Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- • Block 1: MACC theoretical and historical analysis summarizes, describes and reveals modifications and diversity of MACC’s;

- • Block 2: MACC case study application focuses on case study that illustrates different uses and levels of integration of MACC into national climate policy-making process, serving as experience of full cycle approach towards carbon neutrality.

3. Results

3.1. Modifications and Diversity of Marginal Abatement Cost Curves

3.2. Historical Insights into Experience of Full Cycle Approach Towards Carbon Neutrality

3.2.1. Adoption and Improvement of MACC Methodology for Latvia

3.2.2. Developing the Use and Diversity of the MACC Approach

3.2.3. Using MACC in Policy Discussion and Knowledge Transfer

3.2.4. Using MACC in Creating New Knowledge and Improving Data Gathering

- • To identify for each measure the type of land management/biome/ecosystem to which it relates;

- • To understand which services of the relevant ecosystem are affected by the measure if it is introduced (assuming that the impact is positive);

- • To find the value of the ecosystem service(s) to be linked to the relevant ecosystem.

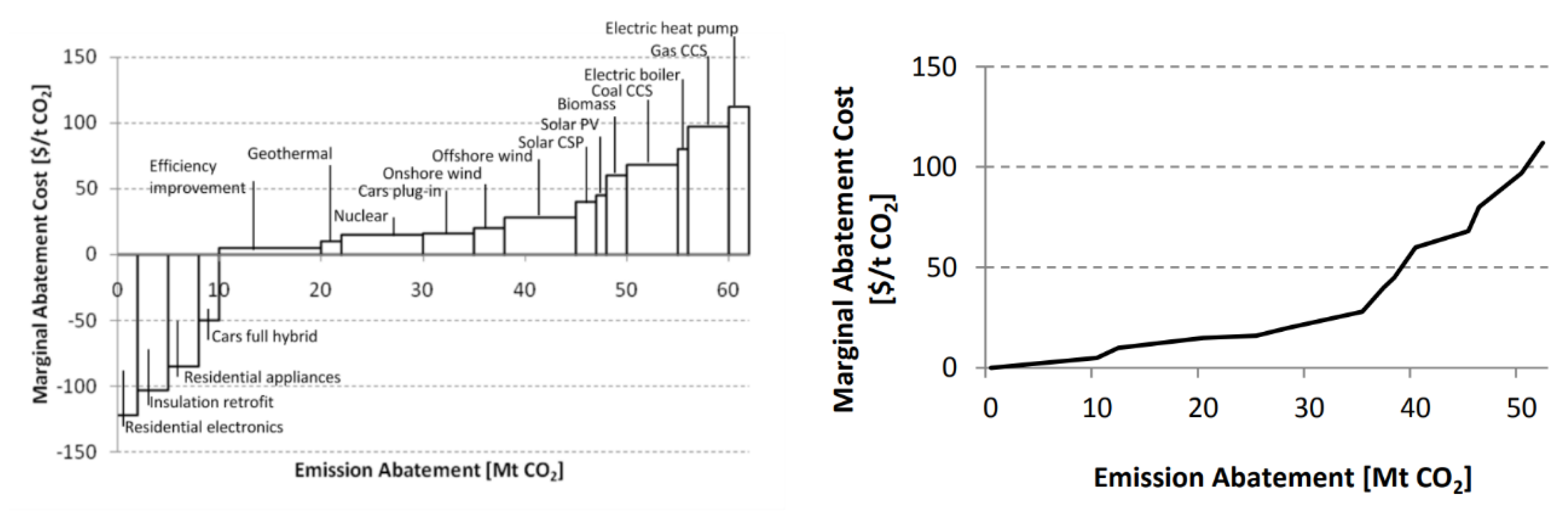

- • The climate change mitigation potential of negative cost-negative measures may be overestimated without paying sufficient attention to measures that are less cost-effective;

- • Negative cost measures are adequately assessed as the most cost-effective or income-generating, but their mutual ranking may not be correct due to the peculiarities of the mathematical algorithm of the method.

4. Conclusions

- • By recognizing unique characteristics of different farm types (e.g. intensive, extensive, organic etc.) principle of targeted and equitable distribution of support should be implemented when developing climate related policies and framework for support measures.

- • Comprehensive assessment of GHG mitigation measures, considering their economic, environmental and social impacts, as well as understanding their multiple benefits and robust data collection and analysis can serve as background for data-driven policymaking.

- • Facilitation of knowledge sharing, like knowledge exchange between scientists, policymakers, farmers and other stakeholders, and capacity building, like training and technical assistance to farmers to implement climate friendly practices, can boost more faster transition to carbon neutrality.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Economic Situation and Prospects 2024. 2024. 196 p. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/WESP_2024_Web.pdf.

- Fukase, E. and Will, M. Economic growth, convergence, and world food demand and supply. World Development, 2020, Vol. 132. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Turk, J. Meeting projected food demands by 2050: Understanding and enhancing the role of grazing ruminants. Animal Science, 2016, Vol. 94, pp. 53–62. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Warner, K., Hamza, M., Oliver-Smith, A., Renaud, F. and Julca, A. Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Natural Hazards, 2009, Vol. 55, pp. 689–715. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Pro Oxygen. Latest daily CO2. 2024. Available online: https://www.co2.earth/daily-co2.

- Hatfield-Dodds, S., Schandl, H., Newth, D., Obersteiner, M. Cai, Y., Baynes, T., West, J. and Havlik, P. Assessing global resource use and greenhouse emissions to 2050, with ambitious resource efficiency and climate mitigation policies. Cleaner Production, 2017, Vol. 144, pp. 403-414. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Komarek, A. M., Dunston, S., Enahoro, D., Charles, J., Godfray, H., Herrero, M., Mason-D’Croz, D., Rich, M. K., Scarborough, P., Springmann, M., Sulser, B.T., Wiebe, K. and Willenbockel, D. Income, consumer preferences, and the future of livestock-derived food demand. Global Environmental Change, 2021, Vol. 70. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Maximillian, J., Brusseau, M. L., Glenn, E.P. and Matthias, A.D. Pollution and environmental perturbations in the global system. Environmental and Pollution Science, Third Edition, 2019, pp. 457–476. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Mora, C., Rollins, R.L., Taladay, K., Kantar, M. B., Chock, M., Shimada, M. and Franklin, E. C. Bitcoin emissions alone could push global warming above 2 °C. Nature Climate Change, 2018, Vol. 8, pp. 931–933. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Paris Agreement. 2015, 27 p. Available online: https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf.

- Chen, L., Msigwa, G., Yang, M., Osman, I.A., Fawzy, S., Rooney, W. D. and Yap, P. S. Strategies to achieve a carbon neutral society: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 2022, Vol. 20, pp. 2277–2310. Available online: doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01435-8.

- Wei, Y. M., Chen, K., Kang, J.N., Chen, W., Wang, X. Y. and Zhang X. Policy and Management of Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality: A Literature Review. Engineering, 2022, Vol. 14, pp. 52-63. [CrossRef]

- Usman, I. M. T., Ho, Y. C., Baloo, L., Lam, M. K. and Sujarwo, W. A comprehensive review on the advances of bioproducts from biomass towards meeting net zero carbon emissions (NZCE). Bioresource Technology, 2022, Vol. 366. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- European Union. Clean Planet for all A European strategic long-term vision for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate neutral economy. COM/2018/773, 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0773.

- Climate Action Tracker. CAT net zero target evaluation. 2023. Available online: https://climateactiontracker.org/global/cat-net-zero-target-evaluations/.

- Allen, M., Frame, D., Huntingford, C., Huntingford, C., Jones, C. D., Lowe, J. A., Meinshausen, M., and Meinshausen, N. Warming caused by cumulative carbon emissions towards the trillionth tonne. Nature, 2009, 458(7242), 1163–1166. Available online:. [CrossRef]

- Hale, T., Smith, S. M., Black, R., Cullen, K., Fay, B., Lang, J., and Mahmood, S. Assessing the rapidly-emerging landscape of net zero targets. Climate Policy, 2021, Vol. 22(1), pp. 18–29. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, 2014, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full_wcover.pdf.

- Levin, K., Rich, D., Ross, K., Fransen, T. and Elliott, C. Working paper: Designing and Communicating Net-Zero Targets, 2020, 30 p. Available online: https://www.wri.org/research/designing-and-communicating-net-zero-targets.

- Kesicki, F. Marginal abatement cost curves for policy making -expert-based vs. model-derived curves. Environmental Science & Policy, 2010, 14(8), pp. 1195-1204. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Bockel, L., Sutter, P. and Jonsson, M. Using Marginal Abatement Cost Curves to Realize the Economic Appraisal of Climate Smart Agriculture Policy Options. The EX Ante Carbon-balance Tool, 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/33830c17-609f-4f0f-a034-b471818ecb59/content.

- Blumstein, C. and Stoft, S. E. Technical efficiency, production functions and conservation supply curves. Energy Policy, 1995, Vol. 23(9), pp. 765–768. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Difiglio, C., Duleep, K. G. and Greene, D. L. Cost Effectiveness of Future Fuel Economy Improvements. The Energy Journal, 1990, Vol. 11(1), pp. 65–87. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, A., Atkinson, C., Koomey, J., Meier, A., Mowris, R. J. and Price, L. Conserved energy supply curves for U.S. buildings. Contemporary Economic Policy, 1993, Vol. 11(1), pp. 45–68. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Rentz, O., Haasis, H.-D., Jattke, A., Ruβ, P., Wietschel, M. and Amann, M. Influence of energy-supply structure on emission-reduction costs. Energy, 1994, Vol. 19(6), pp. 641–651. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Least-cost greenhouse planning supply curves for global warming abatement. Energy Policy, 1991, Vol. 19(1), pp. 35–46. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Mills, E., Wilson, D. and Johansson, T. B. Getting started: no-regrets strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Energy Policy, 1991, Vol. 19(6), pp. 526–542. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Sitnicki, S., Budzinski, K., Juda, J., Michna, J. and Szpilewicz, A. Opportunities for carbon emissions control in Poland. Energy Policy, 1991, Vol. 19(10), pp. 995–1002. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Kesicki, F. and Ekins, P. Marginal abatement cost curves: a call for caution. Climate Policy, 2012, Vol. 12(2), pp. 219–236. Available at: . [CrossRef]

- Blok, K., Worrell, E., Cuelenaere, R. and Turkenburg, W. The cost effectiveness of CO2 emission reduction achieved by energy conservation. Energy Policy, 1993, Vol. 21(6), pp. 656–667. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Haoqi, Q., Libo, W. and Weiqi, T. “Lock-in” effect of emission standard and its impact on the choice of market based instruments. Energy Economics, 2017, Vol. 63, pp. 41–50. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Y., Lee, M. and Seeley, K. Does Technological Innovation Really Reduce Marginal Abatement Costs? Some Theory, Algebraic Evidence, and Policy Implications. Environmental and Resource Economics, 2007, Vol. 40(4), pp. 507–527. Available at: . [CrossRef]

- Downing, P. B. and White, L. J. Innovation in pollution control. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 1986, Vol. 13(1), pp. 18–29. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Moran, D., Macleod, M., Wall, E., Eory, V., Mcvittie, A., Barnes, A., Rees, B., Pajot, G., Matthews, R., Smith, P. and Moxey, A. Marginal abatement cost curves for UK agriculture, forestry, land-use and land-use change sector out to 2022. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2009, Vol. 6(24), 242002. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Moran, D., MacLeod, M., Wall, E., Eory, V., McVittie, A., Barnes, A., Rees, R. M., Topp, C. F. E., Pajot, G., Matthews, R., Smith, P. and Moxey, A. Developing carbon budgets for UK agriculture, land-use, land-use change and forestry out to 2022. Climatic Change, 2010, Vol. 105(3–4), pp. 529–553. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D., Shalloo, L., Crosson, P., Donnellan, T., Farrelly, N., Finnan, J., Hanrahan, K., Lalor, S., Lanigan, G., Thorne, F. and Schulte, R. An evaluation of the effect of greenhouse gas accounting methods on a marginal abatement cost curve for Irish agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental Science & Policy, 2014, Vol. 39, pp. 107–118. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Pellerin, S., Bamière, L., Angers, D., Béline, F., Benoit, M., Butault, J.-P., Chenu, C., Colnenne-David, C., De Cara, S., Delame, N., Doreau, M., Dupraz, P., Faverdin, P., Garcia-Launay, F., Hassouna, M., Hénault, C., Jeuffroy, M.-H., Klumpp, K., Metay, A. and Chemineau, P. Identifying cost-competitive greenhouse gas mitigation potential of French agriculture. Environmental Science & Policy, 2017, Vol. 77, pp. 130–139. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Ikkatai, S. Emission reductions policy mix: Industrial sector greenhouse gas emission reductions. In: Climate Change and Global Sustainability, 2013, pp 164-177. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Koslowski, F., Nayak, D. R., Smith, P., Saetnan, E., Ju, X., Guo, L., Han, G., de Perthuis, C., Lin, E. and Moran, D. Greenhouse gas mitigation in Chinese agriculture: Distinguishing technical and economic potentials. Global Environmental Change, 2014, Vol. 26, pp. 53–62. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- McGetrick, J. A., Bubela, T. and Hik, D. S. Automated content analysis as a tool for research and practice: a case illustration from the Prairie Creek and Nico environmental assessments in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 2016, Vol. 35(2), pp. 139–147. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Lēnerts, A., Popluga, D., Naglis-Liepa, K., Rivža P. Fertilizer use efficiency impact on GHG emissions in the Latvian crop sector. Agronomy Research, 2016, Vol. 14(1), pp. 123-133. Available online: https://agronomy.emu.ee/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Vol14-_nr1_Lenerts.pdf.

- Naglis-Liepa. K., Popluga D. and Rivža. P. Typology of Latvian Agricultural Farms in the Context of Mitigation of Agricultural GHG Emissions. 15th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference SGEM 2015 “Ecology, Economics, Education and Legislation” Conference Proceedings, 2015, Vol. II, pp. 513-520.

- Popluga, D., Naglis-Liepa, K., Lenerts, A., Rivza, P. Marginal abatement cost curve for assessing mitigation potential of Latvian agricultural greenhouse gas emissions: case study of crop sector. 17th International multidisciplinary scientific GeoConference SGEM 2017: conference proceedings, 2017, Vol.17: Energy and clean technologies; Issue 41: Nuclear technologies. Recycling. Air pollution and climate change, pp. 511-518.

- Eory, V., Pellerin, S., Carmona Garcia, G., Lehtonen, H., Licite, I., Mattila, H., Lund-Sørensen, T., Muldowney, J., Popluga, D., Strandmark, L. and Schulte, R. Marginal abatement cost curves for agricultural climate policy: State-of-the art, lessons learnt and future potential. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2018, Vol. 182, pp. 705–716. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- De Cara, S. and Jayet, P.-A. Marginal abatement costs of greenhouse gas emissions from European agriculture, cost effectiveness, and the EU non-ETS burden sharing agreement. Ecological Economics, 2011, Vol. 70(9), pp. 1680–1690. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- De Cara, S., Houzé, M. and Jayet, P.-A. Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Agriculture in the EU: A Spatial Assessment of Sources and Abatement Costs. Environmental and Resource Economics, 2005, Vol. 32(4), pp. 551–583. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Hediger, W. Modeling GHG emissions and carbon sequestration in Swiss agriculture: An integrated economic approach. International Congress Series, 2006, Vol. 1293, pp. 86–95. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Golub, A., Hertel, T., Lee, H.-L., Rose, S. and Sohngen, B. The opportunity cost of land use and the global potential for greenhouse gas mitigation in agriculture and forestry. Resource and Energy Economics, 2009, Vol. 31(4), pp. 299–319. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Pérez Dominguez, I., Britz, W. and Holm-Müller, K. Trading schemes for greenhouse gas emissions from European agriculture : A comparative analysis based on different implementation options. Revue d’études En Agriculture et Environnement, 2009, Vol. 90(3), pp. 287–308. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Schneider, U. A., McCarl, B. A. and Schmid, E. Agricultural sector analysis on greenhouse gas mitigation in US agriculture and forestry. Agricultural Systems, 2007, Vol. 94(2), pp. 128–140. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Beach, R. H., DeAngelo, B. J., Rose, S., Li, C., Salas, W. and DelGrosso, S. J. Mitigation potential and costs for global agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Agricultural Economics, 2008, Vol. 38(2), pp. 109–115. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Höglund-Isaksson, L., Winiwarter, W., Purohit, P., Rafaj, P., Schöpp, W. and Klimont, Z. EU low carbon roadmap 2050: Potentials and costs for mitigation of non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions. Energy Strategy Reviews, 2012, Vol. 1(2), pp. 97–108. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Kreišmane, Dz., Aplociņa, E., Naglis-Liepa, K., Bērziņa, L., Frolova, O., Lēnerts, A. Diet optimization for dairy cows to reduce ammonia emissions. International scientific conference proceedings “Research for Rural Development 2021”, 2021, Vol.36, pp. 36-43. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Ekins, P., Kesicki, F., and Smith, A.Z.P. Marginal Abatement Cost Curves: A call for caution. 2011. [A report from the UCL Energy Institute to, and commissioned by, Grenpeace UK]. Available online: https://www.homepages.ucl.ac.uk/~ucft347/MACCCritGPUKFin.pdf.

- Levihn, F., Nuur, C., and Laestadius, S. Marginal abatement cost curves and abatement strategies: Taking option interdependency and investments unrelated to climate change into account. Energy, 2014, 76, 336–344. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Ponz-Tienda, J. L., Prada-Hernández, A. V., Salcedo-Bernal, A., and Balsalobre-Lorente, D. Marginal Abatement Cost Curves (MACC): Unsolved Issues, Anomalies, and Alternative Proposals. In: R. Álvarez Fernández, S. Zubelzu, & R. Martínez (Eds.), Carbon Footprint and the Industrial Life Cycle (pp. 269–288). 2017. Springer International Publishing. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. The ranking of negative-cost emissions reduction measures. Energy Policy, 2012, 48, 430–438. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Ward, D. J. The failure of marginal abatement cost curves in optimising a transition to a low carbon energy supply. Energy Policy, 2014, 73, 820–822. Available online: . [CrossRef]

| Thematic blocks of study | Methods | Approach | Focus | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: MACC theoretical and historical analysis | Literature review Analysis and synthesis |

Comprehensive evaluation of MACC development over time from scientific literature | Identification of modifications, diversity, and comparative strengths/weaknesses of MACCs | Understanding of evidence-based foundation for cost-effectiveness modelling and policy assessment |

| Block 2: MACC case study application | Expert judgement and experience | Utilize project results from Latvian climate policy initiatives | Focus on how MACCs are integrated and applied within Latvia’s national climate policy frameworks for actionable insights | Transforms theoretical MACC concepts into actionable policy decisions |

| Analysed aspect | Expert judgement-based MACCs | Model-derived MACCs |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Extensive technological detail Possibility of considering technology specific market distortions Easy understanding of technology-specific abatement curves |

Bottom-up Model explicitly maps energy technologies in detail Top-down Macroeconomic feedbacks and costs considered Both Interactions between measures included Consistent baseline emission pathway Intertemporal interactions incorporated Possibility to represent uncertainty Incorporate of behavioural factors Comparably quick generation |

| Weaknesses | Lack of integration of behavioural factors Absence of interactions and dependencies between mitigation measures Potential for inconsistent baseline emissions No representation of intertemporal interactions Limited representation of uncertainty Sometimes restricted to a single economic sector, without the ability to combine abatement curves across sectors No representation of macroeconomic feedbacks Simplified technological cost structure |

Bottom-up No macroeconomic feedbacks Direct cost in the energy sector Risk of penny-switching No reflection of indirect rebound effect Top-down Model lacks technological detail Possible unrealistic physical implications Both No technological detail in representation of MAC curve Assumption of a rational agent, disregarding most market distortions |

| Period | Stage | Action | Importance and practical use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-2017 | Adopting and improving of MACC methodology for Latvia | Developed MACC for five typical farm clusters | Created a methodology suitable for Latvia created using the cluster method Prepared necessary methodology (scientific monograph) for use of MACC approach Analysed several dozen GHG mitigation measures and 17 were selected for deeper analysis and practical implementation |

| 2018-2020 | Developing the use and diversity of the MACC approach | Developed MACC with C capture measures and analysed LULUCF and agriculture interaction | Estimated the overlap effect of multiple sectors (agricultural and LULUCF) Evaluated new C capture measures Used MACC for policy making Identified new research directions |

| 2021-2023 | Using MACC in policy discussion and knowledge transfer | Developed MACC with ammonia emission reduction measures and organized set of discussion events with farmers | Transferred knowledge to NGOs and farmers Prepared information for the improvement of climate and agricultural policy Prepared information for improvement of air quality policy |

| 2023-2025 | Using MACC in creating new knowledge and improving data gathering | Developed MACC for CAP GHG reduction measures | Evaluated new GHG emissions reduction measures in agriculture Developed recommendations for the accounting of agricultural data for the evaluation of the reducing effects of GHG and ammonia emissions |

| Developed MACC including ecosystem services evaluation | Developed a methodology for incorporating the value of ecosystem services into the MACC Developed additional variations of the MACC curves for evaluating the cost effectiveness of GHG and ammonia emission reduction measures, reflecting different rates of implementation stages of the measures |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).