1. Introduction

The traditional production system for Iberian pigs is deeply embedded in the cultural, ecological and economic heritage of southwestern Spain and Portugal [

1,

2]. It relies on extensive husbandry practices that utilise the

dehesa ecosystem, which provides forage resources such as acorns, grasses and shrubs [

3]. Iberian pig production accounts for around 10% of total Spanish pig census [

4], and within this sector, differentiated extensive fattening systems (

montanera and

cebo de campo) play a critical role in the utilisation of natural resources and the production of high-value meat products [

5,

6]. Despite its importance, this system faces increasing challenges related to environmental sustainability and market viability, particularly the intensification of practices that risk the overexploitation of

dehesa resources [

7] while also facing policy demands for demonstrable sustainability outcomes [

8]. These challenges require integrated assessment approaches that can guide both, individual farm management decisions and broader policy interventions to ensure the long-term sustainability of this traditional production system.

While previous research has addressed specific aspects of Iberian pig farming, such as animal performance, economic profitability or carbon footprint [

9,

10,

11]. However, most studies have examined these dimensions in isolation, overlooking their interdependencies. Moreover, comparative assessments between production models are scarce, and those that integrate environmental and economic outcomes within the same analytical framework remain limited [

12]. This gap is particularly relevant for policymaking and farm-level decision support, as it hinders the identification of production strategies that are both economically viable and environmentally efficient. Therefore, there is a pressing need for robust methodological approaches that can characterise these dimensions together under the operational complexity of real farms.

In this context, eco-efficiency analysis emerges as a valuable tool to assess the capacity of farms to generate economic value from a given set of inputs while minimising associated environmental impacts [

13], typically expressed as a ratio between economic performance and environmental impacts. Integrating farm-level economic indicators with life cycle assessment (LCA) provides a comprehensive evaluation of performance [

14,

15] within ecosystems such as the

dehesa. Despite its potential, the application of this integrated approach to Iberian pig systems remains incipient and underexplored. Furthermore, the structural diversity of Iberian pig farms is reflected by the coexistence of production systems defined by the Quality Standard [

16], which necessitates robust analytical frameworks to address this heterogeneity. Multivariate methods offer the opportunity to synthesise high-dimensional datasets and classify farms according to their technical, economic and environmental variables [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

The main aim of this paper is to identify eco-efficiency indicators that integrate economic and environmental dimensions in traditional Iberian pig farms located in the dehesa ecosystem. Our findings provide insights into the trade-offs and synergies between profitability and environmental efficiency, and offer relevant implications for farmers, researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders aiming to enhance the sustainability of extensive livestock farming systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Iberian Pig Production System

The study was conducted in the dehesa ecosystem, a traditional agrosilvopastoral system covering approximately 6.7 million hectares in the south-west of the Iberian Peninsula [

22]. These systems are characterised by woodlands of holm and cork oaks (

Quercus spp.), pastures, and shrubs, where extensive livestock farming coexists with other land uses [

23].

Iberian pigs are a medium-sized native breed, traditionally raised under extensive or semi-extensive conditions [

24]. Their feeding regime is based on a combination of compound feed and natural resources, depending on the season [

25]. The main productive categories are piglets (up to 23 kg of live weight), growers (between 60 and 100 kg) and fatteners (165 kg on average). According to the fattening management, Iberian pigs can be classified as

montanera fatteners, which are fed only natural resources (acorns and grass), or

cebo de campo fatteners, which are fed a combination of available natural resources (mainly pasture) and compound feed [

16]. The greater physical activity in extensive systems, together with the pigs’ age at slaughter (12 to 14 months), contributes to the high quality of Iberian pork [

24].

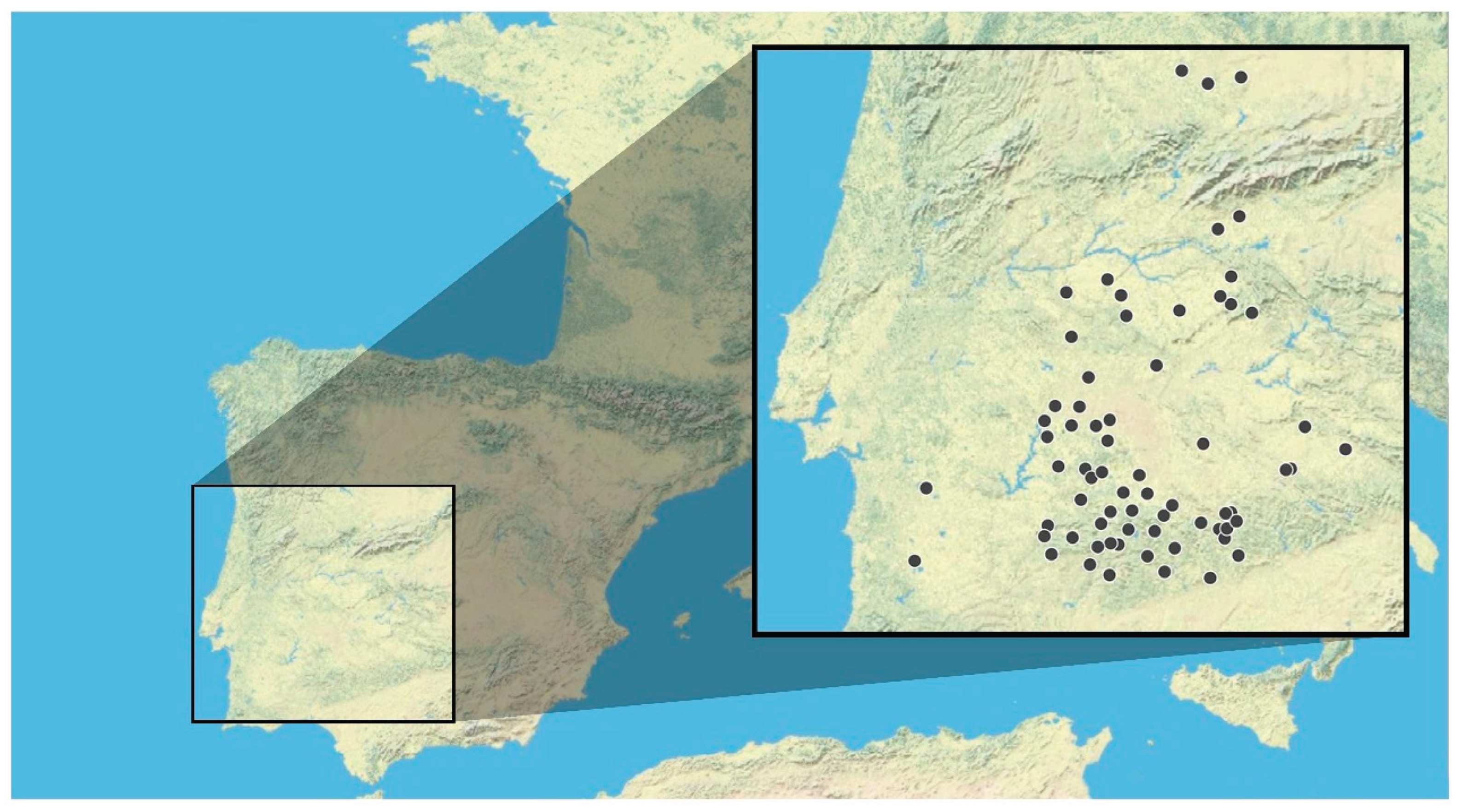

2.2. Data Acquisition

Data were collected from 68 Iberian pig farms through face-to-face interviews using structured questionnaires. The surveys were conducted in traditional Iberian pig farming areas within the

dehesa ecosystem (

Figure 1). The number of farms selected in each region was proportional to the regional production of

montanera fatteners to ensure a representative sample [

26]. The questionnaire was designed to capture the main structural, productive, economic, and social aspects of Iberian pig farms within the

dehesa ecosystem. Farm structure (area, facilities, machinery) and livestock inventory (pigs and other species) were considered as key indicators of farm-level productive potential [

27]. Management practices (reproductive, feeding and health) were assessed due to their impact on animal performance and welfare [

28], while work organisation and economic variables (labour and commercialisation) provided information to evaluate farm viability [

27,

29]. Social aspects, reflecting the role of farms in rural communities [

27], were assessed as social sustainability indicators. Integration with other agricultural activities was also considered to reflect the multifunctional role [

30] of extensive farms in the

dehesa ecosystem. Additionally, derived variables were calculated from the questionnaire data to facilitate the multivariate analysis.

2.3. Environmental Assessment

Environmental impacts were assessed for 36 of the 68 surveyed farms, representatively distributed across the study area, using life cycle assessment (LCA). The remaining 32 farms were excluded due to insufficient data for LCA did not exhibit substantial structural or productive differences compared to the 36 farms analysed (data not shown). The environmental results can therefore be considered representative of the overall sample. The functional unit was defined as one kilogram (kg) of live weight (LW) at the farm gate, following the system boundaries established by García-Gudiño et al. [

31].

The environmental impact categories assessed were: climate change (CC, kg CO₂ eq), acidification (AC, molc H+ eq), eutrophication (EU, kg PO43− eq), cumulative energy demand (CED, MJ) and land occupation (LO, m2·year). Characterisation was performed using the International Reference Life Cycle Data System (ILCD) and Centre of Environmental Science (CML) methods from the University of Leiden, implemented in SimaPro software (version 8.5.2.0, PRé Consultants, Amersfoort, The Netherlands).

Eco-efficiency indicators were calculated as the ratio of gross margin (€/kg LW) to environmental impact (e.g., kg CO₂ eq), and expressed in €/unit of impact. Gross margin was estimated as the difference between incomes from Iberian pig production and associated variable costs [

32,

33].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Multivariate statistical tools were used to identify different farm types among traditional Iberian pig farms in the

dehesa, based on technical, economic, and management data. The identification of farm types followed the methodology used by Giorgis et al. [

17], Gaspar et al. [

18], Toro-Mújica et al. [

19], Rivas et al. [

20] and Díaz-Gaona et al. [

21], which consists of three stages: variable selection, factor analysis, and cluster analysis.

From the initial 34 variables in the survey data, 26 variables with coefficient of variation (CV) > 50%) were selected. Data suitability was assessed by comparing Pearson (rPEAR) and partial (rPAR) correlations between the variables [

34] to eliminate uncorrelated variables and retain the variable with the highest CV from each correlated pair. This selection process yielded 13 variables described in

Table 1:

montanera income (%),

dehesa production (%),

dehesa land use (%), pig stocking rate (LU/ha), pig production (kg/ha), sows per 100 kg (n/100 kg), production per AWU (kg/AWU), income per AWU (€/AWU), sows (n), piglets output (n), area per AWU (ha/AWU), farm surface (ha), and

montanera production (kg/ha).

Factor analysis was then applied to reduce dimensionality and summarise variance. Variables were standardised to avoid scale effects. Principal components analysis was used as the extraction method to calculate factor scores for each farm [

20], with varimax rotation to ensure orthogonality of extracted factors [

35]. The Bartlett sphericity test and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index verified sample adequacy [

36,

37].

Finally, farms were classified into groups using cluster analysis based on individual factor scores. Hierarchical clustering was performed using Ward’s method with Euclidean, squared Euclidean, and Manhattan distances [

38]. The optimal number of clusters was determined using the Elbow method [

20] and validated through discriminant analysis and analysis of variance [

19].

Cluster groups were characterised and compared using Student’s t-test for economic, technical and environmental variables [

39]. To facilitate comparison between clusters, normalised indices (group mean/global mean) were calculated and presented graphically. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA, 2020).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Iberian Farms in the Dehesa Ecosystem

In the agrosilvopastoral system known as the

dehesa, traditional Iberian pig farms showed high structural and productive variability (see

Table 2). These systems were typically large in terms of land area and multiple livestock species, with Iberian pigs representing a significant proportion of the total livestock units. The stocking rates reflected the extensive nature of the livestock system.

Most farms followed a farrow-to-finish model, although approximately one-fifth specialised in rearing and fattening pigs purchased from other farms. Reproductive management was characterized by two farrowing cycles per year with high efficiency. While some piglets were sold before the fattening stage, the majority of fattened pigs were fed using only local natural resources, highlighting the sustainable nature of the system.

This production system demonstrated strong economic performance, with pig production serving as the main source of farm income. The fattening stage represented the vast majority of the economic value in Iberian pig production, emphasising its critical importance to the overall profitability of these farms. Given this structural and productive variability, a multivariate analysis was conducted to identify the main factors characterising these farming systems.

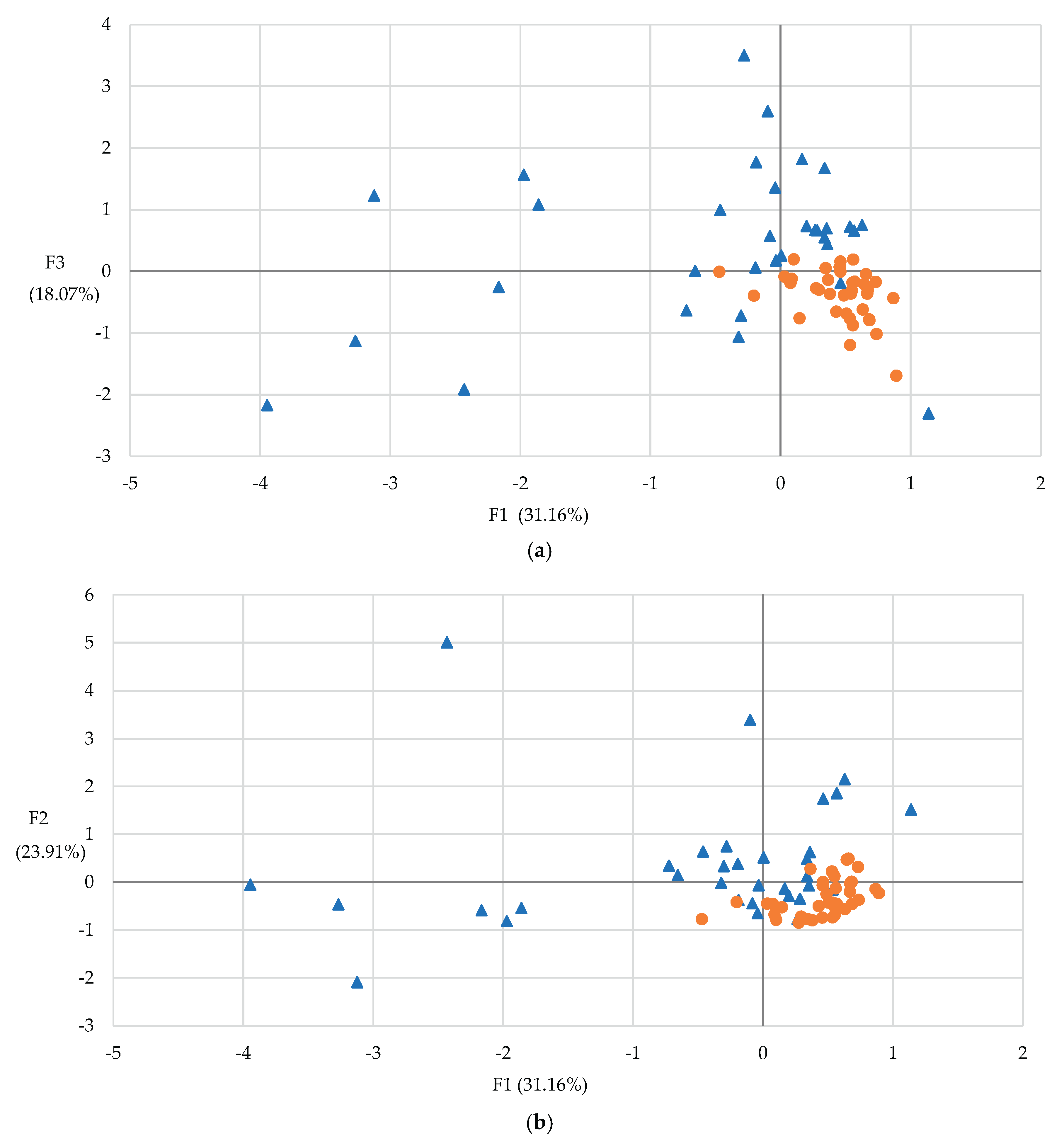

3.2. Factors Characterizing the Iberian Farms

The Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.05), and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.77, confirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The first three extracted factors explained a cumulative 73.14% of the total variance (

Table 3).

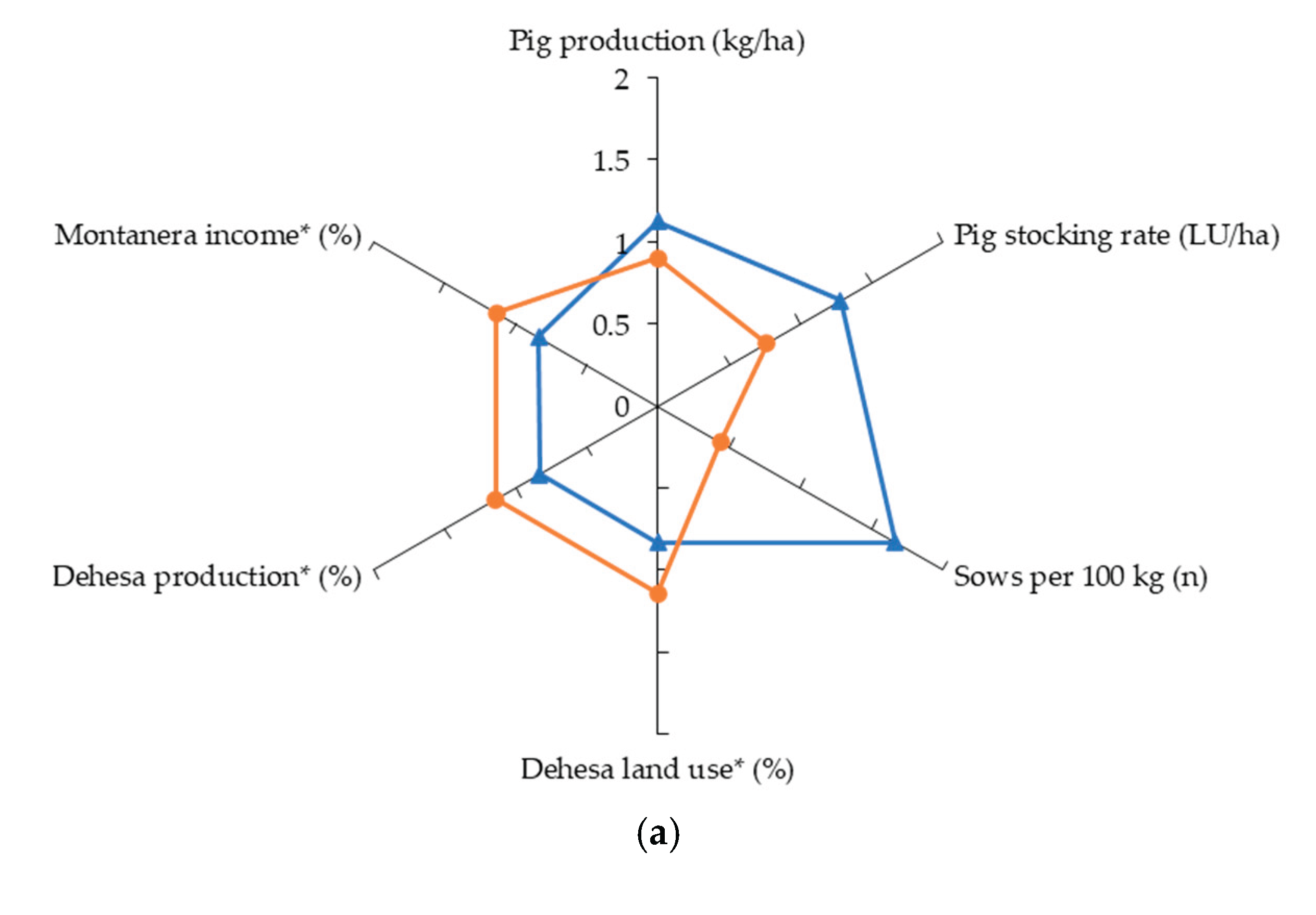

Three factors were extracted: Factor 1 (Production system) explained 31.16% of the total variance, with high loadings on dehesa-related variables; Factor 2 (Profitability) accounted for 23.91% focusing on productivity metrics; and Factor 3 (Land efficiency) explained 18.07% emphasising variables related to farm size. Based on these structural and economic dimensions, a classification of farms was performed to identify distinct management types.

Factor loadings revealed important relationships between variables and farm characteristics. Negative loadings on Factor 1 for pig stocking rate, pig production, and sows per 100 kg indicate that more intensive and efficient farms are less aligned with traditional dehesa management practices. Similarly, the negative loading of montanera production on Factor 3 reflects that larger farms tend to have lower production intensity per hectare of dehesa.

Based on these three factors, farms were classified into distinct management types to better understand the diversity within the Iberian pig production system in the dehesa.

3.3. Iberian Farm Types in the Dehesa Ecosystem

Cluster analysis using Ward's method identified two distinct groups. Group I concentrated 45.59% of farms (n=31) and was defined as Iberian pig farms with multiple production phases, denominated Mixed-orientation Farms (MF). Group II included 54.41% of farms (n=37) was defined as Farrow-to-finish farms specialized in acorn-based fattening was denominated Acorn-Fed Farms (AF). The scores for the three factors differentiated significantly between the two groups of farms, defining the main characteristics of each farm type (

Table 4). AF showed greater homogeneity in values, while MF presented higher dispersion across the three factors (

Figure 2).

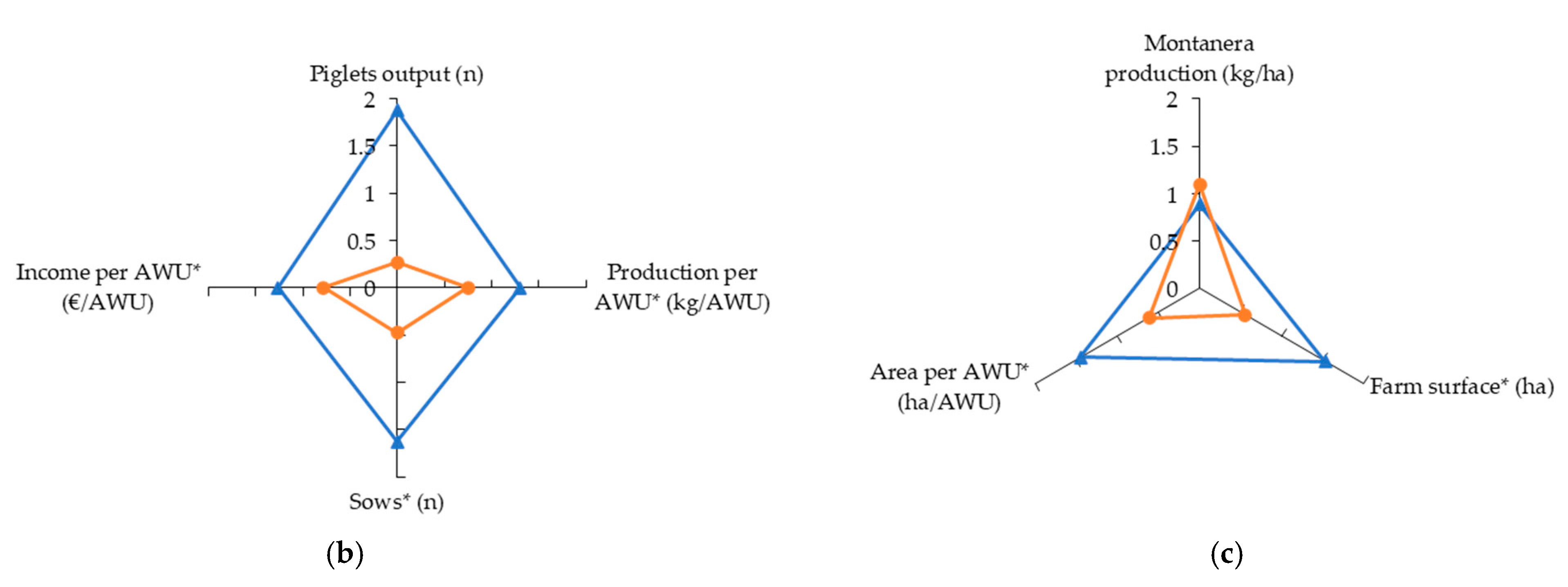

3.4. Environmental Performance by Farm Type

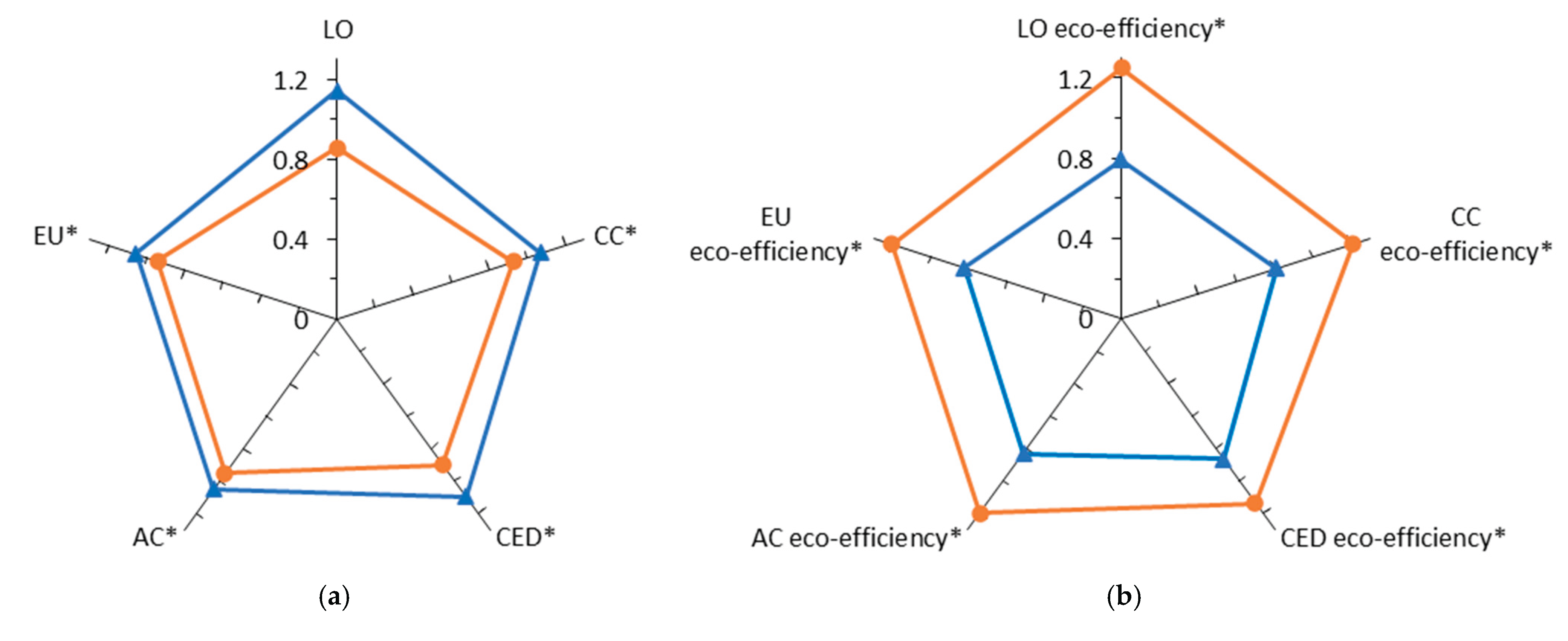

Having identified these two farm types, their environmental performance was compared to assess the sustainability implications of each management approach. Environmental impacts differed significantly between Iberian farm types in terms of CC, AC, EU, and CED, with AF showing lower impacts per kilogram of live weight produced compared to MF. No differences were found in LO impact among Iberian farm types. Eco-efficiency indicators, expressed as the ratio between gross margin and environmental impact, showed significantly better values in AF (

Table 5). The gross margin per kilogram of live weight was 15% higher in AF compared to MF (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural Diversity of Iberian Pig Farms in the Dehesa Ecosystem

The traditional Iberian pig production system is a distinctive form of extensive livestock farming that is closely associated with a particular territory and agrosilvopastoral knowledge [

16,

40]. A wide range of production models coexist within this framework, differing in terms of farm structure, herd composition, management of natural resources, and degree of integration with the

dehesa ecosystem [

41]. This heterogeneity poses significant challenges for designing and implementing uniform sustainability policies, and highlights the need for integrative indicators that can capture economic and environmental performance in diverse farming contexts.

This structural heterogeneity is confirmed by the data obtained in the present study, which reveal high variability consistent with previous typological analyses of

dehesa livestock farming systems [

40,

42,

43,

44]. Most farms operate as multi-species livestock systems, combining Iberian pigs with beef cattle and/or sheep, a pattern characteristic of the

dehesa ecosystem [

41]. The average farm surface area was comparable to values reported in other studies [

41,

45], and the mean stocking rate of 0.49 LU/ha reflects the low-density management typical of this ecosystem. This figure is consistent with other estimates for similar multi-species systems in the

dehesa ecosystem [

40,

41].

Despite the extensive nature of these systems, the Iberian pig breed accounted for a significant proportion of the productive structure, representing over one-third of the total livestock units and generating almost 60% of the total farm revenue. This confirms the central economic role of the Iberian pig within these multi-species farms and supports previous findings on the high added value of

montanera fatteners [

41,

44]. In many cases, pigs are fattened only on local natural resources, which enhances the environmental and cultural value of the final product, while providing economic incentives for the conservation of the

dehesa and the continuation of traditional extensive management practices.

In summary, the present study supports the view that Iberian pig farming in the

dehesa is structurally diverse, economically significant, and deeply rooted in the use of natural resources [

10,

46]. This complexity requires tailored policy tools that account for the diversity of farm types, their territorial embeddedness, and their capacity to ability to provide economic benefits and ecosystem services.

4.2. Key Differentiation Factors and Implications for Eco-Efficiency

The multivariate analysis revealed a robust factorial structure, with the first three extracted factors accounting for 73.14% of the total variance, effectively capturing the main dimensions of farm differentiation. This is considered a satisfactory percentage in the context of farm typification studies [

47] and aligns with previous research in terms of the proportion of variance explained and the number of dimensions retained relative to the number of original variables [

17,

19,

20,

39,

42]. These results provide a solid foundation for characterizing distinct farm types and subsequently evaluating eco-efficiency.

The three factors identified reflect key aspects of management practices and the use of natural resources, as described below:

The first factor, denominated "Production system", reflects the balance between intensive management and use of natural resources. Farms with high scores are more integrated with the

dehesa ecosystem, relying extensively on

montanera finishing and natural resources. Conversely, farms with lower scores exhibit more intensive management and higher stocking rates. This gradient demonstrates the contrast between traditional acorn-based finishing and intensified production through supplemental feeding, in line with findings from previous

dehesa studies [

42,

43], and captures the inverse relationship between intensification and natural resource use.

The second factor, termed 'Profitability', reflects aspects of scalability and labour productivity, which are closely interrelated [

48]. It refers to a farm's ability to increase the number of reproductive sows without proportionally increasing labour input, thereby achieving a higher production output. Therefore, the second factor reflects how an increased number of Iberian sows can generate additional commercial opportunities (such as piglet, grower and finisher sales) while also improving labour productivity. These improvements contribute to higher economic returns. However, these economic benefits must be balanced against environmental impacts and the rising costs of external inputs (such as compound feed), which can reduce profitability [

49].

The third factor, referred to as "Land efficiency," emphasises variables to farm size and land-to-labour ratios. Farms with larger surface areas exhibit higher area per worker and lower montanera production per hectare, reflecting the extensive nature of traditional

dehesa systems [

42]. Rather than indicating inefficiency, this pattern corresponds to a land-based production model in which eco-efficiency plays a central role: farms that manage land resources prudently, in accordance with ecological constraints, tend to minimise environmental impacts per unit of product [

31]. In contrast to other studies where farm area was included in the first factor [

19,

21], in this case it emerged as the third factor, possibly due to the analytical focus of this study, which prioritised efficiency-related criteria over the structural characterisation of the farms.

Together, these three factors provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the structural diversity of traditional Iberian pig farms and lay the groundwork for eco-efficiency assessment. Identifying them allows us to evaluate how different Iberian farm types balance productivity, economic performance, and environmental sustainability within the dehesa ecosystem.

4.3. Production Models of Iberian Pig Farms in the Dehesa Ecosystem

The classification of Iberian pig farms into two types, MF and AF, reveals the structural and strategic diversity that characterizes production systems in the dehesa ecosystem. Rather than indicating a linear transition from traditional to modern systems, this typology reflects different strategies of adaptation to market conditions.

AF represent a production model that is aligned with the

dehesa ecosystem. Their consistent factor scores suggest a homogeneous system, based on farrow-to-finish farms specialized in acorn-based fattening. This strong dependence on natural resources, particularly acorns, limits intensification but enhances product differentiation and integration with the ecosystem [

16]. Their economic performance is sustained by the production of

montanera fatteners, supporting a model centred on quality, tradition, and low external input use, which is consistent with other extensive livestock systems [

50].

In contrast, MF adopt a more diversified approach. These farms manage a significantly higher number of sows, achieve higher labour productivity, and produce multiple pig categories for the market. The greater variability observed within this group reflects a wide range of management strategies, degrees of intensification, and levels of dependency on external inputs [

51]. This model increases the capacity to adapt to market fluctuations but also implies higher external resource demands [

10]. Thus, MF achieve higher economic efficiency through diversification [

52].

Regarding factor scores, AF scored highest on Factor 1 (Production System), confirming their alignment with natural resource use and extensive practices. MF stood out in Factor 2 (Profitability), due to their scalability and labour efficiency. For Factor 3 (Land Efficiency), both farm types reached similar levels in

montanera productivity, constrained by regulatory stocking limits [

16].

These two types of farms illustrate complementary roles within Iberian pig production systems. AF contribute to preserving the environmental and cultural functions of the

dehesa ecosystem, offering a production system that adds value through tradition and sustainability [

53]. On the other hand, MF provide adaptability and volume to the market, ensuring competitiveness and employment [

10]. Rather than being in competition, these models respond to different market needs and reinforce the multifunctionality of the

dehesa ecosystem.

Figure 3 clearly illustrates this complementarity, showing how the relative positioning of MF and AF across the three main factors reflects their contrasting yet complementary contributions to sustainable Iberian pig production. This approach balances economic viability with the conservation of the

dehesa ecosystem through natural resources use.

4.4. Environmental Performance and Sustainability Implications

The results of the environmental assessment clearly show that AF perform better than MF in several environmental impact categories, with reductions in CC, AC, EU and CED ranging from 9% to 18% (

Figure 4a). These differences reflect a greater integration of AF within the

dehesa ecosystem, due to the optimised use of natural resources and reduced dependency on external feed inputs [

11,

31,

54]. This efficient use of resources is consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the environmental benefits of extensive systems [

31,

55,

56]. Beyond their environmental performance, AF also demonstrate markedly higher eco-efficiency indicators, with economic returns that are 32% to 59% higher than those of MF across all indicators assessed (

Figure 4b).

Although differences in LO were not statistically significant, the eco-efficiency analysis revealed that AF showed 59% higher LO eco-efficiency than MF. This suggests that AF can generate greater economic value per unit of land used. This result is linked to the high market price of

montanera fatteners [

51], which supports more sustainable land use practices. In contrast, the difference in CED eco-efficiency was smaller (32%) between farm types, probably due to similar reliance on compound feeds during the growing phase [

57]. This is a shared constraint that still limits the sustainability potential of traditional Iberian farms.

In summary, AF stand out not only for their lower environmental impacts, but also for their higher returns per unit of environmental impact. These results suggest that AF can represent a viable model of ecologically self-regulating and economically sustainable livestock systems, supporting the conservation of the dehesa ecosystem while ensuring farm profitability.

4.5. Implications for Agricultural Policy and Sustainable Development

Several authors have emphasised the significant potential of European policies to promote sustainable livestock farming by providing economic support for environmentally friendly and low-input systems [

58]. The findings of this study provide empirical evidence in support of agricultural policies that prioritise eco-efficient models, such as farrow-to-finish farms that specialise in acorn-based fattening. Compared to intensive production systems, these farms demonstrate superior environmental performance and ecosystem preservation, along with reduced external input. However, despite aligning with these policy objectives, Iberian pig production in the

dehesa ecosystem is excluded from subsidies [

59], revealing a policy inconsistency that overlooks their environmental contributions.

Building on these insights, the results reinforce the importance of integrating eco-efficiency metrics into sustainability assessments and agricultural policy frameworks, particularly in support of extensive livestock systems within Mediterranean agroecosystems. These findings challenge the common assumption that sustainability necessarily entails productivity losses [

60] and highlight the need for policy instruments that explicitly reward practices that enhance eco-efficiency. Policymakers should consider eco-efficiency as a key criterion when allocating subsidies, moving beyond simple environmental or economic indicators towards more holistic sustainability measures.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Perspectives

The study design limits its ability to capture temporal dynamics, particularly the interannual variability in acorn production [

61], which has a strong influence on

montanera fattening. AF are particularly vulnerable to years of low acorn production, which can result in economic uncertainty and impact their long-term viability despite their superior eco-efficiency. Future research should assess the resilience of both farm types to variability in acorn production and market fluctuations, as well as their associated economic impacts.

Furthermore, the considerable variability observed within MF suggests the presence of distinct subtypes, highlighting the necessity for further investigation to better characterise this heterogeneity.

Additionally, adapting LCA methodologies to evaluate

dehesa ecosystems, including all livestock species integrated within these farms, including all livestock species integrated within these farms, could enhance eco-efficiency estimates by providing a more holistic understanding of natural resource use, environmental impacts, and economic returns. This approach would be particularly relevant given that multi-species livestock systems have been documented as more sustainable than single-species farms [

30,

62,

63,

64], making it essential to capture these synergistic effects in LCA studies. Extending this framework to other extensive Mediterranean livestock systems would improve its generalisability and inform sustainable agricultural policies in comparable agroecosystems.

5. Conclusions

The assumption that environmental sustainability in livestock farming necessarily involves economic trade-offs should be critically reconsidered. Evidence from traditional Iberian pig production indicates that integration with the dehesa ecosystem can boost profitability while minimising environmental impact. AF achieve notably higher gross margins (approximately 15% above MF), alongside superior eco-efficiency indicators, exemplifying this. These findings challenge the status quo of conventional livestock systems and support the development of regenerative production strategies, in which ecosystem services provide economic resilience.

The considerable structural diversity among Iberian pig farms shows that standard technical recommendations are insufficient, highlighting the need for solutions tailored to this heterogeneity. MF, characterised by diversified production phases and a greater reliance on external inputs, play a crucial role in enhancing market adaptability and production volume. Their complexity emphasises the importance of appropriately management strategies that effectively balance productivity with environmental and economic sustainability goals.

Given the structural complexity, eco-efficiency provides a robust framework for assessing and promoting the sustainability of traditional livestock systems, facilitating the identification of synergies and trade-offs that might otherwise remain unnoticed. Future assessments and policy instruments should prioritise an integrated approach that recognises the multifunctional roles of extensive farming systems and moves beyond isolated, sector-specific perspectives.

Ultimately, this framework provides a replicable model for assessing sustainability of Mediterranean agroecosystems. As climate pressures and resource constraints intensify, the ability to monitor and optimise eco-efficiency will be essential for the survival of traditional farming systems. The approach developed in this study establishes a foundation to support the transition towards production models that are simultaneously economically viable, environmentally regenerative, and socially resilient, demonstrating adaptability to change. Furthermore, the proposed eco-efficiency indicators can serve as practical tools for benchmarking farm performance and informing evidence-based policies that support more sustainable and resilient livestock systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P. and I.B.P.; methodology, J.G.G., J.P. and I.B.P.; formal analysis, J.G.G. and J.P.; investigation, J.G.G.; resources, J.P.; data curation, J.G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.G.; writing—review and editing, J.P., M.F.F., E.A., and I.B.P.; supervision, J.P. and I.B.P.; project administration, I.B.P.; funding acquisition, I.B.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Institute for Agricultural and Food Research and Technology, grant number RTA2013-00063-C03-02.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to project IP rules.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank POD Dehesa de Extremadura, AECERIBER, ACPA and farmers for their support. CERCA from Generalitat de Catalunya and Consolidated Research Groups (2021 SGR 00461) are acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lopez-Bote, C.J. Sustained utilization of the Iberian pig breed. Meat Sci. 1998, 49, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goracci, J and Camilli, F. Husbandry. In Book Animal Husbandry - Beliefs, Facts and Reality; Kukovics, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2024; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Estévez, V.; García, A.; Peña, F.; Gómez, A.G. Foraging of Iberian fattening pigs grazing natural pasture in the dehesa. Livest. Sci. 2009, 120, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Lorido, L.; Estévez, M.; Ventanas, J.; Ventanas, S. Comparative study between Serrano and Iberian dry-cured hams in relation to the application of high hydrostatic pressure and temporal sensory perceptions. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gudiño, J.; Blanco-Penedo, I.; Gispert, M.; Brun, A.; Perea, J.; Font-i-Furnols, M. Understanding consumers’ perceptions towards Iberian pig production and animal welfare. Meat Sci. 2020, 172, 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez, J.; Contador, J.F.L.; Schnabel, S.; Fernández, M.P.; Valderrama, J.M. A model-based integrated assessment of land degradation by water erosion in a valuable Spanish rangeland. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 55, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal, COM (2019) 640 Final, Brussels. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Horrillo, A.; Gaspar, A.; Escribano, M. Organic farming as a strategy to reduce carbon footprint in dehesa agroecosystems: A case study comparing different livestock products. Animals 2020, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrillo, A.; Gaspar, P.; Muñoz, Á.; Escribano, M.; González, E. Fattening Iberian Pigs Indoors vs. Outdoors: Production Performance and Market Value. Animals 2023, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Palomo, C.; Aguilera, E.; Llorente, M.; Díaz-Gaona, C.; Moreno, G.; Rodríguez-Estévez, V. Free-range acorn feeding results in negative carbon footprint of Iberian pig production in the dehesa agro-forestry system. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, A.; de Olde, E.M.; Mostert, P.F.; de Boer, I.J.M. A review of European models to assess the sustainability performance of livestock production systems. Agric. Syst. 2020, 182, 102842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępień, S.; Czyżewski, B.; Sapa, A.; Borychowski, M.; Poczta, W.; Poczta-Wajda, A. Eco-efficiency of small-scale farming in Poland and its institutional drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, S.; Iribarren, D.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. The link between operational efficiency and environmental impacts. A joint application of Life Cycle Assessment and Data Envelopment Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iribarren, D.; Hospido, A.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. Benchmarking environmental and operational parameters through eco-efficiency criteria for dairy farms. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 1786–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Decreto 4/2014, de 10 de Enero, por el Que se Aprueba la Norma de Calidad Para la Carne, el Jamón, la Paleta y la Caña de Lomo Ibérico. Available online: http://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2014/01/11/pdfs/BOE-A-2014-318.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Giorgis, A.; Perea, J.; García, A.; Gómez-Castro, A.G.; Angón, E. , Larrea, A. Technical and economical characterization and typology of dairy farms in La Pampa (Argentine). Rev. Científica, FCV-LUZ.

- Gaspar, P.; Escribano, A.J.; Mesías, F.J.; Escribano, M.; Pulido, F. Goat systems of Villuercas-Ibores area in SW Spain: Problems and perspectives of traditional farming systems. Small Rumin. Res. 2011, 97, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Mujica, P.; García, A.; Gómez-Castro, A.; Perea, J.; Rodríguez-Estévez, V. Angón, E.; Barba, C. Organic dairy sheep farms in south-central Spain: Typologies according to livestock management and economic variables. Small Rumin. Res. 2012, 104, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, J.; Perea, J.; Angón, E.; Barba, C.; Morantes, M.; Dios-Palomares, R.; García, A. Diversity in the dry land mixed system and viability of dairy sheep farming. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 14, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Gaona, C.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, M.; Rucabado-Palomar, T.; Rodríguez-Estévez, V. A typological characterization of organic livestock farms in the Natural Park Sierra de Grazalema based on technical and economic variables. Sustain. 2019, 11, 6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrillo, A.; Gaspar, P.; Mesiás, F.J.; Elghannam, A.; Escribano, M. Understanding the barriers and exploring the possibilities of the organic livestock sector in dehesa agroforestry systems: A multi-actor approach for effective diagnosis. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2019, 35, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, M.; Díaz-Caro, C.; Mesias, F.J. A participative approach to develop sustainability indicators for dehesa agroforestry farms. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640–641, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, R.; García-Casco, J.; Lara, L.; Palma-Granados, P.; Izquierdo, M.; Hernández, F.; Dieguez, E.; Duarte, J.L.; Batorek-Lukac, N. Pig. In Book European Local Pig Breeds—Diversity and Performance A Study of Project TREASURE; Candek-Potokar, M., Nieto, R., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2019; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, J.; Albarrán, A.; García-Casco, J.M. Extensive Iberian pig production grazing systems. In Proceedings of the 21st General Meeting of the European Grassland Federation, Badajoz, Spain, 3–6 April 2006; pp. 635–645. [Google Scholar]

- Registro Informativo de Organismos Independientes de Control del Ibérico (RIBER). Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/alimentacion/temas/control-calidad/mesa-iberico/riber-publico/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Lebacq, T.; Baret, P.V.; Stilmant, D. Sustainability indicators for livestock farming. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orihuela, A. Review: Management of livestock behavior to improve welfare and production. Animal 2021, 15, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cournut, S.; Chauvat, S.; Correa, P.; Dos Santos Filho, J.C.; Diéguez, F.; Hostiou, N.; Pham, D.K.; Servière, G.; Sraïri, M.T.; Turlot, A.; et al. Analyzing work organization on livestock farm by the Work Assessment Method. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Barth, K.; Benoit, M.; Brock, C.; Destruel, M.; Dumont, B.; Grillot, M.; Hübner, S.; Magne, M.A.; Moerman, M.; et al. Potential of multi-species livestock farming to improve the sustainability of livestock farms: A review. Agric. Syst. 2020, 181, 102821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gudiño, J.; Monteiro, A.N.T.R.; Espagnol, S.; Blanco-Penedo, I.; Garcia-Launay, F. Life cycle assessment of Iberian traditional pig production system in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angón, E.; García, A.; Perea, J.; Acero, R.; Toro-Mújica, P.; Pacheco, H.; González, A. Techincal efficiency and viability of grazing dairy cattle systems in la Pampa, Argentine. Agrociencia 2013, 47, 443–456. [Google Scholar]

- Morantes, M.; Dios-Palomares, R.; Peña, M.E.; Rivas, J.; Perea, J.; García-Martínez, A. Management and productivity of dairy sheep production systems in Castilla-La Mancha, Spain. Small Rumin. Res. 2017, 149, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, M.G.; Serdino, J.; Gaspa, G.; Urgeghe, P.; Ibba, I. ; Contu, M; Fresi, P.; Macciotta, N.P.P. Derivation of multivariate indices of milk composition, coagulation properties, and individual cheese yield in dairy sheep. J. Dairy Sci. 2016. 99. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, XX(1), 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerny, B.A.; Kaiser, H.F. A study of a measure of sampling adequacy for factor-analytic correlation matrices. Multivariate Behav. Res. 1977, 12, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köbrich, C.; Rehman, T.; Khan, M. Typification of farming systems for constructing representative farm models: Two illustrations of the application of multi-variate analyses in Chile and Pakistan. Agric. Syst. 2003, 76, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, J.; Perea, J.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Espinosa-García, J.A.; Toro-Mújica, P.; Feijoo, M.; Barba, C.; García, A. Structural and technological characterization of tropical smallholder farms of dual-purpose cattle in Mexico. Animals 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Muñoz, J.; Blanco-Penedo, I.; Barba, C.; Angón, E.; García-Martínez, A. Organic beef farming in Spain: typology according to livestock management and economic variables. Rev. Científica 2014, 24, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.A.; Gaspar, P.; Mesias, F.J. Economic analysis of scenarios for the sustainability of extensive livestock farming in Spain under the CAP. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, P.; Mesías, F.J.; Escribano, M.; Rodriguez-Ledesma, A.; Pulido, F. Economic and management characterization of dehesa farms: Implications for their sustainability. Agrofor. Syst. 2007, 71, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, P.; Escribano, M.; Mesías, F.J.; De Ledesma, A.R.; Pulido, F. Sheep farms in the Spanish rangelands (dehesas): Typologies according to livestock management and economic indicators. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 74, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Perea, J.; Acero, R.; Angón, E.; Toro, P.; Rodríguez, V.; Gómez-Castro, A.G. Structural characterization of extensive farms in andalusian dehesas. Arch. Zootec. 2010, 59, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto-Molina, F.; Gómez-Cabrera, A.; Guerrero-Ginel, J.E.; Garrido-Varo, A.; Adame-Siles, J.A.; Pérez-Marín, D.C. Caracterización y tipificación de explotaciones de dehesa asociadas a cooperativas: un caso de estudio en España. Rev. Mex. Ciencias Pecu. 2018, 9, 812–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milán, M.J.; Bartolomé, J.; Quintanilla, R.; García-Cachán, M.D.; Espejo, M.; Herráiz, P.L.; Sánchez-Recio, J.M.; Piedrafita, J. Structural characterisation and typology of beef cattle farms of Spanish wooded rangelands (dehesas). Livest. Sci. 2006, 99, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Estevez, V.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, M.; Arce, C.; García, A.R.; Perea, J.M.; Gustavo, A. Consumption of Acorns by Finishing Iberian Pigs and Their Function in the Conservation of the Dehesa Agroecosystem. In Book Agroforestry for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services—Science and Practice; Kaonga, M., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhorta, N. Investigación de mercadose, 4th ed.; Pearson: Atlacomulco, Mexico, 2004; pp. 532–558. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagenberg, C.P.A.; de Haas, Y.; Hogeveen, H.; van Krimpen, M.M.; Meuwissen, M.P.M.; van Middelaar, C.E.; Rodenburg, T.B. Animal Board Invited Review: Comparing conventional and organic livestock production systems on different aspects of sustainability. Animal 2017, 11, 1839–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, D.; Blair, K.J. Review: Sustainable livestock systems: anticipating demand-side challenges. Animal 2021, 15, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernués, A.; Ruiz, R.; Olaizola, A.; Villalba, D.; Casasús, I. Sustainability of pasture-based livestock farming systems in the European Mediterranean context: Synergies and trade-offs. Livest. Sci. 2011, 139, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, P.; Mesías, F.J.; Escribano, M.; Pulido, F. Sustainability in Spanish extensive farms (Dehesas): An economic and management indicator-based evaluation. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 62, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Grace, D.; Njuki, J.; Johnson, N.; Enahoro, D.; Silvestri, S.; Rufino, M.C. The roles of livestock in developing countries. Animal 2013, 7, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A.J.; Salazar-Ordoñez, M.; Granado-Díaz, R.; Rodríguez-Entrena, M. Consumers' preferences for traditional meat products: production system and objective quality cues in Iberian ham. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 1987–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espagnol., S.; Demartini, J. 8–10 October 2014, Espagnol. S.; Demartini, J. Environmental impacts of extensive outdoor pig production systems in Corsica. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference Life Cycle Assessment Agri-Food Sector (LCA Food 2014), San Francisco, CA, USA, ; pp. 364–371.

- Dourmad, J.Y.; Ryschawy, J.; Trousson, T.; Bonneau, M.; González, J.; Houwers, H.W.; Hviid, M.; Zimmer, C.; Nguyen, T.L.; Morgensen, L. Evaluating environmental impacts of contrasting pig farming systems with life cycle assessment. Animal 2014, 8, 2027–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, A.N.T.R.; Wilfart, A.; Utzeri, V.; Batorek, N.; Tomazin, U.; Nanni, L.; Čandek-Potokar, M.; Fontanesi, L.; Garcia-Launay, F. Environmental impacts of pig production systems using European local breeds: The contribution of carbon sequestration and emissions from grazing. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Estévez, V.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, M.; García, A.; Gómez-Castro, A.G. Feed conversion rate and estimated energy balance of free grazing Iberian pigs. Livest. Sci. 2010, 132, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scown, M.W.; Brady, M.V.; Nicholas, K.A. Billions in Misspent EU Agricultural Subsidies Could Support the Sustainable Development Goals. One Earth 2020, 3, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, M.; Horrillo, A.; Mesías, F.J. Greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration in organic dehesa livestock farms. Does technical-economic management matters? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 372, 133779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, L.; Zotte, A.D.; Piccini, I.; Bondesan, V.; Vitaliano, G.; Piazzon, C.; Manca, E.; Rigo, E.; Berton, M.; Gallo, L. Economic Resilience in Intensive and Extensive Pig Farming Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejerina, D.; García-Torres, S.; Cabeza de Vaca, M.; Cava, R.; Vázquez, F.M. Interannual variability and evolution during the montanera period of Holm oak (Quercus rotundifolia Lam.) acorns. Spanish J. Agric. Res. 2010, 8, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugnier, S.; Husson, C.; Cournut, S. Why and how farmers manage mixed cattle-sheep farming systems and cope with economic, climatic and workforce-related hazards. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowntree, J.E.; Stanley, P.L.; Maciel, I.C.F.; Thorbecke, M.; Rosenzweig, S.T.; Hancock, D.W.; Guzman, A.; Raven, M.R. Ecosystem Impacts and Productive Capacity of a Multi-Species Pastured Livestock System. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 544984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, B.; Puillet, L.; Martin, G.; Savietto, D.; Aubin, J.; Ingrand, S.; Niderkorn, V.; Steinmetz, L.; Thomas, M. Incorporating Diversity Into Animal Production Systems Can Increase Their Performance and Strengthen Their Resilience. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).