Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, Fungal Isolation and Availability

2.2. DNA Isolation for Genome Sequencing, Next Generation Sequencing and Genome Assembly

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

2.4. Phylogenomic Analyses

2.5. Mating-Type Locus Annotation

3. Results

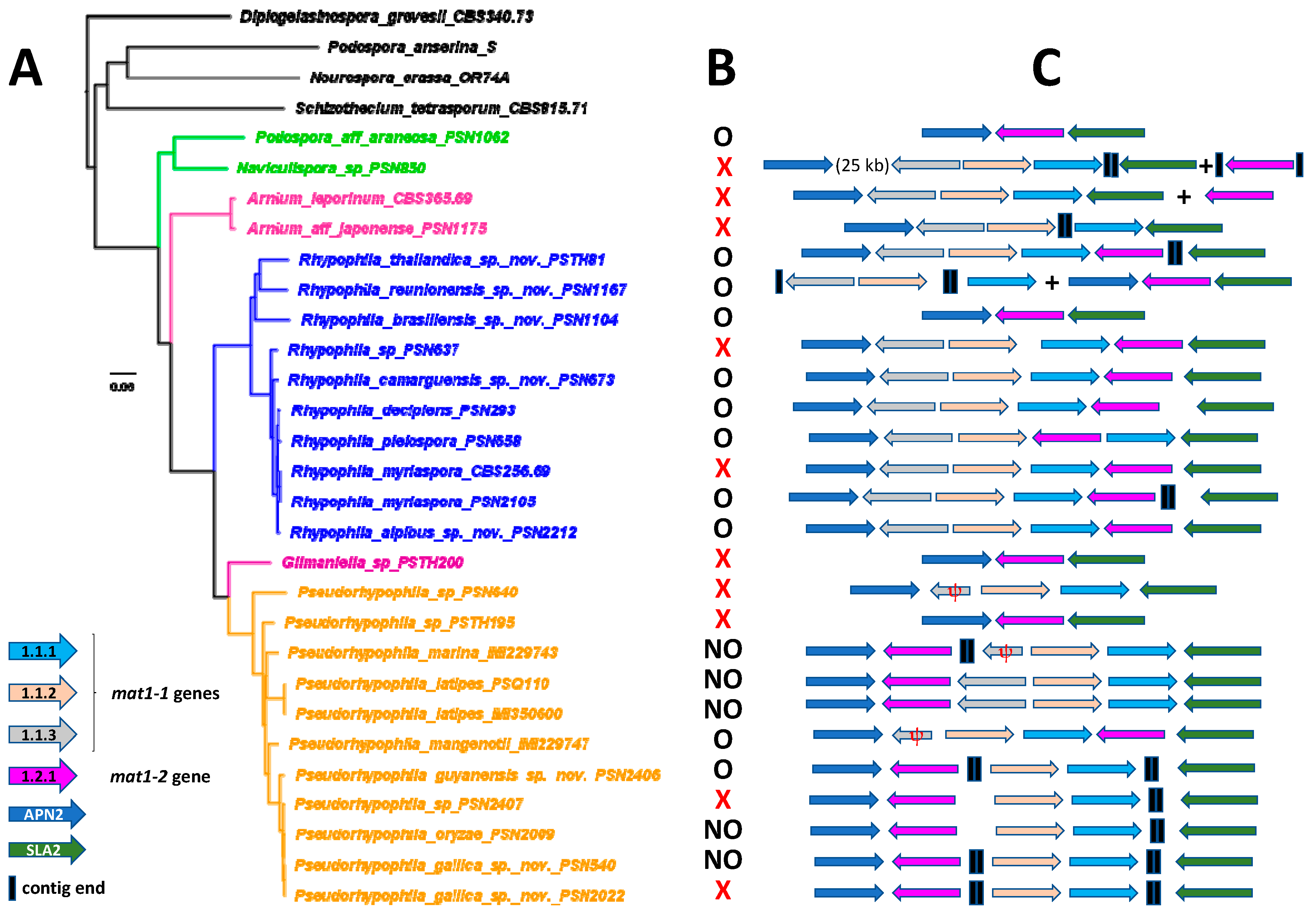

3.1. Fungal Isolates and Species Delimitation

- (1)

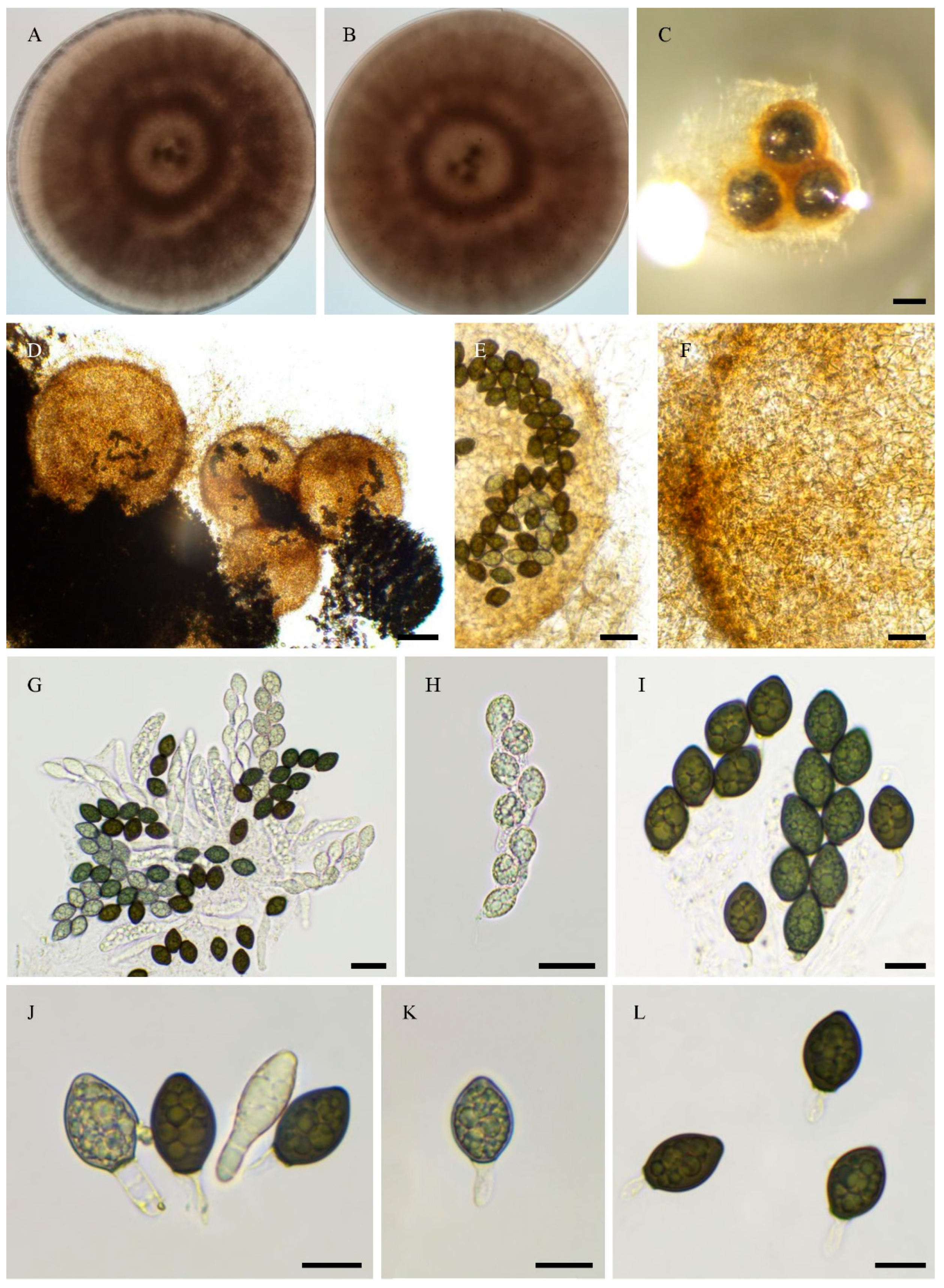

- six previously known species, two of which are newly placed in the Naviculisporaceae: R. myriaspora (PSN2105 and likely CBS 256.69), R. pleiospora (PSN658), P. latipes (formerly Z. latipes; IMI350600 and PSQ110), P. mangenotii (IMI229747), P. marina (IMI229743) and P. oryzae (formerly A. oryzae; PSN2009), adding to the previously sequenced R. decipiens (PSN293).

- (2)

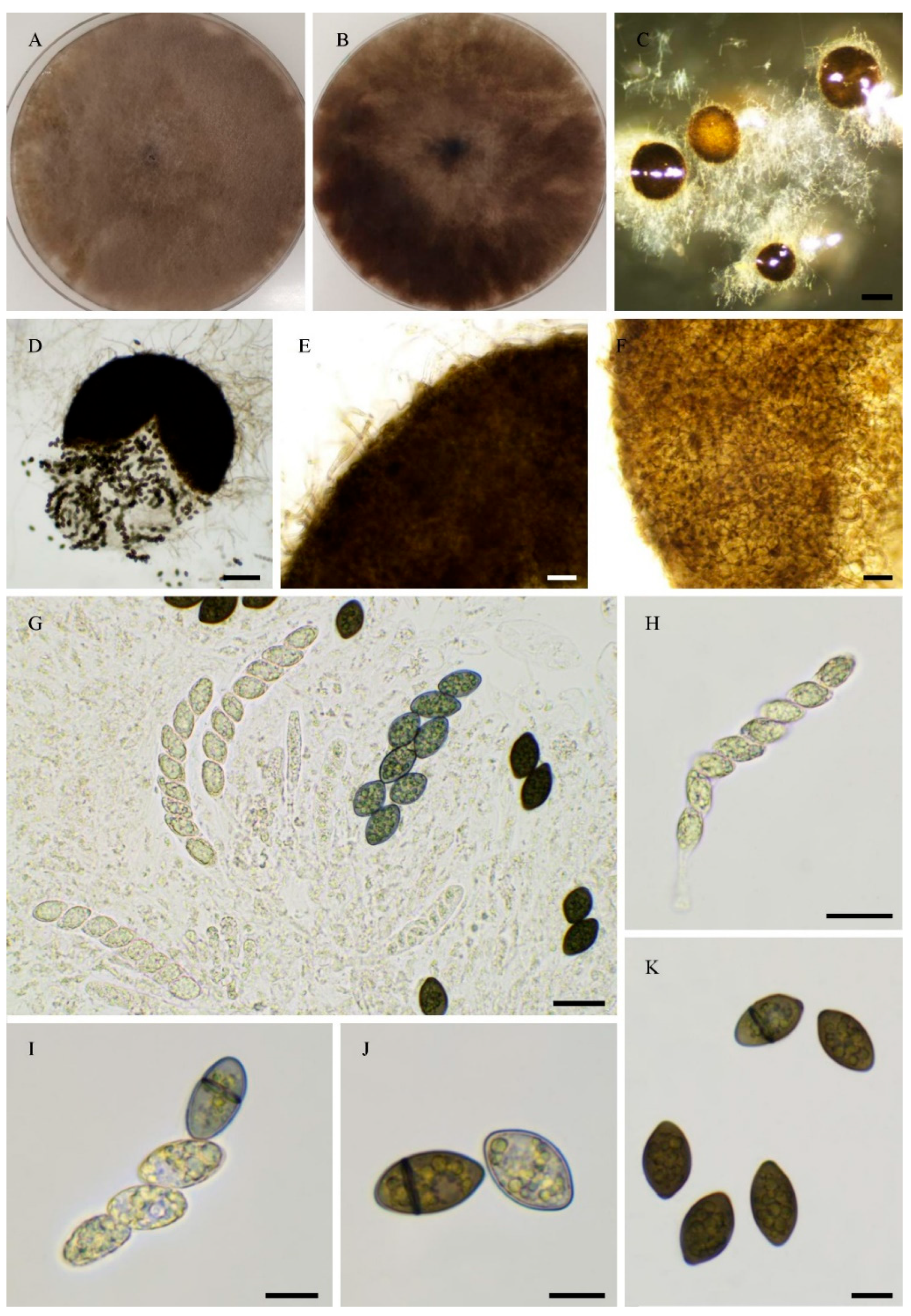

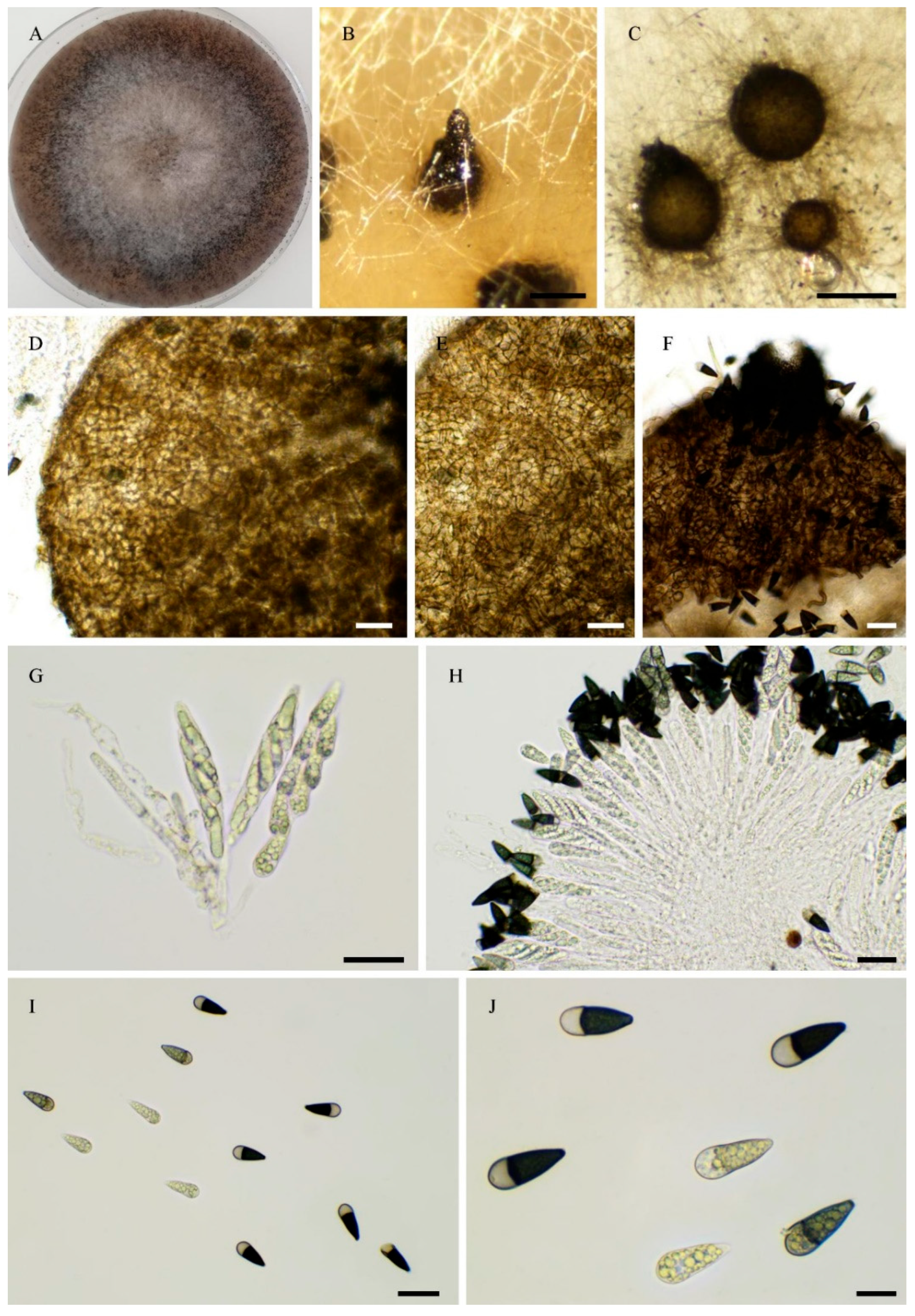

- seven new species including five Rhypophila species: R. thailandica sp. nov. (PSTH81), R. reunionensis sp. nov. (PSN1167), R. brasiliensis sp. nov. (PSN1104), R. camarguensis sp. nov. (PSN673) and R. alpibus sp. nov. (PSN2212), as well as two Pseudorhypophila ones: P. guyanensis sp. nov (PSN2406), and P. gallica sp. nov. (PSN540 and PSN2022).

- (3)

- eight newly-isolated strains awaiting further characterization, some of which may belong to species new to science: P. aff. araneosa PSN1062, Naviculispora sp. PSN850, A. aff. japonense PSN1175, Rhypophila sp. PSN637, Gilmaniella sp. PSTH200, Pseudorhypophila sp. PSN640, Pseudorhypophila sp. PSN2407 and Pseudorhypophila sp. PSTH195.

- (4)

- one collection strain: A. leporinum: CBS 365.69.

3.2. Phylogenomic Analysis

3.3. Mating-Type Locus Analysis

3.4. Taxonomy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANI | Average Nucleotide Identity |

| ITS | Internal Transcribed Spacer |

| kbp | Kilobase-pair |

| LSU | rDNA Large Subunit |

| RPB2 | RNA polymerase II subunit 2 |

| TUB2 | β-tubulin |

References

- Gostinčar, C. Towards Genomic Criteria for Delineating Fungal Species. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalanne, C.; Silar, P. FungANI, a BLAST-based program for analyzing average nucleotide identity (ANI) between two fungal genomes, enables easy fungal species delimitation. Fungal Genet Biol 2025, 177, 103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Kook, M.; Yi, T.H.; Yan, Z.F. Current Fungal Taxonomy and Developments in the Identification System. Curr Microbiol 2023, 80, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippo, E.; Gautier, V.; Lalanne, C.; Levert, E.; Chahine, E.; Hartmann, F.E.; Giraud, T.; Silar, P. Huge genetic diversity of Schizothecium tetrasporum (Wint.). N. Lundq.: delimitation of 18 species distributed into three complexes through genome sequencing. Mycosphere 2025, 16, 2936–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettman, J.R.; Jacobson, D.J.; Taylor, J.W. A MULTILOCUS GENEALOGICAL APPROACH TO PHYLOGENETIC SPECIES RECOGNITION IN THE MODEL EUKARYOTE NEUROSPORA. Evolution 2003, 57, 2703–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettman, J.R.; Jacobson, D.J.; Turner, E.; Pringle, A.; Taylor, J.W. REPRODUCTIVE ISOLATION AND PHYLOGENETIC DIVERGENCE IN NEUROSPORA: COMPARING METHODS OF SPECIES RECOGNITION IN A MODEL EUKARYOTE. Evolution 2003, 57, 2721–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettman, J.R.; Jacobson, D.J.; Taylor, J.W. Multilocus sequence data reveal extensive phylogenetic species diversity within the Neurospora discreta complex. Mycologia 2006, 98, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedberg, J.; Vogan, A.A.; Rhoades, N.A.; Sarmarajeewa, D.; Jacobson, D.J.; Lascoux, M.; Hammond, T.M.; Johannesson, H. An introgressed gene causes meiotic drive in Neurospora sitophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menkis, A.; Bastiaans, E.; Jacobson, D.J.; Johannesson, H. Phylogenetic and biological species diversity within the Neurospora tetrasperma complex. Journal of evolutionary biology 2009, 22, 1923–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, C.; Nguyen, T.-S.; Silar, P. Species delimitation in the Podospora anserina/P. pauciseta/P. comata species complex (Sordariales). Crypt. Mycol. 2017, 38, 485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Felix, Y.; Miller, A.N.; Cano-Lira, J.F.; Guarro, J.; García, D.; Stadler, M.; Huhndorf, S.M.; Stchigel, A.M. Re-Evaluation of the Order Sordariales: Delimitation of Lasiosphaeriaceae s. str., and Introduction of the New Families Diplogelasinosporaceae, Naviculisporaceae, and Schizotheciaceae. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, K.; Milic, A.; Stchigel, A.M.; Stadler, M.; Surup, F.; Marin-Felix, Y. Three New Derivatives of Zopfinol from Pseudorhypophila mangenotii gen. et comb. nov. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.W.; Yang, J.I.; Srimongkol, P.; Stadler, M.; Karnchanatat, A.; Ariyawansa, H.A. Fungal frontiers in toxic terrain: Revealing culturable fungal communities in Serpentine paddy fields of Taiwan. IMA Fungus 2025, 16, e155308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensen, N.; Bonometti, L.; Westerberg, I.; Brännström, I.O.; Guillou, S.; Cros-Aarteil, S.; Calhoun, S.; Haridas, S.; Kuo, A.; Mondo, S.; et al. Genome-scale phylogeny and comparative genomics of the fungal order Sordariales. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2023, 189, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egidi, E.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Plett, J.M.; Wang, J.; Eldridge, D.J.; Bardgett, R.D.; Maestre, F.T.; Singh, B.K. A few Ascomycota taxa dominate soil fungal communities worldwide. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundqvist, N. Nordic Sordariaceae S. Lat.; Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis: Uppsala, 1972; pp. 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Thiyagaraja, V.; Hyde, K.; Piepenbring, M.; Davydov, E.; Dai, D.; Abdollahzadeh, J.; Bundhun, D.; Chethana, K.; Crous, P.; Gajanayake, A. Orders of Ascomycota. mycosphere 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silar, P.; Gautier, V.; Lalanne, C.; Tangthirasunun, N.; Arthur, M.; Hartmann, F.E.; Giraud, T. The Podospora anserina species complex in metropolitan and overseas France with description of a new species, Podospora reunionensis sp. nov. Cryptogamie, Mycologie 2025, in the press.

- Silar, P. Podospora anserina. 2020. https://doi.org/.

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS computational biology 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.-J.; Yu, W.-B.; Yang, J.-B.; Song, Y.; dePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.-S.; Li, D.-Z. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biology 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, B. BBMap: a fast, accurate, splice-aware aligner; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2014.

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of computational biology : a journal of computational molecular cell biology 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature biotechnology 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, I.V.; Nikitin, R.; Haridas, S.; Kuo, A.; Ohm, R.; Otillar, R.; Riley, R.; Salamov, A.; Zhao, X.; Korzeniewski, F.; et al. MycoCosm portal: gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes. Nucleic acids research 2014, 42, D699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Molecular biology and evolution 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouan, P.L.; Crouan, H.M. Sordaria DNtrs. In Florule du Finistère; F. Klincksieck - J.B. & A. Lefournier: Paris & Brest, France, 1867.

- Abascal, F.; Zardoya, R.; Telford, M.J. TranslatorX: multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences guided by amino acid translations. Nucleic acids research 2010, 38, W7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castresana, J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Molecular biology and evolution 2000, 17, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A.M.; Darriba, D.; Flouri, T.; Morel, B.; Stamatakis, A. RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4453–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, R.F. Studies of coprophilous Sphaeriales in Ontario. University of Toronto, Toronto, 1934.

- Mirza, J.H.; Cain, R.F. Revision of the genus Podospora. Canadian Journal of Botany 1969, 47, 1999–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doveri, F. Fungi Fimicoli Italici; Associazione Micologica Bresadola: Trento, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.; Jeewon, R.; Hyde, K.D. Molecular systematics of Zopfiella and allied genera: evidence from multi-gene sequence analyses. Mycological Research 2006, 110, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, N. Tripterospora (Sordariaceae s. lat., Pyrenomycetes). Botaniska Notiser 1969.

- Huang, S.-K.; Hyde, K.D.; Mapook, A.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Bhat, J.D.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Jeewon, R.; Wen, T.-C. Taxonomic studies of some often over-looked Diaporthomycetidae and Sordariomycetidae. Fungal Diversity 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arx, v.J.A. On Thielavia and some similar genera of ascomycetes. Studies in Mycology 1975, 8, 1–29 + 22pl. [Google Scholar]

- Von Arx, J.; Hennebert, G. Triangularia mangenotii nov. sp. Bull. Soc. Mycol. France 1968, 84, 423–426. [Google Scholar]

- Furuya, K.; Udagawa, S. Two new species of cleistothecial Ascomycetes. Journal of Japanese botany 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Pöggeler, S.; Risch, S.; Kück, U.; Osiewacz, H.D. Mating-type genes from the homothallic fungus Sordaria macrospora are functionally expressed in a heterothallic ascomycete. Genetics 1997, 147, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett Richard, J.; Turgeon, B.G. Fungal Sex: The Ascomycota. Microbiology Spectrum 2016, 4, 10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0005-2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debuchy, R.; Berteaux-Lecellier, V.; Silar, P. Mating Systems and Sexual Morphogenesis in Ascomycetes. In Cellular and Molecular Biology of Filamentous Fungi; Borkovich, K., Ebbole, D., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, 2010; pp. 501–535. [Google Scholar]

- Cailleux, R. Champignons stercoraux de République Centrafricaine, III Podospora nouveaux. Cahier de la Maboké 1969, 7, 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Berka, R.M.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Otillar, R.; Salamov, A.; Grimwood, J.; Reid, I.; Ishmael, N.; John, T.; Darmond, C.; Moisan, M.C.; et al. Comparative genomic analysis of the thermophilic biomass-degrading fungi Myceliophthora thermophila and Thielavia terrestris. Nat Biotechnol 2011, 29, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Han, P.J.; Bai, F.Y.; Luo, A.; Bensch, K.; Meijer, M.; Kraak, B.; Han, D.Y.; Sun, B.D.; Crous, P.W.; et al. Taxonomy, phylogeny and identification of Chaetomiaceae with emphasis on thermophilic species. Studies in Mycology 2022, 101, 121–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steindorff, A.S.; Aguilar-Pontes, M.V.; Robinson, A.J.; Andreopoulos, B.; LaButti, K.; Kuo, A.; Mondo, S.; Riley, R.; Otillar, R.; Haridas, S.; et al. Comparative genomic analysis of thermophilic fungi reveals convergent evolutionary adaptations and gene losses. Communications biology 2024, 7, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aime, M.C.; Miller, A.N.; Aoki, T.; Bensch, K.; Cai, L.; Crous, P.W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Hyde, K.D.; Kirk, P.M.; Lücking, R.; et al. How to publish a new fungal species, or name, version 3.0. IMA Fungus 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M.I.; Powell, A.J.; Tsang, A.; O’Toole, N.; Berka, R.M.; Barry, K.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Natvig, D.O. Genetics of mating in members of the Chaetomiaceae as revealed by experimental and genomic characterization of reproduction in Myceliophthora heterothallica. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2016, 86, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain |

Species (other names*) |

Isolation year | Origin | Substrate | Sequencing palteform | Genome size (Mb) | Probable breeding system |

| PSN1062 | Podospora aff. araneosa | 2021 | Alps, France | Hare dung | Novogene | 40.3 | heterothallic |

| PSN850 | Naviculispora sp. | 2021 | Camargue, France | Horse dung | Novogene | 41.8 | heterothallic |

| CBS 365.69 | Arnium leporinum (Podospora leporina) | 1969 | The Netherlands | Rabbit dung | JGI | 48.5 | heterothallic |

| PSN1175 | Arnium aff. japonense | 2021 | Kobarld, Slovenia | Deer Dung | Biomics | 49.6 | heterothallic |

| PSTH81 | Rhypophila thailandica sp. nov. | 2023 | Ayuthaya, Thailand | Elephant dung | Novogene | 50.3 | homothallic |

| PSN1167 | Rhypophila reunionensis sp. nov. | 2022 | La Réunion Island, France | Cow dung | Novogene | 46.3 | heterothallic |

| PSN1104 | Rhypophila brasiliensis sp. nov. | 2021 | Campinas, Brazil | Capybara dung | Biomics | 45.9 | heterothallic |

| PSN637 | Rhypophila sp. | 2021 | Ontario, Canada | White rabbit dung | JGI | 46.9 | homothallic |

| PSN673 | Rhypophila camarguensis sp. nov. | 2021 | Camargue, France | Cow dung | Novogene | 45.9 | homothallic |

| PSN293$ |

Rhypophila decipiens (Podospora decipiens) |

2017 | Auvergne, France | Donkey dung | JGI | 47.1 | homothallic |

| PSN2105 | Rhypophila myriaspora | 2024 | Picardie, France | Horse dung | Novogene | 48.2 | homothallic |

| CBS 256.69 |

Rhypophila myriaspora (Rhypophila decipiens) |

1969 | The Netherlands | Rabbit dung | JGI | 48.3 | homothallic |

| PSN658 | Rhypophila pleiospora | 2021 | Ontario, Canada | Sylvillagus floridanus dung | JGI | 46.7 | homothallic |

| PSN2212 | Rhypophila alpibus sp. nov. | 2024 | Alps, Italy | Cow dung | Novogene | 47.9 | homothallic |

| PSTH200 | Gilmaniella sp. | 2023 | Chonburi, Thailand | Elephant dung | Novogene | 51.8 | heterothallic |

| PSN640 | Pseudorhypophila sp. | 2021 | Chad | Camel dung | JGI | 47.6 | heterothallic |

| PSTH195 | Pseudorhypophila sp. | 2023 | Chiang Rai, Thailand | Soil | Novogene | 50.6 | heterothallic |

| IMI229743 |

Pseudorhypophila marina (Zopfiella marina) |

1978 | Japan | Marine mud | JGI | 53.7 | homothallic |

| IMI350600 |

Pseudorhypophila latipes comb. nov. (Zopfiella latipes) |

1991 | U.K. | Not stated by the provider | Novogene | 52.3 | homothallic |

| PSQ110 | Pseudorhypophila latipescomb. nov. | 2019 | Québec, Canada | Soil | Novogene | 52.6 | homothallic |

| IMI229747 |

Pseudorhypophila mangenotii (Triangularia mangenotii) |

1978 | Japan | Soil | JGI | 54.3 | homothallic |

| PSN2406 | Pseudorhypophila guyanensis sp. nov. | 2025 | Guyane | Soil | Novogene | 52.6 | homothallic |

| PSN2407 | Pseudorhypophila sp.. | 2025 | Guyane | Soil | Novogene | 52.8 | homothallic |

| PSN2009 | Pseudorhypophila oryzae comb. nov. | 2024 | Centre-Val de Loire, France | Soil | Novogene | 56.2 | homothallic |

| PSN540 | Pseudorhypophila gallica sp. nov. | 2020 | Picardie, France | Soil | JGI | 55.4 | homothallic |

| PSN2022 | Pseudorhypophila gallica sp. nov. | 2024 | Centre-Val de Loire, France | Soil | Novogene | 54.6 | homothallic |

| Strain | Taxa | ITS | LSU |

| CBS 118394 | Apodospora peruviana | EU573703 | KF557665 |

| CBS 506.70T | Apodus deciduus | NR_145141.1 | NG_056953 |

| CBS 376.74 | Apodus oryzae | AY68120 | AY681166 |

| CBS 215.60 | Areotheca ambigua | AY999137 | AY999114 |

| UAMH 7495 | Areotheca areolata | AY587911 | AY587936 |

| Lundqvist 7098-e | Arnium caballinum | NA | KF557672 |

| SANK 10273 | Arnium japonense | NA | KF557680 |

| Lundqvist20874-c | Arnium mendax | NA | KF557687 |

| E00122117 | Arnium mendax | NA | KF557688 |

| NBRC 9235T | Gilmaniella humicola | available at https://www.nite.go.jp/nbrc/catalogue/ | |

| CBS 137295T | Naviculispora terrestris | MT784136 | KP981439 |

| NTUPPMCC 22-297T | Pseudorhypophila formosana | PV476805 | PV476867 |

| CBS 155.77T | Pseudorhypophila marina | MK926851 | MK926851 |

| CBS 698.96 | Pseudorhypophila marina | MK926853 | MK926853 |

| CBS 413.73T | Pseudorhypophila pilifera | MK926852 | MK926852 |

| CBS 419.67T | Pseudorhypophila mangenotii | MT784143 | KP981444 |

| CBS 249.71 | Rhypophila cochleariformis | AY999123 | AY999098 |

| CBS 258.69 | Rhypophila decipiens | KX171946 | AY780073 |

| TNM F17211 | Rhypophila myriaspora$ | EF197083 | NA |

| TNM F16889 | Rhypophila pleiospora | EF197084 | NA |

| F-116,361 | Sordaria araneosa | FJ175160 | NA |

| IFO9826 | Zopfiella latipes | AY999129 | AY999107 |

| PSN2212 | PSN2105 | CBS 256.69 | PSN293 | |

| PSN658 | 94.99% | 95.07% | 95.08% | 95.17% |

| PSN2212 | 95.08% | 95.09% | 95.21% | |

| PSN2105 | 99.74% | 95.20% | ||

| CBS 256.69 | 95.20% |

| PSQ110 | IMI350600 | IMI229747 | PSN2406 | IMI229743 | PSN540 | PSN2022 | PSN2407 | PSN2009 | |

| PSTH195 | 87.90% | 88.47% | 88.49% | 87.75% | 89.14% | 87.86% | 87.86% | 87.85% | 87.87% |

| PSQ110 | 99.26% | 87.91% | 87.25% | 88.36% | 87.34% | 87.36% | 87.28% | 87.42% | |

| IMI350600 | 87.93% | 87.25% | 88.37% | 87.38% | 87.38% | 87.32% | 87.46% | ||

| IMI229747 | 88.25% | 89.02% | 88.35% | 88.36% | 88.35% | 88.35% | |||

| PSN2406 | 87.78% | 94.18% | 94.18 | 94.10% | 94.00% | ||||

| IMI229743 | 87.90% | 87.91% | 87.84% | 87.95% | |||||

| PSN540 | 98.69%* | 96.28% | 97.26% | ||||||

| PSN2022 | 96.43% | 97.30% | |||||||

| PSN2407 | 96.44% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).