Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

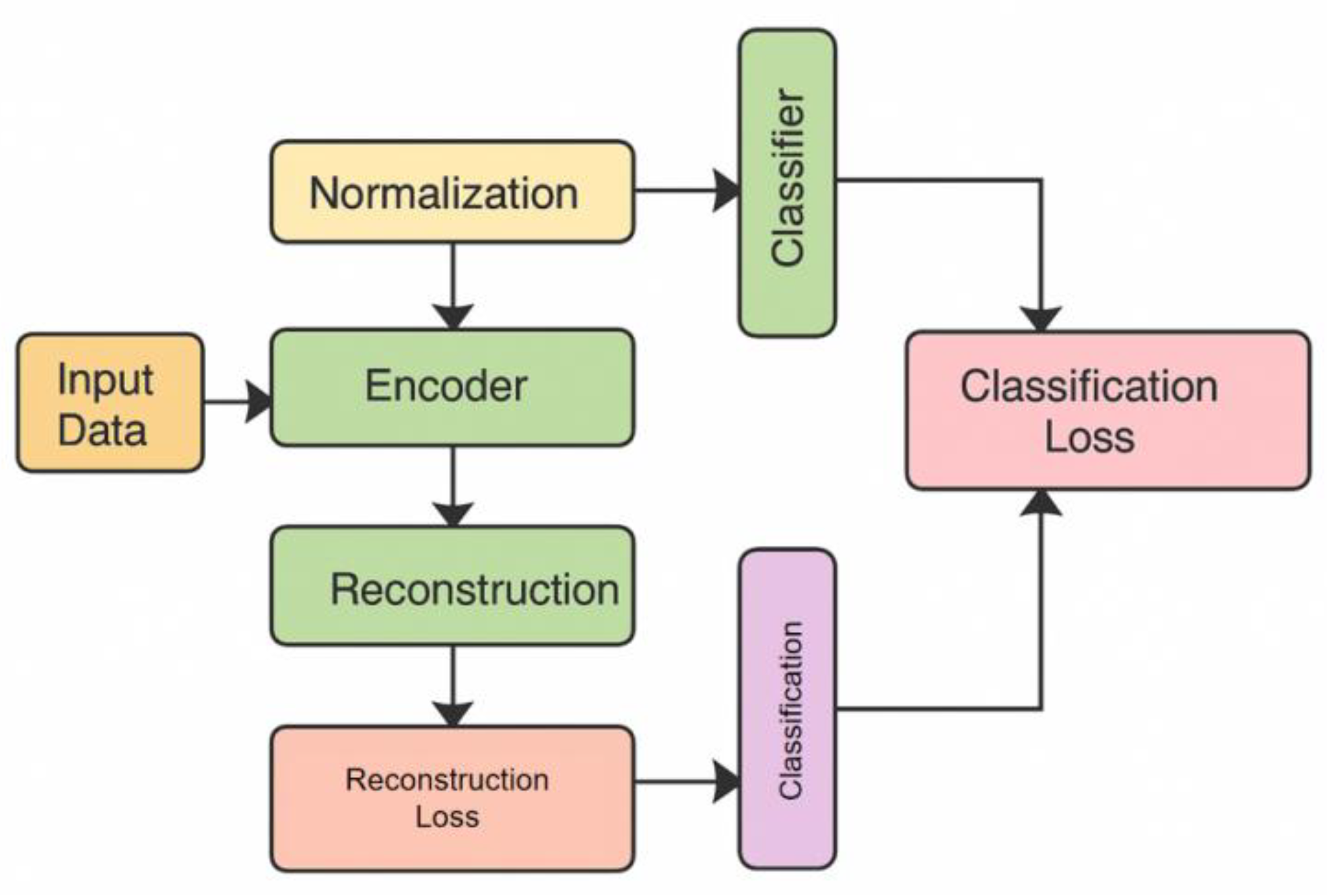

3. Method

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Dataset

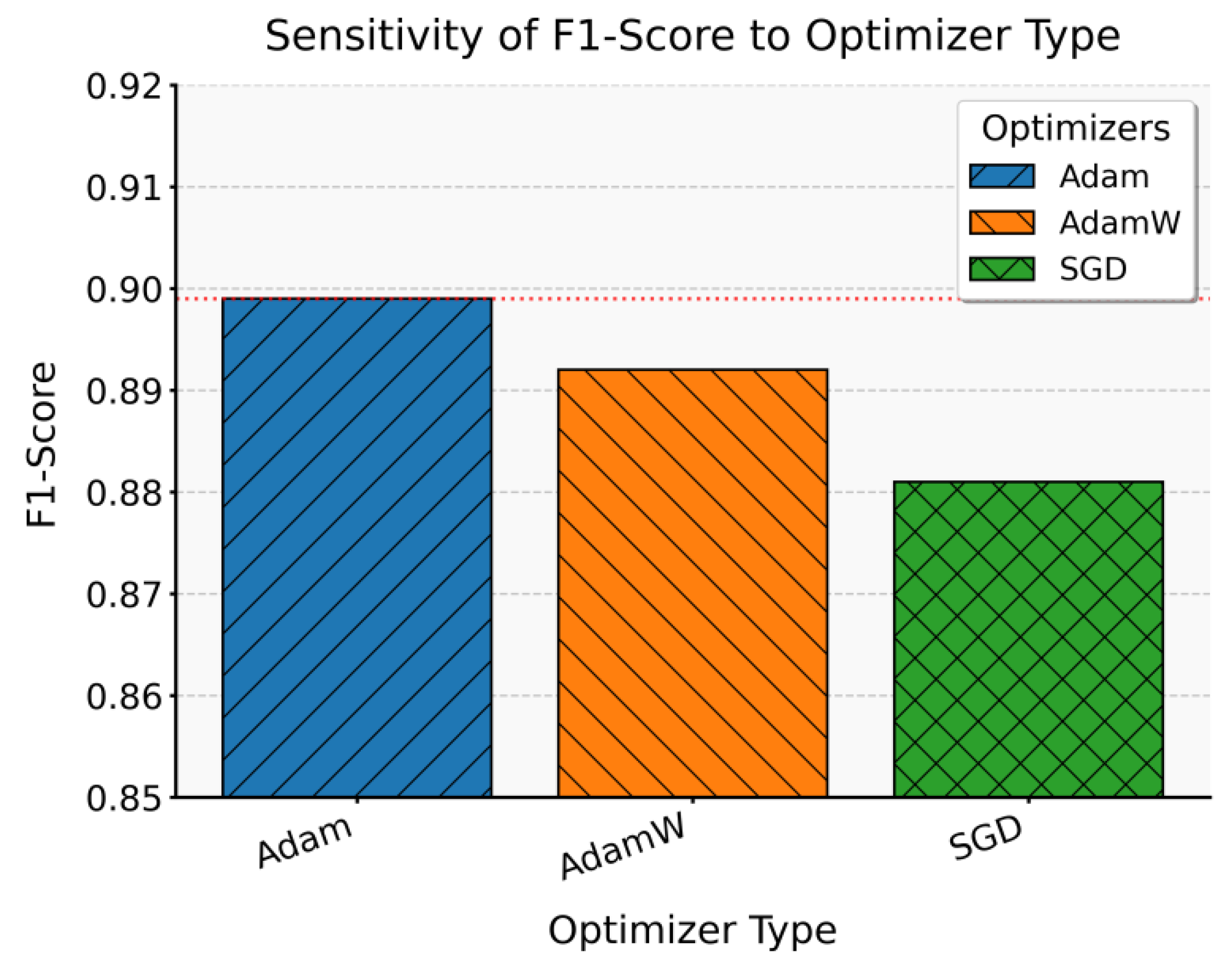

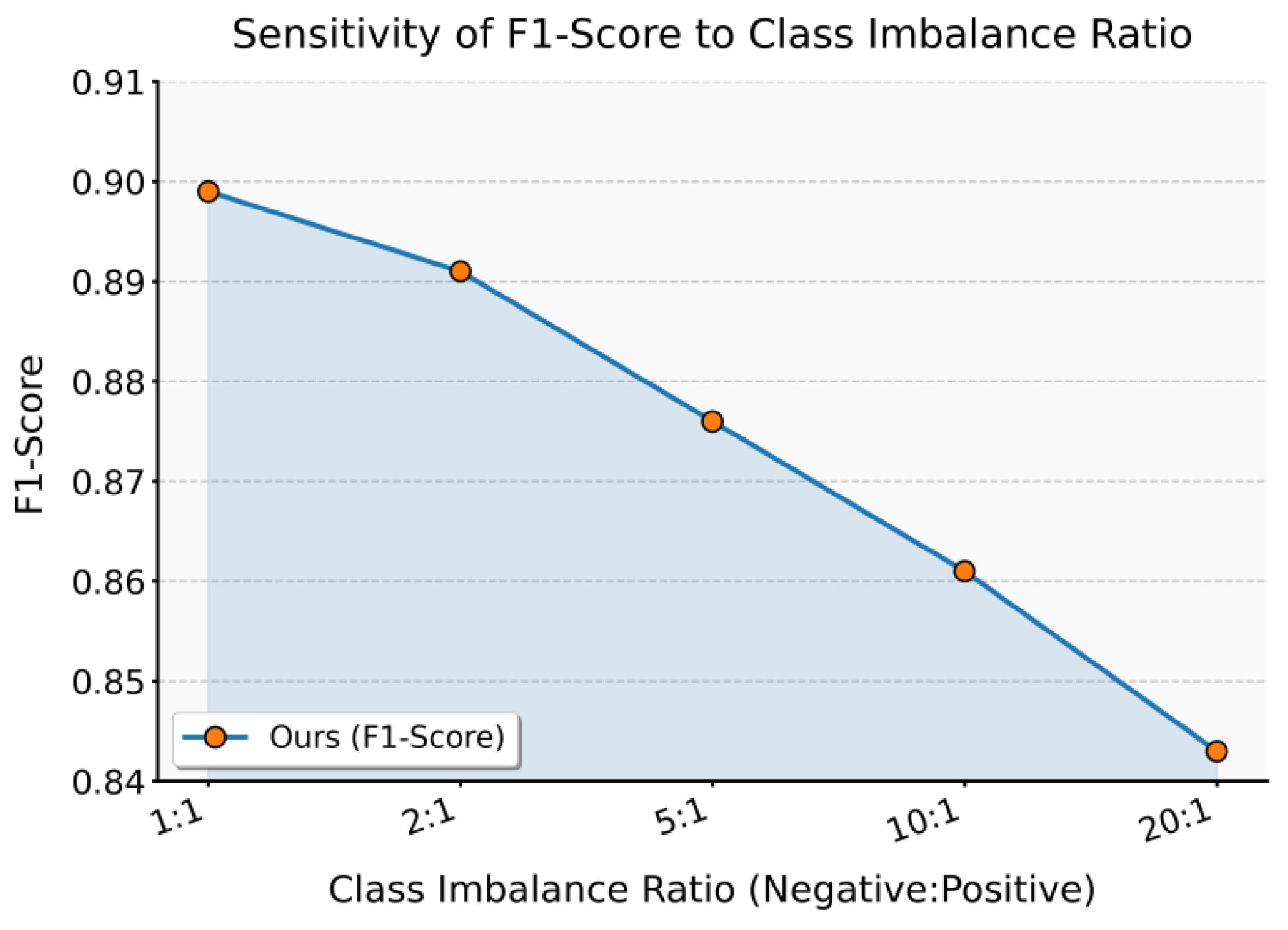

4.2. Experimental Results

5. Conclusions

References

- Y. Zhang and B. Duan, “Accounting data anomaly detection and prediction based on self-supervised learning,” Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics, vol. 11, 1628652.

- K. Reynisson, M. Schreyer and D. Borth, “GraphGuard: Contrastive self-supervised learning for credit-card fraud detection in multi-relational dynamic graphs. arXiv preprint, 2024; arXiv:2407.12440.

- Y. Zou, “Hierarchical large language model agents for multi-scale planning in dynamic environments,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 2, 2024.

- Y. Wang, “Structured compression of large language models with sensitivity-aware pruning mechanisms,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 3, no. 9, 2024.

- Q. Wang, X. Zhang and X. Wang, “Multimodal integration of physiological signals clinical data and medical imaging for ICU outcome prediction,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 4, no. 8, 2025.

- S. Wang, S. Han, Z. Cheng, M. Wang and Y. Li, “Federated fine-tuning of large language models with privacy preservation and cross-domain semantic alignment,” 2025.

- R. Wang, Y. Chen, M. Liu, G. Liu, B. Zhu and W. Zhang, “Efficient large language model fine-tuning with joint structural pruning and parameter sharing,” 2025.

- Z. Xue, “Dynamic structured gating for parameter-efficient alignment of large pretrained models,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 3, 2024.

- W. Zhu, “Fast adaptation pipeline for LLMs through structured gradient approximation,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 3, no. 6, 2024.

- J. Hu, B. Zhang, T. Xu, H. Yang and M. Gao, “Structure-aware temporal modeling for chronic disease progression prediction. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2508.14942.

- D. Gao, “High fidelity text to image generation with contrastive alignment and structural guidance. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2508.10280.

- Y. Zi and X. Deng, “Joint modeling of medical images and clinical text for early diabetes risk detection,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 4, no. 7, 2025.

- X. Zhang, X. Wang and X. Wang, “A reinforcement learning-driven task scheduling algorithm for multi-tenant distributed systems. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2508.08525.

- C. Hu, Z. Cheng, D. Wu, Y. Wang, F. Liu and Z. Qiu, “Structural generalization for microservice routing using graph neural networks. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2510.15210.

- H. Liu, Y. H. Liu, Y. Kang and Y. Liu, “Privacy-preserving and communication-efficient federated learning for cloud-scale distributed intelligence,” 2025.

- S. Pan and D. Wu, “Trustworthy summarization via uncertainty quantification and risk awareness in large language models,” 2025.

- X. Hu, Y. Kang, G. Yao, T. Kang, M. Wang and H. Liu, “Dynamic prompt fusion for multi-task and cross-domain adaptation in LLMs. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2509.18113.

- X. Quan, “Structured path guidance for logical coherence in large language model generation,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 3, no. 3, 2024.

- R. Zhang, “Privacy-oriented text generation in LLMs via selective fine-tuning and semantic attention masks,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 4, no. 8, 2025.

- R. Zhang, L. Lian, Z. Qi and G. Liu, “Semantic and structural analysis of implicit biases in large language models: An interpretable approach. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2508.06155.

- X. Song, Y. Liu, Y. Luan, J. Guo and X. Guo, “Controllable abstraction in summary generation for large language models via prompt engineering. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2510.15436.

- S. Visbeek, E. Acar and F. den Hengst, “Explainable fraud detection with deep symbolic classification,” Proceedings of the World Conference on Explainable Artificial Intelligence, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 350-373, 2024.

- M. Tayebi and S. El Kafhali, “Generative modeling for imbalanced credit card fraud transaction detection,” Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 9, 2025.

- Z. Liu and Z. Zhang, “Modeling audit workflow dynamics with deep Q-learning for intelligent decision-making,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 12, 2024.

- M. Jiang, S. Liu, W. Xu, S. Long, Y. Yi and Y. Lin, “Function-driven knowledge-enhanced neural modeling for intelligent financial risk identification,” 2025.

- Y. Zhou, “Self-supervised transfer learning with shared encoders for cross-domain cloud optimization,” 2025.

- Z. Xu, J. Xia, Y. Yi, M. Chang and Z. Liu, “Discrimination of financial fraud in transaction data via improved Mamba-based sequence modeling,” 2025.

- C. Liu, Q. Wang, L. Song and X. Hu, “Causal-aware time series regression for IoT energy consumption using structured attention and LSTM networks,” 2025.

- W. Xu, M. Jiang, S. Long, Y. Lin, K. Ma and Z. Xu, “Graph neural network and temporal sequence integration for AI-powered financial compliance detection,” 2025.

- L. Dai, “Contrastive learning framework for multimodal knowledge graph construction and data-analytical reasoning,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 3, no. 4, 2024.

- Y. Zi, M. Gong, Z. Xue, Y. Zou, N. Qi and Y. Deng, “Graph neural network and transformer integration for unsupervised system anomaly discovery. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2508.09401.

- H. Wang, “Temporal-semantic graph attention networks for cloud anomaly recognition,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 4, 2024.

- L. Dai, “Integrating causal inference and graph attention for structure-aware data mining,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 4, 2024.

- W. Cui, “Unsupervised contrastive learning for anomaly detection in heterogeneous backend system,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 7, 2024.

- Q. R. Xu, “Capturing structural evolution in financial markets with graph neural time series models,” 2025.

- Y. Qin, “Hierarchical semantic-structural encoding for compliance risk detection with LLMs,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 6, 2024.

- X. Su, “Deep forecasting of stock prices via granularity-aware attention networks,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 3, no. 7, 2024.

- Z. Liu and Z. Zhang, “Graph-based discovery of implicit corporate relationships using heterogeneous network learning,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 3, no. 7, 2024.

- Q. Sha, T. Tang, X. Du, J. Liu, Y. Wang and Y. Sheng, “Detecting credit card fraud via heterogeneous graph neural networks with graph attention. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2504.08183.

- X. Su, “Forecasting asset returns with structured text factors and dynamic time windows,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 6, 2024.

- Y. Qin, “Deep contextual risk classification in financial policy documents using transformer architecture,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 3, no. 8, 2024.

- Q. Xu, “Unsupervised temporal encoding for stock price prediction through dual-phase learning,” 2025.

- X. Zhang, M. Xu and X. Zhou, “Realnet: A feature selection network with realistic synthetic anomaly for anomaly detection,” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 16699-16708, 2024.

- H. He, Y. Bai, J. Zhang, et al., “Mambaad: Exploring state space models for multi-class unsupervised anomaly detection,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 37, pp. 71162-71187, 2024.

- C. Wang, W. Zhu, B. B. Gao, et al., “Real-iad: A real-world multi-view dataset for benchmarking versatile industrial anomaly detection,” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 22883-22892, 2024.

- Y. Wang, “Gradient-guided adversarial sample construction for robustness evaluation in language model inference,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 7, 2024.

- Y. Cao, J. Zhang, L. Frittoli, et al., “Adaclip: Adapting clip with hybrid learnable prompts for zero-shot anomaly detection,” Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 55-72, 2024.

- L. Lian, “Semantic and factual alignment for trustworthy large language model outputs,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 3, no. 9, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).