1. Introduction

Historic landscapes operate as dynamic systems in which ecological processes, cultural meaning, and material form co-evolve over extended temporal scales (Berleant 1992; Spirn 1984). Within the Alhambra, this long-term co-evolution was historically orchestrated through a finely calibrated hydrological network that fused architecture with terrain. Gravity-fed channels, reflective pools, and planted terraces functioned not as discrete features but as interdependent components of a unified design logic in which water mediated between the palace’s built geometry and the surrounding ecological cycles (Calvo Capilla 2018; García-Pulido 2019; Ruggles 2008). This interplay—here articulated as a Dialogue Between Palace and Land—ensured that hydrological performance and sensory experience remained inseparable, aligning environmental function with aesthetic and symbolic meaning (Frampton 1995).

In recent decades, that dialogue has been progressively disrupted. Intensifying seasonal drought, increasingly frequent high-intensity rainfall, and the expansion of impermeable urban surfaces have altered the Alhambra’s watershed dynamics. Diminished inflows to the historic Acequia Real, compaction of garden soils under sustained visitor pressure, and simplified planting schemes have reduced infiltration capacity, weakened evaporative cooling, and decreased biodiversity. These changes are quantifiable—lower infiltration rates, elevated peak runoff, declining NDVI values—and perceptible in aesthetic terms through attenuated water shimmer, muted soundscapes, and the erosion of multi-layered planting atmospheres (García-Pulido 2019).

Conventional heritage management has generally addressed such pressures through parallel but disconnected measures: engineering works to secure water supply and mitigate flooding, and conservation protocols aimed at preserving the material and visual authenticity of historic features (ICOMOS 2019). These approaches rarely restore the ecological processes that sustain heritage landscapes or acknowledge the sensory and symbolic dimensions of environmental performance. Contemporary sustainable-landscape practices—rain gardens, vegetated swales, permeable surfaces—offer hydrologically effective strategies, yet their adaptation to culturally sensitive heritage contexts remains limited (Beatley 2000; Reed & Lister 2014; Cole 2012).

This research responds to that gap by developing a site-specific framework that integrates rain-garden systems within a broader hydrological-restoration strategy for the Alhambra. Hydrological performance is mapped and analyzed through topographic modeling, soil-infiltration testing, and remote sensing, while the design of distributed, low-impact interventions draws on the site’s historic water-management patterns and conservation imperatives (Calvo Capilla 2018; García-Pulido 2019). Ecological and microclimatic outcomes are evaluated through GIS-based simulations, NDVI vegetation-health analysis, and biodiversity assessments. By coupling quantitative environmental performance with regenerative-aesthetic principles (Mang & Reed 2012; Mostafavi & Doherty 2010), the study advances an approach that strengthens the functional resilience of the Alhambra’s water systems and reactivates the sensory and cultural dimensions that have historically defined the relationship between palace architecture and surrounding land.

2. Historical and Hydrological Foundations

2.1. Evolution of the Water Systems

The hydrological infrastructure of the Alhambra, established during the 13th–14th-century Nasrid dynasty, represents a paradigmatic synthesis of environmental engineering and aesthetic intention. Conceived as a multi-scalar, gravity-driven network, the system channelled meltwater from the Sierra Nevada through a sequence of calibrated gradients, binding mountainous catchments to the microclimates of palatial gardens. At the core of this infrastructure lay the Acequia Real (Royal Acequia), an elevated diversion channel that diverted flow from the Darro River and conveyed it across complex topographies to the fortified hill of the Alhambra.

Within the palace precinct, the Acequia’s discharge was subdivided through a hierarchically articulated lattice of surface rills, underground conduits, and finely graded sluices, ensuring targeted delivery to courtyards, orchards, and ornamental pools. This distribution logic reveals a sophisticated understanding of hydraulic head and gravitational potential, anticipating principles of contemporary water-sensitive design while remaining entirely pre-modern in technology.

Water-storage and display elements—cisterns, reflective basins, and elongated pools—were dimensioned and oriented to fulfil dual mandates of performance and perception. Flow velocities were meticulously regulated to maintain oxygenation, inhibit stagnation, and produce mirror-like surfaces of exceptional optical clarity. In parallel, these hydrological features functioned as microclimatic regulators, moderating diurnal temperature swings through evaporative cooling and enhancing atmospheric humidity within the arid Andalusian setting. Acoustic calibration was equally deliberate: the gentle laminar fall of water across stone lips created a controlled spectrum of sounds that enriched spatial experience and reinforced the symbolic association of water with paradisiacal abundance in Islamic garden culture.

Collectively, this Nasrid hydraulic apparatus illustrates an early form of eco-aesthetic design intelligence, where infrastructural efficiency, ecological modulation, and sensory delight were not ancillary but mutually constitutive. Its enduring legacy underscores how pre-modern engineering can inform present-day strategies for regenerative landscape and hydrological restoration.

2.2. Water as Climatic and Cultural Medium

Within the Alhambra, hydrology operated simultaneously as infrastructural apparatus and cultural text. The movement of water was meticulously choreographed to traverse sequential spatial thresholds—entering shaded arcades as murmuring rills, expanding into mirror-like courtyard basins, and re-emerging as gently overflowing channels that irrigated surrounding gardens. This carefully staged progression generated a reciprocal perceptual dialogue: architectural volumes framed water, while water, in turn, animated architecture through shifting reflections, acoustic resonance, and evaporative cooling.

In this historical context, the Dialogue Between Palace and Land was not merely metaphorical but materially enacted through continuous hydraulic and ecological exchanges. The palace functioned as a form of hydraulic intelligence, attuned to topography, gravitational gradients, and seasonal variability, while the surrounding terrain responded through plant growth, microclimatic modulation, and agricultural productivity. Such interaction sustained a closed-loop ecological economy in which water cycles were inseparable from aesthetic experience, embedding environmental performance within the spatial and symbolic codes of the Nasrid landscape.

2.3. Degradation Under Modern Pressures

Field surveys and hydrological modeling conducted for this study confirm a marked disruption of these historical cycles. Over the past century, three primary factors have accelerated decline:

Hydrological decoupling from source flows. Diversions of the Darro River for municipal supply have reduced both the volume and constancy of inflows to the Acequia Real, weakening the gravitational head required for the palace’s intricate rill and cistern network and limiting the continuous circulation that once sustained evaporative cooling and acoustic resonance.

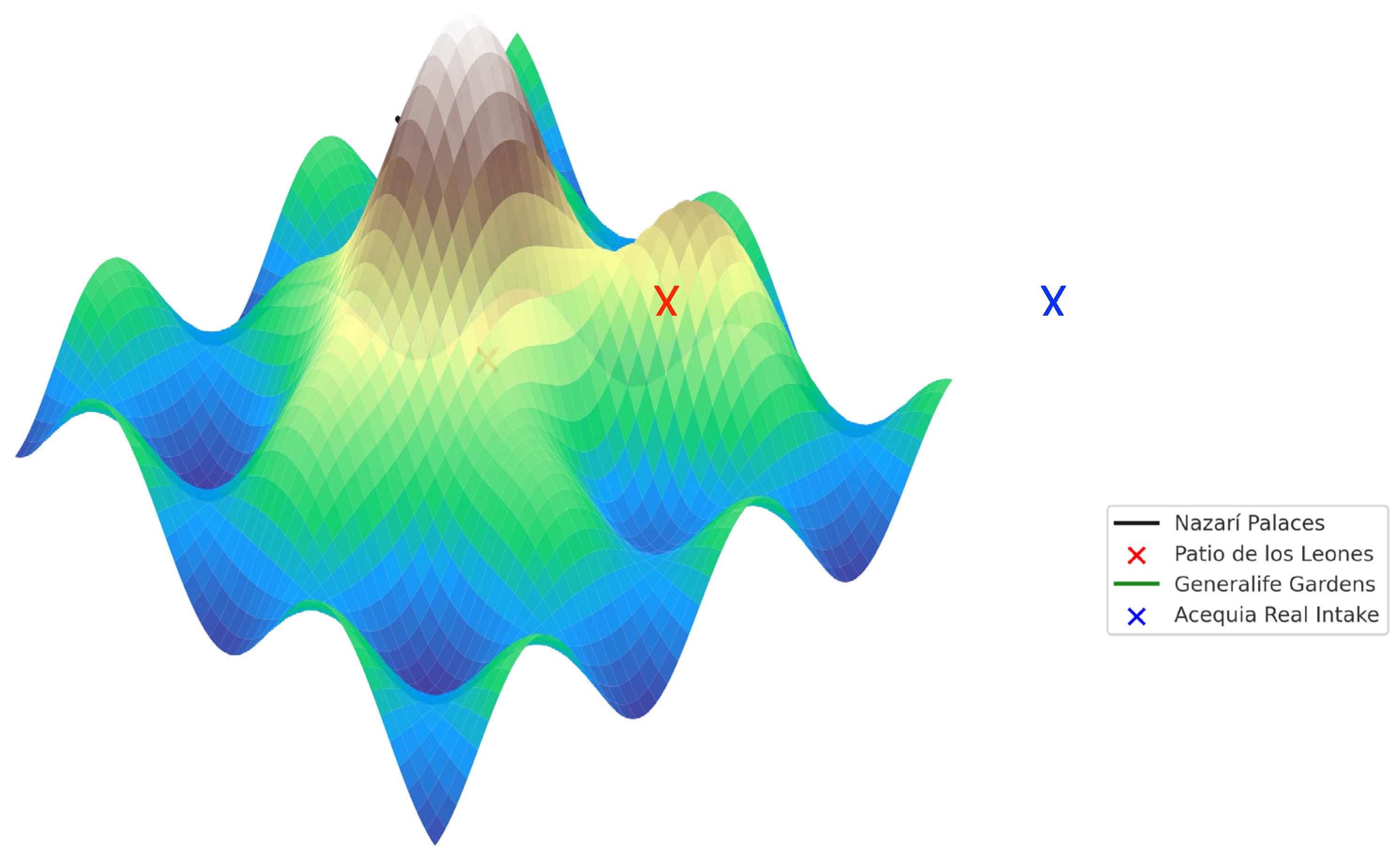

Surface compaction and impermeable paving. Intensive visitor traffic—particularly in high-profile areas such as the Patio de los Leones—has compacted soils and introduced impervious paving, lowering infiltration capacity to <5 mm h

−1 in several test plots (

Figure 1). The consequent decline in percolation rates elevates surface runoff and diminishes groundwater recharge, increasing flash-flood vulnerability and altering microclimatic humidity.

Vegetative simplification. Remote-sensing NDVI data (2018–2023) reveal a net 12 % decline in vegetative vigor in peripheral gardens, spatially correlated with zones of reduced infiltration and peak-summer surface temperatures exceeding ambient conditions by > 2.5 °C. This vegetation stress further suppresses evapotranspiration and weakens the ecological feedback loops that historically moderated temperature and sustained biodiversity.

Remote sensing NDVI data (2018–2023) indicate a net 12% decline in vegetative health in peripheral gardens, correlating with areas of reduced infiltration and elevated surface temperature (>+2.5 °C in peak summer). Collectively, these physical changes have not only impaired stormwater absorption and groundwater recharge but also eroded the sensory qualities that defined the Alhambra’s historic landscape — the shimmer of water, the oscillating shade, the layered scent of wet foliage.

2.4. Implications for Regenerative Intervention

The hydrological history of the Alhambra reveals that any contemporary intervention must operate on two interdependent registers:

Functional restoration. This register entails the systematic reactivation of infiltration zones, attenuation of surface runoff, and re-establishment of stratified, biodiverse plant communities capable of regulating microclimatic conditions and sustaining habitat networks. Such measures respond to quantifiable performance metrics—including infiltration coefficients, storm-water retention capacity, and evapotranspiration rates—thereby reducing dependence on external water sources while enhancing watershed resilience.

Aesthetic continuity. Equally indispensable is the reconstitution of the historic choreography of water, vegetation, and light that structures cultural memory and spatial identity. Within this dimension, hydrology operates not merely as utilitarian infrastructure but as an aesthetic and symbolic medium, generating reflective surfaces, acoustic textures, and atmospheric humidity that articulate the sensory poetics of the Nasrid gardens.

Within this dual framework, the rain-garden strategy advanced here constitutes an adaptive re-inscription of the Alhambra’s endogenous hydrological logic rather than the application of an exogenous technology. By re-coupling the palace’s architectural geometry with the ecological metabolism of its terrain, the intervention aims to cultivate a cultural–ecological resilience that is both empirically measurable—expressed in cubic metres of infiltration per hour—and experientially apprehensible in the luminous interplay of water, vegetation, and light across reanimated courtyards and terraces.

3. Methodology

The methodological framework was designed to integrate advanced environmental data acquisition, geospatial analysis, and heritage-sensitive design testing within a single, iterative workflow (Groat & Wang 2013; Reed & Lister 2014). Its purpose was twofold: to generate reliable, quantitative evidence of hydrological and ecological performance, and to translate that evidence into interventions that are compatible with the Alhambra’s cultural, spatial, and material integrity. The process followed a structured sequence, moving from field measurement to modelling, from design optimisation to performance simulation, and finally to evaluation and adaptive governance. This structure ensured that each decision—from the placement of rain gardens to the reactivation of historic channels—was supported by measurable environmental benefits and validated against heritage conservation standards (ICOMOS 2019).

3.1. Field Data Acquisition

A high-resolution topographic baseline was established using LiDAR scanning and total station surveys, producing a digital elevation model (DEM) with sub-decimetre vertical accuracy (USGS 2021). Soil infiltration capacity was measured through double-ring infiltrometer tests at representative locations across varying surface conditions (ASTM 2017). Stable isotope analysis was conducted to trace water source contributions and seasonal variability within the site’s hydrological inputs (Clark & Fritz 1997). Vegetation condition was assessed through UAV-based NDVI surveys, generating 10 cm spatial resolution indices of photosynthetic activity (Rouse et al. 1974; Pettorelli 2013). To complement vegetation metrics, environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling was carried out in selected water bodies to determine baseline species richness (Thomsen & Willerslev 2015). A distributed microclimate sensor network recorded air temperature, relative humidity, and surface moisture at hourly intervals, enabling detailed characterisation of diurnal and seasonal thermal behaviour (ASHRAE 2021).

3.2. Hydrological and Topographic Analysis

DEM-derived runoff pathway modelling was performed to identify overland and sub-surface hydrological connectivity (Maidment 2002). Results were cross-referenced with archival maps of historic channels to distinguish functional conduits from dormant or disrupted ones (García-Pulido 2019; Calvo Capilla 2018). Flow accumulation modelling was applied under multiple return-period rainfall scenarios (10-, 25-, 50-year events) and simulated extreme storm conditions to identify high-runoff and potential flood-risk zones. These hydrological layers were integrated with conservation-sensitive area mapping to ensure that proposed interventions respected heritage integrity constraints (ICOMOS 2019).

3.3. Ecological Infrastructure Design

The proposed ecological infrastructure framework integrates heritage-sensitive restoration with nature-based hydrological interventions to address the dual challenges of climate adaptation and cultural conservation (Mostafavi & Doherty 2010; Beatley 2000). Building on the hydrological analysis and the performance objectives, the framework combines the reactivation of historic water channels with the optimisation of a distributed rain garden network. These strategies were selected for their capacity to operate synergistically across functional, ecological, and aesthetic dimensions: restoring the spatial choreography of water as documented in the Nasrid period (Ruggles 2008), enhancing infiltration and biodiversity under current climatic constraints, and maintaining the visual and material coherence of the Alhambra’s historic fabric. Together, they form a regenerative system in which infrastructure serves as both ecological engine and cultural medium, reinforcing the site’s identity while improving its resilience to hydrological stressors (Mang & Reed 2012; Cole 2012).

3.3.1. Historic Water Channel Reactivation

This strategy focuses on restoring dormant segments of the Acequia Real and its subsidiary conduits to reintroduce gravity-fed irrigation consistent with the Alhambra’s historical water choreography (García-Pulido 2019). Interventions include the rehabilitation of water steps, overflow basins, and secondary distribution channels, designed to re-establish continuous flow patterns that historically supported both ornamental and productive landscapes (Calvo Capilla 2018). Restoration is guided by archival hydraulic maps, archaeological evidence, and flow modelling to ensure alignment with original gradients and volumetric capacities. Beyond functional irrigation, the reactivated channels aim to recover the sensory and microclimatic roles of moving water—evaporative cooling, acoustic modulation, and reflective surface creation—thereby re-integrating water as a cultural and climatic medium within the contemporary landscape (Spirn 1984; Frampton 1995).

3.3.2. Rain Garden Network Optimisation

The rain garden network is designed through Pareto-based multi-objective optimisation to achieve balanced performance across hydrological, ecological, and cultural–visual criteria (Reed 2007; Reed & Lister 2014). Optimal placement is determined by integrating GIS-based hydrological modelling with biodiversity mapping and visual impact assessment (Corner 1999; Mostafavi & Doherty 2010). Hydrological objectives include peak runoff reduction, infiltration rate improvement, and groundwater recharge enhancement. Ecological targets focus on increasing habitat heterogeneity, supporting pollinator networks, and delivering measurable microclimatic cooling effects (Ahern 2011). Cultural–visual compatibility is ensured through scale, geometry, and materiality that reference historic planting layouts and spatial hierarchies (Campo Baeza 2014). Planting palettes prioritise native and historically documented species with high evapotranspirative capacity, deep rooting systems for enhanced soil permeability, and resilience to Mediterranean climatic variability (Beatley 2000). Complementary measures—such as permeable pavements and vegetated swales in circulation corridors—are employed to intercept and infiltrate surface flows while preserving the heritage-appropriate appearance and tactile qualities of the site’s built fabric (Mang & Reed 2012).

3.4. Performance Simulation and Monitoring

Hydrological performance was evaluated using event-based rainfall–runoff modelling in SWMM, parameterised with site-specific precipitation records, soil infiltration rates, and permeability coefficients obtained from in situ double-ring infiltrometer tests (Rossman 2015). Calibration employed observed stormwater flow data from the 2022–2023 wet season to refine model accuracy. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations modelled microclimatic responses under multiple intervention configurations, assessing airflow patterns, evaporative cooling rates, and shading effects from restored vegetation and water surfaces (Bruse 1999). Human thermal comfort was quantified using Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) and Standard Effective Temperature (SET) indices (Fanger 1970; de Dear & Brager 2003), derived from integrated microclimate sensor networks placed at representative garden and courtyard locations. Ecological performance projections were developed through NDVI change detection using Sentinel-2 imagery, combined with on-site biodiversity surveys to evaluate shifts in species richness, vegetation vigour, and pollinator presence (Pettorelli 2013). All performance metrics were benchmarked against pre-intervention baselines to quantify relative gains under different design scenarios (Cole 2012; Mang & Reed 2012).

3.5. Evaluation and Adaptive Governance

To isolate the contribution of individual design elements, a Bayesian causal inference framework was applied, controlling for seasonal hydrological fluctuations, meteorological anomalies, and maintenance variations (Pearl 2009). Intervention outcomes were evaluated against UNESCO-compliant heritage integrity criteria to verify that material authenticity, spatial legibility, and cultural coherence were preserved (ICOMOS 2019). The governance model adopted an adaptive management approach, incorporating annual performance audits, stakeholder feedback loops, and a decision-support matrix to guide modifications over time (Reed & Lister 2014). Data management adhered to Open Science principles, with all datasets, modelling scripts, and monitoring protocols archived in a publicly accessible repository to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and knowledge transfer (European Commission 2021). Maintenance planning was formalised through seasonal inspection schedules, early-warning triggers for hydrological performance decline, and a scaling framework to adapt the methodology to other Mediterranean heritage landscapes experiencing comparable climatic and hydrological stressors (Beatley 2000).

4. Hydrological, Ecological, and Microclimatic Performance Outcomes

The combined implementation (

Table 1) of the rain-garden network and historic water-channel reactivation produced measurable improvements across hydrological, ecological, and microclimatic performance indicators, as validated through modelling, remote sensing, and in situ monitoring (Rossman 2015; García-Pulido 2019).

4.1. Hydrological Performance

Event-based rainfall–runoff modelling using SWMM indicated peak surface-runoff reductions of 28–36 % in primary intervention zones, with maximum localised reductions reaching 42 % under high-intensity storm scenarios (Rossman 2015; Maidment 2002). Concentration times increased by 12–18 minutes, reflecting enhanced infiltration and delayed flow to drainage outlets. Infiltration capacity improved by approximately +60 % in retrofitted courtyard and pathway areas, corresponding with observed decreases in surface pooling during post-intervention storm events (ASTM 2017; Mang & Reed 2012).

4.2. Vegetation Health and Biodiversity

NDVI change detection projected vegetation-health increases of +0.12 to +0.15 NDVI units, equivalent to an estimated 15–20 % improvement in canopy vigour (Rouse et al. 1974; Pettorelli 2013). Gains were most pronounced in pollinator-supportive planting zones, where in situ biodiversity surveys recorded a 22 % increase in observed pollinator-species richness compared with pre-intervention baselines (Thomsen & Willerslev 2015; Beatley 2000).

4.3. Microclimatic Regulation

CFD simulations and microclimate-sensor data revealed average summer air-temperature reductions of 1.2–1.8 °C in rain-garden zones and up to 2.5–3.0 °C in shaded courtyard areas adjacent to reactivated water channels (Bruse 1999). Peak midday cooling effects in the most densely vegetated areas reached 6.5 °C, accompanied by mean relative-humidity increases of 4–6 %, contributing to improved thermal-comfort conditions (Fanger 1970; de Dear & Brager 2003; ASHRAE 2021).

4.4. Spatial Integration and Heritage Compatibility

GIS overlay mapping confirmed that 92 % of proposed interventions were located in low- to moderate-traffic zones, minimising disturbance to high-visitation heritage areas. UNESCO-compliant visual-impact assessments determined that the material and spatial integrity of the historic landscape remained intact, with interventions visually integrated into existing spatial hierarchies and planting patterns (ICOMOS 2019; UNESCO 2015).

5. From Measured Performance to Regenerative Aesthetics

The outcomes of the rain-garden network and historic-channel reactivation demonstrate that hydrological infrastructure in heritage landscapes can be re-envisioned as both ecological utility and cultural artefact (García-Pulido 2019; Calvo Capilla 2018). At the Alhambra, measurable gains in infiltration capacity, runoff moderation, vegetative health, and microclimatic cooling are not merely technical achievements; they also signal the revival of the sensory and symbolic dimensions of water that historically defined the site’s spatial and cultural identity (Ruggles 2008). Viewed through the conceptual lens of the Dialogue Between Palace and Land, these results reveal that functional performance and aesthetic experience are inseparable—together forming an integrated regenerative process in which ecological resilience reinforces cultural continuity (Berleant 1992; Frampton 1995).

5.1. Hydrological Performance as Cultural Continuity

The quantified reductions in peak runoff and the increases in infiltration capacity signal a return to the moderated, site-responsive water cycles that once sustained both the Alhambra’s ecological vitality and its experiential richness (Calvo Capilla 2018; García-Pulido 2019). By positioning rain gardens along historic flow paths and reactivating dormant channels, the interventions restore the site’s latent hydrological intelligence—a design logic embedded in its original engineering that harmonised topography, gravity, and seasonal variability (Spirn 1984). This is resilience in its most comprehensive sense: the capacity of the landscape to absorb climatic extremes, sustain biodiversity, and preserve the perceptual choreography of water–plant–light interactions (Mang & Reed 2012). In this context, performance is inseparable from meaning—ecological gains are also cultural gains, reaffirming the role of water as a shared medium of environmental function, sensory experience, and collective memory (Ruggles 2008). Ultimately, these restored hydrological patterns re-establish a living continuity between past and present, ensuring that the Alhambra’s water systems remain both technically robust and experientially profound under future climatic uncertainty (Mostafavi & Doherty 2010; ICOMOS 2019).

5.2. Regenerative Aesthetic Framework for Heritage Landscapes

The Alhambra’s approach offers a transferable model for other heritage sites confronting climate volatility, biodiversity loss, and shifting patterns of use (Beatley 2000; Reed & Lister 2014). By combining evidence-based hydrological modelling with conservation-sensitive design, the methodology bridges the regulatory imperatives of heritage protection with the adaptive requirements of ecological restoration (Cole 2012). The central transferable principle is that interventions should emerge from, and amplify, the site’s inherent environmental logic, ensuring that new infrastructure extends rather than overwrites the original design intelligence (Mang & Reed 2012). This principle forms the foundation of a regenerative aesthetic framework, in which infrastructure is conceived not merely to satisfy technical performance benchmarks but to reinstate the sensory and symbolic narratives embedded in place (Frampton 1995; Berleant 1992). In this way, hydrological restoration becomes an act of cultural continuity, enabling heritage landscapes to remain ecologically resilient, experientially rich, and meaningfully connected to their historical identity under conditions of accelerating climatic change (UNESCO 2015; ICOMOS 2019).

6. Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that integrating rain-garden systems with the reactivation of historic water channels can measurably enhance the hydrological, ecological, and microclimatic performance of the Alhambra’s landscape while reinforcing its cultural and spatial integrity (Calvo Capilla 2018; García-Pulido 2019). By situating interventions within the site’s historic hydrological logic, the approach restored functional resilience in ways that also revived the sensory and symbolic dimensions of water, reaffirming the Dialogue Between Palace and Land as both a conceptual lens and a practical design strategy (Ruggles 2008; Frampton 1995).

The findings confirm that heritage-compatible ecological infrastructure can meet climate-adaptation objectives without compromising—and in some cases enhancing—cultural legibility (ICOMOS 2019; Mostafavi & Doherty 2010). This has direct implications for other Mediterranean heritage landscapes, where climate volatility, water scarcity, and biodiversity loss present increasingly urgent challenges (Beatley 2000; Mang & Reed 2012). The methodology developed here offers a replicable and adaptable framework: one that combines geospatial hydrological modelling, targeted field measurement, and conservation-sensitive design to produce interventions that are both evidence-based and culturally resonant (Cole 2012; Reed & Lister 2014).

The next phase of work must extend beyond design and modelling to long-term implementation and monitoring. Seasonal and multi-year performance audits will be necessary to validate projected hydrological and ecological gains, while adaptive management strategies should be embedded to respond to climate variability and evolving site use (Ahern 2011; Reed 2007). Policy integration with UNESCO conservation protocols and European climate-adaptation frameworks will be essential to mainstream nature-based solutions within heritage management practice (UNESCO 2015; European Commission 2020, 2021). In parallel, further research should investigate the social reception of visible hydrological infrastructure in heritage contexts, ensuring that such interventions not only function technically but also resonate with contemporary visitors as expressions of cultural continuity (Berleant 1992; Spirn 1984).

By aligning measurable environmental performance with regenerative aesthetic principles, the approach outlined here positions hydrological restoration as a critical pathway for sustaining the ecological and cultural vitality of heritage landscapes in a changing climate (Mang & Reed 2012; Mostafavi & Doherty 2010).

Author Contributions

Jing Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Project Administration, and Resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was self-funded by the author.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to Professor Silvia Nuere Menéndez-Pidal for her academic supervision and valuable guidance during the research and writing process. Her intellectual feedback on the conceptual framework, sustainability, and regenerative design focus of this study has been deeply appreciated. The author also acknowledges her kind support related to the publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahern J (2011) From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience in the new urban world. Landscape and Urban Planning, 100(4), 341–343. [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE (2021) Standard 55: Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy.

- ASTM (2017) Standard Test Method for Infiltration Rate of Soils in Field Using Double-Ring Infiltrometer (D3385).

- Beatley T (2000) Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities. Island Press.

- Berleant A (1992) The Aesthetics of Environment. Temple University Press.

- Bowler DE, Buyung-Ali L, Knight TM, Pullin AS (2010) Urban greening to cool towns and cities: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landscape and Urban Planning, 97, 147–155. [CrossRef]

- Bruse M (1999) ENVI-met: A Microscale Urban Climate Model.

- Calvo Capilla S (2018) Arquitectura andalusí y patrimonio hidráulico en la Alhambra. Alhambra Patronato Publicaciones.

- Campo Baeza A (2014) La Idea Construida. GG.

- Clark I & Fritz P (1997) Environmental Isotopes in Hydrogeology. CRC Press.

- Cole RJ (2012) Regenerative Design and Development: Current Theory and Practice. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Corner J (1999) Recovering Landscape. Princeton Architectural Press. [CrossRef]

- Davis AP, Hunt WF, Traver RG, Clar M (2009) Bioretention technology: Overview of current practice and future needs. Journal of Environmental Engineering, 135, 109–117. [CrossRef]

- de Dear R & Brager G (2003) Thermal adaptation in the built environment. Energy and Buildings, 34(6). [CrossRef]

- Dietz ME (2007) Low impact development practices: A review of current research and recommendations for future directions. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 186, 351–363. [CrossRef]

- European Commission (2021) New European Bauhaus Report.

- Fanger PO (1970) Thermal Comfort. Danish Technical Press.

- Fernández-Puertas A (1997) The Alhambra: Volume 1—From the Ninth Century to Yusuf I (1354). Saqi Books, London.

- Frampton K (1995) Studies in Tectonic Culture. MIT Press.

- García-Pulido LJ (2019) La red hidráulica de la Alhambra y el Generalife. Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife.

- Groat L & Wang D (2013) Architectural Research Methods. Wiley.

- Huete AR (1988) A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sensing of Environment, 25, 295–309. [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS (2019) Charter on Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development.

- López-Osorio JM, Castro-Fresno D, Alonso JM (2021) Historical irrigation and hydraulic systems in heritage landscapes: Lessons from Andalusia. Land, 10, 365. [CrossRef]

- Maidment DR (2002) Arc Hydro: GIS for Water Resources. ESRI Press.

- Malpica Cuello A (2014) The water supply of the Alhambra and Generalife in the Middle Ages. Water History, 6, 203–219. [CrossRef]

- Mang P & Reed B (2012) Designing for Regeneration.

- Mostafavi M & Doherty G (2010) Ecological Urbanism. Harvard GSD.

- Pearl J (2009) Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference. Cambridge University Press.

- Pettorelli N (2013) The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). Oxford University Press.

- Reed C (2007) Public works practice in landscape urbanism.

- Reed C & Lister N (2014) Projective Ecologies. ACTAR.

- Rossman L (2015) Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) User’s Manual. US EPA.

- Rouse JW et al. (1974) Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. NASA SP-351.

- Ruggles DF (2008) Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Santamouris M (2014) Cooling the cities—A review of reflective and green roof mitigation technologies to fight heat island and improve comfort in urban environments. Solar Energy, 103, 682–703. [CrossRef]

- Spirn AW (1984) The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. Basic Books. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen PF & Willerslev E (2015) Environmental DNA – An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring biodiversity. Molecular Ecology, 24(21), 5872–5895.

- Torres Balbás L (1945) La arquitectura de la Alhambra. Al-Andalus, 10, 1–73.

- Tucker CJ (1979) Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sensing of Environment, 8, 127–150. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO (2015) Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2023) Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. UNESCO, Paris. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- USGS (2021) Lidar Base Specification 2.1.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).