Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

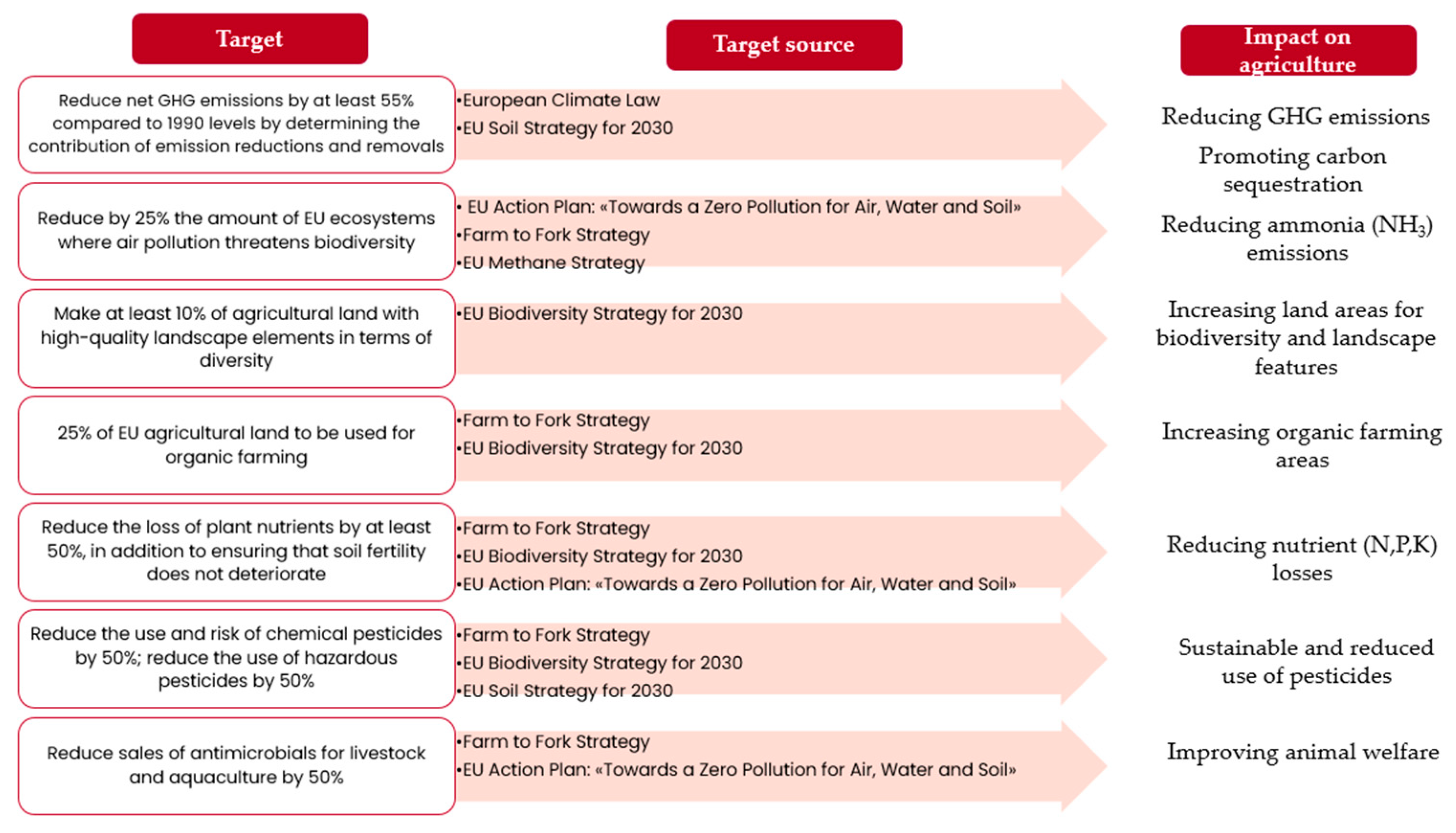

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework and Data Sources

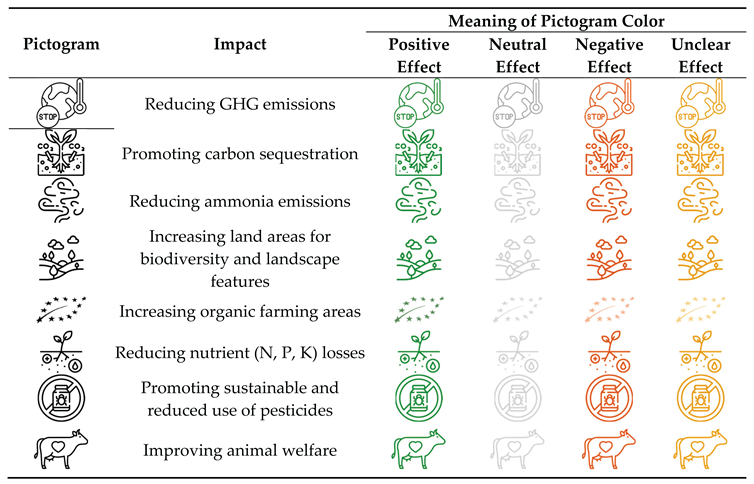

2.2. Analysis of Practice and Impact Evaluation

2.3. Data Visualization and Synthesis

3. Results

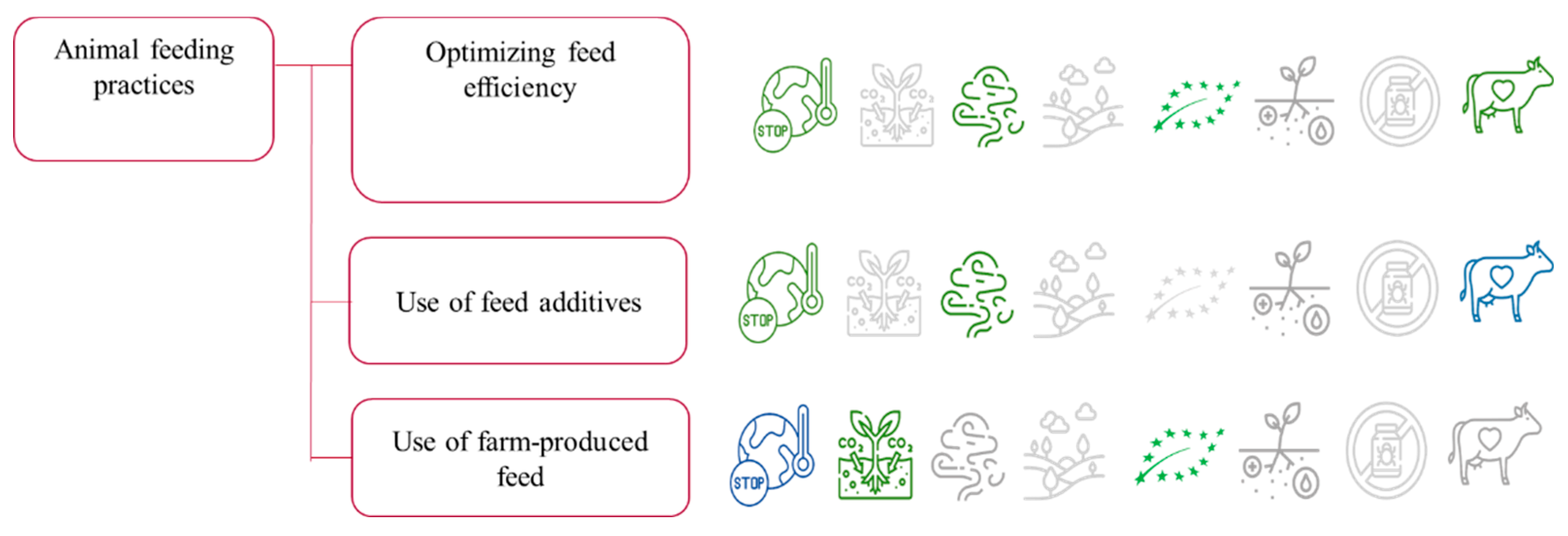

3.1. Animal Feeding Practices

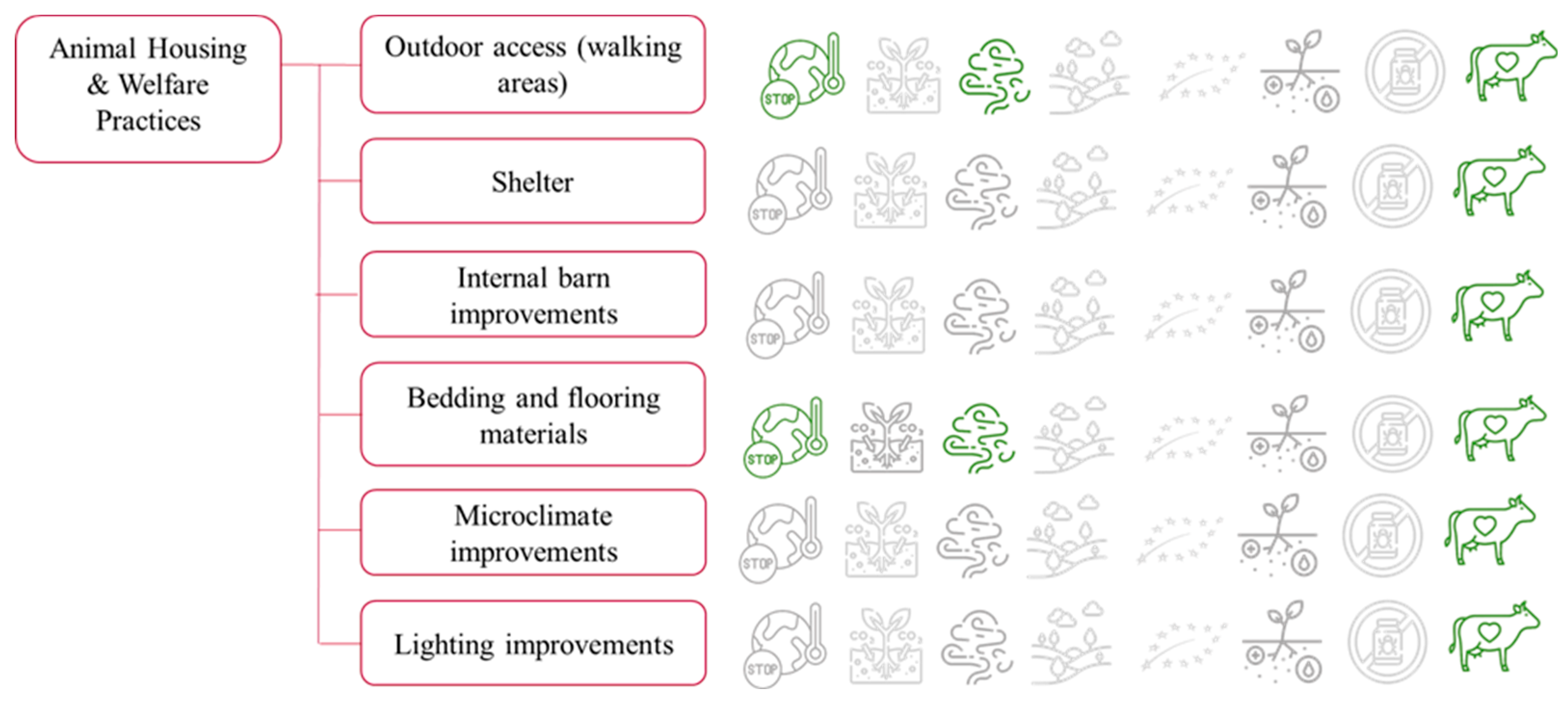

3.2. Animal Housing & Welfare Practices

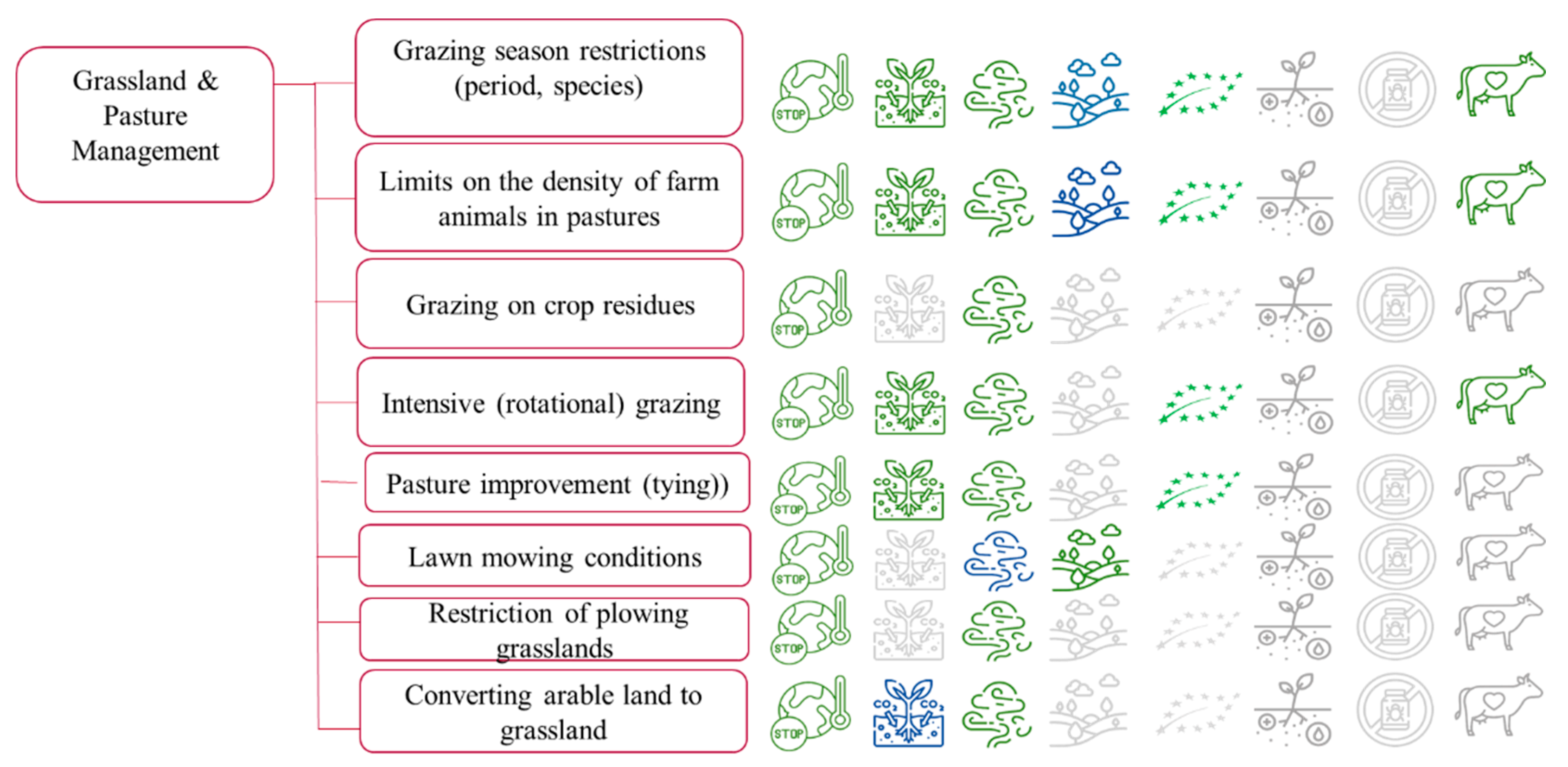

3.3. Grassland & Pasture Management

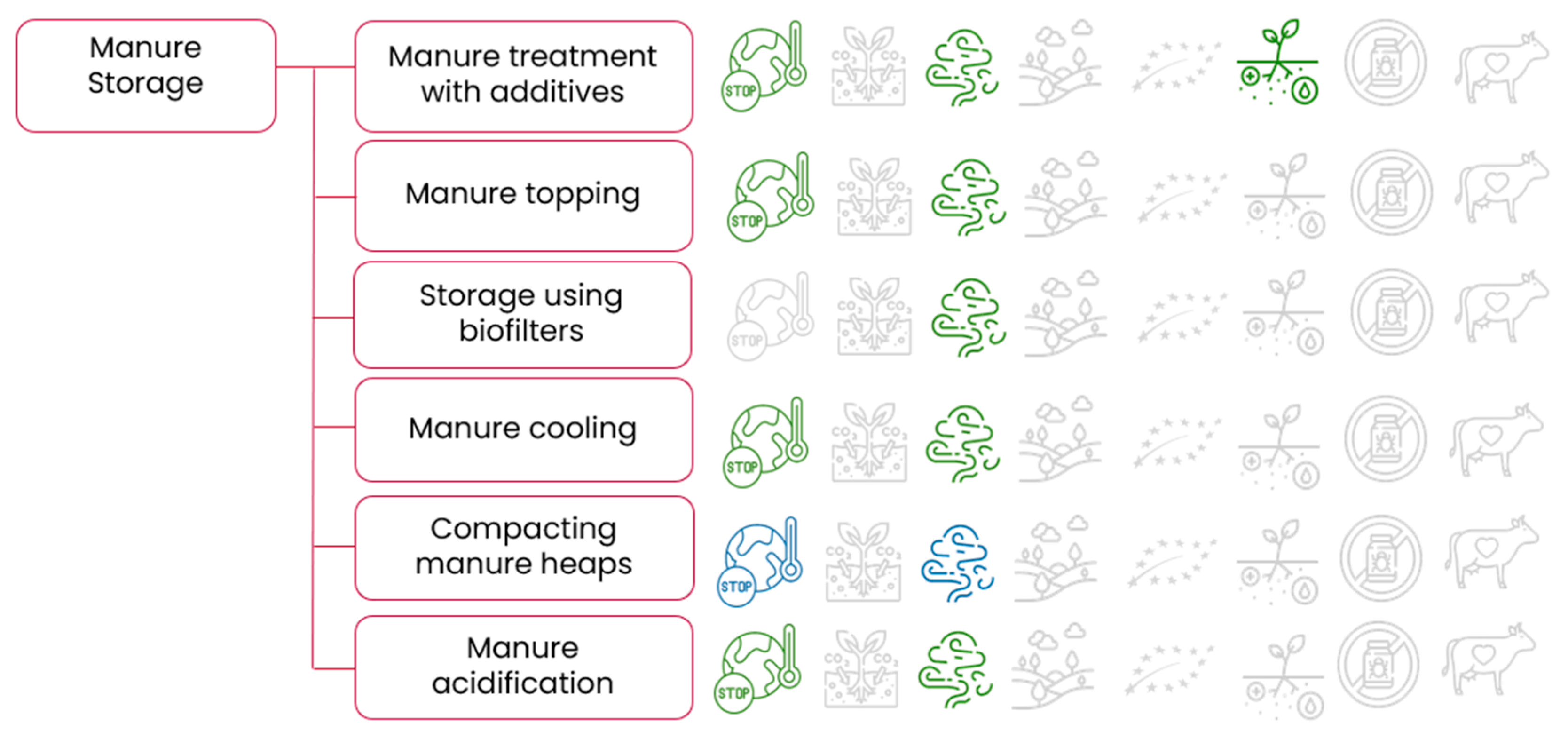

3.4. Manure Storage

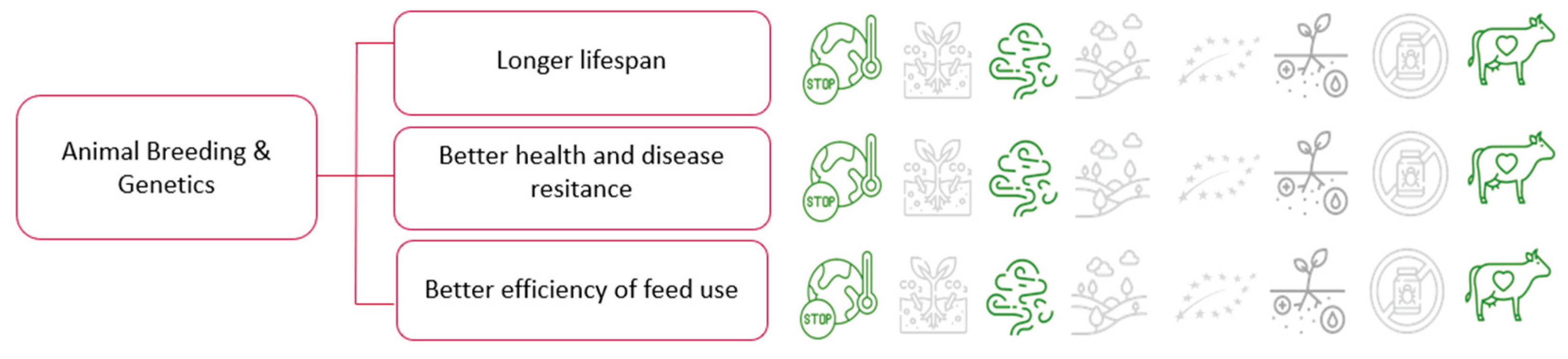

3.5. Animal Breeding & Genetics

4. Discussion on Cross-Cutting Research Gaps & Systemic Challenges

| Practice Group | GHG | Biodiversity | Nutrients | Welfare |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Feeding | High | Low | Medium | Medium, Low (methane inhibitors) |

| Animal Housing & Welfare | Medium | Low | Medium | High |

| Grassland & Pasture Management | Medium | Medium | High | High |

| Manure Storage | High | Very Low | Medium | Low |

| Breeding and Genetics | High | Very Low | Low | High |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mielcarek-Bocheńska, P., & Rzeźnik, W. Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture in EU countries—state and perspectives. Atmosphere 2021, 12(11), 1396. [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E. G., Dlugokencky, E. J., Fisher, R. E., France, J. L., Lowry, D., Manning, M. R., Michel, S. E., & Warwick, N. J. Atmospheric methane and nitrous oxide: challenges alongthe path to Net Zero. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 2021, 379(2210), 20200457. [CrossRef]

- Kremen, C. Ecological intensification and diversification approaches to maintain biodiversity, ecosystem services and food production in a changing world. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences 2020, 4(2), 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopittke, P.M., Menzies, N.W., Wang, P., McKenna, B.A., Lombi, E. Soil and the intensification of agriculture for global food security. Environment International 2019, Volume 132. [CrossRef]

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025 – Addressing high food price inflation for food security and nutrition. Rome. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Manning, L. Innovating in an uncertain world: understanding the social, technical and systemic barriers to farmers adopting new technologies. Challenges 2024, 15(2), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, L. M. Grand challenges and transformative solutions for rangeland social-ecological systems–emphasizing the human dimensions. Rangelands 2021, 43(4), 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeon, G. K. , Akamati, K., Dotas, V., Karatosidi, D., Bizelis, I., & Laliotis, G. P. Manure Management as a Potential Mitigation Tool to Eliminate Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Livestock Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17(2), 586. [Google Scholar]

- Kleijn, D., Bommarco, R., Fijen, T. P., Garibaldi, L. A., Potts, S. G., & Van Der Putten, W. H. Ecological intensification: bridging the gap between science and practice. Trends in ecology & evolution 2019, 34(2) 154-166. [CrossRef]

- Bond, A. , Pope, J., Fundingsland, M., Morrison-Saunders, A., Retief, F., & Hauptfleisch, M. Explaining the political nature of environmental impact assessment (EIA): A neo-Gramscian perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 244, 118694. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V. , Yang, X., Fleskens, L., Ritsema, C. J., & Geissen, V. Environmental and human health at risk–Scenarios to achieve the Farm to Fork 50% pesticide reduction goals. Environment international 2022, 165, 107296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lampkin, N., Stolze, M., Meredith, S., De Porras, M., Haller, L., & Mészáros, D. (2020). Using Eco-schemes in the new CAP: a guide for managing authorities. IFOAM EU 2020, pages 73.

- Möhring, N., Ingold, K., Kudsk, P., Martin-Laurent, F., Niggli, U., Siegrist, M., Studer, B., Walter, A., & Finger, R. Pathways for advancing pesticide policies. Nature food 2020, 1(9), 535-540. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P. K., & Dubey, A. Integrated farming system. Test Book of resource conservation practices. 2023, 99-113.

- Smith, P. , Arneth, A., Barnes, D. K., Ichii, K., Marquet, P. A., Popp, A., Pörtner, H. O., Rogers, A. D., Scholes, R. J., & Strassburg, B. How do we best synergize climate mitigation actions to co-benefit biodiversity? Global Change Biology 2022, 28(8), 2555–2577. [Google Scholar]

- Swart, R., Levers, C., Davis, J. T., & Verburg, P. H. Meta-analyses reveal the importance of socio-psychological factors for farmers’ adoption of sustainable agricultural practices. One Earth 2023, 6(12), 1771-1783. [CrossRef]

- Clay, N., Garnett, T., & Lorimer, J. Dairy intensification: Drivers, impacts and alternatives. Ambio 2020, 49(1), 35-48. [CrossRef]

- van Vuuren, D. P. , Zimm, C., Busch, S., Kriegler, E., Leininger, J., Messner, D., Nakicenovic, N., Rockstrom, J., Riahi, K., & Sperling, F. Defining a sustainable development target space for 2030 and 2050. One Earth 2022, 5(2), 142–156. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, A., Rickards, L., Houston, D., Goodman, M. K., & Bojovic, M. The biopolitics of cattle methane emissions reduction: Governing life in a time of climate change. Antipode 2021, 53(4), 1161-1185. [CrossRef]

- Manta, A.G.; Doran, N.M.; Bădîrcea, R.M.; Badareu, G.; Gherțescu, C.; Lăpădat, C.V.M. Does Common Agricultural Policy Influence Regional Disparities and Environmental Sustainability in European Union Countries? Agriculture 2024, 14, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M. T., Cullen, B. R., Mayberry, D. E., Cowie, A. L., Bilotto, F., Badgery, W. B., Liu, K., Davison, T., Christie, K. M., & Muleke, A. Carbon myopia: The urgent need for integrated social, economic and environmental action in the livestock sector Global Change Biology 2021, 27(22), 5726-5761.

- Gehrke, T. EU open strategic autonomy and the trappings of geoeconomics. European Foreign Affairs Review 2022, 27(Special). [CrossRef]

- Fournier Gabela, J. G. , Spiegel, A., Stepanyan, D., Freund, F., Banse, M., Gocht, A., Matthews, A. Carbon leakage in agriculture: when can a carbon border adjustment mechanism help? Climate Policy 2024, 24(10), 1410–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A classification scheme based on farming practices, Publications Office of the European Union, 2024, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/33560.

- Stefanis, C., Stavropoulos, A., Stavropoulou, E., Tsigalou, C., Constantinidis, T. C., & Bezirtzoglou, E. A spotlight on environmental sustainability in view of the European Green Deal. Sustainability 2024, 16(11), 4654. [CrossRef]

- Wyngaarden, S. L., Lightburn, K. K., & Martin, R. C. Optimizing livestock feed provision to improve the efficiency of the agri-food system. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 2020, 44(2), 188-214. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Nan, X., Yang, L., Zheng, S., Jiang, L., & Xiong, B. A review of enteric methane emission measurement techniques in ruminants. Animals 2020, 10(6), 1004.

- Guo, Y., Tong, B., Wu, Z., Ma, W., & Ma, L. Dietary manipulation to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus excretion by dairy cows. Livestock Science 2019, 228, 61–66.

- Ipharraguerre, I.R., Clark, J.H. Impacts of the Source and Amount of Crude Protein on the Intestinal Supply of Nitrogen Fractions and Performance of Dairy Cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2005, Volume 88, Supplement, 2005, Pages E22-E37, ISSN 0022-0302. [CrossRef]

- de Rauglaudre, T., Méda, B., Fontaine, S., Lambert, W., Fournel, S., Létourneau-Montminy, M.P. Meta-analysis of the effect of low-protein diets on the growth performance, nitrogen excretion, and fat deposition in broilers. FRONTIERS IN ANIMAL SCIENCE 2023, 4, 1214076. [CrossRef]

- NorFor model 2025 Available: https://www.norfor.info/the-model/the-norfor-model/ Accessed: 15.09.2025.

- Kreismane Dz., Aplocina E., Naglis-Liepa K., Berzina L., Frolova O., Lenerts A. Diet optimization for dairy cows to reduce ammonia emissions. Research for Rural Development 2021, Vol. 36. Pages 36-43. [CrossRef]

- Nayak B., Liu R.H., Tang J. Effect of processing on phenolic antioxidants of fruits, vegetables, and grains--a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55(7):887-919. [CrossRef]

- Moran K., Chamusco, S., Aumiller, T. PSVI-4 Effect of Phytogenic Feed Additives on Ammonia Emission in Finishing Swine. Journal of Animal Science, 2022, Volume 100, Issue Supplement_2, Page 165. [CrossRef]

- Colin, R.L., Sperber, J. L., Buse, K.B., Kononoff, P.J., Watson, A.K., Erickson, G.E. Effect of an algae feed additive on reducing enteric methane emissions from cattle.” Translational Animal Science, 2024, Volume 8, txae109. [CrossRef]

- Martin, C., Morgavi, D.P., Doreau, M. Methane mitigation in ruminants: from microbe to the farm scale. Animal 2010, Volume 4, Issue 3. Pages 351-365. [CrossRef]

- Ti, C., Xia, L., Chang, S.X., Yan, X. Potential for mitigating global agricultural ammonia emission: A meta-analysis. Environmental Pollution 2019, 245:141-148. Epub 2018 Nov 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemensen Andrea , Halvorson Jonathan J. , Christensen Rachael , Kronberg Scott L. Potential benefits of tanniferous forages in integrative crop-livestock agroecosystems. Frontiers in Agronomy 2022, Volume 4 - 2022. [CrossRef]

- Black, J. L., Davison, T. M., & Box, I. Methane emissions from ruminants in Australia: Mitigation potential and applicability of mitigation strategies. Animals 2021, 11(4), 951. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G., Beauchemin, K. A., & Dong, R. A review of 3-nitrooxypropanol for enteric methane mitigation from ruminant livestock. Animals 2021, 11(12), 3540. [CrossRef]

- Kebreab, E., Bannink, A., Pressman, E.M., Walker, N., Karagiannis, A., van Gastelen, S., Dijkstra, J. A meta-analysis of effects of 3-nitrooxypropanol on methane production, yield, and intensity in dairy cattle. Journal of Dairy Science 2023, 106(2), 927-936. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M., Tricarico, J.M. Kebreab, E. Impact of nitrate and 3-nitrooxypropanol on the carbon footprints of milk from cattle produced in confined-feeding systems across regions in the United States: A life cycle analysis, Journal of Dairy Science 2022,Volume 105, Issue 6, 2022, Pages 5074-5083, ISSN 0022-0302. [CrossRef]

- DSM. Taking action on climate change, together, Summary of scientific research how 3-NOP effectively reduces enteric methane emissions from cows. 7th Greenhouse Gas and Animal Agriculture Conference, August 2019, Brazil. https://www.dsm.com/content/dam/dsm/corporate/en_US/documents/summary-scientific-papers-3nop-booklet.pdf".

- Kok, M., Schoolenberg, M., Löwenhardt, H., Voora, V., van Oorschot, M., Arlikatti, N., & Arts, B. (2023). Assessing the impact of international cooperative initiatives on biodiversity. PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency 2023, pages 123.

- Chadwick, D. R. , Williams, J. R., Lu, Y., Ma, L., Bai, Z., Hou, Y., Chen, X., & Misselbrook, T. H. Strategies to reduce nutrient pollution from manure management in China. Frontiers of Agricultural Science and Engineering 2020, 7(1), 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Vertès, F., Delaby, L., Klumpp, K., & Bloor, J. C–N–P uncoupling in grazed grasslands and environmental implications of management intensification. Agroecosystem diversity Elsevier 2019, pp. 15-34.

- Rolando, G. Ferrero, F., Pasinato, S., Comino, L., Giaccone, D., Tabacco, E., Borreani, G. Comparison of frameworks for defining land occupation considering on-farm and off-farm feed production on Italian dairy farms, Journal of Dairy Science 2025, Volume 108, Issue 3, Pages 2595-2609, ISSN 0022-0302. [CrossRef]

- Faux, A.-M., Decruyenaere, V., Guillaume, M., & Stilmant, D. Feed autonomy in organic cattle farming systems: a necessary but not sufficient lever to be activated for economic efficiency. Organic Agriculture 2022, 12(3), 335-352. [CrossRef]

- Cellier, P., Génermont, S., Pierart, A., Agasse, S., Drouet, J.-L., Edouard, N., Eglin, T., Galsomiès, L., Guingand, N., & Loubet, B. Reducing the Impacts of Agriculture on Air Quality. Agriculture and Air Quality: Investigating, Assessing and Managing Springer, 2021, pp. 245-282. [CrossRef]

- Hylander, B. L., Repasky, E. A., & Sexton, S. Using mice to model human disease: understanding the roles of baseline housing-induced and experimentally imposed stresses in animal welfare and experimental reproducibility. Animals 2022, 12(3), 371. [CrossRef]

- Lisette M.C. Leliveld, Brandolese, C., Grotto, M., Marinucci, A., Fossati, N., Lovarelli, D., Riva, E., Provolo. G. Real-time automatic integrated monitoring of barn environment and dairy cattle behaviour: Technical implementation and evaluation on three commercial farms. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, Volume 216. [CrossRef]

- Llonch, P., Haskell, M.J., Dewhurst, R.J., Turner, S.P. Current available strategies to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions in livestock systems: an animal welfare perspective. Animal 2017, Volume 11, Issue 2, Pages 274-284. [CrossRef]

- Du, H.-L., Chatti, M., Hodgetts, R. Y., Cherepanov, P. V., Nguyen, C. K., Matuszek, K., MacFarlane, D. R., & Simonov, A. N. Electroreduction of nitrogen with almost 100% current-to-ammonia efficiency. Nature 2022, 609(7928), 722-727. [CrossRef]

- Sykes, A. J., Macleod, M., Eory, V., Rees, R. M., Payen, F., Myrgiotis, V., Williams, M., Sohi, S., Hillier, J., & Moran, D. Characterising the biophysical, economic and social impacts of soil carbon sequestration as a greenhouse gas removal technology. Global Change Biology 2020, 26(3), 1085-1108. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., & Wang, X. Manure treatment and utilization in production systems. Animal agriculture Elsevier, 2020, pp. 455-467. [CrossRef]

- Kebede, E. Contribution, utilization, and improvement of legumes-driven biological nitrogen fixation in agricultural systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 5, 767998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutter, M., Kronvang, B., Ó hUallacháin, D., & Rozemeijer, J. Current insights into the effectiveness of riparian management, attainment of multiple benefits, and potential technical enhancements. Journal of Environmental Quality 2019, 48(2), 236-247. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen , J., Ledgard, S., Luo, J., Schils, R., Rasmussen. J. Environmental impacts of grazed pastures. 2010. Available: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/17879/4/17879.pdf Accessed: 20.09.2025.

- de Boer. I.J.M. Environmental impact assessment of conventional and organic milk production. Livestock Production Science 2003 Volume 80, Issues 1–2, Pages 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Horacio A. Aguirre-Villegas, R., Larson, A., Rakobitsch, N., Wattiaux, M.A., Silva, E. Farm level environmental assessment of organic dairy systems in the U.S. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, Volume 363, 132390. [CrossRef]

- Lai, LM; Kumar, S. A global meta analysis of livestock grazing impacts on soil properties. PLOS ONE 2020, 15(8), e0236638. [CrossRef]

- Reinsch, T., Loges, R., Kluß, C., Taube, F. Effect of grassland ploughing and reseeding on CO2 emissions and soil carbon stocks. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2018. Volume 265, Pages 374-383. [CrossRef]

- Vellinga, T. , van den Pol-van Dasselaar, A., Kuikman, P. The impact of grassland ploughing on CO2 and N2O emissions in the Netherlands. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2004, 70, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, R., & Kreuter, U. Managing grazing to restore soil health, ecosystem function, and ecosystem services. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2020, 4, 534187. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Teague, W., Park, S., Bevers, S. GHG Mitigation Potential of Different Grazing Strategies in the United States Southern Great Plains 2015. [CrossRef]

- DAERA. (2023). Ammonia emissions and agriculture. Available:https://www.daera-ni.gov.uk/news/ammonia-emissions-and-agriculture Accessed: 22.09.2025.

- Umar, W., Vandenbussche, C., Dinuccio, E., Dong, H., & Amon, B. Acidification of animal slurry in housing and during storage to reduce NH3 and GHG emissions-recent advancements and future perspectives. Waste management, 2025, 203, 114856. [CrossRef]

- Dalby, F. R., Guldberg, L. B., Feilberg, A., & Kofoed, M. V. W. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions from pig slurry by acidification with organic and inorganic acids. PloS one, 17(5), 2022, e0267693. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Herrera, D., Prost, K., Kim, D.-G., Tadese, M., Gebrehiwot, M., Brüggemann, N. Biochar addition reduces non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions during composting of human excreta and cattle manure. Journal of Environmental Quality, Vol. 52 (4), 2023, pp. 814-828. [CrossRef]

- Prado, J., Chieppe, J., Raymundo, A., Fangueiro, D. Bio-acidification and enhanced crusting as an alternative to sulphuric acid addition to slurry to mitigate ammonia and greenhouse gases emissions during short term storage. Journal of Cleaner Production, 263, 2020. 121443. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.A., Fangueiro, D., Carvalho, M. Slurry Acidification as a Solution to Minimize Ammonia Emissions from the Combined Application of Animal Manure and Synthetic Fertilizer in No-Tillage. Agronomy 2022, 12, 265. [CrossRef]

- Gioelli, F., Grella, M., Scarpeci, T.E., Rollè, L., Pierre, F.D., Dinuccio, E. Bio-Acidification of Cattle Slurry with Whey Reduces Gaseous Emission during Storage with Positive Effects on Biogas Production. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12331. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, D. R. Emissions of ammonia, nitrous oxide and methane from cattle manure heaps: effect of compaction and covering. Atmospheric Environment, 2005, 39(4), 787–799. [CrossRef]

- Barwick, S.A., Henzell, A.L., Walmsley, B.J., Johnston, D.J., Banks, R.G. Methods and consequences of including feed intake and efficiency in genetic selection for multiple-trait merit. Journal of Animal Science, 2018 May 4;96(5):1600-1616. [CrossRef]

- Stepanchenko, N., Stefenoni, H., Hennessy, M., Nagaraju, I., Wasson, D.E., Cueva, S.F., Räisänen, S.E., Dechow, C.D., Pitta, D.W., Hristov, A.N. Microbial composition, rumen fermentation parameters, enteric methane emissions, and lactational performance of phenotypically high and low methane-emitting dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science, Volume 106, Issue 9, 2023, Pages 6146-6170, ISSN 0022-0302. [CrossRef]

- Mostert, P., Bokkers, E.A.M., Boer, I., Middelaar, C. (2019). Estimating the impact of clinical mastitis in dairy cows on greenhouse gas emissions using a dynamic stochastic simulation model: A case study. Animal, 2019, Vol. 13 (12), pp. 2913-2921. [CrossRef]

- Grandl, F., Furger, M., Kreuzer, M., Zehetmeier, M. Impact of longevity on greenhouse gas emissions and profitability of individual dairy cows analysed with different system boundaries. Animal, 2019, Vol. 13 (1), pp. 198–208). [CrossRef]

- Rogelj, J., & Schleussner, C.-F. Unintentional unfairness when applying new greenhouse gas emissions metrics at country level. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14(11), 114039.

- Loos, J., J. Gallersdörfer, T. Hartel, M. Dolek, and L. Sutcliffe. Limited effectiveness of EU policies to conserve an endangered species in high nature value farmland in Romania. Ecology and Society 2021, 26(3):3. [CrossRef]

- Naglis-Liepa K., Popluga D., Lenerts A., Rivza P., Kreismane Dz. Integrated impact assessment of agricultural GHG abatement measures. Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference "Economic Science for Rural Development" No 49. Jelgava, LLU ESAF, 9 11 May 2018, pp. 77-83. [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, L., Veysset, P., Benoit, M., & Dumont, B. Ecological network analysis to link interactions between system components and performances in multispecies livestock farms: Ecological network analysis to link interactions between system components and performances in multispecies livestock farms. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2021, 41(3), 42.

- Raja, T., Khan, A., & Najar, I. Internet of things (IOT) for animal husbandry-an outlook in livestock and poultry. The Pharma innovation journal 2020, SP-9(4): 42-46.

- Loss, A., Couto, R. d. R., Brunetto, G., Veiga, M. d., Toselli, M., & Baldi, E. Animal manure as fertilizer: changes in soil attributes, productivity and food composition. Int. J. Res. Granthaalayah 2019, 7(9), 307. [CrossRef]

- Lampkin N, Stolze M, Meredith S, de Porras M, Haller L, Mészáros D (2020) Using Eco-schemes in the new CAP: a guide for managing authorities. IFOAM EU, FIBL and IEEP, Brussels. Available at: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/37227/1/lampkin-etal-2020-IFOAM-Eco-schemes-guide-final.pdf.

- Sustelo, M. L. M. G. Examining the Feasibility of Attaining Carbon Neutrality by 2050 and Ensuring a Just Transition: The European Green Deal in the Context of EU Law. Universidade NOVA de Lisboa Portugal 2023.

- Purnhagen, K. P. , Clemens, S., Eriksson, D., Fresco, L. O., Tosun, J., Qaim, M., Visser, R. G., Weber, A. P., Wesseler, J. H., & Zilberman, D. Europe’s farm to fork strategy and its comglomitment to biotechnology and organic farming: conflicting or complementary goals? Trends in plant science 2021, 26(6), 600–606. [Google Scholar]

- Naglis-Liepa K., Popluga D., Rivza P. Typology of Latvian agricultural farms in the context of mitigation of agricultural GHG emissions. 15th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference. 2015, Vol.2 Pages 513-520. ISSN 13142704.

- Muska A., Pilvere I., Nipers A. European Green Deal Objective for Sustainable Agriculture: Opportunities and Challenges to Reduce Pesticide Use, Emerging Science Journal 2025, Vol.9 No. 4. [CrossRef]

|

| EGD Target | Most Effective Practices | Co-Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| GHG Reduction (-55%) | Optimize feed efficiency, Methane inhibitors | Lower synthetic fertilizer use, Improved animal welfare, Reduced ammonia emissions (air quality) |

| Improving air quality (reducing ammonia emissions) (25%) | Outdoor access, bedding and flooring materials, | Improved animal welfare, Reduced GHG emissions, |

| Nutrient Loss Reduction | Grazing season restrictions, limits on the density of farm animals in pasture, Rotational grazing, | Reduced eutrophication, Reduced ammonia emissions (air quality), Improved freshwater Biodiversity enhancement, Soil organic carbon retention quality, Improved Animal welfare, biodiversity and landscape elements |

| Animal Welfare | Outdoor access, Grazing access, bedding and flooring materials, | Lower antimicrobial use, Higher productivity, Reduced veterinary costs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).