Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

05 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

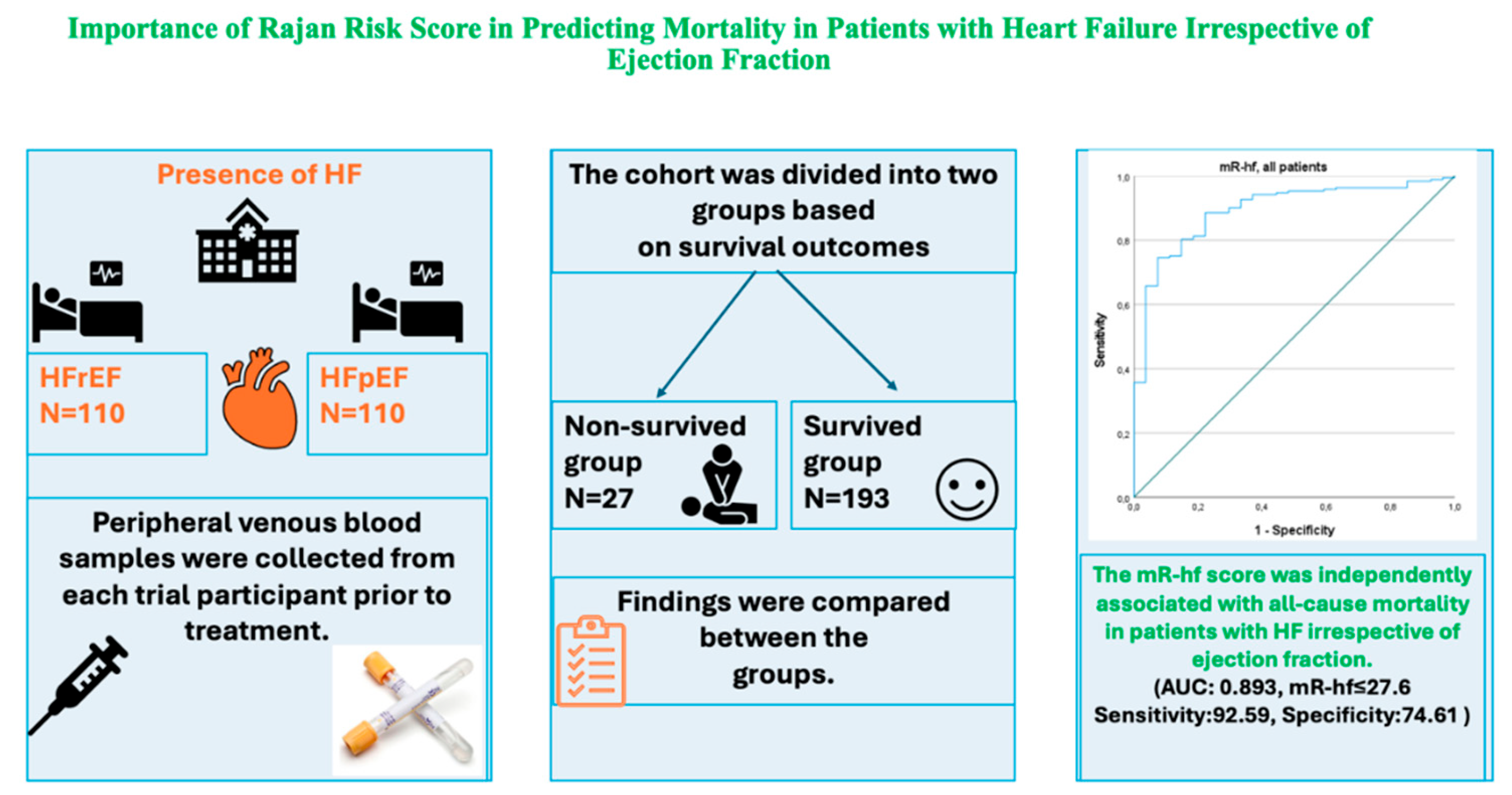

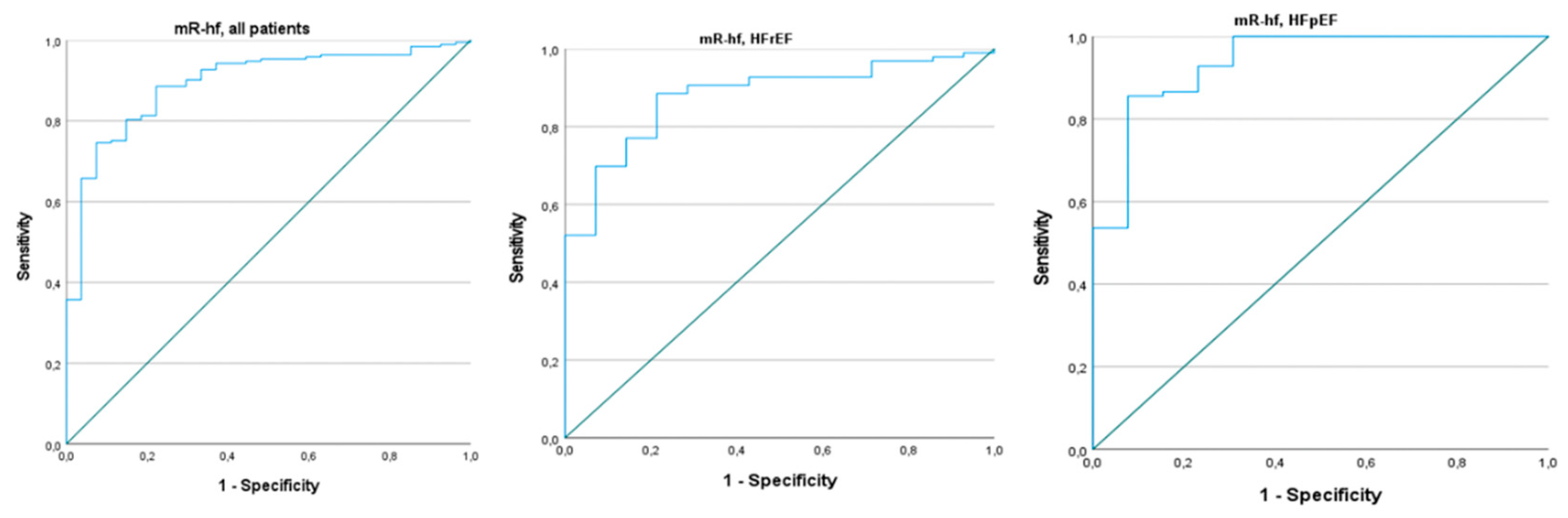

Background and Objectives: To date, the role of the modified Rajan’s heart failure (mR-hf) risk score has been studied in patients with heart failure with reduced (HFrEF) and mid-range ejection fraction (EF). However, it has not been investigated in subjects with preserved EF (HFpEF). We aimed to examine the predictive value of the mR-hf risk score for mortality in both HFrEF and HFpEF. Methods: A total of 220 patients with HFrEF and HFpEF were included in this retrospective study. The study sample was divided into two groups according to mortality. Findings were compared between the groups. Results: The Non-survived group included 27 subjects, while the Survived group comprised 193 patients. The mR-hf risk score was significantly lower in the Non-survived group than the Survived group (p<0.001). According to the multivariate analysis, the mR-hf risk score and New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification were independently associated with all-cause mortality (OR: 0.938, 95% CI: 0.905-0.972; p<0.001 and OR: 2.278, 95% CI: 1.161-4.468; p=0.017, respectively). Furthermore, the mR-hf risk score predicted mortality in both HFrEF and HFpEF (p values, <0.015 and <0.004, respectively). Conclusion: The mR-hf risk score could be a simple tool for predicting mortality in patients with HF, irrespective of EF.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Definitions

2.2.1. Heart Failure

2.2.2. Rajan Heart Failure Score

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bozkurt, B. , Coats, A. J., Tsutsui, H., Abdelhamid, M., Adamopoulos, S., Albert, N., et al (2021). Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the heart failure society of America, heart failure association of the European society of cardiology, Japanese heart failure society and writing committee of the universal definition of heart failure. Journal of cardiac failure, 27(4), 387-413.

- Taylor CJ, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Roalfe AK, Lay-Flurrie S, Jones NR, Marshall T, et al. Trends in survival after a diagnosis of heart failure in the United Kingdom 2000-2017: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2019 Feb 13;364:l223. [CrossRef]

- Conrad N, Judge A, Tran J, Mohseni H, Hedgecott D, Crespillo AP, et al. Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population-based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet. 2018 Feb 10;391(10120):572-580. [CrossRef]

- Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, Cropp AB, et al. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):1424-33. [CrossRef]

- Aaronson KD, Schwartz JS, Chen TM, Wong KL, Goin JE, Mancini DM. Development and prospective validation of a clinical index to predict survival in ambulatory patients referred for cardiac transplant evaluation. Circulation. 1997 Jun 17;95(12):2660-7. [CrossRef]

- Meta-analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure (MAGGIC). The survival of patients with heart failure with preserved or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2012 Jul;33(14):1750-7. [CrossRef]

- Rajan R, Al Jarallah M. New Prognostic Risk Calculator for Heart Failure. Oman Med J. 2018 May;33(3):266-267. [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R. , Al Jarallah, M., Al Zakwani, I., Dashti, R., Bulbanat, B., Ridha, M., et al. Impact of R-hf risk score on all-cause mortality in acute heart failure patients in the Middle East. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 25(8), S97.

- Rajan, R. , Hui, J. M. H., Al Jarallah, M. A., Tse, G., Chan, J. S. K., Satti, D. I., et al. (2024). The modified Rajan’s heart failure risk score predicts all-cause mortality in patients hospitalized for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a retrospective cohort study. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 86(4), 1843-1849. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T. A. , Metra, M., Adamo, M., Gardner, R. S., Baumbach, A., Böhm, M., et al. (2021). 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European heart journal, 42(36), 3599-3726.

- Heidenreich, P. A. , Bozkurt, B., Aguilar, D., Allen, L. A., Byun, J. J., Colvin, M. M., et al. 2022 ACC/AHA/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary. Journal of cardiac failure, 28(5), 810-830.

- Nagueh, S. F. , Smiseth, O. A., Appleton, C. P., Byrd, B. F., Dokainish, H., Edvardsen, T., et al. (2016). Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. European Journal of Echocardiography, 17(12), 1321-1360. [CrossRef]

- Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015 Mar;16(3):233-70. [CrossRef]

- Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic P, Rosano GMC, Coats AJS. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2023 Jan 18;118(17):3272-3287. [CrossRef]

- Writing Group Members; Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016 Jan 26;133(4):e38-360. [CrossRef]

- Zarrinkoub R, Wettermark B, Wändell P, Mejhert M, Szulkin R, Ljunggren G, et al. The epidemiology of heart failure, based on data for 2.1 million inhabitants in Sweden. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013 Sep;15(9):995-1002. [CrossRef]

- Angraal S, Mortazavi BJ, Gupta A, Khera R, Ahmad T, Desai NR, et al. Machine Learning Prediction of Mortality and Hospitalization in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2020 Jan;8(1):12-21. [CrossRef]

- Voors AA, Ouwerkerk W, Zannad F, van Veldhuisen DJ, Samani NJ, Ponikowski P, et al. Development and validation of multivariable models to predict mortality and hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017 May;19(5):627-634. [CrossRef]

- Ouwerkerk W, Voors AA, Zwinderman AH. Factors influencing the predictive power of models for predicting mortality and/or heart failure hospitalization in patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2014 Oct;2(5):429-36. [CrossRef]

- Pocock SJ, Ariti CA, McMurray JJ, Maggioni A, Køber L, Squire IB, et al.; Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure. Predicting survival in heart failure: a risk score based on 39 372 patients from 30 studies. Eur Heart J. 2013 May;34(19):1404-13. [CrossRef]

- Rohde LE, Zimerman A, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Associations Between New York Heart Association Classification, Objective Measures, and Long-term Prognosis in Mild Heart Failure: A Secondary Analysis of the PARADIGM-HF Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023 Feb 1;8(2):150-158. [CrossRef]

- Raphael C, Briscoe C, Davies J, Ian Whinnett Z, Manisty C, Sutton R, et al. Limitations of the New York Heart Association functional classification system and self-reported walking distances in chronic heart failure. Heart. 2007 Apr;93(4):476-82. [CrossRef]

- Tran AT, Chan PS, Jones PG, Spertus JA. Comparison of Patient Self-reported Health Status With Clinician-Assigned New York Heart Association Classification. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Aug 3;3(8):e2014319. [CrossRef]

- Greene SJ, Butler J, Spertus JA, Hellkamp AS, Vaduganathan M, DeVore AD, et al. Comparison of New York Heart Association Class and Patient-Reported Outcomes for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 May 1;6(5):522-531. [CrossRef]

- Bianco CM, Farjo PD, Ghaffar YA, Sengupta PP. Myocardial Mechanics in Patients With Normal LVEF and Diastolic Dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Jan;13(1 Pt 2):258-271. [CrossRef]

- Mitter SS, Shah SJ, Thomas JD. A Test in Context: E/A and E/e' to Assess Diastolic Dysfunction and LV Filling Pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Mar 21;69(11):1451-1464. [CrossRef]

- Blair JE, Huffman M, Shah SJ. Heart failure in North America. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2013 May;9(2):128-46. [CrossRef]

- Januzzi JL, van Kimmenade R, Lainchbury J, Bayes-Genis A, Ordonez-Llanos J, Santalo-Bel M, et al. NT-proBNP testing for diagnosis and short-term prognosis in acute destabilized heart failure: an international pooled analysis of 1256 patients: the International Collaborative of NT-proBNP Study. Eur Heart J. 2006 Feb;27(3):330-7. [CrossRef]

- Fonarow GC, Peacock WF, Phillips CO, Givertz MM, Lopatin M; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. Admission B-type natriuretic peptide levels and in-hospital mortality in acute decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007 May 15;49(19):1943-50. [CrossRef]

- Cleland JG, McMurray JJ, Kjekshus J, Cornel JH, Dunselman P, Fonseca C, et al; CORONA Study Group. Plasma concentration of amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in chronic heart failure: prediction of cardiovascular events and interaction with the effects of rosuvastatin: a report from CORONA (Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Trial in Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Nov 10;54(20):1850-9. [CrossRef]

- Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C, Sanderson JE, Rusconi C, Flachskampf FA, Rademakers FE, et al. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: a consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007 Oct;28(20):2539-50. [CrossRef]

- Valle R, Aspromonte N, Feola M, Milli M, Canali C, Giovinazzo P, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide can predict the medium-term risk in patients with acute heart failure and preserved systolic function. J Card Fail. 2005 Sep;11(7):498-503. [CrossRef]

- Anand IS, Rector TS, Cleland JG, Kuskowski M, McKelvie RS, Persson H, et al. Prognostic value of baseline plasma amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and its interactions with irbesartan treatment effects in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: findings from the I-PRESERVE trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2011 Sep;4(5):569-77. [CrossRef]

- Yan J, Gong SJ, Li L, Yu HY, Dai HW, Chen J, et al. Combination of B-type natriuretic peptide and minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production slope improves risk stratification in patients with diastolic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013 Jan 20;162(3):193-8. [CrossRef]

- Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Basic science: Pathophysiology: the cardiorenal metabolic syndrome. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014 Aug;8(8):604-6. [CrossRef]

- Damman K, Valente MA, Voors AA, O'Connor CM, van Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL. Renal impairment, worsening renal function, and outcome in patients with heart failure: an updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014 Feb;35(7):455-69. [CrossRef]

- Huang WM, Chang HC, Lee CW, Huang CJ, Yu WC, Cheng HM, et al. Impaired renal function and mortalities in acute heart failure with different phenotypes. ESC Heart Fail. 2022 Oct;9(5):2928-2936. [CrossRef]

- Anand, IS. Anemia and chronic heart failure implications and treatment options. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Aug 12;52(7):501-11. [CrossRef]

- Datta BN, Silver MD. Cardiomegaly in chronic anaemia in rats; gross and histologic features. Indian J Med Res. 1976 Mar;64(3):447-58.

- Rich JD, Burns J, Freed BH, Maurer MS, Burkhoff D, Shah SJ. Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic (MAGGIC) Heart Failure Risk Score: Validation of a Simple Tool for the Prediction of Morbidity and Mortality in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Oct 16;7(20):e009594. [CrossRef]

- Peterson PN, Rumsfeld JS, Liang L, Albert NM, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, et al; American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines-Heart Failure Program. A validated risk score for in-hospital mortality in patients with heart failure from the American Heart Association get with the guidelines program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010 Jan;3(1):25-32. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Survived (n=193) | Non-survived (n=27) | Total (n=220) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 69±11 | 76±10 | 70±11 | 0.001 | |

| Female, n (%) | 72 (37.3) | 6 (22.2) | 78 (35.5) | 0.126 | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 140 (72.5) | 20 (74.1) | 160 (72.7) | 0.867 | |

| DM, n (%) | 58 (30.1) | 6 (22.2) | 64 (29.1) | 0.403 | |

| COPD, n (%) | 61 (31.6) | 10 (37) | 71 (32.3) | 0.573 | |

| Current Smoker, n (%) | 34 (17.6) | 4 (14.8) | 38 (17.3) | 0.719 | |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 43 (22.3) | 5 (18.5) | 48 (21.8) | 0.658 | |

| History of PCI, n (%) | 91 (47.2) | 13 (48.1) | 104 (47.3) | 0.923 | |

| ASA, n (%) | 82 (42.5) | 12 (44.4) | 94 (42.7) | 0.848 | |

| Statin, n (%) | 76 (39.4) | 14 (51.9) | 90 (40.9) | 0.218 | |

| P2Y12-i, n (%) | 36 (18.7) | 4 (14.8) | 40 (18.2) | 0.629 | |

| RAAS Blockers, n (%) | 117 (60.6) | 17 (63) | 134 (60.9) | 0.816 | |

| Beta Blockers, n (%) | 163 (84.5) | 20 (74.1) | 183 (83.2) | 0.178 | |

| MRA, n (%) | 60 (31.1) | 10 (37) | 70 (31.8) | 0.535 | |

| SGLT2-i, n (%) | 76 (39.4) | 8 (29.6) | 84 (38.2) | 0.330 | |

| Loop Diuretics, n (%) | 138 (71.5) | 24 (88.9) | 162 (73.6) | 0.055 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL (IQR) | 13.6 (12-14.9) | 13.2 (12-13.8) | 13.5 (12-14.9) | 0.170 | |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 (SD) | 70±23 | 50±19 | 67±24 | <0.001 | |

| HbA1c, % (SD) | 6.4±1.1 | 6.4±0.7 | 6.4±1.1 | 0.354 | |

| Glucose, mg/dl (SD) | 132±59 | 128±29 | 132±56 | 0.162 | |

| Albumin, g/L (SD) | 3.5±0.5 | 3.5±0.3 | 3.5±0.5 | 0.508 | |

| Platelet, 109/L (SD) | 214±71 | 195±54 | 211±69 | 0.172 | |

| TSH, mlU/L (IQR) | 1.78 (1.10-3.08) | 1.60 (1.20-2.33) | 1.78 (1.10-3.0) | 0.553 | |

| ALT, U/L (IQR) | 20 (14-33) | 28 (22-38) | 22 (14-34) | 0.128 | |

| AST, U/L (IQR) | 23 (16-33) | 21 (15-32) | 23 (16-32) | 0.244 | |

| NA, mmol/L (SD) | 139±4 | 138±3 | 138±4 | 0.100 | |

| K, mmol/L (SD) | 4.2±0.6 | 4.2±0.9 | 4.2±0.6 | 0.425 | |

| BNP, ng/L (IQR) | 568 (352-1021) | 1822 (1344-2600) | 655 (365-1227) | <0.001 | |

| NYHA Class, n (%) | 1 | 40 (20.1) | 1 (3.7) | 41 (18.6) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 111 (57.6) | 7 (25.9) | 118 (53.6) | ||

| 3 | 37 (19.2) | 12 (44.5) | 49 (22.3) | ||

| 4 | 5 (2.6) | 7 (25.9) | 12 (%5.5) | ||

| EF, % (SD) | 41±16 | 39±14 | 41±15 | 0.517 | |

| E, cm/sec (SD) | 92±17 | 96±10 | 92±16 | 0.113 | |

| A, cm/sec (SD) | 68±23 | 62±17 | 69±22 | 0.300 | |

| E/A ratio (SD) | 1.5±0.5 | 1.7±0.5 | 1.5±0.5 | 0.072 | |

| e' (mean), cm/sec (SD) | 7.2±2 | 6.0±1 | 7.0±2 | <0.001 | |

| E/e' (SD) | 14±4 | 16±2 | 14±4 | <0.001 | |

| mR-hf Risk Score (IQR) | All patients | 58.6 (27.3-95.6) | 12.9 (7.5-19.2) | 53.6 (22-85.6) | <0.001 |

| HFrEF group | 44.7 (20.6-70.8) | 8.2 (4.9-14.6) | 35 (17.5-67.4) | <0.001 | |

| HFpEF group | 81.9 (46.9-131.1) | 16.3 (12.3-22.7) | 72.3 (30.3-118.9) | <0.001 | |

| A | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||||||||||

| Variables | OR | 95% C.I. | P | OR | 95% C.I. | P | |||||||||

| Age | 1.073 | 1.028 | 1.120 | 0.001 | - | ||||||||||

| e' (mean) | 0.612 | 0.452 | 0.827 | 0.001 | - | ||||||||||

| NYHA class. | 4.462 | 2.475 | 8.043 | <0.001 | 2.278 | 1.161 | 4.468 | 0.017 | |||||||

| mR-hf Risk Score | 0.920 | 0.886 | 0.956 | <0.001 | 0.938 | 0.905 | 0.972 | <0.001 | |||||||

| B | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||||||||

| Variables | OR | 95% C.I. | P | OR | 95% C.I. | P | |||||||||

| e’ (mean) | 0.480 | 0.280 | 0.824 | 0.008 | - | ||||||||||

| NYHA class. | 4.015 | 1.839 | 8.768 | <0.001 | - | ||||||||||

| mR-hf Risk Score | 0.900 | 0.842 | 0.963 | 0.002 | 0.930 | 0.877 | 0.986 | 0.015 | |||||||

| C | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||||||||

| Variables | OR | 95% C.I. | P | OR | 95% C.I. | P | |||||||||

| Age | 1.160 | 1.068 | 1.260 | <0.001 | - | ||||||||||

| e’ (mean) | 0.679 | 0.477 | 0.967 | 0.032 | - | ||||||||||

| NYHA class. | 5.344 | 2.117 | 13.493 | <0.001 | 3.703 1.096 12.513 | 0.035 | |||||||||

| mR-hf Risk Score | 0.907 | 0.850 | 0.967 | 0.003 | 0.920 | 0.870 | 0.973 | 0.004 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).