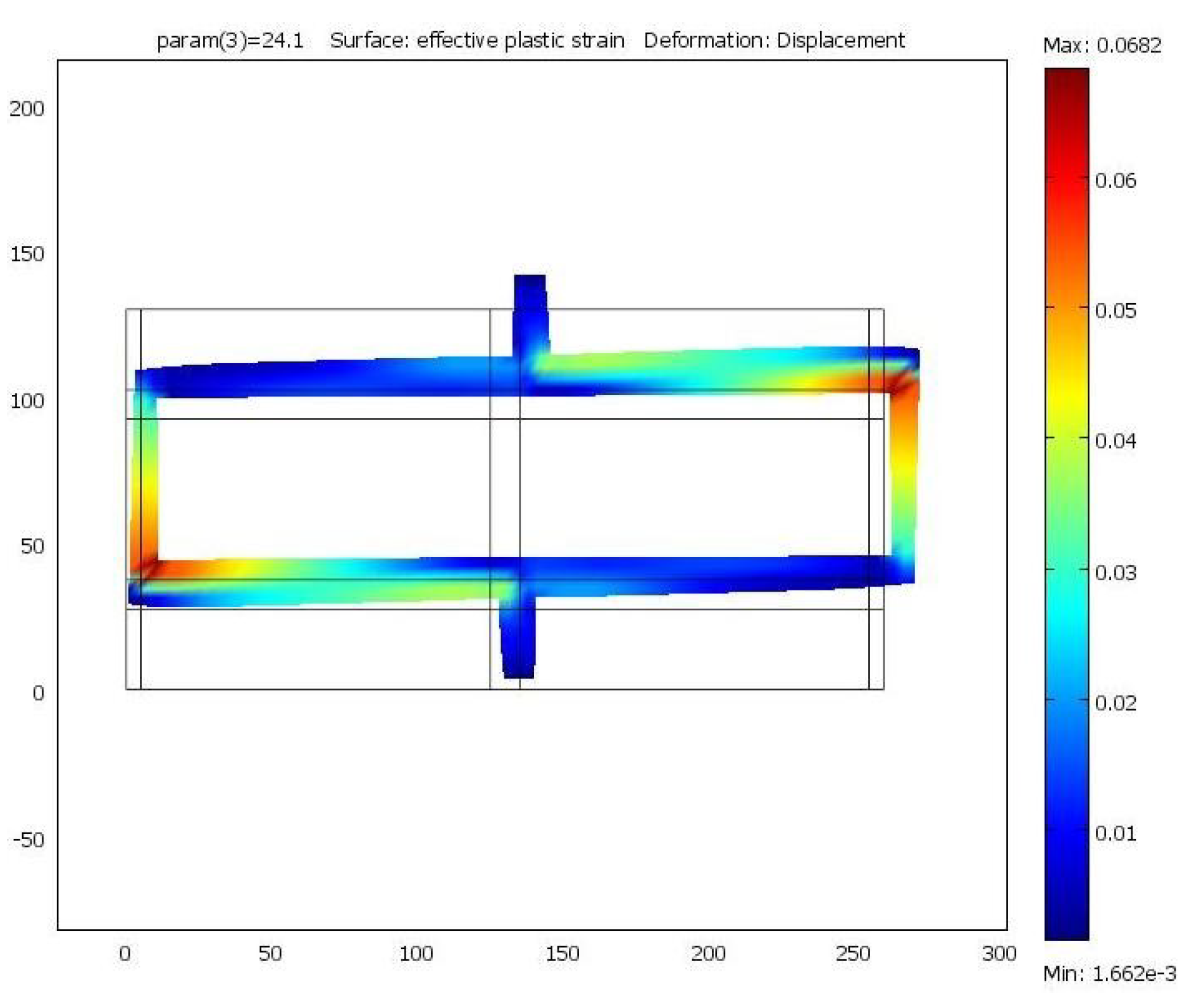

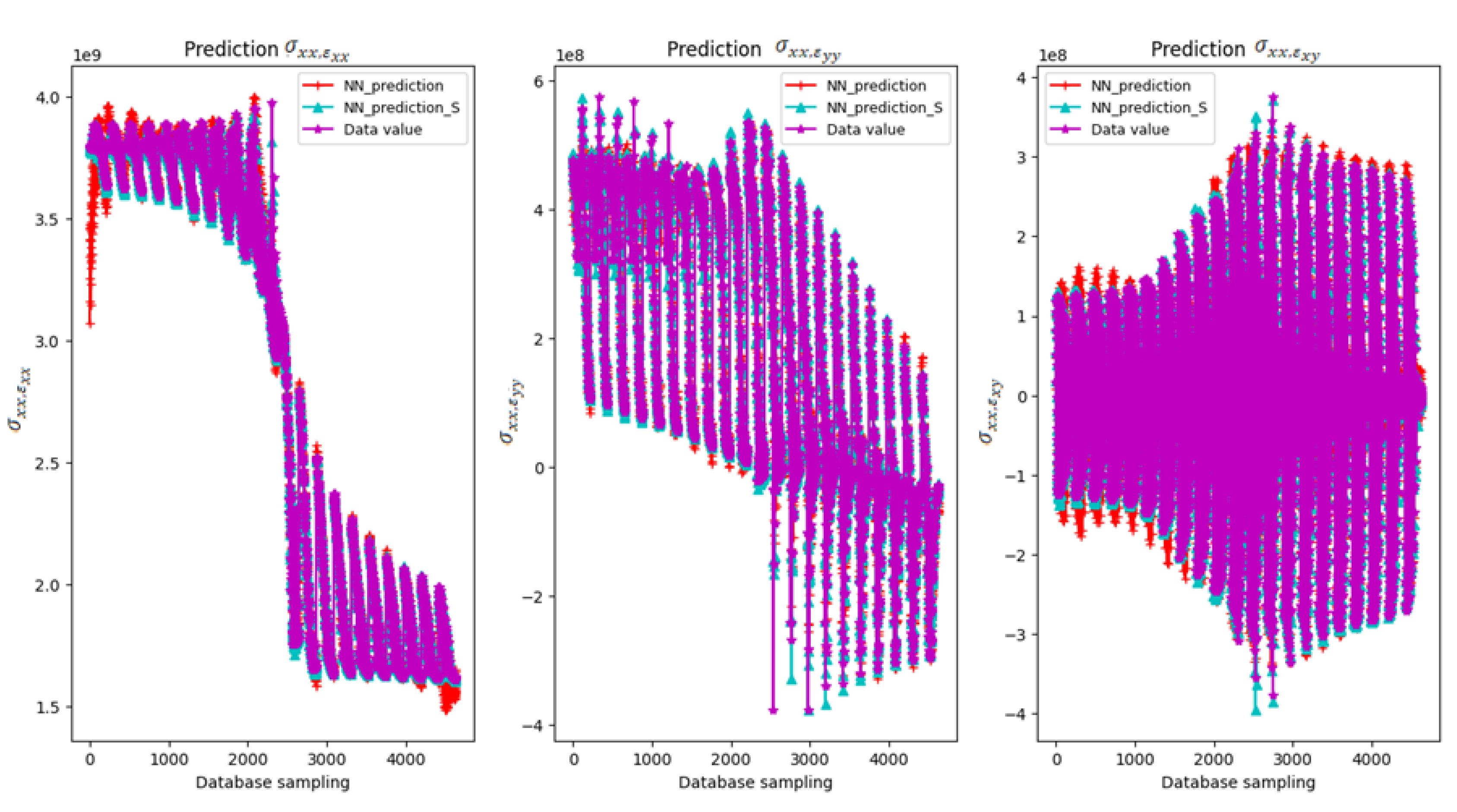

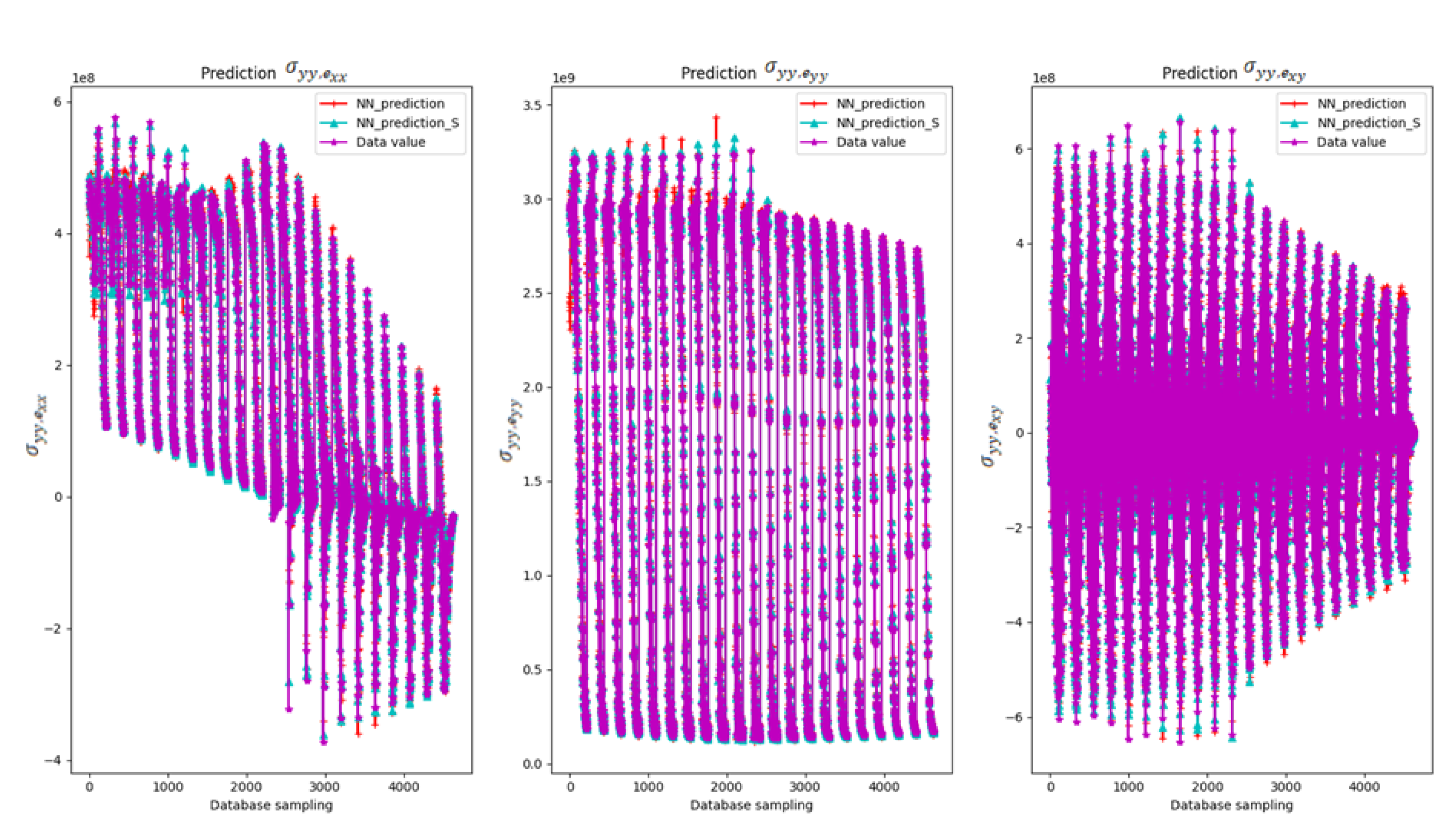

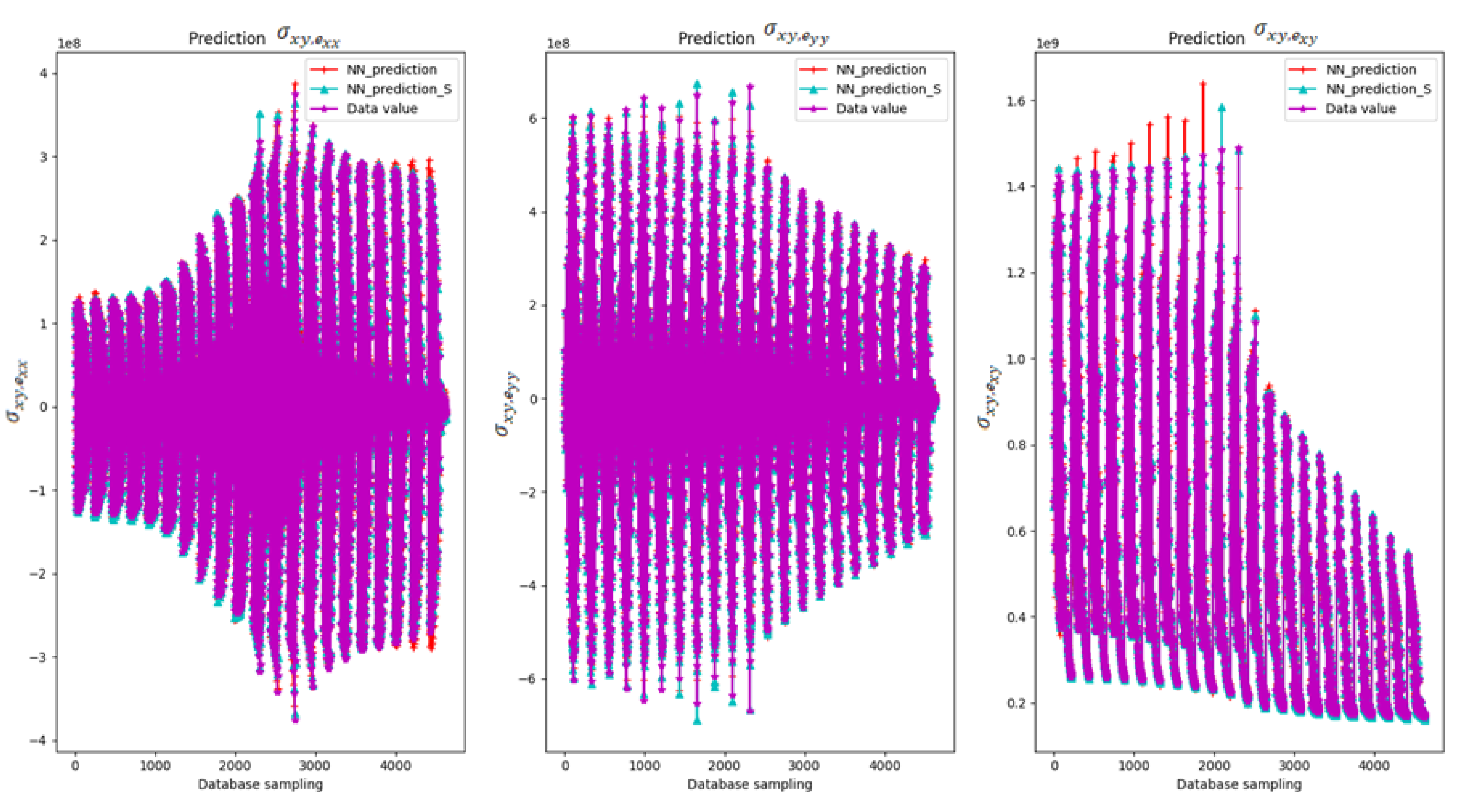

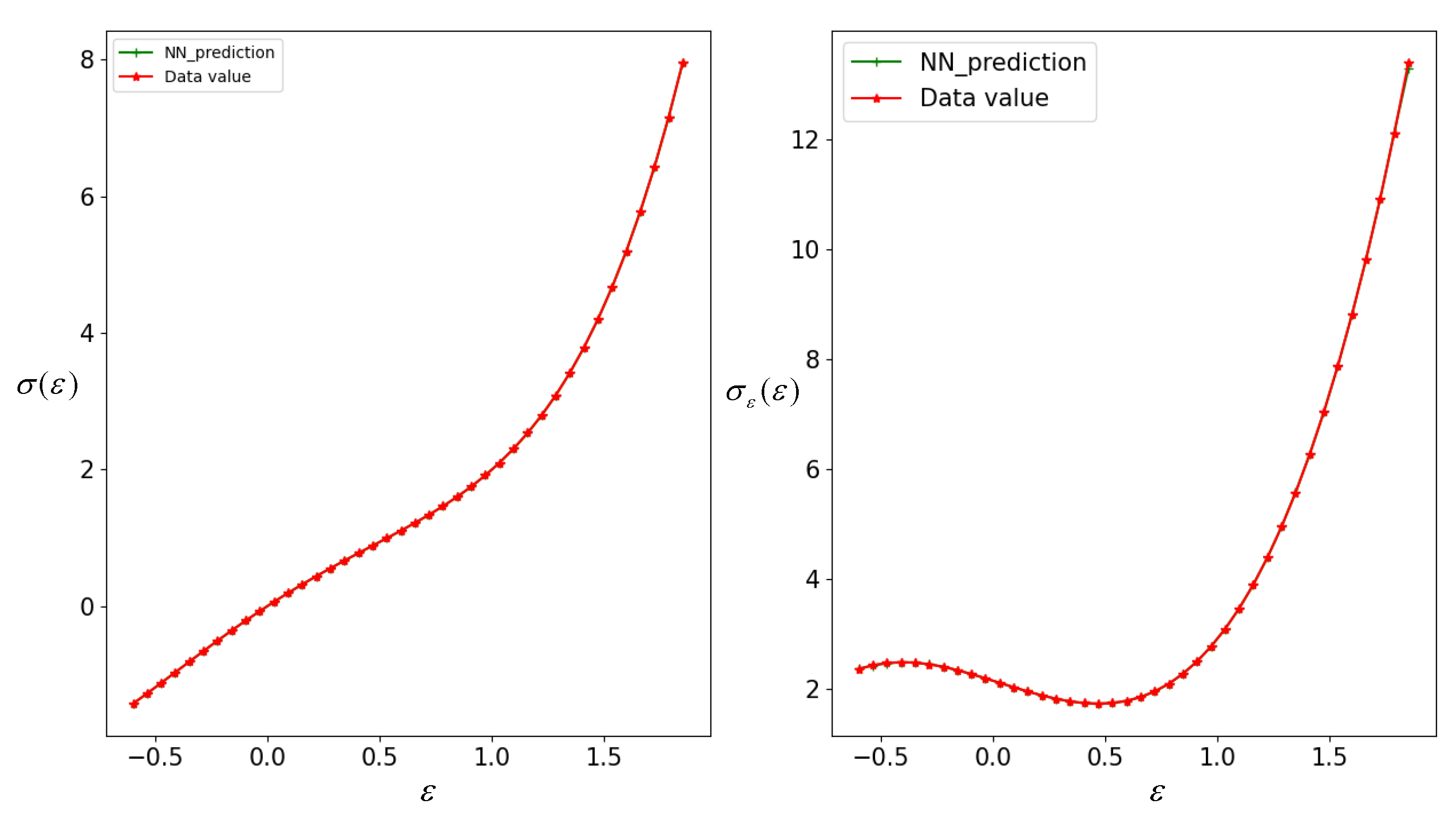

5. Numerical Results

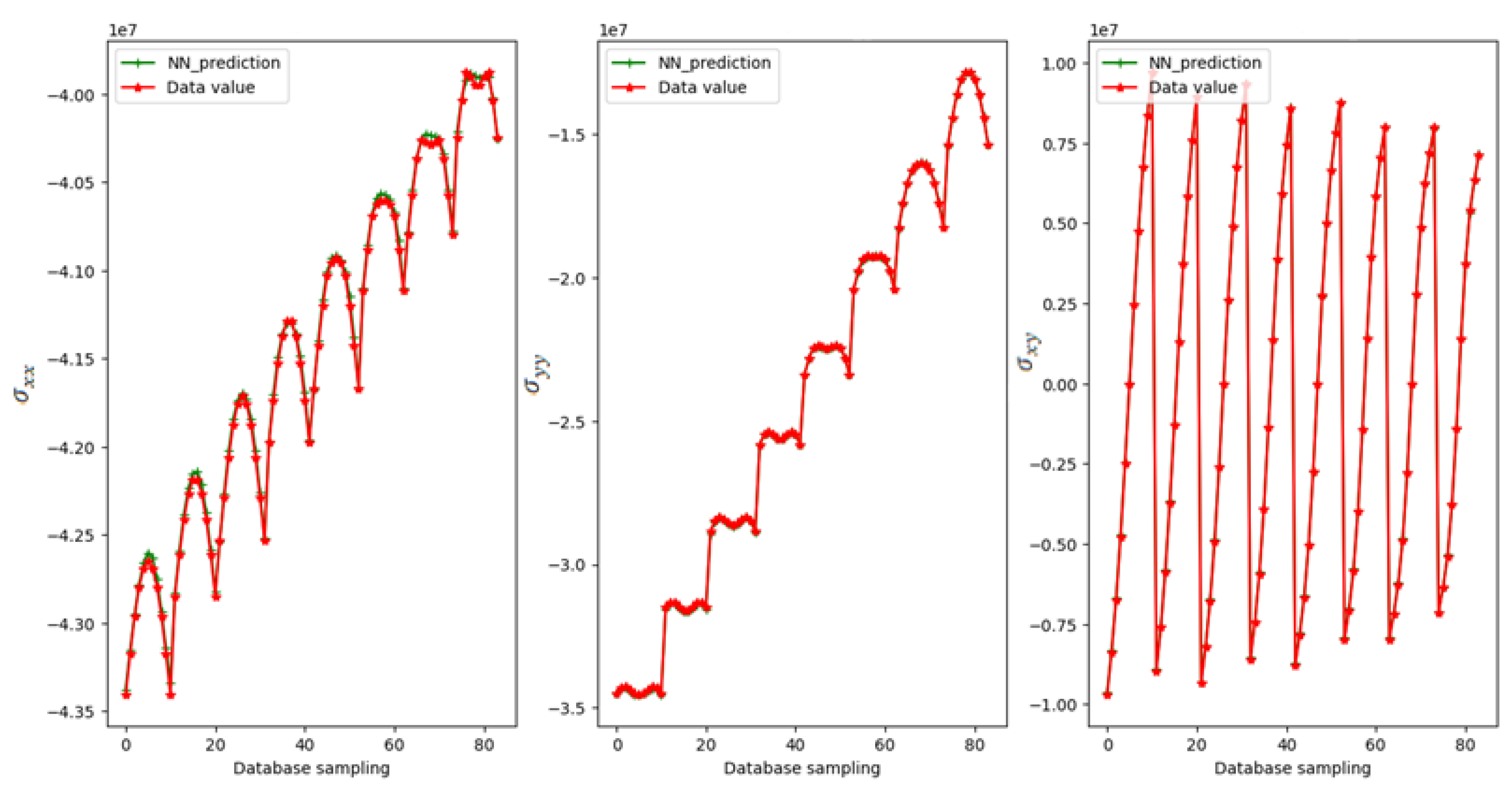

Example 1.

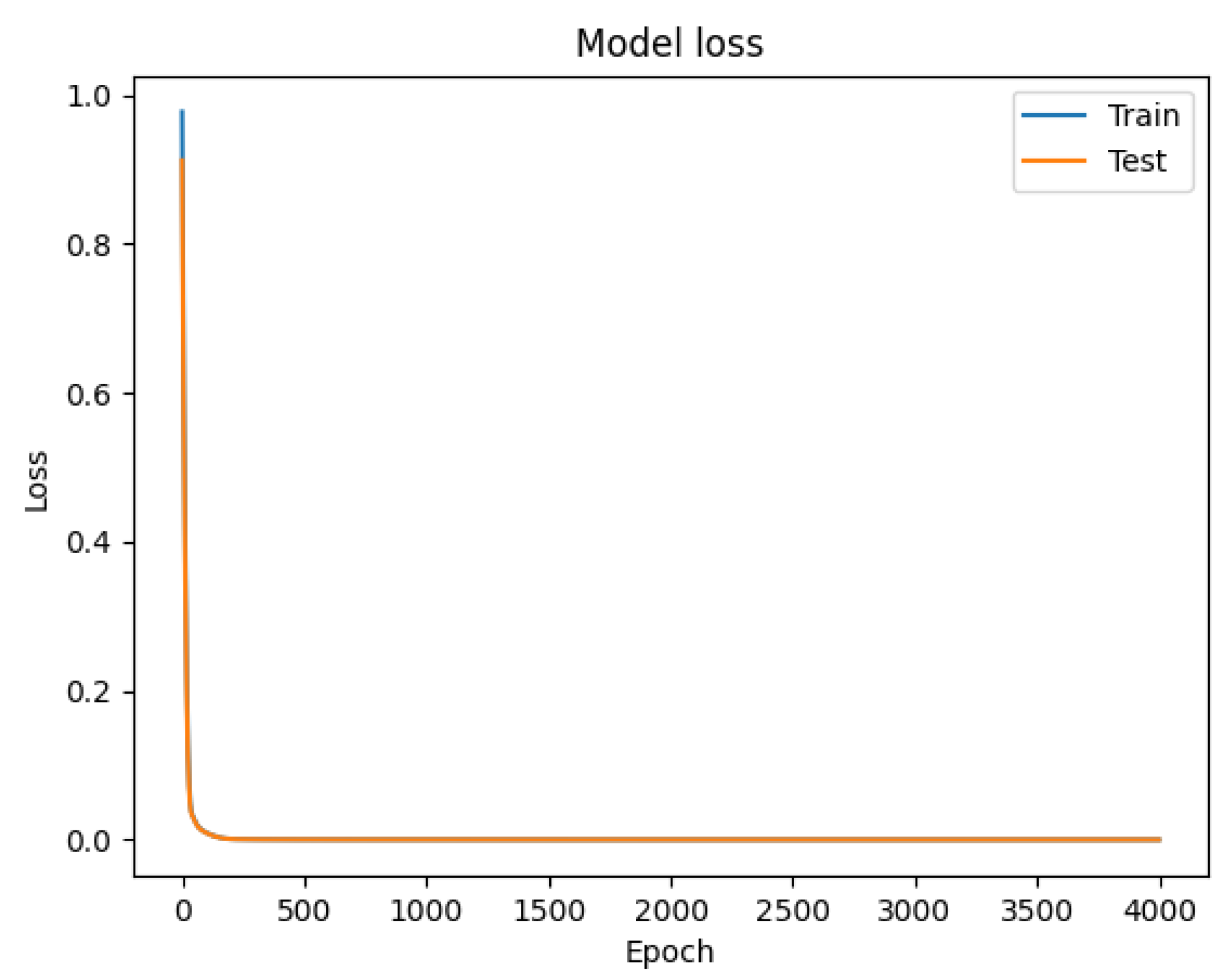

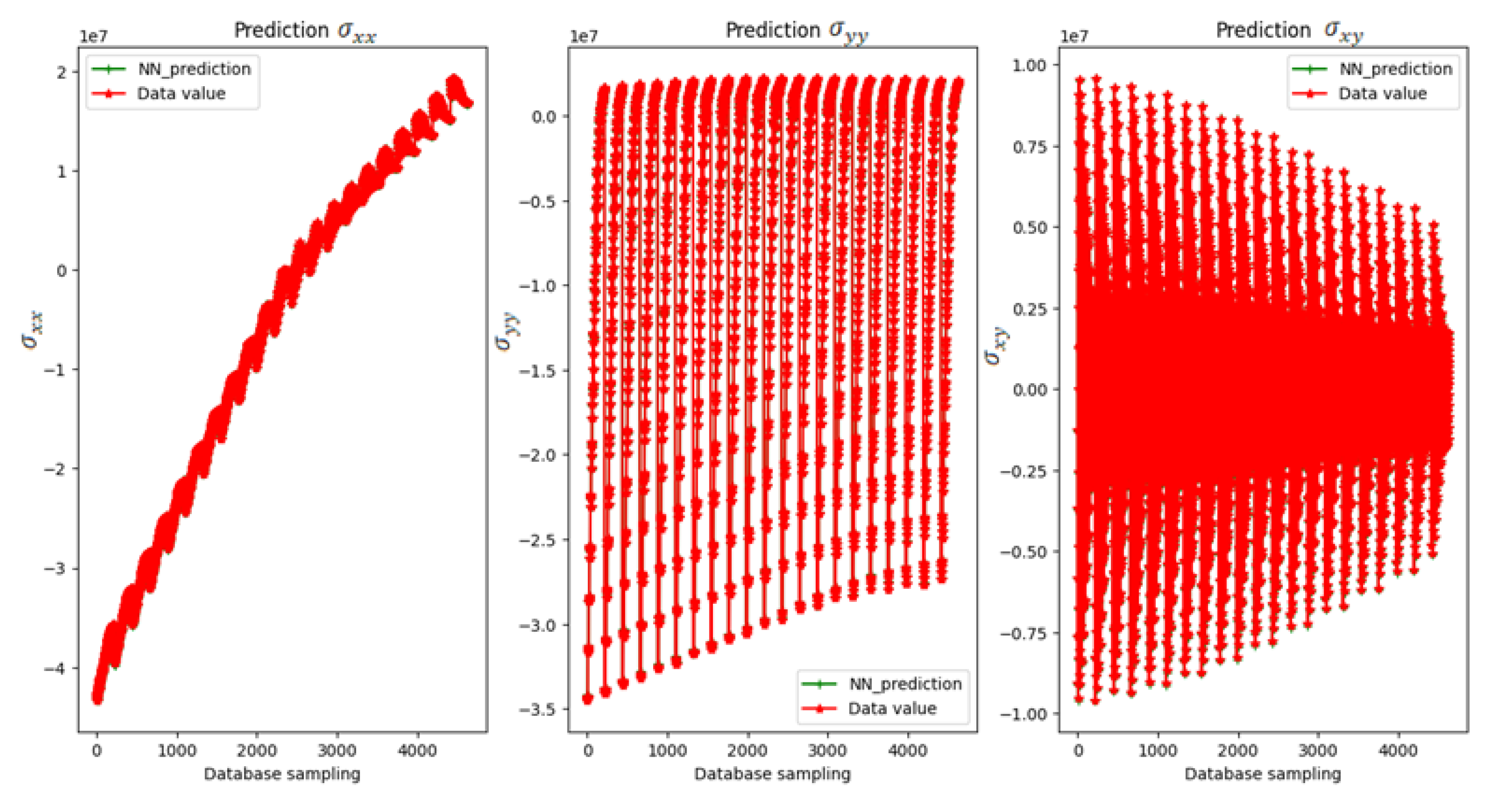

Example 2.

Example 3.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Drosopoulos G., A. , Stavroulakis G. E., Non-linear Mechanics for Composite, Heterogeneous Structures, CRC Press, Taylor and Francis, 2022.

- Urbański, A. , The unified, finite element formulation of homogenization of structural members with a periodic microstructure, Cracow University of Technology, 2005.

- Geers, M.G.D. , Kouznetsova V. G., Brekelmans W.A.M., “Multi-scale computational homogenization: Trends and challenges”, J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2010, 234, 2175–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Kortesis, S. and Panagiotopoulos P. D., Neural networks for computing in structural analysis: Methods and prospects of applications, Int. J. for Num. Meth. in Eng. 1993, 36, 2305–2318. [Google Scholar]

- Avdelas, A.V. , Panagiotopoulos P. D. , Kortesis S., Neural networks for computing in the elastoplastic analysis of structures, Meccanica 1995, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stavroulakis G., E. , Avdelas A., Abdalla K. M., Panagiotopoulos P. D. A neural network approach to the modelling, calculation and identification of semi-rigid connections in steel structures, J. of Constructional Steel Research 1997, 44(1–2), 91-105.

- Stavroulakis, G. , Bolzon G, Waszczyszyn Z. and Ziemianski L. Inverse analysis. In: Karihaloo B, Ritchie RO, Milne I (eds in chief) Comprehensive structural integrity, Numerical and computational methods 2003, 3, Chap–13, Elsevier,Amsterdam,685–718. [Google Scholar]

- Stavroulakis G., E. Inverse and identification problems in mechanics. Springer / Kluwer Academic 2000.

- Waszczyszyn, Z. and Ziemiański L., Neural Networks in the Identification Analysis of Structural Mechanics Problems. In: Mróz Z., Stavroulakis G.E. (eds), Parameter Identification of Materials and Structures, CISM International Centre for Mechanical Sciences (Courses and Lectures), 2005; 469, Springer, Vienna.

- Muradova A., D. , Stavroulakis G. E., The projective-iterative method and neural network estimation for buckling of elastic plates in nonlinear theory, Comm. in Nonlin. Sci. and Num. Sim. 2007, 12, 1068–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Yagawa G, Oishi A. Computational mechanics with neural networks, Springer, 2021.

- Dornheim, J. , Morand L. , Nallani H. J., Helm D., Neural Networks for Constitutive Modeling: From Universal Function Approximators to Advanced Models and the Integration of Physics, Arch. of Comp. Meth. in Eng. 2024, 31, 1097–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linka, K. , Hillgärtner M. , Abdolazizi K. P., Aydin R. C., Itskov M., Cyron Ch. J. Constitutive artificial neural networks: A fast and general approach to predictive data-driven constitutive modeling by deep learning, Journal of Computational Physics 2021, 429, 110010. [Google Scholar]

- Linka, K. , Kuhl E. , A new family of Constitutive Artificial Neural Networks towards automated model discovery, Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg. 2023, 403, 115731. [Google Scholar]

- Haghighat, E. , and Juanes, R. Sciann, A keras/tensorflow wrapper for scientific computations and physics-informed deep learning using artificial neural networks, Comput. Meth. in Appl. Mech.s and Eng. 2021, 373, 113552. [Google Scholar]

- Baydin, A. , Pearlmutter B. A., Radul A. A., Siskind J. M., “Automatic Differentiation in Machine Learning: a Survey”, 2018, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1502.05767.pdf.

- Czarnecki W., M. , Osindero S., Swirszcz M. J. G., and Pascanu R., “Sobolev Training for Neural Networks”, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.04859.

- Michel J-C. , Moulinec H., Suquet P., Effective properties of composite materials with periodic microstructure: a computational approach, Comput. Meth. Appl. Mech. Eng. 1999, 172, 109–143.

- Zohdi, T.I. , Wriggers P., An introduction to computational micromechanics. Springer, Berlin, 2008.

- Tikarrouchine, E. , Benaarbia A. , Chatzigeorgiou G., Meraghni F., Non-linear FE2 multiscale simulation of damage, micro and macroscopic strains in polyamide 66-woven composite structures: Analysis and experimental validation, Composite Structures 2021, 255, 112926. [Google Scholar]

- Drosopoulos G., A. , Giannis K., Stavroulaki M.E., Stavroulakis G. E., Metamodeling-assisted numerical homogenization for masonry and cracked structures, ASCE Jr. of Eng. Mech. 2018, 144(8), art. no. 04018072.

- Drosopoulos G., A. , Stavroulakis G. E., Data-driven Computational Homogenization Using Neural Networks: FE2-NN Application on Damaged Masonry, ACM Jr. on Comp. and Cultural Heritage 2020, 14(1), 1-19.

- Yvonnet, J. , He Q. C., Li P., Reducing internal variables and improving efficiency in data-driven modelling of anisotropic damage from RVE simulations, Comput. Mech. 2023, 72, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Le, B.A. , Yvonnet J. , He Q.-C. , Computational homogenization of nonlinear elastic materials using neural networks, Int. J. for Num. Meth. in Eng. 2015, 104(12), 1061–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Urbański, A. , Szymon l. , Marcin D., Multi-scale modeling of brick masonry using a numerical homogenization technique and an artificial neural network, Arch. of Civil Eng. 2022, 68(4), 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Eivazi H., Tröger J.-A., Wittek S., Hartmann S., Rausch A., “FE2 Computations With Deep Neural Networks: Algorithmic Structure, Data Generation, and Implementation” (June 07, 2023). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4485434 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4485434. [CrossRef]

- Fish, J. , Yu Y. , Data-physics driven reduced order homogenization, Int. J. Numer. Methods Engrg. 2023, 124(7), 1620–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- As’ ad, F. , Avery P. , Farhat C., A mechanics-informed artificial neural network approach in data-driven constitutive modeling, Int. J. Numer. Methods Engrg. 2022, 123(12), 2738–2759. [Google Scholar]

- Protopapadakis, E. , Schauer, M. , Pierri, E., Doulamis, A. D., Stavroulakis, G. E., Böhrnsen, J.-U., Langer, S., A genetically optimized neural classifier applied to numerical pile integrity tests considering concrete piles, Computers and Structures 2016, 162, 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Muradova A.D., Stavroulakis G.E., Physics-informed neural networks for elastic plate problems with bending and Winkler-type contact effects, J. of the Serbian Society for Comput. Mech. 2021, 15(2), 45-54.

- Mouratidou A., D. , Drosopoulos G. A., Stavroulakis G. Ensemble of physics-informed neural networks for solving plane elasticity problems with examples, Acta Mechanica, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E. , Kevrekidis I. G., Lu L. et al., “Physics-informed machine learning”, Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikis, D. , Muradova A. D. and Stavroulakis G. S., A Gentle Introduction to Physics-Informed Neural Networks, with Applications in Static Rod and Beam Problems, J. of Adv. in Appl. & Comput. Math. 2022, 9, 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X. , Giovanis D.G., Yvonnet J., Papadopoulos V., Detrez F., Bai J., A data-driven computational homogenization method based on neural networks for the nonlinear anisotropic electrical response of graphene/polymer nanocomposites, Comput. Mech. 2019, 64(2), 307-321.

- Fish, J. , Wagner G.J., Keten S., Mesoscopic and multiscale modelling in materials. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchalla, A. , Belouettar S. , Makradi A., Zahrouni H., An ABAQUS toolbox for multiscale finite element computation, Composites Part B: Engineering 2013, 52, 323–333. [Google Scholar]

- Wei H., Wu C.T., Hu W. et al., LS-DYNA Machine Learning–Based Multiscale Method for Nonlinear Modeling of Short Fiber–Reinforced Composites, J. of Eng. Mech. 2023, 149(3).

- Tung-Huan Su and others, Multiscale computational solid mechanics: data and machine learning, J. of Mech. 2022, 38, 568–585.

- Fei, T. , Xin L. , Haodong D., Wenbin Y., Learning composite constitutive laws via coupling Abaqus and deep neural network, Composite Structures 2021, 272, 114137. [Google Scholar]

- Stavroulakis G., E. , Konstadinos G., Drosopoulos G. A., Stavroulaki M. E., Non-linear Computational Homogenization Experiments, Proc. COMSOL Conference 2013 Rotterdam: https://www.comsol.de/paper/download/182535/stavroulakis- paper.pdf.

- Barron A. R., Approximation and Estimation Bounds for Artificial Neural Networks, Machine Learning 1994, 14, 115-133.

- Ruder, S. An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms 2017,https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.04747.

- Abadi, M. , Barham P., Chen J., Chen Z., Davis A., Dean J., Devin M., Ghemawat S., Irving G., Isard M., Kudlur M., Levenberg J., Monga R., Moore S., Murray D.G., Steiner B., Tucker P., Vasudevan V., Warden P., Wicke M., Yu Y., Zheng X., Tensorflow: A system for large-scale machine learning, in: 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 16), USENIX, Association, Savannah, GA, 2016, 265–283, URL https://www.usenix.org/conference/osdi16/technical-sessions/presentation/abadi.

- Dastjerdi, S. , Alibakhshi A., Akgöz B., Civalek O., Novel Nonlinear Elasticity Approach for Analysis of Nonlinear and Hyperelastic Structures, Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements, 2022, 143, 219-236.

| 1 | The programming code is available from the supplemental material as an open source. |

| Number of Layers | Neurons | Epochs | Training samples | MSE | Time (min.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | [40,40] | 2000 | 42 | 3 | |

| 2 | [40,40] | 4000 | 42 | 6 | |

| 3 | [15,30,40] | 2000 | 42 | 5 | |

| 4 | [15,20,15,20] | 4000 | 84 | 8 | |

| 4 | [15,20,15,20] | 8000 | 84 | 15.5 |

| Number of Layers | Neurons | Epochs | Batch size | MSE | Time (min.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | [15,15] | 1000 | 64 | 13.64 | |

| 2 | [15,15] | 2000 | 64 | 27.62 | |

| 2 | [40,40] | 2000 | 64 | 27.30 | |

| 2 | [40,40] | 2000 | 84 | 26.43 | |

| 3 | [15,30,15] | 4000 | 84 | 52.48 | |

| 4 | [15,20,15,20] | 2000 | 84 | 26.31 | |

| 4 | [30,40,30,40] | 2000 | 84 | 26.79 | |

| 5 | [15,20,15,20,15] | 2000 | 84 | 26.27 | |

| 5 | [15,20,15,20,15] | 4000 | 84 | 52.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).