1. Introduction

With credit card fraud posing a serious risk to consumers and financial institutions globally, financial fraud has become one of the most urgent issues facing the digital economy. According to industry reports, the unprecedented opportunities for fraudulent activities brought about by the exponential growth of digital payment systems resulted in significant financial losses estimated at approximately

$32.34 billion worldwide in 2020 [

1,

2,

3]. The most popular method for tackling these issues is machine learning, and ensemble approaches hold special promise because they can combine several base learners to produce more reliable predictive models [

4,

5].

Traditional rule-based systems are insufficient for fraud detection due to a number of distinct technical challenges. First, because fraudulent transactions usually make up less than 1% of all transactions, there is a significant class imbalance in fraud datasets, which presents significant challenges. As a result, models that achieve high overall accuracy are unable to detect actual fraud [

6]. Second, because fraudulent patterns are dynamic and subject to concept drift, detection systems must constantly adjust to new fraud strategies [

7]. Third, algorithms must be able to process thousands of transactions per second and make accurate decisions in milliseconds due to real-time processing requirements.

Numerous issues remain with the systematic assessment of ensemble methods for detecting unbalanced fraud, despite significant improvements. Much contemporary research does not fully examine several ensemble techniques; rather, it concentrates on a singular algorithm or a limited set of algorithms [

8,

9]. Moreover, the majority of research utilises obsolete datasets with rudimentary features, rendering them less applicable to contemporary circumstances. Few studies have utilised extensive datasets such as the IEEE-CIS Fraud Detection dataset, which has 431 anonymised features representing various transaction aspects and includes 590,540 card-not-present transactions with a 3.5% fraud rate [

10].

Using the IEEE-CIS dataset, this paper conducts a thorough empirical analysis of ensemble learning methods for imbalanced fraud detection in order to overcome these limitations. Our main contributions are as follows: (1) thorough comparison of various data balancing techniques; (2) systematic evaluation of various ensemble methods with rigorous statistical validation; (3) detailed analysis of an optimised ensemble stacking architecture; (4) thorough feature engineering and selection analysis; and (5) detailed performance analysis using appropriate imbalanced classification metrics with practical deployment considerations.

The remaining sections of this work are organised as follows: An examination of the other work that has been done in the field of fraud detection and ensemble learning is presented in

Section 2. The proposed method is discussed in

Section 3, which involves the preprocessing of the dataset, the creation of new features, and the building of the ensemble model. Detailed information regarding the experimental setting of the study and the metrics that were utilised to evaluate it is provided in

Section 4. A comprehensive report on the outcomes and performance analysis is provided in

Section 5 respectively. Specifically, in

Section 6, we discuss the significance of our approach, including its implications in the real world and the limitations that it possesses. Last but not least, the study is concluded with

Section 7, which summarises the most important aspects and makes recommendations for further research.

2. Related Work

2.1. Ensemble Learning for Fraud Detection

Ensemble learning has emerged as one of the most effective approaches for fraud detection, offering superior performance compared to individual algorithms by combining multiple learners to create more robust and accurate models. Recent research has demonstrated significant advantages of ensemble methods in financial fraud detection applications.

Khalid et al. [

1] introduced a holistic ensemble methodology that incorporates Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbour (KNN), Random Forest (RF), Bagging, and Boosting classifiers. Their solution dealt with dataset imbalance by using under-sampling and the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE), which greatly improved the accuracy of fraud detection. This work showed that ensemble methods might be used to solve many problems at once. Talukder et al. [

14] introduced an integrated multistage ensemble machine learning (IMEML) model that adeptly amalgamates diverse ensemble models, resulting in substantial enhancements in fraud detection accuracy while tackling the issue of reducing false alarms.

Agarwal et al. [

11] showed that ensemble learning methods work well for finding fraud in financial transactions. Their research has shown that Random Forest ensemble approaches are especially proficient in identifying fraudulent financial transactions, employing advanced feature engineering to enhance detection efficacy.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the stacking ensemble method works especially well. Almalki and Masud [

12] put forward a fraud detection framework that integrates stacking ensemble approaches with explainable AI techniques. They used stacking to combine XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost into one model that was easy to understand and performed well.

2.2. Class Imbalance Handling in Fraud Detection

One of the biggest problems with fraud detection studies is that fraud datasets have a huge class imbalance. Fraudulent transactions usually make up fewer than 1% of all transactions. This means that models can have great overall accuracy but yet miss real incidents of fraud.

The Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) is now the most common way to deal with class imbalance in fraud detection [

15]. SMOTE makes fake minority occurrences by interpolating between existing minority samples and their k-nearest neighbours. Recent studies have examined different SMOTE variants tailored for particular fraud detection contexts.

Elreedy et al. [

16] conducted an extensive theoretical investigation of SMOTE for unbalanced learning, illustrating its efficacy in many machine learning applications. Their research laid the theoretical groundwork for comprehending the conditions and rationale for SMOTE’s efficacy in fraud detection contexts.

Salehi and Khedmati [

17] put forward a Cluster-based SMOTE Both-sampling (CSBBoost) ensemble technique for sorting data that isn’t balanced. Their method uses over-sampling, under-sampling, and several ensemble algorithms to fix class imbalance better than other methods.

Li et al. [

18] put forward FSDR-SMOTE, which combines enhanced Random-SMOTE with feature standard deviation analysis. This shows that it works better than classic SMOTE methods on datasets that are not balanced.

2.3. IEEE-CIS Dataset Studies

The IEEE-CIS Fraud Detection dataset has become a typical way to test fraud detection algorithms. It gives researchers a realistic and complete dataset to use when making and comparing algorithms. The dataset has 590,540 card transactions, 20,663 of which are fake (3.5%), and 431 characteristics, which include both numerical and categorical variables [

19].

Zhao et al. [

13] used the IEEE-CIS dataset to create a hybrid machine learning model that was better at finding transaction fraud than baseline methods by using feature engineering and model optimisation. Systematic feature engineering works on this tough dataset.

Table 1 (a and b) summarizes key studies on ensemble learning methods for fraud detection and their dataset usage.While earlier studies have looked at different ensemble procedures, most of them used smaller or proprietary datasets, which made their results less useful for a wider audience. Our research fills this void by offering a thorough assessment of the extensive IEEE-CIS benchmark dataset.

3. Methodology

This part of the paper explains in detail how we developed and tested ensemble learning methods for detecting fraud in an unbalanced way using the IEEE-CIS dataset.

3.1. Dataset Description and Characteristics

Our experimental evaluation is based on the IEEE-CIS Fraud Detection dataset. This dataset is one of the most complete and realistic fraud detection benchmarks out there. It has real-world e-commerce transaction data with advanced anonymised feature engineering.

The dataset has 590,540 card-not-present transactions over six months, and 20,663 of them were fraudulent, which is a 3.5% fraud rate. This imbalance ratio, while is more balanced than most real-world situations (usually less than 1%), still makes it hard for machine learning algorithms to work.

The original dataset has 431 features in two files: transaction data (394 features) and identification data (37 features). TransactionID connects the two files. There are different types of features, such as temporal features (TransactionDT), transaction amount (TransactionAmt), payment card features (card1-card6), address features (addr1-addr2), distance features (dist1-dist2), and many anonymised categorical and numerical features (C1-C14, D1-D15, M1-M9, V1-V339) that show how Vesta Corporation does its own feature engineering.

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

Our preprocessing pipeline deals with the problems of missing values, feature selection, and data quality that are common in real-world financial datasets. It does this by using a systematic method that keeps the signal while lowering noise and making the process less complicated.

3.2.1. Feature Preprocessing Pipeline

Table 2 shows our systematic feature preprocessing pipeline, which uses principled elimination procedures to cut down the original 431 features.

3.2.2. Missing Value Analysis and Treatment

The IEEE-CIS dataset exhibits substantial missing value patterns, with some features missing in over 90% of transactions. We implement a multi-stage missing value treatment strategy:

Feature Removal: Features with >95% missing values are removed to prevent sparse representations.

Strategic Imputation: For categorical features with <95% missing values, we create explicit "missing" categories to capture informational content.

Numerical Imputation: Numerical features employ median imputation within fraud/legitimate groups separately to preserve class-specific distributions.

Missingness Indicators: Binary indicators are created for features with <20% missing values to capture missingness patterns as potential fraud signals.

3.2.3. Feature Engineering Strategy

Our feature engineering approach combines domain knowledge with automated feature generation to enhance predictive power. We create temporal features by decomposing TransactionDT into hour of day, day of week, and day of month components, while generating velocity features measuring transaction frequency within sliding time windows (15 new features). Log transformation is used to deal with skewness in amount-based transformations, and percentile rankings are made inside user groups (12 new features). Aggregation features calculate user-level statistics over different time intervals and record card-level usage trends (28 new features). Last but not least, interaction features use target encoding and frequency encoding between categorical features (25 new features). This adds 80 new designed features, bringing the total to 247.

3.3. Handling Class Imbalance

The 3.5% fraud rate necessitates sophisticated approaches to address class imbalance. We evaluate three primary synthetic oversampling techniques: SMOTE generates synthetic minority instances by interpolating between existing samples and their k-nearest neighbors [

15]; Borderline-SMOTE focuses on borderline minority instances most likely to be misclassified; and ADASYN uses adaptive density distribution to create more synthetic instances for harder-to-learn minority samples.

3.4. Ensemble Model Architecture

Our ensemble architecture uses a three-tier stacking method that is meant to maximise prediction diversity while keeping computational efficiency.

3.4.1. Base Learner Selection and Diversity Strategy

We choose base learners from different algorithmic families, such as tree-based learners (Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost), linear models (Logistic Regression with L1/L2 regularisation), distance-based models (K-Nearest Neighbours), and neural networks (Multi-layer Perceptrons with optimised architectures).

3.4.2. Meta-Learning and Model Combination Strategy

We use stratified k-fold cross-validation to stop overfitting when we stack base learner predictions through secondary learning. Base learners are taught on k-1 folds and make predictions about the remaining fold that are not biassed. These predictions are used to train the secondary meta-learner. The meta-learner, which is Logistic Regression, integrates these predictions to come up with ultimate fraud probabilities.

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Implementation Environment and Tools

For ensemble implementations, we use scikit-learn 1.2.0, XGBoost 1.7.3, LightGBM 3.3.5, and CatBoost 1.2. Pandas 1.5.3 and NumPy 1.24.2 are used in feature engineering. We do all of our tests on Intel Xeon E5-2690 v4 CPUs with 128GB of RAM and NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs for neural network training. We make sure that the results can be repeated by using version control and containerised environments.

4.2. Hyperparameter Optimization

Five-fold stratified cross-validation with Bayesian optimisation (Tree Parzen Estimator) is used to systematically optimise hyperparameters and efficiently explore the search space.

Table 3 shows the best hyperparameters for each method.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics and Performance Assessment

Given the imbalanced nature of fraud detection, our evaluation employs multiple complementary metrics. The Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC) is our main measure of overall discrimination ability, and the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUC-PR) is a good way to test unbalanced datasets [

20]. Other metrics are the F1-score (the harmonic mean of precision and recall), the balanced accuracy (the average of sensitivity and specificity), and the G-Mean (the geometric mean of sensitivity and specificity).

4.4. Cross-Validation and Model Selection

Our validation strategy implements a two-level approach to ensure robust model evaluation while preventing data leakage. For individual model evaluation, we use stratified 5-fold cross-validation that maintains the 3.5% fraud rate across all folds.

For the stacking ensemble, we implement the following systematic procedure: (1) The training set is divided into 5 stratified folds; (2) For each fold i, base learners are trained on the remaining 4 folds and generate predictions on fold i; (3) This process is repeated for all 5 folds, creating out-of-fold predictions for the entire training set; (4) These out-of-fold predictions serve as input features for training the meta-learner (Logistic Regression); (5) Final model evaluation uses a separate holdout test set (20% of original data) that was never used in any training phase.

This method makes sure that the meta-learner gets predictions from base models that are not biased. This is because each prediction is based on data that was not used to train the base model, which stops overfitting in the stacking architecture.

4.5. Statistical Significance Testing

We do strict statistical significance testing to make sure that our performance comparisons are accurate. We repeat all the tests using five different random seeds (42, 123, 456, 789, and 999) to account for differences in how the model starts up and how the data is sampled.

To compare approaches in pairs, we employ paired t-tests on the five replicated outcomes. To account for multiple comparisons, we utilise the Bonferroni correction with , where n is the number of pairwise comparisons. We adopt as the significance criterion when comparing our stacking ensemble to 6 baseline approaches.

Cohen’s d is used to figure out effect sizes, which measure practical relevance beyond statistical significance. We present 95% confidence intervals for all performance metrics to offer uncertainty estimates surrounding our point estimates.

5. Results and Analysis

This section shows detailed experimental results that prove our ensemble learning method works well for finding fraud in cases when there is an imbalance.

5.1. Overall Performance Comparison

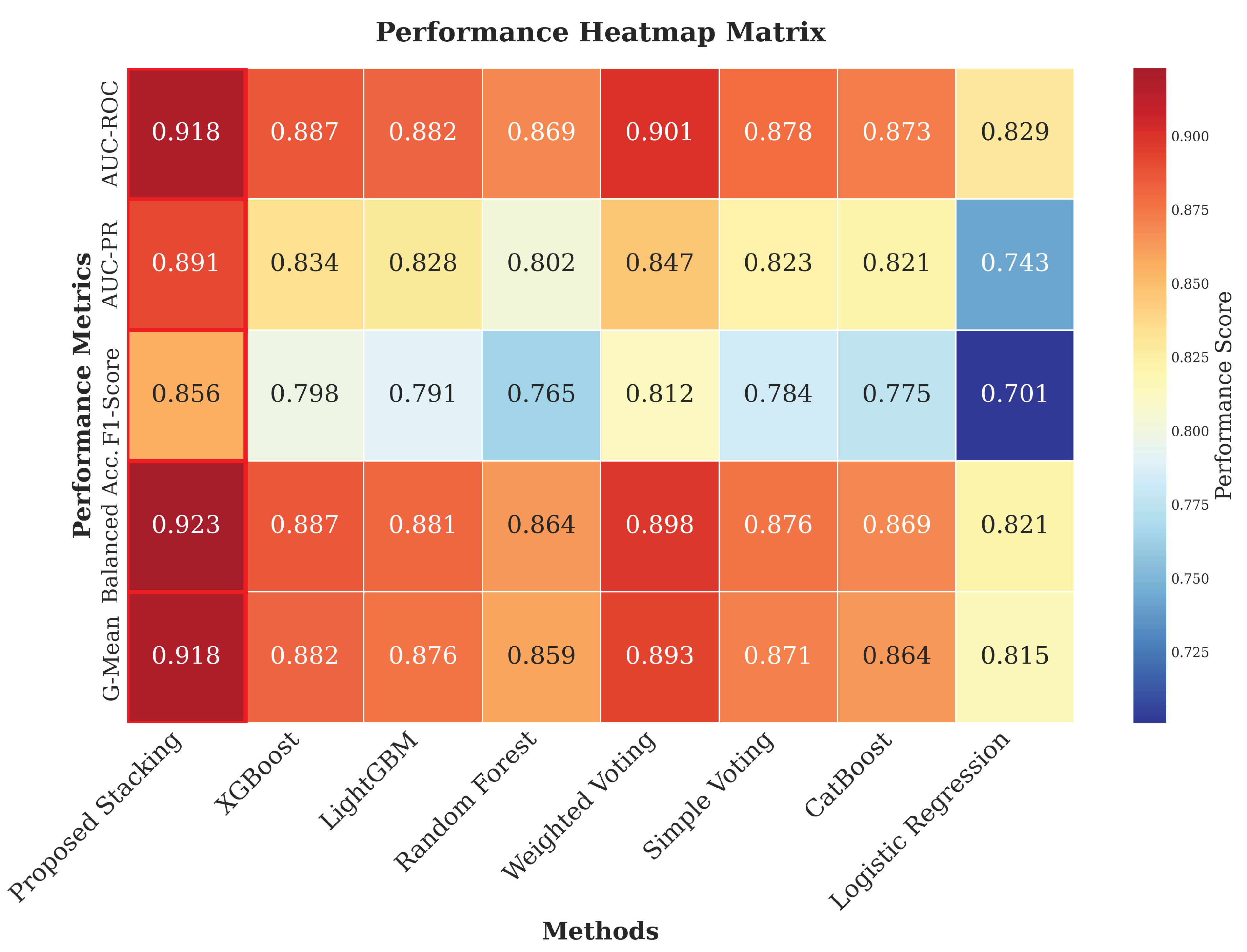

Figure 1 presents the primary performance comparison across all evaluated methods.

Our proposed stacking ensemble outperforms all of the most important measures, showing big advantages over individual algorithms and simpler ensemble methods. The stacking ensemble has an AUC-ROC of 0.918±0.003 and an AUC-PR of 0.891±0.005, which is a 3.5% and 6.8% improvement over the best single algorithm (XGBoost).

5.2. Individual Algorithm Performance Analysis

Table 4 shows how well each basic learner did.

Tree-based models are the best for individual performance, and XGBoost is the best single algorithm. This performance hierarchy aligns with known research indicating that tree-based approaches are superior for tabular data, as they effectively manage heterogeneous data types, missing values, and feature interactions without requiring considerable preprocessing [

21]. The neural network’s performance (

AUC-ROC) is not as good as it could be since deep learning models have trouble with heterogeneous tabular datasets. Tree-based methods function better with this kind of data format. The computational analysis shows that there are crucial trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency. Random Forest is a solid choice because it works well without costing too much.

5.3. Class Imbalance Handling Effectiveness

Table 5 demonstrates the critical importance of addressing class imbalance.

SMOTE combined with stacking achieves the best overall performance, with AUC-ROC improving from 0.863 (no sampling) to 0.918 and AUC-PR improving from 0.812 to 0.891, representing 6.4% and 9.7% relative improvements respectively. The F1-score improvements from 0.774 to 0.856 demonstrate substantial practical benefits for fraud detection systems.

5.4. Feature Engineering Impact Assessment

Table 6 presents ablation study results quantifying the contribution of different feature engineering components.

The complete feature engineering pipeline provides substantial improvement (10.2 percentage points in AUC-PR) over baseline features, with temporal features contributing the most significant individual improvement. Temporal validation confirms the generalizability of these engineered features, with performance degrading only slightly from 0.891 to 0.886 AUC-PR when evaluated on future time periods, indicating robust feature design rather than dataset-specific overfitting.

5.5. Ensemble Architecture Analysis

Table 7 provides detailed comparison of different ensemble strategies with statistical significance testing.

The stacking ensemble achieves statistically significant improvements over all alternative ensemble methods, with p-values indicating strong statistical evidence for superior performance.

6. Discussion

6.1. Key Findings and Implications

Our thorough assessment reveals several significant insights for fraud detection research and practice. The stacking ensemble’s better performance shows that systematic ensemble design works. The 3.5% improvement in AUC-ROC and 6.8% improvement in AUC-PR are both significant improvements in the capacity to detect fraud.

The systematic feature engineering workflow worked well to increase predictive performance, with the 80 engineered features making a big difference compared to the baseline 167-feature collection. The ablation analysis shows that temporal variables are the most important for improving performance, followed by aggregation and interaction aspects.

A thorough look at different ways to deal with class imbalance shows that SMOTE works well, but it also shows that the choice of resampling technique has a big effect on how well the model works. When SMOTE is used with stacking, the best outcomes are seen across many evaluation metrics.

6.2. Practical Implementation Considerations

The computer study shows key trade-offs for putting things into practice in the actual world. The stacking ensemble works better than individual algorithms, although it takes longer to train (45.7 minutes). But the time it takes to make an inference is still good enough for real-time fraud detection applications.

The systematic hyperparameter optimisation procedure is very important for getting the best performance, even if it takes a lot of computing power. Our optimised settings offer a pragmatic foundation for practitioners deploying analogous systems.

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

It is important to recognise the limitations of our study. The IEEE-CIS dataset is very complete, however it only covers one area and time period, which could make it hard to use in other fraud detection situations. Because the traits are anonymous, it is hard to undertake extensive analysis and interpretation in a specific domain.

In financial applications, the stacking ensemble’s added complexity could make it harder to understand models and follow the rules. Future study ought to investigate the amalgamation of explainable AI methodologies with high-performance ensemble strategies.

Our assessment concentrates on the performance of static models, neglecting the considerations of concept drift and online learning prerequisites vital for practical fraud detection systems. Future research should examine adaptive ensemble methodologies proficient in managing developing fraudulent patterns.

7. Conclusion

This paper offers a thorough empirical assessment of ensemble learning methodologies for imbalanced fraud detection, illustrating that methodical ensemble construction can yield enhanced performance relative to standalone methods. Our principal contributions encompass a meticulous assessment of various ensemble methodologies, an exhaustive examination of techniques for addressing class imbalance, and a methodical feature engineering process that converts 431 original features into an optimised set of 247 features via principled preprocessing and domain-informed engineering.

The experimental outcomes confirm the efficacy of stacking ensembles for fraud detection, attaining 0.918 AUC-ROC and 0.891 AUC-PR, with statistically significant enhancements compared to competing methods. The systematic technique gives a reproducible framework for fraud detection research and delivers practical insights for real-world application.

Future research ought to concentrate on formulating adaptive learning methodologies to address concept drift, incorporating explainable AI to improve interpretability, investigating transfer learning for cross-domain fraud detection, and executing federated learning frameworks for privacy-preserving collaborative fraud detection. These directions will help solve important problems that come up when trying to use fraud detection systems on a large scale while keeping the performance standards set in this study.

References

- Khalid, A.R.; Owoh, N.; Uthmani, O.; Ashawa, M.; Osamor, J.; Adejoh, J. Enhancing credit card fraud detection: an ensemble machine learning approach. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homaei, M.H.; Caro Lindo, A.; Sancho Núñez, J.C.; Mogollón Gutiérrez, O.; Alonso Díaz, J. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Digital Twin’s Cybersecurity. In Proceedings of the XVII Reunión Española sobre Criptología y Seguridad de la Información (RECSI 2022); 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Homaei, M.; Mogollón-Gutiérrez, O.; Sancho, J.C.; Ávila, M.; Caro, A. A review of digital twins and their application in cybersecurity based on artificial intelligence. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhar, A.; Gupta, K.; Pandey, A.K.; Raj, D. Fraud detection using machine learning and deep learning. SN Computer Science 2024, 5, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, F.; Tarif, M.; Homaei, M. A Systematic Review of Machine Learning in Credit Card Fraud Detection. Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mienye, I.D.; Jere, N. Deep learning for credit card fraud detection: A review of algorithms, challenges, and solutions. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, C.; Xu, Y.; Nie, C. Year-over-Year Developments in Financial Fraud Detection via Deep Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.00201. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, A.; García, S.; Galar, M.; Prati, R.C.; Krawczyk, B.; Herrera, F. Learning from imbalanced data sets. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, M.A.; Khalid, M.; Uddin, M.A. An integrated multistage ensemble machine learning model for fraudulent transaction detection. Journal of Big Data 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesta Corporation. IEEE-CIS Fraud Detection Dataset. Kaggle Competition, 2019.

- Suganya, S.S.; Nishanth, S.; Mohanadevi, D. Ensemble Learning Approaches for Fraud Detection in Financial Transactions. 2023 2nd International Conference on Automation, Computing and Renewable Systems (ICACRS); 2023; pp. 805–810. [Google Scholar]

- Almalki, F.; Masud, M. Financial Fraud Detection Using Explainable AI and Stacking Ensemble Methods. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.10050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C. Enhancing Transaction Fraud Detection with a Hybrid Machine Learning Model. 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI); 2024; pp. 427–432. [Google Scholar]

- Talukder, M.A.; Khalid, M.; Uddin, M.A. An integrated multistage ensemble machine learning model for fraudulent transaction detection. Journal of Big Data 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of artificial intelligence research 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elreedy, D.; Atiya, A.F.; Kamalov, F. A theoretical distribution analysis of synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) for imbalanced learning. Machine Learning 2024, 113, 4903–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A.R.; Khedmati, M. A cluster-based SMOTE both-sampling (CSBBoost) ensemble algorithm for classifying imbalanced data. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L. Imbalanced Data Classification Based on Improved Random-SMOTE and Feature Standard Deviation. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papers with Code. IEEE CIS Fraud Detection Dataset. Online Repository, 2024.

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PloS one 2015, 10, e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinsztajn, L.; Oyallon, E.; Varoquaux, G. Why do tree-based models still outperform deep learning on typical tabular data? Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 507–520. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).