Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

05 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Botanical Description of Black Pepper

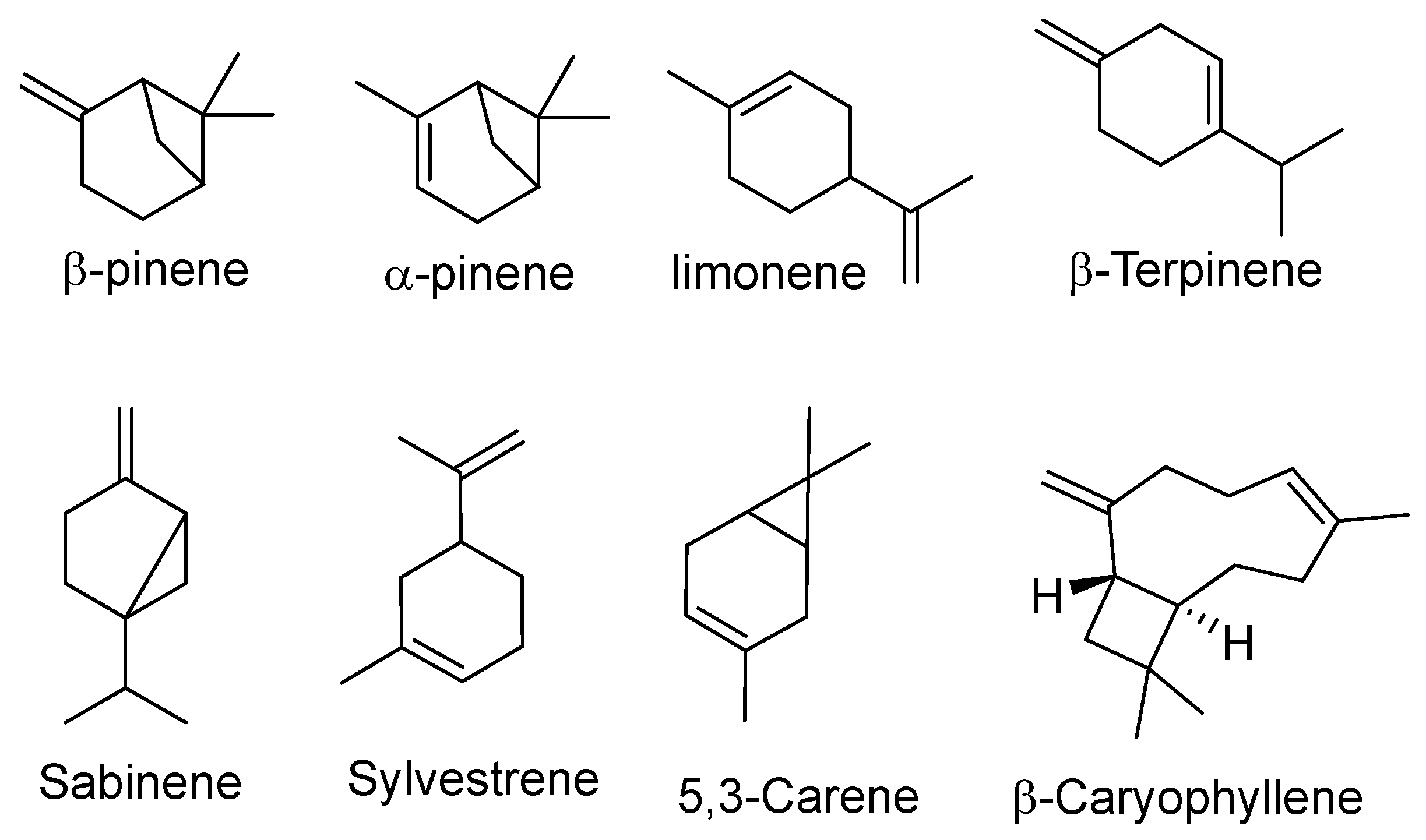

3. Chemical Composition and Major Classes of Compounds in Piper nigrum

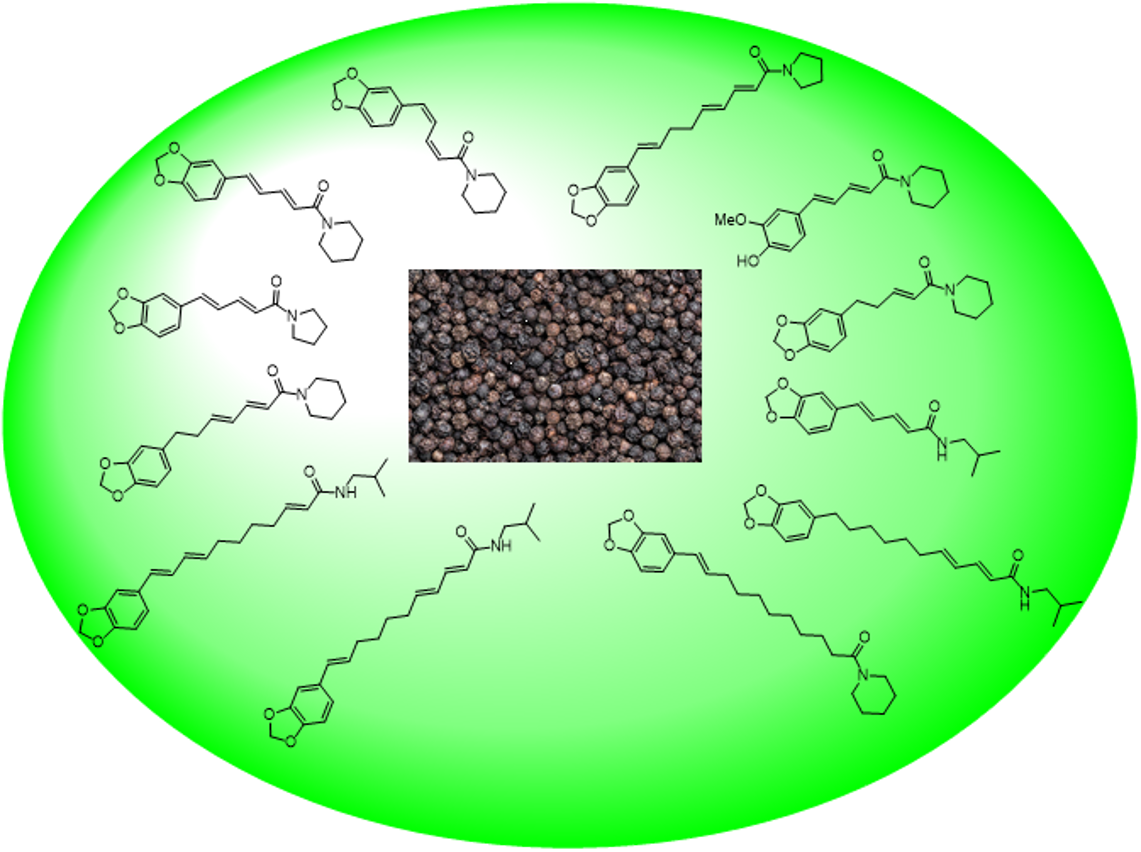

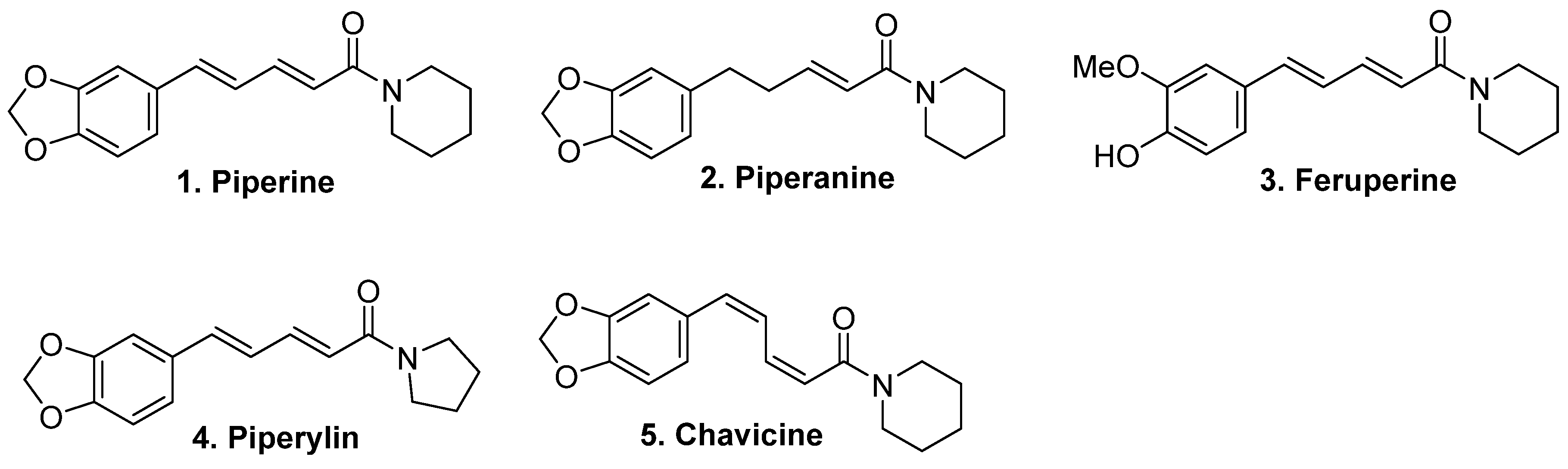

B. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites

4. Extraction and Isolation Techniques of Phytochemicals from Piper nigrum

5. Chromatographic and Spectroscopic Identification Methods

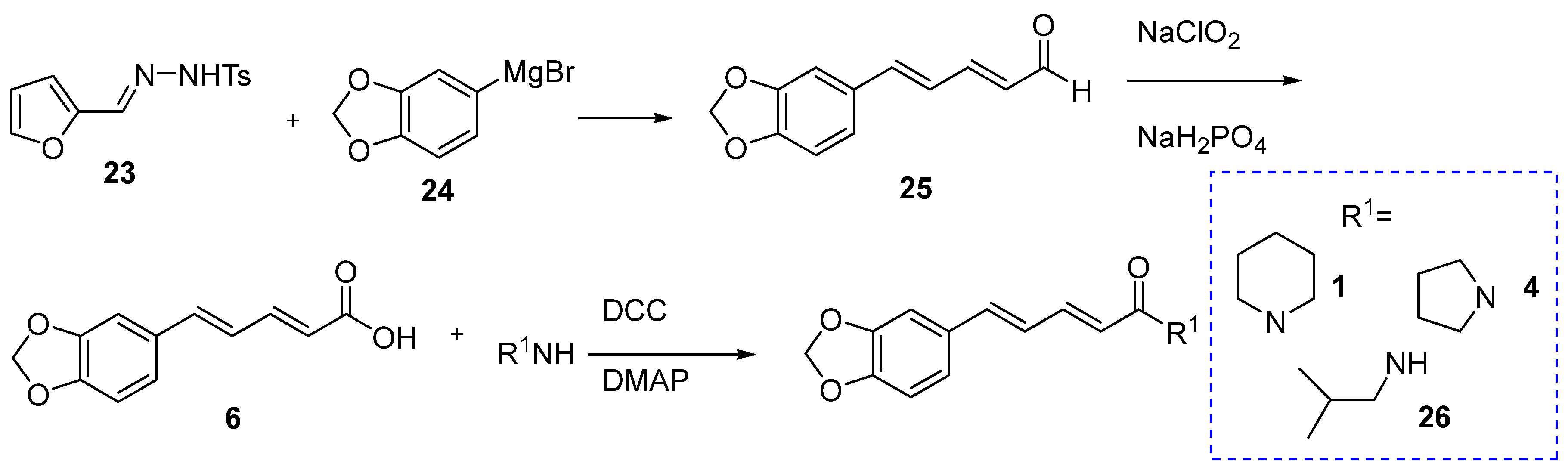

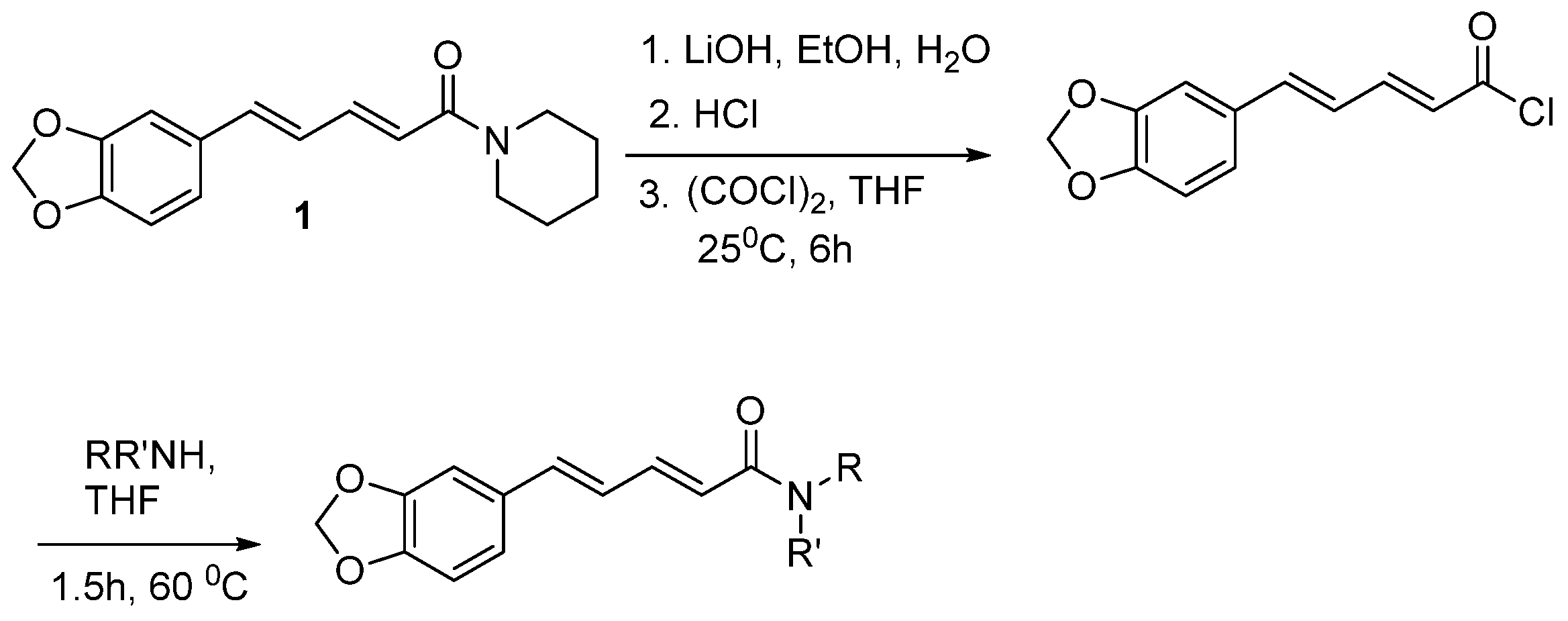

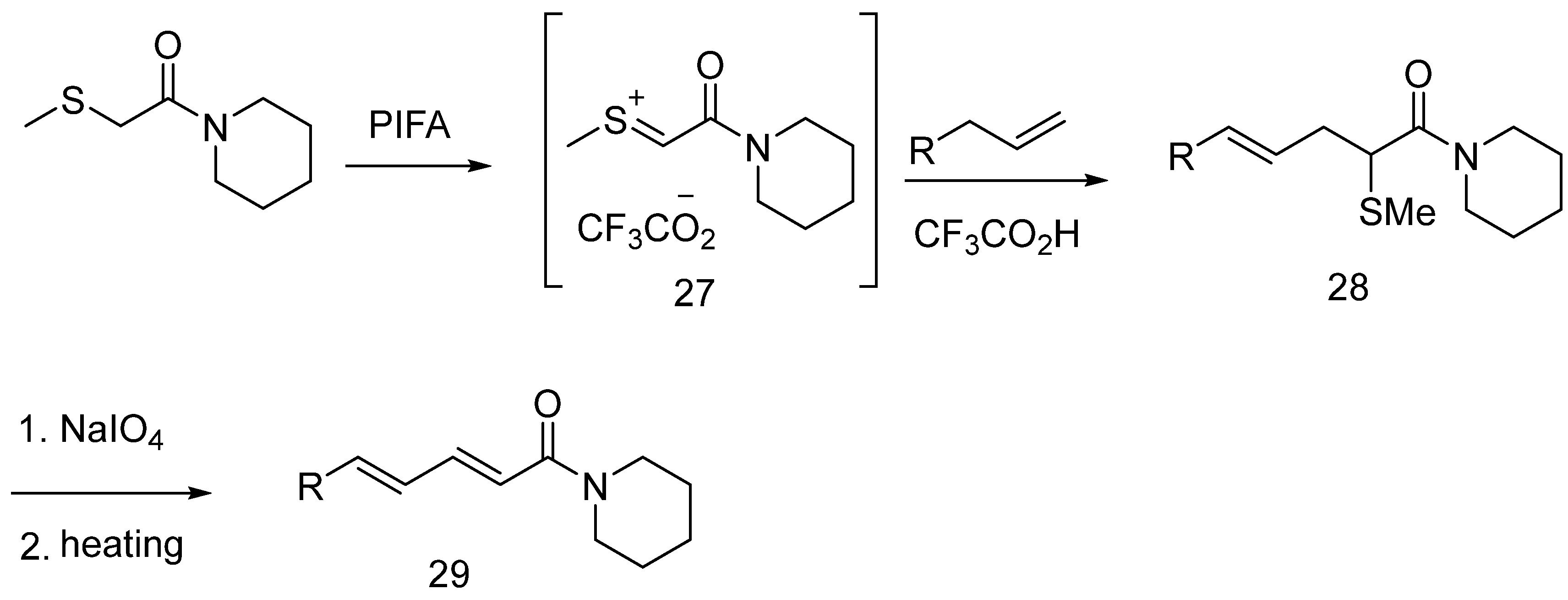

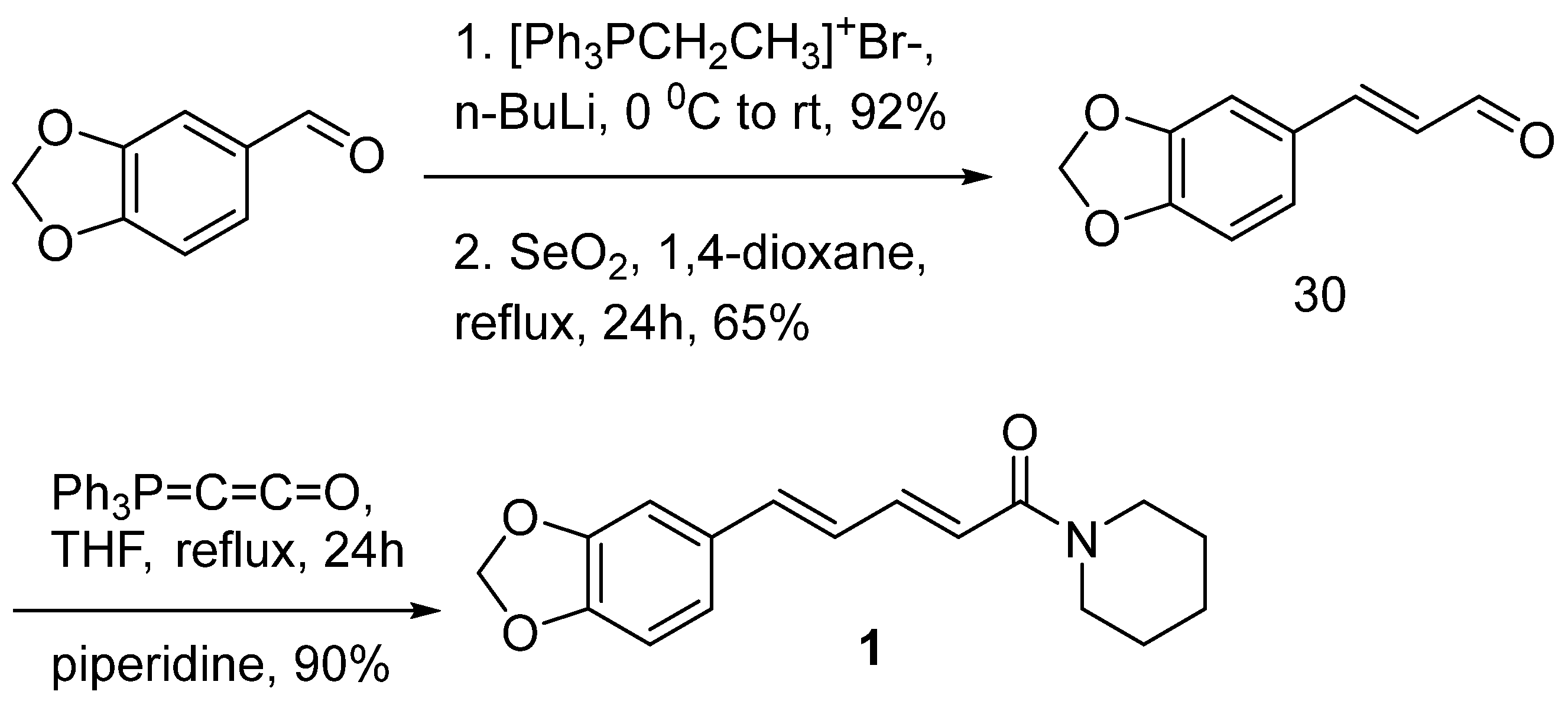

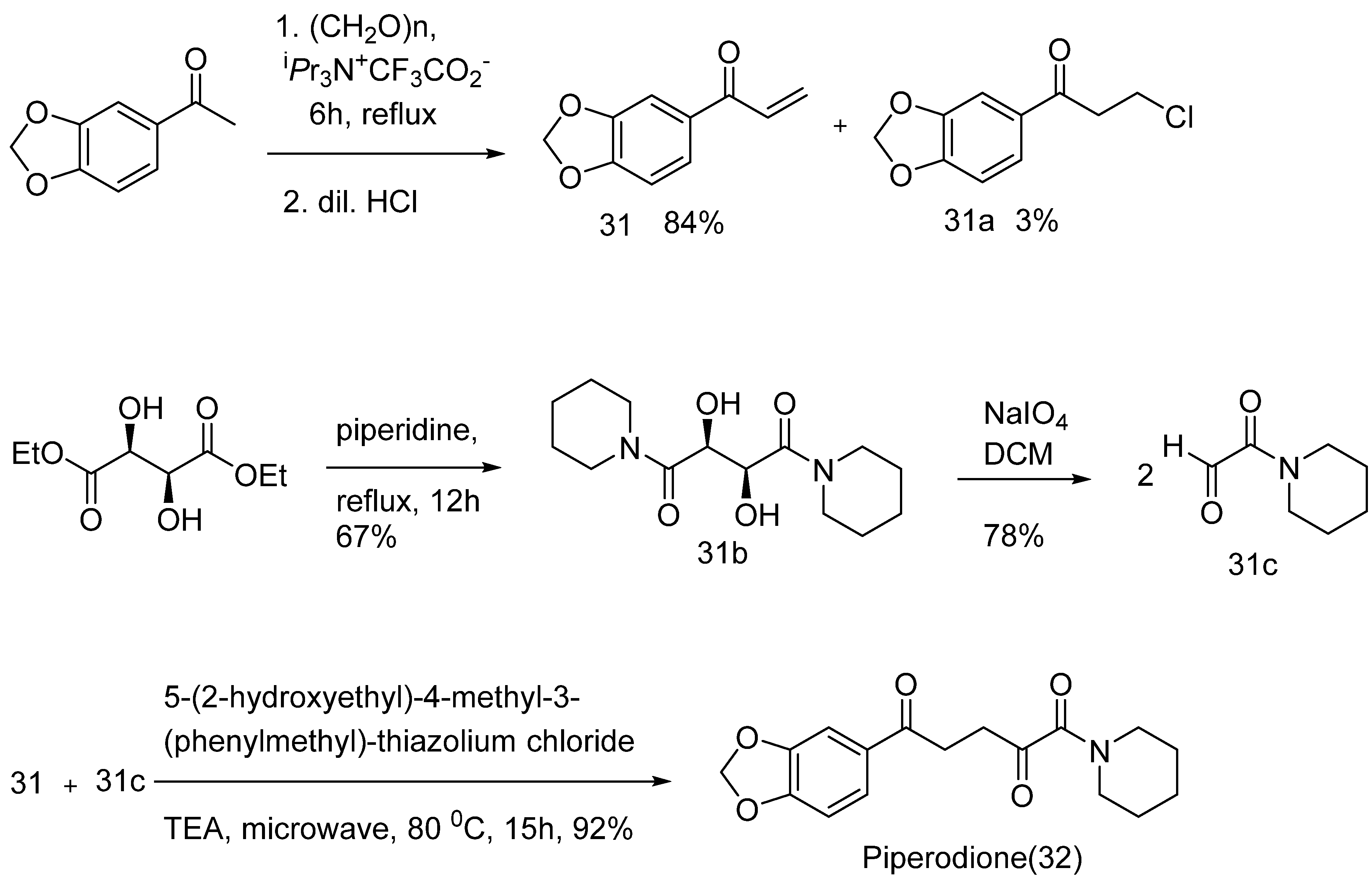

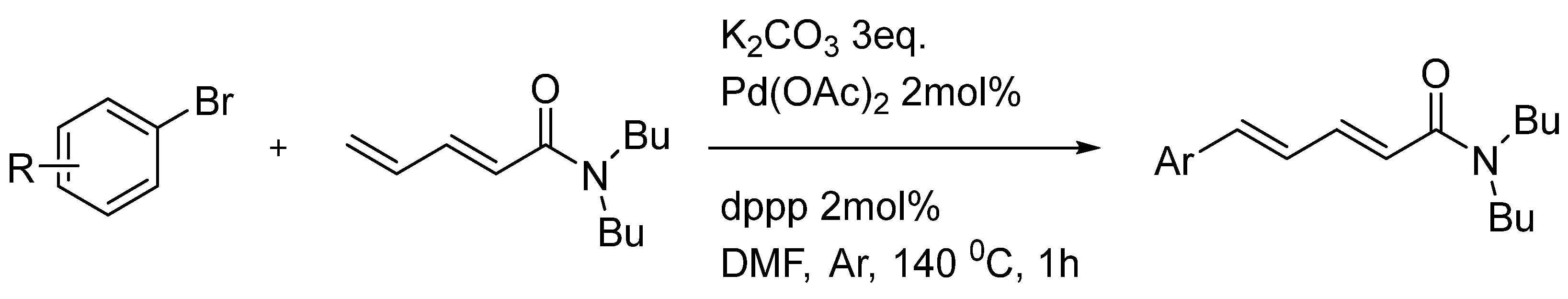

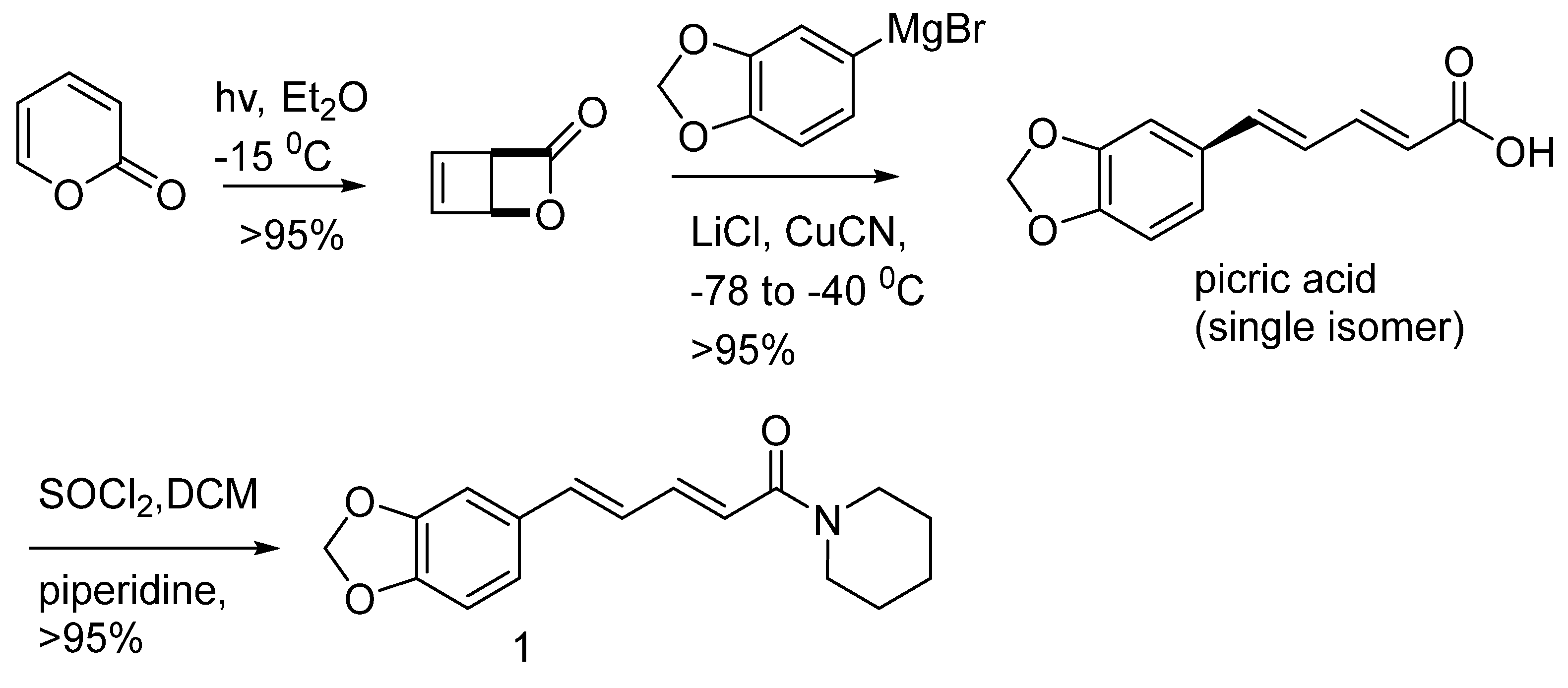

6. Synthetic and Semi-Synthetic Approaches for Compounds from Piper nigrum

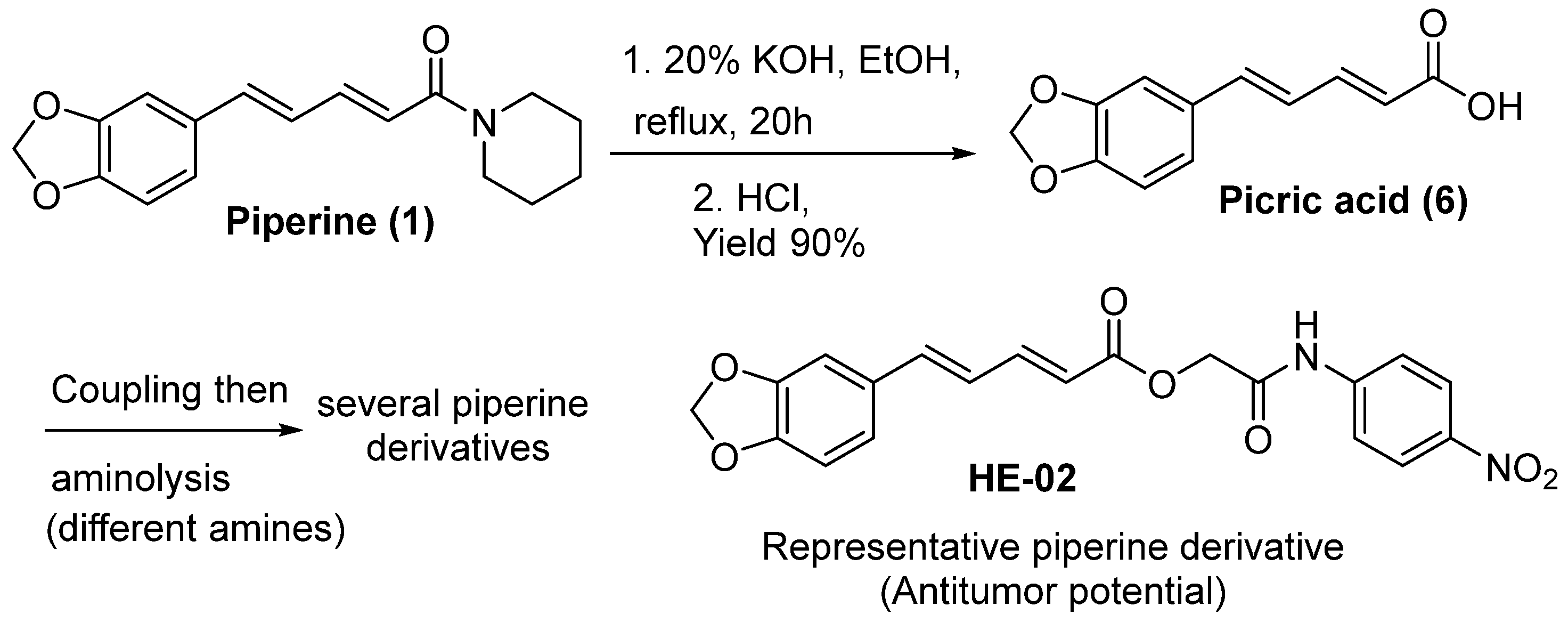

6.1. Isolation of Piperine from Natural Sources and Amide Hydrolysis

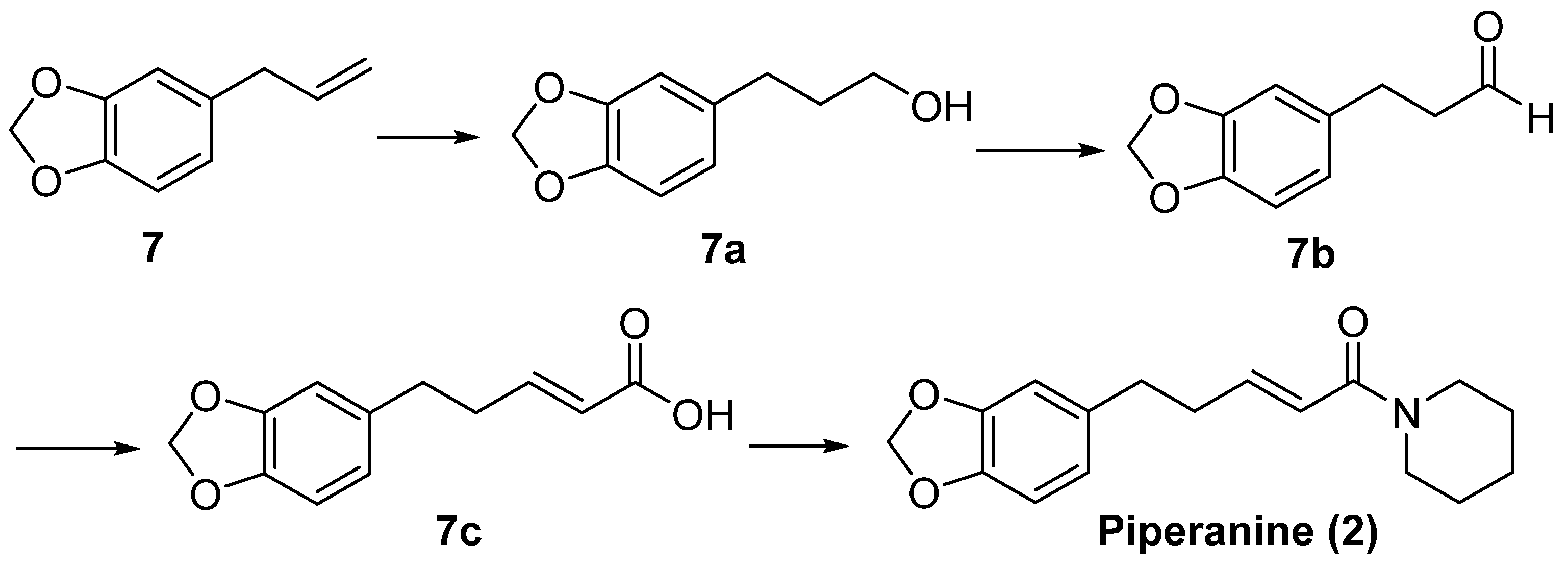

6.2. Isolation and Structure Elucidation of Piperanine

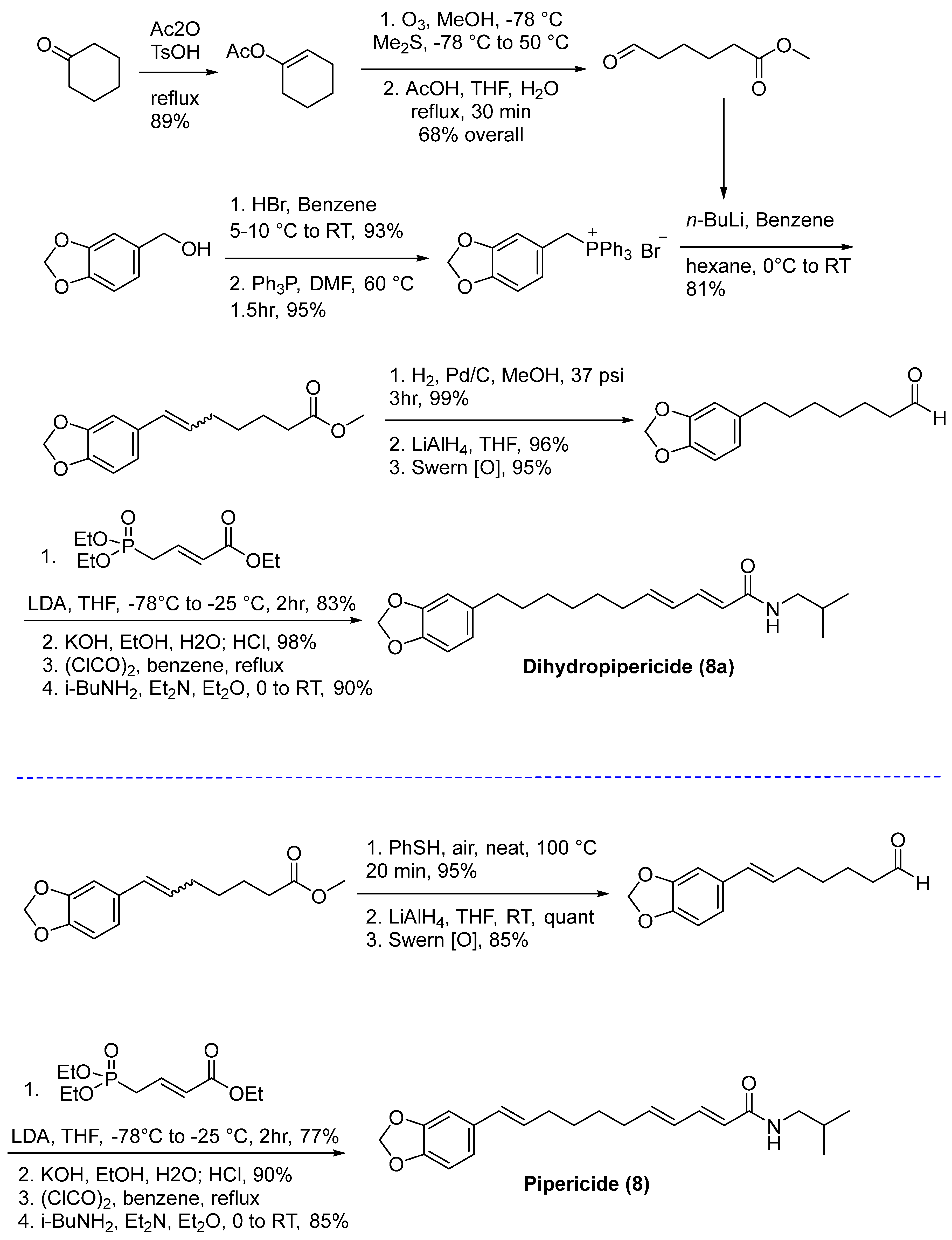

6.3. Isolation and Synthesis of Pipericide and Dihydropipericide from Piper nigrum

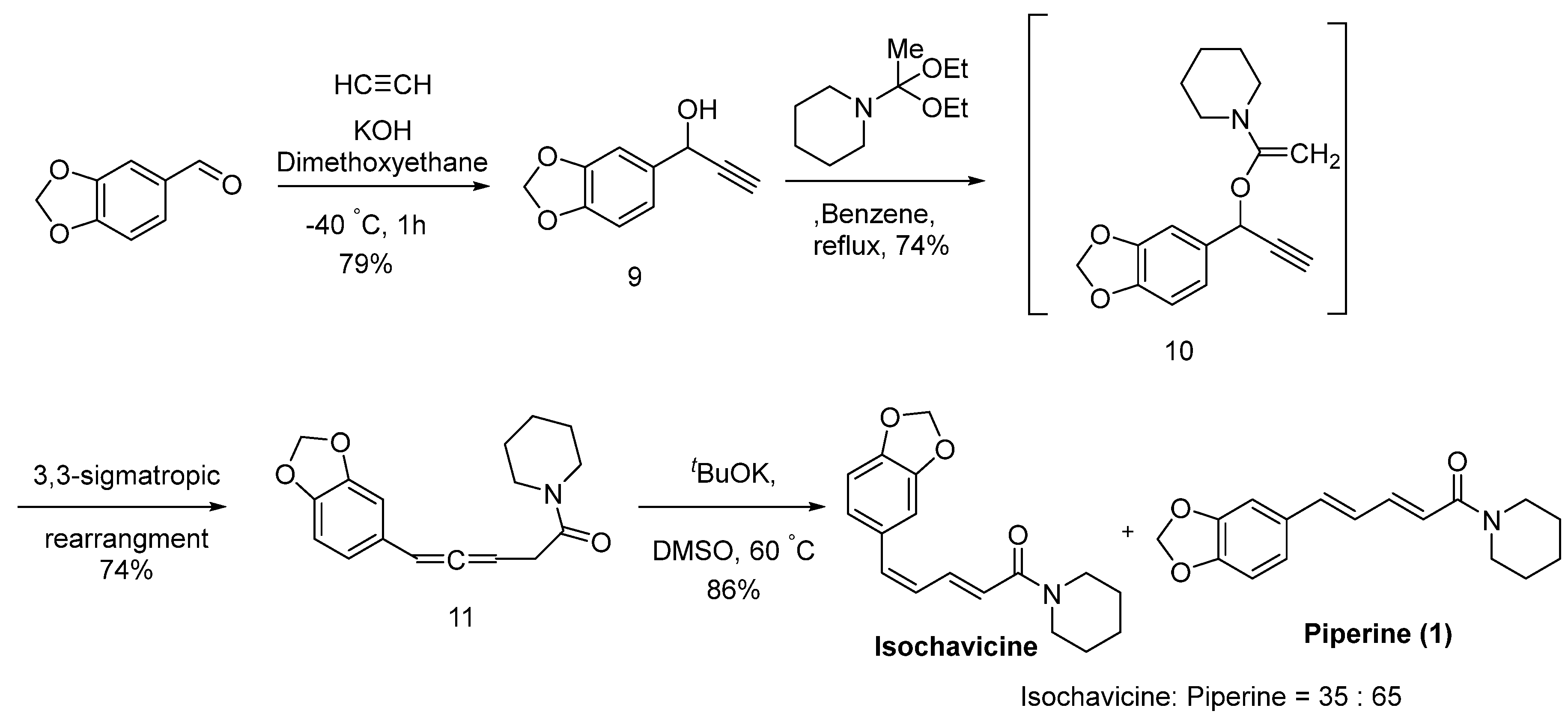

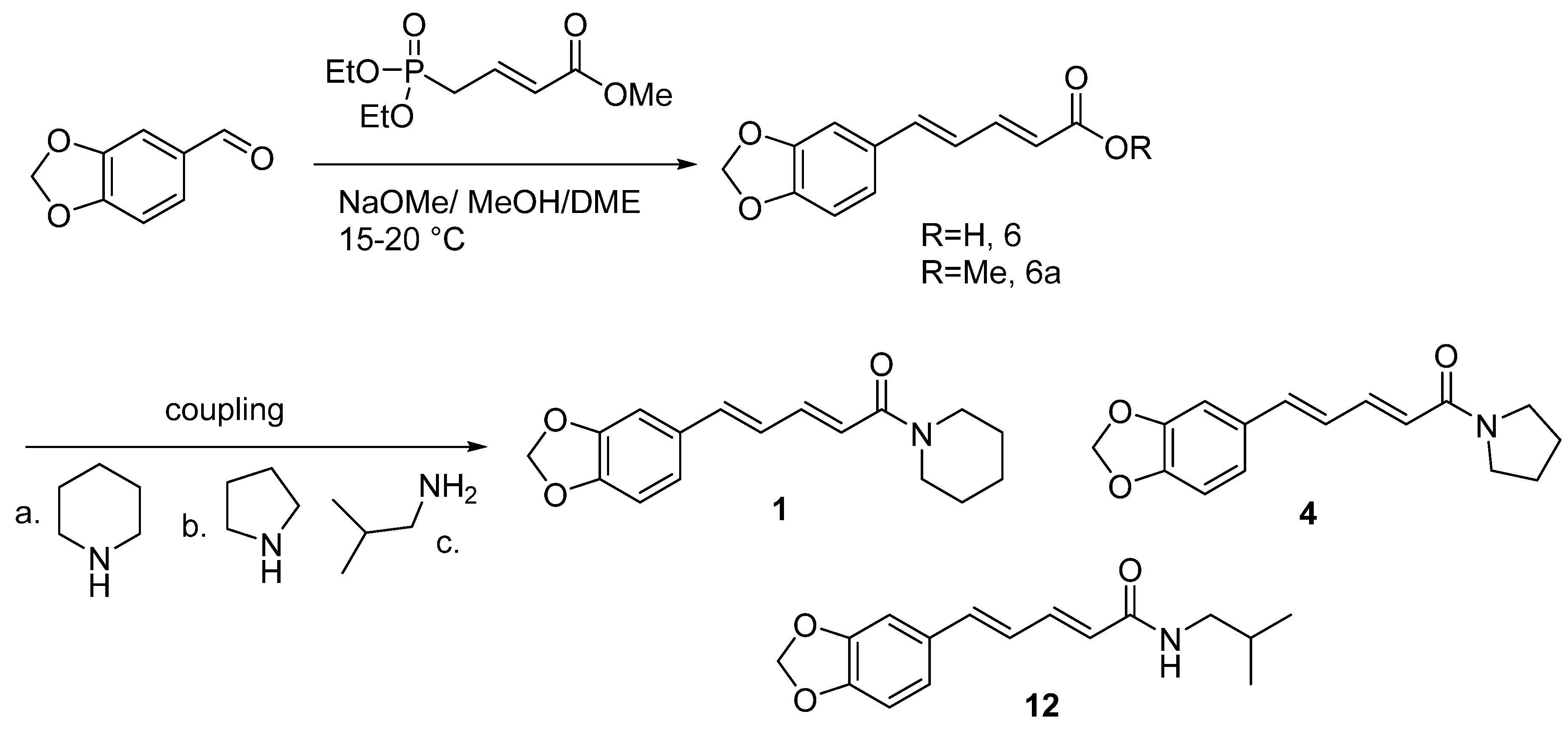

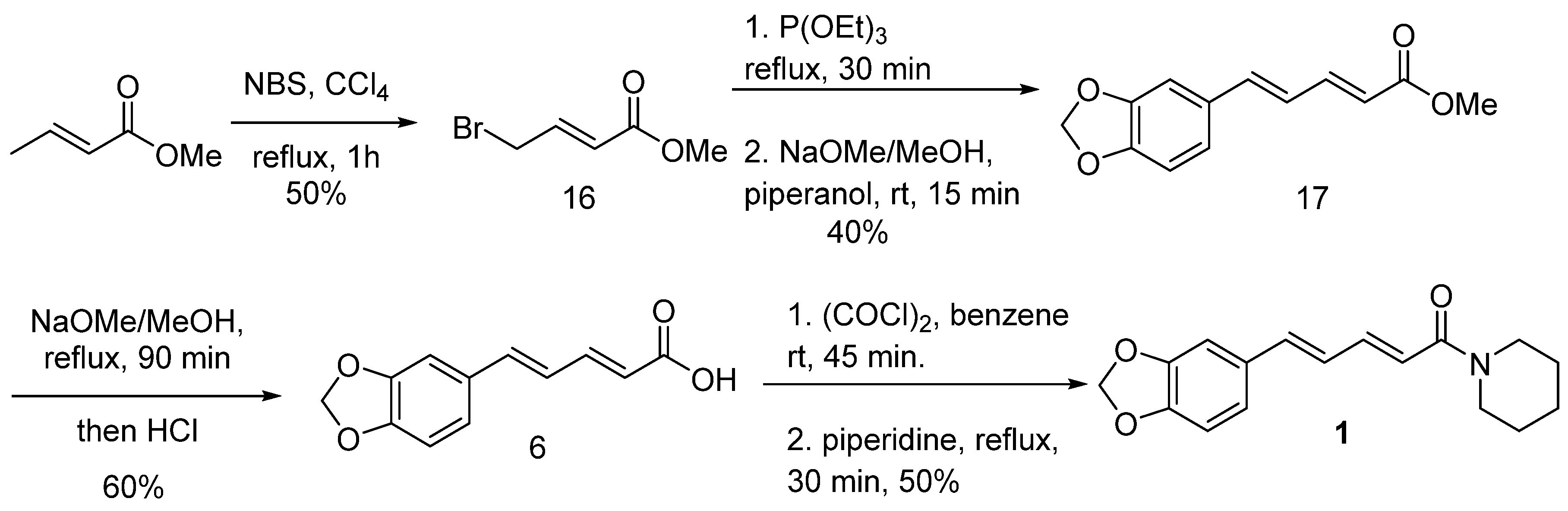

6.4. Synthesis of Piperine from piperonaldehyde

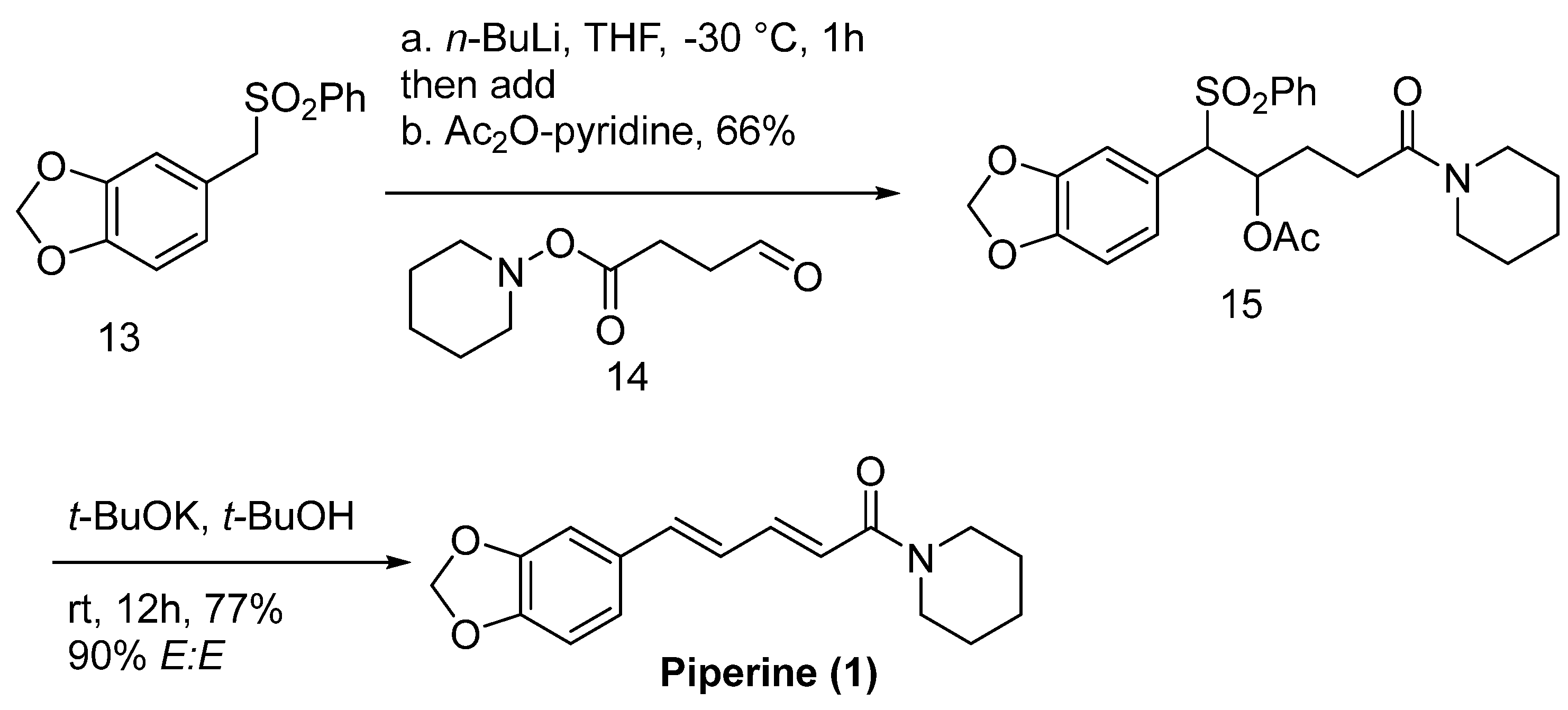

6.5. Stereoselective Synthesis of Piperine and Related Pepper-Derived alkaloids

6.6. Stereoselective Synthesis of Piperine via a Double Elimination Reaction

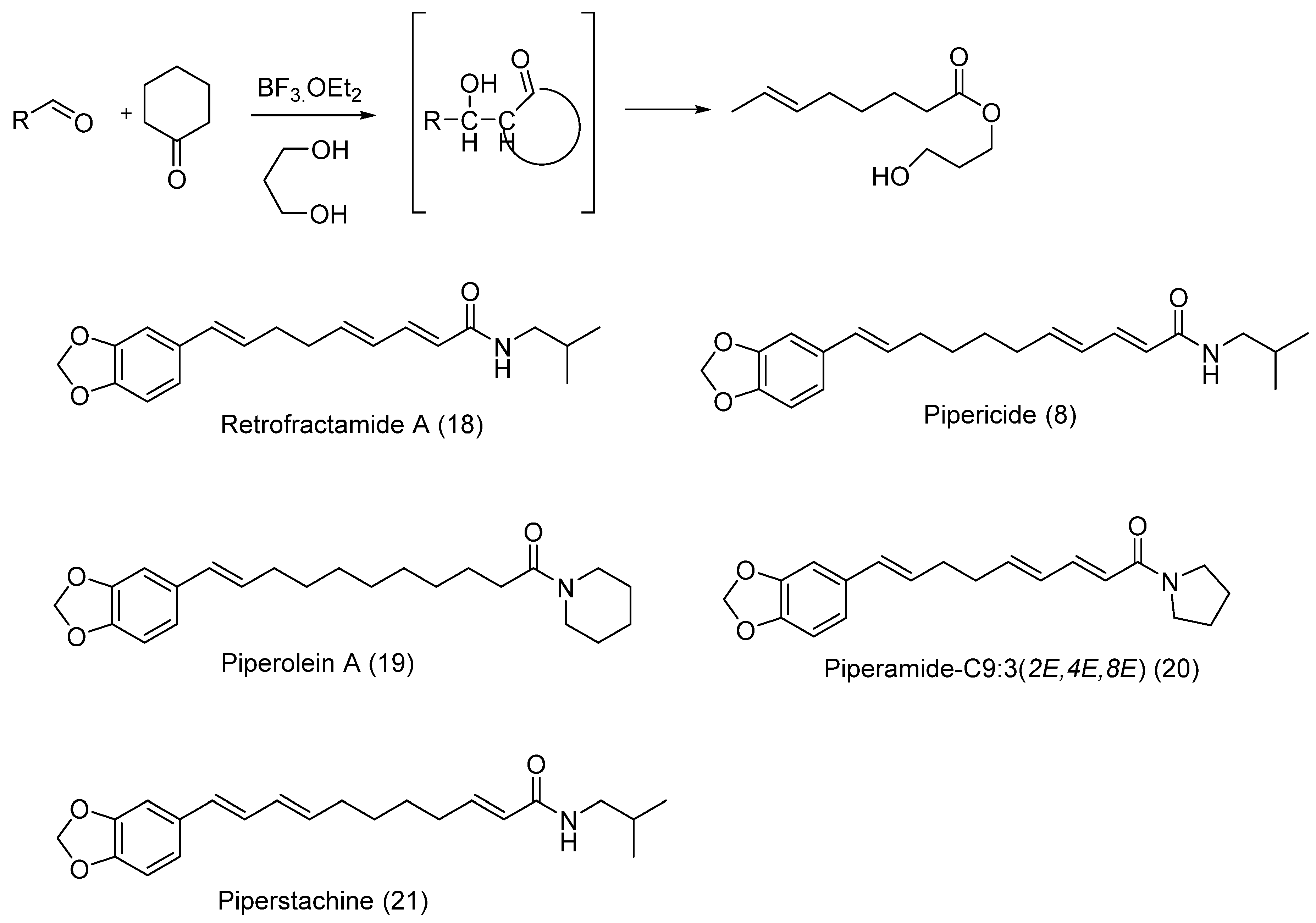

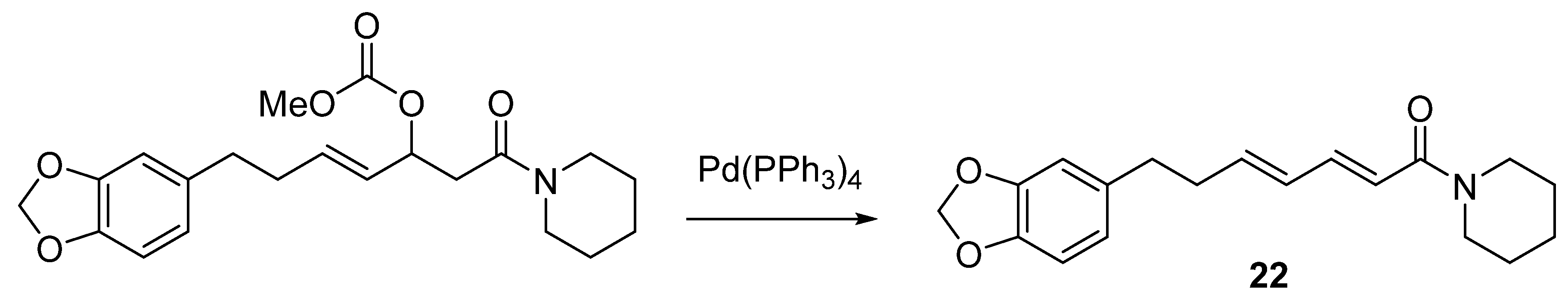

6.7. Other Piperine Synthesis Methods

7. Bioactivity of Black Pepper and Isolated Phytochemicals

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. Journal of natural products 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, K. Black pepper and its pungent principle-piperine: a review of diverse physiological effects. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2007, 47, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammouti, B.; et al. Black Pepper, the “King of Spices”: Chemical composition to applications. Arab. J. Chem. Environ. Res 2019, 6, 12–56. [Google Scholar]

- Milenković, A.N.; Stanojević, L.P. Black pepper: Chemical composition and biological activities. Advanced technologies 2021, 10, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghwal, M.; Goswami, T. Piper nigrum and piperine: an update. Phytotherapy Research 2013, 27, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashokkumar, K.; et al. Phytochemistry and therapeutic potential of black pepper [Piper nigrum (L.)] essential oil and piperine: A review. Clinical Phytoscience 2021, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørsted, H.C. Über das Piperin, ein neues Pflanzenalkaloid. J. Chem. Phys 1820, 29, 80–82. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, D.R.; Shrestha, A.C.; Adhikari, N. A review on diversified use of the king of spices: Piper nigrum (black pepper). Int J Pharm Sci Res 2018, 9, 4089–4101. [Google Scholar]

- De Cleyn, R.; Verzele, M. Constituents of peppers: I. Qualitative analysis of piperine isomers. Chromatographia 1972, 5, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grynpas, M.; Lindley, P.F. The crystal and molecular structure of 1-piperoylpiperidine. Structural Science 1975, 31, 2663–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.S.; et al. Black pepper and health claims: a comprehensive treatise. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2013, 53, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgani, L.; et al. Piperine—the bioactive compound of black pepper: from isolation to medicinal formulations. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety 2017, 16, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, L.A.; Richards, J.; Dodson, C.D. Isolation; synthesis, and evolutionary ecology of Piper amides, in Piper: A model genus for studies of phytochemistry, ecology, and evolution. 2004, Springer. p. 117-139.

- Subehan, et al. Alkamides from Piper nigrum L. and their inhibitory activity against human liver microsomal cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6). Natural Product Communications 2006, 1, 1934578X0600100101.

- Joshi, D.R.; Shrestha, A.C.; Adhikari, N. A review on diversified use of the King of Spices: Piper nigrum (Black Pepper). Int J Pharm Sci & Res 2018, 9, 4089-01. [Google Scholar]

- Askari, G.; et al. Evaluation of curcumin-piperine supplementation in COVID-19 patients admitted to the intensive care: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial, in Application of Omic Techniques to Identify New Biomarkers and Drug Targets for COVID-19. 2023, Springer. p. 413-426.

- Heidari, H.; et al. Curcumin--piperine co--supplementation and human health: A comprehensive review of preclinical and clinical studies. Phytotherapy Research 2023, 37, 1462–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; et al. Cardiovascular protective effect of black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) and its major bioactive constituent piperine. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 117, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, A.; et al. The synergistic combination of cisplatin and piperine induces apoptosis in MCF-7 cell line. Iranian Journal of Public Health 2021, 50, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carp, O.E. Electrochemical behaviour of piperine. Comparison with control antioxidants. Food Chemistry 2021, 339, 128110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrnezhad, R.; et al. Piperine improves experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in lewis rats through its neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects. Molecular neurobiology 2021, 58, 5473–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, P.; et al. Harnessing the mitochondrial integrity for neuroprotection: Therapeutic role of piperine against experimental ischemic stroke. Neurochemistry international 2021, 149, 105138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; et al. Piperine promotes autophagy flux by P2RX4 activation in SNCA/α-synuclein-induced Parkinson disease model. Autophagy 2022, 18, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, N.; Kumar, A. Piperine analogs arrest c-myc gene leading to downregulation of transcription for targeting cancer. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 22909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, V.; Elangovan, K.; Devaraj, S.N. Targeting hepatocellular carcinoma with piperine by radical-mediated mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis: An in vitro and in vivo study. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2017, 105, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; et al. Natural piperine improves lipid metabolic profile of high-fat diet-fed mice by upregulating SR-B1 and ABCG8 transporters. Journal of Natural Products 2021, 84, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; et al. Piperine-loaded PLGA nanoparticles as cancer drug carriers. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2021, 4, 14197–14207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumeeruddy, M.Z.; Mahomoodally, M.F. Combating breast cancer using combination therapy with 3 phytochemicals: Piperine, sulforaphane, and thymoquinone. Cancer 2019, 125, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athukuri, B.L.; Neerati, P. Enhanced oral bioavailability of domperidone with piperine in male wistar rats: involvement of CYP3A1 and P-gp inhibition. Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences 2017, 20, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elimam, D.M.; et al. Natural inspired piperine-based ureas and amides as novel antitumor agents towards breast cancer. Journal of enzyme inhibition and medicinal chemistry 2022, 37, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of black pepper and its bioactive compounds in age-related neurological disorders. Aging and disease 2023, 14, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Choudhary, A. Piperine and derivatives: trends in structure-activity relationships. Current topics in medicinal chemistry 2015, 15, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Rengaian, G. A review on the ecology, evolution and conservation of Piper (Piperaceae) in India: future directions and opportunities. The Botanical Review 2022, 88, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, K.; et al. Phytochemistry and therapeutic potential of black pepper [Piper nigrum (L.)] essential oil and piperine: a review. Clinical Phytoscience 2021, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandy, K.; Pillay, V. Functional differentiation in the shoot system of pepper vine [Piper nigrum Linn, India]. Indian Spices 1979, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Tainter, D.R.; Grenis, A.T. Spices and seasonings: A food technology handbook. 2001: John Wiley & Sons.

- Nwofia, G.E.; Kelechukwu, C.; Nwofia, B.K. Nutritional composition of some Piper nigrum (L.) accessions from Nigeria. 2013.

- Ashokkumar, K.; et al. Profiling bioactive flavonoids and carotenoids in select south Indian spices and nuts. Natural product research 2020, 34, 1306–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sruthi, D.; et al. Correlation between chemical profiles of black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) var. Panniyur-1 collected from different locations. 2013.

- Feitosa, B.d.S. Chemical composition of Piper nigrum L. cultivar guajarina essential oils and their biological activity. Molecules 2024, 29, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; et al. A comprehensive review on the main alkamides in Piper nigrum and anti-inflammatory properties of piperine. Phytochemistry Reviews 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, P.S.; et al. Varietal evaluation of black pepper (Piper nigrum LJ for yield, quality and anthracnose disease resistance in Idukki District, Kerala. Journal of Spices and Aromatic Crops 2002, 11, 122–124. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; et al. Composition comparison of essential oils extracted by hydrodistillation and microwave-assisted hydrodistillation from Amomum tsao-ko in China. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2010, 13, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utpala Parthasarathy, U.P.; et al. Spatial influence on the important volatile oils of Piper nigrum leaves. 2008.

- Asadi, M. Chemical constituents of the essential oil isolated from seed of black pepper, Piper nigrum L.,(Piperaceae). International Journal of Plant Based Pharmaceuticals 2022, 2, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; et al. Comparative studies on physicochemical properties and GC-MS analysis of essential oil of the two varieties of the black pepper (Piper nigrum Linn.). International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Phytopharmacological Research 2012, 2, 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Packiyasothy, E.; Balachandran, S.; Jansz, E. Effect of storage (in small packages) on volatile oil and piperine content of ground black pepper. Journal of the National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka 1983, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orav, A.; et al. Effect of storage on the essential oil composition of Piper nigrum L. fruits of different ripening states. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2004, 52, 2582–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.G.; et al. The essential oil of Brazilian pepper, Schinus terebinthifolia Raddi in larval control of Stegomyia aegypti (Linnaeus, 1762). Parasites & vectors 2010, 3, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Sreedharan, S.; Mahadik, K. Role of piperine as an effective bioenhancer in drug absorption. Pharm Anal Acta 2018, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jaisin, Y.; et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of piperine on UV-B-irradiated human HaCaT keratinocyte cells. Life Sciences 2020, 263, 118607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, A.O.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of piperine, an alkaloid from the Piper genus, on the Parkinson’s disease model in rats. 2015.

- Hashimoto, K.; et al. Photochemical isomerization of piperine, a pungent constituent in pepper. Food Science and Technology International, Tokyo 1996, 2, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanatombi, K.; Rajkumari, S. Effect of processing on quality of pepper: A review. Food Reviews International 2020, 36, 626–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosoky, N.S.; et al. Volatiles of black pepper fruits (Piper nigrum L.). Molecules 2019, 24, 4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francomano, F.; et al. β-Caryophyllene: a sesquiterpene with countless biological properties. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shingate, P.; Dongre, P.; Kannur, D. New method development for extraction and isolation of piperine from black pepper. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2013, 4, 3165. [Google Scholar]

- Milenković, A.; et al. The Effect of Extraction Technique on the Yield, Extraction Kinetics and Antioxidant Activity of Black Pepper (Piper nigrum L.) Ethanolic Extracts. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgani, L.; et al. Sequential microwave-ultrasound-assisted extraction for isolation of piperine from black pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Food and Bioprocess Technology 2017, 10, 2199–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.R.; et al. Supercritical fluid extraction of black pepper (Piper nigrun L.) essential oil. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 1999, 14, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Green and solvent-free simultaneous ultrasonic-microwave assisted extraction of essential oil from white and black peppers. Industrial Crops and Products 2018, 114, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwamba, C.; et al. Innovative green approach for extraction of piperine from black pepper based on response surface methodology. Sustainable Chemistry 2023, 4, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.; et al. The study on extraction process and analysis of components in essential oils of black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) seeds harvested in Gia Lai Province, Vietnam. Processes 2019, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, G.F.; Palma, M.; Barroso, C.G. Pressurized liquid extraction of capsaicinoids from peppers. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2006, 54, 3231–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, J.; et al. Effect of enzyme assisted extraction on quality and yield of volatile oil from black pepper and cardamom. Food Science and Biotechnology 2012, 21, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; et al. Chemical analysis and classification of black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) based on their country of origin using mass spectrometric methods and chemometrics. Food Research International 2021, 140, 109877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sing, D.; et al. Rapid estimation of piperine in black pepper: Exploration of Raman spectroscopy. Phytochemical Analysis 2022, 33, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Pérez, A.; Romero-González, R.; Frenich, A.G. A metabolomics approach based on 1H NMR fingerprinting and chemometrics for quality control and geographical discrimination of black pepper. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2022, 105, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacometti, C.; et al. Authenticity assessment of ground black pepper by combining headspace gas-chromatography ion mobility spectrometry and machine learning. Food Research International 2024, 179, 11402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, G.J.; Omran, A.M.; Hussein, H.M. Antibacterial and phytochemical analysis of Piper nigrum using gas chromatography-mass Spectrum and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemical Research 2016, 8, 977–996. [Google Scholar]

- De Cleyn, R.; Verzele, M. Constituents of peppers. Chromatographia 1972, 5, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; et al. Th1-biased immunomodulation and in vivo antitumor effect of a novel piperine analogue. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, R.A.; Spessard, G.O. A short, stereoselective synthesis of piperine and related pepper-derived alkaloids. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1981, 29, 942–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rtigheimer, L.K. Piperin. Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft 1882, 15, 1390–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladenburg, A.a.S.M. Synthese der Piperinsaure und des Piperins. Berichte der Deutschen chemischen GesellschaJt 1894, 27, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring; E.S.; Stark; J.J. Piperettine from Piper nigrum: Its isolation, identification, and synthesis. Journal of the Chemical Society 1950, 1177-1180.

- Traxler, J.T. Piperanine, a pungent component of black pepper. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1971, 19, 1135–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakado, M.; Yoshioka, H. The Piperaceae amides. II: Synthesis of pipericide, a new insecticidal amide from Piper nigrum L. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry 1979, 43, 2413–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shityakov, S.; et al. Phytochemical and pharmacological attributes of piperine: A bioactive ingredient of black pepper. European journal of medicinal chemistry 2019, 176, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, H.J.; Mishra, S.K.; Sharma, K. Phytochemical studies of Piper nigrum L: a comprehensive review. Pharmacological Benefits of Natural Agents 2023, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rotherham, L.W.; Semple, J.E. A practical and efficient synthetic route to dihydropipercide and pipercide. Journal of Organic Chemistry 1998, 63, 6667–6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, N.; Inatani, R.; Fuwa, H. Structures and syntheses of two phenolic amides from Piper nigrum L. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry 1980, 44, 2831–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inatani, R.; Nakatani, N.; Fuwa, H. Structure and synthesis of new phenolic amides from Piper nigrum L. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry 1981, 45, 667–673. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi, S.A.T. A new synthesis of piperine and isochavicine. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 20, 1043–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normant, H.; Feugeas, C. CHIMIE ORGANIQUE-SYNTHESE TOTALE DE LA PIPERINE. COMPTES RENDUS HEBDOMADAIRES DES SEANCES DE L ACADEMIE DES SCIENCES 1964, 258, 2846. [Google Scholar]

- Mandai, T.; et al. Highly stereoselective synthesis of (2E, 4E)-dienamides and (2E, 4E)-dienoates via a double elimination reaction. Tetrahedron letters 1986, 27, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloop, J.C. Microscale synthesis of the natural products carpanone and piperine. Journal of Chemical Education 1995, 72, A25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunz, G.M.; Finlay, H. Concise, efficient new synthesis of pipercide, an insecticidal unsaturated amide from Piper nigrum, and related compounds. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 11113–11122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunz, G.M.; Finlay, H.J. Expedient synthesis of unsaturated amide alkaloids from Piper spp: exploring the scope of recent methodology. Canadian journal of chemistry 1996, 74, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, I.; Braun, M. Synthesis of naturally occurring dienamides by palladium-catalyzed carbonyl alkenylation. Journalfiir Praktische Chemie 1999, 341, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, S.M.V.R.; Srinivasa Reddy, K.; Ramarao, C. Addition of carbon nucleophiles to aldehyde tosylhydrazones of aromatic and heteroaromatic-compounds: total synthesis of piperine and its analogs. Tetrahedron Letters 2000, 41, 2667–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, V.F.d.; et al. Synthesis and insecticidal activity of new amide derivatives of piperine. Pest Management Science 2000, 56, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.-J.; et al. Synthesis of dienamide natural products using a hypervalent iodine (III) reagent. The Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal 2001, 53, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sven Sommerwerk, S.K.; Lucie, H.; René, C. First total synthesis of piperodione and analogs. Tetrahedron Letters. 2014, 55, 6243–6244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, L.; et al. Developing piperine towards TRPV1 and GABA A receptor ligands–synthesis of piperine analogs via Heck-coupling of conjugated dienes. Organic & biomolecular chemistry 2015, 13, 990–994. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A.J.-H.N.; Maulide, N.; Short, A. Efficient, and Stereoselective Synthesis of Piperine and its Analogues. Synlett 2019, 30, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takooree, H.; et al. A systematic review on black pepper (Piper nigrum L.): from folk uses to pharmacological applications. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2019, 59 (sup1), S210–S243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dludla, P.V.; et al. Bioactive properties, bioavailability profiles, and clinical evidence of the potential benefits of black pepper (Piper nigrum) and red pepper (Capsicum annum) against diverse metabolic complications. Molecules 2023, 28, 6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, E.M.; Abdalla, W.E. Black pepper fruit (Piper nigrum L.) as antibacterial agent: A mini-review. J Bacteriol Mycol Open Access 2018, 6, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halligudi, N.; Bhupathyraaj, M.; Hakak, M.H.S. Therapeutic potential of bioactive compounds of Piper nigrum L.(Black Pepper): a review. Asian J Appl Chem Res 2022, 12, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khew, C.Y.; Koh, C.M.M.; Hwang, S.S. A review on the main compound of Black pepper (Piper nigrum), Piperine, in diabetes management: How the everyday spice could improve insulin sensitivity? Focus on Pepper 2022, 12, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, B.; Malviya, R.; Sharma, A. Therapeutic benefits of Piper nigrum: a review. Current Bioactive Compounds 2022, 18, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, A.N.; et al. Chemical composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of essential oils isolated from black (Piper nigrum L.) and cubeb pepper (Piper cubeba L.) fruits from the Serbian market. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2023, 35, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umapathy, V.R.; et al. Anticancer potential of the principal constituent of Piper nigrum, Piperine: a comprehensive review. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Huertas, L.F.; et al. Characterization and Isolation of Piperamides from Piper nigrum Cultivated in Costa Rica. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition | Concentration |

| Proximate | |

| Energy (Kcal) | 400.0 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 66.5 |

| Fat (g) | 10.2 |

| Protein (g) | 10.0 |

| Total Ash (%) | 3.43-5.09 |

| Water (g) | 8.0 |

| Crude Fibre (%) | 10.79-18.60 |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium (mg) | 400.0 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 235.8-249.8 |

| Potassium (mg) | 1200.0 |

| Sodium (mg) | 10.0 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 160.0 |

| Iron (mg) | 17.0 |

| Zinc (mg) | 1.45-1.72 |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 27.46-32.53 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 0.74-0.91 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 0.48-0.61 |

| Vitamin B3 (mg) | 0.63-0.78 |

| Metabolites | |

| Tannin (mg) | 2.11-2.80 |

| Flavonoids | |

| Catechin (µg) | 410.0 |

| Myricetin (µg) | 56.0 |

| Quercetin (µg) | 13.0 |

| Carotenoids | |

| Lutein (µg) | 260.0 |

| β-Carotene (µg) | 150.0 |

| Constituent | Concentration Range (%) |

| β-Caryophyllene | 2.09–26.95 |

| Limonene | 15.13–29.90 |

| Sabinene | 0.00–19.23 |

| α-Pinene | 3.88–20.86 |

| β-Pinene | 12.1–19.0 |

| δ-3-Carene | 9.23–55.43 |

| β-Bisabolene | 1.32–7.96 |

| α-Humulene | 1.11–2.44 |

| α-Copaene | 0.20–5.51 |

| α-Cadinol | 0.18–4.89 |

| α-Thujene | 0.60–2.94 |

| Nerolidol | 0.14–66.32 |

| β-Phellandrene | 3.16–4.80 |

| Myrcene (β-Myrcene) | 1.99–2.9 |

| 1-Napthalenol | 3.00 |

| Sylvestrene | 10.67 |

| Germacrene D | 2.17 |

| Isoterpinolene | 1.40 |

| Linalool | 2.10 |

| β-Terpenine | 19.50 |

| α-Phellandrene | 2.20 |

| Category | Extraction Method | Technique/Process | Target Compounds | Advantages | Limitations |

| Traditional Extraction Methods (TEM) | Solvent Extraction | Maceration or Soxhlet with ethanol, methanol, acetone, chloroform, hexane | Piperine, essential oils, alkaloids | Simple, widely used, low cost | Low selectivity, solvent residues, degradation of thermolabile compounds |

| Steam Distillation | Steam passed through crushed pepper to vaporize volatiles | Essential oils | Effective for volatile oils, easy setup | High temperature may degrade sensitive compounds | |

| Cold Pressing / Infusion | Mechanical pressing or soaking in oil | Flavor compounds, minor volatiles | Traditional, non-toxic, culinary use | Low efficiency, not suitable for alkaloid extraction | |

| Modern & Green Extraction Techniques (MGET) | Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Supercritical CO2 (often with ethanol) | Piperine, essential oils | High purity, non-toxic, tunable selectivity | Expensive equipment, technical complexity |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Ultrasonic waves enhance solvent penetration | Piperine, phenolics | Fast, solvent-saving, good for heat-sensitive compounds | Scale-up limitations, equipment cost | |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Microwave energy heats plant-solvent matrix | Piperine, flavonoids, polyphenols | High efficiency, less solvent, reduced time | Risk of thermal degradation if not optimized | |

| Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) | High pressure and temperature solvent-based extraction | Polar and non-polar compounds | Rapid, efficient, minimal degradation | Requires specialized apparatus | |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) | Enzymatic treatment (e.g., cellulase, pectinase) | Phenolics, alkaloids | Mild, eco-friendly, suitable for food-grade products | Enzyme cost, need for process optimization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).