Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Analysis

3.1.1. Correlation Analysis

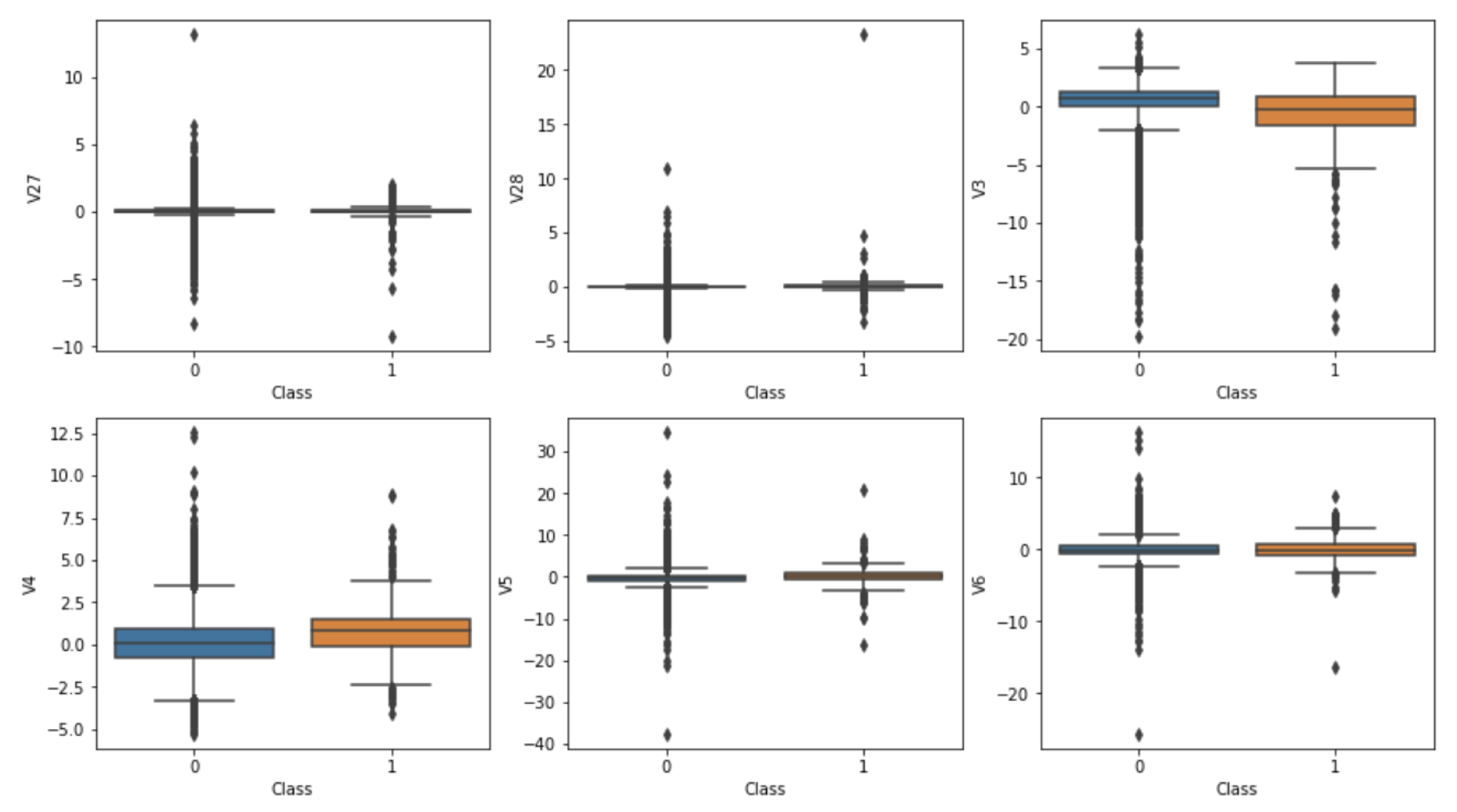

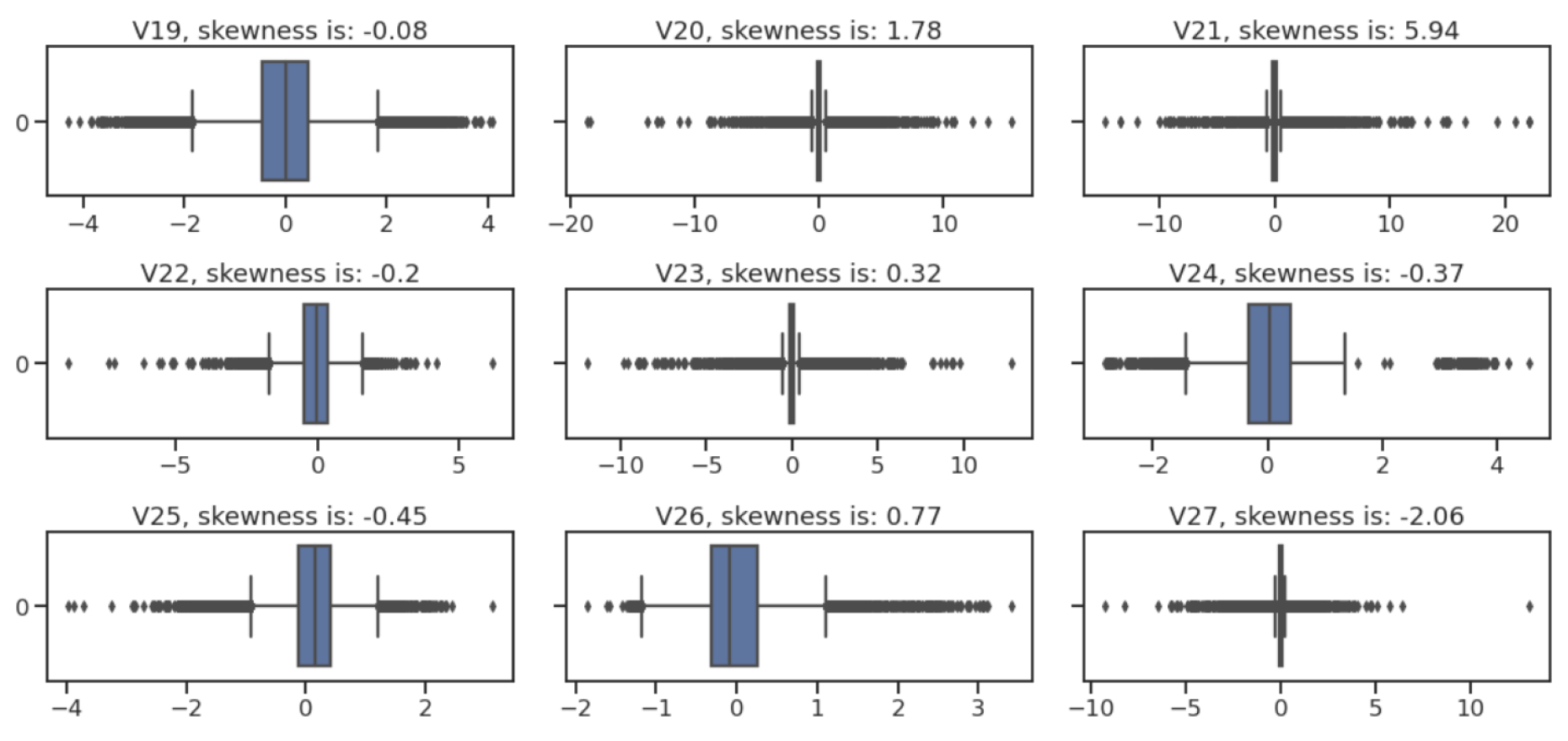

3.1.2. Outlier Detection

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Feature Extraction

- (1)

- Normalization: Data normalization was conducted to standardize the range of independent variables. Each feature was scaled to a zero mean and unit variance using the formula:where represents the mean, and represents the standard deviation of the feature. This step ensures that the model’s performance is not skewed by features with larger magnitudes.

- (2)

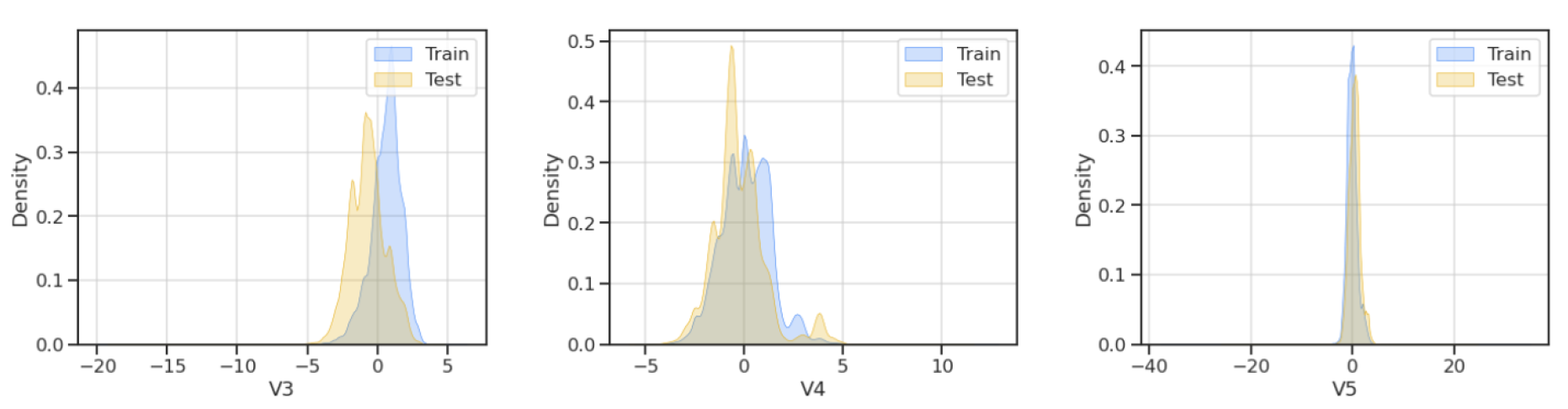

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): To protect the privacy of the users and reduce the feature space, PCA was applied. PCA transforms the dataset into a set of orthogonal components that capture the most variance:where Z is the matrix of principal components, X is the original data matrix, and W is the matrix of eigenvectors corresponding to the largest eigenvalues. We selected 28 principal components (V1-V28) that accounted for the majority of the data’s variance, ensuring efficient dimensionality reduction while retaining critical information for fraud detection.

- (3)

- Feature Selection: In addition to PCA, feature selection was carried out to identify and retain the most relevant features for the model. Features that showed a high correlation with the target variable, or exhibited significant differences between fraudulent and non-fraudulent transactions, were prioritized. This included features like transaction amount and balance changes.

3.3. Handling Class Imbalance

- (1)

- Random Undersampling: This technique reduces the number of majority class instances to match the minority class, thus balancing the dataset:where includes all instances of the minority class (fraudulent transactions), and represents a randomly selected subset of the majority class (non-fraudulent transactions). This helps prevent the model from becoming biased towards the majority class. The result is depicted in Figure 4.

- (2)

- SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique): SMOTE generates synthetic samples for the minority class by interpolating between existing minority class instances and their nearest neighbors:where is a synthetic sample, is a minority class sample, is one of its nearest neighbors, and is a random value between 0 and 1. This technique increases the diversity of the minority class and helps the model learn to detect fraudulent transactions more effectively.

3.4. Model Selection and Ensemble Learning

- (1)

- Logistic Regression (LR): Logistic regression is a linear model used for binary classification, predicting the probability of a transaction being fraudulent:where . The coefficients are estimated using maximum likelihood estimation, which minimizes the cost function:where is the hypothesis function, are the true labels, and m is the number of observations.

- (2)

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN): KNN is a non-parametric method that classifies transactions based on the majority vote of their k-nearest neighbors in the feature space. The distance metric, typically Euclidean distance, determines which transactions are nearest to a given point.

- (3)

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): SVM constructs a hyperplane that maximizes the margin between the classes:where w is the normal vector to the hyperplane, b is the bias, and are the class labels. SVM is effective in high-dimensional spaces and robust to overfitting, especially when the feature space is transformed using kernel functions.

- (4)

- Decision Tree (DT): DT is a tree-based model that recursively splits the data based on feature values to create a tree structure, where each node represents a decision rule and each leaf represents a class label. The splitting criterion, such as Gini impurity or entropy, determines the quality of the splits.

- (5)

-

Ensemble Methods: Ensemble learning combines the outputs of multiple models to improve overall performance. We used two primary ensemble approaches:

- (a)

- Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating): This method involves training multiple models on different bootstrap samples of the data and aggregating their predictions to reduce variance and improve stability.

- (b)

- Boosting: Boosting trains models sequentially, with each model focusing on the errors of its predecessor, thus reducing bias and variance.

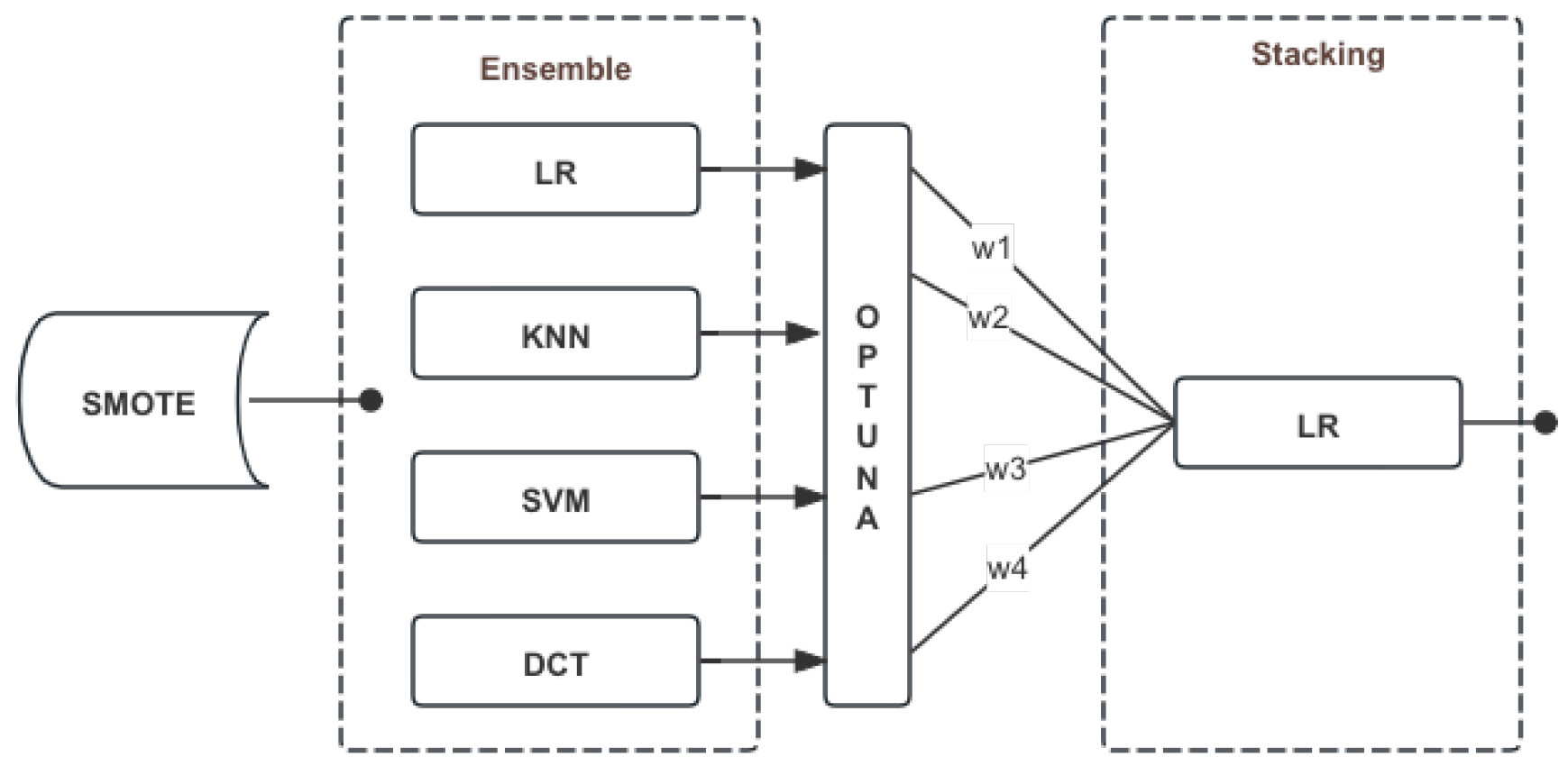

3.5. Ensemble + Logistic Regression (LR)

- (1)

-

Ensemble Method: The Ensemble + LR model aggregates the predictions of base classifiers such as KNN, SVM, and DT, using a logistic regression model as the final classifier. The logistic regression model assigns weights to the predictions from each base classifier to optimize the final decision boundary. This approach ensures that the ensemble takes advantage of the diversity and complementary strengths of the individual classifiers:Here, represents the final prediction, is the sigmoid function, are the coefficients of the logistic regression model, and are the individual predictions from the base classifiers. The logistic regression meta-model effectively combines these predictions to yield a more accurate and robust output.

- (2)

- Hyperparameter Optimization: The weights of the logistic regression model and other hyperparameters were optimized using GridSearchCV. This method performs an exhaustive search over a specified parameter grid to identify the optimal set of parameters that maximize the model’s performance. The grid search process involves fitting the model on the training data with different combinations of parameters and evaluating its performance using cross-validation. This ensures that the model parameters are fine-tuned for the best possible predictive performance.

3.6. Comparison of Random Undersampling and SMOTE

- (1)

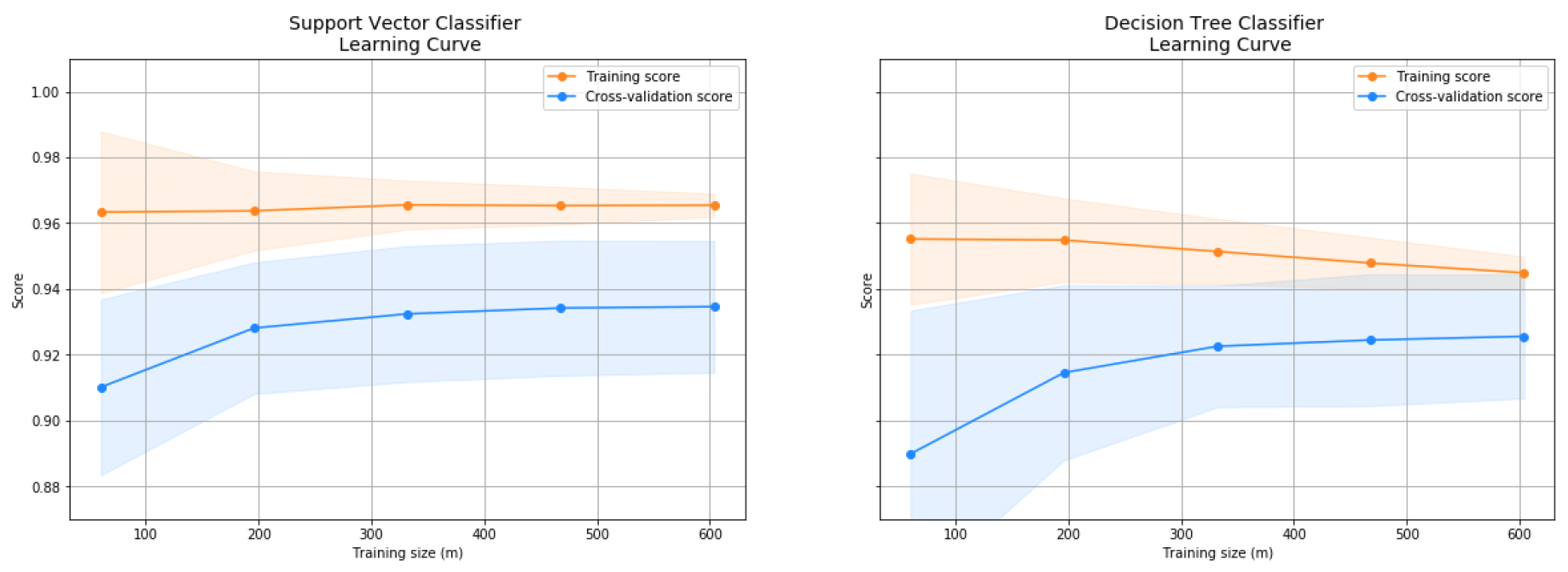

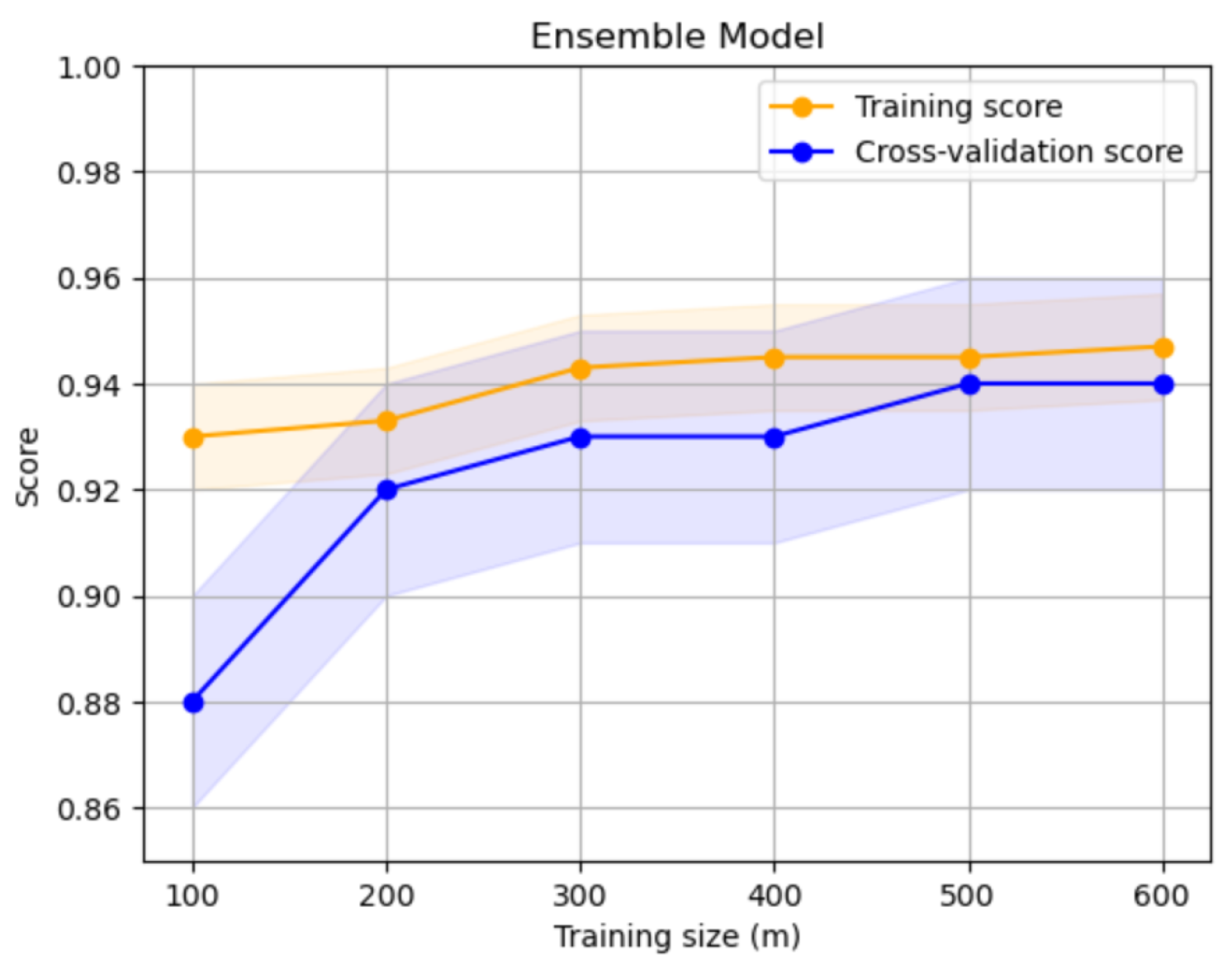

- Learning Curves: The learning curves shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate how the models’ performance metrics evolve during training with each sampling method. These curves demonstrate the convergence speed and stability of the models, with SMOTE generally resulting in smoother and more consistent improvements.

- (2)

-

Performance Comparison: The table below (Table 1) compares the performance of the Ensemble model using random undersampling and SMOTE. It highlights the precision, recall, and F1-score for each sampling method.The results indicate that SMOTE, despite its computational expense, offered a slight improvement in model performance. Logistic Regression showed the best balance between training and cross-validation scores, indicating optimal model performance with a well-generalized model. Consequently, the weight of the Logistic Regression model was increased in the ensemble to enhance overall performance.

3.7. Proposed Stacking Model

- (1)

- Stacking Method: The stacking model takes the outputs from the ensemble model and feeds them into a new model to achieve a more refined integration. We compared the effectiveness of a logistic regression model and a LightGBM model for this task. It was found that using a simpler linear model like logistic regression led to faster convergence to a satisfactory performance. Figure 7 illustrates the overall training architecture of the stacking model.

- (2)

- Hyperparameter Optimization with Optuna: The optimal weights and parameters for the stacking model were determined using Optuna, a hyperparameter optimization tool. By setting a specific number of training steps and using Optuna for optimization, we identified the best blending coefficients that significantly improved the model’s score compared to individual models. This optimization ensured rapid convergence to an optimal solution, improving the overall performance of the model.

- (3)

- Performance Improvement: The proposed stacking model showed noticeable improvements in performance metrics compared to the ensemble method alone. The use of a logistic regression model in the stacking process facilitated quick convergence and provided a well-balanced integration of the ensemble model’s outputs. This approach highlights the benefits of combining advanced ensemble techniques with efficient hyperparameter tuning to enhance the accuracy and reliability of fraud detection systems. Figure 8 illustrates the learning curve of the training process.

4. Experiments Results

4.1. Performance Metrics

5. Conclusions

References

- Bolton, R.J.; Hand, D.J. Statistical fraud detection: A review. Statistical science 2002, 17, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, C.; Lee, V.; Smith, K.; Gayler, R. A comprehensive survey of data mining-based fraud detection research. arXiv preprint arXiv:1009.6119 2010.

- He, C.; Liu, M.; Hsiang, S.M.; Pierce, N. Synthesizing Ontology and Graph Neural Network to Unveil the Implicit Rules for US Bridge Preservation Decisions. Journal of Management in Engineering 2024, 40, 04024007. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, L.; Wei, C.; Wang, H. Financial Text Sentiment Classification Based on Baichuan2 Instruction Finetuning Model. 2023 5th International Conference on Frontiers Technology of Information and Computer (ICFTIC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 403–406.

- West, J.; Bhattacharya, M. Intelligent financial fraud detection: a comprehensive review. Computers & security 2016, 57, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jans, M.J.; Alles, M.; Vasarhelyi, M.A. Process mining of event logs in auditing: Opportunities and challenges. Available at SSRN 1578912 2010.

- Dal Pozzolo, A.; Caelen, O.; Le Borgne, Y.A.; Waterschoot, S.; Bontempi, G. Learned lessons in credit card fraud detection from a practitioner perspective. Expert systems with applications 2014, 41, 4915–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, S.; Binder, A.; Montavon, G.; Klauschen, F.; Müller, K.R.; Samek, W. On pixel-wise explanations for non-linear classifier decisions by layer-wise relevance propagation. PloS one 2015, 10, e0130140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hsiang, S.M.; Chen, G.; Chen, J. Exploit social distancing in construction scheduling: Visualize and optimize space–time–workforce tradeoff. Journal of Management in Engineering 2022, 38, 04022027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Jha, S.; Tharakunnel, K.; Westland, J.C. Data mining for credit card fraud: A comparative study. Decision support systems 2011, 50, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgovsky, J.; Granitzer, M.; Ziegler, K.; Calabretto, S.; Portier, P.E.; He-Guelton, L.; Caelen, O. Sequence classification for credit-card fraud detection. Expert systems with applications 2018, 100, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Guillen, M.; Westland, J.C. Employing transaction aggregation strategy to detect credit card fraud. Expert systems with applications 2012, 39, 12650–12657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, X.; He, C. Study on dynamic influence of passenger flow on intelligent bus travel service model. Transport 2021, 36, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, E.; Ozcelik, M.H. Detecting credit card fraud by genetic algorithm and scatter search. Expert Systems with Applications 2011, 38, 13057–13063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vlasselaer, V.; Bravo, C.; Caelen, O.; Eliassi-Rad, T.; Akoglu, L.; Snoeck, M.; Baesens, B. APATE: A novel approach for automated credit card transaction fraud detection using network-based extensions. Decision support systems 2015, 75, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T.; Provost, F. Adaptive fraud detection. Data mining and knowledge discovery 1997, 1, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Shao, C. Multi-task learning for data-efficient spatiotemporal modeling of tool surface progression in ultrasonic metal welding. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2021, 58, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, B.; Yang, L.; Qu, P. The Application of Natural Language Processing Technology in the Era of Big Data. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Applied Science 2024, 2, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Raiaan, M.A.K.; Mukta, M.S.H.; Fatema, K.; Fahad, N.M.; Sakib, S.; Mim, M.M.J.; Ahmad, J.; Ali, M.E.; Azam, S. A review on large Language Models: Architectures, applications, taxonomies, open issues and challenges. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ortiz, J. Rapid Review of Generative AI in Smart Medical Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.06627 2024. arXiv:2406.06627 2024.

| Technique | Score |

|---|---|

| Random Undersampling | 0.957672 |

| Oversampling (SMOTE) | 0.988167 |

| Model | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | AUC | Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNN | 0.913 | 0.924 | 0.922 | 0.935 | 0.891 |

| SVM | 0.924 | 0.923 | 0.933 | 0.968 | 0.901 |

| Decision Tree | 0.923 | 0.931 | 0.892 | 0.920 | 0.894 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.921 | 0.931 | 0.951 | 0.968 | 0.902 |

| Ensemble | 0.941 | 0.941 | 0.931 | 0.969 | 0.914 |

| Ensemble + LightGBM | 0.931 | 0.923 | 0.942 | 0.968 | 0.925 |

| Ensemble + LR | 0.947 | 0.951 | 0.951 | 0.971 | 0.933 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).