1. Introduction

The CCR5 receptor, a G protein-coupled integral membrane receptor, functions as a chemokine receptor on the surface of T cells, macrophages, eosinophils, dendritic cells and some carcinoma cells, including breast and prostate [

1,

2]. Ligands for CCR5 include CCL3, CCL4, CCL3L1, and CCL5 [

3,

4,

5,

6]. CCR5 serves as a co-receptor for the cellular entry point for HIV. Leronlimab, a humanized monoclonal anti-CCR5 antibody, was developed as an entry inhibitor for HIV. In a

phase 2b/3 study HIV-1 RNA levels were reduced to <50 copies per mL plasma, suggesting utility of leronlimab as a component of salvage therapy [

7]

. Leronlimab was generally well tolerated with no drug-related SAEs reported [

7]

. Leronlimab functions as a competitive inhibitor of CCR5 by binding to the second external loop of CCR5 [

8]. Binding of leronlimab to CCR5 does not induce agonistic activity (activation of tyrosine kinase or synthesis of cAMP). Leronlimab, in combination with standard anti-retroviral therapies, has successfully completed a Phase 3 pivotal trial in HIV-infected treatment-experienced patients.

CCR5 is overexpressed in cancers [

9], increasing in abundance upon cellular oncogenic transformation [

10]. The use of small molecule CCR5 inhibitors validated the importance of CCR5 in the progression and metastasis of breast [

1] and prostate cancer [

2] , reducing bone and brain metastasis in immune competent mice. CCR5 facilitates the onset and progression of breast cancer [

11] and leronlimab prevented the breast cancer metastasis and reduced the size of established metastasis [

12]. Expression of

CCR5 is elevated in colon cancer, correlating with poor outcomes and advanced TNM stage [

13,

14]

. Microsatellite instability (MSI) in colon cancers occurs due to defects in mismatch repair (MMR). MSI is less common (15%) and associated with a better prognosis and potential response to certain immunotherapies. High CCR5 and CCL5 expression is associated with increased tumor mutational burden, deficiency in mismatch repair, and elevated PD-L1 levels, suggesting a link to immunotherapy resistance [

13]

.

Our previous studies indicated that treatment with leronlimab abrogated xenogenic graft-versus-host-disease (xGVHD) in NSG mice [

15]. Leronlimab blunted the development of xGVHD, but did not block engraftment of normal human leukocytes in the murine bone marrow. Other evidence suggested that a small molecule inhibitor of CCR5 (maraviroc) was clinically effective at blocking immunosuppressive cellular activity, mediated by CCL5 expressed on cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), and that CCR5 blockade was associated with re-polarization of tumor associated macrophages from M2 phenotype (immunosuppressive) back to M1 (pro-inflammatory) in the colon carcinoma microenvironment [

16]. Blockade of CCR5 by maraviroc rescued mice from inflammatory bowel disease (colitis) in both acute and chronic models [

17]. The CCL5-CCR5 axis clearly plays a role in orchestrating several key aspects of the immune response [

18]. The goal of these studies was to determine if leronlimab treatment might induce a graft-versus-tumor effect against primary or metastatic colon carcinoma lesions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Studies

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards and according to national and international guidelines and were approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ, commonly known as the NOD scid IL-2 receptor gamma knockout (NSG, Jackson Laboratory, Stock No. 005557), were 6-8 weeks old when used. Mice were housed in a specific pathogen free barrier facility in cages with microisolator lids, autoclaved bedding, HEPA-filtered air, and maintained under 12:12 light:dark cycles, controlled temperature and humidity. Animals had free access to autoclaved standard food and filtered water. Conditioning regimen: mice received 225 cGy total body irradiation via an X-ray source (Precision X-Rad 320, North Branford, CT).

2.2. Humanized Mouse Model and Tumor Inoculation

Twenty-four hours after X-ray irradiation, mice were engrafted with human BM cells. De-identified human donor cells were obtained by back-flushing filter packs utilized by the Cleveland Clinic Bone Marrow Transplant program. Fresh (non-frozen) leukocytes were purified by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation, washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and assessed for viability (ViCell, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Human BM mononuclear leukocytes were injected into the lateral tail vein (10

6 cells/mouse).

Heterotopic inoculation: On day 35, when there was clear evidence of human leukocyte engraftment, mice were inoculated in the flanks with 2.5x10

5 SW480 human colon carcinoma cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) that had been stably transfected with luciferase-pcDNA3 [

32] using Lipofectamine. The luciferase-pcDNA3 plasmid was a gift from William Kaelin (Addgene plasmid # 18964;

http://n2t.net/addgene:18964; RRID: Addgene_18964). Mice were monitored for clinical symptoms of GvHD (body posture, activity, fur and skin condition, weight loss) two times/week. Peripheral blood was monitored weekly for engraftment utilizing saphenous vein venipuncture (50 µL) collected in K-EDTA tubes. At day 81 over half the mice exhibited > 10% weight loss, clinical symptoms of GvHD, and were considered to have reached experimental endpoint.

Orthotopic inoculation: Under ketamine-xylazine anaesthesia, following skin preparation with Betadine scrub and 70% ethanol wipe (x3), the cecum was exposed through a 10 mm incision. 10

5 SW480-luc cells in a volume of 10 uL were inoculated into the sub-serosa of the cecum using a 31-gauge needle. Cecum was returned to the peritoneal cavity, muscle and skin were closed in two layers of suture, and mice were allowed to recover.

Euthanasia: Mice were subject to euthanasia by controlled gradient CO

2 inhalation (Quietek, NextAdvance, Averill Park, NY) followed by cervical dislocation, and tumors and organs were harvested.

Bioluminescent imaging: To evaluate metastases mice were analyzed using the IVIS Spectrum

In Vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer, Waltham MA). Luciferin doses were 3 mg i.p. for

in vivo imaging, and 150 ug/mL for

in vitro imaging of excised lungs and liver.

2.3. Leronlimab Treatment

Mice were randomized into control and treatment groups of 8 animals each by body weight. Leronlimab was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at 2.0 mg/mouse twice weekly. The 2.0 mg dose was calculated [

33,

34] to approximate the dose used in an ongoing CytoDyn sponsored phase 2 human clinical trial for acute GvHD. A single administration of this dose in HIV positive patients has been shown to reduce the HIV load by more than ten-fold. Control mice received normal human IgG (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at the same dose level.

2.4. Flow Cytometry

Peripheral blood (PB) samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. Erythrocytes were lysed with ammonium chloride, cells were washed twice with PBS and stained for 15 min at 4 deg C in PBS/0.5 mM EDTA/0.5% BSA with the following antibodies: anti-human-CD3-FITC (clone UCHT1, IM1281U), anti-human-CD45-PC7 (clone J.33, IM3548U), anti-mouse-CD45.1-FITC (clone A20), eBioscience (Thermo Fisher) and anti-human-CD56-PE (clone 5.1H11), BioLegend. For human CD45, mouse CD45, and human CD3, results were expressed as percentage of total events. For human CD56, results were expressed as percentage of total events. For analysis of immunosuppressive cells, True-Nuclear Human Treg Flow Kit (FoxP3 AlexaFluor 488/CD4 PE-Cy5/CD25 PE) was used according to manufacturer directions (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Samples were analyzed on a Cytomics FC500 Flow Analyzer (Beckman/Coulter).

2.5. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry staining was performed using the Discovery ULTRA automated stainer from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). Antigen retrieval was performed using a tris/borate/EDTA buffer (Discovery CC1, 06414575001; Roche), pH 8.0 to 8.5. Time, temperature, and dilutions are listed below. The antibodies were visualized using the OmniMap anti-Rabbit HRP (05269679001; Roche), and OmniMap anti-Mouse HRP (05269652001; Roche) in conjunction with the ChromoMap DAB detection kit (05266645001; Roche). Lastly, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and bluing.

2.6. Cell Sorting

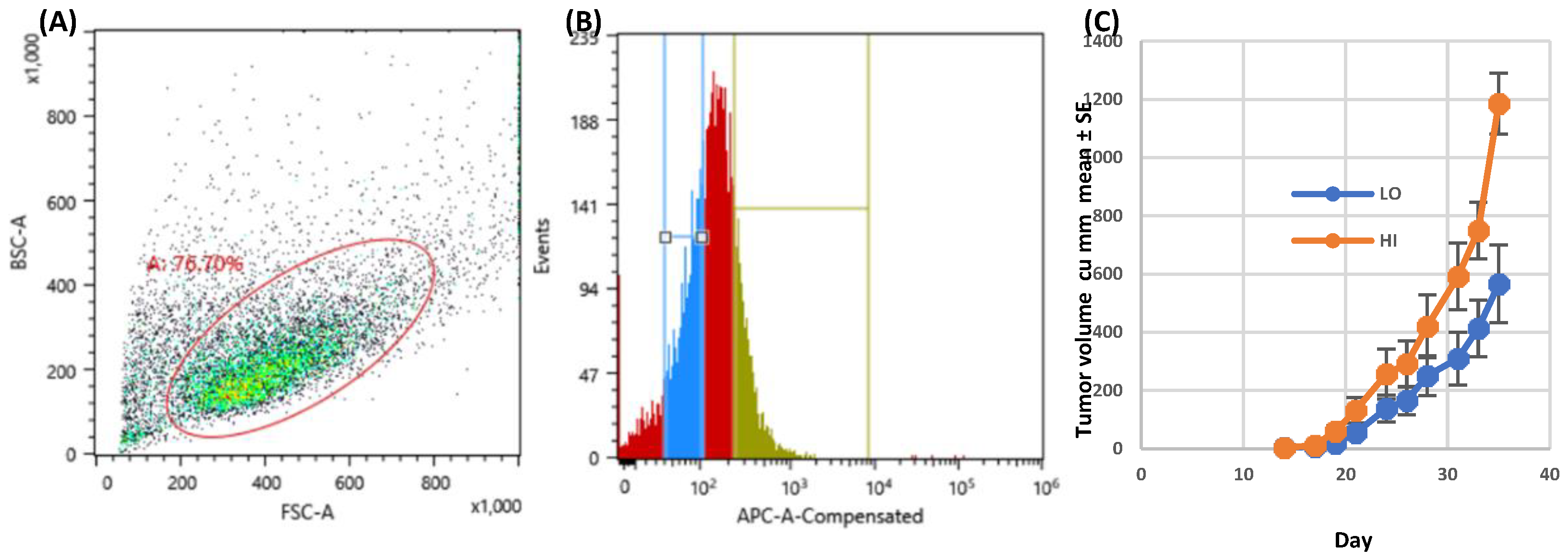

SW480 cells were grown as a monolayer in DMEM with 10% FBS, Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Sigma), in a 37 deg C incubator, at 5% CO2 and converted into a single cell suspension using Cell Dissociation Solution Non-enzymatic 1X (Sigma). Cells were stained with CCR5-APC, Anti-human/mouse/rabbitCCR5, APC conjugate, IgG1, CAT#FAB1802A (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at a 1:20 dilution in 1xPBS with 2% FBS. Cells were sorted by FACS into CCR5-High and CCR5-Low populations. Cell sorting was performed on a Sony SH800Z using a 130uM nozzle. Sorting of CCR5 dim and bright positive cells was based on sequential gating of FSC vs. SSC to exclude debris; 76.70% of cells were included in the gate.

2.7. Tumor Angiogenesis

Blood vessels growing at the periphery of dermally inoculated day 10 SW480 colon carcinoma tumors in humanized NSG mice were photographed using a dissecting microscope at 12.5x magnification. Every visible vessel touching the circumference of the tumor nodule was scored as a single vessel. Two measurements were taken to assess the tumor area (the largest diameter coplanar with the skin, and a second diameter perpendicular to the first). The product of these two measurements was used as an index of tumor area. Grayscale mages were captured using an operating microscope with 12.5 objective lens (World Precision Instruments, PSMT5, Sarasota, FL). Each experimental group contained eight mice. Grayscale images were converted to binary images (black and white) using Photoshop (Adobe). Binary images were subjected to digital analysis using VESGEN software [

35], where the region of interest representing the tumor mass defined the perimeter of the tumor. The output was a series of color Vessel Generation maps (colored vessels on black background) in which the vessels of largest diameter were defined as G1 (

red), with each subsequent smaller generation represented as G2–G9. From these maps, the software calculated the total vessel area, vessel length density, vessel number, and vessel diameter.

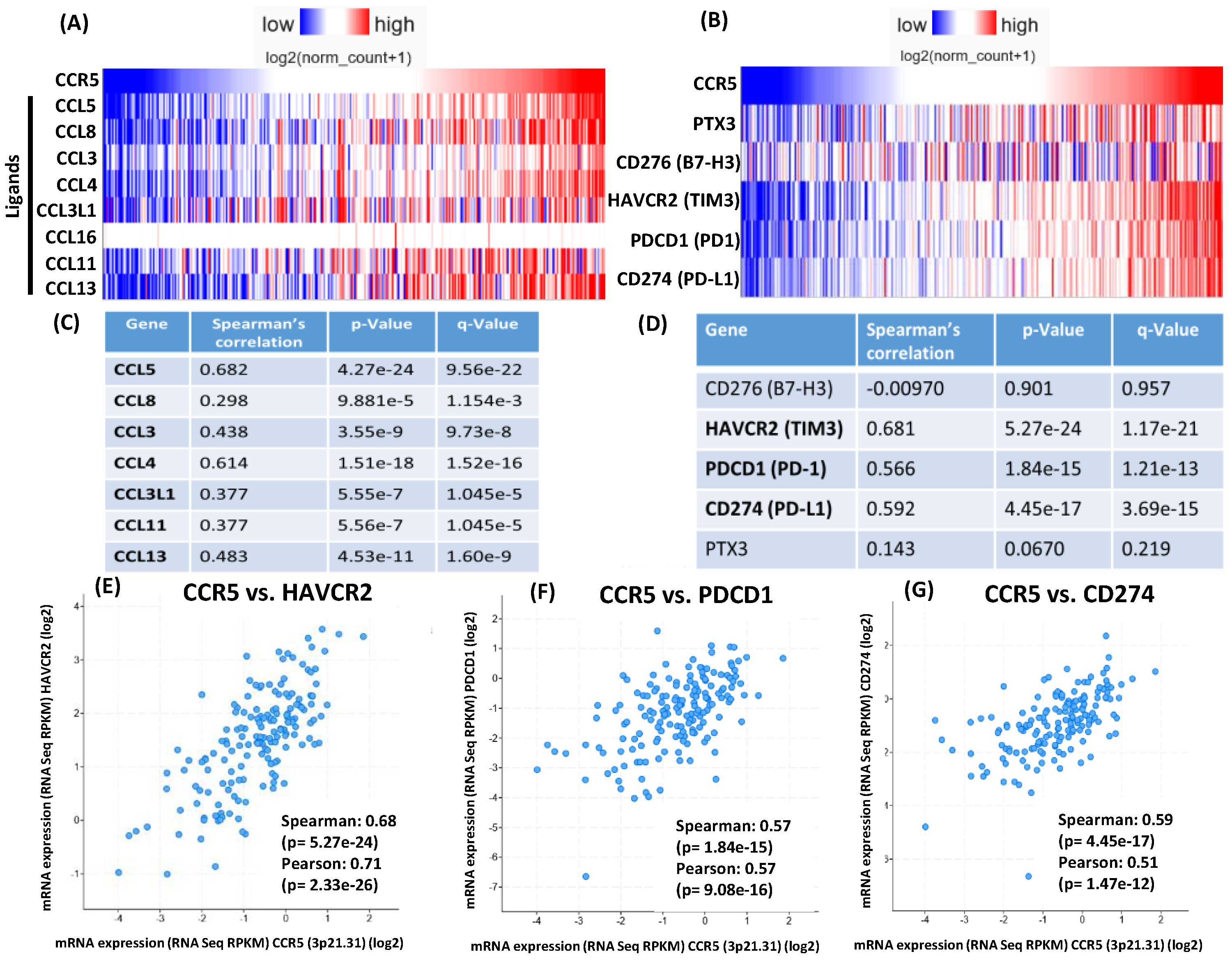

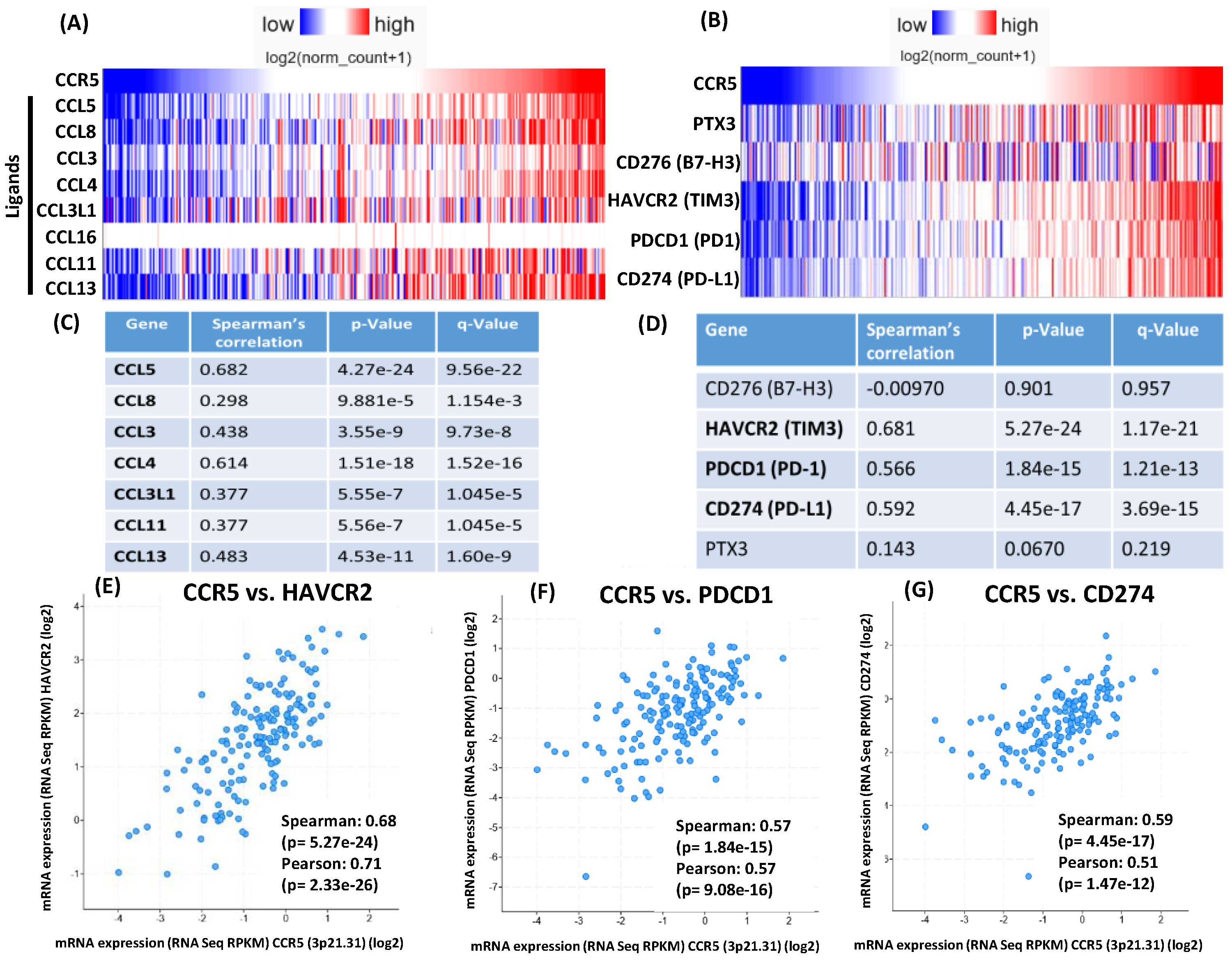

2.8. CCR5 Gene Expression Correlation Analysis on TCGA COAD Samples

Gene expression correlation analysis was conducted using the UCSC Xena platform [

23] on TCGA Colon and Rectal Cancer (COADREAD) samples (dataset TCGA, [

36])

. For the 434 samples with available RNAseq data, the expression of CCR5 ligands were assessed for correlation with CCR5 expression using the built in Spearman’s and Pearson’s correlation functions. The expression of immune checkpoint genes was similarly assessed. The platform allowed for grouped visualizations of the expression correlations (Figure 7A,B), but analysis of MSS and MSI samples separately was not possible, because the platform did not store such annotations for the samples. Therefore, the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics platform [

24] was used for analysis of gene expression correlations for MSS (Figure 7C-G) and MSI samples (

Figure S2A-E), separately. Correlations between the expression of CCR5 and the expressions of CCR5 ligands as well as of immune checkpoints was analysed using the built-in expression correlation tool of the platform applying default parameters (Spearman’s correlation with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction). Pairwise correlations with the significantly correlated immune checkpoint genes were depicted using a log scale (Figure 7E-G for MSS and

Figure S2C-E for MSI samples).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All measures of variance were depicted as standard error of the mean (SEM). Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and Mantel-Cox log-rank test. For other data, two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test was used.

4. Discussion

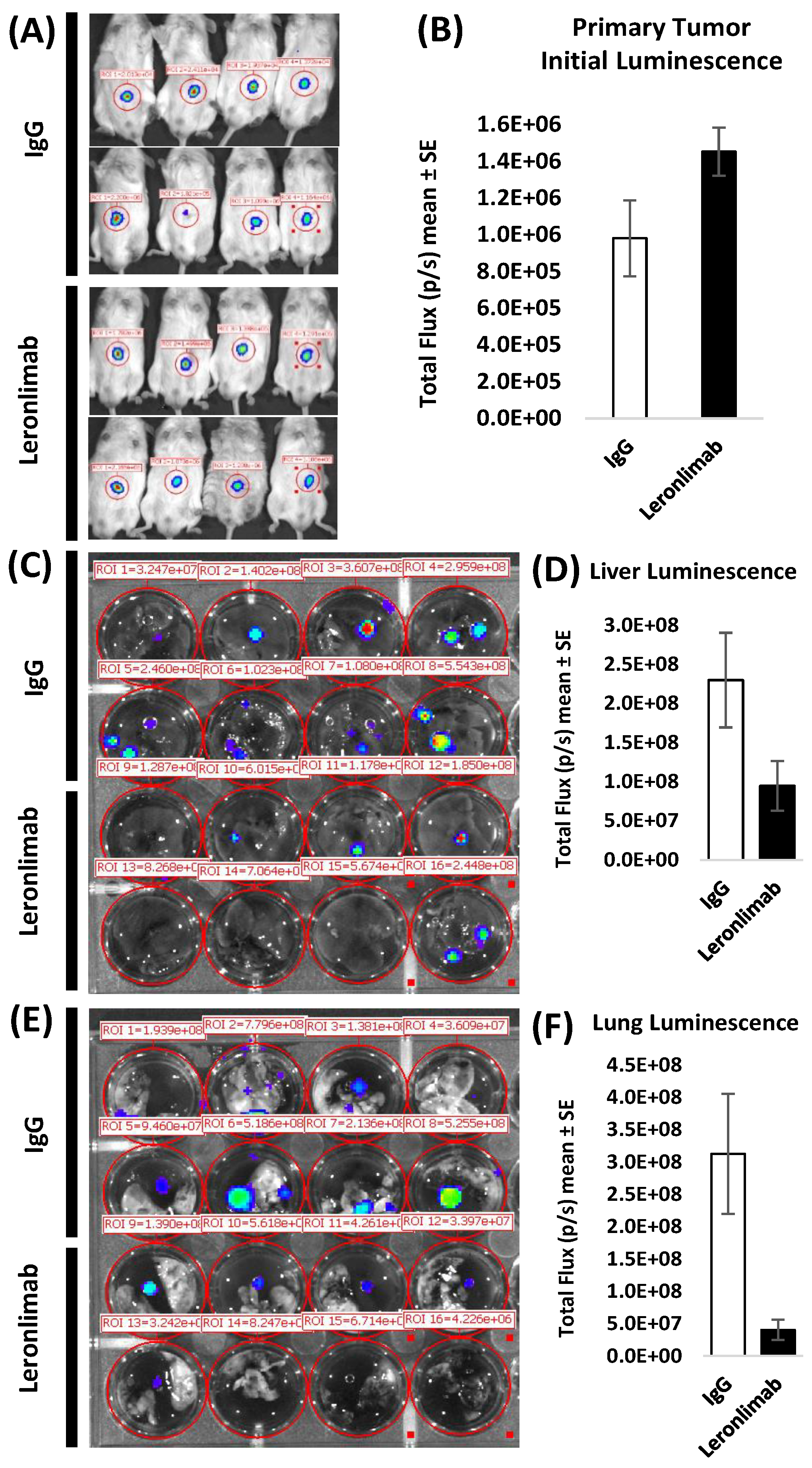

In the current studies, tumor cells overexpressing CCR5 did not exhibit accelerated growth

in vitro assessed by sulforhodamine B staining (measures total cell mass) or MTT assay (3-[4,5-di-methylthiazol-2yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide; measures metabolic activity). To more accurately model the physiology and progression of human colon carcinoma, an orthotopic model was employed, utilizing sub-serosal inoculation of luc-SW480 tumor cells in the cecum. In the absence of leronlimab treatment, SW480 colon carcinoma cells with high CCR5 expression displayed a tumor growth advantage

in vivo (

Figure 1). Leronlimab treated mice displayed a 59% (p=0.067) and 89% (p=0.012) decrease in number of metastatic cells in liver and lung, respectively. The reduction in lung metastases was highly significant, whereas the reduction in liver metastases approached statistical significance. Hence the degree of tumor inhibition was more pronounced in the metastatic lesions compared to growth inhibition of the primary subcutaneous. tumors. Our studies are consistent with evidence that CCR5 governs cancer metastasis as either small molecular inhibitors of CCR5 [

1], or leronlimab [

12] reduced breast carcinoma cell metastasis (reviewed in [

11]). Together, our findings suggest that cytokines or direct cellular contact with host tissues may be required for CCR5-mediated enhancement of tumor growth.

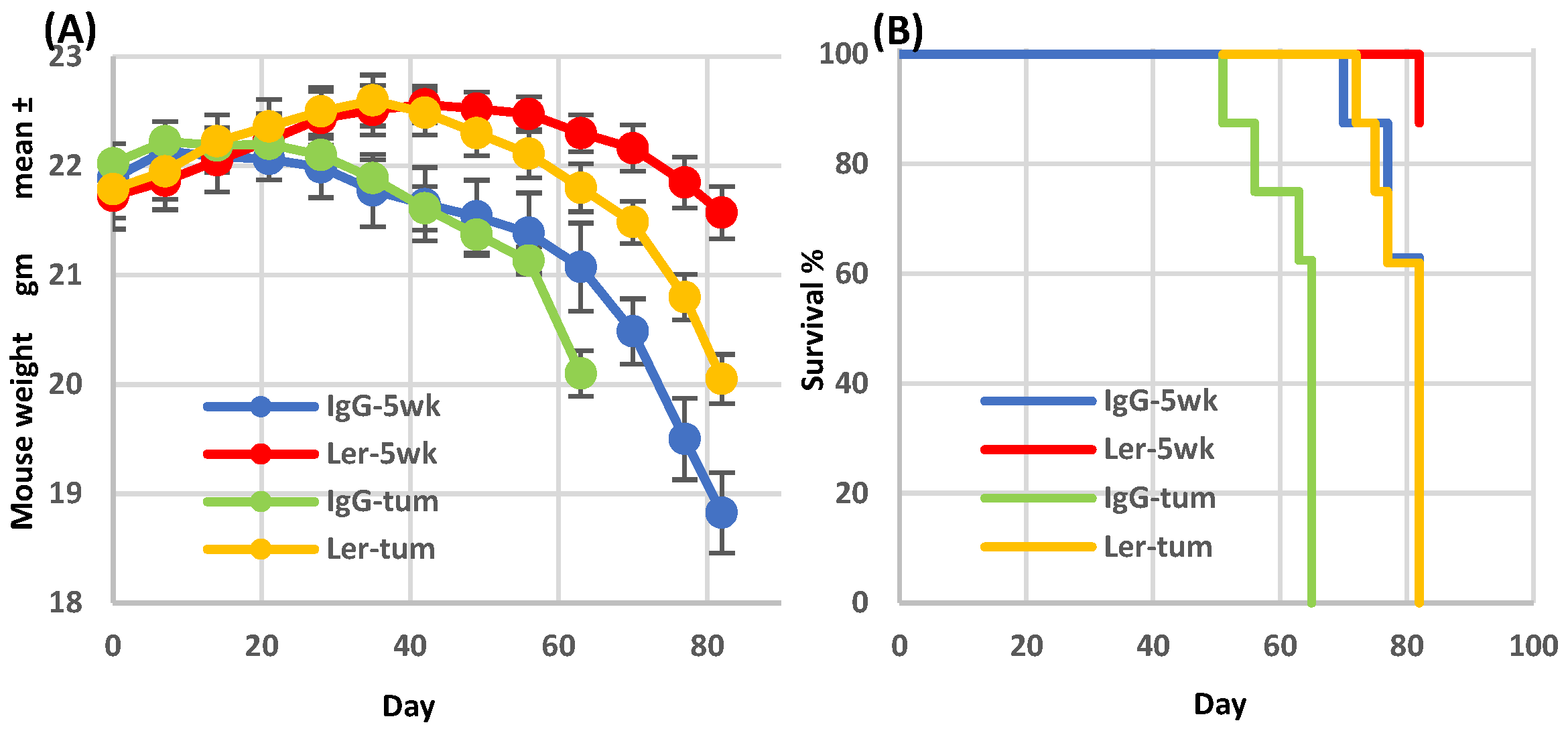

Graft-versus-host (GVH) and graft-versus-tumor (GVT) activities diverge following leronlimab treatment, in a therapeutically advantageous direction. As in our previous studies [

15], leronlimab inhibited the development of GVHD symptoms in mice that had been humanized with normal donor bone marrow cells (

Figure 2A, blue & red curves). As expected, cohorts of tumor-bearing humanized mice (

Figure 2A, green & yellow curves) had a more rapid weight loss compared to non-tumor bearing mice. In both cases, leronlimab treatment prolonged survival (

Figure 2B). After cessation of treatment on day 35, weight loss accelerated, requiring animal euthanasia. Thus the anti-GVHD effect was lost as leronlimab was cleared from the circulation.

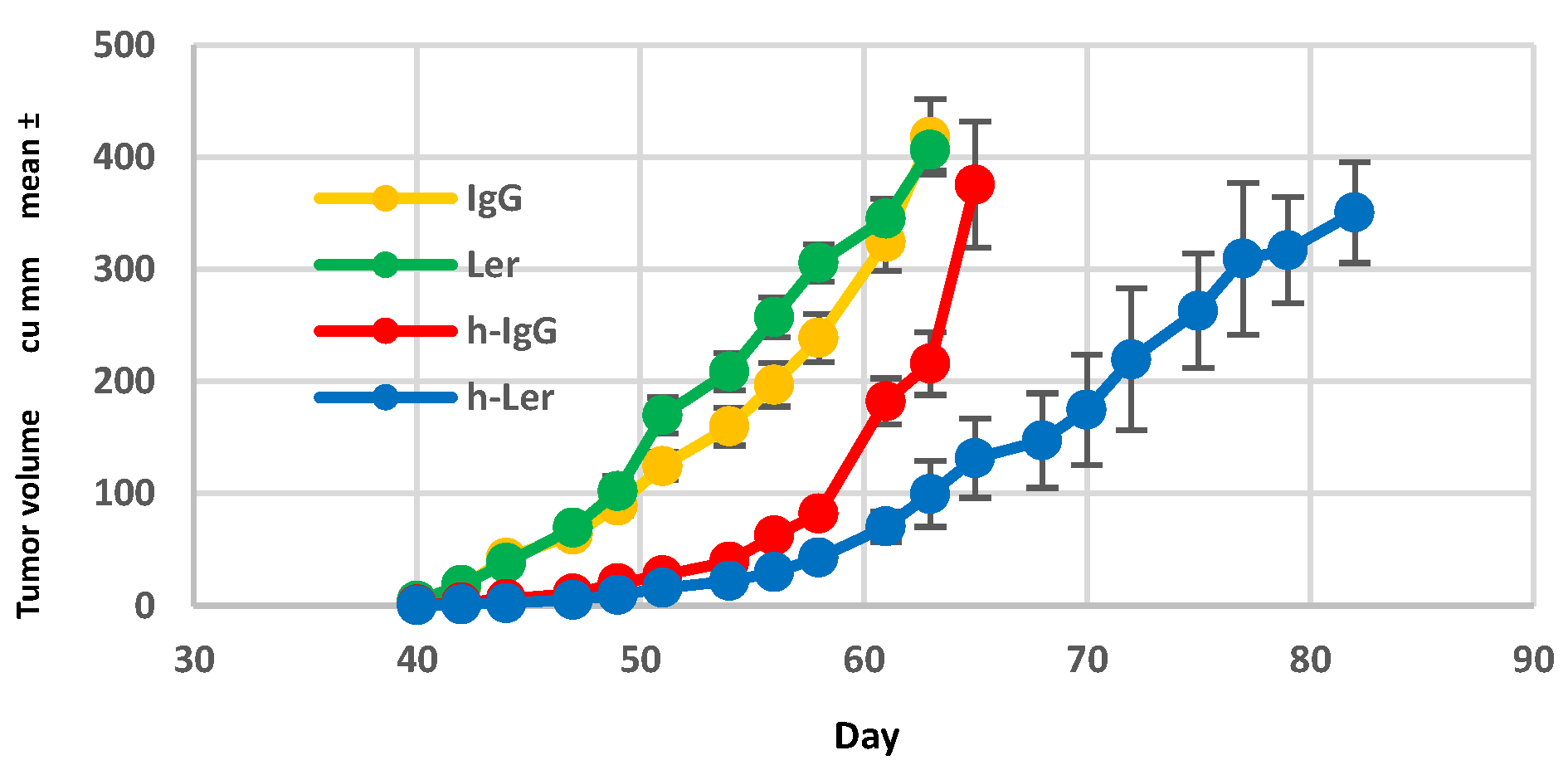

Human leukocyte engraftment was required for maximal inhibition of primary tumor growth. In non-humanized NSG mice, leronlimab did not suppress primary tumor growth rate (

Figure 3). In successfully engrafted mice (>25% human CD45 in peripheral blood) tumor growth was slowed by leronlimab treatment compared to mice receiving IgG, suggesting that the GVT effect mediated by humanization was clearly enhanced by blockade of CCR5 signal transduction following leronlimab

in vivo.

The role of NK cells in regulation and mediation GVHD is not well understood; many clinical trials involving transfer of NK cells into human allogeneic human stem cell transplant (HCT) patients have not been associated with GVHD [

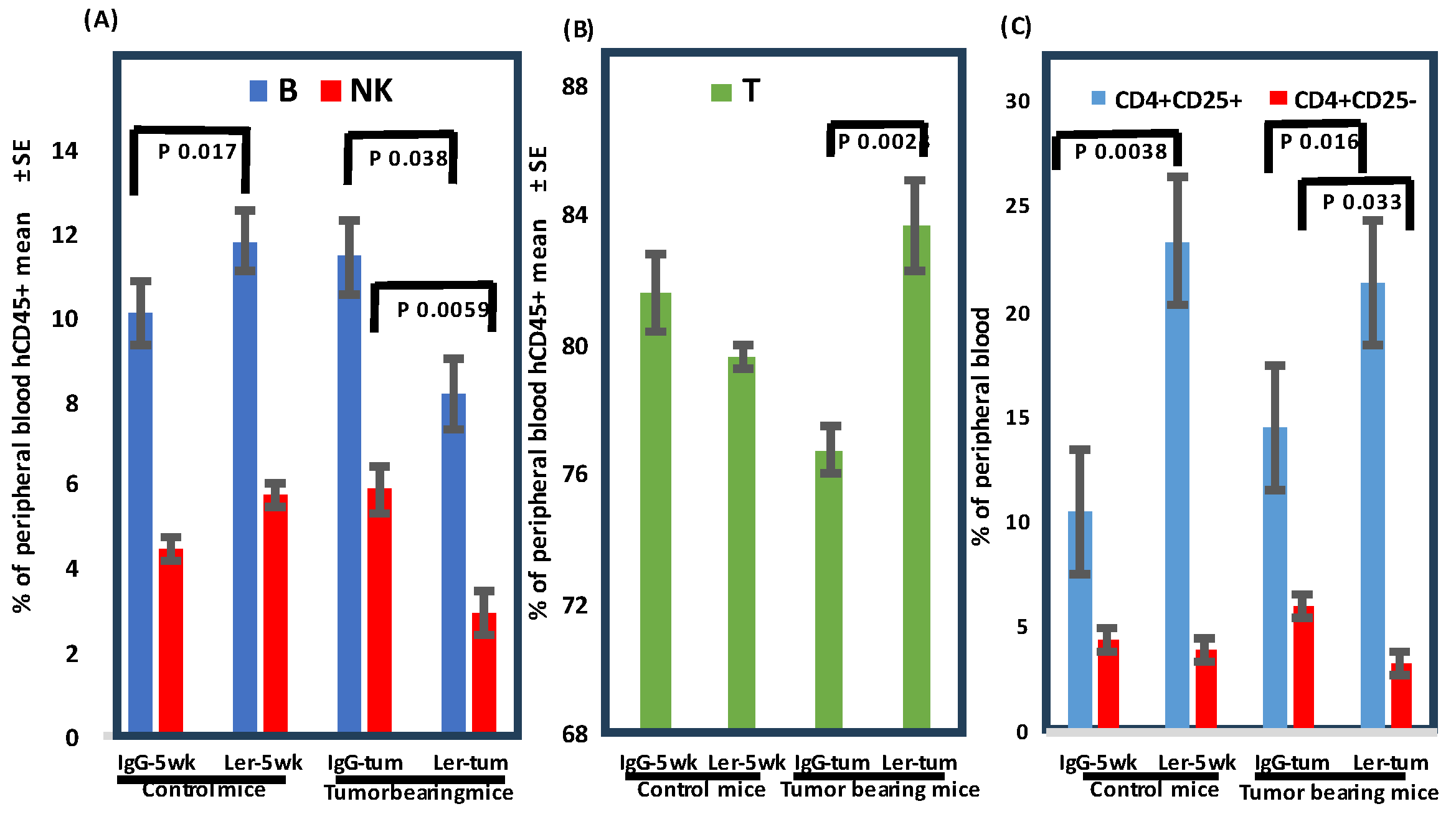

25]. Our humanized tumor-bearing mice displayed increased numbers of circulating human T cells and decreased percentages of human B and human NK cells following leronlimab (

Figure 4). Our initial impression was that increased cytotoxic T cells (CTL) in the peripheral blood was inconsistent with the observed decrease in GVHD. Analysis of the Treg subset was more instructive. In humanized tumor-bearing mice there was a clear induction of CD4

+CD25

+ (suppress GVHD) and decrease in percentage of CD4

+CD25

- (induce GVHD) cells (

Figure 5). Harvested tumors were examined by immunohistochemistry to assess infiltration of effector cells. Surprisingly, the tissue architecture was very homogenous, comprised solely of parenchymal tumor cells, with no evidence of human cells by immunohistochemistry.

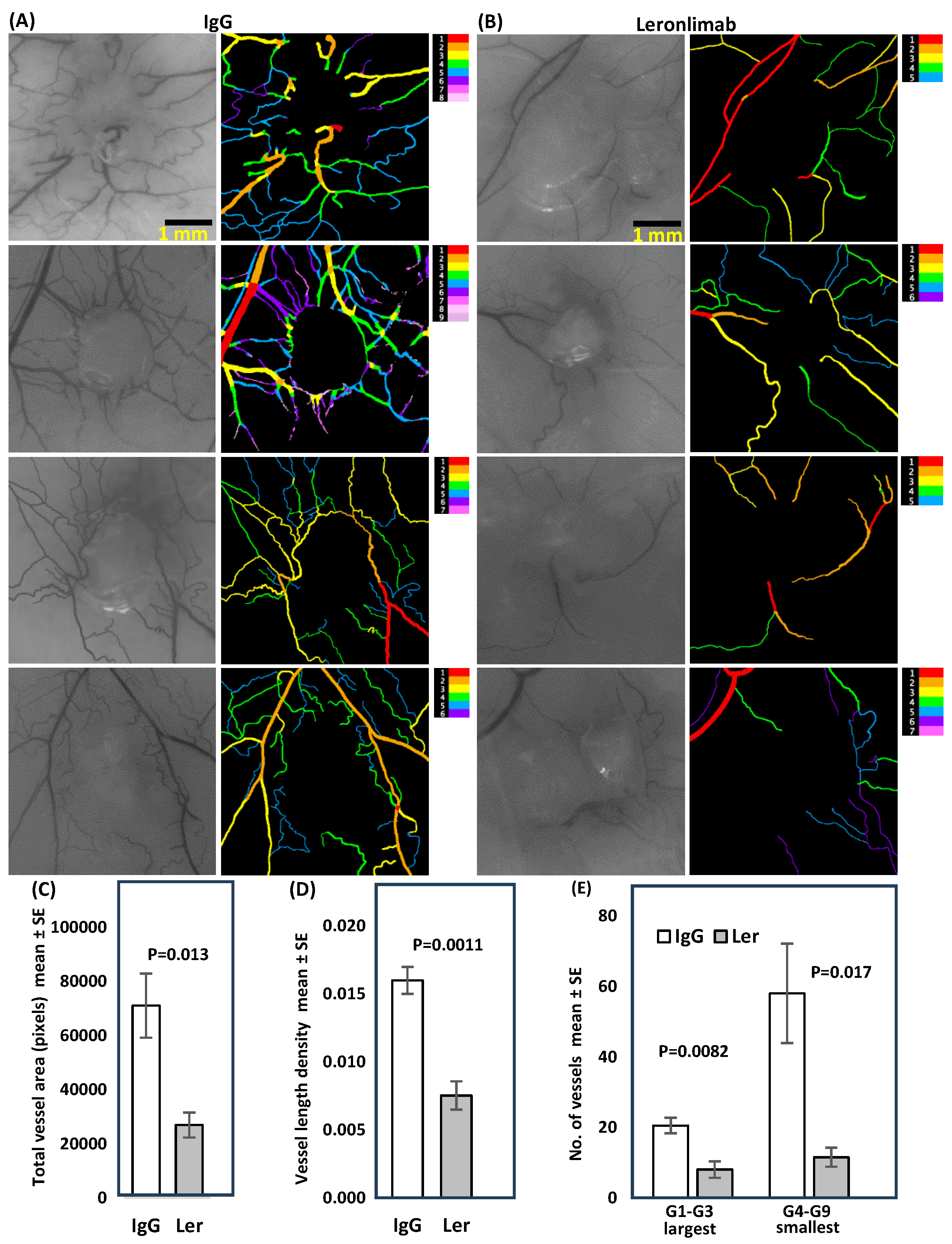

We considered host microenvironmental factors that affect early stages of tumor progression and metastasis. Angiogenesis is critical for tumors to progress beyond 2 mm in diameter [

19]. The intradermal angiogenic assay is one method used to quantitate vessel number, diameter, branching and networking. VESGEN, software developed by NASA, was used to analyze early SW480 tumors (

Figure 6). Previous studies with vessel generational analysis of VESGEN have consistently demonstrated the importance of the actively remodeling small vessels in progression of vascular-dependent pathologies such as malignant melanoma growth [

26], diabetic retinopathy [

27], and cytokine stimulation or inhibition of angiogenesis [

28]. Blockade of CCR5 signaling clearly interfered with host processes required for neo-vessel proliferation surrounding nascent growing tumors.

Our studies showed that CD4

+ cells, which are considered tumor immunosuppressive [

24]

were increased by leronlimab in the peripheral blood. CD4

+ T cells are now recognized to play key roles in both the priming and effector phases of the antitumor immune response [

22,

29]. In addition to providing T cell help through co-stimulation and cytokine production, CD4

+ T cells can also possess cytotoxicity either directly on MHC class II expressing tumor cells or to other cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME). The presence of specific populations of CD4

+ T cells, and their intrinsic plasticity, within the TME can represent an important determinant of clinical response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Furthermore, we found CCR5 expression correlated with the abundance of immune checkpoint gene expression in both MSS and populations of patients with MSI colon cancer.

In prior studies increased baseline percentages of CD4+CD25+ Tregs were associated with good prognosis in patients receiving the immune check point inhibitors ipilimumab [

20].

An increase in Treg percentage in advanced melanoma patients treated with neoadjuvant ipilimumab correlated with prolonged progression free survival [

21]

. Higher levels of circulating CD4+ T cells (CD62L

lo ) prior to PD-1 checkpoint blockade was significantly correlated with better response [

22]

. The induction of CD4+ cells by leronlimab is therefore consistent with a potential augmentation of responses to immune checkpoint therapy. Recent studies showed that patients with metastatic triple negative breast cancer who had received a mean of two prior types of therapy when treated with leronlimab and an ICI showed a favorable response with an 18% 4 years survival [

30].

The maintenance of high levels of CD4

+ T cells correlated significantly with patient survival, whereas a loss of this population of CD4

+ T cells after immune checkpoint blockade was correlated with resistance to ICB therapy. CD4

+ Tregs constitutively express high levels of surface receptors that are only upregulated by conventional T cells in response to activation, including PD-1 and CTLA-4, as well as a host of TNF receptor superfamily members such as OX-40 (CD134) and GITR

new approaches to improve CD4 responses before PD-L1/PD-1 blockade therapy [

31]

could be the solution to increase response rates and patient survival.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.J.L, D.R.B. and R.G.P; methodology, D.J.L., Y.A.P., R.P. and A.G.; software, P.P.W and R.P.; validation, J.A.D., P.P.W. and R.P; formal analysis, D.J.L., A.G. and R.P; investigation, D.J.L., R.G.P. and D.R.B.; resources, D.J.L. and D.R.B.; data curation, Y.A.P. and R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.J.L.; writing—review and editing, D.J.L., R.P., R.G.P. and D.R.B.; visualization, Y.A.P. and D.J.L.; supervision, D.J.L. and R.G.P.; project administration, K.G.; funding acquisition, D.J.L., R.P., R.G.P. and D.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Figure 1.

Growth of CCR5-expressing FACS sorted SW480 colon carcinoma. A. Following gating (FSC vs. SSC) to exclude debris, 6.70% of cells were included in gate 1. B. Histogram of APC positive cells from gate 1, Interval gate between 101 – 102 APC delineated the dim CCR5 positive cells, while the interval gate of 2.53 – 1.14 APC delineated the bright CCR5 positive cells. C. Sorted cells were inoculated into left flanks (dim, LO) and right flanks (bright, HI) of four non-irradiated NSG mice (2.5x105 cells per site). Hence each mouse bore 2 tumors and served as its own control, n=4. Tumor growth rate is depicted; no antibody treatment was given.

Figure 1.

Growth of CCR5-expressing FACS sorted SW480 colon carcinoma. A. Following gating (FSC vs. SSC) to exclude debris, 6.70% of cells were included in gate 1. B. Histogram of APC positive cells from gate 1, Interval gate between 101 – 102 APC delineated the dim CCR5 positive cells, while the interval gate of 2.53 – 1.14 APC delineated the bright CCR5 positive cells. C. Sorted cells were inoculated into left flanks (dim, LO) and right flanks (bright, HI) of four non-irradiated NSG mice (2.5x105 cells per site). Hence each mouse bore 2 tumors and served as its own control, n=4. Tumor growth rate is depicted; no antibody treatment was given.

Figure 2.

Leronlimab delays xGVHD onset in humanized SW480 tumor-bearing mice. Sub-lethally irradiated NSG mice were inoculated on day 0 with normal human BM (107 Ficoll-Hypaque purified mononuclear cells). Treatment groups: IgG-5wk: IgG 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk for 35 days then stopped (non-tumor bearing), Ler-5wk: Leronlimab 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk for 35 days then stopped (non-tumor bearing, IgG-tum: IgG 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk continuously, inoculated with SW480 (2.5x105 cells s.c.) on day 35, Ler-tum: Leronlimab 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk continuously, inoculated with SW480 on day 35, n=8 mice/group.

Figure 2.

Leronlimab delays xGVHD onset in humanized SW480 tumor-bearing mice. Sub-lethally irradiated NSG mice were inoculated on day 0 with normal human BM (107 Ficoll-Hypaque purified mononuclear cells). Treatment groups: IgG-5wk: IgG 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk for 35 days then stopped (non-tumor bearing), Ler-5wk: Leronlimab 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk for 35 days then stopped (non-tumor bearing, IgG-tum: IgG 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk continuously, inoculated with SW480 (2.5x105 cells s.c.) on day 35, Ler-tum: Leronlimab 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk continuously, inoculated with SW480 on day 35, n=8 mice/group.

Figure 3.

Effect of mouse humanization on leronlimab anti-tumor activity. NSG mice were either humanized (normal human BM, 107 mononuclear cells) or sham-injected, and then inoculated with SW480 (2.5x105 cells s.c.) on day 35. Humanized mice received either IgG (h-IgG) leronlimab (h-Ler). Non-humanized mice received IgG (IgG) or leronlimab (Ler). All groups received 2 mg antibody i.p. twice weekly, starting day 7, n=8 mice/group.

Figure 3.

Effect of mouse humanization on leronlimab anti-tumor activity. NSG mice were either humanized (normal human BM, 107 mononuclear cells) or sham-injected, and then inoculated with SW480 (2.5x105 cells s.c.) on day 35. Humanized mice received either IgG (h-IgG) leronlimab (h-Ler). Non-humanized mice received IgG (IgG) or leronlimab (Ler). All groups received 2 mg antibody i.p. twice weekly, starting day 7, n=8 mice/group.

Figure 4.

Effect of leronlimab on peripheral blood human B, T, NK cells, and T regulatory (Treg) cells. Sub-lethally irradiated NSG mice were inoculated with normal human BM mononuclear cells. Treatment groups: IgG-5wk: IgG 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk for 35d then stopped (non-tumor bearing), Ler-5wk: Leronlimab 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk for 35d then stopped (non-tumor bearing), IgG-tum: IgG 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk continuously, inoculated with SW480 (2.5x105 cells s.c.) on d35, Ler-tum: Leronlimab 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk continuously, inoculated with SW480 on d35, n=8 mice/group. Peripheral blood was analyzed on day 62 (gated on hCD45+). CD4+CD25+ cells suppress GVHD, whereas CD4+CD25- cells promote GVHD. Significant p values are indicated.

Figure 4.

Effect of leronlimab on peripheral blood human B, T, NK cells, and T regulatory (Treg) cells. Sub-lethally irradiated NSG mice were inoculated with normal human BM mononuclear cells. Treatment groups: IgG-5wk: IgG 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk for 35d then stopped (non-tumor bearing), Ler-5wk: Leronlimab 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk for 35d then stopped (non-tumor bearing), IgG-tum: IgG 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk continuously, inoculated with SW480 (2.5x105 cells s.c.) on d35, Ler-tum: Leronlimab 2 mg i.p. 2x/wk continuously, inoculated with SW480 on d35, n=8 mice/group. Peripheral blood was analyzed on day 62 (gated on hCD45+). CD4+CD25+ cells suppress GVHD, whereas CD4+CD25- cells promote GVHD. Significant p values are indicated.

Figure 5.

Leronlimab reduces luc-SW480 colon carcinoma metastasis in vivo. (A). Primary tumor initial luminescence was established at 10 days as shown. SW480 cells were inoculated orthotopically in the cecum of humanized NSG mice. On day 10, IVIS imaging was performed to demonstrate comparable levels of engraftment in both treatment groups (upper panels). (B). Liver luminescence was determined after leronlimab treatment. Mice received continuous antibody treatment. Following harvest on day 45, excised livers (C,D) and lungs (E,F) were incubated with luciferin substrate ex vivo. Leronlimab treatment resulted in decreased luminescence signal in livers (D, shown as mean + SEM for N=8 ) and lungs (lower panels).

Figure 5.

Leronlimab reduces luc-SW480 colon carcinoma metastasis in vivo. (A). Primary tumor initial luminescence was established at 10 days as shown. SW480 cells were inoculated orthotopically in the cecum of humanized NSG mice. On day 10, IVIS imaging was performed to demonstrate comparable levels of engraftment in both treatment groups (upper panels). (B). Liver luminescence was determined after leronlimab treatment. Mice received continuous antibody treatment. Following harvest on day 45, excised livers (C,D) and lungs (E,F) were incubated with luciferin substrate ex vivo. Leronlimab treatment resulted in decreased luminescence signal in livers (D, shown as mean + SEM for N=8 ) and lungs (lower panels).

Figure 6.

Leronlimab inhibits angiogenesis induced by SW480 tumors grown in the dermis of humanized NSG mice. Tumor cells (2 x 106) were inoculated in suspension in a volume of 0.1 mL PBS into the dermis of NSG mice. Antibody treatment was performed as above (2 mg i.p. 2x/wk). Ten days later mice were euthanized, and the inoculation site was photographed under 12.5x magnification. VESGEN software was used to analyze vessel number, diameter, branching, vessel generation number, and network characteristics. Total vessel area, vessel length density, large and small generations were all reduced in leronlimab treated mice. There was no difference in mean tumor area (p=0.91).

Figure 6.

Leronlimab inhibits angiogenesis induced by SW480 tumors grown in the dermis of humanized NSG mice. Tumor cells (2 x 106) were inoculated in suspension in a volume of 0.1 mL PBS into the dermis of NSG mice. Antibody treatment was performed as above (2 mg i.p. 2x/wk). Ten days later mice were euthanized, and the inoculation site was photographed under 12.5x magnification. VESGEN software was used to analyze vessel number, diameter, branching, vessel generation number, and network characteristics. Total vessel area, vessel length density, large and small generations were all reduced in leronlimab treated mice. There was no difference in mean tumor area (p=0.91).

Figure 7.

Gene expression correlation analysis of TCGA Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (COAD) samples. (A) The UCSC Xena platform was used for analysis and visualization of the gene expression correlations. For the 434 Colon and Rectal Cancer (COADREAD) samples with available RNAseq data, correlations between the expressions of CCR5 ligands and CCR5 and B) correlations between the expressions of immune checkpoint genes and CCR5 were assessed (see Spearman’s correlation rho values and associated p-values in Results). (C) Analysis of Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (COAD) MSS samples (dataset TCGA, Nature 2012) using cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics platform. Of the 193 COAD samples assigned as microsatellite stable (MSS), 166 samples had available RNAseq data. Gene expression correlations were assesed using these 166 samples. The gene names of the CCR5 ligands and D) immune checkpoint genes whose expressions are significantly correlated with CCR5 expression (Spearman’s correlation with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction; q-value<0.05) are depicted in bold.E) Pairwise expression correlations are depicted between CCR5 and the immune checkpoint genes HAVCR2, (F) PD-1 and (G) PD-L1, respectively in MSS samples.

Figure 7.

Gene expression correlation analysis of TCGA Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (COAD) samples. (A) The UCSC Xena platform was used for analysis and visualization of the gene expression correlations. For the 434 Colon and Rectal Cancer (COADREAD) samples with available RNAseq data, correlations between the expressions of CCR5 ligands and CCR5 and B) correlations between the expressions of immune checkpoint genes and CCR5 were assessed (see Spearman’s correlation rho values and associated p-values in Results). (C) Analysis of Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (COAD) MSS samples (dataset TCGA, Nature 2012) using cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics platform. Of the 193 COAD samples assigned as microsatellite stable (MSS), 166 samples had available RNAseq data. Gene expression correlations were assesed using these 166 samples. The gene names of the CCR5 ligands and D) immune checkpoint genes whose expressions are significantly correlated with CCR5 expression (Spearman’s correlation with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction; q-value<0.05) are depicted in bold.E) Pairwise expression correlations are depicted between CCR5 and the immune checkpoint genes HAVCR2, (F) PD-1 and (G) PD-L1, respectively in MSS samples.