1. Introduction

Polyamide fibers, particularly nylon 6 and nylon 6.6, represent a cornerstone of the contemporary textile industry. Their widespread application, ranging from high-performance apparel to advanced technical textiles, stems from their exceptional physiomechanical properties, including superior tensile strength, elasticity, and remarkable abrasion resistance [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The coloration of these versatile materials is predominantly achieved through the use of acid dyes, which form robust ionic interactions with the protonated amino groups inherent in the polyamide fiber structure. This interaction ensures excellent dye affinity, colorfastness, and the production of vibrant, durable shades [

5,

6].

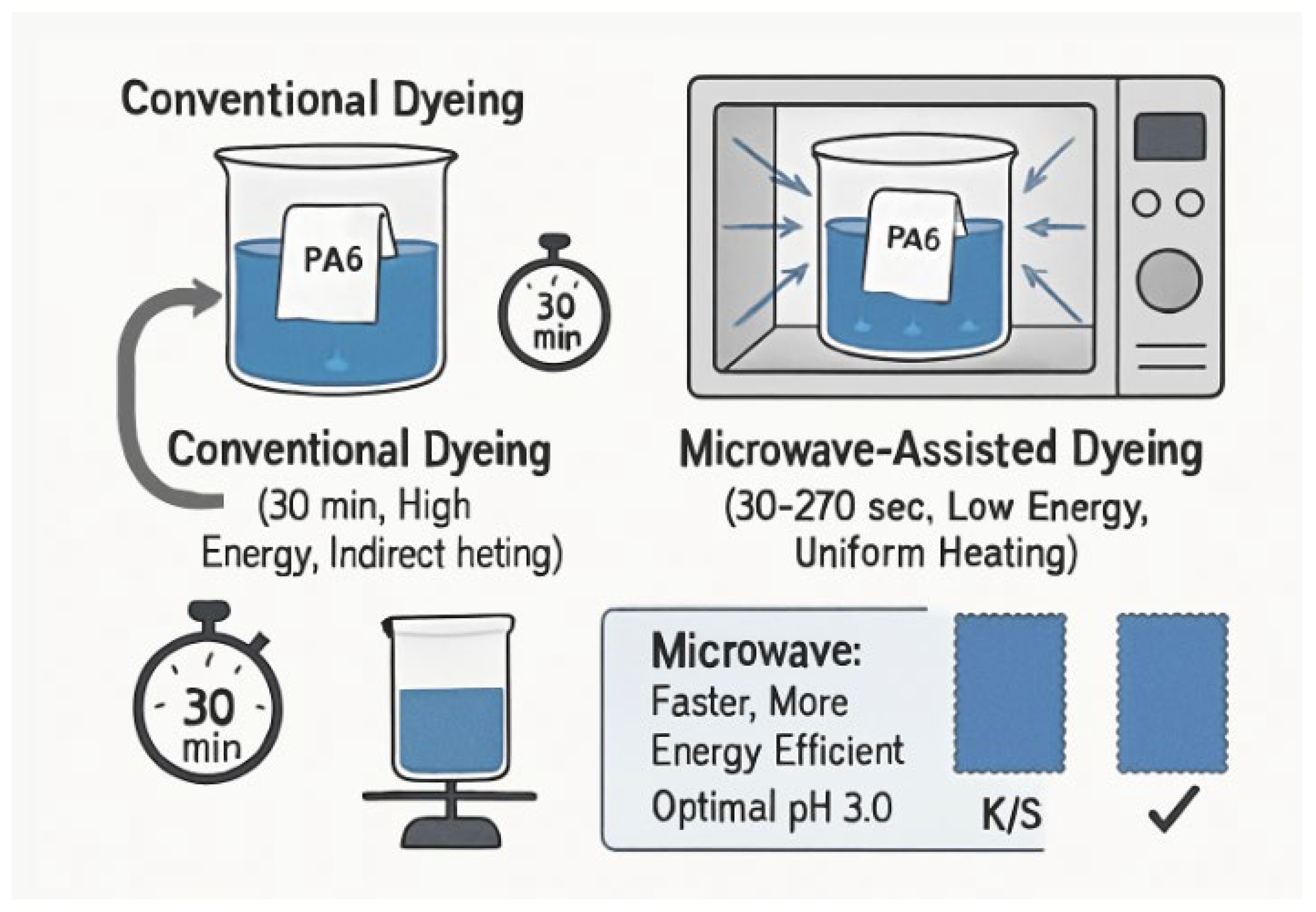

In response to the growing demand for sustainable and efficient manufacturing paradigms, microwave-assisted dyeing has emerged as a revolutionary alternative technology [

7,

8,

9,

10]. The fundamental principle underpinning microwave heating is dielectric heating, whereby electromagnetic radiation, commonly at a frequency of 2.45 GHz, induces rapid molecular vibration and rotation of polar molecules, predominantly water, within the dyebath [

11,

12,

13]. This unique mechanism results in rapid, uniform, and volumetric heating throughout the entire dyeing system, a stark contrast to the slower, less uniform, and surface-to-core heat transfer characteristic of conventional heating methods [

14,

15]. This internal generation of heat promises to dramatically curtail processing times, reduce energy consumption, and enhance the kinetics of dye diffusion and fixation within the textile substrate [

16,

17].

Recent scholarly investigations have increasingly underscored the transformative potential of microwave technology across diverse textile applications [

18,

19,

20] For instance, studies have reported substantial reductions in dyeing time and notable improvements in color yield for microwave-assisted dyeing of cotton with reactive dyes [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

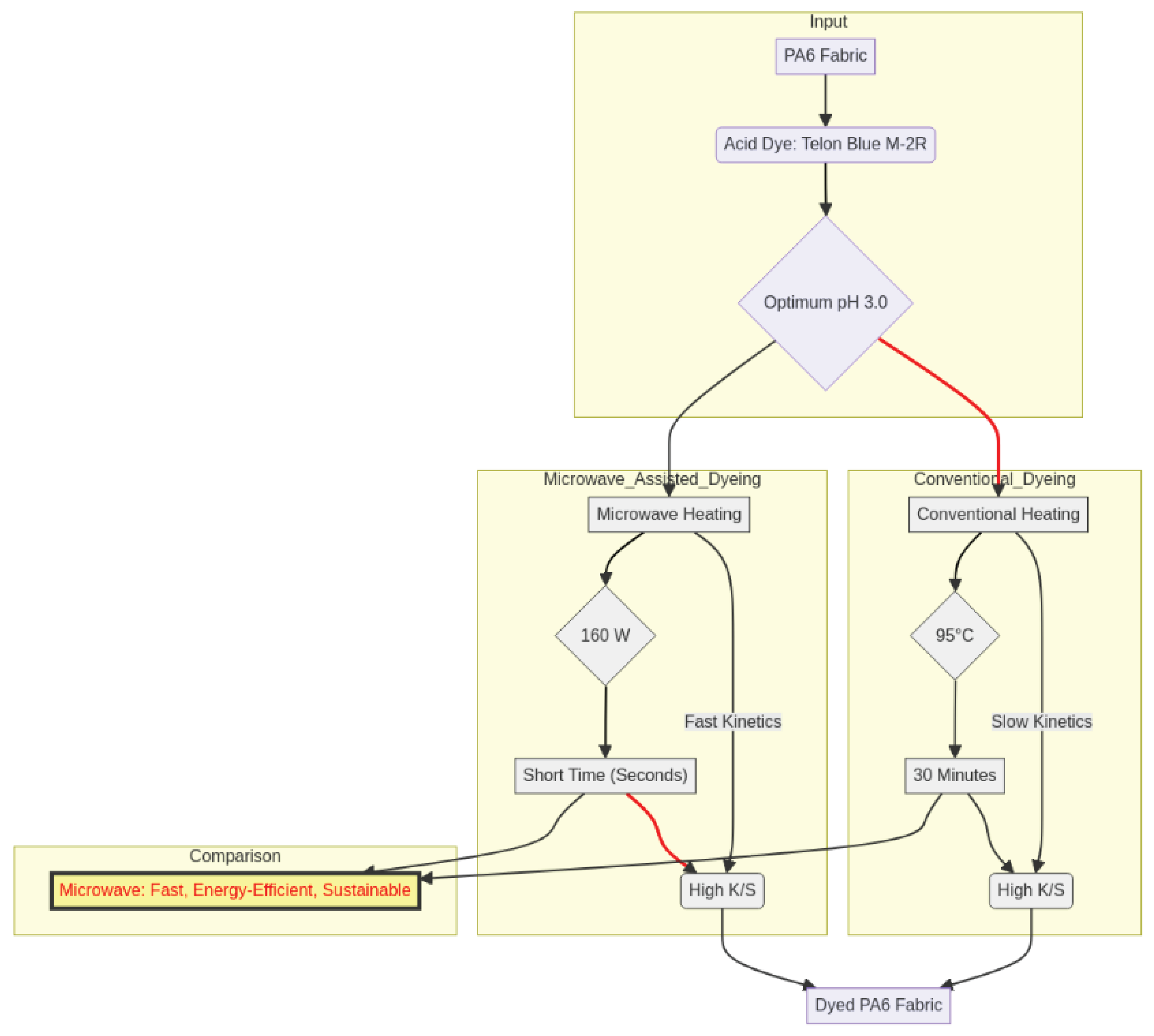

This study is designed to address the existing research gaps by conducting a detailed comparative analysis of both conventional and microwave-assisted dyeing techniques for polyamide 6 fabric utilizing a model acid dye (Telon Blue M-2R) [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. The research will systematically investigate the effects of key process parameters specifically temperature, dye concentration, dyeing time, and pH on the dyeing mechanism, ultimate dye uptake, and final color strength. The overarching goal is to furnish a robust scientific foundation that will facilitate the development of more efficient, economically viable dyeing protocols for polyamide textiles [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The substrate used for all dyeing experiments was a 100% polyamide 6 (PA6) fabric. The fabric was procured from Nurel Group (Turkey). Poliamide obtained from poly condensation of hexametylene diamine with adipic acid, so the nylon contains amide groups, carboxylic end groups, amino end groups, a greater part of the polar groups are amide groups. There are few strongly hydrophilic groups, fiber swelling is little and dye penetration is difficult [

2].

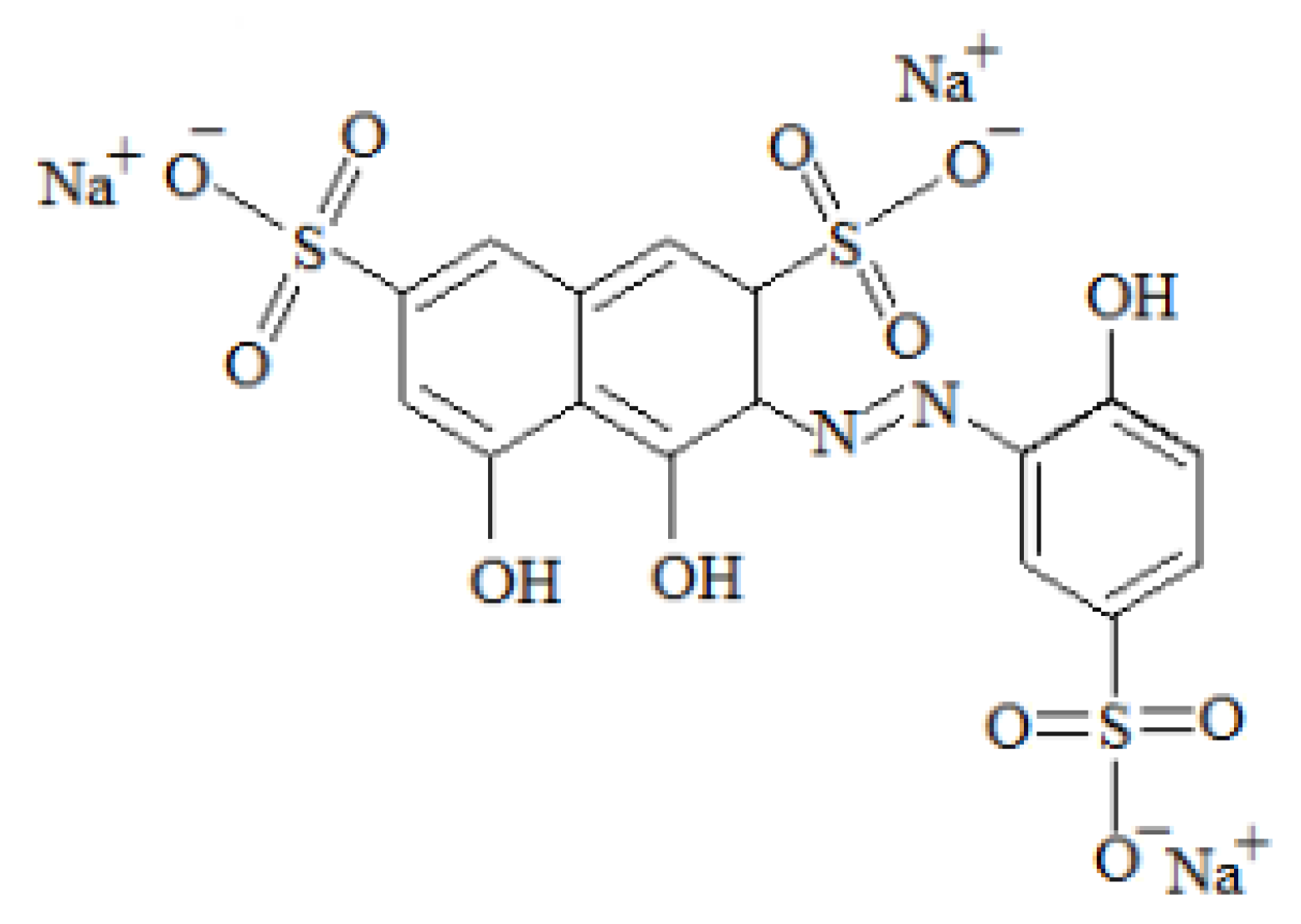

The acid dye selected for this investigation was C.I. Acid Blue 324, commercially known as Telon Blue M-2R, supplied by DyStar (Germany). This dye possesses a molecular weight of 766.53 g/mol and was used as received with a purification. The chemical structure of the dye is depicted in

Figure 1.

For pH control and adjustment of the dyebaths, analytical grade acetic acid (glacial, 99.8%) was used to prepare appropriate buffer solutions.

2.2. Dyeing Procedures

2.2.1. Conventional Dyeing Methodology

Conventional dyeing experiments were conducted in a laboratory-scale. The dyebath was prepared with a liquor ratio of 1:50. The dyeing process was initiated at a starting temperature of 30°C. The temperature was then uniformly raised to the target dyeing temperature (50, 60, 70, 80, or 95°C) at a controlled rate of 1

0C/min. The dyeing was maintained at the final temperature for a duration of target reaction time (5-10-15-20-25-30 minutes) for comparative kinetic studies. Upon completion of the dyeing duration, the fabric samples were immediately removed, thoroughly rinsed with cold deionized water to remove any unfixed surface dye, and subsequently air-dried. In addition, the effects of other reaction parameters such as pH (3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5, 6) and dye concentrations (0.1%, 0.25%, 0.5%, 0.75%, 1%, 1.5%) on dyeing were investigated [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48].

2.2.2. Microwave-Assisted Dyeing Methodology

Dyeing experiments were conducted using a modified microwave oven (Milestone Start D Microwave Digestion System). Dyeing baths were prepared in microwave-transparent 100 ml capacity tubes to ensure uniform microwave energy absorption.

The dyebath was prepared using the same liquor ratio (1:50) and dye concentrations as in the conventional dyeing protocol. The microwave power was systematically varied and set to 160 W. The dyeing duration was varied from 30 to 270 seconds, depending on the specific experimental conditions. The temperature of the dyebath was continuously and precisely monitored. Post-dyeing, the fabric samples were treated in the same manner as the conventionally dyed samples, involving a thorough rinsing and air-drying process [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48].

2.3. Analytical Procedures

2.3.2. Colorimetric Measurement

Dye uptake was determined by measuring the color strength in the fabric at predetermined time intervals using a Data Color SF 600 spectrophotometer at the maximum absorption wavelength of Telon Blue M2R (λmax = 630 nm). A calibration curve was established using known concentrations of the dye.

Color strength (K/S value) of the dyed fabric samples was measured using a reflectance spectrophotometer (Data Color 1000 spectrophotometer.) according to the Kubelka-Munk equation:

where R is the reflectance value at the maximum absorption wavelength [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Conventional Dyeing

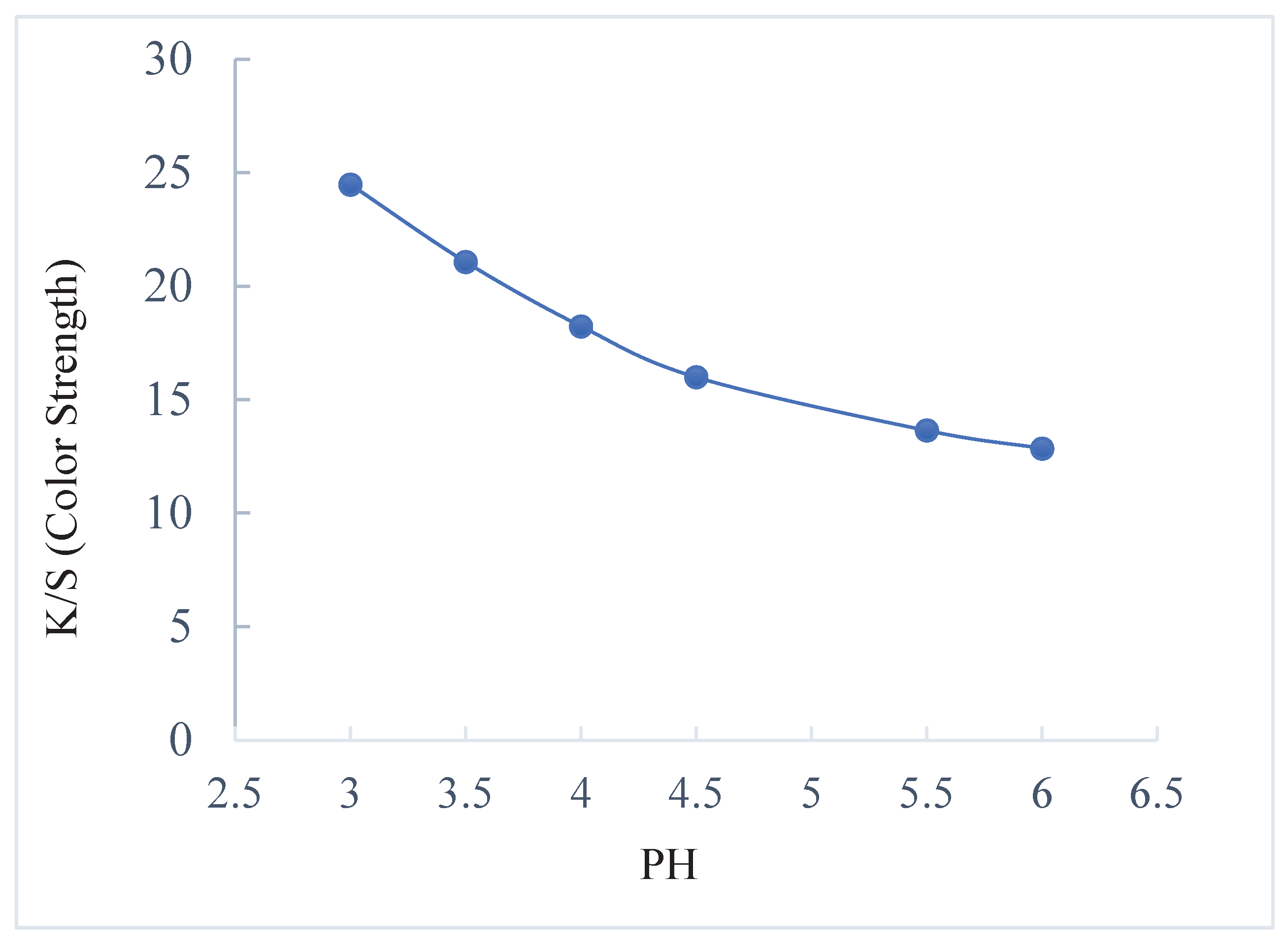

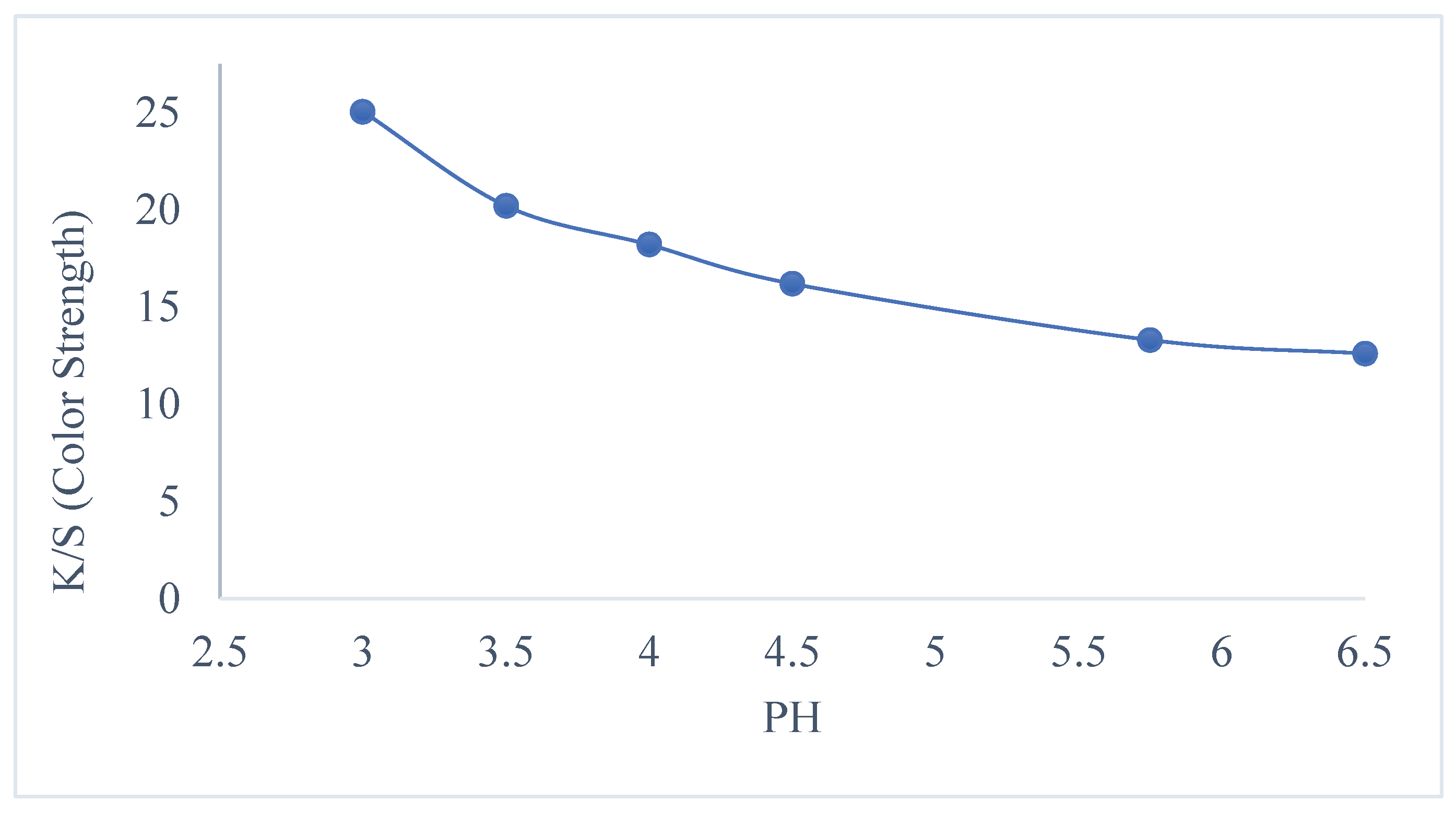

3.1.1. Effect of PH

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the initial pH of the dye bath and the resulting color strength (K/S) of the dyed material. The experiment was conducted under constant conditions of time (20 minutes) and temperature (80°C), with a dye concentration of 1% in conventional media. The results, presented in

Figure 2, clearly demonstrate a strong inverse correlation between the initial dye bath pH and the resulting K/S value.

The data in

Figure 2 shows that the highest color strength was achieved at the lowest initial pH of 3.0, while the lowest color strength was recorded at the highest initial pH of 6.0. This represents a significant decrease of approximately 47.5 % in color strength as the initial pH is increased from 3.0 to 6.0.

The plot of K/S versus pH exhibits a distinct negative exponential relationship. As the pH increases, the K/S value decreases sharply, particularly in the highly acidic range pH 3.0 to 4.0, before the rate of decrease moderates at higher pH values (above 4.5).

The data shows a progressive decrease in K/S as pH increases, with the steepest decline occurring between pH 3.0 and 4.0 (13.9% decrease per 0.5 pH unit). This indicates that the pH range 3.0–4.0 is critical for maximizing dye fixation on polyamide fibers.

3.1.2. Effect of Time andTemperature

The K/S value is a measure that indicates the color depth or dye uptake of a material The Kubelka-Munk function is widely used in color science to quantify the color yield of a dye on a substrate, where a higher K/S value indicates greater color depth or strength. [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

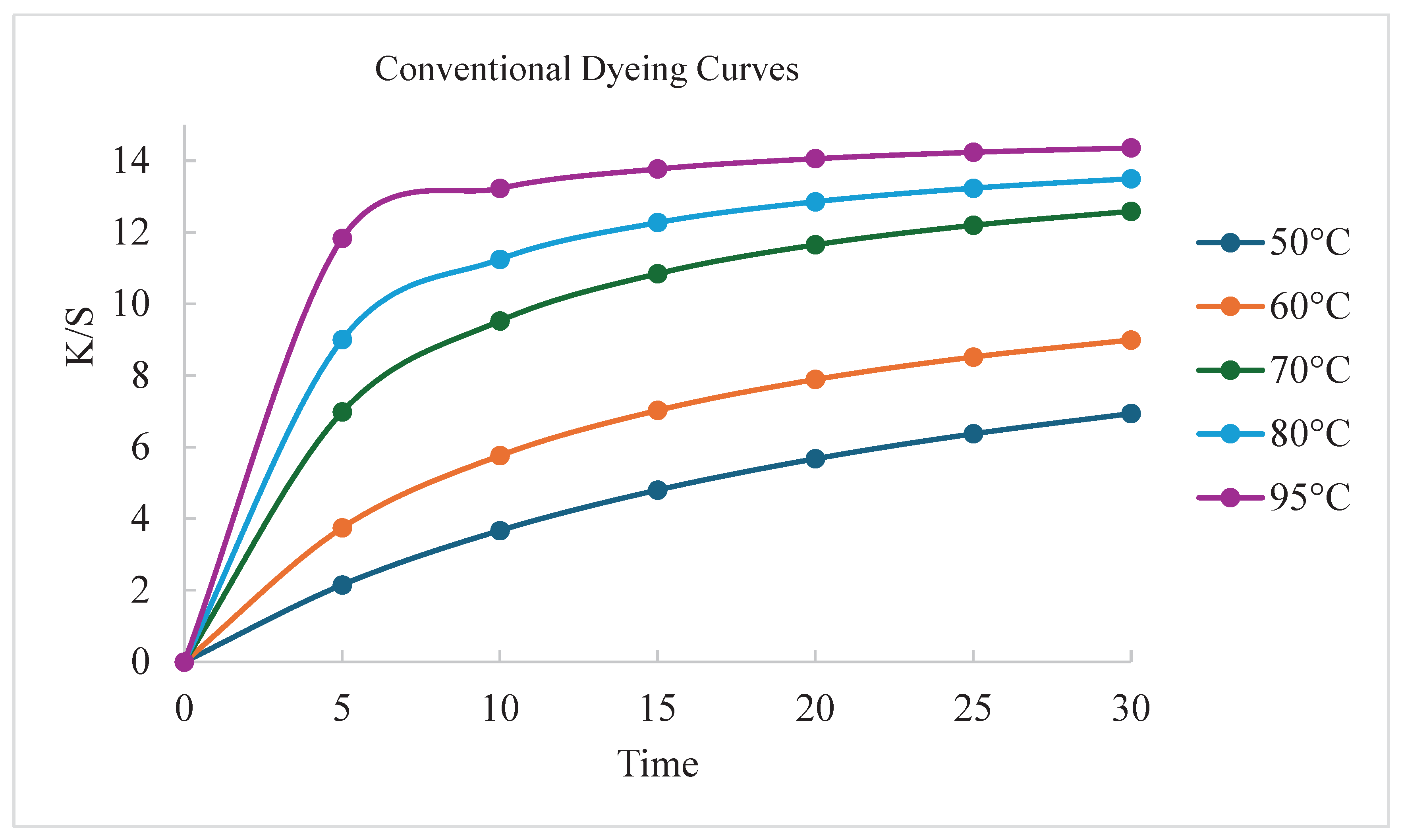

The analysis were conducted to understand the effects of the different dyeing times and the different temperatures at a pH 6-7 (without acid donor) and a dye concentration of 1 %. The dye samples at 1% concentration were heated to target temperatures (50°C, 60°C, 70°C, 80°C, and 95°C).

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the change in K/S values and Dye concentration over time (minutes) for five different temperatures. K/S values at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 minutes were measured for each temperature. Generally, K/S values show an increase over time at all temperatures. As the temperature increases, both the final level of K/S values and the rate of reaching saturation increase. Analysis of conventional dyeing curves clearly demonstrates that temperature and time play critical roles in K/S values and dyeing mechanism. At the highest temperature of 95°C, the fastest dye uptake and the highest final K/S values were obtained.

The rate of dye exhaustion is profoundly influenced by temperature. As the temperature increases from 50 °C to 95 °C, the initial rate of dye uptake increases significantly. More importantly, the time required to reach equilibrium is drastically reduced. For instance, the 95 °C curve shows a near-complete exhaustion (minimal change in concentration) within the first 10–15 minutes, whereas the 50 °C curve continues to show a measurable, albeit slow, decrease in concentration even after 30 minutes (

Figure 4).

3.1.3. Effect of Dye Concentration according to Different Temperatures

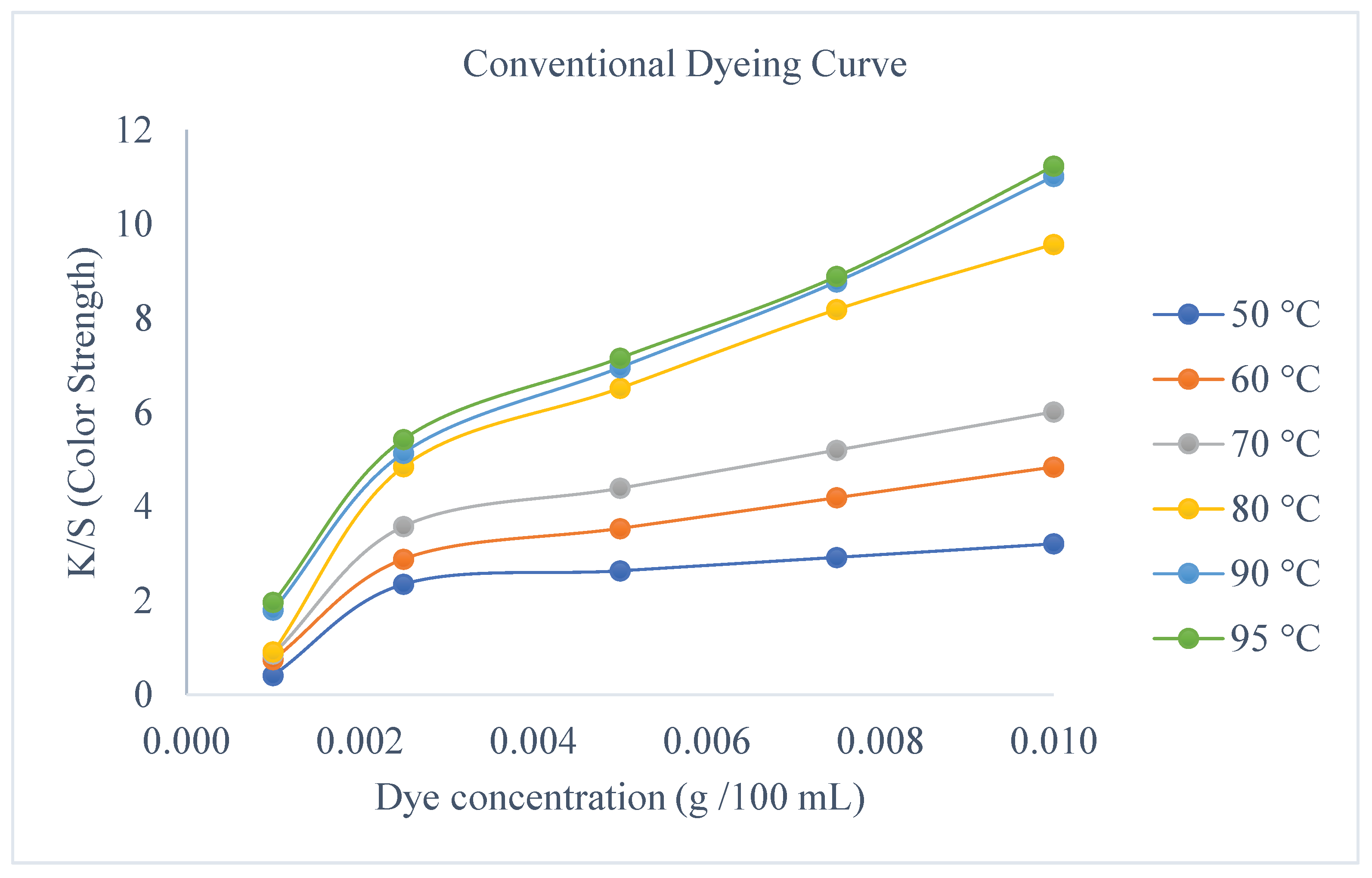

The dyeing process was initiated at a starting temperature of 30°C to examine the effects of dye concentration on the reaction. The temperature was then uniformly raised to the target dyeing temperature (50, 60, 70, 80, 90 or 95°C) at a controlled rate of 1°C/min. Experiments were proceeded in the pH 6-7 (without acid donor) and a reaction time of 10 minutes to investigate the effects of different dye concentrations and temperature.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between color strength, dye concentration, and dyeing temperature for a conventional dyeing process.

For any given dye concentration from

Figure 5, an increase in temperature from 50°C to 95°C results in a substantial increase in the K/S value. These data shows that the dyeing process has a critical temperature zone where the mechanism of dyeing are dramatically accelerated.

The K/S value under these conditions is approximately 3.5 times greater than the value achieved at the same concentration but at 50°C. This underscores the synergistic effect where a high dye concentration and high thermal energy (temperature) work in concert to maximize dye adsorption and fixation.

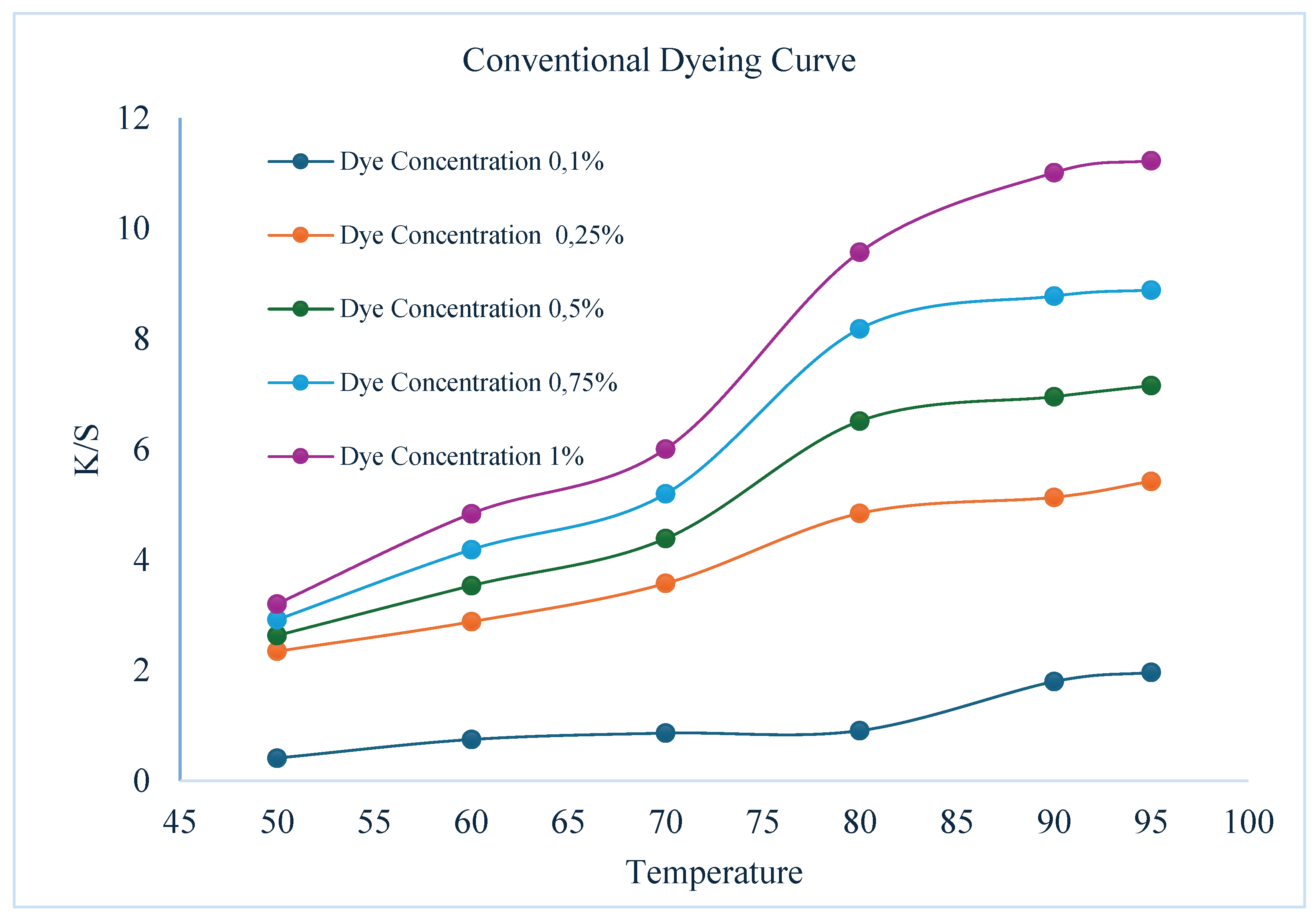

The Conventional Dyeing Curve presented in Fig. 6 illustrates the relationship between temperature and color strength (expressed as K/S values) for varying dye concentrations ranging from 0.1% to 1%.

At all temperatures, higher dye concentrations result in higher K/S values, confirming that color strength is concentration-dependent. However, the relationship is non-linear, especially at elevated temperatures:

At lower concentrations (0.1%), K/S values remain relatively low even at high temperatures, indicating limited availability of dye molecules.

At higher concentrations (0.75% and 1%), K/S increases sharply up to 80–90 °C, after which the rate of increase diminishes. This behavior suggests site saturation within the fiber, where additional dye molecules contribute less effectively to color strength.

Notably, the 1% dye concentration exhibits the highest K/S values across all temperatures, reaching a maximum of approximately 11.23 at 95 °C, confirming superior dye loading under these conditions.

As observed, K/S values increase with rising temperature across all dye concentrations, indicating enhanced dye uptake and fixation at elevated temperatures.

For all dye concentrations, an overall increase in K/S is observed as the temperature increases from 50 to 95 °C. This trend can be attributed to several temperature-dependent phenomena:

Increased molecular mobility of dye molecules, which enhances diffusion from the dye bath into the fiber structure. Fiber swelling at elevated temperatures, leading to greater accessibility of internal dye-binding sites. The most pronounced increase in K/S occurs between 70 and 80 °C, particularly for dye concentrations of 0.5%, 0.75%, and 1%, suggesting that this temperature range represents a critical transition where dye diffusion becomes significantly more efficient. Beyond 90 °C, the increase in K/S becomes marginal, indicating an approach to dye saturation or equilibrium uptake.

3.2. Microwave Dyeing

3.2.1. Effect of PH

Figure 7 shows the relationship between the initial pH of the dye bath and the resulting color strength (K/S) of the dyed material in microwave media. The experiment was conducted under constant conditions of time (4 minutes) and temperature (80°C), with a dye concentration of 1% in microwave media. The primary objective is to identify the optimal pH range for maximizing color yield in microwave media .

The results from

Figure 6 demonstrate a strong inverse correlation between the initial pH of the dye bath and the color strength. The highest K/S value was achieved at the most acidic condition tested pH 3.0 as in conventional media.

The K/S value decreases sharply from a maximum of approximately 25.0 at pH 3.0 to 12.5 at pH 6.5. This reduction of nearly 50% in color strength highlights the paramount importance of pH control in the dyeing of polyamide fibers, particularly when using acid or metal-complex dyes.

The high K/S values achieved (up to 25.0) are indicative of a highly efficient dyeing process, which is likely enhanced by the microwave environment.

•Accelerated Diffusion: Microwave heating provides rapid, volumetric heating, which can significantly increase the molecular mobility of the dye and the segmental motion of the polymer chains. This effectively lowers the energy barrier for the internal diffusion of the dye into the fiber matrix, accelerating the overall dyeing rate and allowing for a higher equilibrium dye uptake in a shorter time.

•Synergistic Effect: The microwave energy acts synergistically with the optimal chemical conditions (low pH). While the low pH provides the necessary thermodynamic driving force (electrostatic attraction), the microwave energy provides the kinetic acceleration (enhanced diffusion), resulting in the superior color strength observed.

Both conventional and microwave-assisted dyeing show a clear, inverse relationship between pH and color strength. The K/S value is maximized at the lowest tested pH (pH 3.0) and decreases sharply as the dyebath becomes less acidic. The optimal pH for maximum dye uptake remains consistently at pH 3.0 for both conventional and microwave-assisted dyeing. This indicates that the microwave energy does not alter the chemical equilibrium or the pKa of the functional groups on the fiber surface.

3.2.2. Effect of Time and Temperature

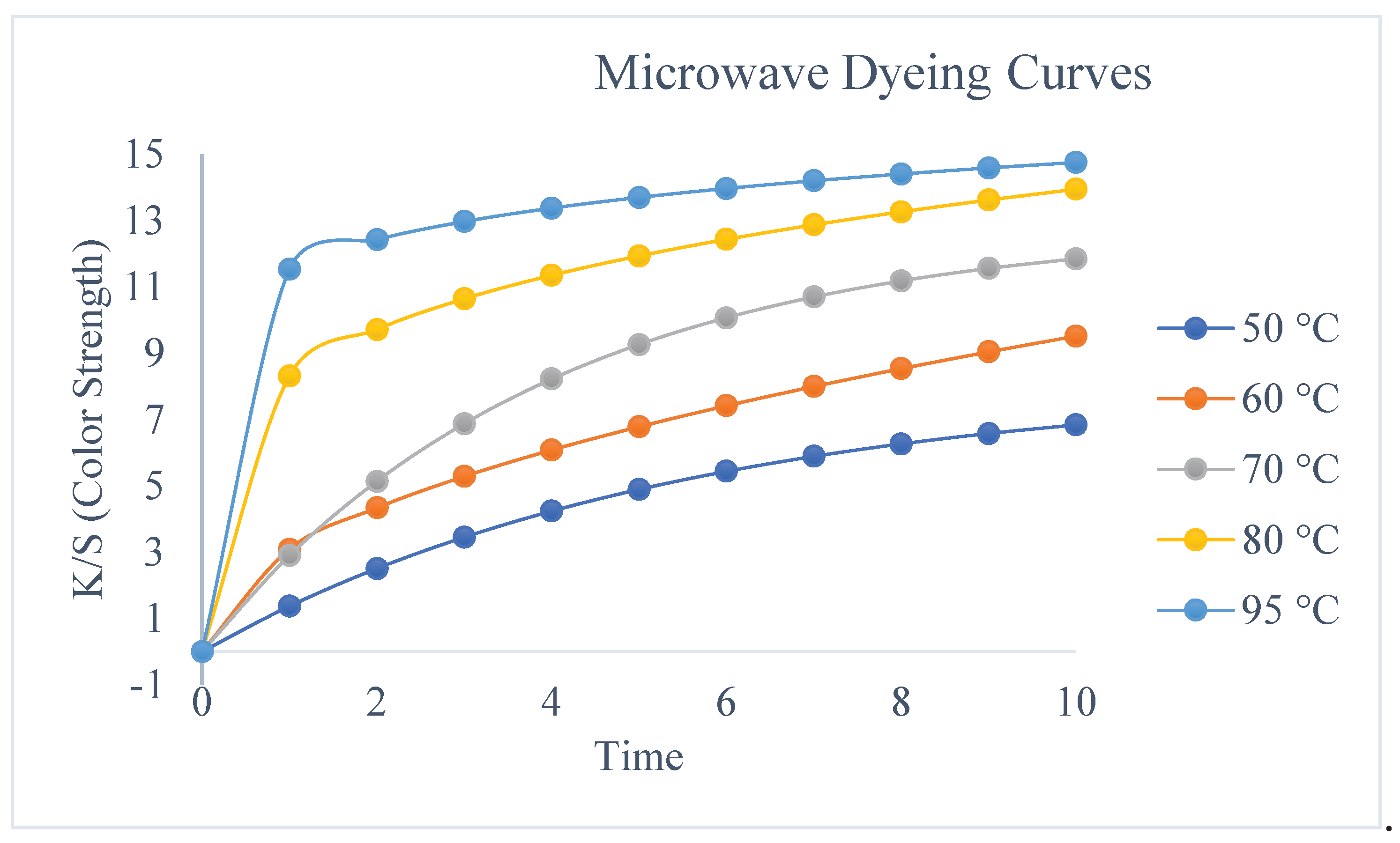

The analysis were conducted to understand the effects of the different dyeing times and the different temperatures at a pH 6-7 (without acid donor) and a dye concentration of 1 %

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 shows the effect of temperature (50– 95 °C) on the measured parameter over a 10 minute heating period. At all tested temperatures, the parameter increased continuously with time, indicating a temperature-dependent process. However, the rate of increase varied considerably with temperature.

Microwave-assisted dyeing is an advanced technique that utilizes electromagnetic radiation to rapidly heat the dye bath and the substrate, leading to faster diffusion and reduced processing times compared to conventional methods. The color strength, quantified by the Kubelka-Munk function (K/S), is a critical parameter for evaluating the efficiency of the dyeing process.

Temperature Dependence: For any given time point, the K/S value is directly proportional to the temperature. The 95 °C curve consistently yields the highest color strength, while the 50°C curve yields the lowest.

The initial rate of dyeing (the slope of the curve at t=0) is significantly higher at elevated temperatures, particularly at 80°C and 95°C. The 95 °C curve exhibits a near-vertical rise in the first minute, achieving a K/S of 11.530, which is approximately 8.2 times the value achieved at 50°C (K/S = 1.399) in the same period.

Equilibrium/Saturation: All curves exhibit a characteristic trend of rapid initial uptake followed by a gradual leveling off, suggesting that the dyeing process is approaching equilibrium exhaustion. The saturation point is reached fastest and at the highest K/S value for the 95 °C process.

Dye exhaustion, the percentage of dye transferred from the bath to the textile substrate, is a critical parameter in industrial dyeing, directly impacting color yield, process economics, and environmental sustainability. Monitoring the dye concentration in the bath over time is the standard method for determining the exhaustion rate. This analysis interprets the provided concentration data to quantify the effect of temperature on the rate and extent of dye uptake in a microwave-assisted system.

The data in

Figure 9 clearly demonstrate the exponential relationship between temperature and dye exhaustion. The analysis of the dye bath concentration data confirms the superior efficiency of high-temperature microwave-assisted dyeing. The process at 95°C achieves an exceptionally high dye exhaustion of 95.2% in just 10 minutes, which is indicative of a highly accelerated mass transfer process. This rapid and near-complete exhaustion is a direct result of the thermal energy provided by the microwave, which enhances the diffusion coefficient of the dye molecules and the swelling of the fiber structure. These findings underscore the potential of microwave technology for developing fast, high-yield, and environmentally conscious dyeing protocols.

The comparative analysis unequivocally demonstrates that microwave-assisted dyeing is kinetically superior to the conventional method. The microwave process significantly accelerates the rate of dye uptake, leading to substantially higher dye exhaustion in a fraction of the time required by the conventional method. This efficiency is particularly pronounced at 95 °C, where the microwave method achieves near-complete exhaustion 95.2% in just 10 minutes. The enhanced performance is attributed to the rapid, volumetric heating characteristic of microwave energy, which facilitates faster dye diffusion and fixation. These findings support the adoption of microwave technology as a more time-efficient and environmentally favorable alternative for industrial dyeing applications.

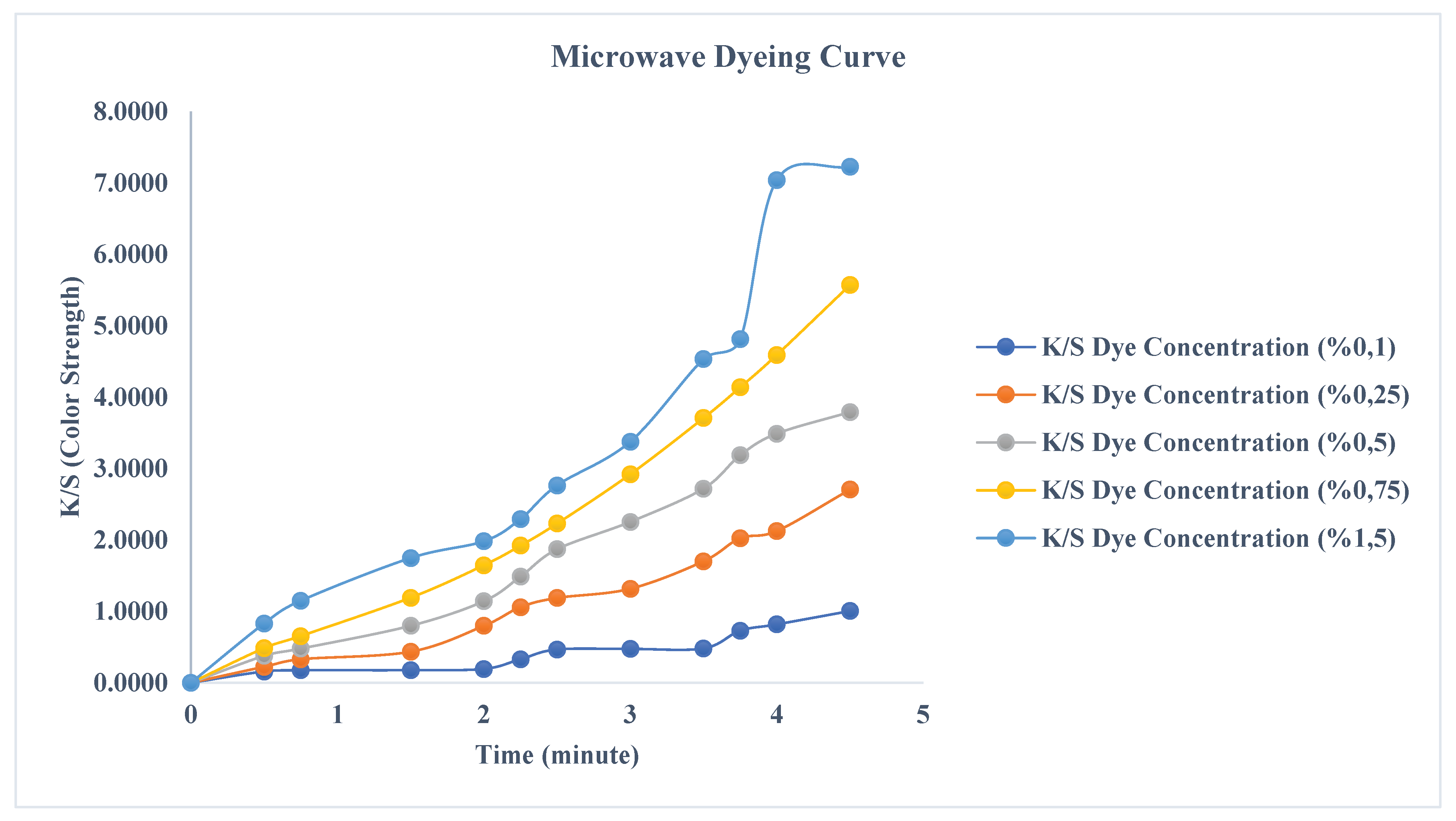

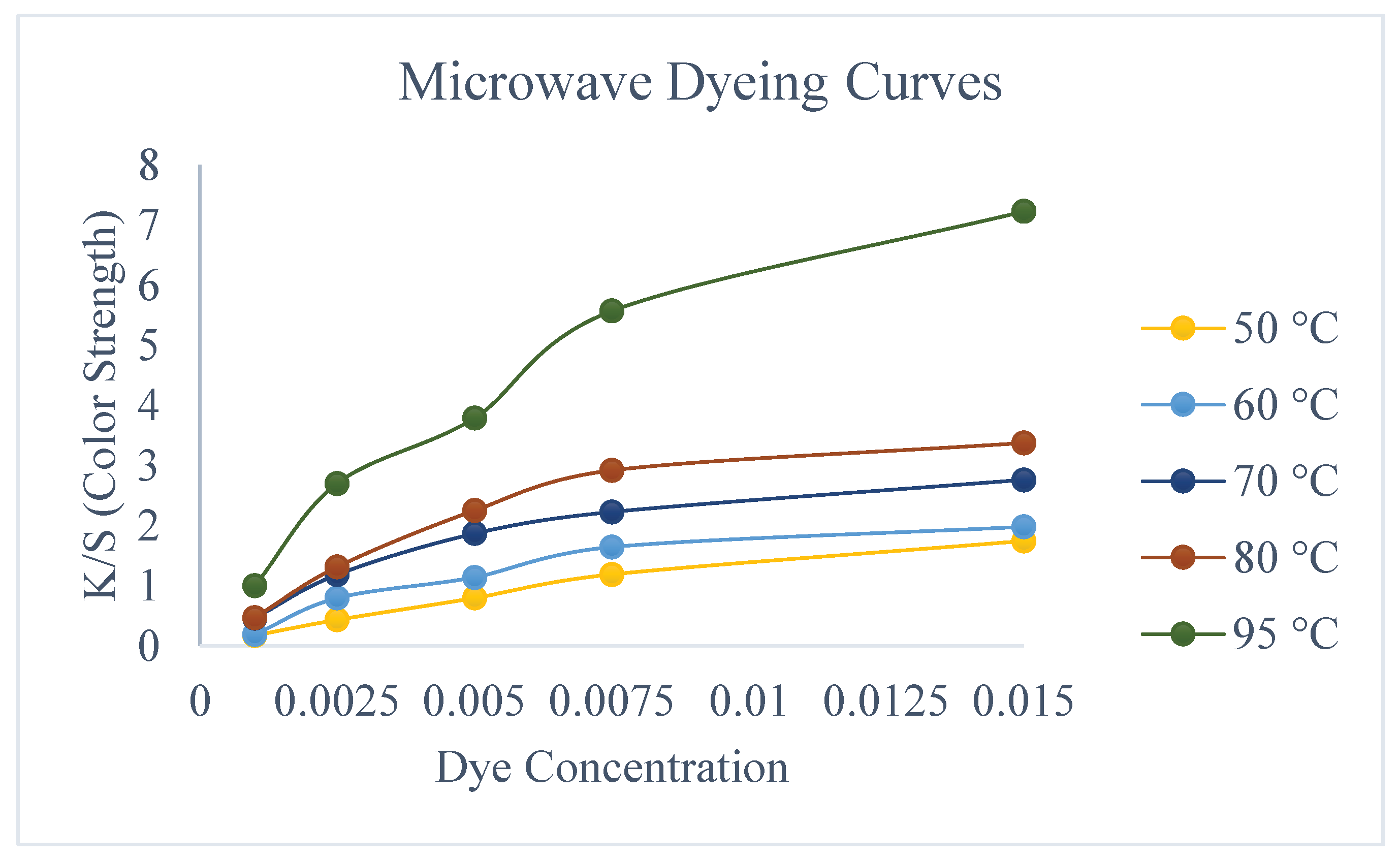

3.2.3. Effect of Dye Concentration according to Different Temperatures

The analysis were conducted to understand the effects of the different dyeing times and the different concentrations at a pH 6-7 (without acid donor).

Figure 9.

Effect of Dye Concentration at Different Reaction Times (Microwave Heating).

Figure 9.

Effect of Dye Concentration at Different Reaction Times (Microwave Heating).

Figure 10.

Effect of Reaction Time at Different Concentrations (Microwave Heating).

Figure 10.

Effect of Reaction Time at Different Concentrations (Microwave Heating).

The figures illustrate the relationship between dye concentration (% mg/100 ml) and color strength (K/S) for samples treated under microwave irradiation at different dyeing times (0–4.5 minutes).

Overall, the results demonstrate that both dye concentration and microwave dyeing time have a significant positive effect on color strength. For all microwave exposure times, the K/S values increase with increasing dye concentration. This trend indicates that higher dye availability in the dye bath leads to greater dye uptake by the material, resulting in enhanced color strength. However, the increase is non-linear, suggesting a gradual approach toward saturation at higher concentrations.

At a fixed dye concentration, increasing the microwave treatment time markedly increases the K/S values. Short dyeing times (0–1.5 minutes) result in relatively low color strength, while longer times (3–4.5 minutes) produce substantially higher K/S values. This behavior can be attributed to the enhanced molecular mobility and diffusion of dye molecules under microwave heating, which promotes more efficient dye–fiber interactions.

The highest color strength is observed at the combined condition of high dye concentration and prolonged microwave exposure (4–4.5 minutes). This indicates a synergistic effect, where microwave energy accelerates dye penetration and fixation, particularly at higher dye concentrations.

The data suggest that microwave-assisted dyeing is an effective method for achieving high color strength in relatively short processing times. Optimizing microwave exposure time can reduce energy consumption while maintaining or enhancing dyeing efficiency.

The results in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 clearly demonstrate that both

dye concentration and

microwave exposure time have a pronounced effect on dye uptake. For all dye concentrations studied (0.1–1.5%), the K/S values increase monotonically with dyeing time, indicating progressive adsorption and fixation of dye molecules onto the substrate. A

rapid increase in K/S is observed at the early stages (0–2.5 min), followed by a more gradual rise at longer times.

At any given dyeing time, K/S values increase systematically with increasing dye concentration:

This trend confirms that higher initial dye concentrations provide a greater driving force for mass transfer, leading to enhanced dye uptake. The effect is particularly pronounced under microwave conditions, where volumetric heating promotes:

At higher concentrations (≥0.75%), the K/S values increase sharply after 3 minutes, suggesting that microwave irradiation effectively overcomes diffusion limitations that are typically observed in conventional dyeing processes.

3.2.4. Role of Microwave Irradiation

Compared to conventional thermal dyeing reported in the literature, the observed dye uptake occurs within remarkably short dyeing times (≤4.5 min). This enhancement can be attributed to the specific effects of microwave irradiation, including:

Rapid and uniform heating of the dye bath and substrate

Dipole rotation and ionic conduction effects

Reduced thermal gradients within the fiber matrix

These factors collectively accelerate dye–fiber interactions and improve fixation efficiency. The experimental results demonstrate that microwave-assisted dyeing enables:

Such characteristics make microwave-assisted dyeing a promising approach for energy-efficient and time-saving textile coloration processes.

4. Conclusions

Comprehensive comparative kinetic study was conducted on the acid dyeing of PA-6 fabric, systematically evaluating the performance of conventional heating against the innovative microwave-assisted technique using C.I. Acid Blue 324. This investigated the mechanism of acid dyeing of Polyamide 6 (PA6) fabrics, providing a detailed comparison between microwave-assisted heating and conventional dyeing methodologies. The investigation analyzed the influence of key parameters pH, temperature, dyeing time, and dye concentration on the resulting color strength (K/S) and the underlying kinetic mechanisms.

The study confirmed that the conventional dyeing process adheres to established principles, with the highest dye uptake achieved at the most acidic condition (pH 3.0) and the highest temperature tested (95°C). However, the process is inherently time consuming, requiring a duration of 30 minutes to achieve maximum color yield, which is a significant factor in industrial throughput and energy consumption.

The findings clearly demonstrate that the microwave-assisted method provides a robust scientific basis for developing faster, more energy-efficient, and more sustainable dyeing protocols in the textile industry.

Key Findings are as below.

Effect of pH: In both dyeing methods, the optimum pH value for maximum dye uptake (K/S value) was determined to be 3.0. This confirms the critical importance of an acidic environment to maximize the ionic interaction between the protonated amino groups in the PA6 fiber and the dye molecules.

Conventional Dyeing: In the conventional method, dye uptake increased proportionally with time and temperature, with the highest K/S values obtained after 30 minutes of dyeing at 95°C. This indicates that the rate-determining step of dye diffusion and fixation is dependent on thermal energy.

Microwave-Assisted Dyeing: The microwave-assisted dyeing method provided a remarkable acceleration in the dyeing time. Thanks to the dielectric heating mechanism (160 W), the time required for dye uptake was drastically reduced compared to the conventional method (seconds instead of minutes).

Mechanistic Explanation: Kinetic analyses proved that the internal, volumetric heating mechanism of microwave energy accelerates the rate-determining step of dye diffusion. This is attributed to the microwave's ability to more effectively increase the molecular mobility of the dye and the swelling of the PA6 fiber structure compared to conventional external heating.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nurel Tekstil, Bursa, Turkey, for kindly supplying the polyamide fabrics and allowing the supports.

References

- Böcek, Nevin (2001), Investigation of Fiber and Temperature Interaction in Dyeing of Synthetic Fibers, [Master's thesis, Sakarya University]. YÖK National Thesis Center. https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/.

- K. Haggag, M. M. El-Molla, K. A. Ahmed (2015), Dyeing of Nylon 66 Fabrics Using Disperse Dyes by Microwave Irradiation Technology, International Research Journal of Pure & Applied Chemistry, 8(2): 103-111, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Ghazal, "Microwave irradiation as a new novel dyeing of polyamide 6 fabrics by reactive dyes," Egypt. J. Chem., vol. 63, no. 6, pp. 2125-2132, 2020.

- Nikodijevic, M., Vuckovic, N., Dordevic, D., Possibilities of Dyeing of Polyamide Fabric with Substantive Dye, The Eurasia Proceedings of Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics (EPSTEM), 2020, Volume 11, Pages 131-135.

- Özcan Y., Textile Fiber and Dyeing Technique, 1978.

- Alegbe, E. O., & Uthman, T. O. (2024). A review of history, properties, classification, applications and challenges of natural and synthetic dyes. Heliyon, 10, e33646. [CrossRef]

- Usluoğlu A., Teker M. (2024), Investigation of Dyeing Kinetics of Cotton Fiber with C.I. Reactive Yellow 138:1 Dyestuff in Microwave Environment- Journal of the Institute of Science of Yüzüncü Yıl University - Vol.29 -pp.119 - ISSN : 1300-5413. [CrossRef]

- Yiğit E.A., Teker M. (2011), Disperse Dyeability of Polypropylene Fibers via Microwave and Ultrasonic Energy - Polymer and Polymer Composites - Vol.19 - pp.711 - ISSN : 1478-2391. [CrossRef]

- Haggag K., El-Molla M.M., Mahmoued, Z.M., Dyeing of Cotton Fabric using Reactive Dyes by Microwave Irradiation Technique, Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research Vol.9, December 2014, pp. 406-410.

- Rahman, M. M., Ahmed, M., Jalil, M. A., & Mondal, M. I. H. (2008). The effect of microwave preheating on the dyeing of wool fabric with a reactive dye. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 108(1), 314–318. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Liu, J., Wang, J., Wang, J., & Meng, J. (2009). A novel process of dyeing wool with acid dyes under microwave irradiation. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 113(5), 2798–2803. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. S., Leem, S. G., Ghim, H. D., Kim, J. H., & Lyoo, W. S. (2003). Microwave heat dyeing of polyester fabric. Fibers and Polymers, 4(4), 204–209. [CrossRef]

- Kocak D., Akalin M., Merdan N., Yilmaz Sahinbaskan B, Effect of Microwave Energy on Disperse Dyeability of Polypropylene Fibres, Marmara Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2015, Special Issue-1: 27-31.

- Haggag, K., Hanna, H. L., Youssef, B. M., & El-Shimy, N. S. (1995). Dyeing polyester with microwave heating using disperse dyestuffs. Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists, 111(5), 170-173. [CrossRef]

- Büyükakıncı Y. B., Karada R., Guzel, E.T., Organic cotton fabric dyed with dyer's oak and barberry dye by microwave irradiation and conventional methods, Industria Textila, Vol No, 72, 30-38, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gouda M., Haggag K. M.,. Boraie W. E, Aljaafari A., Al-Faiyz Y. , Synthesis and Characterization of Inorganic Pigment Nanoparticles for Textile Coloration Using Microwave Techniques, AATCC Journal of ResearchVolume 3, Issue 3, May 2016, Pages 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Kale, M.J., Bhat, N.V., Effect of microwave pretreatment on the dyeing behaviour of polyester fabric, Society of Dyers and Colourists, Color. Technol., 127, 365–371. [CrossRef]

- Popescu V., Astanei D.G., Burlica R. , Popescu A., Munteanu C., Ciolacu F., Ursache M. , Ciobanu L., Cocean A. Sustainable and cleaner microwave-assisted dyeing process for obtaining eco-friendly and fluorescent acrylic knitted fabrics, Journal of Cleaner Production Volume 232, 20 September 2019, Pages 451-461 . [CrossRef]

- Keglevich G., The Application of Microwaves in the Esterification of P-Acids, Current Microwave Chemistry, 2022, 9, 62-64;

- Ghaffar A., Adeel S. , Habib N. , Jalal. F. , Ul-Haq A. , Munir B. , Ahmad A. , Jahangeer M. , Jamil Q., Effects of Microwave Radiation on Cotton Dyeing with Reactive Blue 21 Dye, Pol. J. Environ. Stud. Vol. 28, No. 3 (2019), 1687-1691. [CrossRef]

- Al-Etaibi A.M., El-Apasery M.A, Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Azo Disperse Dyes for Dyeing Polyester Fabrics: Our Contributions over the Past Decade, Polymers 2022, 14, 1703. [CrossRef]

- Elshemy N.S., Haggag, K., New Trend in Textile Coloration Using Microwave Irradiation, J. Text. Color. Polym. Sci., Vol. 16, No.1, pp 33-48(2019). [CrossRef]

- Öner, E., Büyükakıncı, Y., & Sökmen, N. (2013). Microwave-assisted dyeing of poly(butylene terephthalate) fabrics with disperse dyes. Coloration Technology, 129(2), 125–130. [CrossRef]

- Büyükakıncı, Y., Sökmen, N. and Öner, E., Microwave assisted exhaust dyeing of polypropylene. In: Paper presented at the 4th Centrel European Conference, Liberec, Czech Republic, 7-9 September 2005.

- Haggag K., Fixation of pad-dyeing on cotton using microwave heating. Am Dyestuff Rep1990; pp. 26-30.

- Lill J. R., Microwave-Assisted Proteomics, 2009.

- Hayes B. L., Microwave Synthesis, 2002.

- Can M. C., Microwave Heating as a Tool for Sustainable Chemistry, 2010.

- Yiğit Atabek, E. (2009). Investigation of Dyeability of Polypropylene Fiber [Doctoral thesis, Sakarya University]. YÖK National Thesis Center. https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/.

- Doyuran A. (2010). Dyeing of Synthetic Fibers in Microwave Environment [Master's thesis, Sakarya University]. YÖK National Thesis Center. https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/.

- A. Miklavc, Chem. Phys.Chem, 2001, 552.

- Binner J.G.P., Hassine N. A. and Cross T. E., J. Mater. Sci., 1995, 30, 5389.56.

- Garbacia S., Desai B., O. Lavaster and C. O. Kappe, J. Org. Chem., 2003, 68, 9136.

- A. Stadler and C. O. Kappe, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 2000, 2, 1363.

- Hoz, A. Diaz-Ortiz and A. Moreno, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2005, 34, 164.

- Xiaolei Z., Jinwei M., Yanxiu W., Tianjie N., Deshuai S., Long F., Xiaodong Z., Investigation on dyeing mechanism of modified cotton fiber, Royal Society of Chemistry, Volume 12, Issue 49, 3 November 2022, Pages 31596-31607. [CrossRef]

- Trotman E.R., Dyeing and Chemical Technology of Textile Fibres, 1970.

- Mortimer M., Taylor, P., Chemical Kinetics and Mechanism, 2002.

- House J. E., Principles of Chemical Kinetics, 2007.

- Balluffi, R.B., Allen, S.M., Carter, W.C., Kinetics of Materials, 2005.

- Barrante, J.R., Applied Mathematics for Physical Chemistry, 1998.

- Vassileva V., Zheleva Z., Valcheva E., The Kinetic Model of Dye Fixation on Cotton Fibers, Journal of University of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy, 43, 3, 2008, 323-326.

- Teker, M; Imamoglu, M; Bocek, N. (2009) - Adsorption of Some Textile Dyes on Activated Carbon Prepared From Rice Hulls - Fresenıus Environmental Bulletin - Vol.18 - pp.709 - ISSN : 1018-4619 - English - Article - 2009 - WOS:000266898500009. [CrossRef]

- Ujhelyiova A., Bolhova E., Oravkinova J., Tin R., Marcin A., Kinetics of dyeing process of blend polypropylene/polyester fibres with disperse dye, Dyes and Pigments 72 (2007) 212-216. [CrossRef]

- Roy MN, Hossain MT, Hasan MZ, Islam K, Rokonuzzaman M, Islam MA, Khandaker S, Bashar MM. Adsorption, Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Reactive Dyes on Chitosan Treated Cotton Fabric. Textile & Leather Review. 2023; 6:211-232. [CrossRef]

- Lis M.J., Bezerra F.M., Meng X., Qian H., . Immich A.P.S, Kinetics of Dyeing in Continuous Circulation with Direct Dyes:Tencel Case; World Journal of Textile Engineering and Technology, 2019, 5, 97-104.

- Elshemy N. S., Elshakankery M. H., Shahien S. M., Haggag, El-Sayed K. H., Kinetic Investigations on Dyeing of Different Polyester Fabrics Using Microwave Irradiation, Egypt. J. Chem. The 8th. Int. Conf. Text. Res. Div., Nat. Res. Centre, Cairo (2017) pp. 79 - 88 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Ujhelyiova A., Bolhova, E., Oravkinova J., Tiňo R. and Marcinčin A., Kinetics of dyeing process of blend polypropylene/polyester fibres with disperse dye, Dyes and Pigments, vol. 72(2), 2007, pp. 212-216. [CrossRef]

- Alşan, H. G. (2019), Investigation of Dyeing Kinetics of Cotton Fiber with Disperse Dyestuff in Microwave Environment [Master's thesis, Sakarya University]. YÖK National Thesis Center. https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).