Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. The Ethical Dimension of Food Security – What Does Food Ethics Mean?

2.2. Food Citizenship – Democratic Responsibility and Participation

2.3. Ethics, the Right to Food and Collective Responsibility

2.4. Recent Literature and Foundations for a New Framework

2. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Analytical Methodology

-

Descriptive analysis of statistical data. Relevant indicators for the four pillars of food security (availability, accessibility, utilization, stability) were selected and correlated with data on food waste and food insecurity. In particular, the following were analyzed:

- -

- - the amount of food waste generated annually in Romania;

- -

- - the structure of generation sources (households, retail, HoReCa);

- -

- - the share of the population that cannot afford a regular nutritious meal;

- -

- - the proportion of consumers who consider ethical aspects in their eating behavior.

- Regulatory and legislative analysis. The evolution of the legal framework regarding food waste prevention, the obligation of donation/reuse and the incentives offered for responsible food behavior were analyzed. The extent to which these regulations institutionalize ethical responsibility was also evaluated.

- Interpretive and conceptual analysis. The data were interpreted in relation to the central hypothesis of the paper, according to which the current food security framework is insufficient without the integration of an ethical dimension. The correlation between statistics, norms and behaviors was thus traced, to highlight the need to formalize a fifth pillar: the ethical one.

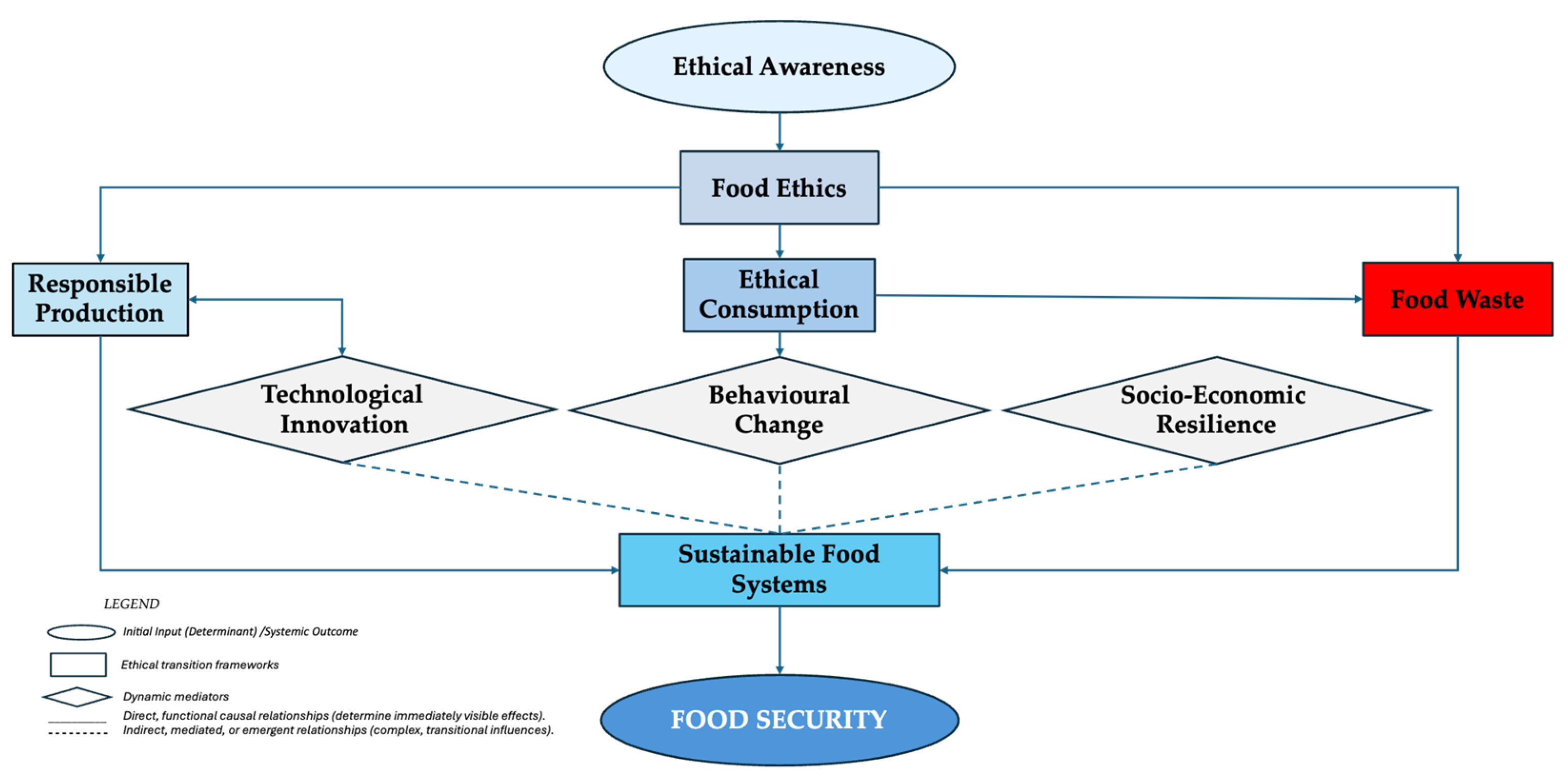

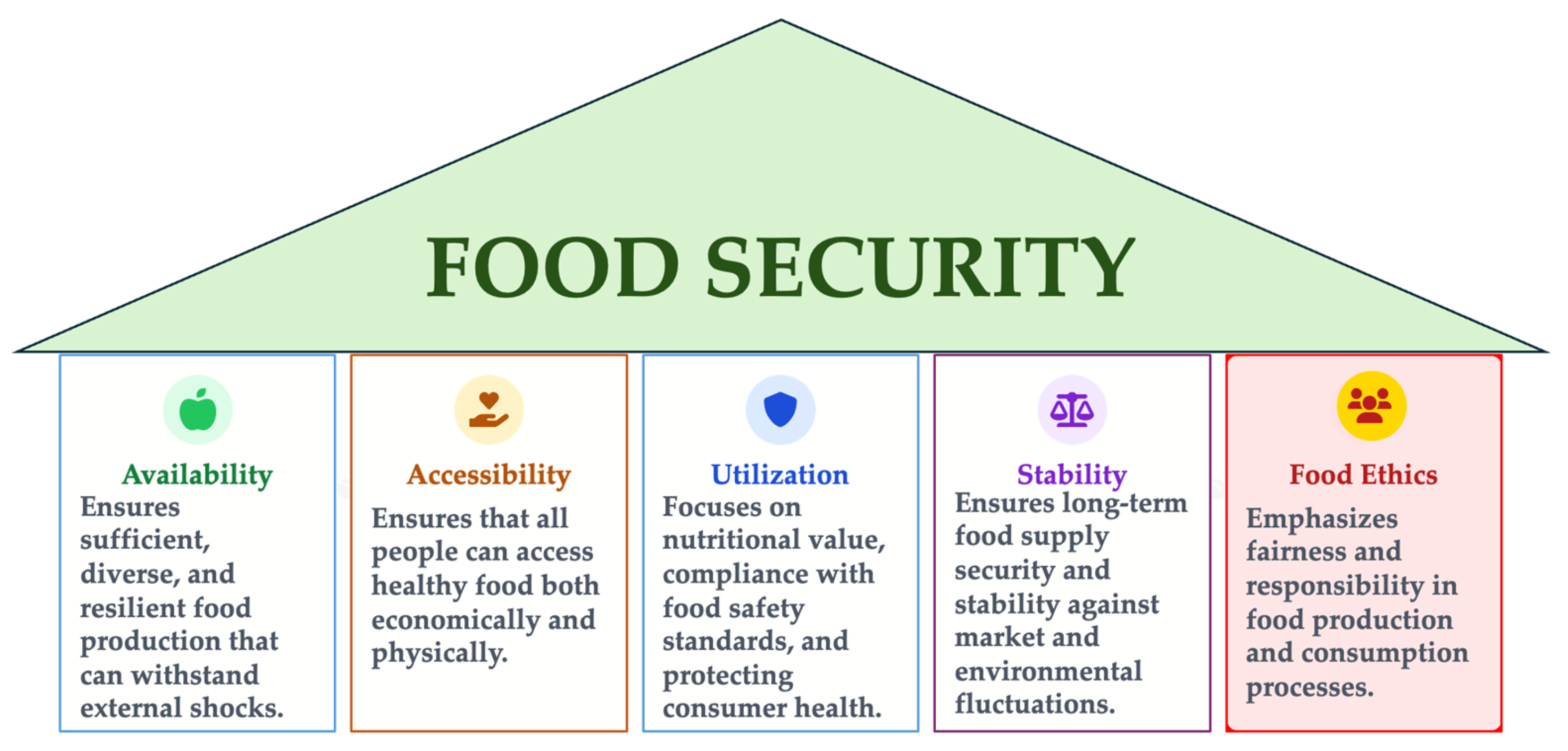

- Graphic illustration and visual synthesis. Tables and figures were produced that summarize the relationship between food ethics, food waste and food security, highlighting the expansion of the FAO framework by including the food ethics pillar.

3.3. Statistical Methodology

- Total (aggregate changing according to the context) - T

- Primary production of food - agriculture, fishing and aquaculture - PPF

- Manufacture of food products and beverages - MFP

- Retail and other distribution of food - RDF

- Restaurants and food services - RFS

- Total activities by households - TAH.

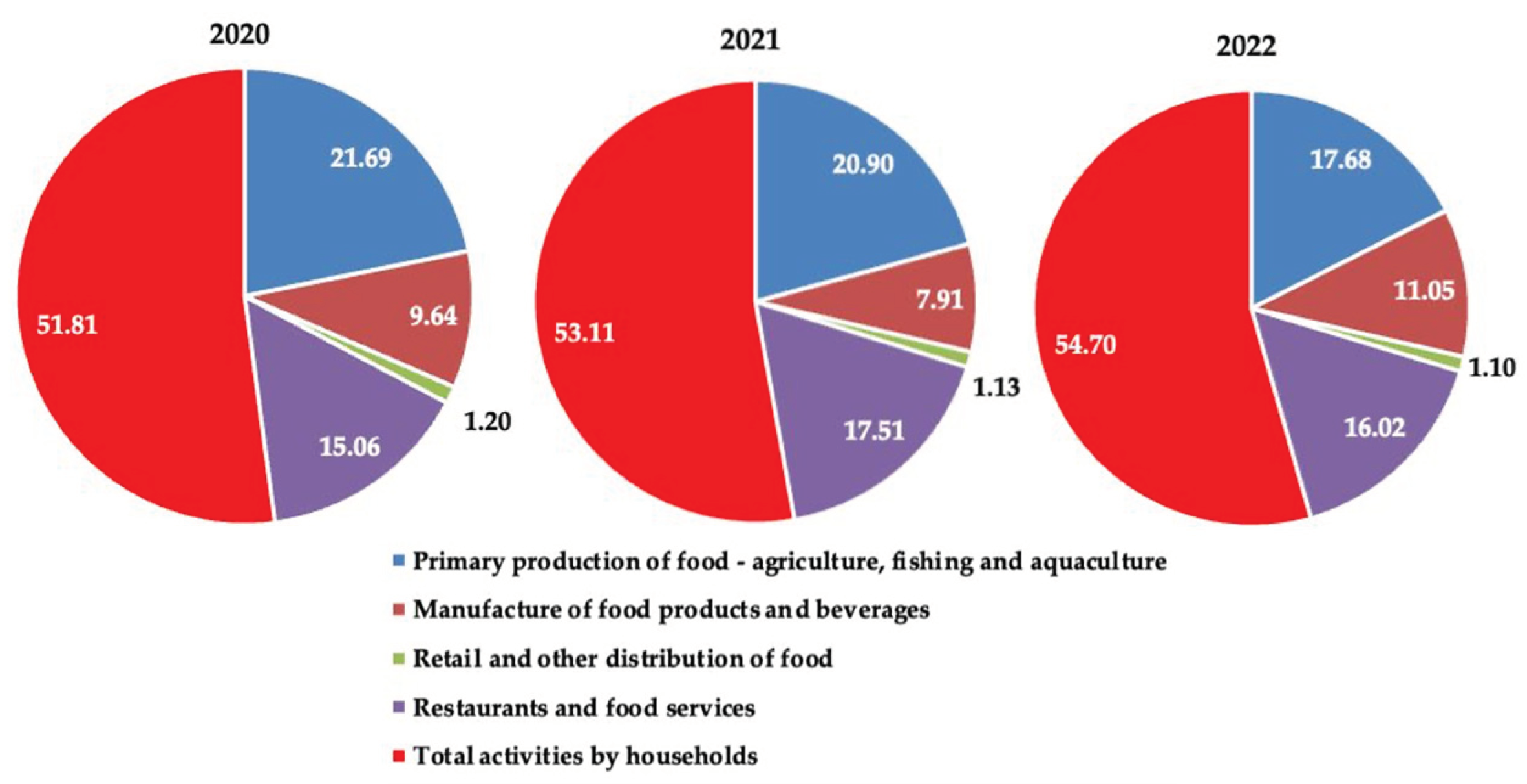

3.3.1. Analysis of the Percentage Contribution of Variables to Total Waste

3.3.2. Correlation Analysis of Each Segment of the Food Chain with Total Waste

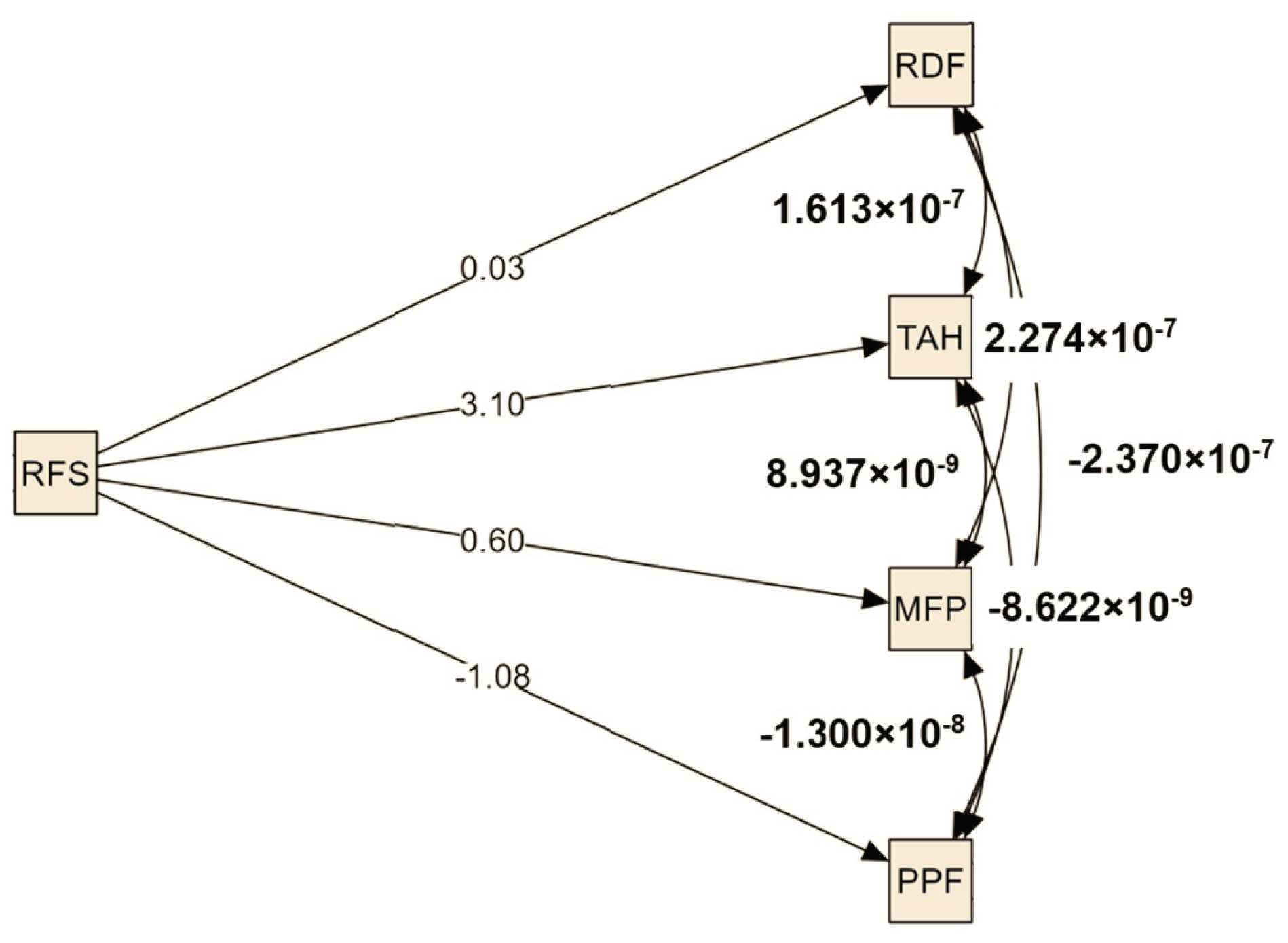

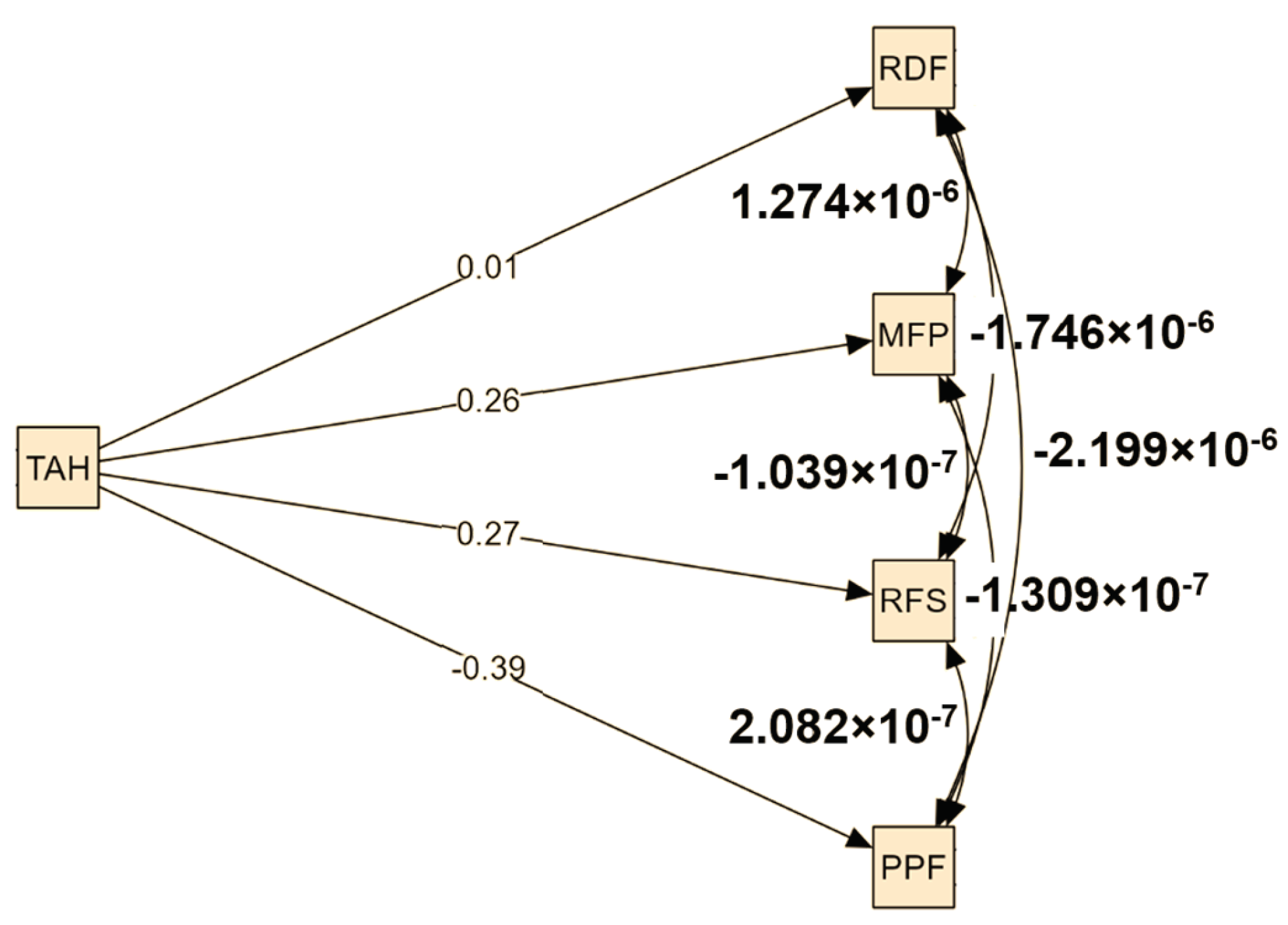

3.3.3. PATH Analysis

3.4. Study Limitations

3.5. Ethical Considerations

- transparency of sources and correct attribution of ideas and data used;

- objectivity of analysis and avoiding drawing conclusions that are not supported by the data;

- respect for human dignity, through the emphasis on social responsibility in food security;

- commitment to equity, reflected in the proposal of a conceptual framework that integrates food ethics and citizenship as essential elements of public policies.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Assessment of Food Waste and Food Insecurity

4.2. Analysis of the Percentage Contribution of Food Chain Segments to the Variation in Total Waste

4.2.1. Correlation Analysis of Each Segment of the Food Chain with Total Waste

4.2.3. Results of the PATH Analysis

- -

- RFS as a causal variable for the other variables,

- -

- TAH as a causal variable for the other variables.

4.2.3.1. Model 1: RFS as a Causal Variable

4.2.3.2. Model 2: TAH as a Causal Variable

4.3. Legislative and Institutional Analysis – Integrating Ethics into National Food Policy

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MADR) - coordinator of policies on food loss reduction and redistribution;

- National Sanitary-Veterinary and Food Safety Authority (ANSVSA) - responsible for regulating food safety and food donations;

- Ministry of Environment, Waters and Forests (MMAP) - which integrates food waste into circular economy and waste management policies;

- Ministry of Education and Research (MEC) - limited involvement, through educational programs such as Green Week or waste prevention campaigns in schools [45].

4.4. Behavioral and Cultural Insights – Ethical Awareness and Food Citizenship Among Romanian Consumers

4.5. Integrative Synthesis – Strengthening Food Security by Integrating the Ethical Pillar

4.5.1. Food Ethics and Food Availability

4.5.2. Food Ethics and Access to Food

4.5.3. Food Ethics and Food Use

4.5.4. Food Ethics and Food System Stability

4.5.5. Integrative Vision

4.6. Conceptual Model – Ethical Transition Frameworks Linking Food Ethics, Food Waste, and Food Security

5. Discussion

5.1. Reconceptualizing Food Security Through the Ethical Lens

- -

- Availability ensures sufficient, diversified and resilient production, capable of withstanding external shocks;

- -

- Accessibility guarantees equitable and economic access to safe and healthy food for all;

- -

- Utilization focuses on nutritional value, food safety and protecting consumer health;

- -

- Stability aims at the long-term security of food supply, in the face of market fluctuations and climate risks;

- -

- Food Ethics adds the moral dimension, which links all other components through equity, responsibility and social justice.

5.2. Ethical Food Governance – From Compliance to Moral Responsibility

5.3. From Consumers to Food Citizens – Social Change Through Ethical Awareness

- affects availability, through overexploitation of resources;

- distorts access, by polarizing between abundance and poverty;

- limits use, through unbalanced diets and food waste;

- undermines stability, through inequalities and pressures on the environment.

5.4. Policy Implications and Regional Relevance

- in the availability pillar, by reducing losses and redistributing food;

- in access, by guaranteeing the right to food for vulnerable groups;

- in use, through food education and transparency;

- in stability, by promoting climate resilience and intergenerational solidarity.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

- comparative studies between EU states on the integration of ethics into food policies;

- assessing ethical perceptions among economic actors in the agri-food chain;

- analysis of the impact of sustainability education on consumer behavior.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balan, I.M.; Trasca, T. Claiming Food Ethics as a Pillar of Food Security—Insights from the Romanian Context, in Proceedings of the 6th International Electronic Conference on Foods, 28–30 October 2025, MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, https://sciforum. net/paper/view/25076. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Rome Declaration on World Food Security and World Food Summit Plan of Action, 1996. https://www.fao.org/4/w3613e/w3613e00.htm. (accessed at accessed at 9 October 2025).

- European Commission. EU Action Plan on Food Waste. https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/food-waste/eu-actions-against-food-waste_en.

- Gustafson, D.; Gutman, A.; Leet, W.; Drewnowski, A.; Fanzo, J.; Ingram, J. Seven Food System Metrics of Sustainable Nutrition Security. Sustainability 2016, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerten, D.; et al. Feeding ten billion people is possible within planetary boundaries. Nature Sustainability 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; et al. The Lancet Commissions. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission, 2019. [CrossRef]

- IPES-Food. A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045, 2021. https://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/LongFoodMovementEN.pdf. (accessed at 1 October 2025).

- FAO. The Right to Food Guidelines: 20 Years of Implementation, 2024. [CrossRef]

- MADR. Raport național privind risipa alimentară în România, 2023. https://www.madr.ro/comunicare/9165-a-fost-actualizata-legislatia-privind-diminuarea-risipei-alimentare.html. (accessed at 19 September 2025).

- Eurostat. Eurostat regional yearbook 2025 edition. PDF: ISBN 978-92-68-29695-0 ISSN 2363-1716 doi:10.2785/5478134 KS-01-25-037-EN-N. (accessed at 1 October 2025).

- Law, no. 217/2016 on reducing food waste, updated 2024. Official Gazette of Romania, Part I, no. 17/2024. Available at: https://legislatie.just.ro/public/DetaliiDocument/183792. (accessed at ). 19 October.

- Balan, I.M.; Gherman, E.D.; Brad, I.; Gherman, R.; Horablaga, A.; Trasca, T.I. Metabolic Food Waste as Food Insecurity Factor—Causes and Preventions. Foods 2022, 11, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renting, H.; Schermer, M.; Rossi, A. Building Food Democracy: Exploring Civic Food Networks and Newly Emerging Forms of Food Citizenship. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 2012, 19, 289–307, https://edepot.wur.nl/319481. [Google Scholar]

- Food Ethics Council. What is Food Ethics? 2020. https://www.foodethicscouncil.org. (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- EAT-Lancet Commission. Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems: Food, Planet, Health. 2019. https://eatforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/EAT-Lancet_Commission_Summary_Report.pdf. (accessed at 19 October 2025).

- Booth, S.; Coveney, J. Food Democracy: From Consumer to Food Citizen, 2015. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.B. The Spirit of the Soil: Agriculture and Environmental Ethics 2nd ed., 2017. Routledge: London, UK. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, J. L. Eating Right Here: Moving from Consumer to Food Citizen. Agriculture and Human Values 2005, 22(3), 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. The Real Cost of Cheap Food, 2011. Routledge: London, UK. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Voluntary Guidelines to Support the Progressive Realization of the Right to Adequate Food in the Context of National Food Security. 2004, Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-105336-2 https://www.fao.org/4/y7937e/y7937e00.pdf. (accessed at 9 October 2025).

- IPES-Food. The Politics of Protein: Examining Claims about Livestock, Fish, ‘Alternative Proteins’ and Sustainability. International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems, 2022. https://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/PoliticsOfProtein.pdf.

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

- United Nations. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights.

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, 2025. https://www.fao.org/publications/fao-flagship-publications/the-state-of-food-security-and-nutrition-in-the-world/en. (accessed at 1 August 2025).

- Romanian Academy, Presidential Commission for Public Policies for the Development of Agriculture ‘’National Strategic Framework for the Sustainable Development of the Agri-Food Sector and Rural Space in the Period 2014–2020–2030’’, 2013. https://acad.ro/forumuri/doc2013/d0701-02StrategieCadrulNationalRural.pdf. (accessed at 3 August 2025).

- Petroman, C.; Balan, I.M.; Petroman, I.; Orboi, M.D.; Băneș, A.; Trifu, C.; Marin, D. National grading of quality of beef and veal carcasses in Romania according to “EUROP” system, Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment 2009, 7(3&4), 173–174.

- Mateoc Sirb, N.; Otiman, P.I.; Mateoc, T.; Salasan, C.; Balan, I.M. Balance of Red Meat in Romania—Achievements and Perspectives.” In From Management of Crisis to Management in a Time of Crisis, Proceedings of the 5th Review of Management and Economic Engineering International Management Conference, Cluj-Napoca, Romania 2016, 22-24.

- Eurostat. Inability to afford a meal with meat, chicken, fish (or vegetarian equivalent) every second day, 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ilc_mdes03/default/table?lang=en&category=livcon.ilc.ilc_md.ilc_mdes https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ilc_mdes03/default/table?lang=en. (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Romanian Parliament. LAW no. 49 of March 15, 2024, amending and supplementing Law no. 217/2016 on reducing food waste, 2024. https://legislatie.just.ro/public/DetaliiDocument/280058. (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- FAOSTAT. Food and agriculture data, 2025. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home.

- Eurostat. Statistics Explained. Food waste and food waste prevention – estimates, 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Food_waste_and_food_waste_prevention_-_estimates.

- European Commission. Food, Farming, Fisheries. About Food Waste, 2025. https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/food-waste_en.

- National Veterinary Sanitary and Food Safety Authority (ANSVSA). Risipa alimentară – informații pentru public, 2024. https://www.ansvsa.ro/informatii-pentru-public/risipa-alimentara/. (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Kent State University. 2021. Pearson Correlation https://libguides.library.kent.edu/SPSS/PearsonCorr.

- PATH JASP Team. JASP, Version 0.16.1, Computer software; JASP Team: Amsterdam online: https://jasp-stats.org/.

- Microsoft, Predict data trends. Microsoft Support, 2024. https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/predict-data-trends-96a1d4be-5070-4928-85af-626-fb5421a9a.

- Eurostat. Food waste and food waste prevention by NACE Rev. 2 activity - tonnes of fresh mass, 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/env_wasfw/default/table?lang=en.

- Salasan, C.; Balan, I.M. The environmentally acceptable damage and the future of the EU’s rural development policy. Economics and Engineering of Unpredictable Events, 2022. London: Routledge, 49–56. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy: For a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system, 2020. Brussels: European Union. la: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en. (accessed 19 October 2025).

- Bob, F.; Madalina, B.A.; Sircuta, A.; Grosu, I.D.; Schiller, A.; Petrica, L.; Schiller, O.M. (2025). # 2163 Relationship between antioxidant nutrients intake and oxidative stress in patients treated with hemodialysis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2025, 40 (Supplement_3), gfaf116-0625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamar, M.; Grosu, I.D.; Schiller, A.; Petrica, L.; Bodea, M.; Sircuta, A.; Gruescu, E.; Matei, O.D.; Tanasescu, M.D.; Golet, I.; et al. Vitamin K-Dependent Proteins as Predictors of Valvular Calcifications and Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Right to Food Guidelines: Implementation Review, 2021. Rome: FAO. https://www.fao.org/right-to-food.

- Romanian Government. Government Emergency Ordinance no. 92/2021 regarding the waste regime, 2021. https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/245846.

- Romanian Government. DECISION no. 51 of 30 January 2019 for the approval of the Methodological Norms for the application of Law no. 217/2016 on the reduction of food waste, 2019. https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/210623.

- UNEP. United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2024. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme, 2024. https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/food-waste-index-report-2024.

- Romanian Government. Romania’s National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2030. Bucharest: Department for Sustainable Development, General Secretariat of the Government, 2018. https://www.edu.ro/sites/default/files/Strategia-nationala-pentru-dezvoltarea-durabila-a-României-2030.pdf.

- Ministry of Education, Romania. National Program “Green Week”, 2023. https://www.edu.ro/psv.

- Food Ethics Council. Annual Report 2022. Brighton: FEC. https://www.foodethicscouncil.org/insights/impact-report-2022/.

- Dutch Council on Animal Affairs (RDA). Ethical Food Policy in Practice: National frameworks for moral responsibility in food systems, 2022. https://english.rda.nl. (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Food Waste Combat Association. Reducem Risipa, 2020. https://foodwastecombat.com/despre-risipa/. (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Food Bank. HELP US reduce poverty and food waste in Romania, 2020. https://bancapentrualimente.ro.

- ShareFood Romania. Share Food App, 2025. https://omasacalda.ro/en/sharefood-app/.

- European Commission. (Date marking and food waste prevention, 2023. https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/food-waste/eu-actions-against-food-waste/date-marking-and-food-waste-prevention_en.

- European Commission. Special Eurobarometer SP535: Discrimination in the European Union – Food Waste and Responsible Consumption, 2023. https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2972_99_2_sp535_eng?locale=en.

- Sircuța, A.F.; Grosu, I.D.; Schiller, A.; Petrica, L.; Ivan, V.; Schiller, O.; Maralescu, F.M.; Palamar, M.; Mircea, M.N.; Nisulescu, D.; Golet, I.; Bob, F. Associations Between Inflammatory and Bone Turnover Markers and Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients. Biomedicines, 2025, May 10; 13(5):1163. PMCID: PMC12109441. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balan, I.M.; Gherman, E.D.; Gherman, R.; Brad, I.; Pascalau, R.; Popescu, G.; Trasca, T.I. Sustainable Nutrition for Increased Food Security Related to Romanian Consumers’ Behavior. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiurciu, I.A.; Nijloveanu, D.; Bold, N.; Soare, E.; Firăţoiu, A.R. Study on the Perception of Romanian Consumers Regarding Food Waste. Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development, 2025, 25(1), 167-174. ISSN 2284-7995 (Print), 2285-3952 (Online). https://managementjournal.usamv.ro/pdf/vol.25_1/Art17.pdf.

- Petroman, I.; Untaru, R.C.; Petroman, C.; Orboi, M.D.; Băneș, A.; Marin, D.; Bălan, I.; Negruț, V. The influence of differentiated feeding during the early gestation status on sows prolificacy and stillborns. Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment 2011, 9, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinstra, G.G.; van der Haar, S.; Bos-Brouwers, H. Behavioural Insights on Food Waste in the European Union, 2021. https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-07/fw_lib_stud-rep-pol_swe_behavioral-insights-2021.pdf. (accessed at 1 August 2025).

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in Europe and Central Asia, 2024. [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Food Security Update | World Bank Solutions to Food Insecurity, 2025. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-update?cid=ECR_GA_worldbank_EN_EXTP_search&s_kwcid=AL!18468!3!704632427690!b!!g!!food%20insecurity&gad_source=1. (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable, 2022. https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/c0239a36-7f34-4170-87f7-2fcc179ef064.

- SURPLUS FOOD REDISTRIBUTION. N.d. Making sure no good food goes to waste. Available online at https://www.wrap.ngo/taking-action/food-drink/actions/surplus-food-waste-redistribution. ((accessed at 15 August 2025).

- IPES-Food. Guiding action for sustainable food systems, 2025. Available online at https://ipes-food.org.

- HLPE. Food Security and Nutrition: Building a Global Narrative Towards 2030. High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition, FAO, 2020. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/8357b6eb-8010-4254-814a-1493faaf4a93/content.

- Sen, A. ; Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation (Oxford, 1983; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Nov. 2003; (accessed 3 September 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2023 – Revealing the true cost of food to transform agrifood systems, 2023. Rome. [CrossRef]

- Lang, T.; Barling, D.; Caraher, M. Food Policy: Integrating health, environment and society (Oxford, 2009; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Sept. 2009; (accessed 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach, 2011, Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. https://dokumen.pub/creating-capabilities-the-human-development-approach-0674050541-9780674050549-0674061209-9780674061200.html.

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. The SDGs and the UN Summit of the Future. Sustainable Development Report 2024. 2024. Paris: SDSN, Dublin: Dublin University Press. doi:10.25546/108572 https://files.unsdsn.org/sustainable-development-report-2024.pdf. (accessed at 30 August 2025).

- UN. UN Agenda 2030, 2015. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

| Year | Total | Primary production of food - agriculture, fishing and aquaculture | Manufacture of food products and beverages | Retail and other distribution of food | Restaurants and food services |

Total activities by households | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 3,201,048 | 699.92 | 316,507 | 39,787 | 485,827 | 1,659,007 | |

| 2021 | 3,392,056 | 699.92 | 268,349 | 36.51 | 589,365 | 1,797,912 | |

| 2022 | 3,452,143 | 613,337 | 375,577 | 42,864 | 543,244 | 1,877,121 |

| Year | Total | Primary production of food - agriculture, fishing and aquaculture | Manufacture of food products and beverages | Retail and other distribution of food | Restaurants and food services |

Total activities by households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 166 | 36 | 16 | 2 | 25 | 86 |

| 2021 | 177 | 37 | 14 | 2 | 31 | 94 |

| 2022 | 181 | 32 | 20 | 2 | 29 | 99 |

| Segment | Ci (2021-2020) (%) | Ci (2022-2021) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PPF | 0.00 | 26.60 |

| MPF | 16.39 | 32.94 |

| RDF | 1.12 | 1.95 |

| RFS | 35.23 | 14.17 |

| TAH | 47.27 | 24.33 |

| Segment | r | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| PPF | -0.69 | 0.47 |

| MPF | 0.29 | 0.08 |

| RDF | 0.21 | 0.04 |

| RFS | 0.77 | 0.59 |

| TAH | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| Predictor | Outcome | β | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFS | PPF | -1.079 | 0.621 |

| RFS | MPF | 0.604 | 0.343 |

| RFS | TAH | 3,100 | 0.836 |

| RFS | RDF | 0.029 | 0.275 |

| Interaction | Residual covariances |

|---|---|

| PPF - MFP | -1,300×10-8 |

| PPF - TAH | -8.622×10-9 |

| PPF - RDF | -2.370×10-7 |

| MFP - TAH | 8.937×10-9 |

| MFP - RDF | 2.274×10-7 |

| TAH - RDF | 1.613×10-7 |

| Predictor | Outcome | β | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAH | PPF | -0.392 | 0.941 |

| TAH | RFS | 0.270 | 0.836 |

| TAH | MPF | 0.263 | 0.746 |

| TAH | RDF | 0.014 | 0.680 |

| Interaction | Residual covariances |

|---|---|

| PPF - RFS | 2.082×10-7 |

| PPF - MFP | -1.309×10-7 |

| PPF - RDF | -2.199×10-6 |

| RFS - MFP | -1.039×10-7 |

| RFS - RDF | -1.746×10-6 |

| MFP - RDF | 1.274×10-6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).