Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

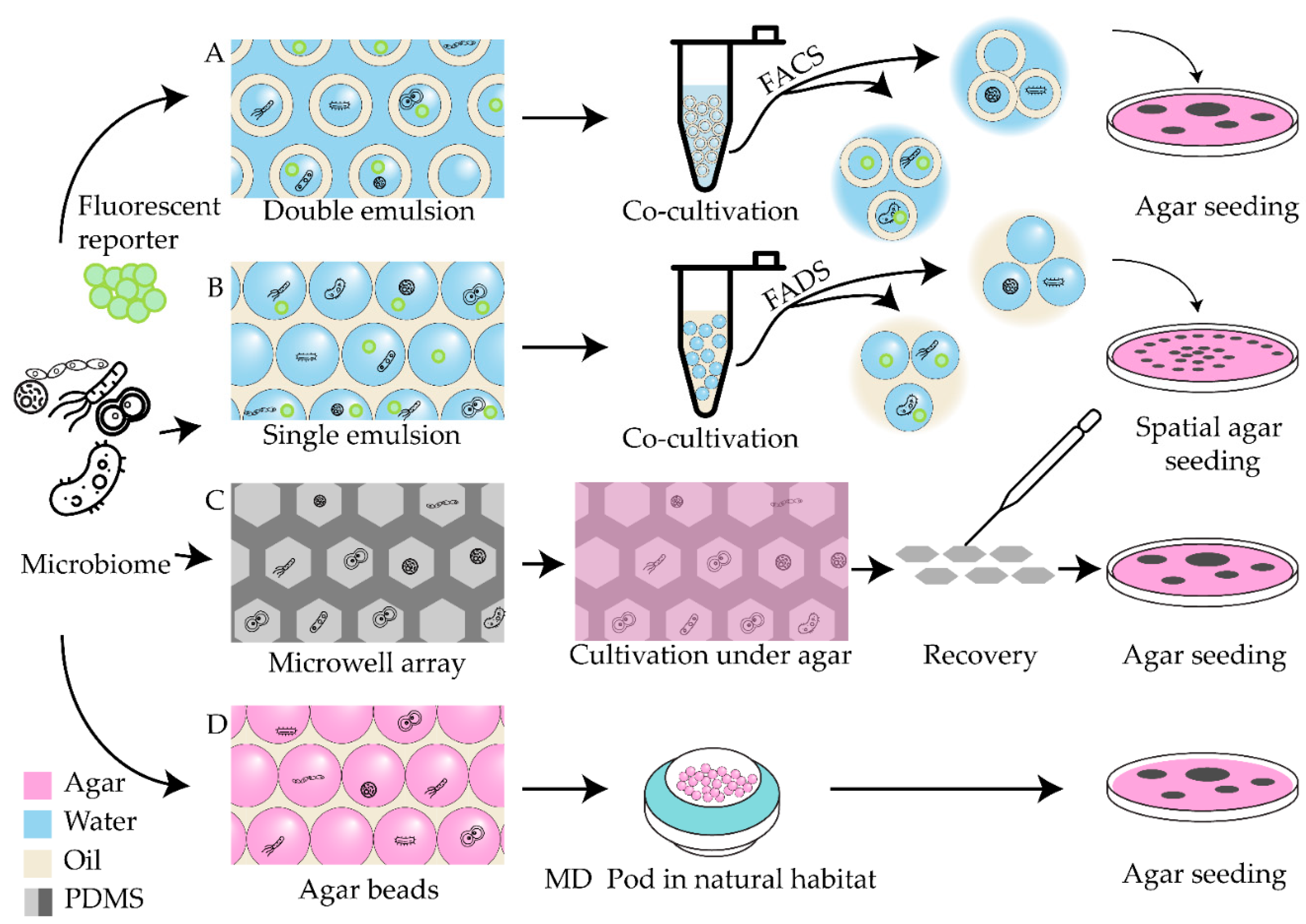

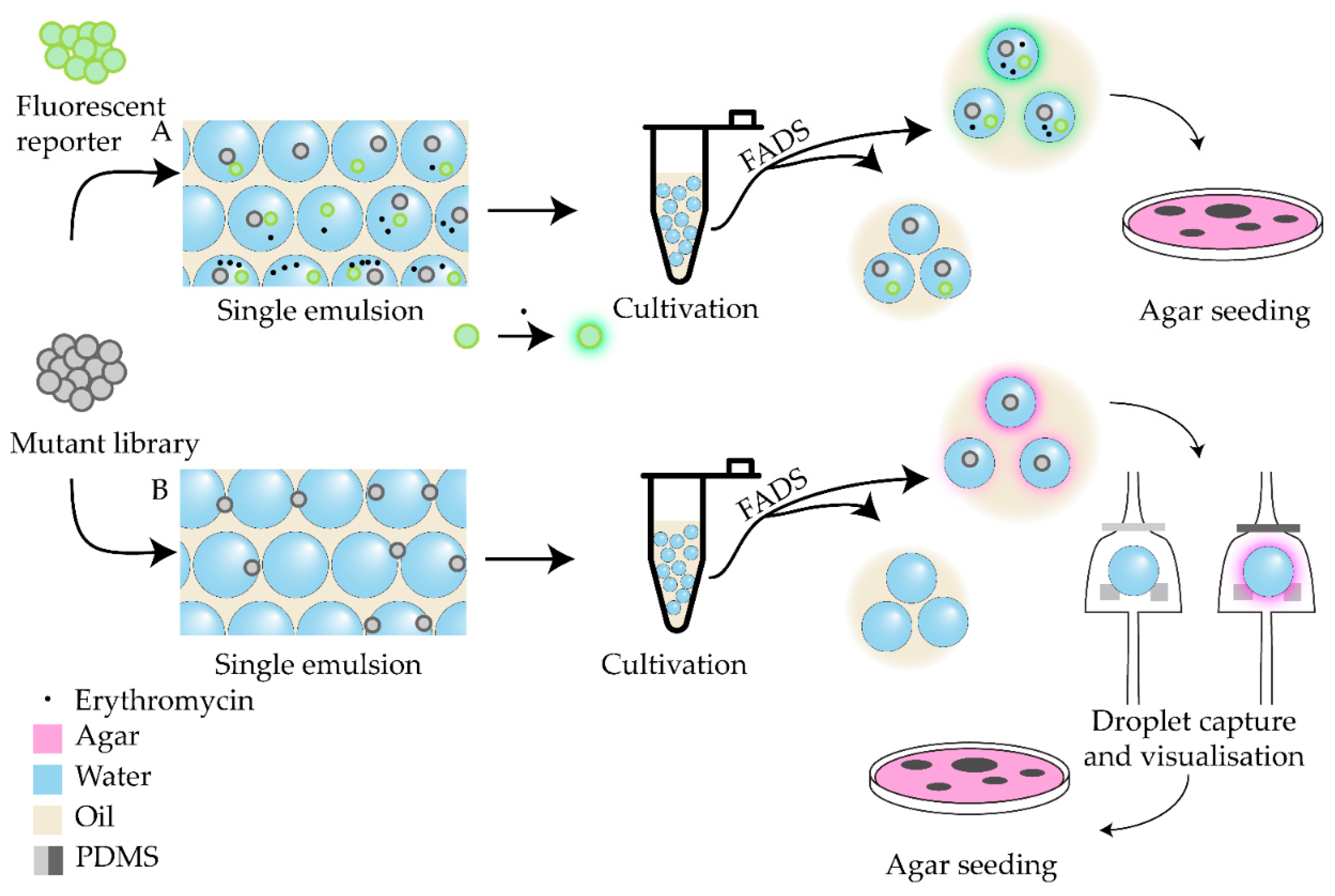

2. Producing Strains: Discovery and Cultivation

3. Antibiotics: Screening and Mechanism Elucidation

3.1. Advances in Screening Approaches

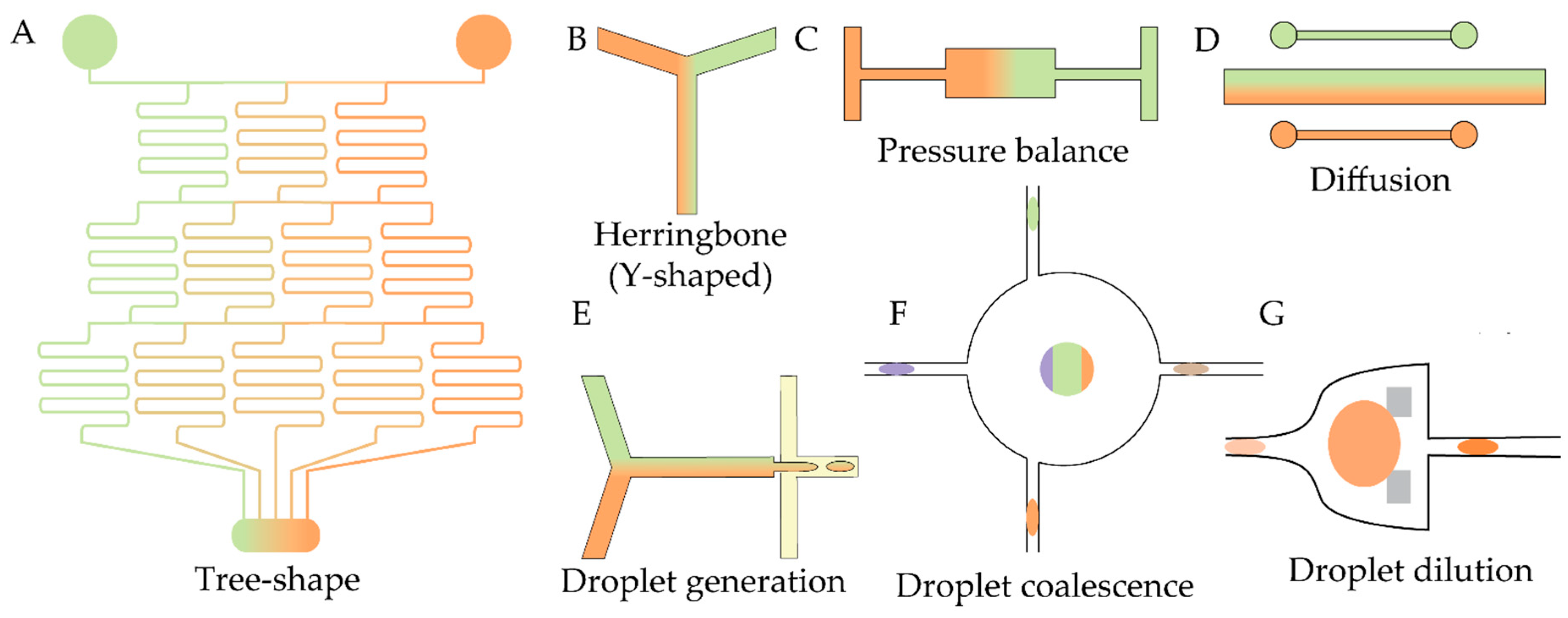

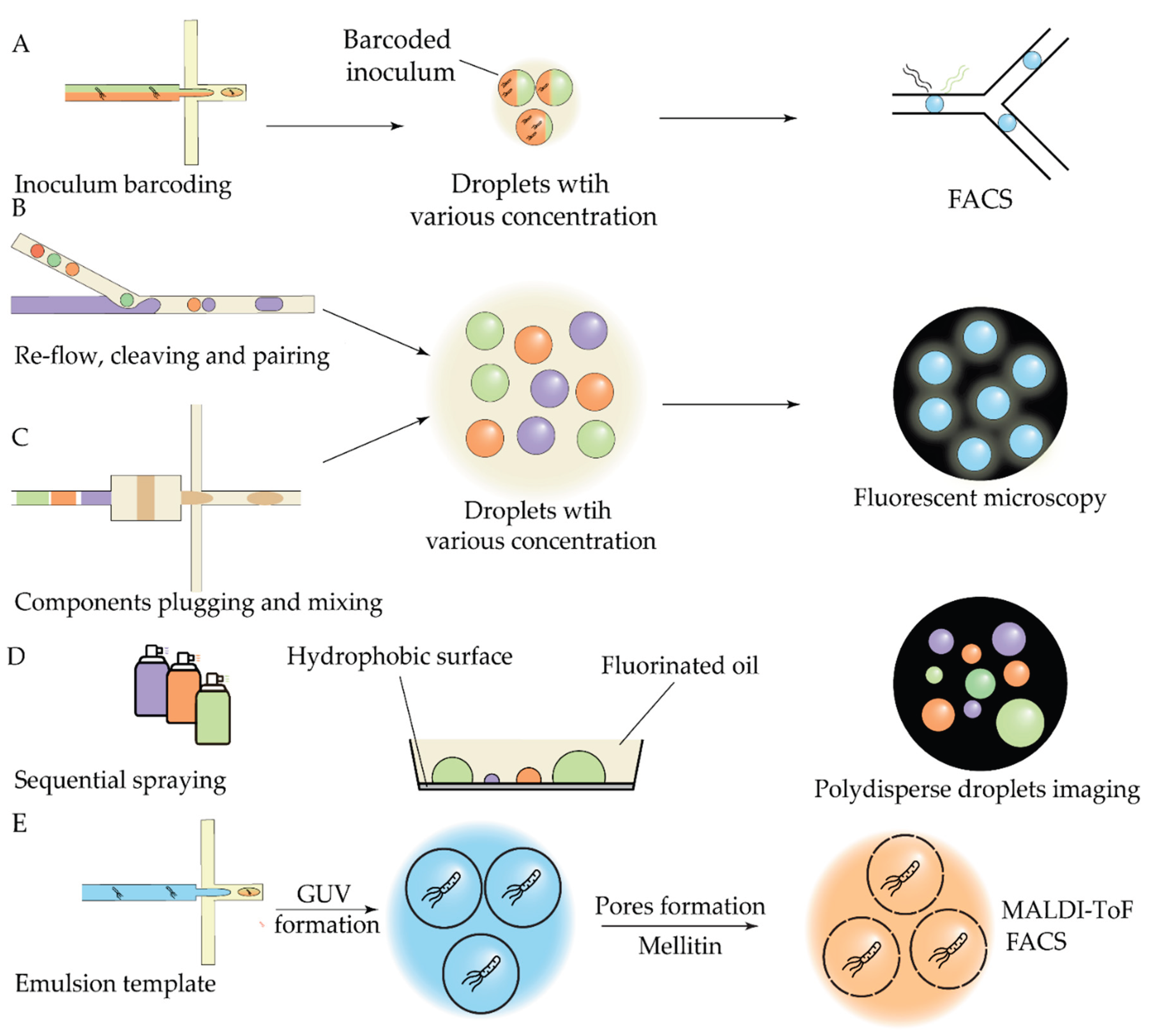

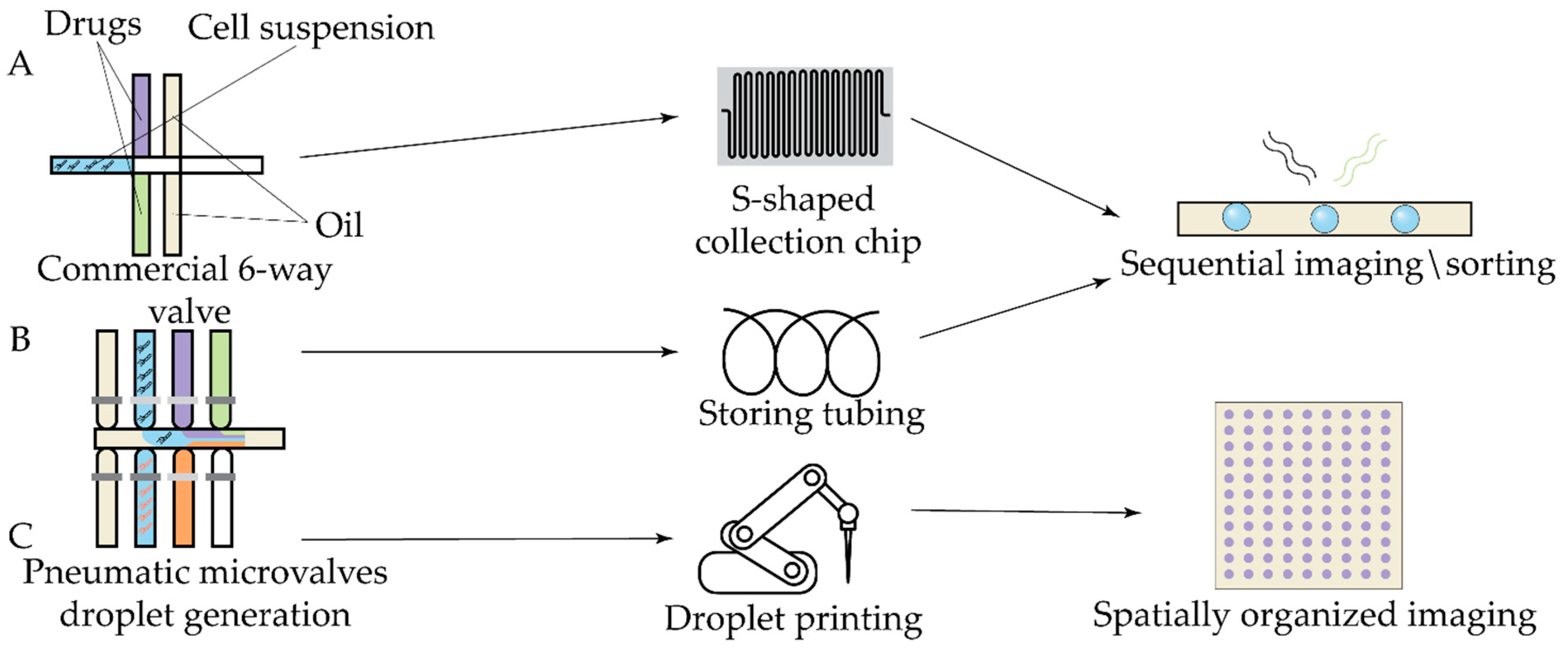

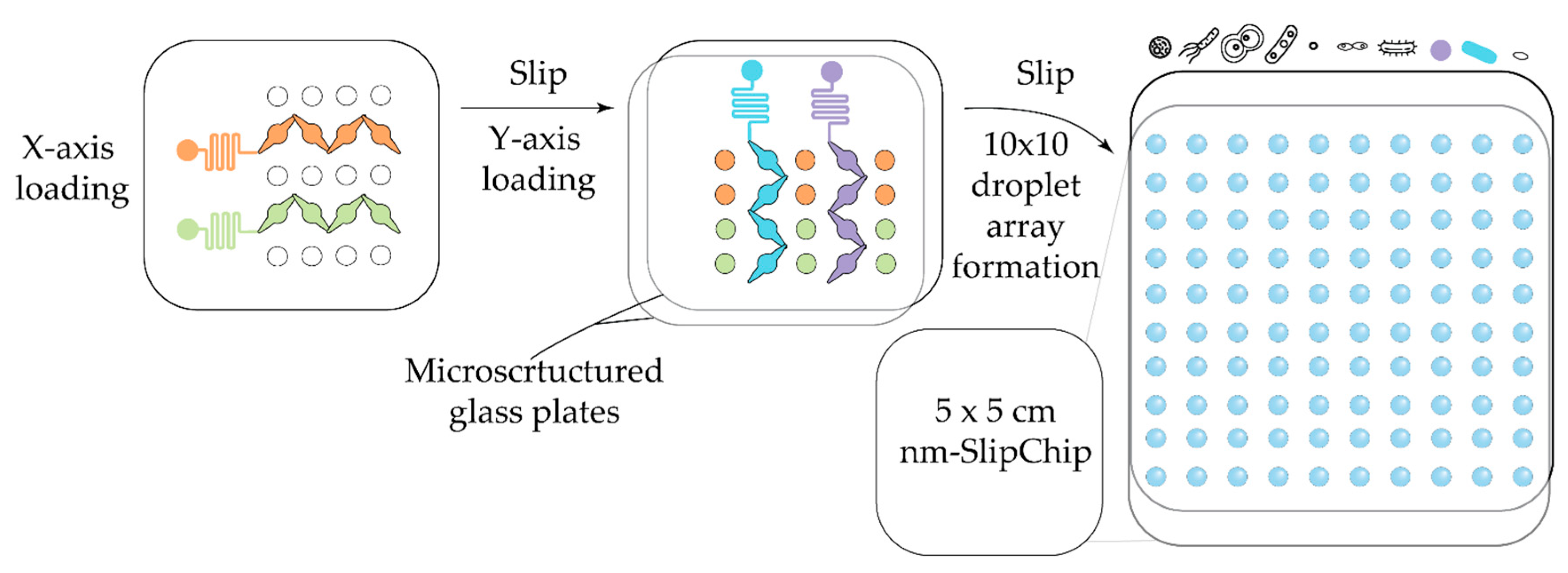

3.1.1. Screening of Chemicals and Their Combinations

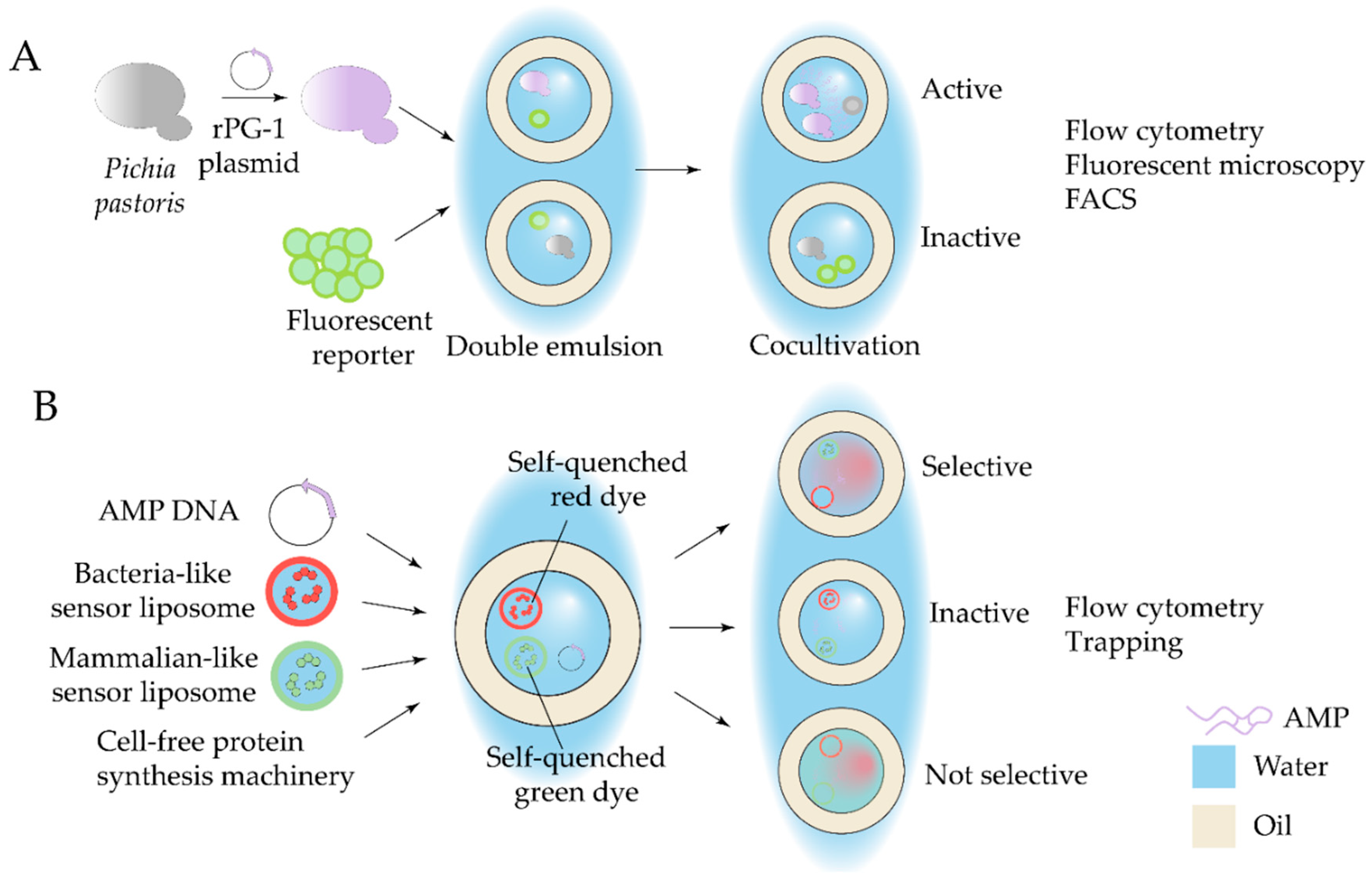

3.1.2. Screening of DNA-Encoded Antimicrobials

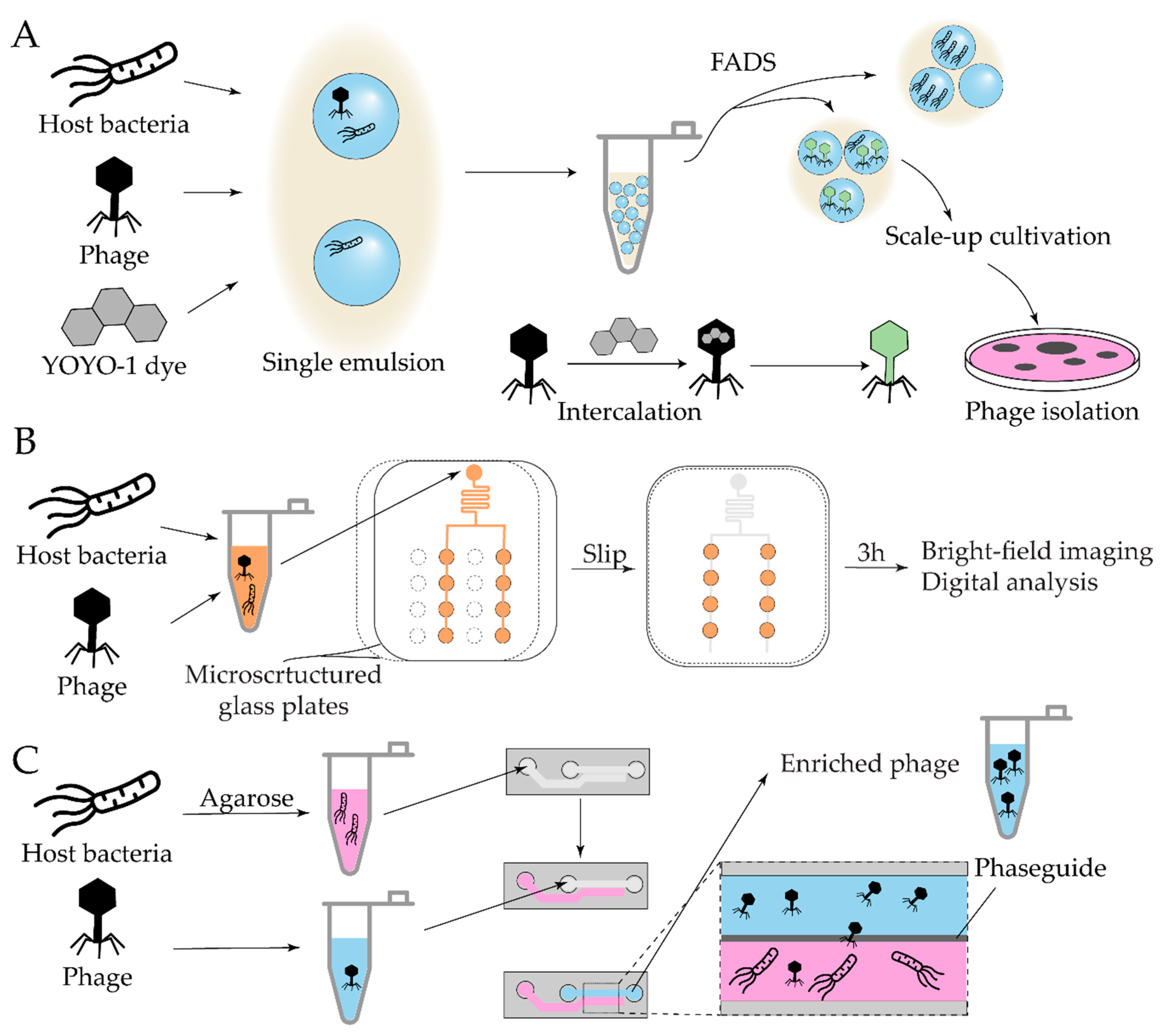

3.1.3. Bacteriophage Evaluation and Development

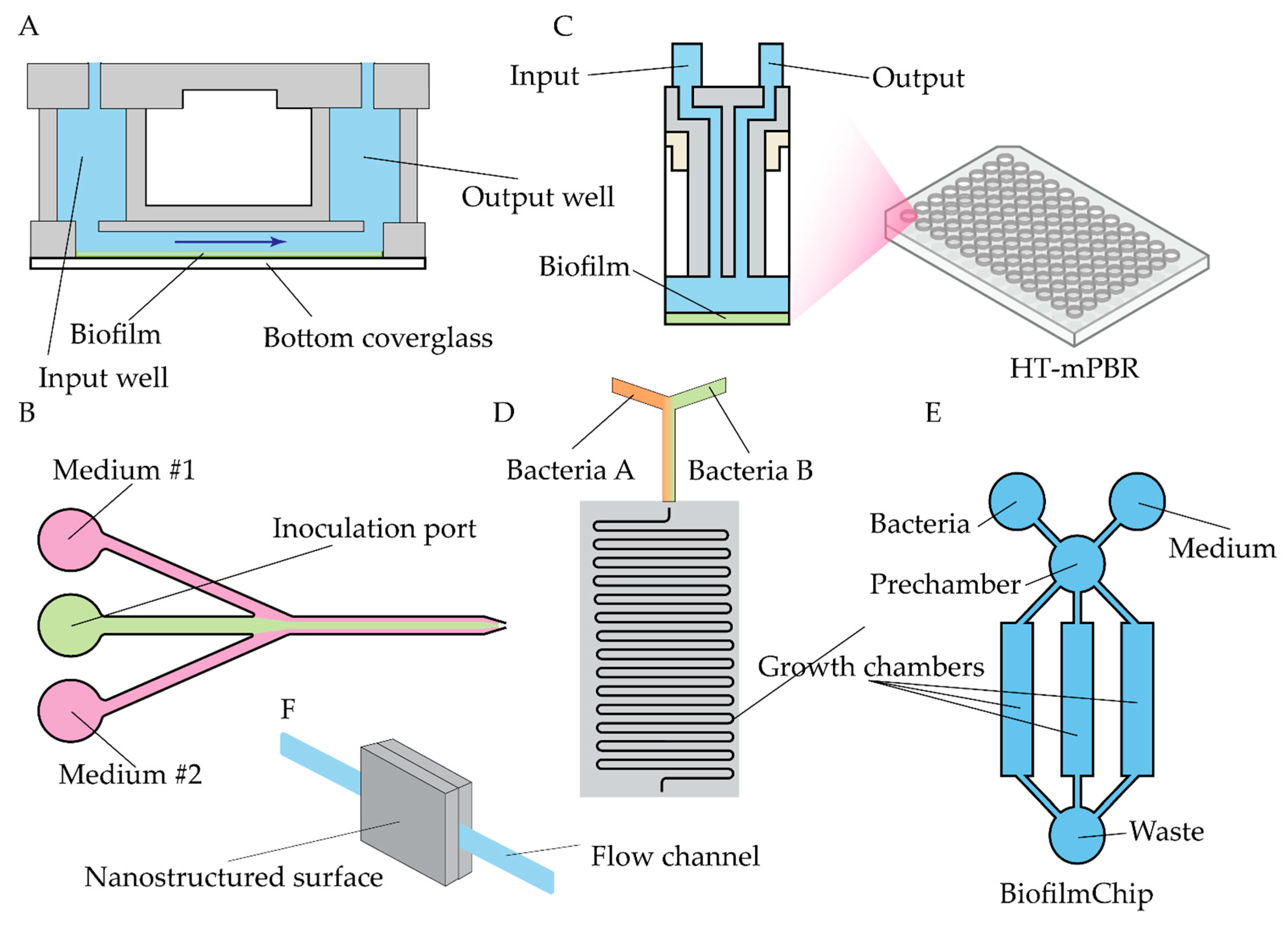

3.1.4. Antibiofilm Activity Testing

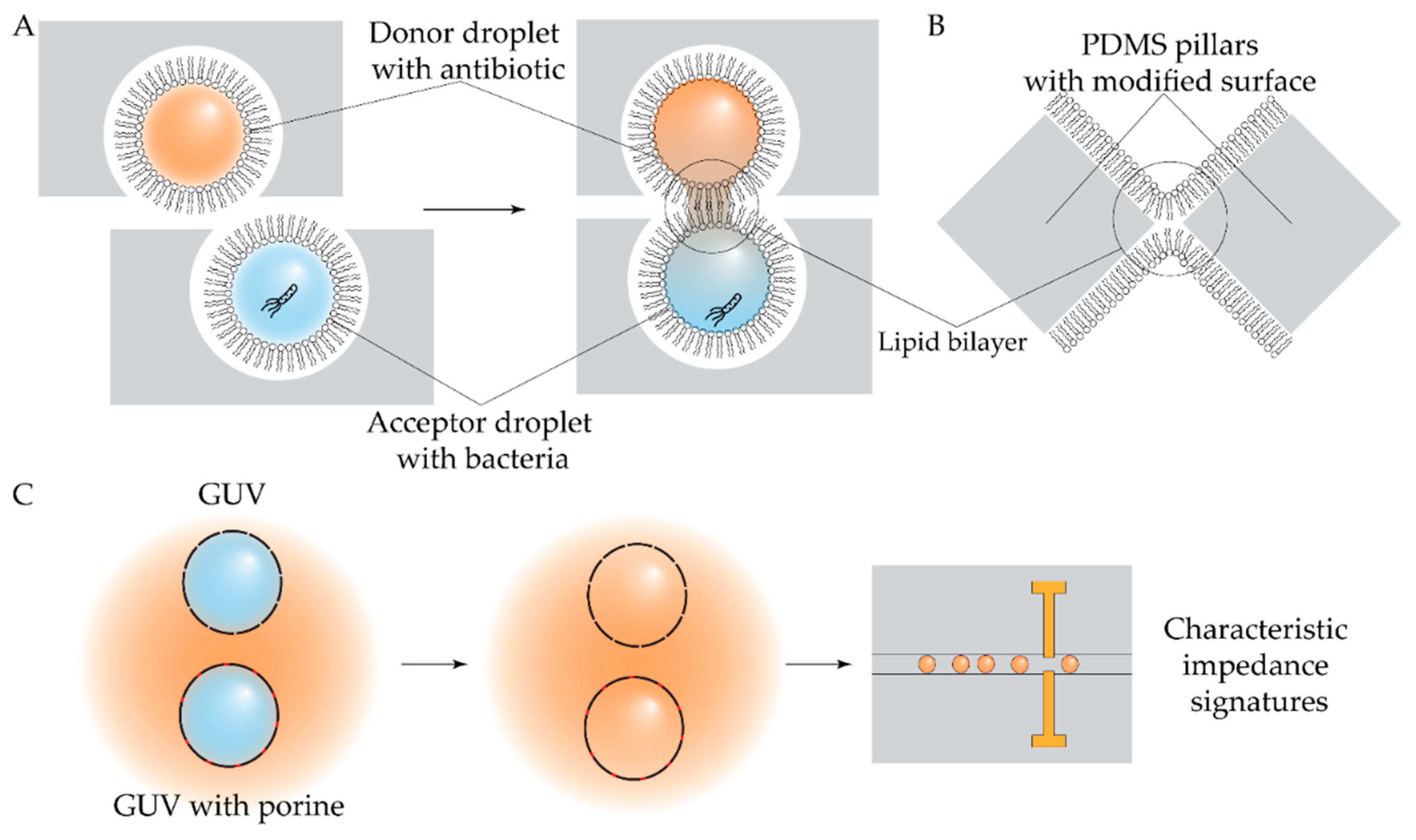

3.2. Studies on Antibiotics Mode of Action

| Compound | Label | Device | Detection method | Test strain | Observed effect | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrashort peptides | Live/Dead stain |

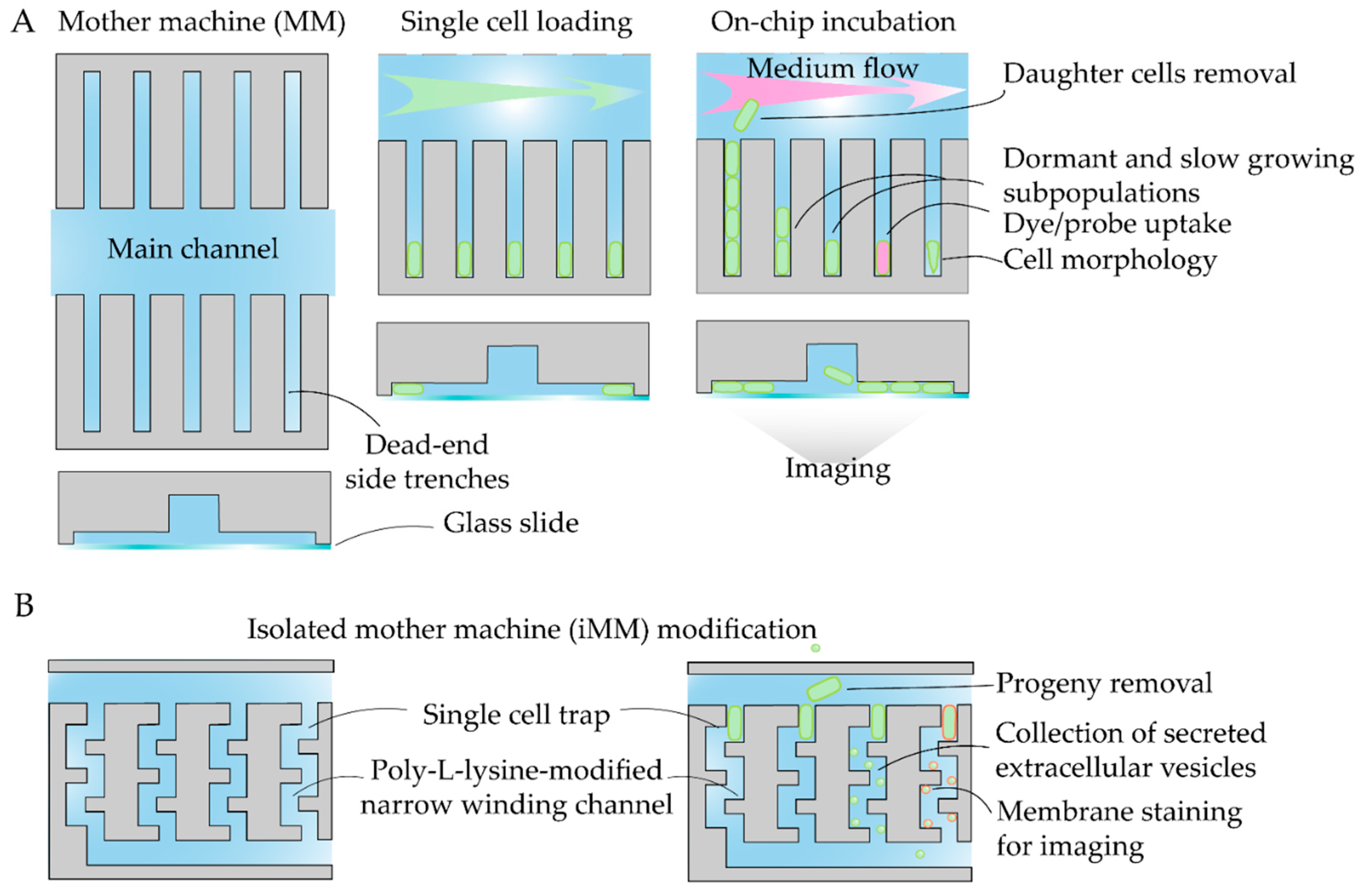

Figure 10 MM |

Fluorescent imaging | Е. Coli | Variable single cell killing kinetics | [152] |

| Roxithromycin | Labelled antibiotic |

Figure 10 MM |

Fluorescent imaging | E.coli, expressing phage secretin f1pIV | Drug uptake | [153] |

| Ofloxacin | Antibiotic natural fluorescence |

Figure 10 MM |

Epifluorescent imaging | Е. Coli | Drug uptake | [154] |

| Polymyxin | GFP, membrane stain |

Figure 10B iMM |

Fluorescent imaging | Е. Coli | Extracellular vesicles secretion | [147] |

| protein capsids | - |

Figure 10A MM |

Bright-field microscopy | Е. Coli | Variable single cell killing kinetics | [155] |

| Proof-of principle study | Labelled vancomycin |

Figure 10A MM |

Fluorescent imaging | Е. Coli | Outer membrane damage by probe uptake | [156] |

| Polymixin | - | Figure 10B | Bright-field microscopy | Е. Coli | L-forms morphology and proliferation | [148] |

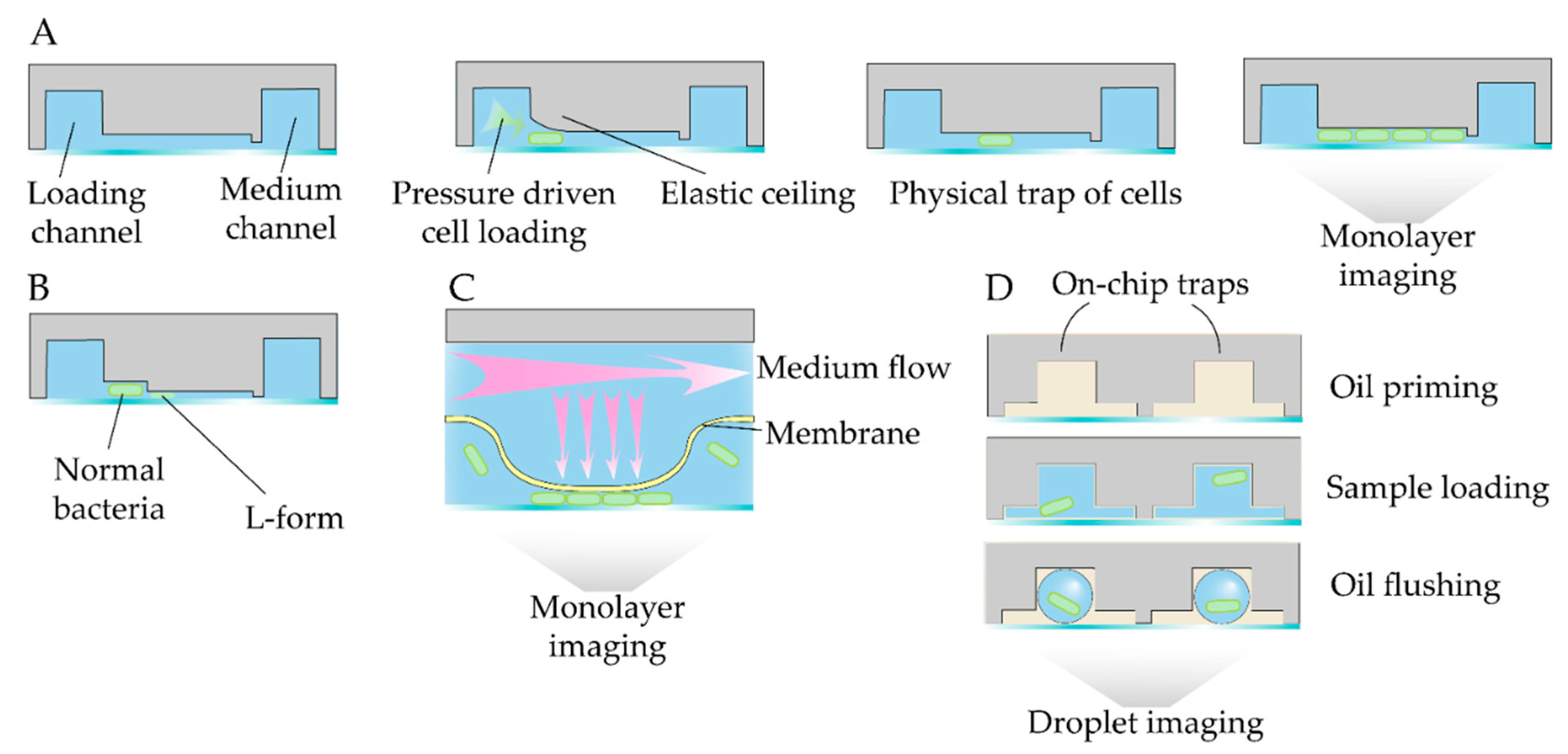

| Aminoglycosides and fluoruquinolones | GFP, mCherry | Figure 11A | Fluorescent imaging | Е. Coli with genetic compartment markers | Hyperosmotic shock, cytoplasmic condesation | [157] |

| Meropenem, berberine | Live/Dead stain | Figure 11A | Bright-field and fluorescent microscopy | A. baumannii | Single-cell growth kinetic under combination therapy | [158] |

| Listeriolysin S | GFP, Sytox blue | Figure 11A | Fluorescent imaging | Listeria monocytogenes | Contact-killing by producing strain | [159] |

| Moxifloxacin | GFP, PI | Figure 11C | Bright-field microscopy | M. smegmatis | Single-cell dose response | [160] |

| M06 pheno-tuning compound | mCherry, GFP | Figure 11C | Fluorescent imaging | M. smegmatis | Single-cell phenotypes | [149] |

| Phages | GFP | Figure 11D | Fluorescent imaging | Е. Coli | Growth and lysis kinetics | [150] |

| Ciprofloxacin | mRFP | Figure 11D | Fluorescent imaging | Е. Coli | Growth kinetic | [151] |

4. Pathogens: Stress Responses and Resistance Development

4.1. Genetic Resistance

4.2. Phenotypic Resistance and Bacterial Stress Responses

| Antibiotic | Device | Detection method | Studied strains | Observed effect | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin Ciprofloxacin |

MCMA | Microscopy | E. coli | Pre- and post-exposure imaging of individual cells | [175] |

| Ampicillin |

Figure 10A MM |

Microscopy | E.coli, expressing pHluorin | Intracellular pH in individual cells | [185] |

| Ampicillin |

Figure 10A MM |

Microscopy | Е. Coli, expressing iATPSnFr1.0 | ATP levels in individual cells | [177] |

| Trimetoprim Linezolid Ciprofloxacin Roxithromycin Vancomycin Polymyxin Octapeptin Tachyplesin |

Figure 10A MM |

Microscopy |

E. coli P. aeruginosa Burkholderia cenocepacia S. aureus |

Accumulation of fluorescent antibiotic derivative | [179] |

| Chloramphenicol |

Figure 10A MM |

Microscopy | E.coli | Growth kinetics after resistance gene deletion | [182] |

| Chloroamphenicol Gentamycin Spectinomycin Tetracyclin Rifampicin Ciprofloxacin Nirtofurantoin Carbenicillin Ceftriaxone |

Figure 10A MM |

Microscopy | E.coli | Growth response under antibiotic treatment | [180] |

| Nafcillin Oxacillin |

Figure 10A MM |

Microscopy | E.coli with AbcA transporter overexpression | Individual cells growth rate | [184] |

| Tachyplesin (AMP) |

Figure 10A MM |

Microscopy |

E.coli P. aeruginosa |

Fluorescent antibiotic uptake | [183] |

| Ampicillin |

Figure 10A MM |

Microscopy | E.coli | Growth kinetic under antibiotic treatment | [178] |

| Flucloxacillin | Figure 11A | Microscopy |

Salmonella S. aureus |

Single-cell growth and regrowth kinetic | [174] |

| Kanamycin | Figure 11A | Microscopy | B. subtilis | Single-cell growth kinetic, fluorescent antibiotic uptake | [176] |

| Cefotaxime | Droplet (W/O) |

Microscopy | E.coli, expressing β-lactamases | Susceptibility distribution | [188] |

| Isoniazid | Acoustic trap |

Raman spectroscopy | M. smegmatis | Single-cell metabolic response by Raman fingerprint | [186] |

| Ampicillin | Figure 11A | Microscopy | E. coli | Indirect monitoring of plasmid copy number | [181] |

| Ceftriaxone | HV-coupled channel |

Mass-spectrometry | E. coli | Metabolic response to antibiotic treatment | [187] |

4.3. Chemotaxis and Bacterial Motility

4.4. Biofilms Antibiotic Susceptibility

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zafar, A.; Takeda, C.; Manzoor, A.; Tanaka, D.; Kobayashi, M.; Wadayama, Y.; Nakane, D.; Majeed, A.; Iqbal, M.A.; Akitsu, T. Towards Industrially Important Applications of Enhanced Organic Reactions by Microfluidic Systems. Molecules 2024, 29, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Min, K.-I.; Inoue, K.; Im, D.J.; Kim, D.-P.; Yoshida, J. Submillisecond Organic Synthesis: Outpacing Fries Rearrangement through Microfluidic Rapid Mixing. Science 2016, 352, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimondi, S.; Ferreira, H.; Reis, R.L.; Neves, N.M. Microfluidic Devices: A Tool for Nanoparticle Synthesis and Performance Evaluation. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 14205–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.M.; Carthy, E.; Dunne, N.; Kinahan, D. Advances in Nanoparticle Synthesis Assisted by Microfluidics. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 3060–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Shang, L.; Zhao, Y. Microfluidics for Drug Development: From Synthesis to Evaluation. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 7468–7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvira, K.S. Microfluidic Technologies for Drug Discovery and Development: Friend or Foe? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2021, 42, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Du, H.; Huang, L.; Xie, W.; Liu, K.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Pan, H. AI-Powered Microfluidics: Shaping the Future of Phenotypic Drug Discovery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 38832–38851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S.E.; Alharthi, S.; Alavi, S.F.; Alavi, S.Z.; Zahra, G.E.; Raza, A.; Ebrahimi Shahmabadi, H. Microfluidics for Personalized Drug Delivery. Drug Discovery Today 2024, 29, 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Wu, J.; Duan, S.; Jin, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, A. Droplet-Based Microfluidics for Drug Delivery Applications. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 663, 124551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.S.; Hooshmand, N.; El-Sayed, M.; Labouta, H.I. Microfluidics for Development of Lipid Nanoparticles: Paving the Way for Nucleic Acids to the Clinic. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 3566–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Oh, D.; Cheng, M.; Chintapula, U.; Liu, S.; Reynolds, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, X.; Ko, J. Enhancing Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Generation via Microfluidic Mechanoporation and Lipid Nanoparticles. Small 2025, 21, 2410975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liu, D.; Shah, P.; Qiu, B.; Mathew, A.; Yao, L.; Guan, T.; Cong, H.; Zhang, N. Optimizing Microfluidic Channel Design with Tilted Rectangular Baffles for Enhanced mRNA-Lipid Nanoparticle Preparation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 3762–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardoost, A.; Karimi, K.; Govindaraju, H.; Jamali, P.; Javanmard, M. Applications of Microfluidics in mRNA Vaccine Development: A Review. Biomicrofluidics 2024, 18, 061502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G.R.; Lone, F.A.; Dalal, J. Microfluidics—A Novel Technique for High-quality Sperm Selection for Greater ART Outcomes. FASEB BioAdvances 2024, 6, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouloorchi Tabalvandani, M.; Saeidpour, Z.; Habibi, Z.; Javadizadeh, S.; Firoozabadi, S.A.; Badieirostami, M. Microfluidics as an Emerging Paradigm for Assisted Reproductive Technology: A Sperm Separation Perspective. Biomed Microdevices 2024, 26, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, C.; Shang, L. Microfluidics-Based Microcarriers for Live-Cell Delivery. Advanced Science 2025, 12, 2414410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Lim, H.; Chung, A.J. Expanding CAR-T Cell Immunotherapy Horizons through Microfluidics. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 1088–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Di Carlo, D.; Lim, C.T.; Zhou, T.; Tian, G.; Tang, T.; Shen, A.Q.; Li, W.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; et al. Passive Microfluidic Devices for Cell Separation. Biotechnology Advances 2024, 71, 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Shi, Y.; Song, Q.; Wei, Z.; Dun, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, C.-W.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, X. Optical Sorting: Past, Present and Future. Light Sci Appl 2025, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, P.; Hefner, C.; Martinez, B.; Henry, C.S. Microfluidics in Environmental Analysis: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Prospects for Rapid and Efficient Monitoring. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 1175–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwi-Dantsis, L.; Jayarajan, V.; Church, G.M.; Kamm, R.D.; De Magalhães, J.P.; Moeendarbary, E. Aging on Chip: Harnessing the Potential of Microfluidic Technologies in Aging and Rejuvenation Research. Adv Healthcare Materials 2025, 14, 2500217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafadar, A.; Takallu, S.; Alashti, S.K.; Rashidi, S.; Bahrani, S.; Tajbakhsh, A.; Mirzaei, E.; Savardashtaki, A. Advancements in Microfluidic Platforms for Rapid Biomarker Diagnostics of Infectious Diseases. Microchemical Journal 2025, 208, 112296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Pandey, V.K.; Singh, A.; Dash, K.K.; Dar, A.H.; Rustagi, S. Recent Insights on Microfluidics Applications for Food Quality and Safety Analysis: A Comprehensive Review. Food Control 2025, 168, 110869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Guo, L.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X. Emerging Biosensors Integrated with Microfluidic Devices: A Promising Analytical Tool for on-Site Detection of Mycotoxins. npj Sci Food 2025, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhwama, M.; Mpofu, K.; Sivarasu, S.; Mthunzi-Kufa, P. Applications of Microfluidics in Biosensing. Discov Appl Sci 2024, 6, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, L.; Zambry, N.S.; Ibrahim, F.B.; Petrović, B.; Kojić, S.; Thiha, A.; Joseph, K.; Jamaluddin, N.F.; Stojanović, G.M. Advances in Textile-Based Microfluidics for Biomolecule Sensing. Biomicrofluidics 2024, 18, 051502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Roman, R.; Mosig, A.S.; Figge, M.T.; Papenfort, K.; Eggeling, C.; Schacher, F.H.; Hube, B.; Gresnigt, M.S. Organ-on-Chip Models for Infectious Disease Research. Nat Microbiol 2024, 9, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Kim, Y.S.; Ponce-Arias, A.-I.; O’Laughlin, R.; Yan, R.Z.; Kobayashi, N.; Tshuva, R.Y.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Sun, S.; Zheng, Y.; et al. A Patterned Human Neural Tube Model Using Microfluidic Gradients. Nature 2024, 628, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Guo, K.; Chen, Y.; Xiang, N. Droplet Microfluidics for Current Cancer Research: From Single-Cell Analysis to 3D Cell Culture. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 1335–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuwatfa, W.H.; Pitt, W.G.; Husseini, G.A. Scaffold-Based 3D Cell Culture Models in Cancer Research. J Biomed Sci 2024, 31, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xu, X. Droplet Microfluidics for Advanced Single-Cell Analysis. Smart Medicine 2025, 4, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauwynck, W.; Faust, K.; Boon, N. Droplet Microfluidics for Single-Cell Studies: A Frontier in Ecological Understanding of Microbiomes. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2025, 49, fuaf032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, A.; Aranda Palomer, M.; Esteves, M.; Rodrigues, C.; Fernandes, J.M.; Oliveira, F.; Teixeira, A.; Honrado, C.; Dieguez, L.; Abalde-Cela, S.; et al. Advanced Microfluidics for Single Cell-Based Cancer Research. Advanced Science 2025, e00975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheem, H.B.; Kim, N.; Nguyen, D.T.; Baskoro, G.A.; Roh, J.H.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, B.J.; Choi, I.S. Single-Cell Nanoencapsulation: Chemical Synthesis of Artificial Cell-in-Shell Spores. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 6366–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.D.; Lao, J.; Zhao, X.; Milcic, K.; Weitz, D.A. Ultrahigh-Throughput Multiplexed Screening of Purified Protein from Cell-Free Expression Using Droplet Microfluidics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 28758–28772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.M.; Knowles, T.P.J.; Keller, S.; Krainer, G. Microfluidics for Protein Interaction Studies: Current Methods, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Eur Biophys J 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J.; Flach, C.-F. Antibiotic Resistance in the Environment. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, E.M.; Trampari, E.; Siasat, P.; Gaya, M.S.; Alav, I.; Webber, M.A.; Blair, J.M.A. Molecular Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance Revisited. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Barkhouse, A.; Hackenberger, D.; Wright, G.D. Antibiotic Resistance: A Key Microbial Survival Mechanism That Threatens Public Health. Cell Host & Microbe 2024, 32, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüssow, H. The Antibiotic Resistance Crisis and the Development of New Antibiotics. Microbial Biotechnology 2024, 17, e14510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Huang, Y.; Xu, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, L.; Hu, B.; Zhang, T. Global Soil Antibiotic Resistance Genes Are Associated with Increasing Risk and Connectivity to Human Resistome. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potenza, L.; Krzak, J.; Andrzejewski, M.; Pyzik, A.; Kaminski, T.S. Ultra-High Throughput Droplet Microfluidics for Cultivation and Functional Screening of Environmental Microbial Strains and Consortia. 2025.

- Hinojosa-Ventura, G.; Acosta-Cuevas, J.M.; Velázquez-Carriles, C.A.; Navarro-López, D.E.; López-Alvarez, M.Á.; Ortega-de La Rosa, N.D.; Silva-Jara, J.M. From Basic to Breakthroughs: The Journey of Microfluidic Devices in Hydrogel Droplet Generation. Gels 2025, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, T.N.D.; Do, H.D.K.; Nam, N.N.; Dan, T.T.; Trinh, K.T.L.; Lee, N.Y. Droplet-Based Microfluidics: Applications in Pharmaceuticals. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moragues, T.; Arguijo, D.; Beneyton, T.; Modavi, C.; Simutis, K.; Abate, A.R.; Baret, J.-C.; deMello, A.J.; Densmore, D.; Griffiths, A.D. Droplet-Based Microfluidics. Nat Rev Methods Primers 2023, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, R.; Jia, Y. Droplet-Based Microfluidics in Single-Bacterium Analysis: Advancements in Cultivation, Detection, and Application. Biosensors 2025, 15, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergola, A.; Ballesio, A.; Frascella, F.; Napione, L.; Cocuzza, M.; Marasso, S.L. Droplet Generation and Manipulation in Microfluidics: A Comprehensive Overview of Passive and Active Strategies. Biosensors 2025, 15, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivan, S.; Pradeep, S.; Ramachandran, J.C.; Narayan, J.; Gęca, M.J. Advances in Droplet Microfluidics: A Comprehensive Review of Innovations, Morphology, Dynamics, and Applications. Microfluid Nanofluid 2025, 29, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yin, J.; Huang, W.E.; Li, B.; Yin, H. Emerging Single-Cell Microfluidic Technology for Microbiology. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 170, 117444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripandelli, R.A.A.; Van Oijen, A.M.; Robinson, A. Single-Cell Microfluidics: A Primer for Microbiologists. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 10311–10328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Shen, Q.; Chen, Z.; He, Z.; Yan, X. Harnessing Microfluidic Technology for Bacterial Single-Cell Analysis in Mammals. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2023, 166, 117168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Qiao, L. Microfluidics Coupled Mass Spectrometry for Single Cell Multi-Omics. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2301179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, J.; Tyski, S.; Laudy, A.E. In Vitro Resistance-Predicting Studies and In Vitro Resistance-Related Parameters—A Hit-to-Lead Perspective. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

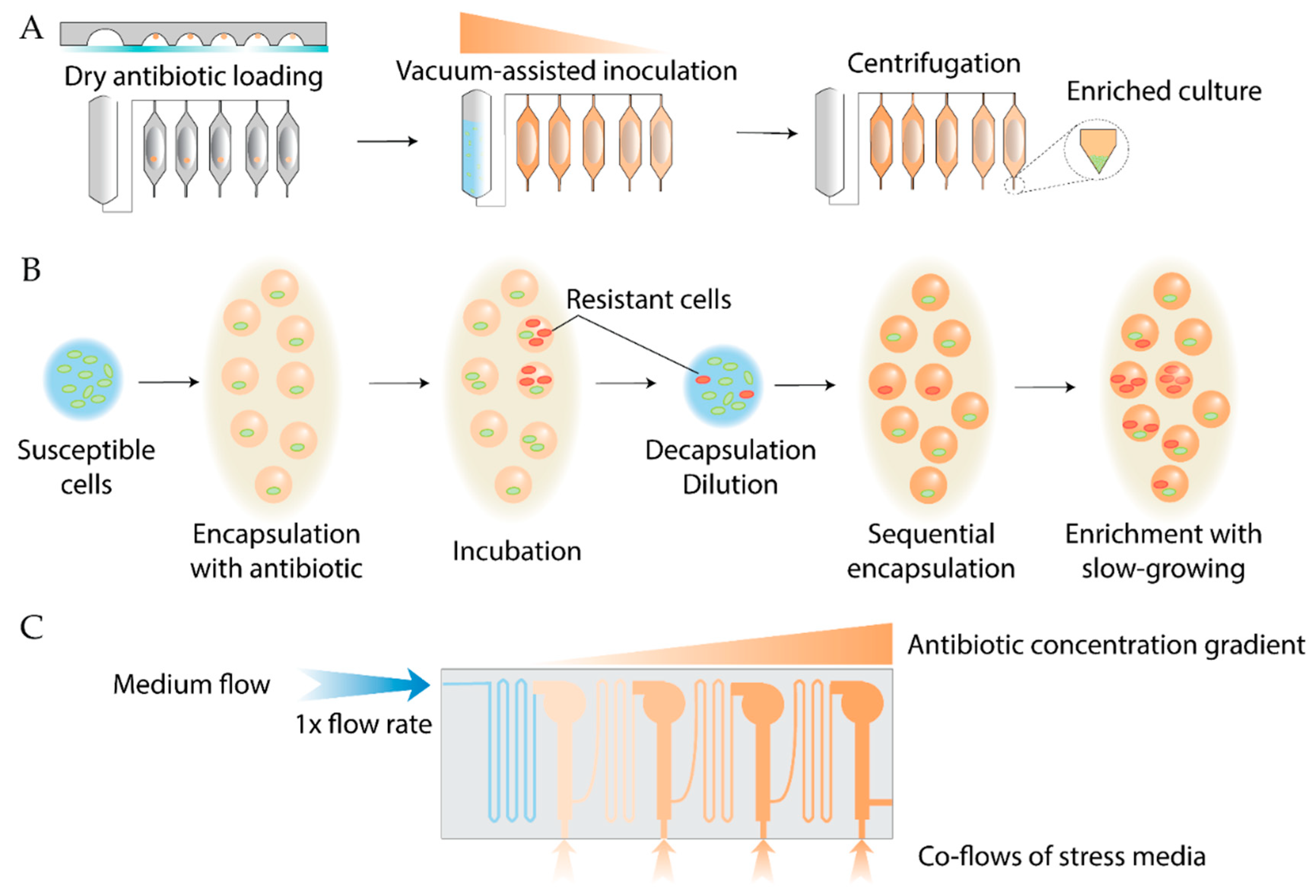

- Zoheir, A.E.; Stolle, C.; Rabe, K.S. Microfluidics for Adaptation of Microorganisms to Stress: Design and Application. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 108, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Lv, S.; Zhu, C. Bacterial Patterning: A Promising Biofabrication Technique. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 8008–8018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, H.; Liu, J.; Xin, F.; Chen, M.; Dong, W.; Qian, X.; Jiang, M. Insights into Constructing a Stable and Efficient Microbial Consortium System. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering 2024, 76, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoloudaki, O.; Aheto, F.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M. Synthetic Microbial Communities: A Gateway to Understanding Resistance, Resilience, and Functionality in Spontaneously Fermented Food Microbiomes. Food Research International 2024, 192, 114780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo-Navarro, O.; Aguilar-Salinas, B.; Rocha, J.; Olmedo-Álvarez, G. Higher-Order Interactions and Emergent Properties of Microbial Communities: The Power of Synthetic Ecology. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, X.; Nuhu, M.; Candry, P.; Wolfanger, J.; Betenbaugh, M.; Saldivar, A.; Zuniga, C.; Wang, Y.; Shrestha, S. Top-down and Bottom-up Microbiome Engineering Approaches to Enable Biomanufacturing from Waste Biomass. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2024, 51, kuae025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Ju, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W. Strategies and Tools to Construct Stable and Efficient Artificial Coculture Systems as Biosynthetic Platforms for Biomass Conversion. Biotechnol Biofuels 2024, 17, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouhagger, A.; Celiešiūtė-Germanienė, R.; Bakute, N.; Stirke, A.; Melo, W.C.M.A. Electrochemical Biosensors on Microfluidic Chips as Promising Tools to Study Microbial Biofilms: A Review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1419570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Yang, Z.; Singh, B.; Ma, B.; Lu, Z.; Xu, J.; He, Y. Discussion: Embracing Microfluidics to Advance Environmental Science and Technology. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 937, 173597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugolini, G.S.; Wang, M.; Secchi, E.; Pioli, R.; Ackermann, M.; Stocker, R. Microfluidic Approaches in Microbial Ecology. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 1394–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, J.M.; Johnson, L.Y.D.; Robinson, A.J.; Longley, R.; Hanson, B.T.; Cailleau, G.; Bindschedler, S.; Junier, P.; Chain, P.S.G. Fabricated Devices for Performing Bacterial-Fungal Interaction Experiments across Scales. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1380199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diep Trinh, T.N.; Trinh, K.T.L.; Lee, N.Y. Microfluidic Advances in Food Safety Control. Food Research International 2024, 176, 113799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbaran, M.; Verma, M.S. Microfluidics at the Interface of Bacteria and Fresh Produce. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 128, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Dou, M.; Zhuo, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Li, J. Advances in Microfluidic Analysis of Residual Antibiotics in Food. Food Control 2022, 136, 108885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, E.A.; De Mesy Bentley, K.L.; Gill, A.L.; Hao, S.P.; Galloway, C.A.; Salminen, A.T.; Guy, D.R.; McGrath, J.L.; Awad, H.A.; Gill, S.R.; et al. Identification of Penicillin Binding Protein 4 (PBP4) as a Critical Factor for Staphylococcus Aureus Bone Invasion during Osteomyelitis in Mice. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, e1008988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terekhov, S.S.; Smirnov, I.V.; Stepanova, A.V.; Bobik, T.V.; Mokrushina, Y.A.; Ponomarenko, N.A.; Belogurov, A.A.; Rubtsova, M.P.; Kartseva, O.V.; Gomzikova, M.O.; et al. Microfluidic Droplet Platform for Ultrahigh-Throughput Single-Cell Screening of Biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 2550–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranova, M.N.; Babikova, P.A.; Kudzhaev, A.M.; Mokrushina, Y.A.; Belozerova, O.A.; Yunin, M.A.; Kovalchuk, S.; Gabibov, A.G.; Smirnov, I.V.; Terekhov, S.S. Live Biosensors for Ultrahigh-Throughput Screening of Antimicrobial Activity against Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terekhov, S.S.; Nazarov, A.S.; Mokrushina, Y.A.; Baranova, M.N.; Potapova, N.A.; Malakhova, M.V.; Ilina, E.N.; Smirnov, I.V.; Gabibov, A.G. Deep Functional Profiling Facilitates the Evaluation of the Antibacterial Potential of the Antibiotic Amicoumacin. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranova, M.N.; Kudzhaev, A.M.; Mokrushina, Y.A.; Babenko, V.V.; Kornienko, M.A.; Malakhova, M.V.; Yudin, V.G.; Rubtsova, M.P.; Zalevsky, A.; Belozerova, O.A.; et al. Deep Functional Profiling of Wild Animal Microbiomes Reveals Probiotic Bacillus Pumilus Strains with a Common Biosynthetic Fingerprint. IJMS 2022, 23, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranova, M.N.; Soboleva, E.A.; Kornienko, M.A.; Malakhova, M.V.; Mokrushina, Yu.A.; Gabibov, A.G.; Terekhov, S.S.; Smirnov, I.V. Bacteriocin from the Raccoon Dog Oral Microbiota Inhibits the Growth of Pathogenic Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Acta Naturae 2024, 16, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCully, A.L.; Loop Yao, M.; Brower, K.K.; Fordyce, P.M.; Spormann, A.M. Double Emulsions as a High-Throughput Enrichment and Isolation Platform for Slower-Growing Microbes. ISME Communications 2023, 3, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, A.; Gastélum, G.; Rocha, J.; Olguin, L.F. High-Throughput Bacterial Co-Encapsulation in Microfluidic Gel Beads for Discovery of Antibiotic-Producing Strains. Analyst 2023, 148, 5762–5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahler, L.; Niehs, S.P.; Martin, K.; Weber, T.; Scherlach, K.; Hertweck, C.; Roth, M.; Rosenbaum, M.A. Highly Parallelized Droplet Cultivation and Prioritization of Antibiotic Producers from Natural Microbial Communities. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Zhang, H.; Hooper, J.; Huang, C.; Gupte, R.; Guzman, A.; Han, J.J.; Han, A. Size-Independent and Automated Single-Colony-Resolution Microdroplet Dispensing. Lab Chip 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Han, X.; Wu, L.; Sun, B.; Li, G. A Digital Plating Platform for Robust and Versatile Microbial Detection and Analysis. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 25301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.L.; Schneider, T.; Peoples, A.J.; Spoering, A.L.; Engels, I.; Conlon, B.P.; Mueller, A.; Schaberle, T.F.; Hughes, D.E.; Epstein, S.; et al. A New Antibiotic Kills Pathogens without Detectable Resistance. Nature 2015, 517, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkayyali, T.; Pope, E.; Wheatley, S.K.; Cartmell, C.; Haltli, B.; Kerr, R.G.; Ahmadi, A. Development of a Microbe Domestication Pod (MD Pod) for in Situ Cultivation of Micro-encapsulated Marine Bacteria. Biotech & Bioengineering 2021, 118, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, S.K.; Cartmell, C.; Madadian, E.; Badr, S.; Haltli, B.A.; Kerr, R.G.; Ahmadi, A. Microfabrication of a Micron-Scale Microbial-Domestication Pod for in Situ Cultivation of Marine Bacteria. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 28123–28127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Gupte, R.; Liu, X.J.A.; Li, Y.; Yang, F.; Chen, S.; Provin, T.; Van Schaik, E.; Samuel, J.E.; et al. Microfluidic Droplets with Amended Culture Media Cultivate a Greater Diversity of Soil Microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol 2025, 91, e01794–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, E.; Zhang, Y.; Yun, K.; Pan, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Tu, R.; Wang, M. Whole-Cell Biosensor and Producer Co-Cultivation-Based Microfludic Platform for Screening Saccharopolyspora Erythraea with Hyper Erythromycin Production. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 2697–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Xue, N.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. Modulating Sensitivity of an Erythromycin Biosensor for Precise High-Throughput Screening of Strains with Different Characteristics. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 1761–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Qi, L.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, H.; Liao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. Biosensor-Based Dual-Color Droplet Microfluidic Platform for Precise High-Throughput Screening of Erythromycin Hyperproducers. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2025, 278, 117376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, B.; Li, G.; Zhou, L.; Guo, Y.; Tu, Q.; Wang, J. On-Chip Screening of Chemically Induced Mutant Strains and Assay of Their Metabolites by Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2021, 348, 130655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Pang, Y. Concentration Gradient Generation Methods Based on Microfluidic Systems. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 29966–29984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Niu, Y.; Pang, L.; Wang, J. Construction of Multiple Concentration Gradients for Single-Cell Level Drug Screening. Microsyst Nanoeng 2023, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Tao, C.; Dai, B.; Zhang, D.; Yamaguchi, Y. High-Throughput 3D Microfluidic Chip for Generation of Concentration Gradients and Mixture Combinations. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 2280–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, M.; Davaji, B.; Nguyen, A.V.; Mokhtare, A.; Zhang, S.; Dogan, B.; Gibney, P.A.; Simpson, K.W.; Abbaspourrad, A. Biological Small-Molecule Assays Using Gradient-Based Microfluidics. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2021, 178, 113038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, E.; Yang, B.; Chen, J.; Vickerman, R.; Lin, Y.; Long, A.; Jacobs, E.; Wu, T.; Mercier, C.; Jew, R.; et al. 3D Microfluidic Gradient Generator for Combination Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Microsyst Nanoeng 2020, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gong, G.; Hu, W.; Lv, H.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Sun, X. Recent Advances of Concentration Gradient Microfluidic Chips for Drug Screening. BioChip J 2025, 19, 496–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Qin, S.; Wu, S.; Liang, Y.; Li, J. Microfluidic Systems for Rapid Antibiotic Susceptibility Tests (ASTs) at the Single-Cell Level. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 6352–6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietvorst, J.; Vilaplana, L.; Uria, N.; Marco, M.-P.; Muñoz-Berbel, X. Current and Near-Future Technologies for Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Resistant Bacteria Detection. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2020, 127, 115891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.N.D.; Lee, N.Y. Nucleic Acid Amplification-Based Microfluidic Approaches for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Analyst 2021, 146, 3101–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, K.; Mach, K.E.; Zhang, P.; Liao, J.C.; Wang, T.-H. Combating Antimicrobial Resistance via Single-Cell Diagnostic Technologies Powered by Droplet Microfluidics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruszczak, A.; Bartkova, S.; Zapotoczna, M.; Scheler, O.; Garstecki, P. Droplet-Based Methods for Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2022, 76, 102755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postek, W.; Pacocha, N.; Garstecki, P. Microfluidics for Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 3637–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubry, G.; Lee, H.J.; Lu, H. Advances in Microfluidics: Technical Innovations and Applications in Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 444–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardila, C.M.; Jiménez-Arbeláez, G.A.; Vivares-Builes, A.M. The Potential Clinical Applications of a Microfluidic Lab-on-a-Chip for the Identification and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing of Enterococcus Faecalis-Associated Endodontic Infections: A Systematic Review. Dentistry Journal 2023, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehnert, T.; Gijs, M.A.M. Microfluidic Systems for Infectious Disease Diagnostics. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 1441–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fu, Y.; Fong, C.Y.; Hua, H.; Li, W.; Khoo, B.L. Advancements in Microfluidic Technology for Rapid Bacterial Detection and Inflammation-Driven Diseases. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 3348–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabbarov, N.G.; Nikolskaya, E.D.; Bibikov, S.B.; Maltsev, A.A.; Chirkina, M.V.; Mollaeva, M.R.; Sokol, M.B.; Epova, E.Yu.; Aliev, R.O.; Kurochkin, I.N. Methods for Rapid Evaluation of Microbial Antibiotics Resistance. Biochemistry Moscow 2025, 90, S312–S341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed Nawaz Qureshi, Y.Z.; Li, M.; Chang, H.; Song, Y. Microfluidic Chip Systems for Color-Based Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test a Review. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2025, 273, 117160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastmanesh, S.; Zeinaly, I.; Alivirdiloo, V.; Mobed, A.; Darvishi, M. Biosensing for Rapid Detection of MDR, XDR and PDR Bacteria. Clinica Chimica Acta 2025, 567, 120121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, B.; Zeng, X.; Peng, J. Advances in Genotypic Antimicrobialresistance Testing: A Comprehensive Review. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Guzman, A.R.; Wippold, J.A.; Li, Y.; Dai, J.; Huang, C.; Han, A. An Ultra High-Efficiency Droplet Microfluidics Platform Using Automatically Synchronized Droplet Pairing and Merging. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 3948–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, A.; Hengoju, S.; Rosenbaum, M.A. Combinatorial Sample Preparation Platform for Droplet-Based Applications in Microbiology. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2024, 417, 136162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, R.; Cira, N.J. High-Throughput, Combinatorial Droplet Generation by Sequential Spraying. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 1502–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheler, O.; Makuch, K.; Debski, P.R.; Horka, M.; Ruszczak, A.; Pacocha, N.; Sozański, K.; Smolander, O.-P.; Postek, W.; Garstecki, P. Droplet-Based Digital Antibiotic Susceptibility Screen Reveals Single-Cell Clonal Heteroresistance in an Isogenic Bacterial Population. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, W.; Lee, C.-S. Label-Free Single-Cell Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing in Droplets with Concentration Gradient Generation. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 5274–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruszczak, A.; Jankowski, P.; Vasantham, S.K.; Scheler, O.; Garstecki, P. Physicochemical Properties Predict Retention of Antibiotics in Water-in-Oil Droplets. Anal. Chem. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heuberger, L.; Messmer, D.; Dos Santos, E.C.; Scherrer, D.; Lörtscher, E.; Schoenenberger, C.; Palivan, C.G. Microfluidic Giant Polymer Vesicles Equipped with Biopores for High-Throughput Screening of Bacteria. Advanced Science 2024, 11, 2307103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, F.; Hsieh, K.; Zhang, P.; Kaushik, A.M.; Wang, T.-H. Facile and Scalable Tubing-Free Sample Loading for Droplet Microfluidics. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 13340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, M.; Yang, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Huang, L. Artificial Intelligence-Accelerated High-Throughput Screening of Antibiotic Combinations on a Microfluidic Combinatorial Droplet System. Lab Chip 2023, 23, 3961–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, P.; Hsieh, K.; Wang, T.-H. Combinatorial Nanodroplet Platform for Screening Antibiotic Combinations. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, F.; Li, H.; Hsieh, K.; Zhang, P.; Li, S.; Wang, T.-H. Automated and Miniaturized Screening of Antibiotic Combinations via Robotic-Printed Combinatorial Droplet Platform. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2024, 14, 1801–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsley, N.C.; Smythers, A.L.; Hicks, L.M. Implementation of Microfluidics for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assays: Issues and Optimization Requirements. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 547177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Yu, Z.; Lyu, W.; Luo, Y.; Xu, L.; Shen, F. Digital Bioassays on the Slipchip Microfluidic Devices. Advanced Sensor Research 2025, 4, e00030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Lyu, W.; Li, X.; Xu, L.; Qin, Y.; Ren, Y.; Deng, Z.; Tao, M.; Xiao, W.; et al. Rapid High-Throughput Discovery of Molecules With Antimicrobial Activity From Natural Products Enabled by a Nanoliter Matrix SlipChip. Small Methods 2025, 9, 2402045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pipiya, S.O.; Terekhov, S.S.; Mokrushina, Yu.A.; Knorre, V.D.; Smirnov, I.V.; Gabibov, A.G. Engineering Artificial Biodiversity of Lantibiotics to Expand Chemical Space of DNA-Encoded Antibiotics. Biochemistry Moscow 2020, 85, 1319–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipiya, S.O.; Mirzoeva, N.Z.; Baranova, M.N.; Eliseev, I.E.; Mokrushina, Y.A.; Shamova, O.V.; Gabibov, A.G.; Smirnov, I.V.; Terekhov, S.S. Creation of Recombinant Biocontrol Agents by Genetic Programming of Yeast. Acta Naturae 2023, 15, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuti, N.; Rottmann, P.; Stucki, A.; Koch, P.; Panke, S.; Dittrich, P.S. A Multiplexed Cell-Free Assay to Screen for Antimicrobial Peptides in Double Emulsion Droplets. Angew Chem Int Ed 2022, 61, e202114632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmasoumi, F.; Hengoju, S.; Beck, K.; Stephan, P.; Klopfleisch, L.; Hoernke, M.; Rosenbaum, M.A.; Kries, H. Analysing Megasynthetase Mutants at High Throughput Using Droplet Microfluidics**. ChemBioChem 2023, 24, e202300680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, C.; De Ninno, A.; Casciaro, B.; Riccitelli, F.; Park, Y.; Businaro, L.; Massoud, R.; Mangoni, M.L.; Bisegna, P.; Stella, L.; et al. Rapid Assessment of Susceptibility of Bacteria and Erythrocytes to Antimicrobial Peptides by Single-Cell Impedance Cytometry. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 2572–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteleev, V.; Kulbachinskiy, A.; Gelfenbein, D. Evaluating Phage Lytic Activity: From Plaque Assays to Single-Cell Technologies. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1659093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, M.; Ota, Y.; Suyama, T.; Morishita, Y.; Tsuneda, S.; Noda, N. Water-in-Oil Droplet-Mediated Method for Detecting and Isolating Infectious Bacteriophage Particles via Fluorescent Staining. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1282372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Boeckman, J.; Gupte, R.; Prejean, A.; Miller, J.; Rodier, A.; De Figueiredo, P.; Liu, M.; Gill, J.; Han, A. PRISM: A Platform for Illuminating Viral Dark Matter 2025.

- Givelet, L.; Von Schönberg, S.; Katzmeier, F.; Simmel, F.C. Digital Phage Biology in Droplets 2025.

- Li, X.; Hu, Q.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Wu, N.; Shen, F. Rapid Bacteriophage Quantification by Digital Biosensing on a SlipChip Microfluidic Device. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 8632–8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidi Mabrouk, A.; Ongenae, V.; Claessen, D.; Brenzinger, S.; Briegel, A. A Flexible and Efficient Microfluidics Platform for the Characterization and Isolation of Novel Bacteriophages. Appl Environ Microbiol 2023, 89, e01596-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, M.R.; Conant, C.G.; Ionescu-Zanetti, C.; Schwartz, M.; Matin, A. New Device for High-Throughput Viability Screening of Flow Biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010, 76, 4136–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Somma, A.; Recupido, F.; Cirillo, A.; Romano, A.; Romanelli, A.; Caserta, S.; Guido, S.; Duilio, A. Antibiofilm Properties of Temporin-L on Pseudomonas Fluorescens in Static and In-Flow Conditions. IJMS 2020, 21, 8526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Aguilar, M.; Ekkelenkamp, M.; Morosini, M.-I.; Huertas, N.; Del Campo, R.; Zamora, J.; Fluit, A.C.; Tunney, M.M.; Obrecht, D.; Bernardini, F.; et al. Anti-Biofilm Activity of Murepavadin against Cystic Fibrosis Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolates. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2021, 76, 2578–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda-Madej, A.; Kozłowska, J.; Baczyńska, D.; Krzyżek, P. Ether Derivatives of Naringenin and Their Oximes as Factors Modulating Bacterial Adhesion. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowicz, P.; Nowicka, J.; Neubauer, D.; Chodaczek, G.; Krzyżek, P.; Gościniak, G. Activity of Novel Ultrashort Cyclic Lipopeptides against Biofilm of Candida Albicans Isolated from VVC in the Ex Vivo Animal Vaginal Model and BioFlux Biofilm Model—A Pilot Study. IJMS 2022, 23, 14453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladewig, L.; Gloy, L.; Langfeldt, D.; Pinnow, N.; Weiland-Bräuer, N.; Schmitz, R.A. Antimicrobial Peptides Originating from Expression Libraries of Aurelia Aurita and Mnemiopsis Leidyi Prevent Biofilm Formation of Opportunistic Pathogens. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, H.; Eberl, L.; Zinn, M.; Rossi, R.M.; Maniura-Weber, K.; Ren, Q. A Microfluidic Platform for in Situ Investigation of Biofilm Formation and Its Treatment under Controlled Conditions. J Nanobiotechnol 2020, 18, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, D.; Wei, L.; Li, Z. A Standard 96-Well Based High Throughput Microfluidic Perfusion Biofilm Reactor for in Situ Optical Analysis. Biomed Microdevices 2023, 25, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouget, C.; Pantel, A.; Dunyach-Remy, C.; Magnan, C.; Sotto, A.; Lavigne, J.-P. Antimicrobial Activity of Antibiotics on Biofilm Formed by Staphylococcus Aureus and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in an Open Microfluidic Model Mimicking the Diabetic Foot Environment. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2023, 78, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.N.; Khan, F.; Han, W.; Luluil, M.; Truong, V.G.; Yun, H.G.; Choi, S.; Kim, Y.-M.; Shin, J.H.; Kang, H.W. Real-Time Monitoring of Mono- and Dual-Species Biofilm Formation and Eradication Using Microfluidic Platform. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 9678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Cabra, N.; López-Martínez, M.J.; Arévalo-Jaimes, B.V.; Martin-Gómez, M.T.; Samitier, J.; Torrents, E. A New BiofilmChip Device for Testing Biofilm Formation and Antibiotic Susceptibility. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senevirathne, S.W.M.A.I.; Mathew, A.; Toh, Y.-C.; Yarlagadda, P.K.D.V. Bactericidal Efficacy of Nanostructured Surfaces Increases under Flow Conditions. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 41711–41722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, A.; Karlsen, E.A.; Stensen, W.; Svendsen, J.S.M.; Berglin, M.; Lundgren, A. Preventing E. Coli Biofilm Formation with Antimicrobial Peptide-Functionalized Surface Coatings: Recognizing the Dependence on the Bacterial Binding Mode Using Live-Cell Microscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 6799–6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Robert, L.; Pelletier, J.; Dang, W.L.; Taddei, F.; Wright, A.; Jun, S. Robust Growth of Escherichia Coli. Current Biology 2010, 20, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, P.; Papazotos, F.; Potvin-Trottier, L. Microfluidics for Long-Term Single-Cell Time-Lapse Microscopy: Advances and Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 968342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, F.; Kling, A.; Dittrich, P.S. Capturing of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Single Cells of Escherichia Coli. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 2049–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikada, T.; Kanai, T.; Hayashi, M.; Kasai, T.; Oshima, T.; Shiomi, D. Direct Observation of Conversion From Walled Cells to Wall-Deficient L-Form and Vice Versa in Escherichia Coli Indicates the Essentiality of the Outer Membrane for Proliferation of L-Form Cells. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 645965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistretta, M.; Cimino, M.; Campagne, P.; Volant, S.; Kornobis, E.; Hebert, O.; Rochais, C.; Dallemagne, P.; Lecoutey, C.; Tisnerat, C.; et al. Dynamic Microfluidic Single-Cell Screening Identifies Pheno-Tuning Compounds to Potentiate Tuberculosis Therapy. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolic, N.; Anagnostidis, V.; Tiwari, A.; Chait, R.; Gielen, F. Droplet-Based Methodology for Investigating Bacterial Population Dynamics in Response to Phage Exposure. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1260196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Quellec, L.; Aristov, A.; Gutiérrez Ramos, S.; Amselem, G.; Bos, J.; Baharoglu, Z.; Mazel, D.; Baroud, C.N. Measuring Single-Cell Susceptibility to Antibiotics within Monoclonal Bacterial Populations. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cama, J.; Al Nahas, K.; Fletcher, M.; Hammond, K.; Ryadnov, M.G.; Keyser, U.F.; Pagliara, S. An Ultrasensitive Microfluidic Approach Reveals Correlations between the Physico-Chemical and Biological Activity of Experimental Peptide Antibiotics. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conners, R.; McLaren, M.; Łapińska, U.; Sanders, K.; Stone, M.R.L.; Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Pagliara, S.; Daum, B.; Rakonjac, J.; Gold, V.A.M. CryoEM Structure of the Outer Membrane Secretin Channel pIV from the F1 Filamentous Bacteriophage. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cama, J.; Voliotis, M.; Metz, J.; Smith, A.; Iannucci, J.; Keyser, U.F.; Tsaneva-Atanasova, K.; Pagliara, S. Single-Cell Microfluidics Facilitates the Rapid Quantification of Antibiotic Accumulation in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 2765–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kepiro, I.; Ryadnov, M.G.; Pagliara, S. Single Cell Killing Kinetics Differentiate Phenotypic Bacterial Responses to Different Antibacterial Classes. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e03667-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Phetsang, W.; Stone, M.R.L.; Kc, S.; Butler, M.S.; Cooper, M.A.; Elliott, A.G.; Łapińska, U.; Voliotis, M.; Tsaneva-Atanasova, K.; et al. Synthesis of Vancomycin Fluorescent Probes That Retain Antimicrobial Activity, Identify Gram-Positive Bacteria, and Detect Gram-Negative Outer Membrane Damage. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.; Stokes, J.M.; Cervantes, B.; Penkov, S.; Friedrichs, J.; Renner, L.D.; Collins, J.J. Cytoplasmic Condensation Induced by Membrane Damage Is Associated with Antibiotic Lethality. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Song, Y.; Chen, X.; Yin, J.; Wang, P.; Huang, H.; Yin, H. Single-Cell Microfluidics Enabled Dynamic Evaluation of Drug Combinations on Antibiotic Resistance Bacteria. Talanta 2023, 265, 124814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Torres, J.; Lelek, M.; Quereda, J.J.; Sachse, M.; Manina, G.; Ershov, D.; Tinevez, J.-Y.; Radoshevich, L.; Maudet, C.; Chaze, T.; et al. Listeriolysin S: A Bacteriocin from Listeria Monocytogenes That Induces Membrane Permeabilization in a Contact-Dependent Manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118, e2108155118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistretta, M.; Gangneux, N.; Manina, G. Microfluidic Dose–Response Platform to Track the Dynamics of Drug Response in Single Mycobacterial Cells. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 19578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strutt, R.; Jusková, P.; Berlanda, S.F.; Krämer, S.D.; Dittrich, P.S. Engineering a Biohybrid System to Link Antibiotic Efficacy to Membrane Depth in Bacterial Infections. Small 2025, 21, 2412399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, N.E.; Bolognesi, G.; Flemming, A.J.; Brooks, N.J.; Barter, L.M.C.; Ces, O. Multiplexed Droplet Interface Bilayer Formation. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 4653–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahyazadeh Shourabi, A.; Iacona, M.; Aubin-Tam, M.-E. Microfluidic System for Efficient Molecular Delivery to Artificial Cell Membranes. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 1842–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Ghorbanpoor, H.; Öztürk, Y.; Kaygusuz, Ö.; Avcı, H.; Darcan, C.; Trabzon, L.; Güzel, F.D. On-chip Label-free Impedance-based Detection of Antibiotic Permeation. IET Nanobiotechnology 2021, 15, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Dai, Y.; Ge, A.; Chen, X.; Gong, Y.; Lam, T.H.; Lee, K.; Han, X.; Ji, Y.; Shen, W.; et al. Ultrafast Evolution of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance by Picoliter-Scale Centrifugal Microfluidics. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 18842–18851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disney-McKeethen, S.; Seo, S.; Mehta, H.; Ghosh, K.; Shamoo, Y. Experimental Evolution of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa to Colistin in Spatially Confined Microdroplets Identifies Evolutionary Trajectories Consistent with Adaptation in Microaerobic Lung Environments. mBio 2023, 14, e01506-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Disney-McKeethen, S.; Prabhakar, R.G.; Song, X.; Mehta, H.H.; Shamoo, Y. Identification of Evolutionary Trajectories Associated with Antimicrobial Resistance Using Microfluidics. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoheir, A.E.; Späth, G.P.; Niemeyer, C.M.; Rabe, K.S. Microfluidic Evolution-On-A-Chip Reveals New Mutations That Cause Antibiotic Resistance. Small 2021, 17, 2007166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, K.; Dukic, B.; Hodula, O.; Ábrahám, Á.; Csákvári, E.; Dér, L.; Wetherington, M.T.; Noorlag, J.; Keymer, J.E.; Galajda, P. Emergence of Resistant Escherichia Coli Mutants in Microfluidic On-Chip Antibiotic Gradients. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 820738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, C.; Larsson, J.; Hjort, K.; Elf, J.; Andersson, D.I. The Highly Dynamic Nature of Bacterial Heteroresistance Impairs Its Clinical Detection. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.; Goldlust, K.; Quebre, V.; Shen, M.; Lesterlin, C.; Bouet, J.-Y.; Yamaichi, Y. Vertical and Horizontal Transmission of ESBL Plasmid from Escherichia Coli O104:H4. Genes 2020, 11, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, M.; Li, R.; He, Z.; Dechesne, A.; Smets, B.F.; Sheng, G. Single-Cell Analysis Reveals Antibiotic Affects Conjugative Transfer by Modulating Bacterial Growth Rather than Conjugation Efficiency. Environment International 2025, 198, 109385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elitas, M.; Dhar, N.; McKinney, J.D. Revealing Antibiotic Tolerance of the Mycobacterium Smegmatis Xanthine/Uracil Permease Mutant Using Microfluidics and Single-Cell Analysis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanous, J.; Claudi, B.; Tripathi, V.; Li, J.; Goormaghtigh, F.; Bumann, D. Limited Impact of Salmonella Stress and Persisters on Antibiotic Clearance. Nature 2025, 639, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umetani, M.; Fujisawa, M.; Okura, R.; Nozoe, T.; Suenaga, S.; Nakaoka, H.; Kussell, E.; Wakamoto, Y. Observation of Persister Cell Histories Reveals Diverse Modes of Survival in Antibiotic Persistence. eLife 2025, 14, e79517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawska, L.P.; Kuipers, O.P. Antibiotic Tolerance in Environmentally Stressed Bacillus Subtilis : Physical Barriers and Induction of a Viable but Nonculturable State. microLife 2022, 3, uqac010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuse, S.; Shan, Y.; Canas-Duarte, S.J.; Bakshi, S.; Sun, W.-S.; Mori, H.; Paulsson, J.; Lewis, K. Bacterial Persisters Are a Stochastically Formed Subpopulation of Low-Energy Cells. PLoS Biol 2021, 19, e3001194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollerová, S.; Jouvet, L.; Smelková, J.; Zunk-Parras, S.; Rodríguez-Rojas, A.; Steiner, U.K. Phenotypic Resistant Single-Cell Characteristics under Recurring Ampicillin Antibiotic Exposure in Escherichia Coli. mSystems 2024, 9, e00256-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łapińska, U.; Voliotis, M.; Lee, K.K.; Campey, A.; Stone, M.R.L.; Tuck, B.; Phetsang, W.; Zhang, B.; Tsaneva-Atanasova, K.; Blaskovich, M.A.; et al. Fast Bacterial Growth Reduces Antibiotic Accumulation and Efficacy. eLife 2022, 11, e74062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandis, G.; Larsson, J.; Elf, J. Antibiotic Perseverance Increases the Risk of Resistance Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120, e2216216120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Beltran, J.C.R.; Rodríguez-Beltrán, J.; Aguilar-Luviano, O.B.; Velez-Santiago, J.; Mondragón-Palomino, O.; MacLean, R.C.; Fuentes-Hernández, A.; San Millán, A.; Peña-Miller, R. Plasmid-Mediated Phenotypic Noise Leads to Transient Antibiotic Resistance in Bacteria. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koganezawa, Y.; Umetani, M.; Sato, M.; Wakamoto, Y. History-Dependent Physiological Adaptation to Lethal Genetic Modification under Antibiotic Exposure. eLife 2022, 11, e74486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.K.; Łapińska, U.; Tolle, G.; Micaletto, M.; Zhang, B.; Phetsang, W.; Verderosa, A.D.; Invergo, B.M.; Westley, J.; Bebes, A.; et al. Heterogeneous Efflux Pump Expression Underpins Phenotypic Resistance to Antimicrobial Peptides. eLife 2025, 13, RP99752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong-Bolduc, Q.C.; Wang, Y.; Ferrer-Espada, R.; Reedy, J.L.; Martens, A.T.; Goulev, Y.; Paulsson, J.; Vyas, J.M.; Hooper, D.C. Staphylococcus Aureus AbcA Transporter Enhances Persister Formation under β-Lactam Exposure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2024, 68, e01340-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, O.; Smith, A.; Zarkan, A.; Cama, J.; Invergo, B.M.; Belgami, D.; Caño-Muñiz, S.; Metz, J.; O’Neill, P.; Jeffries, A.; et al. Persister Escherichia Coli Cells Have a Lower Intracellular pH than Susceptible Cells but Maintain Their pH in Response to Antibiotic Treatment. mBio 2021, 12, e00909-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, V.O.; Chen, M.; Hammarstrom, B.; Hammond, R.J.H.; Glynne-Jones, P.; Gillespie, S.H.; Dholakia, K. Real-Time Monitoring of Live Mycobacteria with a Microfluidic Acoustic-Raman Platform. Commun Biol 2020, 3, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yin, F.; Qin, Q.; Qiao, L. Molecular Responses during Bacterial Filamentation Reveal Inhibition Methods of Drug-Resistant Bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120, e2301170120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahryari, S.; Ahmad, S.; Foik, I.P.; Jankowski, P.; Samborski, A.; Równicki, M.; Vasantham, S.K.; Garstecki, P. Bacterial Strain Type and TEM-1 Enzyme Allele Impact Antibiotic Susceptibility Distribution in Monoclonal Populations: A Single-Cell Droplet Approach. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 242143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros-Medina, I.; Robles-Ramos, M.Á.; Sobrinos-Sanguino, M.; Luque-Ortega, J.R.; Alfonso, C.; Margolin, W.; Rivas, G.; Monterroso, B.; Zorrilla, S. Evidence for Biomolecular Condensates Formed by the Escherichia Coli MatP Protein in Spatiotemporal Regulation of the Bacterial Cell Division Cycle. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 309, 142691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterroso, B.; Robles-Ramos, M.Á.; Sobrinos-Sanguino, M.; Luque-Ortega, J.R.; Alfonso, C.; Margolin, W.; Rivas, G.; Zorrilla, S. Bacterial Division Ring Stabilizing ZapA versus Destabilizing SlmA Modulate FtsZ Switching between Biomolecular Condensates and Polymers. Open Biol. 2023, 13, 220324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

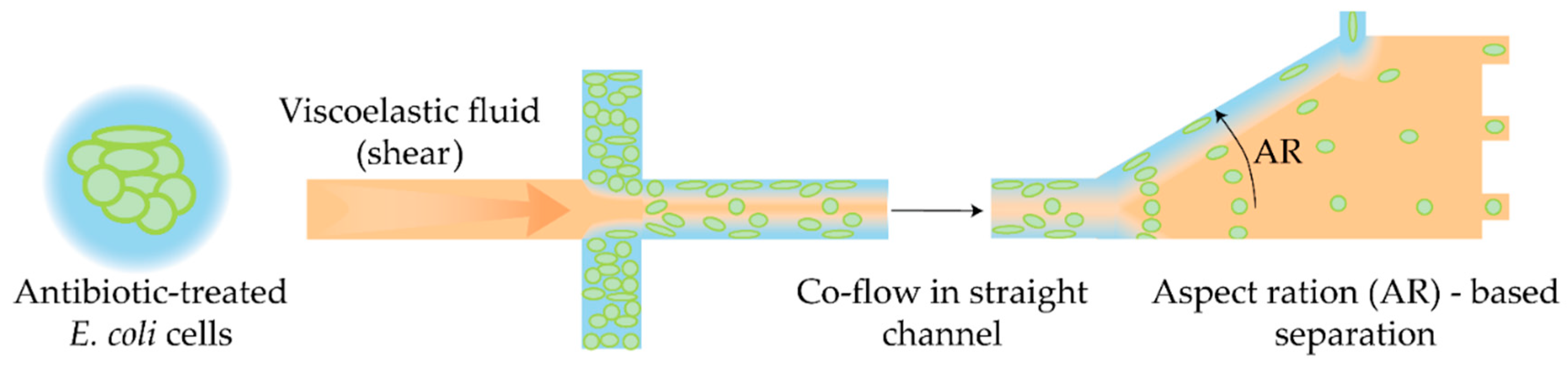

- Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Okano, K.; Tang, T.; Inoue, K.; Yamazaki, Y.; Kamikubo, H.; Cain, A.K.; Tanaka, Y.; Inglis, D.W.; et al. Shape-Based Separation of Drug-Treated Escherichia Coli Using Viscoelastic Microfluidics. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 2801–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuppara, A.M.; Padron, G.C.; Sharma, A.; Modi, Z.; Koch, M.D.; Sanfilippo, J.E. Shear Flow Patterns Antimicrobial Gradients across Bacterial Populations. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

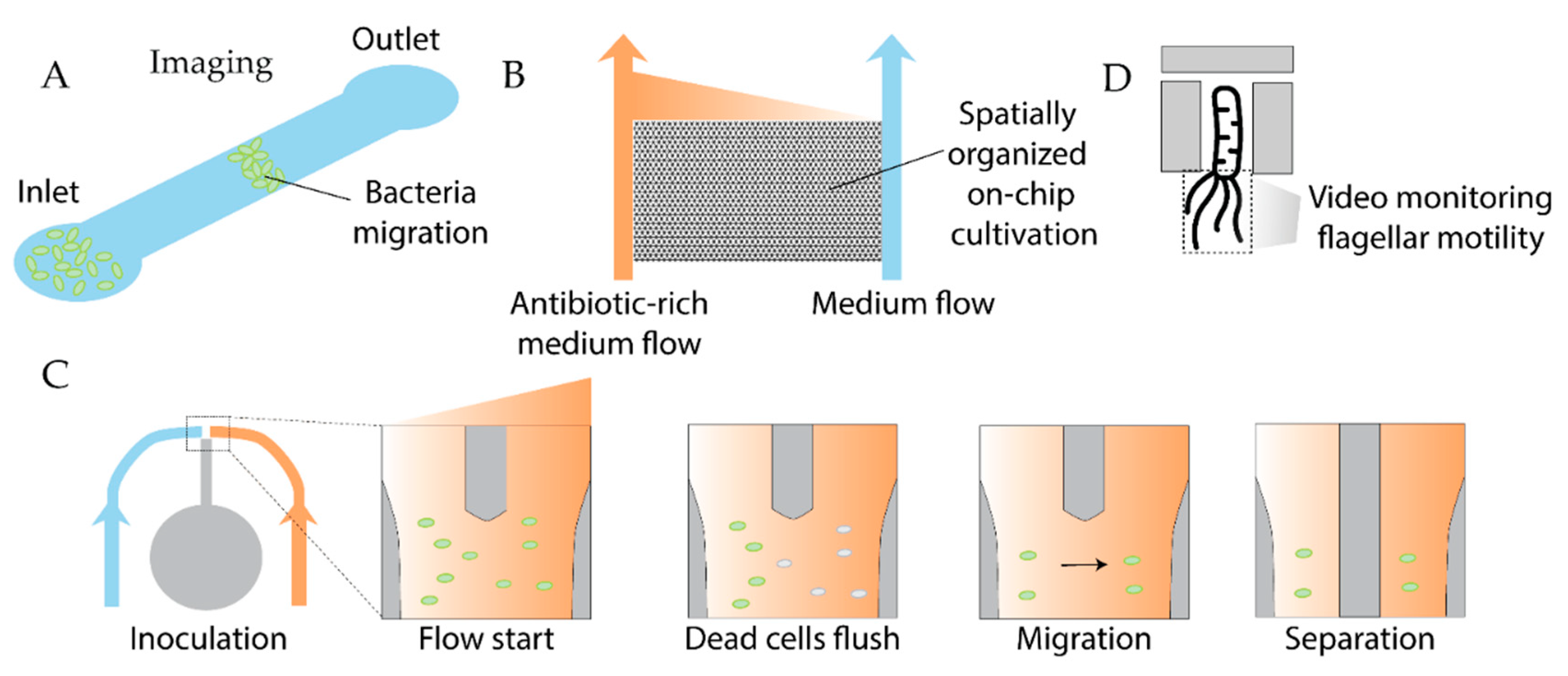

- Liu, Y.; Lehnert, T.; Gijs, M.A.M. Effect of Inoculum Size and Antibiotics on Bacterial Traveling Bands in a Thin Microchannel Defined by Optical Adhesive. Microsyst Nanoeng 2021, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcalde, R.E.; Dundas, C.M.; Dong, Y.; Sanford, R.A.; Keitz, B.K.; Fouke, B.W.; Werth, C.J. The Role of Chemotaxis and Efflux Pumps on Nitrate Reduction in the Toxic Regions of a Ciprofloxacin Concentration Gradient. The ISME Journal 2021, 15, 2920–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, N.M.; Wheeler, J.H.R.; Deroy, C.; Booth, S.C.; Walsh, E.J.; Durham, W.M.; Foster, K.R. Suicidal Chemotaxis in Bacteria. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 7608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroy, C.; Wheeler, J.H.R.; Rumianek, A.N.; Cook, P.R.; Durham, W.M.; Foster, K.R.; Walsh, E.J. Reconfigurable Microfluidic Circuits for Isolating and Retrieving Cells of Interest. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 25209–25219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitruzzello, G.; Baumann, C.G.; Johnson, S.; Krauss, T.F. Single-Cell Motility Rapidly Quantifying Heteroresistance in Populations of Escherichia Coli and Salmonella Typhimurium. Small Science 2022, 2, 2100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadarajan, A.R.; Allan, R.N.; Valentin, J.D.P.; Castañeda Ocampo, O.E.; Somerville, V.; Pietsch, F.; Buhmann, M.T.; West, J.; Skipp, P.J.; Van Der Mei, H.C.; et al. An Integrated Model System to Gain Mechanistic Insights into Biofilm-Associated Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa MPAO1. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2020, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentin, J.D.P.; Straub, H.; Pietsch, F.; Lemare, M.; Ahrens, C.H.; Schreiber, F.; Webb, J.S.; Van Der Mei, H.C.; Ren, Q. Role of the Flagellar Hook in the Structural Development and Antibiotic Tolerance of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms. The ISME Journal 2022, 16, 1176–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyżek, P.; Migdał, P.; Grande, R.; Gościniak, G. Biofilm Formation of Helicobacter Pylori in Both Static and Microfluidic Conditions Is Associated With Resistance to Clarithromycin. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 868905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Singh, A.; Tiwari, N.; Naik, A.; Chatterjee, R.; Chakravortty, D.; Basu, S. Observations on Phenomenological Changes in Klebsiella Pneumoniae under Fluidic Stresses. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 9239–9253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.V.; Shourabi, A.Y.; Yaghoobi, M.; Zhang, S.; Simpson, K.W.; Abbaspourrad, A. A High-Throughput Integrated Biofilm-on-a-Chip Platform for the Investigation of Combinatory Physicochemical Responses to Chemical and Fluid Shear Stress. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islayem, D.; Arya, S.; Yasmeen, N.; Hallfors, N.; Ngoc, H.; Alkhatib, S.; Mela, I.; Anwar, S.; Truong, V.K.; Pappa, A.M. A Modular, Lego-Like Microfluidic Platform for Multimodal Analysis of Biofilm Formation and Antimicrobial Response. Adv Materials Inter 2025, e00303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savorana, G.; Słomka, J.; Stocker, R.; Rusconi, R.; Secchi, E. A Microfluidic Platform for Characterizing the Structure and Rheology of Biofilm Streamers. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 3878–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia-Ponce, Z.; Secchi, E.; Toyofuku, M.; Marinova, G.; Savorana, G.; Eberl, L. Genotoxic Stress Stimulates eDNA Release via Explosive Cell Lysis and Thereby Promotes Streamer Formation of Burkholderia Cenocepacia H111 Cultured in a Microfluidic Device. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zeng, L.; Liu, P.; Ma, L.Z.; Liu, J. A Microfluidic Approach for Quantitative Study of Spatial Heterogeneity in Bacterial Biofilms. Small Science 2022, 2, 2200047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, P.-C.; Eriksson, O.; Sjögren, J.; Fatsis-Kavalopoulos, N.; Kreuger, J.; Andersson, D.I. A Microfluidic Chip for Studies of the Dynamics of Antibiotic Resistance Selection in Bacterial Biofilms. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 896149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Gholizadeh, H.; Young, P.; Traini, D.; Li, M.; Ong, H.X.; Cheng, S. Real-time In-situ Electrochemical Monitoring of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms Grown on Air–Liquid Interface and Its Antibiotic Susceptibility Using a Novel Dual-chamber Microfluidic Device. Biotech & Bioengineering 2023, 120, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiermann, R.; Sandler, M.; Ahir, G.; Sauls, J.T.; Schroeder, J.; Brown, S.; Le Treut, G.; Si, F.; Li, D.; Wang, J.D.; et al. Tools and Methods for High-Throughput Single-Cell Imaging with the Mother Machine. eLife 2024, 12, RP88463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.; Wu, N.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Shen, F. Formation and Parallel Manipulation of Gradient Droplets on a Self-Partitioning SlipChip for Phenotypic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liu, X.; Yu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Hu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Dai, J.; Wu, N.; Shen, F. Combinatorial Screening SlipChip for Rapid Phenotypic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 3952–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Ren, Y.; Hu, Q.; Xu, L.; Chen, W.; Liu, J.; Wu, N.; Tao, M.; Sun, J.; et al. Rapid and Precise Treatment Selection for Antimicrobial-Resistant Infection Enabled by a Nano-Dilution SlipChip. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2025, 271, 117084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengoju, S.; Wohlfeil, S.; Munser, A.S.; Boehme, S.; Beckert, E.; Shvydkiv, O.; Tovar, M.; Roth, M.; Rosenbaum, M.A. Optofluidic Detection Setup for Multi-Parametric Analysis of Microbiological Samples in Droplets. Biomicrofluidics 2020, 14, 024109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, A.; Hengoju, S.; Martin, K.; Rosenbaum, M.A. Advancing Droplet-Based Microbiological Assays: Optofluidic Detection Meets Multiplexed Droplet Generation. Analyst 2025, 150, 3137–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacocha, N.; Bogusławski, J.; Horka, M.; Makuch, K.; Liżewski, K.; Wojtkowski, M.; Garstecki, P. High-Throughput Monitoring of Bacterial Cell Density in Nanoliter Droplets: Label-Free Detection of Unmodified Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-J.; Chao, P.-H.; Cheng, H.-W.; Wang, J.-K.; Wang, Y.-L.; Han, Y.-Y.; Huang, N.-T. An Antibiotic Concentration Gradient Microfluidic Device Integrating Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy for Multiplex Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 1805–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.-K.; Cheng, H.-W.; Liao, C.-C.; Lin, S.-J.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Wang, J.-K.; Wang, Y.-L.; Huang, N.-T. Bacteria Encapsulation and Rapid Antibiotic Susceptibility Test Using a Microfluidic Microwell Device Integrating Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 2520–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, D.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Sutton, J.M.; Morgan, H. Electrical Broth Micro-Dilution for Rapid Antibiotic Resistance Testing. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hou, Z.; Yan, B.; Cao, X.; Su, B.; Lv, M.; Cui, H.; Zhang, C. Research on Drug Efficacy Using a Terahertz Metasurface Microfluidic Biosensor Based on Fano Resonance Effect. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 52092–52103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Honma, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Shida, Y.; Tsuda, Y.; Hidaka, K.; Ogasawara, W. 7-Aminocoumarin-4-Acetic Acid as a Fluorescent Probe for Detecting Bacterial Dipeptidyl Peptidase Activities in Water-in-Oil Droplets and in Bulk. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 2416–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibiotic | Device | Detection method | Studied strains | Observed effect | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDR strains |

Figure 10A MM |

Microscopy |

Е. Coli Salmonella enterica |

Single cell growth rate | [170] |

| β-lactams | Figure 10A | Microscopy | E.coli | Visualization of conjugational and vertical transfer events | [171] |

| Isoniazid | Figure 11C | Microscopy |

M. smegmatis msm2570::Tn mutant |

Individual cells growth and lysis kinetics | [173] |

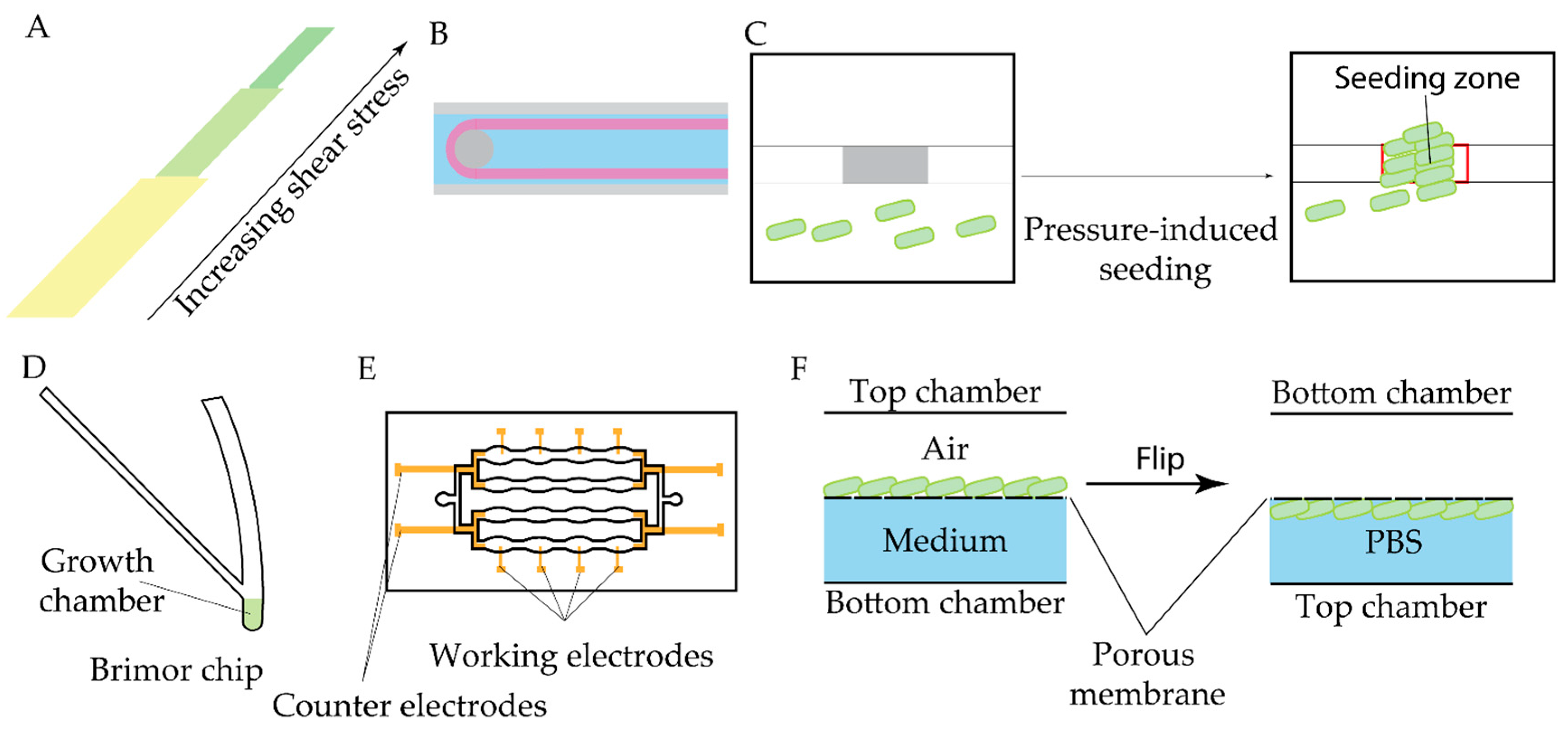

| Antibiotics | Device | Detection method | Tested biofilms | Key features | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gentamicin Streptomycin |

2PAB Figure 16A |

Microscopy |

E. coli P. aeruginosa |

Simultaneous control of antibiotic treatment and shear stress | [202] |

| Berberine | Figure 16C | Microscopy |

E. coli P. aeruginosa S. typimurium K. pneumonia B. subtilis S. aureus E. faecium M. smegmatis |

Spatially controlled seeding Epoxy-resin sealing to block oxygen penetration Suitable for broad range of bacteria |

[206] |

| Ciprofloxacin | Brimor Figure 16D |

Microscopy | E. coli | Long-term cultivation Simple manufacturing procedure |

[207] |

| Ciprofloxacin | Figure 16F | Pyocyanin detection | P. aeruginosa | Air-liquid interface biofilms Electochemical detection of biomarker |

[208] |

| Tetracycline Chloramphenicol Amikacin Coatings and nanoparticles |

Figure 16E | Microscopy, electrical impedance | P. aeruginosa | Label-free monitoring Modular structure to assess migration and regrowth Localized shear stress variations |

[203] |

| Mitomycin C Ciprofloxacin |

Figure 16B | Microscopy |

P. aeruginosa Burkholderia cenocepacia |

Visualization of streamers | [204,205] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).