1. Introduction

Radical environmental protests have increased in recent years (Barkela et al. 2022), with an increasing range of actions - symbolic forms of protest and tactics disruptive of the public and industry - used both in the United Kingdom, where the survey reported here was conducted in late 2024 to early 2025, and globally (Kenward and Brick 2024, Gordon 2024). Furthermore, it seems that a concern central to global environmental sustainability feeds such protests - at the growing gap between evidence of accelerating anthropogenic climate change, species and habitat loss (the ‘nature crisis’) and the limited scale of government action – is only likely to grow as progress towards net zero and agreement on biodiversity conservation measures falter, and major actors such as the United States withdraw from international treaties and reverse climate change mitigation policies. Thus, the global stage is set for a growing radicalization of environmental protest.

One scientific response to this situation has been to examine the impact of radical protest forms on public support for environmental causes. Do radical protests tend to broaden public support (see e.g., Simpson et al., 2022, Ostarek et al. 2024), or rather to alienate the wider public (see e.g., Foxe at al. 2024)? Or does the effect largely depend on context (see e.g., Sprengholdz and Meier 2024)? Another important avenue of enquiry has been to examine the role of emotions in support and mobilization for such protests (see e.g., Landmann and Rohmann 2020, Martiskainenen et al. 2020, Adams et al. 2020, Matejova and Merkeley 2022).

To date, however, less attention has been paid to the underlying beliefs which support radical protest for environmental causes (though see Morgan et al. 2024, Splash 2006). In particular, work on how perceptions of human-nature relations impact support for radical protest has been lacking. To address this our survey was designed to identify beliefs associated with support for radical protest and to examine the relationship between them, from perceptions of self and governmental efficacy (Meijers et al. 2023) to individuals’ sense of their relationship to nature – and hence to address the question of whether radical ideas (such as anti-speciesism – belief in the equality of species) lead to radical actions.

2. Literature Review

(i) Perceptions of the Human-Nature Relationship and Anti-Speciesism

Is nature to be regarded as a resource for humans to use to their best advantage, or rather as having its own interests and intrinsic value which humanity should safeguard? Do we see ourselves as in some way separate to and apart from nature – whether through our evolved intellectual capacities, our technologically wrought material culture or created so by divine fiat – or as thoroughly, inextricably and inseparably entwined within it? And what might be the implications of our answers to these questions for our willingness to take radical steps to defend or restore nature? The New Enviromental Paradigm scale (NEP, Dunlap and van Liere 1978) was designed to position people on a spectrum of opinion related to the first pair of questions, while, using the NEP and other tools, we have sought to answer the third question through our survey.

The NEP aims to capture what Dunlap and van Liere identified as a new approach to environment emerging from the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s and a growing awareness of the fragility of ecological systems and the extent of human impacts upon them (Dunlap et al. 2000: 427). Counterposed to what they frame as the dominant social paradigm (DSP) which emphasizes the use value of nature for human purposes, over the next two decades the ecologically embedded NEP outlook gained traction as new evidence emerged of human impacts on nature at a planetary scale, including the depletion of the ozone layer, global deforestation and mounting evidence of anthropogenic climate change. During the same period, the NEP scale was validated and used by a growing number of studies in diverse settings in terms of nation and culture, e.g., Canada (Edgell & Nowell, 1989), Sweden (Widegren, 1998), the Baltic states (Gooch, 1995), Turkey (Furman, 1998), and Japan (Pierce et al., 1987), and by social and environmental scientists from different disciplinary backgrounds (see e.g., Stern et al. 1995, Pierce et al. 1992). Through this work high scores on the NEP were shown to be consistently positively related to a wide range of pro-environmental beliefs and attitudes (Dunlap et al. 2000: 428-9).

In 2000 Dunlap et al. published a revised version of the scale to reflect changes in language use and scientific developments (e.g., increased evidence of the global scale of anthropogenic impacts) during the 1980s and 1990s into the scale, with the revised 15 item scale (8 items pro-NEP, now re-named New Ecological Paradigm, 7 pro-DSA) shown to have a high degree of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83, ibid., 434) and adopted here (see Materials and Methods below).

Over the subsequent 25 years the revised NEP has become the most widely used measure of a pro-environmental orientation or ecological worldview (Amburgey and Thoman 2012: 236), although debate continues concerning its dimensionality - whether it is best regarded as a unitary scale or rather as a series of related subscales (ibid.). We were particularly interested in items designed to capture the dimensions of ‘antianthropocentrism’ and ‘rejection of exemptionalism’ - ‘the idea that humans—unlike other species—are exempt from the constraints of nature’ (2000: 432) hypothesized by Dunlap et al. in their re-design of the scale (ibid. 432), as these seem to us to best capture the displacement of human interests from the center of decision-making and rejection of special pleading on their behalf that might support radical environmental protest.

While the revised NEP has become the most widely used measure of an ecological worldview, it emphasizes cognition over affect, which has also been shown to be important in supporting and motivating environmental activism. (see e.g., Landmann and Rohmann 2020, Martiskainenen et al. 2020, Adams et al. 2020, Matejova and Merkeley 2022). To more fully address emotional aspects of the human-nature relationship, we therefore also used the Connectedness to Nature scale (CNS, Mayer and Frantz 2004). While not as widely used as the NEP, the scale has been validated across a broad range of cultural contexts (including Italy, Turkey, China and India) and user groups, including tourists, consumers, farmers and addiction sufferers (Lovati et al., 2023; Çiğdemli and Avci 2023; Gawrych 2022; Choudary and Sharma 2022). The CNS builds on work by social psychologists showing the importance of people’s sense of connection to and identification with social groups in motivating their behavior, extending this to the natural world. As they argue, ‘the deep motivation that comes from a sense of ‘we-ness’ is one of the few psychological forces strong enough to compete with the prevailing counter-forces required to engage in environmentally responsible behavior .’ (Frantz and Mayer 2014: 86). Hence, the CNS is designed to ‘measure people’s sense that they are egalitarian members of the natural world’ (ibid.). The CNS consistently correlates with self-reported and to predict actual environmentally responsible behaviour, , independently of NEP variables (ibid. 87).

Several items in the CNS and NEP reflect anti-speciesist beliefs, that is beliefs that humans are fully a product of, embedded in and dependent upon natural systems, and should not be privileged over other species (Turina 2018, Munro 2024). We suggest that such beliefs are indicative of a radical environmentalist position (though not of all radical environmentalist beliefs), and postulate that the presence of such beliefs will be associated with support for radical environmental protests.

(ii) Self and Governmental Efficacy: Beliefs in the Capacity to Effect Change

Part of our reason for undertaking the survey was to validate scales to enable comparative measurement of stakeholder beliefs and capabilities for an agent-based computer model of a social-ecological land–use decision making system, so we needed items that assess not only the motivations but also the opportunities and abilities that stakeholders perceive themselves to have. To do this we developed our own scale, based on the MOA framework (motivation, opportunity, ability, MacInnis et al. 1991) and previous modelling experience, but also informed by work on self, collective and governmental efficacy (for a synthetic review see Meijers et al., 2023). Independent of our particular modelling goal, we argue that measuring perceptions of opportunity and capacity for meaningful and/or impactful environmental action is important, because however well motivated an individual might be, if they feel that they have no opportunities to take effective action or for their voice to be heard, they may refrain from ERB or their support for protest may be weakened; conversely if they believe they will be heard by those with power and can make a difference themselves, they are likely to be motivated to act, and to support others engaged in such actions.

From their comprehensive review of the multidisciplinary efficacy literature Meijers et al., distinguish 7 types of efficacy, 4 concerning capabilities to engage in a pro-environmental actions (as an individual, collectively, as an individual in the governmental sphere (internal governmental efficacy’), and in the government’s propensity to respond to citizen demands (‘external governmental efficacy’), and 3 concerning the effectiveness of actions in achieving the desired environmental goals at individual, collective and governmental levels (personal, collective and governmental response efficacies respectively; ibid., 3). Results showed that internal governmental efficacy (feeling able to participate in political processes) and external governmental efficacy (seeing opportunities provided by the government to do so) most strongly predicted intentions for public pro-environmental behavior and policy support (ibid., 8). Hence, Meijers et al. recommend that the ‘inclusion of efficacy beliefs on a governmental level in future research could be fruitful and maybe necessary to model pro-environmental action’ (ibid- 9. We followed this recommendation in our selection of efficacy measures (see Materials and Methods).

(iii) Support for radical protest forms

Work on support for radical environmental actions notes how in contrast to supporters of other radical causes, environmental radicals tend to distinguish sharply between violence against the person and property (‘ecotage’; ecologically motivated sabotage), and that ‘nonviolence is a key value and tactic within the climate movement’ (Jansma et al

. 2025: 1; see also Hirsh-Hoefler and Mudde 2014). Within this context, the literature tends to focus on which actions activists are willing to engage in and under what circumstances (Tausch et al. 2011, Jansma et al., 2025). Measures of broader public support tend to be general and to focus on the attitude of the respondent rather than the reason for the support (e.g.

, ‘I feel it is justified that some climate groups use eco-sabotage as a strategy’ ‘I would respect climate groups that include eco-sabotage in their strategy’; Jansma et al. 2025, materials

https://osf.io/jr8bf). In contrast, we wished to capture something of the variety of reasons why members of the broader public may support disruptive and potentially or actually law-breaking actions for environmental causes. For this reason, we developed a 3-item scale (the principled support for radical environmental protest scale) based on reasons familiar to us from our fieldwork and the environmental literature. This was designed to capture support for direct action - which may or may not involve breaking the law, but is likely to be disruptive (Seeds for Change, 2022) - and for breaking the law, for different reasons: because the government won’t listen (in relation to direct action), for the sake of future generations and because current laws don’t adequately address environmental realities (in relation to support for law breaking).

3. Aims and Hypothesis Development

The aim of this study is to identify beliefs associated with support for radical protest and to examine the relationship between them.

RQ1: To what extent is support for radical protest forms linked to anti-speciesism beliefs and how is it related to other forms of pro-environmental behaviour?

H1: There will be a positive relationship between support for radical protest forms and other pro-environmental behaviors.

H2: Individuals with stronger anti-speciesism beliefs will report higher support for radical protest forms, even after accounting for other forms of pro-environmental behavior.

RQ2: To what extent does perceived governmental efficacy impact support for radical protest forms and how does it affect the relationship between anti-speciesism and support for radical protest forms?

H3 Individuals with higher perceived governmental efficacy will more likely support radical protest forms.

H4 Perceived governmental efficacy has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between anti-speciesism and support for radical protest forms such that higher perceived efficacy will strengthen the association.

4. Materials and Methods

This section provides information about the population, and sampling, scales used and the statistical analysis performed.

4.1. Participants and Design

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey from late December 2024 until early January 2025 in the UK facilitated by Bilendi. They undertook a panel survey that was representative of the national population by region, age, gender and educational background. The questionnaire contained a broader set of items than those used in this study.

The study sample consisted of 1163 participants (49.6% cisgender women, 50.4% cisgender men), with an average age of 43.47 (Standard deviation (SD) = 14.26) and a range from 18 to 74 years. Their residential settings were described by 19.4% as central in a large city, 22.4% as suburban in a large city, 8.9 as a small city, 33.9% as a town and 15.1% as a village or more rural and 0.3% replied with other residential settings. 29.4% had low educational qualifications (1-4 GCSEs or fewer), 34.7% medium EQs (5 or more GCSEs or apprenticeship), and 35.3% had a bachelors or masters degree or higher, with 0.6% in secondary or further education.

4.2. Materials

To measure our variables, we composed scales consisting of items extracted from well-established scales complemented with items developed to measure our concepts of interest. . All of our scales were tested for internal reliability and will be presented in the following paragraph. Unless otherwise indicated, the items were measured on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree.

Variables and Their Measurements

The anti-speciesism (AS) scale consisted of the following four items: Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist; Despite our distinctive characteristics (like advanced language and tool making), humans are still subject to the laws of nature; My connection to nature and the environment is a part of my spirituality; I feel very connected to all living things and the earth. The first two items are extracted from the New Ecological Paradigm scale (Dunlap et al., 2000) and the latter two from the Connectedness to Nature Scale [Mayer and Frantz 2004)]. The anti-speciesism scale showed acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α = .65). Items were measured on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1= strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree).

Engagement in pro-environmental private behavior (PEB-PR) was measured by presenting a list of 10 environmental behaviors in the private sphere (example: I try to reduce my waste and regularly separate it for recycling) to all of which the participants could indicate whether these actions apply to them with yes or no. This follows the Eurobarometer design (European Commission 2014, 2024) to enable broad comparison with European publics. The reliability of the dichotomous scale was assessed using Kuder-Richardson Formula 20 (KR-20) and showed an acceptable level of KR-20 = .67

Engagement in pro-environmental public behavior (PEP-PU) was assessed by presenting a list of seven environmental behavior in the public or political sphere (example: Sign a petition), to all of which the participants could indicate how likely they see themselves performing these actions in the next year. We selected items from Extinction Rebellion’s survey related to their campaign in London in April 2019 (Kenward and Brick 2024;

https://osf.io/7wna2). The scale had a good reliability (Cronbach’s α = .86).

Perceived governmental-efficacy (PGE) was investigated by 5 items: My local government provides opportunities for residents to contribute to decisions about the environment; I feel my opinions on environmental issues are heard and valued by my local government; I understand how decisions about new developments are made by the local government; I have the skills needed to influence decisions about environmental policies in my local government; I feel confident speaking up about environmental issues in public or with officials While the first two items were selected to assess external governmental efficacy, and the last three items aimed to measure internal governmental efficacy, resonating with the synthetic literature review by Meijers et al. (2023). However, exploratory factor analysis did not support this two-dimensional structure and demonstrated a unidimensional scale instead. Reliability was high (Cronbach’s α = .90).

Support for radical protest forms (PSREP) was measured with three items: If governments won’t listen, it becomes necessary to use direct action to protect the environment. Ultimately, protecting future generations is more important than obeying the law. Many current laws do not reflect environmental realities, so breaking them is justified. These items were chosen by drawing on our fieldwork experience and reading of the literature as outlined in the literature review, and showed good reliability (Cronbach’s α = .76).

4.3. Analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses for the collected variables including mean (M), SD as well as skewness and kurtosis. The latter provided information about the distribution and was part of further preliminary testing to confirm the assumptions needed for inferential analyses. Furthermore, we applied reliability analysis to assess internal consistency of all the scales. To test our hypotheses, we used correlation analysis (H1), single linear regressions (H2) and a multiple hierarchal linear regression model (H3), including a mediation analysis (H4). We used SPSS (IBM Copr., 2021) for these purposes.

5. Results

This section presents the study’s findings, beginning with the descriptive statistics of the collected variables, followed by the inferential analyses structured around the study’s hypotheses.

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

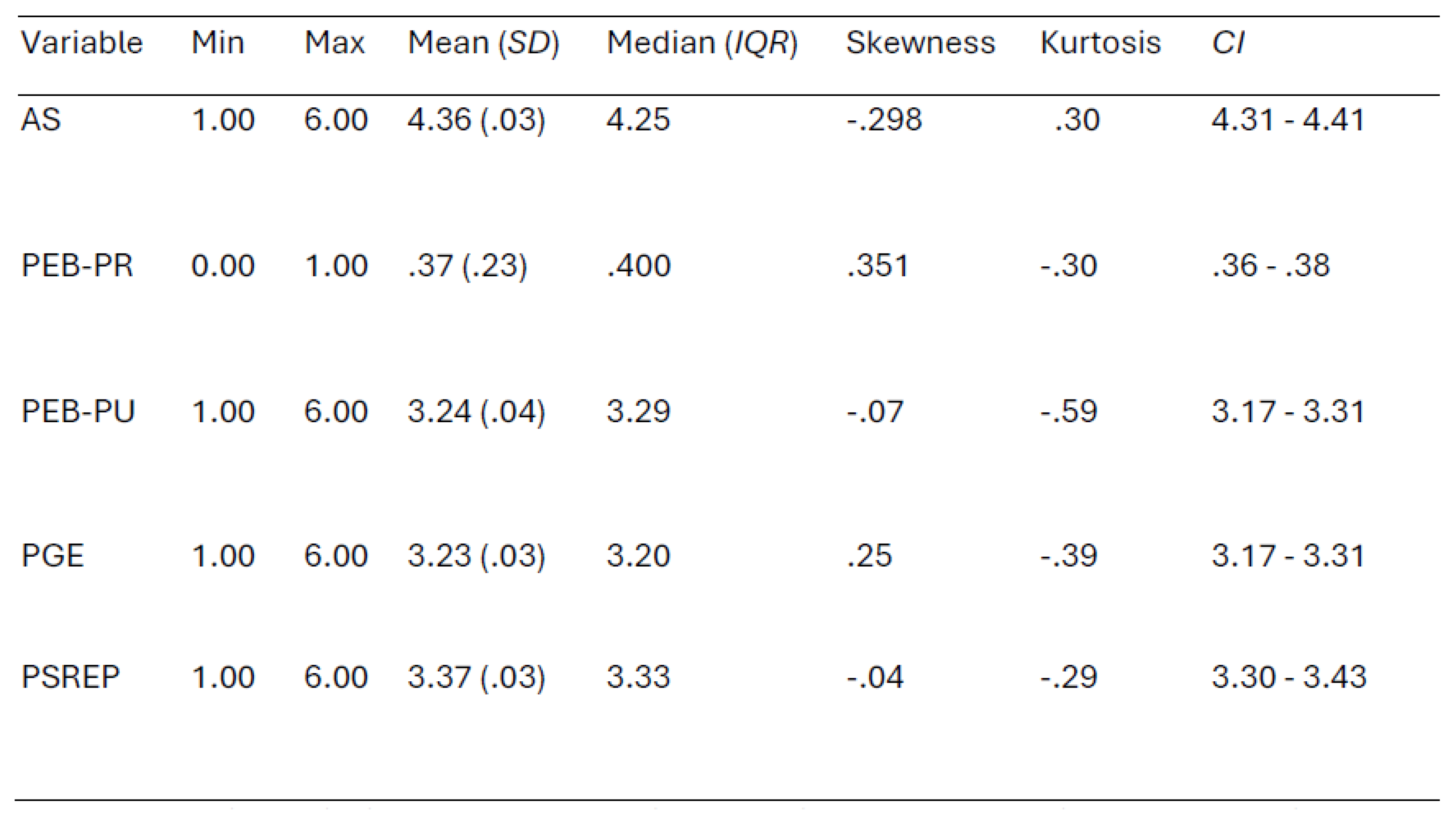

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of all variables. As displayed in the table, all variables had a reasonably normal distribution therefore met these assumptions for the hypothesis testing. Due to space, we will not report in detail about further assumption tests, but preliminary testing confirmed linearity, absence of multicollinearity, normality of residuals, homoscedascity and independence of errors.

For

Table 1 – see separate attachment.

As evident from the table, nearly all variables show skewness and kurtosis values within acceptable ranges, indicating they are approximately normally distributed. Values representing the distribution of private pro-environmental behavior reflect the dichotomous nature of the variable. Notably, all variables have means above the midpoint, suggesting moderate to positive responses across the board. Specifically, anti-speciesism and support for radical protest forms show the highest means, accompanied by low standard deviations, indicating relatively consistent and strong support for these attitudes.

5.2. Hypothesis Testing

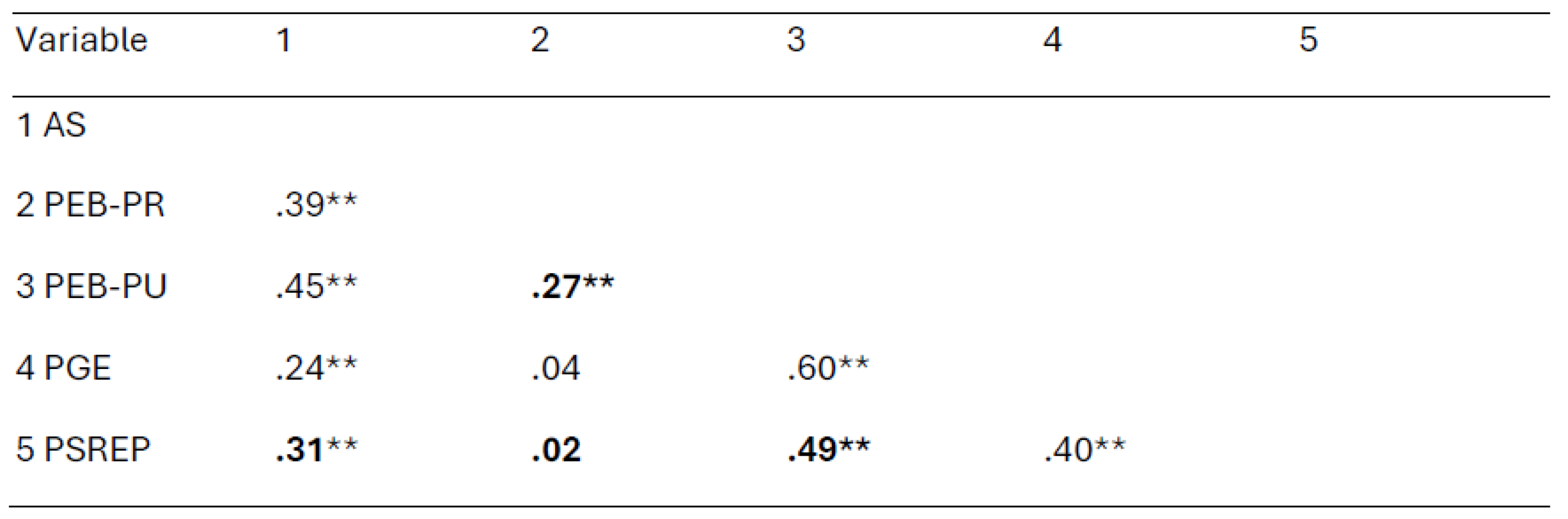

H1: There will be a positive relationship between support for radical protest forms and other pro-environmental behaviors.

To assess the link between the support of radical protest forms and other pro-environmental behavior we investigated the correlation between those. The hypothesis could only be partly verified as private pro-environmental behaviors and support for radical protest forms did not show a significant correlation. However, private pro-environmental behavior and public pro-environmental behavior were positively related (r = .27, p < .01) and so was public pro-environmental behavior and support for radical protest forms (r = .49, p < .01) with medium effect sizes.

While the hypothesis focused on the link between the correlation of the pro-environmental behaviors, we present correlations of all study variables in the correlation matrix in

Table 2 for comprehension.

For

Table 2 – see separate attachment.

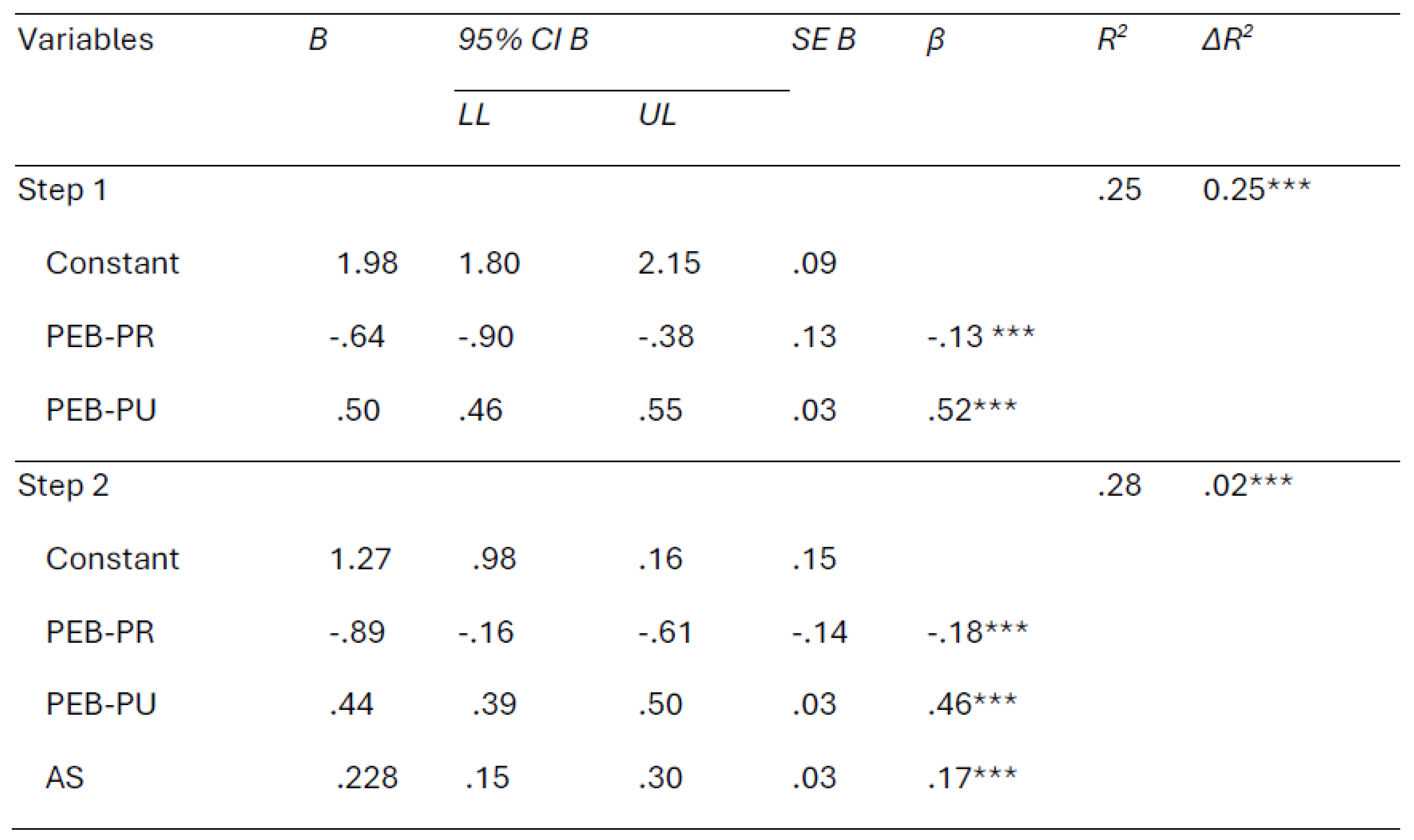

H2: Individuals with stronger anti-speciesism beliefs will report higher support for radical protest forms, even after accounting for other forms of pro-environmental behavior.

Anti-speciesism remained a significant predictor even after accounting for other variables (

β = .17

SE = .03,

t(1159) = 5.8,

p < .001)), supporting the hypothesis. However, the effect size was moderate. Additionally, the increase in explained variance was modest (ΔR² = .02, F(1, 1159) = 33.80, p < .001), indicating that anti-speciesism accounted for only a small portion of the variance in the dependent variable compared to the other predictors as evident in

Table 3.

Public pro-environmental behavior proved to be a strong positive predictor while private pro-environmental behavior negatively predicts support for radical protest forms. Due to different measurement forms, we recommend to consider β for reliable interpretation.

For

Table 2 – see separate attachment.

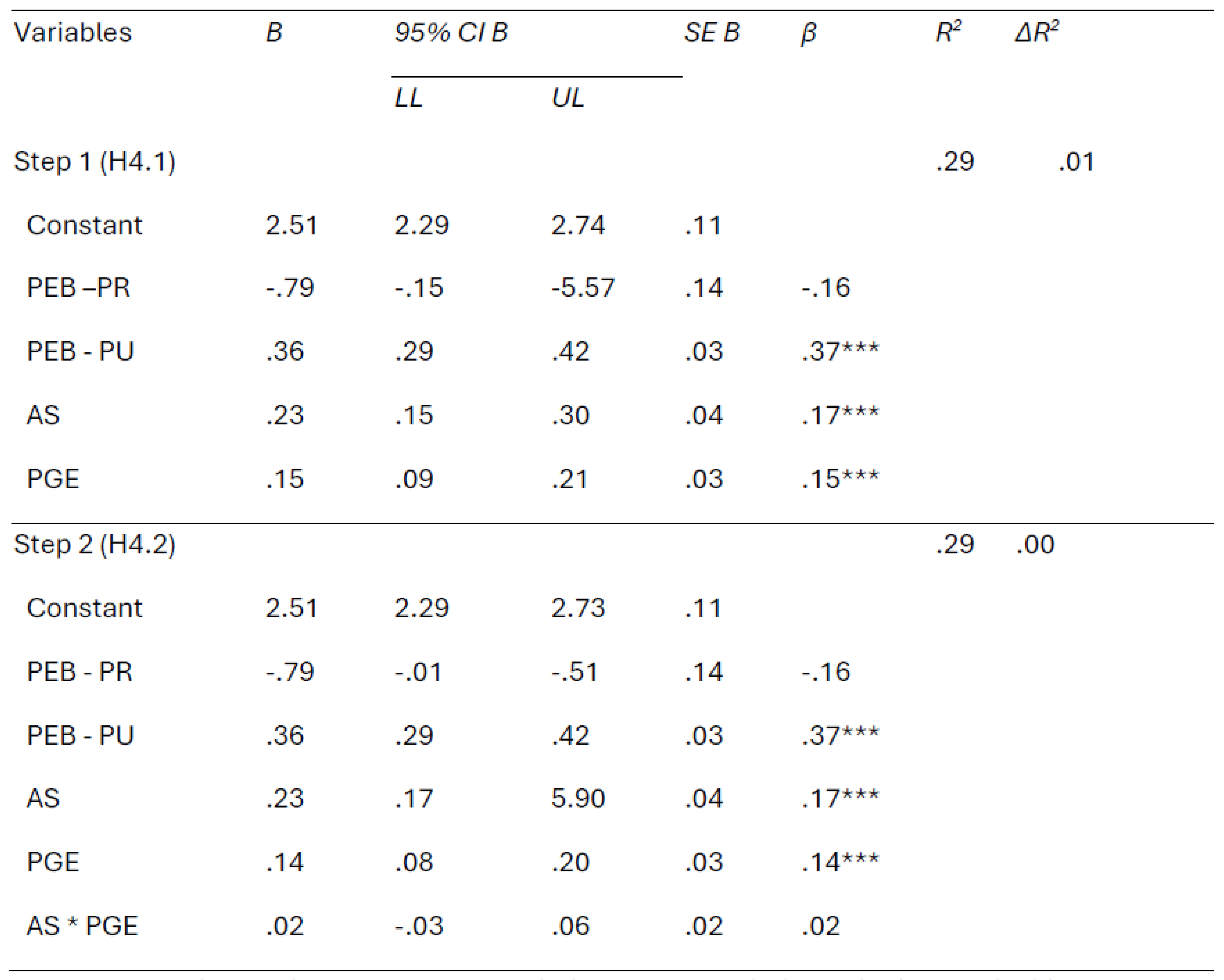

H3 Individuals with higher perceived governmental efficacy will be more likely to support radical envrionmentalenvironmental protest.

For this hypothesis we integrated perceived governmental efficacy as an additional independent predictor in the model to test 3. Results showed that perceived governmental efficacy functioned as a positive significant predictor for the support of radical protest forms after accounting for anti-speciesism and other pro-environmental behaviors (β = .17, SE = .02, t(1158) = 7.54, p < .001, R² = .29), meaning that higher perceived governmental efficacy predicted higher support for radical protest. This finding confirmed our hypothesis, based on the logic that individuals who believe they are able to act in the public sphere and the government may respond positively are more likely to support radical environmental protest, contrary to an expectation that support for radical action springs from disillusionment and alienation from the mainstream (Tausch et al. 2011). Interestingly, we find that private and public pro-environmental behaviors are both significantly associated with principled support for radical environmental protest, but in different directions, with private behaviors negatively associated and public behaviours positively linked.

H4 Perceived governmental efficacy has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between anti-speciesism and support for radical protest forms such that higher perceived efficacy will strengthen the association.

The interaction term of anti-speciesism and perceived governmental efficacy showed no significance (β = .02, SE = .02, t(1157) = -.71, p < .001, R² = .29, ), which indicated that perceived governmental efficacy had no moderating effect on the relationship between anti-speciesism and support for radical protest forms, rejecting hypothesis 4.

As is evident from

Table 4, perceived governmental efficacy contributed modestly to the model as an independent positive predictor but did not function as a moderator. Furthermore, adding the interaction term showed no increase in explained variance compared to the model with perceived governmental efficacy as an independent predictor (ΔR² = .00, F(1, 1159) = 51.00, p = .475).

For

Table 4 – see separate attachment.

5.3. Summary

In summary, results showed that anti-speciesism predicted support for radical protest forms, also when accounting for other pro-environmental behaviors. However, public pro-environmental behavior is a stronger predictor than anti-speciesism for support for radical protest forms whereas private pro-environmental behavior was a non-significant predictor in the final model (and respectively positive significant as a control variable). These findings indicate that the likelihood of a person’s support for radical protest forms most strongly increases when the person is already engaged in public activism compared to the lesser role of anti-speciesism beliefs and the role of private pro-environmental behavior which varied in valence and significance across models.

Perceived governmental efficacy proved to be a positive predictor. It suggests that people with higher belief in their own capability to influence political processes as well as in the responsiveness of their local government are more likely to engage in radical protest forms.

6. Discussion

6.1. The Central Role of Public-Pro Environmental Behavior

Public pro-environmental behavior emerges with a central role across the analyses. It is the strongest predictor of support for radical protest forms and has a strong link with perceived governmental efficacy. It also has the only reliable link with private pro-environmental behavior. We interpret and contextualize the role of public pro-environmental behaviour in the following section.

Public Pro-Environmental Behavior as an Arena of Environmentalist Ideas

Why should public environmental behaviour be the strongest predictor of support for radical environmental protest forms? One possibility is that engaging in such behaviour - signing a petition, supporting an environmental organisation, going on a protest march etc. - provides exposure to discourses and virtual or physical contact with others in the environmental movement who advocate and indeed engage in such actions. Public environmmental behaviour may thus provides a socialisation pathway towards normalisation of radical action repertoires, as well to radical discourses – such as anti-speciesism. This interpretation has implications for the question of the directionality of the relationship between anti-speciesism and public-pro environmental behavior, suggesting the latter leads to the former, which would fit with the weaker, negative relationship found between private pro-environmental behaviours and anti-speciesism, as this socialisation effect is absent.

The cross-sectional quantitative design of this study only allows speculation about this, but points to directions for future research to follow-up sub-groups who are publicly engaged to investigate the development of their beliefs, viewpoints and willingness to engage in more radical protest forms over time.

6.2. Support for Radical Protest Forms as a Strategic Form of Political Activism

We found perceived governmental efficacy to be a positive predictor of support for radical protest forms. This means that people who feel like they can have an impact into policialpolitical processes are more likely to show principled support for radical environmental protest. We raised the question if the support for radical protests forms gains momentum when citizens feel frustrated about the lack of impact of their other behavior on political decision processes – this could not be confirmed. In contrast, it seems as though support for radical protests forms is conditioned by the belief that it could have an impact. This challenges accounts which see radical activism as springing from disillusionment and disengagement from mainstream society (Tausch et al. 2011), opening for media representations of environmental activists as troublemakers or even terrorists.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Our findings suggest that radical beliefs in the form of anti-speciesism do indeed lead to support for radical protest forms, but that this support also draws on a broader and more widely shared set of pro-environmental beliefs, as shown by the even stronger association with a broad range of pro-environmental behaviours, and with a positive belief in the political impact of activism, contrary to narratives which associate radical protest with cynicism and disengagement. We recommend future studies with mixed methods design to aim to understand whether people’s support or willingness to engage in disruptive protest forms grows after having being involved in public pro-environmental behavior and activism, and a closer focus on the role of participants in different forms of pro-environmental behaviours personality traits and on social roles in environmental movements.

References

- Adams, A., Shriver, T., Longest, L.(2020) ‘Symbolizing Destruction: Environmental Activism, Moral Shocks, and the Coal Industry’ Nature and Culture, Vol.15 (3), p.249-271.

- Amburgey J. and Thoman D. (2012) ‘Dimensionality of the New Ecological Paradigm: Issues of Factor Structure and Measurement’ Environment and Behavior 44(2) 235–256 Barkela, B., López, T. and Klöckner C. (2022) ‘A License to Disrupt? Artistic Activism in Environmental Public Dissent and Protest’ in C. A. Klöckner, E. Löfström, Disruptive Environmental Communication, Psychology and Our Planet, 57-73.

- Choudhary, V., Sharma, B. (2022) ‘Study of Nature Connectedness and Psychological Well-being among Adults’ Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, Vol.13 (2), p.146-149.

- Çiğdemli A. and Avci C. (2023) ‘Examining the Relationships between Tourists’ Connectedness to Nature and Landscape Preferences’ Journal of Tourism, Sustainability and Well-being, Vol.11 (4), p.218-238.

- Dunlap, R. E., & Van Liere, K. D. (1978). The “new environmental paradigm”: A proposed measuring instrument and preliminary results. Journal of Environmental Education, 9, 10–19.

- Dunlap, Riley E. ; Van Liere, Kent D. ; Mertig, Angela G. ; Jones, Robert Emmet (2000) ‘Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale’ Journal of social issues,, Vol.56 (3), p.425-442.

- Edgell, M. C. R., & Nowell, D. E. (1989). The new environmental paradigm scale: Wildlife and environmental beliefs in British Columbia. Society and Natural Resources, 2, 285–296.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Communication, Directorate-General for Environment, TNS Opinion & Social, (2014) Attitudes of European citizens towards the environment : report. Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779/25662.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Environment, (2024) Attitudes of Europeans towards the environment : Eurobarometer report. European Commission. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779/07854.

- Frantz, C. Mayer, F. (2014) ‘The importance of connectedness to nature in assessing environmetal programs’ Studies in educational evaluation, Vol.41, p.85-89.

- Foxe J. Dolšak N. and Prakash A. (2024) ‘Varieties of climate activism: assessing public support for mainstream and unorthodox climate action in the United Kingdom’ Environ. Res. Commun. 6: 111006.

- Furman, A. (1998). A note on environmental concern in a developing country: Results from an Istanbul survey. Environment and Behavior, 30, 520–534.

- Gawrych, M. (2022) ‘Internet addiction in light of social connectedness and connectedness to nature.’ European Psychiatry, 2022-06, Vol.65 (S1), p.S596-S596.

- Gooch, G. D. (1995). Environmental beliefs and attitudes in Sweden and the Baltic states. Environment and Behavior, 27, 513–539.

- Gordon, O. (2024) ‘Do socially disruptive climate protests actually work?’ Energy Monitor https://www.energymonitor.ai/policy/net-zero-policy/do-socially-disruptive-climate-protests-actually-work/ posted 30 January 2024, accessed 15 April 2025.

- Hirsch-Hoefler, S., & Mudde, C. (2014). “Ecoterrorism”: Terrorist threat or political ploy. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 37(7), 586–603. [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2021). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 28.0) [Computer software].

- Jansma, A., Kruglanski, A. van den Bos, K., de Graaf, B., Riordan, O. (2025) Protecting the Earth Radically: Perceiving police injustice activates climate protesters’ need for significance Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol.103, p.102578.

- Kenward, B. and Brick, C. (2024) ‘Large-Scale Disruptive Activism Strengthened Environmental Attitudes in the United Kingdom’ Global Environmental Psychology, Vol.2 Article e11079.

- Klas, A., Zinkiewicz, L., Zhou, J., & Clarke, E. J. (2019). “Not all environmentalists are like that…”: unpacking the negative and positive beliefs and perceptions of environmentalists. Environmental Communication, 13(7), 879-893.

- Landmann, H., Rohmann, A. (2020) ‘Being moved by protest: Collective efficacy beliefs and injustice appraisals enhance collective action intentions for forest protection via positive and negative emotions’ Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol.71, p.101491.

- Lovati, C. ; Manzi, F., Di Dio, C., Massaro, D., Gilli, G., Marchetti, A. (2023) ‘Feeling connected to nature: validation of the connectedness to nature scale in the Italian context’ Frontiers in Psychology, Vol.14 (10), p.1242699.

- Matejova M., Merkley E. (2022) ‘Protest Under Uncertainty: Evidence from a Survey Experiment’, Environmental Communication, 16:2, 163-178.

- Martiskainen, M., Axon, S., Sovacool, B., Sareen, S. Furszyfer Del Rio, D., Axon, K. (2020) ‘Contextualizing climate justice activism: Knowledge, emotions, motivations, and actions among climate strikers in six cities’ Global environmental change, Vol.65, p.102180.

- Mayer, F. and Frantz, C. (2004) ‘The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature. J. Environ. Psychol., 24, 503–515.

- Meijers, M., Wonneberger, A., Azrout, R., Torfadóttir, R,; Brick, C. (2023) ‘Introducing and testing the personal-collective-governmental efficacy typology: How personal, collective, and governmental efficacy subtypes are associated with differential environmental actions’ Journal of Environmental Psychology Vol.85, p.101915.

- Morgan, A., Cubitt, T., Voce, A., Voce, I. (2024) ‘An experimental study of support for protest causes and tactics and the influence of conspiratorial beliefs’ Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice, (702): 1-23.

- Munro L. (2022) ‘Animal Rights and Anti-Speciesism’ in Grasso S. and Giugni M. eds. The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Movements 199-214.

- Ostarek, M. Simpson B. Rogers C. Ozden J.(2024) ‘Radical climate protests linked to increases in public support for moderate organizations’ Nature Sustainability 7:1626–1632.

- Pierce, J. C., Lovrich, Jr., N. P., Tsurutani, T., & Takematsu, A. (1987). Environmental belief systems among Japanese and American elites and publics. Political Behavior, 9, 139–159.

- Pierce, J. C., Steger, M. E., Steel, B. S., & Lovrich, N. P. (1992). Citizens, political communication and interest groups: Environmental organizations in Canada and the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Simpson, B. Willer R. and Feinberg M. (2022) ‘Radical flanks of social movements can increase support for moderate factions’ PNAS Nexus, 1, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Splash, Clive L (2006) ‘Non-Economic Motivation for Contingent Values: Rights and Attitudinal Beliefs in the Willingness to Pay for Environmental Improvements Land economics’, Vol.82 (4), p.602-622.

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., & Guagnano, G. A. (1995). The new ecological paradigm in social-psychological context. Environment and Behavior, 27, 723–743.

- Tausch, N., Becker, J. C., Spears, R., Christ, O., Saab, R., Singh, P., et al. (2011). ‘Explaining radical group behavior: Developing emotion and efficacy routes to normative and nonnormative collective action.’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 129–148.

- Turina I. (2018) ‘Pride and Burden: The Quest for Consistency in the Anti-Speciesist Movement’, Animals and Society 26: 239-258.

- Widegren, O. (1998). The new environmental paradigm and personal norms. Environment and Behavior, 30, 75–100.

Table 1.

Descriptive results of the study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive results of the study variables.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix of the study variables.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix of the study variables.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression results for support for radical protest forms.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression results for support for radical protest forms.

Table 4.

Integration of perceived governmental efficacy as a predictor and moderator.

Table 4.

Integration of perceived governmental efficacy as a predictor and moderator.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).