Introduction

Bryophytes and lichens represent a significant component of Antarctic terrestrial vegetation, particularly in ice-free coastal and mountainous regions (Colesie et al., 2023). These cryptogamic organisms have adapted to the continent's extreme conditions and often dominate primary colonization zones where vascular plants are absent or rare. In addition to their visible structural role in Antarctic ecosystems, they also function as microhabitats for diverse and often specialised microbial assemblages (Benavent-González et al., 2018). The microbial communities associated with Antarctic bryophytes and lichens play a vital role in nutrient cycling, ensuring the resilience and adaptation of ecosystems to extreme conditions (Doytchinov & Dimov, 2022). These microbiomes comprise diverse bacteria, fungi and microalgae, many of which possess unique physiological and metabolic traits that enable them to survive in conditions such as freezing temperatures, intense UV radiation and prolonged desiccation. The interactions between these microbes and their host organisms influence nutrient acquisition, stress tolerance and the overall functioning of ecosystems in polar regions (Zhang et al., 2025).

Previous studies have shown that Antarctic mosses, lichens and soils host distinct microbial communities that differ in both composition and function, reflecting their contrasting microenvironments and nutrient regimes (Zhang et al., 2025). Mosses often harbour metabolically versatile microbiomes enriched in Actinobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota and Cyanobacteria that contribute to nitrogen fixation and organic matter turnover (Henrique Rosa et al., 2021). In contrast, lichens represent complex symbiotic systems combining fungi with algal and/or cyanobacterial partners. The bacteria associated with lichens are typically dominated by stress-tolerant taxa such as Pseudomonadota and Sphingomonadota, which play an important role in photoprotection, nutrient exchange and environmental stress mitigation (Grimm et al., 2021). In comparison, soils generally harbour the most taxonomically and functionally diverse bacterial communities, supporting complete nutrient cycles and acting as reservoirs for cryptogam-associated microbes (Klarenberg et al., 2023). Despite these insights, comprehensive metagenomic comparisons across moss, lichen and soil microbiomes in Antarctica remain rare, limiting our understanding of how host identity and substrate conditions shape microbial diversity and functional potential in extreme terrestrial ecosystems.

Andreaea and Usnea frequently co-occur in Antarctic terrestrial ecosystems, particularly in ice-free coastal and mountainous regions (Sancho et al., 1999). The spatial association of these organisms has been thoroughly documented in studies from King George Island, where cushions of the widespread lichen Usnea antarctica provide positive microhabitat effects that facilitate the establishment and growth of co-occurring species, including moss Andreaea (Molina-Montenegro et al., 2013). These positive effects by Usnea cushions can mitigate harsh microclimatic conditions by increasing soil moisture and temperature while reducing UV radiation and evaporative water loss, thereby supporting a richer associated biota and enhancing plant survival in extreme environments.

Based on these ecological and physiological contrasts, we hypothesised that host identity is the primary factor that structures microbial communities and their metabolic potential in Antarctic terrestrial habitats. Mosses, lichens and soils represent distinct yet interconnected microhabitats that differ in nutrient availability, exposure and biological complexity. This unique assemblage provides a framework for exploring how environmental filtering and host association shape bacterial diversity and metabolism in extreme ecosystems. This study aims to compare the microbial assemblages associated with Andreaea regularis, Usnea aurantiacoatra and adjacent soils in order to determine the role of host specificity and habitat conditions in shaping microbiome composition and functional potential.

Materials and Methods

Site Description and Sampling

Environmental samples of

Andreaea,

Usnea and adjacent soil were collected from Mount Reina Sofía on Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica, during a field campaign in January 2025 (

Figure 1). The sampling sites were located in close proximity to the Spanish Antarctic Station Juan Carlos I. The local climate is characterised by mean monthly air temperatures ranging from 2.2°C in February to -5.1°C in July, with an annual mean of -1.2°C, and a mean annual wind speed of 14 km h⁻¹. For each sample type, three technical replicates were obtained at two distinct elevations: low (44 m a.s.l.; samples marked with L) and high (276 m a.s.l., samples marked with H). The collected samples were then dried at room temperature, placed in sterile bags, and transported to the laboratory for further analyses.

Phylogenetic Identification of Moss and Lichen Samples

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) reads were then extracted from the filtered dataset using SortMeRNA to enable taxonomic verification and species identification of the collected moss and lichen samples. To verify the taxonomic identity of the collected moss and lichen samples, rRNA reads were assembled using CAPTUS (Ortiz et al., 2024). All available assemblies of Andreaea and Usnea species, along with appropriate outgroup assemblies, were retrieved from GenBank for comparative analysis. For the Andreaea samples, chloroplast protein-coding markers were identified and extracted from the assemblies using the SeedPlantsPTD reference dataset, which includes chloroplast proteins conserved across seed plants. The minimum percentage of coverage required for marker retention was set to 50%. For the Usnea samples, the annotated Usnea florida assembly (GCA_052784015.1) was used as the reference to search and extract nuclear markers from both Usnea and outgroup assemblies. The minimum percentage of sequence identity required for marker retention was set to 70%. Only alignments that included all six collected Usnea samples were retained, resulting in a final dataset of 21 gene alignments.

Alignments for all extracted markers were generated using CAPTUS align with the maximum number of paralogs set to zero. Further, alignments for Andreaea and Usnea were concatenated separately using the phyx toolkit (pxcat; Brown et al. 2017). The concatenated sequences were aligned with MAFFT (v7.508; Katoh and Standley 2013) and trimmed using phyx (pxclsq) to remove alignment columns with <10% data presence. Model selection was performed for each partition using ModelFinder in IQ-TREE 3 (Wong et al., n.d.), and clade support was evaluated with 1,000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates. Resulting phylogenies were visualized in FigTree v1.4.4, with final graphical annotations completed in Adobe Illustrator v29.5.1.

In addition, pairwise sequence similarity among samples and reference taxa was further assessed by BLAST analysis of all retrieved Andreaea marker genes (petB, psbA, psbB, psbE, psbF, psbL, psbT, rpl2, rps12_exon_2_3, rps19, rps2, rps7) against corresponding sequences from GenBank.

Results

Species Identification of Andreaea and Usnea

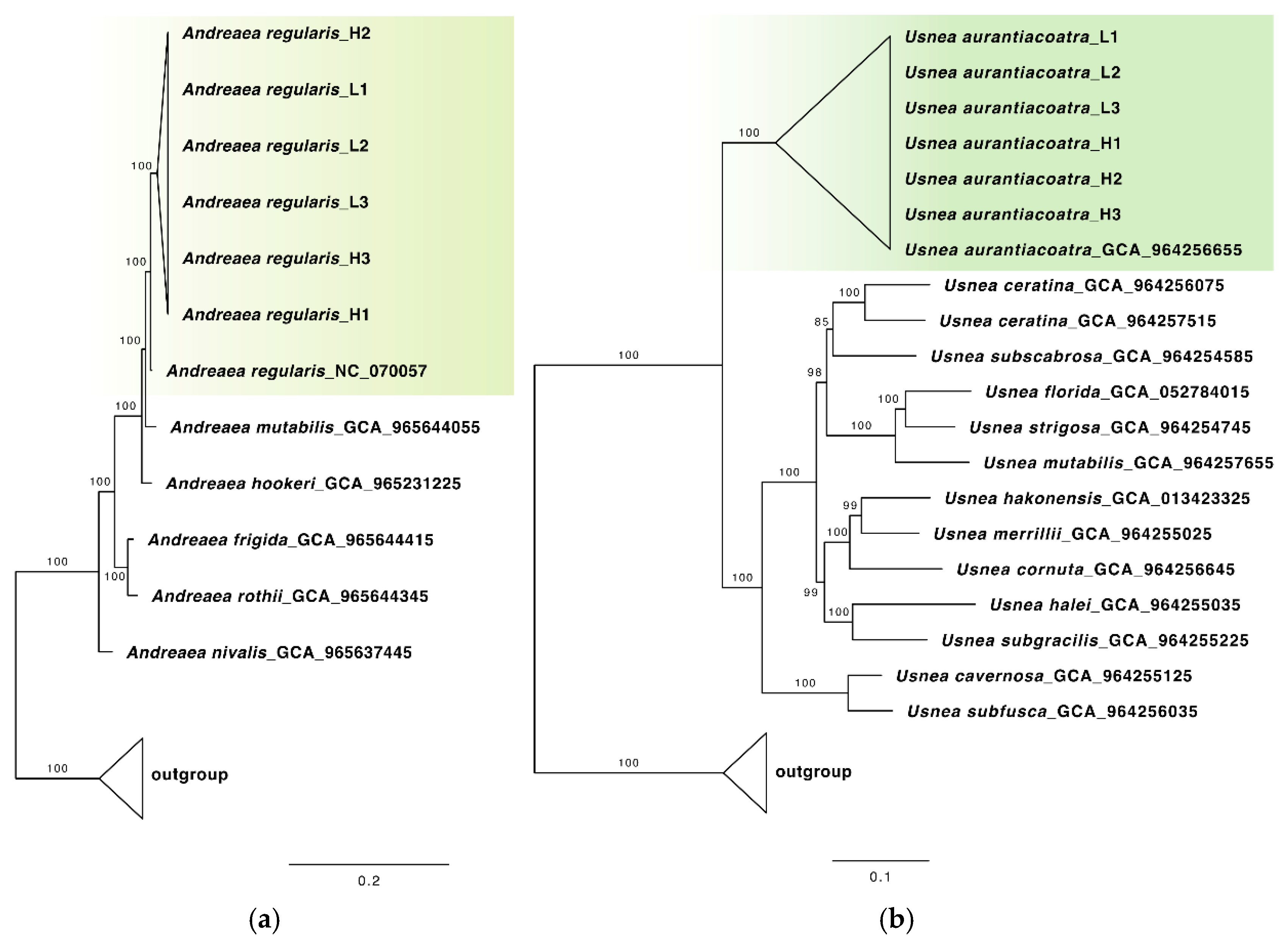

Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that all six

Andreaea samples formed a strongly supported clade sister to the Antarctic moss

Andreaea regularis (NC_070057;

Figure 2a). The marker gene sequences of the samples were almost identical to the reference sequence, with the exception of two replicates of

Andreaea collected at high elevation (H1 and H3). These samples exhibited approximately 1% nucleotide divergence relative to the other samples (up to five single nucleotide polymorphisms per gene), which is consistent with intraspecific variation. All

Usnea samples were found to cluster within a well-supported clade with

Usnea aurantiacoatra (GCA_964256655.1;

Figure 2b), exhibiting 100% sequence identity across all analysed genes. Overall, these findings confirm that the collected moss and lichen samples belonged to

A.

regularis and

U.

aurantiacoatra, respectively.

Functional Profile of the Bacterial Microbiome

Based on the RefSeq database (Kraken2), soil samples contained the highest number of bacterial reads (26 million), followed by A. regularis (15 million) and U. aurantiacoatra (13 million). U. aurantiacoatra harbored the least complex microbiome, yielding 9,200 metagenomic contigs (Suppl. Table S2). In contrast, the soil microbiome was the most complex, with approximately 500,000 contigs, whereas A. regularis produced roughly 40% more contigs than soil.

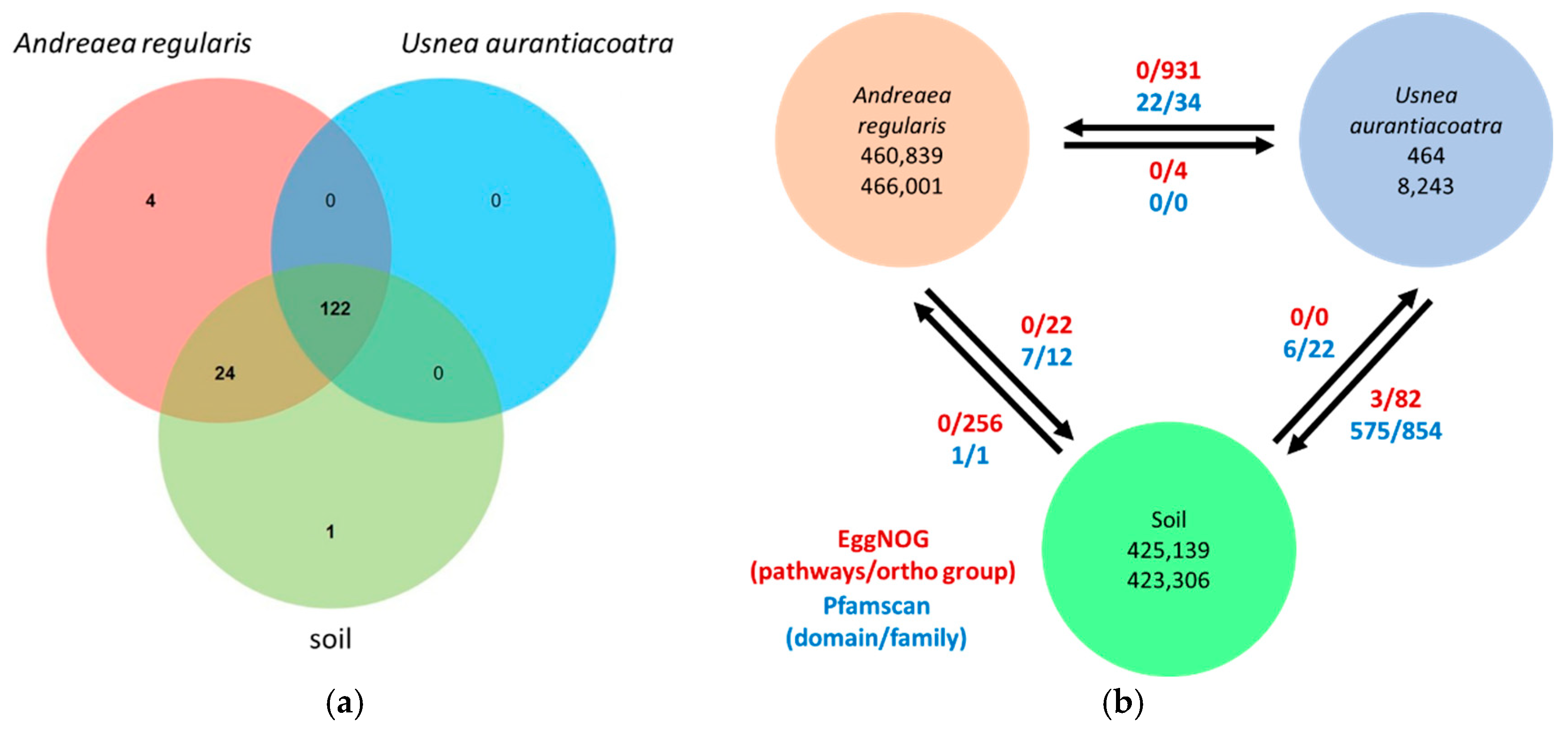

KEGG pathway analysis identified 151 pathways in total, of which 122 were shared among all three substrate types (

Figure 5a; Suppl. Table S3). Four pathways were uniquely associated with

A. regularis (cutin, suberine and wax biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis, monoterpenoid biosynthesis, and biosynthesis of various other secondary metabolites) while a single pathway, tetracycline biosynthesis, was unique to soil. No pathways were uniquely associated with

U. aurantiacoatra.

Pairwise comparisons of functional metagenomic profiles based on EggNOG (orthogroup and pathway) and PfamScan (domain and family) annotations revealed distinct patterns of functional enrichment among

A.

regularis,

U.

aurantiacoatra and soil (

Figure 5b, Suppl. Tables S4 and S5). The analysis of EggNOG annotations revealed that

A. regularis exhibited an enrichment of 931 orthogroups in comparison to

U. aurantiacoatra and 256 orthogroups in comparison to soil. In contrast, soil exhibited enrichment in 22 orthogroups in comparison with

A. regularis and 82 relative to

U. aurantiacoatra. The

U. aurantiacoatra microbiome demonstrated an enrichment of five orthogroups in comparison with

A. regularis, and none in comparison with soil.

PfamScan-based comparisons revealed a different pattern. The biggest functional differences were seen between soil and U. aurantiacoatra, with 575 domains and 854 families overrepresented in soil, and only six domains and 22 families enriched in U. aurantiacoatra. The differences between A. regularis and U. aurantiacoatra were minimal, with no overrepresented domains or families in U. aurantiacoatra and 22 domains and 34 families enriched in A. regularis. Similarly, a comparison between A. regularis and soil revealed limited variation, with one domain and one family enriched in A. regularis and seven domains and 12 families enriched in soil.

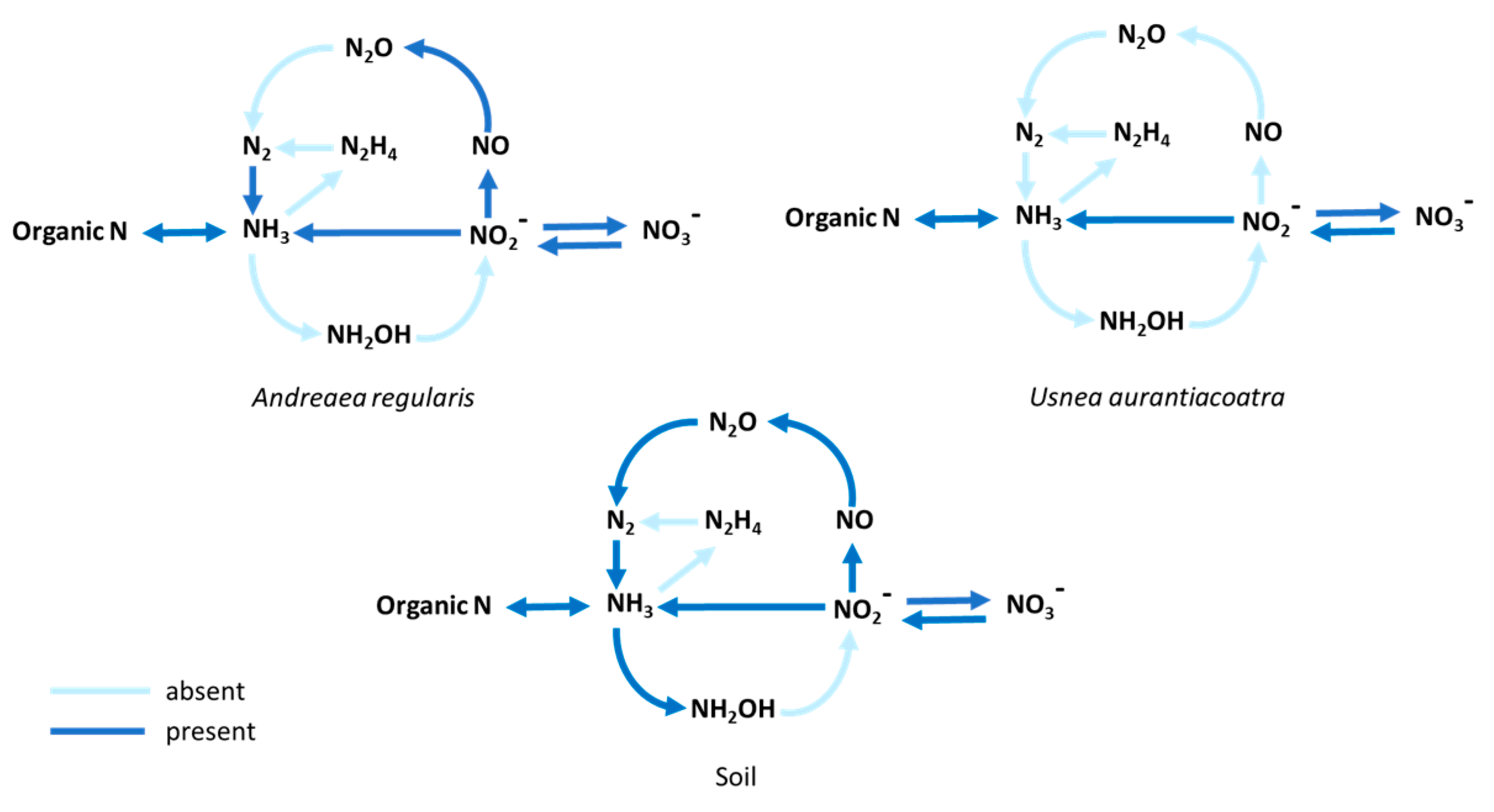

Furthermore, the functional annotation of nitrogen-cycle genes exhibited variation among

A. regularis, U. aurantiacoatra and soil (

Figure 6). The soil microbiome exhibited an almost complete set of genes associated with nitrification, denitrification, and nitrogen fixation, whereas

A. regularis demonstrated a partial set, with several steps absent. In contrast,

U. aurantiacoatra showed the most reduced representation, lacking multiple enzymes involved in denitrification.

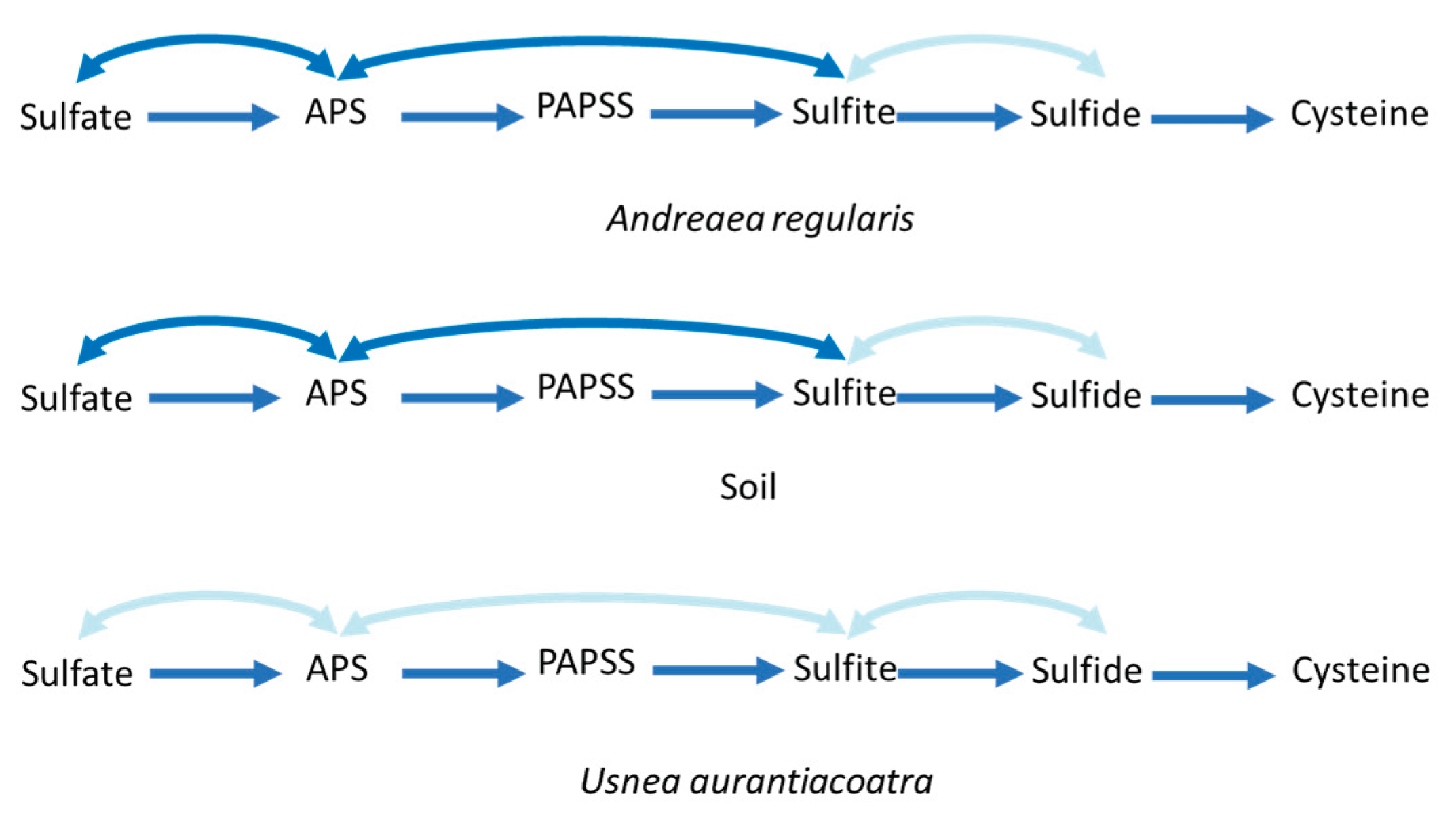

Genes involved in the assimilatory sulfate reduction pathway were detected in all sample types (

Figure 7, Suppl. Table S6). The

A. regularis and soil microbiomes contained nearly complete sets of genes associated with both assimilatory (e.g.,

PAPSS/Sat/CystNC/CystD, CysC, CysH, CysJ/Sir) and dissimilatory sulfate reduction and sulfide oxidation pathways (Sat, AprB), whereas the key genes converting sulfite to sulfide (

Dsr) were absent. In contrast, the microbiome of

U. aurantiacoatra exhibited only a minimal representation of assimilatory genes and lacked all detectable genes associated with dissimilatory sulfate reduction and sulfide oxidation. The SOX system (thiosulfate → sulfate) was present in moss and soil, but absent in the lichen-associated community.

A diverse array of ABC transporter genes was detected in all sample types, with the highest total counts in A. regularis (19K), followed by soil (15K) and markedly lower numbers in U. aurantiacoatra (272; Suppl. Table S6). Genes encoding iron (AfuA), phosphate (pstB), sulfate (CysA) and nitrate (NrtA) transport systems were present in all microbiomes, though in substantially higher abundance in moss and soil compared with lichen. Furthermore, genes associated with siderophore biosynthesis were identified in all environments, with the highest prevalence observed in moss and soil samples, as compared to lichen samples.

Discussion

Functional Potential of Bacteria Associated with Moss, Lichen and Adjacent Soil

The functional metagenomic profiles of moss, lichen, and soil revealed pronounced differences in bacterial community complexity and metabolic potential, reflecting distinct ecological roles of these microbiomes within the Antarctic terrestrial ecosystem. Among the cryptogamic hosts, A. regularis exhibited a broader functional repertoire than U. aurantiacoatra, including four metabolic pathways detected exclusively in the moss microbiome. Three of these pathways (cutin, suberine and wax biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis and monoterpenoid biosynthesis) are typically associated with plant metabolism, suggesting possible eukaryotic contributions from bryophyte tissue or from epiphytic green algae potentially present within the moss cushion. In contrast, the lichen microbiome showed no unique pathways, consistent with its reduced metabolic diversity and strong symbiotic dependence. The soil microbiome displayed the greatest overall functional complexity and uniquely harboured the tetracycline biosynthesis pathway, characteristic of actinomycetes such as Streptomyces spp. (Pickens & Tang, 2009). This likely reflects intense microbial competition in soil environments, where antibiotic production provides a selective advantage (Maan et al., 2022). The absence of this pathway in A. regularis and U. aurantiacoatra suggests that antibiotic-producing taxa are either rare or unnecessary in these more specialized host-associated microbiomes.

Water and nutrient availability are the main growth-limiting factor for organisms in Antarctic terrestrial ecosystems (Convey, 2010). Given the close spatial proximity of A. regularis and U. aurantiacoatra on the same rock substrate, differences in water supply were likely minimal, although the moss cushion may retain moisture more effectively than the lichen thallus. Consequently, differences in nutrient metabolism, particularly nitrogen (N) and sulfur (S), were investigated to elucidate how associated bacterial communities may contribute to host nutrient acquisition.

The reconstruction of the bacterial nitrogen cycle revealed strong contrasts among the three sample types. In soil, nearly the complete bacterial N-cycle was represented, with hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO) being the only enzyme missing. In the A. regularis microbiome, nitrification was not detected and denitrification appeared incomplete, with the absence of nitrous oxide reductase confirmed by pairwise PfamScan comparisons, suggesting a consistent pattern rather than a stochastic absence due to sequencing coverage. In contrast, the U. aurantiacoatra microbiome exhibited the most reduced nitrogen cycle and the genes associated with nitrogen fixation were absent, despite the presence of bacterial taxa typically linked to diazotrophic potential (Grimm et al., 2021). This absence suggests that the bacteria associated with the lichen may have lost the capacity for nitrogen fixation, possibly as an adaptation to the stable yet nutrient-limited Antarctic environment (Woltyńska et al., 2023). In contrast, both A. regularis and soil bacterial community harboured nitrogenase-encoding genes, indicating potential for atmospheric N₂ fixation. Furthermore, large proportion of sequences were assigned to nitrate assimilation and to the GS/GOGAT pathway, which converts ammonia into organic nitrogen, whereas most other nitrogen-cycle functions were represented by only a few sequences. This imbalance suggests that, despite the apparent diversity of nitrogen-related pathways, microbiomes of moss, lichen and soil, might rely primarily on external nitrogen inputs rather than on internal recycling (Tian et al., 2023).

The detection of assimilatory sulfate-reduction genes across all samples could indicate that sulfur assimilation is a conserved metabolic function among bacterial communities in different types of substrates (Mukhia et al., 2024). In general, dissimilatory sulfate reduction occurs less frequently compared to assimilatory sulfate reduction (Linz et al., 2018), which was also observed in this study. Besides, the complete absence of the AprB and Sat genes, converting SO₄²⁻ (sulfate) to SO₃²⁻ (sulfite), in the U. aurantiacoatra microbiome could indicate a restricted sulfur metabolism, likely reflecting the stable, host-regulated conditions within the lichen thallus where energy generation via sulfur compounds is unnecessary or replaced by host-derived substrates.

ABC transporters and siderophore biosynthesis pathways are essential for microbial nutrient acquisition in nutrient-limited environments (Akhtar & Turner, 2022). The enrichment of these genes in the A. regularis and soil microbiomes might indicate the competitive and oligotrophic conditions characteristic of free-living microbial communities in Antarctic moss and soil, where nutrient and metal availability are highly variable (Styczynski et al., 2022). Similar to observations from deep-sea hydrothermal vent systems, where microbial communities actively express siderophore-related and ABC transporter genes to scavenge particulate iron (M. Li et al., 2014), the moss and soil microbiomes may rely on analogous mechanisms for mobilizing mineral-bound Fe under cold and nutrient-poor conditions. In contrast, the lichen’s tightly regulated symbiotic system likely provides a more stable internal nutrient supply, reducing the need for external nutrient uptake and iron scavenging.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the microbiomes of Antarctic cryptogams and surrounding soils exhibited a clear host-dependent structuring pattern, with soils and A. regularis harbouring diverse and metabolically versatile bacterial communities, while the U. aurantiacoatra maintained a smaller and more specialised consortium. These differences were also reflected in functional capacities, with soil bacteria demonstrating the broadest metabolic potential, moss-associated bacteria retaining partial functional capabilities, and lichen-associated bacteria showing the most reduced representation of key metabolic pathways. Overall, these findings provide a comparative framework for understanding the structure and functional potential of cryptogam-associated and soil microbiomes in Antarctic ecosystems.

Funding

This study was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) within the project PU867/1-1.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of Juan Carlos I Station in Antarctica for their technical and logistical support during sampling. We are also grateful to Leonie Keilholz for her assistance in the laboratory.

References

- Asaf, S., Khan, A. L., Khan, M. A., Al-Harrasi, A., & Lee, I.-J. (2018). Complete genome sequencing and analysis of endophytic Sphingomonas sp. LK11 and its potential in plant growth. 3 Biotech, 8(9), 389. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A., Casanova-Katny, A., & Gerasimova, J. (2023). Metabarcoding of Antarctic Lichens from Areas with Different Deglaciation Times Reveals a High Diversity of Lichen-Associated Communities. Genes, 14(5), 1019. [CrossRef]

- Benavent-González, A., Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Fernández-Brun, L., Singh, B. K., Maestre, F. T., & Sancho, L. G. (2018). Identity of plant, lichen and moss species connects with microbial abundance and soil functioning in maritime Antarctica. Plant and Soil, 429(1–2), 35–52. [CrossRef]

- Chi, J., Lee, H., Hong, S. G., & Kim, H.-C. (2021). Spectral Characteristics of the Antarctic Vegetation: A Case Study of Barton Peninsula. Remote Sensing, 13(13), 2470. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A. V., De Oliveira, A. J., Tanabe, I. S. B., Silva, J. V., Da Silva Barros, T. W., Da Silva, M. K., França, P. H. B., Leite, J., Putzke, J., Montone, R., De Oliveira, V. M., Rosa, L. H., & Duarte, A. W. F. (2021). Antarctic lichens as a source of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. Extremophiles, 25(2), 181–191. [CrossRef]

- Dennis, P. G., Newsham, K. K., Rushton, S. P., O’Donnell, A. G., & Hopkins, D. W. (2019). Soil bacterial diversity is positively associated with air temperature in the maritime Antarctic. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 2686. [CrossRef]

- Fernández Zenoff, V., Siñeriz, F., & Farías, M. E. (2006). Diverse Responses to UV-B Radiation and Repair Mechanisms of Bacteria Isolated from High-Altitude Aquatic Environments. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72(12), 7857–7863. [CrossRef]

- Grimm, M., Grube, M., Schiefelbein, U., Zühlke, D., Bernhardt, J., & Riedel, K. (2021). The Lichens’ Microbiota, Still a Mystery? Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.-M., Yan, Y.-C., Zhang, Q., Liu, B.-Q., Wu, C.-S., & Wang, L.-N. (2023). Phytochemical composition, antimicrobial activities, and cholinesterase inhibitory properties of the lichen Usnea diffracta Vain. Frontiers in Chemistry, 10, 1063645. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., & Rousk, K. (2022). The moss traits that rule cyanobacterial colonization. Annals of Botany, 129(2), 147–160. [CrossRef]

- Mashamaite, L., Lebre, P. H., Varliero, G., Maphosa, S., Ortiz, M., Hogg, I. D., & Cowan, D. A. (2023). Microbial diversity in Antarctic Dry Valley soils across an altitudinal gradient. Frontiers in Microbiology, 14, 1203216. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Montenegro, M. A., Ricote-Martínez, N., Muñoz-Ramírez, C., Gómez-González, S., Torres-Díaz, C., Salgado-Luarte, C., & Gianoli, E. (2013). Positive interactions between the lichen Usnea antarctica (Parmeliaceae) and the native flora in Maritime Antarctica. Journal of Vegetation Science, 24(3), 463–472. [CrossRef]

- Naz, B., Liu, Z., Malard, L. A., Ali, I., Song, H., Wang, Y., Li, X., Usman, M., Ali, I., Liu, K., An, L., Xiao, S., & Chen, S. (2023). Dominant plant species play an important role in regulating bacterial antagonism in terrestrial Antarctica. Frontiers in Microbiology, 14, 1130321. [CrossRef]

- Nishu, S. D., No, J. H., & Lee, T. K. (2022). Transcriptional Response and Plant Growth Promoting Activity of Pseudomonas fluorescens DR397 under Drought Stress Conditions. Microbiology Spectrum, 10(4), e00979-22. [CrossRef]

- Park, C. H., Kim, K. M., Elvebakk, A., Kim, O., Jeong, G., & Hong, S. G. (2015). Algal and Fungal Diversity in Antarctic Lichens. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 62(2), 196–205. [CrossRef]

- Park, C. H., Kim, K. M., Kim, O.-S., Jeong, G., & Hong, S. G. (2016). Bacterial communities in Antarctic lichens. Antarctic Science, 28(6), 455–461. [CrossRef]

- Popper, Z. A. (2003). Primary Cell Wall Composition of Bryophytes and Charophytes. Annals of Botany, 91(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Pushkareva, E., Pessi, I. S., Namsaraev, Z., Mano, M.-J., Elster, J., & Wilmotte, A. (2018). Cyanobacteria inhabiting biological soil crusts of a polar desert: Sør Rondane Mountains, Antarctica. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 41(4), 363–373. [CrossRef]

- Pushkareva, E., Elster, J., Holzinger, A., Niedzwiedz, S., & Becker, B. (2022). Biocrusts from Iceland and Svalbard: Does microbial community composition differ substantially? Frontiers in Microbiology 13, 1048522. [CrossRef]

- Pushkareva, E., Elster, J., Kudoh, S., Imura, S., & Becker, B. (2024). Microbial community composition of terrestrial habitats in East Antarctica with a focus on microphototrophs. Frontiers in Microbiology 14. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F., & De Philippis, R. (2015). Role of Cyanobacterial Exopolysaccharides in Phototrophic Biofilms and in Complex Microbial Mats. Life, 5(2), 1218–1238. [CrossRef]

- Victoria, F. de C., & Pereira, A. B. (2009). Composition and distribution of moss formations in the ice-free areas adjoining the Arctowski region, Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Antarctica. 64(1).

- Walshaw, C. V., Gray, A., Fretwell, P. T., Convey, P., Davey, M. P., Johnson, J. S., & Colesie, C. (2024). A satellite-derived baseline of photosynthetic life across Antarctica. Nature Geoscience, 17(8), 755–762. [CrossRef]

- Woltyńska, A., Gawor, J., Olech, M. A., Górniak, D., & Grzesiak, J. (2023). Bacterial communities of Antarctic lichens explored by gDNA and cDNA 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 99(3). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Xiao, Y., Song, Q., & Li, Z. (2025). Antarctic ice-free terrestrial microbial functional redundancy in core ecological functions and microhabitat-specific microbial taxa and adaptive strategy. Environmental Microbiome, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Wang, N., & Yu, L. (2021). Host-speci city of moss-associated fungal communities in the Ny-Ålesund region (Svalbard, High Arctic) as revealed by amplicon pyrosequencing. Fungal Ecology.

- Zumsteg, A., Luster, J., Göransson, H., Smittenberg, R. H., Brunner, I., Bernasconi, S. M., Zeyer, J., & Frey, B. (2012). Bacterial, Archaeal and Fungal Succession in the Forefield of a Receding Glacier. Microbial Ecology, 63(3), 552–564. [CrossRef]

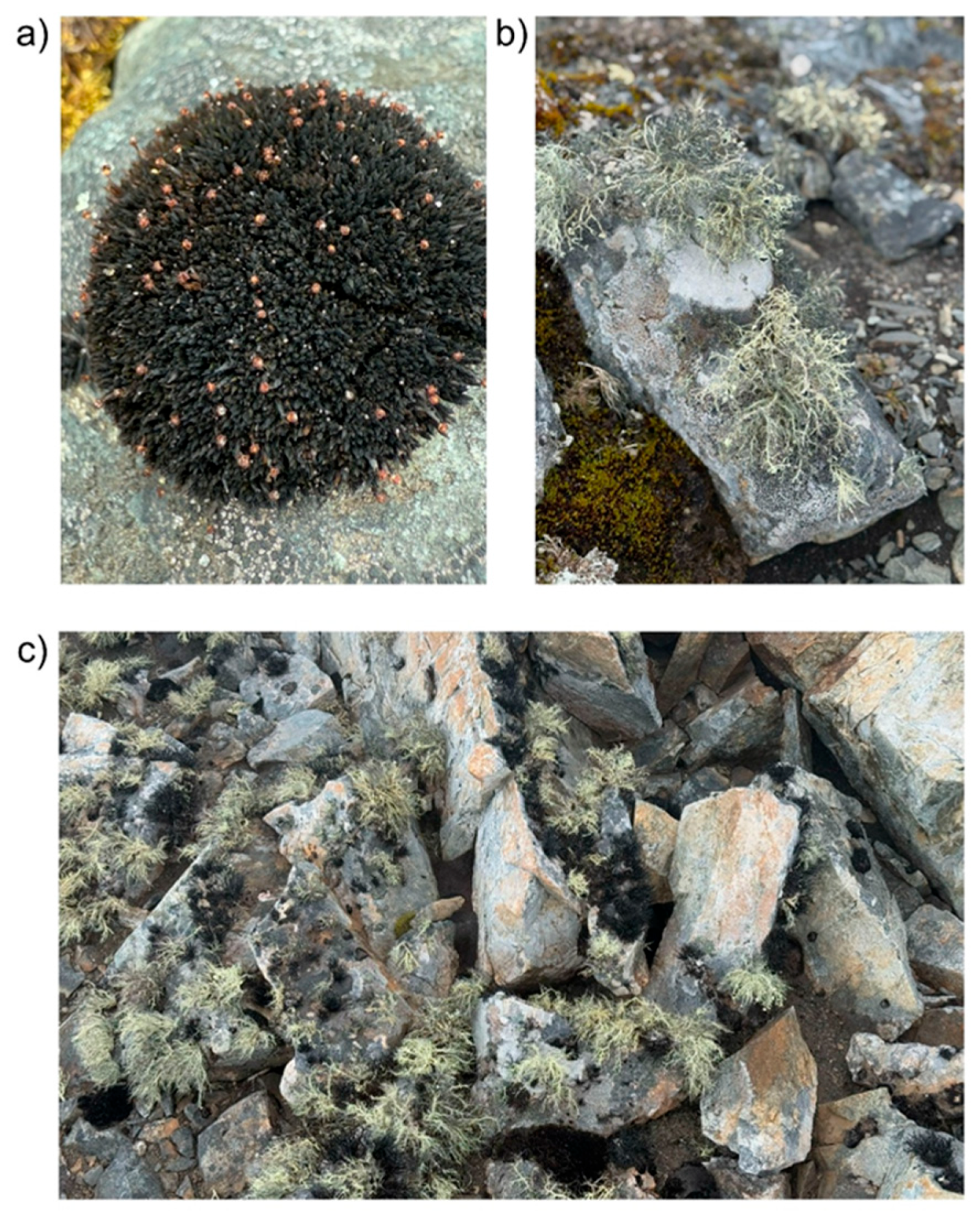

Figure 1.

Representative images of (a) moss Andreaea regularis and (b) lichen Usnea aurantiacoatra collected from Livingston Island and (c) their co-occurrence.

Figure 1.

Representative images of (a) moss Andreaea regularis and (b) lichen Usnea aurantiacoatra collected from Livingston Island and (c) their co-occurrence.

Figure 2.

Maximum likelihood (ML) tree of (a) Andreaea and (b) Usnea species resulting from the IQ-TREE analysis of a concatenated chloroplast gene (a) and nuclear gene (b) alignments. Maximum likelihood bootstrap values are shown above or below branches. Branches with support ≥ 95% are considered highly supported.

Figure 2.

Maximum likelihood (ML) tree of (a) Andreaea and (b) Usnea species resulting from the IQ-TREE analysis of a concatenated chloroplast gene (a) and nuclear gene (b) alignments. Maximum likelihood bootstrap values are shown above or below branches. Branches with support ≥ 95% are considered highly supported.

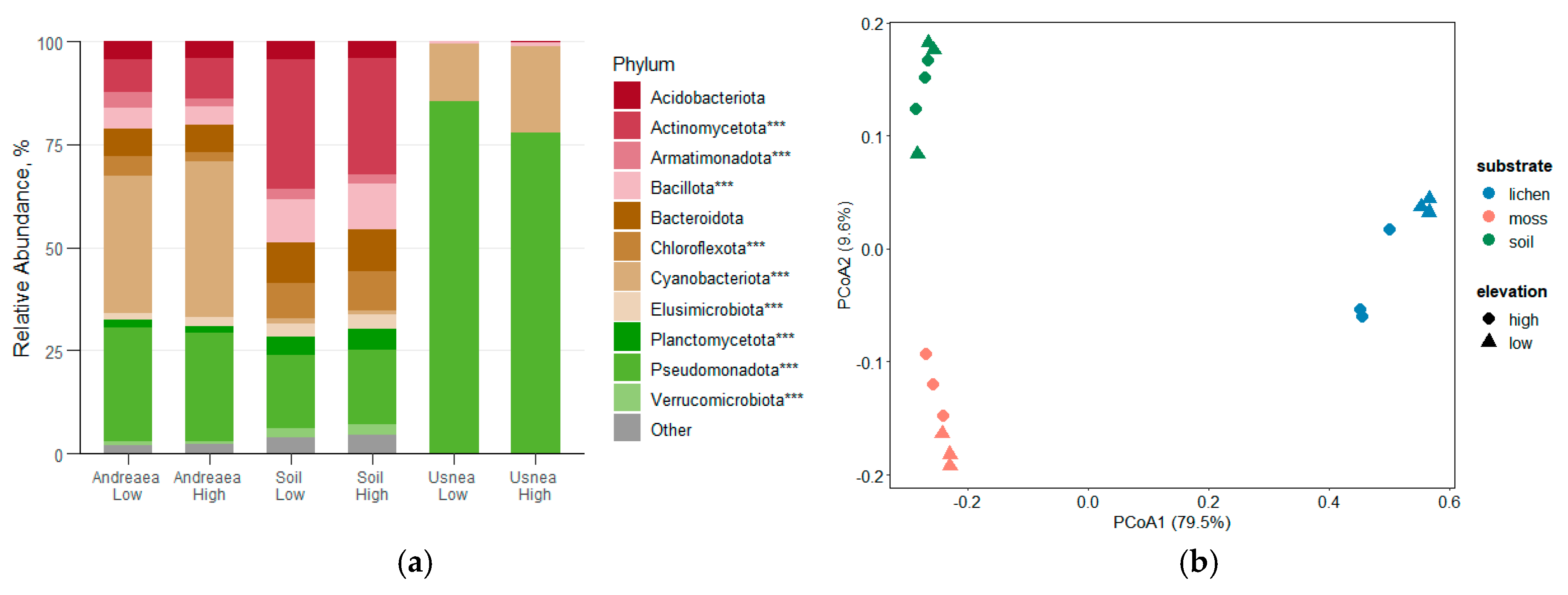

Figure 3.

(a) Relative abundance of bacterial phyla across A. regularis, soil, and U. aurantiacoatra samples collected at low and high elevations on Livingston Island, Antarctica. Taxonomic groups with a total relative abundance below 0.5% are grouped as ‘Other’. Asterisks indicate significant differences between sample types based on one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001). (b) Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of bacterial community composition among moss, lichen and soil samples, based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities.

Figure 3.

(a) Relative abundance of bacterial phyla across A. regularis, soil, and U. aurantiacoatra samples collected at low and high elevations on Livingston Island, Antarctica. Taxonomic groups with a total relative abundance below 0.5% are grouped as ‘Other’. Asterisks indicate significant differences between sample types based on one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001). (b) Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of bacterial community composition among moss, lichen and soil samples, based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities.

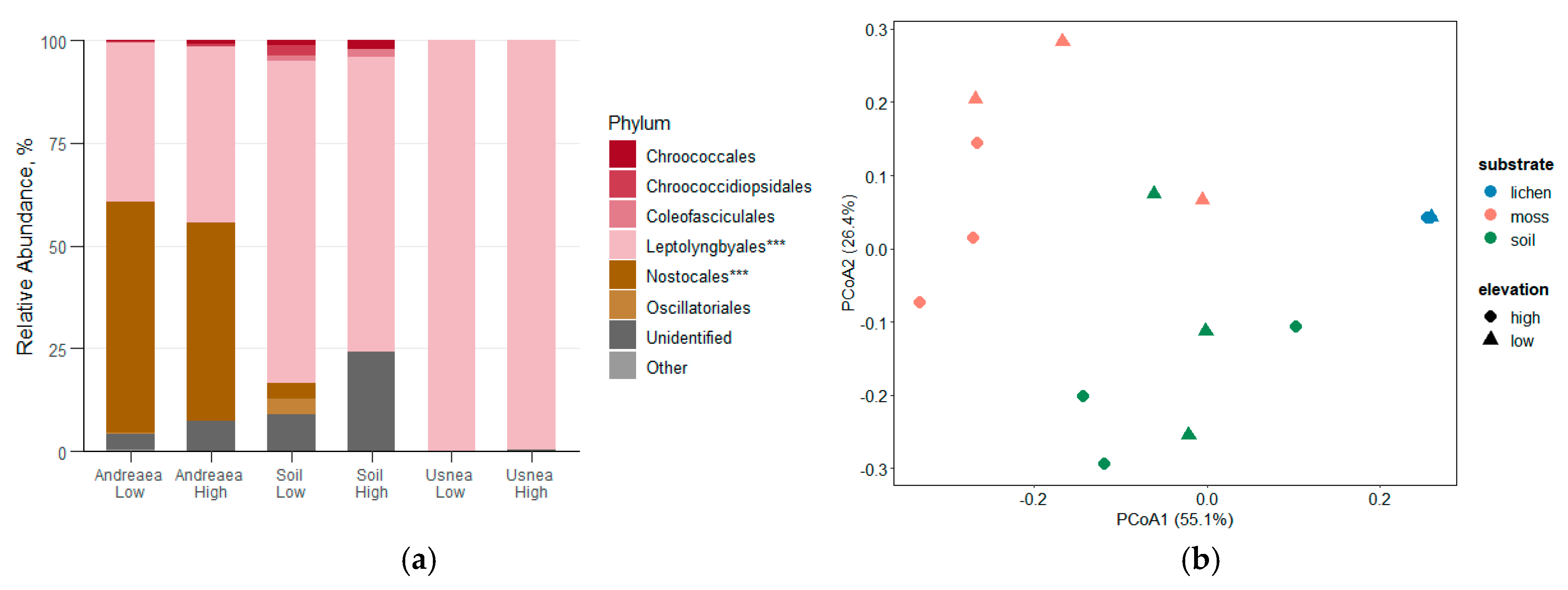

Figure 4.

(a) Relative abundance of cyanobacterial orders across A. regularis, soil, and U. aurantiacoatra samples collected at low and high elevations on Livingston Island, Antarctica. Taxonomic groups with a total relative abundance below 0.5% are grouped as ‘Other’. Asterisks indicate significant differences between sample types based on one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001). (b) Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of cyanobacterial community composition among moss, lichen and soil samples, based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities.

Figure 4.

(a) Relative abundance of cyanobacterial orders across A. regularis, soil, and U. aurantiacoatra samples collected at low and high elevations on Livingston Island, Antarctica. Taxonomic groups with a total relative abundance below 0.5% are grouped as ‘Other’. Asterisks indicate significant differences between sample types based on one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001). (b) Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of cyanobacterial community composition among moss, lichen and soil samples, based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities.

Figure 5.

Overview of functional metagenomic differences among A. regularis, U. aurantiacoatra and soil. (a) Venn diagram showing the overlap of KEGG pathways shared among the three microbiomes. (b) Pairwise comparison of functional profiles based on EggNOG and PfamScan annotations. Numbers within circles indicate the number of genes at low (upper) and high (lower) elevations; arrows show the direction of functional overrepresentation.

Figure 5.

Overview of functional metagenomic differences among A. regularis, U. aurantiacoatra and soil. (a) Venn diagram showing the overlap of KEGG pathways shared among the three microbiomes. (b) Pairwise comparison of functional profiles based on EggNOG and PfamScan annotations. Numbers within circles indicate the number of genes at low (upper) and high (lower) elevations; arrows show the direction of functional overrepresentation.

Figure 6.

Potential nitrogen cycle in bacterial communities associated with A. regularis , U. aurantiacoatra, and soil. Dark and light blue indicate enzymes present and absent in the metagenomic assemblies, respectively.

Figure 6.

Potential nitrogen cycle in bacterial communities associated with A. regularis , U. aurantiacoatra, and soil. Dark and light blue indicate enzymes present and absent in the metagenomic assemblies, respectively.

Figure 7.

Sulfate metabolism in bacterial communities associated with A. regularis , U. aurantiacoatra, and soil. The assimilatory sulfate reduction pathway is represented by straight arrows, while curved arrows indicate dissimilatory sulfate reduction and sulfide oxidation pathways. Dark and light blue indicate enzymes present and absent in the metagenomic assemblies, respectively.

Figure 7.

Sulfate metabolism in bacterial communities associated with A. regularis , U. aurantiacoatra, and soil. The assimilatory sulfate reduction pathway is represented by straight arrows, while curved arrows indicate dissimilatory sulfate reduction and sulfide oxidation pathways. Dark and light blue indicate enzymes present and absent in the metagenomic assemblies, respectively.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).