Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

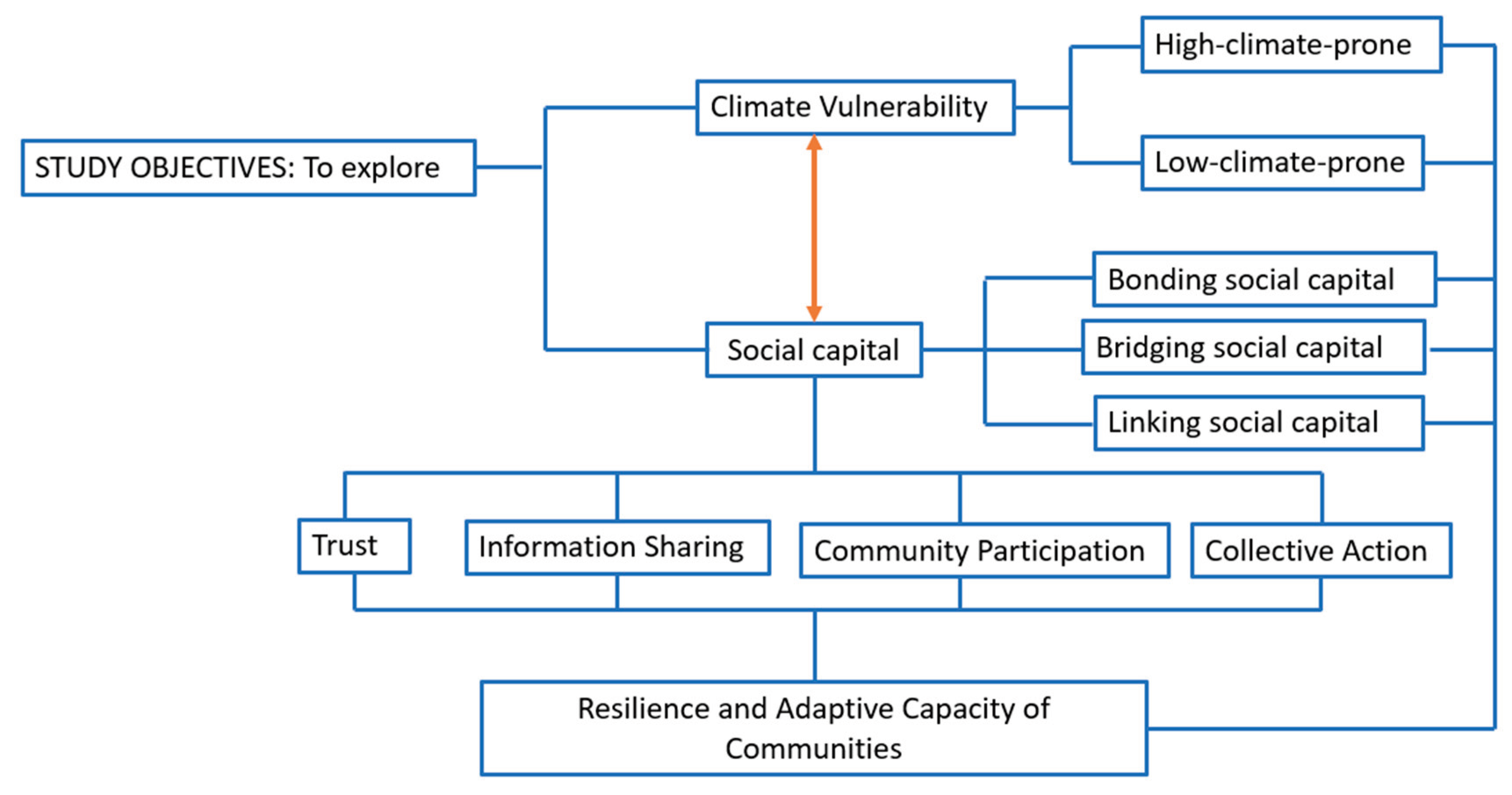

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Climate Vulnerability: High Climate-Prone Regions vs. Low Climate-Prone Regions

| Characteristics | High climate-prone regions | Low climate-prone regions |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency and Severity of Extreme events | High climate-prone regions experience a higher frequency and greater severity of extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, cyclones, floods, and droughts. | Low climate-prone regions experience fewer extreme weather events with lower intensity, making them less vulnerable to catastrophic disasters. |

| Sea-level Rise | Coastal areas in high climate-prone regions are more susceptible to sea-level rise, leading to increased coastal erosion risks and inundation. | These regions usually have stable sea levels, reducing the risk of coastal erosion and inundation. |

| Temperature Fluctuations | These regions often face extreme temperature variations, including heat waves and cold snaps, impacting ecosystems, agriculture, and human health. | Temperature variations are generally milder. |

| Precipitation Variability | High climate-prone regions may witness erratic rainfall patterns, including prolonged periods of rainfall or extended droughts, that significantly disrupt water resources and agriculture. | Rainfall patterns are usually predictable. |

| Biodiversity Impact | Climate change can disrupt ecosystems in high climate-prone areas, leading to shifts in species distributions and endangering biodiversity. | Ecosystems in low climate-prone areas are less likely to face drastic shifts in species distribution. |

| Human Displacement | There are higher levels of climate-induced human displacement, including migration, due to environmental factors. | Climate-induced displacement is less common in low climate-prone regions. |

| Infrastructure Vulnerability | Infrastructure such as buildings and transportation networks, as well as educational and health infrastructure, are more susceptible to damage from extreme weather events, leading to increased disruptions and repair costs. | Infrastructure usually withstands the occasional extreme weather event. |

| Economic Impact | The economy of high climate-prone regions is often more vulnerable to climate-related losses in agriculture, tourism and other sectors. | The economy of low climate-prone regions is generally more stable and less susceptible to climate-related losses. |

| Health Risks | Climate-related health risks, such as the spread of vector-borne diseases, skin infections, allergies, heat-related illnesses, etc., are more prevalent. | Climate-related health risks like the spread of vector-borne diseases, skin infections, allergies, heat-related illnesses, etc., are less prevalent. |

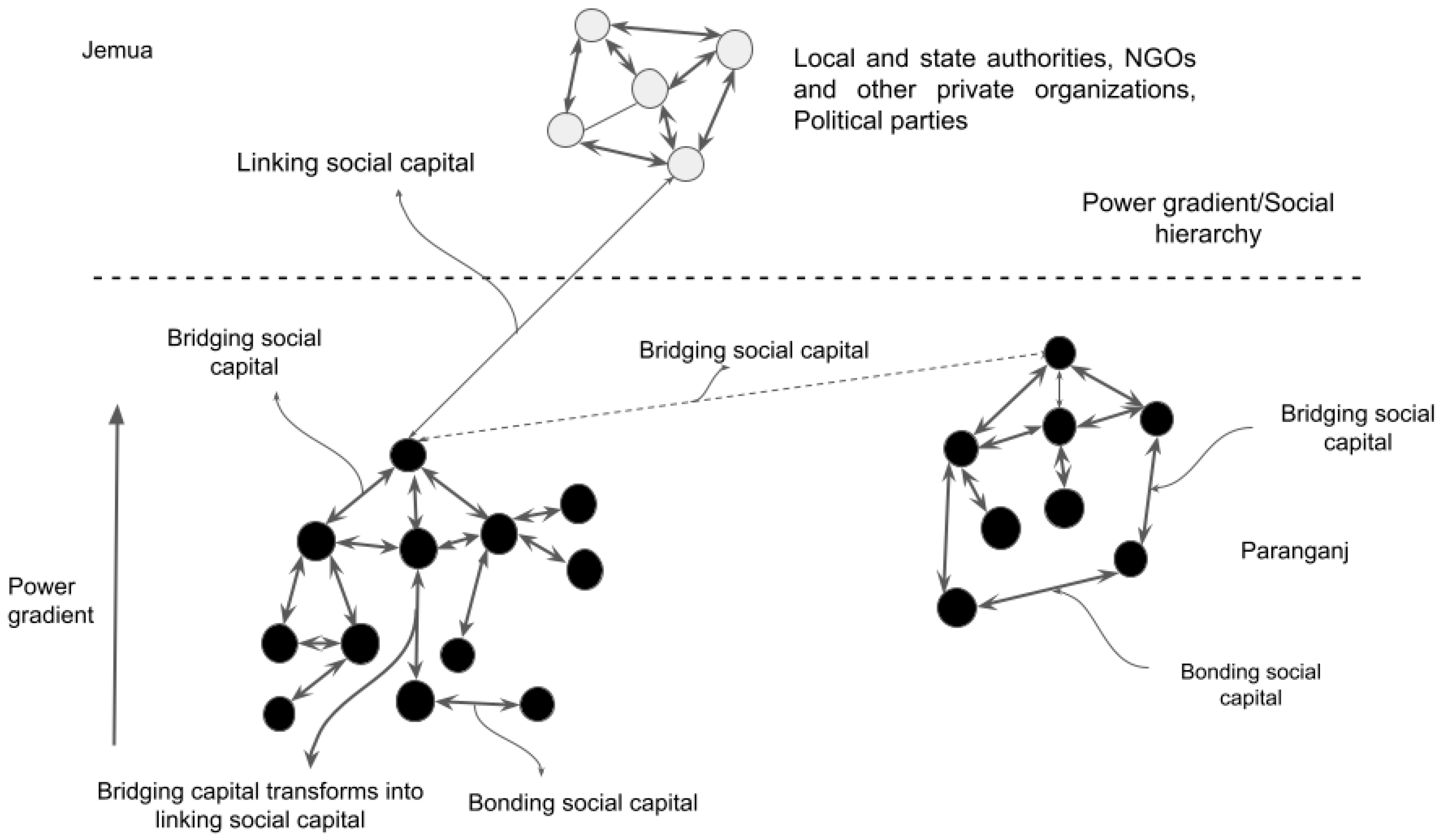

2.2. Social Capital

2.3. Vulnerability, Resilience, and Social Capital

3. Methodology

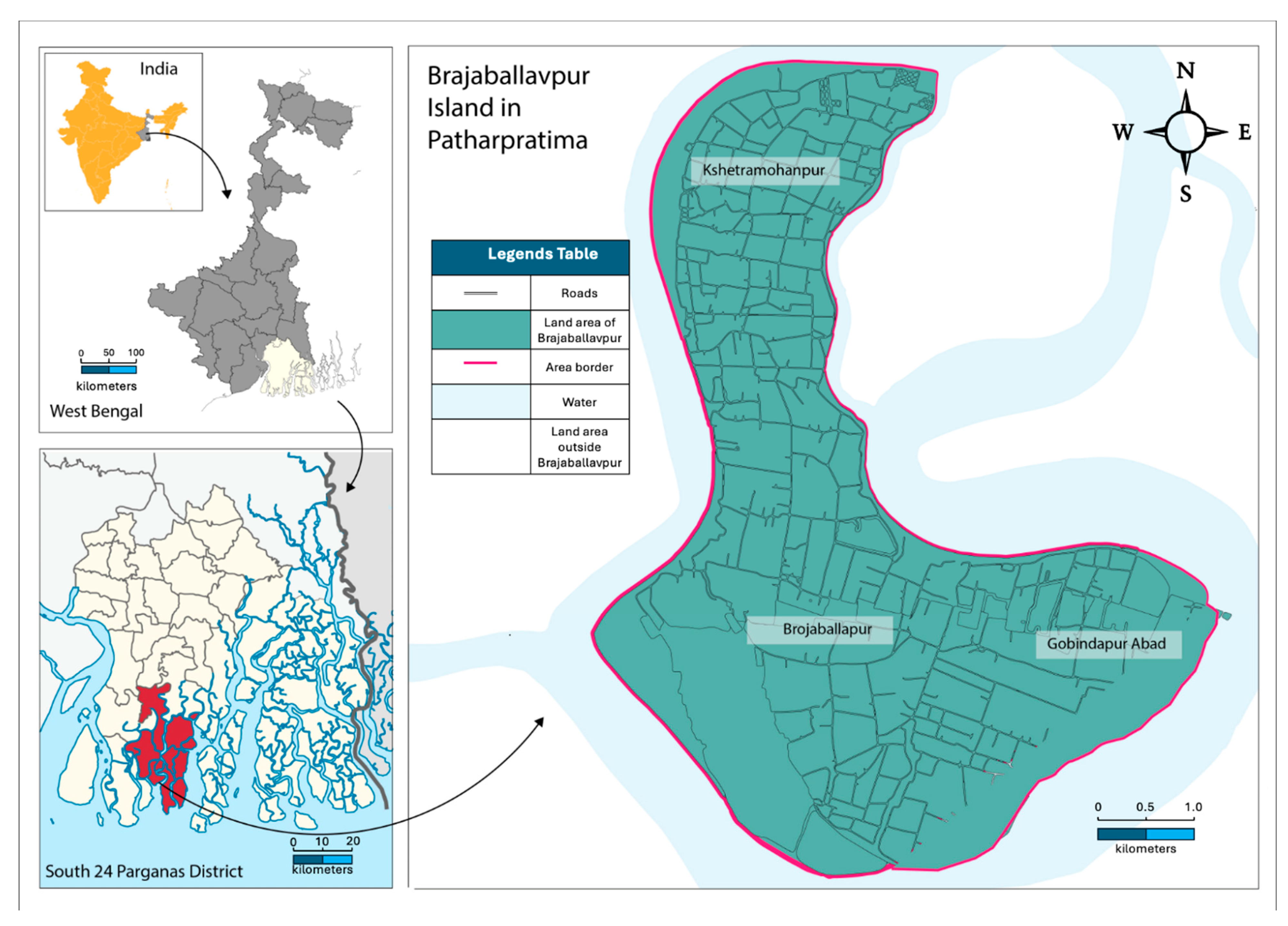

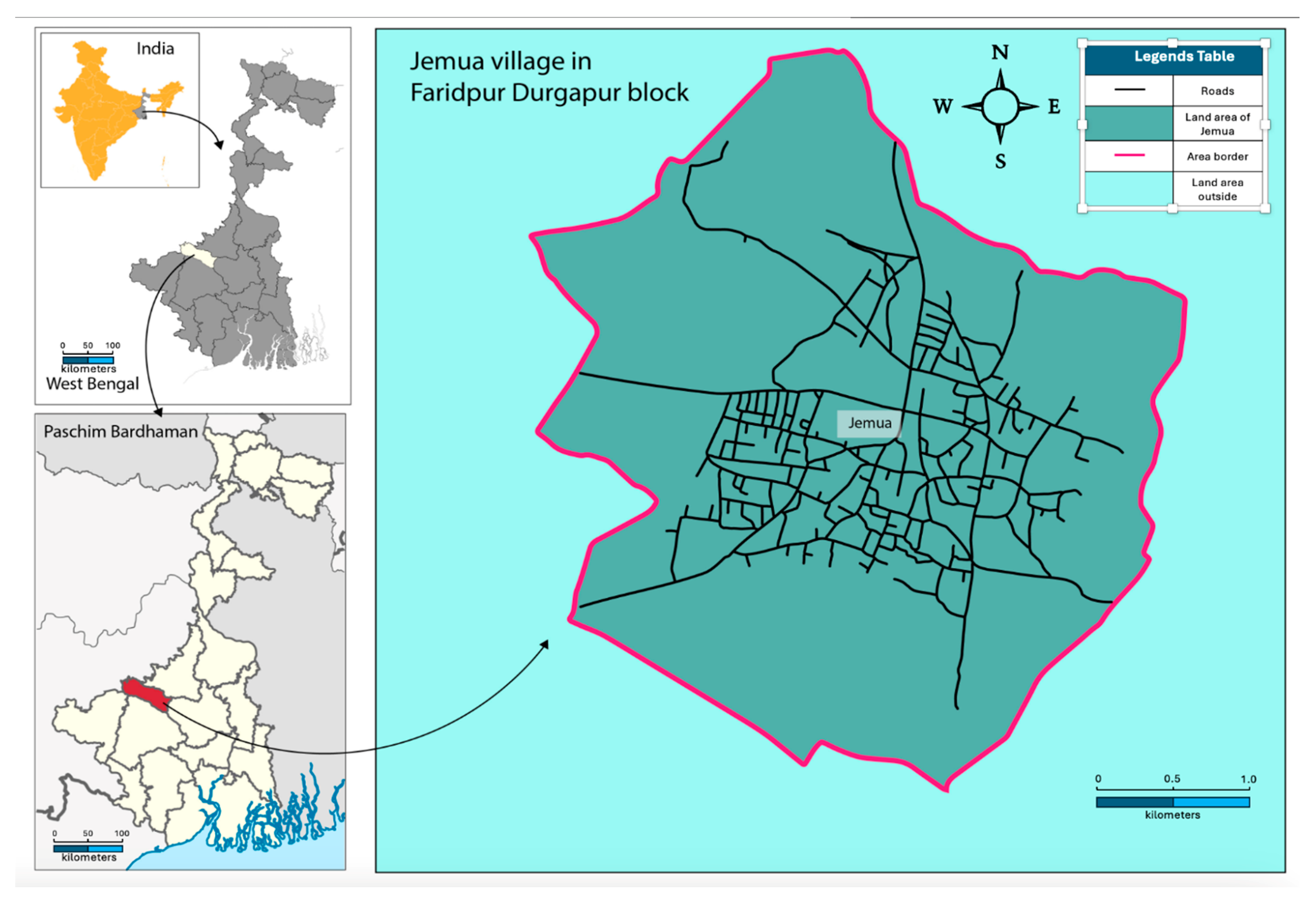

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection Methods

- Ethnographic Field Surveys: The ethnographic surveys for this study were designed to provide an in-depth, immersive understanding of how social capital functions in communities with varying levels of climate vulnerability using integrated participant observation, and informal conversations, to capture the nuances of everyday social interactions, governance structures, and community resilience strategies. This was a pre-requisite to the data collection process as it provided us with a direction of inquiry for the subsequent phases of data collection, like FGDs and KIIs.

- Participatory Rural Appraisals (PRAs): PRAs were conducted to map community resources, social networks, and climate adaptation strategies through interactive and visual methods. The key components of PRAs included:

- Social and Resource Mapping: Community members collectively identified key social institutions, climate risks, and available resources, helping to visualize local power structures and access to aid.

- Transect Walks: Researchers and participants walked through different parts of the village to observe infrastructure, environmental conditions, and socio-economic divisions. These walks facilitated spatial analysis of social capital distribution.

- Timeline: Community elders and long-term residents described historical climate patterns, major disasters, and how social ties evolved in response to climate threats.

- Focus Group Discussions (FGDs): Using a semi-structured questionnaire FGDs were organized to capture the perspectives of various socio-economic groups within each community. In Brajaballavpur, these discussions focused on understanding community responses to climate catastrophes, aspects of collective action, recovery, and rehabilitation processes, while in Jemua, they explored broader issues of involvement of community members in decision-making processes, development, and governance.

- Key Informant Interviews (KIIs): Interviews were conducted with local leaders, panchayat workers, and village elders to gather insights on climate vulnerabilities, socio-political dynamics, and coping strategies in each area. In Brajaballavpur, these interviews were essential for understanding the challenges posed by the isolation of the island and the role of mutual reliance, collective action, and access to external aid, whereas, in Jemua, they highlighted how political affiliation and local governance influenced resource access.

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

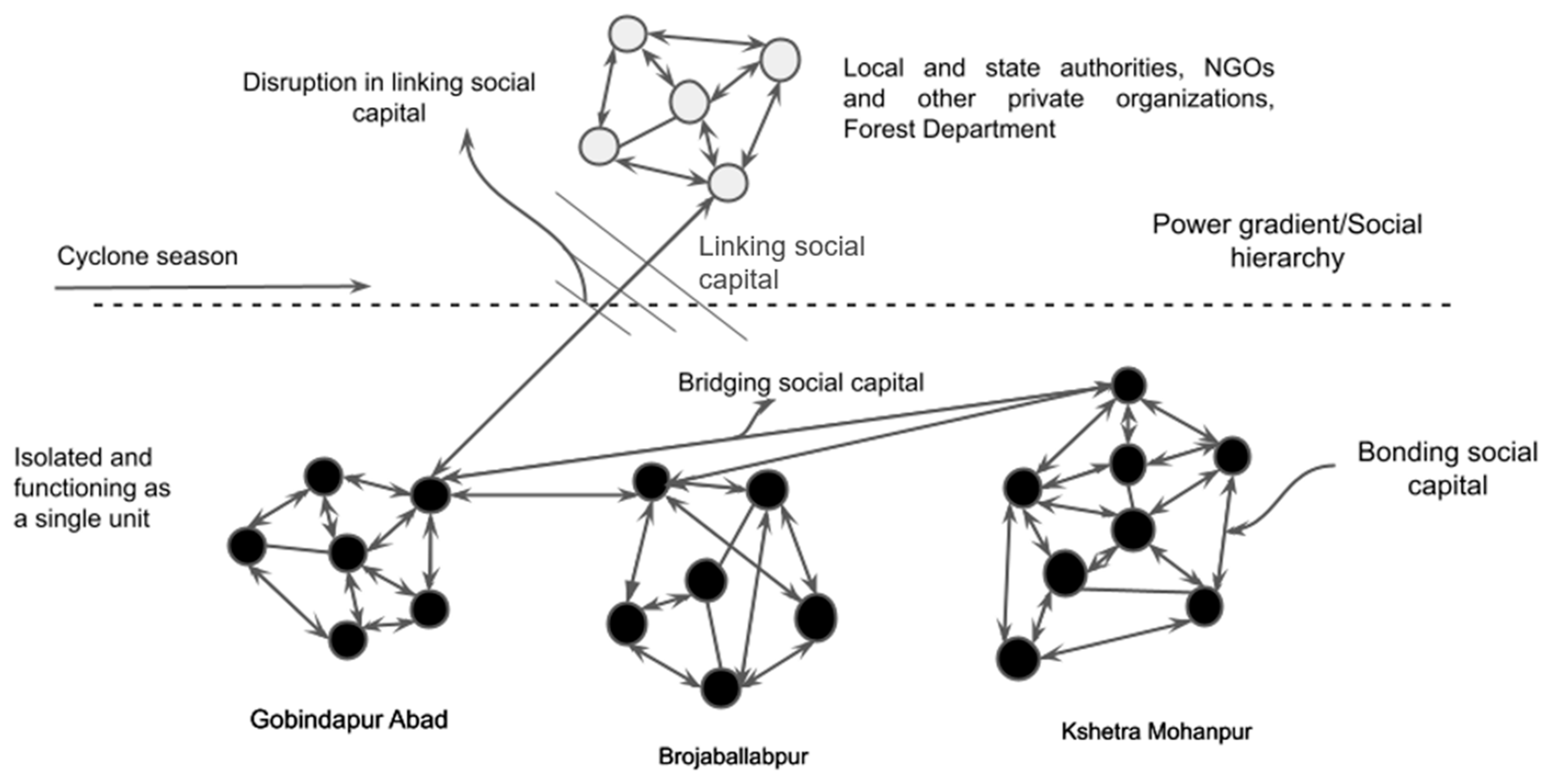

4.1. The Indian Sundarbans

- “After the cyclone, the water takes time to recede. During this time, there was no outside help for days,” one resident shared during the Focus Group Discussion. “We had to form our own rescue teams, and we all did what we could. People brought food, cleared debris, and checked on our neighbors—it was all hands on deck”.

- “Sure, we have our differences, but when the cyclone strikes, none of those matters. You know it is the people of the village who will pull you out of trouble, not some outsider. After all we’ve been through, those bonds don’t just disappear”, pointed out another resident when asked about whether ideological differences impact community response.

- “Some parts of the village are more affected than others during the cyclones. Just because I am not from that neighborhood does not mean that I will not help in the aftermath. In all these years, we have learned that no one else will reach us as quickly as our own people. That is why we find the strength to face the storms every year. We know that if all of us help one another, we can survive,” mentioned another resident.

- “Many people came back to the village during COVID. For many households, it meant that they had no livelihood. This resulted in any able-bodied members of the household going to the forest and the sea for livelihood. It is a high-risk, high-profit venture. If you are lucky, you can feed your family. If you are not, you do not come back. Many who go to the forest know this very well, yet they choose to go because they do not hae any options left.” Village official (Brajaballavpur), KII.

- “When there is an unfortunate accident, it’s not just that family who mourns,” says a Respondent during the FGD, “We all grieve together. When we get to know that someone from the village has been taken, we try to conduct a rescue or at least retrieve the body. Most of the time, it’s the latter. That, too, takes days. Sometimes there is no body or not much left of the body to bring back. Then there is the matter of compensation. It is a lengthy process, and most of the time, the family is not aware of the process. If we do not help them, they will starve. How can we let that happen to our own people?”

- “We are all Bonbibi’s children. In this place, she is the mother that protects and blesses us all. Her kindness keeps us alive and provides us with the means to sustain ourselves. What mother would like to see her children fighting amongst themselves?” points out a village elder when discussing the importance of Bonbibi in village dynamics in a KII.

- “Those who can, they have migrated already. Those who remain behind either do not have the means or simply do not want to migrate. This land provides us with everything we need. We are connected to it. Whatever we have is our own. Here, if we need something, we can ask our neighbor. For weddings and funerals, all of us are there for one another. Can we find this in the big cities?” Mentions a participant from the Focus Group Discussion.

- “I do not want to leave because here, everyone knows me. If I have to go to the hospital or the market, I always find someone or the other who would offer a ride. Life in the big cities is very hard because you do not know anyone, and no one knows you.”, points out another participant.

- “Relief comes to our village much later. And it always comes through channels. Sometimes, if you are not aware or do not know the right people, you may not receive any relief material.” Points out a participant in the Focus Group Discussion.

- “Permanent roads and infrastructure are essential if we want to rebuild after a cyclone. Any temporary structures get washed away. We have been asking for a proper road in the neighborhood for a very long time, but nothing has happened yet. Our nearest healthcare facility is in Patharpratima. We have to depend on the availability of the ferry and the tides of the river to consult a doctor. Imagine the situation if someone gets seriously ill or injured during the cyclone season. We do not have anything to do then.” Adds another participant.

- “After a cyclone, most of our things are lost or have been washed away. We usually survive on very little food and water. Thus, relief becomes very important for us to sustain and, later on, rebuild our lives. Everyone in the village needs it in some form or the other, and usually, the relief that we get is not enough for everybody. We have to assess who needs it more than the others. However, if someone gets some of the relief material and another person does not, they think that it’s deliberate on our part. It is a tough job sometimes, but someone has to do it.” Responds a member of the Panchayat in a KII.

4.2. Paschim Bardhaman

- “Mostly, we talk to our immediate neighbors and the households opposite to ours. Usually, we are so occupied throughout the day that we barely get time to chat. Sometimes in the evenings, we might get together, but it does not happen every day.” Mentions a respondent from the higher-caste paras when asked about their day-to-day interaction with their neighbors during an FGD.

- “We do not really ask our neighbors for anything unless, of course, it’s a serious problem. It does not look nice, I think. However, sometimes, if I make something in surplus, I share some of it with my neighbors, and they do the same. That is what keeps us together, I think.” Mentions another respondent from the higher caste paras when asked about their dependency on their neighbors in an FGD.

- “We rely on our neighbors for everything. Sometimes even for basic things like salt.” Mentions a respondent from the lower-caste para.

- As one community member expressed, “If you know someone in the party, doors open faster. Getting help with school admissions or even a job depends on who you know.”

- It’s not fair,” said one resident from a lower-caste para. “Those without connections don’t get the same help, even when they need it more. You have to run behind the officials with your papers, and even then, there is no saying how much time it might take for things to be processed. However, for those with connections, you just need a phone call, and your request will be taken care of.”

- “We have been requesting for a tube well in our part of the village for months now. We are always being sent back saying that when there would be funds available, our requests would be given priority, but we are still waiting.” Expresses another resident.

- “Our households are eligible for construction of household latrines under the state government scheme for sanitation. It has been a while since I placed my application. I have seen many households in the higher-caste paras get their latrine despite them having the means to construct their own household latrine. However, in my case, they always respond that my turn has not come yet and that I need to wait even longer.” Says one resident from a lower-caste para in a KII.

- “This kind of government work takes time.” Responds a Panchayat official in a KII. “Just because someone has placed an application does not mean that they will immediately get a household latrine. We try to allot the construction based on a lot of assessment which requires quite a lot of planning.”

- “We are mostly not invited to the festivities or celebrations that happen in the higher-caste paras. Some people from our para might be invited, but most are not.” Says one resident from the lower-caste paras in an FGD.

- “We do not know people from the higher-caste paras that well to invite them to our celebrations.” Says another resident.

- ‘Our connections to the party leadership have facilitated many development initiatives in the village, and we are very grateful. We always prioritize the needs of the village in our discussions with the party leadership.’ Says a Panchayat official in a KII about development initiatives and the role of political parties and external agencies.

- “Some people from our para are Panchayat Members, but that is only for show. Most of the time, they are not called for meetings, and their opinions are not taken into consideration during the decision-making processes.” Says one respondent from the lower-caste paras in a KII.

- “Our problems and concerns are only important during the elections. After the elections, things go back to being the same.”, says another respondent.

- “It is a matter of great pride that we have members from different communities and genders in our Panchayat. We always strive to make the decisions collectively, and everyone’s ideas and thoughts are given equal importance.” Says a village official belonging to a higher-caste para when asked about inclusivity and participation in the decision-making processes of the village in a KII.

5. Conclusion and Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflict of Interest

References

- Islam, M. S.; Lim, S. H. When “Nature” Strikes: A Sociology of Climate Change and Disaster Vulnerabilities in Asia. Nature and culture 2015, 10 (1), 57–80. [CrossRef]

- Kais, S. M.; Islam, M. S. Community Capitals as Community Resilience to Climate Change: Conceptual Connections. International journal of environmental research and public health 2016, 13 (12), 1211-. [CrossRef]

- Dynes, R. (2002). The importance of social capital in Disaster Response. Disaster Research Center Paper.

- Bergstrand, K.; Mayer, B.; Brumback, B.; Zhang, Y. Assessing the Relationship Between Social Vulnerability and Community Resilience to Hazards. Social indicators research 2015, 122 (2), 391–409. [CrossRef]

- Kasperson, J. X.; Kasperson, R. E.; Turner, B. L.; Hsieh, W.; Schiller, A. Vulnerability to Global Environmental Change. In The Social Contours of Risk; Routledge, 2005; Vol. II, pp 245–285. [CrossRef]

- Hanson, C.; Parry, M.; Canziani, O.; Palutikof, J.; van der Linden, P. Climate Change 2007; Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, 2007.

- Cutter, S. L.; Ash, K. D.; Emrich, C. T. The Geographies of Community Disaster Resilience. Global environmental change 2014, 29, 65–77. [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S. L.; Burton, C. G.; Emrich, C. T. Disaster Resilience Indicators for Benchmarking Baseline Conditions. Journal of homeland security and emergency management 2010, 7 (1), 44–45. [CrossRef]

- Wickes, R.; Zahnow, R.; Taylor, M.; Piquero, A. R. Neighborhood Structure, Social Capital, and Community Resilience: Longitudinal Evidence from the 2011 Brisbane Flood Disaster. Social science quarterly 2015, 96 (2), 330–353. [CrossRef]

- Adger, W. N.; Voss, M. Social Capital, Collective Action, and Adaptation to Climate Change. In Der Klimawandel; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, 2010; pp 327–345. [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D. P. Power of People: Social Capital’s Role in Recovery from the 1995 Kobe Earthquake. Natural hazards (Dordrecht) 2011, 56 (3), 595–611. [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D. P. Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery. In Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2012, pp. xii, 232; 2012; pp xii–xii.

- Aldrich, D. P.; Meyer, M. A. Social Capital and Community Resilience. The American behavioral scientist (Beverly Hills) 2015, 59 (2), 254–269. [CrossRef]

- Hanifan, L. J. The Rural School Community Center. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 1916, 67 (1), 130–138. [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. Journal of Economic Sociology 1986, 3 (5), 241–258.

- Coleman, J. S. Foundations of Social Theory. In Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard U Press, 1990. xvi+993 pp; 1990; pp xvi–xvi.

- Putnam, R. D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. In CSCW 2000 : computer supported cooperative work : ACM 2000 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, December 2-6, 2000, Philadelphia, PA, USA; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp 357–357. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.; Hardy, R. D.; Lazrus, H.; Mendez, M.; Orlove, B.; Rivera-Collazo, I.; Roberts, J. T.; Rockman, M.; Warner, B. P.; Winthrop, R. Explaining Differential Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Social Science Review. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Climate change 2019, 10 (2), e565-. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Ruane, A. C. CLIMATE CHANGE 2023 Synthesis Report Summary for Policymakers, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Goddard Space Flight Center, 2024.

- Buhaug, H.; von Uexkull, N.; Tomich, T.; Gadgil, A. Vicious Circles: Violence, Vulnerability, and Climate Change. Annual review of environment and resources 2021, 46 (1), 545–568. [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.; Angeon, V.; Ainouche, A. The Pentagon of Vulnerability and Resilience: A Methodological Proposal in Development Economics by Using Graph Theory. Economic modelling 2014, 42, 445–453. [CrossRef]

- McGill, R. Urban Resilience: An Urban Management Perspective. Journal of urban management 2020, 9 (3), 372–381. [CrossRef]

- Holling, C. S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems; International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis: Laxenburg, Austria, 1973.

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J. P.; Stults, M. Defining Urban Resilience: A Review. Landscape and urban planning 2016, 147, 38–49. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, C. Community Climate Resilience in Cambodia. Environmental research 2020, 186, 109512–109512. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, P. M.; Dissart, J.-C. Reframing Vulnerability and Resilience to Climate Change through the Lens of Capability Generation. Ecological economics 2022, 201, 107556-. [CrossRef]

- Kelman, I.; Gaillard, J. C.; Lewis, J.; Mercer, J. Learning from the History of Disaster Vulnerability and Resilience Research and Practice for Climate Change. Natural hazards (Dordrecht) 2016, 82 (Suppl 1), 129–143. [CrossRef]

- Reghezza-Zitt, M.; Rufat, S. Disentangling the Range of Responses to Threats, Hazards and Disasters. Vulnerability, Resilience and Adaptation in Question. Cybergeo 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-González, C.; Ávila-Foucat, V. S.; Ortiz-Lozano, L.; Moreno-Casasola, P.; Granados-Barba, A. Analytical Framework for Assessing the Social-Ecological System Trajectory Considering the Resilience-Vulnerability Dynamic Interaction in the Context of Disasters. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2021, 59, 102232-. [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.; MacGillivray, B. H.; Gong, Y.; Hales, T. C. The Application of Frameworks for Measuring Social Vulnerability and Resilience to Geophysical Hazards within Developing Countries: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. The Science of the total environment 2020, 711, 134486–134486. [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I.; Wisner, B.; Cline-Cole. “At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters” (By Piers Blaikie, Terry Cannon, Ian Davis and Ben Wisner) (Book Review). Disasters 1997, 21 (2), 185–185.

- Ziervogel, G.; Bharwani, S.; Downing, T. E. Adapting to Climate Variability: Pumpkins, People and Policy. Natural resources forum 2006, 30 (4), 294–305. [CrossRef]

- Mertz, O.; Halsnæs, K.; Olesen, J. E.; Rasmussen, K. Adaptation to Climate Change in Developing Countries. Environmental management (New York) 2009, 43 (5), 743–752. [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S. L.; Finch, C. Temporal and Spatial Changes in Social Vulnerability to Natural Hazards. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS 2008, 105 (7), 2301–2306. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; O’Neill, S. Maladaptation. Global environmental change 2010, 20 (2), 211–213. [CrossRef]

- Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Summary for Policymakers: A Report of Working Groups I and II of the IPCC; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, 2012.

- Goss, M.; Swain, D. L.; Abatzoglou, J. T.; Sarhadi, A.; Kolden, C. A.; Williams, A. P.; Diffenbaugh, N. S. Climate Change Is Increasing the Likelihood of Extreme Autumn Wildfire Conditions across California. Environmental research letters 2020, 15 (9), 94016-. [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Limiting Climate Change Requires Research on Climate Action. Nature climate change 2018, 8 (9), 759–761. [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Andersson, E.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Olsson, P.; Gaffney, O.; Takeuchi, K.; Folke, C. Sustainability and Resilience for Transformation in the Urban Century. Nature sustainability 2019, 2 (4), 267–273. [CrossRef]

- Urquiza, A.; Amigo, C.; Billi, M.; Calvo, R.; Gallardo, L.; Neira, C. I.; Rojas, M. An Integrated Framework to Streamline Resilience in the Context of Urban Climate Risk Assessment. Earth’s Future 2021, 9 (9). [CrossRef]

- Umamaheswari, T.; Sugumar, G.; Krishnan, P.; Ananthan, P. S.; Anand, A.; Jeevamani, J. J. J.; Mahendra, R. S.; Amali Infantina, J.; Srinivasa Rao, C. Vulnerability Assessment of Coastal Fishing Communities for Building Resilience and Adaptation: Evidences from Tamil Nadu, India. Environmental science & policy 2021, 123, 114–130. [CrossRef]

- Maclean, K.; Cuthill, M.; Ross, H. Six Attributes of Social Resilience. Journal of environmental planning and management 2014, 57 (1), 144–156. [CrossRef]

- Baycan, T.; Öner, Ö. The Dark Side of Social Capital: A Contextual Perspective. The Annals of regional science 2023, 70 (3), 779–798. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. C. The Impact of Social Capital and Social Networks on Tourism Technology Adoption for Destination Marketing and Promotion: A Case of Convention and Visitors Bureaus, ProQuest LLC, 2011.

- Magis, K. Community Resilience: An Indicator of Social Sustainability. Society & natural resources 2010, 23 (5), 401–416. [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited. Sociological theory 1983, 1, 201–233. [CrossRef]

- Kyne, D.; Aldrich, D. P. Capturing Bonding, Bridging, and Linking Social Capital through Publicly Available Data. Risk, hazards & crisis in public policy 2020, 11 (1), 61–86. [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; Van Horn, R. L.; Pfefferbaum, R. L. A Conceptual Framework to Enhance Community Resilience Using Social Capital. Clinical social work journal 2017, 45 (2), 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Shoji, M.; Takafuji, Y.; Harada, T. Formal Education and Disaster Response of Children: Evidence from Coastal Villages in Indonesia. Natural hazards (Dordrecht) 2020, 103 (2), 2183–2205. [CrossRef]

- Smiley, K. T.; Howell, J.; Elliott, J. R. Disasters, Local Organizations, and Poverty in the USA, 1998 to 2015. Population and environment 2018, 40 (2), 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Adger, W. N.; Klein, R. J. T.; Huq, S.; Smith, J. B. Social Aspects of Adaptive Capacity. In Climate Change, Adaptive Capacity And Development; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2003; pp 29–49. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R. L.; Maurer, K. Bonding, Bridging and Linking: How Social Capital Operated in New Orleans Following Hurricane Katrina. The British journal of social work 2010, 40 (6), 1777–1793. [CrossRef]

- Metaxa-Kakavouli, D.; Maas, P.; Aldrich, D. P. How Social Ties Influence Hurricane Evacuation Behavior. Proceedings of the ACM on human-computer interaction 2018, 2 (CSCW), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Pelling, M.; High, C. Understanding Adaptation: What Can Social Capital Offer Assessments of Adaptive Capacity? Global environmental change 2005, 15 (4), 308–319. [CrossRef]

- Petzold, J.; Ratter, B. M. Climate Change Adaptation under a Social Capital Approach – An Analytical Framework for Small Islands. Ocean & coastal management 2015, 112, 36–43. [CrossRef]

- Basu, J. Amphan havoc worst in world this year: UK report. Telegraphindia.com. https://www.telegraphindia.com/west-bengal/calcutta/amphan-havoc-worst-in-world-this-year-uk-report/cid/1801824.

- Mitra, A.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Dube, A.; Schmidt, A. C. K.; Banerjee, K. Observed Changes in Water Mass Properties in the Indian Sundarbans (Northwestern Bay of Bengal) during 1980–2007. Current science (Bangalore) 2009, 97 (10), 1445–1452.

- Dubey, S. K., Chand, B. K., Trivedi, R. K., Mandal, B., & Rout, S. K. Evaluation on the prevailing aquaculture practices in the Indian Sundarban delta: an insight analysis. Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment 2016, 14(2), 133-141.

- Sarkar, C.; Hazarik, Silpi Sikha; Singh, B. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown Period on Man and Wildlife Conflict in India. Ssrn.com. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3712831.

- Pramanik, M.; Szabo, S.; Pal, I.; Udmale, P.; O’Connor, J.; Sanyal, M.; Roy, S.; Sebesvari, Z. Twin Disasters: Tracking COVID-19 and Cyclone Amphan’s Impacts on SDGs in the Indian Sundarbans. Environment : science and policy for sustainable development 2021, 63 (4), 20–30. [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, S.; Routray, J. K. Social Capital for Disaster Risk Reduction and Management with Empirical Evidences from Sundarbans of India. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2016, 19, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Jalais, A.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Of pandemics and storms in the Sundarbans. American Ethnologist Website 2020.

| Characteristic | High Climate-Prone | Low Climate-Prone |

|---|---|---|

| Geography | Island | Land-locked |

| Settlement Pattern | Dispersed | Nucleated |

| Constitution | Paras are divided based on surnames but are not homogenous that way. | Paras are divided based on caste and are distinctly homogenous. |

| Experiences extreme weather events | Yes | No |

| Degree of trust and social cohesion among the community members across various socioeconomic groups | High | Low |

| Community Engagement and participation | High: Greater involvement of the local community in the decision-making process and disaster-preparedness initiatives. | Low: The Decision-making process is usually exclusive to a selected few. |

| Social memory and learning processes | Used for building resilience and adaptive capacity | Maintaining governance structures. |

| Collective Action | Extensive and more frequent collaboration between the members of the village. | Limited and less frequent collaboration between the members of the village. |

| Reliance on information networks | High reliance on information networks for climate forecasts, disaster warnings (during crisis times), educational/employment opportunities, healthcare access, other government schemes, and benefits during non-crisis times. | High reliance on information networks for educational/employment opportunities, healthcare access, other government schemes, and benefits during non-crisis times. |

| Bonding Social Capital | Bonding social capital is strong among the members of the entire village community due to the necessity for mutual support during and after climate-related catastrophes. | Bonding social capital is strong among members of the same socio-economic group or para. |

| Bridging Social Capital | Strong bridging capital among the three villages due to the necessity for knowledge and information exchange for disaster risk reduction passing of early warning information and also aids significantly in rescue and relief. | Low: Bridging capital with nearby villages is low and is only used for occasional information exchange. Mainly, it is used to secure votes during elections. Bridging capital exists between some members of different socioeconomic groups across the social hierarchy. |

| Linking social capital | Low; Disruption of connectivity results in disruption of linking social capital; Linking social capital is usually beneficial for long-term interventions like construction of roads and embankments, provision of electricity, water supply, health, and educational infrastructure, better disaster preparedness | High; Linking social capital is used for accessing government benefits and schemes, education and livelihood opportunities, healthcare access, etc. |

| Primary Role of Social Capital | Climate resilience | Development and Governance |

| Challenges | Strong bonding capital can result in mental distress when members are displaced/rehabilitated after a climate catastrophe. Linking social capital can result in unequal distribution and access to resources. | Bridging and linking social capital can result in inequities in resource access. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).