1. Introduction

In recent years, the global beverage market has seen a significant rise in the demand for functional and fermented drinks that combine nutritional value, probiotic benefits, and appealing sensory characteristics. Interest in non-dairy, fermented functional beverages has grown steadily as consumers seek probiotic/functional products outside the dairy sector. Cereal- and pseudocereal-based substrates (including malt wort) provide carbohydrates, free amino acids and micronutrients that support lactic acid bacteria (LAB) growth and lactic acid fermentation [

1,

2]. During lactic acid fermentation LAB can produce stable, non-alcoholic beverages with improved shelf stability and modified flavour and bioactive profiles.

The improved shelf stability is due to LAB ability to produce bacteriocins and other antimicrobial compounds that inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria. The health benefits of consuming lactic acid fermented beverages include increased antioxidant activity through the production of bioactive compounds, such as phenolics and flavonoids. Moreover, LAB-fermented drinks can play a role in managing metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. The level of LAB should be 10

6 CFU/mL/g or more to exhibit the probiotic or nutraceutical functional properties [

3].

Despite their technological promise, LAB-fermented cereal beverages may suffer from limited aroma complexity and pronounced acidity that reduce consumer acceptance [

4]. To overcome sensory limitations and at the same time increase antioxidant and antimicrobial potential, researchers have investigated the addition of botanical ingredients (fruit fractions, extracts, essential oils) to fermented matrices. Essential oils are complex mixtures of volatiles (terpenes, aldehydes, phenolics) that can act both as flavouring agents and as sources of bioactive compounds with antioxidant and antimicrobial activities; however, because essential oils may also inhibit LAB at higher concentrations, their selection and dosage must be tailored to preserve fermentation performance [

5,

6].

Rosehip (Rosa canina L) oil is distinguished by its rich content of essential fatty acids, antioxidants, and vitamins, which have been extensively documented for their skin health benefits. However, the application of rosehip oil extends beyond topical uses, suggesting potential internal health benefits that could be leveraged in the development of functional beverages. The rosehip seed contains valuable phytochemicals such as phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and ascorbic acid. Furthermore, the rosehip-seed oil is rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, linoleic acid, linolenic acid, and phytosterols, mainly β-sitosterol. This provides an opportunity to enhance the nutritional profile of beverages but also to improve their oxidative stability and shelf life [7-9].

Lemongrass (

Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil is rich in citral (geranial and neral), which imparts its characteristic lemony aroma and flavor, making it particularly appealing for flavoring and scenting purposes in the food and beverage industry. Beyond its sensory attributes, lemongrass oil exhibits significant antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties, attributed to its diverse phytochemical composition. These health-promoting qualities align with the growing consumer interest in beverages that not only refresh but also contribute to overall well-being [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Eucalyptus

(Eucalyptus globulus) essential oil is known for its high content of eucalyptol (1,8-cineole), which accounts for its antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic properties. This compound is primarily responsible for the oil's characteristic aroma and its therapeutic effects. The chemical composition can vary depending on the eucalyptus species, but other significant components may include α-pinene, limonene, and globulol, contributing to its respiratory benefits, pain relief, and ability to fight infections. Eucalyptus essential oil's antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties make it a candidate for use in functional foods, potentially as a natural preservative or flavoring agent that could also confer health benefits. Its primary component, eucalyptol, may contribute to respiratory health and immune support when ingested in very small, safe quantities within food products. However, due to its potency and potential toxicity if improperly used, its application in functional foods requires careful formulation and adherence to safety guidelines [

14,

15,

16].

Although the combination between lactic acid fermentation of wort with low-level addition of essential oil offers a route to develop sensorially attractive and functionally enriched non- alcoholic beverages, there is a scarce data for such beverages in the scientific literature. In the works of Trendafilova et al. [

4] and Goranov et al. [

17], was investigated production of lactic acid wort-based beverage with mint essential oil in static and dynamic conditions, respectively. Goranov et al. [

18] also investigated the effect of raspberry seed oil on lactic acid fermentation of wort. However, there is no data about the production of lactic acid wort-based beverages with addition of rosehip, lemongrass, and eucalyptus oils.

Therefore, this study aims to produce lactic acid fermented wort-based beverages supplemented with rosehip, lemongrass, and eucalyptus oils and to evaluate: (1) fermentation kinetics (pH drop and residual extract), (2) LAB viability, (3) total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity, and (4) sensory acceptance. We hypothesise that carefully dosed additions of these botanicals will contribute measurable antioxidant and aroma benefits, and avoid undesirable inhibition of LAB while improving overall beverage acceptability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials, Media, and Reagents

2.1.1. Raw Materials

The strain used in this study was Lacticaseibacillus casei spp. rhamnosus Oly, isolated from spontaneously fermented yoghurt from Romania. Pilsen, Vienna, and Caramel Munich II malts were purchased from Bestmalt, Germany. Oils from rosehip, lemongrass, and eucalyptus were produced by Bulgarian rose Plc, Bulgaria.

2.1.2. Media

MRS Broth Composition (g/L): peptone from casein - 10; yeast extract - 4; meat extract - 8; glucose - 20; K2HPO4 - 2; sodium acetate - 5; diammonium citrate - 2; MgSO4 - 0.2; MnSO4 - 0.04; Tween 80 - 1 mL/L; pH = 6.5. Sterilization – 15 minutes at 118°C. The medium was used for cultivation of Lc. rhamnosus Oly at 37±1 °C for 24 hours.

LAPTg10 Agar Composition (g/L): peptone - 15; yeast extract - 10; tryptone - 10; glucose – 10; Tween 80 – 1 mL/L; agar – 15; pH = 6.6-6.8. Sterilization - 20 minutes at 121°C. The medium was used for the determination of the number of viable lactobacilli cells.

2.1.3. Reagents

Gallic acid, caffeic acid, quercetin, ABTS (2,2′-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt), neocuproine, and Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid) were purchased by Sigma Aldrich, USA. Hydrochloric acid was purchased by Merck, Germany. All the other reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2. Wort Production

A 4.5 kg malt mixture of 60% Pilsen, 20% Vienna, and 20% Caramel Munich II malts was milled using a hand disc mill (Corona, Germany) and mixed with pre-heated water in a ratio of 1:5 in a 20 L laboratory scale brewery (Braumeister, Germany). Mashing was conducted by increasing the temperature by 1°C/min and by maintaining rests at the following temperatures: 30 min at 50°C and 60 min at 77°C. Lautering and boiling were also conducted in the same Braumeister. Wort was boiled approximately 30 minutes without hop addition. After hot trub removal, the wort was autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 minutes for preserving it until experiments. It was filtered aseptically and used for lactic acid fermentation. The wort extract was 13.0±0.2 % w/w) and the pH was 5.00±0.05.

2.3. Fermentation

Oils from rosehip, lemongrass, and eucalyptus were added in a concentration of 0.01% (v/v), 0.02% (v/v), and 0.03% (v/v) to 200 ml of wort. Fermentation was carried out in plastic bottles at a constant temperature of 25±1°C with 2% (v/v) lactic acid bacteria suspension. Lactic acid bacteria were pre-inoculated in MRS broth and incubated at 37±1°C for 24 hours to obtain initial concentration of 107 cells/mL. Fermentation duration was 48 hours. Wort without oils addition was fermented at the same conditions and was used as a control sample.

2.4. Analytical Procedures

2.4.1. Fermentation Parameters

The extracts of wort and lactic acid wort-based beverages were measured by means of a densitometer Anton Paar DMA 35 (Anton Paar, Austria) and the pH was measured with Bante PHS-3BW benchtop pH meter (Bante, China). The enumeration of viable lactic acid bacteria was made by preparing appropriate 10-fold dilutions, pour plating in LAPTg10 agar, and incubating for 48-72 hours at 37 ±1°C until the appearance of countable single lactic acid bacteria colonies. Fermentation parameters were monitored daily.

2.4.2. Phenolic Compounds Content and Antioxidant Activity of the Beverages Produced

The wort and lactic acid wort-based beverages were diluted with methanol in ratio 1:4 and 1:9 for analyzing phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity, respectively. After a stay of 30 minutes and they were filtered using Whattman No. 1 filter paper. The content of phenolic compounds (total phenolic compounds, phenolic acids, and flavonoids) was determined by the modified Glories method on a Shimadzu UV-VIS1800 spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan) according to Shopska et al. [

19]. The antioxidant activity by the ABTS method and by the CUPRAC method were measured on the abovementioned spectrophotometer according to Shopska et al. [

19].

2.4.3. Sensory Analysis

A sensory evaluation of the beverages was carried out by a trained, 6-member tasting panel, consisting of 4 male and 2 females. The panel consisted of members of different age groups (aged 21–60). Tastings were performed in an appropriate room. Samples were poured into a clean transparent glass. All samples were served under a number and every sample was tested in triplicate. Evaluators were offered flat mineral water between the samples, together with plane white bread. Tastings were conducted with cold (4 °C) beverage. The samples were evaluated by their taste and aroma using descriptive analysis and ranking method (methods 13.10 and 13.11) [

20]. The scoring of each sensory attribute was conducted on a ten-point intensity scale, where 1 point means “extremely low” and 10 points mean “extremely strong”.

2.4.4. Statistical Analysis

The results of all the analyses were expressed as the mean values ± standard deviation of three replicates using Microsoft Excel 2016.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of oil Additions on the Fermentation Parameters

The effect of the addition of rosehip, lemongrass, and eucalyptus oils on the fermentation was investigated by measuring the extract, the pH, and the viable lactic acid bacteria concentration at the beginning (0th h) and at the end (48th h) of fermentation. The results were compared to a control without any oil addition and are presented in

Table 1. Overall, the extract consumption by LAB ranged between 0.1 °P and 0.2 °P, which is consistent with the limited availability of fermentable sugars in the wort used. Glucose, fructose, and sucrose are the primary carbohydrates metabolized by LAB [

21], but according to Ivanov et al. [

22], the wort prepared by this mashing method contains only about 7% glucose and less than 1% fructose, explaining the low overall extract reduction observed. The addition of 0.03% lemongrass oil significantly inhibited fermentation, as indicated by the lowest pH drop (from 4.95 to 4.45) and limited extract consumption. In the other variants, the pH drop ranged from 1.0 to 1.2 units, suggesting active lactic acid production. The number of viable LAB cells increased by approximately two orders of magnitude in the control, while oil-supplemented samples exhibited lower growth rates. Even at the lowest concentration (0.01%), essential oils reduced LAB proliferation, resulting in increases of only 0.4–1.0 log units. Increasing the concentration of rosehip and lemongrass oils further decreased cell viability, whereas eucalyptus oil had no significant effect on fermentation.

The observed inhibitory effects, particularly of lemongrass oil, are likely related to its high citral content, known to disrupt bacterial membrane integrity and proton gradients [

23]. Despite these effects, all beverages can still be classified as functional, as the final LAB counts exceeded 10⁷ CFU/mL, which meets the generally accepted threshold for probiotic functionality in fermented beverages.

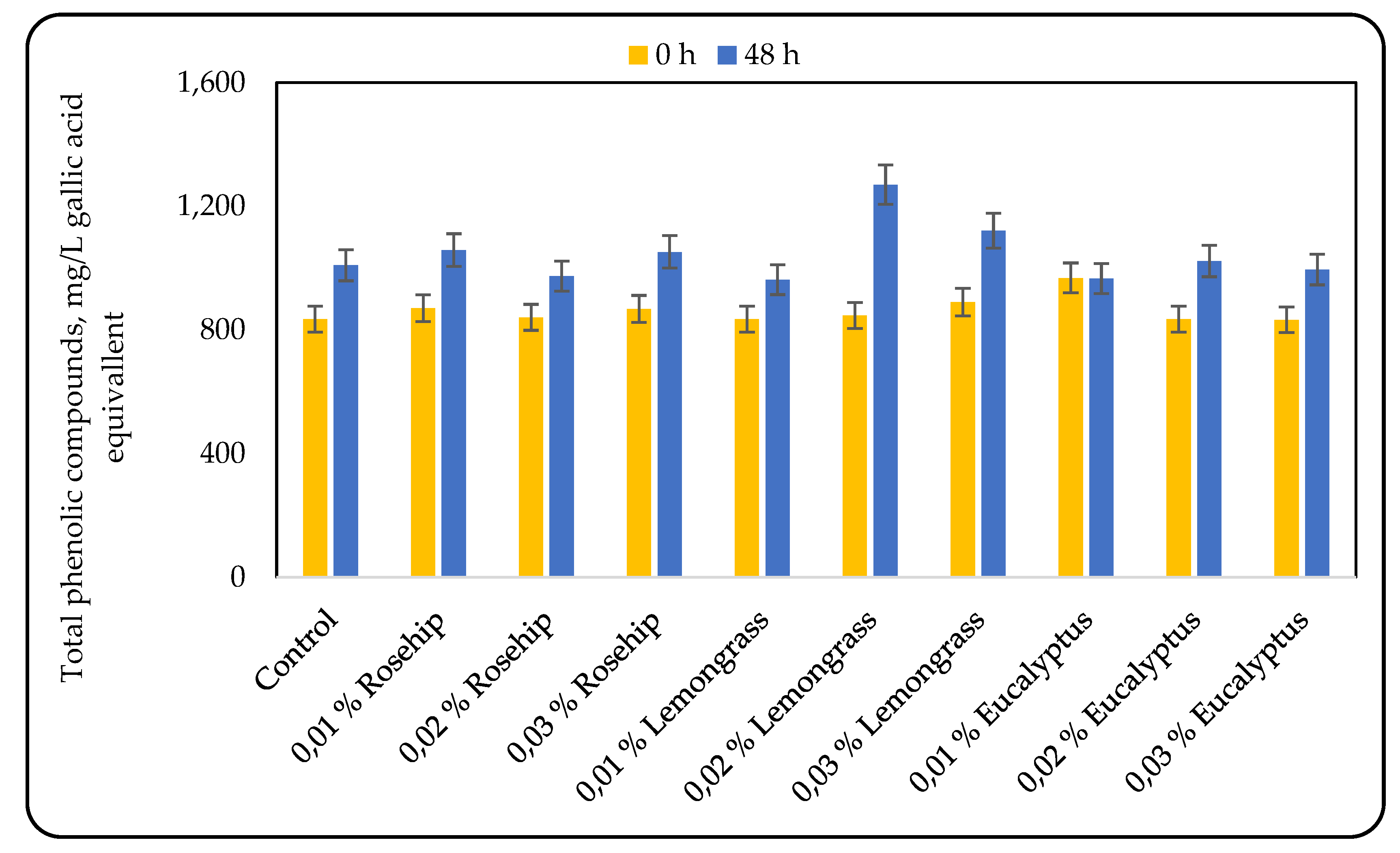

3.2. Effect of Oil Addition on the Phenolic Compounds Content

Phenolic compounds have received considerable attention due to their antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities, which potentially have beneficial implications in human health [

24]. The results for the total phenolic compounds, phenolic acids, and flavonoids, measured by the modified Glories method are presented on

Figure 1,

Figure 2, and

Figure 3, respectively. Overall, the concentration of total phenolic compounds (TPC) increased during lactic acid fermentation by 16–50%, depending on the essential oil added. The lowest increase (16%) was observed in the beverage containing 0.02% rosehip oil, whereas the highest (50%) occurred with 0.02% lemongrass oil. Interestingly, the addition of 0.01% eucalyptus oil resulted in no significant change in TPC.

The observed increase in phenolic content during lactic acid fermentation is consistent with previous reports, for example in fig fruit juice fermented by lactic acid bacteria [

25]. Such increases are commonly attributed to the release of bound phenolics, bioconversion of complex phenolics into simpler forms, or microbial synthesis of new phenolic derivatives by lactic acid bacteria [

26]. However, in the present study, no clear correlation between oil concentration and TPC was found. For instance, the increase in total phenolic compounds during fermentation with rosehip oil was similar at 0.01% and 0.03% addition levels. The beverage containing 0.02% lemongrass oil exhibited the highest TPC both at the end of fermentation and in terms of percent increase. For eucalyptus oil, the beverage with 0.02% addition showed the highest TPC, whereas 0.01% resulted in the lowest. In summary, 0.01% and 0.03% rosehip oil, 0.02% and 0.03% lemongrass oil, and 0.02% eucalyptus oil all yielded final phenolic concentrations equal to or higher than the control (

Figure 1).

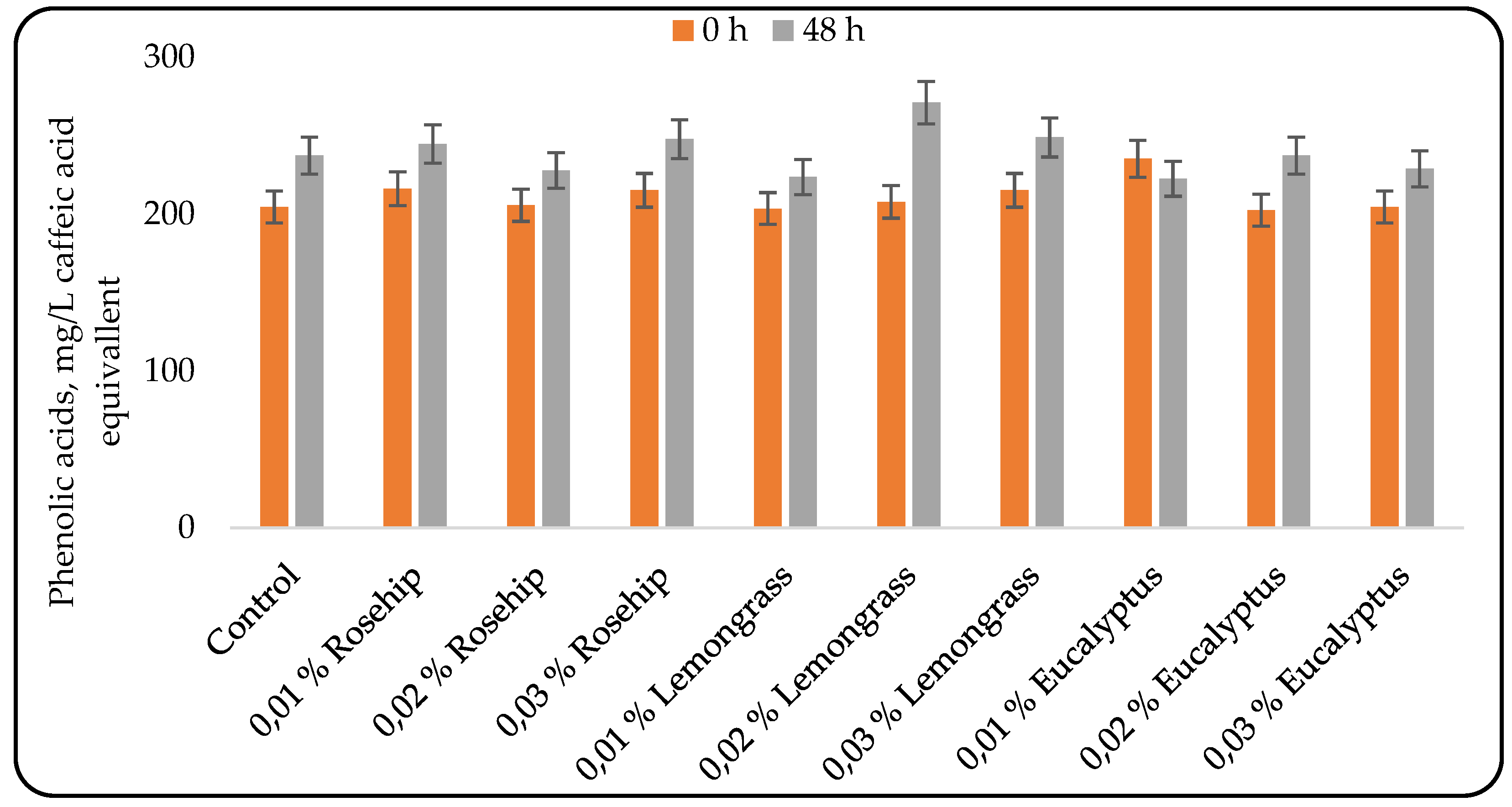

Phenolic acids contribute to certain organoleptic properties, such as sour and bitter flavors. However, their primary medicinal significance lies in their antioxidant and antiradical activities, which arise from their chemical structure [

27]

. The results for phenolic acids are presented in Figure 2. Similar to the trend observed for total phenolic compounds (Figure 1), the concentration of phenolic acids increased during lactic acid fermentation in all variants except the one containing 0.01% eucalyptus oil. Again, no correlation was found between the oil concentration and the phenolic acid content. The addition of rosehip oil resulted in similar phenolic acid concentrations in beverages containing 0.01% and 0.03% oil. The highest phenolic acid concentration was observed in the beverage supplemented with 0.02% lemongrass oil. Interestingly, the beverage with 0.01% eucalyptus oil was the only variant that showed a decrease in phenolic acid content during lactic acid fermentation. Moreover, at the beginning of fermentation, this variant exhibited the highest initial phenolic acid concentration.

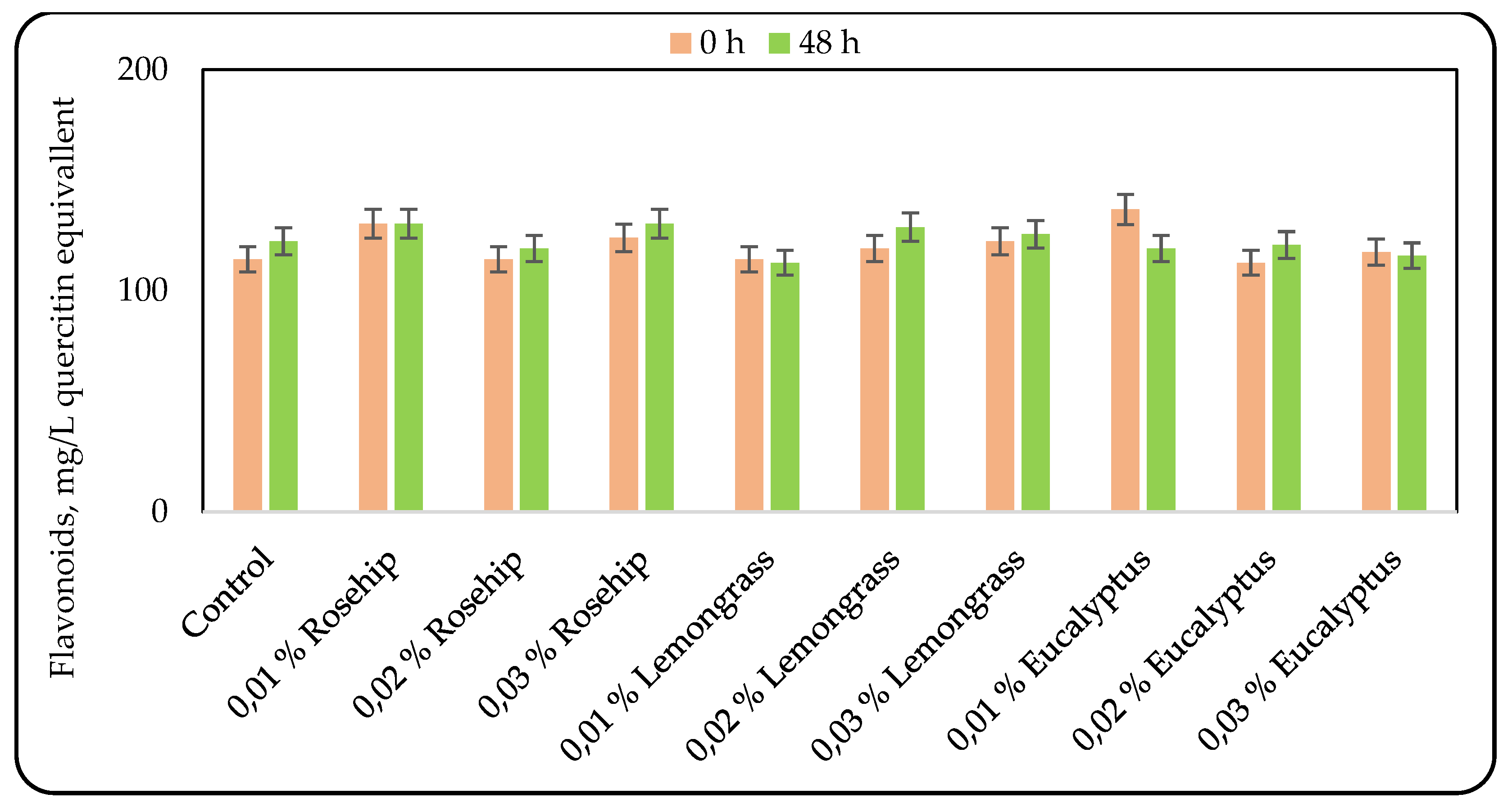

Flavonoids are particularly beneficial bioactive compounds, acting as antioxidants and providing protection against cardiovascular diseases, certain types of cancer, and age-related degeneration of cellular components [

28]. Changes in flavonoid content during fermentation depended on both the type and concentration of the added essential oil (

Figure 3). The control sample, the beverage with 0.02 % lemongrass oil, and those with 0.01 % and 0.02 % eucalyptus oil exhibited significant differences in flavonoid concentration between the beginning and the end of fermentation. However, a decrease in flavonoid concentration was observed only in the beverage containing 0.01 % eucalyptus oil. Across all formulations, the flavonoid content ranged between 112 mg/L and 129 mg/L quercetin equivalents.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) strains possess β-glucosidase enzymes that play a pivotal role in hydrolyzing flavonoid conjugates during fermentation, thereby influencing the bioavailability of polyphenols. The distinct metabolic behavior observed in the beverage containing 0.01 % eucalyptus oil may be attributed to the inhibitory effects of the oil’s bioactive components on LAB activity, which could suppress β-glucosidase production or activity. Consequently, reduced enzymatic hydrolysis may have limited the release of flavonoid aglycones, leading to the observed decrease in total flavonoid content. Alternatively, the unique adaptability and enzymatic capacity of the LAB strain under varying oil concentrations may also contribute to differential transformation of phenolic compounds during fermentation [

29].

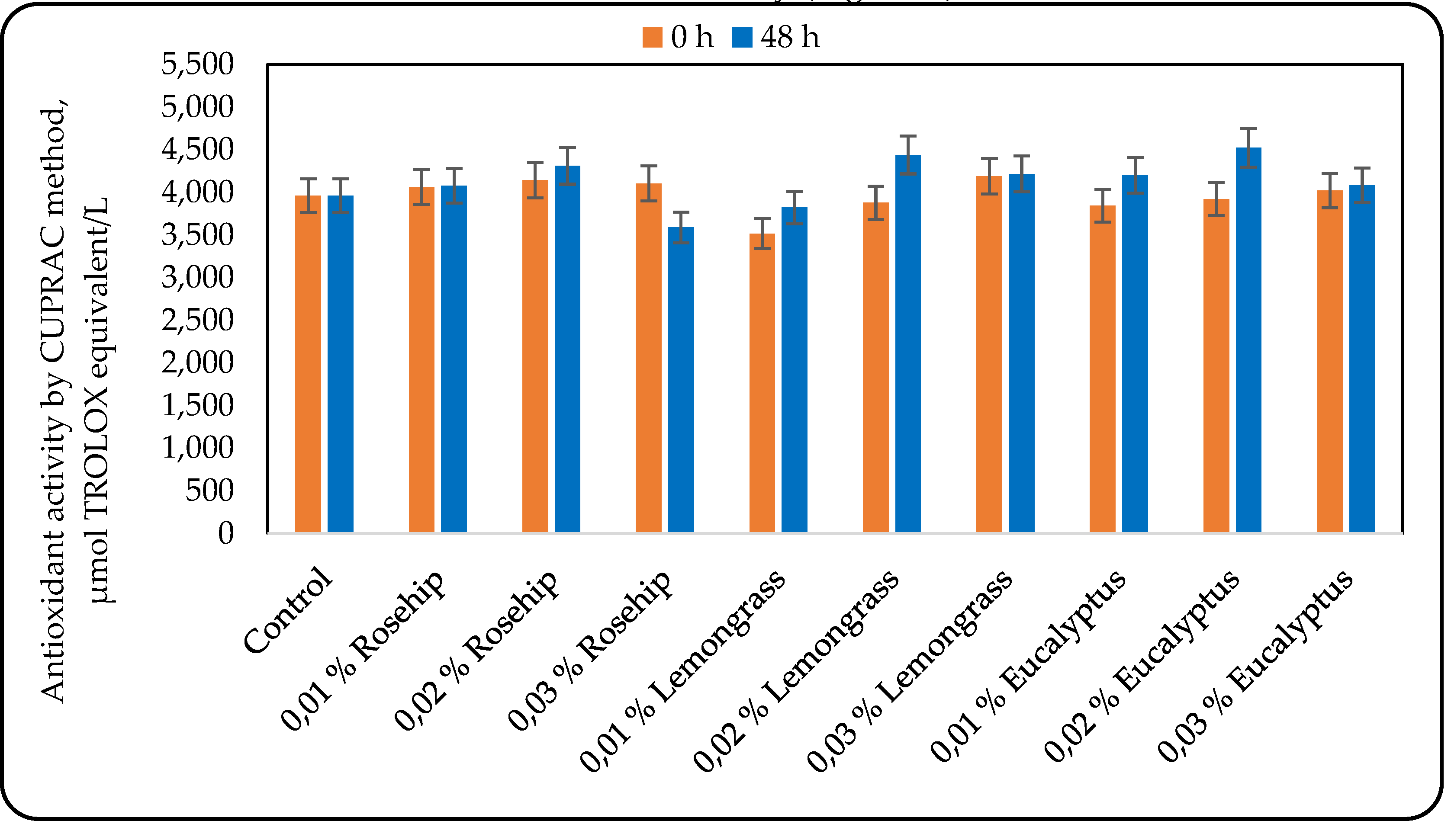

3.3. Effect of the Oil Addition on the Antioxidant Activity (AOA)

Many factors such as structural properties, temperature, the characteristics of the substrate susceptible to oxidization, concentration, along with the presence of synergistic and pro-oxidant compounds and the physical state of the system, influence the efficacy of antioxidants. Therefore, a single antioxidant property model cannot fully reflect the antioxidant capacity of all samples [

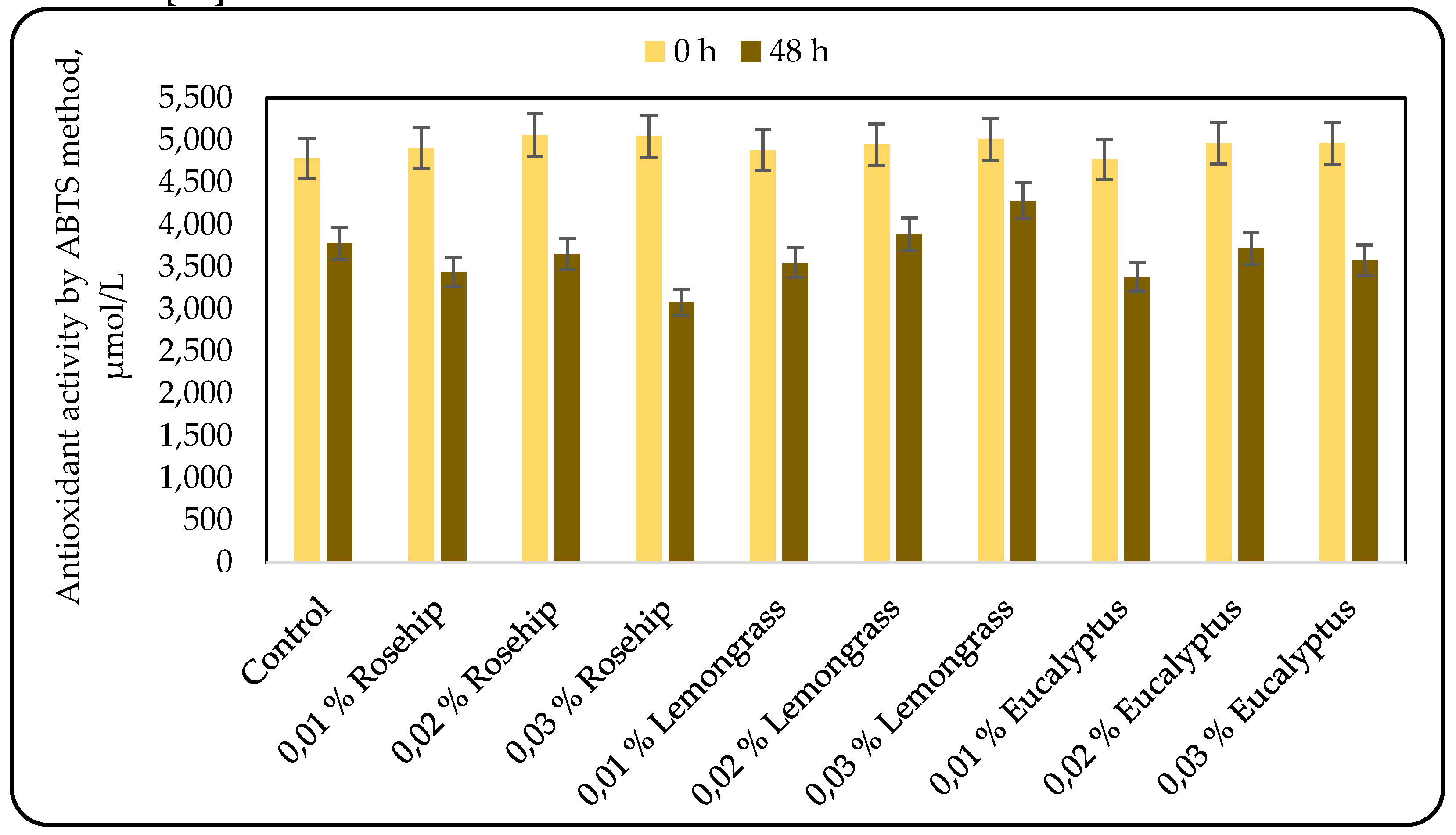

30]. Consequently, two antioxidant activity assays were selected to reflect the mechanisms of antioxidant action: the cupric reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC) and the ABTS radical scavenging activity. The results for the antioxidant activity, measured by the CUPRAC and the ABTS methods are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, respectively.

The results for the antioxidant activity, measured by CUPRAC were very interesting: in some cases the antioxidant activity increased during lactic acid fermentation, in other – it did not change, and only the addition of 0.03% rosehip oil resulted in a decrease in the antioxidant activity. However, at the end of the fermentation all the beverages produced with 0.02% oil addition showed the highest antioxidant activity (Figure 4).

3.4. Effect of Oil Addition On the Sensory Evaluation of the Beverages Produced

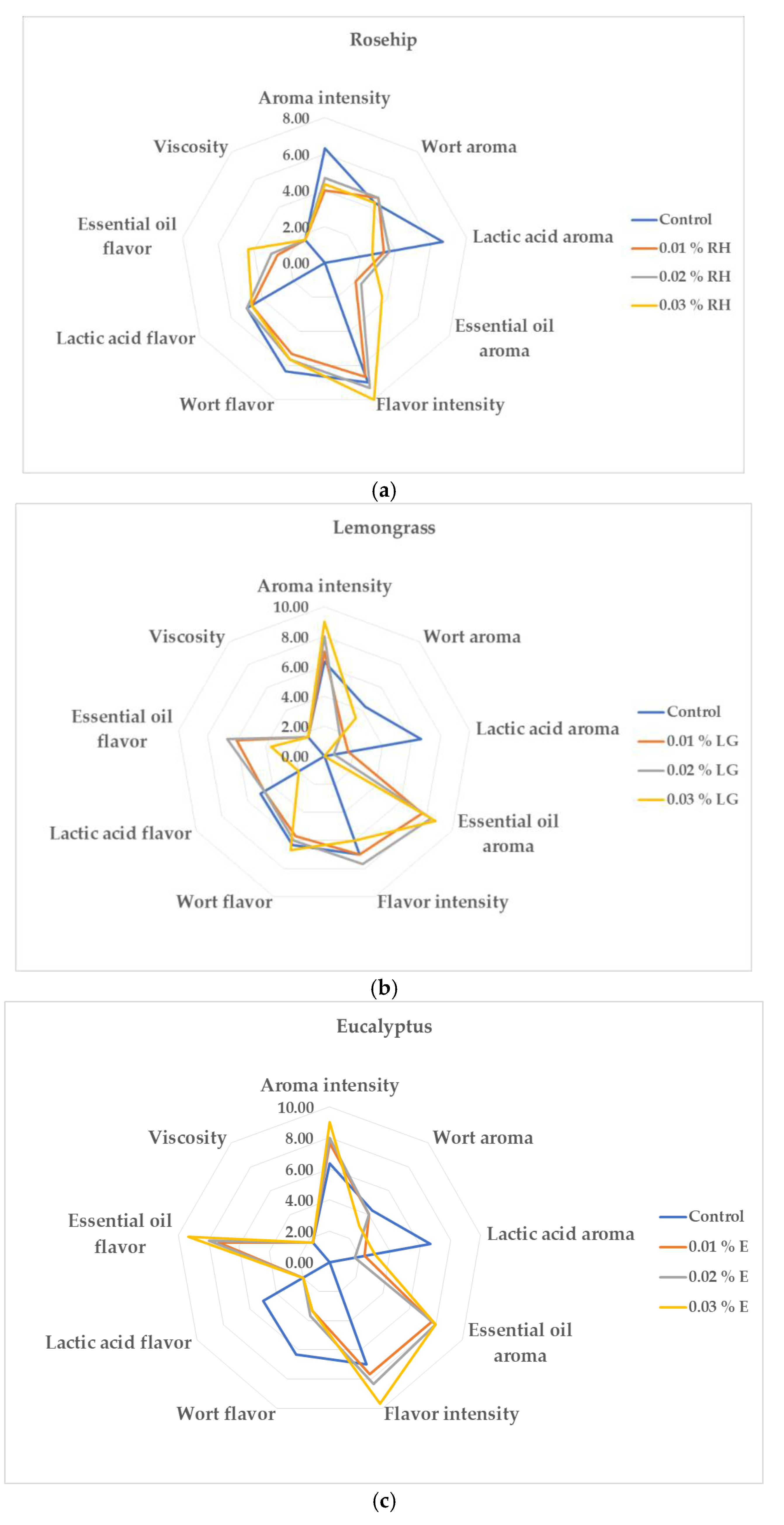

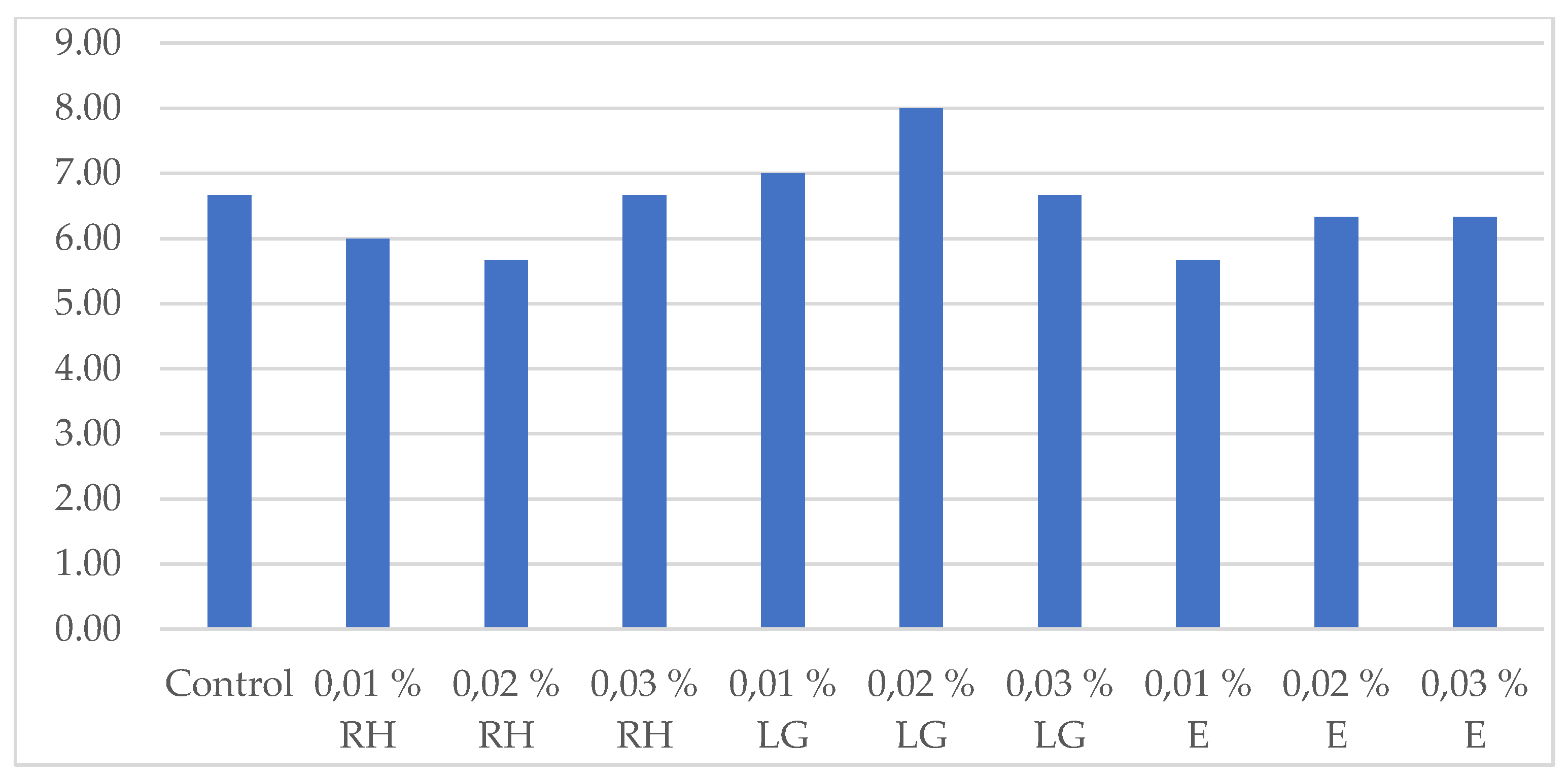

Lactic acid fermented wort beverages are poorly accepted by consumers because of their sour or worty-like taste and aroma [34]. Therefore, oil addition can be used as a tool for improvement not only of the beverages biological value, but also of their sensory profile. However, sometimes the oil addition improved the beverage flavor and aroma, but sometimes the beverage flavor and aroma were so strong that consumers did not like beverages with oil addition. Sensorial evaluation of all beverages produced was made at the end of the lactic acid fermentation and the results are shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

Figure 6a shows that the rosehip oil addition enhanced the wort aroma of the beverages produced but did not affect wort flavor.

Figure 6b shows that the increase in the lemongrass oil concentration did not result in the highest marks for essential oil aroma and flavor as for the other beverages. Moreover, when 0.03% lemongrass oil was added, the beverage was with wort flavor and aroma because of stuck lactic acid fermentation. The positive correlation between eucalyptus oil concentration and the intensity of beverage flavor and aroma is presented in

Figure 6c and the beverages with higher eucalyptus oil concentrations were preferred by the panel. In order to evaluate the appropriate combination oil-concentration, a total evaluation of the beverages was made and the results are presented on

Figure 7. Lemongrass oil addition improved to the greatest extent the lactic acid wort-based beverage sensory characteristics because all the beverages with this oil received higher or equal score to the control. It can be attributed to citral (neral and geranial), which masks the acidic note of lactic fermentation and contributes a fresh citrus aroma [

12]. Conversely, eucalyptol in eucalyptus oil imparted camphoraceous and medicinal notes that reduced acceptance, while rosehip oil added subtle fruity undertones but limited aroma intensity. These findings highlight the importance of balancing volatile composition and microbial metabolism to achieve optimal sensory perception in functional fermented beverages.

4. Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that supplementation of lactic acid–fermented wort-based beverages with rosehip, lemongrass, and eucalyptus essential oils significantly influenced fermentation performance, phenolic composition, antioxidant capacity, and sensory quality. Essential oils can serve as dual-function ingredients—providing both bioactive and sensory enhancement—when used at optimal levels that maintain lactic acid bacteria activity. For large-scale beverage production, an appropriate balance between microbial performance, functional benefits, and consumer-preferred aroma and flavor profiles must be achieved. Among the tested formulations, the addition of 0.02 % lemongrass oil yielded the most balanced outcome, characterized by enhanced phenolic enrichment, high antioxidant capacity, and the most favorable sensory scores. Therefore, this formulation will be used in future investigations focused on evaluating storage stability, antioxidant retention, and overall product acceptability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K., V.S.; methodology, G.K.,V.S; software, G.K., R.D.-K.; validation, Y.G., G.K., R. D.-K.; formal analysis, F.B., Y.G., V.S., B.G.; investigation, F.B., Y.G., V.S., B.G.; resources, R.D.-K.; data curation, G.K., V.S., R.D.-K.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S., Y.G.; writing—review and editing, G.K., R.D.-K; visualization, FG.K., V.S., R.D.-K.; supervision, G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbasi, A.; Sarabi-Aghdam, V.; Fathi, M.; Abbaszadeh, S. Non-Dairy Fermented Probiotic Beverages: A Critical Review on the Production Techniques, Health Benefits, Safety Considerations and Market Trends. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 28.

- Ziarno, M.; Cichońska, P. Lactic Acid Bacteria-Fermentable Cereal- and Pseudocereal-Based Beverages. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kharousi, Z.S. Highlighting Lactic Acid Bacteria in Beverages: Diversity, Fermentation, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Foods 2025, 14, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, M.; Goranov, B.; Shopska, V.; Denkova-Kostova, R.; Lyubenova, V.; Kostov, G. Production of lactic acid wort-based beverages with mint essential oil addition. Eco. Eng.Environ. Prot. 2021, 2, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bukvicki, D.; D’Alessandro, M.; Rossi, S.; Siroli, L.; Gottardi, D.; Braschi, G.; Patrignani, F.; Lanciotti, R. Essential Oils and Their Combination with Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bacteriocins to Improve the Safety and Shelf Life of Foods: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.C.D; Gobato, C.; Pereira, K.N.; Carvalho, M.V.; Santos, J.V.; Pinho, G.D.; Kamimura, E.S. . Application of essential oils as natural antimicrobials in lactic acid bacteria contaminating fermentation for the production of organic cachaça. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 424, 110742 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiralan, M.; Yildirim, G. Rosehip (Rosa canina L.) Oil. In: Fruit Oils: Chemistry and Functionality. Ramadan, M. (eds) Springer, 2019, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Ilyasoğlu, H. Characterization of Rosehip (Rosa canina L.) seed and seed Oil. Int. J. Food Prop., 2014, 17 (7), 1591-1598. [CrossRef]

- Wirkowska-Wojdyła, M.; Ostrowska-Ligęza, E.; Górska, A.; Brzezińska, R.; Piasecka, I. Assessment of the nutritional potential and resistance to oxidation of sea buckthorn and rosehip oils. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibenda, J.J.; Yi, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q. Review of phytomedicine, phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology, toxicology, and pharmacological activities of Cymbopogon genus. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 997918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, K.B.S.; Mukherjee, S.; Mahato, K.; Sinha, A.; Mandal, V. An integrated holistic approach to unveil the key operational learnings of solvent-free microwave extraction of essential oil: An effort to dig deep-The case of lemongrass. Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 165, 117131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, E.; Kozłowska, M.; Gruczyńska-Sękowska, E.; Kowalska, D.; Tarnowska, K. Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil: Extraction, composition, bioactivity and uses for food preservation—A review. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019, 69, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, I.Y.; Perdana, M.I.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Csupor, D.; Takó, M. Exploring the Clinical Applications of Lemongrass Essential Oil: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.; Kefi, S.; Tabben, O.; Ayed, A.; Jallouli, S.; Feres, N.; Hammami, M.; Khammassi,S. ; Hrigua, I.; Nefisi, S.; Sghaier, A.; Limam, F.; Elkahoui, S. Variation in chemical composition of Eucalyptus globulus essential oil under phenological stages and evidence synergism with antimicrobial standards. Int. Crop Prod. 2018, 124, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, M.; Ezazi, R. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of the essential oil of Zhumeria majdae, Heracleum persicum and Eucalyptus sp. against some important phytopathogenic fungi. J Mycol Médi 2017, 27 (4), 463-468. [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, A.; Nikkhah, H.; Shahbazi, A.; Zarin, M.K.Z.; Iz, D.B.; Ebadi, M.-T.; Fakhroleslam, M.; Beykal, B. Cumin and eucalyptus essential oil standardization using fractional distillation: Data-driven optimization and techno-economic analysis. Food Bioprod Process 2024, 143, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goranov, B.; Dzhivoderova-Zarcheva, M.; Shopska, V.; Denkova Kostova, R.; Kostov, G. Effect of mint essential oil addition on lactic acid fermentation in stirred tank bioreactor. Journal of International Scientific Publications: Materials, Methods and Technology (Online). 2023, 17, 202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Goranov, B.; Denkova-Kostova, R.; Shopska, V.; Kostov, G. Production of lactic acid wort-based beverage with raspberry seed oil addition under static and dynamic conditions. Bio Web Conf, 2024, 102, 01015, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Shopska, V.; Denkova-Kostova, R.; Dzhivoderova-Zarcheva, M.; Teneva, D.; Denev, P.; Kostov, G. Comparative Study on Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Different Malt Types. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analytica - EBC, Fachverlag Hans Carl, Nürnberg, 2005.

- Nsogning, S.D.; Fischer, S.; Becker, T. Investigating on the fermentation behavior of six lactic acid bacteria strains in barley malt wort reveals limitation in key amino acids and buffer capacity. Food microbiol 2018, 73, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, K.; Petelkov, I.; Shopska, V.; Denkova, R.; Gochev, V.; Kostov, G. Investigation of mashing regimes for low-alcohol beer production. J Inst Brew, 2016, 122 (3), 508-516. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Pacheco, M.M.; Torres-Moreno, H.; Flores-Lopez, M.L.; Velázquez Guadarrama, N.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Ortega-Ramírez, L.A.; López-Romero, J.C. Mechanisms and Applications of Citral’s Antimicrobial Properties in Food Preservation and Pharmaceuticals Formulations. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagdi, C.; Bouaouda, K.; Rahhal, R.; Hsaine, M.; Badri, W.; Fougrach, H.; El Hajjouji, H. Phenolic compounds, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of the methanolic extracts of Euphorbia resinifera and Euphorbia echinus. Sci. Afr. 2023, 21, 017799–e1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayanti, E.D.; Setiawan, N.C.E.; Christi, J.P. Effect of Lactic Acid Fermentation on Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Fig Fruit Juice (Ficus carica). Atlantis Press 2017, 2, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, P. M. de L.; Dantas, A. M.; Morais, A. R. dos S.; Gibbert, C. C. H. K.; Lima, M. dos S.; Magnani, M.; Borges, G. da S. C. Juá fruit (Ziziphus joazeiro) from Caatinga: A source of dietary fiber and bioaccessible flavanols. Food Res Int 2020, 129, 108745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, M.; Kapusta, K.; Kołodziejczyk, W.; Saloni, J.; Żbikowska, B.; Hill, G.A.; Sroka, Z. Antioxidant Activity of Selected Phenolic Acids–Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power Assay and QSAR Analysis of the Structural Features. Molecules 2020, 25, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewick, P.M. Medicinal natural products - a biosynthetic approach, John Wiley & Sons England, 2001.

- Khedhri, S.; Polito, F.; Caputo, L.; De Feo, V.; Khamassi, M.; Kochti, O.; Hamrouni, L.; Mabrouk, Y.; Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; et al. Chemical Composition, Antibacterial Properties, and Anti-Enzymatic Effects of Eucalyptus Essential Oils Sourced from Tunisia. Molecules 2023, 28, 7211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical methods used in determining antioxidant activity: A review. Int Mol Sci 2021, 22(7), 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afrin, F.; Ahsan, T.; Mondal, M.N.; Rasul, M.G.; Afrin, M.; Silva, A.A.; Yuan, C.; Shah, A.K.M.A. Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of some selected seaweeds from Saint Martin’s Island of Bangladesh. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N; Bristi, N.J.; Rafiquzzaman, M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharm J 2013, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwaw, E.; Ma, Y.; Tchabo, W.; Apaliya, M.T.; Wu, M.; Sackey, A.S. Effect of lactobacillus strains on phenolic profile, color attributes and antioxidant activities of lactic-acid-fermented mulberry juice. Food Chem 2018, 250, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).