1. Introduction

As human populations grew and suitable habitats declined, wolves (Canis lupus) were eradicated in Central Europe. In an effort to protect land and livestock from wolf attacks, human activities reduced wolf populations to a few remaining groups, primarily in the Apennines of Italy, in Spain, and some regions of Eastern Europe. The largest remaining population persisted in Eastern Europe, where human population density is relatively low at around 16 inhabitants per km² [

1,

2,

3].

In 1992, the wolf was granted protected status in Europe [

4], marking the beginning of its recolonisation of Central Europe. Wolves from the Italian population crossed the Alps and expanded into France, while wolves from the Baltic population, located in northeastern Poland, migrated to eastern Germany, where the first wolf pack was established in 2020 [

5].

In Belgium, a wolf was observed passing through Namur in 2011. In early 2018, wolf GW680f established residence at the air-force shooting range spanning Houthalen-Helchteren and Leopoldsburg in Flanders. Originating from northern Germany, travelling through the Netherlands, she became the first wolf to settle officially in Belgium. Since then, multiple wolves have either passed through or settled in Belgium, leading to the formation of several resident packs [

1].

Belgium (385 residents per km²) and especially Flanders (the north region of Belgium, 504 residents per km²) [

6], is a densely populated and highly urbanized area. This high human density creates significant challenges for human-wolf coexistence. Several wolves have been killed in traffic accidents. Professionals, hobby farmers, and owners of horses and small ruminants have raised concerns about potential wolf attacks on their animals [

4,

7]. From 20 January 2018, when the first official wolf arrived in Flanders, to 31 December 2024, a total of 305 cases of confirmed wolf attacks occurred in Belgium. The majority of these incidents (N = 298; 97.7%) occurred in the two provinces Limburg and Antwerp, where 645 animals were killed, 86 were wounded, and 25 went missing. Most victims were sheep (N = 597; 79.0%), although a variety of other domestic species were also affected [

8].

Several authors have concluded that dispersing wolves attack livestock more frequently compared to settled animals. Dispersing wolves are typically young animals that have left their natal pack in search of a new territory or pack. Due to their age, they are often inexperienced hunters. Moreover, as they are unfamiliar with the environments they traverse, livestock may be more at risk [

2,

9]. However, in Belgium, most livestock attacks (N = 207; 67.9%) have been attributed to the resident pack in the air force shooting range, while dispersing wolves accounted for only 12.5% of the confirmed attacks [

8]. In order to analyse the situation properly, it is also necessary to consider other factors, such as the availability of wildlife, fencing, and other livestock protection measures.

Part of the air force shooting range in Houthalen-Helchteren is a non-forested heathland area [

10]. Extensive sheep grazing plays a vital role in preserving this ecosystem, contributing to biodiversity and maintaining the landscape [

11]. Since the arrival of wolves in the area, sheep management practices have changed. Rather than being herded by a shepherd with dogs, the sheep are now kept in temporary pastures enclosed with electric fencing [

12]. Following continued wolf attacks, the shepherd introduced several livestock guardian dogs to protect the flock.

This study aimed to describe wolf behaviour near a protected sheep flock in relation to the sheep, electric fencing, and livestock guardian dogs. Specifically, we assessed whether wolves were deterred by electric fencing, how livestock guardian dogs influenced their behaviour, and the extent to which frequent human presence affected wolf activity. Although livestock depredation by dispersing wolves is often more frequent due to inexperience, in Belgium most confirmed cases are linked to the settled Hechtel-Eksel pack. This contrast highlights the importance of context-specific monitoring and protection strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location

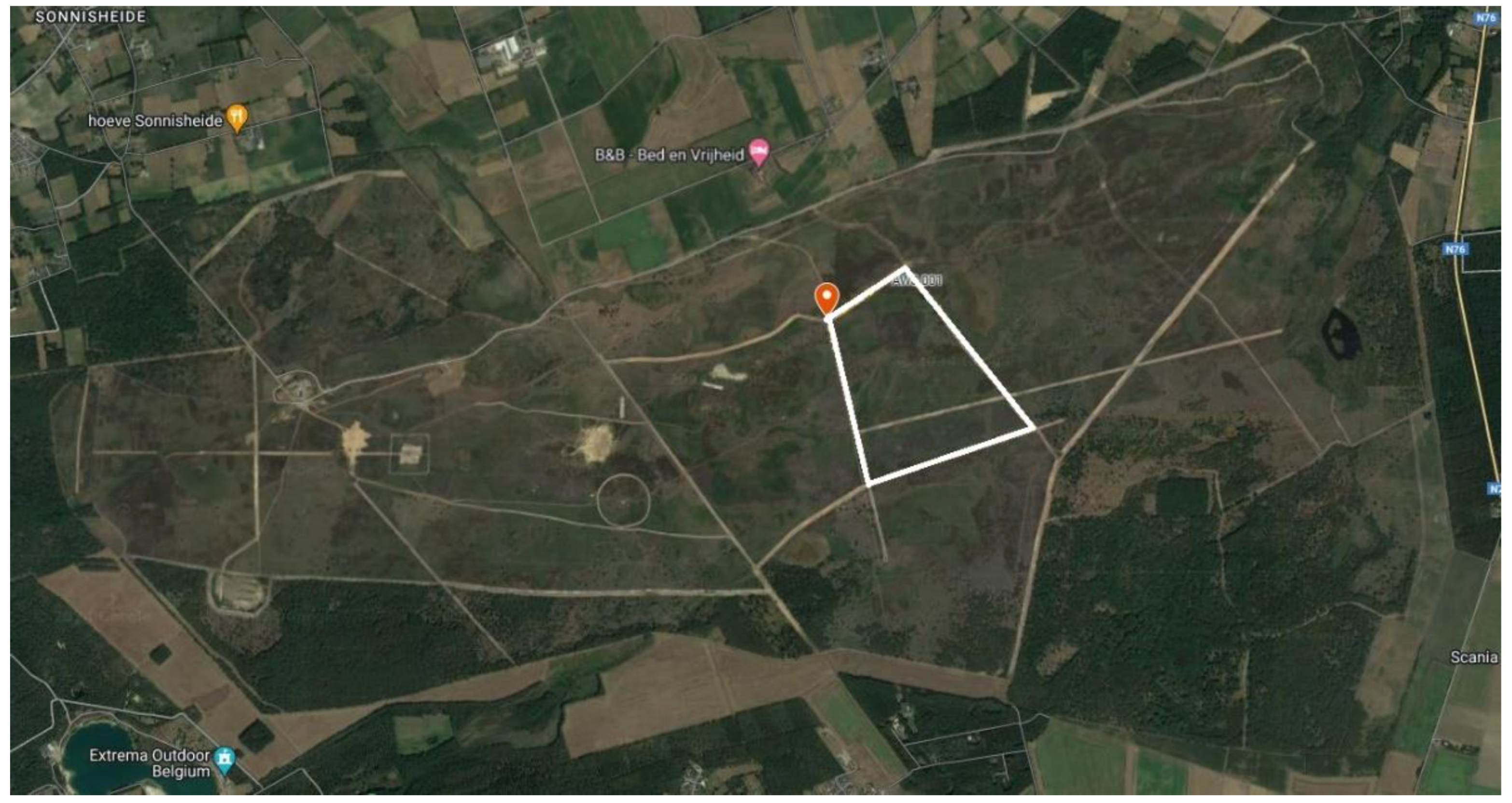

The study was conducted at the Belgian Air Force shooting range in Houthalen-Helchteren, Belgium, from 4 September to 19 September 2023. The shooting range covers an area of 2,180 hectares, of which 961 hectares are located in Houthalen-Helchteren and 1,219 hectares in Oudsbergen [

13]. The area is managed by the air force base. The natural environment primarily consists of heathland, interspersed with woodland and farmland (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) [

10].

Due to flight and target practice activities, an unobstructed view of the area is essential. To help maintain the natural landscape, a local shepherd herds sheep through the heathland and woodland to control vegetation growth and reduce fire risk.

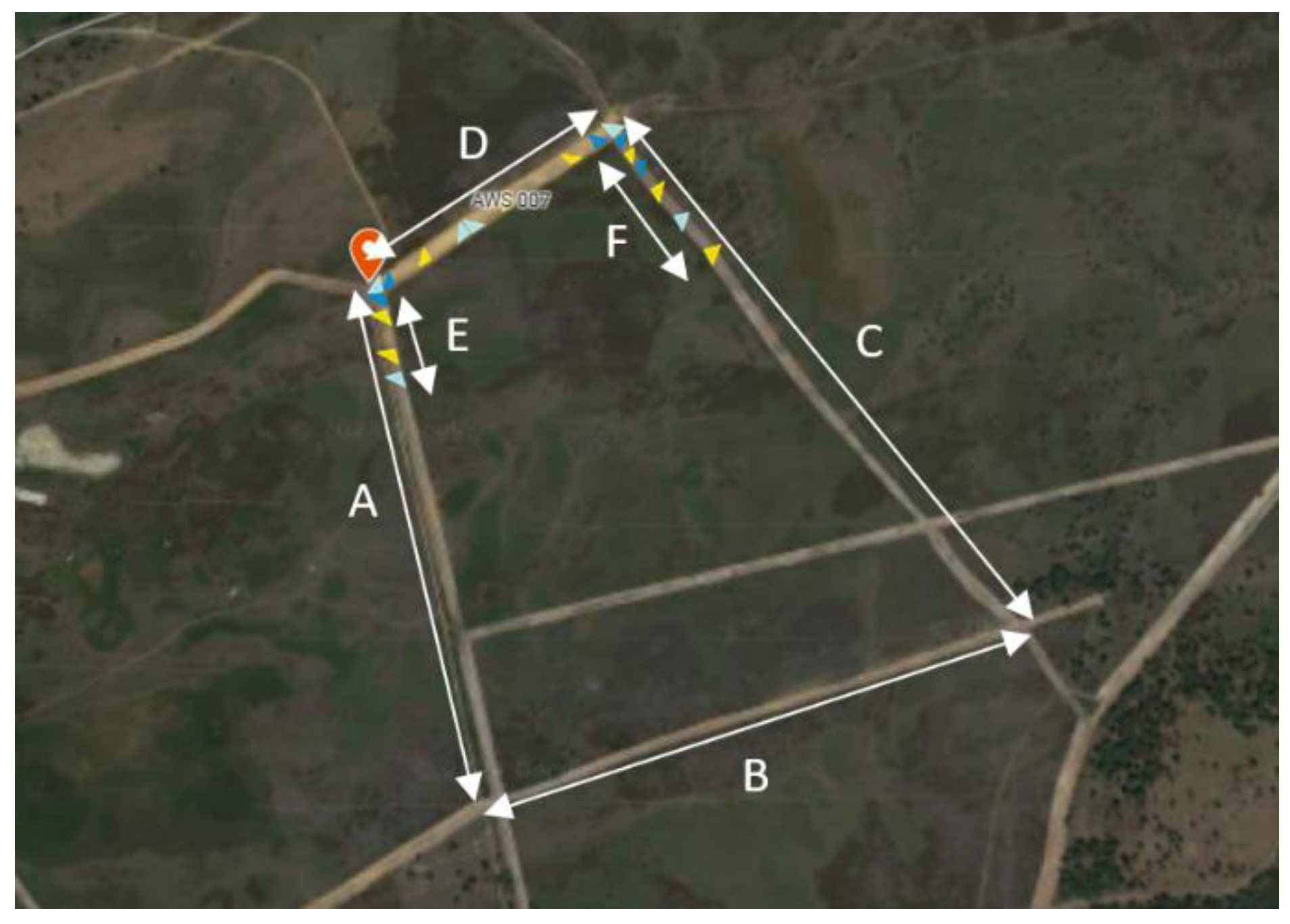

Since the return of wolves to the area, the sheep have been protected by livestock guardian dogs, and free grazing has been replaced by temporary grazing pastures. During the study period, the sheep were placed in a pasture located on heathland, covering an area of 0.7 km² with a perimeter of 3.7 km. Sandy roads running through the area served as boundaries, with the fence installed on the inner side of the roads.

The pastures were enclosed by electric fencing, installed according to anti-wolf fencing guidelines [

12]. Plastic poles were placed along the sandy roads, alternating with wooden poles. Five electric wires were attached to the poles, with the lowest wire positioned less than 20 cm above the ground and the highest more than 120 cm above the ground.

The spacing between the wires was 20 cm for the lower wires and 30 cm for the upper wires. The voltage was measured at 6,300 V, exceeding the recommended minimum of 4,500 V [

12]. Voltage levels were checked daily by both the shepherd and a park ranger.

Along the sandy road, vegetation was sparse, and there was no interference with the functionality of the electric fence due to physical contact with plants or grasses. The fence was installed on 2 September 2023, and removed on 19 September 2023.

Cameras were positioned on the inner edge of the fence, at a distance of 1 to 1.5 meters from it. They were mounted on wooden poles at a height of approximately 1.5 meters, facing the sandy road and the area outside the fence. The cameras monitored the shortest side of the pasture (625 m), as well as 140 m and 240 m sections of the longer sides (lines D, E, and F in

Figure 3).

2.2. Sheep

From 5 September to 15 September 2023, the sheep remained in the pasture both day and night. On a daily basis, the shepherds checked the flock to ensure the animals were healthy. The flock comprised 764 ewes and 6 rams, with ages ranging from 19 months to 9 years. The breed in question was Flemish Sheep, known for their high fertility rates and wool production. The average weight of the ewes was 75 kg, with a withers height of 73 cm, while the rams averaged 90 kg in weight and had a withers height of 78 cm [

14].

2.3. Livestock Guardian Dogs

The flock was continuously accompanied by livestock guardian dogs—specifically, six Spanish Mastiffs aged between three and ten years. The addition of three dogs to the flock occurred in 2019, with a further three joining in 2022. Male Spanish Mastiffs have an average height of 77 cm at the withers, while the average height of their female counterparts is 72 cm [

15]. All six dogs were spayed or neutered and comprised three males and three females.

2.4. Wolf Pack

The established wolf pack residing at the military training ground is known as the Hechtel-Eksel pack. In 2023, it consisted of a female wolf, GW1479f, and a male wolf, GW979m, who had formed a breeding pair, along with their offspring [

16].

Wolf GW979m first appeared in Belgium in August 2018 after traveling through Germany and the Netherlands. Although his exact origin was unknown, it was believed that he came from western Poland [

17]. Upon arrival in Belgium, he initially paired with GW680f, who later disappeared after becoming pregnant and possibly giving birth [

18]. GW1479f originated from Gohrischheide, Germany, and migrated to Belgium in December 2019. She formed a breeding pair with GW979m, and together they produced four litters. Several pups from these litters died in traffic accidents [

19,

20].

The fourth and final litter, estimated to consist of seven pups, was born in April 2023 [

21]. On 26 July 2023, GW979m was struck and killed by a car [

22], leaving GW1479f to care for the litter alone. The pups, approximately 3 months old at the time, likely remained close to the den site [

23]. During this period, GW979m would typically have provided food for the nursing female and her pups through regurgitation.

In the month following GW979m’s death, GW1479f was confirmed to have killed two sheep and a pony [

8]. At the time of this study, she was still residing in the area with her four surviving pups.

2.5. Monitoring Devices

Nineteen cameras were placed along the edge of the pasture, inside the fence line, as previously described (

Figure 4 and

Table 1). Recording commenced on 4 September 2023 at approximately 13:30. To get more detailed information, six additional Suntek cameras were installed later in the study period, on 15 September 2023 at around 10:00. All cameras were deactivated and removed on 19 September 2023. Infrared sensors (940 nm) were beyond the wolf’s visual sensitivity range and thus presumed invisible to them [

24].

The cameras were equipped with a passive infrared (PIR) sensor. When triggered, the sensor first captured a photograph, followed by a 30-second video recording.

2.6. Monitoring Procedure

On 4 September 2023, a total of 13 cameras (8 Denver WCT-8020W and 5 Numaxes) were activated at the previously described locations at approximately 13:30 (

Figure 5). On the morning of 15 September 2023, the 6 additional cameras (Suntek) were installed and activated. All cameras remained operational until 19 September 2023, when they were removed during the dismantling of the electric fence.

The sheep and livestock guardian dogs were placed in the pasture on the afternoon of 5 September 2023, and remained there until the afternoon of 15 September 2023, when they were moved to another pasture in the area. The electric fence was powered and monitored daily during the presence of the sheep. However, after the sheep were relocated, supervision of the fence ceased, and by the time it was dismantled, the battery had been depleted. The exact time at which the power supply failed is therefore unknown.

A total of 3,448 photographs and video recordings were reviewed and analysed between November 2023 and September 2025. Some images captured during nighttime were too dark, prompting adjustments to the camera settings to improve image clarity and enhance visibility.

An Excel spreadsheet was used to record and organise the data. Each image was listed by camera and timestamp, and the entries were arranged in chronological order. The following observations were recorded:

Table 2.

Observations listed in Excel Spreadsheet.

Table 2.

Observations listed in Excel Spreadsheet.

| Animal or human activity |

Yes or no |

| Wolf |

Number: 1, 2 or 3 |

|

Time of activity: morning, afternoon, evening or night |

|

Activity: walking, jogging, observing ground, observing fence or observing something else |

|

Location: next to fence, in tire track, behind tire track, close to or in the vegetation |

|

Direction: towards the camera, away from the camera or other |

|

Distance from the fence: close, a few meters from the fence or far |

|

Electricity present on fence: unknown, yes or no |

|

Sheep and dogs present in pasture: yes or no |

| Vehicle |

Appearance vehicle: description |

|

Number: 1,2,3,4 or multiple |

|

Owner: shepherd, military, ANB or unknown |

|

Direction: towards the camera, away from the camera or other |

|

Leaving vehicle: yes, no or unknown |

| Human |

Who: shepherd, ANB, horseback rider, hikers or unknown |

|

Number: 1,2,3,4, multiple or unknown |

|

Measuring electricity: yes, no or unknown |

|

Activity: installation camera, tearing down fence, feeding or looking after the dogs, observing the ground, taking pictures, walking, talking or other |

| Livestock guardian dog |

Number: 1,2,3,4 or multiple |

|

Actively guarding: yes or no |

|

Other activity: lying or sitting, walking or running, observing environment, sniffing, urinating, being around people or sitting in trailer |

| Sheep |

Number: 1 to 17 or flock |

|

Activity: walking, grazing, ruminating, lying, observing environment, sniffing or other |

| Other |

Other visual observations |

| Audio |

Auditorial observations |

| Light |

Daylight, dark or twilight |

| Weather |

Sunny, cloudy, rain, fog or unspecified |

The data were processed using R statistical software (version 4.3.1, 2023) to calculate percentages and frequencies, and to create visualizations [

25].

3. Results

3.1. Monitoring Devices

3.1.1. Images

Across the 16-day monitoring period, 3,448 images were obtained, comprising 1,751 photographs and 1,697 videos.

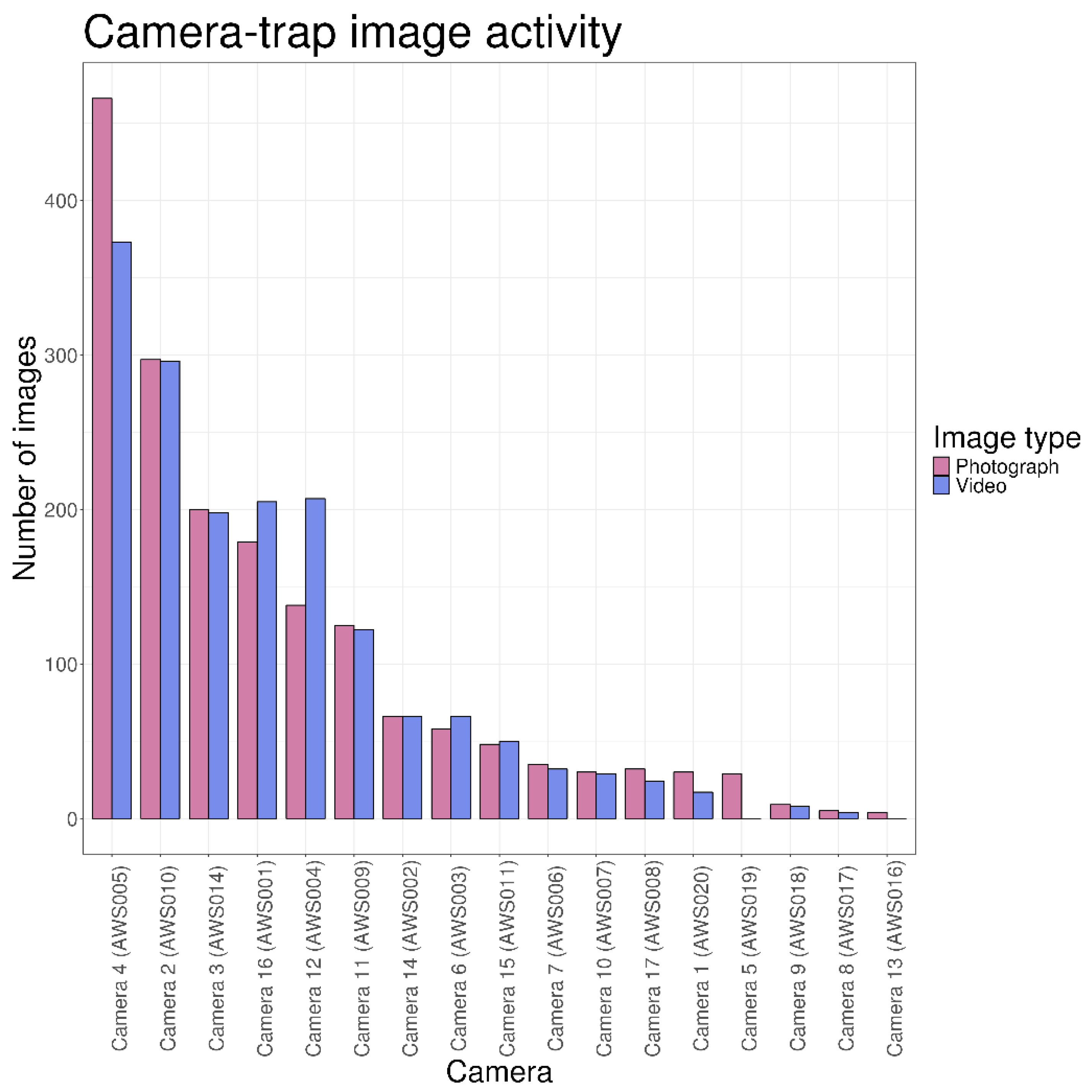

Figure 6 shows the distribution of images across the cameras. Two cameras (AWS016 and AWS019) recorded only photographs and no video footage. Two other cameras (AWS015 and AWS012) recorded no images during their installation period. Camera 4 (AWS005) captured the highest number of images of all devices. In contrast, the six cameras installed later in the study, on 15 September 2023 (AWS015, AWS016, AWS017, AWS018, AWS019, and AWS020), captured a significantly lower number of images, which may be attributable to their shorter period of activity.

Of all images, 89.2% (N = 3,074) followed the intended sequence of a photograph immediately followed by a video fragment. In 6.21% of the images (N = 214), photographs are not accompanied by a video fragment, and in 4.64% (N = 160) only a video was recorded. On average, 85.1% of the images captured by a camera are photographs, with the remaining 14.9% being videos.

Ratios of the number of photos to the number of videos for each camera range from zero to 1.50. It appears that cameras AWS016 and AWS019 did not make any video recordings during the study. Other cameras, on the other hand, demonstrated a higher tendency to capture videos than photographs.

For the photographs, two outcomes were possible: either no visible activity was detected—meaning no presence of humans, animals, or other forms of motion—or at least one form of visible activity was recorded. For the video recordings, a third outcome was possible: no visible activity, but presence of audio signals.

No visible activity was detected in 1,377 of the 3,448 images (N = 1,377; 39.9%). Of these, 664 were video recordings that contained audio fragments from which context could be inferred (N = 664; 48.2%). For example, in some videos, sheep could be heard bleating as they passed the camera, suggesting that the motion sensor was triggered by their presence just outside the camera’s field of view. The auditory material collected was not indicative of vocalisations made by wolves.

3.1.2. Sounds

With the exception of one video, all videos contain audio. The most common audio sources were the electric fence (N = 924; 54.5%), sheep (N = 527; 31.1%), and livestock guardian dogs (N = 84; 4.95%). Of the 527 videos containing sheep sounds, 311 also showed sheep (N = 311; 59.0%), ranging from a single sheep to a whole flock. However, none of the recordings provided evidence of wolf vocalisations. A recurring unidentified beeping sound was detected in 468 videos (N = 468; 27.6%). In addition to these sounds, 375 videos also contain other sounds, including, but not limited to, a plane flying over, a ringtone of a phone, the sound of galloping horses and people talking (N = 375; 22.1%).

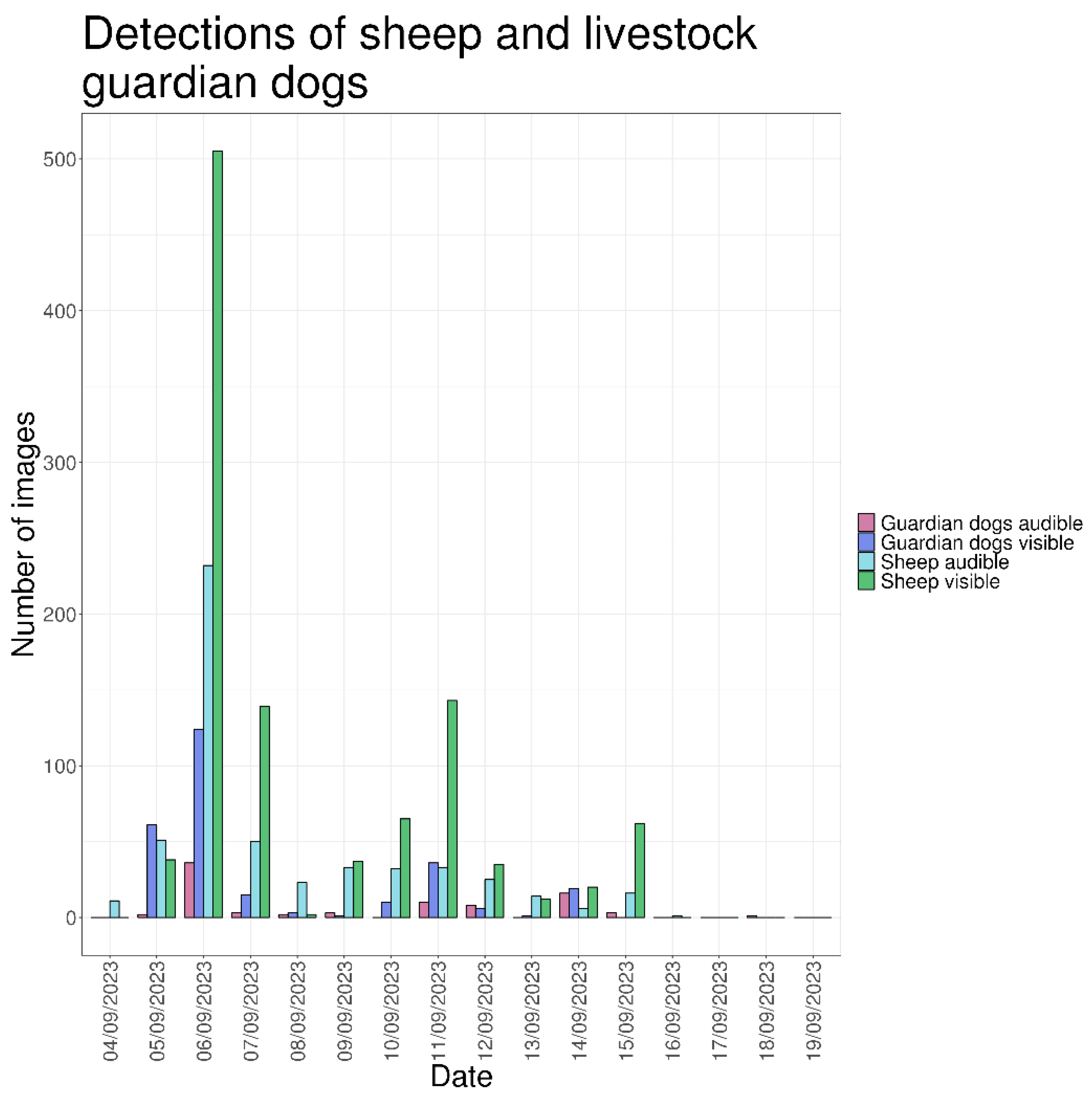

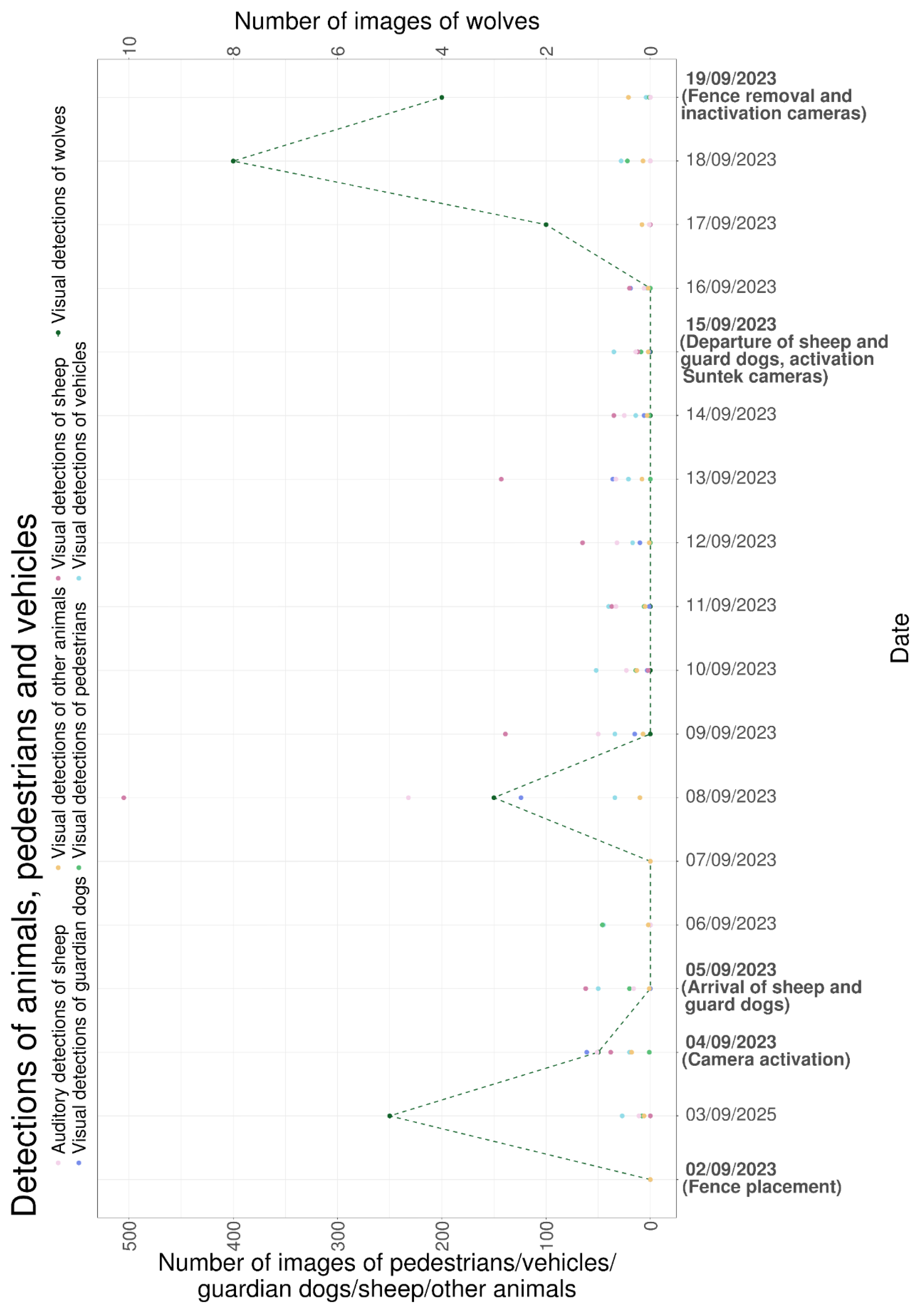

On 6 September 2023, the day after the flock of sheep was introduced to the site, the sheep and livestock guardian dogs were observed to be particularly vocal with more than 250 videos containing sounds produced by the sheep (

Figure 7).

3.2. Light

The majority of images were captured during daylight (N = 2,835; 82.2%), 285 were taken during twilight (N = 285; 8.27%), and 252 images (N = 252; 7.31%) were recorded at night (

Figure 8). The remaining 76 images (N = 76; 2.20%) could not be classified due to unclear lighting conditions, caused by factors such as condensation on the camera lens or technical failure.

Wolf detections occurred primarily at night (N = 15; 65.2%), with the remainder during daylight (N = 8; 34.8%). In contrast to the wolves, sheep were mainly detected during daylight hours (N = 907; 86.6%) and occasionally during twilight (N = 140; 13.4%). As with the sheep, the livestock guardian dogs were primarily detected during daylight hours (N = 174; 63.3%), but they also triggered the cameras during twilight (N = 37; 13.5%) and night (N = 64; 23.3%).

3.3. Weather Conditions

The majority of images (N = 2,305; 66.9%) were captured under sunny conditions, followed by cloudy (N = 734; 21.3%), foggy conditions or when the camera lens was misted (N = 140; 4.06%), and during rain (N = 3; 0.0906%). The measured temperature ranged from as low as 6.37 °C, which is recorded at approximately 4:50 on 15 September 2023 to as high as 32.5 °C, which is recorded in the afternoon of 10 September 2023.

In 21.7% of incidents where wolves were detected, the presence was noted under overcast skies. This dropped to 8.70% in cloudy conditions, and to 4.35% under sunny conditions. In 78.3% of occurrences, the temperature ranged between 12.8 °C and 18.6 °C.

Regarding the weather conditions in which sheep and livestock guardian dogs were observed, the majority of the images were recorded in sunny conditions (sheep: N = 902; 85.3%, livestock guardian dogs: N = 166; 60.1%), with cloudy weather being the second most common (sheep: N = 100; 9.45%, livestock guardian dogs: N = 42; 15.2%). The temperature range when sheep were present was from 17.3 °C to 30.5 °C. For the livestock guardian dogs it was 11.6 °C to 29.8 °C.

3.4. Animals

3.4.1. Wolves

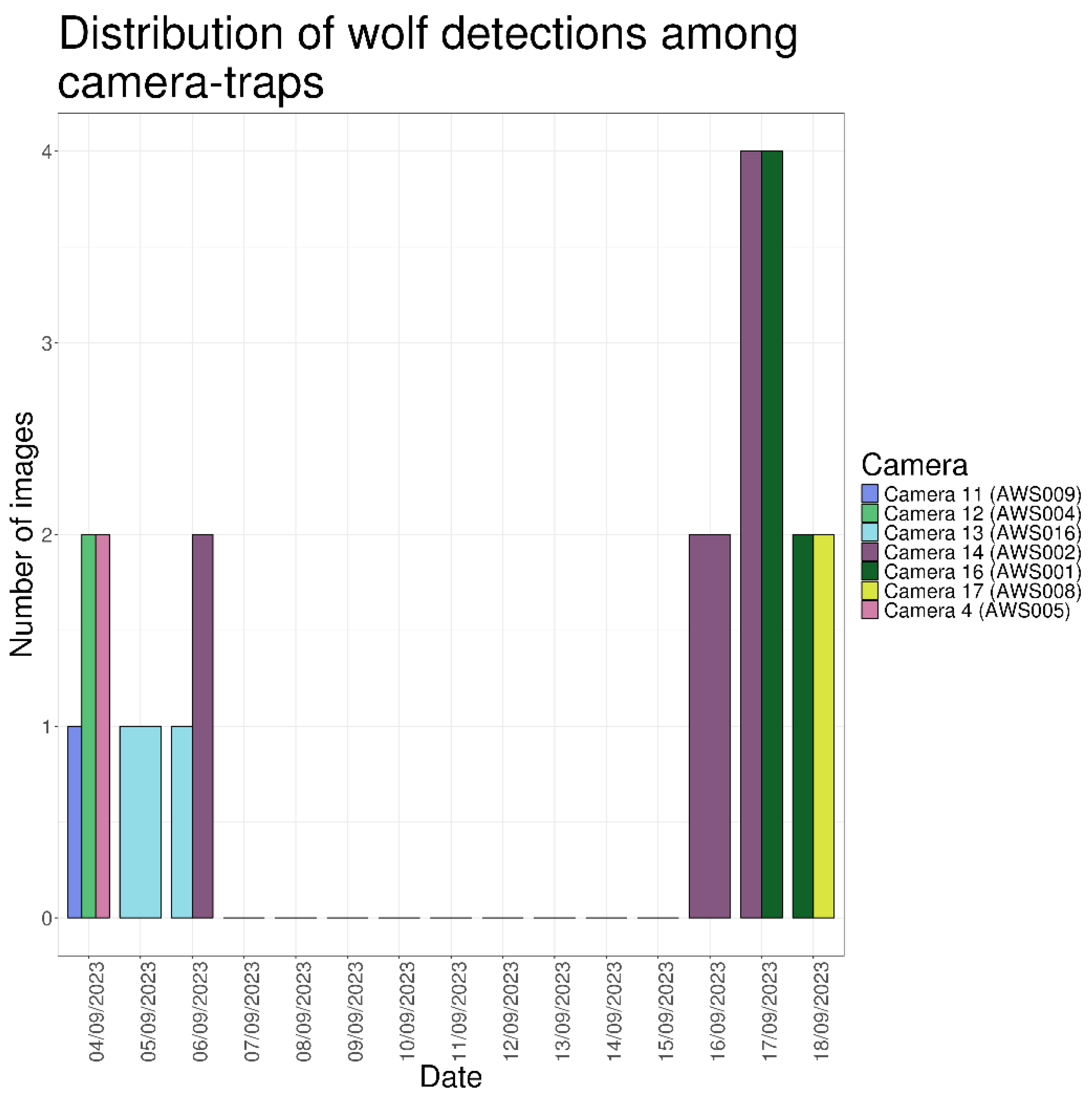

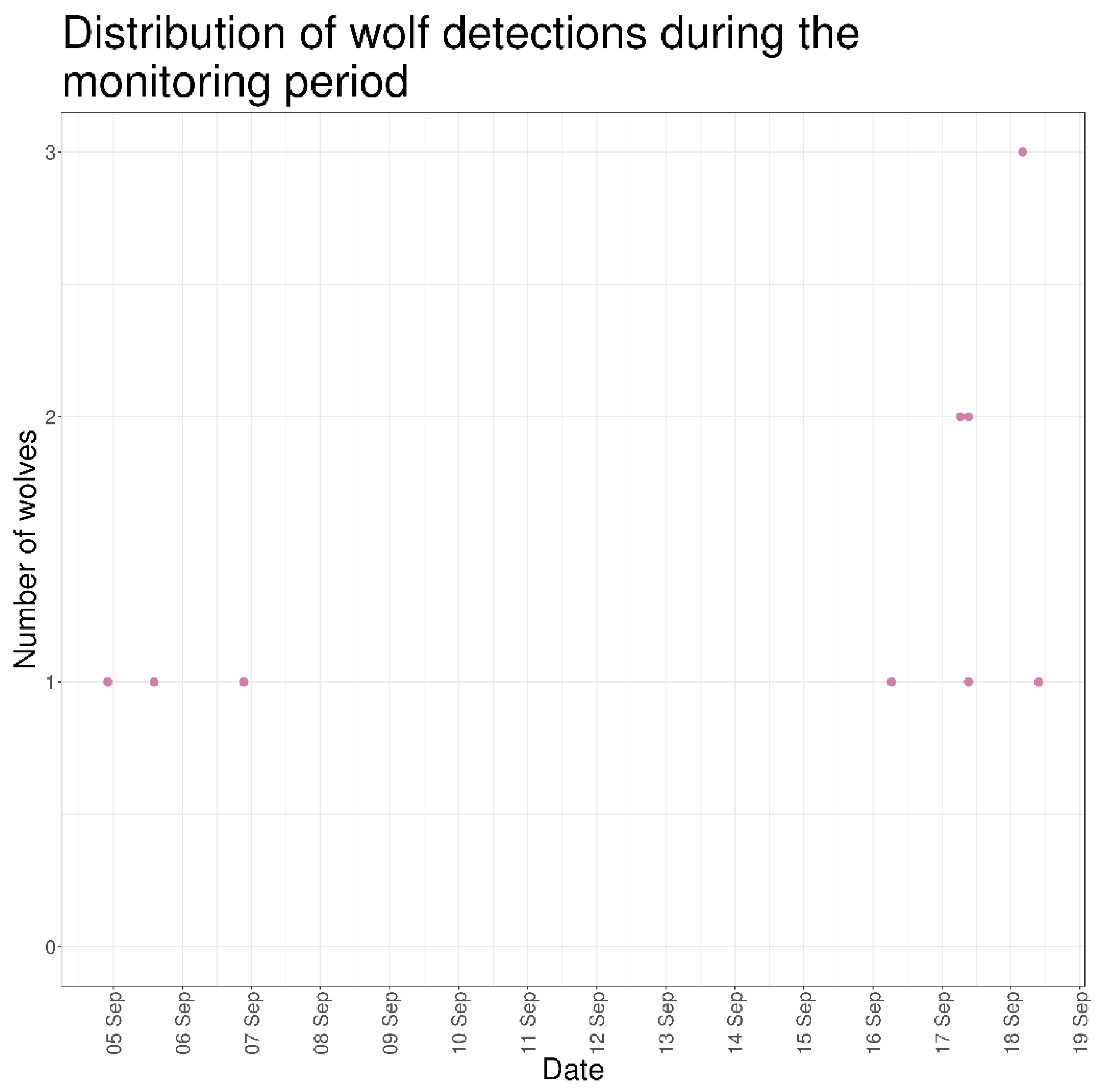

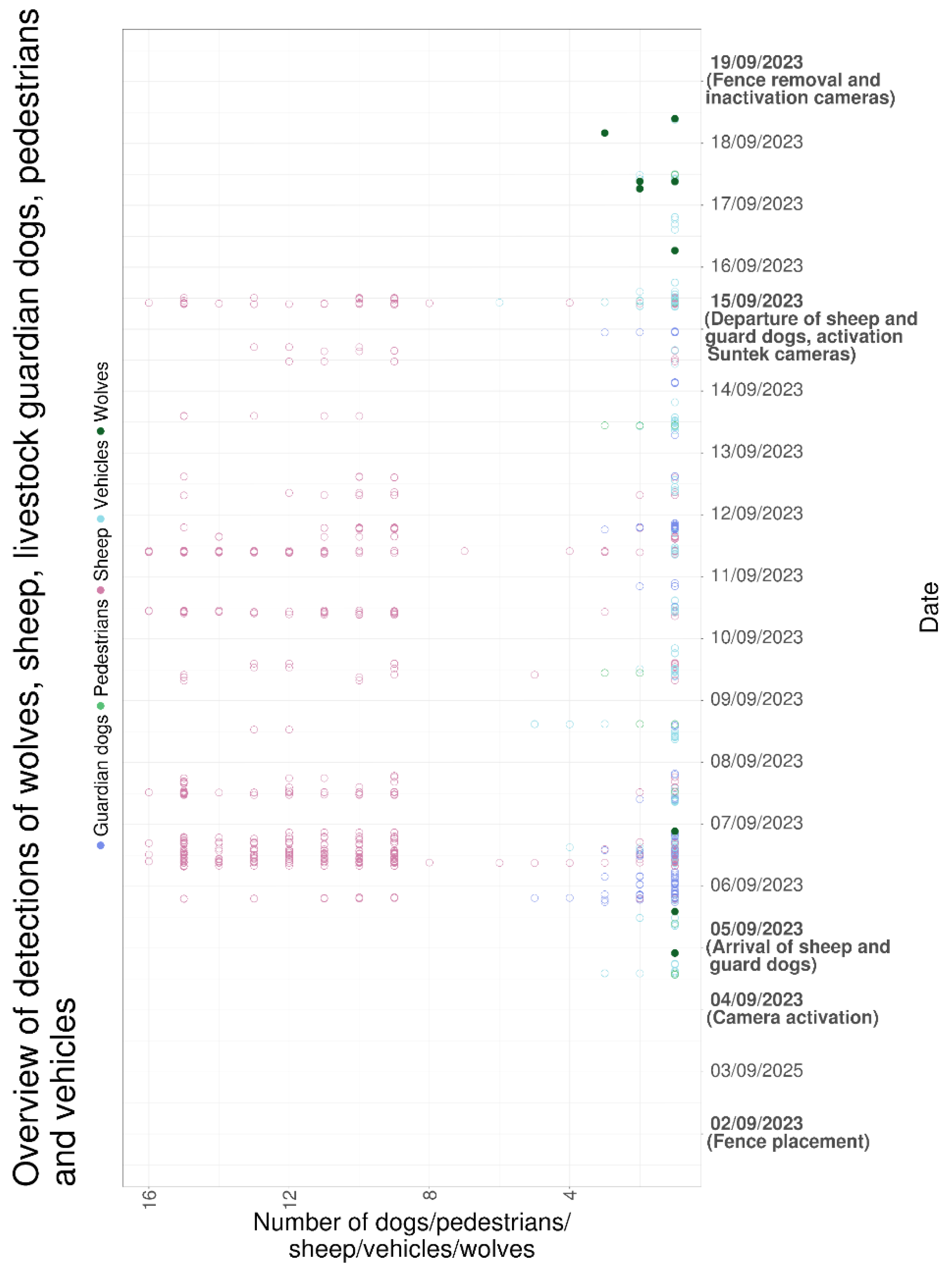

Wolves were detected in 23 images over 6 days of observation, in two distinct periods: the first 3 days (from 4 to 6 September 2023) and 3 days after the sheep’s removal (from 16 to 18 September). In 8 instances, a wolf was visible in both the photograph and the subsequent video triggered by the same PIR sensor activation; in 7 instances, only one format contained at least one wolf.

Figure 9 demonstrates the number of images containing wolves captured by the cameras. As is apparent from the data obtained, the wolf was predominantly captured by cameras 14 (AWS002) and 16 (AWS001).

Figure 10 displays a visual representation of the positioning of the cameras in relation to the wolves, with red cameras indicating devices that successfully captured at least one wolf and grey cameras indicating devices that did not record any wolf activity. Notably, the wolf appeared to show a preference for one corner of the pasture, as opposed to approaching the pasture in a more dispersed manner. In addition, the event of a wolf being recorded on camera on the opposite side of the pasture occurred on a single day of the study period, namely 4 September 2023.

No sheep were attacked or killed by wolves in the study area during the monitoring period. Most wolf activity occurred between 6:00 and 10:00 (N = 13; 56.5%) and between 21:00 and 23:00 (N = 8; 34.8%). The wolf was observed only once during the night, around 4:00, and once in the afternoon, around 14:00 (N = 1; 4.35% for each). This also provides a rationale for the weather and light conditions previously described. The wolf was mostly detected under overcast skies and with a temperature between 12.8 °C and 18.6 °C. Regarding light conditions, most wolf detections occurred in darkness (N = 15; 65.2%), with the remainder in daylight (N = 8; 34.8%). Notably, no wolves were recorded during twilight.

A maximum of three wolves (N = 1; 4.35%) were recorded simultaneously as shown in

Figure 11 (4:00, 18 September 2023). Two wolves were observed together on three occasions (N = 5; 21.7%), all between 6:00 and 10:00. In most detections, only a single wolf was present (N = 17; 73.9%). Wolf interest in the fence or pasture was observed in 3 moments (N = 3; 13.0%). These observations were recorded by 2 different cameras (AWS002 and AWS001). The initial occurrence was observed on 6 September 2023 at approximately 21:20, which corresponded to one day after the sheep's arrival in the designated pasture. The image contained only one wolf. On 17 September 2023, at approximately 6:25, a mere 30 seconds elapsed between the second and third occurrences. This transpired 2 days subsequent to the sheep's departure in the afternoon of 15 September 2023. In these 2 cases, the presence of 2 wolves was observed: one located in proximity to the fence, demonstrating clear interest, and another positioned at a greater distance.

Looking around or at the ground occurred five times (N = 6; 26.1%), while the most common behaviour was walking or trotting past the camera (N = 17; 73.9%). The wolf approached the fence (i.e., within two metres) only in darkness (N = 8; 34.8%). For 3 of these moments (N = 3; 37.5%), sheep were present in the pasture. All 3 occurred on 6 September 2023 around 21:00, involved a single wolf, and included audible sheep bleating on the video recordings. More often, the wolf maintained a distance from the fence or walked on the opposite side of the sandy road (N = 20; 87.0%).

3.4.2. Sheep and Livestock Guardian Dogs

Of the 3,448 images captured, sheep appeared in 1,058 of them (N = 1,058; 30.7%). The images were captured between 7:30 and 21:00, primarily during daylight hours and occasionally during twilight.

Figure 12 displays the number of images containing sheep and livestock guardian dogs that were either visible or audible on each day of the study period. As shown, sheep were detected daily during their time in the pasture (from 5 September 2023 to 15 September 2023). Sheep activity peaked on 6 September 2023, with more than 500 detections, and was lowest on 8 September 2023.

Most images show sheep walking and grazing. Less frequently, they were observed lying down, observing their surroundings, sniffing, or ruminating. In none of the images did the sheep appear stressed or anxious.

The livestock guardian dogs appeared in 276 images (N = 276; 8.00%). The majority of the images were captured during daylight hours (N = 147; 63.3%), with a smaller number captured during twilight (N = 37; 13.5%) and darkness (N = 64; 23.3%). Similar to the sheep, the livestock guardian dogs’ presence peaked on 6 September 2023.

The livestock guardian dogs were frequently seen alone (N = 215; 77.9%). Two dogs appeared together in 49 images (N = 49; 17.8%) and 3 dogs in 10 images (N = 10; 3.62%). The presence of four dogs in the same image was rare.

The dogs most often appeared in a non-active guarding posture (N = 220; 79.7%). Active guarding behaviour was observed in 47 images (N = 47; 17.0%), while in 9 images (N = 9; 3.26%) the behaviour was unclear. In instances where at least one dog is present and actively guarding the flock, there is a notable absence of sheep detected in the images.

When not actively guarding, the dogs were mostly seen walking or trotting (N = 170; 77.3%). Less frequent behaviours included lying down, sitting, or rolling (N = 29; 13.2%), looking around (N = 9; 4.09%), sniffing (N = 9; 4.09%), and being near people (N = 5; 2.27%). Most of these activities took place during the day (N = 170; 77.3%).

In contrast, active guarding was predominantly observed during darkness (N = 42; 89.4%), with occasional observations during daylight (N = 4; 8.51%) and twilight (N = 1; 2.13%). Sheep were rarely present when dogs were actively guarding (N = 3; 6.38%). In 19 cases, actively guarding dogs were both visible and audible (N = 19; 40.4%) through barking. These barks generally sounded more aggressive or defensive (N = 17; 89.5%). Across all images, barking livestock guardian dogs (active or inactive) were observed in 83 images (N = 83; 2.41%), whereas a dog was visible in only 34 of these cases (N = 34; 41.0%). Barking was most frequently heard at night (N = 46; 55.4%).

The dogs were actively guarding on 6 September 2023, which was also a day that a wolf was detected by the cameras (

Figure 13). On the following day, 7 September 2023, one dog was still found to be guarding. Additionally, on 14 September 2023, dogs were found to be guarding. On 16 September 2023, a further sighting of wolves was recorded.

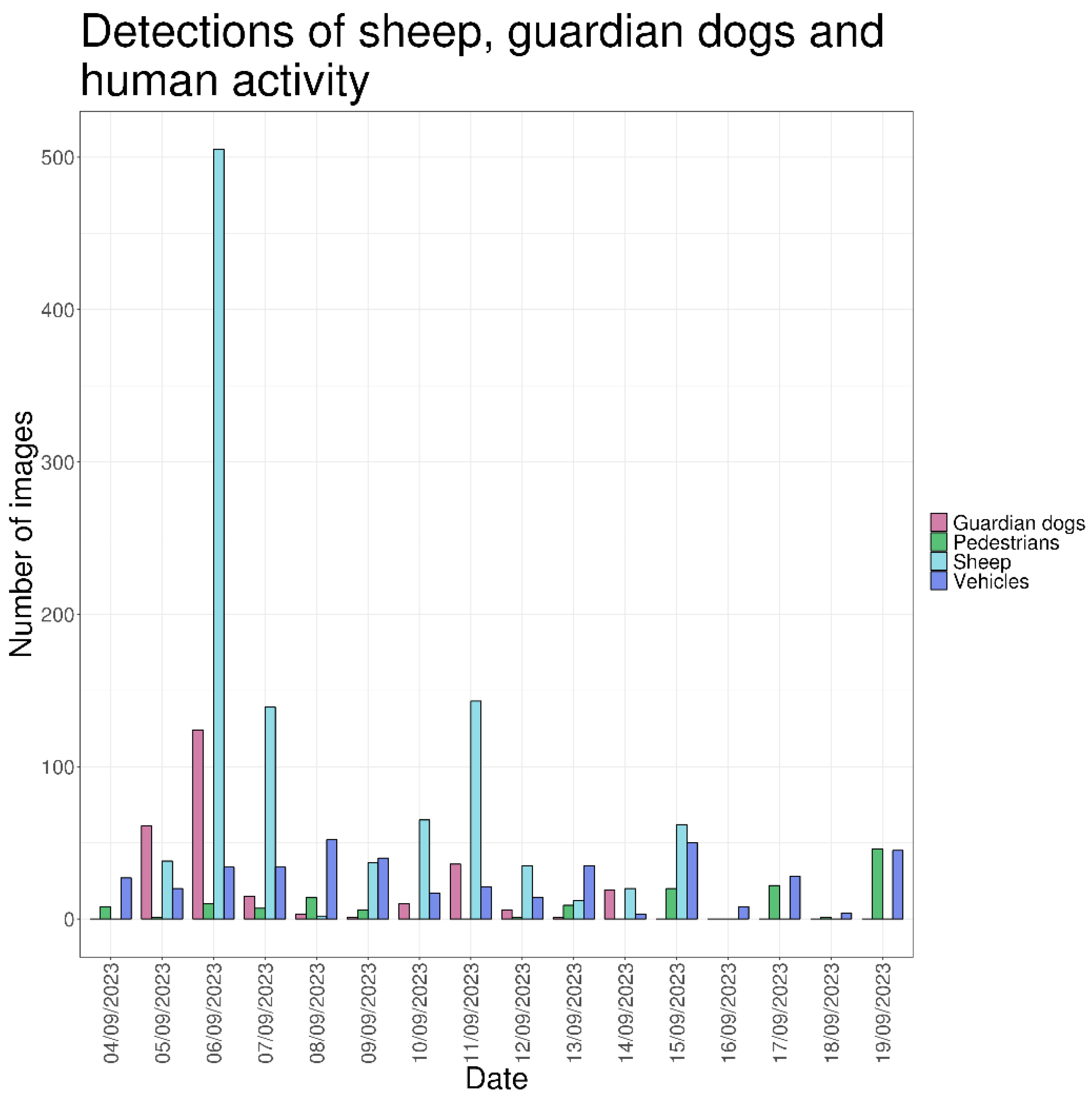

There appears to be no clear correlation between the presence of sheep and livestock guardian dogs on the one hand, and pedestrian activity on the other. This observation is equally applicable to the vehicle activity (

Figure 14).

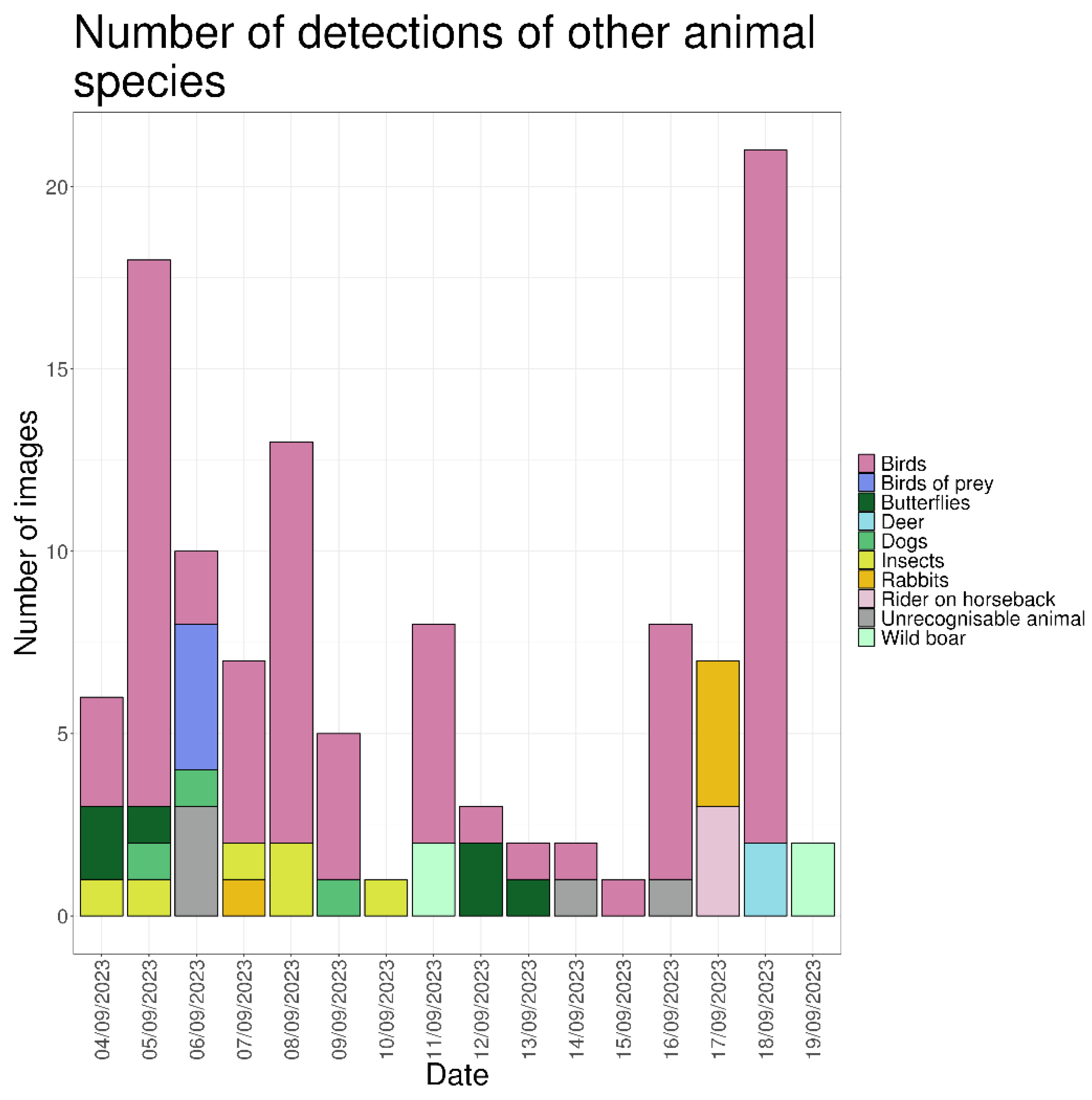

3.4.4. Other Wildlife Species

In addition to sheep and livestock guardian dogs, several other wildlife species were observed on the pasture during the study period (

Figure 15). The final number of images in the dataset containing other types of animals was 114. The most prevalent species identified were birds (N = 80; 70.2%), insects (N = 12; 5.26%), rabbits (N = 5; 4.39), wild boar (N = 4; 3.51%), and deer (N = 2; 1.75%).

Notably, on 18 September 2023, a deer was recorded jumping through the electric fence. Following the last measurement of the electric fence's power source on 15 September 2023, when the sheep were still present, it is possible that the electric current was low or absent at the time the deer crossed the fence. The detection of these other types of animals was predominantly during daylight (N = 94; 83.19%), with a less frequent detection during twilight (N = 4; 3.54%) and darkness (N = 15; 13.27%).

On average, approximately seven detections of other wildlife species are recorded on a daily basis. It is noteworthy that the periods from 4 September 2023 to 6 September 2023 and from 16 September 2023 to 18 September 2023 exhibited a remarkably higher average count of detections of these animals, with 11 and 12 detections, respectively. It is at these times that the presence of the wolf was also detected. The animals detected during these periods included birds (N = 46; 65.71%), birds of prey (N = 4; 5.71%), rabbits (N = 4; 5.71%), a rider on horseback (N = 3; 4.29%) and deer (N = 2; 2.86%). The detection frequencies of other species are shown in

Figure 16, in addition to the detection frequency of the wolves.

Figure 17 shows the distribution of additional wildlife species in relation to human interventions (pedestrians and vehicles).

3.5. Human Interventions

3.5.1. Vehicles

Figure 18 presents the number of images in which vehicles were detected. Out of the total 3,448 images, 432 images contained at least one vehicle (N = 432; 12.5%). The earliest recorded vehicle activity occurred at 08:32, and the latest at 20:16, indicating that most vehicle activity took place during daylight hours (N = 405; 93.8%), with a smaller portion occurring during twilight (N = 24; 5.56%).

The shepherd, either alone or accompanied, was frequently present in the study area, appearing in 235 images of vehicle detections (N = 235; 54.4%). Similarly, representatives of ANB (Agentschap voor Natuur & Bos) were visible in 132 images (N = 132; 30.6%).

Vehicles are a common and regular sight, appearing in almost every period and at various times of day.

Figure 19 presents the two periods in which wolves were recorded in terms of vehicle presence.

24The presence of sheep and livestock guardian dogs on the one hand, and vehicle activity on the other was already shown in

Figure 14.

3.5.2. Pedestrians

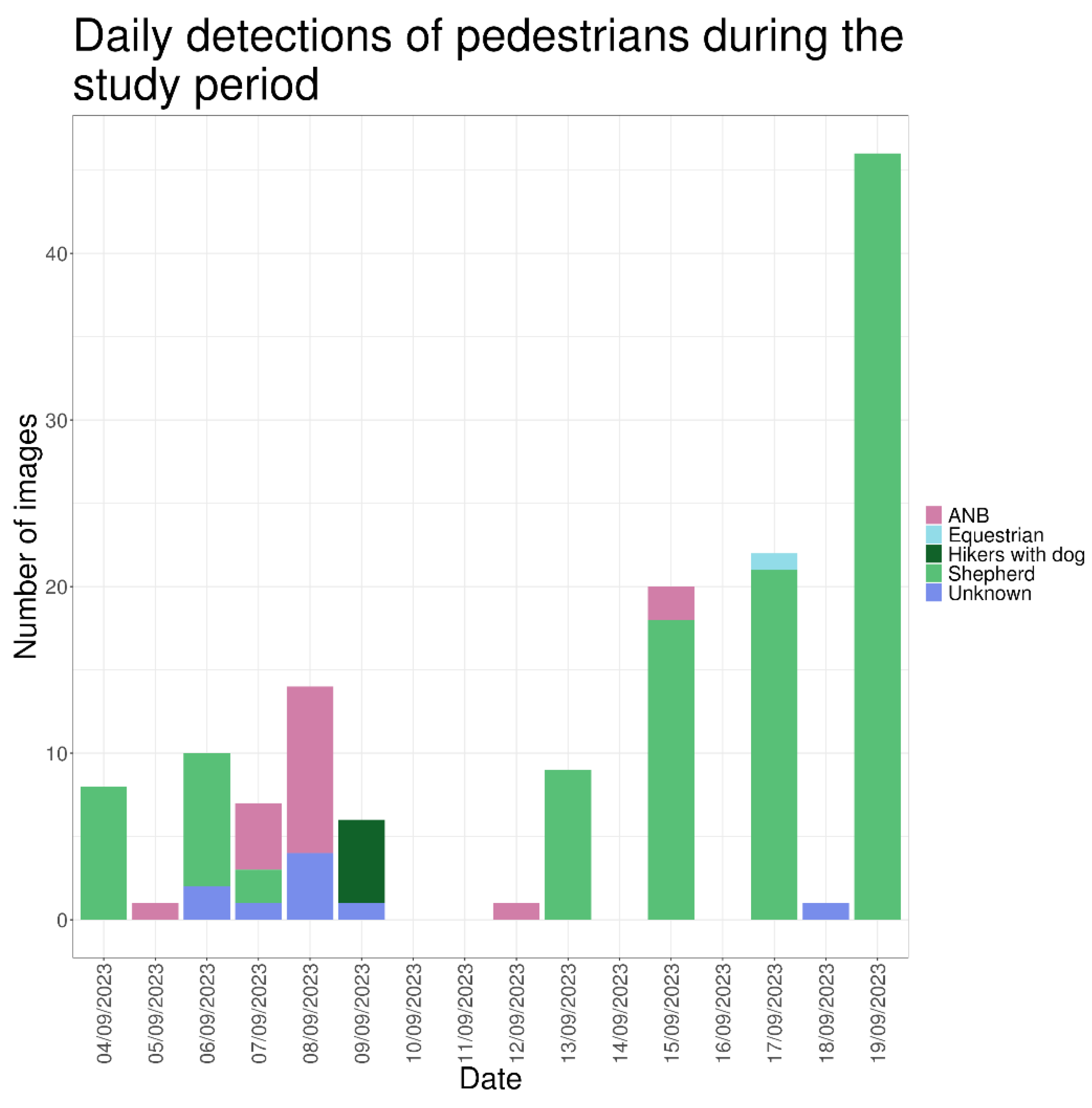

Figure 20 displays the number of images containing pedestrians. Of the total 3,448 images, 145 included at least one pedestrian (N = 145; 4.21%). The earliest pedestrian was recorded at 08:43, and the latest at 14:54, indicating that the vast majority of pedestrian activity occurred during daylight hours (N = 143; 98.6%).

Similar to the images containing vehicles, the shepherd—either alone or accompanied—was a frequent presence in the study area, appearing in 122 images (N = 122; 77.2%).

On two occasions, a wolf was captured on camera shortly before or after the presence of a vehicle and a pedestrian. The first event occurred on 17 September 2023, with wolves detected at 09:09 and 09:13. Later that morning, at 09:56, the shepherd’s vehicle was recorded, followed by a shepherd’s worker on foot. The cameras capturing the wolf and human activity were located on opposite sides of the study area. The second event took place on 18 September 2023, with wolves recorded at 09:34 and 09:32. Earlier that morning, at 09:06, an ANB vehicle was observed, and a pedestrian—who was an ANB worker—was seen photographing the ground at 09:07. These images were taken by alternating cameras. Notably, the wolf was present at the same location as the vehicle and pedestrian less than thirty minutes later.

Figure 21.

The number of wolves/pedestrians present in the images, for the two periods in which wolves were visible (04/09/2023-06/09/2023 and 16/09/2023-18/09/2023).

Figure 21.

The number of wolves/pedestrians present in the images, for the two periods in which wolves were visible (04/09/2023-06/09/2023 and 16/09/2023-18/09/2023).

3.6. Overview

Figure 22 summarizes the entire study period from 4 September 2023 to 19 September 2023. To improve clarity, the number of visual detections of the wolf has been plotted against a secondary y-axis. The wolf was observed during the first 3 days, with frequent detections of the livestock guardian dogs on 2 of these days, specifically 5 and 6 September 2023. No wolf detections were recorded during the subsequent 9 days.

On 15 September 2023, the frequency of sheep detections increased compared to previous days; this was also the final day the sheep remained on the pasture. Notably, wolf detections resumed on 16 September 2023.

Furthermore,

Figure 23 demonstrates a similar pattern in both auditory and visual detections of sheep and the visual detections of livestock guardian dogs, most prominently on 6 September 2023.

As illustrated in

Figure 23, there was a wolf present on 4 September 2023, following the presence of vehicles and pedestrians. A similar situation is observed on 5 September, coinciding with the arrival of sheep and livestock guardian dogs. There has been considerable movement in the pasture since 6 September, with both the dogs and the sheep displaying increased activity. At the end of the day, the wolf was detected.

Throughout the study period, images frequently depict sheep, while the presence of dogs is less frequently documented. Pedestrian and vehicle activity is very common. Following the departure of the livestock and the dogs, which resulted in increased movement in and around the pasture, the wolf was detected for 3 consecutive days.

4. Discussion

4.1. Wolves

In total, 23 images documented wolf activity. When considered chronologically, several detections captured by different cameras occurred within a six-minute interval, strongly suggesting repeated detections of the same wolf or pack rather than independent events. From this perspective, only eight distinct wolf detection events could be considered separate wolf detection events. Only one event, on 6 September 2023, involved wolves in direct proximity to sheep. The corresponding images show a wolf trotting alongside the fence. Most wolf detections involved a single wolf, although one image confirmed the presence of 3 wolves simultaneously. The underlying causes of this can vary. Firstly, it is important to note that a detection which contains solely one wolf may serve as an indication of the presence of a dispersing wolf [

26]. Secondly, the presence of a wolf, in addition to other wolves from the pack who were not detected, is a possibility. The patrolling behaviour exhibited by wolves does not invariably result in the formation of a compact group. Rather, they may adopt a more dispersed posture across the designated territory [

27].

At the time of the study, the exact composition of the local pack associated with GW1479f remained unknown. Nonetheless, the images verify that at least 3 wolves were present in the area.

Wolf detections closely coincided with livestock management interventions. The installation of the protective fence was completed on 2 September 2023, and the activation of the surveillance cameras followed on 4 September 2023. Interestingly, the first detection occurred on the same day, suggesting that wolves were already present in the vicinity. Wolves were subsequently observed from 4 to 6 September 2023, coinciding with the arrival of the sheep on 5 September 2023 and the presence of livestock guardian dogs.

Following the sheep’s departure and the addition of cameras on 15 September 2023, wolves reappeared over the following three days, from 16 to 18 September 2023. This second period of activity occurred immediately after sheep and dogs were removed. The final action, fence dismantling, occurred on 19 September 2023.

Similar temporal overlaps between wolf activity and livestock management interventions have been documented in other studies, indicating that wolves exhibit dynamic responses to variations in grazing areas. Previous studies demonstrate that livestock presence strongly influences wolf movements and space use, with increased activity in proximity to pastures when domestic prey is available [

28]. The implementation of deterrents, such as electric fences or livestock guardian dogs, tends to result in temporary reductions in wolf attacks [

29]. However, it has been observed that wolves often acclimatise to these measures or resume their activity in areas once interventions are withdrawn [

30]. This behavioural adaptation is illustrating the species’ ability to exploit opportunities while avoiding direct confrontation with humans. [

31].

Therefore, the observed synchrony between management actions and wolf detections in this study is likely to represent a combination of attraction to livestock presence and short-term avoidance or curiosity responses to newly implemented deterrents [

32]. This underscores the importance of protective infrastructure and livestock guardian dogs in shaping predator behaviour near livestock.

Wolves consistently approached the pasture from the same direction, suggesting the use of fixed routes. This pattern has been described previously, as wolves often repeat established movement routes [

33]. This can lead to practical implications, in the sense that extra preventive measures could be concentrated at such vulnerable access points. The presence of sheep and livestock guardian dogs throughout the pasture does not provide a satisfactory explanation for this phenomenon. Future research should examine whether wolves in Flanders typically adhere to fixed behavioural patterns in space, and whether landscape characteristics impede their mobility.

Despite the large variation in temperature during the study period (6.37-32.5 °C), wolves were only detected under moderate conditions (12.8–18.6 °C). Although this might suggest a preference for moderate temperatures, it is more likely a by-product of their activity patterns. Most detections occurred in the late evening or early morning, when ambient temperatures coincided with this range [

34]. Thus, the restricted temperature window likely reflects temporal activity rather than thermoregulatory preference. Still, this underscores the importance of considering temporal and environmental conditions when interpreting predator activity.

Three confirmed wolf attacks occurred in nearby locations during the study (8 September 2023 in Hechtel-Eksel, 11 September 2023 in Oudsbergen, and 13 September 2023 in Peer [

8]). Genetic analyses confirmed wolf involvement, though the precise individuals remain uncertain. Previous attacks in the same region were attributed to GW1479f and GW979m. Importantly, the attacked sheep were housed in unprotected pastures, in contrast to the protected study site. This supports the conclusion that livestock guardian dogs and wolf-proof fencing effectively deter predation attempts, potentially redirecting wolves to less protected sites.

Wolf presence tended to coincide with increased detections of other wildlife. On days with wolf detections, the mean number of images containing other animals (11.5) was notably higher than on days without wolf detections (7). This may indicate that wolves are attracted to areas of higher prey abundance, or that both wolves and other wildlife exhibit increased activity under similar environmental conditions, such as twilight hours when human disturbance is limited. Although the dataset is limited and prevents firm conclusions, these correlations are consistent with the findings of a Danish study [

35]. They emphasise the importance of integrating wider faunal monitoring into the assessment of predator movements.

4.2. Livestock and Livestock Guardian Dogs

On 6 September 2023, the sheep flock was detected on camera far more frequently than on any other day. Sheep were observed between 07:37 and 20:56, followed by a wolf detection later that evening at approximately 21:20. The presence of livestock guardian dogs was observed between 00:37 and 20:49, with active guarding behaviour documented from 01:07 to 09:52. The unusually high level of livestock activity may indicate that a wolf was nearby but beyond the cameras’ detection range. Sheep and livestock guardian dogs may have perceived the wolf before it was visually detected, thus resulting in heightened activity in the pasture. An increase in livestock activity in response to nearby predators was also observed by Evans et al. (2022), who used sensor-based monitoring to document how wild dogs (

Canis familiaris) influenced the movement and behaviour of rangeland sheep [

36]. An alternative hypothesis is that the increased detections of sheep and dogs were unrelated to the wolf's presence. In this particular instance, the subsequent approach of the wolf could be interpreted as an opportunistic investigation of the pasture, potentially initiated by the heightened activity it perceived [

37]. Alternatively, the increased activity may have resulted from the flock’s recent introduction to the pasture. The introduction of the sheep occurred on 5 September 2023 in the afternoon, and their increased movement on 6 September 2023 may be indicative of exploratory and adjustment behaviour in a novel environment, rather than a response to predator presence.

4.3. Human Interventions

The study area experienced frequent human activity, including pedestrians, vehicles, farmers, agricultural machinery, military vehicles, and horseback riders. Human activity occurred daily, predominantly during daylight hours. Despite this, wolf detections were not exclusively detected at night. On two occasions, wolves were recorded on camera in close temporal proximity to human presence, suggesting limited avoidance behaviour. The first incident occurred on the morning of 17 September 2023 between 09:00 and 10:00. The wolf was detected approximately 45 minutes before the shepherd’s vehicle and a worker were recorded on the opposite side of the study area. The second incident was documented on 18 September 2023 between 09:05 and 09:35, when an ANB vehicle and worker were observed, followed by wolf detection in the same location approximately 30 minutes later. These observations suggest that wolves in this landscape show limited avoidance of human activity. Barker et al. observed that in areas where prey populations are limited, wolves demonstrated a weaker response to humans than in areas where prey abundance was high. This finding suggests that wolves may prioritize hunting over avoiding human activity in areas with limited prey [

38].

Wolves appear to have established their territory in an area containing both a heavily used passageway and a shooting range. Similar patterns have been reported in other European regions. In Germany, for example, the first wolf packs recolonizing the country were frequently found within active military training areas [

39]. These areas often support high levels of biodiversity, providing abundant prey resources, while at the same time offering relatively low risks of mortality due to poaching or traffic accidents. Military landscapes may resemble the wolves’ original environments, combining extensive semi-natural areas with restricted public access and predictable patterns of human activity. Together, these findings indicate that wolves in Flanders can adapt to landscapes with substantial human presence.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that wolves in Flanders can persist in highly urbanized areas with intensive human activity, provided that effective livestock protection measures are implemented, illustrating the potential for adaptive coexistence between humans and large carnivores in highly modified environments. The combined use of livestock guardian dogs and electric fencing effectively prevented predation on sheep throughout the monitoring period, indicating that both measures are complementary and jointly essential for managing large flocks within wolf territories. Long-term coexistence in densely populated regions will therefore depend on the widespread adoption of reliable and cost-effective protective measures. Further research should disentangle the relative contributions of fencing and livestock guardian dogs to overall protection efficacy. Nevertheless, our findings underline that proactive livestock protection remains essential for reducing conflicts related to wolf presence. These results provide evidence-based support for ongoing management strategies such as the Flemish ‘Wolvenplan’ and highlight the importance of continuous monitoring and adaptive management to foster sustainable human–wolf coexistence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F. and B.D.; methodology, L.F. and B.D.; technical support, J.T.; video analysis, C.B.; data analysis: L.P.; draft writing, B.D., L.P., C.B. and L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, since it consisted solely of non-invasive camera-trap and field observations of wolves, sheep, and livestock guardian dogs under ordinary management practices. No experimental procedures or interventions with animals were performed, and the study complied with EU and national legislation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all parties involved in the study, including the shepherds, the Belgian military authorities, and the Agentschap Natuur en Bos, for conducting research and using the study area.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The satellite image used in Figure 10 was obtained from Google Earth Pro [40] and subsequently enhanced using OpenAI’s GPT-5 model to improve image clarity and contrast. No substantive alterations were made to the spatial information or content. A special thank you to Johan and Toon Schouteden, the shepherds, for making their flock and livestock guardian dogs available for this study. We also thank the soldiers of the Belgian military for granting us access to their shooting range. Our gratitude goes to ranger Michel Broekmans (Agentschap Natuur & Bos) for his assistance and guidance during the observation period.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Mergeay, J.; Van Den Berge, K.; Gouwy, J. De Vlaamse Jager. 2018, pp. 14–18.

- Imbert, C.; Caniglia, R.; Fabbri, E.; Milanesi, P.; Randi, E.; Serafini, M.; Torretta, E.; Meriggi, A. Why Do Wolves Eat Livestock? Biological Conservation 2016, 195, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population of Eastern Europe (2025) - Worldometer. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/eastern-europe-population/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Everaert, J.; Gorissen, D.; Van Den Berge, K.; Gouwy, J.; Mergeay, J.; Geeraerts, C.; Van Herzele, A.; Vanwanseele, M.-L.; D’hondt, B.; Driesen, K. Wolvenplan Vlaanderen; Rapporten van het Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek; Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek, 2018.

- Jarausch, A.; Harms, V.; Kluth, G.; Reinhardt, I.; Nowak, C. How the West Was Won: Genetic Reconstruction of Rapid Wolf Recolonization into Germany’s Anthropogenic Landscapes. Heredity 2021, 127, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevolkingsdichtheid | Statbel. Available online: https://statbel.fgov.be/nl/themas/bevolking/structuur-van-de-bevolking/bevolkingsdichtheid (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Van der Veken, T.; Van Den Berge, K.; Gouwy, J.; Berlengee, F.; Schamp, K. Voedselkeuze van de Wolf in Vlaanderen: Het Op Punt Zetten van de Methode En Een Eerste Verkenning; Rapporten van het Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek; Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek, 2021.

- De Wolf in Vlaanderen | Agentschap Voor Natuur En Bos. Available online: https://www.natuurenbos.be/dossiers/de-wolf-vlaanderen#overzicht-schadegevallen (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Krueger, K.; Gruentjens, T.; Hempel, E. Wolf Contact in Horses at Permanent Pasture in Germany. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0289767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Berge, K.; Casaer, J.; Gouwy, J. Advies over Grofwildbeheer Op Het Militair Domein van Houthalen-Helchteren; Adviezen van het Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek; Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek, 2019.

- Kovařík, P.; Kutal, M.; Machar, I. Sheep and Wolves: Is the Occurrence of Large Predators a Limiting Factor for Sheep Grazing in the Czech Carpathians? Journal for Nature Conservation 2014, 22, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf Fencing. Available online: https://www.wolffencing.be (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- De Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers - Schrifteli... - Strada Lex. Available online: https://www.stradalex.com/nl/sl_src_publ_div_be_chambre/document/SVbkv_55-b027-1163-0447-2019202004669 (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Vlaams Schaap | Steunpunt Levend Erfgoed. Available online: https://www.sle.be/wat-levend-erfgoed/rassen/vlaams-schaap (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- MASTÍN ESPAÑOL. Available online: https://www.fci.be/en/nomenclature/SPANISH-MASTIFF-91.html (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- De Wolf in Vlaanderen | Agentschap Voor Natuur En Bos. Available online: https://www.natuurenbos.be/dossiers/de-wolf-vlaanderen (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Basisinformatie Wolven | Wolven in Nederland. Available online: https://www.wolveninnederland.nl/de-wolf-terug-nederland/basisinformatie-wolven (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Gouwy, J.; Berge, K.V.D.; Berlengee, F.; Mergeay, J. Roofdiernieuws 25 - Wolvenspecial Oktober 2019.

- Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek Nieuwe Wolf “GW1479f” in Vlaanderen: Waarschijnlijk Noëlla. Available online: https://www.vlaanderen.be/inbo/persberichten/nieuwe-wolf-gw1479f-in-vlaanderen-waarschijnlijk-no%C3%ABlla/ (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Gouwy, J.; Mergeay, J.; Neyrinck, S.; Breusegem, A.V.; Berlengee, F.; Berge, K.V.D. Roofdiernieuws 31 2022.

- Gouwy, J.; Mergeay, J.; Neyrinck, S.; Breusegem, A.V.; Berlengee, F.; Berge, K.V.D.; Everaert, J. Roofdiernieuws 32 2023.

- Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek Autopsie Aangereden Wolf Bevestigt: Het Is GW979m (August). Available online: https://www.vlaanderen.be/inbo/persberichten/autopsie-aangereden-wolf-bevestigt-het-is-gw979m-august/ (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Packard, J.M. 2. Wolf Behavior: Reproductive, Social, and Intelligent. In Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation; Mech, L.D., Boitani, L., Eds.; University of Chicago Press, 2010; pp. 35–65 ISBN 978-0-226-51698-1.

- Mowat, F.M.; Peichl, L. Ophthalmology of Canidae: Foxes, Wolves, and Relatives. In Wild and Exotic Animal Ophthalmology: Volume 2: Mammals; Montiani-Ferreira, F., Moore, B.A., Ben-Shlomo, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 181–214. ISBN 978-3-030-81273-7. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mech, L.D. Unexplained Patterns of Grey Wolf Canis Lupus Natal Dispersal. Mammal Review 2020, 50, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, K.A.; Smith, D.W.; Mech, L.D.; MacNulty, D.R.; Stahler, D.R.; Metz, M.C. Territoriality and Inter-Pack Aggression in Gray Wolves: Shaping a Social Carnivore’s Life History. Yellowstone Science: celebrating 20 years of wolves 2016, 37–42.

- Mayer, M.; Olsen, K.; Schulz, B.; Matzen, J.; Nowak, C.; Thomsen, P.F.; Hansen, M.M.; Vedel-Smith, C.; Sunde, P. Occurrence and Livestock Depredation Patterns by Wolves in Highly Cultivated Landscapes. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, A.; Waltert, M.; Khorozyan, I. The Effectiveness of Livestock Protection Measures against Wolves (Canis Lupus) and Implications for Their Co-Existence with Humans. Global Ecology and Conservation 2020, 21, e00868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessel, T.V.; Snijders, L. Effectiveness of Behaviour-Based Interventions in Reducing Livestock Depredation by Wolves.

- Ferreiro-Arias, I.; García, E.J.; Palacios, V.; Sazatornil, V.; Rodríguez, A.; López-Bao, J.V.; Llaneza, L. Drivers of Wolf Activity in a Human-Dominated Landscape and Its Individual Variability Toward Anthropogenic Disturbance. Ecol Evol 2024, 14, e70397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanni, M.; Brivio, F.; Berzi, D.; Calderola, S.; Luccarini, S.; Costanzi, L.; Dartora, F.; Apollonio, M. A Report of Short-Term Aversive Conditioning on a Wolf Documented through Telemetry. Eur J Wildl Res 2023, 69, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurarie, E.; Bracis, C.; Brilliantova, A.; Kojola, I.; Suutarinen, J.; Ovaskainen, O.; Potluri, S.; Fagan, W.F. Spatial Memory Drives Foraging Strategies of Wolves, but in Highly Individual Ways. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicedo, T.; Meloro, C.; Penteriani, V.; García, J.; Lamillar, M.Á.; Marsella, E.; Gómez, P.; Cruz, A.; Cano, B.; Varas, M.J.; et al. Temporal Activity Patterns of Bears, Wolves and Humans in the Cantabrian Mountains, Northern Spain. Eur J Wildl Res 2023, 69, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunde, P.; Kjeldgaard, S.A.; Mortensen, R.M.; Olsen, K. Human Avoidance, Selection for Darkness and Prey Activity Explain Wolf Diel Activity in a Highly Cultivated Landscape. Wildlife Biology 2024, 2024, e01251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.A.; Trotter, M.G.; Manning, J.K. Sensor-Based Detection of Predator Influence on Livestock: A Case Study Exploring the Impacts of Wild Dogs (Canis Familiaris) on Rangeland Sheep. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeiro-Otero, A.; Newsome, T.M.; Van Eeden, L.M.; Ripple, W.J.; Dormann, C.F. Grey Wolf (Canis Lupus) Predation on Livestock in Relation to Prey Availability. Biological Conservation 2020, 243, 108433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, K.J.; Cole, E.; Courtemanch, A.; Dewey, S.; Gustine, D.; Mills, K.; Stephenson, J.; Wise, B.; Middleton, A.D. Large Carnivores Avoid Humans While Prioritizing Prey Acquisition in Anthropogenic Areas. Journal of Animal Ecology 2023, 92, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, I.; Kluth, G.; Nowak, C.; Szentiks, C.A.; Krone, O.; Ansorge, H.; Mueller, T. Military Training Areas Facilitate the Recolonization of Wolves in Germany. Conservation Letters 2019, 12, e12635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Earth Pro, Version 7.3.6.10441; Imagery © 2021 Maxar Technologies.

Figure 1.

Satellite image of shooting range.

Figure 1.

Satellite image of shooting range.

Figure 2.

Vegetation map of the area. The grazing pasture is delineated by white lines.

Figure 2.

Vegetation map of the area. The grazing pasture is delineated by white lines.

Figure 3.

Satellite image of pasture with sides labelled (A-F). Cameras are placed alongside E, D and F. (A: 875m; B: 921m; C: 1000m; D: 625m; E: 140m; F: 240m).

Figure 3.

Satellite image of pasture with sides labelled (A-F). Cameras are placed alongside E, D and F. (A: 875m; B: 921m; C: 1000m; D: 625m; E: 140m; F: 240m).

Figure 4.

Name and orientation cameras. Yellow: Denver, light blue: Suntek and darker blue: Numaxes.

Figure 4.

Name and orientation cameras. Yellow: Denver, light blue: Suntek and darker blue: Numaxes.

Figure 5.

Timeline of the monitoring procedure.

Figure 5.

Timeline of the monitoring procedure.

Figure 6.

Number of images captured by each camera, sorted from the most active to the least active device.

Figure 6.

Number of images captured by each camera, sorted from the most active to the least active device.

Figure 7.

Number of videos containing audio grouped by the audio type (beeping sound, livestock guardian dogs, sheep, ticking sound or other sounds).

Figure 7.

Number of videos containing audio grouped by the audio type (beeping sound, livestock guardian dogs, sheep, ticking sound or other sounds).

Figure 8.

Number of images made during the study period grouped by the light condition.

Figure 8.

Number of images made during the study period grouped by the light condition.

Figure 9.

Number of images made by the cameras that captured at least one wolf during the study period.

Figure 9.

Number of images made by the cameras that captured at least one wolf during the study period.

Figure 10.

Satellite image of the study area showing the location of the pasture and the positioning of camera traps. Red triangles indicate cameras that captured at least one instance of wolf activity; grey triangles indicate cameras with no wolf activity. Image enhanced using OpenAI GPT-5 (2025) to improve visual clarity.

Figure 10.

Satellite image of the study area showing the location of the pasture and the positioning of camera traps. Red triangles indicate cameras that captured at least one instance of wolf activity; grey triangles indicate cameras with no wolf activity. Image enhanced using OpenAI GPT-5 (2025) to improve visual clarity.

Figure 11.

The number of wolves detected during the study period.

Figure 11.

The number of wolves detected during the study period.

Figure 12.

The number of images in which sheep and livestock guardian dogs are visible an audible, for every day in the study period.

Figure 12.

The number of images in which sheep and livestock guardian dogs are visible an audible, for every day in the study period.

Figure 13.

Daily detections of wolves and actively guarding dogs by the cameras, for every day in the monitoring period.

Figure 13.

Daily detections of wolves and actively guarding dogs by the cameras, for every day in the monitoring period.

Figure 14.

The number of images in which sheep, livestock guardian dogs, pedestrians and vehicles are detected, for every day in the study period.

Figure 14.

The number of images in which sheep, livestock guardian dogs, pedestrians and vehicles are detected, for every day in the study period.

Figure 15.

The number of images in which other types of animals are visible, for every day in the study period.

Figure 15.

The number of images in which other types of animals are visible, for every day in the study period.

Figure 16.

The number of images in which wolves and other animal species are visible, for every day in the study period.

Figure 16.

The number of images in which wolves and other animal species are visible, for every day in the study period.

Figure 17.

The number of images in which other wildlife species and human interventions (pedestrians and vehicles) are visible, for every day in the study period.

Figure 17.

The number of images in which other wildlife species and human interventions (pedestrians and vehicles) are visible, for every day in the study period.

Figure 18.

Daily detections of vehicles during the monitoring period.

Figure 18.

Daily detections of vehicles during the monitoring period.

Figure 19.

The number of wolves and vehicles present in the images, for the two periods in which wolves were visible (04/09/2023-06/09/2023 and 16/09/2023-18/09/2023).

Figure 19.

The number of wolves and vehicles present in the images, for the two periods in which wolves were visible (04/09/2023-06/09/2023 and 16/09/2023-18/09/2023).

Figure 20.

The number of images in which pedestrians are visible, for every day in the study period.

Figure 20.

The number of images in which pedestrians are visible, for every day in the study period.

Figure 22.

Overview of the number of images containing sheep, livestock guardian dogs, wolves, other wildlife species, pedestrians and vehicles.

Figure 22.

Overview of the number of images containing sheep, livestock guardian dogs, wolves, other wildlife species, pedestrians and vehicles.

Figure 23.

Overview of the number of sheep, livestock guardian dogs, wolves, pedestrians and vehicles captured by the cameras on a continuous timescale.

Figure 23.

Overview of the number of sheep, livestock guardian dogs, wolves, pedestrians and vehicles captured by the cameras on a continuous timescale.

Table 1.

Camera types, names and characteristics.

Table 1.

Camera types, names and characteristics.

| Camera |

Name |

Type |

Distance IR |

Angle lens |

Angle PIR |

Resolution |

Type IR |

Numaxes

(AWS 005, AWS 003, AWS 004, AWS 002 and AWS 001) |

Trail camera - model PIE1051 - 4G |

4G |

20m |

100° |

100° |

24MP |

940nm |

Denver

(AWS 014, AWS 010, AWS 006, AWS 007, AWS 009, AWS 011, AWS 008 and AWS 012) |

Denver WCT-8020W |

Wi-Fi |

25m |

90° |

120° |

12MP |

940nm |

Suntek

(AWS 020, AWS 019, AWS 017, AWS 018, AWS 016 and AWS 015) |

Suntek HC-940Pro-Li 4K 36 MP 4G APP Wildlife Trail Camera met live streaming |

4G |

30m |

90° |

120° |

36MP |

940nm |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).