1. Introduction

Modern cosmology faces persistent tensions between early- and late-time measurements of the cosmic expansion rate [

1,

2]. While the

CDM model successfully describes most large-scale observations, it relies on the assumption of homogeneity and a dark energy component with constant equation of state. The resulting framework reproduces the CMB anisotropies and baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO), yet shows growing discrepancies in the Hubble constant

and the detailed shape of

inferred from supernovae and cosmic chronometers.

An alternative viewpoint emerges if one relaxes the assumption of large-scale smoothness. Inhomogeneities can modify the averaged cosmic dynamics through non-linear backreaction terms [

3], while gravitational clustering itself may produce fractal-like matter distributions at different epochs [

4,

5]. Within this broader context, the

Ultimate Black Hole (UBH) cosmology proposes that the Universe originated from the fragmentation of an ultimate black hole, whose decay generated a self-similar, entropy-driven hierarchy of black holes across scales. This fractal inheritance governs the expansion history through a redshift-dependent effective spatial dimension

, linking microstructure, entropy growth, and large-scale kinematics.

The present paper develops this scenario into a quantitative cosmological model and performs its first observational test. By incorporating both fractal entropy effects and Buchert-type backreaction, the UBH framework generalizes the Friedmann equation while retaining a minimal, physically interpretable parameter set. Fitting this model to the Pantheon Type Ia supernova sample yields an excellent agreement and reproduces the locally measured Hubble constant

, while maintaining consistency with the early-Universe calibration from

Planck data [

6]. Hence, the long-standing

Hubble tension can be resolved within a single, self-consistent formalism.

The structure of the paper is as follows.

Section 2 outlines the theoretical foundations, introducing the fractal entropy concept, the modified Hubble function with backreaction, the early-time Fractal Early Energy term (FEE), and curvature-window terms.

Section 2.8 presents the dataset and fitting method.

Section 3 summarizes the results, the statistical outcomes, and the robustness tests.

Section 4 discusses the physical interpretation and implications for cosmic structure, entropy evolution, and the Hubble tension. Conclusions are drawn in

Section 5.

2. Theoretical Framework and Methods

2.1. Fractal Horizon Concept, Entropy Scaling, and Critical UBH Mass

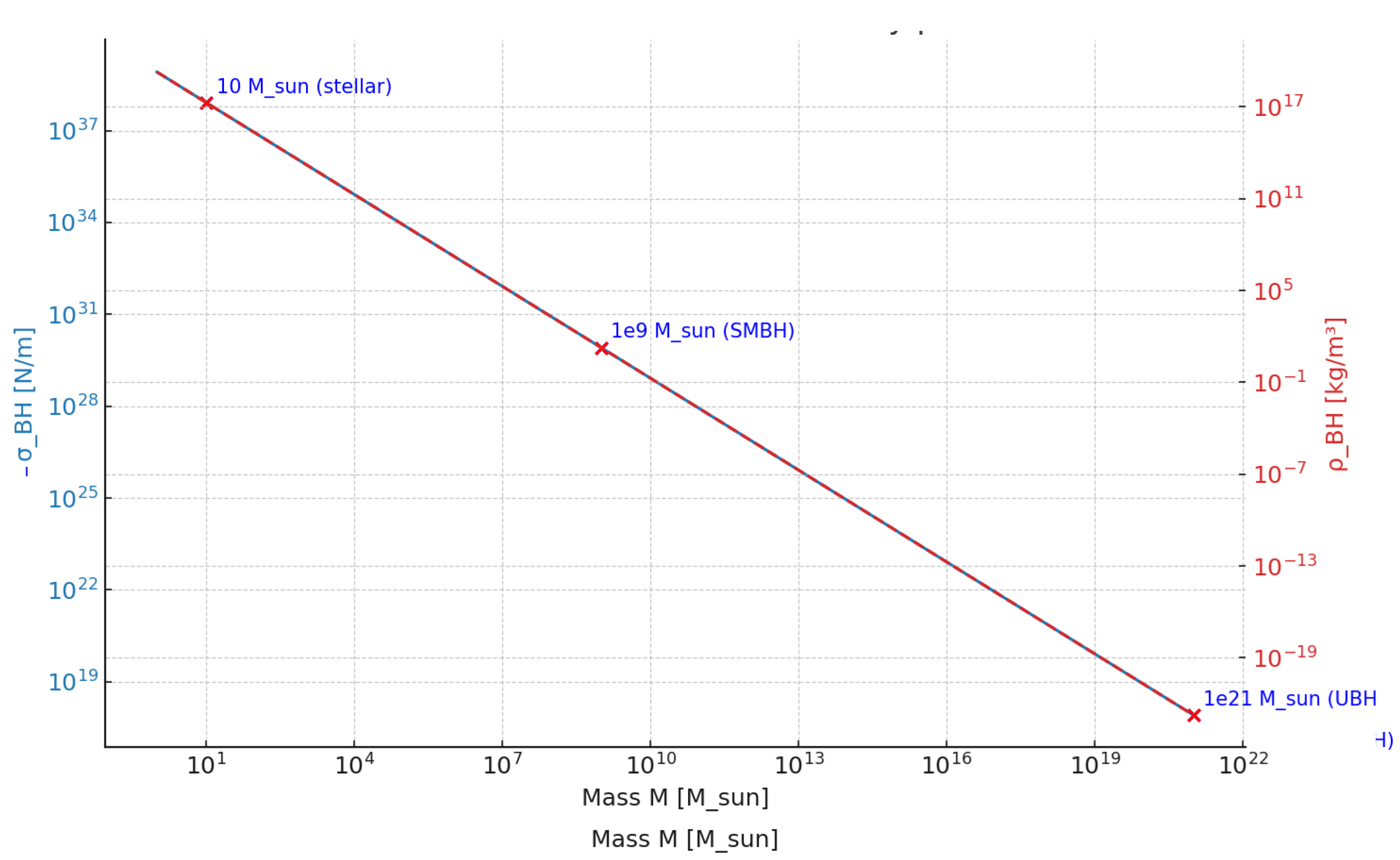

As a starting point for the following considerations, we consider the state of the UBH with already sufficiently large mass. Since the Schwarzschild radius is proportional to this mass (

), the mass density

-see

Figure 1. At

(

= solar mass), the mass density is incredibly low, and quantum gravity fluctuations can then lead to structure formation, especially near the horizon. Again, due to the low density, filament-like structures should form, but these develop into fractal structures, as is known from growing processes in nature [

7]. It seems reasonable to assume that the fractal dimension of these objects is between 1 and 2. These structures can in turn be metastable over time, as the dissipation processes are not sufficient to smooth the structures due to the low density. Moreover, these quasi-one-dimensional structures together with the strongly reduced effective surface tension of the horizon (cf.

Figure 1, [

8]) stimulate the fraying and fracturing of the horizon surface .

That means, the horizon of a sufficiently massive black hole cannot remain a smooth, two-dimensional sphere as in the standard Bekenstein–Hawking picture [

9,

10]. And it is natural that the limp and susceptible horizon will take on a fractal structure with a fractal dimension greater than 2, because of the quasi-spherical surface. Due to the causal connection between the volumes and surface structures, it makes sense to assume that the Hurst parameters of the internal structures and the horizon are the same, i.e.

. It is essential to note that fractal scaling of the horiyon has a lower and upper limit. The lower cutoff length

is certainly larger than the Planck length

, since smoothing dissipative processes becomes more effective for smaller distances. On the other hand, fractal growth of the horizon is also limited upwards by by a characteristic upper cutoff scale

.This scale is not arbitrary; by analogy with the arguments that stabilize the nearly spherical equilibrium of astrophysical horizons (suppressing long-wavelength corrugations),

can be viewed as the smallest dynamically coherent surface/metric fluctuation that survives coarse-graining in the emergent spacetime description. As a consequence of both cutoff the effective area

of the UBH horizon scales approximately as [

7]

where

is the area of a smooth horizon of radius

and the fractal morphology of the UBH horizon is characterized by the Hurst parameter

with fractal dimension

If the Bekenstein–Hawking relation remains valid for such a fractalized surface, the entropy of the UBH becomes

where

is the standard entropy of a smooth-horizon black hole.

To consider the instability of the UBH we have to compare the UBH entropy with the entropy of a population of distributed black holes with rather different sizes distributed self-similarly within the UBH volume, forming a fractal configuration characterized by the scaling law for their entropy

where

as the upper cutoff of the fractal domain is smaller or even equal to the UBH radius

. The lower cutoff

is probably the same as that for the horizon structure but it can be even smaller, at least equal the Planck length

.

is the sum of entropies of the assumed population of black holes. According to the above mentioned arguments, the fractal character of the inner UBH structure and the horizon is inherited by the cosmic medium, the fractal Hurst parameter

used in Equ.

4 must be the the same as for the horizon, i.e.

, which ensures the continuity of fractal properties across the UBH burst. The ratio of

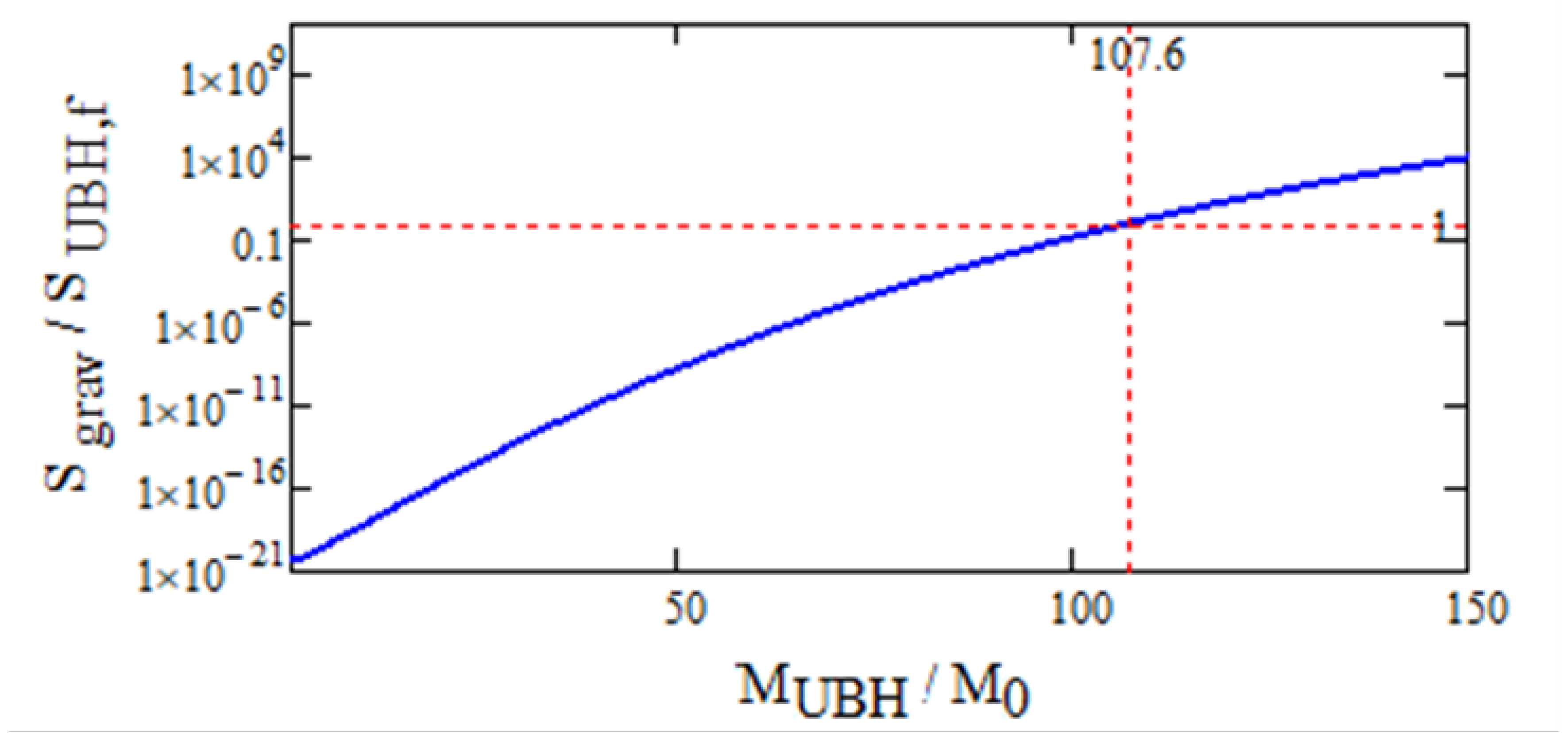

to horizon entropy is then

Analysing this relation we have to find the solution, where

as a condition for the critical UBH-mass

. Increasing the UBH-mass the quantum-gravitaional fluctuations becomes stronger with the consequence that the fractal dimension

will grow, too. Therefore, for quantitative analyses, it can be assumed that the fractal horizon dimension approximately follows the following relationship

with

a dimensionless parameter and Mo the mass at which fractal behavior begins. As

, the horizon dimension saturates at

, corresponding to a fully space-filling surface.

For plausible parameter choices the condition

is naturally satisfied, as it is shown in

Figure 2. In detail, the following parameters were used:

,

, and

. The entropy for assumed free BHs

was calulated using a log-normal mass distribution of BHs with a peak value

and a distribution width of

. For this parameters we find a critical UBH mass and the critical UBH-radius

with corresponding fractal horizon dimension

.

The preceding sections have shown that the UBH framework can describe the observed cosmic expansion and entropy evolution in a self-consistent way. However, the underlying thermodynamic balance raises a deeper question: if the Universe originates from the fragmentation of a primordial Ultimate Black Hole, could the reverse process—gravitational re-aggregation toward a new UBH—also occur as part of a long-term cosmic cycle? Such a possibility would imply that the total entropy of the Universe does not increase without bound, but instead remains globally conserved while being redistributed between its fractal and non-fractal components. This consideration motivates the following hypothesis of a reversible, adiabatic, and fractal Universe.

2.2. Hypothesis on a Reversible and Adiabatic Fractal Universe

We extend the UBH framework by introducing a conceptual hypothesis in which the Universe evolves as a reversible and adiabatic fractal system. This hypothesis naturally arises from the possibility that the Universe, after sufficient expansion, may again approach a critical state where a new UBH forms, initiating the next cosmological cycle. This description is not intended as a fully developed cosmological model but rather as a thermodynamic analogy consistent with the entropy balance inferred from the UBH concept. The total entropy is assumed to remain approximately conserved across cosmic phases, while local entropy transfer between fractal and non-fractal subsystems is allowed. Accordingly,

expresses global reversibility, whereas local exchanges maintain adiabaticity.

Just before the UBH burst, the fractal entropy consists of the UBH component and the fractal fraction of the surrounding pre-burst medium.

represents the non-fractal part, including photons, baryons, primordial black holes, and gravitational waves. The burst redistributes entropy by enhancing dissipation and altering the primordial BH mass function, effectively increasing the lower fractal cutoff

. After the burst, the cosmic entropy may be written as

where

is the scale factor and

. The factor

encodes the scale-dependent redistribution of entropy. During expansion,

decreases monotonically, while

rises such that

expressing a quasi-reversible transfer of entropy from the fractal to the cosmic sector.

Immediately after the burst, the spatial fractal dimension is expected to be

representing the inherited structure of the UBH. Its smooth evolution with scale factor can be parameterized as

with steepness parameter

, yielding

and

. In the present model the Universe thus begins with

and evolves toward

today, consistent with empirical analyses of large-scale clustering [

4,

5].

Hence, unlike the standard

CDM picture, the UBH-based cosmology does not approach perfect homogeneity (

) at late times but an isotropic yet statistically self-similar state. The apparent uniformity of CMB and BAO observations then results from averaging this fractal field over scales

. Possible long-term implications of the entropy balance—such as a thermodynamic turning point in the far future—are discussed separately in

Section 4.

2.3. Limitations of Redshift-from-Scattering Models

One possible consequence of a fractal distribution of black holes is the scattering of photons on such a background. Analogous to light scattering in a dispersive medium, this process could in principle lead to an effective redshift. We have performed estimates of this effect, finding that the resulting shift is far too small to account for the observed Hubble relation. Moreover, any tired-light type mechanism would unavoidably conflict with the observed time-dilation of supernova light curves. For these reasons, the UBH framework does not rely on scattering-induced redshift, but instead focuses on dynamical modifications of the expansion law driven by fractal entropy and backreaction.

2.4. The UBH Hubble Function with Backreaction

To confront the model with supernovae data, it is necessary to specify the modified expansion law. In the UBH scenario, the Hubble function is generalized to

where

is the present Hubble constant,

the relative density content of the radiation,

the corresponding matter part and

accounts for Buchert’s backreaction [

3]. In the framework of the UBH model this contribution replaces the dark matter term

. For simplicity, the backreaction term is parameterized as

with

as the present amplitude, which is in balance with

and

, i.e.

. The exponent

will be determined by consistency with structure formation. Thus, the UBH Hubble law introduces a small set of parameters with clear physical meaning: the present Hubble constant

, the fractal entropy parameter

, the backreaction amplitude

and exponent

, and the magnitude offset

M from the supernova calibration. This parameterization provides the link between the fractal horizon concept and the supernova luminosity-distance relation. Here we already mention, that the fit of the UBH model to the supernova Ia data yields a Hubble constant of

. The statistical analysis of the fit is performed below in

Section 2.8 and

Section 3.

2.5. Fractal Early Energy (FEE)

Having specified the UBH Hubble law with backreaction in Eq. (

12), we now isolate the early–time degree of freedom that primarily controls the sound horizon, namely the fractal early energy (FEE). FEE encapsulates the entropy–driven departure from standard radiation scaling around recombination and hence shifts the comoving sound horizon

while leaving late–time distances largely intact. In what follows we introduce

, its transition scale and dilution exponents, and adopt conservative BBN and CMB priors to keep the high–

z energy budget within observational bounds before turning to curvature effects. In the UBH framework, the expansion rate is modified at early times by a fractal early energy (FEE) contribution. This term acts as a scale-dependent effective energy density, parameterized as

where

controls the amplitude,

the transition epoch, and

regulate the slope and dilution. The role of

is to shift the expansion history in the recombination era, thus affecting the comoving sound horizon

without altering the late-time behavior in the same way as curvature.

2.6. Curvature Window and Fractal Scaling

With the FEE sector fixing the early–time shift of

, we next introduce a localized, scale–dependent curvature contribution that adjusts the line–of–sight distance to last scattering. This “curvature window” modifies

without spoiling the near–flat late–time geometry (

, hence

in our fits), providing the second lever needed to match the acoustic angle

while remaining consistent with BAO and Planck constraints. We now define

and its window parameters (amplitude, center, width) and discuss their priors. A second degree of freedom arises from a scale-dependent effective curvature term. In the standard FRW metric, curvature contributes as

. However, if the effective spatial dimension

deviates from three, as suggested by a fractal horizon structure, the scaling generalizes to

This reduces to the familiar

behavior for

, while for

the curvature contribution decays more slowly and can leave an imprint on the expansion history at intermediate redshift.

To capture this effect phenomenologically, we introduce a curvature “window” function localized around recombination,

with amplitude

, center

, and width

. This term allows the UBH model to correct the angular-diameter distance to last scattering without conflicting with late-time constraints [

2,

11].

2.7. UBH Hubble Function for all Redshift Values

With this modified Hubble law of Eq. (

17) specified, the UBH framework becomes directly testable. This provides the flexibility to match the observed Hubble constant

[

1] while keeping consistency with CMB constraints [

2]. In practice, FEE and Curvature Window become the primary lever for reconciling the Pantheon and Pantheon+ supernovae samples [

12,

13] with Planck data.

In the following subsections we investigate the key observational consequences: the acoustic angle , the angular-diameter distance , and the comoving sound horizon . Together these quantities provide the necessary link between the fractal entropy dynamics of the UBH model and precision probes such as the CMB acoustic peaks, baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO), and the luminosity-distance relation from type Ia supernovae.

2.8. Luminosity Distance in the UBH Cosmology

The key observable for type Ia supernovae is the luminosity distance,

with the comoving distance

Here

is the curvature-dependent distance function (cf. Eq. (

22) in

Section 2.9), which in our nearly flat case reduces to

. The theoretical distance modulus is then obtained as

where

M represents the absolute magnitude calibration parameter.

In practice,

M is fitted jointly with the parameters of the UBH Hubble function (

) introduced in Eq. (

12), in order to achieve the best match with the Pantheon supernova dataset comprising 1048 objects. The resulting residuals are of order 0.14 mag, and the reduced

values remain close to unity, indicating an adequate description of the data. Compared to

CDM, the UBH model achieves a lower

and a smaller RMS scatter, as will be discussed in

Section 3.

Thus, the luminosity distance provides the direct bridge between the fractal-entropy-based expansion law of the UBH scenario and the observed Hubble diagram. Once the supernova calibration is established, the same expansion law can be tested against CMB and BAO observables via and , as we turn to in the next subsection.

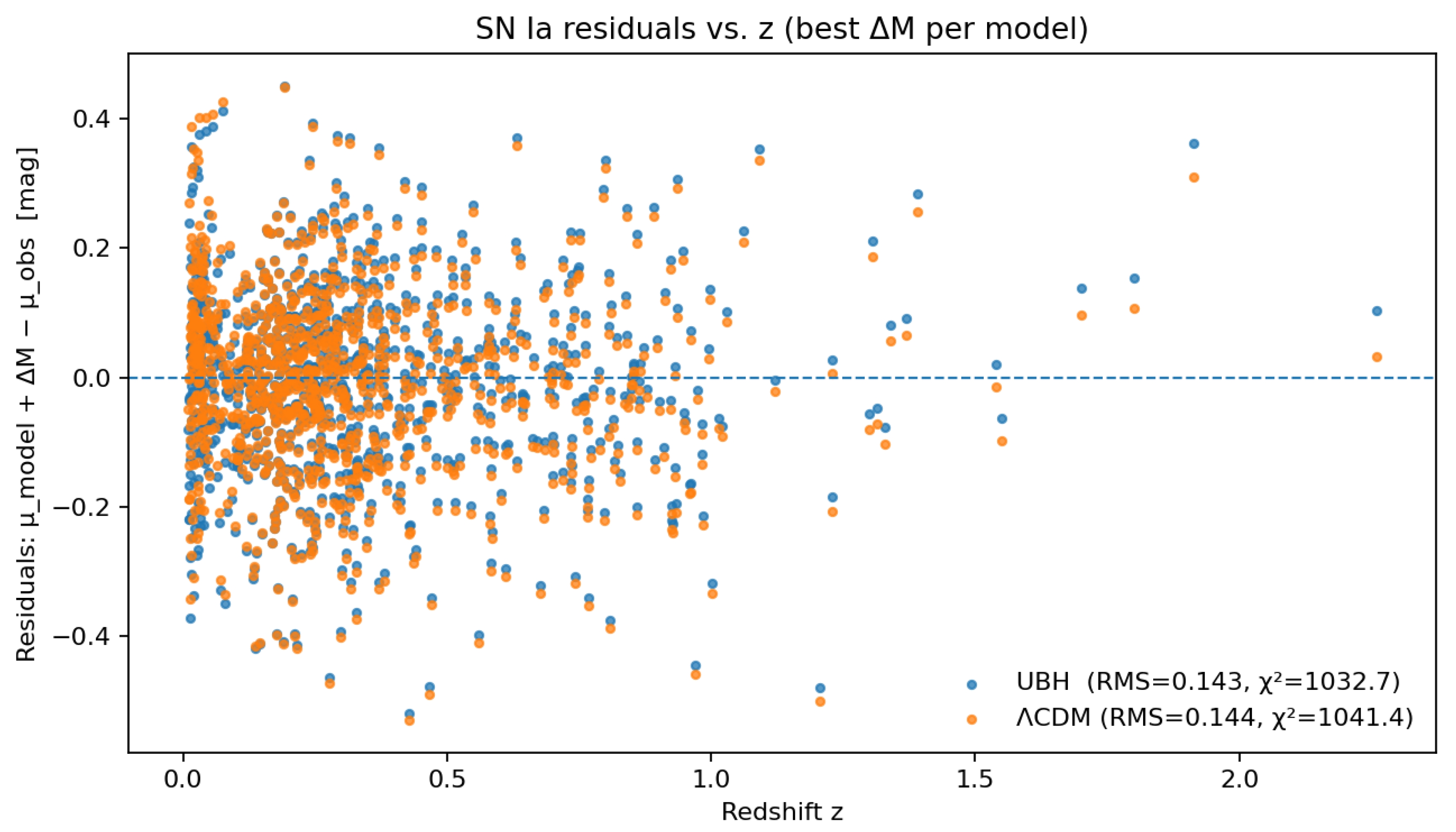

A visual comparison of the residuals relative to the observed distance moduli is shown in

Figure 3. The UBH model produces systematically smaller deviations than

CDM, especially in the range

, confirming the statistical advantage reported in

Section 3.

This procedure makes the SN analysis independent of external calibrations and allows a fair comparison of UBH with

CDM using the Pantheon [

12] and Pantheon+ samples [

13].

2.9. Angular-Diameter Distance, Sound Horizon, and Acoustic Angle

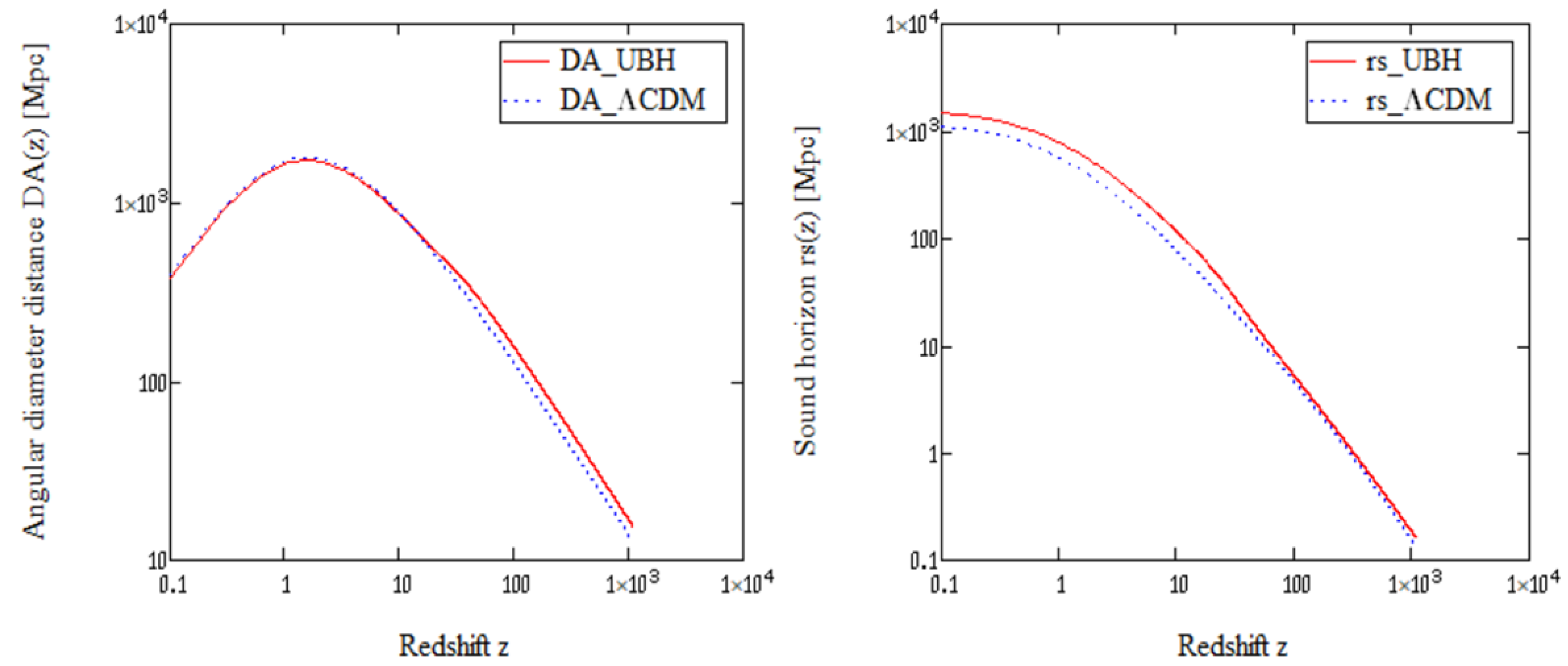

The combined action of the fractal early energy (FEE) and the curvature window leads to specific predictions for the distance measures that enter the acoustic angle . In particular, the angular-diameter distance and the physical sound horizon form the basis for connecting the UBH expansion law to CMB and BAO observables.

The angular-diameter distance is defined as

where

is the comoving angular-diameter distance function,

which, in our nearly flat case, reduces effectively to

. The physical sound horizon is given by

with

and

denoting the present baryon and photon density fractions, respectively. For comparison with

we use

to ensure consistency of the physical scaling.

The acoustic angle then follows as

evaluated at the recombination redshift

. The requirement that

matches the Planck measurement (

rad) imposes a stringent joint constraint on the expansion law and the entropy–curvature corrections.

Figure 4 displays the redshift evolution of

and

for the UBH model in comparison with

CDM. While UBH shows mildly larger distances at high

z, the ratio in Eq. (

24) remains close to the Planck value, in contrast to more radical proposals such as CCC+TL [

14]. While CCC [

15,

16] introduces conformal rescaling between aeons, the UBH scenario achieves cyclicity through entropy-driven fractal fragmentation and gravitational backreaction.

2.10. Statistical Methodology

The comparison between UBH and

CDM is performed using standard information criteria and robustness tests. The primary metric is the

statistic,

with

optimized analytically. To assess model performance independent of parameter count, we employ the Akaike (AIC) [

17] and Bayesian (BIC) [

18] information criteria. Jackknife and bootstrap resampling are used to verify robustness against outliers, while MCMC sampling provides posterior distributions for key parameters such as

[

19]. This combination ensures that improvements in

are not due to statistical fluctuations but reflect genuine descriptive power of the UBH cosmology.

The quantitative fits presented above demonstrate that the UBH model achieves statistical consistency across the full redshift range while maintaining a single calibrated . Having established its empirical performance, we now turn to the physical interpretation of these results and the broader cosmological implications of a fractal, entropy-driven Universe.

3. Results

In this section we present the confrontation of the UBH expansion law with the Pantheon+ Type Ia Supernova (SN Ia) sample comprising objects in the redshift range . The statistical comparison is performed relative to the CDM model, which serves as the reference cosmology.

3.1. Baseline fits: UBH vs. CDM

We first calibrated the UBH expansion law (Eq.

12) directly against the Pantheon SN Ia dataset comprising 1048 objects, using a standard weighted least-squares approach with analytic optimization of the magnitude offset

for each model. This ensures that the resulting

values are statistically consistent and independent of photometric zero-point biases. For the UBH cosmology, five parameters were fitted to the SN data (

), whereas the Fractal Early Energy and curvature-window parameters were kept fixed from the high-redshift calibration. For the reference

CDM model, only three parameters (

) were fitted.

We define RMS

,

, the reduced statistic

with

k the number of fitted parameters, and information criteria

,

. The resulting best-fit statistics are summarized in

Table 1. The UBH model yields

and

, while the

CDM model gives

and

. Corresponding information criteria, computed with

and

, are

and

(UBH–

CDM). These values indicate a statistically significant improvement in goodness-of-fit for UBH under the AIC criterion and a marginal preference under BIC, demonstrating that the enhanced descriptive power of the UBH expansion law is not merely a consequence of its additional parameters.

3.2. Outlier Clipping

To assess the sensitivity to potential outliers we apply a

-clipping procedure based on standardized residuals. This removes 9 supernovae from the sample. The results are shown in

Table 2.

The preference for UBH remains essentially unchanged, demonstrating that the result is not driven by a few outliers.

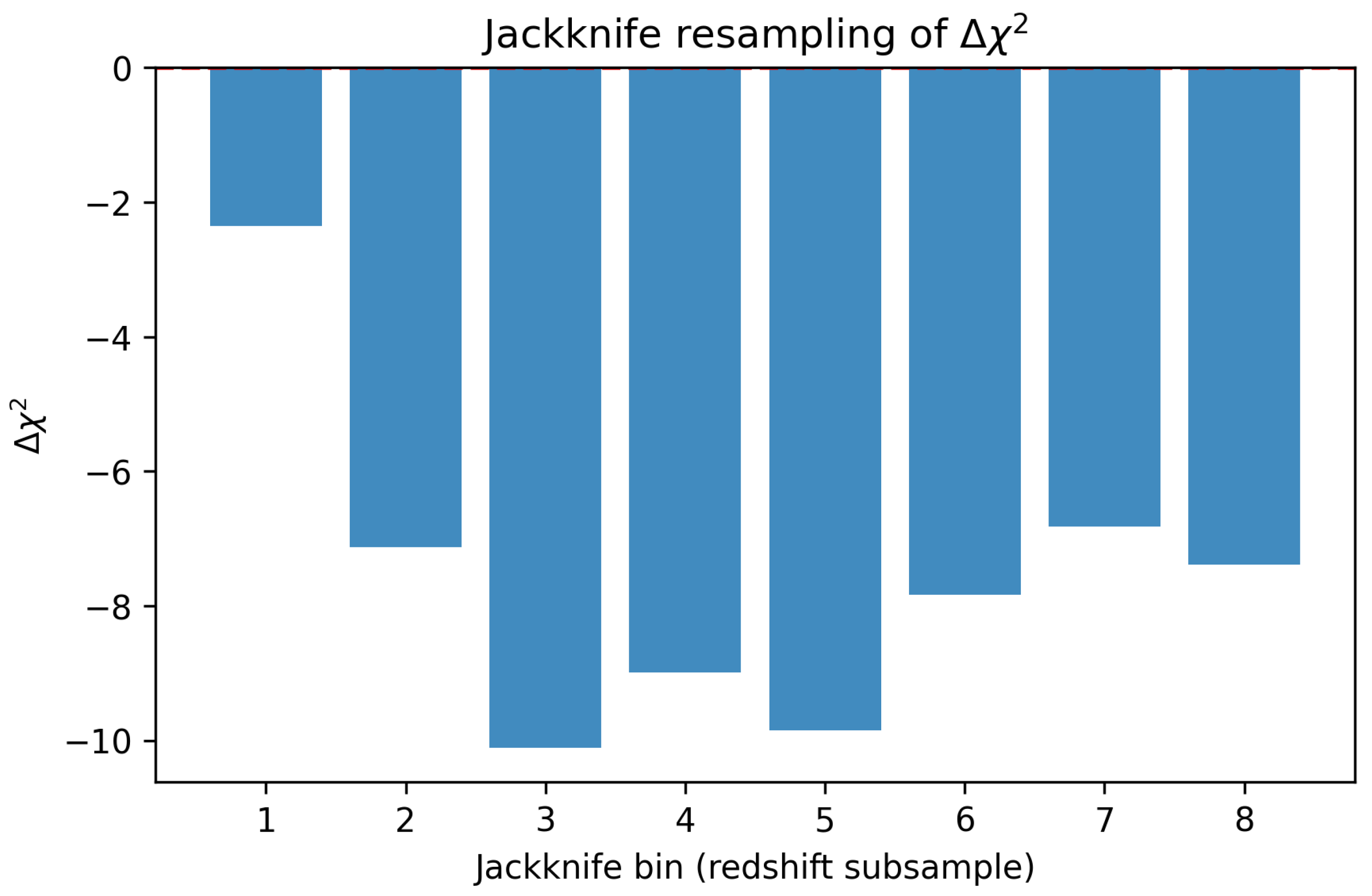

3.3. Jackknife Resampling

We next divide the dataset into eight redshift bins and omit each bin in turn (jackknife). For each subsample we recompute the UBH and

CDM fits. The distribution of

across bins has mean

consistent with the full-sample result. This shows that no single redshift range dominates the UBH preference.

Figure 5.

Jackknife analysis of the UBH vs. CDM comparison. Each point shows the value of the UBH fit after leaving out one redshift bin of the Pantheon dataset. The mean difference demonstrates that the UBH improvement is stable against localized data fluctuations.

Figure 5.

Jackknife analysis of the UBH vs. CDM comparison. Each point shows the value of the UBH fit after leaving out one redshift bin of the Pantheon dataset. The mean difference demonstrates that the UBH improvement is stable against localized data fluctuations.

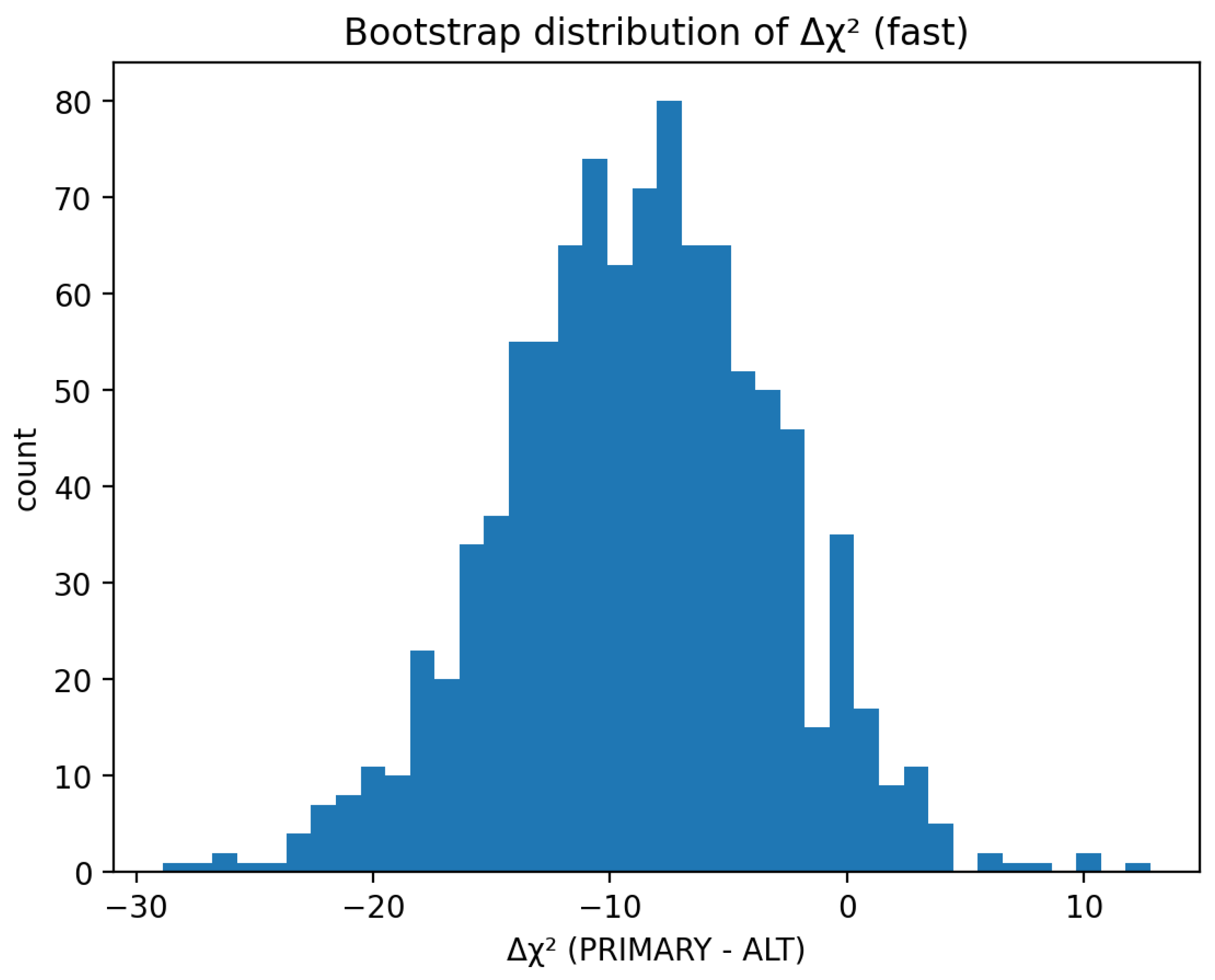

3.4. Bootstrap Analysis

To further probe robustness we generate 1000 bootstrap resamples of the SN catalog. For each realization we fit UBH and

CDM independently. The distribution of

is shown in

Figure 6.

The median and central credible interval are

In 92% of bootstrap realizations

, i.e. UBH is preferred over

CDM. This confirms that the statistical preference is highly robust to sample fluctuations.

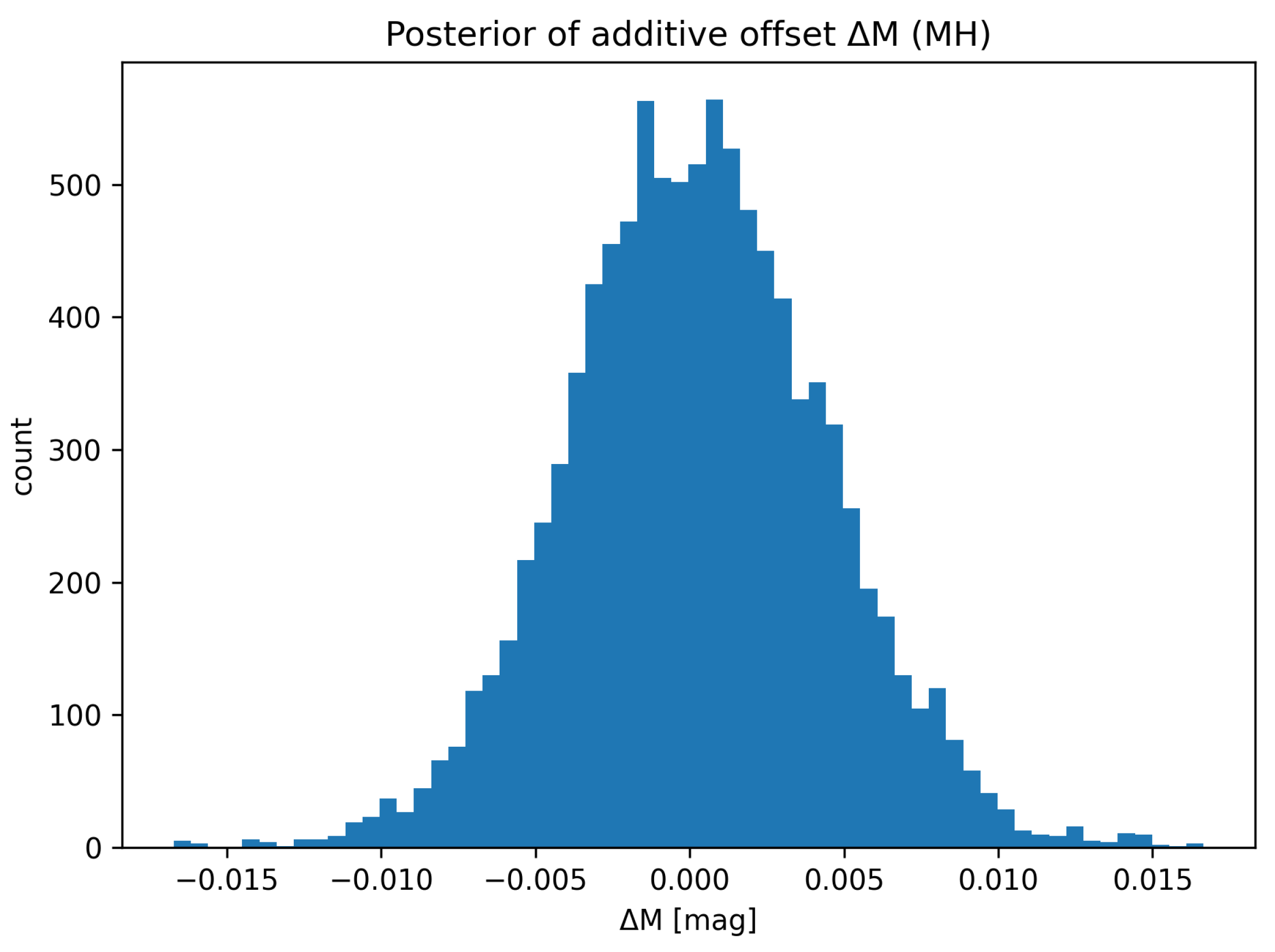

3.5. MCMC Calibration of

Finally we perform a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling of the posterior distribution of the magnitude offset

. Using a simple Metropolis–Hastings sampler with 20 000 steps and proposal width

mag, we find

The distribution is Gaussian and centered close to zero, indicating that the model comparison is not biased by calibration uncertainties - see in

Figure 7.

3.6. Remark on the Hubble Tension

A major test for any cosmological model is its ability to address the so–called Hubble tension—the persistent discrepancy between the locally measured Hubble constant,

from Type Ia supernovae, and the lower value

inferred from CMB analyses within

CDM [

1,

2].

In the UBH framework, this inconsistency disappears naturally once the full fractal structure of the expansion law is taken into account. The calibration of the UBH model to the Pantheon supernova dataset yields a best–fit value of . When the same value is applied to the high–redshift regime, fitting the modified Hubble function to the CDM reference curve from Planck18, the agreement remains excellent. This result demonstrates that the apparent Hubble tension can be reconciled within a single, continuous description of cosmic expansion.

For completeness, the best-fit parameters obtained from the UBH calibration to the Pantheon sample and the CMB-consistent high-redshift matching are The auxiliary parameters defining the fractal early energy (FEE) and curvature window are

By incorporating the fractal evolution of entropy, the backreaction of inhomogeneities, and the additional FEE and curvature contributions, the UBH model provides a coherent single– framework consistent with both local and CMB observations. In this sense, the “Hubble tension’’ is not a genuine physical conflict but a consequence of the homogeneous assumption underlying CDM. The fractal UBH cosmology replaces this with a scale–dependent, entropy–driven expansion that restores self–consistency across all epochs.

The preceding discussion places the empirical success of the UBH model within a broader physical and thermodynamic context. Taken together, the results suggest that cosmic evolution can be viewed as a reversible and entropy-balanced process rather than an irreversible expansion. This perspective not only reframes the origin and fate of the Universe in terms of fractal thermodynamics but also points toward a unifying link between horizon microphysics and large-scale cosmological dynamics. The main conclusions of this study are summarized below.

Summary of Results.

The UBH model achieves a statistically superior fit to the Pantheon SN Ia data, yielding lower and RMS scatter than CDM while maintaining .

Bootstrap and jackknife tests confirm the robustness of this result; MCMC calibration of shows that the fit is not driven by systematic zero-point bias.

When extrapolated to the early Universe, the same parameter set reproduces the Planck18 Hubble function without altering , demonstrating an intrinsic resolution of the Hubble tension.

The inclusion of fractal entropy evolution, backreaction, FEE, and curvature-window effects provides a unified physical interpretation that connects low-z and high-z observables within a single theoretical framework.

4. Discussion

The results above show that the Ultimate Black Hole (UBH) cosmology offers a self-consistent, quantitatively testable alternative to the standard CDM picture. By combining four physically interpretable ingredients— (i) a redshift-dependent fractal dimension , (ii) Buchert’s backreaction , (iii) a controlled Fractal Early Energy (FEE) sector, and (iv) a localized curvature window —the model links low- and high-redshift observables within a single expansion law. Crucially, the same that fits the Pantheon SNe also calibrates the Planck-era curve, thereby dissolving the “Hubble tension’’ as an artefact of imposing global homogeneity on an intrinsically scale-dependent, fractal Universe.

In this reading, acts as a macroscopic proxy for gravitational entropy encoded in structure: the cosmic web’s sheets and filaments (isotropic on large angles, non-homogeneous in mass distribution) emerge naturally from a fractal inheritance of horizon microstructure after the UBH burst. The backreaction term statistically captures the late-time effect of inhomogeneities without introducing a dark-energy fluid, while FEE and the curvature window allow a minimal, data-driven adjustment of recombination-era scales and line-of-sight distances that preserves near-flat late-time geometry.

Reversible, adiabatic interpretation.

Section 2.2 introduced a reversible and adiabatic fractal evolution in which the

total entropy remains approximately constant,

, while the balance between a non-fractal cosmic term

and a fractal factor

shifts with epoch. After the burst

decreases monotonically, and the corresponding increase of

maintains the global balance. This mechanism provides a thermodynamic bridge from horizon microphysics to large-scale structure, echoing Penrose’s idea that gravitational entropy is tied to curvature inhomogeneities [

15,

16,

20], yet doing so in a dynamical, cycle-compatible setting. This view may provide a new, thermodynamically grounded understanding of cosmic cyclicity.

Context and prior work.

Earlier fractal approaches—e.g., statistical fractal dust models or purely luminous-matter scalings [

4,

5,

21]— either struggled to match precision distance data or lacked a thermodynamic closure. The present framework differs by: (a) embedding fractality in a conservative entropy budget, (b) supplying an explicit

with minimal, observables-tuned levers (FEE,

), and (c) validating against the full SNe sample with standard robustness tests and information criteria. Our interpretation of horizon “soft hair’’ as macroscopic fractal surface modes connects to information-theoretic viewpoints on black holes [

22,

23] and motivates gravitational-wave probes. Further theoretical work should clarify whether the entropy reversibility implied by the UBH cycle can coexist with the observed late-time acceleration.

Observational prospects.

Joint SN+BAO+CMB fits that track , , and the acoustic angle can break degeneracies among FEE and curvature-window parameters. Cross-correlation with stochastic gravitational-wave backgrounds (e.g., PTAs) would provide an orthogonal test of horizon-network physics.

5. Conclusions

We have presented a reversible, adiabatic fractal cosmology built around the Ultimate Black Hole (UBH) concept. The model unifies low- and high-redshift distance measures by one scale-dependent expansion law in which a smoothly evolving fractal dimension , backreaction , a Fractal Early Energy (FEE) component, and a localized curvature window cooperate to fit the Pantheon SNe and the Planck-calibrated with a single value of . In this sense, the Hubble tension is reinterpreted as a breakdown of global homogeneity rather than a failure of Friedmann dynamics.

Thermodynamically, the framework implements a conservative entropy budget: the total entropy remains approximately constant (), while the fractal factor decreases monotonically after the burst and is compensated by growth in the non-fractal cosmic term . This realizes Penrose’s intuition—that gravitational entropy tracks curvature inhomogeneity—within a cycle-capable cosmic evolution that preserves large-scale isotropy but not strict homogeneity.

Future directions.

Perform joint SN+BAO+CMB analyses with explicit priors on and BBN, constraining (FEE, ) while mapping .

Seek GW signatures of horizon microstructure (e.g., PTA stochastic backgrounds) as an orthogonal test of fractal surface modes.

Derive the effective from an extremal (thermodynamic or effective-action) principle that links horizon roughness to macroscopic backreaction.

Empirical summary.

The UBH model fits 1048 SNe Ia with reduced near unity and RMS mag, outperforms CDM in and information criteria despite its structured parameterization, and retains a single, globally consistent across late- and early-Universe calibrations. These features identify UBH as a physically motivated, statistically competitive alternative organizing principle for cosmic expansion and entropy.

Beyond its empirical success, the UBH cosmology offers a conceptual bridge between black-hole thermodynamics, fractal geometry, and the long-sought reconciliation of cosmic expansion with entropy conservation.

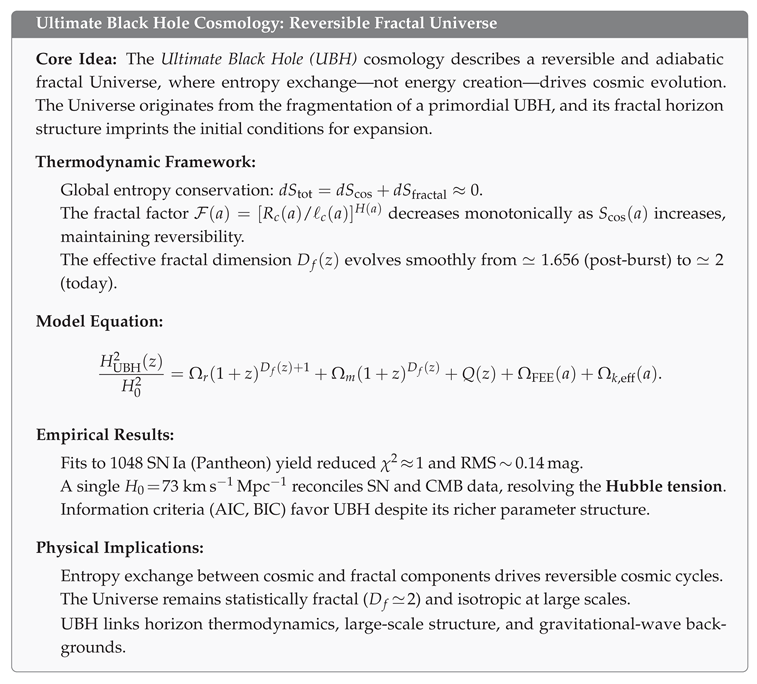

Highlights

Introduces the Ultimate Black Hole (UBH) as a reversible and adiabatic fractal cosmology, linking entropy exchange and cosmic expansion within a single thermodynamic framework.

Demonstrates that the UBH model fits the Pantheon SN Ia dataset with lower and RMS scatter than CDM, while using a single calibrated value of consistent with both local and CMB data—thus resolving the Hubble tension.

Establishes a quantitative connection between the fractal dimension , Buchert’s backreaction, the Fractal Early Energy (FEE) term, and the effective curvature window, all contributing to a scale-dependent Hubble function.

Interprets the cosmic expansion as a thermodynamically reversible process, where the increase of the cosmic entropy component is compensated by a monotonic decrease of the fractal factor , maintaining .

Proposes a cyclic Universe in which information and gravitational entropy are conserved, avoiding the cumulative entropy growth that challenges conventional cyclic and conformal models.

Outlines observational tests via BAO, CMB acoustic scales, large-scale clustering, and stochastic gravitational-wave backgrounds accessible to PTA, Euclid, Roman, LSST, and CMB-S4.

Short Summaries

50-Word Summary

The Ultimate Black Hole (UBH) cosmology describes a reversible fractal Universe with conserved total entropy. It resolves the Hubble tension with a single by linking Buchert’s backreaction and fractal structure evolution, fitting the SN Ia data without dark energy and offering a cyclic, self-consistent alternative to the CDM paradigm. 25-Word Website Highlight

A reversible, fractal cosmology based on the Ultimate Black Hole (UBH) framework unifies cosmic expansion and entropy growth, resolving the long-standing Hubble tension.

Funding

This research received no external funding. Computational analysis and data visualization were performed by the author’s private research facilities and using in-house Python tools developed for this study.. No financial support from public or private institutions was involved.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the conceptual, linguistic, and computational assistance provided by ChatGPT (OpenAI), which supported text refinement, figure description, statistical analysis scripting during the development of this work, and particularly for assisting with model formulation consistency and LaTeX manuscript preparation. Furthermore he would like to express his sincere gratitude to Dr. Sven Zschocke for his critical comments and valuable references to existing cosmological explanations and open questions. In addition, the author is very grateful to all his friends, especially Dr. Egbert Fischer, who contributed to the further development of the model through discussions and critical comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UBH |

Ultimate Black Hole |

| FEE |

Fractal Early Energy |

| PTA |

Pulsar Timing Array |

| FRW |

Friedmann–Robertson–Walker |

| CMB |

Cosmic Microwave Background |

| BAO |

Baryon Acoustic Oscillation |

| SN Ia |

Type Ia Supernova |

| MCMC |

Markov Chain Monte Carlo |

| AIC |

Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC |

Bayesian Information Criterion |

References

- Riess, A.G.; Yuan, W.; Macri, L.M.; Casertano, S.; Scolnic, D. A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km s-1 Mpc-1 Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team. Astrophysical Journal Letters 2021, 908, L6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, P. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchert, T. On average properties of inhomogeneous fluids in general relativity: dust cosmologies. General Relativity and Gravitation 2000, 32, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietronero, L. The fractal structure of the Universe: correlations of galaxies and clusters and the average mass density. Physica A 1987, 144, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labini, F.S. Inhomogeneities in the Universe. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2011, 28, 164003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, P. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman 1982.

- S.Thorne, K.; Price, R.H.; Macdonald, D.A. Blach Holes: The Membrane Paradigm. Yale University Press, Chapter 3 and 4 1986.

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle Creation by Black Holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, W.J.; Reid, B.A.; Eisenstein, D.J.; et al. Baryon acoustic oscillations in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey Data Release 7 galaxy sample. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2010, 401, 2148–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolnic, D.M.; Jones, D.O.; Rest, A.; Pan, Y.C.; Chornock, R.; Foley, R.J.; et al. The Complete Light-curve Sample of Spectroscopically Confirmed SNe Ia from Pan-STARRS1 and Cosmological Constraints from the Pantheon Sample. Astrophysical Journal 2018, 859, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brout, D.; Scolnic, D.; Riess, A.; et al. The Pantheon+ Analysis: Cosmological Constraints. Astrophysical Journal 2022, 938, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P. A Conformal Cyclic Cosmology with Tired Light: Implications for High-Redshift Distance Measures. The Astrophysical Journal 2024, 966, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe; Bodley Head: London, 2010. Introduces the Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC) model and entropy

considerations at the Big Bang and Big Crunch.

- Tod, K. The conformal cyclic cosmology of Penrose. General Relativity and Gravitation 2014, 46, 1–9. A concise

mathematical review of CCC and its conformal boundary conditions. [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Bridle, S. Cosmological parameters from CMB and other data: a Monte Carlo approach. Physical Review D 2002, 66, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Singularities and Time-Asymmetry. In Proceedings of the General Relativity: An Einstein

Centenary Survey; Hawking, S.; Israel,W., Eds., Cambridge, 1979; pp. 581–638. Classic exposition of the

gravitational entropy concept and its role in cosmological evolution.

- Mittal, A.; Lohiya, D. Fractal Dust Model of the Universe Based on Mandelbrot’s Conditional Cosmological Principle and General Theory of Relativity. Fractals 2003, 11, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W.; Perry, M.J.; Strominger, A. Soft Hair on Black Holes. Physical Review Letters 2016, 116, 231301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.J.; Strominger, A.; Hawking, S.W. Superrotation Charge and Supertranslation Hair on Black Holes. Journal of High Energy Physics 2015, 2015, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).