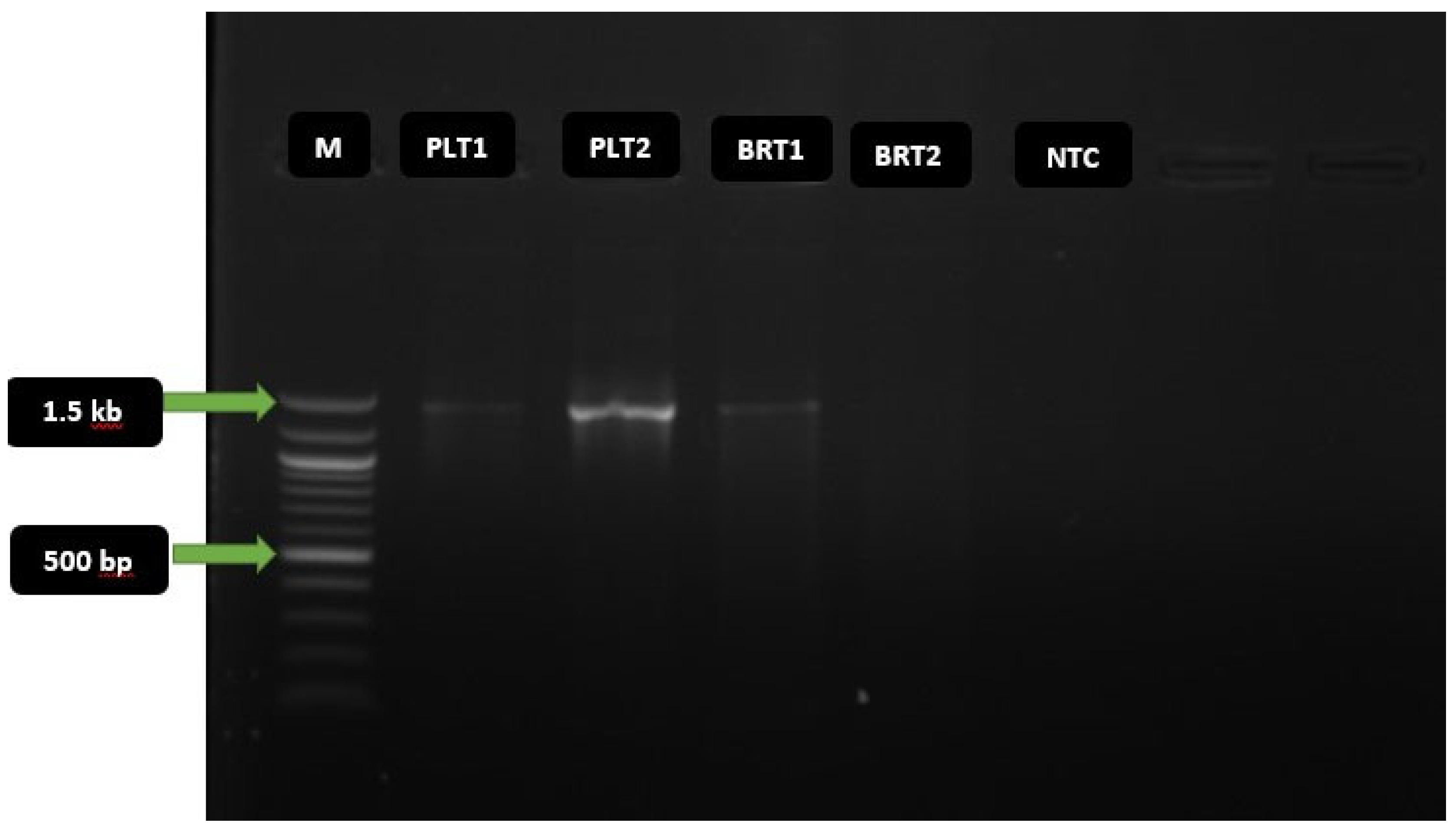

1. Introduction

Cellulose is the most common renewable biopolymer (homopolysaccharide) produced in the biosphere (C

6H

10O

5) and is essentially made up of glucose monomers joined together by β (1-4) glycosidic linkages. It is produced by microorganisms, animals, and plants [

1,

2]. Bacterial cellulose hydrogel (BCH) is the three-dimensional (3-D) network structure of naturally occurring bacterial cellulose that can absorb and retain significant volumes of water. The purification processes for plant-based cellulose such as logging, debarking, chipping, mechanical pulping, screening, chemical pulping, and bleaching consume a lot of energy and are not environmentally friendly [

3]. By contrast, just a few contaminants, such as cells and/or medium components, are present in bacterial cellulose (BC) that is formed during fermentation. There is a growing interest in developing fully bio-based cellulosic polymer with excellent properties, such as tensile strength and Young's modulus. BCH has good mechanical properties, positioning it as a choice bioresource for reinforcing agents in composite materials [

4]. BCH is devoid of contaminating substances including lignin, hemicellulose, pectin, wax, and other challenging-to-remove plant components [

5].

BCH is suited for the creation of artificial skin and wound dressings due to the biocompatibility of its nanofibers and their high water-holding capacity [

3]. The biomaterial has been commercialized as high-end products for health, food, high-strength papers, audio speakers, filtration membranes, wound dressing materials, artificial skin, artificial blood vessels, and other biomedical devices due to desirable properties like its three-dimensional nanomeric structures, unique physical, mechanical, and thermal properties, and its higher purity [

6].

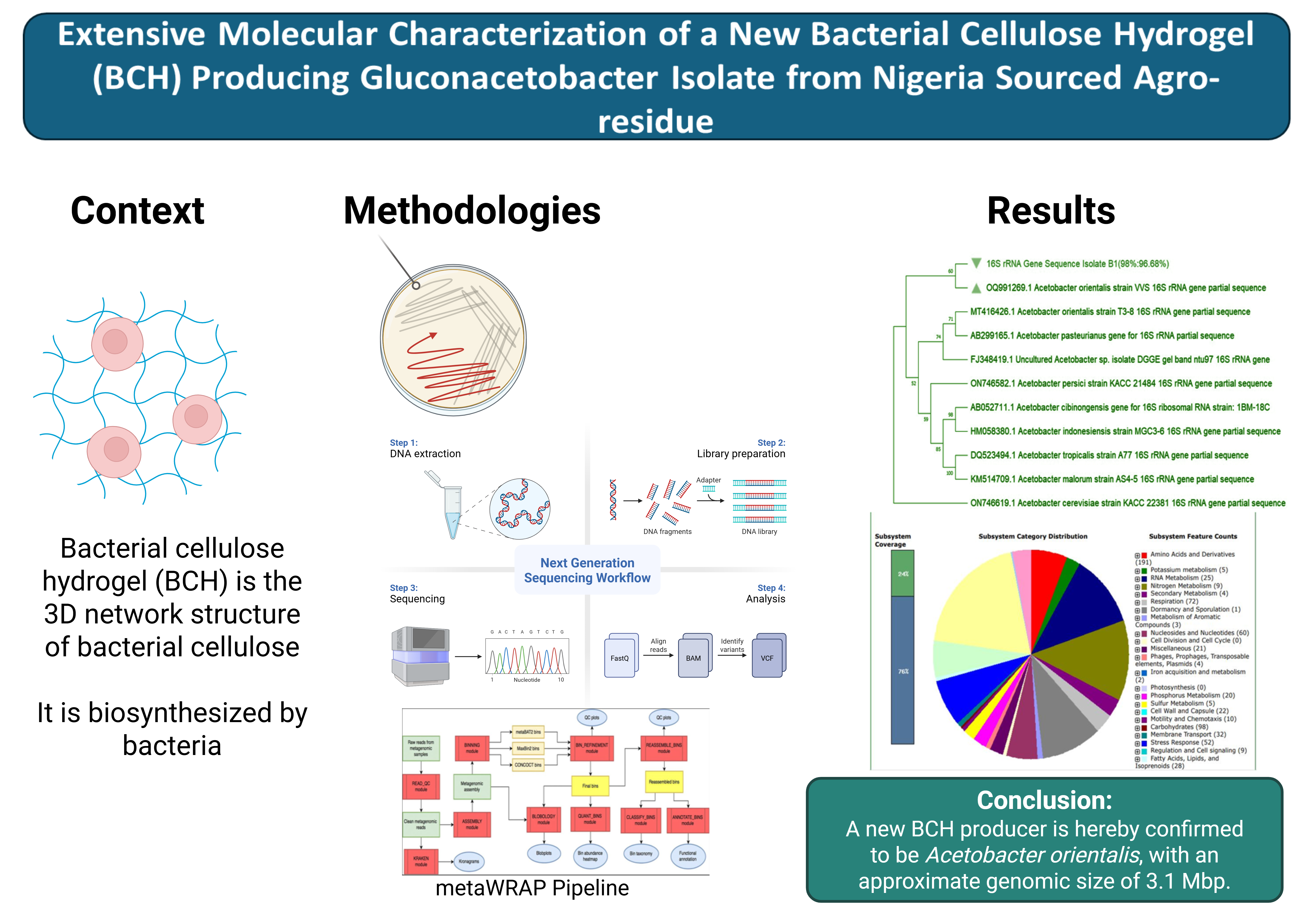

Gluconacetobacter species use a multi-step metabolic route involving different enzymes, catalytic complexes, and regulatory proteins at each stage for cellulose production [

7]. The biosynthetic pathway, assuming glucose is the carbon source, consists of four major enzymatic steps: (i) glucose phosphorylation by glucokinase; (ii) isomerization of glucose-6-phosphate (Glc-6-P) to glucose-1-phosphate (Glc-1-P) by phosphoglucomutase; (iii) synthesis of UDP-glucose (UDPGlc) by UDPG pyrophosphorylase (UGPase); and (iv) cellulose synthase reaction. In all

Gluconacetobacter species and other BCH-producing bacterial species, the bacterial cellulose synthesis (

bcs) operon encodes the biosynthesis of cellulose [

8]. This operon has four subunits (

bcsA, bcsB, bcsC, and

bcsD) which are necessary for full BCH biosynthesis. The catalytic subunit of cellulose synthase is encoded by the first gene of the bcsABCD operon,

bcsA. The second messenger that initiates the cellulose synthesis process, cyclic diguanylate monophosphate (c-di-GMP), is bound by the regulatory subunit of cellulose synthase, which is encoded by the second gene

, bcsB. [

7,

9].

Figure 1.

Bacterial cellulose hydrogel biosynthesis pathway (metabolite denoted by blue and grey arrows, metabolic pathways as yellow boxes, and enzymes involved in the respective reactions denoted in green). Figure generated using Biorender.com.

Figure 1.

Bacterial cellulose hydrogel biosynthesis pathway (metabolite denoted by blue and grey arrows, metabolic pathways as yellow boxes, and enzymes involved in the respective reactions denoted in green). Figure generated using Biorender.com.

Acetic acid bacteria (AAB) are a group of microorganisms that belong to the family

Acetobacteraceae of the class

Alphaproteobacteria and made up of 14 genera. Due to its capacity to produce comparatively high amounts of BCH in liquid culture from a variety of carbon and nitrogen sources,

Gluconacetobacter xylinus (previously known as

Acetobacter xylinum) is one of the most researched species [

11]. Despite extensive studies on bacterial BCH producers, none has been isolated or identified here in Nigeria. Moreover, the

Acetobacter orientalis species has not been reported or documented in literature to produce BCH. Therefore, the search for other species of

Acetobacter (

Gluconacetobacter) that is able to produce BCH has become imperative. Additionally, the complete genome sequencing analysis of local strains of

Gluconacetobacter [

11], as well as characterization of subunit genes in the cellulose-synthesizing operon (

acs operon) will serve as genomic data that provide a viable platform that can be used to understand and modify the phenotype of the bacterial cellulose synthase (

bcs) genes to further improve BCH production.

Molecular identification techniques have revolutionized bacterial identification studies, which enable the rapid and accurate identification of certain species. Numerous uses exist for DNA sequencing methods, including the identification of bacterial species and the tracking of the transmission of genes encoding antibiotic resistance. Examples of these uses include Sanger sequencing, NGS, and third-generation sequencing [

12]. While there are many methods available in modern bacterial taxonomy to ascertain both genotypic and phenotypic traits, whole genome DNA-DNA hybridization and

16S rRNA gene sequencing are essential [

13]. One method used to ascertain an organism's entire DNA sequence is called Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS). The method uses high-throughput sequencing to generate a lot of data in a short amount of time. DNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis are the steps involved in WGS [

14]. The identification and characterization of bacteria has been transformed by WGS. This technique has several significant applications, one of which is that it makes it easier to identify the genes that code for certain essential metabolic proteins, including bacterial cellulose synthase [

12].

To identify the most similar biological sequences, the BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) takes a query sequence - either a DNA or protein sequence - provided by the researcher and compares it to a library of biological sequences on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database [

15]. BLAST is an algorithm or piece of software used for pairwise sequence (nucleotide or protein) alignment [

16]. The extraction and interpretation of high-quality metagenomic bins are greatly enhanced by MetaWRAP, an intuitive modular pipeline that automates the core tasks in metagenomics analysis. Modern software use metaWRAP to manage metagenomic data processing, which begins with raw sequence reads and ends with metagenomic bins and their analysis [

17,

18,

19].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Retrieval and culturing of the BCH-producing isolate on Hestrin-Schrann (HS) media

The

Acetobacter orientalis Zaria-B1 isolate was retrieved from a preliminary study which involved isolation from banana peel agro-residue using the method described by [

20]. This was then followed by subsequent screening for BCH production using the HS broth and agar media, as well as further characterization of the BCH-producing isolate through microscopic examination, morphological, and biochemical characterizations. The HS media had the following components: 2% (w/v) Glucose, 0.5% (w/v) Yeast extract, 0.5% (w/v) Peptone, 0.27% (w/v) Na2HPO4 (Disodium hydrogen phosphate), 0.15% (w/v) Citric acid, and 1.8% (w/v) agar. 10 mL of the screened isolate was inoculated into 90 mL of the broth media. The mixture was then incubated on a shaker incubator at 30 °C for 48 hrs at 150 rpm. The resulting culture was used for extraction of genomic DNA. For the agar plates, 100 µL preculture of the isolate was aliquoted into each of the prepared sterile agar plates and spread out using a sterile inoculating loop spreader. The plates were then incubated at 30 °C for 48 hours and were observed for colony growth. Colonies from each plate were randomly picked and used for genomic DNA extraction

2.2. Genomic DNA extraction from broth and agar cultures

Prior to DNA extraction, 200 µL of the broth culture from each Erlenmeyer flask was dispensed into 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes. For samples used for bacterial DNA extraction from agar plates, scoops of bacterial smear (colony) were picked randomly from the agar plates into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes containing 200 µL of DNA Elution Buffer using P100 pipette tips. The mixture was vortexed, and the genomic DNA was extracted using the Zymo Research Quick-DNATM Miniprep Plus Kit (USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted genomic DNAs were quantified on a Nanodrop spectrophotometer, and their concentrations and purities (A260/A280) were determined.

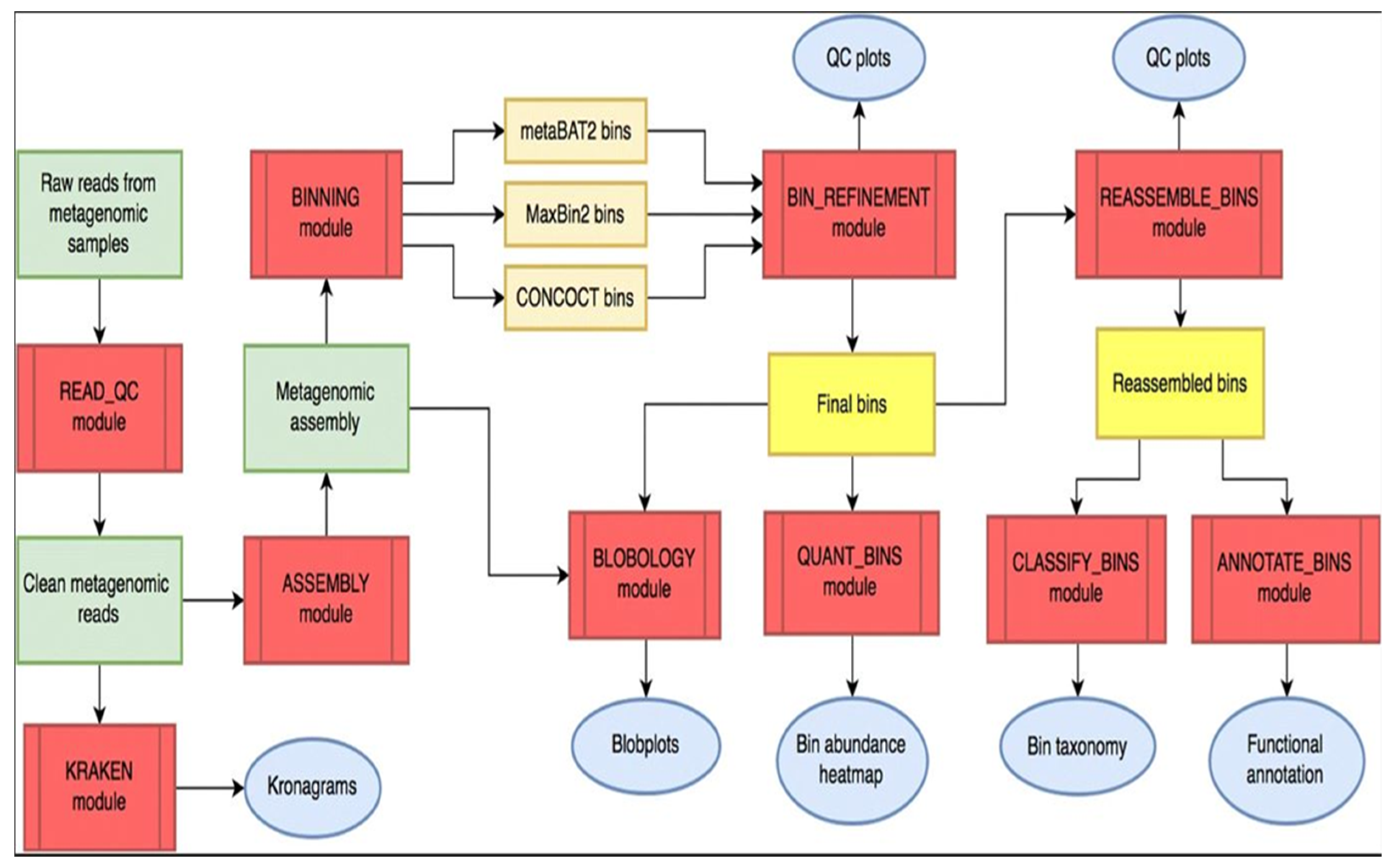

2.3. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification of the 16S rRNA gene

The bacterial species was identified by PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene from the genomic DNA using generic forward 48A (5'-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3') and reverse 48B (5'-TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') primers. The PCR mix was prepared with a total reaction volume of 25 µL, comprising 9.5 µL of nuclease-free water (NFW), 10 µM of each primer, 12.5 µL of Quick-load 2× Mastermix, and 1 µL of template DNA. A negative control reaction contained NFW in place of template DNA. The PCR cycling conditions are: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 minutes, and 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 48 °C for 1 minute, extension at 68 °C for 1 minute, and final extension step at 68 °C for 10 minutes.

The PCR amplicons from the experiments were analyzed on 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide visualization dye to ascertain positive PCR amplicons. Gel from the electrophoresis was visualized in a GelDoc system under the UV (Ultraviolet) light.

2.4. Sequencing of positive PCR amplicon

The amplified PCR amplicon with the most distinct clear band, was sequenced by the Dye-terminator method with an AB1 XL3500 Genetic Analyzer according to the service provider’s instruction (Inqaba Biotec West Africa, IBWA, Ibadan). This summarily includes preparation of the BigDye mix, preparation of the sequencing reaction, thermal cycling, precipitation reaction (DNA sequencing cleanup), and capillary electrophoresis (actual sequencing).

2.5. Bioinformatics analysis of sequencing Result

The AB1 data of the sequenced amplicons were generated. This data contained the chromatograms of the individual sequences alongside some ambiguous nucleotide codes. The ambiguous codes were edited and replaced with standard nucleotide codes using BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor v7.2.5. Edited reverse sequence was reverse complemented using the reverse complement function. Thereafter, edited forward and reverse sequences were then aligned together using the program Pairwise Alignment function. Finally, a consensus nucleotide sequence representative of the two aligned sequences was generated with the program’s Create Consensus Sequence algorithm.

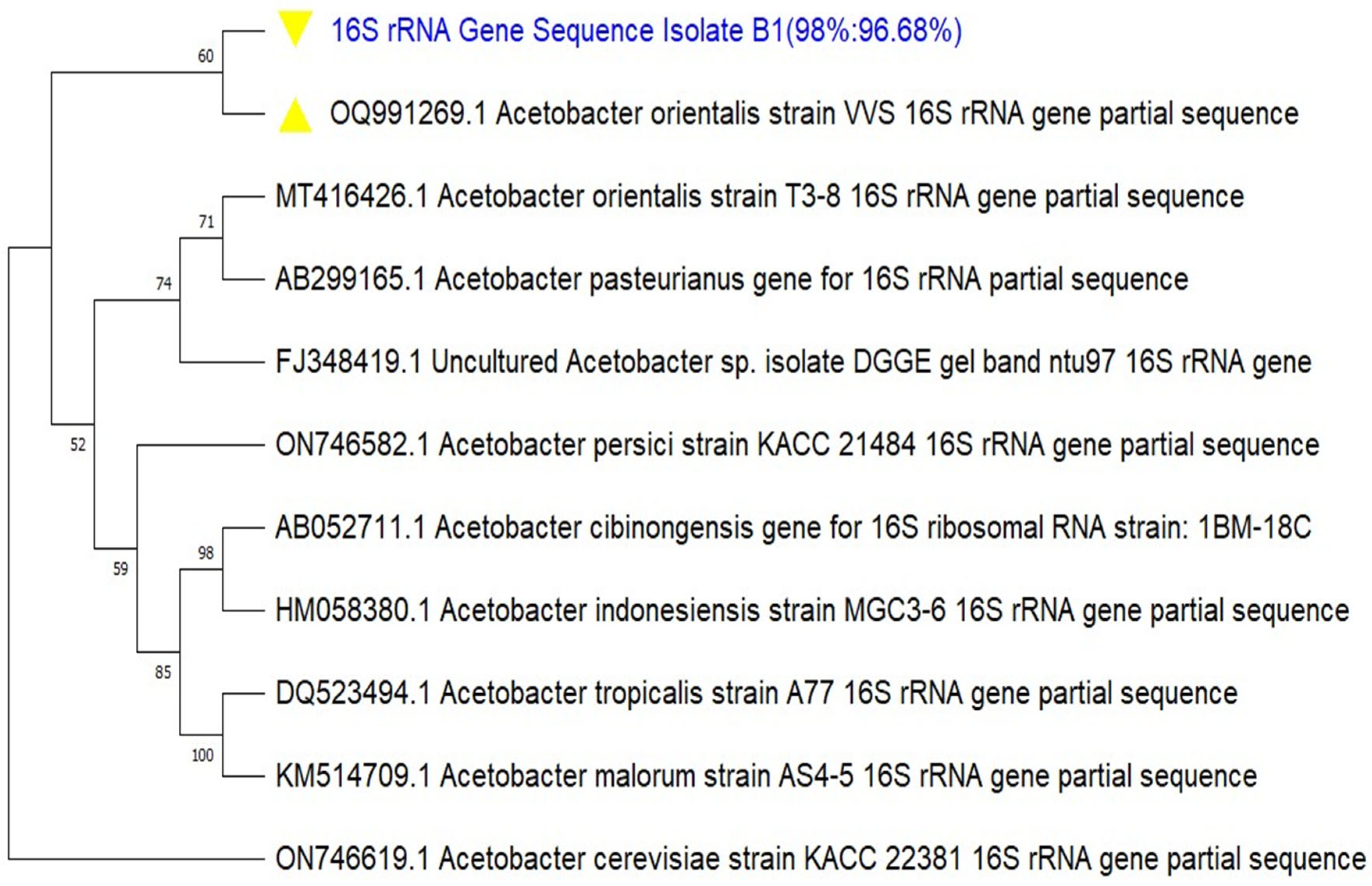

For molecular identification of the isolate, the generated consensus sequence was subjected to the NCBI nucleotide BLAST, and ten (10) sequences from the BLAST hits (output), were selected based on the highest query cover and percentage identity indexes, as well as the lowest E-values, and downloaded in FASTA format. The 10 sequences with the query consensus sequence were subjected to ClustalW multiple sequence alignment (MSA) using MEGA11 software. A phylogenetic tree was constructed to determine the most recent and closely related ancestry of the isolate. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model. A bootstrap value of 1000 was set for the phylogeny. The phylogenetic tree was further edited using the Fig Tree software v1.4.4. The consensus sequence of the 16S rRNA gene of the characterized isolate was deposited in the NCBI GenBank Database and was assigned accession number.

2.6. Whole-Genome sequencing of the isolate

The whole-genome sequencing of the BCH producing isolate was carried out by Inqaba Biotec. Library preparation for the whole-genome sequencing was achieved as follows: Genomic DNA was fragmented using an enzymatic approach (NEB Ultra II FS kit). Resulting DNA fragments were size selected (200 – 700bp), using AMPure XP beads, the fragments were end repaired and Illumina-specific adapter sequences were ligated to each fragment. Each sample was individually indexed, and a second size selection step was performed. Samples were then quantified using a fluorometric method. The samples were diluted to a standard concentration (4 nM) and then sequenced on Illumina NextSeq500 platform, using a NextSeq mid out kit (300 cycle), following a standard protocol as described by the manufacturer. 2x150 bp paired end read data was produced for each sample. The library preparation method used can be found at:

https://international.neb.com/protocols/2017/10/25/protocol-for-fs-dna-library-prep-kit-e7805-e6177-with-inputs-less-than-or-equal-to-100-ng

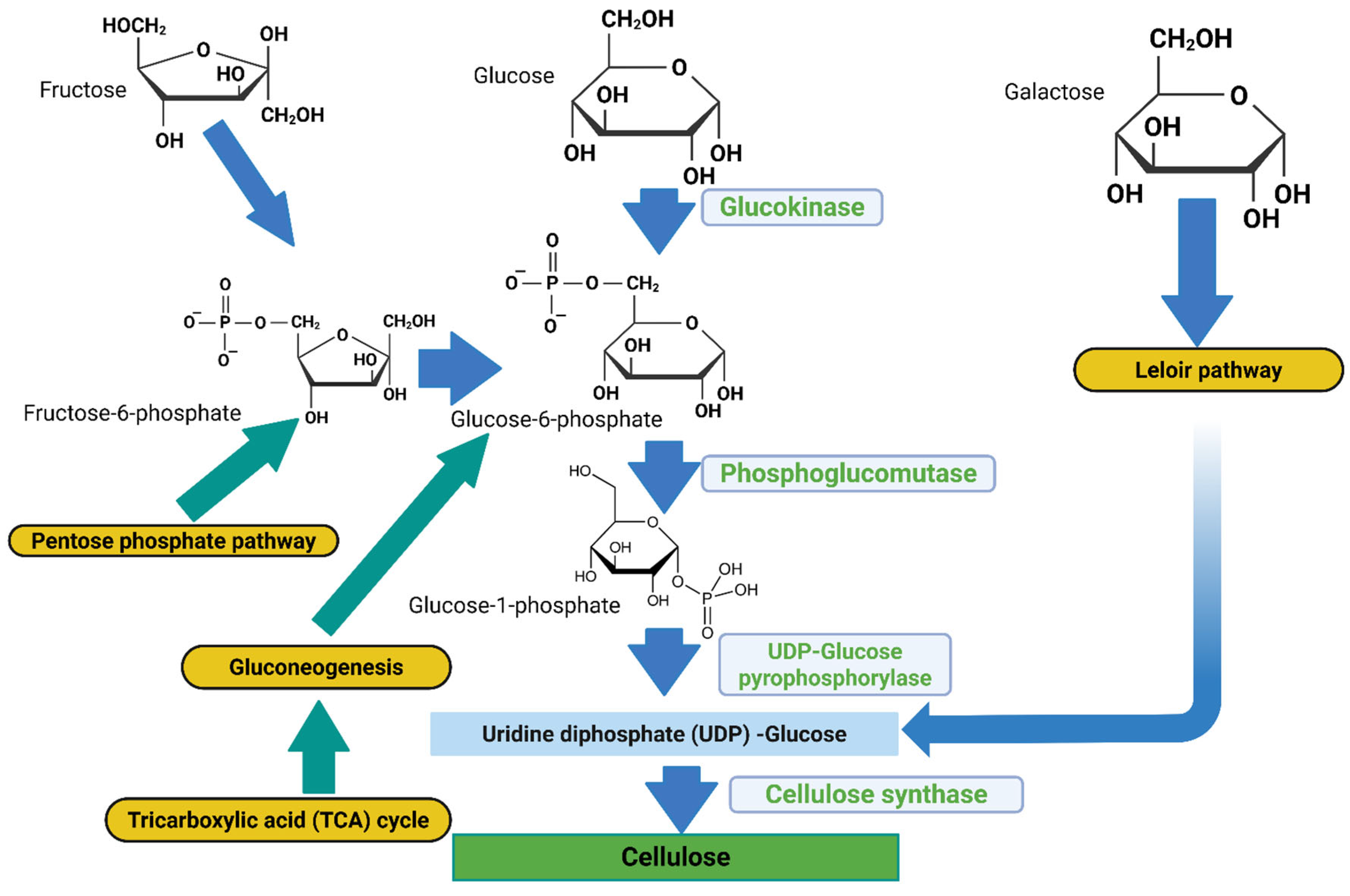

2.7. Data analysis of the Whole-Genome Sequence (WGS) Reads using the metaWRAP pipeline modules

MetaWRAP is an easy-to-use modular pipeline that automates the core tasks in metagenomics analysis and is an open-source program available at

https://github.com/bxlab/metaWRAP [

18]. After downloading the metagenomics reads of the NGS, the metaWRAP-Read_qc module was run to trim the reads and remove human contamination, using the “bmtagger hg38”. The metagenomes (reads) were then assembled with the metaWRAP-Assembly module, using the “metaSPADES or MegaHIT” program (software). This was executed following concatenation of the sample reads. To know the taxonomic composition of communities (reads), the “Kraken” module was run on both the reads as well as the assembly. After assembly, the co-assembly was binned with three different algorithms (CONCOCT, MaxBin and MetaBAT) with the metaWRAP-Binning module [

17].

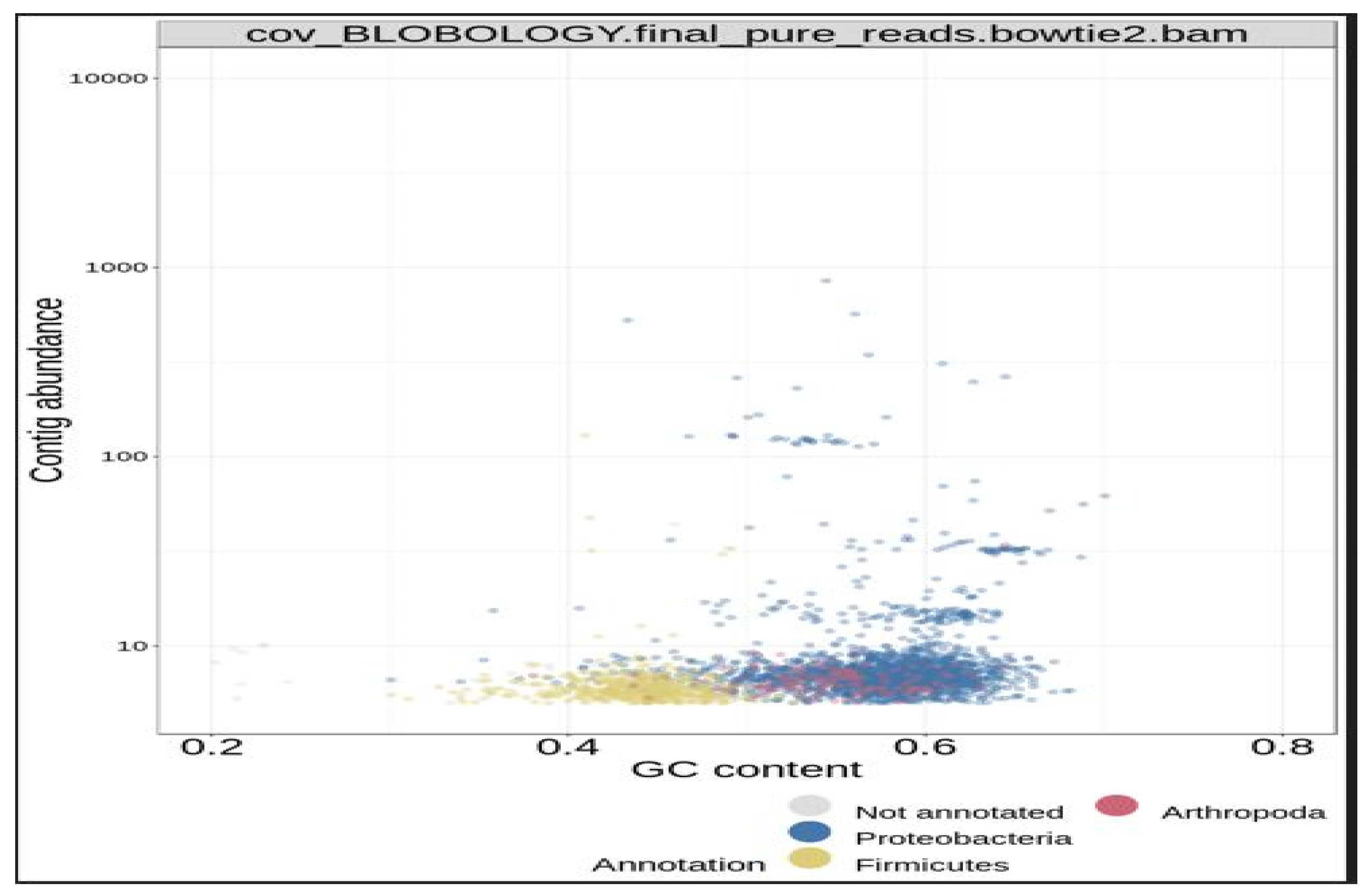

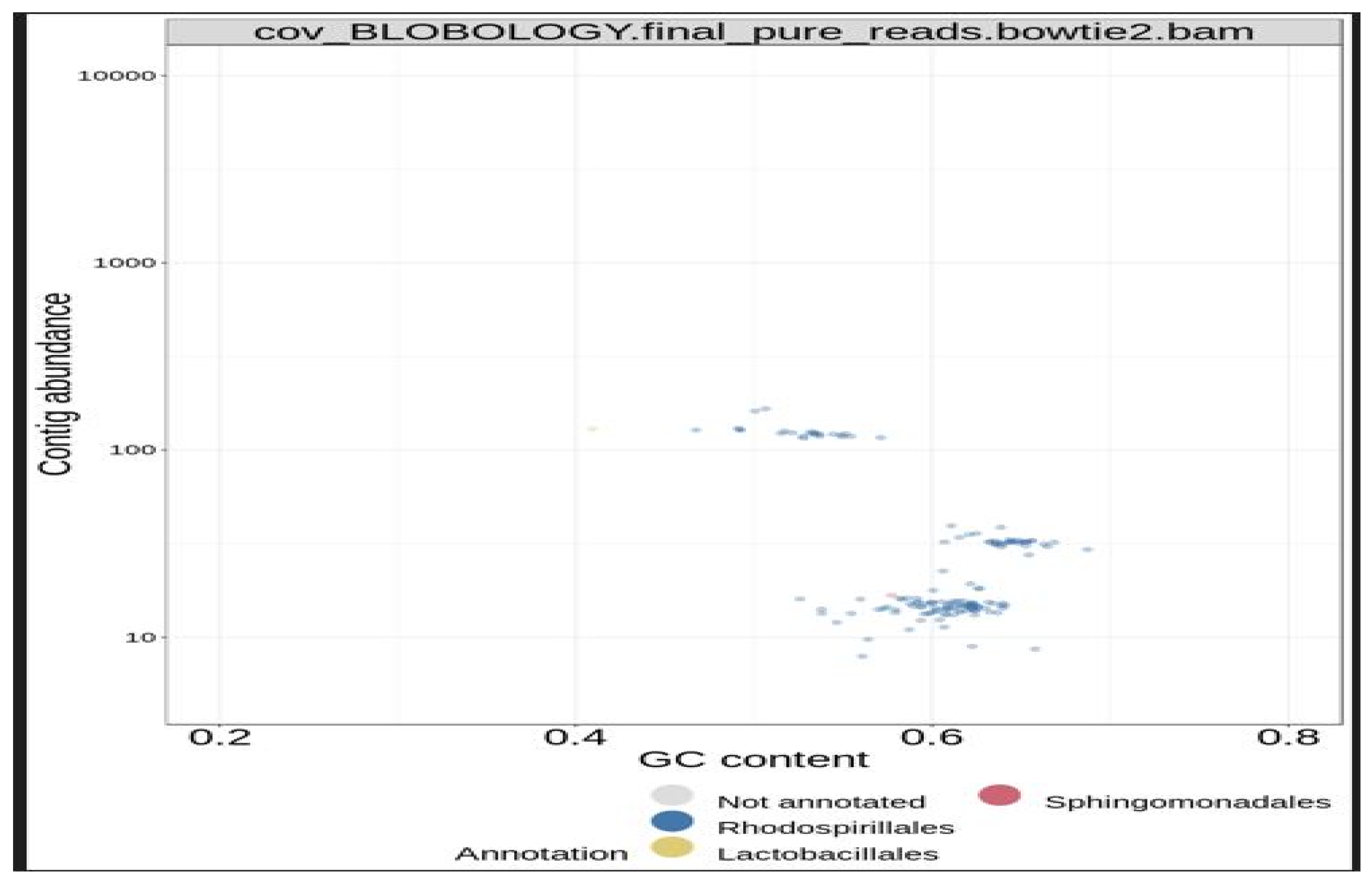

Next, the concoct, maxbin, and the metabat bin sets were consolidated into a single, stronger bin set, with the metaWRAP Bin-Refinement module. The CheckM database was employed for this module. By default, the minimum completion of 70%, and maximum contamination of 5%, were deployed by the program. The community (consolidated bin set) and the extracted bins were visualized with the Blobology module. This module was used to project the entire assembly onto a GC vs Abundance plane and annotate them with taxonomy and bin information. Thereafter, the abundances of the draft genomes (bins) across the sample were determined with the Quant module. Next, the consolidated bin set was re-assembled with the Reassemble-bins module.

The Reassemble-bins module collects reads belonging to each bin and then reassemble them separately with a "permissive" and a "strict" algorithm. Only the bins that improved through reassembly were altered in the final set. Thereafter, the taxonomy of each bin was inferred with the Classify-bins module using the Taxator-tk program [

21]. For this module, the NCBI_nt and NCBI_tax databases were required. The Classify_bins module used Taxator-tk to accurately assign taxonomy to each contig and then consolidated the results to estimate the taxonomy of the whole bin.

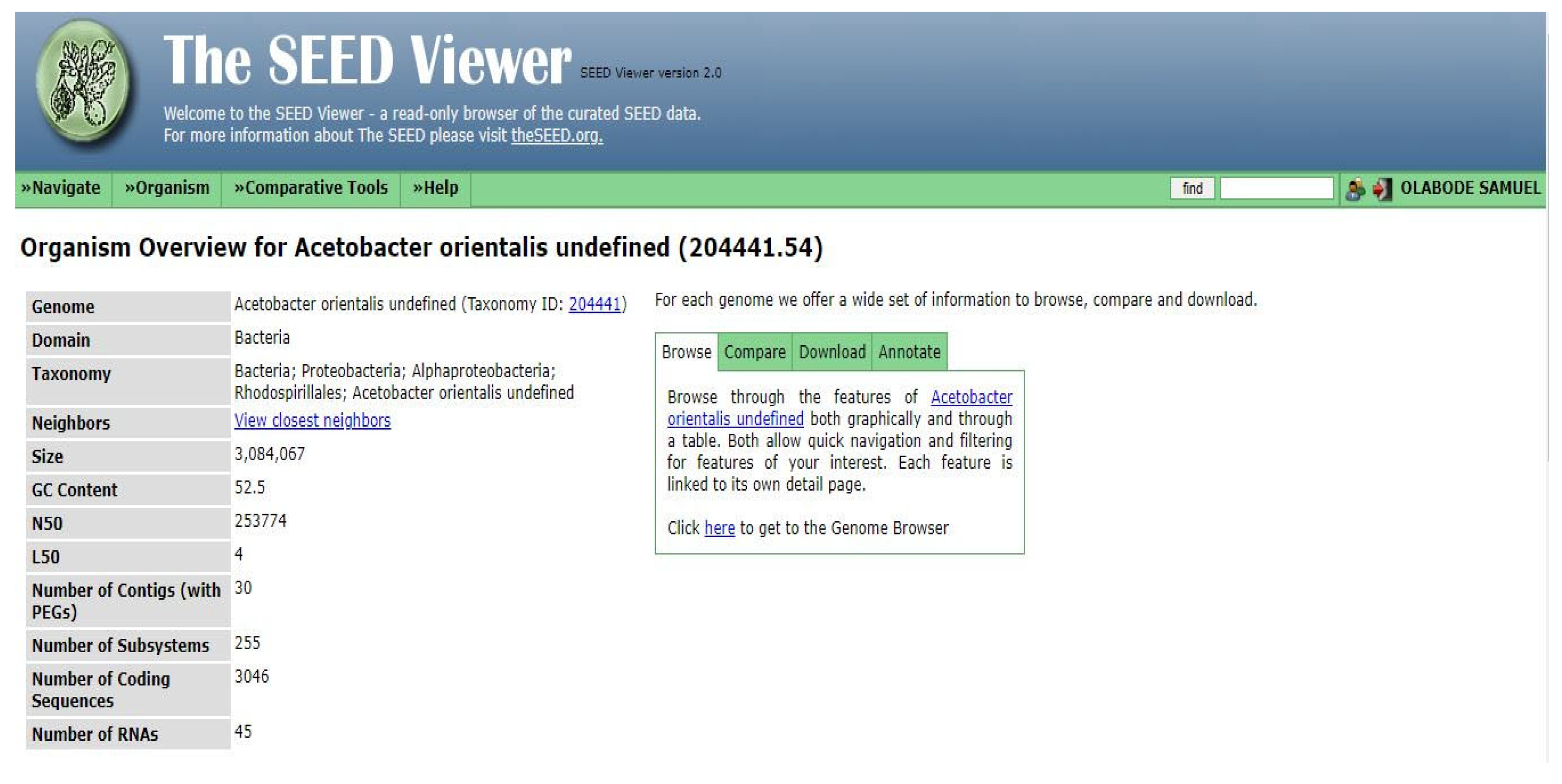

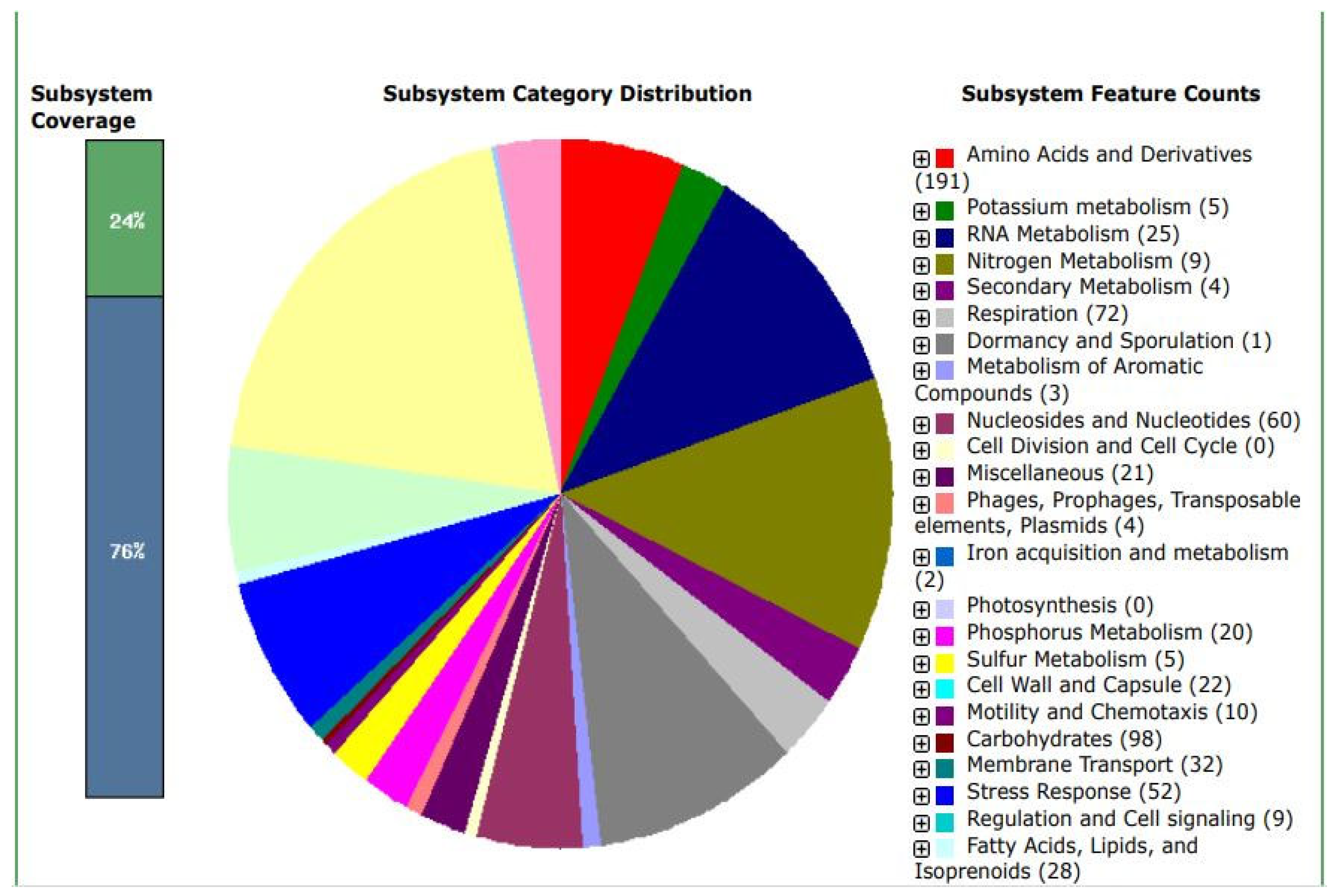

No doubt the success and accuracy of the predictions would rely heavily on the query cover and percentage sequence identity indexes of the existing database. Finally, the generated bin (bins) was functionally annotated with the Annotate-bins module using the RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology) online tool [

17,

18,

21]. The annotated bin was then visualized on the SEED viewer online tool

Figure 2.

Overall Workflow of metaWRAP Pipeline. Modules (red); metagenomics data (green); intermediate (orange) and final bin sets (yellow), and data reports and figures (blue) (Adapted from

https://github.com/bxlab/metaWRAP).

Figure 2.

Overall Workflow of metaWRAP Pipeline. Modules (red); metagenomics data (green); intermediate (orange) and final bin sets (yellow), and data reports and figures (blue) (Adapted from

https://github.com/bxlab/metaWRAP).

4. Discussion

The ultrapure and nanofibrillar structure of BCH differentiates it from plant cellulose. BCH is well known for its strength, flexibility and high water holding capacity reaching up to ~90% of its weight. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that BCH attracts significant attention, and numerous approaches have been pursued for research and development of the biomaterial. Synthesis of BCH is a multistep process, involving many enzymes and proteins [

23]. In BCH synthesis, glucose monomers linked by β-1,4-glucan chains are simultaneously polymerized by cellulose synthase, a membrane bound enzyme, which utilizes UDP-glucose as substrate. According to [

24], genes for bacterial cellulose hydrogel (BCH) biosynthesis are localized in an operon (the

bcs operon) in the

Gluconacetobacter species. Bacterial cellulose is chemically the same in its primary composition as cellulose produced by other organisms (higher plants, algae), but the degree of polymerization and crystallinity as well as other physical properties are unique to each organism [

12].

In modern bacterial taxonomy, a range of techniques to determine both phenotypic and genotypic characteristics are available, but whole genome DNA-DNA hybridization and

16S rRNA gene sequencing play a central role. The overall 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity between the type strains and the type species of the 10 genera of acetic acid bacteria (AAB) ranges from 92.1 to 99.0 %, the latter found between

Asaia and

Swaminathania [

12].

Molecular characterization of microorganisms has become necessary to complement other preliminary characterizations (such as microscopic, morphological, and biochemical) which are not sensitive enough to determine the species and strains of target organisms. In this study, molecular techniques were used to characterize a new BCH producing isolate, identified as

Acetobacter orientalis, via PCR amplification of bacterial

16S rRNA gene and sequencing. The findings from this study are similar to several other studies that have reported the characterization of different species of the

Acetobacteraceae family, using similar techniques. [

24] isolated and characterized a bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) producer from rotten fruits in Malaysia as

Gluconacetobacter xylinus; the species

Acetobacter orientalis was isolated from Indonesian flowers, fruits and fermented foods and characterized as

orientalis species [

25]. Similarly, [

26] and [

27] also isolated

Acetobacter tropicalis from fermented juice of mango, capable of producing vinegar in Burkina Faso, and a cellulolytic and ligninolytic bacterium

Acetobacter orientalis XJC-C from a marine soft coral in China, respectively, and characterized same. All these studies employed PCR amplification of the bacterial

16S rRNA gene, sequencing and construction of phylogenetic trees to ascertain the genus and species of the organisms. In these studies, the amplified

16S rRNA gene amplicon had nucleotide sizes ranging from 1.3 -1.5 kbp.

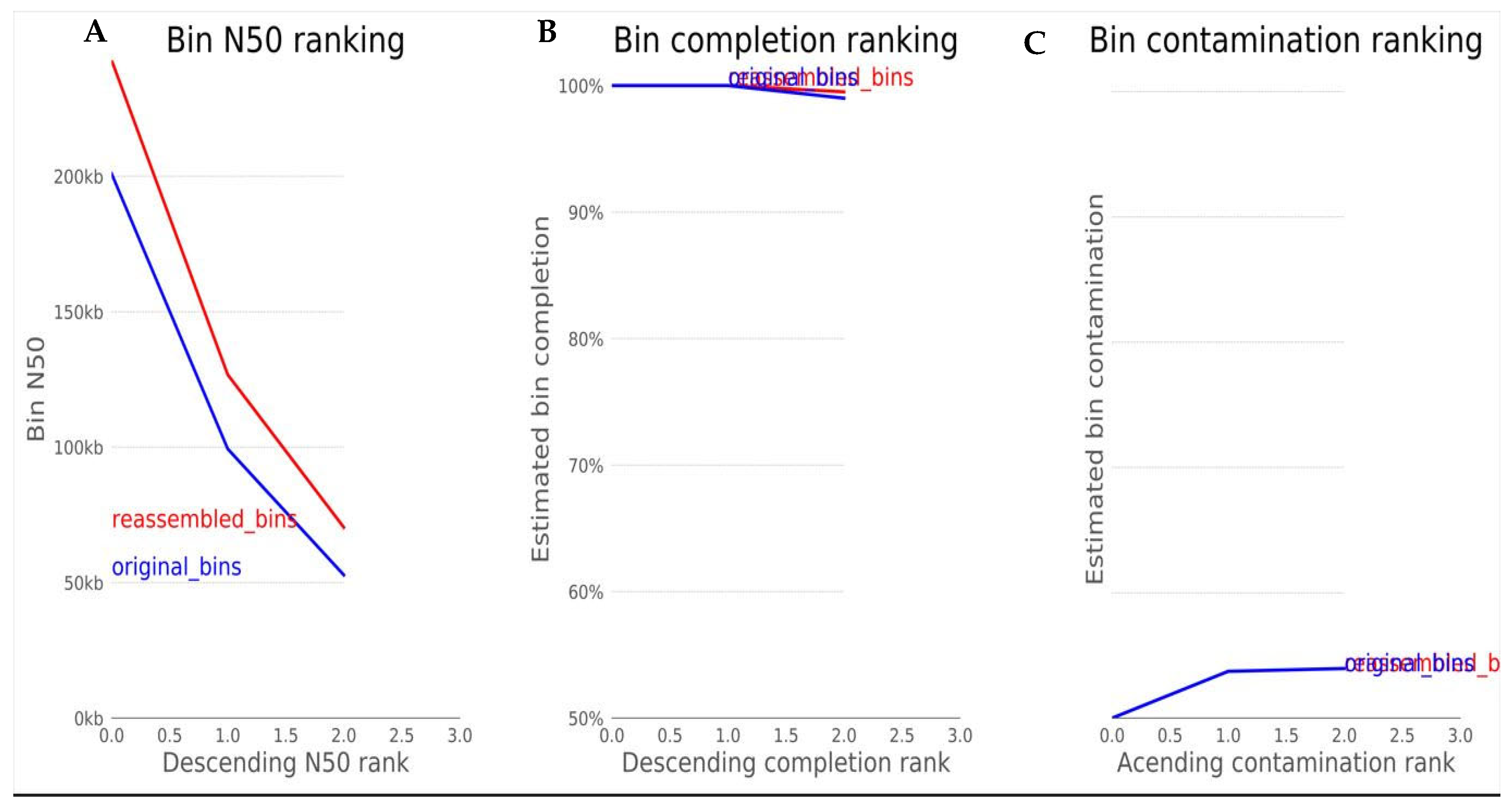

The N50 is a statistical index that defines assembly quality in terms of contiguity. It can be thought of as the point of half of the mass of the distribution; the number of bases from all contigs longer than the N50 will be close to the number of bases from all contigs shorter than the N50. While N50 corresponds to the sequence length in base pairs, L50 represents the number of sequences. Since contigs are ordered according to their length when calculating N50, we can say that L50 is simply the rank of the contig that gives us the N50 length [

21]. Two additional parameters that are used to assess the qualities of a metagenomics bin are completion and contamination. From

Figure 5, the estimated completion of the bin is approximately 100%, while the contamination was found to be 0.7%. Completion refers to the level of coverage of the population genome during assembly and reassembly, while contamination is the amount of sequence that does not belong to this population from another genome [

21]. In the metaWRAP reassembly module, the expected minimum completion is 50-70%, while the maximum contamination is 5-10%. These two metrics are usually estimated by counting universal single-copy genes within each bin. The percentage of expected single-copy genes that are found within a bin is interpreted as its completion, while the contamination is calculated from the percentage of single-copy genes that are found in duplicate [

21]. Based on the 4 parameters discussed, the metaWRAP analysis of the metagenome was accurately and successfully carried out.

Findings from the annotated genome of the isolate Zaria-B1 correspond to the works of [

23], who characterized the whole-genome of

Acetobacter orientalis strain FAN1 and obtained a total genomic size of 3,041,114 bp; 3,563 protein-encoding genes (PEGs); GC content of 52.34%; total of 70 RNAs (15 rRNAs and 55 tRNAs). However, their strain was reported to be involved in the fermentation of yoghurt and production of lactobionic acid, rather than BCH. This confirms that this species has not been reported to be involved in the production of BCH. The genomic size obtained in this study is slightly different from the results obtained by [

11], who reported from the annotated genome of

Gluconacetobacter xylinus CGMCC 2955 a total genomic size of 3,563,314 bp, 3,193 protein-encoding genes (PEGs), GC content of 63.29%, 117 non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), 45 ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs). However, the

Gluconacetobacter xylinus was identified as a BCH producer, which is one of the species of

Gluconacetobacter, that has been reported to produce BCH. Similarly, the work of [

14] which characterized the whole-genome of Komagataeibacter sp. strain CGMCC 17276 and found a somewhat different genomic size of 3,983,026 bp; 4,107 protein-encoding genes (PEGs); a GC content of 62.21%, total number of RNAs being 72 (57 tRNAs and 15 rRNAs). Furthermore, [

8] isolated the acetic acid bacterium

Acetobacter pasteurianus 386B from cocoa bean heap in Ghana, which was reported to be involved in the fermentation of cocoa bean and carried out 454 Pyrosequencing of the genome of the isolate, and the sequenced genome was annotated with the GenDB software v2.2. Based on the annotation, the acetic acid bacterium was found to have a genomic size of 2,818,679 bp; a total of 7 plasmids; 118 number of contigs; a GC content of 52.19%; 2,595 number of protein-encoding sequences (PEGs), 5 rRNAs, and 57 tRNAs.

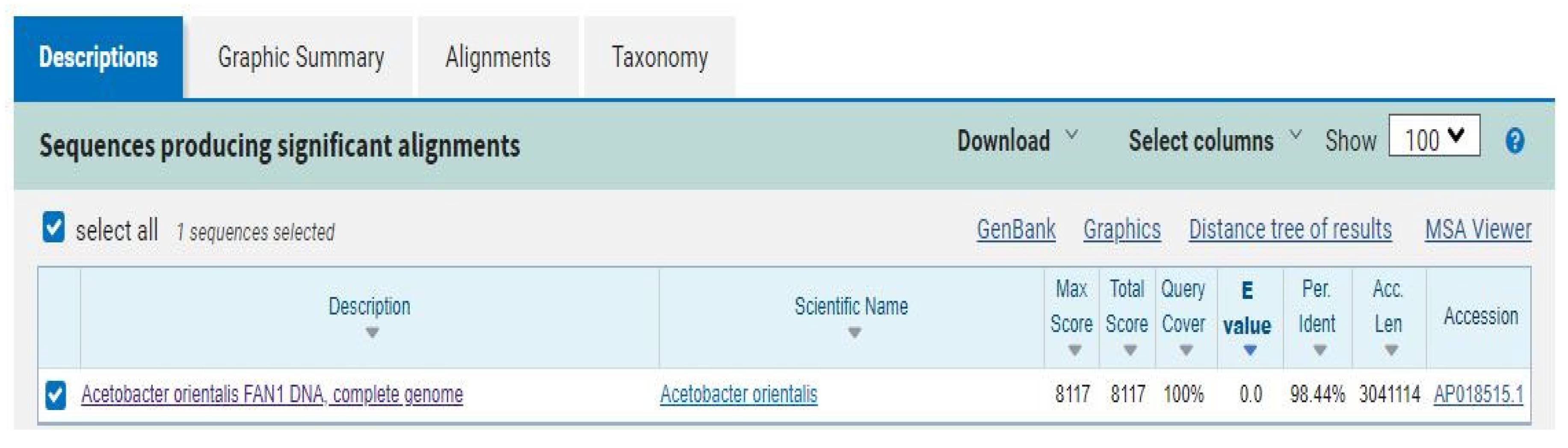

Figure 11 shows the NCBI nucleotide BLAST output for the cellulose synthase catalytic gene retrieved from the annotated genome of the isolate. This BLAST was necessary as the metaWRAP pipeline program could only classify the reassembled bin to the Order level of taxonomy. As a result, and based on the developer’s recommendation, manually looking at marker genes of the target organism of interest (such as the cellulose synthase gene, being the most conserved gene for all BCH producers), can result in much more specific taxonomy assignment. The BLAST result returned only one hit, which corresponded to the

Acetobacter orientalis strain FAN1 cellulose synthase gene, with a query cover of 100% and percentage identity of 98.44%. Based on this result, and the taxonomy assigned to the isolate by the NCBI GenBank database, the BCH producer isolate was confirmed to be

Acetobacter orientalis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O.B. and Y.K.E.I.; methodology, S.C.O.; software, S.C.O.; validation, S.C.O., J.L., B.Y.L., and I.Z.W.; formal analysis, S.C.O. and R.B.M.; investigation, E.O.B.; resources, E.O.B. and Y.K.E.I.; data curation, S.C.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.O.; writing—review and editing, E.O.B. and Y.K.E.I.; visualization, S.C.O.; supervision, E.O.B., Y.K.E.I., A.A.S., M.N.S., A.B.S., M.T.T. and M.H.S.; project administration, S.C.O.; funding acquisition, E.O.B. and Y.K.E.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.