1. Introduction

There has been a paradigm shift in the understanding of cultural heritage, which is now regarded as more than merely a static collection of monuments, artefacts and traditions [

1,

2]. International frameworks largely recognize heritage as a living resource for identity, social cohesion, and sustainable futures. The 1972 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Convention affirmed cultural and natural assets as part of a shared global legacy [

3]. More recently, the Council of Europe’s Faro Convention [

4] advanced a people-centered perspective that foregrounds the social, civic, and educational roles of heritage. Together, these instruments advance a systemic vision by embedding conservation within broader urban agendas of sustainability, participation, and resilience, consistent with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

5], particularly SDG 11.4 and SDG 4.7. Heritage is thus regarded not solely as a domain for specialist preservation, but also as a civic resource that cultivates values, competencies, and a shared sense of responsibility.

These policy shifts have been paralleled by similar academic debates. In heritage studies, researchers have argued that heritage is inherently pluralistic and values-based, shaped by social negotiations rather than just expert discourses [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Bandarin and van Oers [

10] were among those who conceptualized urban heritage as a catalyst for community resilience and cohesion. Recently, Champion and Rahaman [

11], have explored how digital storytelling and narrative coherence can mediate how people make meaning. Recent works by Moraitou and colleagues [

12] and Katsianis & Gadolou [

13] have further reinforced the concept that heritage becomes significant when connected to everyday practices and collective futures. Accordingly, heritage is not only something to preserve but also a ‘living space for learning and participation’ [

14] that should be actively mobilized. Also, as Choay [

15] critically pointed out, heritage often remains detached from sustainability discussions in our daily lives, risking aestheticization or commodification instead of fostering active civic engagement. Choay’s critique is grounded in the view that heritage, natural, cultural, tangible, and intangible, is unique and therefore non-renewable, a status that is often sidelined in everyday sustainability discourse [

16,

17]. Bridging this remains a significant challenge for both research and practice.

Digital heritage has experienced rapid progress, altering the strategies for documenting and preserving cultural assets and their dissemination to the public. Initial research focused on photogrammetry and 3D modeling but has since expanded to include immersive media like Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), and Extended Reality (XR), alongside geographic information systems (GIS) and building information modeling (BIM) [

18].

Concurrently, advancements in semantic data and interoperability standards, such as CIDOC-CRM [

19] and the FAIR principles [

20], underscore the necessity to organize assets in a manner that ensures their reusability, accessibility, and integration across diverse platforms [

21,

22]. The field is shifting from discrete digital replicas to interconnected ecosystems that integrate heritage with infrastructures for knowledge production, education, and civic participation. In these ecosystems, heritage is intricately integrated into broader infrastructures with the aim of facilitating knowledge dissemination, educational initiatives and civic participation.

Within this context, digital mediation is enabling heritage to be rediscovered

in situ [

23,

24]. Location-based applications and augmented reality have been shown to draw attention to details that would otherwise go unnoticed. These technologies connect contemporary streetscapes with historical imagery, thereby transforming urban exploration into a coherent narrative rather than a series of isolated stops [

11,

25,

26]. Evidence from other studies indicates gains for both interpretation and preservation [

2,

27,

28]. In parallel, semantic and cartographic approaches help maintain continuity across places and media [

29,

30,

31]. These position AR not as a mere technical layer but as a mediational tool that shapes narrative and cultural meaning across contexts.

Building on these possibilities, AR has attracted particular interest for crafting situated experiences. By layering digital information onto in-situ settings, it can cultivate close observation and prompt reflection on authenticity. Empirical studies show that AR can deepen interpretation and sustain attention [

32,

33,

34], while also flagging recurring issues such as distraction and short-lived novelty. Most empirical work has been carried out in museum or tourism contexts and tends to focus on brief engagements. Explicit evidence from formal education is limited, especially regarding long-term competence development [

35]. Also, few studies track retention, transfer, or civic dispositions weeks after an intervention. The scarcity of longitudinal or repeated cross-sectional studies constrains understanding of how AR contributes to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) when embedded in curricula and aligned with competence frameworks [

36].

Although the pedagogical discourse on ESD has advanced considerably, continued engagement and awareness-raising activities are necessary. Among the many international efforts, the seminal work of Wiek and his colleagues [

37,

38] and the GreenComp framework at the European level stand out. This European Sustainability Competence Framework [

39] defines sustainability learning as integrating knowledge, skills, values, and agency across four interconnected areas. Designed, among other aims, to guide curriculum innovation, the GreenComp emphasizes that education for sustainability must encompass not only factual knowledge, but also attitudes, behaviors, and dispositions. However, translating GreenComp into practice remains difficult, despite recent implementation efforts [

40]. Conventional classrooms often lack the immediacy and contextual relevance necessary to cultivate sustainability values and civic responsibility. Heritage-contextualized environments, with their tangible, unique and symbolic qualities, offer a promising although little explored context for cultivating sustainability competences [

41,

42].

The city of Aveiro, Portugal, presents an interesting case. Aveiro hosts one of the country’s most significant ensembles of Art Nouveau facades [

43,

44,

45], now recognized as important cultural landmarks and civic symbols. This is evidenced by Aveiro’s membership in the Réseau Art Nouveau Network (RANN), the establishment of the Art Nouveau Museum, and sustained municipal initiatives that safeguard, interpret, and promote this heritage through curated urban paths.

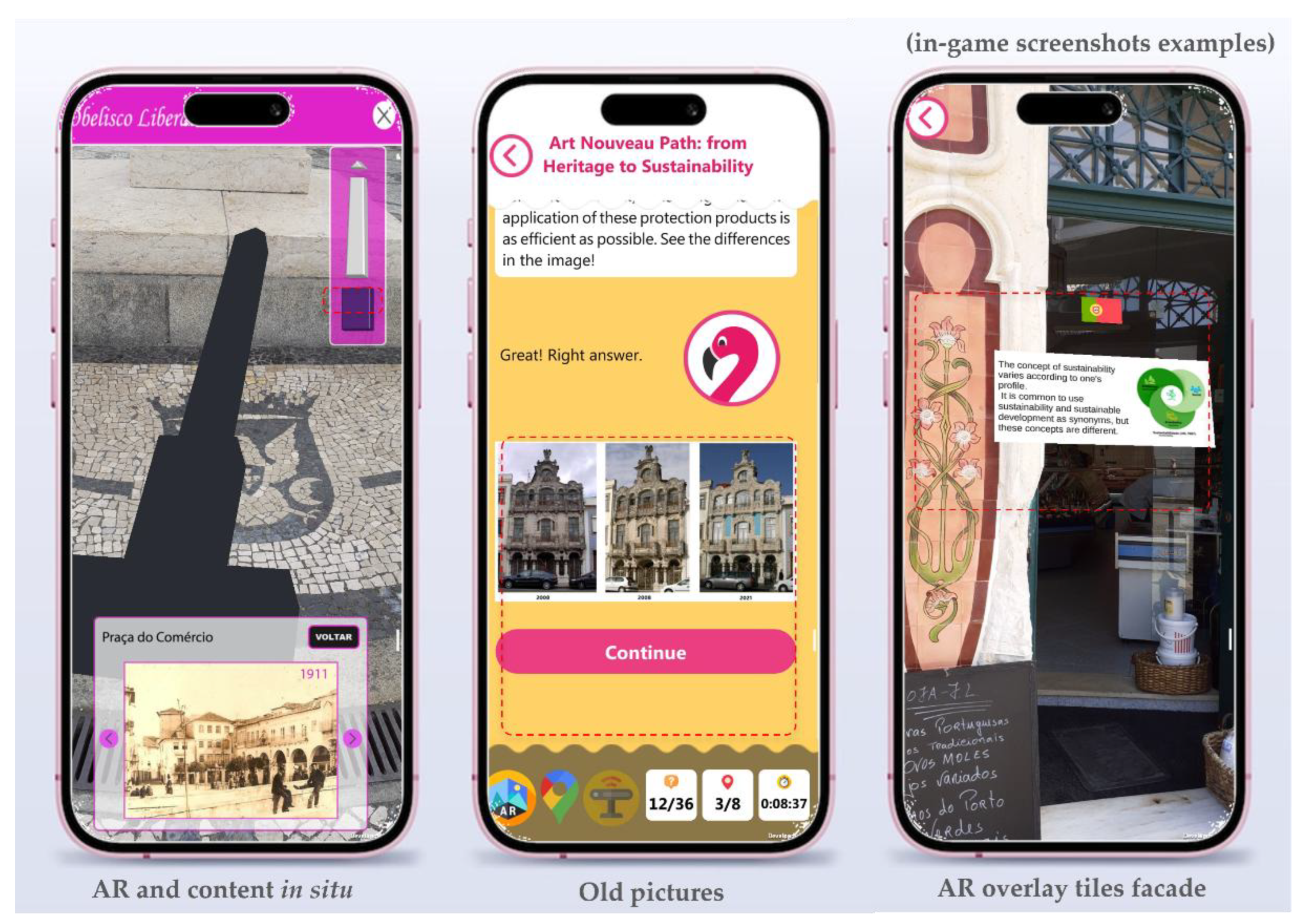

Although their aesthetic value is widely celebrated, educational initiatives tend to rely on guided visits or tourism-oriented narratives, with limited evidence of enduring effects on how young people value the built environment. The real promise for sustainability education lies in the ornamental detail of Aveiro's Art Nouveau local materials and artists, that created buildings decorations based on local fauna and flora. These decorations, mainly concentrated in the building facades, and some public statues and monuments, like the ‘Obelisk of Freedom’ (

Figure 1), are focused on wrought iron works, tiles, architectural details (as in

Figure 2), and floral motifs. These ornaments invite deeper, close observation and interpretation.

Aligned with Gruenewald’s [

46] place-based pedagogy, effective learning occurs when cognitive and emotional processes are anchored in meaningful local contexts. Using Aveiro’s Art Nouveau facades for competence-oriented education is therefore both a distinctive opportunity and a well-suited case study.

Figure 1.

‘Obelisk of Freedom’.

Figure 1.

‘Obelisk of Freedom’.

Figure 2.

Architectural details.

Figure 2.

Architectural details.

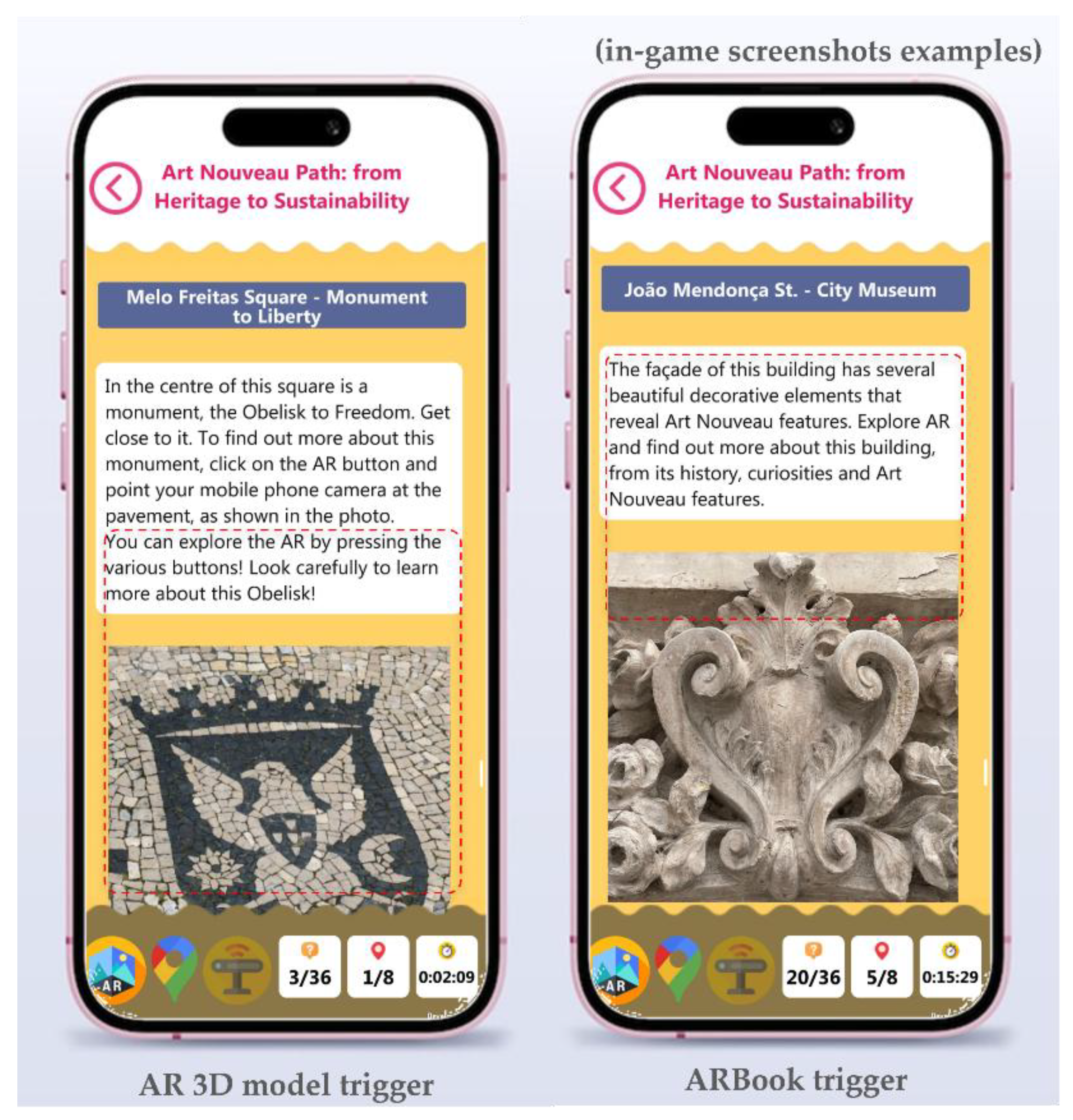

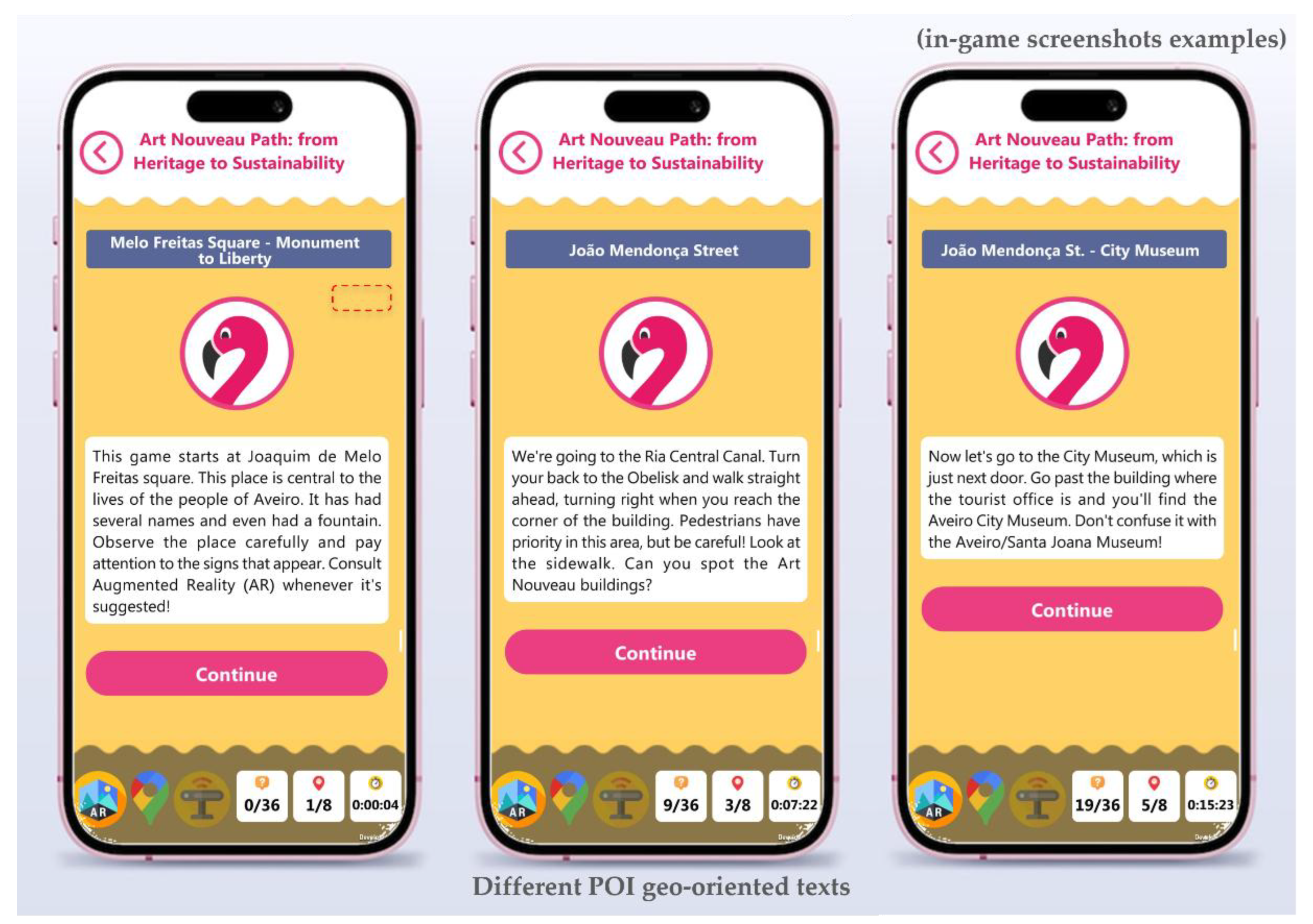

This study examines the Art Nouveau Path, a mobile augmented reality game (MARG) developed within the EduCITY Digital Teaching and Learning Ecosystem (DTLE) (

https://educity.web.ua.pt/) , to explore its potential. This MARG links GreenComp competences [

39] to site-specific tasks by combining AR overlays, multimodal media, and narrative dynamics across eight of Aveiro's Art Nouveau heritage points of interest (POI). Implementation activities were developed based on collaborative work by students’ groups, promoting engagement via MARG and in-place built heritage. Students explored multiple architectural details and connected them via storytelling to local history, historical people, and sustainability competences. This MARG was also designed to promote heritage valorization, connecting it to sustainability reflections and both environment and heritage preservation practices. Teachers accompanied the students and provided structured observations, complementing the gameplay logs and students’ answered questionnaires.

The broader research followed a design-based research (DBR) approach and was implemented in three cross-repeated cross-sectional phases: a baseline (S1-PRE), an immediate post-test (S2-POST), and a follow-up six to eight weeks later (S3-FU). The phases are named after the questionnaires completed by the students. Overall, data sources included three GreenComp-based questionnaires (GCQuest, version tailored for this MARG, available at the project’s Zenodo community page (

https://zenodo.org/communities/artnouveaupath/records/, accessed on 28

th October 2025), gameplay logs capturing 4,248 group-items responses, and ecological observations from 24 teachers. By triangulating these data sets, it was examined whether a heritage-based AR intervention can both enhance cultural assets and promote sustainability competences within this specific context.

The following research questions (RQs) were formulated to guide this study:

(RQ1) Can heritage serve as an effective context for ESD?;

(RQ2) How do multimodality and augmented reality affect engagement and learning outcomes?; and,

(RQ3) To what extent do students retain and transfer heritage-related sustainability competencies after gameplay?

Addressing these questions advances debate in three areas:

(i) the promotion of cultural heritage as an educational asset;

(ii) the importance of digital heritage preservation; and,

(iii) the value of place-based semantic enrichment.

In parallel, this study aims to analyze the educational value of AR, moving beyond novelty to support long-term competence development. The paper's findings may therefore have implications for the design of educational games and broader strategies that incorporate cultural heritage into sustainable learning ecosystems.

In addition to its educational objectives, this study aims to contribute to heritage preservation practice by providing lightweight digital documentation and structured descriptors of georeferenced cultural assets. The study adopts a pragmatic, findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR)-oriented approach to semantic organization and data stewardship. This approach aims to facilitate interpretive reuse, civic engagement, monitoring, and future interoperability with cultural knowledge bases.

Following the introduction,

Section 2 presents a narrative thematic review of the literature and theoretical frameworks.

Section 3 describes the methodological design, including the context, the participants, the instruments, and the DBR approach.

Section 4 reports the findings.

Section 5 discusses the pedagogical and methodological implications of these results. The final section synthesizes the key contributions, identifies limitations, and suggests paths for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework

This section reports a narrative, thematic literature review [

47,

48,

49] conducted in line with established procedures for thematic synthesis, integrating inductive and deductive coding to ensure conceptual coherence across domains [

50,

51].

Given the interdisciplinary scope of this study spanning, the theoretical framework was organized into five categories regarding:

(1) International frameworks for heritage preservation;

(2) Art Nouveau as a cultural resource and as an urban identity asset;

(3) Extended reality approaches applied to heritage, considering AR as the primary technology;

(4) Semantic and geospatial logics for structuring and linking heritage data; and,

(5) Smart Heritage agendas towards the promotion of interoperability, openness, and long-term preservation.

Besides these categories, a transversal core focus is present in the broader research. This regards Education for Sustainability and competences development, with preservation-relevant data practices positioned as complementary and mutually reinforcing.

Searches were conducted in

Scopus and

Web of Science and supplemented with exploratory searches in Google Scholar to capture gray literature and institutional reports. Additionally, some literature was previously used in already published works [

52,

53].

The search period was April–September 2025, targeting works published between 2012 and 2025. Effective keyword combinations included (“augmented reality” OR “mobile augmented reality” OR “mobile augmented reality game” OR MARG) AND “cultural heritage” AND (education OR learning); “Art Nouveau heritage” AND education; (“narrative cartography” OR “spatial storytelling”) AND (mapping OR heritage); (“semantic data enrichment” OR CIDOC-CRM OR “cultural heritage ontology” OR “semantic trajectory”); (“digital heritage preservation” OR “cultural heritage interpretation”); (“valuing urban heritage” OR “heritage valorization”); (“sustainability education” OR “education for sustainable development” OR GreenComp); and (“digital teaching and learning ecosystem” OR DTLE) AND sustainability. Direct searches using “Art Nouveau” predominantly returned art-historical records. We retained only works intersecting education, AR/MARG, geoinformation/trajectory, or competence frameworks and excluded the remainder.

Studies were included if they (1) were peer-reviewed and indexed in Scopus or Web of Science, (2) addressed Education for Sustainable Development and or sustainability competences, such as GreenComp, in formal or non-formal education, and (3) were clearly connected to at least one core focus of this paper. Exclusion criteria comprised (1) AR or XR studies focused solely on technical aspects without pedagogical framing or a link to ESD or competences, (2) tourism-oriented studies and museum studies lacking geoinformation or trajectory components, educational analysis, or in-situ built-heritage context, (3) purely theoretical reflections without empirical or design-based components, (4) VR-only studies without a clear bridge to AR in educational heritage settings, and (5) duplicates or records thematically irrelevant to the study’s scope.

The database search retrieved 74 records. After de-duplication and abstract screening, 24 items were retained for full-text review. Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria yielded 40 peer-reviewed articles. To ensure conceptual breadth, complementary sources were added. The final

corpus comprises 81 sources structured into four categories: (1) 59 peer-reviewed articles (four from prior research outputs), (2) 11 policy and institutional frameworks, (3) 11 books and monographs. Although essential, all sources regarding methodology are not considered in this description (See

Appendix A).

A hybrid thematic analysis was undertaken, integrating inductive and deductive coding. Following Boyd [

49], multiple reasoning modes were iteratively applied to ensure conceptual coherence across the five previously identified domains. The policy frameworks and the reference works grounded the analysis in internationally recognized sources, while the authorship-related publications secured continuity with prior and broader research.

The following subsections examine the five domains in detail. It begins with international frameworks for heritage preservation and concludes with a broader synthesis.

2.1. International Frameworks for Heritage Preservation

Over the past thirty years, there has been a notable shift in international policy embracing cultural heritage as a key element towards the promotion of urban sustainability, among others, fostering community involvement, and building resilience. This approach, although previous efforts, like the European Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society, known as the Faro Convention [

4] articulates with the UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) [

54], which redefines historic cities as living, evolving socio-ecological systems rather than unchanging relics. Within this framework, the HUL methodology promotes conservation practices tailored to each location to ensure heritage is integrated into planning, cultural markets, and broader societal well-being. Also, this framework highlights the increasing importance of digital tools in heritage documentation, evaluation, renovation, and public engagement. The Sustainable Development Goals [

5], especially SDG 11.4, regarding protecting cultural and natural heritage, highlight the urgent need to them as part of a strategy to nurture inclusive, secure, adaptable, and sustainable urban environments [

5]. Similarly, the New Urban Agenda, adopted in Quito in 2016 [

55], emphasizes the essential role of culture and heritage in the promotion of civic identity, values and memory, promoting urban prosperity, and bolstering resilience against environmental and human-induced challenges.

The novelty of the Faro Convention [

4] resides on the express recognition of cultural heritage not only as a human right but also as a shared societal resource, underscoring the significance of participation, identity, and overall well-being. Building on this foundation, the European Heritage Strategy for the 21st Century [

56] translated these guiding concepts into clear priorities for heritage education, improved access, and the sustainable management of cultural assets. Recently, new initiatives like the Common European Data Space for Cultural Heritage [

57] and the Twin it! 3D for Europe’s culture campaign (available at:

https://pro.europeana.eu/page/twin-it-3d-for-europe-s-culture, accessed on 24

th September 2025) have further established the importance of digitally documenting cultural assets in formats that support interoperability. This is intended to promote long-term preservation, openness, and opportunities for reuse throughout various sectors. These approaches connect heritage preservation with the development of digital ecosystems and semantic infrastructures, structured digital environments that make data sharing and knowledge exchange possible.

These new perspectives are reinforced by academic research. For example, Bandarin and van Oers [

10] argued that the HUL approach [

54] transforms heritage into a catalyst for sustainable urban development by integrating it into broader socioeconomic and environmental strategies. King's research [

58] emphasized the importance of cultural-based efforts regarding digital participation and co-creation, demonstrating that digital engagement broadens the scope of heritage value beyond technical conservation to encompass identity, social cohesion, and civic inclusion. Avrami and colleagues [

9] work provided a systematized value-based management. Their work emphasized the importance of recognizing various community stakeholders and the value of contested meanings as an integral part of sustainable heritage-based practices. Ababneh recently [

59] revisited the Venice Charter [

60] considering new heritage challenges and emphasizes that contemporary conservation cannot ignore the mediation of digital documentation, interoperability, and community-centered approaches.

The

Art Nouveau Path translates these structures into a contextualized urban environment and DTLE. Aligned with UNESCO's HUL approach [

54], the project incorporates Aveiro's facades into a participatory digital ecosystem where augmented reality content, narrative tasks, and gameplay records integrate documentation and interpretation. Aligned with SDG 11.4 [

5] and the Faro Convention [

4], among other frameworks, the project positions heritage as a collective civic resource accessible to students, teachers, and the community at large. While the project does not aspire to generate exhaustive 3D documentation or conservation datasets, it supports these objectives by creating multimodal records, including videos, augmented reality overlays, descriptive metadata, student questionnaires, and teacher validations. These various resources have been identified as key factors in enhancing the visibility, interpretation, and long-term cultural significance of the city's Art Nouveau architecture.

In essence, the Art Nouveau Path exemplifies the efficacy of modest, educational initiatives in attaining the objectives of both global and European heritage preservation frameworks.

2.2. Art Nouveau as a Cultural Resource and as an Urban Identity Asset

Emerging at the turn of the 20th century, the Art Nouveau artistic movement became one of the most emblematic artistic and cultural movements of the European Modernism [

61]. Conceived as a ‘

Gesamtkunstwerk’, or total work of art [

62], the movement incorporated architecture, decorative arts, graphic design, and urban culture into a unified aesthetic language of floral motifs, undulating lines, symbolic figures, and organic compositions. This ornamental repertoire expressed ideals of progress, modernization, and harmony between art, nature, and everyday life. This is affirmed by Walter Benjamin's work, ‘

Das Passagen-Werk’ [

63], written intensively between 1927 and 1940, but left unfinished.

Studies on this artistic movement [

64,

65] emphasize the movement's dual role: it was cosmopolitan, diffusing internationally through Brussels, Paris, Vienna, Barcelona, and Riga, among many valuable other cities; but it was also regionally distinct, absorbing local traditions, nature-themed inspirations, materials, artists and craft heritage, and also social aspirations.

However, the patrimonialization of Art Nouveau has been uneven [

66]. While certain cities have embraced the style as a core element of their cultural identity and tourism strategies, such as Brussels with its UNESCO-listed townhouses, Paris with its metropolitan facades, and Riga with its Jugendstil ensemble, other contexts have remained comparatively marginal.

In Portugal, Aveiro has one of the most concentrated collections of Art Nouveau facades. This collection has been documented by local researcher Amaro Neves in several works from 1980 to mid-2000 (some listed works available at:

http://ww3.aeje.pt/avcultur/Avcultur/AmaroNeves/index.htm, accessed on 25

th September 2025), and it has been promoted by local associations, such as the ‘

Associação para o Estudo e Defesa do Património Natural e Cultural da Região de Aveiro ‘ [Association for the Study and Defense of the Natural and Cultural Heritage of the Aveiro Region ] (ADERAV). Local initiatives, including the Art Nouveau Museum and the local Art Nouveau Route, have established this architectural collection as a civic landmark and driver of cultural branding. The wrought iron, exquisite tiles, and naturalist reliefs on the facades serve as anchors of identity, connecting the city’s urban fabric to stories of early twentieth-century modernization and bourgeois prosperity.

Despite its value, some heritage researchers argue that treating such facades as mere static monuments reduces their cultural potential [

67]. Choay [

15] critiques the fetishization of patrimony as isolated objects detached from social life and warns against approaches that freeze heritage as aesthetic relics. In contrast, Avrami et al. [

9] emphasize heritage as a dynamic, plural, and contested resource whose meanings evolve through community engagement and values-based management. Similarly, Bandarin and van Oers [

10] argue that urban heritage contributes to social cohesion and resilience when integrated into daily life and civic practices. Recent literature further highlights how digital documentation and interpretation can expand this integration. For example, Petti and colleagues [

24] demonstrate how mobile applications can enhance accessibility for diverse audiences, and Xu and colleagues [

68] and Wang and colleagues [

69] works confirm that gamification can foster sustained engagement with heritage sites by moving beyond passive appreciation.

The Art Nouveau Path conceptualizes the facades of Aveiro as living cultural resources. Rather than presenting them as mere aesthetic surfaces for tourist consumption, the game situates them within a narrative arc that interweaves historical imagery, sustainability themes, and quiz-based challenges. Players are prompted to observe details often overlooked—architectural motifs, inscriptions, symbolic references—and to link these to broader issues such as water scarcity, environmental change, or civic memory. By this approach, the facades are reactivated as urban identity assets that mediate between past and present, architecture and environment, memory and belonging.

This approach is also consistent with educational perspectives. The

Art Nouveau Path is consistent with situated learning theories and place-based pedagogy by anchoring learning in real facades. The facades of Aveiro’s Art Nouveau heritage, when mediated through AR, function as a potential pedagogical interface bridging formal curricula, urban experience, and civic values [

70]. Therefore, the Art Nouveau heritage becomes not only an asset but also a multimodal learning environment, offering opportunities for interdisciplinary connections across different fields as History, Natural Sciences, Politics, Geography or the Arts.

In essence, the repositioning of Art Nouveau as both a cultural resource and as an urban identity asset supports the reinterpretation of the Aveiro’s Art Nouveau facades, transcending their mere aesthetic value. Within the Art Nouveau Path, these facades and monuments become interactive anchors of memory and identity, of learning, and sustainability and sustainable discourses, demonstrating how heritage can simultaneously sustain cultural identity and pride, support innovative interpretation, and generate lightweight nevertheless meaningful contributions to long-term preservation.

2.3. Extended Reality for Heritage: Augmented Reality as a Primary Approach

In recent years, XR technologies, comprising AR and VR, have increasingly permeated the heritage field [

27]. These methodologies have been applied to a variety of disciplines, including documentation, reconstruction, interpretation, and education, resulting in a substantial body of research [

27,

32,

33,

34]. While VR offers immersive reconstructions that transfer users into simulated environments, AR distinguishes itself by enabling

in situ mediation. This mediation refers to the layering of digital content directly over existing sites, facades, and artifacts without displacing participants from the physical context. These features position AR as a particularly suitable medium for the visualization and digital preservation of urban heritage. In this context, the interpretation of cultural and historical assets must be balanced with the demands of daily life, education, tourism, and conservation efforts [

10,

27,

54].

Research consistently highlights the potential of AR for accessibility, engagement, and learning. Design studies emphasize the importance of narrative coherence between overlays and the physical context, as well as gamification strategies that scaffold observation and multimodal content that address diverse audiences [

11,

33,

71]. Concurrently, another line of research demonstrates that AR can directly support conservation practices. For example, Ling and colleagues [

72] demonstrate how AR visualizations can inform restoration interventions and monitor deterioration processes. Additionally, Sertalp and Sütcü’s work [

73] reveal that contextual overlays can digitally preserve historical layers even when physical materials are at risk. Both Abdelmonem and colleagues’ [

2], and Pervolarakis and colleagues’ works [

74] document cases in which mobile AR reduces the physical strain on heritage sites by providing digital alternatives for exploration and preservation.

Beyond individual case studies, recent reviews emphasize that AR is now part of a growing digital heritage toolkit, not just an experimental novelty. For instance, Petti’s team [

24] contend that AR promotes inclusivity by offering multisensory channels of engagement. Meanwhile, Maietti and colleagues [

75] and Angelis and colleagues’ [

30] works connect AR to semantic and geospatial logics, demonstrating how overlays can be linked to broader information systems. Research focused on education further demonstrates that AR fosters active, inquiry-based learning, in which participants construct knowledge through observation, hypothesis, and reflection [

76,

77].

The Art Nouveau Path exemplifies this convergence by applying AR as a lightweight preservation and mediation practice within a mobile game. Instead of producing exhaustive 3D scans or digital twins, the project shows how spatially anchored overlays, archival images, and videos can enrich facades in situ. By linking architectural details, floral reliefs, and wrought iron balconies, to historical narratives and sustainability themes, the project shows how AR can transform observation into situated interpretation. In this sense, the overlays serve as interpretive tools and vehicles for digital documentation and cultural valorization, ensuring that urban heritage is incorporated into preservation and educational agendas.

In this work, empirical evidence supports this mediating role. Teachers’s validations (T1-VAL and T1-R) emphasize AR’s ability to encourage critical observation and interdisciplinary connections [

52,

53]. Student data from S1-PRE, S2-POST, and S3-FU indicate that AR-based interactions increased interest in heritage and sustainability. Follow-up questionnaires revealed that students retained knowledge of architectural details and reflected on their relevance to broader issues of preservation and urban identity. These findings align with literature, positioning AR as an interpretive and preservative technology.

In short, AR on the Art Nouveau Path is not a technical conservation tool for monitoring or material repair. Rather, it functions as a mediated preservation strategy by documenting facades in digital formats, amplifying their cultural value through narrative and gamified observation, and generating empirical records of engagement that contribute to the long-term sustainability of Aveiro’s Art Nouveau heritage.

2.4. Semantic and Geospatial Logics in Heritage Data

The sustainability of digital heritage depends not only on the production of digital representations but also on how these representations are structured, connected, and made interoperable. Semantic and geospatial infrastructures have therefore become central to contemporary approaches to heritage documentation and preservation. Pivotal work like the CIDOC-CRM [

19], later developed by others researchers (available at:

https://cidoc-crm.org/, accessed on 24

th September 2025), and converted as an International Standard (ISO 21127:2023) (

https://www.iso.org/standard/85100.html, consulted on 24

th September 2025) establishes a common vocabulary for describing cultural heritage entities, events, and relationships in museums, archives, and built environments. According to Moraitou and colleagues [

12] work, semantic and graphical knowledge models enable interoperability, advanced queries, and long-term reuse. This ensures that heritage data can circulate between institutions and platforms without losing context or meaning.

Geospatial infrastructures complement semantic approaches by providing the spatial foundation necessary to link heritage data to territory and context. Archaeological and architectural studies are increasingly adopting geographic information system (GIS)-based resources to map sites, analyze spatial relationships, and construct narrative cartographies [

13]. Caquard [

26] noted in earlier researches that narrative cartography transforms maps from simple indexation tools into storytelling instruments. Such geographical representations can weave in multiple historical, cultural, and social threads. Frequently, these frameworks are aligned with GIS platforms, bridging detailed architectural data with broader urban analysis [

78].

These platforms align with broader agendas for linked open data and semantic enrichment. In these agendas, heritage datasets are connected to wider knowledge ecosystems rather than being siloed within isolated repositories. As stated by Maietti and colleagues [

75] and Angelis and colleagues’ [

30] works, semantic trajectories and augmented metadata can organize visitor navigation and comprehension in different locations, enhancing continuity between tangible experiences and digital repositories. This ensures that semantics and geospatial reasoning serve as cultural tools that promote unity, clarity, and integration, transcending basic technical functions.

Even projects operating at smaller scales can align with these principles by implementing proportionate solutions. The Art Nouveau Path demonstrates how a lightweight approach can incorporate semantic consistency and geospatial anchoring. Rather than implementing full CIDOC-CRM integration or GIS stacks, the MARG -controlled vocabularies (like architects’ names, construction dates, and stylistic features), consistent descriptors (materials, motifs, and symbolic references), and georeferenced navigation through eight POIs. This approach ensures that each facade is framed within a coherent, structured narrative opening it to potential future integration with semantic or GIS infrastructures.

Moreover, the MARG's design is explicitly spatial. The 36 quiz-type questions are linked to specific locations in Aveiro's historic center, and the trajectory between these locations are part of the interpretive experience. This spatial organization corresponds with narrative cartography, wherein urban navigation supports as an educational and documented process. The physical path and the MARG's narrative create a semantic link among location, content, and activity, facilitating analysis of user interpretations, connections, and recollections of heritage through the path.

This exemplifies how the Art Nouveau Path mobilizes semantic and geospatial logic, even in educational interventions. By combining lightweight descriptors, map-based navigation, and narrative structuring, the Art Nouveau Path contributes to the broader effort of ensuring that heritage data is collected, contextualized, coherent, interoperable, and ready to be integrated into the expanding digital heritage ecosystem.

2.5. Smart Heritage Agendas, Interoperability, and Long-Term Preservation

The principle of smart heritage has emerged to portray the convergence of cultural heritage alongside digital ecosystems, identified by their compatibility, openness, and cooperative governance. Within the European context, instruments like the Common European Data Space for Cultural Heritage [

57] and the Twin it! 3D for Europe’s culture campaign (available at:

https://pro.europeana.eu/page/twin-it-3d-for-europe-s-culture, accessed on 24

th September 2025) express the expectation that cultural assets be documented with high quality, shared in interoperable formats, and reused across domains ranging from education to tourism and scientific research. These initiatives reflect the principles of FAIR data management [

20], which stipulate that data must be findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable. This establishes a standard for curating and preserving heritage datasets over time.

Digital preservation requires more than technical storage, according to discussions among experts. Niccolucci [

21] and Moullou and colleagues’ work [

22], for example, argue that these resources sustainability depends on treating datasets as maintained cultural resources with versioning, provenance, and governance mechanisms that ensure continuity across technological shifts. In this perspective, interoperability is not merely a technical aspiration but a condition for heritage data to function within broader cultural ecosystems, linking archives, museums, built heritage inventories, and community-generated resources. Smart heritage is about more than just digitizing assets, since it is also about integrating them into long-term plans for access, governance, and participation.

The Art Nouveau Path addresses these issues with a lightweight but structured model of data production and preservation. While it does not aim to create full-scale digital twins or exhaustive repositories, the project generates multimodal outputs that align with smart heritage principles such as:

(i) Multimedia documentation, such as archival photographs, AR overlays, videos, and narrative descriptors, records and re-presents Aveiro’s facades in enriched formats;

(ii) Empirical datasets, regarding that gameplay logs capture group decisions and interactions;

(iii) questionnaires that are administered before, immediately after, and months following gameplay (S1-PRE, S2-POST, S3-FU);

(iv) teacher validations and observations (T1-VAL, T1-R, T2-OBS); and,

(v) narrative structures, since curated tasks across eight POI link buildings and monuments, places, historical narratives, and sustainability themes into a consistent storyline.

These outputs constitute a lightweight form of digital heritage governance. They are internally consistent, reflexively documented, and open to potential reuse in research, education, or cultural programming. Importantly, they preserve the facades as architectural objects and the processes of engagement and interpretation, such as how participants observe, learn, and connect urban details to broader values. Accordingly, the Art Nouveau Path shows that even small-scale interventions can contribute to smart heritage agendas by combining documentation with pedagogical and civic elements.

By foregrounding interoperability and openness as guiding principles, the broader project positions its datasets as cultural resources that can outlive the immediate educational context. While not comparable in scale to national digitization campaigns, the Art Nouveau Path illustrates how smart heritage practices can be embedded in educational games and community projects, ensuring that preservation is not confined to experts but distributed across actors and scales.

2.6. Synthesis

The theoretical framework outlined above frames the Art Nouveau Path at the intersection of international preservation agendas, stylistic and urban identity discourses, technological innovation, semantic infrastructures, and smart heritage practices. Across these five strands stands a common logic: cultural heritage is no longer conceived as static monuments but as dynamic cultural ecosystems requiring mediation, documentation, and governance in digital and material domains.

As previously stated, international frameworks articulate heritage as a driver of sustainability and resilience. Meanwhile, European initiatives underscore the importance of interoperability, openness, and reuse. In this context, Art Nouveau is not merely an architectural style, but a living cultural resource that anchors local identity in Aveiro while contributing to broader discussions of patrimonialization and urban culture. Extended reality, particularly augmented reality, enables in-situ mediation that enhances interpretation and preservation. This demonstrates how overlays and multimodal narratives can transform facades into interactive cultural anchors.

Semantic and geospatial logics provide structuring principles for coherence and integration, ensuring that even lightweight projects align with CIDOC-CRM, GIS, and narrative cartography traditions. Finally, smart heritage agendas establish the expectation that all cultural data, whether produced by national institutions or local projects, should be managed consistently, reflexively, and openly. The Art Nouveau Path meets this expectation by producing datasets that document not only facades, but also the processes of learning and engagement. This links heritage preservation with education for sustainability.

4. Findings

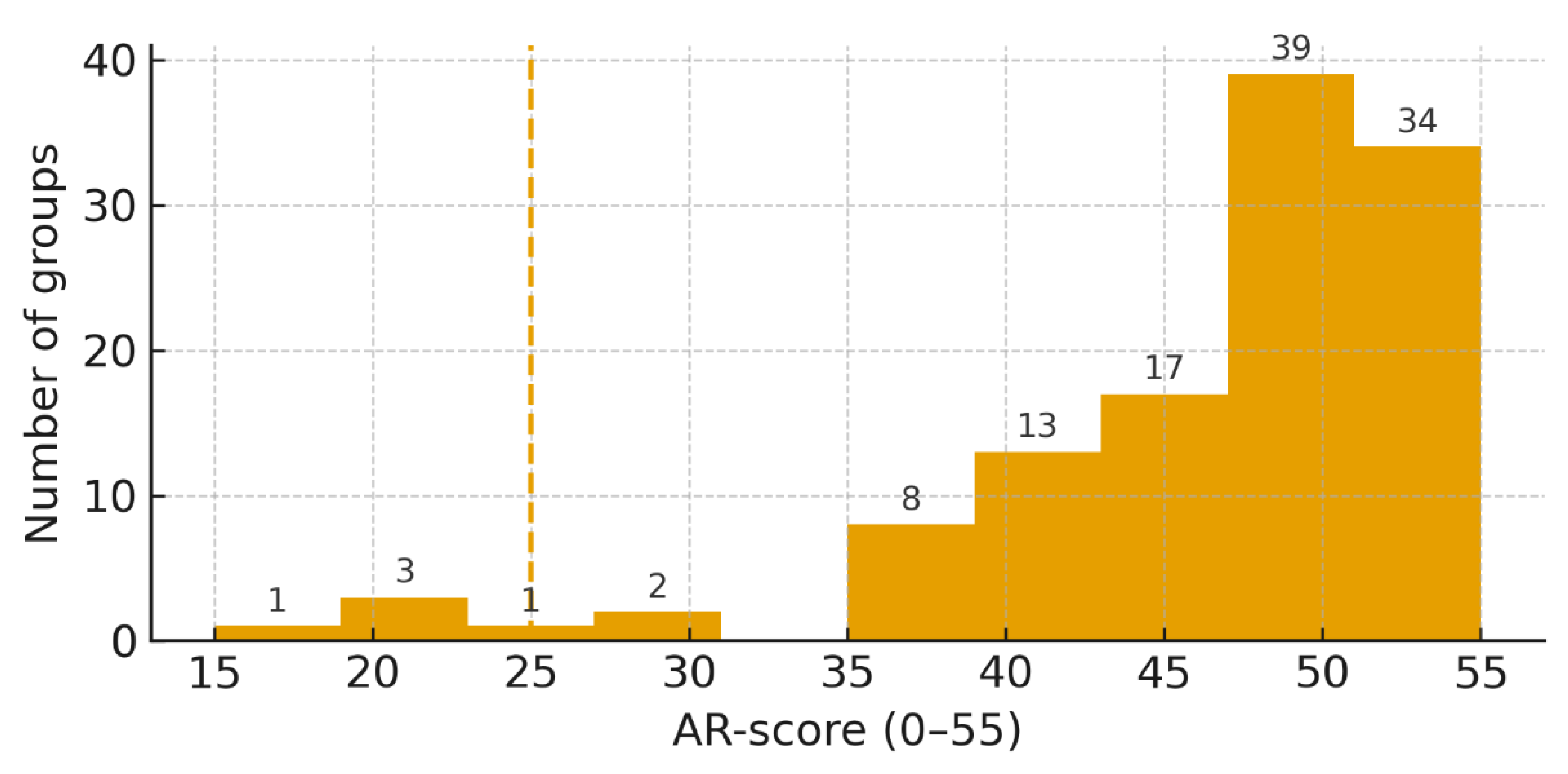

This section presents findings from GCQuest questionnaires (GCQuest-S1-PRE, GCQuest-S2-POST, GCQuest-S3-FU), gameplay logs from 118 collaborative groups, and T2-OBS teachers’ questionnaires.

4.1. Cross-Source Overview and Analytic Rationale

This subsection presents the cross-source results that establish the repeated cross-sectional pattern of change across S1-PRE, S2-POST, and S3-FU. Subsequent subsections contain detailed thematic and specific analyses.

Prior to the MARG’s implementation, it was conducted a validation with 33 in-service teachers (T1-VAL and T1-R). These validations enabled to assess and establish both curricular alignment and interpretive coherence for the

Art Nouveau Path MARG across multiple curricular areas, and a specific History, Natural Sciences, Visual Arts, and Citizenship assessment. This process analysis outputs are exclusively used as inputs to model and implement dynamics, considering that comprehensive results have been previously presented [

52,

53].

The current work analysis focuses on student-generated evidence, in-app gameplay logs, and in-field teachers’ observations collected under the implementation. A total of 439 students, organized in 118 collaborative student groups, produced 4,248 group-item responses across 18 field sessions, accompanied by 24 teachers who completed structured observation forms (T2-OBS).

The MARG’s implementation encompassed a total of 36 items, including 11 AR-based tasks and 25 non-AR tasks. The latter category included seven knowledge-check items, 12 multimedia prompts (static archival/photo/text without AR overlay), and six local-analysis items. The complete

Art Nouveau Path MARG is available at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16981235.

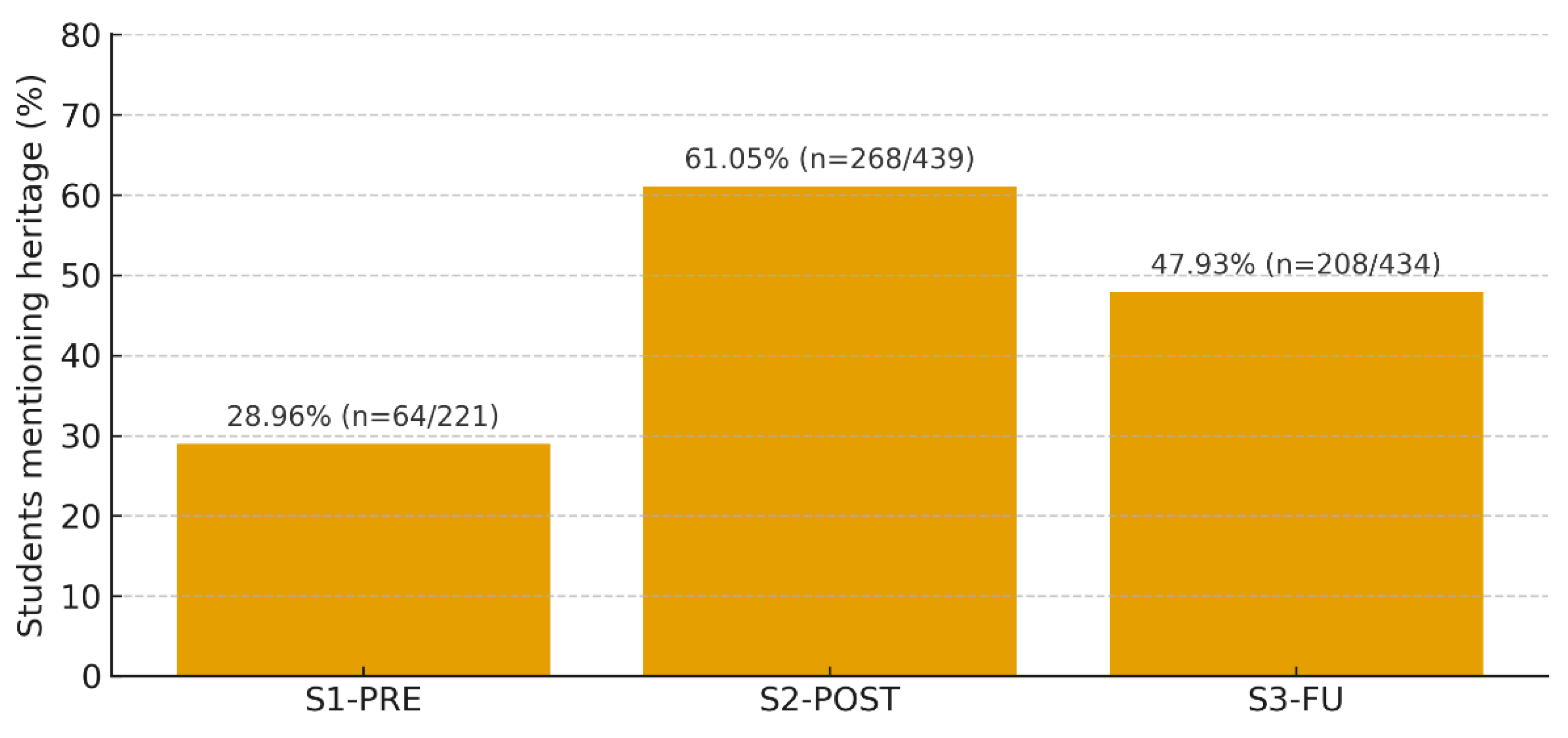

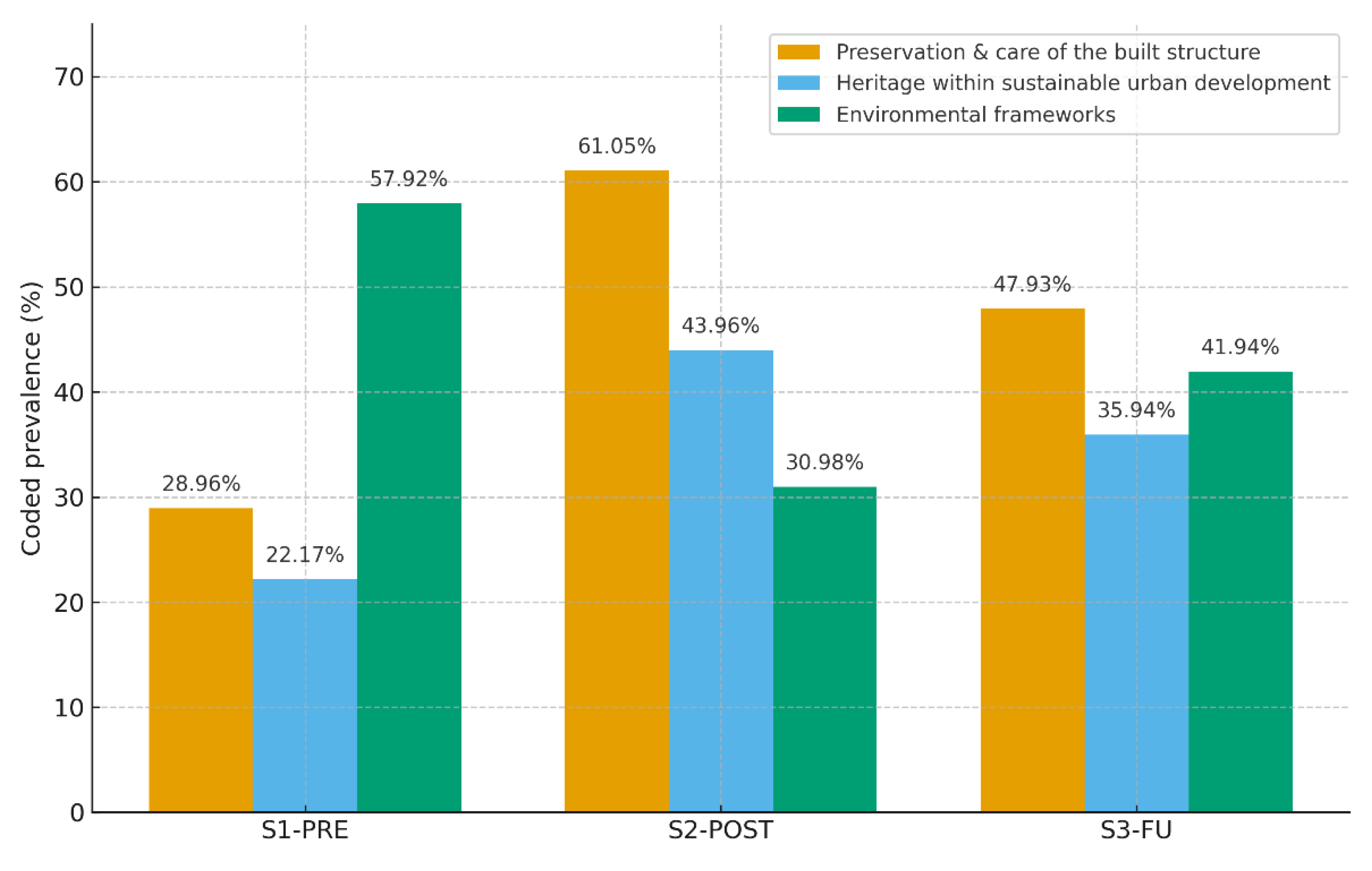

Baseline conceptions positioned heritage preservation as marginal within sustainability. At the baseline (GCQuest-S1-PRE, N = 221), 28.96% of students (n = 64) explicitly associated sustainability with cultural heritage, while most answers were framed in exclusively environmental terms; 14.03% (n = 31) did not provide a clear response. These results frame S1-PRE as a heritage-oriented baseline rather than an outcome instrument.

Immediately following gameplay (GCQuest-S2-POST, N = 439), references to heritage preservation more than doubled to 61.05% (n = 268), a plus 32.09 percentage-point increase over baseline (

Figure 8). In the subsequent assessment (GCQuest-S3-FU, N = 434), mentions declined but remained above baseline at 47.93% (n = 208), indicating an 18.97 percentage-point increase.

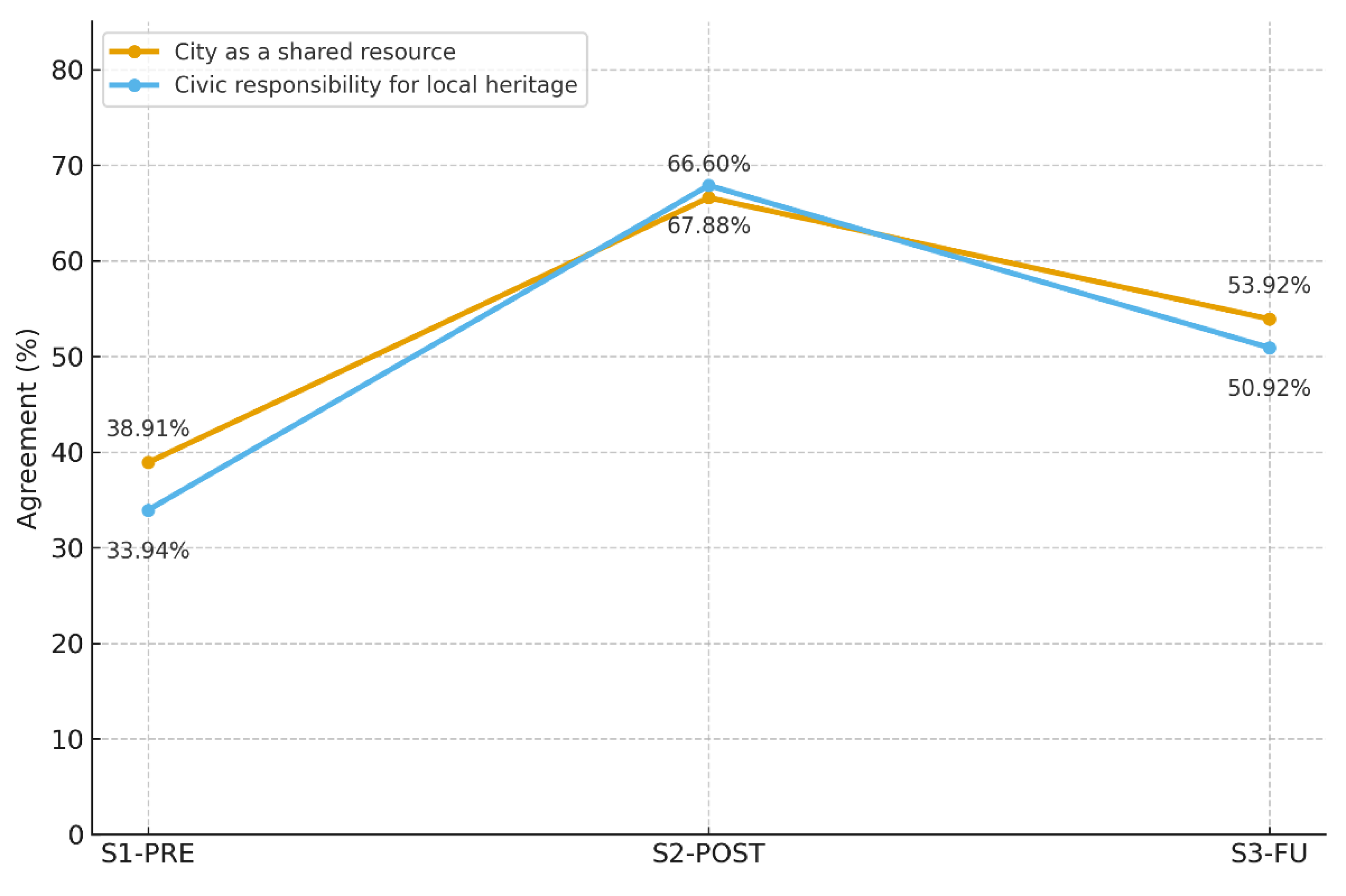

Dichotomous indicators show growth across waves. At baseline, related proxies aligned with items of interest increased significantly in S2-POST, and in S3-FU the construct was explicitly measured by A.2.4 (“

civic responsibility for local heritage,” 50.92%) and A.2.5 (“

city as a shared resource,” 53.92%).

Figure 9 summarizes these patterns; the full mapping of labels and items is in

Appendix B.

Open-ended responses corroborated and nuanced these shifts. Thematic analysis confirmed a reweighting of sustainability discourses toward heritage preservation. Three non-mutually-exclusive categories were salient and evolved consistently across phases: (i) preservation and care of the built structure, 28.96% (n = 64) at baseline, 61.05% (n = 268) after the game, and 47.93% (n = 208) at follow-up; (ii) heritage within sustainable urban development, 22.17% (n = 49), 43.96% (n = 193), and 35.94% (n = 156); and (iii) environmental frameworks, 57.92% (n = 128) at baseline, 30.98% (n = 136) after the game, and 41.94% (n = 182) at follow-up (see

Figure 10). This coexistence suggests a pattern of integration rather than substitution. Illustrative examples include: “

Sustainability also means not letting the old facades fall apart; they are part of our city.” [S2-POST]; “

Taking care of buildings and not just nature, both matter for the city to last.” [S2-POST]; and “

We should maintain these houses; it is sustainable because it preserves culture and avoids waste.” [S3-FU].

Teacher observations corroborated the same trend. In 58.33% of the observation forms (14 of 24 T2-OBS), teachers identified spontaneous discourse on preservation, often prompted by overlays juxtaposing archival photographs with current facades. Micro-dialogues such as “we should protect this” and “it would be unfortunate if this broke” were frequently recorded.

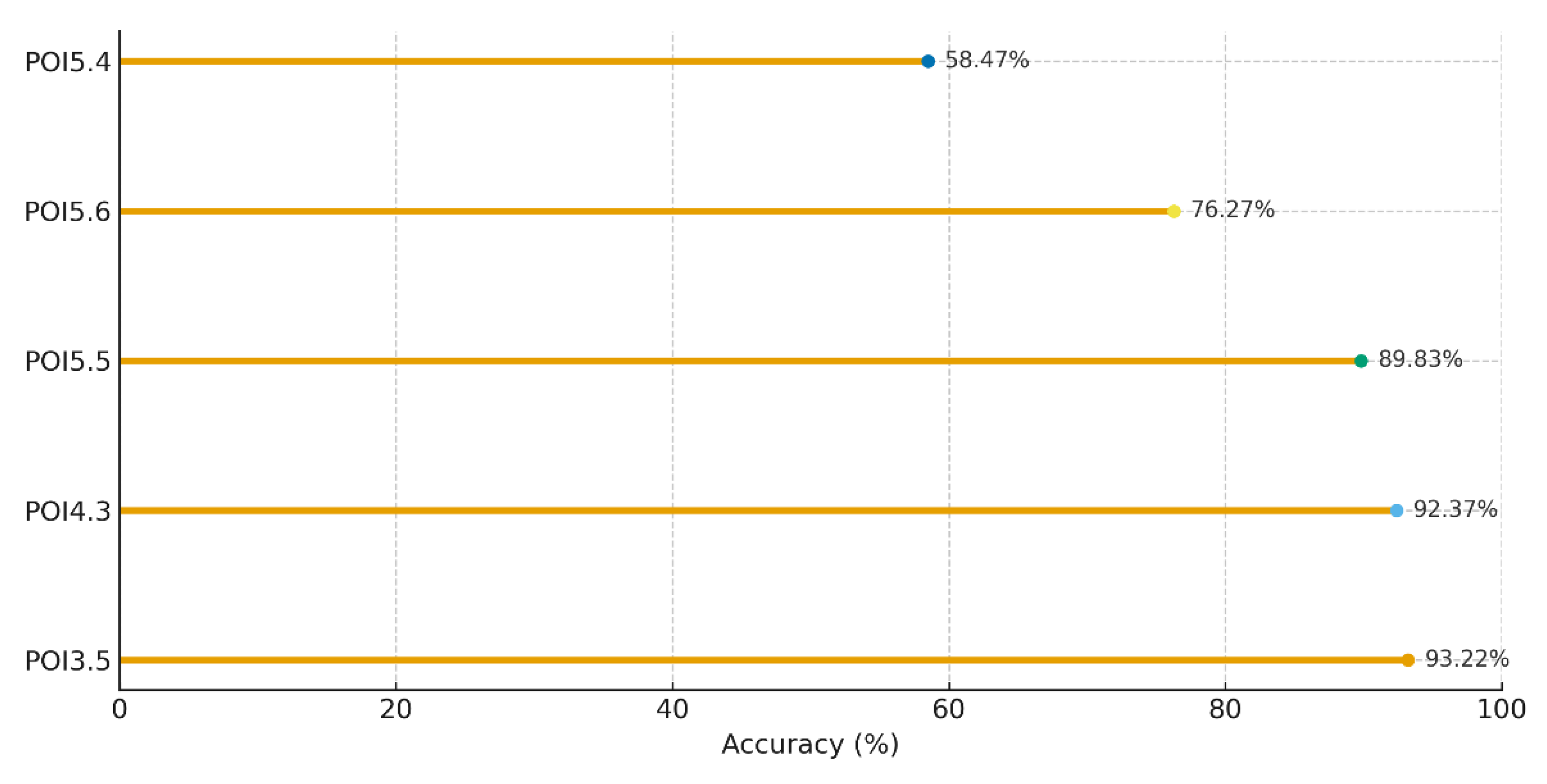

Item-level performance illustrated the same heterogeneity. Using the gameplay logs from 118 groups, the weakest preservation-framed item was POI5.4 at 58.47% correct (69/118). In contrast, the set POI3.5, POI4.3, POI5.5, and POI5.6 yielded 93.22% (110/118), 92.37% (109/118), 89.83% (106/118), and 76.27% (90/118), respectively, with a cluster mean of 87.92% and SD of 7.90, informing the prioritization of on-site interpretive prompts where students historically confuse restoration with repainting, as presented in

Figure 11.

The data demonstrates both the scale and the persistence of the observed changes. The salience of preservation exhibited a marked increase from baseline to post-intervention, with a 32.09 percentage-point rise, while partial retention demonstrated an 18.97 percentage-point rise at follow-up. The gains encompassed a triad of objectives: preservation, civic responsibility, and the conceptualization of the city as a shared resource. Notwithstanding the deterioration of post-test gains over time, preservation remained above the baseline, thereby indicating short- to medium-term internalization.

4.2. Art Nouveau as a Cultural Resource and Urban Identity Asset

The

Art Nouveau Path posits that Art Nouveau facades and monuments did not emerge as inert monuments, but rather as cultural anchors that served to mediate identity, memory, and belonging [

15,

88,

89,

90]. A thorough examination of the extant data, encompassing student questionnaires, open-ended responses, gameplay logs, and teacher observations, unveils four recurrent categories that manifest with high frequency. The categories encompass the recognition of architectural elements, the establishment of a connection to civic identity, the cultivation of affective pride and belonging, and the conceptualization of heritage as a living resource.

4.2.1. Thematic Categories from S1-PRE, S2-POST, and S3-FU

Open-ended responses in S1-PRE resulted in four interconnected categories that remained visible on S2-POST, and S3-FU. The category labels and prevalence are presented in

Table 2.

These categories reveal a layered shift: from noticing architectural motifs (C1) to embedding them within civic identity (C2), affective pride (C3), and the recognition of heritage as a dynamic resource for sustainable cities (C4).

4.2.2. Quantitative Patterns from S1-PRE, S2-POST, and S3-FU

At the baseline (GCQuest-S1-PRE, n = 221), only 31.22% (n = 69) of students spontaneously mentioned facades or decorative details when reflecting on sustainability and the city, with most answers centering on natural resources. Following the conclusion of the gameplay phase (GCQuest-S2-POST, n = 439), this proportion increased to 71.98% (n = 316), with frequent mentions of architectural details (41.00%, n = 180), wrought-iron balconies (35.99%, n = 158), and tiles (28.02%, n = 123). In the subsequent study (GCQuest-S3-FU, n = 434), the qualitative coding of open-ended responses revealed that 61.06% (n = 265) explicitly mentioned architectural details (Noticing category), indicating substantial recall of specific features. In contrast, in the closed item A.2.1 [

Do you still remember any details, buildings or areas of the city you visited during the game?]

, 81.94% (n = 356; N = 434) of the participants reported remembering details in general, indicative of broader declarative recall. These complementary data signify both generic and concrete forms of memory retention, as presented in

Table 3.

The S3-FU results confirm both generic and concrete recall of architectural features above baseline, consistent with gameplay accuracy and teachers’ observations.

4.2.3. Triangulation with T2-OBS and Gameplay Logs regarding Art Nouveau POIs

The reliability of these findings was further substantiated by teacher observations, which corroborated the observed patterns. In 62.50% of T2-OBS forms (15 of 24), teachers reported overhearing students framing facades as "ours" or "belonging to Aveiro." A substantial proportion of the teachers (54.17%, 13 out of 24) reported observing affective reactions, including enthusiastic pointing, photographing, or verbalized expressions of pride.

The findings were reinforced by gameplay logs (N = 118 collaborative groups; 4,248 group-item responses), which also revealed tensions. At POI4 (Old Agricultural Cooperative), the term "aesthetic repainting" was conflated with "authentic tile preservation," resulting in an accuracy rate of 69.49% (82 of 118 correct). This ambiguity exemplifies how students actively negotiated the boundary between facades as surface appearance and facades as cultural heritage.

The affective and cognitive traces documented across S1-PRE, S2-POST, and S3-FU responses, in conjunction with gameplay logs and T2-OBS field notes, substantiate the hypothesis that Aveiro's Art Nouveau facades, when mobilized through AR mediation, functioned as living resources rather than static monuments.

4.3. Extended Reality for Heritage: Augmented Reality as the Primary Approach

The incorporation of AR within the Art Nouveau Path has emerged as a pivotal catalyst, superimposing interpretive content directly onto the urban landscape and profoundly influencing the way students interacted with facades. The extant evidence, derived from post- and follow-up questionnaires, gameplay logs, and teacher observations, demonstrates three interrelated dynamics:(i) a heightened level of attention is allocated to architectural elements. The integration of AR overlays prompted students to observe elements of the built environment that would have otherwise gone unnoticed, including architectural details, wrought-iron balconies, and tiles; (ii) the implementation of a multimodal and game-based design approach in the educational environment has been demonstrated to promote two key elements: motivated exploration and sustained engagement. In this case, students were encouraged to move attentively through the path, thereby prolonging their focus and generating enthusiasm; and, (iii) the tensions between productivity and authenticity, as well as the challenges posed by distraction, were particularly pronounced. While augmented reality (AR) technology enhanced interpretive depth, it also introduced moments of ambiguity, particularly when students confused surface renovation with heritage preservation.

The significance of AR in its value to function not merely as a technological augmentation but rather as a mediational layer with the potential to profoundly reshape the perceptual and affective experience of heritage is underscored by these dynamics. In this regard, facades emerge as living anchors of sustainability discourse.

4.3.1. Thematic Categories from Open-Ended Answers (S1-PRE, S2-POST, S3-FU)

The reflexive thematic analysis of the open-ended sections of the GreenComp-based questionnaires was conducted, which resulted in the identification of three recurrent categories that articulate how students perceived the role of AR in the

Art Nouveau Path. Percentages indicate the proportion of students whose responses were coded in each category at baseline (S1-PRE), immediately after gameplay (S2-POST), and at follow-up (S3-FU), as presented in

Table 4.

These categories illustrate AR’s role as both an amplifier and a disruptor: it heightened observation and curiosity while also introducing tensions between digital mediation and the embodied experience of place.

4.3.2. AR as a Key Element: Quantitative Patterns from S2-POST, S3-FU, and Gameplay Logs

In the S2-POST (n = 439), 67.88% (n = 298) of students explicitly cited AR as the element that "helped them notice things better" or "helped them see details." At the S3-FU (n = 434), 52.07% (n = 226) of participants restated that AR had a transformative effect on their perception of buildings. As presented in

Table 5, these references underscore the significance of AR in influencing the perception of facades and monuments.

These categories illustrate AR’s role as both an amplifier and a disruptor: it heightened observation and curiosity while also introducing tensions between digital mediation and the embodied experience of place.

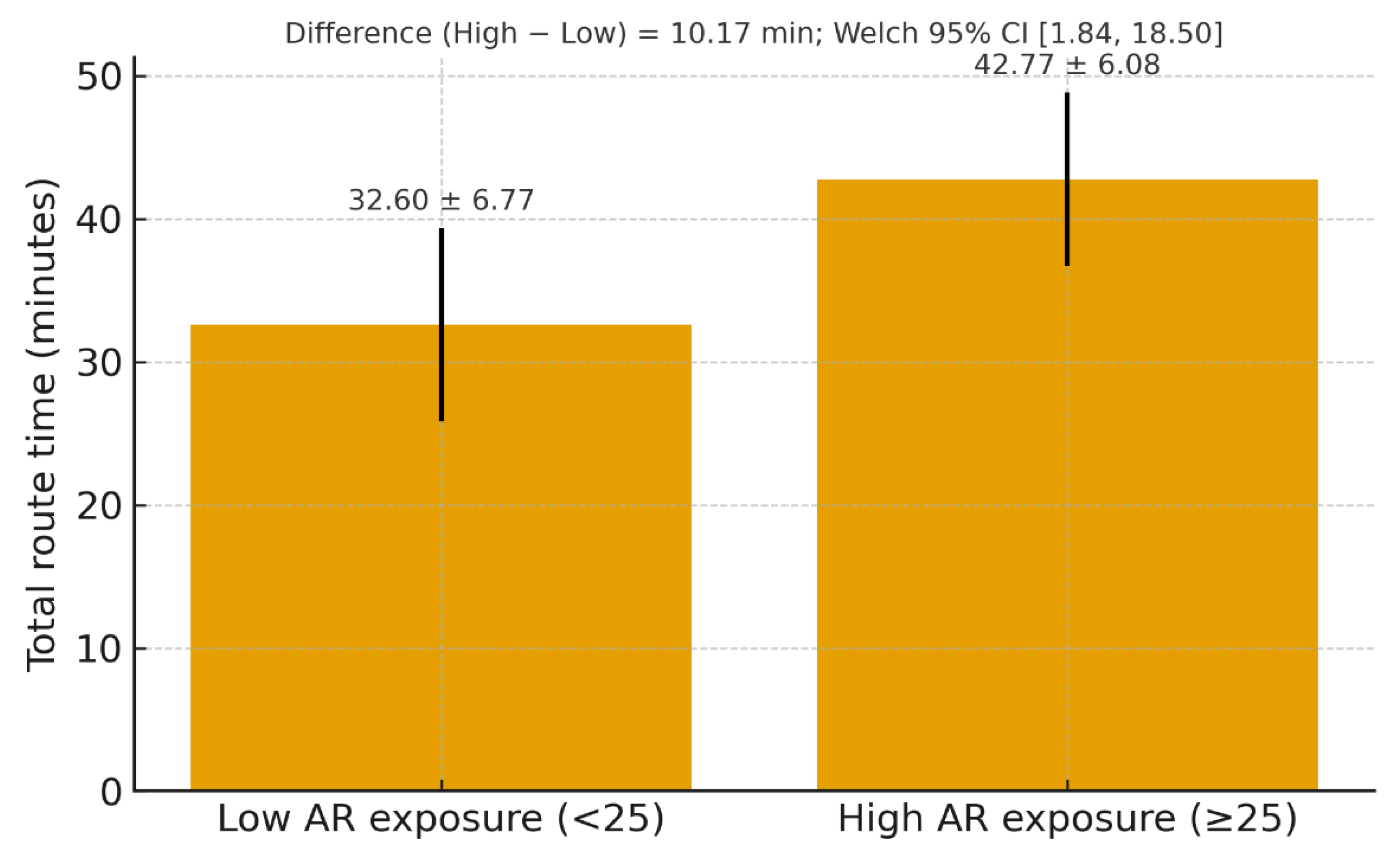

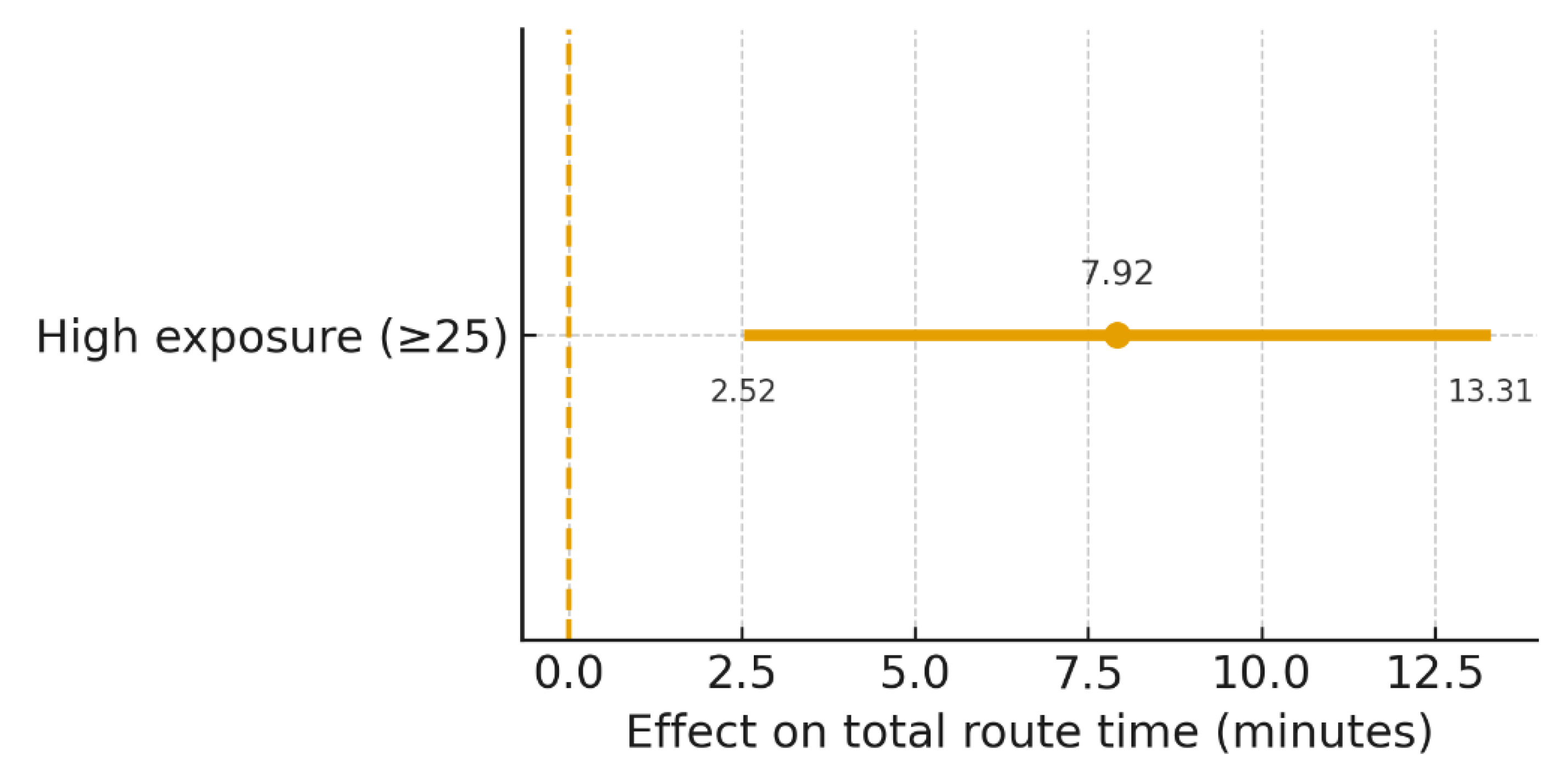

Gameplay records corroborated these self-perceptions. AR items had a success rate of 81.00% versus 73.00% for non-AR items. The ranges are reported: 81.00% [95% CI 78.75%–83.01%; n items = 11; n groups = 118] and 73.00% [95% CI 71.39%–74.59%; n items = 25; n groups = 118]. At the group level, the average exploration time was 42.77 minutes (SD 6.08) versus 32.60 minutes (SD 6.77).

Table 6 presents a comparative analysis of gameplay metrics.

The AR-score was modeled as continuous in OLS with fixed session effects and robust errors with small-sample correction. The results were qualitatively similar to the bivariate contrast, as can be analyzed in

Appendix C.

4.3.3. Triangulation with T2-OBS and Gameplay Logs Regarding AR

Teachers’ observations further substantiated AR's catalytic function. In 83.33% of T2-OBS forms (20 of 24), teachers reported that overlays increased students' attention to facades, often describing learners pointing, comparing digital and material details, and verbally negotiating meanings. Concurrently, 37.50% (9 of 24) of respondents expressed concerns regarding excessive reliance on screens, providing comments such as "some groups focused too much on the phone instead of the building."

This duality is corroborated by the gameplay records. AR tasks demonstrated greater accuracy, 81.00% [95% CI 78.75%–83.01%; n items = 11; n groups = 118], compared to 73.00% [95% CI 71.39%–74.59%; n items = 25; n groups = 118] in non-AR items. The error patterns that emerged from this analysis indicated a notable instance of conceptual confusion, characterized by the erroneous attribution of decorative repainting as original Art Nouveau motifs. These indicate that AR overlays enhance both attention and interpretive depth, but they also introduce risks of screen-centric engagement. The convergence of teacher field notes and gameplay logs underscores the ambivalent role of AR in education. It may be used as an interpretive amplifier that requires meticulous scaffolding to harmonize digital mediation with embodied observation.

4.4. Immediate Post-Game Perceptions from S2-POST

The triangulation of data from teachers’ observations (T2-OBS) and gameplay logs serves to corroborate the categories derived from the student data. The S2-POST questionnaire is available at the project’s Zenodo community page (

https://zenodo.org/communities/artnouveaupath/records/, accessed on 25

th October 2025). This instrument was designed to capture students' perceptions immediately following gameplay, integrating Yes/No indicators, open-ended reflections, and Likert-scale items.

The data indicates a significant shift in the way facades and monuments are perceived, interpreted, and incorporated into broader sustainability discourses. The students exhibited an elevated level of proficiency in recognizing architectural elements and demonstrated an augmented capacity to articulate the interrelationships between preservation, civic responsibility, and the concept of the city as a shared resource.

4.4.1. Dichotomous Items on S2-POST

The binary responses in the S2-POST (N = 439) dataset indicate a high level of approval for the learning approach and a selective curiosity regarding Aveiro's Art Nouveau heritage. Two key items illustrate these patterns. Most of respondents expressed interest in the prospect of learning sustainability through Art Nouveau. However, the level of interest in exploring Aveiro's Art Nouveau specifically was, in comparison, more moderate. As presented in

Table 7, the responses from students are summarized.

The results indicate, in comparison, a distinction. Almost all students’ population demonstrated a recognition of the value of integrating sustainability with Art Nouveau, as evidenced by the findings of the study. The results indicated that 98.45% of the students (n = 432) acknowledged the potential of facades as effective educational entry points. Less, but also the large majority, 94.53% (n = 415) of respondents expressed a desire to continue exploring Aveiro's Art Nouveau specifically. These results demonstrate an overall comprehension of the broader conceptual link between heritage and sustainability, and their engagement with the local case study.

4.4.2. Triangulation Between T2-OBS, S2-POST, and Gameplay Logs

The observations made by the teachers supported the thematic categories that had been previously identified in S2-POST. In 62.50% of the T2-OBS questionnaires (15 of 24), teachers reported dialogues of students overheard framing facades as "ours" or "belonging to Aveiro." A substantial proportion of teachers, specifically 54.17% (13 out of 24), reported observing affective reactions, including enthusiastic pointing, photographing details, and verbalizing pride.

Gameplay logs (N = 118 collaborative groups; 4,248 group-item responses) demonstrated consistently high engagement with detail-recognition tasks (mean accuracy = 83.00%). However, deeper data analysis and cross-checking also unveiled conceptual ambiguities at POI4 (Old Agricultural Cooperative), where respondents exhibited confusion between "aesthetic repainting" and "authentic tile preservation," resulting in 69.49% accuracy (82 of 118 responses were correct).

4.5. Follow-Up Retention and Transfer (S3-FU)

Post-game evidences (from S2-POST) indicates that AR-mediated activities activated facades as cultural interfaces rather than passive backdrops, thereby reframing them as markers of civic identity and everyday cultural resources. A comprehensive review of extant data collection tools, namely, the qualitative data, observational studies, and log files reveals that this place-anchored mediation has been embedded within the discourse on sustainability.

4.5.1. S2-POST and S3-FU Open Responses Analyses

The coding of responses to A.2.1.1 ("

Do you remember a detail, building, or area from the game?") in the follow-up dataset (S3-FU, n = 434) yielded three main categories.

Table 8 provides a comparison of the prevalence with the immediate post-game phase (GCQuest-S2-POST), thereby offering a repeated cross-sectional perspective on the evolution of heritage engagement over time.

A repeated cross-sectional analysis yielded observations indicating an attenuation in detail recognition, concomitant with an augmentation in experiential transfer. This finding may signal a transition from a focus on detail recognition to the cultivation of civic and everyday sensibilities [

97,

98].

Regarding these results, follow presents students’ illustrative examples regarding this repeated cross-sectional comparison: “We should maintain these houses; it is sustainable because it preserves culture and avoids waste.” [at S3-FU], linking preservation practices with both cultural continuity and resource efficiency; “I want to show my parents what I learned; it makes me proud.” [at S3-FU], reflecting intergenerational transfer and affective pride in local heritage; and, “Since the game, I pay more attention to the facades when I walk in my neighborhood.” [S3-FU], signaling behavioral change, extending attentiveness beyond the game context into daily life.

4.6. Teachers’ Observations and Micro-Dialogues Report

Teachers frequently recorded student micro-dialogues such as "we should protect this" and "it would be a pity if this broke", particularly at facades where AR overlays juxtaposed archival photographs with contemporary views. Logs identified ambiguity at POI4, where distractors blurred the distinction between repainting and authentic tile preservation, yielding 69.49% accuracy (82 of 118). At POI6 (Art Nouveau Museum), an element of hesitation regarding the definition of 'preservation' was also observed; analysis of gameplay logs revealed that the item with the lowest accuracy in relation to preservation, POI5.4, attained 58.47% accuracy, while the preservation set exhibited an average of 82.05% (SD = 15.12). These patterns are in alignment with the accounts provided by the teachers, thus demonstrating the way students navigated the boundary between surface appearance and cultural heritage.

4.7. Triangulation across Questionnaires, Logs, and Teacher Observations

The triangulation of questionnaires, gameplay logs, and teachers’ observations indicates that the

Art Nouveau Path activated facades as cultural interfaces rather than static backdrops [

46]. Students expanded sustainability to include preservation, noticed and remembered architectural details, and reported sharing and revisiting beyond the activity. AR and multimodality strengthened attention and accuracy [

99], while also producing authentic debates about what counts as preservation [

33]. These patterns are consistent with a desirable difficulty profile, although, explicit “civic responsibility” is measured only in S3-FU (A.2.4), while in S1-PRE and S2-POST analysis are used interest proxies (see

Appendix B).

6. Conclusions

This study explored how the Art Nouveau Path fosters sustainability competencies by analyzing gameplay logs, student questionnaires, and teacher observations.

6.1. Main Conclusions

Initially, the heritage context proved to be an effective strategy for ESD. In the S2-POST study, which included 439 participants, an overwhelming majority (98.45%) found the subject of sustainability as explored through Art Nouveau to be intriguing. A substantial majority (94.53%) indicated an interest in further exploring the topic. T2-OBS (N = 24) documented spontaneous "preservation dialogues" in 58.33% of instances, substantiating heritage's function as a mediational tool for sustainability education.

Secondly, the incorporation of multimodality and AR significantly improved user engagement, thereby promoting a constructive challenge. Analysis of the records (N = 118 groups; 4,248 responses) revealed 81.00% [95% CI 78.75%–83.01%; n items = 11] on AR items versus 73.00% [95% CI 71.39%–74.59%; n items = 25] on non-AR items. The mean accuracy in the ‘architectural detail’ subset was 83.00%. High AR exposure was associated with longer route time, with a mean gap of 10.17 minutes (42.77 vs. 32.60). This association is statistically significant in the OLS specification with session fixed effects and small-sample robust errors (p = 0.004; see

Appendix C). In S3-FU (N = 434), 81.94% (at question A.2.1.) recalled building details, with 61.06% explicitly mentioning features (at question A.2.1.1.), indicating desirable difficulty and the need to balance challenge with support.

Thirdly, the retention and transfer of knowledge extended beyond the confines of the classroom. In the S3-FU dataset, 69.35% (at question A.1.2.) reported increased sustainability in their actions, 68.20% (at question A.1.3.) shared ideas with colleagues or family members, and 79.03% (at question A.2.1.) demonstrated a closer attention to architectural details.

6.2. Design Implications for Heritage-Based MARGs

The effectiveness of heritage MARGs depends on intentional multimodality. At each POI, pair a concise historical record (photograph, short video, or audio) with a single, unambiguous prompt and, when relevant, a precise AR overlay that directs attention to the feature under examination. Juxtaposing past and present supports authenticity judgments and reduces ambiguity.

Where feasible, include lightweight metadata (source, date, author) to connect in-situ interpretation with documentation practices and to enable asset reuse. Low-load micro-checks, such as a one-item quiz or a brief justification, reinforce dual coding of verbal and visual information and discourage passive consumption.

It is essential to maintain a coherent narrative throughout the MARG. Replace isolated stops with a coherent arc of opening, discovery, and synthesis or feedback. Recurring motifs gain meaning as they reappear across stops. Sequenced tasks, in which a clue from one site informs interpretation at the next, build continuity and sustain inquiry.

Implementation activities need to be pre-organized. For group work, define a clear synthesis point, such as a square, a familiar street, or a museum entrance. There, each group produces a micro-narrative, for example a captioned photograph or a 30-second audio note that explicitly links identity, authenticity, and preservation to the contemporary city.

It is important to establish a transfer system that is operational daily, extending beyond the designated route. Follow-ups such as identifying and documenting the heritage motifs in the neighborhood or collecting family memories related to specific buildings foster intergenerational bridges and strengthen belonging. A small reusable observation card listing materials, motifs, and conservation clues functions as a heritage-literacy aid. Brief periodic self-reports and, when appropriate, geotagged photographs help monitor the persistence of attentive looking and the occurrence of “preservation dialogues.”

Also, it is important to guide the experience from naked-eye observation to AR and back to naked-eye comparison to counter screen-centricity and privilege in-situ checks of materiality. Overlays should remain restrained and legible, avoiding graphical noise and superfluous animation. Introduce desirable difficulty through graded hints and plausible distractors, paired with a brief “why?” prompt (for example, “Why is this a restoration rather than a repainting?”) to turn ambiguity into interpretive learning.

At last, in the cross-field oh heritage and sustainability domains, the experience must be anchored in international frameworks such as the UNESCO Historic Urban Landscape approach [

54], the Faro’s Convention [

4], and SDG [

5] by using consistent descriptors, identified sources, and reusable formats, even with a lightweight stack. Schools and municipalities can generate interoperable cultural traces, including multimedia records, descriptors, interaction logs, and survey artifacts, aligned with emerging national and international data spaces without requiring full HBIM or digital-twin pipelines. These practices enhance preservation literacy and community attachment, showing that carefully orchestrated AR itineraries can enrich interpretation and sustain civic value with proportionate technical investment.

6.3. Limitations

The evidence presented herein should be interpreted considering several limitations. Firstly, it should be noted that this is a single-case study in one city focused on a specific heritage typology, Art Nouveau facades. This limitation constrains the generalizability of the findings across places, audiences, and heritage categories. Secondly, the conditions surrounding the sampling and implementation process introduce limitations on the external validity of the study. Specifically, classes that were joined through a municipal program during school hours, along with factors such as weather, crowding, and route logistics, were not systematically controlled during the experimental process. Thirdly, the findings are contingent on self-reported data and structured observations; student questionnaires and teacher field notes are vulnerable to social desirability, recall bias, and inter-observer variability. Fourthly, gameplay logs were collected at the group level, which lacked per-student micro-interactions, dwell time per POI, and fine-grained hint-use sequences. This restricted the modeling of attention and individual pathways. Fifthly, the decisions regarding anonymity were in favor of data minimization; however, they impeded panel matching across administrations and precluded moderation analyses by demographics or prior interest. Sixth, the follow-up period was of a relatively brief duration, spanning approximately six to eight weeks following gameplay. Consequently, the extent of long-term retention and the development of civic behaviors remain uncertain. The design of the study did not include a comparison route that was delivered without the application (hereafter, "app") or without augmented reality (hereafter, "AR"). Without a non-AR arm or a crossover condition, the unique contribution of AR and multimodality cannot be isolated from novelty, place-based inquiry, or teacher mediation. Therefore, the estimates are associational rather than causal. The eighth point pertains to the study's placement within an exploratory DBR cycle. It is important to note that there was no pre-registered analysis plan and no multiplicity adjustments typical of confirmatory trials. This aspect of the study necessitates a cautious interpretation of statistical signals. The ninth issue pertains to the delivery of instruments and content in Portuguese, accompanied by a GreenComp-aligned adaptation. However, the evaluation of cross-language invariance and broader transferability remains to be conducted. In the context of data stewardship, a lightweight approach was adopted, characterized by the consistent labeling and georeferencing of assets. However, the implementation of full CIDOC-CRM mapping or HBIM pipelines was not undertaken, a choice that consequently restricts the immediate interoperability with high-fidelity conservation workflows. Consequently, the constraints imposed by the devices and settings may have exerted a significant influence on the observed engagement patterns. In urban public spaces, groups shared a single mobile device, which is subject to factors such as screen glare, ambient noise, and connectivity. These factors have the potential to influence pacing, attention, and the balance between screen-focused and object-focused observation.

6.4. Future Paths

Subsequent iterations should explicitly instrument the route as a research site. The integration of enhanced log analytics, accompanied by fine-grained temporal traces, in conjunction with core multimodal learning analytics, will facilitate a more precise characterization of the evolution of attention and interpretation across points of interest and media. These traces should be systematically triangulated with self-report measures and behavioral indicators, such as on-site actions and hint usage, to strengthen claims about transfer and reduce reliance on perception-based evidence alone.

To expand external validity, future research should implement the design across a broader array of heritage typologies, including industrial, vernacular, and natural contexts. This scaling is best achieved through structured co-creation with teachers, students, and heritage professionals, using iterative design studios to calibrate multimodality, narrative coherence, and cognitive challenge to local curricula and conservation constraints.

Finally, the project's cultural outputs, namely multimedia assets, structured descriptors, and interaction logs, should be curated for interoperability and deposited in European digital-heritage infrastructures. These initiatives facilitate cross-border educational reuse of 3D and AR resources, advance cultural sustainability objectives, and demonstrate how lightweight, school-based interventions can contribute meaningfully to continental preservation ecosystems.

From a methodological perspective, future research endeavors should be designed to include a non-AR comparison or a crossover design, with matched classes and identical prompts on paper. The instrumentation of the application should be adapted to facilitate the capture of anonymized individual taps, dwell time, and hint sequences. Furthermore, the duration of the follow-up period should be extended to range from three to six months, incorporating brief micro-surveys and optional geotagged traces. The collection of minimal, ethics-approved demographics is essential for the testing of moderation. Additionally, pre-registration of confirmatory analyses and adjustment for multiple comparisons is necessary. Finally, the mapping of descriptors to CIDOC-CRM classes should be conducted, while piloting a thin GIS layer to assess the efficacy of plug-and-play interoperability.