1. Introduction

The tropical rock lobster (

Panulirus ornatus) is one of the most economically valuable species in lobster aquaculture, with international demand rising annually [

1,

2,

3]. However, the aquaculture production remains stagnant [

4], due to reliance on trash fish and mixed fisheries bycatch-feed sources that are inconsistent and unsustainable [

5]. Development of formulated feed, therefore, is urgently needed to support the production of lobster aquaculture [

6].

Despite quantification of macronutrient requirements of lobsters, feed acceptability remains a primary limitation to implementation of formulated feeds [

7,

8,

9], likely due to unsuitable texture. As selective feeders, spiny lobsters accept or reject feed based on tactile evaluation by mechanoreceptors located in their mouthparts [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Inadequate feed texture often results in significant leachate loss and feed wastage, thereby reducing apparent feed intake and presenting a major challenge in developing effective formulated feed for spiny lobsters [

6,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Feed binders, essential components in formulated feeds, are responsible for maintaining pellet integrity, water stability, and texture. Binders are typically classified as natural (e.g., wheat gluten, starch-based products, transglutaminase), modified (e.g., alginate, gums), or synthetic (e.g., formaldehyde, synthetic resin), each offering distinct contributions to pellets structure and durability [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Despite their ubiquitous use in formulated feeds [

22], the comparative impact of these binders on feed texture and lobster feeding behaviour remain poorly understood.

While previous research has commented on the importance of texture on feed intake in lobsters, this has yet to be quantified, making optimisation challenging. Further, texture has been defined in relation to moisture content, making ‘soft’ or ‘hard’ pellets [

8,

23] which are unlikely to reflect mechanical texture properties such as resistance to tension or compression forces [

24]. Therefore, a more comprehensive assessment is required to accurately quantify the texture based on quantitative and objective measures.

Rather than broadly examining binder chemistry, the present study focuses on the comparative evaluation of key binder types to determine how they influence feed texture, feeding behaviour and apparent feed intake in

P.

ornatus. The use of computer-aided behaviour analysis allows more detailed research in this field [

25]. To date, no scientific report has identified the optimal feed texture, achieved through appropriate binder selection, for enhancing feeding behavior and apparent feed intake of

P. ornatus.

This study, therefore, aims to fill a critical gap in our knowledge of how binders influence feeding behaviour and apparent feed intake tropical rock lobster (P. ornatus) through manipulating feed texture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Design Experiment

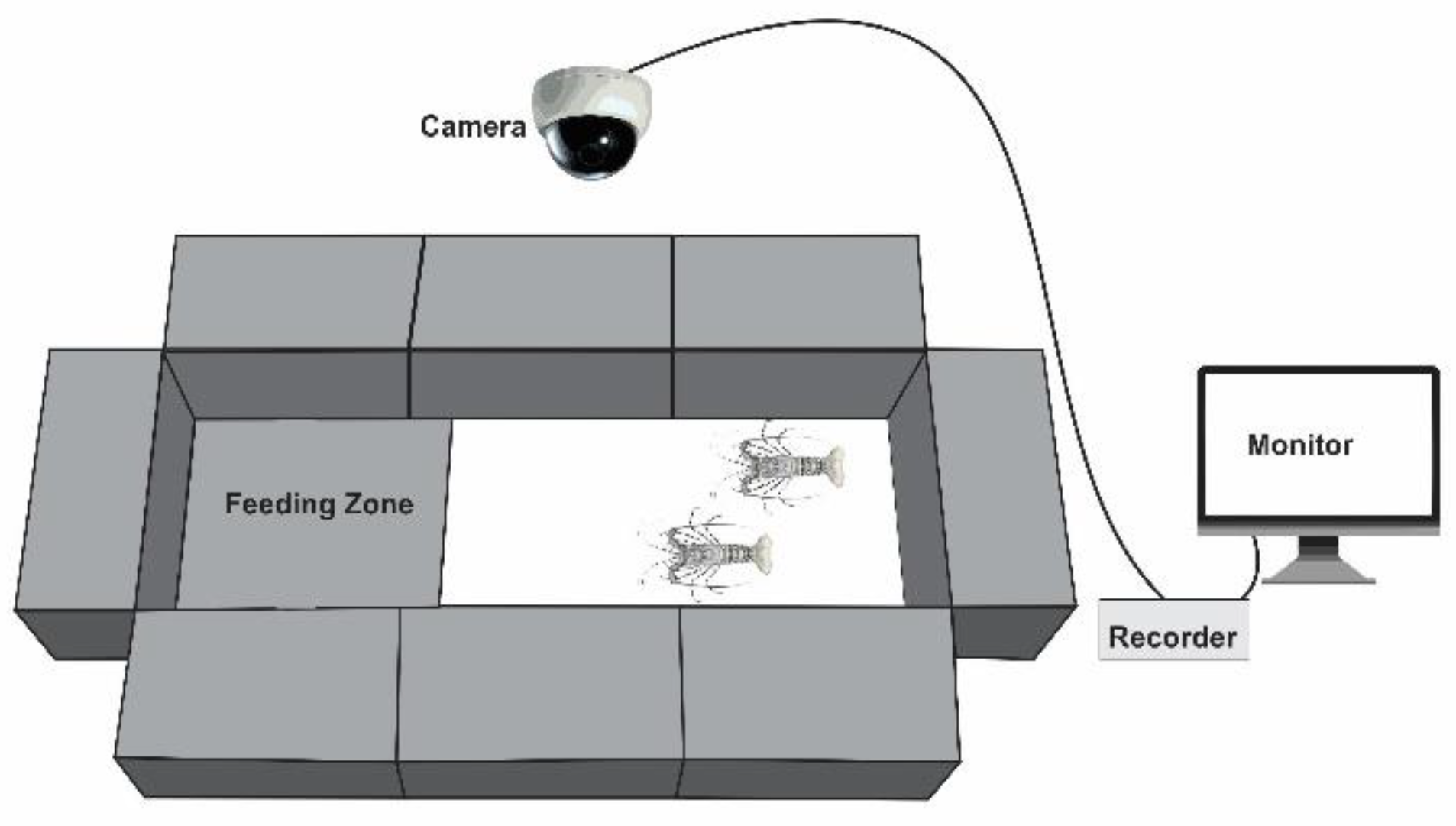

Fifty juveniles of

P. ornatus (46.10 ± 1.14 g) were sourced from the Ornatas Hatchery Facility in Toomulla Beach, Queensland, Australia. Two lobsters were placed in each of 25 rectangular tanks with a capacity of 78 L and a water flow rate of approximately 16 L min⁻¹. The animals were acclimated for two weeks prior to the start of the experiment and were fed the control diet (described in

Section 2.2) during this period. The recirculating system maintained stable water quality parameters: pH 8.47 ± 0.03, temperature 27.8 ± 0.1 °C, salinity 35.3 ± 0.4 ppt, dissolved oxygen 114.5 ± 0.5% saturation, ammonia 0 mg L⁻¹, nitrite 0.1 ± 0.1 mg L⁻¹, and nitrate 18 ± 1.8 mg L⁻¹. Each tank was equipped with textured flooring and a designated feeding zone (

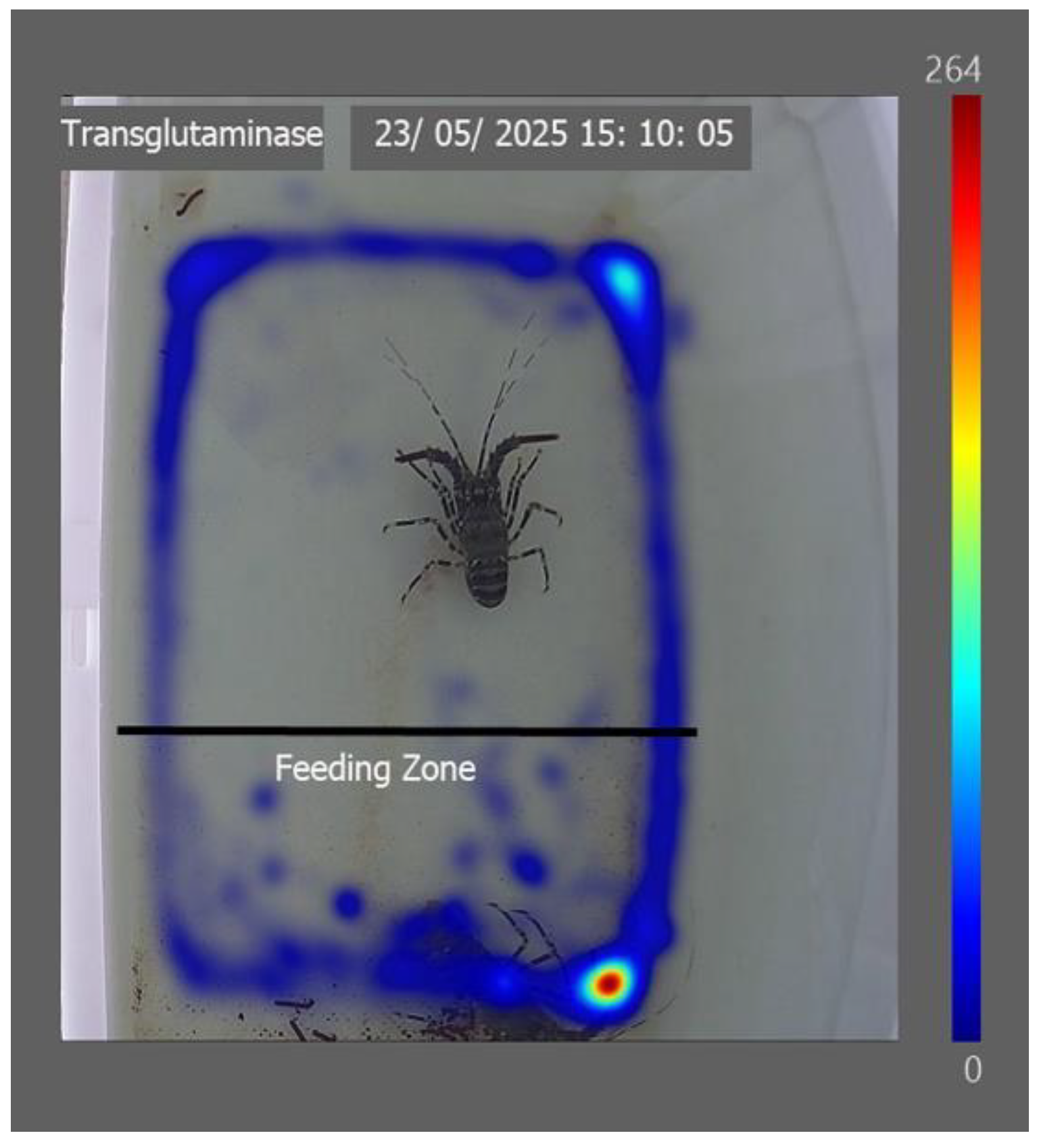

Figure 1). To simulate natural light conditions, tanks were covered with 90% UV-blocking shade cloth and maintained on a 12-hour light:12-hour dark photoperiod. A behavior monitoring system was installed in each tank using an AHD 1080p PIR Bullet Camera (Concord Camera Corporation, Hollywood, USA) mounted overhead. Cameras were connected to a Concord HD DVR system with infrared capability.

A completely randomised design was used, with five different diets as treatments and five replications per treatment. Diet A (control) contained wheat gluten as a binder, while diet B included wheat gluten and xanthan gum as binders. The remaining diets used the same binder as the control diet, with the addition of guar gum in Diet C, alginate in Diet D, and transglutaminase in Diet E.

2.2. Feed Production

The feed formulations (

Table 1) were based on Nankervis and Jones [

17]. The control diet was prepared by mixing the dry ingredients in an A200 Planetary Mixer (Hobart, Troy, USA). Liquid ingredients (lecithin, glycerol, mussel homogenate and water at 60% v/w of the dry ingredients) were blended separately. Mussel homogenate was obtained by homogenizing mussel flesh with distilled water in a 5:1 (w/v) ratio. The dry materials were ground using an SR300 Rotor Beater Mill (Retsch, Haan, Germany) fitted with a 200 µm screen. The dry mix was then combined with the liquid ingredients and mixed thoroughly. The feed mixture was pelletised using a Dolly Pasta Machine (LA Monferrina S.P.S., Moncalieri, Italy) equipped with a 3 mm die plate and cut into strands 20–30 mm in length. The pellets were dried at 50 °C in a TD-700F Premium Dehydrating Oven (Thermoline, Wetherill Park, NSW) until a final moisture content of approximately 30% was reached. The finished pellets were stored at –17 °C until use [

21]. Diets B, C, D, and E were prepared by incorporating 5% (w/w) of xanthan gum, guar gum, alginate, and transglutaminase, respectively, into 95% of the control diet.

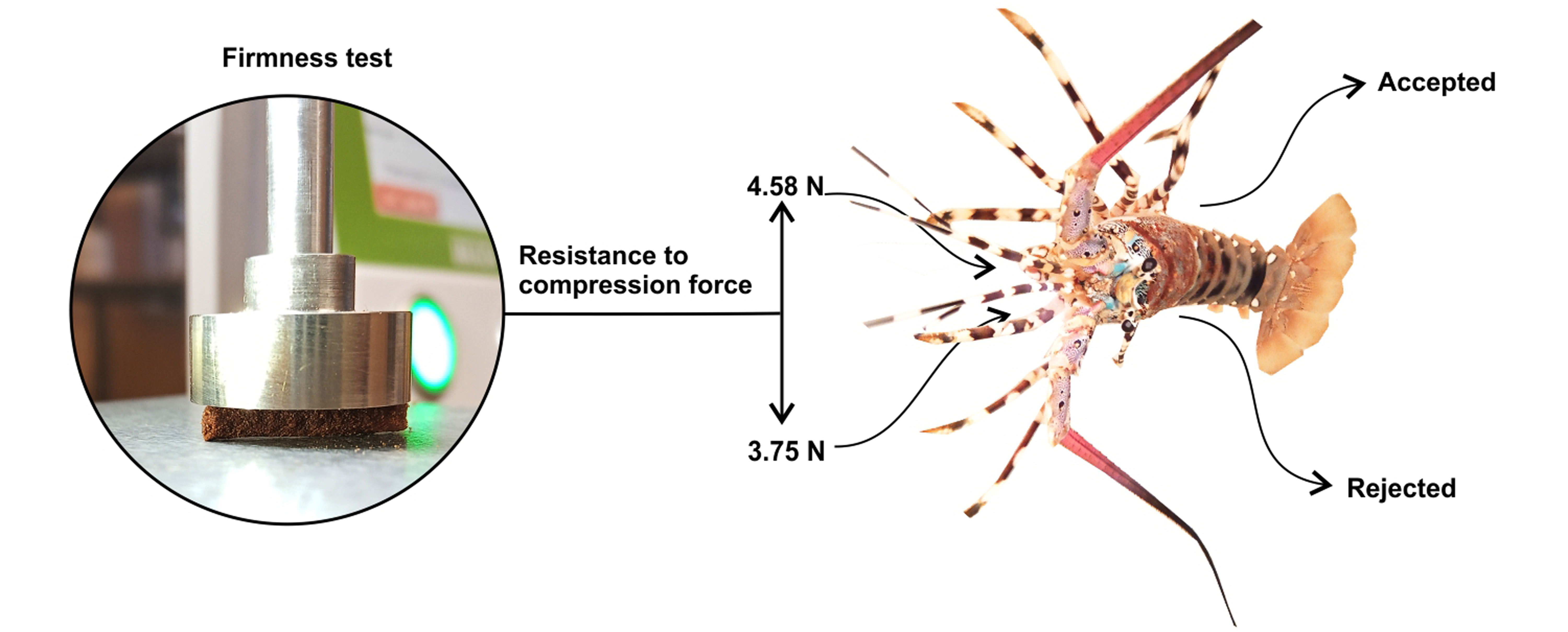

2.3. Texture Measurement

Tensile and firmness tests were performed using a FRTS 100-N Texture Analyzer (IMADA, Japan). The tensile test was conducted by securing a 30 mm pellet strand at either end with clamps which were separated at a constant rate (5.0 mm/min) until fracturing, at which point the force was measured. The firmness test applied lateral compression using a 20 mm diameter disk probe, measuring the force required to compress a 3 mm diameter pellet by 1 mm.

2.4. Feeding Behaviour Recording and Analysis

During the 14-day trial, the lobsters were fed once daily at approximately 15:00, at a feeding rate of 1.5% of body weight. The feed was placed in the designated feeding zone, and feeding behavior was recorded for two hours after feed was offered, as most attractants in the pellets are released within this period [

26]. The video recordings were analysed using EthoVision XT 18 software (Noldus, Netherlands) to determine the time spent in feeding zone, the first-time interaction with feeding zone, and the frequency of moving in and out of feeding zone [

25].

2.5. Apparent Feed Intake Determination

The apparent feed intake was calculated based on Fitzgibbon et al. [

27]. Excess feed was collected each morning by siphoning. The siphoned material was captured using a 50 µm mesh screen. Excess feed was categorised into two types based on visual observations: Non-Feeding Related Waste (NFRW), representing entirely uneaten pellets, and Feeding Related Waste (FRW), indicating feed that was partially consumed or masticated during feeding activity. Collected samples were stored frozen at –17 °C until further analysis. Additionally, nutrient leaching was assessed for all diets by immersing feed (at 1.5% of body weight) overnight in tanks without lobsters, in triplicate, before being recovered and quantified in the same way as experimental feeding. All recovered excess feed samples were gently rinsed with deionized water to remove salts and then filtered in a Buchner funnel with MicroScience qualitative filter paper grade MS 2 size 185 mm. Samples were dried at 105 °C for 24 hours in a TD-700F Premium Dehydrating Oven (Thermoline, Wetherill Park, NSW). Apparent feed intake (% body weight) was calculated as:

The recovery factor was calculated as:

2.6. Data Analysis

Data were tested for homogeneity of variance using Levene’s test and normality with Shapiro-Wilk W. One-way ANOVA was used to detect differences among treatment means, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test where significant differences occurred (p < 0.05). Leachate loss and excess feed data were log transformed. A non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed for quantitative feeding behaviour data as the transformation was not effective. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 30.

3. Results

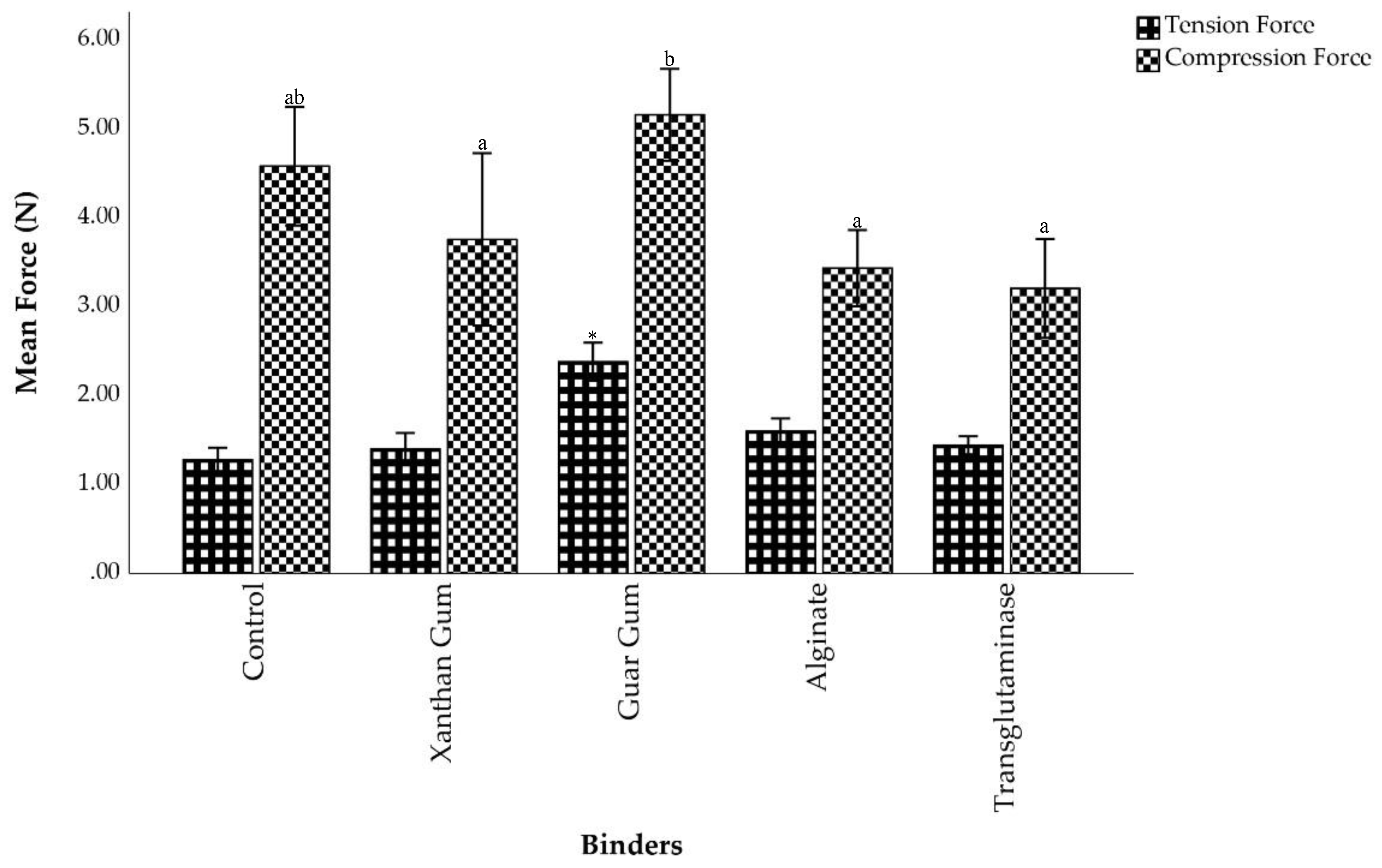

3.1. Texture of Pellets

Among all treatments, pellets bound with guar gum exhibited the highest resistance to tension force, followed by those with alginate (

Figure 2). Specifically, the tensile strength of control pellets was 1.28 ± 0.07 N. The strength increased slightly to 1.40 ± 0.09 N in the xanthan gum pellets. Alginate and transglutaminase treatments enhanced the resistance to tension force by 25% and 12.5%, yielding tensile strength of 1.60 ± 0.07 N and 1.44 ± 0.05 N, respectively. The greatest resistance to tension force was 2.38 ± 0.11 N, achieved by guar gum pellets, which was significantly higher than all other feeds (p < 0.05)

The resistance to compression force in control pellets was 4.58 ± 0.33 N. This value decreased to 3.75 ± 0.49 N, 3.43 ± 0.21 N, and 3.20 ± 0.62 N in pellets formulated with xanthan gum, alginate, and transglutaminase, respectively. In contrast, guar gum showed the highest resistance to compressive stress (5.15 ± 0.26 N). Statistical analysis confirmed that there was no significant difference between control and guar gum pellets (p > 0.05). However, statistically significant differences were detected between guar gum and all other binders (p < 0.05).

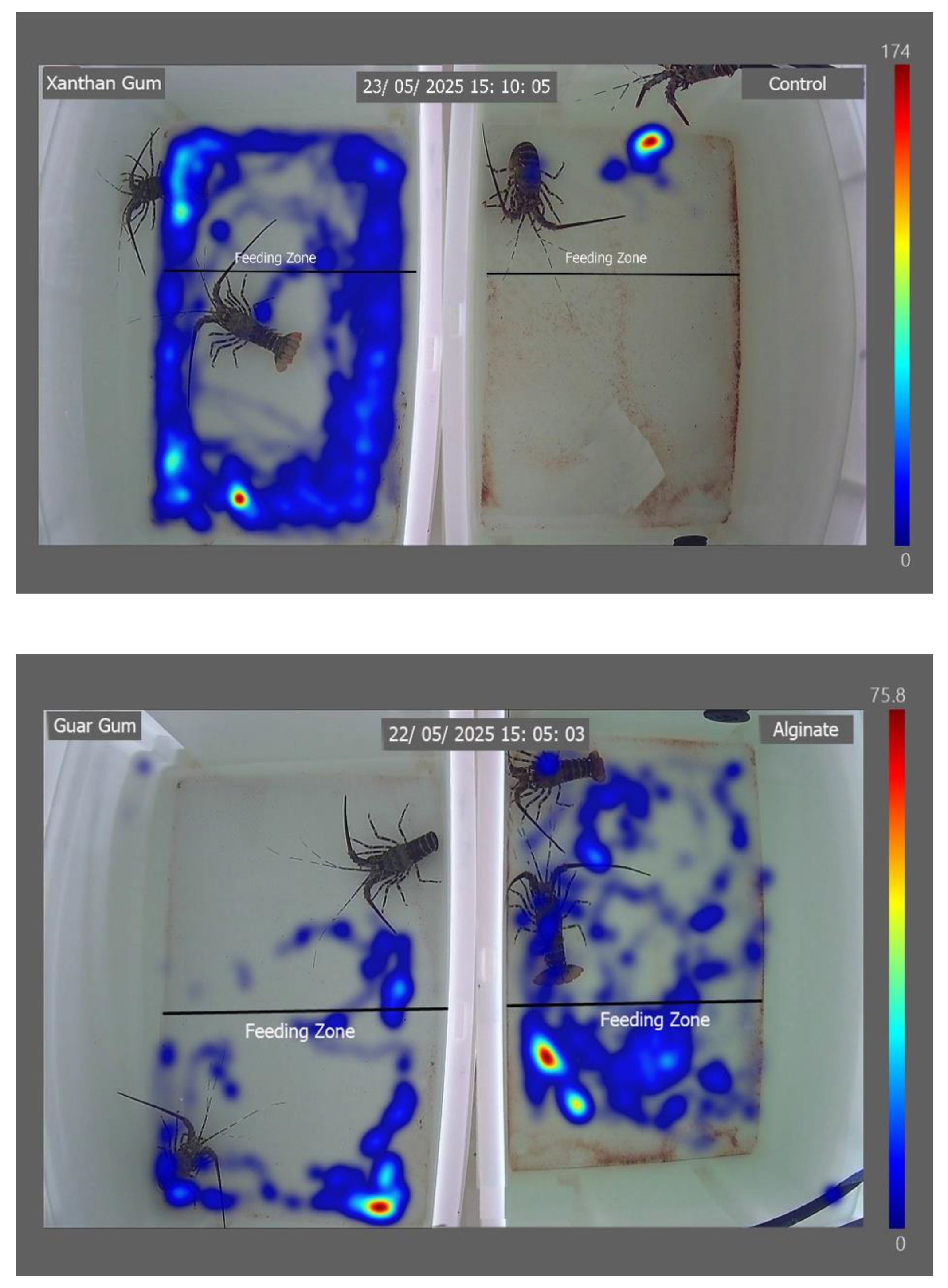

3.2. Feeding Behaviour of Lobsters

Lobsters fed with the control diet remained in the feeding zone throughout the observation period (

Figure 3). In contrast, individuals receiving the xanthan gum treatment were detected outside the feeding zone for extended periods. Lobsters fed diets containing guar gum, alginate, and transglutaminase spent a greater proportion of time within the feeding zone. However, they were also frequently detected outside the feeding zone.

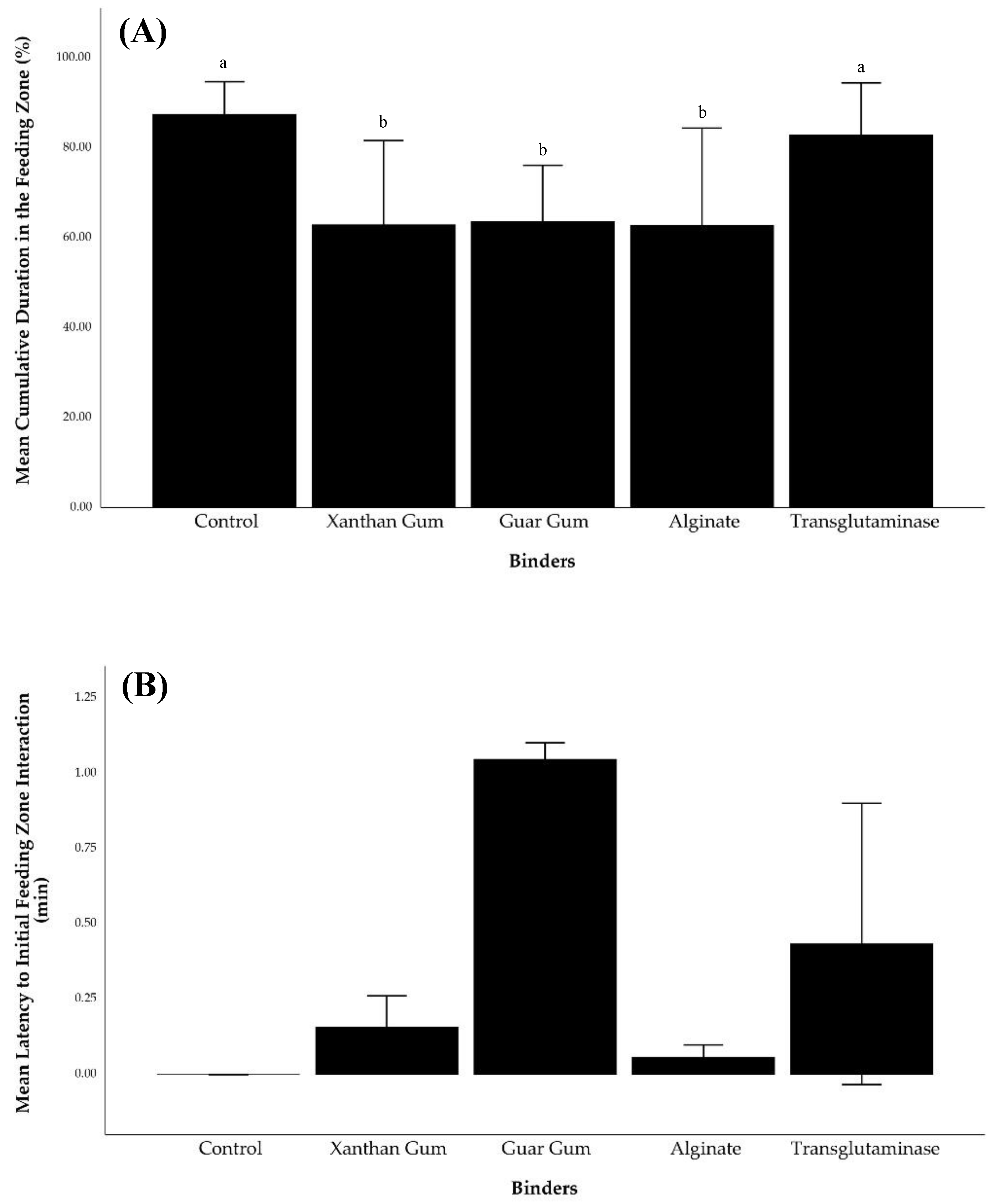

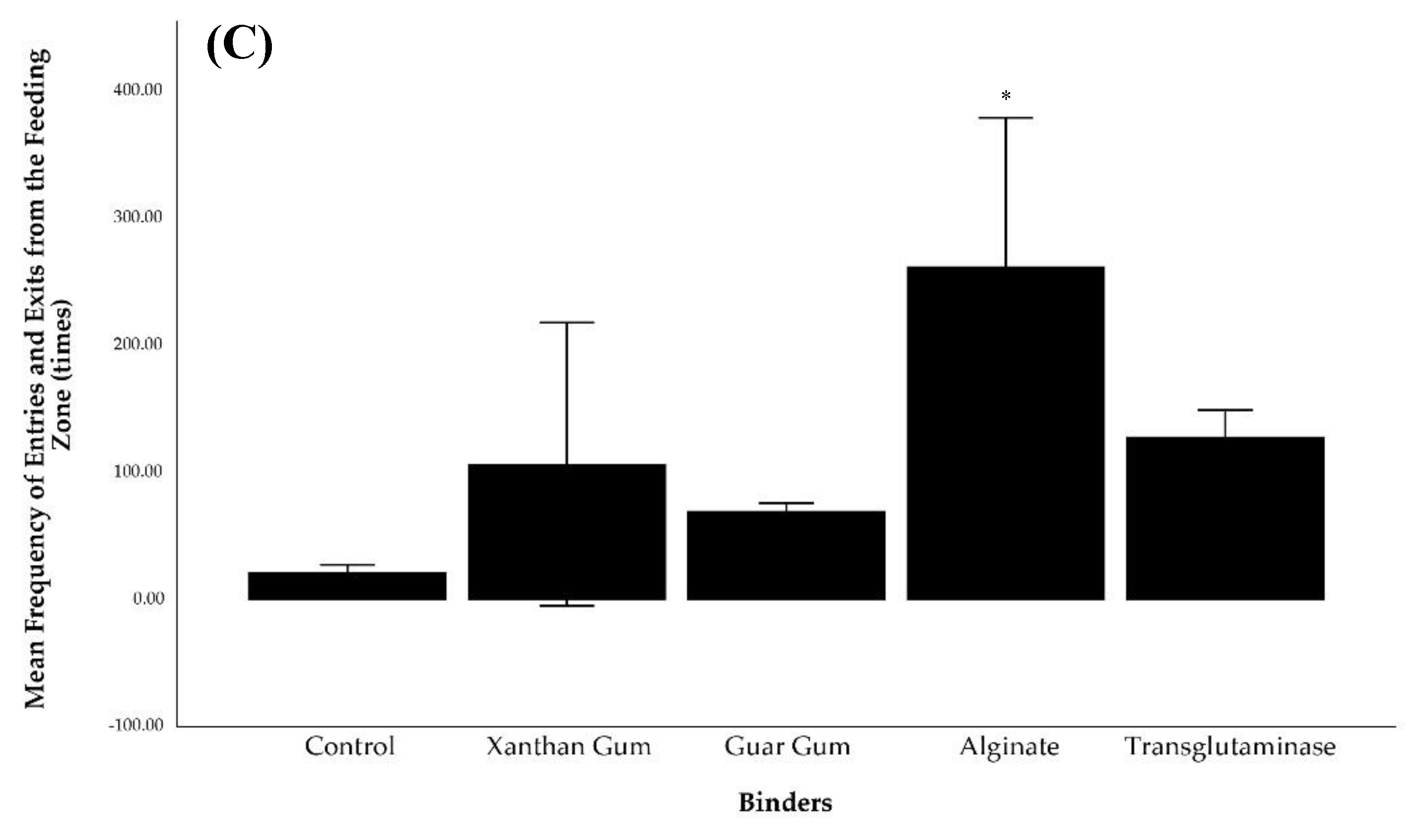

The longest cumulative duration in the feeding zone (87.46 ± 3.63%) was recorded for lobsters fed control pellets (

Figure 4). Their initial interaction with the feeding zone was 0.00 ± 0.00 minutes as they started in the feeding zone before feed was added. Additionally, they exhibited the lowest frequency of entering and exiting the zone (21.67 ± 2.91 times). Lobsters fed xanthan gum pellets had the lowest cumulative duration in the feeding zone (62.89 ± 9.36%), with a delayed first interaction (0.16 ± 0.05 min) and a markedly high frequency of movement in and out of the zone (106.67 ± 55.67 times).

Lobster fed with guar gum, alginate, and transglutaminase bound pellets showed higher frequencies entering and leaving the feeding zone, resulting in a lower cumulative duration in the feeding zone than those fed the control pellets. Additionally, time to initially entering the feeding zone for guar gum (1.05 ± 0.03 minutes), alginate (0.06 ± 0.02 minutes), and transglutaminase (0.43 ± 0.23 minutes) treatments was also longer than the control treatment.

Statistical analyses revealed significant differences (p < 0.05) in cumulative duration within the feeding zone between the control group and other treatments (xanthan gum, guar gum, and alginate). Additionally, the frequency of entering and exiting the feeding zone differed significantly between the alginate and the other dietary treatments (p < 0.05).

3.3. Apparent Feed Intake, Leachate Loss, and Excess Feed

The control diet exhibited the highest apparent feed intake and lowest excess feed (

Table 2). Specifically, the highest apparent feed intake in the control group was 0.98 ± 0.05 % body weight (BW)/day, followed by transglutaminase (0.89 ± 0.03% BW/day), alginate (0.87 ± 0.09% BW/day), and guar gum (0.85 ± 0.07% BW/day). Xanthan gum resulted in the lowest apparent feed intake (0.76 ± 0.08% BW/day). Additionally, leachate loss was lowest in the control diet and alginate treatments, measured at 23.73 ± 1.01% dry matter (DM) and 23.44 ± 1.15% DM, respectively. In contrast, diets containing xanthan gum (26.59 ± 0.79% DM), guar gum (26.47 ± 1.11% DM), and transglutaminase (26.37 ± 1.00% DM) exhibited approximately 3% higher leachate loss.

The control diet also yielded the lowest total excess feed (0.62 ± 0.26 g DM), with no detectable non-feeding-related waste (NFRW). Consequently, all excess feed was attributed to feeding-related waste (FRW), which was the highest among treatments (0.62 ± 0.29 g DM). Transglutaminase treatment produced a comparable amount of excess feed (0.69 ± 0.04 g DM), comprising both non-feeding-related waste (0.18 ± 0.07 g DM) and feeding-related waste (0.51 ± 0.07 g DM). Xanthan gum produced the highest total of excess feed (1.24 ± 0.38 g DM) among all treatments, followed by guar gum (0.97 ± 0.34 g DM) and alginate (0.80 ± 0.21 g DM). Each of these binders contributed to both non-feeding-related waste and feeding-related waste. Statistical analyses revealed no significantly different apparent feed intake, leachate loss, and excess feed (p > 0.05) among treatments.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that pellet texture, governed by binder type, played a decisive role in optimising the feeding response of

P.

ornatus. Among all treatments, pellets formulated solely with wheat gluten binder significantly enhanced feeding behaviour and apparent feed intake, likely due to their balanced firmness, cohesion, and palatability. Additionally, these pellets exhibited low leachate loss and strong structural integrity, suggesting that this binder effectively limits water infiltration and maintains pellet stability during immersion. Such mechanical stability, combined with suitable tactile resistance, is essential because lobsters rely heavily on mechanoreceptors to assess feed texture and will reject pellets that are too hard or too soft for mastication [

28]. Importantly, non-feeding related waste was minimal indicating high acceptance and efficient consumption. These findings align with previous research reporting superior water stability and growth performance in

P. ornatus fed wheat gluten pellets relative to alginate-based formulations [

29]. Taken together, these findings confirm that wheat gluten provides a more appropriate textual balance than the additional binders, enhancing both feed quality and feeding efficiency.

In contrast, xanthan gum produced pellets that were moderately durable but lacked sufficient firmness, and this texture did not improve feeding behaviour. Lobsters fed pellets containing xanthan gum exhibited frequent movements in and out of the feeding zone, reflecting extended exploratory or orientation behaviour rather than active feeding [

30,

31]. The higher leachate loss and excess feed also indicate poor water stability and limited nutrient retention, leading to the lowest apparent feed intake among treatments. These observations highlight that increasing pellet durability alone is insufficient to optimise feeding performance.

Guar gum addition produced the most durable and firm pellets, yet these mechanical advantages did not translate into improved feeding outcomes. Lobsters remained longer in the feeding zone but showed delayed initial feeding responses, suggesting guar gum retarded attractant release, thereby reducing early pellet appeal. Although leachate loss was slightly lower than that of xanthan gum, guar gum pellets tended to swell and crack upon immersion, leading to inefficient mastication and higher feed wastage. These findings align with previous studies reporting that pellets containing more than 2% guar gum exhibited rapid swelling and cracking, which negatively impacted feed intake [

32,

33].

Alginate-based pellets were slightly durable but less firm than wheat gluten, and this texture failed to optimise feeding behaviour. Lobsters required a longer orientation period before initiating feeding which is detrimental because nutrient leaching becomes substantial within the first two hours of immersion [

34]. Despite low leachate loss, alginate bound diets resulted in reduced feed intake, implying that physical stability alone does not ensure palatability. Previous research has similarly reported poor digestible and growth performance in spiny lobsters and reduced feed intake in rainbow trout when alginate was used as a binder [

29,

33,

35].

Transglutaminase produced textural characteristics comparable to xanthan gum and alginate resulting in pellets that were moderately durable but less cohesive. Lobsters frequently masticated these pellets, yet the high frequency of entering and exiting the feeding zone reflected interrupted feeding activity. Elevated leachate loss and feed residues further indicated poor water resistance and limited palatability. Although strong binding efficiency has been reported in other feeds that use transglutaminase as a binder [

29,

36], its cost and moderate textural performance limit its practical application in lobster feed formulation.

Comparatively, wheat gluten alone provides the most balanced combination of mechanical strength, water stability and tactile acceptability, resulting in superior feeding responses. Guar gum, alginate, and transglutaminase produced textures that were either excessively firm or insufficiently cohesive, while xanthan gum offered moderate durability but poor palatability due to high leachate loss. These contrasts demonstrate that binder-driven pellet texture directly governs lobster feeding efficiency through a delicate balance between structural integrity and tactile perception. Thus, among the evaluated binders the use of wheat gluten as the sole binder optimised feeding performance, aligning with the study’s objective of identifying functional binders for improved formulated diets in P. ornatus. This study clearly indicates that binder selection is pivotal in formulating textured feeds that support optimal feeding behaviour and nutrient utilisation in P. ornatus.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comparative evaluation of five binders to determine their effectiveness in optimising feeding performance in P. ornatus. Among the tested binders, wheat gluten alone produced pellet textures that most effectively enhanced feeding behaviour and apparent feed intake, demonstrating an ideal balance between firmness, cohesion, and palatability. Guar gum generated the firmest pellets but reduced feeding activity, whereas xanthan gum, alginate, and transglutaminase produced moderately durable yet less cohesive textures that failed to maintain feeding engagement.

Overall, the study emphasises the critical role of binder selection in developing nutritionally balanced, behaviourally acceptable, and cost-effective formulated feeds for P. ornatus. Future work should explore synergistic combinations of natural binders and assess long-term growth and nutrient utilisation outcomes to further refine binder optimisation strategies.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. M.I. and N.H. were responsible for material preparation, data collection, and data analysis. M.I. drafted the initial version of the manuscript, and all authors provided critical feedback and revisions. S.K.D., C.J., and L.N. led the conceptualization, review, and final editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final published version.

Funding

Open access funding for this publication was provided and facilitated by James Cook University. This research forms part of Muhsinul Ihsan’s Ph.D. project at James Cook University and is supported by the Beasiswa Indonesia Bangkit scholarship program—a collaborative initiative between the Ministry of Religious Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia and the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP), under award number PG08-222-0006659.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ornatas Company for providing the experimental animals and technical support essential to this study. Acknowledgment is also extended to the team at the JCU Tropical Aquaculture and Innovation Lab (JCU TAIL) for their valuable support and contributions. During manuscript preparation, the author utilized AI tools (Copilot) to enhance clarity and readability. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BW |

Body Weight |

| DM |

Dry Matter |

| SEM |

Standard Error of Mean |

| NFRW |

Non-Feeding Related Waste |

| FRW |

Feeding Related Waste |

References

- Jones, C. , Market perspective on farmed tropical lobster. In Proceedings of the International Lobster Aquaculture Symposium, Lombok, Indonesia, 22-25 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2024 – blue transformation in action; Rome, 2024.

- FAO GLOBEFISH information and analysis on markets and trade of fisheries and aquaculture products. Available online: Species Analysis Lobster | Globefish | FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation. (accessed on 16/10/2025).

- Jones, C.M.; Anh, T.L.; Priyambodo, B. Lobster aquaculture development in Vietnam and Indonesia. In Lobsters: Biology, Fisheries and Aquaculture; Radhakrishnan, E.V.; Phillips, B.F.; Achamveetil, G., Eds.; Springer, Singapore, 2019, pp. 541-570.

- Jones, C.M. Progress and obstacles in establishing rock lobster aquaculture in Indonesia. Bulletin of marine science 2018, 94, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nankervis, L.; Jones, C. Recent advances and future directions in practical diet formulation and adoption in tropical palinurid lobster aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture 2022, 14, 1830–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.M.; Williams, K.C.; Irvin, S.; Barclay, M.; S. Tabrett. Development of a pelleted feed for juvenile tropical spiny lobster (Panulirus ornatus): response to dietary protein and lipid. Aquaculture Nutrition 2003, 9, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvin, S.J.; Shanks, S. , Tropical spiny lobster feed development: 2009-2013. In Proceedings of the International Lobster Aquaculture Symposium, Lombok, Indonesia, 22-25 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marchese, G.; Fitzgibbon, Q.P.; Trotter, A.J.; Carter, C.G.; Jones, C.M.; Smith, G.G. The influence of flesh ingredients format and krill meal on growth and feeding behaviour of juvenile tropical spiny lobster Panulirus ornatus. Aquaculture 2019, 499, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, E.V.; Kizhakudan, J.K. , Phillips, B.F. Introduction to lobsters: Biology, Fisheries and Aquaculture. In Lobsters: Biology, Fisheries and Aquaculture; Radhakrishnan, E.V.; Phillips, B.F.; Achamveetil, G., Eds.; Springer, Singapore, 2019, pp. 1-33.

- Vedel, J.P. Cuticular mechanoreception in the antennal flagellum of the rock lobster Palinurus vulgaris. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 1985, 80A, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropielnicka-Kruk, K.; Trotter, A.J.; Fitzgibbon, Q.P.; Carter, C.G.; McRae, J.; Smith, G.G. Functional morphology and ontogeny of mouthparts and mouth aperture of Panulirus ornatus and Sagmariasus verreauxi: Implications towards formulated feeds development. Aquaculture 2025, 595, 741503–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.G.; Hall, M.W.; Salmon, M. Use of microspheres, fresh and microbound diets to ascertain dietary path, component size, and digestive gland functioning in phyllosoma of the spiny lobster Panulirus ornatus. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 2009, 43, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.J. Feed intake and its relation to foregut capacity in juvenile spiny lobster, Jasus edwardsii. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 2009, 43, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Melville-Smith, R.; Hendriks, B. Survival and growth of western rock lobster Panulirus cygnus (George) fed formulated diets with and without fresh mussel supplement. Aquaculture 2007, 273, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffs, A. Status and challenges for advancing lobster aquaculture. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. India 2010, 52, 320–326. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.M. Advances in the culture of lobsters. In New Technologies in Aquaculture; Burnell, G, Allan, G., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, New York, 2009, pp. 822-844.

- Guillaume, J. Formulation of feeds for aquaculture. In Nutrition and Feeding of Fish and Crustaceans; Guillaume, J., Sadisivam, K., Bergot, P., Metailler, R., Eds.; Springer; London, UK, 1999, pp. 309-323.

- Eman, Y.M.; Ümit, A.; Elsayed, M.Y.; Abdel-Wahab, A.A.-W.; Simon, J.D.; Ehab, R.E.-H.; Mohamed, S.H. Performance, physiological and immune responses of nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus fed extruded pellet diets with different binders. Aquaculture reports 2025, 43, 102944. [Google Scholar]

- Houser, R.H.; Akiyama, D.M. Feed formulation principles. In Crustacean Nutrition; D'Abramo, L.R., Counklin, D.E., Akiyama, D.M., Eds.; World Aquaculture Society, USA, 1997, pp. 493-519.

- O'Mahoney, M.; Mouzakitis, G.; Doyle, J.; Burnell, G. A novel konjac glucomannan-xanthan gum binder for aquaculture feeds: the effect of binder configuration on formulated feed stability, feed palatability and growth performance of the japanese abalone, Haliotis discus hannai. Aquaculture Nutrition 2011, 17, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.; Naila, B.; Khwaja, S.; Hussain, S.I.; Ghafar, M. Evaluation of different starch binders on physical quality of fish feed pellets. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2024, 84, e256242–256245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropielnicka-Kruk, K.; Fitzgibbon, Q.P.; Codabaccus, M.B.; Trotter, A.J.; Carter, C.G.; Smith, G.G. Effect of feed texture and dimensions, on feed waste type and feeding efficiency in juvenile Sagmariasus verreauxi. Fishes 2023, 8, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Tsao, R.; Li, Y.; Miao, M. , Food Safety: Food Analysis Technologies/Techniques. In Encyclopedia in Agriculture and Food System; Alven. F.; K.N., Eds.; Elsevier, London, 2014, pp. 273-288.

- Peters, C.; Vilamil, S.I.; Nankervis, L. The periodic feeding frequency of the juvenile tropical rock lobster (Panulirus ornatus) in the examination of chemo-attract diet performance and colour-contrast preference. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14, 2971–10.3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K. Rock lobster enhancement & aquaculture subprogram: The nutrition of juvenile and adult lobsters to optimize survival, growth and condition: Final report of Project 2000/212 to Fisheries Research and Development Corporation; CSIRO Division of Marine Research, Australia, 2003, Report No.: 2000/212.

- Fitzgibbon, Q.P.; Simon, C.J.; Smith, G.G.; Carter, C.G.; Battaglene, S.C. Temperature dependent growth, feeding, nutritional condition and aerobic metabolism of juvenile spiny lobster, Sagmariasus verreauxi. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part A 2017, 207, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.M.; Irvin, S.J.; Mann, D. , Optimising the physical form and dimensions of feed pellets for tropical spiny lobsters. In Proceedings of the Spiny Lobster Aquaculture in the Asia–Pacific Region, Vietnam, 9-10 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Irvin, S.J.; Williams, K.C. , Panulirus ornatus lobster feed development: from trash fish to formulated feeds. In Proceedings of the Spiny Lobster Aquaculture in the Asia–Pacific Region, Vietnam, 9-10 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, P.G.; Meyers, S.P. Chemoattraction and feeding stimulation. In Crustacean Nutrition; D'Abramo, L.R., Counklin, D.E., Akiyama, D.M., Eds.; World Aquaculture Society, USA, 1997, pp. 292-352.

- Nunes, A.J.P.; Sá, M.V.C.; Andriola-Neto, F.F.; Lemos, D. Behavioral response to selected feed attractants and stimulants in Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 2006, 260, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.A.; Gopal, C.; Ramana, J.V.; Nazer, A.R. Effect of different sources of starch and guar gum on aqua stability of shrimp feed pellets. Indian J Fish 2005, 52, 301–305. [Google Scholar]

- Saleela, K.N.; Somanath, B. Effects of binders on stability and palatability of formulated dry compounded diets for spiny lobster Panulirus homarus (Linnaeus, 1758). Indian Journal of Fisheries 2015, 62, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.C.; Smith, D.M.; Irvin, S.J.; Barclay, M.C.; Tabrett, S.J. Water immersion time reduces the preference of juvenile tropical spiny lobster Panulirus ornatus for pelleted dry feeds and fresh mussel. Aquaculture Nutrition 2005, 11, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.J. Identification of digestible carbohydrate sources for inclusion in formulated diets for juvenile spiny lobsters, Jasus edwardsii. Aquaculture 2009, 290, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, J.; Röhnisch, H.E.; Heupl, S.; Marinea, M.; Johansson, M.; Alminger, M.; Zamaratskaia, G.; Högberg, A.; Langton, M. The effect of transglutaminase and ultrasound pre-treatment on the structure and digestibility of pea protein emulsion gels. Food Hydrocolloids 2025, 169, 111620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).