1. Introduction

The rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most formidable threats to global public health in the 21st century [

1,

2]. The overuse and misuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics have accelerated the emergence of multidrug-resistant pathogens, rendering conventional treatments ineffective and increasing the risk of severe illness, prolonged hospitalization, and mortality [

3]. Levofloxacin, a third-generation fluoroquinolone, is a critical frontline antibiotic used to treat a wide range of severe bacterial infections, including respiratory, urinary tract, and skin infections [

4]. However, its efficacy is concentration-dependent and sub optimal dosing can not only lead to therapeutic failure but also contribute to the selection pressure that drives resistance [

5]. Consequently, the development of rapid, sensitive, and accessible methods for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of Levofloxacin is imperative to optimize patient outcomes and preserve the utility of this vital class of antibiotics [

6,

7].

Conventional analytical techniques for quantifying antibiotic levels, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and UV-Visible spectrophotometry, are considered the gold standard for accuracy [

2,

8]. However, these methods are often constrained by significant limitations, including laborious sample pre-treatment, reliance on expensive instrumentation, and the need for highly trained personnel [

9]. These drawbacks render them unsuitable for point-of-care applications or high-throughput screening, creating a critical technological gap for real-time monitoring in clinical and environmental settings [

10,

11]. To bridge this gap, fluorescent nanosensors have emerged as a powerful and promising alternative, offering advantages of high sensitivity, rapid response, and operational simplicity [

12,

13,

14].

Among the diverse family of nanomaterials, carbon quantum dots (CQDs) have garnered immense research interest as next-generation fluorescent probes [

15,

16,

17]. These zero-dimensional carbon nanoparticles possess a unique combination of advantageous properties, including excellent photostability, robust chemical inertness, high aqueous solubility, inherent biocompatibility and low toxicity [

18,

19,

20]. In recent years, a paradigm shift towards green and sustainable nanotechnology has spurred the synthesis of CQDs from abundant, renewable, and low-cost biomass precursors. This approach is a cornerstone of the circular economy, which seeks to transform waste streams into valuable resources [

21] Specifically, the valorization of agricultural waste, such as the cotton straw used in this study, addresses a significant environmental and logistical challenge, offering an elegant solution to convert a low-value environmental liability into a high-value technological asset. This strategy moves beyond simply finding a green precursor; it demonstrates a powerful application of green chemistry to create advanced functional materials for critical public health applications. Furthermore, the optical and electronic properties of CQDs can be precisely engineered through heteroatom doping [

22]. Nitrogen doping, in particular, has been shown to significantly enhance fluorescence quantum yield and create surface-active sites, thereby improving the sensitivity and selectivity of CQD-based sensors [

22,

23].

Addressing the urgent need for advanced antibiotic monitoring, a novel “turn-on” fluorescent sensor for levofloxacin was designed. This work demonstrates a sustainable and efficient synthesis route for N-CQDs from cotton waste, offering enhanced sensitivity for levofloxacin detection, with o-phenylenediamine serving a dual role as a nitrogen precursor and surface passivating agent. The resultant N-CQDs, which exhibit an exceptionally high quantum yield, function as a highly selective probe for levofloxacin. The sensing mechanism is based on a “turn-on” response, where specific analyte interactions inhibit non radiative photoinduced electron transfer (PET) processes, leading to a significant fluorescence enhancement. The superior analytical performance of this platform is demonstrated herein, including an ultralow limit of detection, validating its practical utility for the rapid and accurate quantification of Levofloxacin in complex pharmaceutical, food, and biological matrices.

2. Experimental Section

Cotton straw was sourced from a local farm in Shihezi, Xinjiang. Reagents, including o-Phenylenediamine (o-PDA, 99.5%), Levofloxacin (≥98%), and other antibiotics such as Ciprofloxacin, Tetracycline, and Amoxicillin, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. Other chemical reagents, such as NaCl, KCl, CaCl₂, glucose, and ascorbic acid, were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, along with quinine sulfate (for quantum yield determination). All aqueous solutions were prepared using ultrapure deionized water (18.2 MΩ·cm). Real samples, including pharmaceutical tablets (levofloxacin, 500 mg), raw milk, fresh chicken meat, and human urine, were sourced from local commercial suppliers.

The cotton straw was thoroughly washed with tap water followed by deionized water to remove any impurities. After cleaning, the straw was dried in a hot-air oven at 80 °C for 24 hours and then ground into a fine powder using a commercial grinder. The powder was sieved through a 100-mesh sieve to ensure uniformity before use. In the synthesis procedure, 1.0 g of pretreated cotton straw powder was mixed with 0.5 g of o-phenylenediamine (o-PDA) in 50 mL of ultrapure water. This mixture was sonicated for 15 minutes to form a homogeneous suspension, which was then transferred to a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. The sealed autoclave was heated in a laboratory oven at 180 °C for 10 hours. After the reaction, the autoclave was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. The resulting dark brown solution was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 minutes to remove large aggregates and carbonaceous sediments. The supernatant was collected and dialyzed against ultrapure water using a dialysis membrane with a molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) of 5000 Da for 48 hours to remove small molecular weight impurities. The final purified nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots (N-CQD) solution was stored in the dark at 4 °C for further use.

Characterization of the N-CQDs was performed using various techniques. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and High-Resolution TEM (HRTEM) images were captured on a JEOL JEM-2100 microscope with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra were obtained on a PerkinElmer Spectrum Two spectrometer using KBr pellets. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were conducted using a Thermo Fisher Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi system equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα source. UV-Visible absorption spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra were measured using a Horiba FluoroMax-4 spectrofluorometer. The fluorescence quantum yield (QY) was calculated using the comparative method with quinine sulfate in 0.1 M H2SO4 (QY = 54%) as the reference standard.

For the quantitative detection of levofloxacin, aliquots of a levofloxacin standard solution were added incrementally to 2.0 mL of the N-CQD solution to achieve final concentrations ranging from 0 to 40 nM. After each addition, the solution was incubated for 90 seconds before the fluorescence emission spectrum was recorded. The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated using the formula LOD = 3σ/k, where σ represents the standard deviation of the blank measurement and k is the slope of the linear calibration curve.

To assess the selectivity and stability of the N-CQDs, fluorescence measurements were performed using a bench-top spectrofluorometer with a 1.0 cm quartz cuvette at 25 ± 1 °C. Spectra were recorded at λex = 330 nm and λem = 422 nm, with 5 nm excitation and 5 nm emission band pass and an integration time of 0.5 s. All samples were prepared in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and baseline correction along with blank subtraction (buffer only) was applied. Absorbance at λex was kept below 0.10 to avoid inner-filter effects. Selectivity studies involved the addition of 1 µM of common potential interferents (including inorganic ions, small biomolecules, and structurally related analytes) to the N-CQD dispersion, and fluorescence responses were measured under identical conditions. Stability was evaluated by monitoring fluorescence intensity across pH values ranging from 2 to 14 (adjusted with HCl/NaOH), in the presence of NaCl concentrations ranging from 0 to 1 mM, and during long-term storage of the N-CQD dispersion for up to 180 days under dark, ambient conditions. Signals were normalized to the day-0 values where appropriate.

For real sample preparation, pharmaceutical tablets were finely powdered, and an amount corresponding to 10 mg of levofloxacin was dispersed in 100 mL of ultrapure water. This solution was sonicated for 15 minutes and filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter to obtain the stock extract. Raw milk (10 mL) was centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 15 minutes. The supernatant was collected and diluted 50-fold with ultrapure water. Minced chicken meat (5 g) was homogenized in 20 mL of acetonitrile, centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 15 minutes, and the supernatant was collected and diluted 50-fold with ultrapure water. A human urine sample was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was collected and diluted 100-fold with ultrapure water. This sample was anonymous and used solely for analytical method validation. Pre-treated matrices (milk, meat, urine) were spiked with known concentrations of levofloxacin and analyzed against an external calibration curve. Fluorescence measurements were performed under the conditions described previously (10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). Percent recovery was calculated using the formula:

Where Cfound was the concentration back-calculated from the calibration curve, and Cspiked was the concentration of levofloxacin added to the matrix before analysis. Matrix dilution factors were applied (milk 50×, meat 50×, urine 100×).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Optimization of Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots (N-CQDs)

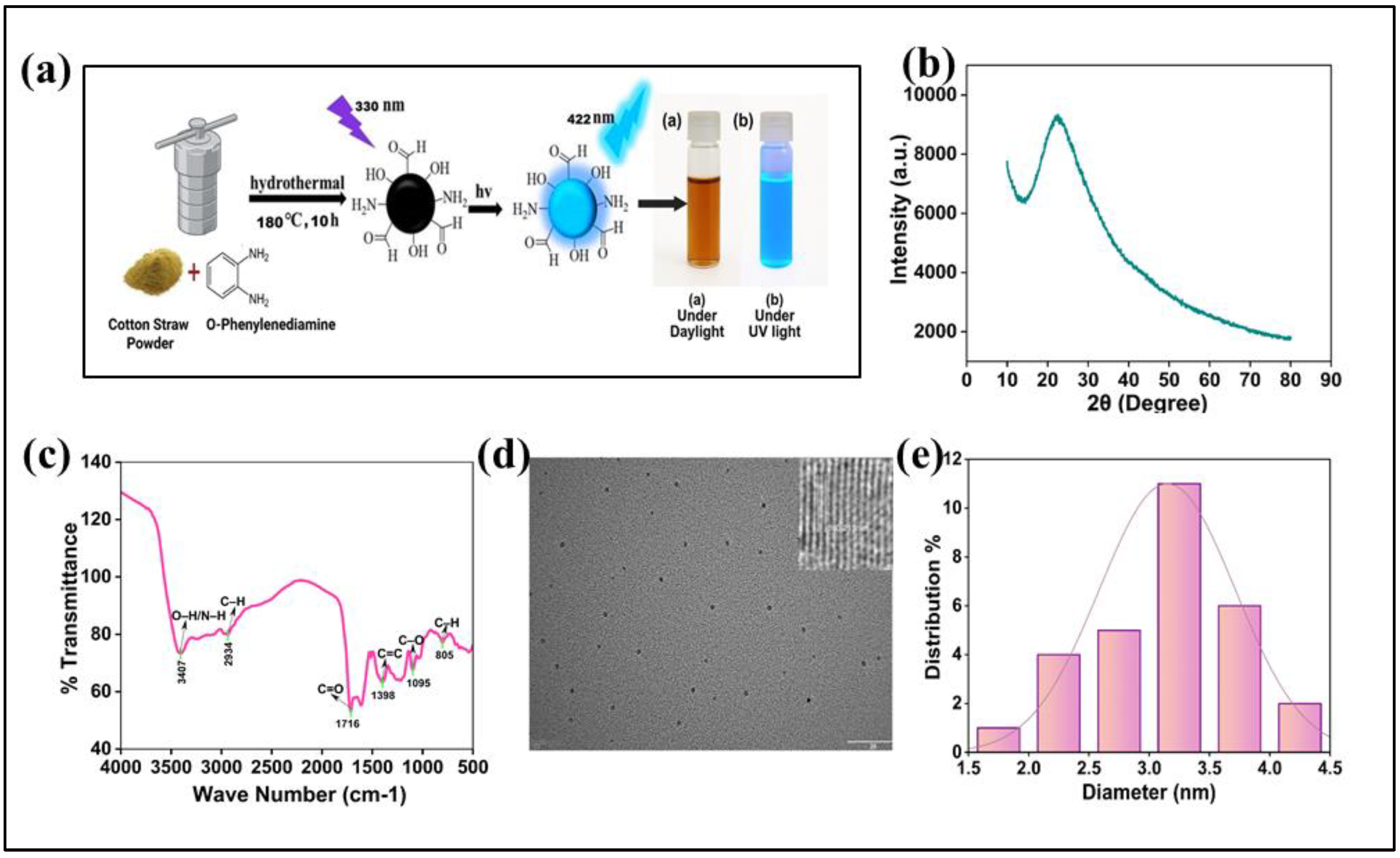

This work describes the fabrication of highly fluorescent N-CQDs through a facile, one-pot hydrothermal carbonization of cotton waste (

Figure 1a) [

22,

23]. In this green synthesis strategy,

o-phenylenediamine (o-PDA) served a dual role as both the nitrogen-doping precursor and a surface passivating agent [

24,

25]. During the hydrothermal treatment, the cellulosic biomass undergoes sequential dehydration, hydrolysis, and aromatization to form the foundational carbon cores [

26,

27]. Concomitantly, o-PDA facilitates the in situ incorporation of nitrogen heteroatoms into the nascent carbon lattice while functionalizing the surface, a process critical for achieving superior photoluminescence [

28].

To maximize the optical performance of the N-CQDs, we systematically optimized the key synthesis parameters, namely reaction temperature and duration, with the fluorescence quantum yield (QY) as the primary figure of merit (

Table 1) [

29,

30]. The reaction temperature proved to be a critical determinant of QY. A systematic variation from 160 °C to 200 °C revealed an optimal temperature of 180 °C, which yielded a remarkable QY of 42%. Lower temperatures resulted in incomplete carbonization (QY = 21% at 160 °C), whereas higher temperatures led to a diminished QY (33% at 200 °C), likely attributable to excessive graphitization and the formation of non-radiative quenching sites [

31]. Similarly, the reaction duration was optimized to 10 hours. Consequently, all subsequent N-CQD batches were synthesized under these optimal conditions (180 °C, 10 h) to ensure reproducibility and maximal fluorescence performance.

3.2. Structural and Spectroscopic Characterization

The structural and chemical properties of the as-synthesized N-CQDs were elucidated using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. The XRD pattern (

Figure 1b) displayed a single, broad diffraction halo centered at 2θ ≈ 22.1°, corresponding to the (002) plane of amorphous carbon [

32]. This feature signifies a low degree of crystallinity, which is characteristic of carbon dots. The interlayer d-spacing calculated from this peak is approximately 0.40 nm, a value significantly larger than that of bulk graphite (0.34 nm). This expanded spacing suggests a disordered stacking of graphene-like layers, interrupted by structural defects and the abundant surface functional groups introduced during synthesis [

33].

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to probe the surface chemistry of the N-CQDs (

Figure 1c). The spectrum is dominated by a broad absorption band at ~3407 cm⁻¹, which is assigned to the O-H and N-H stretching vibrations, confirming successful surface passivation. The peak at 2934 cm⁻¹ corresponds to aliphatic C-H stretching modes. A prominent absorption at 1716 cm⁻¹ is indicative of C=O stretching from carbonyl or carboxyl moieties. The spectral region also reveals features at 1398 cm⁻¹ (C=C stretching or N-H bending) and a strong absorption at 1095 cm⁻¹ characteristic of C-O stretching vibrations [

34]. Finally, the peak at 805 cm⁻¹ is attributed to C-H out-of-plane bending in aromatic systems [

34]. Collectively, the FTIR analysis confirms that the N-CQDs possess a rich surface chemistry, densely functionalized with hydrophilic oxygen- and nitrogen-containing groups that are essential for their excellent aqueous colloidal stability and potent photoluminescence [

35,

36].

3.3. Morphological and Nanostructural Analysis

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was utilized to investigate the morphology and size distribution of the N-CQDs. The low-magnification TEM image (

Figure 1d) reveals that the N-CQDs are monodisperse, quasi-spherical nanoparticles with no significant aggregation, attesting to their high colloidal stability [

37]. A statistical analysis of over 100 particles from multiple TEM images yielded a narrow size distribution with a mean diameter of 3.2 nm [

23] (

Figure 1e). This ultra small and uniform particle size is a prerequisite for observing quantum confinement effects, which are known to govern the optical behavior of carbon dots [

38]. High-resolution TEM (HRTEM), shown in the inset of

Figure 1(d), provides further insight into the nanostructure, revealing distinct lattice fringes with a d-spacing of 0.21 nm. This spacing is consistent with the (100) plane of graphitic carbon, confirming the presence of a crystalline sp²-hybridized carbon core within the amorphous, functionalized shell.

3.4. Elemental Composition and Chemical State Analysis

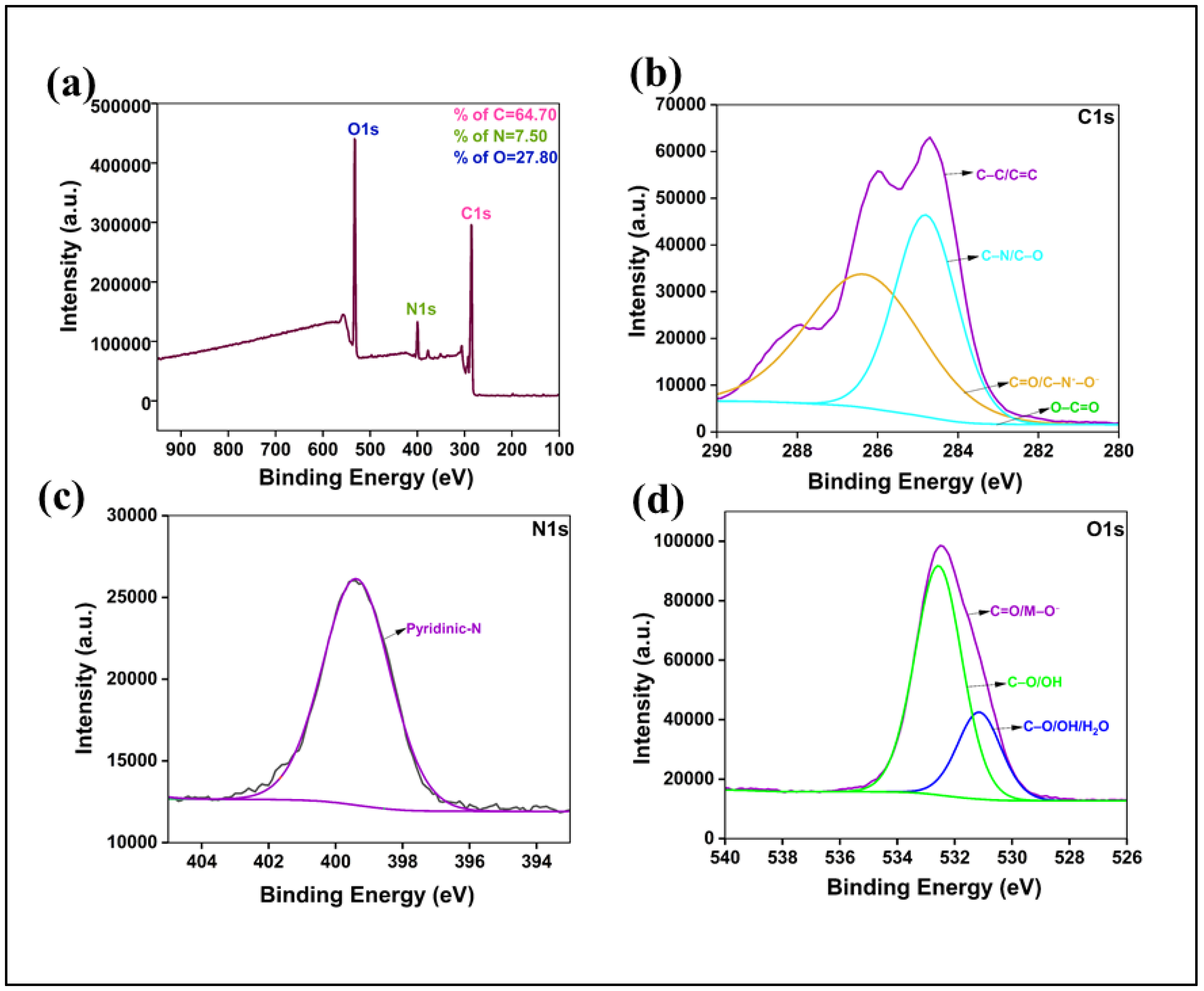

To quantitatively determine the elemental composition and chemical bonding states, we performed X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The survey spectrum (

Figure 2a) confirmed the presence of carbon (64.89 at%), oxygen (27.81 at%), and nitrogen (7.5 at%), verifying the successful incorporation of nitrogen from the o-PDA precursor. The high-resolution C 1s spectrum (

Figure 2b) was deconvoluted into three primary components corresponding to sp²-hybridized C-C/C=C (284.8 eV), C-O/C-N bonds (~286.0 eV), and C=O/O-C=O moieties (~288.5 eV), which constitute the core and surface structures [

39]. The O 1s spectrum (

Figure 2d) was similarly resolved into peaks for C=O (~531.0 eV) and C-OH/C-O-C (~532.3 eV), corroborating the FTIR analysis. Critically, the high-resolution N 1s spectrum (

Figure 2c) provided insight into the nitrogen configuration within the carbon matrix. The spectrum could be deconvoluted into components representing pyridinic, pyrrolic, and graphitic nitrogen species [

39]. The successful N-doping and rich surface functionalization are known to be instrumental in modulating the electronic structure and enhancing the fluorescence efficiency of carbon dots [

40,

41].

3.5. Sensor Stability and Selectivity

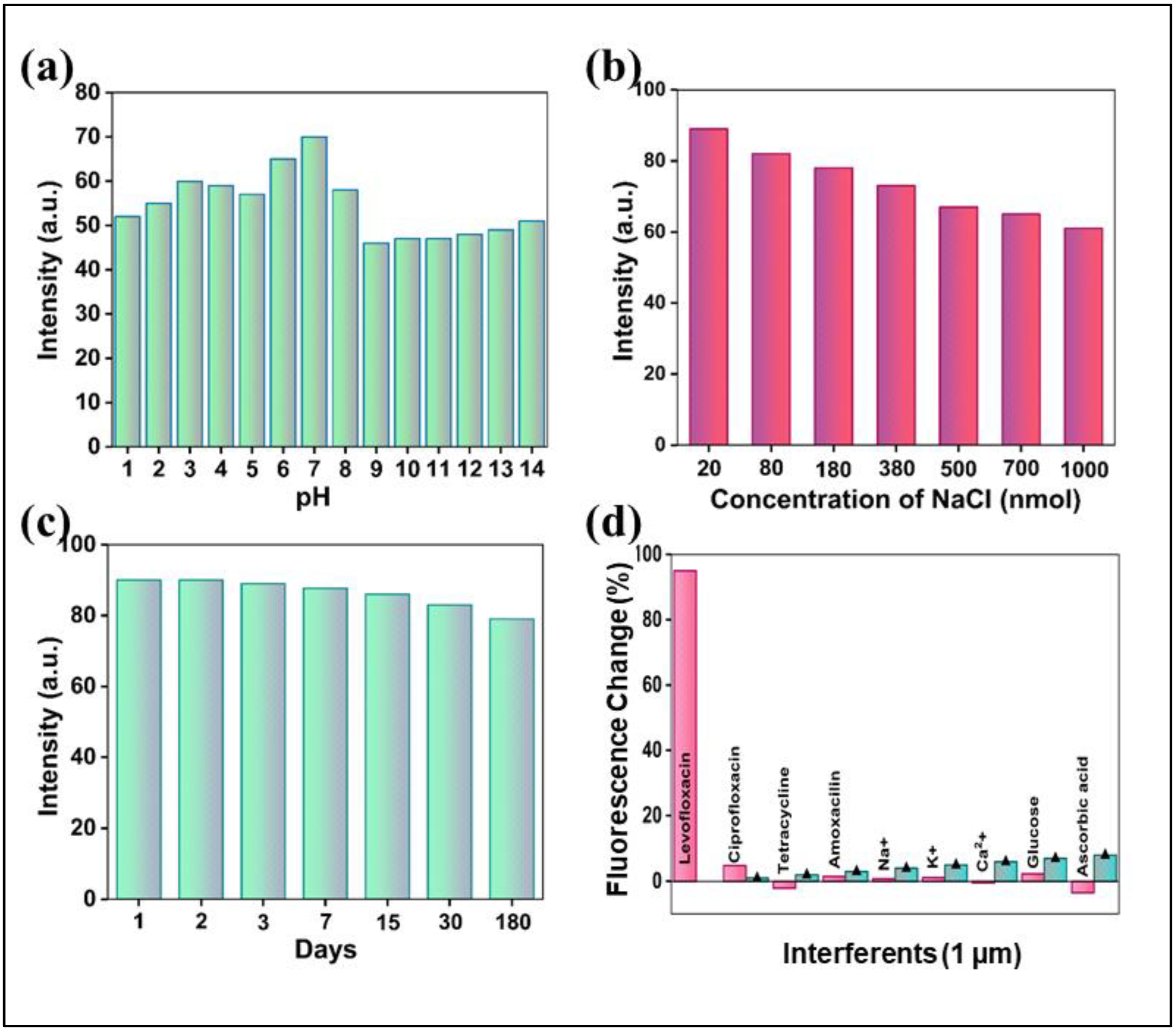

For any practical sensing application, the robustness and specificity of the probe are paramount. We therefore rigorously evaluated the stability of the N-CQD sensor under various environmental conditions. The fluorescence intensity of the N-CQDs remained exceptionally stable across a broad pH range of 2–14, with optimal performance observed between pH 6 and 8 (

Figure 3a)[

42,

43]. The sensor also demonstrated remarkable tolerance to high ionic strength, with negligible fluorescence loss in NaCl concentrations up to 1000 µM (

Figure 3b)[

44]. Furthermore, the N-CQDs exhibited excellent long-term photostability, retaining a majority of their initial fluorescence intensity after 180 days of storage under ambient conditions (

Figure 3c), underscoring their suitability for long-term use [

45].

The selectivity of the N-CQD probe was assessed against a panel of potential interferents, including common antibiotics, metal ions, and biological molecules [

46]. As depicted in

Figure 3d (evofloxacin bars), the sensor exhibited a profound and specific fluorescence enhancement in the presence of levofloxacin. In stark contrast, all other tested substances induced only negligible changes in fluorescence. To further probe the sensor's anti-interference capability, recovery experiments were conducted by detecting levofloxacin in the presence of these interferents (

Figure 3d, green bars). The consistently high recovery rates (

Table 2) confirm that co-existing species do not compromise the accurate quantification of levofloxacin, highlighting the exceptional selectivity and anti-interference properties of the sensor [

47].

3.6. Photophysical Properties

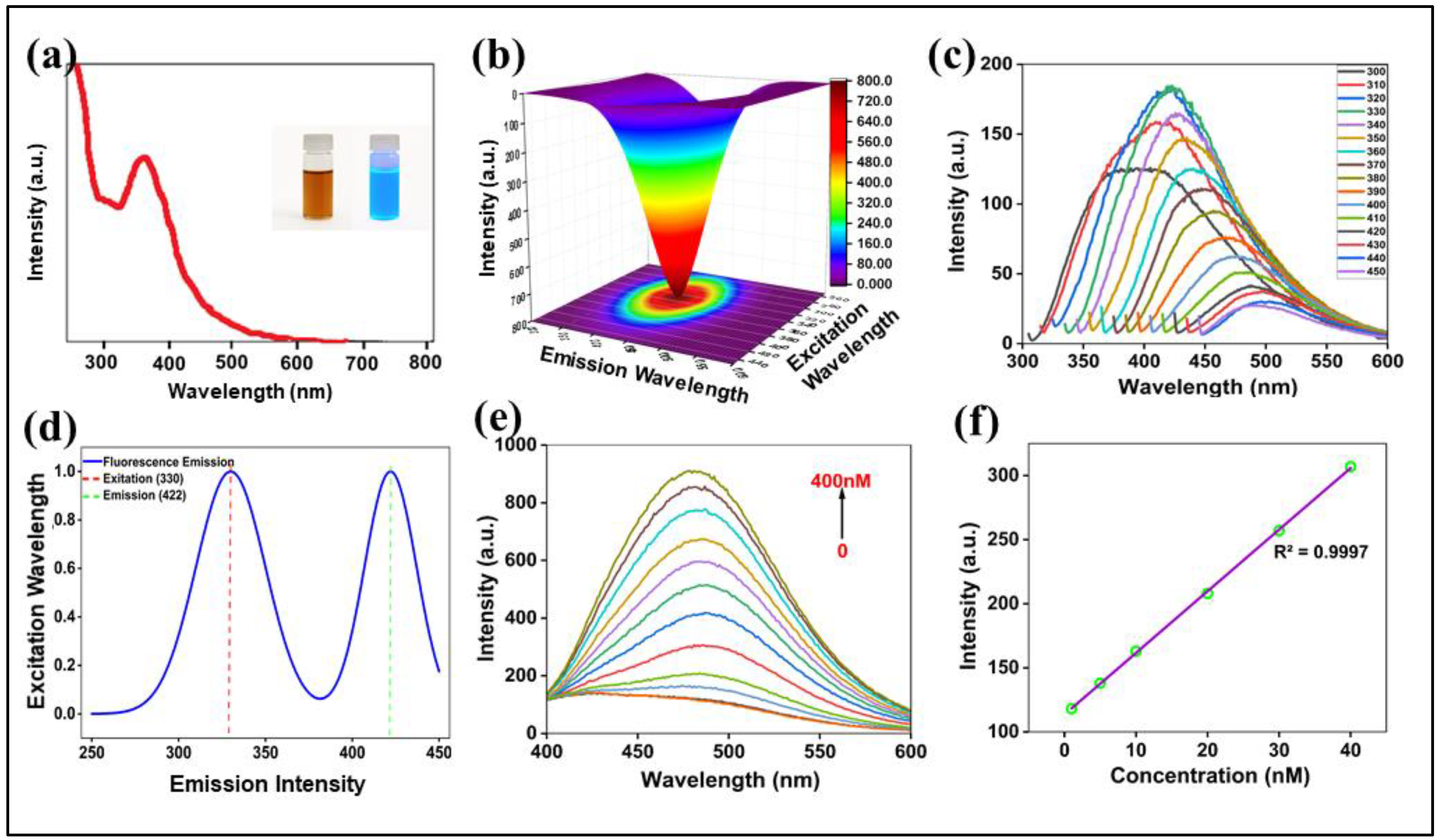

The optical characteristics of the N-CQDs were investigated by UV-Visible absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy. The UV-Vis spectrum (

Figure 4a) features a prominent absorption peak at ~340 nm, which is assigned to n→π* electronic transitions associated with surface functional groups containing C=O and C-N bonds. Visually, the aqueous N-CQD solution appears yellowish-brown under ambient light and emits a strong, bright blue fluorescence when irradiated with 365 nm UV light (

Figure 4a, inset).

The fluorescence spectra (

Figure 4d) reveal an optimal excitation wavelength at 330 nm, which produces a maximum emission at 422 nm, resulting in a large Stokes shift of ~92 nm, which is highly beneficial for sensing applications as it minimizes self-absorption and spectral overlap between the excitation and emission signals, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio [

48]. A hallmark of carbon dots is their excitation-dependent PL behavior, which was clearly observed for our N-CQDs (

Figure 4c). As the excitation wavelength was systematically increased from 300 nm to 450 nm, the corresponding emission peak exhibited a progressive red-shift. This phenomenon, visualized in the 3D excitation-emission matrix plot (

Figure 4b), is attributed to the heterogeneous distribution of surface energy states and particle sizes, where different excitation energies selectively activate distinct emissive trap sites [

49,

50].

3.7. Levofloxacin Sensing Performance and Mechanism

Incremental additions of levofloxacin produced a systematic “turn-on” increase in N-CQD fluorescence at λem = 422 nm: λex = 330 nm (

Figure 4e). The calibration plot of fluorescence intensity versus levofloxacin concentration (

Figure 4f) was linear from 1.83 to 40 nM and was described by

Calibration used multiple concentration levels, each measured in triplicate. The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) were calculated as LOD = 3σ/k and LOQ = 10σ/k, where σ is the standard deviation of blank signals and k is the calibration slope; this yielded LOD ≈ 0.55 nM and LOQ ≈ 1.83 nM, confirming high sensitivity within the validated range [

51].

The observed “Turn-On” fluorescence enhancement is consistent with a mechanism involving the inhibition of non-radiative decay pathways upon analyte binding. In the field of carbon dot-based sensors, Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET) is a well-documented process responsible for fluorescence quenching. In such systems, photoexcited carbon dots can act as either electron donors or acceptors, and interaction with a suitable quencher molecule opens a non-radiative de-excitation channel, thus quenching fluorescence [

52,

53,

54,

55].

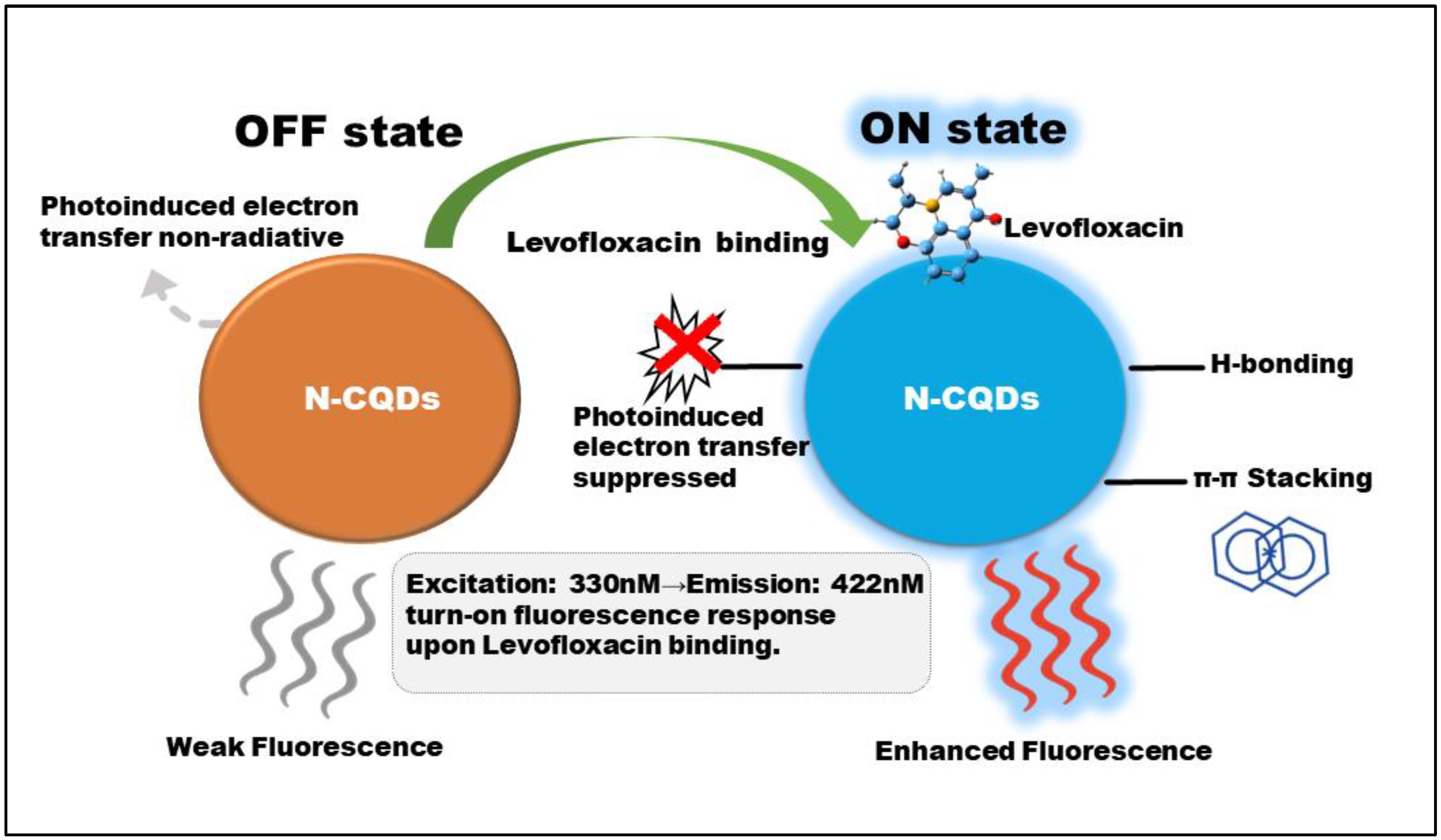

We propose that a similar PET process is the most plausible mechanism governing the N-CQD sensor's response (

Figure 5). In the absence of the analyte, the N-CQDs may exist in a partially quenched “OFF state” due to interactions that facilitate PET. Upon the introduction of Levofloxacin, specific molecular interactions likely hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking between the analyte and the rich functional groups on the N-CQD surface alter the electronic structure of the complex. This binding event can disrupt the energetically favorable pathway for PET, effectively inhibiting this non-radiative process. By closing the non-radiative channel, the radiative decay pathway is restored, leading to the observed fluorescence enhancement or “turn-on” effect [

56]. Although the proposed PET inhibition mechanism aligns with the observed turn-on behavior, further validation using time-resolved photoluminescence or transient absorption spectroscopy would provide direct experimental evidence for this process.

While other mechanisms such as chelation-enhanced fluorescence (CEF) can also produce a “turn-on” response, the PET inhibition model is strongly supported by numerous studies on fluorescent sensors involving aromatic analytes and functionalized carbon dots. Direct validation of this dynamic quenching mechanism would ideally involve time-resolved photoluminescence spectroscopy to measure changes in the fluorescence lifetime. Such investigations are a direction for our future work to provide definitive experimental evidence for the proposed mechanism [

57].

3.8. Application in Real Sample Analysis

To validate the practical utility and robustness of the N-CQD sensor, we performed spike-and-recovery experiments in several complex real-world matrices: pharmaceutical tablets, milk, chicken meat extract, and urine. The results, summarized in

Table 3, unequivocally demonstrate the sensor’s excellent performance. Across all tested samples, the sensor yielded outstanding recovery percentages, ranging from 93% to 105%, with low relative standard deviations (RSDs) consistently below 4%. These high recovery rates and excellent precision in complex biological and food matrices underscore the sensor's accuracy, reliability, and potent anti-interference capability [

58]. The results strongly support the potential of this N-CQD sensor for practical applications in diverse fields, including pharmaceutical quality control, food safety analysis, and clinical diagnostics [

59].

3.9. Comparative Performance Analysis

To contextualize the performance of our sensor, we benchmarked its key analytical metrics against other reported methods for levofloxacin detection (

Table 4). The developed N-CQD sensor exhibits a linear range of 1.83–40 nM and an impressive limit of detection (LOD) of 0.549 nM. This sensitivity is highly competitive with, or superior to, many existing fluorescence-based methods, including those derived from citrus (LOD: 2.1 nM) and even the standard HPLC-Fluorescence technique (LOD: ~1.7 nM). While some highly engineered systems incorporating molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) or ratiometric probes report slightly lower LODs (0.38–0.7 nM), our sensor achieves a comparable level of elite sensitivity. Crucially, this performance is achieved via a significantly simpler and more sustainable synthesis route, positioning our cotton-derived N-CQD platform as a powerful, green, and highly competitive alternative for the ultrasensitive detection of Levofloxacin.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we have successfully developed a highly sensitive and selective “turn-on” fluorescent sensor for the antibiotic levofloxacin based on nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots (N-CQDs) synthesized through a facile, scalable, and green hydrothermal method using cotton waste as a sustainable carbon precursor. The optimized N-CQDs exhibit a high fluorescence quantum yield of 42%, excellent photostability, and robust performance across a wide range of pH and ionic strengths. The developed sensing platform demonstrates outstanding analytical performance, with an ultralow limit of detection (0.55 nM) and a broad linear range for levofloxacin detection. Critically, the sensor shows exceptional selectivity, with negligible interference from a wide panel of common antibiotics, ions, and biomolecules. The practical applicability of this method was rigorously validated through spike-and-recovery experiments in complex matrices, including pharmaceutical tablets, milk, chicken meat, and urine, yielding excellent recovery rates and confirming its accuracy and reliability for real-world applications. This work not only presents a superior analytical tool that rivals or surpasses many existing methods for levofloxacin detection but, more broadly, provides a compelling demonstration of the circular economy in action. We have successfully transformed a globally abundant agricultural waste product into a high-performance nanosensor capable of addressing critical challenges in public health and food safety. The powerful synergy of sustainable synthesis and elite analytical performance (0.55 nM LOD) positions this N-CQD platform as a significant advance. It underscores a viable and scalable strategy for developing next-generation functional materials that are not only effective but also inherently sustainable, paving the way for future innovations at the intersection of materials science, green chemistry, and analytical technology.

Author Contributions

Anam Arshad and Zubair Akram conceived and designed the study, carried out the experimental investigation, curated and analyzed the data, and drafted the original manuscript. Nan Wang validated the data, supervised the research activities, and provided critical review and editing of the manuscript. Naveed Ahmed and Sajida Noureen contributed to the experimental investigation, and visualization of results. Feng Yu supervised the project, validated the analyses, and contributed to data visualization and manuscript refinement. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability: Data presented in this manuscript will be available from corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Xinjiang Science and Technology Program (2023TSYCCX0118).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yoo, J.-H. Antimicrobial Resistance—The “Real” Pandemic We Are Unaware Of, Yet Nearby. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2025, 40, e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafale, N.A.; Semwal, U.P.; Rajput, R.K.; Singh, G. Selection of Appropriate Analytical Tools to Determine the Potency and Bioactivity of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarrant, C.; Colman, A.M.; Jenkins, D.R.; Chattoe-Brown, E.; Perera, N.; Mehtar, S.; et al. Drivers of Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Overuse across Diverse Hospital Contexts—A Qualitative Study of Prescribers in the UK, Sri Lanka and South Africa. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, A.; Munteanu, A.-C.; Arbănași, E.-M.; Uivarosi, V. Overview of Side-Effects of Antibacterial Fluoroquinolones: New Drugs versus Old Drugs, a Step Forward in the Safety Profile? Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, C.; Koulenti, D.; Novy, E.; Roberts, J.; Dahyot-Fizelier, C. Optimization of Antimicrobial Therapy in Critically Ill Patients, What Clinicians and Searchers Must Know. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2025, —, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.S.; Beaulieu-Jones, B.; Smalley, S.; Snyder, M.; Goetz, L.H.; Schork, N.J. Emerging Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Technologies: Considerations and Opportunities in Precision Medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1348112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicha, S.G.; Märtson, A.G.; Nielsen, E.I.; Koch, B.C.; Friberg, L.E.; Alffenaar, J.W.; et al. From Therapeutic Drug Monitoring to Model-Informed Precision Dosing for Antibiotics. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 109, 928–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, T.Y.A.; Pashameah, R.A.; Binsaleh, A.Y.; Mohamed, M.A.; Ahmed, H.A.; Nassar, H.F. Condition Optimization of Eco-Friendly RP-HPLC and MCR Methods via Box–Behnken Design and Six Sigma Approach for Detecting Antibiotic Residues. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhole, S.M.; Amnerkar, N.D.; Khedekar, P.B. Comparison of UV Spectrophotometry and High Performance Liquid Chromatography Methods for the Determination of Repaglinide in Tablets. Pharm. Methods 2012, 3, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbehiry, A.; Marzouk, E.; Abalkhail, A.; Abdelsalam, M.H.; Mostafa, M.E.; Alasiri, M.; et al. Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance via State-of-the-Art Technologies versus Conventional Methods. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1549044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, D.; Uskoković, V.; Wakil, A.M.; Goni, M.D.; Shamsuddin, S.H.; Mustafa, F.H.; et al. Current and Future Technologies for the Detection of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, W.; Lin, H.; Zhang, M.; Sun, C. Recent Advances of Fluorescent Aptasensors for the Detection of Antibiotics in Food. Biosensors 2025, 15, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Chakraborty, J.; Mandal, P.; Mondal, R.; Mandal, A.K. From Lab to Field: Revolutionizing Antibiotic Detection with Aptamer-Based Biosensors. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 18920–18946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Huang, Q.; Yuan, L.; Yan, S.; Mo, Y.; Ying, Y.; et al. Tailored Fluorescent Metal–Organic Frameworks Hybrid Membrane Sensor Arrays: Simultaneous and Selective Quantification of Multiple Antibiotics. Adv. Sci. 2025, 2502452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Y.; Shen, W.; Gao, Z. Carbon Quantum Dots and Their Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Wang, Z.; Ge, J.; Gong, W.; Nan, K.; Liu, Z.; et al. Recent Advances of Fluorescent Carbon Dots for Biological Imaging and Biosensing. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 165135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasal, A.S.; Yadav, S.; Yadav, A.; Kashale, A.A.; Manjunatha, S.T.; Altaee, A.; et al. Carbon Quantum Dots for Energy Applications: A Review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 6515–6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xu, T.; Li, H.; She, M; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Zero-Dimensional Carbon Nanomaterials for Fluorescent Sensing and Imaging. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 11047–11136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, W.; Khalid, A.; Arshad, N.; Asghar, M.S.; Irshad, M.S.; Wang, X.; et al. Recent Progress and Perspective of an Evolving Carbon Family from 0D to 3D: Synthesis, Biomedical Applications, and Potential Challenges. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 2043–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, T.; Liang, R.; Wei, M. Application of Zero-Dimensional Nanomaterials in Biosensing. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, A.A.; Ehrens, A.; Zheng, Y.; Nowack, B. Developing Trends in Nanomaterials and Their Environmental Implications. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2023, 18, 834–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangaraj, B.; Solomon, P.R.; Chuangchote, S.; Wongyao, N.; Surareungchai, W. Biomass-Derived Carbon Quantum Dots—A Review. Part 1: Preparation and Characterization. Chem. Bio. Eng. Rev. 2021, 8, 265–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Shen, D.; Wu, C.; Gu, S. State-of-the-Art on the Preparation, Modification, and Application of Biomass-Derived Carbon Quantum Dots. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 22017–22039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Yang, L.-P.; Wang, L.-L. Synthetic Strategies, Properties and Sensing Application of Multicolor Carbon Dots: Recent Advances and Future Challenges. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 8117–8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Ren, L. Large Scale Synthesis of Carbon Dots and Their Applications: A Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Biswal, B.K.; Zhang, J.; Balasubramanian, R. Hydrothermal Treatment of Biomass Feedstocks for Sustainable Production of Chemicals, Fuels, and Materials: Progress and Perspectives. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 7193–7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, Q.; Cui, D.; Wu, D.; Bai, J.; Qin, H.; et al. Insights into the Chemical Structure Evolution and Carbonisation Mechanism of Biomass during Hydrothermal Treatment. J. Energy Inst. 2023, 108, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Hao, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; et al. Recent Advances in Highly Luminescent Carbon Dots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2420587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Li, F; Liang, Y.; Tang, Y. Enhancing the Quantum Yield and Electrochemical Properties of Carbon Quantum Dots via Optimized Hydrothermal Treatment Using Cellulose Nanocrystals as Precursors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Du, W.; Liu, S.; Qiao, Z.; Zhou, Y. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Biomass-Derived CQDs: Advances and Applications. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2025, 14, 20250184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Tao, M.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Insight into Structure Evolution of Carbon Nitrides and Its Energy Conversion as Luminescence. Carbon Energy 2024, 6, e463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Pang, J.; Tang, Y.; Ma, M.; Huang, J.; Li, P.; et al. Bulk Amorphous Carbon with Lightweight, High Strength, and Electrical Conductivity: Onion-Like Carbon Structures Embedded in Disordered Graphene Networks. Inorg. Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Fang, S.; Hu, Y.H. 3D Graphene Materials: From Understanding to Design and Synthesis Control. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 10336–10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Deng, Y.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Green Preparation of Fluorescent Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots for Sensitive Detection of Oxytetracycline in Environmental Samples. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, R.; Yukta, Y.; Mondal, J.; Kumar, R.; Pani, B.; Singh, B. Carbon Dots: Synthesis, Characterizations, and Recent Advancements in Biomedical, Optoelectronics, Sensing, and Catalysis Applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 2086–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.G.; Huš, M.; Baragau, I.A.; Bowen, J.; Heil, T.; Nicolaev, A.; et al. Engineering Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots: Tailoring Optical and Chemical Properties through Selection of Nitrogen Precursors. Small 2024, 20, 2310587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Li, Z.; Geng, X.; Lei, Z.; Karakoti, A.; Wu, T.; et al. Emerging Trends of Carbon-Based Quantum Dots: Nanoarchitectonics and Applications. Small 2023, 19, 2207181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Wan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, Y.; et al. Photoluminescence Mechanism in Graphene Quantum Dots: Quantum Confinement Effect and Surface/Edge State. Nano Today 2017, 13, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayiania, M.; Smith, M.; Hensley, A.J.; Scudiero, L.; McEwen, J.-S.; Garcia-Perez, M. Deconvoluting the XPS Spectra for Nitrogen-Doped Chars: An Analysis from First Principles. Carbon 2020, 162, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Qiao, L.; Zhu, Z.; Ran, X.; Kuang, Y.; Chi, Z.; et al. Highly Enhanced Photoluminescence and Suppressed Blinking of N-Doped Carbon Dots by Targeted Passivation of Amine Group for Mechanistic Insights and Vis-NIR Excitation Bioimaging Application. Carbon 2023, 213, 118212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.-H.; Liu, Z.-X.; Li, R.-S.; Zou, H.-Y.; Lin, M.; Liu, H.; et al. Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doping Carbon Dots with Different Photoluminescence Properties by Controlling the Surface States. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 6770–6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, U.; Rani, M.; Kaur, N. Fluorescent Detection of Melamine in Real Samples Using Green-Synthesized N-CQDs: A Sustainable Approach. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Quan, F.; Xu, Y.; Liu, M.; Cui, L.; Liu, J. Multifunctional N,S Co-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots with pH- and Thermo-Dependent Switchable Fluorescent Properties and Highly Selective Detection of Glutathione. Carbon 2016, 104, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, Z.; Raza, A.; Mehdi, M.; Arshad, A.; Deng, X.; Sun, S. Recent Advancements in Metal and Non-Metal Mixed-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots: Synthesis and Emerging Potential Applications. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dua, S.; Kumar, P.; Pani, B.; Kaur, A.; Khanna, M.; Bhatt, G. Stability of Carbon Quantum Dots: A Critical Review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 13845–13861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, B.I.; Hassan, A.I.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Ibrahim, A.E.; Saraya, R.E. Copper and Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots as Green Nano-Probes for Fluorimetric Determination of Delafloxacin; Characterization and Applications. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1327, 343175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, X.; et al. Non-Enzymatic Electrochemical Sensor for Accurately Detecting Norfloxacin Based on Porphyrin-Conjugated Microporous Polymers. Microchem. J. 2025, 115043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, N.N.M.Y.; Idris, A.; Abidin, Z.H.Z.; Tajuddin, H.A.; Abdullah, Z. White Light Employing Luminescent Engineered Large (Mega) Stokes Shift Molecules: A Review. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 13409–13445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, H.B.; Martins, C.S.; Prior, J.A. You Don’t Learn That in School: An Updated Practical Guide to Carbon Quantum Dots. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, K.J.; Zhou, Y.; Leblanc, R.M. Recent Development of Carbon Quantum Dots Regarding Their Optical Properties, Photoluminescence Mechanism, and Core Structure. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 4634–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauglitz, G. Analytical Evaluation of Sensor Measurements; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Ye, C.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Q. Mechanistic Insights into Photoluminescence Regulation in the Photoinduced Electron Transfer System of Carbon Dots and Benzoquinone Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 6313–6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, R. A Review on Fluorescent Molecular Probes for Hg²⁺ Ion Detection: Mechanisms, Strategies, and Future Directions. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202404525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Das, R.; Banerjee, P. Recent Endeavours in the Development of Organo Chromo-Fluorogenic Probes towards the Targeted Detection of the Toxic Industrial Pollutants Cu²⁺ and CN⁻: Recognition to Implementation in Sensory Device. Mater. Chem. Front. 2022, 6, 2561–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, F.; Yan, F.; Bai, Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; et al. The Quenching of the Fluorescence of Carbon Dots: A Review on Mechanisms and Applications. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 1899–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodha, S.R.; Merchant, J.G.; Pillai, A.J.; Gore, A.H.; Patil, P.O.; Nangare, S.N.; et al. Carbon Dot-Based Fluorescent Sensors for Pharmaceutical Detection: Current Innovations, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, S.; Zhou, L.; Luo, F.; Lou, Z.; Chen, Z.; et al. A Turn-On Fluorescence Sensor Based on Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Dots and Cu²⁺ for Sensitively and Selectively Sensing Glyphosate. Foods 2023, 12, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, W.; Zheng, L. Advancements in Intelligent Sensing Technologies for Food Safety Detection. Research 2025, 8, 0713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiq, K.; Sadia, I.; Abid, M.Z.; Waleed, M.Z.; Rauf, A.; Hussain, E. Scientific Insights into the Quantum Dots (QDs)-Based Electrochemical Sensors for State-of-the-Art Applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 7268–7313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahil; Jaryal, V.B.; Sharma, R.; Thakur, K.K.; Ataya, F.S.; Gupta, N.; et al. Facile One-Pot Synthesis of Fe₃O₄–MoS₂@MXene Nanocomposite as an Electrochemical Sensor for the Detection of Levofloxacin. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202405959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul, V.; Sampathkumar, N.; Kotteeswaran, S.; Arul, P.; Aljuwayid, A.M.; Habila, M.A.; et al. Biomass Derived Nitrogen Functionalized Carbon Nanodots for Nanomolar Determination of Levofloxacin in Pharmaceutical and Water Samples. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Abdiryim, T.; Jamal, R.; Liu, X.; Xue, C.; Xie, S.; et al. A Novel Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemical Sensor from Poly(3,4-Ethylene dioxy thiophene)/Chitosan for Selective and Sensitive Detection of Levofloxacin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toker, S.E.; Kızılçay, G.E.; Sagirli, O. Determination of Levofloxacin by HPLC with Fluorescence Detection in Human Breast Milk. Bioanalysis 2021, 13, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajala, O.A.; Akinnawo, S.O.; Bamisaye, A.; Adedipe, D.T.; Adesina, M.O.; Okon-Akan, O.A.; et al. Adsorptive Removal of Antibiotic Pollutants from Wastewater Using Biomass/Biochar-Based Adsorbents. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 4678–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Qiu, Q.; Dong, W. Visual Monitoring of Levofloxacin in Biofluids by Europium(III)-Functionalized Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 5631–5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huegen, B.L.; Doherty, J.L.; Smith, B.N.; Franklin, A.D. Role of Electrode Configuration and Morphology in Printed Prothrombin Time Sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 399, 134785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).