Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Individuals

2.2. Genetic Assay in Study Participants

2.3. Recombination of Gene-Expressing Vectors

2.4. Cellular Transfection with Multiple Expression Vectors and Dual-Luciferase Activity Measurement

2.5. Statistical Assessment

3. Results

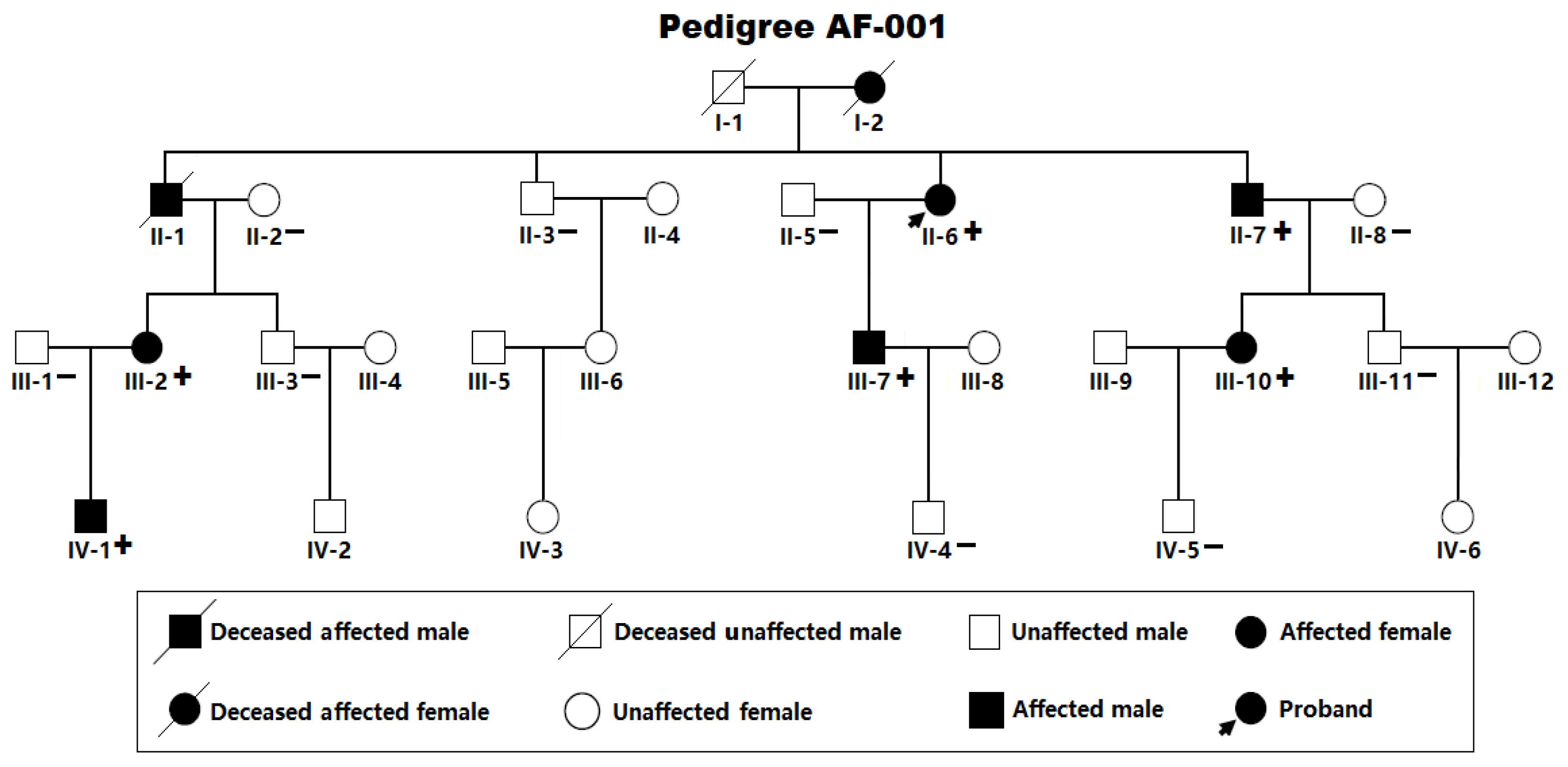

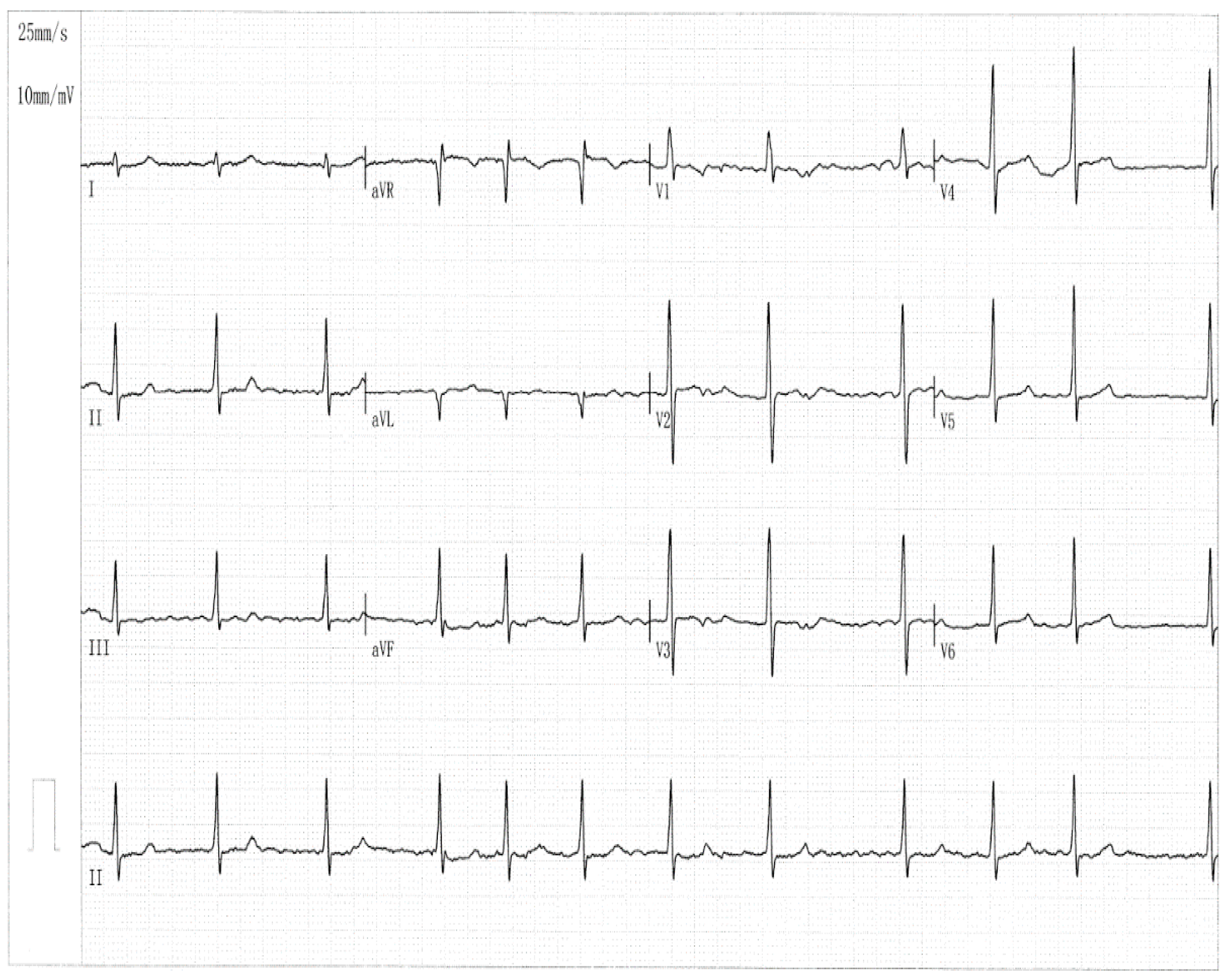

3.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristical Profiles of the Pedigree Members and Other Study Subjects

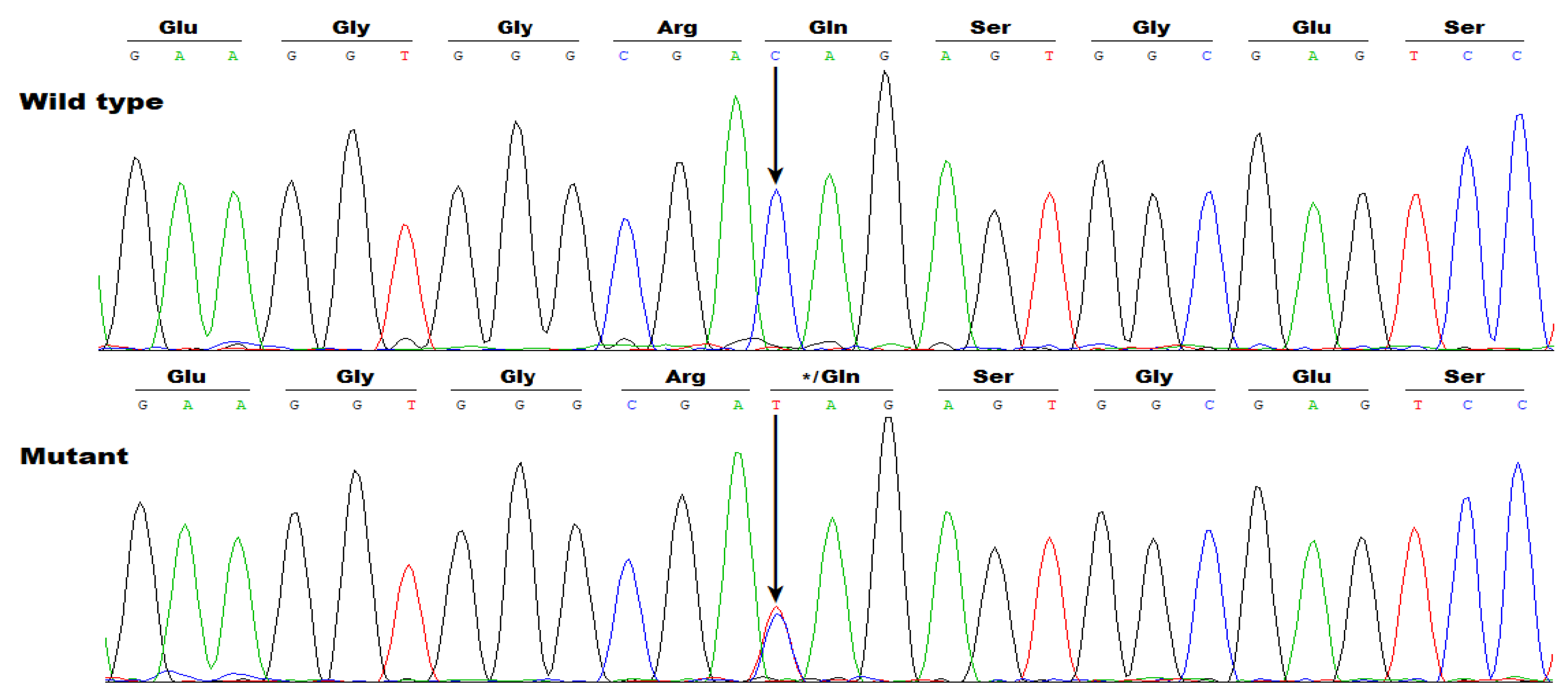

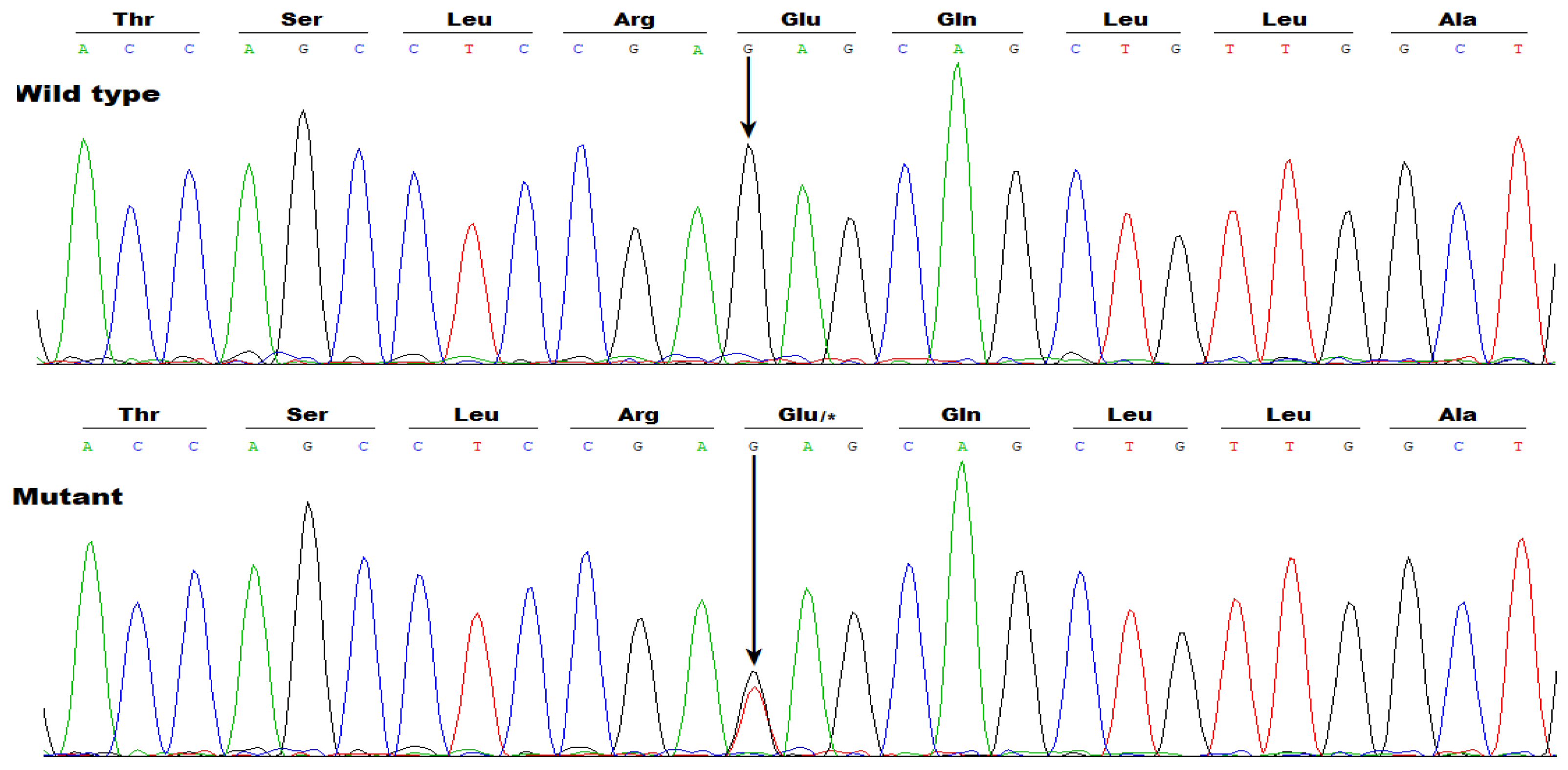

3.2. Identificaton of Two Novel SOX5 Variations Contributing to AF

3.3. Functional failure of Gln119*- or Glu214*-Mutant SOX5 to Transactivate GJA1

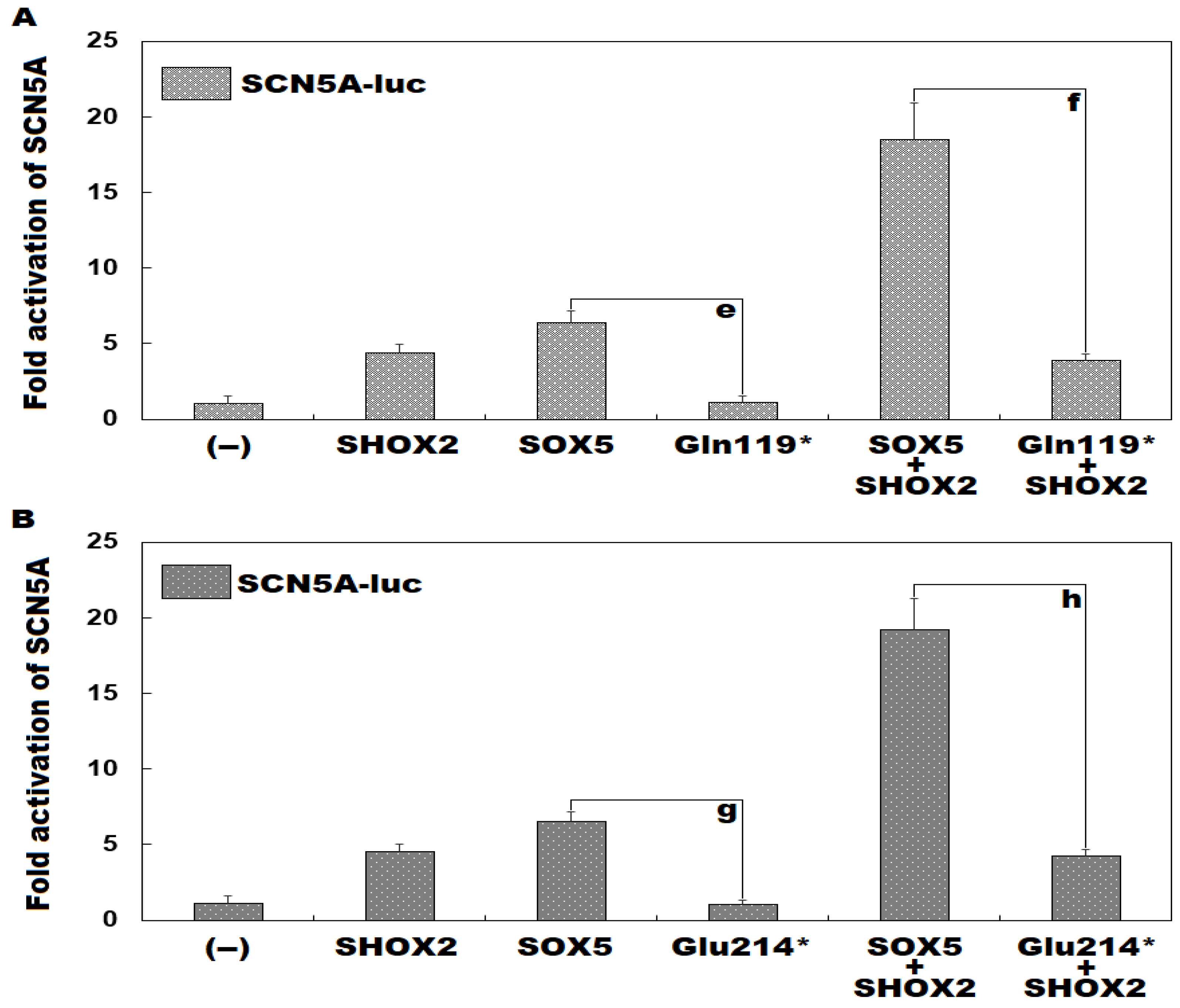

3.4. Inability of Gln119*-or Glu214*-Mutant SOX5 to Induce Transactivation of SCN5A singly or Synergistically with SHOX2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, H.; Lu, L.; Xiong, H.; Fan, C.; Fan, L.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, H. A Novel Approach to Dual Feature Selection of Atrial Fibrillation Based on HC-MFS. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joglar, J.A.; Chung, M.K.; Armbruster, A.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Chyou, J.Y.; Cronin, E.M.; Deswal, A.; Eckhardt, L.L.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Gopinathannair, R.; et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024, 149, e1–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- January, C.T.; Wann, L.S.; Alpert, J.S.; Calkins, H.; Cigarroa, J.E.; Cleveland, J.C., Jr.; Conti, J.B.; Ellinor, P.T.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Field, M.E.; et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014, 130, e199–e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wu, X.Y.; Long, D.Y.; Jiang, C.X.; Sang, C.H.; Tang, R.B.; Li, S.N.; Wang, W.; Guo, X.Y.; Ning, M.; et al. Asymptomatic atrial fibrillation among hospitalized patients: clinical correlates and in-hospital outcomes in Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China-trial Fibrillation. Europace 2023, 25, euad272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, K.; Reissenberger, P.; Piper, D.; Koenig, N.; Hoelz, B.; Schlaepfer, J.; Gysler, S.; McCullough, H.; Ramin-Wright, S.; Gabathuler, A.L.; et al. Fully Automated Photoplethysmography-Based Wearable Atrial Fibrillation Screening in a Hospital Setting. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turakhia, M.P.; Guo, J.D.; Keshishian, A.; Delinger, R.; Sun, X.; Ferri, M.; Russ, C.; Cato, M.; Yuce, H.; Hlavacek, P. Contemporary prevalence estimates of undiagnosed and diagnosed atrial fibrillation in the United States. Clin. Cardiol. 2023, 46, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.G.; Deyell, M.W.; Bennett, R.; Macle, L. Assessment and management of asymptomatic atrial fibrillation. Heart 2024, 110, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsmans, M.; Schloss, M.J.; Lee, I.H.; Bapat, A.; Iwamoto, Y.; Vinegoni, C.; Paccalet, A.; Yamazoe, M.; Grune, J.; Pabel, S.; et al. Recruited macrophages elicit atrial fibrillation. Science 2023, 381, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, H.J.; Lin, L.C.; Yu, A.L.; Liu, Y.B.; Lin, L.Y.; Huang, H.C.; Ho, L.T.; Lai, L.P.; Chen, W.J.; Ho, Y.L.; et al. Predicting impaired cardiopulmonary exercise capacity in patients with atrial fibrillation using a simple echocardiographic marker. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisenbayeva, A.; Bekbossynova, M.; Bakytzhanuly, A.; Aleushinova, U.; Bekmetova, F.; Chinybayeva, A.; Abdrakhmanov, A.; Beyembetova, A. Improvements in Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test Results in Atrial Fibrillation Patients After Radiofrequency Ablation in Kazakhstan. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Witassek, F.; Aebersold, H.; Aeschbacher, S.; Ammann, P.; Beer, J.H.; Blozik, E.; Bonati, L.H.; Cattaneo, M.; Coslovsky, M.; Felder, S.; et al. Longitudinal Changes in Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e031872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeitler, E.P.; Li, Y.; Silverstein, A.P.; Russo, A.M.; Poole, J.E.; Daniels, M.R.; Al-Khalidi, H.R.; Lee, K.L.; Bahnson, T.D.; Anstrom, K.J.; et al. Effects of Ablation Versus Drug Therapy on Quality of Life by Sex in Atrial Fibrillation: Results From the CABANA Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e027871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Särnholm, J.; Skúladóttir, H.; Rück, C.; Axelsson, E.; Bonnert, M.; Bragesjö, M.; Venkateshvaran, A.; Ólafsdóttir, E.; Pedersen, S.S.; Ljótsson, B.; et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Improves Quality of Life in Patients With Symptomatic Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Cha, M.J.; Nam, G.B.; Choi, K.J.; Sun, B.J.; Kim, D.H.; Song, J.M.; Kang, D.H.; Song, J.K.; Cho, M.S. Incidence and predictors of left atrial thrombus in patients with atrial fibrillation under anticoagulation therapy. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2024, 113, 1242–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Inoue, K.; Tanaka, N.; Tanaka, K.; Hirao, Y.; Iwakura, K.; Egami, Y.; Masuda, M.; Watanabe, T.; Minamiguchi, H.; et al. Impact of left atrial appendage flow velocity on thrombus resolution and clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and silent left atrial thrombi: insights from the LAT study. Europace 2024, 26, euae120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, F.; Guida, P.; Vitulano, N.; Quadrini, F.; Di Monaco, A.; Patti, G.; Grimaldi, M. Atrial Thrombosis Prevalence Before Cardioversion or Catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Direct Oral Anticoagulants Versus Vitamin K Antagonists. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 218, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Lutnik, M.; Cacioppo, F.; Lindmayr, T.; Schuetz, N.; Tumnitz, E.; Friedl, L.; Boegl, M.; Schnaubelt, S.; Domanovits, H.; et al. Computed Tomography to Exclude Cardiac Thrombus in Atrial Fibrillation-An 11-Year Experience from an Academic Emergency Department. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurol, M.E.; Wright, C.B.; Janis, S.; Smith, E.E.; Gokcal, E.; Reddy, V.Y.; Merino, J.G.; Hsu, J.C. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation: Our Current Failures and Required Research. Stroke 2024, 55, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, T.F.; Potpara, T.S.; Lip, G.Y.H. Atrial fibrillation: stroke prevention. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 37, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, B.; Bhaskar, S.M.M. Evaluating Machine Learning Models for Stroke Prognosis and Prediction in Atrial Fibrillation Patients: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh, S.; Hill, A.; Irving, G.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Abdul-Rahim, A.H. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: State-of-the-art and future directions. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certo Pereira, J.; Lima, M.R.; Moscoso Costa, F.; Gomes, D.A.; Maltês, S.; Cunha, G.; Dores, H.; Adragão, P. Stroke in Athletes with Atrial Fibrillation: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2024, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Proietti, M.; Potpara, T.; Mansour, M.; Savelieva, I.; Tse, H.F.; Goette, A.; Camm, A.J.; Blomstrom-Lundqvist, C.; Gupta, D.; et al. Atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention: 25 years of research at EP Europace journal. Europace 2023, 25, euad226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, S.; Conen, D. Mechanisms and Clinical Manifestations of Cognitive Decline in Atrial Fibrillation Patients: Potential Implications for Preventing Dementia. Can. J. Cardiol. 2023, 39, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, N.; Zelnick, L.R.; An, J.; Harrison, T.N.; Lee, M.S.; Singer, D.E.; Fan, D.; Go, A.S. Incident Atrial Fibrillation and Risk of Dementia in a Diverse, Community-Based Population. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e028290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogelschatz, B.; Zenger, B.; Steinberg, B.A.; Ranjan, R.; Jared Bunch, T. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of early-onset dementia and cognitive decline: An updated review. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 34, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venier, S.; Vaxelaire, N.; Jacon, P.; Carabelli, A.; Desbiolles, A.; Garban, F.; Defaye, P. Severe acute kidney injury related to haemolysis after pulsed field ablation for atrial fibrillation. Europace 2023, 26, euad371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, F.; Knecht, S.; Isenegger, C.; Arnet, R.; Krisai, P.; Völlmin, G.; du Fay de Lavallaz, J.; Spreen, D.; Osswald, S.; Sticherling, C.; et al. Acute kidney injury after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: Comparison between different energy sources. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 1248–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odutayo, A.; Wong, C.X.; Hsiao, A.J.; Hopewell, S.; Altman, D.G.; Emdin, C.A. Atrial fibrillation and risks of cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016, 354, i4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, J.; Isaacs, A.; Zeemering, S.; Kawczynski, M.; Maesen, B.; Maessen, J.; Bidar, E.; Boukens, B.; Hermans, B.; van Hunnik, A.; et al. Heart Failure, Female Sex, and Atrial Fibrillation Are the Main Drivers of Human Atrial Cardiomyopathy: Results From the CATCH ME Consortium. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e031220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, M.; Matsuda, Y.; Uematsu, H.; Sugino, A.; Ooka, H.; Kudo, S.; Fujii, S.; Asai, M.; Okamoto, S.; Ishihara, T.; et al. Prognostic impact of atrial cardiomyopathy: Long-term follow-up of patients with and without low-voltage areas following atrial fibrillation ablation. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakasis, P.; Vlachakis, P.K.; Theofilis, P.; Ktenopoulos, N.; Patoulias, D.; Fyntanidou, B.; Antoniadis, A.P.; Fragakis, N. Atrial Cardiomyopathy in Atrial Fibrillation: A Multimodal Diagnostic Framework. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakasis, P.; Theofilis, P.; Vlachakis, P.K.; Ktenopoulos, N.; Patoulias, D.; Antoniadis, A.P.; Fragakis, N. Atrial Cardiomyopathy in Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanistic Pathways and Emerging Treatment Concepts. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederiksen, T.C.; Dahm, C.C.; Preis, S.R.; Lin, H.; Trinquart, L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Kornej, J. The bidirectional association between atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, B.; Varlot, J.; Humbertjean, L.; Sellal, J.M.; Pace, N.; Hammache, N.; Fay, R.; Eggenspieler, F.; Metzdorf, P.A.; Camenzind, E. Coronary Embolism Among Patients With ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Atrial Fibrillation: An Underrecognized But Deadly Association. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e032199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, T.C.; Benjamin, E.J.; Trinquart, L.; Lin, H.; Dahm, C.C.; Christiansen, M.K.; Jensen, H.K.; Preis, S.R.; Kornej, J. Bidirectional Association Between Atrial Fibrillation and Myocardial Infarction, and Relation to Mortality in the Framingham Heart Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e032226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, E.; Kiviniemi, T.; Halminen, O.; Lehtonen, O.; Teppo, K.; Haukka, J.; Mustonen, P.; Putaala, J.; Linna, M.; Hartikainen, J.; et al. Temporal Relation Between Myocardial Infarction and New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation: Results from a Nationwide Registry Study. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 211, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, P.M.; Jarolim, P.; Palazzolo, M.G.; Bellavia, A.; Antman, E.M.; Eikelboom, J.; Granger, C.B.; Harrington, J.; Healey, J.S.; Hijazi, Z.; et al. Heart Failure Risk Assessment Using Biomarkers in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Analysis From COMBINE-AF. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 84, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Jiang, J.; Fan, F.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, N.; Hao, Y.; et al. Prevalence, Characteristics, and Treatment Strategy of Different Types of Heart Failure in Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e033941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, R.; Yang, M.; Li, W.; Zhang, P.P.; Mo, B.F.; Wang, Q.S.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.G. Combined Radiofrequency Ablation and Left Atrial Appendage Closure in Atrial Fibrillation and Systolic Heart Failure. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergonti, M.; Ascione, C.; Marcon, L.; Pambrun, T.; Della Rocca, D.G.; Ferrero, T.G.; Pannone, L.; Kühne, M.; Compagnucci, P.; Bonomi, A.; et al. Left ventricular functional recovery after atrial fibrillation catheter ablation in heart failure: a prediction model. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3327–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.G.; Choi, Y.Y.; Han, K.D.; Min, K.; Choi, H.Y.; Shim, J.; Choi, J.I.; Kim, Y.H. Atrial fibrillation is associated with increased risk of lethal ventricular arrhythmias. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, A.M.; Bisson, A.; Bentounes, S.A.; Bodin, A.; Herbert, J.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Fauchier, L. Ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac arrest in atrial fibrillation patients with pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 115, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhoff, H.; Järnbert-Petersson, H.; Darpo, B.; Tornvall, P.; Frick, M. Mortality and ventricular arrhythmias in patients on d,l-sotalol for rhythm control of atrial fibrillation: A nationwide cohort study. Heart Rhythm 2023, 20, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, M.; Bertini, M.; Vitali, F.; Turakhia, M.; Boriani, G. Heart Failure-Related Death in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation in the United States, 1999 to 2020. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e033897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhof P, Haas S, Amarenco P, Turpie AGG, Bach M, Lambelet M, Hess S, Camm AJ. Causes of death in patients with atrial fibrillation anticoagulated with rivaroxaban: a pooled analysis of XANTUS. Europace 2024, 26, euae183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Nadarajah, R.; Nakao, Y.M.; Nakao, K.; Wilkinson, C.; Cowan, J.C.; Camm, A.J.; Gale, C.P. Temporal trends of cause-specific mortality after diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 4422–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, M.J.; Zhou, J.; Sale, A.J.; Longacre, C.; Zeitler, E.P.; Andrade, J.; Mittal, S.; Piccini, J.P. Early mortality after inpatient versus outpatient catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2023, 20, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccini, J.P.; Hammill, B.G.; Sinner, M.F.; Hernandez, A.F.; Walkey, A.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Curtis, L.H.; Heckbert, S.R. Clinical course of atrial fibrillation in older adults: the importance of cardiovascular events beyond stroke. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh A, Iglesias M, Khanna R, Beaulieu T. Healthcare utilization and costs associated with a diagnosis of incident atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm O2 2022, 3, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peigh, G.; Zhou, J.; Rosemas, S.C.; Roberts, A.I.; Longacre, C.; Nayak, T.; Schwab, G.; Soderlund, D.; Passman, R.S. Impact of Atrial Fibrillation Burden on Health Care Costs and Utilization. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 10, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, L.; Denman, R.; Hay, K.; Kaambwa, B.; Ganesan, A.; Ranasinghe, I. Excess Bed Days and Hospitalization Costs Associated With 30-Day Complications Following Catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e030236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buja, A.; Rebba, V.; Montecchio, L.; Renzo, G.; Baldo, V.; Cocchio, S.; Ferri, N.; Migliore, F.; Zorzi, A.; Collins, B.; et al. The Cost of Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review. Value Health 2024, 27, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A.D.; Middeldorp, M.E.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Albert, C.M.; Sanders, P. Epidemiology and modifiable risk factors for atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Cai, L.; Yu, B.; Wang, Y.; Tan, X.; Wan, H.; Xu, D.; Zhang, J.; Qi, L.; et al. Non-traditional risk factors for atrial fibrillation: epidemiology, mechanisms, and strategies. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 784–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kany, S.; Jurgens, S.J.; Rämö, J.T.; Christophersen, I.E.; Rienstra, M.; Chung, M.K.; Olesen, M.S.; Ackerman, M.J.; McNally, E.M.; Semsarian, C.; et al. Genetic testing in early-onset atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3111–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinciguerra, M.; Dobrev, D.; Nattel, S. Atrial fibrillation: pathophysiology, genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 37, 100785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owais, A.; Barney, M.; Ly, O.T.; Brown, G.; Chen, H.; Sridhar, A.; Pavel, A.; Khetani, S.R.; Darbar, D. Genetics and Pharmacogenetics of Atrial Fibrillation: A Mechanistic Perspective. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2024, 9, 918–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Viet, N.N.; Gigante, B.; Lind, V.; Hammar, N.; Modig, K. Elevated Uric Acid Is Associated With New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation: Results From the Swedish AMORIS Cohort. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e027089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Liu, C.; Lu, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, N.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Li, Y. Identification and Verification of Biomarkers and Immune Infiltration in Obesity-Related Atrial Fibrillation. Biology 2023, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.; Choi, E.Y. Multimodality Imaging in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Atrial Fibrillation. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.M.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, Y.L.; Kang, M.; Kang, E.; Ryu, H.; Kim, Y.; Han, S.S.; Ahn, C.; Oh, K.H. Association of Chronic Kidney Disease With Atrial Fibrillation in the General Adult Population: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e028496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, M.; Oliveira, M.; Laranjo, S.; Rocha, I. Linking Sleep Disorders to Atrial Fibrillation: Pathways, Risks, and Treatment Implications. Biology 2024, 13, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Zotto, B.; Barbieri, L.; Tumminello, G.; Saviano, M.; ’ Gentile, D.; Lucreziotti, S.; Frattini, L.; Tarricone, D.; Carugo, S. New Onset Atrial Fibrillation in STEMI Patients: Main Prognostic Factors and Clinical Outcome. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, H.S.; Hanley, A.; Hill, M.C.; Xiao, L.; Ye, J.; Bapat, A.; Ronzier, E.; Hall, A.W.; Hucker, W.J.; Clauss, S.; et al. Loss of the Atrial Fibrillation-Related Gene, Zfhx3, Results in Atrial Dilation and Arrhythmias. Circ. Res. 2023, 133, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, M.; Sommerfeld, L.C.; O'Shea, C.; Broadway-Stringer, S.; Andaleeb, S.; Reyat, J.S.; Kabir, S.N.; Stastny, D.; Malinova, A.; Delbue, D.; et al. Familial atrial fibrillation mutation M1875T-SCN5A increases early sodium current and dampens the effect of flecainide. Europace 2023, 25, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, Y.J.; Guo, X.J.; Wu, S.H.; Jiang, W.F.; Zhang, D.L.; Wang, K.W.; Li, L.; Sun, Y.M.; Xu, Y.J.; et al. Discovery of TBX20 as a Novel Gene Underlying Atrial Fibrillation. Biology 2023, 12, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalazan, B.; Freeth, E.; Mohajeri, A.; Ramanathan, K.; Bennett, M.; Walia, J.; Halperin, L.; Roston, T.; Lazarte, J.; Hegele, R.A.; et al. Genetic testing in monogenic early-onset atrial fibrillation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 31, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vad, O.B.; Angeli, E.; Liss, M.; Ahlberg, G.; Andreasen, L.; Christophersen, I.E.; Hansen, C.C.; Møller, S.; Hellsten, Y.; Haunsoe, S.; et al. Loss of Cardiac Splicing Regulator RBM20 Is Associated With Early-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2023, 9, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virk, Z.M.; El-Harasis, M.A.; Yoneda, Z.T.; Anderson, K.C.; Sun, L.; Quintana, J.A.; Murphy, B.S.; Laws, J.L.; Davogustto, G.E.; O'Neill, M.J.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Pathogenic TTN Variants. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 10, 2445–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Manuel, A.I.; Macías, Á.; Cruz, F.M.; Gutiérrez, L.K.; Martínez, F.; González-Guerra, A.; Martínez Carrascoso, I.; Bermúdez-Jimenez, F.J.; Sánchez-Pérez, P.; Vera-Pedrosa, M.L.; et al. The Kir2.1E299V mutation increases atrial fibrillation vulnerability while protecting the ventricles against arrhythmias in a mouse model of short QT syndrome type 3. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.F.; Sun, Y.M.; Qiu, X.B.; Wu, S.H.; Ding, Y.Y.; Li, N.; Yang, C.X.; Xu, Y.J.; Jiang, T.B.; Yang, Y.Q. Identification and Functional Investigation of SOX4 as a Novel Gene Underpinning Familial Atrial Fibrillation. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, L.L.; Liu, Z.B.; Chen, C.; Ren, X.; Luo, A.T.; Ma, J.H.; Antzelevitch, C.; Barajas-Martínez, H.; Hu, D. Underlying mechanism of atrial fibrillation-associated Nppa-I137T mutation and cardiac effect of potential drug therapy. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.W.; Chen, J.J.; Wang, C.H.; Chang, S.N.; Chiu, F.C.; Huang, P.S.; Chua, S.K.; Chuang, E.Y.; Tsai, C.T. Identification of a new genetic locus associated with atrial fibrillation in the Taiwanese population by genome-wide and transcriptome-wide association studies. Europace 2025, 27, euaf042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li YJ, Wang J, Ye WG, Liu XY, Li L, Qiu XB, Chen H, Xu YJ, Yang YQ, Bai D, et al. Discovery of GJC1 (Cx45) as a New Gene Underlying Congenital Heart Disease and Arrhythmias. Biology 2023, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoi, M.; Katsumata, Y.; Kunimoto, H.; Inami, T.; Miya, F.; Anzai, A.; Goto, S.; Miura, A.; Shinya, Y.; Hiraide, T.; et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis in Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e035498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, N.; Krasic, S.; Maric, N.; Gasic, V.; Krstic, J.; Cvetkovic, D.; Miljkovic, V.; Zec, B.; Maver, A.; Vukomanovic, V.; et al. Noonan Syndrome: Relation of Genotype to Cardiovascular Phenotype-A Multi-Center Retrospective Study. Genes 2024, 15, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.Y.; Yang, C.X.; Zhou, H.M.; Li, Y.J.; Qiu, X.B.; Huang, R.T.; Cen, S.S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.J.; et al. Discovery and functional investigation of BMP4 as a new causative gene for human congenital heart disease. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 2034–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.P.; Gu, J.N.; Yang, C.X.; Li, X.L.; Zou, S.; Bian, Y.Z.; Xu, Y.J.; Yang, Y.Q. Discovery of ETS1 as a New Gene Predisposing to Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, Z.S.; Wang, X.H.; Xu, Y.J.; Qiao, Q.; Li, X.M.; Di, R.M.; Guo, X.J.; Li, R.G.; Zhang, M.; et al. A SHOX2 loss-of-function mutation underlying familial atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 1564–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefebvre, V.; Li, P.; de Crombrugghe, B. A new long form of Sox5 (L-Sox5), Sox6 and Sox9 are coexpressed in chondrogenesis and cooperatively activate the type II collagen gene. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 5718–5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Lefebvre, V. L-Sox5 and Sox6 drive expression of the Aggrecan gene in cartilage by Securing binding of Sox9 to a far-upstream enhancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 4999–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, M.; Lu, Y.; Li, J.; Gu, J.; Ji, Y.; Shao, Y.; Kong, X.; Sun, W. Interaction of SOX5 with SOX9 promotes warfarin-induced aortic valve interstitial cell calcification by repressing transcriptional activation of LRP6. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2022, 162, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xie, H.; Xiao, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S. Functional characterization of SOX5 variant causing Lamb-Shaffer syndrome and literature review of variants in the SOX5 gene. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.S. SOX4: The unappreciated oncogene. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 67, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grippa, M.; Graziano, C. Landscape of Constitutional SOX4 Variation in Human Disorders. Genes 2024, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truebestein, L.; Leonard, T.A. Coiled-coils: the long and short of it. BioEssays 2016, 38, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, M.O.; Olson, S.; Wei, X.; Garrett, S.C.; Osman, A.; Bolisetty, M.; Plocik, A.; Celniker, S.E.; Graveley, B.R. Genome-wide identification of zero nucleotide recursive splicing in Drosophila. Nature 2015, 521, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Oksvold, P.; Kampf, C.; Djureinovic, D.; Odeberg, J.; Habuka, M.; Tahmasebpoor, S.; Danielsson, A.; Edlund, K.; et al. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, L.; Morey, R.; Palpant, N.J.; Wang, P.L.; Afari, N.; Jiang, C.; Parast, M.M.; Murry, C.E.; Laurent, L.C.; Salzman, J. Statistically based splicing detection reveals neural enrichment and tissue-specific induction of circular RNA during human fetal development. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, B.; Cao, Y.; Chen, W.; Yin, L.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, Z. High expression levels and localization of Sox5 in dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiselak, E.A.; Shen, X.; Song, J.; Gude, D.R.; Wang, J.; Brody, S.L.; Strauss, J.F. 3rd, Zhang, Z. Transcriptional regulation of an axonemal central apparatus gene, sperm-associated antigen 6, by a SRY-related high mobility group transcription factor, S-SOX5. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 30496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.Q.; Dong, P.; Li, D.Y.; Hu, C.C.; Li, H.P.; Lu, P.; Pan, X.X.; He, L.L.; Xu, X.; Xu, Q. Clinical characterization of Lamb-Shaffer syndrome: a case report and literature review. BMC Med. Genomics 2023, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diawara, M.; Martin, L.J. Regulatory mechanisms of SoxD transcription factors and their influences on male fertility. Reprod. Biol. 2023, 23, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, I.L.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Liu, G.; Lam, K.; Veinot, J.P.; Birnie, D.H.; Jones, D.L.; Krahn, A.D.; Lemery, R.; et al. Paradigm of genetic mosaicism and lone atrial fibrillation: physiological characterization of a connexin 43-deletion mutant identified from atrial tissue. Circulation 2010, 122, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbar, D.; Kannankeril, P.J.; Donahue, B.S.; Kucera, G.; Stubblefield, T.; Haines, J.L.; George, A.L., Jr.; Roden, D.M. Cardiac sodium channel (SCN5A) variants associated with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2008, 117, 1927–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinor, P.T.; Nam, E.G.; Shea, M.A.; Milan, D.J.; Ruskin, J.N.; MacRae, C.A. Cardiac sodium channel mutation in atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2008, 5, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Clauss, S.; Berger, I.M.; Weiß, B.; Montalbano, A.; Röth, R.; Bucher, M.; Klier, I.; Wakili, R.; Seitz, H.; et al. Coding and non-coding variants in the SHOX2 gene in patients with early-onset atrial fibrillation. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2016, 111, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Paone, C.; Sumer, S.A.; Diebold, S.; Weiss, B.; Roeth, R.; Clauss, S.; Klier, I.; Kääb, S.; Schulz, A.; et al. Functional Characterization of Rare Variants in the SHOX2 Gene Identified in Sinus Node Dysfunction and Atrial Fibrillation. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, M.S.; Holst, A.G.; Jabbari, J.; Nielsen, J.B.; Christophersen, I.E.; Sajadieh, A.; Haunsø, S.; Svendsen, J.H. Genetic loci on chromosomes 4q25, 7p31, and 12p12 are associated with onset of lone atrial fibrillation before the age of 40 years. Can. J. Cardiol. 2012, 28, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeufer, A.; van Noord, C.; Marciante, K.D.; Arking, D.E.; Larson, M.G.; Smith, A.V.; Tarasov, K.V.; Müller, M.; Sotoodehnia, N.; Sinner, M.F.; et al. Genome-wide association study of PR interval. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.M.; Roh, S.Y.; Lee, D.I.; Shim, J.; Choi, J.I.; Park, S.W.; Kim, Y.H. The Effects of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Korean Patients with Early-onset Atrial Fibrillation after Catheter Ablation. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, S.; Rudaka, I.; Rots, D.; Isakova, J.; Kalējs, O.; Vīksne, K.; Gailīte, L. A Higher Polygenic Risk Score Is Associated with a Higher Recurrence Rate of Atrial Fibrillation in Direct Current Cardioversion-Treated Patients. Medicina 2021, 57, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, M.B.; Olesen, M.S.; Christophersen, I.E.; Nielsen, J.B.; Carlson, J.; Holmqvist, F.; Tveit, A.; Haunsø, S.; Svendsen, J.H.; Platonov, P.G. Genetic variants on chromosomes 7p31 and 12p12 are associated with abnormal atrial electrical activation in patients with early-onset lone atrial fibrillation. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2019, 24, e12661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Morales, P.L.; Quiroga, A.C; Barbas, J.A.; Morales, A.V. SOX5 controls cell cycle progression in neural progenitors by interfering with the WNT-beta-catenin pathway. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Zheng, R.; Shi, C.; Chen, D.; Jin, X.; Hou, J.; Xu, G.; Hu, B. DACT2 modulates atrial fibrillation through TGF/beta and Wnt signaling pathways. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Li, R.; Hao, J.F.; Chen, L.W.; Liu, S.T.; Zhang, X.L.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Yang, J.K.; Zou, Y.X.; Wang, H. Accumulated beta-catenin is associated with human atrial fibrosis and atrial fibrillation. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasis, P.; Theofilis, P.; Vlachakis, P.K.; Korantzopoulos, P.; Patoulias, D.; Antoniadis, A.P.; Fragakis, N. Atrial Fibrosis in Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanistic Insights, Diagnostic Challenges, and Emerging Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Yao, Z. Interactions between atrial fibrosis and inflammation in atrial fibrillation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1578148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, A.; Sutaria, A.; Montaser, Z.; Magar, T.P.; El Ashal, G.; Zaghloul, S.; Tom, A.J.; Ahmad, M.; Creta, A.; Ali, H.; et al. Fibrosis-Guided Ablation in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2025, 36, 2025–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, T.; Coustry, F.; Stephens, S.; Eberspaecher, H.; Takigawa, M.; Yasuda, H.; de Crombrugghe, B. Transcriptional regulation of chondrogenesis by coactivator Tip60 via chromatin association with Sox9 and Sox5. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 3011–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Ahsen, O.O; Liu, J.J.; Du, C.; McKee, M.L.; Yang, Y; Wasco, W. ; Newton-Cheh, C.H.; O'Donnell, C.J; Fujimoto, J.G.; et al. Silencing of the Drosophila ortholog of SOX5 in heart leads to cardiac dysfunction as detected by optical coherence tomography. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 3798–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, P.; Li, P.; Mandel, J.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, J.M.; Behringer, R.R.; de Crombrugghe, B.; Lefebvre, V. The transcription factors L-Sox5 and Sox6 are essential for cartilage formation. Dev. Cell 2001, 1, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersh, C.P.; Silverman, E.K.; Gascon, J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Klanderman, B.J.; Litonjua, A.A.; Lefebvre, V.; Sparrow, D.; Reilly, J.J.; Anderson, W.H.; et al. SOX5 is a candidate gene for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease susceptibility and is necessary for lung development. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 1482–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, Z.M.; Delbono, O. Charge movement and transcription regulation of L-type calcium channel alpha(1S) in skeletal muscle cells. J. Physiol. 2002, 540, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, B.; de Roos, R.; Bluyssen, H.; Kemmeren, P.; Holstege, F.; Joles, J.A.; Koomans, H. Nitric oxide-dependent and nitric oxide-independent transcriptional responses to high shear stress in endothelial cells. Hypertension 2005, 45, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Thomas, G.N.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Shantsila, A. Endothelial function in patients with atrial fibrillation. Ann. Med. 2020, 52, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio-Castano, J.; Gómez, Á.S.; Coronado, M.; Rodríguez-Martín, P.; Parra, A.; Pascual, P.; Cazalla, M.; Gallego, N.; Arias, P.; Morales, A.V.; et al. Lamb-Shaffer syndrome: 20 Spanish patients and literature review expands the view of neurodevelopmental disorders caused by SOX5 haploinsufficiency. Clin. Genet. 2023, 104, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

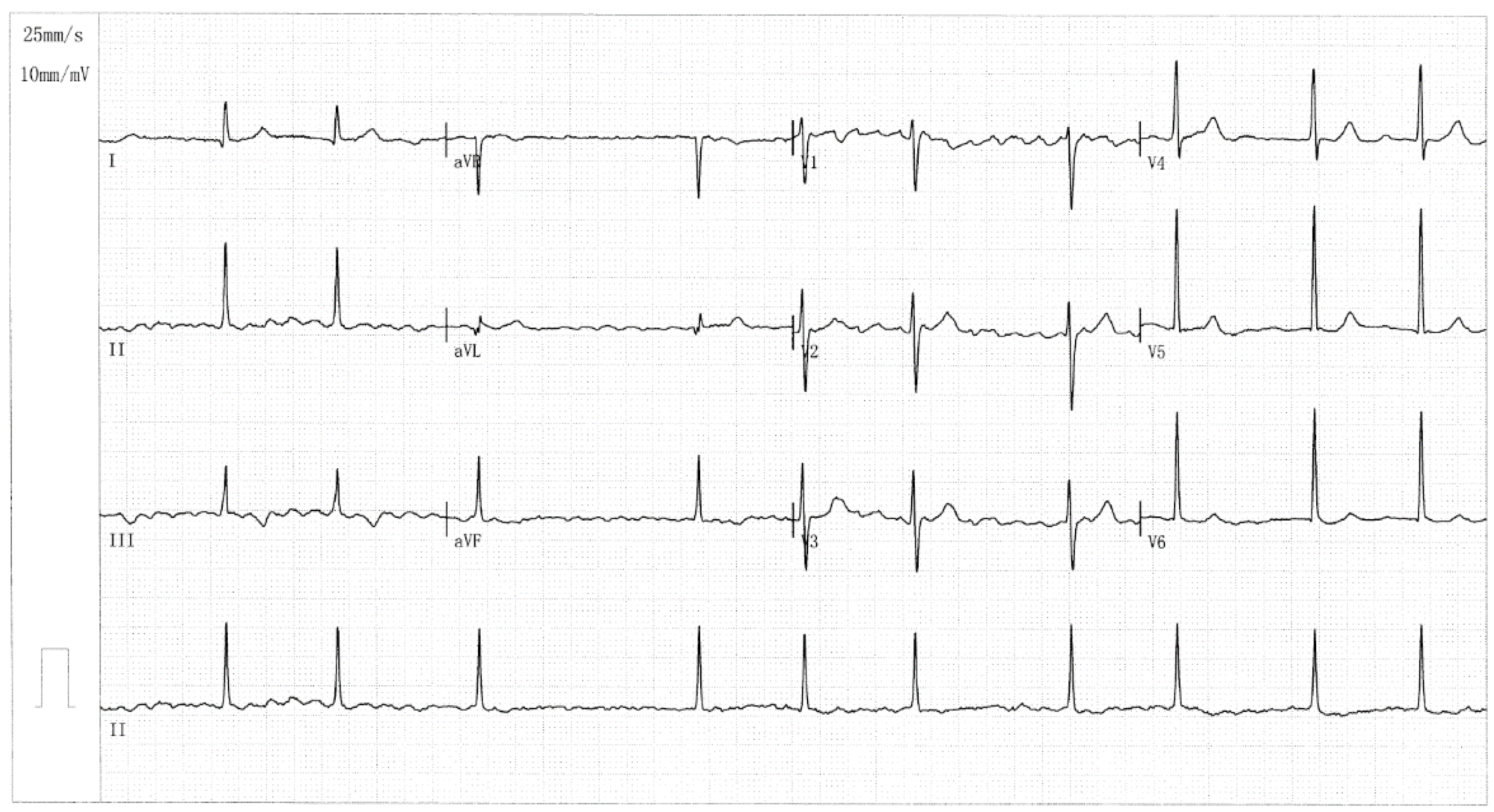

| Individual information | Cardiac manifestation | Electrocardiogram | Echocardiogram | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity (Pedigree AF-001) |

Sex | Age at first diagnosis of AF (years) | Age at enrollment (years) | AF (clinical categorizing) | Heart rate (beats/min) | QRS interval (ms) | QTc (ms) |

LAD (mm) | LVEF (%) |

| II-6 II-7 III-2 III-7 III-10 IV-1 |

F M F M F M |

51 47 42 35 40 24 |

66 63 48 42 40 24 |

LSP LSP LSP LSP Persistent Paroxysmal |

69 76 105 83 112 90 |

86 118 92 95 105 81 |

435 507 482 394 416 413 |

39 36 38 33 32 29 |

58 62 60 63 64 66 |

| Variable | Case group (n =236) | Control group (n =312) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) Age (years) Family history of atrial fibrillation (%) History of cerebral stroke (%) History of implanting a pacemaker (%) Body mass index (kg/m2) Total cholesterol (mmol/L) Fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) Triglyceride (mmol/L) Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) Resting heart rate (beats/min) Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) Left atrial diameter (mm) |

135/101 54.16 ± 7.39 48 (20.33) 15 (6.36) 12 (5.08) 22.85 ± 3.10 4.15 ± 0.57 4.46 ± 0.62 1.38 ± 0.35 127.84 ± 9.07 84.73 ± 7.46 77.01 ± 8.47 62.25 ± 7.13 37.82 ± 6.52 |

178/134 53.82 ± 8.02 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 23.06 ± 2.96 4.21 ± 0.61 4.50 ± 0.69 1.40 ± 0.31 128.18 ± 9.41 85.03 ± 9.02 76.88 ± 7.64 62.91 ± 7.22 36.05 ± 6.08 |

0.9716 0.6115 <0.0001* <0.0001* <0.0001* 0.4207 0.2415 0.4832 0.4797 0.6707 0.6785 0.8508 0.2872 0.0011* |

| Coding exon | Forward primer (5´→3´) | Backward primer (5´→3´) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

GGTTGTCTAGAGCCTTGCAGC GTTCTGTTGCTACCTGCTTGGC TCAGCTGAATAAGCCATATAACC GAAGTGGGGCTGGGATAGGG TTATTTCCAGCTGGCCCTAGCAT CTGCCGTGGTATCTTAGGCTTC TGGGAAGAAGCATGGAGCATC AAAAGGATGAGGTTTCCGCCT TGTTTCGGGTGCCCATTTCAAG TTTGATGGGAAATGACAGGCTGC GGCCAGACACTACCTATTACCAAGA GGCATACCAAACCCAAACGCC CATTTGCCACCACAAGGCTTATC AGGTACAAAACCACCACCACCT ACATCTAACTATTCACTTACCCACG |

TTTGGTCCGGGCAATCACAAC CTAAGACGCCAGGGGTGAATC CAAGCAGGTGACTATTCCCG GAAGCAGAAGAGGTGAGGGCA TGTTGTGTGCCTAGGACAGTGA TGGTTCCCTGCACCTATCCAG ATGATGCGAGTCCAGAGTCAAGA TTGTTAAGTCGCCTTGCTCCT AGCTGCTGGCATACAATAGACA AAACGGACCTAGGTGGTTCCTC ACAAGCTGGTGGCGTAAAAGG AATGATGAGGTATGAGGTGGCTG ATCCAGGATCCTTCCACAACTGC TGGTAGAGCTAGGAACTTGCAGTG GTGCTTGGCCACTGGTAAGG |

541 555 660 300 656 638 648 678 681 418 500 456 440 592 435 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).