1. Introduction

In recent years, Portugal has faced a worsening housing crisis, particularly acute in urban centers such as Lisbon, where growing demand for housing coexists with the paradox of tens of thousands of homes remaining unoccupied. Although public and political attention has focused on increasing the supply of housing and regulating tenant protection, relatively little research has been done to understand the motivations of those who control this hidden stock as private owners.

This article addresses a central but still under-explored issue related to the reasons why many landlords choose not to put their vacant properties on the rental market, despite a clear social and economic need. Rather than viewing landlords as obstacles to housing reform, this research seeks to understand their choices through a more empathetic and systemic lens. This study suggests that for solutions to be more effective in combating the housing crisis, they must include a deeper understanding of landlords' behaviour, shaped by legal, financial, and cultural logics.

In this context, Portugal offers a particularly interesting case. A combination of historical rent freezes, changes in legislation, and unstable tax incentives has produced a disproportionately elderly class of landlords who are risk-averse and deeply distrustful of the state. These traits are very visible in Lisbon, where more than 40% are small landlords over the age of 65, many of whom inherited their properties rather than acquiring them through active investment.

Based on a review of international literature and empirical data from several editions of the Landlords' Confidence Barometer, conducted by the Lisbon Landlords Association (ALP), this study explores the multiple reasons behind landlords' reluctance to rent out their properties. We argue that this resistance is not irrational or simply speculative. It is rooted in a broader crisis of confidence, both in the state and in the rental market itself. Without taking this lack of confidence into account, housing policies (however well designed they may be) risk failing to activate a significant portion of the underutilised housing stock.

The article is organized as follows. First, we present the theoretical foundations that frame landlords' behaviour, drawing on concepts such as the financialization of housing, institutional trust, and patrimonial logic. Next, we analyse data from the ALP barometer in the context of Lisbon, mapping the main fears, profiles, and decisions of local landlords. Finally, we discuss the implications for policymaking, advocating trust-based approaches that view landlords as potential partners rather than adversaries in the struggle for access to housing.

2. Methodology

2.1 Research Design

A qualitative case study design was adopted, focusing on the Lisbon region as a critical location for examining landlord behaviour and urban vacancy. Lisbon was selected not only for its concentration of rental housing and visible housing pressures, but also because it has been the site of experimentation with rent regulation and housing taxation policies since 2012. As such, it offers a paradigmatic example of how national reforms materialise in a specific urban context.

The research follows a critical case study logic (Flyvbjerg, 2006), which means that Lisbon serves as a revealing example because if landlords here, where rental demand is strongest, continue to flee the market, it is likely that similar dynamics exist elsewhere in Portugal. The aim is analytical generalisation rather than statistical inference, identifying mechanisms and rationales that can shed light on broader urban and political processes.

2.2 Data Sources

The empirical work integrates three complementary strands:

1. Survey data from all editions of the ALP Landlord Confidence Barometer (2020–2025), which provides a rare longitudinal dataset capturing the evolution of landlords’ perceptions and actions.

2. Policy and legislative materials, including housing programmes, tax reforms, and official communications from the Portuguese government between 2010 and 2025.

3. Secondary and documentary sources, such as academic analyses, press articles, and reports from housing associations and think tanks.

This combination allows for a triangulated reading of the relationship between perception, policy, and structural context, linking quantitative indicators of confidence to qualitative interpretations of political discourse.

2.3 Analytical Strategy

The study applied an interpretative analytical framework that combines content analysis and thematic coding. Each series of ALP data was coded for recurring categories (trust, regulation, risk, rent payment delays, and involvement with public programmes), facilitating diachronic comparison. The findings were then cross-referenced with key policy changes (e.g., the 2023 Mais Habitação package) to trace causal associations between regulation and perception.

The analysis proceeds in three stages:

Descriptive synthesis, identifying longitudinal patterns in confidence, arrears, and participation rates.

Interpretive correlation, exploring how these trends reflect underlying logics of patrimonial protection and institutional distrust.

Contextual embedding, relating Lisbon’s patterns to wider debates on housing financialization and state-citizen relations.

This approach favours mechanisms over metrics, since instead of testing hypotheses, it reconstructs the meanings and rationales that inform owners' behaviour. The method thus bridges quantitative regularities and qualitative explanations, allowing the study to address both housing policy and broader sociological understandings of trust and governance.

2.4 Reflexivity and Limitations

Although the ALP Barometer offers a rich longitudinal perspective, its sample represents self-selected respondents, mostly small and medium-sized owners active in the association's network. The results therefore capture perceptions and rationalities rather than the complete statistical universe of Portuguese owners. However, the consistency of responses over five years increases their analytical validity.

Finally, the interpretative stance of this study acknowledges the researcher's position, as the aim is not to judge between landlords and policy makers, but to reveal the logic of defensive rationality that structures their relationship. This reflective approach allows the study to go beyond moral or ideological frameworks and move towards an understanding of housing governance as a relational system dependent on trust.

3. Theoretical Framework

Understanding why property owners keep residential properties vacant requires an interdisciplinary lens. Economic rationality alone cannot fully explain such decisions in contexts of high demand and rising prices. This research draws on three main theoretical pillars to interpret the reluctance of owners: housing financialization, institutional trust and regulatory risk, and sociocultural-patrimonial logics of ownership. Together, these frameworks allow for a nuanced understanding of vacancy as both a market behaviour and a social practice.

3.1 Housing Financialization: The Home as an Asset Class

The notion of housing as a financial asset rather than a social good lies at the core of recent transformations in urban housing markets. This process, commonly referred to as housing financialization, entails the progressive detachment of housing from its use value (i.e., shelter and domestic stability) and its rearticulation as an investment vehicle, asset reserve, or speculative commodity within national and global circuits of capital accumulation (Fuller, 2019; Wu et al., 2020).

This reconceptualization has profound consequences for owner behaviour in contexts of housing scarcity. In financialized urban environments, properties are not necessarily bought or maintained for habitation or rental income. Rather, they are held as capital appreciation instruments, assets whose primary function is to store and increase wealth over time. This logic supports the strategic retention of properties, even when demand is high, because realized or expected gains from future resale often outweigh the relatively modest and bureaucratically entangled returns of traditional renting (Byrne, 2019; Clauretie & Wolverton, 2006).

In Lisbon, this shift is particularly evident in the city’s historic centre and tourist-favoured zones, where domestic and international investors, as well as private owners, have increasingly adopted speculative practices. The expectation of rising property values, due to urban regeneration, gentrification, and tourism dynamics, fuels a form of passive speculation, where properties are deliberately kept vacant to avoid degradation, tenant risk, or regulatory constraints, while capitalizing on medium-to-long-term appreciation (Domínguez, 2019).

Moreover, housing financialization is not confined to individual owner behaviour but is structurally embedded in contemporary financial markets through vehicles such as REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts), investment funds, and institutional ownership models that displace the function of housing from dwelling to yield extraction (August, 2020; Sanfelici & Halbert, 2019). While Portugal’s institutional investment market remains comparatively modest, the behavioural logics of financialization, including “asset hoarding”, short-term leasing conversion, and speculative vacancy, have permeated even among small-scale, patrimonialist landlords, as evidenced by Lisbon’s high vacancy concentrations in strategic urban zones.

A particularly relevant feature of this model is what some scholars have termed “rational vacancy” as the deliberate withholding of property from the market as a wealth preservation strategy. This logic is bolstered in low-interest environments where alternative savings mechanisms yield little return, rendering real estate the preferred vehicle for capital storage, particularly among middle and upper-middle-class owners without sophisticated financial portfolios (Cruces, 2016). In these contexts, vacancy is not a symptom of inefficiency but an intentional asset management strategy.

Furthermore, the temporal logic of financialization, privileging future value over present use, fosters behaviors that run directly counter to housing justice objectives. The prospect of tighter rent controls, burdensome tenant rights, or economic instability can all act as triggers for withdrawal, incentivizing owners to “sit on” properties rather than rent them under perceived suboptimal conditions. This behavior has been observed not only in Lisbon but also in other Mediterranean cities where legal fragility, tourism-induced gentrification, and patrimonial real estate cultures intersect (Rehm & Yang, 2020; Vrantsis, 2025).

According to the joint report by INE-LNEC (2023), Portugal had approximately 723,000 vacant dwellings in 2021, representing around 12% of the national housing stock. However, almost half of these are vacant for functional rather than structural reasons, seasonal homes, properties in transition or units unsuitable for occupation. This distinction highlights that the apparent housing surplus can coexist with a real shortage of affordable and adequate housing.

Furthermore, recent data from the Institute for Housing and Urban Rehabilitation (IHRU, 2023) show that, despite the growing political emphasis on rental housing, the proportion of households living in rented housing in Portugal fell from 25% in 2011 to 22% in 2021, while rents rose sharply. This highlights the structural rigidity on the supply side, namely the persistence of vacant or underused housing and the limited response of the private rental market to demand.

Data from INE and LNEC (2023) confirm that the highest concentrations of vacant housing are located in rural or depopulated municipalities, while demand for housing, especially for rent, is concentrated in metropolitan areas. This spatial imbalance reinforces the structural nature of the housing shortage in Portugal.

In short, this picture allows us to interpret the withdrawal of landlords from the rental markets not as a deviation or irrationality, but as a rational expression of asset maximisation in conditions of uncertainty. In doing so, it challenges the assumption that increasing rents will necessarily free up the housing stock, highlighting the limitations of purely market-based solutions to the housing crisis.

3.2 Institutional Trust and Regulatory Uncertainty

A second key dimension in understanding why property owners withhold housing from the rental market is the role of institutional trust or more precisely, the lack thereof. Institutional trust refers to the confidence that individuals or groups place in the rules, norms, and actors responsible for governing economic and social life. In the housing sector, this trust is particularly relevant in relation to the stability, clarity, and fairness of rental regulation, taxation, and judicial enforcement.

When trust in these institutions is low, property owners often perceive the rental market as a site of legal and financial exposure. Rather than viewing the state as a reliable guarantor of property rights and contractual enforcement, landlords may see it as a source of uncertainty and volatility, subject to populist pressures, ideological shifts, or bureaucratic inefficiencies. This perception leads to avoidance behavior. Opting out of formal leasing channels, refusing engagement with public housing programs, or exiting the market altogether.

The Portuguese Case: A Landscape of Legal Volatility

Portugal exemplifies a context in which regulatory volatility has significantly undermined landlords’ trust in the rental system. Over the past two decades, the country has seen repeated shifts in rental legislation, from attempts at liberalization in the early 2010s to a reassertion of strong tenant protections in the wake of social mobilizations and housing crises. These policy reversals have included:

The reimposition of rent controls (“rendas congeladas”),

The extension of tenant protections during COVID-19,

The very controversial “Mais Habitação” package,

And proposals for forced leasing of vacant properties (arrendamento coercivo).

Each of these shifts has contributed to a perception among property owners that the rules of the game are unstable and subject to change with little notice or due process.

According to the ALP Barometers:

A vast majority of landlords (85%) stated that the announcement of the Mais Habitação reforms negatively impacted their confidence in the market.

96% declared unwillingness to rent their properties to the State under any scheme.

92.7% stated they would pursue legal action if their property were subject to forced rental measures.

Only 2% of surveyed landlords entered affordable rent programs despite financial incentives.

These numbers do not merely reflect dissatisfaction with specific policies but point to a systemic breakdown in trust between landlords and the state.

Trust as a Precondition for Market Participation

In behavioral economics and institutional theory, trust is not an incidental feature but a precondition for voluntary market engagement. Property leasing, especially under long-term or affordable schemes, implies an assumption of future institutional reliability. Owners must believe that:

Contracts will be enforceable in reasonable timeframes;

Rent defaults will be addressable through fair and functional legal channels;

Taxation and regulation will not be altered retroactively or punitively;

Programs implemented by the state will be administered transparently and without excessive bureaucratic burden.

In the absence of such trust, landlords act defensively. They may keep properties vacant, transfer them to short-term rentals, or divest altogether, not necessarily because such options yield higher returns, but because they offer greater autonomy and risk control.

This behaviour is not unique to Portugal. International studies have documented similar patterns in contexts as diverse as Poland, China, Canada, and Southern Europe more broadly, where erratic housing regulation and politicized, rental reforms have led to widespread disengagement by small-scale landlords (Zhou, 2023; Yeh & Zou, 2024; Jancewicz, 2023). In these cases, institutional fragility becomes a structural deterrent, not only to investment, but also to basic market functionality.

Beyond Legal Certainty: The Role of Symbolic Legitimacy

Importantly, trust is not limited to formal legal predictability. It also encompasses symbolic recognition, whether property owners feel respected, acknowledged, and fairly treated by public discourse and state policies. In the ALP surveys, many landlords reported feeling stigmatized or scapegoated in political rhetoric and media portrayals, contributing to their alienation from public housing efforts. This sense of being cast as antagonists rather than partners further discourages collaboration with public authorities.

As a result, distrust operates not only at the institutional level (courts, agencies, laws), but also at the relational level, eroding the possibility of mutual cooperation between the public and private sectors in expanding the housing supply.

3.3 Sociocultural and Patrimonialist Logics of Property

Beyond economic optimization and institutional incentives, property decisions, particularly among small-scale landlords, are deeply embedded in sociocultural norms, moral economies, and affective attachments. In Portugal, as in many Southern European contexts, housing ownership carries not only financial value, but profound symbolic, familial, and existential meanings. These meanings shape owners’ decisions to retain, underuse, or withhold properties, even in the face of economic rationales that might suggest otherwise.

This form of ownership logic, often referred to as patrimonialism, prioritizes the preservation of family assets, intergenerational continuity, and household autonomy over immediate profitability. Unlike financialized asset holders, patrimonialist owners may not perceive housing primarily as a source of yield or liquidity, but as a legacy good, a form of private social security, a cultural inheritance, or a buffer against personal or political instability (Vrantsis, 2025).

The profile of the Lisbon landlord: Elderly, Inherited, and Risk-Averse

Data from the ALP Barometers paints a consistent portrait of the typical landlord in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area:

Over 60% of respondents are aged 55 or older, with nearly half (48%) over 65.

More than 70% became landlords through inheritance rather than active investment.

Most own a small number of units (1 to 5), often in the same neighbourhoods where they or their families have historically resided.

This demographic structure contributes to a conservative and cautious ownership culture. Many landlords in this group view themselves not as investors but as custodians of family heritage. Their priority is not to maximize return, but to avoid loss, conflict, or reputational risk. This ethos encourages:

Refusal to rent to unknown tenants,

Reluctance to engage in bureaucratic public housing schemes,

Preference for keeping properties vacant “until needed” (e.g., for children),

And in some cases, maintaining symbolically significant properties even if they generate no income.

This logic mirrors patterns identified in other Southern European or post-socialist contexts where property has historically functioned as a refuge from economic uncertainty and an anchor of intergenerational stability (Jancewicz, 2023; Forrest & Hirayama, 2015).

Moral Economies and Social Responsibility

A further nuance to patrimonialist ownership in Portugal is the moral dimension that often accompanies housing decisions. Many landlords express not only economic concerns but also ethical dilemmas. Whether rent increases would harm vulnerable tenants, whether judicial eviction feels just, or whether placing a property in a state program would risk loss of control over whom it houses. ALP survey data confirms that:

10% of landlords intentionally refrained from raising rents in 2024 despite inflation, citing concern for tenants’ financial well-being;

15.6% report that they refuse to pursue eviction due to empathy with tenant hardship;

25% of landlords facing rent arrears believe legal action is not worth the emotional and financial cost.

This points to a complex affective economy of property, where decisions are filtered through personal morality, family history, and local social networks. Far from being mere capitalists, many landowners play roles as informal social providers, community members, and elders within family systems. However, there are other less noble strategies that are worth remembering. Indeed, recent audits by the General Inspectorate of Finance (IGF, 2023) reveal that a substantial share of rental relationships in Portugal may operate outside formal registration. According to the IGF, 60% of sampled tenants lacked a registered lease contract, and 25% of landlords with multiple properties had no declared rental activity, suggesting the existence of an extensive shadow rental market that remains statistically and fiscally invisible. This informal segment both distorts official housing vacancy indicators and undermines equitable taxation and tenant protection.

Finally, the decision to keep a property empty can be interpreted not just as avoidance or inertia, but as an assertion of autonomy and symbolic power. In a context where landlords increasingly feel attacked by public discourse and excluded from policymaking, vacancy becomes a form of silent resistance, a way to retain control over property in the face of perceived external threats. This framing helps explain why many owners reject state-run rental schemes, resist tax-based pressures, or react defensively to coercive proposals such as forced leasing.

Vacancy, in this sense, functions not only as market inefficiency, but as a radical political stance. A decision not to participate in a system that is seen as disrespectful, risky, or morally compromised.

3.4 Integrating the Three Frameworks

The interplay of financial strategy, institutional fear, and affective value forms what this paper refers to as a “patrimonial withdrawal ecology.” In this ecology, owners are not simply “speculators” or “hoarders,” but actors navigating uncertainty and mistrust with deeply personal stakes. Unlocking vacant housing, therefore, will require multi-level interventions that rebuild not only incentives but also confidence, recognition, and symbolic legitimacy.

Taken together, these three analytical forces (financialisation of housing, institutional trust, and patrimonial cultures of property) demonstrate that the desire to keep a property vacant rarely stems from a single cause or rationale. Instead, it arises from a universe of incentives, fears, and values that complement and reinforce each other. In Lisbon, owners are not only focused on optimising economic returns or reacting to political changes; they are also defending inherited legacies, managing perceived institutional risks and asserting their autonomy in a context of great political and cultural mistrust.

Understanding vacancy through this multidimensional framework allows us to move beyond simplistic binaries, such as “greedy landlords” versus “vulnerable tenants”, and to instead recognize the structural, symbolic, and emotional infrastructures that underpin owner behavior. Any meaningful housing policy aimed at mobilizing vacant housing stock must engage with these intersecting dynamics, not just by offering financial incentives, but by restoring institutional confidence, affirming cultural legitimacy, and designing programs that acknowledge the social identities of landlords as much as their economic interests.

4. Literature Review

While vacancy in housing markets is often framed as a question of supply inefficiency or policy failure, recent scholarship has highlighted the need to understand vacancy as a symptom of deeper structural, institutional, and cultural dynamics. This section reviews key strands of academic literature that inform this study, focusing on three interrelated bodies of work: (1) housing vacancy and landlord behaviour, (2) housing financialization, and (3) institutional trust and property governance.

4.1 Housing Vacancy and Landlord Behaviour

A growing body of research explores the complex motivations behind why property owners, especially small-scale landlords, may choose to withhold housing from the market. Classic economic models have tended to interpret vacancy as either a temporary market failure (e.g., frictional vacancy) or a sign of inefficient price signals. However, more recent empirical work challenges this narrow framing.

Studies in North America and Europe have shown that vacancy is often a deliberate and strategic choice, reflecting owners’ concerns about rent arrears, legal insecurity, tenant quality, and personal risk tolerance (Clauretie & Wolverton, 2006; Rehm & Yang, 2020). In contexts where tenant protections are strong and eviction processes are slow or costly, vacancy can appear to owners as a lower-risk alternative to renting.

In Portugal, although statistical evidence on vacancy is limited, localized studies and journalistic investigations have pointed to a significant number of underused or idle properties, especially in urban centers such as Lisbon and Porto. However, systematic academic research on landlord perspectives remains scarce, with most studies focusing on tenants, affordability, and housing policy outcomes.

4.2 Housing Financialization and Asset Logic

A major conceptual shift in housing studies over the past two decades has been the recognition of housing as a financialized asset, a process whereby housing becomes increasingly disconnected from use and repurposed as a vehicle for capital accumulation (Fuller, 2019; August, 2020; Wu et al., 2020).

Financialization has multiple expressions as speculative property hoarding, the conversion of long-term rentals into tourist accommodations, the rise of corporate landlords, and vacancy as a store-of-value strategy. In Lisbon, these dynamics have been amplified by tourism-driven gentrification, foreign investment, and liberalized short-term rental policies. Domínguez (2019) documents how housing in Lisbon’s historic neighborhoods has been transformed into investment commodities, often at the expense of long-term residential use (Domínguez, 2019; Reis & Fix, 2025).

Moreover, financialization intersects with everyday ownership practices. Even small-scale landlords increasingly adopt speculative mentalities, waiting for better market conditions or legal clarity before renting out properties. Studies across Canada, Spain, and Argentina similarly show that vacancy is often framed as a rational wealth management tool, particularly where rental yields are low or regulation is burdensome (Cruces, 2016; Lind, 2012; Vrantsis, 2025).

4.3 Institutional Trust, Policy Risk, and Owner-State Relations

Institutional trust is a crucial, and often overlooked, variable in housing market behavior. Property owners are more likely to engage in formal rental channels when they perceive the legal framework as stable, enforceable, and fair. Conversely, when landlords experience legal regimes as volatile, punitive, or ideologically hostile, they may opt out of leasing altogether (Yeh & Zou, 2024; Zhou, 2023).

This literature highlights the concept of regulatory uncertainty, a condition in which actors cannot reliably predict the rules that will govern their decisions over time. In Portugal, the rapid succession of housing reforms (e.g., rent caps, eviction moratoria, forced leasing proposals) has contributed to a deep erosion of owner confidence. The result is not only decreased supply, but a growing cultural rift between landlords and the state, in which public policies are met with suspicion rather than cooperation.

Case studies in European countries and China have shown that in such environments, informality, vacancy, or strategic conversion (e.g., to Airbnb or student housing) become more attractive than engagement with formal leasing programs (Jancewicz, 2023; Zhou, 2023; Ox Oxenaar et al., 2024).

4.4 Gaps in the Literature

Despite growing interest in these themes, significant gaps remain. Few studies combine institutional, economic, and sociocultural lenses to analyze property owner decisions (Singh et al., 2025). Even fewer focus on small-scale landlords in Southern Europe, a group that holds substantial housing stock but remains poorly understood in policymaking and research.

This study contributes to filling that gap by bringing together theories of financialization, trust, and patrimonial culture in the context of Lisbon’s housing crisis. It builds on but goes beyond the existing literature by incorporating empirical data from property owners themselves, thereby offering a more grounded understanding of why vacancy persists and how it might be addressed.

5. Lisbon Case Study: Distrust, and the Limits of Policy Activation

The Lisbon Metropolitan Area represents a critical test case for understanding the paradox of housing abundance amidst inaccessibility. Despite rising demand, thousands of residential units remain vacant, a phenomenon increasingly recognized by policymakers, but rarely unpacked from the perspective of the property owners themselves. Using data from multiple editions of the Barómetro da Confiança dos Proprietários (2020–2025), conducted by the ALP, this section analyzes the reasons landlords in Lisbon choose not to place their properties on the rental market.

5.1 Structural-Economic Factors: When Profitability is Not Enough

At first glance, the most straightforward explanation for why property owners refrain from renting might appear to be economic. The returns simply don’t justify the risk. However, in Lisbon, the situation is more nuanced. While affordability pressures have driven rents upwards and demand for housing remains consistently high, the rental market remains deeply unattractive to a significant segment of landlords, not necessarily because it offers no income, but because it offers the wrong kind of income, slow, uncertain, administratively burdensome, and emotionally taxing.

According to the ALP Barometers, only 15% of landlords ranked net rental yield as the most important factor in deciding whether or not to place a property on the market. Instead, an overwhelming 57.8% cited legislative predictability as the decisive variable, suggesting that the economic rationale for renting is continuously being overridden by other, less tangible concerns. While this might initially be interpreted as an institutional issue, and it is, in part, it also reveals something important about the structural fragility of rental income itself.

In Lisbon, many landlords are small-scale owners who acquired properties through inheritance rather than speculation. For them, real estate represents a store of value first, and a source of income second. In such a context, vacancy is not necessarily a sign of market dysfunction, but a form of asset stewardship. A way to avoid wear and tear, problematic tenants, potential legal entanglements, and the gradual erosion of control over one’s own property. This is particularly true in gentrifying neighborhoods, where property values are rising faster than the rate of rent increases. In such areas, it makes more sense, financially and psychologically, to hold onto the property until an opportune moment to sell, convert to short-term rental, or pass it on to a family member.

Indeed, some landlords have responded to the Mais Habitação policy package not by re-entering the rental market, but by withdrawing further. The VII Barometer (2024) recorded a 20% rise in rent increases that exceeded the legal indexation coefficient, not necessarily as a cash-grab, but as a hedge against anticipated regulation. Others have simply liquidated their rental assets: 9% of landlords reported having sold properties that were previously rented, and 6% transitioned their units from traditional leasing to short-term models like student housing or temporary rentals for foreign professionals.

This pattern suggests a deeper economic logic at work, one that prioritizes flexibility, control, and capital preservation over steady rental income. In effect, the structure of the rental market in Portugal, shaped by tax burdens, tenant protections, and opaque bureaucracies, has rendered rent not a reward, but a risk. The landlord, especially in Lisbon, must weigh not only the revenue potential of rent but the possibility of default, delays, legal costs, and the emotional toll of tenant conflict.

Seen in this light, vacancy becomes a form of risk management, a kind of informal insurance policy against an uncertain economic and institutional environment. It is a decision not rooted in short-term greed or negligence, but in a long-term calculus of security, autonomy, and asset optimization. Properties are held empty not because they are idle, but because they are active participants in a wider portfolio of life strategies, including retirement planning, inheritance management, and future speculation.

Thus, while financial profitability may seem like an obvious lever to unlock vacant housing, it is, paradoxically, not profitable enough, not in a landscape where risk is asymmetrical and policy is volatile. As long as the legal and financial costs of renting outweigh the modest gains it offers, many Lisbon landlords will continue to see vacancy as the least bad option.

5.2 Institutional and Legal Distrust: Opting out of an Unreliable System

While structural economic concerns help explain why renting is not particularly attractive in Lisbon, they do not fully account for the depth of resistance expressed by many property owners. A closer reading of survey data and landlord discourse reveals another, arguably more decisive force behind widespread vacancy: a profound and entrenched distrust in the institutions tasked with governing the housing market.

This distrust is not new. It has developed over decades of inconsistent policy, legal ambivalence, and perceived antagonism between property owners and the state. But recent years, particularly following the Mais Habitação package and pandemic-era rental protections, have intensified the fracture, transforming passive dissatisfaction into active disengagement. For many landlords, the rental market is no longer seen as a regulated space where agreements are enforced and rights respected. Instead, it has become what one might call a “grey zone” of legal uncertainty, where property rights feel contingent and where the rules appear vulnerable to sudden, ideologically driven change.

5.3 Sociocultural Dimensions: Patrimony, Identity, and the Right to Withhold

Beneath the economic calculus and legal hesitations that shape property owner behaviour in Lisbon lies a deeper, more intimate layer of motivation, one rooted not in profit or policy, but in cultural norms, affective attachments, and intergenerational logics of patrimony. For many landlords in Portugal, property is not merely an investment or a utility. It is a symbolic asset, woven into family identity, social status, and long-term life planning.

The ALP Barometers consistently reveal that most landlords in Lisbon are not corporate entities or large-scale investors, but older individuals managing inherited property. Over 60% of respondents are aged 55 and above, and a large proportion own between one and five units, often buildings passed down through generations, concentrated in the same neighbourhoods where they themselves live or grew up. These landlords operate not within the rationalist frameworks of institutional investors, but within what might be described as a “familiar moral economy”, where the use of property is embedded in kinship obligations, emotional continuity, and informal inheritance strategies.

Within this worldview, vacancy is not necessarily wasteful. It is often strategic and value-laden. An empty apartment may be reserved for a child or grandchild not yet ready to leave home. It may be kept unrented to avoid disputes, wear-and-tear, or conflicts that could tarnish a family asset. In other cases, it is simply held in stasis, neither sold nor leased, because it represents something more than shelter or income: it represents control, memory, dignity, and future security.

This “withholding” behavior aligns with a broader Southern European pattern, where homeownership has historically functioned as a substitute for underdeveloped welfare regimes. In Portugal, owning property is often a form of private social insurance. It provides backup housing in times of crisis, serves as a fallback pension, and enables parents to offer their children a foothold in increasingly unaffordable urban markets. As Vrantsis (2025) argues in the Greek context, but equally applicable here, real estate is often the most reliable asset in a context of institutional fragility and market volatility, and its symbolic value can eclipse any potential rental yield (Vrantsis, 2025).

This patrimonial logic also interacts with affective economies of risk. Older landlords, especially those with few properties, often describe themselves as emotionally unprepared for the strain of dealing with problematic tenants, eviction proceedings, or public bureaucracy. Many express a preference for “peace of mind” over income, and a strong desire to maintain full control over how, when, and to whom their property is leased. In this sense, leasing is not just a financial transaction, it is a relational exposure, one that many would prefer to avoid altogether.

Such choices are further reinforced by a moral narrative of responsibility. Contrary to stereotypes of landlord greed, many Lisbon owners describe themselves as careful, even paternalistic stewards of their properties. Some deliberately refrain from raising rents, even in the face of inflation, out of loyalty to long-term tenants. Others refuse to enter public programs because they believe the state would assign tenants they cannot vet personally, thereby compromising the integrity of the housing relationship. For these actors, rental decisions are guided not only by rational interest, but by reputational, familial, and emotional considerations.

Seen from this perspective, vacancy is neither passive nor antisocial. It is an active form of management, one that privileges long-term family strategies, personal autonomy, and asset preservation over short-term profit or public interest. It is, in effect, a cultural practice, shaped by generational memory, neighbourhood identity, and a deep scepticism of formal institutions.

As such, any policy that seeks to mobilize these vacant units must contend not only with legal and financial barriers, but also with these non-economic meanings of property. Designing effective interventions will require more than tax breaks or subsidies; it will demand culturally sensitive engagement with landlords’ values, identities, and lifeworld’s, and an acknowledgment that for many, renting out a home is not a business decision, but a deeply personal one.

This perception is not limited to rhetoric. It is grounded in concrete experience. Successive legislative shifts have altered the terms of leasing with little warning: rent freezes were reinstated after partial liberalization, eviction moratoria were introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic with minimal compensatory mechanisms, and the proposal for arrendamento coercive, forced leasing of vacant properties by municipalities, was interpreted by many as a direct threat to the sanctity of ownership itself. Such policies, even when temporary or largely symbolic, send a clear message to landlords: your property is not entirely yours.

The data from the ALP Barometers is unequivocal. In 2024, 96% of surveyed property owners stated they would not participate in state-run rental programs, even those offering favorable conditions or tax benefits. Equally striking, 92.7% said they would pursue legal action if their vacant property were requisitioned for public use under new legislation. These are not marginal sentiments. They represent a near-consensus among a critical mass of active landlords in Lisbon.

Distrust also extends beyond specific policies to broader institutional arrangements. Courts are seen as slow and unpredictable; tax regimes are viewed as punitive and retroactive; rental contract frameworks are considered biased in favor of tenants. Eviction processes, in particular, are cited repeatedly as a deterrent. While not always statistically common, the perception of “nightmare scenarios”, where non-paying tenants occupy properties for months or even years without resolution, carries extraordinary symbolic weight, especially among older landlords or those with limited financial buffers. In this sense, the fear of legal entrapment often outweighs the financial benefits of occupancy.

Importantly, this climate of mistrust is not only institutional but relational and cultural. Landlords often report feeling politically vilified, portrayed in public discourse as profiteers, speculators, or hoarders, rather than as contributors to urban housing ecosystems. This symbolic delegitimization further entrenches their resistance to state programs. As the ALP barometers reveal, many owners do not merely opt out of government schemes because they are inefficient; they do so because they feel fundamentally misrecognized by them.

What emerges from this data is not just a market failure, but a failure of mutual recognition between the state and a key class of urban stakeholders. While public authorities frame vacancy as a policy problem to be corrected, many owners experience it as a last refuge of autonomy in an environment where other rights, contractual, fiscal, reputational, have been gradually eroded.

Vacancy, in this light, becomes a political stance as much as a market behavior. It is a way for owners to assert control, to resist participation in systems they no longer trust, and to insulate themselves from what they see as an unstable and ideologically shifting legal terrain. This dynamic fundamentally alters how policymakers must approach the problem: no amount of financial incentive will succeed unless it is accompanied by a restoration of trust, legal predictability, and symbolic legitimacy.

5.4. The evolution of Landlord Confidence (2020–2025)

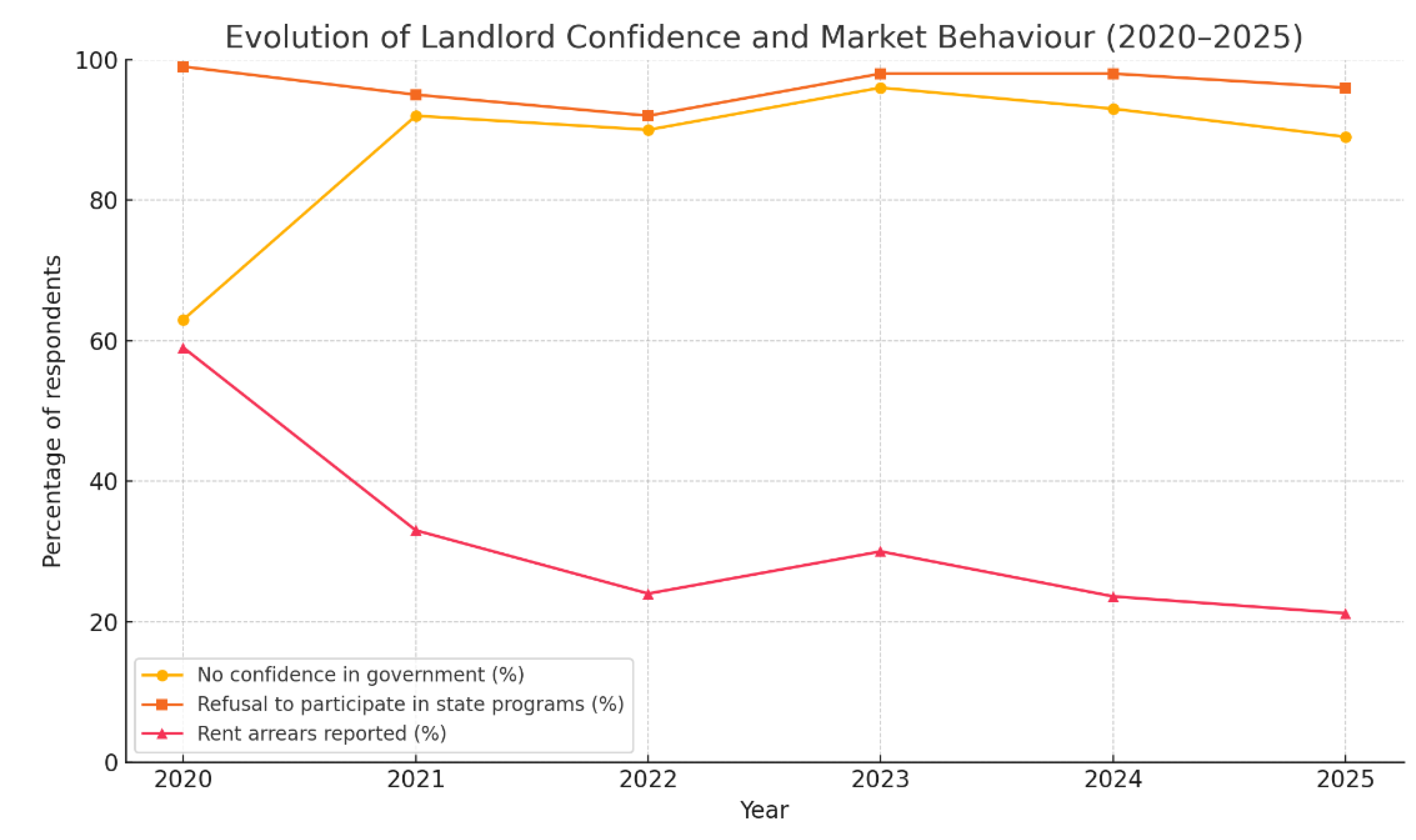

The trajectory of landlords' confidence over the five years covered by the ALP Landlords' Confidence Barometer (

Table 1) offers us a suggestive longitudinal dimension to the conclusions discussed above. Taken together, these barometers do not show inconsistent variations, but rather a constant and cumulative process of withdrawal and mistrust. What began in 2020 as a reaction to the pandemic and emergency legislation has gradually consolidated into a structural feature of the rental landscape in Portugal: a widespread belief that the institutional environment is unpredictable and that the safest response is disengagement.

Since the first edition, following the COVID-19 moratorium, more than half of landlords reported serious delays in rent payments and more than sixty per cent said they had lost confidence in the government's handling of the housing crisis. Five years on, the same scepticism dominates the responses, even though the context has changed. The 2025 Barometer shows that 57.8% of landlords now identify legal and legislative stability as the decisive factor determining their participation in the rental market, far surpassing profitability or taxation as reasons for acting. This is perhaps the most direct statistical confirmation to date of the argument put forward in this research. In concrete terms, the main barrier to the mobilisation of private housing is not economic in nature, but institutional and symbolic. Once eroded, trust does not return with tax incentives, as it requires the rebuilding of predictability and respect.

Over the course of half a decade, this erosion accelerated under the weight of political controversy. The 2023 More Housing package, designed to expand the supply of rentals, had the opposite effect. According to ALP data, two in ten landlords sold previously rented properties, while another in ten increased rents or converted them to short-term rentals. More tellingly, 96% of respondents said they would not rent to the state under any circumstances, and over 92% said they would go to court if faced with compulsory leases. The package, designed to engage landlords, ended up reinforcing the perception that government policy was volatile and contradictory. In subsequent editions, this sentiment did not diminish, as in 2024, about a quarter of landlords still reported delays in rent payments and more than half said they expected the situation to worsen.

The profile of landlords remained stable throughout this period. Each barometer confirms that the Portuguese rental market continues to be dominated by elderly, small-scale landlords (around 60% are over 55 years old and half have inherited their properties rather than buying them as an investment). The 2025 Barometer makes this dynamic explicit, noting that 44% of landlords are between 65 and 85 years old and that 58% did not even apply for the state compensation available for frozen rents, largely because they considered the process bureaucratically exhausting or unreliable. These details lend empirical depth to the argument developed earlier in this article, that the apparent “inertia” of landlords is in fact a culturally rooted strategy of protection and continuity.

Over these five years, the data reveal a consistent pattern of mainly defensive rationality. Landlords report similar levels of rent arrears (ranging from 20 to 30 per cent of respondents) and an almost unchanged refusal to participate in public programmes (over 90 per cent in all editions). Even with the change in the political landscape (from the socialist majority of the pandemic era to the new centre-right coalition in 2025), the feeling of mistrust persisted. As the latest Barometer concludes, most respondents do not believe that the current government's tax reforms or “housing shock” initiatives will change their behaviour. Half say they will not put additional units on the market, and most will limit rent increases to the legal indexation coefficient.

Taken together, these successive surveys over the past five years transform what might appear to be a one-off dissatisfaction into a measurable continuity. The data reveals a class of small property owners who have learned to live defensively, conserving their property, avoiding involvement with state programmes and considering the legal framework as an unpredictable risk. In this sense, the housing crisis in Lisbon is not a temporary distortion of market dynamics, but the external symptom of long-term institutional fatigue. The lack of trust documented in the ALP Barometers for 2020-2025 reveals a housing system mired in mutual suspicion, where private landlords no longer expect the state to be a “person of good faith” and where public policies oscillate between dependence and hostility towards them. The challenge for the coming years will not only be to legislate differently, but to rebuild a relationship of trust, without which no incentive, however generous, will be able to transform empty houses into homes for families to live in.

The case studied suggests that the mechanisms underpinning vacancy are not isolated acts of resistance or purely cultural reflexes (

Figure 1). They are reproduced by a political environment that alternates between over-regulation and crisis management. Before proposing solutions, it is necessary to recognise that the governance structure itself has become a generator of risk perception.

6. Vacancy as a Rational Withdrawal in a Dysfunctional System

The findings from the Lisbon case reveal a picture far more complex than the conventional narrative of “empty homes amidst housing crisis” might suggest. Rather than irrational or speculative, the decision to withhold properties from the rental market emerges as a rational withdrawal, a strategic and often deeply personal response to a dysfunctional set of market signals, institutional arrangements, and sociocultural expectations. Vacancy, in this context, is not an aberration but a symptom: a symptom of mistrust, policy volatility, and the misalignment between public objectives and private realities.

The three primary rationales identified, financial caution, institutional distrust, and patrimonial logic, reflect not only different motivations, but different modes of risk perception. For the economically cautious owner, vacancy is a hedge against weak rental yields and rising regulatory costs. For the distrustful owner, it is a shield against perceived state overreach and legal uncertainty. For the patrimonial owner, it is a means of preserving identity, dignity, and intergenerational autonomy. These rationales are not mutually exclusive. In many cases, they reinforce each other, creating a layered ecology of non-participation.

What this suggests is that vacancy in Lisbon is not caused by a single market failure or policy gap, but by structural misalignment across certain domains: Economic incentives are too weak, especially when weighed against the perceived risks of tenancy and regulation; Institutional frameworks lack credibility, undermining landlords’ willingness to engage with formal rental programs; Cultural and affective dimensions of property are overlooked, leading to policies that fail to resonate with the lived realities of small-scale owners.

From a theoretical perspective, the Lisbon case reinforces the need to treat housing not only as a financial or regulatory matter, but as a socially embedded asset, shaped by affect, morality, and historical memory. The symbolic dimension of ownership, particularly in societies with strong familial property cultures, plays a crucial role in shaping behavior, often in ways that defy conventional economic logic.

Furthermore, the findings highlight a paradox at the heart of housing governance: the very policies designed to increase access to housing can, if perceived as coercive or unstable, deepen vacancy and push owners further out of the system. For instance, rent freezes, forced leasing, or abrupt tax shifts, even if justified by public need, may inadvertently validate landlords’ worst fears and reinforce their disengagement.

This does not mean that regulation is inherently counterproductive. Rather, it underscores the importance of predictability, procedural fairness, and symbolic legitimacy. Landlords will not be compelled into participation through pressure alone. They must also be invited into partnership, with policy frameworks that offer not just incentives, but respect and recognition.

Finally, the case of Lisbon points to a broader conceptual shift: rather than seeing vacancy as a purely negative externality, we might understand it as a barometer of institutional health. Persistent vacancy in the presence of high demand reveals not just a mismatch of supply and need, but a rupture in the social contract of housing, a breakdown of trust, reciprocity, and cooperation between private owners and public institutions.

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The Lisbon case reveals a paradox that extends beyond the local housing market. Over half a decade of evidence demonstrates that landlords’ withdrawal from the rental sector is not simply an economic reaction to low returns, but a rational adaptation to a context defined by legal instability, fiscal volatility, and symbolic delegitimisation. Financialisation and regulation, far from being opposing forces, have interacted to produce an environment in which property is both an investment vehicle and a potential liability. The outcome is a pervasive “defensive rationality”: property owners conserve, rather than circulate, their assets, thereby reproducing vacancy as a structural feature of the urban landscape.

7.1 Structural Predictability

At the heart of the crisis is the lack of legal and fiscal predictability. Longitudinal ALP Barometers (2020-2025) show that legislative instability now surpasses profitability as the main determinant of landlords' behaviour. Policies should therefore prioritise durability over novelty. The introduction of multi-year stability clauses in rental legislation, ensuring that contractual frameworks and fiscal conditions cannot be changed retroactively, would send a strong signal of reliability. Similarly, tax reform should aim for neutrality rather than incentives, as simplifying tax codes and unifying deductions for small landlords would reduce the perception of discretionary intervention that currently drives defensive behaviour.

7.2 Relational Trust

Rebuilding trust requires more than legal initiatives. Evidence shows that landlords view the state not as a partner, but as an adversary with unpredictable behaviour. To counter this perception, intermediary institutions are essential. Independent real estate agencies or municipal funds could act as mediators, ensuring transparent communication, fair dispute resolution, and guarantees against unilateral policy reversals. These intermediaries would translate abstract policies into credible practices, restoring relational trust where institutional trust has been degraded.

7.3 Socio-Cultural Recognition

The data also show that Portuguese landlords are predominantly elderly and often owners ‘by inheritance’. Their relationship with housing is patrimonial and affective, as well as economic. Policies that frame landlords merely as actors seeking income ignore this dimension and thus alienate them. Measures based on recognition, for example, heritage-sensitive rehabilitation programmes or the symbolic recognition of long-standing small property owners as civic contributors, can rebuild legitimacy. Integrating this sociocultural understanding into housing policy is not a mere aspect. It is more the pragmatic recognition of the moral economy that underpins real estate decisions.

7.4 Institutional Coherence

The case of Lisbon further highlights how successive and contradictory policy packages have eroded credibility. Fragmented interventions, oscillating between punitive taxation and subsidy schemes, signal a short-term vision and amplify the uncertainty. A coherent national framework for housing, ideally enshrined in a parliamentary agreement between parties, would stabilise expectations across political cycles. The focus must shift from piecemeal and incoherent responses to the crisis to institutional reliability. Only coherence can transform the relationship between private owners and public objectives from transactional to cooperative.

7.5 Beyond Incentives

Finally, evidence shows that fiscal incentives alone are not enough to rebuild lost trust. Trust is cumulative and relational; it cannot arise spontaneously. The challenge is not so much to create new subsidies by throwing money at the problem, but to ensure that existing promises are kept. This requires transparent monitoring, accessible complaint mechanisms, and political discipline to uphold the rules once they are established.

As a final point, it should be emphasised that the documented evolution between 2020 and 2025 suggests that the problem of vacant housing in Lisbon is not an anomaly in market behaviour, but rather a reflection of a persistent governance deficit. Restoring confidence (legal, institutional and symbolic) is therefore an essential prerequisite for any effective housing strategy. Without predictability, recognition and consistency, vacant housing will continue to be silent monuments to mutual distrust between citizens and the state.