1. Introduction

Historical rural landscapes, defined as terrestrial and wetland areas shaped by human-nature interactions, embody a holistic structure encompassing both natural and cultural values. These landscapes, shaped by ecological conditions and social traditions, rely on cyclic production systems. However, they face significant conservation challenges due to the effects of contemporary climate change. Rising temperatures, drought, desertification, extreme weather events, air pollution, rising sea levels, and strong winds can deteriorate building materials. Furthermore, changes in precipitation patterns and groundwater levels disrupt biodiversity and local plant systems, leading to agricultural inefficiencies and reduced crop yields. These challenges have begun to severely impact the livelihoods of historical rural communities, particularly those dependent on agriculture, animal husbandry, and forestry, making them increasingly vulnerable in social, economic, and cultural contexts.

Climate change is defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as "a change in the state of the climate that can be identified by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties, and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer" [

1]. Beyond the phenomenon of global warming, climate change involves shifts in regional climatic characteristics such as humidity, rainfall, and wind patterns, along with an observed increase in the frequency of extreme weather events, leading to significant biophysical, social, and economic consequences [

2]. Climate change not only alters the frequency and intensity of hazards but also exacerbates vulnerability factors such as urbanization, poverty, and environmental degradation, further compounding risks to lives, property, and the economy [

3].

To develop adaptation strategies for historical rural landscapes in response to global climate change risks, it is crucial to identify existing threats and formulate targeted adaptation measures [

4]. A review of national and international recommendations highlights that historical rural landscapes are increasingly being evaluated within the framework of sustainable conservation approaches. The 2017 document "Principles for Rural Landscape Heritage," jointly published by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA), provides a broad scope for assessing landscape components and their associated threats [

5]. These recommendations emphasize the necessity of preserving landscape components holistically to ensure the sustainability of agricultural, forestry, and natural resource diversity, which are vital for global adaptation and resilience [

4]. In the 2020 ICOMOS General Assembly, a Climate and Ecology Emergency was declared, urging collective action to safeguard cultural and natural heritage from climate change impacts [

6]. Additionally, the 2021 ICOMOS policy statement "Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development Goals" outlines strategies to leverage cultural heritage for climate resilience, advocating for landscape-based and community-driven solutions, active indigenous participation, and the promotion of resilient heritage-based techniques. The document underscores the importance of integrating climate vulnerability assessments into heritage management policies, plans, and projects while implementing adaptation and mitigation measures.

This study proposes a sustainable conservation approach for historical rural landscapes in response to climate change by developing protection strategies based on permaculture principles. Permaculture, which adopts an ecological perspective, is grounded in three ethical foundations—care for people, care for nature, and equitable resource distribution—alongside twelve design principles that guide site-specific interventions. Permaculture encompasses both tangible and intangible components, including "site and energy components" as physical elements and "social permaculture" as a framework for cultural and human activities. Similar design structures have historically evolved within historical rural landscapes, integrating cultural, natural, and agricultural elements. By drawing parallels between these elements and permaculture principles, this study establishes a unified framework for climate-adaptive conservation. The use of permaculture as a sustainable tool enables the adaptation of traditional knowledge and practices to mitigate the effects of climate change on historical rural landscapes.

Following the establishment of the theoretical framework, a case study was conducted to illustrate the proposed approach. The Barbaros Rural Settlement in the Urla District of Izmir Province was selected due to its environmental, social, and physical characteristics, its potential to transmit local knowledge and skills, and its vulnerability to climate change risks. Initial documentation efforts resulted in the creation of a landscape values map for Barbaros Rural Settlement. This map formed the basis for analyzing climate change impacts on the cultural, natural, and agricultural environments, identifying key vulnerabilities. Subsequently, sectoral and zoning analyses were conducted, dividing the study area into distinct regions, followed by the development of permaculture-based conservation proposals tailored to each zone.

2. Historical Rural Landscapes and Components

Landscape can be understood as the totality of natural and cultural elements within a specific area. From a conservation perspective, the integration of cultural value with its surrounding environment gave rise to the concept of cultural landscapes. During the 19th and 20th centuries, landscape evolved into not only a critical field of study but also a domain where approaches to both landscape protection and nature conservation became intertwined [

7]. UNESCO significantly contributed to the protection and management of these areas by incorporating the definition of cultural landscapes into the World Heritage Convention in 1992. UNESCO defines cultural landscapes as areas shaped through the joint work of humans and nature, reflecting the evolution of human communities and settlements over time, influenced by the physical constraints and opportunities offered by natural environmental conditions, as well as internal and external social, economic, and cultural factors [

8].

In the ICOMOS Architectural Heritage Protection Declaration, cultural landscape is defined as areas transformed by society and human settlements throughout history, shaped by economic, social, and cultural factors, and interacting with their natural environment. It also encompasses geographical regions that contain both cultural and natural resources created collaboratively by humans and nature, including wildlife and domesticated animals, and areas linked to historical events or activities. These areas are remembered for their cultural and aesthetic values [

9].

Historical rural landscapes, which carry the traditional transmission of regional architecture throughout history, have a holistic design structure with the agricultural use of surface and underground remains that contribute to this texture, natural and cultural values and architectural formations that form the local architectural identity. The definition of rural areas as terrestrial and wetlands formed by human-nature interaction reveals the concepts of “rural landscape” and “rural landscape architecture”. Rural landscapes, as a living organism, are based on production and cyclicity, fed by local resources and accumulation. In this context, rural landscape heritage is defined as the tangible and intangible heritage of the relevant historical rural area and includes the physical, cultural and environmental ties of the local. Rural landscape heritage is defined as the tangible and intangible heritage of rural areas. Tangible components that come to the forefront with physical connections are also shaped by intangible heritage depending on cultural and environmental effects. It is possible to divide historical rural landscapes, which are a reflection of the interaction and life partnership between humans and nature, as “cultural environment”, “agricultural environment” and “natural environment”.

Rural landscape heritage encompasses tangible and intangible components. The tangible components, which emerge through physical connections, are deeply shaped by the intangible heritage influenced by cultural and environmental factors. Historical rural landscapes, which reflect the interactive relationship and life partnership between humans and nature, can be divided into three primary categories: "cultural environment," "agricultural environment," and "natural environment."

Cultural environments, which evolve based on human needs and where various types of structures converge, include historical buildings constructed with traditional methods. These areas, ranging from small farmsteads to larger village settlements, are directly influenced by agricultural activities, economic resources, land use, topography, and climate. Over time, these areas have developed and differentiated according to the geographic characteristics of the region. Rural architectural examples, forming the physical fabric of these landscapes, are closely related to local needs and functionality, reflecting traditional building practices. The most significant elements of historical rural landscapes are traditional settlements and structures, which are constructed using local materials and techniques. These structures are also a reflection of the culture, identity, and originality of the region and its society.

Agricultural and animal husbandry activities within historical rural landscapes serve as significant sources of income for the region. According to settlement theory, the selection of agricultural areas is determined by the topographic characteristics and the availability of water resources. Soil quality and productivity are also crucial factors in this selection process. Agricultural areas, characterized by adequate water retention capacity, relatively flat and not excessively steep terrain, should be easily accessible from settlement areas.

The vegetation that develops based on local geographical features and climate is one of the most important determinants of historical rural landscapes. Natural vegetation, shaped by rainfall and temperature, grows according to the climatic characteristics of its location. This vegetation is inherently local and forms the primary representation of the region’s ecological identity. In addition to natural forests and areas, land that has been transformed for agricultural purposes is essential for sustaining local production methods. These agricultural landscapes are the direct result of human efforts to generate productivity and serve the production needs of local communities.

The choice of crops grown in these agricultural areas, which provide food for the population, is highly influenced by the specific climate characteristics of the region. Managing these areas in a way that ensures biological and ecological balance with nature is crucial for maintaining sustainability. Local fruit and vegetable cultivation, for instance, is vital for economic continuity, as it generates income through both consumption and local sales within the historical rural landscape. In contrast to agricultural environments, forest areas, unique fauna and flora species, and water resources hold a significant place in sustaining vital activities within historical rural landscapes. These components play an essential role in the overall functioning of the landscape, contributing to both ecological and cultural sustainability.

Historical rural landscapes also consist of intangible components, such as culture, cultural practices, activities, and representations, in addition to their tangible components. Local life practices, especially traditional knowledge and experience, reflect the cultural significance of the landscape. Intangible cultural elements such as religious practices, water culture (including fountains and washing rituals), coffeehouse culture, and food traditions are integral to the identity of rural settlements, enriching the cultural landscape and deepening the connection between people and their environment.

3. Permaculture Design and Components

The concept of permaculture and its philosophical foundations first emerged in Australia during the 1970s, with the pioneering work of Bill Mollison and David Holmgren. Permaculture is an earth science that combines traditional agricultural methods, scientific knowledge, technology, and practical skills to develop holistic solutions to ecosystem challenges. As a design methodology, it focuses on creating human settlements that align with ecological principles, integrating sustainable systems to address environmental and social needs.

David Holmgren, a co-founder of the permaculture movement, defines it as "consciously designed landscapes, which mimic the patterns and relationships found in nature, while yielding an abundance of food, fiber, and energy to meet local needs" [

10]. According to Bill Mollison [

11], permaculture involves the intentional design and maintenance of productive human-occupied ecosystems that mirror the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems, such as forests. The primary objective of permaculture is to meet human needs while minimizing negative environmental impacts. This is achieved through integrated landscape designs that incorporate effective land and water management, infrastructure (e.g., buildings, earthworks, fencing), and community engagement.

Permaculture systems utilize a diverse array of species in complementary relationships, aiming to enhance productivity, sustainability, and multifunctionality [

11,

12].

The concept asserts that land use systems cannot be separated from social systems, highlighting the interconnectedness between ecological health and human well-being. Consequently, three core ethical principles guide the design and management of permaculture systems:

(1) Care for the Earth – Prioritizing the health of the planet and its ecosystems.

(2) Care for the People – Fostering well-being and providing for human needs.

(3) Set Limits to Consumption and Reproduction, and Redistribute Surplus – Advocating for responsible use of resources and equitable distribution.

These principles guide the sustainable development of human settlements and are central to permaculture’s approach to land use [

13] (Figure 1).

Permaculture design embraces a more comprehensive approach to understanding our environment and its resource utilization, drawing inspiration from natural systems and their applications. The primary goal of permaculture is to create a stable, self-sufficient, and easily maintained system by integrating plants, animals, and humans for productive purposes. This holistic approach seeks to establish functional relationships within the ecosystem, emphasizing sustainability and resilience.

The design process in permaculture follows a structured methodology, which includes the following steps: resource analysis, observation, reduction from nature, probabilistic planning, decision-making, random pairings, effective energy planning, and zone and sector analysis. The initial step in this process involves listing the characteristics of the system's elements, followed by the identification of useful interconnections. The aim is to ensure that each element serves multiple functions and that each key function is supported by more than one element. This phase, known as the "needs and resources analysis," establishes relationships between the inputs and outputs of various system components.

A critical aspect of this stage is a thorough understanding of each element’s features, requirements, products, and behaviors. By analyzing these factors in depth, elements can be strategically placed within the system to maximize their relationships with other components, thereby optimizing the efficiency and sustainability of the design.

Figure 1.

Permaculture ethics and design principles [

20].

Figure 1.

Permaculture ethics and design principles [

20].

In addition to the physical data of the land where the design will be implemented, decisions are informed by observations that also consider the users and their social connections. By drawing lessons from nature, the design process integrates the use of structures and their relationships with land formation and other living elements. Within this process, probabilities and decisions are made based on the interactions of the components, anticipating potential developments and changes.

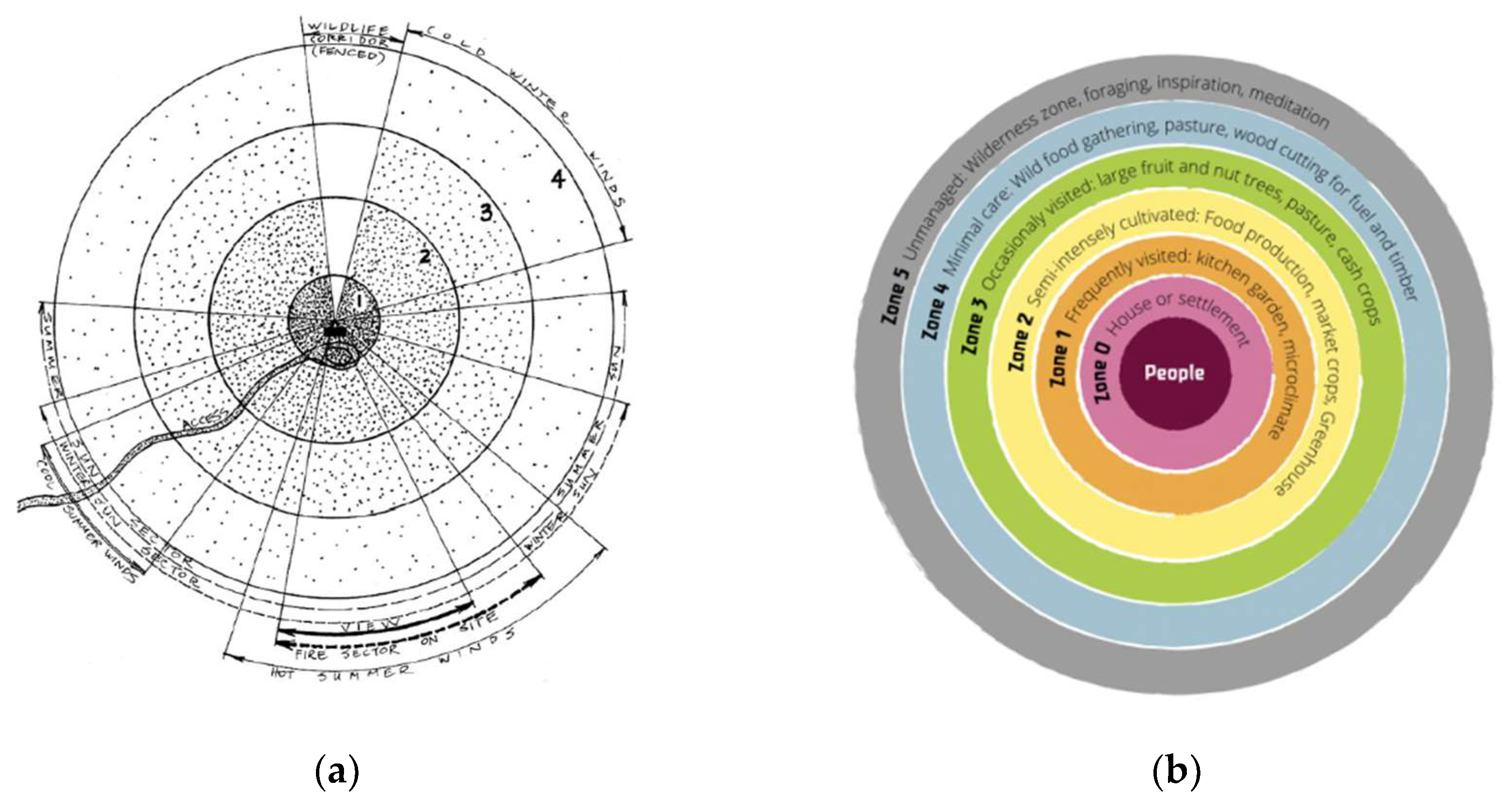

One critical step in the design process is determining the land features before positioning structures. This includes the creation of a slope map, which is essential for optimizing orientations that either offer benefit or protection, depending on wind and sunlight patterns. Based on the available data, sector and area analyses are conducted to determine the most suitable design strategies.

Sector analysis involves evaluating elements such as sunlight, wind, rain, forest fire risk, and flooding. In this context, potential hazards—including fire risks, cold or damaging winds, hot, dusty or salty winds, undesirable views, and the sun's angles during winter and summer—are identified. The analysis also considers environmental factors such as light reflection from ponds and flood-prone areas. With this data, design decisions can be made to optimize energy usage by positioning plant species and structures in alignment with the various sectors, thereby effectively harnessing natural energy resources.

Zone analysis, on the other hand, involves placing elements based on their frequency of use and the level of interaction required. Elements that are more frequently used or require constant attention are placed in zones that minimize effort and maximize accessibility. This zoning approach ensures that the design promotes efficiency and sustainability in its overall function (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(

a) Sector Analysis; (

b) Zone Analysis [

19].

Figure 2.

(

a) Sector Analysis; (

b) Zone Analysis [

19].

The role of people and human communities is central in permaculture design. Rather than focusing on individual actions, the permaculture approach emphasizes holistic decisions and practices, grounded in the collective understanding and culture of the community. It is based on the belief that all living beings within the universe are interconnected and should not be regarded as separate entities, but rather as part of a unified whole. The permaculture philosophy, by considering both the social structures and the dynamics of the communities they form, proposes that the establishment of small, responsible communities can effectively address many of humanity's challenges. This perspective has led to the development of the concept of social permaculture.

Social permaculture can be defined as the application of permaculture ethics and principles to human relations, communities, and social systems. Its aim is to foster social understanding and justice, while ensuring personal, social, and universal welfare. Through this approach, it seeks to create systems that promote harmony, sustainability, and equity within societies.

3.1. Permaculture Methods Against Climate Change

In recent years, there has been an increasing focus on the role of permaculture in mitigating the impacts of climate change, particularly in the context of agricultural activities aimed at enhancing resilience. Millison, in his study titled Permaculture Design: Tools for Climate Resilience, provides a comprehensive set of strategies addressing challenges such as drought, heat, erratic rainfall, wildfires, tropical cyclones, sea-level rise, and flooding. For instance, in the Thar Desert of Rajasthan, India, the region's extreme conditions have fostered a robust system of traditional knowledge and practices that have enabled a historically stable agricultural system. The Thar Desert, the most densely populated warm desert climate on Earth, faces severe drought conditions locally known as Trikal. These conditions, marked by a lack of grain for food, fodder for livestock, and water for domestic needs, necessitate long-term survival strategies. The community in this region has developed a Common Property Resources (CPR) Bank, which includes data banks, feed banks, firewood banks, water banks, vegetable banks, seed banks, and tree and shrub banks, providing critical resources under extreme conditions.

Another example of permaculture's role in climate resilience comes from India, where Ardhendu S. Chaterjee, the Executive Director of the Development Research Communication and Services Centre in West Bengal, devised a checklist for site-specific mitigation strategies. This checklist includes ten crucial measures:

Store water from all precipitation and surface flows.

Reduce irrigation using deep-level groundwater.

Minimize the cultivation of crops requiring frequent, intensive irrigation.

Select plant and animal species that are resilient to heat stress and intermittent droughts.

Reduce reliance on petrochemical-based inputs and fossil fuel-powered machinery, including those used for tilling, groundwater extraction, and post-harvest processing.

Combat soil erosion through both physical and biological methods.

Minimize exposed soil surfaces.

Enhance soil water retention and carbon sequestration to improve productivity and structure while reducing the need for tillage.

Diversify income sources through the use of agro-residues and byproducts.

Cultivate various tree products and encourage the presence of parasitic/pollinating insects.

In addition to groundwater recharge and improving soil capacity for water retention, reforestation plays a crucial role in stabilizing local climates and restoring the hydrologic cycle. A prominent example of this is the African Green Wall initiative, aimed at establishing a belt of trees along the southern border of the Sahara Desert to combat desertification.

Wildfire represents another critical threat exacerbated by climate change. Permaculture addresses this risk by creating firebreaks—design elements that do not support the spread of fire across landscapes. Firebreaks can include roads, irrigated gardens, crop fields, irrigated orchards, recreational lawns, concrete surfaces, grazing areas, ponds, wetlands, greywater systems, and closed-canopy hardwood forests composed of fire-resistant species. The strategy is to cluster critical infrastructure within multiple layers of fire-resistant elements to form a wide, “defensible space” that is unlikely to carry fire to the protected areas. In permaculture, the firebreak and protected areas are typically categorized into zones one, two, and three.

Planning water storage structures specifically for firefighting and fire suppression is an essential aspect of site design. This process integrates water flow as a fundamental element, upon which other design features such as access, perennial plantings, structures, and fencing are built [

14].

3.2. The Role of Permaculture in Protecting Historical Rural Landscapes Against Climate Change

This section presents a comparative analysis between the components of historical rural landscapes and permaculture design (

Table 1). The interaction between rural life and the surrounding landscape is fundamental to understanding how human activities and natural elements coalesce in a historically rooted environment. The way rural communities adapt to their geographical and environmental conditions is a reflection of an ongoing relationship with the land, deeply embedded in the cultural values of the area. This dynamic relationship between nature and human settlements contributes to the longevity of rural landscapes.

Natural areas, shaped by the geographical features of the land, have historically guided the design of buildings, agricultural spaces, and areas for animal husbandry. These natural characteristics not only define the settlement's layout but also form the basis of the cultural environments that make up the historical rural landscape. The architectural structures that emerge within this environment are directly influenced by the geography and climate of the region, ensuring that these buildings were ecologically attuned to the specific conditions at the time of construction. This adherence to local climatic and geographical data made these structures inherently ecological in nature during their period of origin.

Similarly, permaculture design also emphasizes the use of original and locally available resources, with a strong focus on creating sustainable living spaces that harmonize with the natural environment. The key principle here is the design of structures using recyclable, sustainable materials that integrate seamlessly with their surroundings. Both permaculture and historical rural landscapes prioritize the most effective use of landforms, with an understanding of how to use the topography to harness natural energy sources. The design principles of protecting from or taking advantage of wind and sun are shared by both approaches, demonstrating a common ecological foundation.

In both historical rural landscapes and permaculture, agricultural activities, farming practices, and animal husbandry are essential components that define the agricultural environment. A critical aspect of permaculture design, as well as the historic development of rural landscapes, is the careful selection of agricultural zones that are optimally positioned relative to water resources. The interdependence of soil quality, water availability, and the productive capacity of agricultural land is central to both paradigms.

Moreover, forest areas, as part of the natural environment, play a significant role in both approaches by ensuring biodiversity and safeguarding native flora and fauna. The natural environment in both scenarios is designed to foster ecological balance and sustainability.

The cultural, agricultural, and natural environments within both permaculture and historical rural landscapes are often separated by invisible borders; however, their interaction and interconnectedness remain vital for the integrity of the overall landscape. Both approaches seek to preserve the harmonious relationship between humans and the environment, fostering resilience against climate change and ensuring the continuity of traditional practices and sustainable land use.

Similarly, while culture and human cohesion are associated with intangible cultural heritage in historical rural landscapes, in permaculture design, this concept aligns with community-based human and cultural activities. In accordance with the principles of sustainable human settlement design, permaculture aims to create environments that harmonize with nature while fostering strong community structures. It places particular emphasis on cultural continuity and community-oriented living scenarios. Social relationships within permaculture are modeled after interactions observed in natural ecosystems, reflecting principles of interdependence and mutual support. Based on this approach, social permaculture can serve as a valuable tool for addressing intangible cultural heritage, facilitating the adaptation and transformation of local community knowledge and practices in response to contemporary challenges.

4. Case Study: Barbaros Rural Settlement

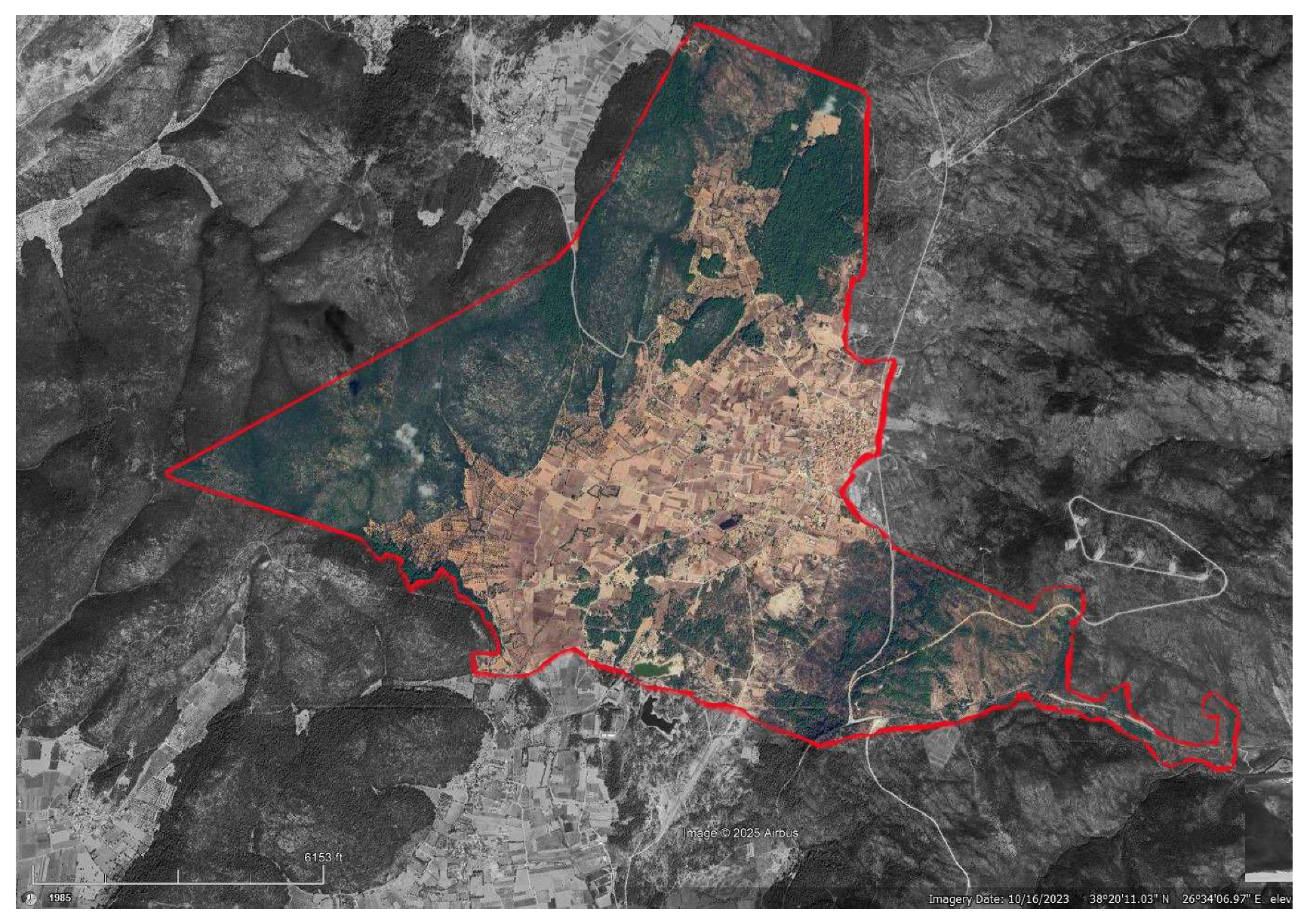

Barbaros Rural Settlement, located in the Urla District of Izmir, lies between Kadıovacık to the north, Birgi to the south, and Gülbahçe to the east. The settlement is situated approximately 20 km from Urla town center (Figure 1). The Urla Peninsula, the westernmost extension of the Aegean Region, predominantly exhibits Mediterranean climate characteristics. Summers are dry and hot, while winters are mild and rainy [

15].

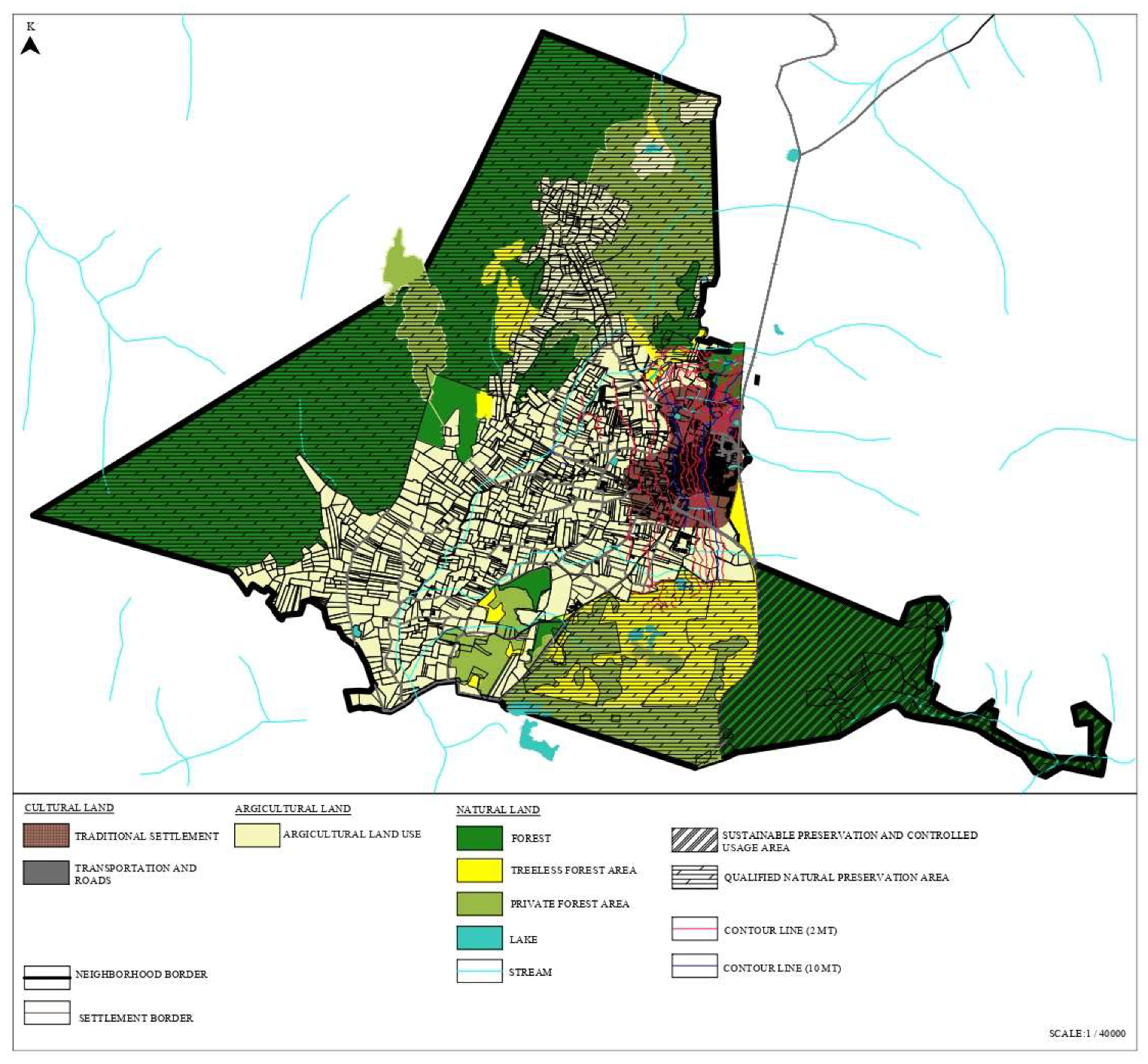

The village is established on a hillside, with a flat area surrounded by mountains, creating a natural basin. The settlement's location, chosen for its access to water resources, follows the organic contours of the land's slope. It is encircled by forested areas to the north and east, which are protected as designated natural conservation zones. These forests are subject to sustainable preservation practices and controlled usage. Agricultural lands are primarily found to the west and, especially, the south of the settlement (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Barbaros Rural Settlement location [

18].

Figure 1.

Barbaros Rural Settlement location [

18].

Figure 2.

Barbaros Rural Settlement Landuse.

Figure 2.

Barbaros Rural Settlement Landuse.

4.1. Rural Lanscapes Values of Barbaros Rural Settlement

The rural landscape values of Barbaros Rural Settlement were assessed by categorizing them into three main areas: cultural environment, agricultural environment, and natural environment.

Under the cultural environment, the key elements identified include the traditional settlement area, transportation routes, and roads.

In the agricultural environment, agricultural and farming activities as well as animal husbandry practices were highlighted.

The natural environment encompasses forested areas, lakes and lake views, unique fauna and flora species, as well as registered areas and archaeological sites (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Rural Landscapes Values of Barbaros Rural Settlement.

Figure 3.

Rural Landscapes Values of Barbaros Rural Settlement.

4.1.1. Cultural Environment

The traditional settlement area exhibits the characteristics of an organic rural settlement, with a layout that follows the natural contours of the land. There are two distinct access points to the village, one from the northeast and the other from the southwest. Barbaros Street, which originates from the northeast entrance, leads directly to the village square. In this square, you can find a variety of community-focused establishments, including coffeehouses, cafes, a grocery store, an art workshop, a village council building, and a newly built mosque (

Figure 4).

The village’s organic streets branch off from the square, with residential buildings scattered throughout. Agricultural areas, known locally as harım (vegetable gardens), are also present. Additionally, lands dedicated to animal husbandry and accommodation buildings for tourism purposes are situated within the village. Upon entering from the southwest direction, visitors encounter the Old Barbaros Mosque and the surrounding residential area, which also includes a square, contributing to the area's cohesive sense of community.

Figure 4.

Barbaros Rural Settlement Lot Usages.

Figure 4.

Barbaros Rural Settlement Lot Usages.

Figure 5.

(a) Barbaros Street; (b) Village square.

Figure 5.

(a) Barbaros Street; (b) Village square.

The traditional layout of the Barbaros rural settlement has been shaped in accordance with the region’s climatic characteristics, land structure, material resources, and traditional construction techniques. The most commonly used building materials include andesite, slate, and limestone. The nearby pine forests provided wood, while soil material was also utilized in certain areas. Notable preserved structures within the settlement include the Old Barbaros Mosque, dated 1911, as well as numerous residential buildings (

Figure 6).

These houses, which form the core of the settlement's traditional fabric, were primarily constructed to meet the sheltering needs of the inhabitants, reflecting the daily lives and routines of the community. Approximately 80% of the households feature a courtyard, surrounded by various outbuildings such as storage rooms, and animal barns. Some of these outbuildings are enclosed by stone walls and arches, adding to the unique architectural character of the area.

The houses are designed with privacy in mind, as their doors do not open directly onto the street but rather lead to the courtyards. These courtyards, in turn, are accessed through wide courtyard doors, which are typically made of iron or wood (

Figure 7).

The original houses in the Barbaros rural settlement are typically two-storey structures (

Figure 8), with external stairs in most cases (

Figure 9). The lower floor is primarily used for storage or as an animal shelter, while the upper floor serves as the living space. In addition to the main house, most courtyards feature separate structures, such as animal barns and storage rooms for goods. The bread oven and toilet are usually located outside the main house, within the courtyard area.

In these courtyards, there are also spaces dedicated to pressing grapes, storing agricultural products, and maintaining a

harım (vegetable garden), which is typically sufficient to meet the family’s needs. In contrast to the common two-storey examples, there are also single-storey houses, which consist of a single unit (

Figure 9).

4.1.2. Agricultural Environment

Agricultural activities in Barbaros Rural Settlement have significantly declined since 1965 and no longer serve as the primary economic driver of the area. In Barış Mater's book, it is noted that the soil of Barbaros Plain is slightly sloping, calcareous, and clayey red Mediterranean soil, suitable for the cultivation of grain, tobacco, anise, vineyards, olives, potatoes, and mixed vegetables. Tobacco was the dominant crop, followed by grains, with vineyards being the third major agricultural product.

Today, the remaining farms within the traditional settlement have decreased considerably, with mixed vegetable production now being the predominant agricultural activity. Olive cultivation and viticulture still persist to some extent but are no longer as widespread as in the past.

4.1.3. Natural Environment

Barbaros is notable not only for its cultural heritage but also for its rich natural heritage. The forest areas, which form a significant part of the rural landscape in terms of biodiversity and natural features, are concentrated around Barbaros Plain. Pine species and oak trees dominate the forests, contributing to the area's natural beauty and ecological diversity.

There are about 20 small ponds with depths ranging from 1-4 meters, which have existed for hundreds of years and are mostly used for animal husbandry, with surface areas ranging from 100-300 square meters around the village settlement and in the mountains. Kocagöl, with a surface area of 10 acres, is the largest. In the 1990s, about 10 ponds were built for agricultural purposes [

16]. Apart from these, there are many ponds dug by human power in the mountains, filled with rainwater and opened to meet the water needs of animals. It is said that these ponds were built thousands of years ago. Some of these ponds are Zeytincik Pond, İsmailcik Pond, Kocadağ Pond, Geri Lake, Kızıltaş Lake, Azıkaraca Lake, Sülüklü Pond, Yeni Lake, Karacaören Pond.

Barbaros Rural Settlement's natural areas, shaped by its unique geographical features, play a crucial role in its rural landscape values. These areas, with their landforms, natural beauty, vegetation, and the landscapes they create, form an essential component of the settlement's heritage. The village is located in a region where plant diversity is particularly rich. Its ecosystem, shaped by the unique climate, landforms, vegetation, animal diversity, and soil and water structure, supports a balanced and thriving environment. The forest ecosystem, dominated by tree and plant species, fosters biodiversity and vital ecological cooperation. Unlike the forest areas, the vegetation surrounding Barbaros primarily consists of Mediterranean maquis, including species such as laurel, wild boar, and various shrubs. Additionally, oleander, chaste tree, and myrtle are commonly found along the stream edges, further contributing to the area’s natural diversity.

The history of settlement of the near geography – Barbaros plain- goes back to Neolithic Age at the latest with the archaeological sites registered by İzmir 1. Numbered Cultural Heritage Conservation Board. There are four registered archaeological sites within the study area. The first is the remains of an old bathhouse and water channel found during the excavations carried out during the works to bring water to the village from the Başköy well in the early 1960s, and the two areas where Tepeüstü Mound is located. It was registered as a 1st Degree Archaelogical Site by İzmir 1. Numbered Cultural Heritage Conservation Board in July 22,1993 and the other in November 11, 2004 [

16]. The third site is Değirmen Peak and its surrounding which located in Birgi. The site was registered as 1. Degree Archaelogical Site in December 14, 2007. The last site is at Kocabağarası situs and registered as a 3rd Degree Archaeological Site in December 22, 2016. The Old Barbaros Mosque, which is within the traditional settlement area, was registered in November 23, 2011. It is in a courtyards including an old olive tree, wells and cemetery (

Figure 10).

Kocataşlar and Mintalar wells were registered as 2. Degree Immovable Cultural Asset by İzmir 1. Numbered Cultural Heritage Conservation Board in July 20, 2021 (

Figure 11). There are also “Qualified Natural Preservation Areas” and “Sustainable Preservation and Controlled Usage Areas” separated and defined within natural areas [

17].

4.2. Analysis of Climate Change-Related Effect of Landscape Values in Barbaros Rural Settlement

The climate change risk analysis for the landscape values of Barbaros Rural Settlement was conducted by categorizing the risks into three main areas: cultural environment, agricultural environment, and natural environment (

Table 2).

The first observed indicator is the increase in temperature, drought, heat waves, reduction in water levels, increased evaporation, thirst, and seasonal changes—all of which pose risks with significant impacts. The disruption of the agricultural cycle due to seasonal shifts threatens the sustainability of food production and the local economy. Limited access to water and reduced water resources negatively impact both animal husbandry and agricultural activities. Additionally, an increased likelihood of forest fires presents a severe threat to the local flora and fauna, especially to the qualified natural conservation areas and trees within sustainable preservation zones. As a result of these changes in the landscape, there will be a loss of natural values, a key component of the rural landscape.

The impact of rising temperatures is especially pronounced on traditional houses and other structures in the cultural environment. Excessive heating can lead to material degradation, particularly through salt disintegration and crumbling of stone materials. The difference between internal and external temperatures could cause structural damage. Furthermore, as water resources decrease, migration among the original inhabitants of the area may increase due to the adverse effects on agricultural activities and tourism. The rising energy demand for cooling, along with the introduction of new systems in traditional structures, will negatively affect the integrity of the cultural heritage. In terms of material deterioration, significant losses are expected in the structural components of registered archaeological sites, particularly in baths and fountains. The diminishing water resources and the drying of water wells will cause these water sources to lose their value as historical rural landscape components.

The second major indicator, wind, presents a threat to agricultural activities by accelerating soil erosion and the loss of topsoil. Strong winds also facilitate the spread of forest fires. In addition, wind and expected rainfall will damage the already dilapidated stone houses, especially within the traditional settlement areas, causing material loss and structural failure, potentially leading to complete collapse.

Invasive species, expected to rise due to climate and biological changes, will adversely affect local flora and fauna. This will significantly impact the landscape’s appearance. These invasive species, which include both plants and insects, are likely to cause serious damage to the structural and interior elements of traditional buildings, especially those containing organic materials (

Table 3).

5. Conservation Proposal

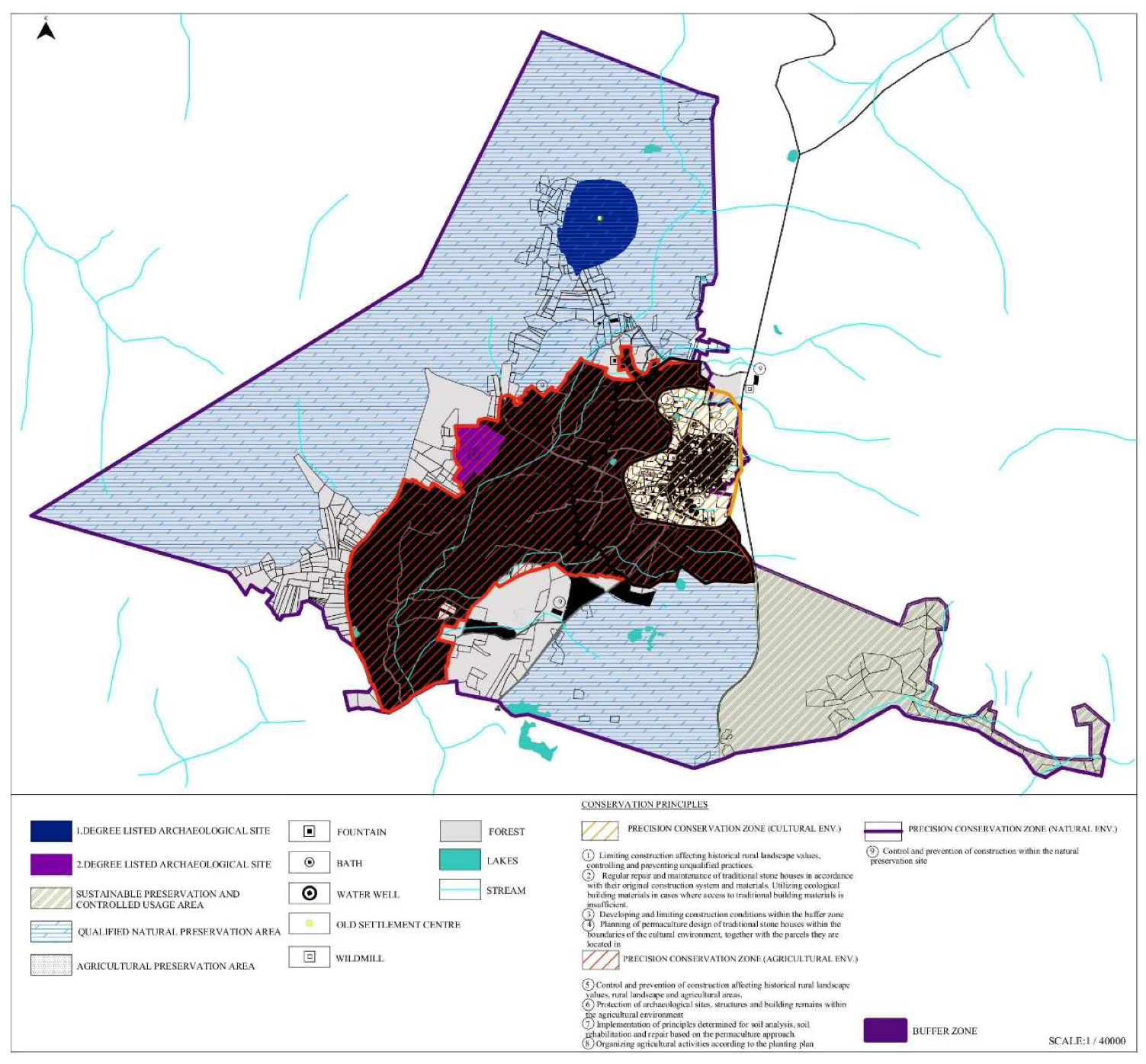

To make sustainable decisions addressing climate change impacts on the historical rural landscape values of Barbaros Rural Settlement, a set of protection principles has been developed based on the identified threats to these values (

Figure 12). These principles serve as a roadmap for determining the appropriate actions for preserving, restoring, and integrating permaculture design into the cultural, agricultural, and natural environments.

It is crucial to restore other historical structures, primarily residential buildings, within the cultural environment after a thorough assessment of structural and material deterioration caused by climate change. Preventing uncontrolled and unqualified construction activities in this environment is essential for maintaining the integrity of the area. Contemporary construction examples have been deemed suitable for inclusion within the buffer zone between the cultural and agricultural environments. Furthermore, parcels containing traditional stone housing examples have been identified for the development of permaculture designs.

In the agricultural environment, it is vital to avoid constructions that could disrupt the landscape and compromise the integrity of the area. Additionally, it is a fundamental principle to protect archaeological structures and remnants within this area from any intervention. According to the permaculture approach, steps related to soil analysis, soil rehabilitation, and restoration can be implemented as part of the secondary planning phase.

Finally, principle decisions have been made to regulate construction within the natural environment and to involve relevant institutions and organizations in managing permaculture applications.

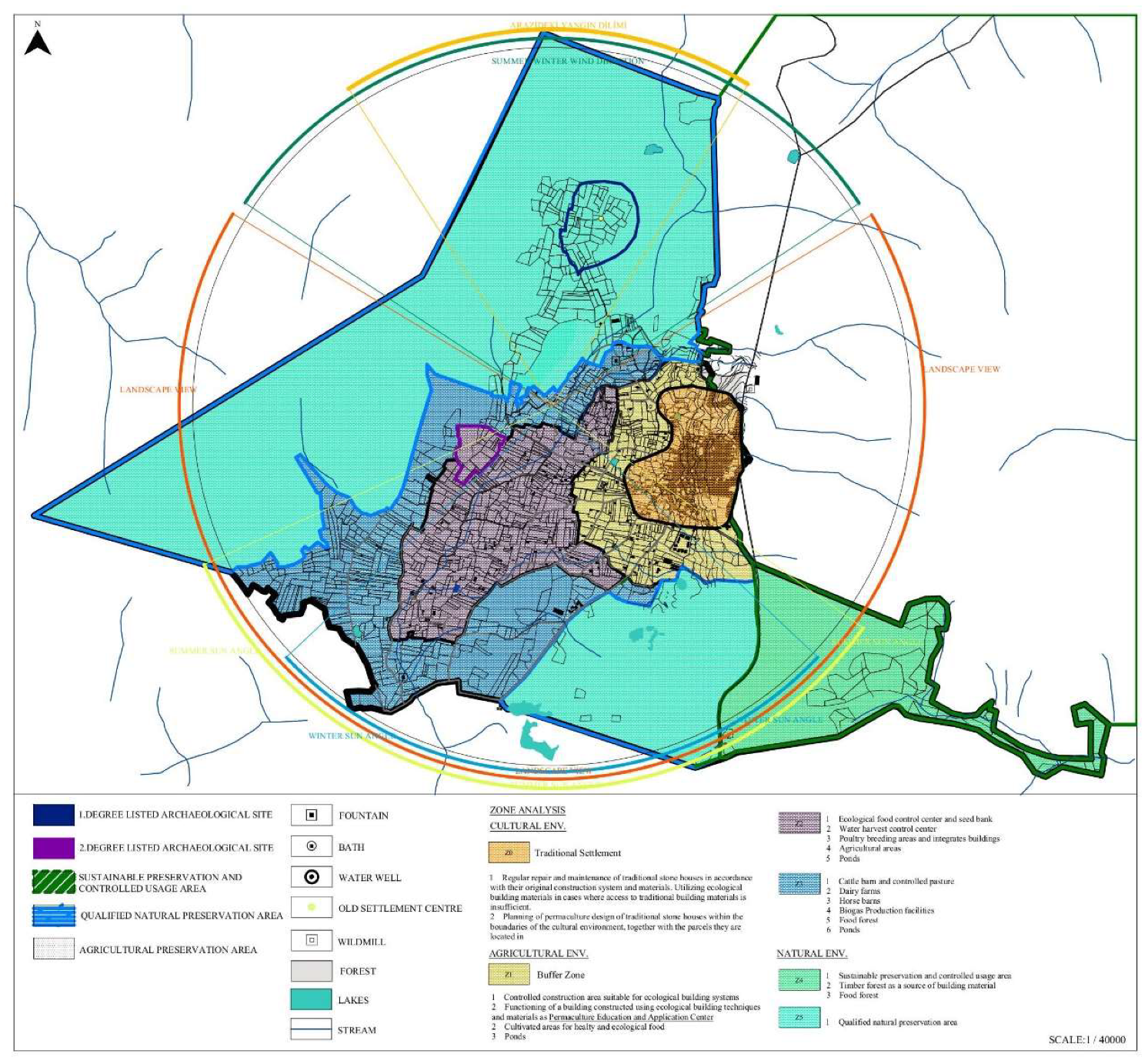

Following the established protection principles, areas designated for permaculture design were identified (

Figure 13). The design stages were developed by considering the conservation principles tailored for sensitive protection zones, as outlined in the slice analysis and zone analysis. A comprehensive map was created, incorporating winter and summer sun directions, as well as the prevailing winter and summer wind directions originating from the north, alongside landscape orientations within the sector analysis. The areas delineated through zone analysis were superimposed onto this map.

According to this analysis, Zone 0 was designated as the cultural environment boundary, defining the historical rural settlement area. The area between Zone 0 and the adjacent agricultural environment was designated as Zone 1, functioning as a buffer zone. Qualified agricultural areas forming the agricultural environment were assigned to Zone 2 and Zone 3. Sustainable preservation and controlled usage areas within the natural environment were categorized as Zone 4, while qualified natural preservation areas were designated as Zone 5.

Permaculture designs were developed for five historical stone buildings within the traditional settlement boundary of Zone 0, along with the parcels they occupy (

Table 4). In response to the existing structural issues, the following priorities were established for their restoration, ensuring alignment with the original construction techniques and materials:

Repair and reconstruction of courtyard walls in the preserved original examples.

Preservation of existing wet areas within the structures, and the addition of such areas in structures proposed for new restoration.

Repair of structural damage through appropriate reinforcement techniques.

Replacement of material losses with suitable stone, brick, or wooden elements.

Renewal and application of mortar and plaster consistent with material samples collected on-site.

Removal of non-original plasters and mortars, such as cement, which do not align with the original material composition.

Preservation of original joinery, ensuring that doors and window openings remain intact.

Reconstruction of roofs on collapsed structures, restoring them as gable roofs.

In the course of restoring these structures, it is recommended that ecological architectural techniques and materials be utilized to enhance their resilience to climate change. These suggestions focus primarily on thermal insulation:

Use of natural materials, such as hemp fiber boards or sheep wool, to establish a roof insulation layer, thereby improving the thermal performance of the buildings.

Installation of permeable insulation boards during the reconstruction of wooden floors in two-storey structures.

Addition of a thin insulation layer around door and window openings.

Application of lime mortar plaster to both internal and external walls, incorporating hemp fiber or expanded clay aggregate to enhance thermal insulation.

After the restoration of these structures, energy and field components were integrated into the permaculture design framework. Solar panels and wind turbines were added to the roofs, while rainwater harvested from the roofs was collected via rain downpipes and stored in a ground-floor water tank to facilitate water management and storage. To activate the field components, the following measures were proposed:

Planting fruit trees, particularly almond and olive, along the courtyard walls.

Introduction of a chicken system for sustainable farming practices.

Placement and planning of vegetable beds in the northwest direction.

Promotion of intensive gardening practices to increase product diversity.

Use of ecological and natural pesticides.

Cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants such as rosemary and lavender, commonly found in the settlement.

Designation of a compost area to promote waste recycling.

Referring back to

Figure 13, the techniques and methods recommended for designing new structures within the agricultural lands of Zone 1 are outlined. It is suggested that local stone be used as the primary material for the main walls, while straw or soil-based materials should be incorporated within the wooden frame system for the interior walls. The recommended floor height for these structures is one storey. Additionally, it is proposed that hemp and fiber-containing lime mortars be used for façade cladding to provide insulation, with heat insulation boards incorporated into the flooring. The integration of natural energy sources, such as solar panels or wind turbines, is encouraged, but careful planning is essential for their infrastructure. The locations of these energy sources must be selected thoughtfully to prevent any negative impact on the settlement’s landscape values.

The Zone 2 region, which predominantly consists of agricultural land, will primarily focus on local agricultural products. It is anticipated that restorative agriculture methods will be implemented in these areas. A key component of this zone’s development will be the activation of traditional water wells to enhance agricultural productivity.

In Zone 4, which is primarily dedicated to animal husbandry activities and related structures, the introduction of food forests and biogas production facilities is recommended. This zone aims to expand the timber forest area as a sustainable preservation zone, thereby contributing to the provision of building materials.

Finally, Zone 5, which corresponds to the designated natural preservation areas, is crucial for the protection of forest ecosystems. No construction activities are permitted within this region, and it is recommended that visits be limited to observation-based activities to minimize human impact on the environment.

Table 4.

Permaculture design proposals with conservation principles.

Table 4.

Permaculture design proposals with conservation principles.

6. Conclusions

Studies indicate that Barbaros Rural Settlement possesses distinct, unique historical rural landscape values, characterized by a well-preserved integrity that has enabled it to retain its authenticity while continuing to serve its local population. The settlement showcases traditional single-storey and two-storey stone houses, some of which are still standing. The surrounding areas, including qualified agricultural and forest lands, constitute a substantial portion of the settlement’s territory. The forested regions, rich in biodiversity, form a large ecosystem that hosts diverse plant and animal species. Additionally, the settlement boasts a significant wealth of water resources, including both natural and artificial lakes. Historical evidence points to a varied range of agricultural and animal husbandry activities in the area, illustrating its agricultural potential.

In light of climate change, however, analyses conducted on the landscape values of Barbaros Rural Settlement reveal threats to its cultural, agricultural, and natural environments. The settlement’s geographical features are expected to exacerbate the negative impacts of rising temperatures, desertification, and changes in seasonal weather patterns, which will likely lead to biological shifts. This study, grounded in the permaculture approach, investigates how the historical rural landscape values of Barbaros can adapt to climate change while considering the principles of conservation. In-depth analyses were carried out, focusing on specific areas, overlaying sensitive protection zones, and formulating design strategies based on comprehensive environmental assessments.

The study emphasizes the restoration of traditional stone houses and the revitalization of the surrounding landscapes within the cultural environment, aiming to create a self-sustaining, cyclical system. It also suggests revitalizing agricultural and animal husbandry activities using restorative agricultural methods, similar to the practices in the area’s historical past. These methods, including soil rehabilitation and repair, are pivotal to the sustainable recovery of the soil ecosystem. The holistic pasture method, which integrates agricultural and animal husbandry practices, and the grazing of small and large livestock before planting season, is recommended to enhance soil fertility.

Additionally, permaculture design includes strategies to increase soil water retention, the construction of open or closed water collection systems, and the management of water resources. The integration of rainwater storage for agricultural and livestock use further underscores the importance of sustainable water management. Shifting away from monoculture farming toward life-intensive gardening and increasing crop diversity will help restore the soil ecosystem, while the use of ecological and natural pesticides and the preservation of local seeds contribute to climate change adaptation.

Compost production, which enhances soil health and water retention, is identified as a necessary practice for completing the waste cycle, thereby improving agricultural productivity. To preserve forest ecosystems, new timber forests should be planted to supply sustainable building materials. These actions collectively contribute to the preservation of both the natural and cultural heritage of Barbaros Rural Settlement.

For the successful implementation of these proposals, there is a need for the development of a comprehensive legal framework for the protection of historical rural landscapes in Turkey. The authorization mechanism should be revised to incorporate new definitions. Joint studies, projects, and collaborative efforts with local governments, public institutions, and private organizations are crucial for applying these strategies, particularly in the agricultural sector. These stakeholders, as defined by the permaculture approach, play a pivotal role in supporting the revival of agriculture and animal husbandry, essential for the local population's livelihoods. Collaboration with local authorities, including muhtars, district governors, and environmental and agricultural ministries, is essential for ensuring the successful execution of these projects. Training programs for professionals—such as protection experts, architects, urban planners, and permaculture consultants—should be organized to monitor and implement the suggested agricultural and animal husbandry practices. Furthermore, community involvement and awareness are key for the successful application of these studies, with local populations actively participating in these initiatives. Educational events and cultural activities, organized in partnership with non-governmental organizations, can foster greater engagement in the process.

This study proposes a holistic, nature-compatible, and interdisciplinary protection approach that integrates permaculture principles to safeguard the landscape values of Barbaros Rural Settlement in the face of climate change risks. It offers a novel perspective for future research and practical applications in rural landscape conservation and rural heritage preservation.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICOMOS |

International Council on Monuments and Sites |

| IFLA |

International Federation of Landscape Architects |

| UNESCO |

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, AR4 Climate Change: Synthesis Report, Valencia, Spain: 2007, 30.

- Engelbrecht, F.; Willem L. A brief description of South Africa’s present day climate in the South African Risk and Vulnerability Atlas, Department of Science and Technology, Republic of South Africa: Pretoria, 2012.

- Rigyasu, J.; Managing Cultural Heritage in the Face of Climate Change, Journal of International Affairs, 2019.

- Oztekin, S.; Koskluk Kaya, N. Kuresel Iklim Krizine Karsi Tarihi Kırsal Peyzajlarin Korunmasinda Ekolojik Yaklasimlarin Rolu. Baskent University Fine Arts, Design and Architecture Faculty, 5th International Symposium of Art and Design Education, Ankara, Turkey, Date of Conference (27-28 April 2023).

- ICOMOS and IFLA. Principles Concerning Rural Landscapes as Heritage, 2017.

- Gencer, C.I.; İklim Krizi ve Kültürel Mirasın Korunması Konusunda Uluslararası Yaklaşımlar. Mimarist Journal, 2022; Volume 75, pp.36-40.

- UNESCO. World Heritage Cultural Landscapes, A Handbook For Conservation and Management. World Heritage Papers, 26. Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2009.

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2015.

- ICOMOS TR. ICOMOS Türkiye Milli Komitesi Türkiye Mimari Mirası Koruma Bildirgesi, Istanbul, 2013.

- Holmgren, D. Permaculture—Principles and Pathways beyond Sustainability; Holmgren Design Services: Victoria, Australia, 2002.

- Mollison, B. Permaculture—A Designers’ Manual; Tagari Press: Stanley, Australia, 1998.

- Ferguson, R.S.; Lovell, S.T. Permaculture for agroecology: Design, movement, practice, and worldview. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, J.; Bach S. Permaculture—Scientific Evidence of Principles for the Agroecological Design of Farming System, Sustainability, 2018.

- Millison, A.; Permaculture Design: Tools for Climate Resilience, Oregon State University, 2019; pp. 97-125.

- Mater, B.; Urla Yarımadasında Arazinin Sınıflandırılması ile Kullanılışı Arasındaki İlişkiler, İstanbul: Edebiyat Matbaası, 1982.

- Yaka, A.; Ege'de Bir Köy Barbaros Monografik Araştırma, İzmir: Hürriyet Matbaası, 2016.

- Sarıbekiroğlu, Ş.; Understanding Cultural Landscape Characteristics: The Case of Barbaros Settlement, Urla, Master’s thesis, İzmir Institute of Technology, 2017.

- Google Earth. https://earth.google.com/web / (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Santa Cruz Permaculture. https://santacruzpermaculture.com/2021/02/zone-and-sector-analysis / (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Permaculture Design Principles. https://permacultureprinciples.com/permaculture-principles/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).