1. Introduction

In 1998, J. Lubchenco referred to the 21

st century as the "Century of the Environment," emphasizing the close connections between ecological systems and human health, the economy, social justice, and national security [

1]. Ten years later, C. Anderson, then Editor of

Wired magazine, predicted that the sheer volume of data would eliminate the need for theory and the scientific method [

2]. In the meantime, existential risks, which examine threats to human existence, have emerged as a rigorous and scientifically serious area of inquiry [

3,

4]. The need to better communicate scientific knowledge in conservation has become a common thread, with a call for new narrative strategies as communicative devices and conceptual tools [

5]. This contribution aims to explore the intersection of science-policy, existential risks, and big data to develop more optimistic storylines [

6], moving away from moralistic [

7], apocalyptic [

8], or utilitarian narratives [

9] that have proven ineffective [

5,

10]. Studying the evolution of UK citizens' environmental awareness in response to the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic serves as a timely and propitious example of this approach.

We are currently looking into whether people's experiences during the pandemic, such as fear, denial, and perceptions of environmentally driven risks, have been evolving after the epidemiological intensity of the disease and the containment measures put in place globally. We aim to understand how these experiences have affected people's awareness, understanding, and beliefs about the potential risks to humanity, especially when it is widely acknowledged in the existential risks literature that climate change and emergent diseases/biodiversity extinction are consistently ranked in the top 3 positions. As a baseline of the pandemic

per se, we will be referring to sources such as the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (

https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/), the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker ([

11];

https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/covid-19-government-response-tracker), earlier work on existential risks [

12,

13], as well as the Global Risks Reports of the World Economic Forum from 2010 to 2024 (

https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report- (year). The common denominator of the existential risks literature is that climate change and emergent diseases/biodiversity extinction are ranked systematically in the top 3 positions.

The paragraphs below provide a summary of the literature and arguments supporting the scope of this contribution. Environment-related issues, such as environmental occupational health and environmental sciences, are among the top 5 disciplinary domains related to the extensive literature (

Web of Science, a total of > 580,000 publications as of the end of July 2024) on the COVID-19 pandemic. While pandemic research primarily focuses on Medicine, epidemiology, and therapeutic aspects of COVID-19, 13.5% of the research is directed towards broader environmental issues. This significant amount of published research reflects the disruptive consequences in almost every aspect of human life and activity [[

14], Fig. 2], including interactions with nature and wildlife [

15]. The worldwide reduced human presence, mobility, and slowing-down of human-made pressures during the pandemic have provided a ‘once-in-a-lifetime,’ unplanned, serendipitous opportunity to gather and synthesize empirical evidence on human-wildlife or nature interactions, often referred to as the “Global Human Confinement Experiment” [

14] or the “Anthropause Perturbation Experiment” [

16]. This has involved methodologically challenging field observation measurements [

17], qualitative methods, often quite time and resource-intensive, for evaluating people’s perceptions [

18], and big data for assessing public perceptions of this particular condition through culturomics-derived methods, technologies, and digital communities [

19,

20]. Most published empirical evidence on reduced human mobility during ‘lockdowns’ contributes to conservation science-making through the accumulation of case studies and the search for statistical regularities [

14,

21,

22]. A few have proposed to proceed from theoretical to singular explanations. Notable examples of this approach include the neological concepts of Anthropause [

23] and Anthropulse [

24], as well as ‘multiple human geographies’ [

25].

The evidence and data discussed here are based on protocols and techniques of conservation culturomics [

20] and infodemiology (or infoveillance) [

26,

27]. These methods leverage the billions of internet users and the widespread use of social media to study public perceptions on emerging topics, e.g., hereto health issues, at exponentially greater scales than was previously possible through targeted surveys and focus groups [

28]. They also help widen the participation and the inclusion of underrepresented social groups in such studies. The search strings used in publication databases may vary, but the main corpus is almost similar. For example, a search string for “(COVID OR pandemic) AND Google Trends” yields around 930 papers in the

Web of Science as of the end of April 2024. This search string aimed to capture different aspects of ‘infodemiology’ practice during and after the pandemic to measure public interest through individual searches on web search engines. On the other hand, a stricter search string like “(COVID OR pandemic) AND infodemiology” resulted in 335 papers in the same database. The difference is a medical-oriented subset of the first search, which includes papers focusing on the economy, policymaking, education, tourism, crime, home violence, addictions, environmental issues, and more.

The pandemic-related environmental literature has yielded several key but sporadic findings, whether connected to the “Global Human Confinement Experiment” [

14], the “Anthropause Perturbation Experiment” [

16], or the culturomics and ‘infodemiology’ science practices [

20,

29]. However, as mentioned in [21, p.9], the “initial observations painted a rosy picture of wildlife “rebounding” (for a synthesis, [

21,

22]), are now being challenged by a return to pre-pandemic levels of human activity and perceptions, i.e., the ‘human post-pandemic materialism rebound’, [

24,

30,

31,

32]. After carefully examining this particular oscillation [

33] (see Discussion section), one would realize that it is unsupported to conclude or attribute causal effects on potential shifts in environmental awareness related to the post-modern concepts of sustainability, climate change, and biodiversity [

34], particularly due to or ‘activated’ by the multiple impacts of the pandemic to the society.

Here, we propose an alternative approach to address the potential downsides of conservation narratives related to the pandemic. These issues are often present in Ecology and environmental science methods more generally [

5,

35,

36,

37]. The goal is to move away from the idea (or even paradigm) of ‘humans as custodians of biodiversity (or nature)’ [

21,

22] and instead focus on humanity’s dedication to studying, understanding, and preparing for the consequences of combined social and natural extremes and global crises [

38].

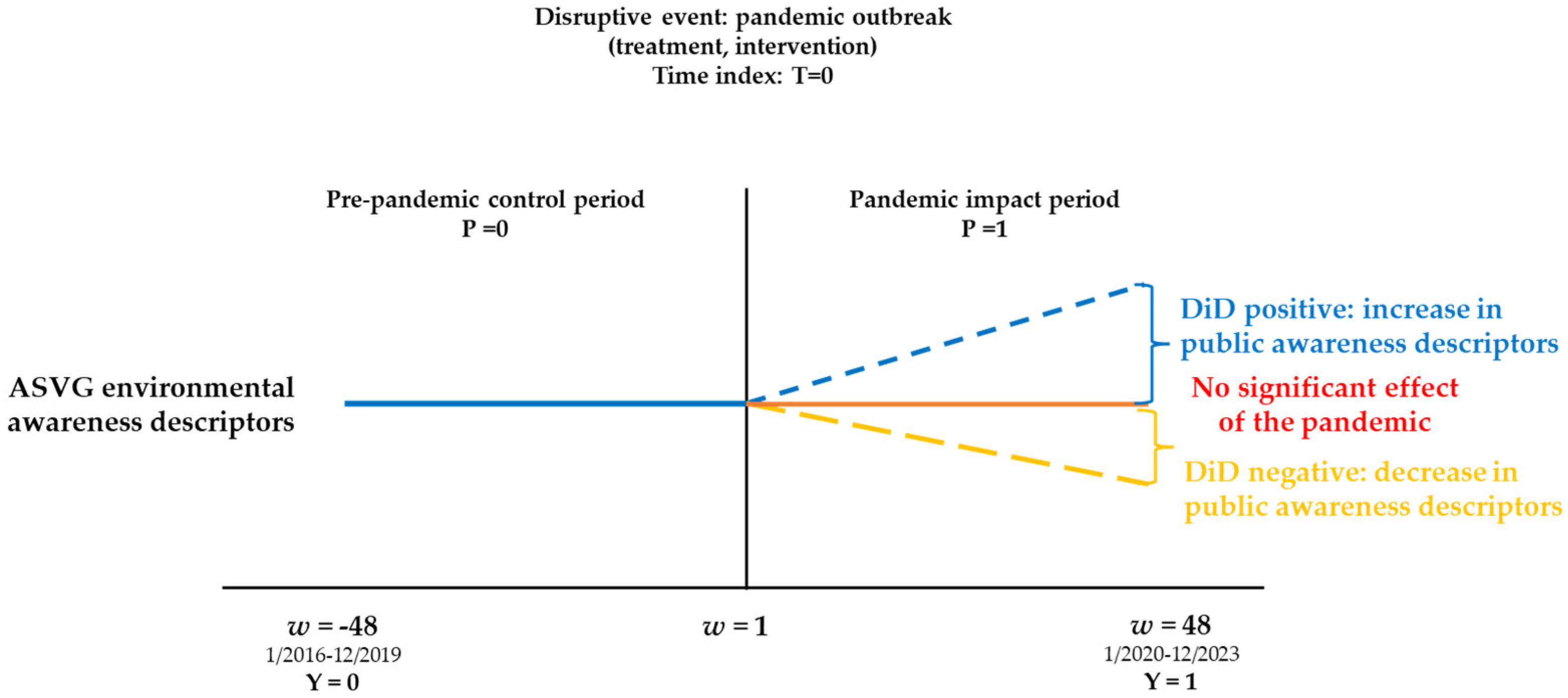

Additionally, we need an unbiased estimate of the treatment effect or various disruptive events such as a new policy intervention, novel economic measure, or a social or natural event -in this case, the pandemic outbreak. We want to know if the change of the outcome variable in the treated group would have been the same as the change in the control group in the absence of treatment. Then, we have a situation known as “parallel trends” [

39,

40]. In simpler terms, if there had been no COVID-19 outbreak, the dependent variable of a treated group in a linear regression, such as an environmental awareness descriptor, should have been the same as the difference of the control or untreated group during the same period. Although the difference-in-differences (DiD) method was originally developed at the end of the 19

th century for epidemiological purposes, it is currently a widely used tool for estimating causal effects in various fields, such as econometrics. The DiD method compares changes in an outcome over time between an intervention and control group, making it useful for estimating causal effects at the group level rather than at the individual level. It is important to note that DiD estimates the average effect of the ‘treatment’ or ‘intervention’ on the outcome in the group exposed to the intervention.

An influential paper on applying the DiD method and its potential extensions in the relationship between the pandemic and environmental awareness is by Rousseau and Deschacht [

41]. Despite the partial findings and the method's short time bandwidth (2 to 10 weeks), the study's linear regression modeling of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on natural and environmental awareness, utilizing the DiD method, provides a new perspective in infodemiology [

29] and conservation culturomics [

20,

42]. The authors assumed that the time of switch (T=0; Tuesday, March 14, 2020) between the pre-pandemic period (control) and the pandemic period (treatment) the date the state of the COVID-19 pandemic was the date the COVID-19 pandemic The authors assumed that the time of the switch (T=0; Tuesday, March 14, 2020) between the pre-pandemic period (control) and the pandemic period (treatment) was the date the COVID-19 pandemic was declared by the WHO, which was March 11, 2020. The study focused on 20 European countries, and the regression analyses were based on 2400 observations, covering 10 weeks of data in 2020 and the same weeks of data in the control year, 2019. The study looked at 6 topics related to natural and environmental awareness, which were measured using the search volume on the web and the normalized Google Trends platform.

In the following sections, we will outline our approach to tackling the challenge outlined in the title. We will detail the technical and methodological solutions we have implemented, explain our rationale for selecting the UK as a model case, and explore the benefits of employing causal inference rather than providing a narrative explanation of empirical evidence.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, we present four basic components of our methodology. First, the technique to control the effect of the COVID-19 crisis or disruption event on environmental awareness descriptor is obtained by estimating the linear regression equation in its simplest form:

where: ASVG is the Absolute Search Volume in Google in week

t for the descriptor

i; P is a dummy variable indicating the control period (pre-pandemic) when equals 0 and the pandemic impact period (treatment or intervention period) when equals 1; Y is a dummy variable distinguishing the control years (2016-2019) (Y = 0) from the years 2020-2023 in which the COVID-19 crisis occurred (Y = 1). The estimator δ

DiD might result as a coefficient of the linear regression (1).

Practically, DiD is a valuable statistical technique used to determine the causal effect of a treatment or intervention by comparing the changes in outcomes over time between a treatment group and a control group in observational studies where randomization is not possible. In our case, we measure the outcome for the same group both before and after the treatment event, which in this case is the COVID-19 outbreak. The DiD method can be represented theoretically using expectation notation:

In simpler terms, it represents the average outcome that one would expect if they could repeat the process an infinite number of times. A simplified procedure of comparing the means of two paired samples is an acceptable alternative to treating the pre- vs. post-pandemic groups’ environmental awareness descriptors.

Figure 1 offers an idealized presentation of the methodology and the variables used in the equations.

Note that the outcome ASVG (Absolute Search Volume Google Trends) data series is used here to measure the absolute number of individual searches instead of using a normalized scale of 0-100. This data is made available through the Enhanced Google Trends Supercharged Extension-Glimpse tool, which provides real-time search volume for any keyword, and the traditional normalized Google Trends tool. This topic has been the subject of extensive discussion in conservation culturomics and infodemiology research for over a decade (for further analysis, refer to the Discussion section). The ASVG time signatures were created for the environmental awareness keywords 'biodiversity,' 'climate change,' and 'sustainability.' Due to significant fluctuations in search volumes over different periods, the ASVGs were smoothed using the adjacent-averaging method. A 4th-degree polynomial trend line, 95% confidence interval, and 95% prediction band were fitted to the smoothed ASVGs.

The expectation notation simplifies the statistical treatment of the data since each descriptor is controlled separately here. The data series for each ASVG was split into two equal parts, with the first week of January 2020 as the dividing line. For comparison, each data point from 1/2020-12/2023 was matched with its equivalent from 1/2016-12/2019. Control checks were carried out to ensure that the differences between the paired samples were within acceptable limits, including checks for normality and outlier numbers. Specifically for the climate change ASVG data series, a modified distribution was created to reduce the number of outliers. Any outliers were replaced with the overall average of the ASVG data series, regardless of whether they were outliers.

The second component is to choose the UK and English languages as solid examples for the methodology. We chose the UK as a model country and English as a language to reduce information noise and biases on public interest regarding the symbolic keywords of environmental awareness being examined. Approximately 59% of internet websites are in English. About 2 billion internet users (out of a total of 5.35 billion users globally in 2024) search in English, indicating that it is the

lingua franca of modern times. The UK internet users’ community represents over 96% of the country's population, and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) provides detailed information on the socio-demographics of internet users. Furthermore, UK citizens have a strong cultural connection and tradition with nature, landscapes, and environmentally friendly activities, such as birdwatching, horticulture, gardening, and so on [

28,

43]. However, using English as the only search criterion in the Google engine, regardless of the country, will significantly obscure the international cultural factors of public interest (for further analysis, refer to the Discussion section).

The third component is to create the ASVG signature for UK citizens regarding health issues, specifically contagious diseases. This signature is a reference point for citizens' attitudes and interests in public health issues. The targeted keywords used in this effort are 'pathogens' and 'infectious diseases'. However, no data is available for the more relevant keyword 'emerging diseases'. The assumption is that 'pathogens' represent general knowledge of viruses and microbes, while 'infectious diseases' indicate a significant public health concern. In addition to controlling the AVGS signatures, we adjusted the recorded search volumes to account for changes in the size of the UK population and internet usage rates. This calibration was done to align the ASVG signatures with the actual UK population conducting searches (from 2004 to 2023, according to ONS data).

The fourth component involves analyzing the ASVG signal related to 'infectious diseases' to identify significant trends in COVID-19, particularly focusing on the development of the pandemic in the UK. This is based on the weekly aggregated data of new cases and deaths recorded from December 2019 to December 2023, obtained from the World Health Organization's COVID-19 dashboard data (

https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/data). Additionally, we tracked the daily flow of information in the UK, including broadcast, print, and web news, using data from The GDELT project (

https://www.gdeltproject.org/) between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2023, specifically related to COVID-19 and 'new deaths'. It's important to note that our attention was on articles with predominantly negative content regarding these topics.

Downloaded data from various sources were organized in Excel 365, signal analysis treatments were performed on OriginPro 2024, and statistical analysis was performed on SPSS v.28.

3. Results

The results are presented in four sections. The first section compares factors of interest using box-and-whisker plots (

Figure 2). In addition to providing a summary of descriptive statistics for each descriptor, these plots effectively visualize the comparisons between them and indicate the extent of outliers. The focus here is on the range of values representing the level of public interest in the UK for each descriptor. Public interest in environmental awareness concepts peaks at approximately 15,000, while interest in health issues reaches around 5,000, with outliers occurring in specific time periods. However, under extreme conditions such as COVID-19 and the pandemic, public interest in health issues reaches approximately 15x10

6. Within each descriptor category, differences are clearly displayed. For example, while climate change generates significant public interest, sustainability - despite being a global strategy for human activities - and biodiversity, the biotic basis for quality of life and human well-being, lag behind, likely appealing to some specific 'niche' public (

Figure 1A).

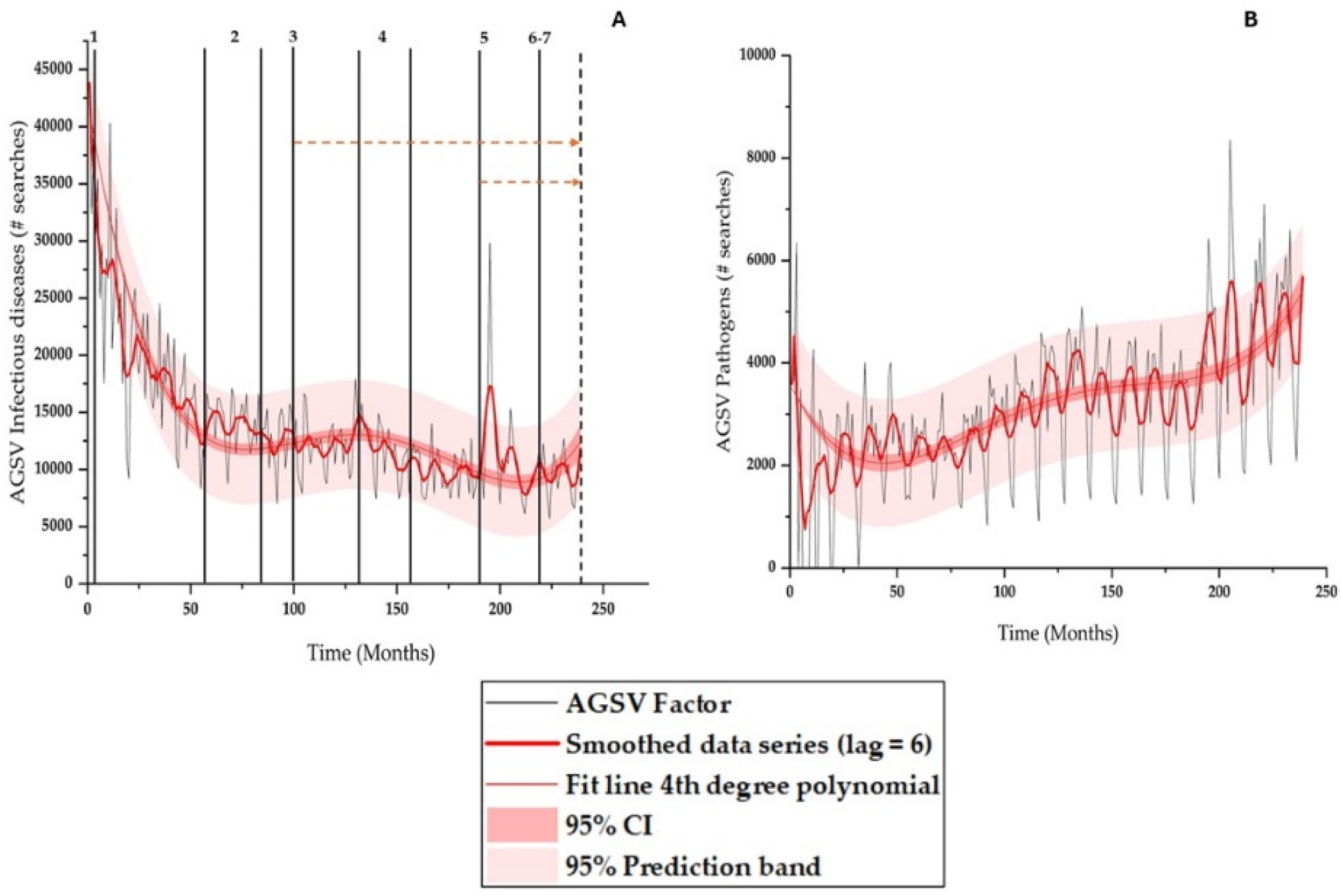

The second section examines the UK public's interest level in emerging diseases. This complex concept is important for medicine and public health and is influenced by biological, ecological, and environmental processes. Understanding the UK public's opinions on the pandemic and public health issues could help us better grasp their sensitivity and responsiveness to environmental concerns. The study provides an overview of public interest in pathogens and infectious diseases, as shown in

Figure 2B and

Figure 3B.

Figure 2B indicates a baseline level of interest in pathogens, with an average of about 3,180 monthly searches over 20 years. We also observe peaks in public interest in infectious diseases (

Figure 3A), particularly during global epidemics such as SARS, swine flu, MERS, Zika virus, COVID-19, children's hepatitis adenovirus AF41, and monkeypox. Notably, this list does not include cases like the HIV pandemic, Ebola outbreaks, or avian influenza H5N1. When considering the number of active searchers over time, the study found that public interest in infectious diseases decreased while interest in pathogens nearly doubled.

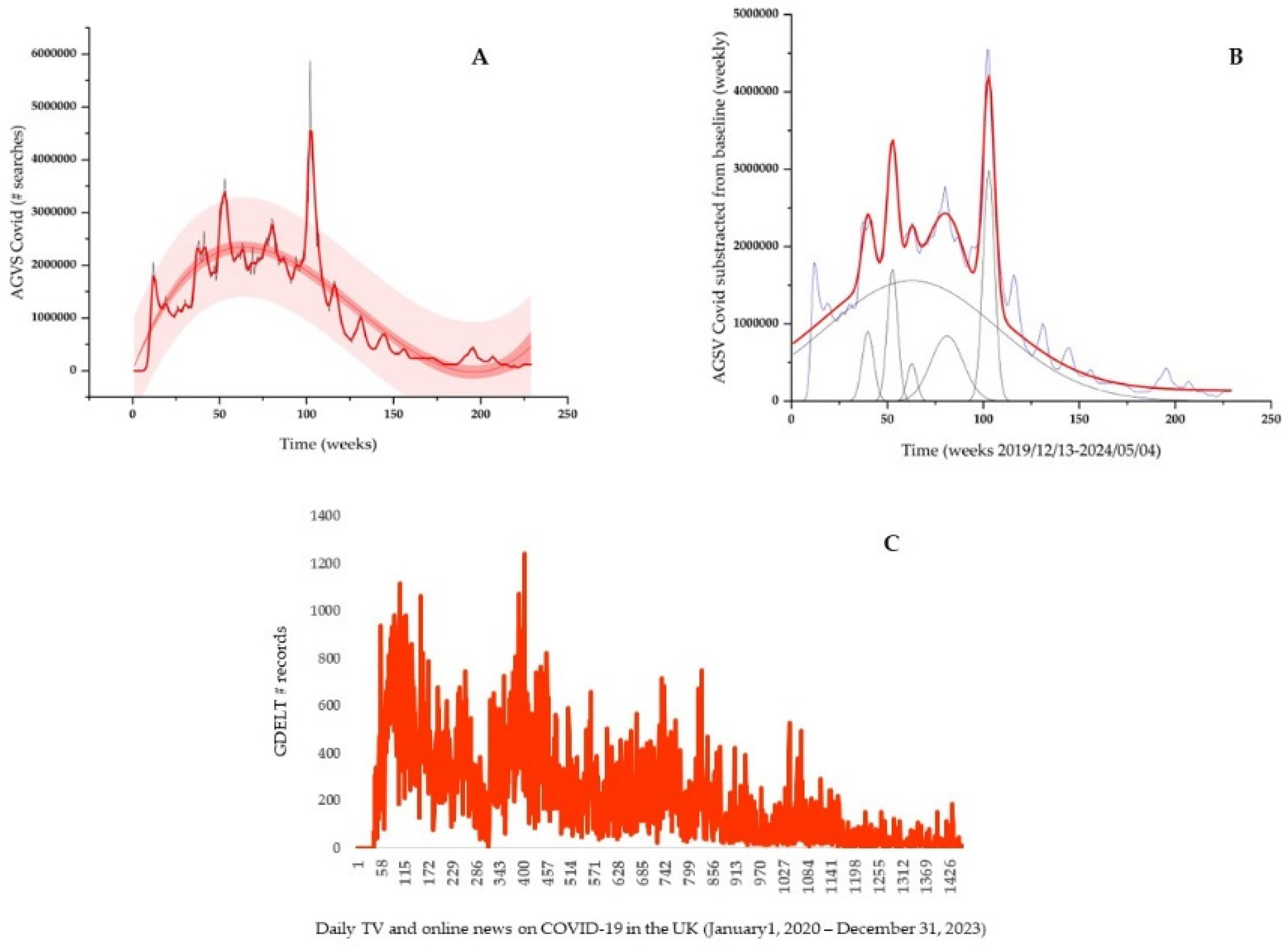

The third section discusses the level of public interest in the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK.

Figure 4 provides a summary of our findings.

Figure 4A presents a 4th-degree polynomial fit line of the weekly AGSV COVID-19, using smoothing after the adjacent-averaging method with a lag = 2. The polynomial fitting of the AGSV shows an R

2 value of 0.98 and a highly significant ANOVA (a = 0.05, p<0.0001).

Figure 4B shows the Gaussian deconvolution of the AGSV COVID-19 at a monthly scale. The AGSV is constructed based on a series of hidden secondary peaks on a general truncated Gaussian distribution from December 2019 to December 2023. During this period, five significant secondary peaks are identified, leading to overall observed peaks and drops in public interest response. These secondary peaks may be explained by the epidemiological evolution of the disease, such as the announcement of new cases and deaths by public health authorities in the UK, which are reflected in the population's emotions, sentiments, and other psychological effects [

44].

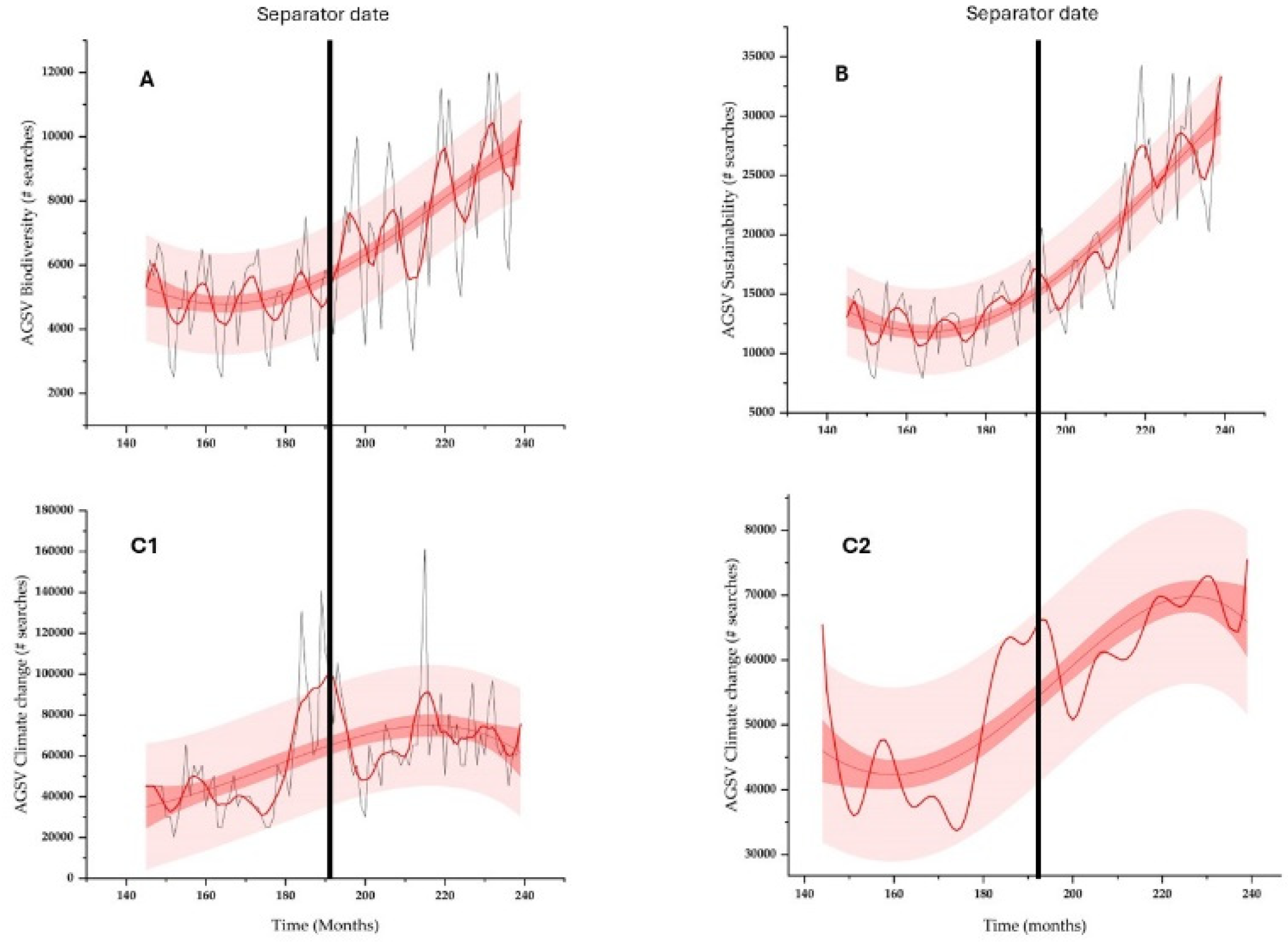

In this contribution, the fourth section is particularly interesting. The approach by Rousseau and Deschacht [

41] was extended to cover the entire COVID-19 period, along with 48 months for web searches on biodiversity, climate change, and sustainability before the pandemic. These findings might offer a different perspective on the relationship between public interest in public health and environmental issues. The separator date is set at month 192 of the AGSV data period, week 4 of December 2019 when the news of the Wuhan eruption first appeared.

.

Figure 5 presents the corresponding AGSVs, which are smoothed and fitted to a 4th-degree polynomial. A visual inspection of AGSV trajectories suggests that public interest in biodiversity, climate change, and sustainability increased significantly during the pandemic, contrary to decreased interest in environmental awareness keywords. Special attention is given to the AGSV climate change. Sporadic search peaks before or after the separator date are depicted in

Figure 5 C1, which may affect the comparison of means. To address this, outliers in the AGSV climate change distribution were replaced by the average of the entire distribution, including the outliers in the calculation (

Figure 5 C2).

Table 1 presents a statistical summary of the previous data.

Table 2 compares the average values of AGSVs before and after the separator date. In all cases, Cohen's effect size measure is greater than 1, indicating that approximately 90% of the control group (AGSVs before the pandemic) falls below the mean of the experimental group (AGSVs after the onset of the pandemic). This suggests that the group means differ by more than one standard deviation. Pearson's correlation coefficient shows that all correlation values are approximately 0.3 or less, indicating a weak association between the two sets of AGSVs.

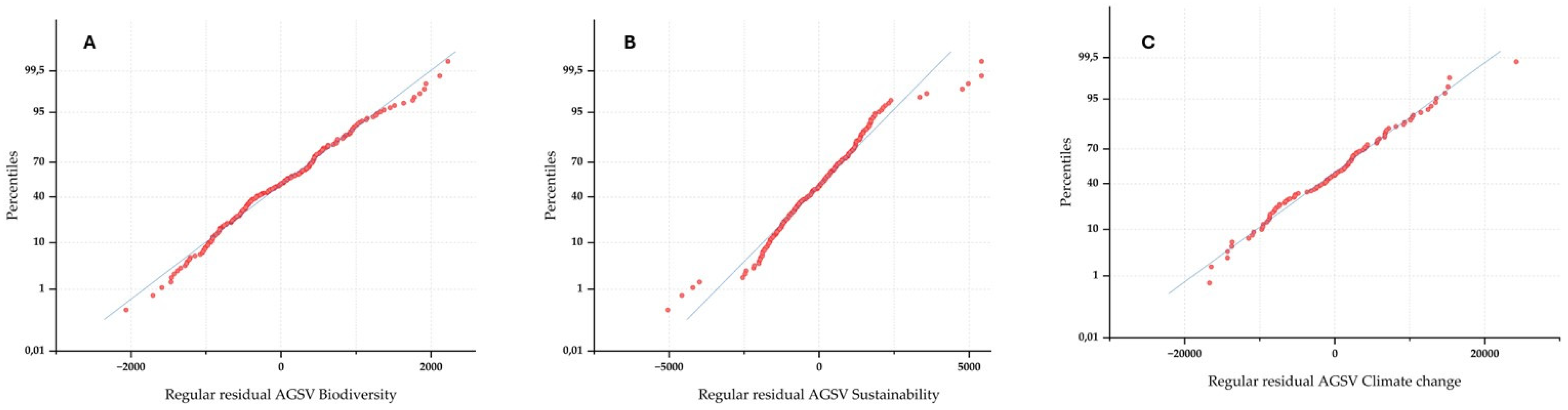

Additionally, the quantile regression estimates the relationship between the time predictor and the AGSVs response across all distribution parts (

Figure 6). The regular residuals of the 4th-degree polynomial model for environment-related keywords (AGSVs) against theoretical percentiles indicate that the fundamental assumption in regression analysis, i.e., the variance in the response variables AGSVs of all regions of the distributions (percentiles 10-90%), is not heterogeneous, in addition to their means.

4. Discussion

The discussion is organized into three main points. The first part builds on the 'double rebound' narrative [

21,

22,

24,

30,

31,

32] introduced in the Introduction section and includes additional important considerations: circular arguments and the disconnect between health and environmental priorities. The second part is technical and outlines potential improvements or variations from the previous paper by Rousseau & Deschacht [

41]. The third part aims to use our findings as a catalyst for developing a new, positive narrative for environmental and biodiversity conservation [

5].

‘Argument circularity’ is indirectly emerging in hundreds of publications. Somehow, it is connected to the ‘rosy picture of wildlife “rebounding" [

21]. Simplistically, it can be read as ‘fewer humans or activities, fewer impacts or pressures on wildlife or nature.’ Examples refer to a decrease in animal road mortality, extension of species territories, changes in relative abundances of species in communities, reduction of noise pollution, hunting or fishing, etc. Some argue that this perspective aligns with neo-Malthusian [

45] and de-growth [

46] narratives. The genuine question is whether this pattern constitutes an unavoidable tautology [

47] vs. [

48] and whether it could hinder conservation efforts in the post-pandemic era [

49].

The extensive literature ultimately emphasizes the "dissociation between health and environmental priorities". In their comprehensive review, Bates et al. [[

21], p. 15] acknowledge that "both positive and negative impacts of human confinement do not support the view that biodiversity and the environment will predominantly benefit from reduced human activity during lockdown." According to the authors, "the negative impacts of the lockdown on biodiversity result from the disruption of human efforts to conserve nature through research, restoration, conservation interventions, and enforcement." Similar statements can be found in other literature. For instance, the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic has consistently reduced public interest in climate change in the USA [

50]). Furthermore, interest in conservation actions, particularly searches related to national parks, has decreased since 2019, likely due to the pandemic [

51]. While the increased public awareness of health-environment connections during the pandemic could theoretically benefit conservation efforts, there are misleading negative associations between wildlife and zoonotic diseases that may harm the role of biodiversity loss in disease spillover and outbreak in the long term [

52]. However, contrary findings have been reported from traditional polling exercises, showing that the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increased concern for climate change and public support for green recovery policies [

53].

As Soulé [[

54], p. 727] pointed out, "Conservation biology is often a crisis discipline." This axiomatic almost statement has never been more relevant than during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human mobility, activities, and the intensity of pressures on the environment and nature have been significantly reduced or disrupted for public health reasons. This temporary disruption has brought to light challenges to conservation science and pro-conservation storytelling [

55]. Terms and concepts such as the Anthropocene, biodiversity, sustainability, climate change, and methods related to scenario construction and big data exploration can be considered "postmodern" and seen as ushering in a different historical era and type of society [

34]. These concepts did not exist when Soulé envisioned conservation as a crisis discipline based on coupled functional and normative postulates. It's not surprising to note that publications emphasizing changes, shifts, and advances over Soulé's original vision appeared decades later [

56,

57]. Although it is humanly unattainable to examine the nearly 40,000 publications listed in the

Web of Science after the search string ‘(covid OR pandemic) AND (conservation OR environment*)' as of the end of April 2024, unless through bibliometric techniques [

58], it is accurate to assert two significant components of this massive literature. The first is the replication crisis, and the other is the ‘existentialist narrative crisis,’ which revolves around i.e., articulated around nature's implicit values, extended to eco-centric, spiritual, or ethical arguments on the one hand vs. anthropo-centric or utilitarian.

The replication crisis is clearly evident. Almost none of the reported empirical evidence or observations on the impacts or effects of pandemic conditions on biodiversity, sustainability, or climate change is replicable or reproducible, as elementarily required within the noble Popperian paradigm. On the contrary, even positive effects, however temporary, can be seen as anomalies to widely entrenched trends or predictions regarding the decline of human life-support systems and the Earth system. One might argue that the transition toward Kuhn’s [

59] interpretation of paradigm shift, i.e., accumulation of contradictory data that the existing explanation cannot predict, remains incomplete or has not been fully realized regarding the call for a ‘new narrative’ for conservation after the lessons of the pandemic [

38,

60,

61,

62].

Analyzing a considerable amount of discussion sections of relevant literature, a motif emerges when prescribing, mobilizing, and inspiring action for the future. This is often accompanied by arguments about why destructive, ineffective, or unjust conservation or environmental policies persist. Expressive differences or variations in narrative shape unavoidably exist. For example, the emblematic paper by Bates et al. [

21] resumes the synthesis of the ‘global human confinement experiment’ calling for “strengthen[-ing] the important role of people as custodians of biodiversity, with benefits in reducing the risks of future pandemics.” One could position this call at the interface of spiritual and ethical conservation narratives [

7] and anthropocentrism in the sense of the Millenium Ecosystem Assessment [

63], i.e., nature underpins human society and economy and, therefore, must be conserved. Rutz et al. [

23], when introducing the concept of Anthropause, refer to the drastic, sudden, and widespread, i.e., unprecedented, circumstances of human confinement as “providing important guidance on how best to share space [with animals] on this crowded planet” and “shaping a sustainable future.” One could get hold of elements of the nature-based solutions perspective [

64] and even aspects of eco-modernization [

65]. Overall, the narratives of the pandemic conservation- and environment-related literature insist on how relevant problems are defined, which actors should do what, what solutions are desirable, and how laws, programs, policies, and funding streams flow. Social sciences, cognitive science, or development studies specialists would easily recognize such narrative constructs decades ago [

66,

67].

I believe the paper by Rousseau & Deschacht [

41] provides an appealing and commendable example of the analysis mentioned earlier. Their introduction of the DiD approach is an innovative way to address public awareness of nature-related and environmental topics during the pandemic. However, the authors seem somewhat anchored in existential risk narratives in their discussion. This critique may seem severe, but I think their findings could contribute to developing much-needed optimistic messaging in the search for a new conservation narrative [

6] if they connect their positive findings with messaging perspectives that encourage people's engagement and action. Inspired by Rousseau & Deschacht's [

41] methodological approach, we tried (1) to diversify the technical potential of the DiD approach and (2), most importantly, to develop arguments on what Louder & Wyborn [

5] conclude: “The stories of old are not achieving the goals they were meant to, and conservationists need to think critically about the narratives that they deploy.”

First, the main variable we are focusing on in our analysis is the Absolute Google Search Volume (AGSV) per keyword instead of the Search Popularity Indicator (SPI) per keyword, used by Rousseau & Deschacht [

41]. The key difference between AGSVs and SPIs lies in using data on actual search volumes (per time unit, country, or language) in the former format, as opposed to relative normalized (on a scale of 0-100) search volumes in the latter. As explained in the Methods section, this was made possible after the release of the Enhanced Google Trends Supercharged Extension-Glimpse tool. There have been doubts or objections to the results obtained on public interest estimates using the standard Google Trends algorithms, especially in conservation topics, environment-related issues [

68], and infodemiology [

69,

70], which have been debated until recently. Among the limitations of this methodology [

71], the main one is related to the fact that the Google Trends algorithm normalizes the search volumes, making it unlikely to produce accurate results for longer-term trends [

72,

73]. Additionally, Google Trends requires a minimum number of searches to create a trend line, but Google did not initially disclose the specific threshold.

Second, we consider an AGSV keyword (or topic) trajectory to represent public interest in a particular country, language, and period. This representation is measured in terms of searches recorded in Google engines. Similar to how signals are often distorted or altered when instrumentally recorded in physics, biology, or Earth sciences, the actual signal in Google searches can be affected somehow. Errors in Google searches could result from typos or users' misunderstandings. Therefore, mathematical processes such as deconvolution or Fourier transform could be applied, commonly used in signal or image processing. However, deconvolution is a complex process that can be influenced by noise in the data, and it may not always lead to the perfect recovery of the original signal.

In the case of COVID-19 AGSV signal, repetitive searches by the same individuals at different times as the pandemic and epidemiological conditions evolved rapidly might distort the signal. As depicted in

Figure 4B, the deconvolution operation helped unveil many hidden peaks in public interest using the 2nd derivative of the convoluted signal. The 2nd derivative changes sign at the location of a peak: it is positive just before the peak and negative just after. This condition may differ, in at least an intuitive but plausible manner, in the cases of AGSVs for the keywords biodiversity, climate change, and sustainability. For example, an individual interested in biodiversity might conduct a new search for the same keyword under exceptional conditions. Therefore, we support the idea that the increases in AGSVs/keywords we identified in this research reflect the engagement of new, additional population segments.

Third, in their work, Rousseau & Deschacht [

41] emphasized the importance of the DiD approach and the time bandwidth they utilized, aiming at identifying causal effects in regression-based strategies following [

74]. In their study, the 'treatment group' comprised the general public after the onset of the pandemic. In contrast, the control group consisted of the 'same' public before the virus outbreak, during a similar short period (2-10 weeks in Spring 2020 vs. Spring 2019). The metric used was the SPI measured in normalized Google Trends searches. They employed linear regression to address the assumption of parallel trends and included confounders such as controls for country-fixed effects.

It is important to note that the study aimed to mitigate cultural and experiential variations within the pool of 20 countries included in the sample. For example, it compared the UK's response to the Italian reaction during the Bergamo plague. However, the time-bandwidth was identified as a significant factor affecting the accuracy of their predictions. The short-term nature of the observations is unlikely to yield realistic results. Additionally, even in May 2024, Google Trends continues to record individual searches, one year after WHO declared an end to the global health emergency of COVID-19. As a variation to this approach, we extended the time bandwidth to 96 weeks, from January 2016 to December 2023. Besides using AGSVs for the environment-related flag keywords, we compared means of paired samples for one country, emphasizing Cohen’s d measure of effect size and Pearson’s

r correlation. Although Cohen’s d may be over-inflated because the size of the samples is < 50, the effect size is large, i.e., > 0.8, and significant differences are uncovered by the t-test and ANOVA results (

Table 2). Pearson’s r corroborates these results.

Our findings on environmental issues allow us to deliver an encouraging message that resonates with the public and a wide audience [

75]. The way the environment is portrayed in public discussions, and discourse involves both facts and language. Following the ideas of Lakoff [

76], one could better understand how the repetition of certain words (e.g., 6

th mass extinction, precipice) or the use of narrative symbols (e.g., custodian or steward of nature) and metaphors (e.g., Anthropause) can function as a type of ideological language that reinforces certain beliefs in a listener's mind. If these facts don't align with their ideology or frame of reference, they are likely to be disregarded. Seeking to align facts and evidence and appealing to reason and rationality when it comes to conservation may, in reality, be a defensive response stemming from concerns among conservationists that the focus on climate change might overshadow the equally critical issue of biodiversity loss [

77,

78,

79,

80]. Attributing such concerns to typical academic discipline rivalry would be an oversimplification. According to the "Literature review on contemporary public views of climate change and biodiversity loss in the UK" (2023) commissioned by the Royal Society, over 83% of UK citizens are concerned about climate change, while only 49% of the public is aware of biodiversity loss. The report's conclusion emphasizes the need for collective action, informed public engagement, and prioritization of conservation efforts to address climate change and protect biodiversity.

Optimistic messaging is not a unique, sui generis version of the new conservation narrative. Langhammer et al. (2024) provided meta-analytical evidence showing that conservation actions worldwide are effective in halting and reversing biodiversity loss in 66% of cases compared to taking no action. Rousseau & Deschacht (41) reported a precise and rapid increase in the search for nature-related topics during the COVID-19 crisis after March 14th, 2020. However, they mentioned limitations in their data and time frame. They found that environment-related issues did not significantly increase after the Covid-19 crisis.

Our paper focuses exclusively on environment-related topics, and the results appear robust. Public interest in biodiversity and sustainability increased exponentially during the pandemic (

Figure 5 A, B). If instead of the 4th-degree polynomial fitting, we used it for reasons of comparison of AGSVs of all keywords controlled, including climate change, we applied nonlinear exponential fit, biodiversity presents R

2 = 0.93 (ANOVA significant at p < 0.001) and sustainability, R

2 = 0.94 (ANOVA significant at p < 0.001). On the contrary, the climate change AGSV (with corrected outliers) fits a waveform non-linear function (R

2 = 0.72; ANOVA significant at p < 0.001).

It is important to determine whether this is a unique cultural trend in the UK or if there are similar shifts in public opinion on a broader scale. But before making comparisons or generalizations, we need to standardize the data such as population size, internet usage, demographics, literacy rates, economic status, and freedom of speech. Social research, especially sentiment analysis, should investigate the sudden increase in public interest in biodiversity and sustainability. Is it just a temporary coincidence unrelated to the pandemic, or is it a serendipitous reframing of environmental issues as crucial aspects of the growing discussion on existential risks? Various distressing events, such as global economic downturns, emerging diseases, war, unregulated technologies like AI, and even Brexit in the case of the UK, amplify feelings of uncertainty among citizens. Our findings should cautiously be interpreted as a sign of hidden or secondary thought processes that traditional qualitative social research methods may overlook. While it's clear that climate change dominates public interest in the UK with approximately 13.5 million searches, compared to biodiversity with about 1.7 million and sustainability with roughly 3.5 million searches from 2004 to 2023, the long-term trends we have observed show significant fluctuations in public interest in climate change. This presents an opportunity to understand better the importance of biodiversity and sustainability in human well-being and as a pathway to securing a sustainable future.

5. Conclusions

It might be time to shift from a pessimistic "doomsday" narrative to one emphasizing individual action and responsibility in addressing existential risks. While the COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating, it could also serve as a wake-up call to highlight the connection between global health and planetary changes such as climate issues, loss of biodiversity, and the emergence of new diseases. The pandemic has made the concept of crisis more relatable and immediate to individuals, reminding us of the original meaning of the word "crisis" in Greek, which signifies a turning point or a moment of intense difficulty and danger requiring a crucial decision. In Chinese, it combines the characters for "danger" and "opportunity," emphasizing the potential for change.

For example, before the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, a study estimated that more than 5,000,000 deaths per year globally were attributable to non-optimal temperatures over a 20-year period, accounting for 9.43% of all annual deaths [82]. In comparison, COVID-19 caused approximately 6,880,000 deaths globally over three years. During the same period, it was projected that more than 15,000,000 deaths would occur due to climate change-related non-optimal temperatures. Furthermore, a dynamic DiD study on individuals' beliefs about extreme events found that only fires had a small but statistically significant effect on recognizing the existence of climate change and supporting the need for action. However, this effect diminished over time [83].

While our findings are limited to a specific country and its singular mental heritage, they offer a promising perspective for apprehending future shifts in a broader public conversation on human-nature interactions as determinants of existential safety vs. risks.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Data Availability Statement

The data are in the public domain and searchable at the Enhanced Google Trends Supercharged Extension-Glimpse tool and The GDELT Project.

Conflicts of Interest

“The author declares no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Lubchenco J. Entering the Century of the Environment: A New Social Contract for Science. Science, 1998, 279, 491-497. [CrossRef]

- Anderson C. The end of theory: the data deluge makes the scientific method obsolete. Wired Magazine, 2008. https://www.wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory/.

- Bostrom, N. Existential risk prevention as global priority. Global Policy, 2013, 4(1), 15–31. [CrossRef]

- Moynihan T. Existential risk and human extinction: An intellectual history. Futures, 2020, 116, 102495. [CrossRef]

- Louder, E.; Wyborn, C. Biodiversity narratives: stories of the evolving conservation landscape. Environmental Conservation, 2020, 47, 251-259. [CrossRef]

- Balmford A.; Knowlton N. Why Earth optimism? Science, 2017, 356 (6335), 225–225.

- Negi C.S. Religion and biodiversity conservation: not a mere analogy. International Journal of Biodiversity Science & Management 2005, 1 (2), 85–96.

- Soulé M.E. What is conservation biology? Bioscience, 1985, 35 (11), 727–734.

- Kareiva P.; Marvier M. What is conservation science? BioScience, 2012, 62 (11), 962–969.

- Dahlstrom M.F. Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111, 13614–13620. [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Goldszmidt, R. et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nature Human Behavior, 2021, 5, 529–538. [CrossRef]

- Bostrom N. Existential risks: Analyzing human extinction scenarios and related hazards. Journal of Evolution and Technology, 2002, 9 [Available at http://jetpress.org/volume9/risks.html ].

- Bostrom N; Cirkovic M; Rees M.J. Global Catastrophic Risks. 2008. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Bates AE; Primack RB; Moraga P; Duarte CM. COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown as a "Global Human Confinement Experiment" to investigate biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation, 2020, 248, 108665. [CrossRef]

- Corlett RT; Primack RB; Devictor V; Maas B; Goswami VR; Bates AE; Koh LP; Regan TJ; Loyola R; Pakeman RJ; Cumming GS; Pidgeon A; Johns D; Roth R. Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation, 2020, 246, 108571. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, SE; Shilling, F; Collinson, W. Anthropause Opportunities: Experimental Perturbation of Road Traffic and the Potential Effects on Wildlife. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 2022, 10, 833129. [CrossRef]

- Wheater CP.; Bell JR.; Cook PA. Practical field ecology: A project guide. 2020 John Wiley & Sons, 480 p. ISBN 1119413230, 9781119413233.

- Bhattacherjee A. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods and Practices (Revised edition). 2019 Available at: https://usq.pressbooks.pub/socialscienceresearch.

- Michel, JB.; Shen, YK.; Aiden, AP.; Veres, A.; Gray, MK.; Pickett, JP.; Hoiberg, D.; Clancy, D.; Norvig, P.; Orwant, J.; Pinker, S.; Nowak, MA.; Aiden, EL. Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books. Science, 2011 331, 6014, 176-182. [CrossRef]

- Correia, RA.; Ladle, R.; Jaric, I.; Malhado, ACM.; Mittermeier, JC.; Roll, U.; Soriano-Redondo, A.; Veríssimo, D.; Fink, C.; Hausmann, A.; Guedes-Santos, J.; Vardi, R.; Di Minin, E.. Digital data sources and methods for conservation culturomics. Conservation Biology, 2021 35, 2, 398-411. [CrossRef]

- Bates AE.; Primack RB.; Duarte CM.; et al., Global COVID-19 lockdown highlights humans as both threats and custodians of the environment, Biological Conservation, 2021, 109175. [CrossRef]

- Primack RB.; Bates AE.; Duarte CM. The conservation and ecological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Biological Conservation, 2021, 260, 109204. [CrossRef]

- Rutz C.; Loretto MC.; Bates AE.; Davidson SC.; Duarte CM.; Jetz W,; Johnson M.; Kato A.; Kays R.; Mueller T.; Primack RB.; Ropert-Coudert Y.; Tucker MA.; Wikelski M.; Cagnacci, F. COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife. Nature, Ecology, Evolution, 2020 4, 9, 1156-1159. [CrossRef]

- Rutz, C. Studying pauses and pulses in human mobility and their environmental impacts. Nature Reviews|Earth & Environment, 2022, 31, 3, 157-159. [CrossRef]

- Searle, A.; Turnbull, J.; Lorimer, J. After the anthropause: Lockdown lessons for more-than-human geographies. Geographical Journal, 2021, 187, 1, 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Springer, S.;, Zieger, M.; Strzelecki, A. The rise of infodemiology and infoveillance during COVID-19 crisis. ONE HEALTH. [CrossRef]

-

2021 13, 100288. [CrossRef]

- Clark, EC.; Neumann, S.; Hopkins, S.; Kostopoulos, A.; Hagerman, L.; Dobbins, M. Changes to Public Health Surveillance Methods Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 2024, 10, e49185. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, BB.; Burgess, K.; Willis, C.; Gaston, KJ.. Monitoring public engagement with nature using Google Trends. People and Nature, 2022, 4, 5, 1216-1232. [CrossRef]

- Mavragani, A. Infodemiology and Infoveillance: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2020, 22, 4, e16206. [CrossRef]

- Kesenheimer JS.; Greitemeyer TA. “Lockdown” of materialism values and pro-Environmental behavior: Short-Term Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 11774. [CrossRef]

- Cooke SJ.; Soroye P.; Brooks JL.; Clarke J.; Jeanson AL.; Berberi A.; Piczak M.; et al. Ten considerations for conservation policymakers for the post-COVID-19 transition. Environmental Reviews, 2021, 29, 2, 111-118. [CrossRef]

- Schippers, MC.; Ioannidis, JPA.; Joffe, AR. Aggressive measures, rising inequalities, and mass formation during the COVID-19 crisis: An overview and proposed way forward. Frontiers in Public Health, 2022 10, 950965. [CrossRef]

- Golding, J.; Chmura, H. Lessons for conservation from the mistakes of the COVID-19 pandemic: The promise and peril of big data and new communication modalities. Conservation Science and Practice, 2024, 6, 3. [CrossRef]

- Heise, UK. Science, technology, and postmodernism. In: Connor S. (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Postmodernism. 2006 Published online by Cambridge University Press.

- Peters, RH. A critique for Ecology. Cambridge University Press, UK, 1991; pp. 1-366.

- Shrader-Frechette, KS.; McCay, ED. Method in Ecology. Cambridge University Press, UK, 1993; pp. 1-328.

- Hilborn, R; Mangel, M. The Ecological Detective. Confronting models with data. Princeton University Press, Jersey, USA, 1997; pp. 1-315.

- Schwartz, MW.; Glikman, JA.; Cook, CN. The COVID-19 pandemic: A learnable moment for conservation. Conservation Science and Practice, 2020 2, 8, e255. [CrossRef]

- Gertler P.; Martinez S.; Premand P.; Rawlings L.; Vermeersch C. Impact evaluation in practice. The World Bank, 2016.

- Rothbard, S.; Etheridge, JC.; Murray, EJ. A Tutorial on Applying the Difference-in-Differences Method to Health Data. Current Epidemiological Reports, 2024, 11, 85-95. [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, S.; Deschacht, N. Public Awareness of Nature and the Environment During the COVID-19 Crisis. Environmental & Resource Economics, 2020, 76, 4: 1149-1159. [CrossRef]

- Ladle, RJ.; Correia, RA.; Do, Y.; Joo, GJ.; Malhado, ACM. Proulx, R.; Roberge, JM.; Jepson, P. Conservation culturomics. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2016, 14, 5, 270-276. [CrossRef]

- Bocking, S. Nature on the Home Front: British Ecologists' Advocacy for Science and Conservation. Environment and History, 2012, 18, 2, 261-281. [CrossRef]

- Chandola, T.; Kumari, M.; Booker, CL.; Benzeval, M. The mental health impact of COVID-19 and lockdown-related stressors among adults in the UK. Psychological Medicine, 2022, 52, 12, 2997-3006. [CrossRef]

- Sayre, NF. The genesis, history, and limits of carrying capacity. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 2008, 98, 1: 120-134.

- Cosme, I.; Santos, R.; O'Neill, DW. Assessing the degrowth discourse: A review and analysis of academic degrowth policy proposals. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2017, 149: 321-334. [CrossRef]

- Troumbis, AY. The circularity entrapment of the 'Global Human Confinement Experiment' in conservation culturomics. Biological Conservation, 2021, 260, 109244. [CrossRef]

- Ladle, RJ.; Souza, CN.; Correia, RA. Conservation culturomics: Don't throw the baby out with the bathwater. Biological Conservation, 2021, 260, 109255. [CrossRef]

- Young, N.; Kadykalo, AN.; Beaudoin, C.; Hackenburg, DM.; Cooke SJ. Is the Anthropause a useful symbol and metaphor for raising environmental awareness and promoting reform? Environmental Conservation, 2021, 48, 4, 274-277.

- Hoffmann, L. Bressem, KK.;, Cittadino, J.; Rueger, C.; Suwalski, P.; Meinel, J.; Funken, S.; Busch, F. From Global Health to Global Warming: Tracing Climate Change Interest during the First Two Years of COVID-19 Using Google Trends Data from the United States. Environments, 2023, 10, 221, 10120221.

- Caetano, GHD.; Vardi, R.; Jaric, I.; Correia, RA.; Roll, U.; Veríssimo, D. Evaluating global interest in biodiversity and conservation. Conservation Biology, 2023, 37, 5, e14100. [CrossRef]

- Vijay, V.; Field, CR.; Gollnow, F.; Jones, KK. Using internet search data to understand information seeking behavior for health and conservation topics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Biological Conservation, 2021, 257, 109078. [CrossRef]

- Mohommad, A.; Pugacheva, E. Impact of COVID-19 on Attitudes to Climate Change and Support for Climate Policies. International Monetary Fund, WP/22/23, 2022, Available at: https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2022/English/wpiea2022023-print-pdf.ashx. [CrossRef]

- Soulé, ME. What is conservation biology? Bioscience, 1985, 35, 11, 727–734.

- Dahlstrom, MF. Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111, 13614–13620. [CrossRef]

- Kareiva, P.; Marvier, M. What is conservation science? BioScience, 2012, 62, 11, 962–969.

- Soulé, ME. The ‘new conservation’. Conservation Biology, 2013, 27, 5, 895–897.

- Zyoud, SH.; Zyoud, AH. Coronavirus disease-19 in environmental fields: a bibliometric and visualization mapping analysis. Environment Development and Sustainability, 2021, 23, 6, 8895-8923. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T. The structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Cooke, SJ.; Soroye, P.; Brooks, JL.; Clarke, J.; Jeanson, AL.; Berberi, A.; Piczak, ML.; et al. Ten considerations for conservation policymakers for the post-COVID-19 transition. Environmental Reviews, 2021, 29, 2, 111-118.

- Thurstan, RH.; Hockings, KJ.; Hedlund, JSU.; Bersacola, E.; Collins, C.; Early, R.; Ermiasi, Y.; et al. Envisioning a resilient future for biodiversity conservation in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. People and Nature, 2021, 3, 5, : 990-1013. [CrossRef]

- Golding, J.; Chmura, H. Lessons for conservation from the mistakes of the COVID-19 pandemic: The promise and peril of big data and new communication modalities. Conservation Science and Practice, 2024, 6, 3, e13090. [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being. 2005 Washington, DC, USA: Island Press.

- Dunlop, T.; Khojasteh, D.; Cohen-Shacham. E.; Glamore, W.; Haghani, M.; van den Bosch, M.; Rizzi. D.; et al. The evolution and future of research on Nature-based Solutions to address societal challenges. Communications Earth & Environment, 2024, 5, 1, 132. [CrossRef]

- Asafu-Adjaye, J.; Blomqvist, L.; Brand, S.; Brook, B.; DeFries, R.; Ellis, E.; et al. An Ecomodernist Manifesto. 2015 The Breakthrough Institute [www document]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281607422_An_Ecomodernist_Manifesto.

- Leach, M.; Mearns, R. Environmental change and policy. In: The Lie of the Land: Challenging received Wisdom on the African Environment, eds M Leach, R Mearns. London, UK, International African Institute. 1996, pp. 1–33.

- Shanahan, EA.; Jones, MD.; McBeth, MK. Policy narratives and policy processes. Policy Studies Journal, 2011, 39, 3, 535–561. [CrossRef]

- McCallum, ML.; Bury, GW. Google search patterns suggest declining interest in the environment. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2013, 22, 1355–1367. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, JR.; Zhou, H.; Shay, DK.; Neuzil, KM.; Fowlkes, AL.; Goss, CH. Monitoring Influenza Activity in the United States: A Comparison of Traditional Surveillance Systems with Google Flu Trends. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, 4, e18687.

- Myburgh, PH. Infodemiologists Beware: Recent Changes to the Google Health Trends API Result in Incomparable Data as of 1 January 2022. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022, 19, 22, 15396. [CrossRef]

- Troumbis, AY.; Iosifidis, S. A decade of Google Trends-based Conservation culturomics research: A critical evaluation of an evolving epistemology. Biological Conservation, 2020, 248, 108647.

- Ficetola, GF. Is interest toward the environment really declining? The complexity of analyzing trends using internet search data. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2014, 22, 2983–2988.

- Burivalova, Z.; Butler, RA.; Wilcove, DS. Analyzing Google search data to debunk myths about the public’s interest in conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and Environment, 2018, 16, 9, 509–514. [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Pischke, JS.; Schwandt, H. Poorly Measured Confounders are More Useful on the Left than on the Right. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 2019, 37, 2, 205-216.

- Rose, DC. Avoiding a post-truth world: embracing post-normal conservation. Conservation and Society, 2018, 16, 4, 518–524. [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G. Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environmental Communication, 2010, 4, 1, 70–81. [CrossRef]

- Brooke, C. Conservation and Adaptation to Climate Change. Conservation Biology, 2008, 22, 6, 1471-1476. [CrossRef]

- Wiens, JA.; Bachelet, D. Matching the Multiple Scales of Conservation with the Multiple Scales of Climate Change. Conservation Biology, 2010, 24, 1, 51-62. [CrossRef]

- Iwamura, T.; Guisan, A.; Wilson, KA.; Possingham, HP. How robust are global conservation priorities to climate change? Global Environmental Change – Juman and Policy Dimensions, 2013, 231, 5, 1277-1284.

- Kujala, H.; Moilanen, A.; Araújo, MB.; Cabeza, M. Conservation Planning with Uncertain Climate Change Projections. PLOS ONE, 2013, 8, 2, e53315. [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, PF.; Bull, JW.; Bicknell, JE.; Oakley, JL.; Brown, MH.; Bruford, MW.; Butchart, SHM.; et al. The positive impact of conservation action. Science, 2024, 384, 453. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Guo, Y.; Ye, T.; Gasparrini, A.; Tong, S.; Overcenco, A.; Urban, A. Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: a three-stage modelling study. Lancet Planetary Health, 2021, 5, e415-e425. [CrossRef]

- Visconti, G.; Young, K. The effect of different extreme weather events on attitudes toward climate change. PLoS ONE, 2024 19 5 e0300967. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Depiction of an idealized ‘Difference-in-Differences’ example graph. The lines in the graph illustrate the trends over time in outcome measures (ASVG descriptors) for two periods: the pre-pandemic control period (P = 0) and the pandemic impact period (P = 1). On the x-axis, time is represented in months, ranging from w = − 48 months (pre-COVID baseline) to w = 1 (Years 2016-2019) vs. w =1 to w = 48 months (Years 2020-2023). The vertical line marks the switch from pre-intervention to post-intervention periods. The slope of the extensions of the pre-pandemic trend of ASVGs corresponds to three hypotheses: red extension indicates no significant effect of the pandemic on the environmental awareness of citizens (for one or all descriptors); the blue dotted line suggests an increase in environmental awareness of citizens; and the orange dotted line suggests a decrease in environmental awareness of citizens. .

Figure 1.

Depiction of an idealized ‘Difference-in-Differences’ example graph. The lines in the graph illustrate the trends over time in outcome measures (ASVG descriptors) for two periods: the pre-pandemic control period (P = 0) and the pandemic impact period (P = 1). On the x-axis, time is represented in months, ranging from w = − 48 months (pre-COVID baseline) to w = 1 (Years 2016-2019) vs. w =1 to w = 48 months (Years 2020-2023). The vertical line marks the switch from pre-intervention to post-intervention periods. The slope of the extensions of the pre-pandemic trend of ASVGs corresponds to three hypotheses: red extension indicates no significant effect of the pandemic on the environmental awareness of citizens (for one or all descriptors); the blue dotted line suggests an increase in environmental awareness of citizens; and the orange dotted line suggests a decrease in environmental awareness of citizens. .

Figure 2.

Box-and-whiskers plots of the Absolute Google Search Volumes, representing UK public opinion interest in environmental, public health, and pandemic keywords (2004-2023). [A]: ASVGs for biodiversity, climate change, and sustainability; [B]: ASVGs for infectious diseases and pathogens, as proxies for the ‘emergent diseases’ keyword; [C]: ASVG for Covid-19. Symbolisms are presented in the legend table. .

Figure 2.

Box-and-whiskers plots of the Absolute Google Search Volumes, representing UK public opinion interest in environmental, public health, and pandemic keywords (2004-2023). [A]: ASVGs for biodiversity, climate change, and sustainability; [B]: ASVGs for infectious diseases and pathogens, as proxies for the ‘emergent diseases’ keyword; [C]: ASVG for Covid-19. Symbolisms are presented in the legend table. .

Figure 3.

AGSVs for Infectious diseases (A) and Pathogens (B) in the UK, January 1, 2004 – December 31, 2023. The table explains symbolisms. In

Figure 2A, numbered lines correspond to 1: SARS; 2: swine flu; 3: MERS (extending to 2Fig023); 4: Zika virus; 5: Covid-19 (extending to 2023); 6-7: Adenovirus hepatitis and monkeypox.

Figure 3.

AGSVs for Infectious diseases (A) and Pathogens (B) in the UK, January 1, 2004 – December 31, 2023. The table explains symbolisms. In

Figure 2A, numbered lines correspond to 1: SARS; 2: swine flu; 3: MERS (extending to 2Fig023); 4: Zika virus; 5: Covid-19 (extending to 2023); 6-7: Adenovirus hepatitis and monkeypox.

Figure 4.

A synoptic visualization of the UK public interest in the evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic. [A]: 4th-degree polynomial fit line of the AGSV Covid-19, weekly scale (smoothing after adjacent-averaging method, lag = 2); [B]: Gaussian deconvolution of the smoothed AGSV Covid-19 (red line) at a monthly scale; thin grey lines represent the hidden peaks of public interest; [C]: Mass of information (broadcast, print, and web news) flow in the UK, according to the daily records of The GDELT Project (period: January 1, 2020 – December 31, 2023).

Figure 4.

A synoptic visualization of the UK public interest in the evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic. [A]: 4th-degree polynomial fit line of the AGSV Covid-19, weekly scale (smoothing after adjacent-averaging method, lag = 2); [B]: Gaussian deconvolution of the smoothed AGSV Covid-19 (red line) at a monthly scale; thin grey lines represent the hidden peaks of public interest; [C]: Mass of information (broadcast, print, and web news) flow in the UK, according to the daily records of The GDELT Project (period: January 1, 2020 – December 31, 2023).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the Difference-in-Difference in Environment-related AGSVs before and after the COVID-19 outbreak. It covers 96 months, with the separator date (black line) being month 192 of the AGSVs data series starting January 2004 and ending December 2023. [A]: Biodiversity; [B]: Sustainability; [C1]: Climate change, including the outlier peaks on either side of the separator date; [C2]: Climate change; the outliers are replaced by the overall average of AGSV climate change 2004-2023, including the outliers. The symbolisms of lines and colors are presented in the legend of

Figure 2.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the Difference-in-Difference in Environment-related AGSVs before and after the COVID-19 outbreak. It covers 96 months, with the separator date (black line) being month 192 of the AGSVs data series starting January 2004 and ending December 2023. [A]: Biodiversity; [B]: Sustainability; [C1]: Climate change, including the outlier peaks on either side of the separator date; [C2]: Climate change; the outliers are replaced by the overall average of AGSV climate change 2004-2023, including the outliers. The symbolisms of lines and colors are presented in the legend of

Figure 2.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the distribution of the residuals of the 4th-degree polynomial model against theoretical percentiles. In addition to the visual check for normality, i.e., a fundamental assumption in regression analysis, it shows that the variance in the response variables, AGSVs ([A]: biodiversity; [B]: sustainability; [C]: climate change (outliers corrected), is not heterogeneous (percentiles 10-90%).

Figure 6.

Illustration of the distribution of the residuals of the 4th-degree polynomial model against theoretical percentiles. In addition to the visual check for normality, i.e., a fundamental assumption in regression analysis, it shows that the variance in the response variables, AGSVs ([A]: biodiversity; [B]: sustainability; [C]: climate change (outliers corrected), is not heterogeneous (percentiles 10-90%).

Table 1.

Summary statistics of the analysis of Environment-related AGSVs, the form of the 4th-degree polynomial fit line Y=β0+β1 Χ4+β2 Χ3+β3 Χ2+β4 Χ+ε, smoothing (lags per factor), the R2, and the significance of the ANOVA test.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of the analysis of Environment-related AGSVs, the form of the 4th-degree polynomial fit line Y=β0+β1 Χ4+β2 Χ3+β3 Χ2+β4 Χ+ε, smoothing (lags per factor), the R2, and the significance of the ANOVA test.

| AGSV factor smoothed (lag = 6), monthly scale |

4th-degree polynomial fit line |

| β0

|

β1

|

β2

|

β3

|

β4

|

R2

|

ANOVA |

| Covid-19 (weekly scale, lag =2) |

0 |

5.3E7 (3.3E6) |

7.3E5 (4.6E4) |

-3333.4 (216.1) |

5.05 (0.33) |

0.978 |

p<0.0001 |

| Pathogens |

3600 |

-84.7 (5.85) |

1.47 (0.13) |

-0.008 (9.35E-4) |

1.71E-5 (2.06E-6) |

0.964 |

p<0.0001 |

| Infectious diseases |

42500 |

1111.1 (22.6) |

14.1 (0.51) |

-0.073 (0,003) |

1.32E-4 (7,96E-6) |

0.973 |

p<0.0001 |

| Biodiversity |

5000 |

486.8(185.8) |

-7.576 (2.93) |

0.038 (0.015) |

-6.02Ε-5 (2.61Ε-5) |

0.986 |

p<0.0001 |

| Sustainability |

12500 |

1565.2 (424.9) |

-24.092 (6.701) |

0.119 (0.034) |

-1,85E-4 (5.98E-5) |

0.991 |

p<0.0001 |

| Climate change |

50000 |

4060.5 (3404.3) |

-78.795 (53.835) |

0.472 (0.280) |

-8.95E-4 (4.83E-4) |

0.947 |

p<0.0001 |

| Climate change (outliers corrected) |

65000 |

5524 (1521.3) |

-94.9 (24.06) |

0.517 (0.125) |

-9.04E-4 (2.16E-4) |

0.986 |

p<0.0001 |

Table 2.

Summary statistics of pairwise comparison of means of Environment-related AGSVs before and after the separator date. Each sample is 48 months long on either side of the separator date. Normality and outliers are controlled by the difference between the monthly values of each AGSV/descriptor. Normality is controlled with the Shapiro-Wilk test (ns: non-significant). The data presented are the sample's mean with standard error in parenthesis. t-value is accompanied by its significance (p1: one side; p2: two-sides).

Table 2.

Summary statistics of pairwise comparison of means of Environment-related AGSVs before and after the separator date. Each sample is 48 months long on either side of the separator date. Normality and outliers are controlled by the difference between the monthly values of each AGSV/descriptor. Normality is controlled with the Shapiro-Wilk test (ns: non-significant). The data presented are the sample's mean with standard error in parenthesis. t-value is accompanied by its significance (p1: one side; p2: two-sides).

| AGSV descriptor smoothed (lag = 6), monthly scale |

Paired samples mean comparison |

| Difference pairwise |

Normality S-W |

Mean ‘before’ |

Mean ‘after’ |

t (p1; p2) |

| Biodiversity |

-2963.7 (418,1) |

0.228 |

4937.7 (185.7) |

7901.4 (335,3) |

-7.088 (<.001; <.001) |

| Sustainability |

-9496.6 (1075.7) |

0.301 |

12562.6 (358.6) |

22059.2 (954.4) |

-8.828 (<.001; <.001) |

| Climate change |

-19594.6 (4792) |

0.02 ns

|

47406.8 (3102.8) |

67001.4 (3072.9) |

-4.089 (<.001; <.001) |

| Climate change (outliers corrected) |

-18879.2 (2648.5) |

0.327 |

45129.8 (2068.2) |

64009.1 (2075.1) |

-7.128 (<.001; <.001) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).