1. Introduction

Freshwater planarians can regenerate their entire body from small tissue fragments, making them popular models for regeneration and stem cell biology [

1]. Most remarkably, they can regenerate a cephalized nervous system that is compartmentalized with distinct neuronal cell populations and contains most of the same neurotransmitters as the mammalian brain [

2,

3,

4]. In asexual planarians, neuroregeneration following asexual reproduction by binary fission is equivalent to neurodevelopment [

4,

5,

6]. Because regeneration takes only 1-2 weeks [

5,

7], this invertebrate model allows for rapid studies of neurodevelopment [

4]. Moreover, planarians are sensitive to their aquatic environment and react with stereotypical behaviors when exposed to certain chemicals [

2,

5,

8,

9,

10], making them attractive models for pharmacology and toxicology. We have recently reviewed the history, challenges, and benefits of planarians as a model for neurotoxicology [

5].

Planarians ingest food via a specialized cylindrical eating tube, the pharynx, which they extend through a ventral opening to attach themselves to a food source [

11]. The pharyngeal muscles then pull tissue and fluid from the food source via peristalsis [

12,

13]. Although planarians are carnivores known to feed on a variety of living or recently dead invertebrates, including annelids, mollusks, crustaceans, and insect larvae [

14,

15], laboratories typically rely on organic homogenized beef or chicken liver as a food source [

16,

17], which differ substantially from the natural diets of planarians. Liver introduces variability as labs source liver locally, leading to differences in nutritional composition, and may have different preparation methods, which can be labor-intensive [

16]. Additionally, liver aliquots can only be stored up to 3 months at −20 °C (or 6 months at -80°C) and liver stored longer than this can lead to bacterial infections and other planarian health problems [

16]. Attempts to develop chemically defined diets for planarians have so far been unsuccessful in supporting long-term population growth [

17], highlighting the need for an improved planarian diet. Ideally, this new diet would not be of vertebrate origin, in alignment with the aim to reduce, replace and refine vertebrate animal use in research.

In this study, we report that

Dugesia japonica planarians can be successfully maintained for at least 1 year on an invertebrate food source: the red aquatic larvae of non-biting midges, also commonly referred to as bloodworms. Red midge larvae (RML) co-habitate with freshwater planarians in slow-moving bodies of water, and planarians are likely to encounter and feed on them in the wild [

18]. In fact, one study proposed using planarians as a natural pesticide against RML because planarians are excellent predators [

18]. Frozen, dead RML can be purchased in ready-to-use aliquots in bulk from commercial vendors. The ease of purchase and use of RML increases both accessibility to planarian research and decreases variability in diet between laboratories. Importantly, we found that the transcriptome of

D. japonica planarians was not drastically changed by the RML diet and that the bioactivity and potency of three well-studied chemicals in planarians (dimethyl sulfoxide, diazinon, and fluoxetine) was not different between RML-fed

D. japonica planarians and liver-fed

D. japonica. Thus, switching to this invertebrate diet does not greatly alter planarian physiology or susceptibility to chemicals, important for their use as a new approach method (NAM) to reduce vertebrate testing in toxicology and pharmacology. Finally, we demonstrate that RML are suitable for delivering dsRNA via feeding to planarians, supporting mechanistic studies using RNA interference that will elucidate greater understanding of planarian biology and augment their use as a model organism across fields, including stem cell and regenerative biology, neuroscience, toxicology, and pharmacology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Planarian Species and Husbandry

The majority of experiments were performed with

D.

japonica from an established laboratory culture and which were cultivated in our lab for >1 year on their respective diets according to standard protocols [

7,

19]. Some experiments were also performed on

Dugesia dorotocephala (Carolina Biological Supply Company, Burlington, NC), asexual (strain CIWI4) or sexual

Schmidtea mediterranea (existing laboratory cultures),

Phagocata gracilis (Ward’s Scientific, Rochester, NY), and wild planarians caught from Crum Creek, Swarthmore, PA that were cultivated in our lab for >1 year. Worms were initially stored in 0.5 g/L Instant Ocean (IO, Blacksburg Virginia) but were moved into 0.21 g/L Instant Ocean water with 0.83 mM MgSO

4, 0.9 mM CaCl

2, 0.04 mM KHCO

3, and 0.9 mM NaHCO

3 [

20], which will be referred to as planarian water. Planarians were kept in BPA-free Tupperware containers (approximately 25 cm L x 14 cm L x 8 cm H) with the lid on loosely at 20 °C in a Panasonic refrigerated incubator in the dark. Planarians were fed twice a week with either organic beef liver purchased from a local butcher, or commercially available red midge larvae (RML). The RML were bought directly from Brine Shrimp Direct and classified as

Chironomus sp. (“frozen bloodworms”). RML were stored at -80 °C and sequentially moved to -20 °C as needed for use. Frozen RML were removed from their pre-aliquoted package, slightly crushed using a clean razor blade or plastic transfer pipet, and introduced into planarian containers with a plastic transfer pipet. Planarian containers were cleaned approximately 2 hours after each feeding and again 2 days later per standard protocols [

21]. Planarians were fasted for at least 5 days before experimentation unless otherwise noted.

2.2. Regeneration Assays

Planarians raised on either liver or RML were fasted for 7 days and decapitated. Their head regeneration kinematics were quantified by measuring head width pre-amputation and blastema area on days 4-7 post amputation based on standard protocols [

22]. Eight worms per condition were analyzed. A Student’s

t-test was used to compare the average growth rate of planarian heads between the two diets.

2.3. Long-Term Population Growth Maintenance and Tracking

D. japonica planarians of 7-9 mm in length were arbitrarily selected from a container of healthy specimen maintained on a liver diet and divided into two diet groups: liver and RML. Groups of 15 planarians were stored in individual containers and stored in an 18 °C Panasonic incubator in the dark. Two independent populations were created for each diet group. Planarians were fed their respective diets of organic beef liver or frozen RML twice a week and cleaned five times a week, once before each feeding, once after each feeding and another two days after the final weekly feeding. To ensure worms were consuming enough food, worms were fed for approximately 1-2 hours until they were no longer interested in food. Planarian divisions were counted every 2 days. Tail pieces were removed from the population. One RML-fed worm became sick during the course of the experiment. This planarian was isolated in a separate petri dish and eventually died. This planarian was not replaced in the population.

2.3.1. Imaging and Image Analysis of Planarians for Population Growth

Planarians were imaged weekly for ~ 1 year starting 86 days after the creation of the populations. Before each imaging session, the worm boxes were cleaned and at least 5 representative, fully regenerated worms were transferred to petri dishes from either of the two replicate boxes. Petri dishes were placed onto an illuminated tracer panel with a visible ruler. The images were captured using an iPad once the worms began to glide and were fully elongated. Planarian area was measured using ImageJ software [

23] using a similar process as described in [

22].

2.3.2. Statistical Analysis for Long-Term Population Growth

Statistical analysis was performed in R (Version 4.5.0) [

24]). To examine reproduction rate, the cumulative number of divisions over time was quantified. We modeled reproduction as a function of diet*time using a negative binomial generalized linear model with log link using the MASS package [

25]. Statistical significance was assessed using Wald

z-tests.

n = 2 biological replicates (separate boxes) with 15 worms each. We modeled the area of individual worms as a function of diet*time with a Gaussian generalized linear model with identity link and assessed for statistical significance with a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey Honestly Significant Difference Test.

n = 5-18 biological replicates (individual worms) combined from the two boxes per diet for each timepoint.

2.4. Food Choice Assays

D. japonica planarians, from populations which has been fed on either liver or RML for 9 months, fasted for 4 days were manually selected to fall within a size range of 10 ± 2 mm. Four T-mazes were constructed on a 152 mm x 122 mm x 12.7 mm clear acrylic platform using a CNC milling machine based on a CAD model. Each T-maze was composed of a 60 mm stem and two 30 mm branches. T-mazes were filled with 3 mL of planarian water, and 6 worms were added to the base of each T-maze. First, two control runs were performed with each set of worms where worms were allowed to glide within the maze for 5 minutes without any food present. Next, the planarians were removed from the T-maze and RML and liver food pellets were submerged in separate arms of the T-maze. Creation of liver pellets was adapted from a standard protocol [

26]. A protocol for RML pellet preparation is reported in the Supplementary Methods. Once food was added, the same six worms were added back to the base of the T-maze and allowed to move for 5 minutes after which the number of worms in each section (left arm, middle, or right arm) were counted. Two independent experiments of six planarians each were performed for each diet. The location of each food source (i.e., left or right arm) was alternated between replicates. The number of worms who chose each food over the two independent experiments were summed, excluding planarians that did not make a choice (n=1 per diet), leading to a total n=11 per diet group. For each diet group, to determine if one food was preferred over the other compared to random choice, a chi-squared test was performed in R (4.5.0,[

24]).

2.5. RNA-Sequencing

2.5.1. RNA Preparation and Sequencing

Planarians which had been maintained on their respective diet for over a year were fasted 8 days prior to being frozen in -80 °C. One frozen D. japonica was homogenized per sample in TRIzol (Invitrogen) and total RNA was extracted following standard TRIzol Reagent Guide. Extracted RNA underwent DNase treatment using the TURBO DNase kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Three samples were prepared for each diet. The quality of the RNA extraction was first assessed on an agarose gel and confirmed via Agilent TapeStation system, yielding RNA Integrity Numbers of 10 for all samples. Sequencing libraries preparation was performed by Admera Health (South Plainfield, NJ) using the NEBNext Ultra II Directional with PolyA Selection kit. RNA-sequencing was performed by Admera Health using an Illumina NovaSeq X plus platform. The prepared libraries were 150 base pair pair-end sequences with a read depth of 40 million pair-end reads per sample. Accession numbers for RNA-sequencing samples will be provided during review.

2.5.2. Bioinformatic Analysis

We utilized “

https://scidap.com/ (accessed on 7 April 2025)”, a user-friendly bioinformatics platform for RNA sequencing data analysis. Since 80% of the

D.

japonica genome is made up of repeated sequences [

27] and individuals accumulate an unusually large number of somatic mutations during asexual reproduction [

28], establishing a reliable reference genome is extremely difficult. Although a whole-genome sequence of

D.

japonica was recently published [

29], RNA-seq reads achieved greater mapping to a reference transcriptome [

30], which was used for all downstream analyses.

The samples were run through the Kallisto transcript quant pipeline paired end 5.0.0 workflow with default parameters through the SciDAP software. First, adapters were trimmed from the FASTQ files and low-quality reads were filtered with TrimGalore. The filtered reads were psuedoaligned against the PlanMine 3.0 dd_Djap_v4 reference transcriptome [

30], with gene annotations provided by SciDAP. Custom annotations were performed using BLASTx against the UniProt database across various organisms. Filtering was performed to take the top hit based on bit score and only retain those with a bit score > 50. Out of 74909 transcripts, 66499 had at least 1BLASTx result and 28896 remained after filtering. The output of BLASTx contained protein IDs which were transformed to Gene and REFseq IDs using the ID mapping tool from UniProt (

https://www.uniprot.org/id-mapping). The aligned reads were subsequently quality assessed, sorted and indexed.

Using the read counts output from the Kallisto transcript quant pipeline paired end 5.0.0 workflow, quantitative differential expression analysis between liver-fed and RML-fed D. japonica was performed by the DESeq 11.0.0 pipeline workflow using default parameters through the SciDAP software. Differentially expressed genes were defined as having log2 Fold-Change (LFC)> +/- 0.59 and padjusted <0.05. Using the GSEApy – Gene Set Enrichment Analysis in Python workflow in SciDAP, we performed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) using the H_hallmark_gene_sets and default parameters.

2.6. Chemical Screening

2.6.1. Chemical Preparations and Exposure

Chemical information is provided in

Table 1. All chemicals were provided by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Stock solutions of diazinon and fluoxetine were prepared at 200X of the highest test concentration in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) then diluted to the final 1X with planarian water right before exposure. As a solvent, DMSO was used at final concentration of 0.5% in all test concentrations, a level which does not cause behavioral or morphological effects in

D.

japonica [

31]. As a test chemical, DMSO was diluted directly in planarian water.

Planarians which had been fed on their respective diet for at least 6 months were used. Planarians were exposed to chemicals in a 48-well tissue culture-treated polystyrene plates (Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA), with each well containing 1 planarian in 200 μL of chemical solution. Adult and regenerating planarians were tested in separate plates. Regenerating planarians were amputated pre-pharyngeally with an ethanol-sterilized razor blade within 2 hours of chemical addition.

All chemicals were screened over 5 concentrations (

Table 1) plus a solvent control (0.5% DMSO or planarian water), with each row of the 48-well plate consisting of one concentration (n = 8). Plates were sealed with thermal film (Excel Scientific, Victorville, CA, USA) immediately after addition of chemicals. Technical triplicates were run for all chemicals (total n = 24 per concentration), and following established protocols, a rotating orientation of chemical concentration in the plate rows was used to account for edge effects when screening [

7]. Two independent experiments (n=24 each) were conducted with planarians from each diet group to determine whether effects from diet were within the noise levels of repeated testing.

2.6.2. Behavioral Screening

Effects on lethality and various planarian behaviors (locomotion, phototaxis, and noxious heat sensing) were assessed on days 7 and 12 of exposure using established procedures with a previously described automated screening platform [

7,

19,

32,

33]. These time points allow for evaluation of sub-chronic effects both during active regeneration (day 7) and following return to an adult-like state (day 12) [

7] to determine the temporal effects of chemical exposure.

2.6.3. Statistical Analysis for Chemical Screening

2.6.3.1. Lowest-Observed-Effect-Levels (LOELs)

Statistical analysis was performed on compiled data of all individuals from the triplicate runs (

n = 24) in R (Version 4.5.0) [

24]. Each concentration was compared with its vehicle control population as previously described [

7,

34]. Except for lethality, only sublethal concentrations were analyzed. For lethality, stickiness, phototaxis, and scrunching endpoints, statistical significance was determined using a one-tailed Fisher’s exact test, with p-value adjustment for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. For speed and noxious heat sensing endpoints where sample distributions are normal, a Welch’s ANOVA was performed followed by a Tamhane-Dunnett’s post hoc test. For resting and anxiety where the sample distribution is non-normal, statistical significance was determined by performing a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a many to one Dunn’s post hoc test. For locomotor bursts where the sample distribution is over dispersed, a negative binomial generalized linear model followed by a Dunnett’s post hoc test was used to determine statistical significance. LOELs indicate the lowest concentration with a statistically significant hit. We evaluated both all statistically significant hits and only those considered concentration-dependent by filtering out concentration-independent hits which may not be biologically meaningful to remove potential false positives. The compiled scores and their associated p-values are provided in File S1.

2.6.3.2. Benchmark Concentrations (BMCs)

As an alternative approach to determine hit calls and potency, we calculated the BMCs, a modeled concentration exceeding a defined benchmark response (BMR), for every chemical and readout. Readout scores were pre-processed and normalized as previously described [

32,

33] using MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA). The preprocessed data were input into R (Version 4.5.0) [

24] and BMCs were calculated using the Rcurvep package [

35] as described in [

33]. BMRs calculated from existing data from a large chemical library screen were used (

Tables S1 and S2). BMCs are reported as the median BMCs calculated from n=1000 bootstrapped concentration-response curves. The lower and upper limits (5

th and 95

th percentile, respectively) of the BMC and associated hit confidence scores are listed in File S2. A readout was considered a hit if the hit confidence score exceeded 0.5. Some endpoints can have bidirectional changes in response and thus for these BMCs were calculated for each direction separately.

2.7. RNA interference (RNAi)

Double stranded RNA was synthesized using the Invitrogen MEGAScript kit (Thermo Scientific #AM1333) as instructed in the manual. After the transcription step, the manual’s isopropanol precipitation protocol was utilized, though omitting the use of phenol/chloroform.

D. japonica were fed liver or RML pellets containing 2 µg/µl

D. japonica Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 (

Djtrpaa) dsRNA or

Caenorhabditis elegans unc22 dsRNA, food coloring and 2% agarose. Planarians were fed three times over the course of 7 days. To test for the a knockdown, planarians were exposed to 100 μM Allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) (Sigma Aldrich), which induces scrunching through the

DjTRPAa channel [

36]. AITC was prepared fresh in planarian water. Worms were pipetted into a 100 mm petri dish containing 25 mL of 100 μM AITC solution. Five worms per condition were recorded at a time for bulk video recordings and experiments were repeated 2 times. Image sequences were recorded with a FLIR Flea3 model FL3-U3-13E4M USB3 camera equipped with a 25 mm lens (Tamron, Edmund Optics) using Point Grey FlyCapture 2 software. The camera was attached to a ring stand and recorded the planarians in the petri dish that was placed on a LED light panel (Tracer A4 LED Light Box, Amazon).

3. Results

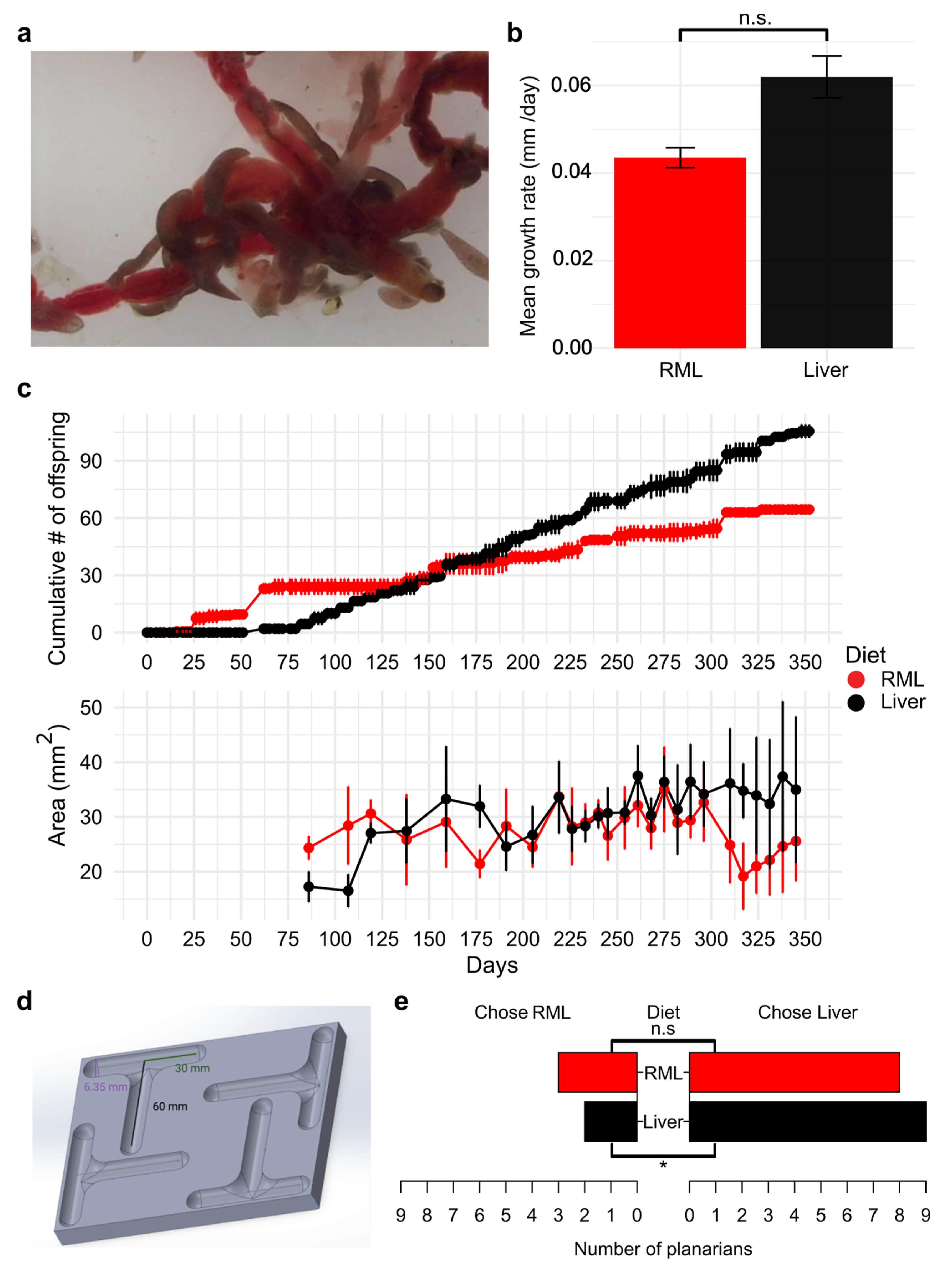

3.1. Planarians Can Be Maintained Long-Term on an RML Diet

We presented

D.

japonica planarians that were reared on liver for over a decade in our laboratory with commercially available frozen RML and found that they readily consumed RML (

Figure 1a). Other planarian species

(Dugesia dorotocephala,

Phagocata gracilis, asexual and sexual

Schmidtea mediterranea, and wild-caught planarians (Crum Creek, Swarthmore, PA)) were also tested. We confirmed that the planarians consumed RML by checking worms for a dark red coloration that is visibly distinct from unfed planarians. All tested species readily consumed frozen RML (

Figure S1a). Because of their dark black color, a color change could not be detected in

P. gracilis planarians; thus, we confirmed they consumed RML through observation that this species’ many pharnyges [

37] were attached to the RML (

Figure S1b). As we work primarily with

D. japonica planarians, we focused on further studying the effects of diet in this species.

Next, we asked whether regeneration capacity or kinematics were affected by diet. We amputated the heads of planarians raised on the two diets and monitored their head regeneration over the course of a week. We found no significant difference in the rate of blastema regeneration between planarians raised on the two diets (

p = 0.12) (

Figure 1b).

Because other attempts at feeding alternative diets have not be successful for maintaining long-term growth in planarians [

17], we first determined if

D. japonica planarians could be successfully maintained for a year on an RML mono diet and compared the number of offspring produced on either a RML or liver diet (

Figure 1c). A negative binomial generalized linear model revealed that the cumulative number of offspring increased over time in a diet-dependent manner (Diet x Days +0.0062, p = 0.0079) with liver feeding having a significant effect on increased divisions as days passed. We observed no significant effect for diet type (

p = 0.16) or days (

p = 0.38) alone. In addition to counting the number of offspring produced, we imaged planarians weekly to determine whether there were any differences in size that could explain slower growth in the RML-fed worms. Previous studies showed that a threshold size is necessary to fission [

38] and that worms that have a full gut don’t divide as frequently [

21]. Liver-fed worms showed a significant increase in size over time (Diet x Days interaction: +0.060 mm

2, p < 0.001) while the same was not observed for RML-fed worms (

p = 0.86). One-way ANOVA of deviance confirmed significant effects of diet (

F₁,₄₅₄ = 64.14,

p < 0.001), days (

F₁,₄₅₃ = 37.83,

p < 0.001), and their interaction (

F₁,₄₅₂ = 41.08,

p < 0.001), indicating that the growth rates were different between

D.

japonica fed on the two diets (

Figure 1c). However, overall worm sizes were similar within biological and experimental noise and the population growth of RML-fed worms remained sufficient for laboratory needs over the entire year.

3.2. Planarians Have a Mild Preference for Liver

Since planarians reproduce more quickly on a liver-diet, we hypothesized that planarians prefer liver over RML when given a choice. To assess which food source planarians prefer, we presented planarians fed on their respective mono diets for nine months with a choice of either liver or RML using a custom T-maze (

Figure 1d). Because liver disperses more rapidly in water and planarians display strong chemotaxis towards food, we prepared agarose pellets containing either homogenized liver or RML to standardize chemoattractant release (Supplementary Methods). In the absence of food, planarians randomly chose either arm of the T-maze (

Figure S2). Chi-square analysis revealed that liver-fed planarians chose liver pellets significantly more than RML pellets (

p = 0.03), while RML-fed planarians showed no significant differences in choice between the two foods (p=0.13) (

Figure 1e).

3.3. Gene Expression Differences Between Liver-Fed and RML-Fed D. japonica

After sustaining

D.

japonica on a RML mono diet for over a year, we assessed whether dietary differences induced distinct gene expression using global RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on 3 worms from each diet. Principal component analysis (PCA) showed separation along PC1 (81% variance) while modest separation was observed with respect to PC2 (12% variance) (

Figure 2a). Differential gene expression analysis revealed that only 41 of 8740 genes (0.5%) identified by our RNA-seq experiment were differentially expressed (LFC >±0.59, p-adj <0.05) between liver-fed and RML-fed worms (File S3). Of the 41 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), 26 genes were downregulated while 15 were upregulated in RML-fed planarians (

Figure 2b). Despite the small number of DEGs, we hypothesized that broader functional differences might still be present. Subsequently, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the MSigDB Hallmark collection to identify enriched shifts in gene expression. This analysis revealed that 10 gene sets were enriched in RML-fed worms, with the greatest changes in E2F Targets, G2M checkpoint, and MTORC1 Signaling, and that 1 gene set, Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-βeta Signaling, was enriched in liver-fed worms at a false discovery rate (FDR) < 25% (

Figure 2C, File S4).

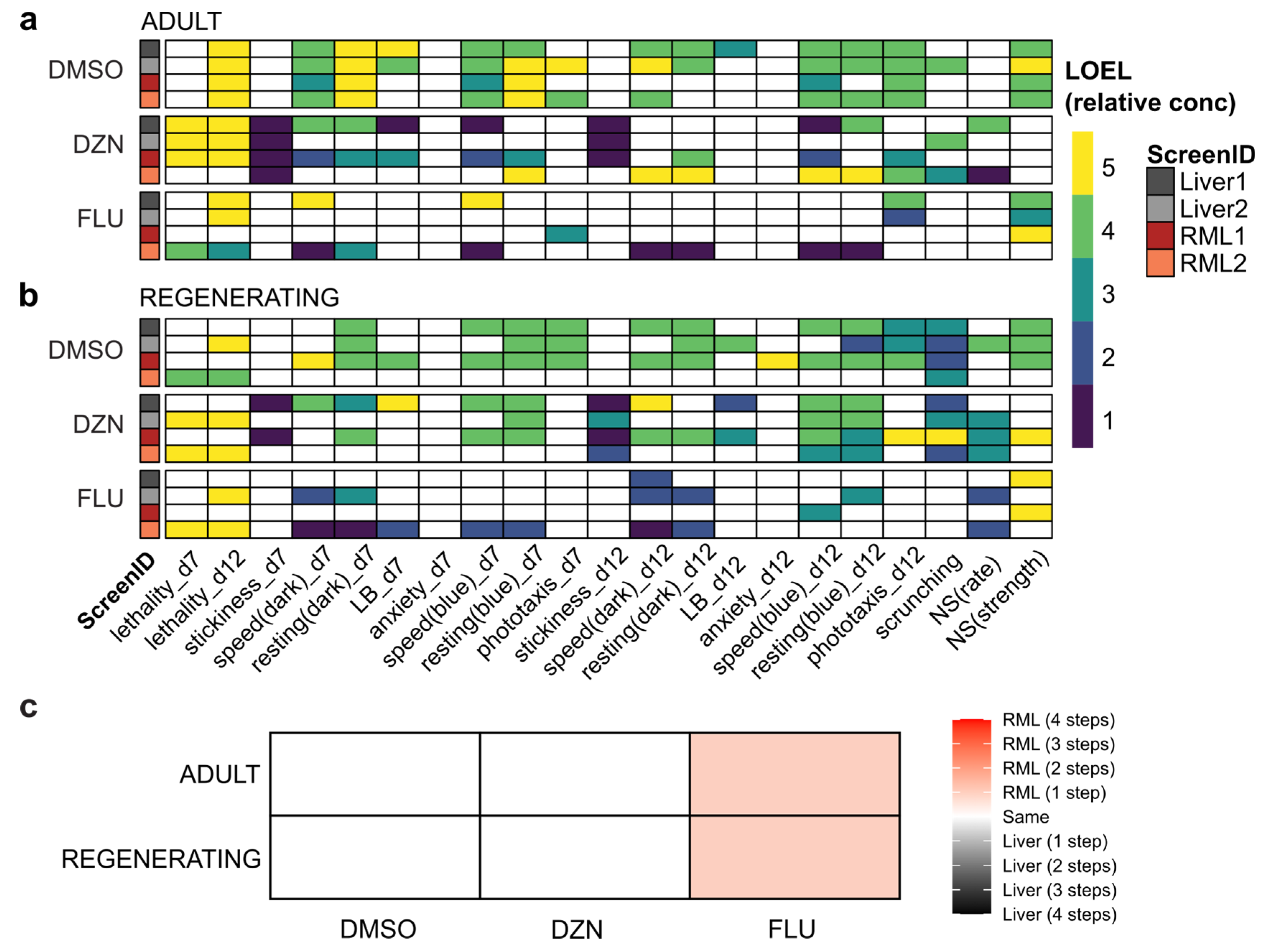

3.4. RML-Fed Planarians Are Suitable for High-Throughput Chemical Screening

Because we had found some transcriptomic changes with the different diets, we sought to evaluate whether those diet-induced changes would impact sensitivity in response to chemical exposure. To this end, we screened three compounds: the solvent DMSO, which has been extensively tested in planarians [

19,

31,

39,

40], diazinon, an organophosphorus pesticide which inhibits planarian cholinesterases [

41,

42] and causes behavioral effects in adult and regenerating

D.

japonica [

43], and fluoxetine, an antidepressant which we have found to cause behavioral effects in both acute [

32] and chronic exposure in

D.

japonica [

34]. Each chemical was tested at 5 concentrations in both intact/adult planarians and regenerating tail pieces. To determine if differences between chemical screens of planarians fed liver in comparison to planarians fed RML were due to diet or due to inherent noise between screenings, we conducted two rounds of screening for both diets, corresponding to their ScreenID: Liver1, Liver2, RML1, or RML2. Liver1 and RML1 were performed simultaneously while the other two screens were performed within several weeks of the first screen.

We compared the LOELs for the 3 chemicals for both adult (

Figure 3a) and regenerating planarians (

Figure 3b) across the different screens. All chemicals caused behavioral effects in adult and regenerating planarians at sublethal concentrations, in agreement with published data [

19,

31,

33,

34]. We observed variability in readout-specific bioactivity both across different diets, but also within the two experiments using the same diet. DMSO elicited the most robust per-readout results between individual screens and fluoxetine yielded the most variable results.

We quantified readout concordance across screens as the occurrence of a statistically significant hit for the same chemical at the same behavioral readout in both screens or lack of effects in both screens (

Figure S3a). Inter-screen variability was independent of diet. For example, both of the RML screens shared greater concordance with Liver1 and Liver2 than with each other in both adults and regenerating tails. Additionally, for regenerating tails, the Liver2 screen shared the greatest concordance with the RML2 screen while the results of the Liver1 screen was most similar to RML1. The lowest per readout concordance (39.7%) was observed for regenerating tails between RML1 and RML2. Fluoxetine was the primary driver for the low concordance, as seen in

Figure 3b which shows many hits for RML2 but only 2 hits for RML1. Notably, the same trend was true for fluoxetine when comparing Liver1 and 2 for regenerating tails. Readout concordance was even lower if concentration-independent hits were also included (

Figures S3b and S4). While biologically plausible, concentration-independent hits are more likely to be false positives, which may reflect the greater variability seen across screens.

When considering the minimum LOEL across all readouts for both screens with each diet, RML-fed planarians showed increased sensitivity to fluoxetine at one lower concentration step than seen with liver-fed planarians (

Figure 3c). For DMSO and diazinon, liver-fed and RML-fed worms displayed the same level of chemical sensitivity.

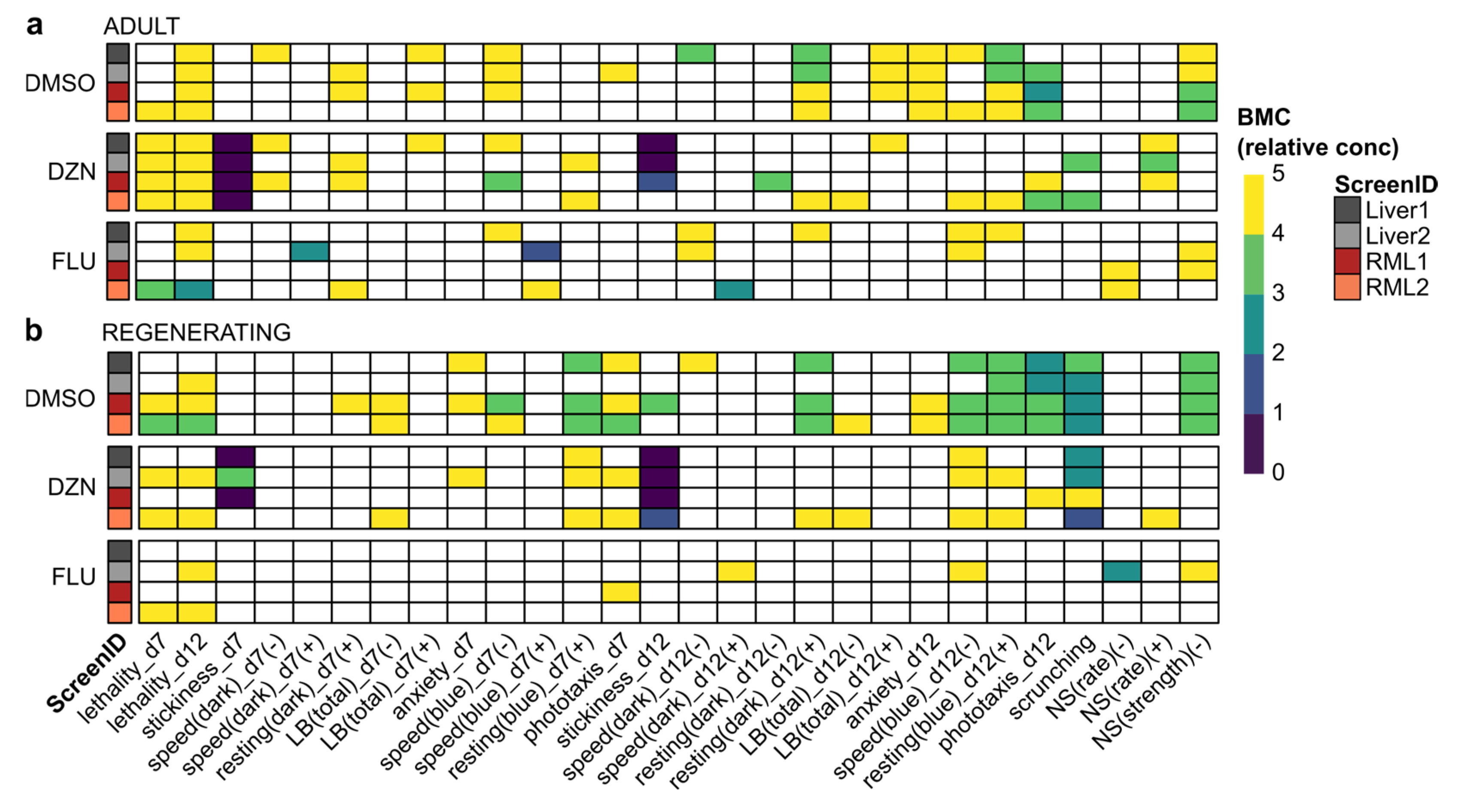

Notably, because of the few chemicals tested in each condition for this screen, we could not apply biological relevance cut-offs as in our typical analysis pipeline [

7]. Thus, the data shown in

Figure 3 is based on statistical hits only, which we have shown are not robust to inter-worm variability [

7]. Therefore, we also determined statistical significance and potency using BMC modeling. Unlike LOELs, which depend on the exact concentrations tested and don’t consider concentration-response relationships, BMCs are calculated from regression analysis of the concentration-response curves and allow for prediction of concentrations that will exceed a determined threshold (BMR). We used BMRs from an 112 chemical library screen that was conducted around the same time as this screen and verified that the distributions of control behaviors was not significantly different (

Figure S5), justifying this approach. Because of the fixed threshold levels, BMCs allow for comparisons at the same effect level, whereas statistical significance can be achieved with different effect sizes depending on the variability of the control and test populations. BMC analysis generally identified fewer hits than LOEL analysis (

Figure 4). This was especially true for regenerating planarians exposed to fluoxetine. This is because many of the low concentration hits seen with fluoxetine with LOEL analysis were hyperactive responses with flat or U-shaped response curves (

Figure S6), which are difficult to pick up with the specific dose-response modeling using in this BMC analysis pipeline [

35].

Readout concordance between screens was overall higher with BMC analysis than LOEL analysis, ranging from 69.7-85.9% in adult planarians and 74.7-87.9% in regenerating planarians (

Figure S3c). As with LOEL analysis, the highest concordance was not always between screens of the same diet type. To compare potency differences across diets, we identified the minimum BMC (BMC

min) across all readouts for each diet and worm type (

Table 2). For DMSO and DZN, the BMC

min was the same or very similar in both diets. The BMC

min did differ considerably for fluoxetine across diets, with an order of magnitude difference in potency in regenerating tails. Notably, the increased fluoxetine sensitivity in the liver-fed regenerating tails was driven by a hit in a single readout (NS(rate) (+)) in the Liver2 screen.

3.5. The RML Diet Is Suitable for Mechanistic Studies in Planarians

Any new food source replacing liver needs to be amenable to RNA interference (RNAi) by feeding as this is the primary mode of studying gene function in planarians [

26]. Therefore, we tested the utility of the RML diet in RNAi applications by comparing the ability of RML pellets to deliver double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and induce a well-defined knockdown phenotype comparable to standard liver pellets. Allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) is known to activate DjTRPAa, the planarian homolog of the Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) in

D.

japonica [

36]. When wildtype planarians are exposed they elicit an escape response called scrunching where the flatworm periodically changes its body via elongation and contraction cycles [

44]. When TRPA1 is successfully knocked down, planarians will glide instead of scrunch when exposed to AITC [

36,

45]. We fed

D. japonica planarians

Djtrpaa dsRNA using either liver or RML pellets and compared the resulting behavioral responses to worms fed

unc-22 dsRNA, which targets a

C. elegans gene with no planarian homolog. Behavioral recordings showed that both liver- and RML-pellets successfully induced

Djtrpaa knockdown, as evidenced by RNAi planarians gliding in AITC solution (Video S1,

Table 3).

4. Discussion

4.1. A RML Mono Diet Can Sustain D. japonica Planarians for at Least 1 Year with Minimal Physiological Changes Compared to a Liver Diet

Our findings demonstrate that RML are a viable alternative mono diet to liver for sustaining laboratory cultures of

D.

japonica. Other planarian species also readily consumed RML but their long-term response was not evaluated here. RML present the benefits of a commercially available food source that is easy to acquire and requires no preparation. Another advantage of RML is that the husks that remain after feeding are easy to clean up and do not cloud the water as easily as liver remnants. Additionally, the replacement of a vertebrate diet with an invertebrate diet aligns with efforts in toxicology and pharmacology to replace mammalian-derived components, such as fetal bovine serum in

in vitro studies [

46], to increase sustainability and reproducibility. Bovine-derived products have been known to be subject to seasonal and geographic variation, introducing variability in experiments within and between laboratories [

46].

D. japonica were successfully maintained for 1 year on a RML mono diet with minimal physiological changes compared to liver-fed worms. RML-fed planarians retained the ability to fully regenerate their heads at similar rates to liver-fed planarians, supporting the use of RML-fed worms in regeneration studies. Future experiments to visual planarian stem cell division post-feeding [

17,

47] using antibodies against phosphorylated histone 3 could be used to directly compare cell proliferation rates between worms raised on either diet. While liver-fed worms exhibited faster population growth (number of offspring over time), RML-fed individuals maintained stable sizes and reproduced successfully across a year-long period. It is possible that liver is more easily digested than RML and thus RML-fed planarians divided less frequently because having a full gut impedes fission [

21]. In support of this idea, we observed two big increases in the number of offspring produced by RML-fed worms over the holidays, when planarians were fed and handled less frequently. Thus, the slower population growth seen in RML could possibly be mitigated by fewer feedings. Another option is that RML are low on certain nutrients that facilitate growth and thus may need to be supplemented with additional invertebrate food sources to achieve the right nutritional balance.

Modest transcriptomic differences were found between planarians fed either diet. Only 0.5% of detected transcripts were differentially expressed between liver-fed and RML-fed worms, suggesting that global transcriptome profiles are largely conserved across these dietary conditions in

D.

japonica. The small number of DEGs should be interpreted in the context of several biological and technical limitations. First, planarians, including

D.

japonica, are not yet a fully established model system across molecular biology. Many species lack reliable reference genomes, and these genomes are not completely annotated. While a

D. japonica reference genome has been published [

29], our analyses achieved more robust mapping using a reference transcriptome [

30], which may have limited our ability to detect all transcriptional changes across diets. Additionally, the GSEA hallmark gene sets are largely derived from human datasets and may not accurately reflect conserved biological function in planarians. Future studies that increase RNA-seq sample size, expand functional annotations, and incorporate planarian-specific gene sets will provide a more complete picture of diet-dependent changes in planarians at the molecular level.

4.2. A RML Diet Is Suitable for Chemical Screening and Mechanistic Studies

Both adult and regenerating planarians raised on a RML diet responded to DMSO, diazinon, and fluoxetine with changes in behavior with some differences in potency seen across diets. Other variables, such as chemical stock variability, variability in pipetting small volumes, worm size, time of screening, and food batch variability could also affect inter-screen reproducibility. For example, Liver1 and RML1 were performed simultaneously using the same chemical stock solutions and were more similar to each other than to their respective diet replicate which used independent chemical stock solutions. To contextualize the results and better understand how the differences we observed between the duplicate screens were affected by diet versus these other variables, we compared the results obtained here to published data from other screens.

DMSO has previously been tested in regenerating planarians using similar assays and LOEL analysis [

19]. The current screen showed that regenerating planarians in both diets had LOELs of 0.5%, slightly lower than the previously reported 1% [

19]. Notably, the more sensitive hits were only seen in one screen from each diet and were not detected with BMC analysis, which had BMC

min of 0.79% in both diets, suggesting they may not be robust hits. Fluoxetine had previously been tested with the same behavioral platform using LOEL analysis [

34]. We found that planarians raised on both diets showed increased sensitivity for adults in the current screen (LOEL of 0.1 (RML) / 0.316 (liver) µM vs. 3.16 µM [

34]) and comparable sensitivity for regenerating worms (LOEL of 0.1 (RML) / 0.316 (liver) µM vs. 0.316 µM [

34]) when only considering concentration-dependent hits. We also compared the results for diazinon from this screen to existing data using BMC analysis [

33]. Previously, we found a BMC

min of 0.22 µM for adult planarians and 9.15 µM for regenerating planarians [

33]. The values we found in the current screen are slightly higher for adult planarians but lower for regenerating planarians at 1 µM in both worm types, independent of diet type. Stickiness was the most sensitive readout in both these and the published data [

33]. Thus, for all chemicals tested inter-screen variability in chemical sensitivity is on par or higher than the variability induced by changing diets.

When looking at a per-readout basis, variability differed across readouts, chemicals and statistical methods. Fluoxetine showed the greatest per readout variability across the three chemicals tested, driven by the presence of hyperactive hits at low concentrations, which were not always detected in every screen, especially due to their non-monotonic dose response (compare

Figure 3 and

Figure S4). Notably low concentration hyperactive effects were also previously observed in regenerating planarians [

34], and would be expected due to fluoxetine’s use as an antidepressant [

43] and thus are not necessarily false positive but can be particularly challenging to identify robustly. This was especially true for BMC analysis, which often is less sensitive but provides greater confidence in hit detection [

48]. As a result, readout concordance was much greater with BMC vs LOEL analysis. We do not yet fully understand the biological significance of hits for individual readouts. Thus, in depth analysis of readout information content and robustness will be necessary once diet has been better controlled.

4.3. Further Considerations to Optimize Planarian Diet

The data presented here demonstrate that RML is a viable food source for long-term

D. japonica planarian maintenance and is suitable for various types of planarian studies. Additionally, we showed that RNAi is possible using RML pellets and provide the protocol for this method in the Supplemental Methods, so other laboratories can also apply it. While this study shows that RML is a viable long-term diet, further considerations are warranted. Organic liver was originally chosen as a food source for planarians because it is nutrient rich and to reduce exposure to xenobiotics such as growth hormones, antibiotics, heavy metals or pesticides. RML are typically farmed to be sold as fish food and thus are less regulated than food aimed at human consumption and may contain contaminants t. For example, one study that investigated

Chironomidae larvae from various sources (not used in this study) showed that some samples contained excess levels of lead [

49]. Thus, a comparative analysis of the composition and identification of potential contaminants across various brands of RML will be necessary to identify the best source. Further, a mono diet consisting of RML may not be the most nutritionally balanced and may not be able to sustain planarian populations for decades, as is the case for liver. Thus, it is worth exploring additional invertebrate food sources, either to substitute RML or be used in combination with RML. Ideally, one could fully control the planarians’ diet by feeding them a synthesized food, based on analysis of the nutrient composition of liver. While this has already been attempted, it has unfortunately not yet been successful for long-term planarian husbandry [

17].

5. Conclusions

RML provide a practical and ethically preferable alternative to calf and chicken liver diets. To our knowledge, this is the first study to propose an alternative diet to liver that is able to sustain planarians long-term. The pilot screen from this study supports using an RML diet for toxicology studies and mechanistic research in D. japonica, reducing a barrier in culturing planarians and increasing accessibility of this emerging invertebrate model system. While liver remains the gold standard for maximum growth of laboratory cultures, we support and encourage the use of RML and the exploration of other invertebrate diets in laboratories seeking reproducible and ethically grounded research for planarians.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary Methods: RML pellet preparation; Figure S1: Various species of planarians consume RML; Figure S2: Side preference of D. japonica planarians in a T-maze in the absence of food; Figure S3: Readout concordance across different statistical methods; Figure S4: Behavioral screening results are robust to the RML diet, when considering all hits; Figure S5: Benchmark responses (BMRs) are appropriate for this dataset; Figure S6: Example of fluoxetine non-monotonic dose response; Table S1: BMRs for binary endpoints; Table S2: BMRs for continuous endpoints; File S1: Compiled readout scores and p-values used for lowest-observed-effect-level analysis; File S2: Benchmark concentration (BMC), confidence intervals and hit scores for all readouts in adult and regenerating planarians from each screen; File S3: Output from DESeq2 analysis; File S4: Output from Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) ; Video S1: Benchmark concentration (BMC), confidence intervals and hit scores for all readouts in adult and regenerating planarians from each screen.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E-M.S.C. and D.I.; methodology, E-M.S.C., J.S., K.S., E.C.; software, D.I. and J.P.; validation, J.P. and D.I.; formal analysis, J.P. and D.I.; investigation, J.P., E.C., J.S., K.S.; resources, E-M.S.C.; data curation, J.P. and D.I.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P., D.I., and E-M.S.C; writing—review and editing, D. I., E-M.S.C., J.P.; visualization, J.P, D.I., E.-M.S.C.; supervision, E-M.S.C.; project administration, E-M.S.C.; funding acquisition, E-M.S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15ES031354 (to E-M.S.C). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Raw RNA-sequencing reads will be deposited during review. All other data has been provided as supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Winnie Lin for help with the molecular biology experiments and pellet making, Natali Campillo for help with the molecular biology experiments, Gustav Allotey for help with the head regeneration assays, Christina Rabeler for help with the behavioral screening and molecular biology experiments, and Diamonte Agosto, Kiran Mahurkar, and Johanny Przybyla for help with animal care and imaging for population statistics. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, J.P. used ChatGPT 5.0 for the purposes of debugging R scripts to generate figures. Statistical tests or data were not edited by GenAI. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

E-M.S.C. is the founder of Inveritek, LLC, which offers planarian high throughput screening commercially. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NAM |

New Approach Methodology |

| RML |

Red Midge Fly Larvae |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DZN |

Diazinon |

| FLU |

Fluoxetine |

| LOEL |

Lowest Observed Effect Level |

| BMC |

Benchmark Concentration |

| RNAi |

RNA Interference |

| BMR |

Benchmark Response |

| AITC |

Allyl isothiocyanate |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| DEGs |

Differentially expressed genes |

| FDR |

False discovery rate |

| GSEA |

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| DjTRPAa |

Dugeisa japonica Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 |

| LB |

Locomotor bursts |

| NS |

Noxious stimuli |

References

- Ivankovic, M.; Haneckova, R.; Thommen, A.; Grohme, M.A.; Vila-Farré, M.; Werner, S.; Rink, J.C. Model Systems for Regeneration: Planarians. Development (Cambridge) 2019, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttarelli, F.R.; Pellicano, C.; Pontieri, F.E. Neuropharmacology and Behavior in Planarians: Translations to Mammals. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2008, 147, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrià, F. Regenerating the Central Nervous System: How Easy for Planarians! Dev Genes Evol 2007, 217, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, K.G.; Currie, K.W.; Pearson, B.J.; Zayas, R.M. Nervous System Development and Regeneration in Freshwater Planarians. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireland, D.; Collins, E.S. Planarians as a Model to Study Neurotoxic Agents. In Advances in Neurotoxicology; Alternative Methods in Neurotoxicology; Elsevier Inc., 2023; Vol. 9, Alternative Methods in Neurotoxicology; pp. 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, D.; Collins, E.-M.S. New Worm on the Block: Planarians in (Neuro)Toxicology. Current Protocols 2022, 2, e637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hagstrom, D.; Hayes, P.; Graham, A.; Collins, E.-M.S. Multi-Behavioral Endpoint Testing of an 87-Chemical Compound Library in Freshwater Planarians. Toxicol Sci 2019, 167, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, G.; Stocchi, F.; Margotta, V.; Ruggieri, S.; Bravi, D.; Bellantuono, P.; Palladini, G. A Pharmacological Study of Dopaminergic Receptors in Planaria. Neuropharmacology 1989, 28, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttarelli, F.R.; Pontieri, F.E.; Margotta, V.; Palladini, G. Acetylcholine/Dopamine Interaction in Planaria. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Toxicology & pharmacology : CBP 2000, 125, 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, S.M.; Patil, T.; Tallarida, C.S.; Baron, S.; Kim, M.; Song, K.; Ward, S.; Raffa, R.B. Nicotine Behavioral Pharmacology: Clues from Planarians. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2011, 118, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, M.; Hattori, M.; Hosoda, K.; Sawamoto, M.; Motoishi, M.; Hayashi, T.; Inoue, T.; Umesono, Y. The Pharyngeal Nervous System Orchestrates Feeding Behavior in Planarians. Science Advances 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, S.; Sakurai, T. Food Ingestion by Planarian Intestinal Phagocytic Cells — a Study by Scanning Electron Microscopy. Hydrobiologia 1991, 227, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsthoefel, D.J.; Cejda, N.I.; Khan, U.W.; Newmark, P.A. Cell-Type Diversity and Regionalized Gene Expression in the Planarian Intestine. eLife 2020, 9, e52613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J.B. Further Studies on Feeding and Digestion in Triclad Turbellaria. The Biological Bulletin 1962, 123, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Farré, M.; C. Rink, J. The Ecology of Freshwater Planarians. In Planarian Regeneration: Methods and Protocols; Rink, J.C., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 2018; pp. 173–205. ISBN 978-1-4939-7802-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, M.R.P.; Duncan, E.M. Laboratory Maintenance and Propagation of Freshwater Planarians. Curr Protoc Microbiol 2020, 59, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, C.; Powers, K.; Gurung, G.; Pellettieri, J. Defined Diets for Freshwater Planarians. Developmental Dynamics 2022, 251, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legner, E.F.; Yu, H.S.; Medved, R.A.; Badgley, M.E. Mosquito and Chironomid Midge Control by Planaria. California Agriculture 1975, 29, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, D.; Bochenek, V.; Chaiken, D.; Rabeler, C.; Onoe, S.; Soni, A.; Collins, E.-M.S. Dugesia Japonica Is the Best Suited of Three Planarian Species for High-Throughput Toxicology Screening. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, D.; Coffinas, E.; Rabeler, C.; Collins, E.-M.S. Planarian Behavioral Screening Is a Useful Invertebrate Model for Evaluating Seizurogenic Chemicals 2025.

- Dunkel, J.; Talbot, J.; Schötz, E.-M. Memory and Obesity Affect the Population Dynamics of Asexual Freshwater Planarians. Phys. Biol. 2011, 8, 026003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillo, N.; Ireland, D.; Patel, Y.; Collins, E.-M.S. A Simple Method for Quantifying Blastema Growth in Regenerating Planarians. Curr Protoc 2023, 3, e684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji - an Open Source Platform for Biological Image Analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2021.

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S; Fourth.; Springer: New York, 2002; ISBN 0-387-95457-0. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, N.; Agata, K. RNA Interference in Planarians: Feeding and Injection of Synthetic dsRNA. In Planarian Regeneration: Methods and Protocols; Rink, J.C., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 2018; pp. 455–466. ISBN 978-1-4939-7802-1. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Kawaguchi, A.; Zhao, C.; Toyoda, A.; Sharifi-Zarchi, A.; Mousavi, S.A.; Bagherzadeh, R.; Inoue, T.; Ogino, H.; Fujiyama, A.; et al. Draft Genome of Dugesia Japonica Provides Insights into Conserved Regulatory Elements of the Brain Restriction Gene Nou-Darake in Planarians. Zoological Lett 2018, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, O.; Hosoda, K.; Kawaguchi, E.; Yazawa, S.; Hayashi, T.; Inoue, T.; Umesono, Y.; Agata, K. Unusually Large Number of Mutations in Asexually Reproducing Clonal Planarian Dugesia Japonica. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0143525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Guo, Q.; Guo, Y.; Luo, L.; Kristiansen, K.; Han, Z.; Fang, H.; Zhang, S. Whole-Genome Sequence of the Planarian Dugesia Japonica Combining Illumina and PacBio Data. Genomics 2022, 114, 110293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanski, A.; Moon, H.; Brandl, H.; Martín-Durán, J.M.; Grohme, M.A.; Hüttner, K.; Bartscherer, K.; Henry, I.; Rink, J.C. PlanMine 3.0—Improvements to a Mineable Resource of Flatworm Biology and Biodiversity. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D812–D820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagstrom, D.; Cochet-Escartin, O.; Zhang, S.; Khuu, C.; Collins, E.-M.S. Freshwater Planarians as an Alternative Animal Model for Neurotoxicology. Toxicol Sci 2015, 147, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireland, D.; Rabeler, C.; Rao, S.; Richardson, R.J.; Collins, E.-M.S. Distinguishing Classes of Neuroactive Drugs Based on Computational Physicochemical Properties and Experimental Phenotypic Profiling in Planarians. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0315394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireland, D.; Zhang, S.; Bochenek, V.; Hsieh, J.-H.; Rabeler, C.; Meyer, Z.; Collins, E.-M.S. Differences in Neurotoxic Outcomes of Organophosphorus Pesticides Revealed via Multi-Dimensional Screening in Adult and Regenerating Planarians. Frontiers in Toxicology 2022, 4, 948455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayingana, K.; Ireland, D.; Rosenthal, E.; Rabeler, C.; Collins, E.-M.S. Adult and Regenerating Planarians Respond Differentially to Chronic Drug Exposure. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 2023, 96, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.H.; Ryan, K.; Sedykh, A.; Lin, J.A.; Shapiro, A.J.; Parham, F.; Behl, M. Application of Benchmark Concentration (BMC) Analysis on Zebrafish Data: A New Perspective for Quantifying Toxicity in Alternative Animal Models. Toxicological Sciences 2019, 167, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, Z.; Ho, A.; Ireland, D.; Rabeler, C.; Cochet-Escartin, O.; Collins, E.-M.S. Pharmacological or Genetic Targeting of Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Channels Can Disrupt the Planarian Escape Response. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0226104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Hunt Morgan; Schiedt, A.E. Regenerating in the Planarian Phagocata Gracilis. Biological Bulletin 1904, 7, 160–165. [CrossRef]

- Goel, T.; Ireland, D.; Shetty, V.; Rabeler, C.; Diamond, P.H.; Collins, E.-M.S. Let It Rip: The Mechanics of Self-Bisection in Asexual Planarians Determines Their Population Reproductive Strategies. Physical Biology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A.S.; Pirotte, N.; Plusquin, M.; Willems, M.; Neyens, T.; Artois, T.; Smeets, K. Toxicity Profiles and Solvent-Toxicant Interference in the Planarian Schmidtea Mediterranea after Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) Exposure. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2014, 35, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagán, O.R.; Rowlands, A.L.; Urban, K.R. Toxicity and Behavioral Effects of Dimethylsulfoxide in Planaria. Neuroscience Letters 2006, 407, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireland, D.; Rabeler, C.; Gong, T.; Collins, E.-M.S. Bioactivation and Detoxification of Organophosphorus Pesticides in Freshwater Planarians Shares Similarities with Humans. Archives of Toxicology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagstrom, D.; Zhang, S.; Ho, A.; Tsai, E.S.; Radić, Z.; Jahromi, A.; Kaj, K.J.; He, Y.; Taylor, P.; Collins, E.M.S. Planarian Cholinesterase: Molecular and Functional Characterization of an Evolutionarily Ancient Enzyme to Study Organophosphorus Pesticide Toxicity. Archives of Toxicology 2018, 92, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagstrom, D.; Hirokawa, H.; Zhang, L.; Radic, Z.; Taylor, P.; Collins, E.-M.S. Planarian Cholinesterase: In Vitro Characterization of an Evolutionarily Ancient Enzyme to Study Organophosphorus Pesticide Toxicity and Reactivation. Arch Toxicol 2017, 91, 2837–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochet-Escartin, O.; Mickolajczyk, K.J.; Collins, E.-M.S. Scrunching: A Novel Escape Gait in Planarians. Phys. Biol. 2015, 12, 056010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, O.M.; Zaharieva, E.E.; Para, A.; Vásquez-Doorman, C.; Petersen, C.P.; Gallio, M. Activation of Planarian TRPA1 by Reactive Oxygen Species Reveals a Conserved Mechanism for Animal Nociception. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20, 1686–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, L.M.; Sensbach, J.; Pipp, F.; Werkmann, D.; Hewitt, P. Increasing Sustainability and Reproducibility of in Vitro Toxicology Applications: Serum-Free Cultivation of HepG2 Cells. Front. Toxicol. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddien, P.W. The Cellular and Molecular Basis for Planarian Regeneration. Cell 2018, 175, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireland, D.; Word, L.J.; Collins, E.-M.S. Statistical Analysis of Multi-Endpoint Phenotypic Screening Increases Sensitivity of Planarian Neurotoxicity Testing. Toxicological Sciences 2025, kfaf117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifian Fard, M.; Pasmans, F.; Adriaensen, C.; Laing, G.D.; Janssens, G.P.J.; Martel, A. Chironomidae Bloodworms Larvae as Aquatic Amphibian Food: Bloodworms as Aquatic Amphibian Food. Zoo Biology 2014, 33, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).