1. Introduction

Quality education (SDG4) is the foundation for personal and social development. It is defined as the education that helps individuals reach their full potential by meeting their basic learning needs, especially in literacy and numeracy, and by fostering essential life skills [

1]. It aims to ensure inclusive and equitable access to education and lifelong learning for all citizens and can be considered a prerequisite for reducing inequalities between and within the countries (SDG10), addressing social exclusion, and mitigating unequal access to opportunities and resources [

2]. By equipping individuals with the skills, knowledge, and opportunities necessary for advancement, quality education helps societies break cycles of poverty and marginalization [

3], and act as a catalyst for achieving SDG 10.

Quality education operates on variable interconnected levels: the system, concerning effective management and governance, policy implementation, resource allocation, and reliable assessment mechanisms [

4]. One critical dimension cutting across all these levels is the evolving role of educators in adapting to contemporary demands. The accelerating integration of digital technologies in education has significantly reshaped teaching expectations and professional practices. Educators today are expected not only to use digital tools competently but also to embed them meaningfully within pedagogical contexts [

5]. This shift redefines digital competence (DC) as both a pedagogical and professional construct [

6]. The DigCompEdu framework (Digital Competence Framework for Educators) articulates this dual role by identifying 22 competences across six domains, promoting the strategic use of digital technologies to foster inclusive, effective, and innovative learning environments [

7]. Complementing this, the TPACK model (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge) highlights the intersection of technological expertise, pedagogical knowledge, and content understanding [

8,

9], providing high-quality teaching practices, imperative for quality and inclusive education [

10].

While frameworks such as DigCompEdu and TPACK provide structured approaches for examining teachers’ digital practices, the concept of DC remains debated, often overlapping with or being conflated with digital literacy. Some scholars argue for narrower, skill-based definitions, whereas others emphasize their broader pedagogical and professional dimensions [

11,

12]. This conceptual ambiguity underscores the importance of examining DC within specific sociocultural and institutional contexts. Increasingly, teacher education adopts DC as a broader term encompassing critical, responsible, and pedagogically grounded use of technology [

6,

11,

13]. National adaptations—such as Digital Teaching Competence—generally align with DigCompEdu while addressing local curricular priorities [

7,

14].

In this study, DC is examined within the complex realities of multilingual and multicultural mainstream classrooms in Greece and Cyprus—contexts shaped by shifting demographics and growing (im)migrant student populations [

15,

16,

17] – as a means for reducing inequalities and ensuring access to quality education by disadvantaged groups. These classrooms challenge conventional approaches to instructional design and demand inclusive, culturally sustaining digital pedagogy. Beyond a static skillset, DC is approached here as situated knowledge, shaped by educators’ beliefs, attitudes, and ideologies [

18]. The study thus treats teachers’ self-assessments of DC not merely as indicators of proficiency, but as windows into how they navigate cultural diversity, technological expectations, and sustainability-aligned inclusive practice in their everyday work.

1.1. Τheoretical Background

To guide this investigation, the study employs a dual conceptual framework combining DigCompEdu and TPACK. DigCompEdu specifies the digital knowledge, skills, and attitudes required for educators to design inclusive, reflective, and pedagogically meaningful learning environments [

6]. TPACK complements this perspective by conceptualizing how technology interacts with pedagogy and content knowledge in practice [

9,

19]. Together, the two frameworks offer a comprehensive lens for examining how teachers enact DC in diverse classroom contexts, particularly in relation to global commitments to education for sustainability, and more specifically to SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

SDG 4 emphasizes inclusive and equitable access to high-quality education for all learners, regardless of linguistic or cultural background [

3]. Within this vision, the development of educators’ DCs is crucial to ensuring effective technology integration that promotes differentiated instruction, learner empowerment, and pedagogical innovation [

20,

21]. SDG 10 calls for dismantling structural barriers that prevent marginalized groups, such as (im)migrant students, from fully participating in education [

22]. The dual framework addresses these imperatives by foregrounding context-sensitive, culturally sustaining digital pedagogy that is adaptive and inclusive. Teacher professional development is therefore positioned not only as a local policy priority but also as an instrument for advancing global commitments to equity, inclusion, and sustainability in education.

DigCompEdu, developed by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre [

6], provides a comprehensive model for supporting and assessing the DC of educators across educational levels and contexts. Originating from the broader DigComp framework [

23,

24], DigCompEdu adapts these competences to teaching realities, organizing them into six areas and 22 specific competences. It emphasizes pedagogical intentionality (professional engagement, digital resources, teaching and learning, assessment, learner empowerment, and fostering learners’ DC) and ethical considerations, making it especially relevant to inclusive and differentiated instruction. Within multilingual and multicultural classrooms, DigCompEdu supports teachers in designing responsive and flexible digital practices that acknowledge linguistic and cultural diversity, thereby aligning with the goals of SDG 4 and SDG 10, ensuring equitable education for all. Importantly, DigCompEdu also promotes self-assessment and reflective practice, fostering teacher agency in aligning digital strategies with diverse learners’ needs and challenging educational inequalities. In doing so, it contributes to sustainable digital transformation while building equitable, inclusive, and context-sensitive educational ecosystems.

In European contexts, DigCompEdu has evolved from a descriptive framework to a practical tool for guiding teacher professional development and evaluation. Countries such as Spain, Portugal, and Turkey have systematically embedded DigCompEdu into national models (i.e., INTEF’s Common Digital Competence Framework for Teachers, DCSE, and many more) for assessing and supporting educators’ DC [

14,

25,

26]. These applications illustrate how the framework can be operationalized to structure training pathways, certification systems, and reflective practices. However, while such implementations highlight the scalability and policy relevance of DigCompEdu, they have tended to focus more on general digital teaching skills than on the nuanced challenges of multilingual and multicultural classrooms. This gap underscores the added value of pairing DigCompEdu with TPACK as the conceptual framework that describes how teachers integrate technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge into effective teaching. Whereas DigCompEdu provides measurable competence areas and developmental trajectories, TPACK contributes a practice-oriented understanding of how technology, pedagogy, and content intersect with contextual factors [

14]. Together, they form a comprehensive foundation for advancing quality and inclusive digital pedagogy in diverse classroom settings across Europe and beyond.

Complementing DigCompEdu, the TPACK model [

9,

19] provides a lens for understanding how technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge interact in practice. Conceived as a flexible, adaptive framework, TPACK is particularly valuable in multilingual and multicultural classrooms where technology can empower learners but may also reproduce inequalities. Recent refinements, such as the addition of Contextual Knowledge [

27], underscore how sociocultural and institutional conditions shape digital practices. Empirical evidence further illustrates TPACK’s exploitation in examining teachers’ self-perceived digital preparedness either in isolation [

28] or in combination with other models (like UTAUT) [

29]. In addition, research has applied TPACK in intercultural and linguistically diverse classrooms, demonstrating its use for fostering intercultural competence through technology-enhanced language learning [

26] and for promoting cross-cultural awareness in game-based learning environments [

30]. Durham [

28] highlights how TPACK supports linguistically responsive teaching in diverse school contexts, enabling technology to sustain language diversity while supporting multilingual learners’ academic development. Similarly, Huang [

31] examines the development of TPACK among trilingual teachers in Chinese ethnic minority regions, showing how it helps balance content delivery with multilingual instruction while affirming students’ cultural and linguistic identities. Collectively, these contributions extend TPACK well beyond its original scope, establishing it as a valuable framework for equitable and inclusive education and education for sustainability in culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms.

Both DigCompEdu and TPACK have shaped a wide body of research, each offering valuable insights into educators’ knowledge and practices. However, their combined use remains underexplored in empirical studies—particularly within multilingual and multicultural contexts through mixed methods designs. This gap is especially evident in public primary education, where teachers often report lower levels of DC and feel underprepared to design co-constructive digital environments or integrate tools for differentiation and student-led learning [

14,

32,

33,

34]. Addressing this gap, the present study focuses on in-service teachers in Greece and Cyprus, investigating their perceptions of DCs in multilingual and multicultural mainstream classrooms. By applying a dual framework within a mixed-methods approach, it identifies distinct competence profiles, explores the contextual and institutional factors shaping them, and highlights the need for differentiated, inclusive professional development aligned with broader sustainability goals.

1.2. Context of the Study

As previously noted, digital transformation has become a central priority across European education systems and beyond. Both Cyprus and Greece - countries experiencing rising (im)migrant student populations [

15,

16,

17] have taken steps to strengthen digital infrastructure and promote digital literacy in primary education, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic [

35,

36], as a tool for supporting and ensuring access to quality education. Initiatives such as Cyprus’s student device subsidy program [

37] and Greece’s Gigabit Connectivity Voucher Scheme [

38] have sought to reduce school–home digital divides.

Despite these efforts, empirical research on classroom-level integration of digital technologies in Cyprus and Greece remains limited. Most studies have addressed general aspects of differentiated instruction, often overlooking cultural and linguistic diversity via digital implementation, which now defines mainstream classrooms [

39,

40]. A notable exception is Christodoulidou and Sidiropoulou [

41], who explored teachers’ experiences with online instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet persistent challenges remain, particularly concerning educators’ self-perceived DC and their readiness to meet the needs of culturally and linguistically diverse learners [

41].

In both Cyprus and Greece, mainstream classrooms represent a critical context for understanding education for sustainability. While inclusive placements are designed to foster belonging and equitable participation [

42,

43,

44]. Research consistently shows that (im)migrant students face systemic barriers such as linguistic marginalization, limited academic support, and institutional pressures for rapid assimilation [

45,

46,

47]. Many teachers also report difficulty engaging students who speak languages other than the medium of instruction, often delegating responsibility for their inclusion to second language specialists or segregated programs [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

Such realities underscore that mainstream classrooms are not merely sites of instruction but also arenas where social cohesion, equity, and sustainability are negotiated. Effective digital pedagogy in these contexts has the potential to reduce inequalities, empower marginalized learners, and foster intercultural understanding—directly advancing SDG 4 and SDG 10. Conversely, failure to equip teachers with inclusive DCs risks reinforcing exclusion and undermining education for sustainability.

Responding to this complexity, the Re.Ma.C. project (Reinventing Mainstream Classrooms) was launched as an Erasmus+ initiative led by Frederick University (Cyprus), CARDET (Cyprus), Democritus University of Thrace (Greece), CESIE EST (Italy), SOS Malta, and the University of Algarve (Portugal). Re.Ma.C. is conceptualized as a blended learning framework emphasizing the intersection of technology, languages, and cultures [

54]. Drawing on interdisciplinary foundations in second language learning, intercultural pedagogy, multiliteracies, and digital learning design, the project addresses both teacher development and student engagement. Its instructional design is informed by the Community of Inquiry (CoI) model [

55,

56], the SAMR model [

57], and Laurillard’s Conversational Framework [

58,

59,

60], which structures interaction at student–student, student–teacher, and student–content levels.

This paper draws on the needs analysis phase of Re.Ma.C., which identifies gaps in educators’ DCs in primary mainstream classrooms increasingly shaped by linguistic and cultural diversity to inform the design of professional development modules that advance education for sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

A mixed-methods design was adopted to capture both general patterns and nuanced insights, thereby ensuring a comprehensive, context-sensitive understanding of digital readiness of teachers in primary multilingual and multicultural mainstream classrooms.

The quantitative component was based on a questionnaire developed for the project’s needs analysis. The DC section was conceptually grounded in the DigCompEdu. Responses from 146 teachers were analyzed in SPSS through descriptive statistics, cluster analysis, and Kruskal–Wallis H tests to identify distinct profiles of self-perceived DC and to examine how these profiles related to contextual variables.

The qualitative component drew open-ended responses from the same questionnaire. These were thematically coded using the extended TPACK framework. This lens facilitated an in-depth exploration of teachers’ beliefs, challenges, and classroom practices, particularly in relation to how digital pedagogy supports quality education (SDG4) and promotes inclusivity and equity (SDG10). In addition, open-ended responses were also used for Pearson correlation coefficient analysis (via NVivo) to identify patterns and relationships.

This integrated design enabled triangulation across methods, strengthening reliability, validity, and interpretive depth. The study was guided by two research questions, one with implications for pedagogical process and quality, and the other for the systemic-structural dimension of Quality Education:

How do teachers’ self-perceived digital competences reflect their readiness to integrate inclusive digital practices to enhance literacy in multilingual and multicultural mainstream classrooms?

What role do contextual factors, such as school infrastructure, training access, and student digital readiness, play in shaping teachers’ digital competence profiles?

By combining data-driven classification with in-depth teacher narratives, this approach provides a robust basis for informing professional development initiatives that are both aligned with the DigCompEdu framework and responsive to the realities of diverse classroom contexts.

2.1. Participants

The study employed a non-probability convenience sample consisting of 146 in-service teachers from Cyprus and Greece who voluntarily participated in the needs analysis phase before Re.Ma.C. Erasmus+ KA2 training seminars. The participants were in-service teachers working in mainstream classrooms with linguistically and culturally diverse student populations. Most were women (91.1%), reflecting sex trends in teaching in Greece and Cyprus. In terms of age, 53.4% were 35–44 years old, 20.5% were 45–54, 17.1% were 25–34, and 8.2% were 55–64, with only 0.7% under 24. Geographically, 52.7% of teachers were based in Cyprus and 45.9% in Greece, while two reported teaching temporarily abroad. The most frequently taught subject was Greek language (80.8%), followed by Mathematics (56.2%), Environmental studies (35.6%), and History (26.7%). A smaller share taught ICT, Arts, Religion, or other disciplines. The sample was highly qualified: 54.8% held a master’s degree in education-related fields, 24.0% a bachelor’s degree, 9.6% a master’s in teaching Greek as a second language, and 6.2% a PhD in education or a related area. The remainder held specialized or a combination of diplomas. Teaching experience was evenly distributed, with 20.5% having 0–5 years, while an equal percentage had been teaching for 16-20 years, 17.8% 11–15 years, and equal shares (14.4%) reporting 21-25 or 26+ years. Employment status varied, with 70.5% permanent staff, 13% substitutes, 5.5% hourly-paid, and 2.1% on fixed-term contracts. The remainder was holding other statuses (i.e. volunteers etc.). Classroom diversity also varied: 27.4% of teachers reported that 75% or more of their students were of (im)migrant origin, 14.4% reported 51–75%, and 16.4% reported 11–25%. Smaller proportions had fewer than 10% (12.3%) or 26–49% (11.6%), while 7.5% reported that half their students were (im)migrants. Only a few reported none.

2.2. Instrument

Data was collected using a custom-designed questionnaire developed for the Re.Ma.C. project’s needs analysis. The instrument reflected sociocultural and institutional contexts of Southern Europe, while assessing teachers’ competencies across three domains: (a) teaching Greek as a second language, (b) intercultural education, and (c) DC. The final instrument included 30 items. The ten types of digital tools were informed by the DigCompEdu framework and adapted to the realities of multilingual, diverse mainstream classrooms in Greece and Cyprus, specifically drawing on teacher training material developed by the Computer Technology Institute and Press “DIOPHANTUS.” This section contained 10 Likert-scale items (1 = Not at all to 5 = Very well) covering: (1) general digital devices use, (2) general purpose software, (3) collaboration and communication tools, (4) simulations, (5) programming tools, (6) dynamic creation tools, (7) multimodal content creation tools, (8) artistic creation tools, (9) digital games, and (10) robotics.

Instrument development followed a co-constructive process involving more than ten international experts from the project’s consortium, including specialists in digital learning, intercultural pedagogy, and second-language learning. Items were adapted from validated tools and newly created, refined through iterative expert feedback (consortium partners), and piloted with small teacher samples in the five participating countries. Pilot feedback informed revisions to wording, layout, and clarity.

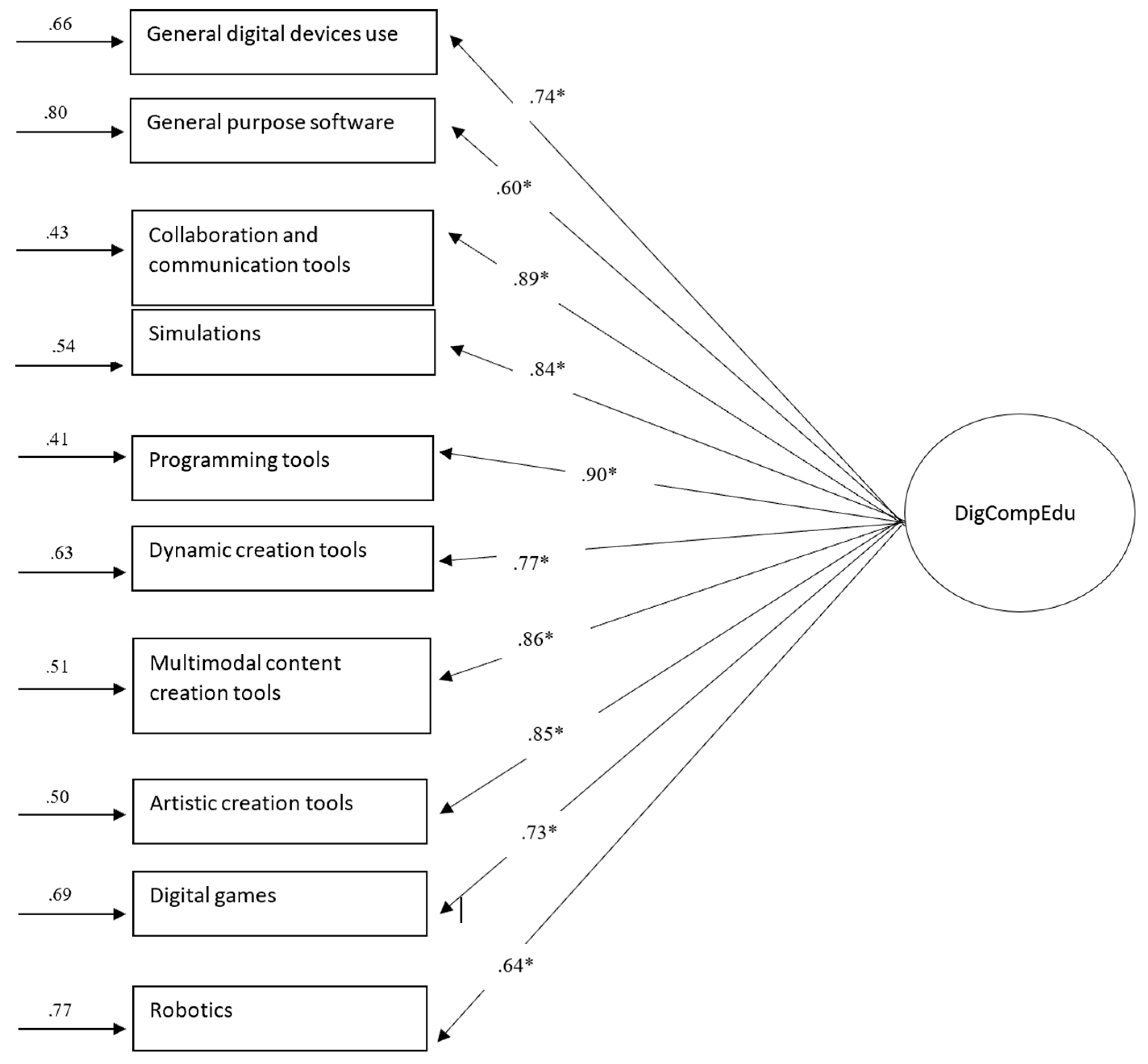

To evaluate the instrument’s structure, we conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation method [

61]. Model fit was assessed using widely accepted indices: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ .90 [

62], and RMSEA and SRMR values between 0 and 0.08 [

63,

64].The CFA indicated a good model fit (χ²(401) = 911.67, p < .001, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .04), supporting the three-factor structure. Factor loadings ranged from .44 to .90, indicating moderate to high associations between items and their respective latent constructs. For the purposes of the present study, analyses focused on the DigCompEdu. Item loadings on this factor ranged from .60 to .90 (see

Figure 1), indicating substantial contributions of the respective statements to the latent construct.

Ethical safeguards were observed since the questionnaire included information on study aims, voluntary participation, anonymity, and data use. Submission of responses constituted informed consent.

2.3. Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis was conducted in SPSS (v. 27). A hierarchical agglomerative cluster analysis was performed to classify participants into homogeneous groups based on their self-perceived DCs [

65]. The proximity between cases was calculated using the Squared Euclidean distance metric, which is appropriate for ordinally coded data under the assumption of approximately equal spacing between categories. Ward’s method was applied as the clustering algorithm.

Subsequently, the Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to investigate whether statistically significant differences existed among the clusters in overall DC scores [

66]. The resulting clusters were then used as the basis for further qualitative and comparative exploration, offering insight into how patterns of DC intersect with teachers’ demographic profiles and potentially reflect broader pedagogical orientations.

To complement the quantitative analysis using SPSS and deepen the interpretation of the self-perceived DC profiles, participants’ open-ended responses were analyzed using a two-phase approach. Qualitative analysis of open-ended responses first followed Braun and Clarke’s [

67,

68] six-phase thematic analysis (using ‘In Vivo coding’). Codes were generated inductively and refined into themes aligned with the extended TPACK framework [

27], emphasizing how technological, pedagogical, content, and contextual concerns intersect in multilingual, diverse mainstream classrooms. To further explore the internal structure and relationships among the identified codes, a cluster analysis was conducted using the Cluster Analysis Wizard function in NVivo (v14). Specifically, Pearson’s correlation coefficient analysis [

69] was used to cluster by word similarity to identify the degree of co-occurrence and pattern similarity among coded responses. This method was selected to detect linear associations between items, offering insights into how specific themes tended to cluster together within and across DC profiles. The resulting horizontal dendrograms visually illustrate how teachers’ responses group around shared concerns and priorities, supporting and extending the thematic findings.

The integration of statistical classification, thematic interpretation, and code clustering ensured methodological triangulation and strengthened the robustness of the findings. This approach allowed us to capture individual perceptions of DC and the broader pedagogical orientations underlying digital practices in linguistically and culturally diverse mainstream classrooms. In doing so, the study provides a solid evidence base for designing professional development initiatives that are responsive to context and aligned with the principles of sustainability reflected in SDG 4 and SDG 10.

3. Results

This section presents the findings of the study as they relate to the two research questions, drawing on both quantitative and qualitative datasets.

3.1. Cluster Formation

To examine whether teachers could be meaningfully categorized into distinct groups based on their self-perceived DCs, both the Agglomeration Schedule and the dendrogram were examined. The decision to retain a three-cluster solution was guided by both statistical and substantive considerations. Statistically, inspection of the Agglomeration Schedule revealed a pronounced jump in the agglomeration coefficient between Stages 297 and 298 (from 580.39 to 20,754.98), suggesting that the merger from three to two clusters would combine highly dissimilar groups. Such a large increase is a recognized indicator that the preceding number of clusters represents an optimal stopping point in hierarchical clustering [

70,

71].

From a substantive standpoint, the three-cluster solution yielded group profiles that were both distinct and interpretable in terms of participants’ self-perceived DCs. Cluster 1 comprised teachers with consistently high self-assessed competence across all ten areas, Cluster 2 included teachers with moderate levels of confidence, and Cluster 3 encompassed those with markedly lower self-perceptions. These patterns align with theoretical expectations regarding heterogeneity in DC within educational populations [

15,

72] and provide a meaningful basis for subsequent qualitative exploration and targeted professional development design.

The statistical validation of the cluster was provided by the results of the Kruskal–Wallis H test, which confirmed differences among the three clusters. Results confirmed a highly significant difference in overall DC scores (χ²(2) = 116.987, p < .001). The magnitude of the mean rank differences (121.51 vs. 68.65 vs. 20.78) provides additional empirical support for the distinctiveness of these groups. This convergence of statistical evidence and conceptual clarity reinforced the decision to adopt the three-cluster model.

3.2. Interpretation of Clusters

To complement the quantitative findings, open-ended responses were thematically analyzed using ‘in Vivo’ coding within the extended TPACK framework. This framework incorporates the seven core knowledge domains—Technological Knowledge (TK), Pedagogical Knowledge (PK), Content Knowledge (CK), and their intersections (TPK, TCK, PCK, TPACK), Contexts together with Contextual Knowledge (XK), which emphasizes the situated expertise educators draw upon to address institutional, cultural, and sociolinguistic realities of multilingual and multicultural classrooms [

27]. The following sections present teacher profiles-specific themes in order of prevalence, from the most frequently mentioned to the less common concerns. To illustrate patterns and relationships among responses, horizontal dendrograms generated through Pearson correlation analysis are also included for each cluster.

3.2.1. Interpretation of Cluster 1

Teachers in

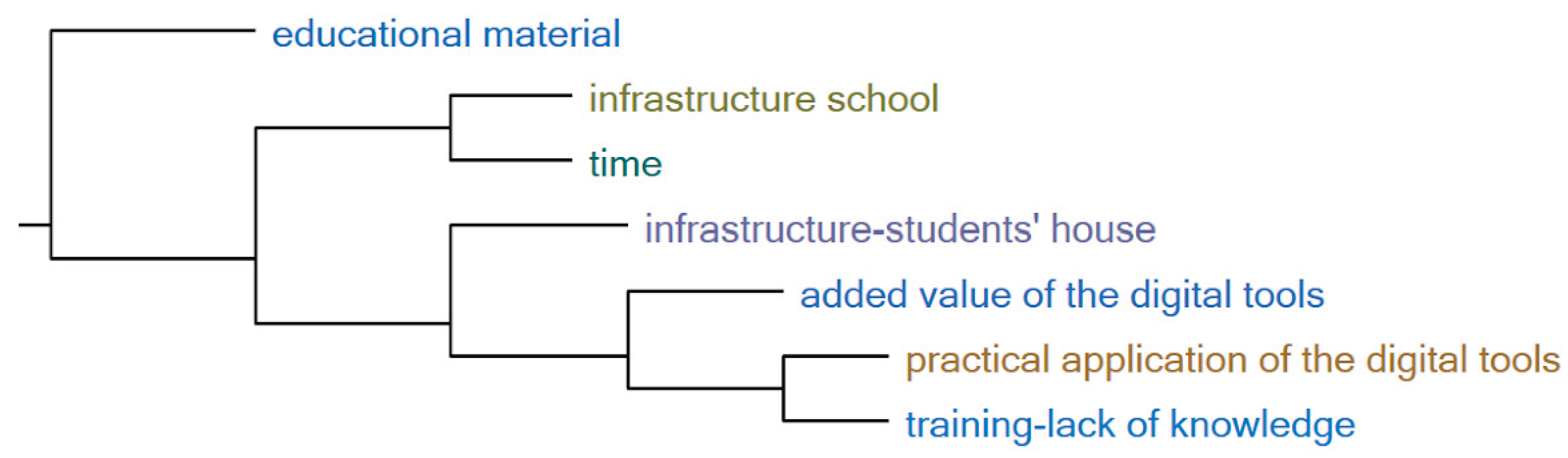

Cluster 1 demonstrated the strongest digital confidence, reporting proficiency with a wide range of tools and practices. Qualitative responses further indicated that these educators consider sustained, specialized, and context-sensitive professional development (PD) the most essential condition for embedding technology effectively in multilingual and multicultural classrooms. The dendrogram (

Figure 2) highlights PD as a central theme, clustered with four other interconnected themes (based on the main clade of the dendrogram) derived from six terminal ends (leaves), while one leaf (“educational material”) appeared as an isolated, simplicifolious theme.

Training and knowledge gaps. Teachers in this cluster called for training that is not only aligned with emerging technologies but also directly responsive to the realities of multilingual and diverse mainstream classrooms. One teacher noted:

“I wish I could use programs that allow translation into the possible mother tongues of my students (at least for younger ages, for basic things like understanding rules or explaining instructions) in case I cannot communicate with them.”

This reflects needs at the intersection of TPK and TCK, but also demonstrates the importance given to Contextual Knowledge (XK), highlighting both technical fluency, content awareness for context-sensitive implementation. Moreover, it aligns with the cluster of ‘training–lack of knowledge’, ‘practical application of digital tools’, and ‘added value of digital tools’ (

Figure 2), reflecting a critical stance toward the effectiveness and pedagogical utility of technology without sufficient support.

Systemic infrastructure barriers. Despite their competence, teachers frequently cited poor school infrastructure as a substantial obstacle. A smaller number also mentioned home access inequalities for (im)migrant students and limited lesson time:

“The presence of appropriate technical equipment and internet connectivity in teaching spaces.”

This points to structural constraints, mapped within the Contexts domain of the TPACK framework, that persist irrespective of individual teacher competence or willingness.

Figure 2 shows that ‘school infrastructure’, ‘home infrastructure’, and ‘time’ form a sub-cluster, indicating that these constraints co-occur as a constellation of contextual limitations.

Practical application challenges. Several teachers expressed uncertainty about how to effectively apply digital tools in linguistically and culturally diverse mainstream classroom settings. One teacher candidly shared:

“I don’t know how to use certain interesting and useful applications. Of course, I do know in theory how digital technologies should be used in teaching practices.”

This reflects a theory–practice gap: high TK but weaker enactment of integrated TPACK. In the dendrogram (

Figure 2), this is evident in the proximity between ‘training’–‘lack of knowledge’ and ‘practical application of digital tools’.

Educational materials. Only a small number of responses mentioned a lack of educational materials. In

Figure 2, educational material appears as the most distant node (simplicifolious/single leafed), confirming it was not a major concern compared to infrastructure or training. This suggests that for this group, the main barriers are structural and pedagogical, not logistical.

The qualitative findings from this cluster seem to demonstrate that teachers with strong TK, TPK, and TCK, with glimpses of mature TPACK, but their practice seems to be constrained by overall systemic barriers, and translation challenges (theory vs. practice). The dendrogram (

Figure 2) reinforces this duality, revealing two interlinked constellations: (a)

Training–application–added value: signalling the PD needs of even advanced teachers, (b)

Infrastructure–home access–time: showing the systemic bottlenecks beyond teacher control.

3.2.2. Interpretation of Cluster 2

Teachers in

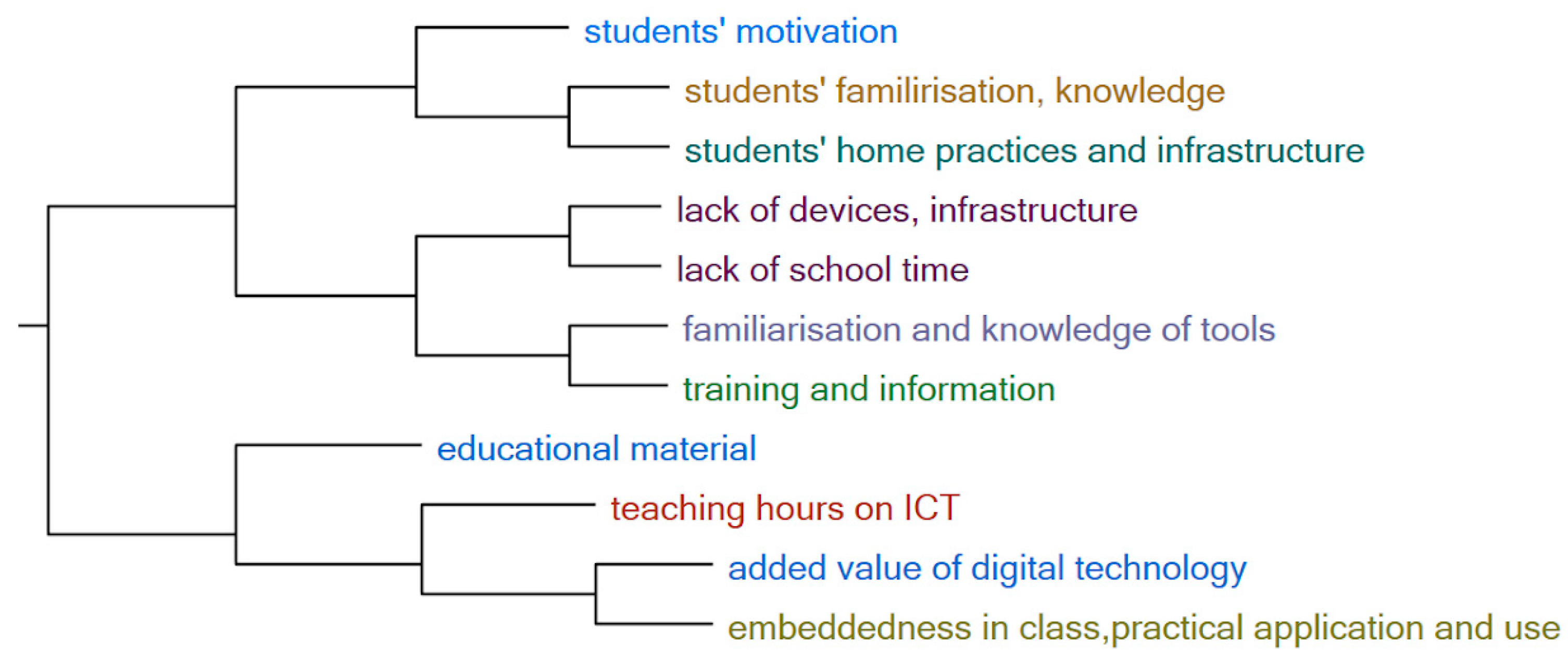

Cluster 2 reported moderate self-perceived DC. Five interconnected themes out of the two main clades emerged from the following 11 leaves, which align with the extended TPACK framework (

Figure 3).

Familiarisation with tools for multilingual pedagogy. A dominant theme was the need for greater familiarization with digital tools and their pedagogical application in multilingual, multicultural mainstream classrooms:

“I have not organized a list of technology links to use in teaching Greek as a second or foreign language.”

This points to a shortfall in TCK, adapting digital resources for schooling language teaching purposes, and a reliance on XK to align choices with learners’ sociolinguistic needs. Codes for ‘familiarization/knowledge of tools’ cluster with ‘training/information’, indicating teachers perceive tool repertoire growth as inseparable from structured learning opportunities (

Figure 3).

Ongoing, broad-based professional development. Teachers articulated a generalised demand for continuous PD, less specialised than Cluster 1, more about sustained exposure and updating:

“To be able to stay informed about new digital technologies and tools that I can use in my teaching.”

This reflects the need to strengthen TK and PK, and their intersection TPK, before moving to more advanced, context-specific designs. ‘Training/information’ clusters with ‘familiarisation’ and with systemic constraints (see theme below), suggesting that teachers view PD as mutually reinforcing with the conditions that allow it to matter. These conditions align with the broader contextual factors captured by XK.

Systemic and infrastructural constraints. While less urgent than in Cluster 1, teachers flagged device scarcity and limited time:

“There are not enough available devices.”

These constraints sit squarely in Contexts and XK, conditioning how any TPACK can be enacted. ‘Lack of devices’ and ‘lack of school time’ cluster with ‘training/familiarization’, which were validated by the Pearson correlation analysis conducted, where these factors are shown to be conceptually linked and frequently co-occurring in the dataset.

From sporadic use to pedagogical embedding. Teachers recognized the need to move beyond ad hoc tool use toward embedded, curriculum-aligned integration:

“A balance between use and optimal effectiveness.”

This reflects an emerging TPACK orientation from teachers’ perspective, yet signals gaps in turning principles into routine practice. The clade combining ‘embeddedness in class/practical application’, ‘added value of digital technology’, and ‘teaching hours on ICT’ shows teachers tie effective integration to both didactic design (TPK/TPACK) and institutional conditions (time allocation). These elements, visualized in dendrogram 2, collectively point to a growing recognition of the importance of sustained, instructional use of technology rather than ad hoc application.

Student readiness and uneven digital ecologies. Teachers described contradictory learner profiles, revealing uneven digital experience:

“Many children are not familiar with these kinds of technologies.”

“Students have access to digital literacy practices.”

It seems that some teachers are reading classroom integration through the lens of learners’ home practices, motivation, and prior knowledge, an extension of Contexts focused on student ecologies. ‘Students’ motivation’, ‘students’ familiarization/knowledge’, and ‘students’ home practices/infrastructure’ form a distinct sub-clade, indicating teachers perceive these as co-occurring determinants of what is feasible in class.

Cluster 2 teachers seem to be portrayed as open but constrained practitioners. Their TPACK enactment is partial: TK/TCK/TPK are present but fragmented, and often contingent on system enablers (Contexts and Contextual Knowledge), time, and students’ digital ecologies.

Figure 3 makes visible three interlocking constellations—(i) familiarization ↔ training, (ii) infrastructure/time ↔ training, (iii) embedding ↔ added value ↔ ICT hours—plus a learner-ecology cluster. Advancing this group requires sustainable PD co-designed with equitable infrastructure and learner-centred scaffolds.

5.2.3. Interpretation of Cluster 3

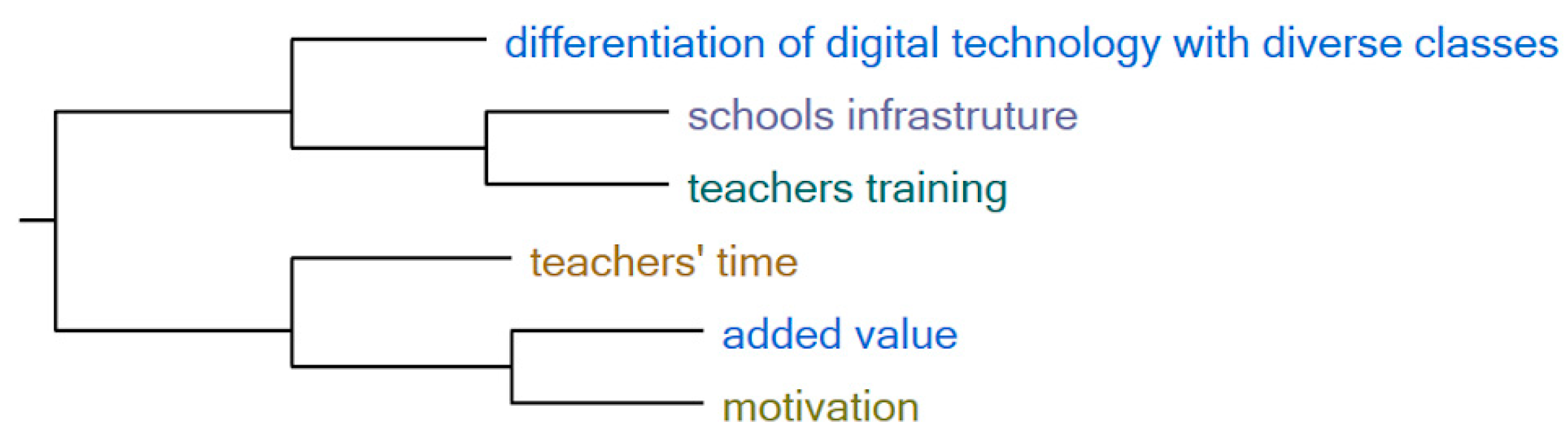

Teachers in Cluster 3 reported the lowest levels of self-perceived DC, with responses seemingly dominated by external barriers and structural dependencies. While some articulated inclusive intentions, their capacity to enact TPACK in practice is presented as rather limited. The analysis yielded five interrelated themes, which cluster into two larger clades (see

Figure 4) from the 6 leaves available.

Infrastructure is a prerequisite. The most frequently cited limitation was the absence of basic infrastructure, computers, internet, and projectors, viewed as a non-negotiable precondition:

“If the basic equipment is missing—namely, a computer, internet access, and then a projector—there is no possibility for implementation.”

Here, TK is curtailed by systemic deficits in Contexts. Teachers cannot advance beyond awareness because the material conditions for practice are absent. ‘School infrastructure’ clusters tightly with ‘teacher training’ and ‘differentiation of digital technology’, underscoring that teachers see hardware/software access as inseparable from the capacity to learn and innovate pedagogically.

Generalized call for training. Training needs were also frequently mentioned, though framed in broad, generic terms:

“Ongoing training of teachers is needed for the application of digital technologies in teaching.”

Unlike Cluster 2, where PD needs were tied to specific practices (e.g., embedding or familiarization), Cluster 3 teachers expressed low-resolution training demands. This signals underdeveloped TPK/TPACK, where the link between tools, pedagogy, and context seems not yet to be conceptualized. ‘Teachers’ training’ is part of the strongest triad with ‘infrastructure’ and ‘differentiation of digital technology’, which may be reflecting teachers’ sense that without infrastructure, which was the most common concern, training feels abstract, and without training, differentiation is unachievable.

Differentiation for diverse classrooms. A smaller subset emphasized the need for differentiated digital environments to ensure participation by all learners:

“The support of a differentiated digital environment is necessary so that all students can participate.”

Though less common, this demonstrates glimpses of integrated TPACK thinking, linking PK, PCK, and TPK/TPACK in the service of inclusion. However, the rarity of such responses suggests this orientation remains aspirational rather than enacted. Its clustering with ‘infrastructure’ and ‘training’ suggests teachers understand differentiation as structurally contingent, meaning that perhaps they cannot realise inclusive pedagogy without resources and knowledge (

Figure 4).

Time is an overlooked but decisive factor. Teachers also reported that limited time was a significant impediment, not in terms of integrating tools creatively, but in finding time to organize or even locate useful digital materials. Time was seen not as a luxury for enhancement, but as a prerequisite still out of reach. ‘Teachers’ time’ clusters with ‘digital tools added value’ and ‘children’s motivation’, suggesting that when time is scarce, perceived benefits and students’ enthusiasm decline, producing a reinforcing cycle of underuse.

Limited references to added value and motivation. Finally, a few teachers mentioned student motivation and the added value of digital tools, though without detail. These remarks suggest an awareness of potential but a lack of strategies for implementation. This suggests early-stage TK/PK, with limited movement into TPACK. For these teachers, digital adoption seems to be still framed as desirable but impractical. ‘Added value’ and ‘motivation’ form a second clade with time, reinforcing that without sufficient time, recognition of value does not translate into use.

Cluster 3 represents teachers whose digital practices seem to be systemically constrained and pedagogically underdeveloped.

Figure 4 reveals two interconnected constellations (clades): (a) Structural dependency triad:

infrastructure ↔ training ↔ differentiation, showing that inclusive digital pedagogy is viewed as unattainable without resources and upskilling, (b) Feasibility triad:

time ↔ added value ↔ motivation, showing that practical and emotional feasibility strongly condition digital engagement. In TPACK terms, teachers in this cluster have fragmented TK/PK and limited TPACK integration, with Context and Contextual Knowledge overwhelmingly shaping what is possible. Addressing their needs requires sequenced, equity-driven interventions: (i) infrastructure provision, (ii) time allocation, (iii) basic PD, and (iv) gradual pedagogical differentiation.

4. Discussion

This study examined how in-service teachers in southern Europe (Greece and Cyprus) perceive their DCs in multilingual and multicultural mainstream classrooms, adopting DigCompEdu and TPACK as complementary lenses. The findings confirmed that self-perceptions of DC are not uniform but map onto three distinct readiness profiles, each with different implications for equity and sustainability in education.

4.1. RQ1: Self-Perceived DCs and Readiness

The quantitative analysis identified three statistically distinct clusters of teachers—high, moderate, and low self-perceived DC—mirroring patterns reported in other contexts [

2,

12]. Cluster 1 (high competence) displayed strong technical confidence and broad tool familiarity, but qualitative data revealed a persistent theory–practice gap: although these teachers demonstrated strong TK and emerging TPACK, they were less certain about transferring digital skills into linguistically diverse pedagogies. This confirms earlier work showing that technical proficiency does not automatically translate into pedagogical integration [

15]. For education for sustainability, this profile highlights the need for practice-oriented support to bridge knowledge and application.

Cluster 2 (moderate competence) reflected transitional readiness: participants showed openness to experimentation but required sustained PD and systemic support to enact digitally, multilingual, enhanced learning environments. Their responses point to partial TCK/TPK integration but gaps in embedding digital tools in everyday instruction, echoing similar “middle-stage” orientations identified elsewhere [

72]. This profile suggests that scaffolded, collaborative PD communities are essential to move teachers from sporadic tool use toward embedded, equity-focused, and digitally enhanced learning environment applications.

Cluster 3 (low competence) was characterized by limited digital confidence and heavy reliance on external enablers. These teachers often equated competence with basic operational skills, while expressing uncertainty about pedagogical applications—a finding consistent with studies showing educators in similar contexts prioritizing technical literacy over critical, inclusive digital pedagogy [

33]. From a sustainability perspective, this profile underscores how inequitable access to infrastructure and training deepens digital divides, limiting schools’ capacity to contribute to SDG 4 (quality education) and SDG 10 (reduced inequalities).

4.2. RQ2: Role of Contextual Factors

Across all clusters, contextual barriers—particularly inadequate infrastructure, insufficient or non-contextualized PD, uneven student access, and limited time—emerged as decisive in shaping teachers’ ability to enact DCs. These factors consistently clustered with training and pedagogical application codes, highlighting how structural inequalities directly mediate professional practice. Students’ linguistic diversity and digital readiness were frequently described as challenges rather than opportunities, underscoring the need for training that reframes diversity as an asset, in line with recent policy reports [

16,

17].

Cluster comparisons revealed a gradient of contextual dependence. Teachers in Cluster 1 acknowledged systemic constraints but treated them as secondary to PD, suggesting resilience and a primarily pedagogical orientation. Cluster 2 demonstrated the strongest context orientation, viewing training and infrastructure as mutually reinforcing and essential for growth. Cluster 3 placed contextual barriers at the centre: without systemic support, digital integration was perceived as unattainable. Taken together, these contrasts show that the contribution of digital pedagogy in the teaching and learning level of quality education cannot be achieved unless the systemic level is also met. Instead, interventions must be tailored to how teachers position contextual factors relative to their competence: advanced PD for Cluster 1, scaffolded opportunities for Cluster 2, and foundational support for Cluster 3.

Building on these findings, the study recommends continuous, collaborative, and context-sensitive PD explicitly aligned with equity and inclusion goals. This echoes for sustained, practice-oriented training rather than generic digital literacy programs [

33,

34]. Integrating DigCompEdu and TPACK within teacher education emerges not only as a pedagogical imperative but also as a response to systemic inequalities, positioning DC as a lever for advancing SDG 4 and SDG 10. Variability of teacher profiles highlights the inadequacy of one-size-fits-all approaches, aligning with global reports advocating differentiated, sustainable pathways [

16,

73]. Systemic investments in infrastructure, mentoring, and communities of practice are equally vital, echoing Zhou, Singh, and Kaushik’s [

74] argument that reducing the digital divide requires both resource provision and inclusive pedagogical frameworks. By situating digital readiness within institutional and cultural realities, this study provides actionable guidance for policymakers, school leaders, and teacher educators seeking to translate technological potential into inclusive, high-quality learning.

While this study provides valuable insights into teachers’ DCs in multilingual and multicultural mainstream classrooms in primary education, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The sample was limited to in-service teachers in Greece and Cyprus, making findings context-specific and not directly generalizable to other settings. Moreover, reliance on self-perception measures may not fully capture enacted practices and could be affected by social desirability bias [

14].

Future research should expand beyond southern Europe to examine whether similar competence profiles emerge across diverse educational systems. Longitudinal mixed-methods studies could track teachers’ movement between profiles over time, particularly when exposed to differentiated PD programs. Additionally, exploring how students’ own multilingual and digital practices can be leveraged as resources may help reposition diversity as an opportunity for sustainable pedagogy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K., N.E., and M.M.; methodology, N.K., N.E., M.M.; and S.S.; software, N.K. and S.S..; validation, N.K. and S.S..; . and C.K.; formal analysis, N.K. and S.S..; investigation, N.K., N.E., M.M., C.K. and S.S.; resources, N.K., N.E., M.M., and S.S; data curation, N.K., N.E., M.M., and S.S; writing—original draft preparation, N.K., N.E., M.M., C.K. and S.S; writing—review and editing, N.K., N.E., C.K. and S.S; visualization, N.K.; supervision, N.K.; project administration, N.K..; funding acquisition, N.K., N.E. and M.M.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union, grant number 2022-1-CY01-KA220-HED-000088107.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with general ethical research standards. All the participants were adults, informed about the study, and voluntarily agreed to participate in non-working hours.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of confidentiality and data protection considerations. Requests to access anonymized datasets should be directed to Nansia Kyriakou.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TPACK |

Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge |

| DigCompEdu |

Digital Competence Framework for Educators |

| TK |

Technological Knowledge |

| PK |

Pedagogical Knowledge |

| CK |

Content Knowledge |

| TPK |

Technological Pedagogical Knowledge |

| TCK |

Technological Content Knowledge |

| PCK |

Pedagogical Content Knowledge |

| XK |

Contextual Knowledge |

| PD |

Professional Development |

| DC |

Digital Competence |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

Appendix A

Section B: Teaching Students with Greek as a Second Language

(If there are students who have Greek as a second language in the mainstream classroom, I can...)

Teach the same linguistic phenomena in a different way

Design/apply activities to support oral comprehension

Design/apply activities to support oral production

Design/apply activities to support reading comprehension

Design/apply activities to support writing production

Use translanguaging practices

Teach grammar indirectly (form-focused instruction, strategies)

Teach vocabulary using strategies (e.g., metacognitive, social)

Teach language through school subjects (e.g., CLIL, various text types)

Focus on communication conventions (e.g., politeness, register, speech acts)

Open-ended: “What else concerns you about language teaching in general classrooms that include children with Greek as a second language?”

Section C: Intercultural Education Practices

(“I can organize lessons and school activities based on intercultural education values so that...”)

Intercultural education concerns everyone

Human rights are respected

Interaction and collaboration in intercultural settings are developed

All students contribute equally to group activities

Children understand when texts/ideas are culturally determined

Critical and analytical thinking is fostered

Conflicts are resolved democratically

Active listening and empathy are promoted

Active citizenship is promoted

Children understand that all language varieties have equal value and functionality

Open-ended: “What else concerns you in the multicultural and multilingual school environment (lessons, activities)?”

Section D: Digital Competence in Intercultural Education

(“I can use digital tools and applications for language and subject teaching in intercultural contexts, such as...”)

Mobile devices (e.g. tablets)

General software (e.g. MS Word, PowerPoint)

Collaborative tools (e.g. Google Docs, webpage translators)

Simulations (e.g. history maps, science experiments)

Programming environments (e.g. Scratch, NetLogo)

Dynamic manipulation tools (e.g. GeoGebra)

Multimodal material creation tools (e.g. Animoto, MindMeister, Timetoast)

Artistic creation tools (e.g. KidPix)

Educational digital games

Robotics technologies

Open-ended: “What else concerns you regarding the use of digital technologies, tools, and applications in your teaching?”

References

- UNICEF. Goal 4: Quality Education. UNICEF for every child: UNICEF DATA: Monitoring the situation of children and women. https://data.unicef.org/sdgs/goal-4-quality-education/ (accessed 2025-11-04).

- UNESCO. Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries. Sustainable Development Goals. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/inequality/ (accessed 2025-11-04).

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed 2025-08-10).

- Pigozzi, M. J. Quality Education: A UNESCO Perspective. In International Perspectives on the Goals of Universal Basic and Secondary Education; Cohen, J. E., Malin, M. B., Eds.; Routledge, 2009; pp 249–259. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. K. P. Multilingual Learners in Mainstream Classrooms. Innov. Crit. Issues Teach. Learn. 2021, 2 (1), 100–122. [Google Scholar]

- Redecker, C. European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu.; Publications Office, European Commission. Joint Research Centre.: LU, 2017.

- Asagar, M. S. Digital Competence in Education: A Comparative Analysis of Frameworks and Conceptual Foundations. Synergy Int. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2025, 2 (1), 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P. Considering Contextual Knowledge: The TPACK Diagram Gets an Upgrade. J. Digit. Learn. Teach. Educ. 2019, 35 (2), 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M. J.; Mishra, P.; Cain, W. What Is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)? J. Educ. 2013, 193 (3), 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2017/18: Accountability in Education—Meeting Our Commitments; UNESCO: Paris, 2017.

- Spante, M.; Hashemi, S. S.; Lundin, M.; Algers, A. Digital Competence and Digital Literacy in Higher Education Research: Systematic Review of Concept Use. Cogent Educ. 2018, 5 (1), 1519143. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, W.; Wan, Z.; Liu, M.; Xu, W. Bridging Self-Efficacy and Digital Competence: A Comprehensive Scoping Review of Teachers’ Readiness for the Digital Age. SAGE Open 2025, 15 (3), 21582440251363716. [CrossRef]

- Krumsvik, R. J. Teacher Educators’ Digital Competence. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 58 (3), 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revuelta-Domínguez, F.-I.; Guerra-Antequera, J.; González-Pérez, A.; Pedrera-Rodríguez, M.-I.; González-Fernández, A. Digital Teaching Competence: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14 (11), 6428. [CrossRef]

- European Education and Culture Executive Agency. Eurydice. Promoting Diversity and Inclusion in Schools in Europe.; Publications Office: LU, 2023.

- UNICEF. Country Office Annual Report 2023 Greece; Greece-2023-COAR; 2023; pp 1–8. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.unicef.org/media/152026/file/Greece-2023-COAR.pdf.

- ΥΠAΝ. Διαπολιτισμική αγωγή και εκπαίδευση. Υπουργείο Παιδείας, Aθλητισμού και Νεολαίας: Διεύθυνση Δημοτικής. https://www.moec.gov.cy/dde/diapolitismiki/statistika_dimotiki.html (accessed 2025-03-24).

- Prestridge, S. The Beliefs behind the Teacher That Influences Their ICT Practices. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58 (1), 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M. J. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. Voice Scholarsh. Educ. 2006, 108 (6), 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Bonilla, C. D. R.; Guerra-Arango, J. A.; Oviedo-Guado, D. A.; Murillo-Noriega, D. E. Inclusive Education through Technology: A Systematic Review of Types, Tools and Characteristics. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1527851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, D.; Méndez, M.; Anguita, J. M. Digital Teaching Competence in Teacher Training as an Element to Attain SDG 4 of the 2030 Agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14 (18), 11387. [CrossRef]

- Rončević, K.; Rieckmann, M. Education for Sustainable Development and Inclusive Education with Particular Consideration of Learners with Special Needs: A Scoping Literature Review. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1593060. [CrossRef]

- Vuorikari, R.; Punie, Y.; Carretero, S.; Van den Brande, G. DigComp 2.1: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with Eight Proficiency Levels and Examples of Use.; Publications Office, European Commission. Joint Research Centre.: LU, 2017.

- Vuorikari, R.; Kluzer, S.; Punie, Y. DigComp 2.2, The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens: With New Examples of Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes.; Publications Office, European Commission. Joint Research Centre.: LU, 2022.

- Prieto-Ballester, J.-M.; Revuelta-Domínguez, F.-I.; Pedrera-Rodríguez, M.-I. Secondary School Teachers Self-Perception of Digital Teaching Competence in Spain Following COVID-19 Confinement. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11 (8), 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzer, E.; Koc, M. Teachers’ Digital Competency Level According to Various Variables: A Study Based on the European DigCompEdu Framework in a Large Turkish City. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29 (16), 22057–22083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petko, D.; Mishra, P.; Koehler, M. J. TPACK in Context: An Updated Model. Comput. Educ. Open 2025, 8, 100244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, C. Centering Equity for Multilingual Learners in Preservice Teachers’ Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK). J. Teach. Educ. 2024, 75 (3), 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viberg, O.; Mavroudi, A.; Khalil, M.; Bälter, O. Validating an Instrument to Measure Teachers’ Preparedness to Use Digital Technology in Their Teaching. Nord. J. Digit. Lit. 2020, 15 (1), 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jupit, A.; Minoi, J.; Arnab, A.; Yeao, A. Cross-Cultural Awareness in Game-Based Learning Using a TPACK Approach. In Designing for Global Markets 10; Product & Systems Internationalisation Inc, 2011; pp 31–49.

- Huang, J. The Development of TPACK for Trilingual Teachers in Chinese Ethnic Minority Regions. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2022, 16 (1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, J.; Garay, U.; Tejada, E.; Bilbao, N. Self-Perception of the Digital Competence of Educators during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Analysis of Different Educational Stages. Sustainability 2020, 12 (23), 10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouseti, A.; Lakkala, M.; Raffaghelli, J.; Ranieri, M.; Roffi, A.; Ilomäki, L. Exploring Teachers’ Perceptions of Critical Digital Literacies and How These Are Manifested in Their Teaching Practices. Educ. Rev. 2024, 76 (7), 1751–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, A. C.; Santos, A. I.; Meirinhos, M. Digital Competence for Pedagogical Integration: A Study with Elementary School Teachers in the Azores. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14 (12), 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasopoulou, E.; Tsagri, A.; Mitroyanni, E. Transforming Greek Primary Education through Information Systems: Trends and Challenges. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2025, 51 (6), 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deputy Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digital Policy. Digital Cyprus 2025; Rebublic of Cyprus, 2025. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.gov.cy/app/uploads/sites/13/2024/04/Digital-Strategy-2020-2025.pdf.

- ΥΠAΝ. Επιχορήγηση για Aγορά Ταμπλέτας / Φορητού Hλεκτρονικού Υπολογιστή. https://www.moec.gov.cy/2024_2025_epichorigisi_agora_laptop_tablet.html.

- Ελληνική Δημοκρατία. Gigabit Connectivity Voucher Scheme. https://www.gov.gr/en/ipiresies/epikheirematike-drasterioteta/eniskhuse-epikheireseon/kouponi-sundesimotetas-gigabit-gigabit-connectivity-voucher-scheme.

- Kasinidou, M.; Kleanthous, S.; Otterbacher, J. Cypriot Teachers’ Digital Skills and Attitudes towards AI. Springer Science and Business Media LLC August 1, 2024. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4662547/v1. [CrossRef]

- Perifanou, M.; Economides, A. A.; Tzafilkou, K. Teachers’ Digital Skills Readiness During COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. IJET 2021, 16 (08), 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulidou, P.; Sidiropoulou, C. Teachers’ Experiences of Online/Distance Teaching and Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Mainstream Classrooms with Vulnerable Students in Cyprus. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14 (2), 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, C. R.; Westmont, C. M. Comparative Effects of Belongingness on the Academic Success and Cross-Cultural Interactions of Domestic and International Students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2014, 38, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachner, M. K.; He, J.; Heizmann, B.; Van De Vijver, F. J. R. Acculturation and School Adjustment of Immigrant Youth in Six European Countries: Findings from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J.; Szelei, N.; Eloff, I.; Acquah, E. Together or Separate? Tracing Classroom Pedagogies of (Un)Belonging for Newcomer Migrant Pupils in Two Austrian Schools. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1301415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. Intercultural Education and Academic Achievement: A Framework for School-Based Policies in Multilingual Schools. Intercult. Educ. 2015, 26 (6), 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J.; Mirza, R.; Stille, S. English Language Learners in Canadian Schools: Emerging Directions for School-Based Policies. TESL Can. J. 2012, 29, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdusamatov, K.; Babajanova, D.; Egamberdiev, D.; Xodjiyev, Y.; Tukhtaev, U.; Yusupov, N.; Shoislomova, S. Challenges Faced by Migrant Students in Education: A Comprehensive Analysis of Legal, Psychological, and Economic Barriers. Qubahan Acad. J. 2025, 4 (4), 330–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, S. K. Teachers’ Beliefs About English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom: A Review of the Literature. Int. Multiling. Res. J. 2011, 5 (2), 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R. M.; Falcón, I. G.; Permisán, C. G. Teacher Beliefs and Approaches to Linguistic Diversity. Spanish as a Second Language in the Inclusion of Immigrant Students. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 90, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajic, D.; Bunar, N. Do Both ‘Get It Right’? Inclusion of Newly Arrived Migrant Students in Swedish Primary Schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2023, 27 (3), 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, A. M. Introduction to “Preparation and Development of Mainstream Teachers for Today’s Linguistically Diverse Classrooms. ” Educ. Forum 2018, 82 (2), 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M. Bridging the Gap: Preservice Teachers and Their Knowledge of Working With English Language Learners. TESOL J. 2013, 4 (1), 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsiaki, M.; Kyriakou, N.; Kyprianou, D.; Giannaka, C.; Hadjitheodoulou, P. Washback Effects of Diagnostic Assessment in Greek as an SL: Primary School Teachers’ Perceptions in Cyprus. Languages 2021, 6 (4), 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakou, N.; Mitsiaki, M.; Eteokleous, N.; Xeni, E.; Neophytou, R.; Ioannidou, Z. Advancing Sustainable Mainstream Classrooms: The European Project Re.Ma.C. In Proceedings of the Learning Innovations Summit 2024: Unveiling the future of learning and artificial intelligence.; Vrasidas, P., Mangina, E., Avraamidou, L., Aristidou, X., Eds.; Springer Nature, in press.

- Garrison, D. R.; Arbaugh, J. B. Researching the Community of Inquiry Framework: Review, Issues, and Future Directions. Internet High. Educ. 2007, 10 (3), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Reyes, D. 20 Years of the Community of Inquiry Framework. TechTrends 2020, 64 (4), 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puentedura, R. R. SAMR and TPCK: A Hands-on Approach to Classroom Practice. Hipassus 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Laurillard, D. Rethinking University Teaching, 2nd ed.; Routledge, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Laurillard, D. Learning through Collaborative Computer Simulations. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 1992, 23 (3), 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurillard, D. Thinking about Blended Learning. Dec. Pap. Think. Resid. Programme R. Flem. Acad. Belg. Sci. Arts 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov, T.; Marcoulides, G. A. A First Course in Structural Equation Modeling.; Lawrence Erlbaun Associates Inc., 2000.

- Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press, 2005.

- Bentler, P. M.; Bonett, D. G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88 (3), 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R. P.; Ho, M.-H. R. Principles and Practice in Reporting Structural Equation Analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7 (1), 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P. J. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis, 1st ed.; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; Wiley, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Field. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA handbook of research methods in psychology; Cooper, H., Camic, P. M., Long, D. L., Panter, A. T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K. J., Eds.; Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, 2012; Vol. 2, pp 57–71.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3 (2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVIVO 14 (Windows). Cluster analysis diagrams. https://help-nv.qsrinternational.com/14/win/Content/vizualizations/cluster-analysis.htm.

- Everitt, B.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis, 5th ed.; Wiley, 2011.

- Hair, J. F.; Black, W. C.; Babin; Anderson, R. E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning, 2019.

- Yang, L.; Martínez-Abad, F.; García-Holgado, A. Exploring Factors Influencing Pre-Service and in-Service Teachers’ Perception of Digital Competencies in the Chinese Region of Anhui. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27 (9), 12469–12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency. Eurydice. Integrating Students from Migrant Backgrounds into Schools in Europe: National Policies and Measures.; Publications Office: LU, 2019.

- Zhou, Y.; Singh, N.; Kaushik, P. D. The Digital Divide in Rural South Asia: Survey Evidence from Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2011, 23 (1), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).