Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

2. METHODOLOGY

3. RESULT

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Physical Examination and Lipid Profile

3.3. KCNH2 Gene Expression

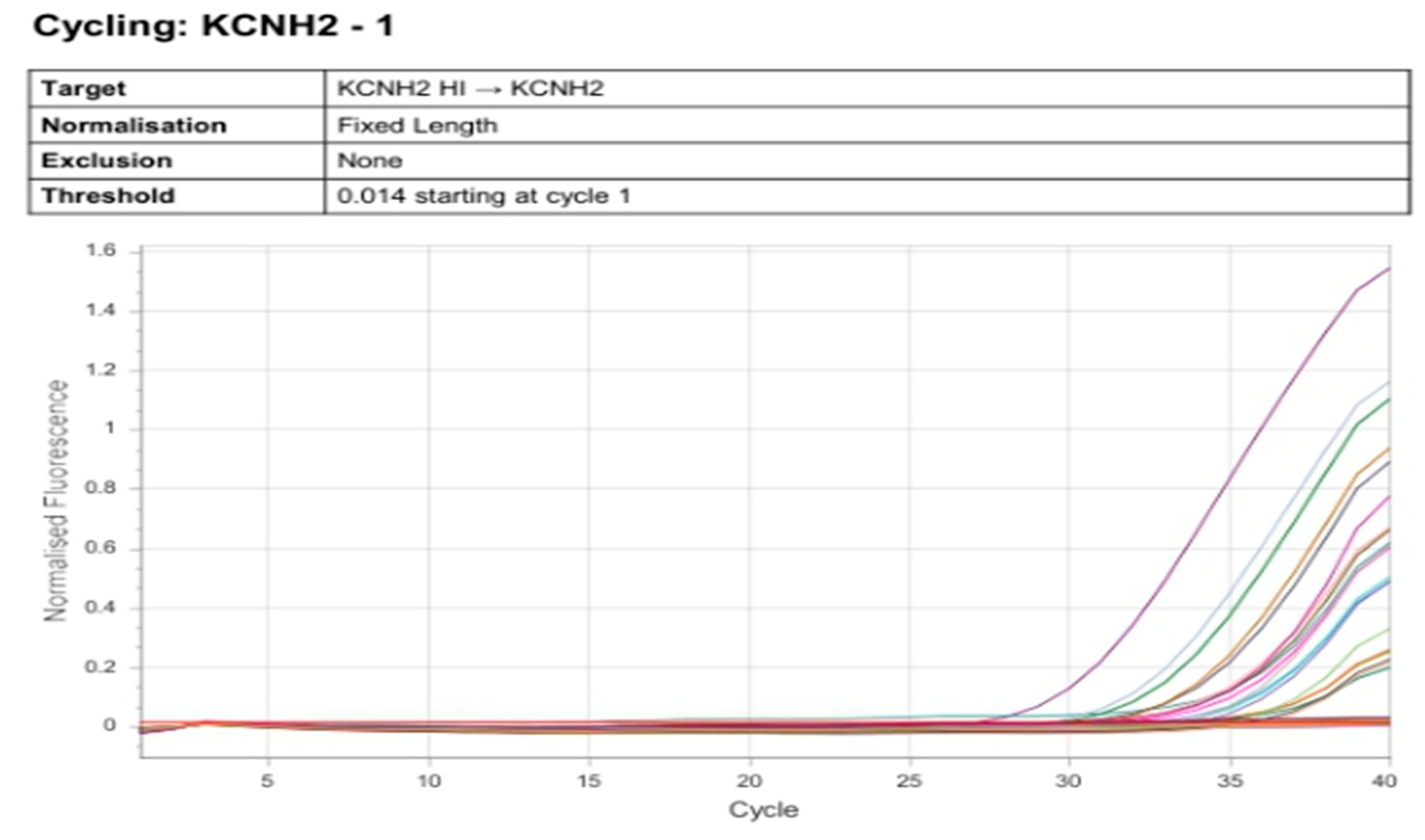

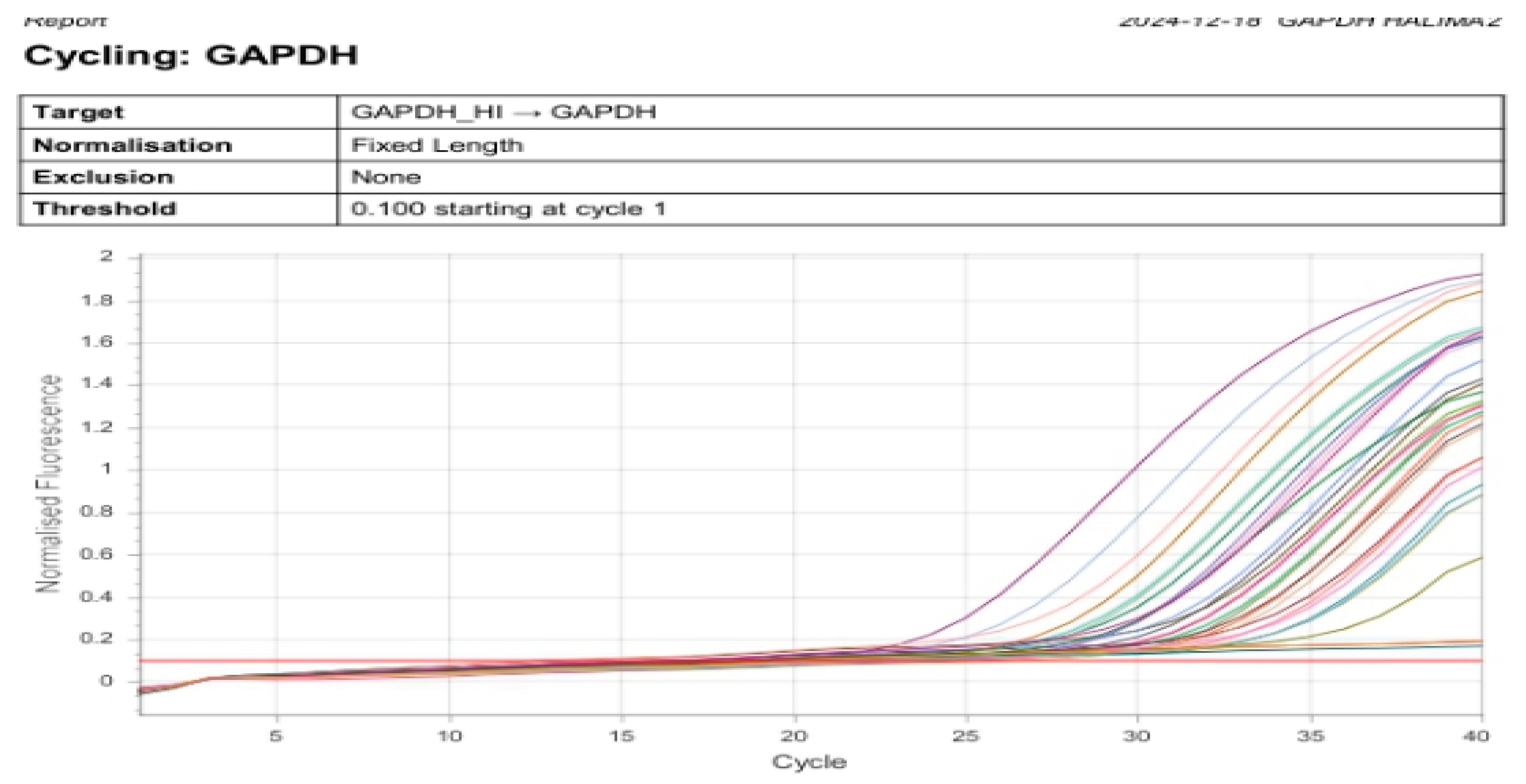

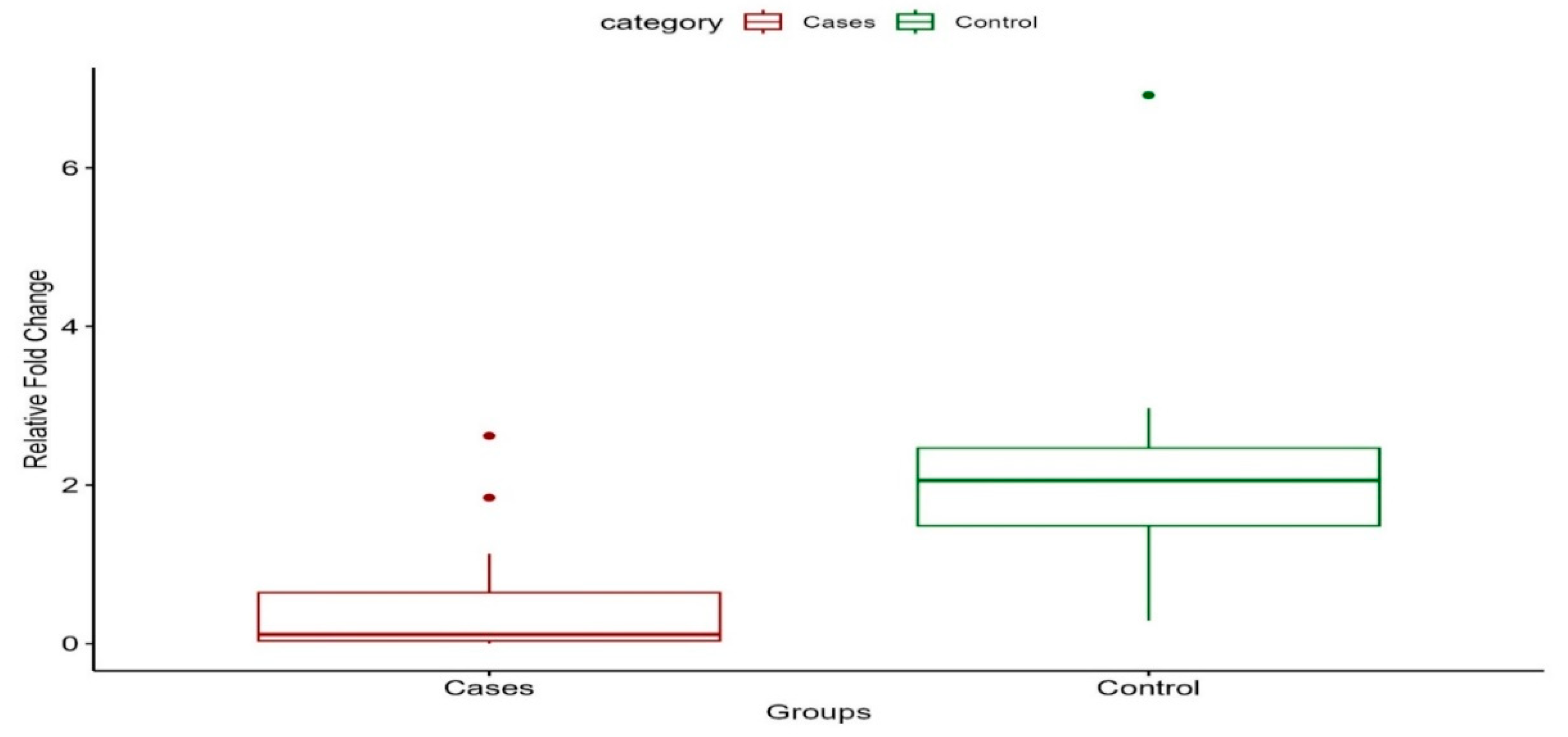

3.4. Comparison of Cardiovascular Parameters at Diagnosis and During Study

| Parameters | At Diagnosis | During study period | P-value |

| SBP (mmHg) | 134.29±43.916 | 111.29±27.585 | 0.131 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 86.57±30.588 | 76.57±19.104 | 0.337 |

| Heart-rate (b/min) | 131.43±14.363 | 72.71±14.092 | 0.000* |

| QTc-Interval (ms) | 346.14±48.368 | 500±13.000 | 0.000* |

| Paired sample T-test |

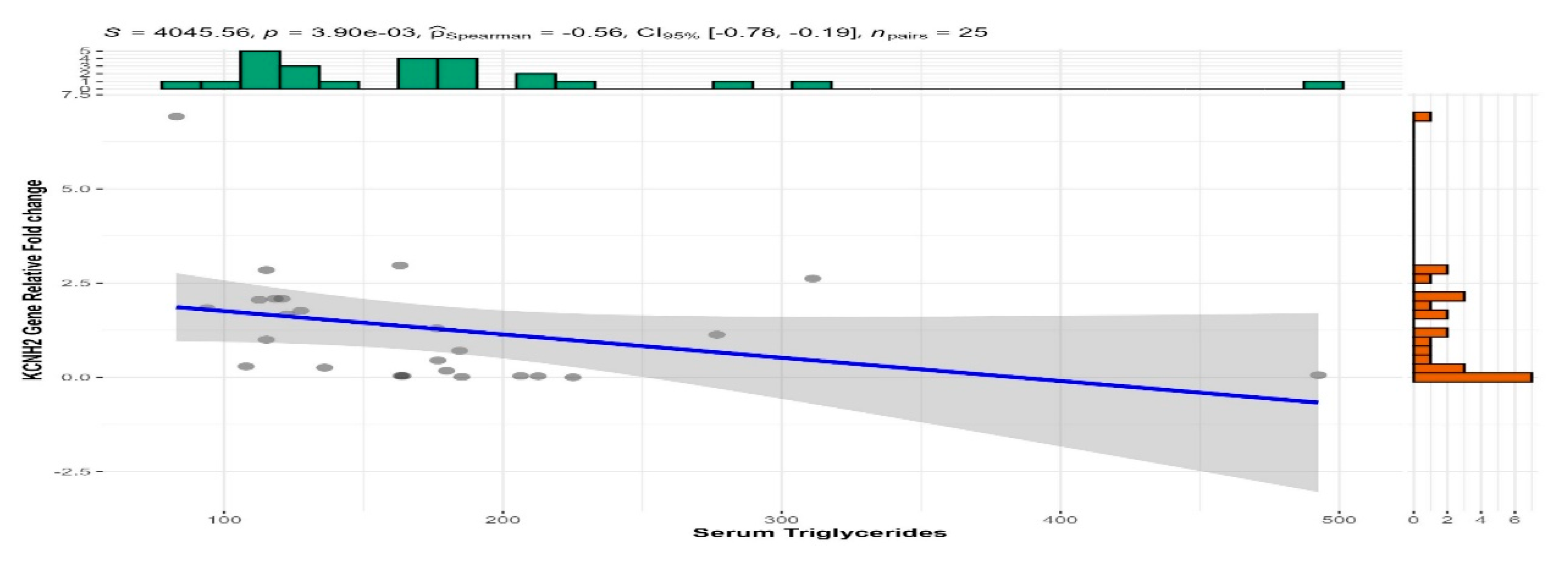

3.5. Correlation Analysis

| Clinical Parameter | Correlation with KCNH2 Expression (r) | p-value |

| Heart Rate (HR) | -0.270 | 0.559 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) | -0.539 | 0.212 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (DBP) | -0.378 | 0.620 |

| LDL Cholesterol | 0.003 | 0.990 |

| HDL Cholesterol | -0.200 | 0.323 |

| Triglycerides | -0.472 | 0.003* |

| Total Cholesterol | -0.066 | 0.755 |

| QTc Interval | -0.470 | 0.912 |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taizhanova D, Bazarova N, Zholdybayeva E, Kalimbetova A. Association of gene polymorphism at atrial fibrillation: A literature review. J Clin Med Kazakhstan. 2021 Jan 26;18(1):19–22.

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019 Mar 5;139(10): e56–528.

- Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, Singh D, Rienstra M, Benjamin EJ, et al. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014 Feb 25;129(8):837–47.

- Sliwa K, Carrington MJ, Klug E, Opie L, Lee G, Ball J, et al. Predisposing factors and incidence of newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation in an urban African community: insights from the Heart of Soweto Study. Heart Br Card Soc. 2010 Dec;96(23):1878–82.

- Ajayi EA, Adeyeye VO, Adeoti AO. Clinical and Echocardiographic Profile of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation in Nigeria. J Health Sci. 2016;6(3):37–42.

- Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 1;42(5):373–498.

- Nattel S, Heijman J, Zhou L, Dobrev D. Molecular Basis of Atrial Fibrillation Pathophysiology and Therapy: A Translational Perspective. Circ Res. 2020 Jun 19;127(1):51–72.

- Ellinor PT, Lunetta KL, Albert CM, Glazer NL, Ritchie MD, Smith AV, et al. Meta-analysis identifies six new susceptibility loci for atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2012 Apr 29;44(6):670–5.

- Andrade JG, Deyell MW, Verma A, Macle L, Champagne J, Leong-Sit P, et al. Association of Atrial Fibrillation Episode Duration With Arrhythmia Recurrence Following Ablation: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 2;3(7):e208748.

- Berkmen YM, Lande A. Chest roentgenography as a window to the diagnosis of Takayasu’s arteritis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975 Dec;125(4):842–6.

- Jagdesh Kumar, Afshan Nasim, Faraz Farooq Memon, Asad Ali Mahesar, Bilal Ahmad, Ahsan Ali Gaad. 48 hours holter monitoring in detecting occult atrial fibrillation in Adults. Med J South Punjab. 2024 Mar 22;5(01):47–52.

- van den Boogaard M, van Weerd JH, Bawazeer AC, Hooijkaas IB, van de Werken HJG, Tessadori F, et al. Identification and Characterization of a Transcribed Distal Enhancer Involved in Cardiac KCNH2 Regulation. Cell Rep. 2019 Sep 3;28(10):2704-2714.e5.

- Sinner MF, Pfeufer A, Akyol M, Beckmann BM, Hinterseer M, Wacker A, et al. The nonsynonymous coding IKr-channel variant KCNH2 -K897T is associated with atrial fibrillation: results from a systematic candidate gene-based analysis of KCNH2 (HERG). Eur Heart J. 2008 Apr;29(7):907–14.

- Gelman I, Sharma N, Mckeeman O, Lee P, Campagna N, Tomei N, et al. The ion channel basis of pharmacological effects of amiodarone on myocardial electrophysiological properties, a comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024 May 1;174:116513.

- Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, Larson MG, Beiser AS, McManus DD, et al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. The Lancet. 2015 Jul 11;386(9989):154–62.

- Akpa MR, Ofori S. Atrial fibrillation: An analysis of etiology and management pattern in a tertiary hospital in Port-harcourt, southern Nigeria. Res J Health Sci. 2015;3(4):303–10.

- Kerr CR, Humphries KH, Talajic M, Klein GJ, Connolly SJ, Green M, et al. Progression to chronic atrial fibrillation after the initial diagnosis of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: results from the Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2005 Mar;149(3):489–96.

- Mou L, Norby FL, Chen LY, O’Neal WT, Lewis TT, Loehr LR, et al. Lifetime Risk of Atrial Fibrillation by Race and Socioeconomic Status: ARIC Study (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018 Jul;11(7):e006350.

- Bai J, Lu Y, Lo A, Zhao J, Zhang H. PITX2 upregulation increases the risk of chronic atrial fibrillation in a dose-dependent manner by modulating IKs and ICaL -insights from human atrial modelling. Ann Transl Med. 2020 Mar;8(5):191.

- Mahmoodzadeh S, Dworatzek E. The Role of 17β-Estradiol and Estrogen Receptors in Regulation of Ca2+ Channels and Mitochondrial Function in Cardiomyocytes. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:310.

- Malaeb D, Hallit S, Dia N, Cherri S, Maatouk I, Nawas G, et al. Effects of sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors on stroke development in Lebanese patients with atrial fibrillation: a cross-sectional study. F1000Research. 2021;10:793.

- Magnussen C, Niiranen TJ, Ojeda FM, Gianfagna F, Blankenberg S, Njølstad I, et al. Sex Differences and Similarities in Atrial Fibrillation Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Mortality in Community Cohorts: Results From the BiomarCaRE Consortium (Biomarker for Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Europe). Circulation. 2017 Oct 24;136(17):1588–97.

- Valkanova V, Ebmeier KP. Vascular risk factors and depression in later life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2013 Mar 1;73(5):406–13.

- Camm AJ, Lip GYH, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012 Nov;33(21):2719–47.

- Heijman J, voigt N, Nattel S, Dobrev D. Cellular and Molecular Electrophysiology of Atrial Fibrillation Initiation, Maintenance, and Progression | Circulation Research [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 28]. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302226.

- Varró A, Baczkó I. Cardiac ventricular repolarization reserve: a principle for understanding drug-related proarrhythmic risk. Br J Pharmacol. 2011 Sep;164(1):14–36.

- Zipes, D. P., & Jalife, J. (2017). Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside (7th ed.). Elsevier. - Google Search [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.google.com/search?q=Zipes%2C+D.+P.%2C+%26+Jalife%2C+J.+(2017).+Cardiac+Electrophysiology%3A+From+Cell+to+Bedside+(7th+ed.).+Elsevier.&oq=Zipes%2C+D.+P.%2C+%26+Jalife%2C+J.+(2017).+Cardiac+Electrophysiology%3A+From+Cell+to+Bedside+(7th+ed.).+Elsevier.&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIGCAEQRRhA0gEIMzU0ajBqMTWoAgCwAgA&sourceid=chrome&i.e.,=UTF-8#vhid=zephyr:0&vssid=atritem-https://shop.elsevier.com/books/cardiac-electrophysiology-from-cell-to-bedside/zipes/978-0-323-44733-1.

- Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, Cha SS, Gersh BJ, Seward JB, et al. Mortality trends in patients diagnosed with first atrial fibrillation: a 21-year community-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007 Mar 6;49(9):986–92.

- Sinner MF, Pfeufer A, Akyol M, Beckmann BM, Hinterseer M, Wacker A, et al. The nonsynonymous coding IKr-channel variant KCNH2 -K897T is associated with atrial fibrillation: results from a systematic candidate gene-based analysis of KCNH2 (HERG). Eur Heart J. 2008 Apr;29(7):907–14.

- Li ZZ, Du X, Guo X yuan, Tang R bo, Jiang C, Liu N, et al. Association Between Blood Lipid Profiles and Atrial Fibrillation: A Case‒Control Study. Med Sci Monit Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2018 Jun 9;24:3903–8.

| Characteristics |

Cases (N = 14) |

Control (N = 11) |

p-value |

| Age, Mean (+SD) | 53.4 (+16.87) | 43.8 (+15.99) | 0.0821 |

| Sex, n (%) | >0.92 | ||

| Male | 8.0 (57.14%) | 6.0 (54.55%) | |

| Female | 6.0 (42.86%) | 5.0 (45.45%) | |

| Marital Status, n (%) | 0.0652 | ||

| Unmarried | 4.0(28.57%) | 3.0 (35.00%) | |

| Married | 10.0(71.43%) | 8.0 (65.00%) | |

| Class of Antiarrhythmic drugs, n (%) | |||

| Class 2 and 3 | 2.0 (28.57%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | |

| Class 2 and 3 + Digoxin | 1.0 (14.29%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | |

| Class 3 | 2.0 (28.57%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | |

| Class 3 + Digoxin | 1.0 (14.29%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | |

| Digoxin | 1.0 (14.29%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | |

| (Missing) | 7 | ||

| Family History of Atrial Fibrillation, n (%) | 0.0202 | ||

| No | 8.0 (57.14%) | 11.0 (100.00%) | |

| Yes | 6.0 (42.86%) | 0.0 (0.00%) | |

| Family History of Heart Failure, n (%) | 0.112 | ||

| No | 10.0 (71.43%) | 11.0 (100.00%) | |

| Yes | 4.0 (28.57%) | 0.0 (0.00%) | |

| Family History of Sudden Death, n (%) | >0.92 | ||

| No | 13.0 (92.86%) | 11.0 (100.00%) | |

| Yes | 1.0 (7.14%) | 0.0 (0.00%) | |

| 1T test; 2McNemar’s Exact Test | |||

| Characteristic |

Cases (N = 14) |

Control (N = 11) |

p-value |

| Pulse Rhythm, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Irregular | 14.00 (100.00%) | 0.00 (0.00%) | |

| Regular | 0.00 (0.00%) | 11.00 (100.00%) | |

| Total Cholesterol, Mean (±SD) | 207.48 (±59.00) | 153.73 (±34.58) | 0.0052 |

| Triglycerides, Median (Q1-Q3) | 184.88 (164.17-225.14) | 118.30 (112.57-127.50) | 0.0081 |

| HDL Cholesterol, Mean (±SD) | 56.20 (±13.48) | 51.50 (±9.07) | >0.92 |

| LDL Cholesterol, Mean (±SD) | 109.88 (±45.65) | 74.91 (±29.19) | 0.0292 |

| 1Wilcoxon signed rank test; 2T test; 3McNemar’s Exact Test | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).