Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Impact of Salt Stress on the Growth and Development of Pepper

3. Evaluation and Identification of Salt Tolerance Traits of Pepper

4. Research Advances Concerning the Salt Tolerance Mechanism of Pepper

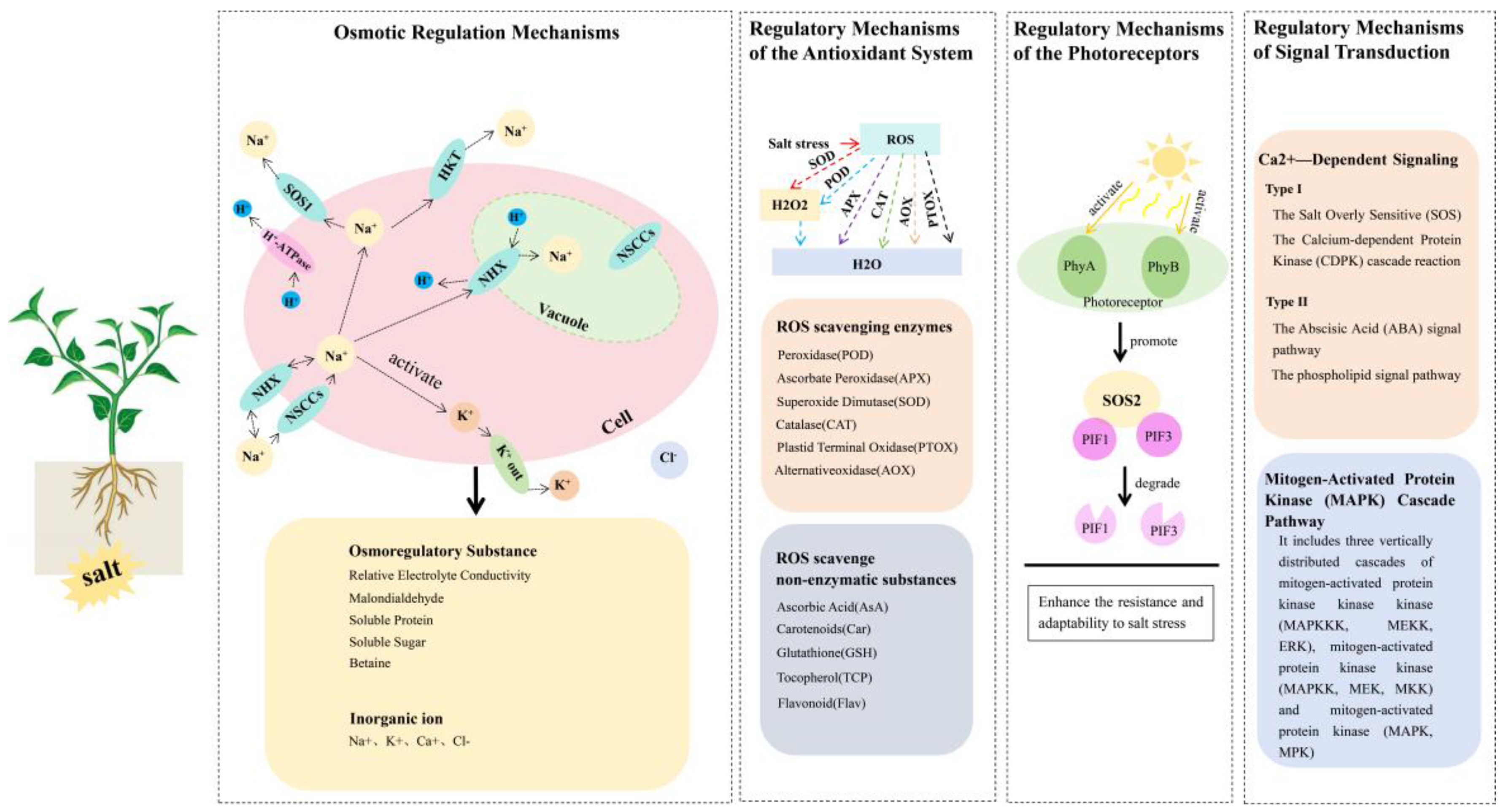

4.1. Osmotic Regulation Mechanisms

4.2. Regulatory Mechanisms of the Antioxidant System

4.3. Regulatory Mechanism of Photoreceptors

4.4. Regulatory Mechanism of Signal Transduction

4.4.1. Ca2+-Dependent Signaling Pathways

4.4.2. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Cascade Pathway

5. Research Advances in Salt Tolerance Genes Associated with Pepper

6. Research Advances in the development of Cultivation Techniques for Pepper Resistant to Saline–Alkali Soil

6.1. The Application of Relevant Salt Tolerance-Regulatory Substances

6.2. Application of the Grafting Techniques

6.3. Methods for Soil Improvement

7. Concluding Overview

8. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Machado, R.M.A.; Serralheiro, R.P.; Alvino, A.; Ferreira, M.I.F.R. Soil Salinity: Effect on Vegetable Crop Growth. Management Practices to Prevent and Mitigate Soil Salinization. Horticulturae 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Li, H.; Lu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, M.; Liang, J.; Meng, H. Physiological Responses of Three Tartary Buckwheat Varieties to Salt Stress and Evaluation of Salt Tolerance. Crops 2022, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, B.; Derakhshani, B.; Jung, K.-H. Recent Molecular Aspects and Integrated Omics Strategies for Understanding the Abiotic Stress Tolerance of Rice. Plants 2023, 12, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zied, H.; Tesfay, A.; DongGill, K.; Salem, B.; Jaehyun, L.; Wahida, G.; Yerang, Y.; Hojeong, K.; Kumar, J.M.; Arnab, B.; et al. Soil Salinity and Its Associated Effects on Soil Microorganisms, Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Crop Yield, Biodiversity and Desertification: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 843. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, W.-Y.; Yun, D.-J. A New Insight of Salt Stress Signalingin Plant. Mol. Cells 2016, 39, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sa-ren-gao-wa; Hu W. ; Jiang A. Research process in pharmacological function and products of chilli. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2012, 33, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Ma, Y.; Dai, X.; Li, X.; Yang, S. Spread and Industry Development of Pepper in China. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2020, 47, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Serrano, L.; Calatayud, Á.; López-Galarza, S.; Serrano, R.; Bueso, E. Uncovering Salt Tolerance Mechanisms in Pepper Plants: A Physiological and Transcriptomic Approach. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, T.K.; Krishna, R.; Ansari, W.A.; Aamir, M.; Kumar, P.; Kashyap, S.P.; Pandey, S.; Kole, C. Approaches Involved in the Vegetable Crops Salt Stress Tolerance Improvement: Present Status and Way Ahead. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 787292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S. Advancing the Comprehensive Utilisation of Saline-Alkali Land Making the Most of Saline-Alkali Land for Specialised Agriculture 2023, 11.

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Xu, R.; Guo, Y.; Zuan, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y. Effect of NaCl Stress on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Pepper. Mol. Plant Breed. 2024, 22, 5403–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.A. Seed Priming to Alleviate Salinity Stress in Germinating Seeds. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 192, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. , K.M.Iqbal.; Peter, P.; Tibor, J. Salicylic Acid: A Versatile Signaling Molecule in Plants. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Du, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhong, Q.; Liu, F.; Gui, M. Research Progress in the Adaptation of Hot Pepper(Capsicum annuum L.)to Abiotic Stress. Biotechnol. Bull. 2022, 38, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Li, S.; Yuan, X.; Cai, Z.; Gu, H.; Chen, X. High-salt Tolerance of Three Pepper Varieties(Capsicum annuum L.)by Salt Domestication. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2022, 34, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelke, D.B.; Pandey, M.; Nikalje, G.C.; Zaware, B.N.; Suprasanna, P.; Nikam, T.D. Salt Responsive Physiological, Photosynthetic and Biochemical Attributes at Early Seedling Stage for Screening Soybean Genotypes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 118, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Gao, L.; Peng, J.; Zhang, X. Salt Tolerance Evaluation of Three Pepper Varieties in Qiubei County. J. Baoshan Univ. 2020, 39, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Pang, S.; Ji, X.; Guo, X.; Shan, S.; Wang, H. Evaluation of Stress Resistance of Different Dried Pepper Varieties at Seed Germination Stage. North. Hortic. 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J.; Luo, G.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Hu, T. Analysis of the Resistance to NaCl Stress During Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of 2 Line Peppers. Seed 2016, 35, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Diao, W.; Pan, B.; Guo, G.; Yi, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, S. Salt Tolerance Difference and Evaluation of Different Capsicum Cultivars at Seed Germination Stage. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2020, 32, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Chang, X.; Yao, Q. Comprehensive Evaluation on Salt Tolerance of 100 Pepper Germplasm Resources and Screening Salt Tolerant Varieties. Shandong Agric. Sci. 2020, 52, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wan, H.; Wang, W.; Diao, W.; Wu, Y.; Zu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Mei, Y. Methodology and comparison of salt tolerance in pepper varieties. J. Zhejiang Agric. Sci. 2023, 64, 1177–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Salt tolerance and physiological, biochemical index responses of different pepper varieties under salt stress. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2023, 51, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Q. Effects of NaCl stress on chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics and physiological characteristics in seedlings of two pepper cultivars. Acta Agric. Zhejiangensis 2017, 29, 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, C.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Pan, B.; Guo, G.; Gao, C.; Chen, Y.; Diao, W. Ion Response of Different Tissues of Salt-tolerant Pepper Seedlings to NaCl Stress. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2023, 35, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zeng, H.; Huang, C.; Wu, L.; Ma, J.; Zhou, B.; Ye, D.; Weng, H. Noninvasive Detection of Salt Stress in Cotton Seedlings by Combining Multicolor Fluorescence-Multispectral Reflectance Imaging with EfficientNet-OB2. Plant Phenomics Wash. DC 2023, 5, 0125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ma, X.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Yao, Q. Effects of NaCl Stress on Physiological and Biochemical Indexes of Capsicum annuum L. Seedlings with Different Salt Tolerance. Shandong Agric. Sci. 2021, 53, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Guo, J.; Mei, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zu, Y.; Wang, W. Response of pepper seed germination and seedling physiological characteristics to salt stress. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2016, 44, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y. Salt Tolerance and PhysiologicalBiochemical Correspondence to SaltStress in Xianlajiao Chili Pepper. Master, Northwest A&F University, 2019.

- Li, X.; Shang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B. Evaluation of Salt Tolerance of Pepper Cultivars by Multiple Statistics Analysis. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2008, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C. Study on the Germination and Seedling Physiological, Biochemical Characteristics of Pepper under Salt tolerance. Master, Henan Institute of Science and Technology, 2012.

- Huang, T.; Zhang, R.; He, Y.; Yang, R.; Song, W.; Lai, Z.; Li, N.; Liu, S. Identification of NAC family members of Capsicum annuum and analysis on expressions of their coding genes under NaCl stress. J. Plant Resour. Environ. 2023, 32, 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Yao, M.; Yu, C.; Shen, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, N. Identification of LACS family genes in Capsicum annuum L. and their response to abiotic stress. J. Yangtze Univ. Sci. Ed. 2022, 19, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L, S.D.; Nydia, C.; S, F.J.F.; Trevor, R.; Devinder, S. Linking Genetic Determinants with Salinity Tolerance and Ion Relationships in Eggplant, Tomato and Pepper. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Aamer, M.; Liao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yao, F.; Zhu, B.; Gao, Z.; Cheng, C. Regulating Effect of Sodium Selenite Addition on Seed Germination and Growth of Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.) Under Mixed Salt Stress. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wen, L.; Zhang, Z. Effects of Salt Stress on the Physiological Characteristics of Two Pepper Genotypes. Mol. Plant Breed. 2022, 20, 1658–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Pardo, J.M.; Batelli, G.; Van Oosten, M.J.; Bressan, R.A.; Li, X. The Salt Overly Sensitive (SOS) Pathway: Established and Emerging Roles. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadam, H.; Saddam, H.; Basharat, A.; Xiaolong, R.; Xiaoli, C.; Qianqian, L.; Muhammad, S.; Naeem, A. Recent Progress in Understanding Salinity Tolerance in Plants: Story of Na+/K+ Balance and Beyond. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojórquez-Quintal, E.; Ruiz-Lau, N.; Velarde-Buendía, A.; Echevarría-Machado, I.; Pottosin, I.; Martínez-Estévez, M. Natural Variation in Primary Root Growth and K+ Retention in Roots of Habanero Pepper (Capsicum Chinense) under Salt Stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 2016, 43, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G, iuffrida; F,.Leonardi; Piero, C.L.; A,.R.Petrone; G,. Nitrogen Metabolism and Ion Content of Sweet Pepper under Salt and Heat Stress. Adv. Hortic. Sci. Riv. Dellortoflorofrutticoltura Ital.

- Apse, M.P.; Aharon, G.S.; Snedden, W.A.; Blumwald, E. Salt Tolerance Conferred by Overexpression of a Vacuolar Na+/H+ Antiport in Arabidopsis. Science 1999, 285, 1256–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penella, C.; Nebauer, S.G.; Quiñones, A.; San Bautista, A.; López-Galarza, S.; Calatayud, A. Some Rootstocks Improve Pepper Tolerance to Mild Salinity through Ionic Regulation. Plant Sci. Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 2015, 230, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.M.; Garrido, C.; Martínez, V.; Carvajal, M. Water Relations and Xylem Transport of Nutrients in Pepper Plants Grown under Two Different Salts Stress Regimes. Plant Growth Regul. 2003, 41, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Chancan, L.; Shuangshuang, Z.; Chongwu, W.; Yan, G. The Glycosyltransferase QUA1 Regulates Chloroplast-Associated Calcium Signaling During Salt and Drought Stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; Zheng, Q.; Pang, S.; Li, G. Effects of the continuous salt stress on the growth of Capscium. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2016, 34, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Wu, P.; Chen, B.; Zhao, L.; Pan, L.; Zhang, B.; Hu, C. Preliminary Study on the Effect of Sodium Salt Stress on the Tolerance of Pepper with Different Pungency Degree. J. Northeast Agric. Sci. 2021, 46, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojórquez-Quintal, E.; Velarde-Buendía, A.; Ku-González, Á.; Carillo-Pech, M.; Ortega-Camacho, D.; Echevarría-Machado, I.; Pottosin, I.; Martínez-Estévez, M. Mechanisms of Salt Tolerance in Habanero Pepper Plants (Capsicum Chinense Jacq.): Proline Accumulation, Ions Dynamics and Sodium Root-Shoot Partition and Compartmentation. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Pan, X.; Chen, N.; Hu, H.; Haq, S.U.; Khan, A.; Chen, R. CaDHN3, a Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.) Dehydrin Gene Enhances the Tolerance against Salt and Drought Stresses by Reducing ROS Accumulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C. Effects of Exogenous Trehalose and Glycine Betaine on the Growth of Aronia melanocarpa Seedlings under NaCl Stress. Master, Xinjiang Agricultural University, 2023.

- Zhu, R.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, H. Bioinformatics analysis of Capsicum superoxide dismutase gene family. J. Shihezi Univ. Sci. 2020, 38, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T. Study on physiological characteristics of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa salt tolerance. Master, Guangdong Ocean University, 2022.

- Feng, Z. Physiological changes and drought resistance of three edible rose cultivars under drought stress. Master, Ningxia University, 2023.

- Ma, L.; Han, R.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Fu, H.; Huo, Y.; Sun, L.; et al. Phytochromes Enhance SOS2-Mediated PIF1 and PIF3 Phosphorylation and Degradation to Promote Arabidopsis Salt Tolerance. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 2997–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, R.; He, L.; Hu, Z.; Liang, Y.; Lin, F.; Zhou, Y. Endophytic Fungus Falciphora Oryzae Enhances Salt Tolerance by Modulating Ion Homeostasis and Antioxidant Defense Systems in Pepper. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, M.; Liu, J.; Cai, J.; He, Y.; Zhao, W.; Liu, C.; Wu, Y. Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.) AP2/ERF Transcription Factor, CaERF2 Enhances Salt Stress Tolerance through ROS Scavenging. TAG Theor. Appl. Genet. Theor. Angew. Genet. 2025, 138, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.-H.; Zhang, H.-X.; Ali, M.; Gai, W.-X.; Cheng, G.-X.; Yu, Q.-H.; Yang, S.-B.; Li, X.-X.; Gong, Z.-H. A Small Heat Shock Protein CaHsp25.9 Positively Regulates Heat, Salt, and Drought Stress Tolerance in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. PPB 2019, 142, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guang, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Xiao, X.; Luo, S.; Zhou, Y. Characterization of Phytochrome-Interacting Factor Genes in Pepper and Functional Analysis of CaPIF8 in Cold and Salt Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 746517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C. Effects of NaCl Stress on Photosynthetic Characteristic of pepper. North. Hortic. 2010, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, H.; Trewavas, A.J.; Knight, M.R. Calcium Signalling in Arabidopsis Thaliana Responding to Drought and Salinity. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 1997, 12, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, D.; Mishra, S.; Bihani, S.C.; Seth, T.; Srivastava, A.K.; Pandey, G.K. Salt Stress Tolerance and Calcium Signalling Components: Where We Stand and How Far We Can Go? J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lan, H. Signal Transduction Pathways in Response to Salt Stress in Plants. Plant Physiol. J. 2011, 47, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Study on the function and regulatory mechanism of apple CaCA family in response to cold and salt stresses. Doctor, Northwest A&F University, 2023.

- Yanming, Z.; Jiaqi, Z.; Xuping, N.; Qinrui, W.; Yutian, J.; Xia, X.; Haoyang, W.; Peng, F.; Han, W.; Yan, G.; et al. Structural Basis for the Activity Regulation of Salt Overly Sensitive 1 in Arabidopsis Salt Tolerance. Nat. Plants 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Dong, Y.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, M.; Chen, T.; Wu, Y. The vital roles of abscisic acid signal transduction pathway in response to abiotic stress in plants. Chem. Life 2021, 41, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Studies on the mechanism of abscisic acid-priming for alkaline stress tolerance in rice. Doctor, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2020.

- Che, Y.; Yao, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Sun, G.; Zhang, H. Potassium Ion Regulates Hormone, Ca2+ and H2O2 Signal Transduction and Antioxidant Activities to Improve Salt Stress Resistance in Tobacco. Plant Physiol. Biochem. PPB 2022, 186, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanping, S.; Kan, Z.; Linjing, X.; Mingxing, Y.; Baixue, X.; Shuilin, H.; Zhiqin, L. The Pepper Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase CaMAPK7 Acts as a Positive Regulator in Response to Ralstonia Solanacearum Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Soongon, J.; Woo, L.C.; Chul, L.S. The Pepper MAP Kinase CaAIMK1 Positively Regulates ABA and Drought Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.W.; Jeong, S.; Lee, S.C. Differential Expression of MEKK Subfamily Genes in Capsicum Annuum L. in Response to Abscisic Acid and Drought Stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1822019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minchae, K.; Soongon, J.; Woo, L.C.; Chul, L.S. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase CaDIMK1 Functions as a Positive Regulator of Drought Stress Response and Abscisic Acid Signaling in Capsicum Annuum. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Un, H.S.; Gil-Je, L.; Hoon, J.J.; Yunsik, K.; Jin, K.Y.; Kyung-Hee, P. Capsicum Annuum Transcription Factor WRKYa Positively Regulates Defense Response upon TMV Infection and Is a Substrate of CaMK1 and CaMK2. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, L.C.; Chul, L.S. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of Raf-like Kinase Gene Family in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.; Jade, N. Specificity Models in MAPK Cascade Signalling. FEBS Open Bio 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenghua, G.; Fei, W.; Juntawong, N.; Ning, L.; Yanxu, Y.; Chuying, Y.; Chunhai, J.; Minghua, Y. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Defense-Related Genes and Pathways against Xanthomonas Campestris Pv. Vesicatoria in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). PloS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lv, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, W.; Song, J.; Yang, B.; Tan, F.; Zou, X.; et al. Comprehensive Phosphoproteomic Analysis of Pepper Fruit Development Provides Insight into Plant Signaling Transduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Genome-Wide Analysis, Expression Profile of SBP-BOX Gene Family and Characterization of CASBP11 and CASBP12 in Pepper(Capsicum annuum L.). Master, Northwest A&F University, 2016.

- Wang, Y.; Lin, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Ma, J. Cloning and Expression Analysis of CaNAC61 Gene in Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 32, 2502–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ruan, Y.; Gan, L. Identification and Expression Analysis of the B-box Transcription Factor Family in Pepper. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2021, 48, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Pei, Y.; Chen, L.; Ul Haq, S.; Lu, M.; Gong, H.; Chen, R. Pepper bHLH Transcription Factor CabHLH035 Contributes to Salt Tolerance by Modulating Ion Homeostasis and Proline Biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, C.; Shi, G.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Expression Characteristics and Functions of CaPIF4 in Capsicum annuum Under Salt Stress. Biotechnol. Bull. 2024, 40, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; J, N.R.; C, L.; M, C.T. Enhanced Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Pine Expressing the Pepper CaPF1 Gene Is Associated with the Polyamine Biosynthesis. Plant Cell Rep. 2007, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Hoon, S.K.; Chul, L.S.; Won, J.H.; Kyu, H.J.; Kook, H.B. Expression and Functional Roles of the Pepper Pathogen-Induced Transcription Factor RAV1 in Bacterial Disease Resistance, and Drought and Salt Stress Tolerance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chul, L.S.; Woo, C.H.; Sun, H.I.; Seok, C.D.; Kook, H.B. Functional Roles of the Pepper Pathogen-Induced bZIP Transcription Factor, CAbZIP1, in Enhanced Resistance to Pathogen Infection and Environmental Stresses. Planta 2006, 224. [Google Scholar]

- Chul, L.S.; Seok, C.D.; Sun, H.I.; Kook, H.B. The Pepper Oxidoreductase CaOXR1 Interacts with the Transcription Factor CaRAV1 and Is Required for Salt and Osmotic Stress Tolerance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, Y.; Baek, W.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, S.C. A Pepper RING-Finger E3 Ligase, CaFIRF1, Negatively Regulates the High-Salt Stress Response by Modulating the Stability of CaFAF1. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 1319–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, S.C. Pepper Stress-Associated Protein 14 Is a Substrate of CaSnRK2.6 That Positively Modulates Abscisic Acid-Dependent Osmotic Stress Responses. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 113, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Sun, K.; Chang, X.; Ouyang, Z.; Meng, G.; Han, Y.; Shen, S.; Yao, Q.; Piao, F.; Wang, Y. Comparative Physiological and Transcriptomic Analyses of Two Contrasting Pepper Genotypes under Salt Stress Reveal Complex Salt Tolerance Mechanisms in Seedlings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaoxia, W.; Yan, R.; Hailong, J.; Yan, W.; Jiaxing, Y.; Xiaoying, X.; Fucai, Z.; Haidong, D. Genome-Wide Identification and Transcriptional Expression Analysis of Annexin Genes in Capsicum Annuum and Characterization of CaAnn9 in Salt Tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, M.; Ying, W.; LiYue, W.; Duo, L.; Yanjie, Y. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals the Mechanism of the Alleviation of Salt Stress by Salicylic Acid in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, S.; Chen, C.; Li, M.; Du, Q.; Wang, J.; Yin, Y.; Xiao, H. CaCP15 Gene Negatively Regulates Salt and Osmotic Stress Responses in Capsicum Annuum L. Genes 2023, 14, 1409. Genes 2023, 14, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Ma, J.; Luo, D.; Hou, X.; Ma, F.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, W. CaMADS, a MADS-Box Transcription Factor from Pepper, Plays an Important Role in the Response to Cold, Salt, and Osmotic Stress. Plant Sci. Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 2019, 280, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.W.; Lim, S.; Baek, W.; Lee, S.C. The Pepper Late Embryogenesis Abundant Protein CaLEA1 Acts in Regulating Abscisic Acid Signaling, Drought and Salt Stress Response. Physiol. Plant. 2015, 154, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Tu, J.; Xu, X.; Chen, X. Research Progress on Salt Stress Response and Salt Tolerance Mechanism of Vegetable Crops. China Veg. 2024, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JingJing, X.; RuiXing, Z.; Abid, K.; Saeed, U.H.; WenXian, G.; ZhenHui, G. CaFtsH06, A Novel Filamentous Thermosensitive Protease Gene, Is Involved in Heat, Salt, and Drought Stress Tolerance of Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.-H.; Ok, S.H.; Kim, D.; Suh, S.-C.; Byun, M.O.; Shin, J.S. Molecular Characterization of a Biotic and Abiotic Stress Resistance-Related Gene RelA/SpoT Homologue ( PepRSH ) from Pepper. Plant Sci. 2009, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Hui, F.; Huai-Xia, Z.; Muhammad, A.; Wen-Xian, G.; Guo-Xin, C.; Qing-Hui, Y.; Sheng-Bao, Y.; Xi-Xuan, L.; Zhen-Hui, G. A Small Heat Shock Protein CaHsp25.9 Positively Regulates Heat, Salt, and Drought Stress Tolerance in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Zhang, L.; Jiao, K.; Wang, Z.; Yong, K.; Lu, M. Vesicle Formation-Related Protein CaSec16 and Its Ankyrin Protein Partner CaANK2B Jointly Enhance Salt Tolerance in Pepper. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S. Screening of Pepper Salt Tolerance Germplasm Resources and Functional Research of Salt Tolerance Related Transcription Factor CaWRKY12. Master, Nanjing Agricultural University, 2022.

- Wei, X.; Yao, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, X. Cloning and Expression Analysis of CaWRKY13 Gene from Capsicumannuum L. under Abiotic Stress. Mol. Plant Breed. 2016, 14, 2582–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WenFeng, N.; Yue, C.; Junjie, T.; Yu, L.; Jianping, L.; Yong, Z.; Youxin, Y. Identification of the 12-Oxo-Phytoeienoic Acid Reductase (OPR) Gene Family in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.) and Functional Characterization of CaOPR6 in Pepper Fruit Development and Stress Response. Genome 2022, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Saeed, U.H.; Hou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, D.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Molecular and Functional Characterization of CaNAC035, an NAC Transcription Factor From Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, W.; Snyder, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Pan, B.; Guo, G.; Ge, W.; Dawood, M. Genome-Wide Analyses of the NAC Transcription Factor Gene Family in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.): Chromosome Location, Phylogeny, Structure, Expression Patterns, Cis-Elements in the Promoter, and Interaction Network. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.J.; Sam, S.Y.; Jin, K.S.; Taek, K.W.; Sheop, S.J. Constitutive Expression of CaXTH3, a Hot Pepper Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylase/Hydrolase, Enhanced Tolerance to Salt and Drought Stresses without Phenotypic Defects in Tomato Plants (Solanum Lycopersicum Cv. Dotaerang). Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Characterization of BiP Gene Family of Pepper(Capsicum annuum L.) and The Role of CaBiP1 in Response to Abiotic stress. Master, Northwest A&F University, 2018.

- Qiu, X.; Xu, M.; Shao, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Cheng, L.; Wu, C. Identification and Expression Analysis of OSCA Gene Family inPepper. Mol. Plant Breed.

- Gou, B. Expression analysis of CaTPS family genes and functional analysis ofCaTPS1 in response to low temperature and salt stresses in pepper. Master, Gansu Agricultural University, 2022.

- Wei, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Duan, J.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, X. Cloning and Expression Analysis of CaCBF1A Gene from Capsicum annuum L. under Abiotic Stress. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2016, 45, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. Genome-wide identification of the BTB domain-containing protein gene family andcharacterization of the related genes under Phytophthora capsici infection and abiotic stressesin pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Doctor, Northwest A&F University, 2021.

- Choi, H.W.; Hwang, B.K. The Pepper Extracellular Peroxidase CaPO2 Is Required for Salt, Drought and Oxidative Stress Tolerance as Well as Resistance to Fungal Pathogens. PLANTA 2012, 235, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, S.C. Pepper Novel Pseudo Response Regulator Protein CaPRR2 Modulates Drought and High Salt Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 736421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-F.; Liu, S.-Y.; Ma, J.-H.; Wang, X.-K.; Haq, S.U.; Meng, Y.-C.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Chen, R.-G. CaDHN4, a Salt and Cold Stress-Responsive Dehydrin Gene from Pepper Decreases Abscisic Acid Sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isayenkov, S.V. Genetic Sources for the Development of Salt Tolerance in Crops. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abass, A.D.K. Alleviation of Salinity Effects by Poultry Manure and Gibberellin Application on Growth and Peroxidase Activity in Pepper. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wei, Q.; Qin, Z.; Liang, L.; Li, Y. Effect of seed priming with γ-aminobutyric acid(GABA) on seed germination and seedling growth of pepper under salt stress. J. Gansu Agric. Univ. 2024, 59, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Wei, Q.; Qin, Z.; Lin, X.; Li, Y. Salicylic acid treatment Chaotianpepper seeds and seedlings to salt stress relief effect. J. Gansu Agric. Univ.

- Yang, S.; Zhou, L.; Chen, C.; Du, Q.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Liu, K.; Xiao, H.; Wang, J. Physiological and biochemical characteristics effects of exogenous ALA on pepper seedlings under saline-alkali stress. China Cucurbits Veg. 2023, 36, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, A.; Şirikçi, R.; Kocaçınar, F.; Değer, Ö.; Demirkırıan, A.R. Alleviation of Salt-Induced Adverse Effects in Pepper Seedlings by Seed Application of Glycinebetaine. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuce, M.; Aydin, M.; Turan, M.; Ilhan, E.; Ekinci, M.; Agar, G.; Yildirim, E. Ameliorative Effects of SL on Tolerance to Salt Stress on Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.) Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. PPB 2025, 223, 109798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghdoud, C.; Solano, C.J.; Franco, J.A.; Bañón, S.; Fernández, J.A.; Del Carmen Martínez-Ballesta, M. Supplemental Monochromatic Red Light Mitigates Salt-Induced Stress in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.) Plants. Plant Sci. Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 2025, 361, 112789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlTaey, D.K.A. Alleviation of Salinity Effects by Poultry Manure and Gibberellin Application on Growth and Peroxidase Activity in Pepper. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 2, 1851–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.-Y.; Lin, D.; Yang, Y. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals the Mechanism of the Alleviation of Salt Stress by Salicylic Acid in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 3593–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameliorative Effects of SL on Tolerance to Salt Stress on Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L. ) Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 223, 109798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yang, P.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, R.; Fu, H.; Li, J. Brassinosteroids Alleviate Salt Stress by Enhancing Sugar and Glycine Betaine in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Plants Basel Switz. 2024, 13, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, J.; Lima, G.S. de; Lima, V.L.A. de; Silva, A.A.R. da; Capitulino, J.D.; Caetano, E.J.M.; Silva, F. de A. da; Soares, L.A.D.A.; Fernandes, P.D.; Farias, M.S.S. de; et al. Effect of Hydrogen Peroxide Application on Salt Stress Mitigation in Bell Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Plants Basel Switz. 2023, 12, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, M.; Ekinci, M.; Ors, S.; Turan, M.; Agar, G.; Kul, R.; Yildirim, E. Nitric Oxide Mitigates Salt Stress Effects of Pepper Seedlings by Altering Nutrient Uptake, Enzyme Activity and Osmolyte Accumulation. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants Int. J. Funct. Plant Biol. 2019, 25, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.L.J.; de Farias, O.R.; Corrêa, É.B.; de Lacerda, C.F.; de Melo, A.S.; Oliveira, M.D. de M. Biostimulant Modulate the Physiological and Biochemical Activities, Improving Agronomic Characteristics of Bell Pepper Plants under Salt Stress. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, K.A.A.; Mazrou, Y.S.A.; Hafez, Y.M. Silicon Foliar Application Mitigates Salt Stress in Sweet Pepper Plants by Enhancing Water Status, Photosynthesis, Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Fruit Yield. Plants Basel Switz. 2020, 9, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, M.-S.; Son, J.-S.; Hwang, Y.-J.; Kwon, D.-K.; Ghim, S.-Y. Alleviation of Salt Stress in Pepper (Capsicum Annum L.) Plants by Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy Choudhury, A.; Choi, J.; Walitang, D.I.; Trivedi, P.; Lee, Y.; Sa, T. ACC Deaminase and Indole Acetic Acid Producing Endophytic Bacterial Co-Inoculation Improves Physiological Traits of Red Pepper (Capsicum Annum L.) under Salt Stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 267, 153544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakelli, A.; Dif, G.; Djemouai, N.; Bouri, M.; Şahin, F. Plant Growth-Promoting Pseudomonas Sp. TR47 Ameliorates Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L. Var. Conoides Mill) Growth and Tolerance to Salt Stress. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddikee, M.A.; Glick, B.R.; Chauhan, P.S.; Yim, W. jong; Sa, T. Enhancement of Growth and Salt Tolerance of Red Pepper Seedlings (Capsicum Annuum L.) by Regulating Stress Ethylene Synthesis with Halotolerant Bacteria Containing 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylic Acid Deaminase Activity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. PPB 2011, 49, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, T.; Xu, X.; Liu, X. De Novo Transcriptome Sequencing of Capsicum Frutescens. L and Comprehensive Analysis of Salt Stress Alleviating Mechanism by Bacillus Atrophaeus WU-9. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, R.; He, L.; Hu, Z.; Liang, Y.; Lin, F.; Zhou, Y. Endophytic Fungus Falciphora Oryzae Enhances Salt Tolerance by Modulating Ion Homeostasis and Antioxidant Defense Systems in Pepper. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e14059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, A.S.; Ben-Hamadou, R.; Hamdi, H.; Saadaoui, I.; Ahmed, T. Application of Cyanobacteria (Roholtiella Sp.) Liquid Extract for the Alleviation of Salt Stress in Bell Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.) Plants Grown in a Soilless System. Plants Basel Switz. 2021, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiztekin, M.; Tuna, A.L.; Kaya, C. Physiological Effects of the Brown Seaweed Ascophyllum Nodosum) and Humic Substances on Plant Growth, Enzyme Activities of Certain Pepper Plants Grown under Salt Stress. Acta Biol. Hung. 2018, 69, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penella, C.; Landi, M.; Guidi, L.; Nebauer, S.G.; Pellegrini, E.; San Bautista, A.; Remorini, D.; Nali, C.; López-Galarza, S.; Calatayud, A. Salt-Tolerant Rootstock Increases Yield of Pepper under Salinity through Maintenance of Photosynthetic Performance and Sinks Strength. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 193, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baath, G.S.; Shukla, M.K.; Bosland, P.W.; Steiner, R.L.; Walker, S.J. Irrigation Water Salinity Influences at Various Growth Stages of Capsicum Annuum. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penella, C.; Landi, M.; Guidi, L.; Nebauer, S.G.; Pellegrini, E.; Bautista, A.S.; Remorini, D.; Nali, C.; Lopez-Galarza, S.; Calatayud, A. Salt-Tolerant Rootstock Increases Yield of Pepper under Salinity through Maintenance of Photosynthetic Performance and Sinks Strength. J. PLANT Physiol. 2016, 193, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Serial No. | Salt tolerance varieties |

Salt sensitive varieties |

Performance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 'Xin San Ying Ba Hao'、'Nan Han Tian Hong Yi Hao F1'、'Ka Qi San Ying Jiao' | 'Chao Tian Jiao Chao Ji 808'、'Zhe JiaoXin Yi Dai'、'Kang Chong Cha Xian Feng Ba Hao' | Compared with salt-sensitive varieties, 'Xin San Ying Ba Hao'、'Nan Han Tian Hong Yi Hao F1'、'Ka Qi San Ying Jiao' showed high salt tolerance under 150 mM NaCl salt stress. Physiological indexes and transpiration rates of varieties with salt tolerance were significantly higher than salt-sensitive varieties at 10-15 days after salt stress. | [23] |

| 2 | 'P300' | '323F3' | The 'P300' and '323F3' varieties were treated with 150 mM NaCl, and their growth indexes, antioxidant enzyme activity, and osmoregulatory substances-related indexes were measured. The salt tolerance of 'P300' was better than that of '323F3'. | [27] |

| 3 | 'Y08-27', 'S-322' | 'Y802-2', 'Y08-29' | The seedlings were treated with 150 mM NaCl. By measuring the growth indexes and physiological and biochemical indexes of pepper seeds under salt stress, the tested pepper varieties (lines) were divided into three categories using variance analysis and systematic cluster analysis. Among them, 'Y08-27' and 'S-322' pepper varieties (lines) had strong salt tolerance. 'Y802-2' and 'Y08-29' are salt-sensitive strains. | [28] |

| 4 | '7301', 'D1' | 'GX7', '102' | Varieties '7301' and 'D1' showed high salt tolerance in seed germination tests, among which '7301' could still germinate when treated with 250mM NaCl solution, and the germination rate was 28.7%. | [29] |

| 5 | 'Zhongjiao-6', 'Zhongjiao-13', 'Zhongjiao-16', 'Zhongjiao-10' | 'Zhongjiao-4', 'Zhongjiao-8', 'Zhongjiao-7', 'Zhongjiao-12' | Under NaCl treatment of 150 mM, multivariate analysis of variance, factor analysis, and cluster analysis was performed on 12 indicators, and it was determined that 'Zhongjiao-6', 'Zhongjiao-13', 'Zhongjiao-16' and 'Zhongjiao-10' had excellent salt tolerance. | [30] |

| 6 | 'Niu Jiao Jiao', 'Guo Feng Gan Xian Wang', 'Pi Li Zao Guan', 'Xin You-1', 'Du Ba Tian Xia', 'Qian Jin Huang Jiao', 'Bi Hai Hong', '88 Da Jiao' | 'Ai Nong-6', 'Chao Ji Ju Feng 301', 'Chao Ji Kang Jiao-1', 'Juan Gu', 'Hong Sheng You', 'Gai Liang Te Da Zhong Liu', 'Da Yu Nong Da 40' | The salt treatment concentration of 200 mM NaCl was used to stress pepper seeds. Varieties salt tolerance and salt sensitivity were determined by measuring relative germination potential, relative germination rate, relative germination index, relative vitality index, relative salt damage rate, relative fresh weight, relative dry weight, and relative root length. | [31] |

| 7 | 'H1023' | 'XWHJ-M' | In the research, the expression of target genes of these two materials was investigated by salt stress (250mM). | [32,33] |

| 8 | 'A25' | 'A6' | 'A25' and 'A6' were subjected to a salt treatment of 70 mM NaCl for 14 days. The following physiological parameters were measured:Biomass, Osmotic potential, Ion homeostasis, Photosynthetic parameters, Antioxidant activity. The results showed that 'A25' utilized multiple strategies to cope with salt stress, including increased potassium and proline accumulation, improved growth mechanisms, and effective ionic homeostasis compared to 'A6'. | [8] |

| Serial No. | Gene Name | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CaSBP11 | Play a positive regulatory role in the process of salt stress | [76] |

| CaSBP12 | |||

| 2 | CaWRKY12 | Participating in pepper salt stress response can improve plant salt tolerance | [98] |

| CaWRKY13 | Salt stress can induce CaWRKY13 gene expression | [99] | |

| 3 | CaLACS1 | The expression of varieties with salt tolerance was higher than that of salt-sensitive varieties induced by salt stress | [33] |

| CaLACS2 | |||

| 4 | CaOPR6 | The expression was induced by salt stress, low temperature and pathogen infection | [100] |

| 5 | CaCP1 | Negative regulatory factors mediate plant defense responses to salt stress | [81] |

| CaCP15 | Negative regulation of pepper tolerance to salt stress | [90] | |

| 6 | CaAnn9 | Plays a negative role in salt stress | [88] |

| 7 | CaNAC014 | Positively regulate the tolerance of pepper to salt stress | [32] |

| CaNAC026 | |||

| CaNAC078 | |||

| CaNAC020 | Negative regulation of pepper tolerance to salt stress | ||

| CaNAC075 | |||

| CaNAC035 | Play a positive regulatory role in the process of low temperature、salt and drought stress | [101] | |

| CaNAC36 | Under salt stress , the expression of CaNAC36 gene was up-regulated and then down-regulated in materials with salt tolerance, and down-regulated in materials with salt sensitivity | [102] | |

| CaNAC61 | Expression was significantly upregulated under NaCl treatment | [77] | |

| 8 | CaBBX4 | The transcription of CaBBX4, CaBBX5, CaBBX7 and CaBBX10 was up-regulated under salt stress | [78] |

| CaBBX5 | |||

| CaBBX7 | |||

| CaBBX10 | |||

| CaBBX1 | Under salt stress, the expression levels of CaBBX1, CaBBX2, CaBBX6 and CaBBX9 were only up-regulated at some time points | ||

| CaBBX2 | |||

| CaBBX6 | |||

| CaBBX9 | |||

| CaBBX3 | The transcription of CaBBX4, CaBBX5, CaBBX7 and CaBBX10 was down-regulated under salt stress | ||

| CaBBX8 | |||

| 9 | CaPIF4 | Negative regulation of pepper tolerance to salt stress. | [80] |

| CaPIF8 | Positively regulate the tolerance of pepper to salt stress | [57] | |

| 10 | CaFtsH06 | Salt stress can rapidly induce the expression of CaFtsH06 | [94] |

| 11 | PepRSH | Salt stress can affect the expression of PepRSH | [95] |

| 12 | CaXTH3 | Negative regulation of pepper tolerance to salt stress | [103] |

| 13 | CabZIP1 | Positively regulate the tolerance of pepper to salt stress | [83] |

| 14 | CaBiP1 | Positively regulate the tolerance of pepper to salt stress | [104] |

| 15 | CaOSCA8 | Salt stress induced up-regulation of CaOSCA8 expression | [105] |

| CaOSCA3 | Salt stress induced decreased expression levels of CaOSCA3, CaOSCA7, CaOSCA10 and CaOSCA12 | ||

| CaOSCA7 | |||

| CaOSCA10 | |||

| CaOSCA12 | |||

| 16 | CaTPS1 | The expression was induced in late NaCl stress | [106] |

| CaTPS2 | |||

| CaTPS3 | |||

| CaTPS4 | |||

| CaTPS5 | |||

| CaTPS6 | |||

| CaTPS7 | |||

| CaTPS8 | |||

| CaTPS10 | |||

| CaTPS11 | The expression was induced in the early stage and suppressed in the later stage of NaCl stress treatment | ||

| 17 | CaCBF1A | Salt stress can induce the expression of CaCBF1A, which reaches the peak value quickly and then decreases | [107] |

| 18 | CaBTB27 | Negative regulation of pepper tolerance to salt stress | [108] |

| 19 | CaFIRF1 | Ubiquitination of CaFAF1 by the RING-type E3 ligase CaFIRF1 led to its proteasomal degradation. Silencing of CaFIRF1 enhanced pepper tolerance to high-salt stress, revealing a role for the CaFIRF1-CaFAF1 module in salt stress response. | [85] |

| 20 | CaSnRK2.6 | CaSAP14, a direct substrate of the upstream kinase CaSnRK2.6, functions as a positive regulator of osmotic stress responses to dehydration and high salinity. | [86] |

| 21 | CaMADS | CaMADS functions as a positive regulator that modulates plant responses to multiple abiotic stresses, including cold, salinity, and osmotic stress. | [91] |

| 22 | CaLEA1 | CaLEA1 mediates enhanced salt tolerance by modulating ABA-responsive cellular signaling. | [92] |

| 23 | CaPO2 | Silencing CaPO₂ in pepper plants resulted in sensitivity to salt stress. | [109] |

| 24 | CaPRR2 | CaPRR2 negatively regulates salt stress tolerance. | [110] |

| 25 | CaERF2 | CaERF2 effectively enhances the salt tolerance in pepper by adjusting ROS homeostasis. | [55] |

| 26 | CaDHN3 | Positively regulate the tolerance of pepper to salt stress | [48] |

| CaDHN4 | Positively regulate the tolerance of pepper to salt stress | [111] |

| Serial No. | Material/Bacterial Synthetic Community | Application Method | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gibberellin(GA) | Foliar application | That possible to mitigation the negative affect of salt stress by some application like exogenous hormones and Decomposed organic matter to solve the disruption of endohormons and lack of available nutrients under salt stress, and elevation of osmotic stress in soil solution in roots area. | [120] |

| 2 | Salicylic acid(SA) | Foliar application | Salicylic acid alleviates salt stress by modulating key physiological processes, including ion uptake, gene expression, and transcriptional regulation. | [121] |

| 3 | 5-aminolevulinicacid,ALA | Foliar application | Application of ALA (40 mg·L⁻¹) improved salt stress tolerance in pepper by enhancing osmotic regulation. | [116] |

| 4 | Strigolactones (SLs) | Foliar application | Foliar application of 20 μM SL ameliorates the adverse effects of salt stress on pepper plants, mitigating growth inhibition and physiological damage. | [122] |

| Brassinosteroids (BRs) 2,4-epibrassinolide (EBR) |

Foliar application | EBR enhanced the antioxidant defense mechanisms in pepper seedlings by increasing sugar and glycine betaine levels, which contributed to the reduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and malondialdehyde (MDA) accumulation. | [123] | |

| γ-aminobutyric acid(GABA) | Germplasm Soaking | GABA promotes seed germination and enhances salt tolerance in peppers by facilitating the accumulation of seed storage reserves and boosting the antioxidant defense system. | [114] | |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Foliar application | Foliar application of hydrogen peroxide at a concentration of 15 μM mitigated the detrimental effects of salt stress on the photochemical efficiency, biomass accumulation, and production components of sweet pepper plants. | [124] | |

| sodium nitroprusside (SNP), a NO donor, | Foliar application | Exogenous NO treatment enhances pepper resistance to salt stress by regulating mineral nutrient uptake, antioxidant enzyme activity, osmotic sol accumulation, and enhancing LRWC and photosynthetic activity. | [125] | |

| Biostimulant VIUSID Agro | Foliar application | Treatment with Biostimulant VIUSID Agro enhances the photosynthetic capacity of pepper, improves fruit size and quality, strengthens osmotic regulation, and increases antioxidant enzyme activity, thereby effectively mitigating the effects of salt stress. | [126] | |

| Silicon | Foliar application | Foliar application of silicon alleviated lipid peroxidation, electrolyte leakage, and elevated levels of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide induced by salt stress. | [127] | |

| Three PGPR strains (Microbacterium oleivorans KNUC7074, Brevibacterium iodinum KNUC7183, and Rhizobium massiliae KNUC7586) | the inoculation of pepper plants with M. oleivorans KNUC7074, B. iodinum KNUC7183, and R. massiliae KNUC7586 can alleviate the harmful effects of salt stress on plant growth. | [128] | ||

| Pseudomonas koreensis S2CB45 Microbacterium hydrothermale IC37-36 |

Co-inoculation with both bacteria resulted in significantly higher antioxidant enzyme activity and soluble sugar levels than single-bacterium treatments, demonstrating a synergistic improvement in salinity tolerance. | [129] | ||

| the Tamarix gallica L. rhizospheric bacterium TR47 | Inoculation with the Tamarix gallica L. rhizospheric bacterium TR47 promoted the growth of pepper plants under salt stress, leading to greater biomass accumulation and enhanced salt tolerance compared to the control group. | [130] | ||

| Three 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) deaminase-producing halotolerant bacteria:Brevibacterium iodinum, Bacillus licheniformis and Zhihengliuela alba | By utilizing three 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) deaminase-producing halotolerant bacteria that produce ACC deaminase, thereby reducing the impact of ethylene induced by salt stress on the growth of red pepper plants. | [131] | ||

| Bacillus atrophaeus WU-9 as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) | Inoculation with Bacillus atrophaeus WU-9 under salt stress primarily enhances pepper plant salt tolerance by regulating ethylene and auxin signaling pathways involved in salt stress response, proline utilization, photosynthesis, and antioxidant enzyme activity. | [132] | ||

| Endophytic fungus Falciphora oryzae | Inoculation with F. oryzae can enhance the salt tolerance of pepper by promoting ion homeostasis and upregulating antioxidant defense systems. | [133] | ||

| Cyanobacteria (Roholtiella sp.) Cyanobacteria Extracts |

Foliar application | Foliar application of Cyanobacteria (Roholtiella sp.) extracts can minimize the adverse effects of salt stress on the vegetative growth, biochemical characteristics, and enzyme activity of sweet peppers. | [134] | |

| Seaweed extract,SW Humic acid,HA |

Under salt stress, treatment with seaweed extract and humic acid enhanced the antioxidant enzyme activity of pepper plants, thereby improving their tolerance to salt stress and protecting them from oxidative stress. | [135] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).