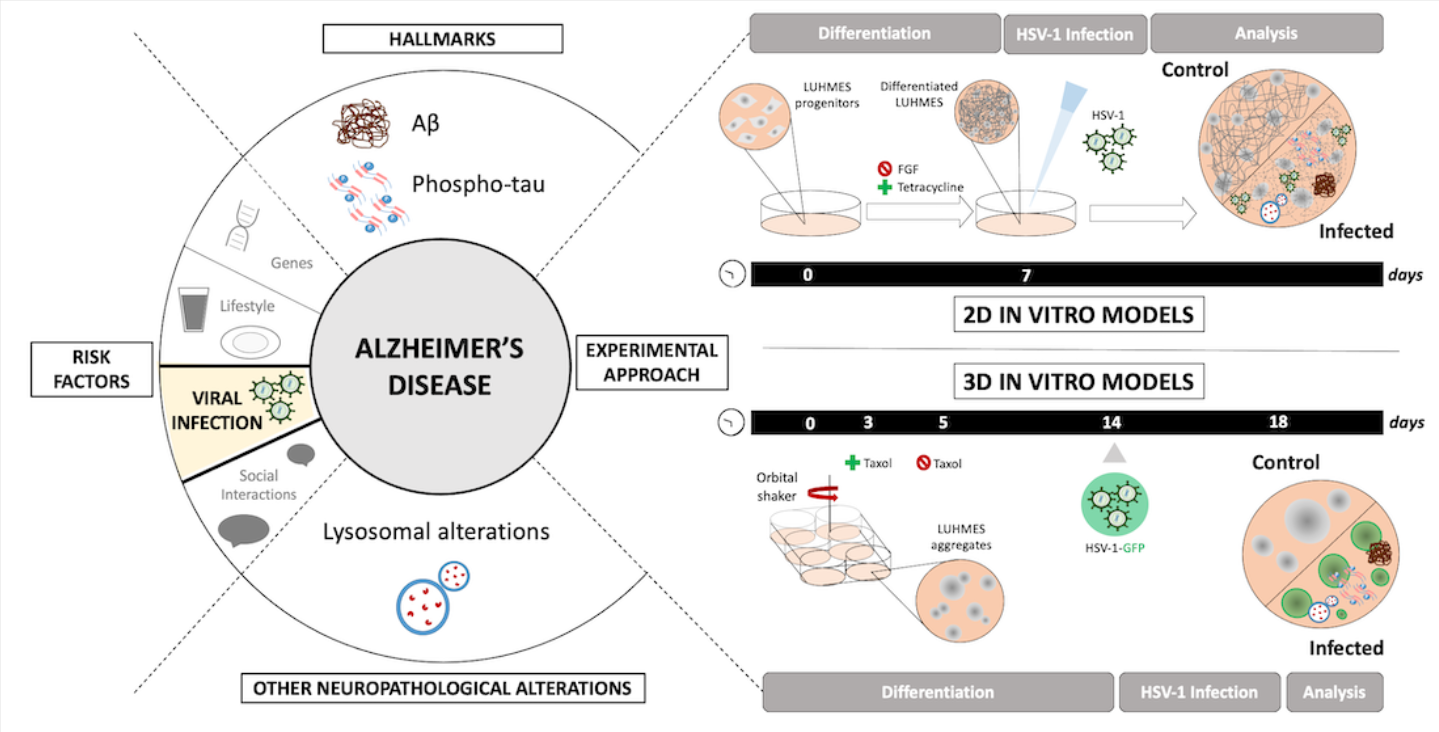

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, characterized by progressive neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment. Despite extensive research efforts, its exact etiology remains elusive, and current therapeutic strategies only provide limited symptomatic relief [

1]. Although senile plaques—primarily composed of beta-amyloid (Aβ) peptides—and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs)—formed by hyperphosphorylated tau protein—have been recognized as key features of AD for over a century, the molecular mechanisms driving the progression of the disorder are still not fully understood. Historically, the amyloid cascade hypothesis has dominated AD research, proposing that accumulation of Aβ peptides initiates a cascade of pathological events culminating in neuronal death [

2]. However, accumulating evidence suggests that multiple factors, including infectious agents, significantly contribute to the complexity and progression of AD pathology [

3].

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a highly prevalent human pathogen that infects a large proportion of the global population, typically during early life. It is primarily associated with orolabial lesions but has the capacity to infect neurons and establish lifelong latency within the peripheral nervous system, particularly in sensory ganglia. Periodic reactivation of the virus can lead to recurrent symptoms and viral shedding [

4]. Beyond its classical clinical presentations, growing evidence suggests that HSV-1 may exert long-term effects on the central nervous system (CNS). The virus is neurotropic and capable of invading the brain, where it may persist in a latent or low-grade replicative state. Reactivation or chronic infection in the CNS has been implicated in various neurological disorders, including encephalitis, and more recently, neurodegenerative diseases such as AD [

5,

6]. In this context, understanding HSV-1’s mechanisms of neuroinvasion, latency, reactivation, and the cellular pathways it disrupts—particularly in neuronal cells—is essential for elucidating its potential role in neurodegeneration.

A growing number of studies suggest a possible association between chronic HSV-1 infection and an increased risk of developing AD. Epidemiological studies have consistently identified associations between HSV-1 and a higher risk of AD, particularly among individuals carrying the APOE-ε4 allele [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Neuropathological analyses have revealed that HSV-1 DNA is frequently detected in the brains of AD patients, especially in brain regions severely affected by the disease, i.e., the hippocampus/limbic system [

11]. Furthermore, experimental studies demonstrate that HSV-1 infection can directly induce hallmark AD features, such as Aβ accumulation [

12], tau hyperphosphorylation [

13], neuroinflammation [

14] and synaptic dysfunction [

15]. However, the detailed molecular and cellular mechanisms linking HSV-1 infection to AD pathology remain to be fully elucidated.

Emerging evidence also highlights the critical involvement of the autophagy-lysosomal system in both AD pathology and viral infections [

16,

17]. In AD, impaired autophagic flux and lysosomal dysfunction lead to the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates, including Aβ and phosphorylated tau, thereby contributing to neuronal stress and degeneration [

18,

19]. Likewise, several neurotropic viruses—including HSV-1—are known to interfere with autophagy and lysosomal pathways to favor their replication and persistence within host cells [

17,

20]. Thus, disruption of the autophagy-lysosomal system represents a convergent mechanism linking HSV-1 infection to AD-like neurodegenerative processes.

Advanced cellular models capable of recapitulating key aspects of human brain physiology offer invaluable tools for investigating virus-induced neurodegenerative processes. LUHMES (Lund human mesencephalic) is a human dopaminergic neuronal progenitor cell line derived from embryonic mesencephalic precursor cells, conditionally immortalized through the integration of the

v-myc oncogene controlled by a tetracycline-regulated system. These cells exhibit a remarkable capacity for proliferation and, upon controlled suppression of the oncogene, differentiate rapidly into mature neurons that display physiological and morphological properties characteristic of the human nervous system [

21]. A key advantage of the LUHMES cellular model is its ability to maintain homogeneous and stable neuronal differentiation in long-term cultures, providing consistent cell lines for reproducible studies. This makes them particularly valuable for large-scale pharmacological screening assays and investigations into genetic and environmental factors involved in neurodegenerative diseases. Additionally, LUHMES cells are suitable for modeling neurological disorders in both two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) culture systems [

22,

23,

24], enabling the generation of models that accurately replicate the spatial and cellular complexity of the human brain environment. Furthermore, these cells have been successfully used to study the effects of infectious and toxic agents on neuronal physiology [

25,

26], thereby facilitating an understanding of the mechanisms underlying the onset and progression of CNS pathologies. To date, only a few studies have explored HSV-1 infection in LUHMES cultures, and most have focused on the establishment and maintenance of viral latency in 2D cultures [

26,

27,

28]. The effects of productive lytic infection and the consequent neurodegenerative responses have not been characterized in this model.

In this context, the present study aimed to develop and characterize a 3D LUHMES-based model of HSV-1 infection to investigate the molecular mechanisms leading to virus-induced neurodegeneration. We demonstrate that HSV-1 infection in this system reproduces AD-like alterations, including intracellular Aβ accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and lysosomal dysfunction. Collectively, these findings provide new insights into the potential role of HSV-1 in AD pathogenesis and establish a physiologically relevant neuronal platform to dissect the interplay between viral infection and neurodegeneration.

3. Discussion

AD is the most common cause of dementia and represents an increasing global health challenge. Despite extensive research, the precise mechanisms underlying AD pathogenesis remain incompletely understood, and effective disease-modifying therapies are still lacking. The growing prevalence of AD highlights the urgent need for experimental models that more faithfully reproduce the complexity of the human disease and overcome the limitations of current research systems. The present study provides significant insights into the potential link between HSV-1 infection and AD pathology, specifically emphasizing the value of LUHMES-derived neuronal models in understanding this relationship. Our results reinforce the growing body of evidence positioning HSV-1 as a meaningful environmental risk factor contributing to neurodegeneration characteristic of AD.

The LUHMES cell line, derived from human embryonic mesencephalic precursor cells, offers critical advantages for studying infection-associated neurodegeneration. These cells exhibit both proliferative and neuronal differentiation states [

21], enabling the examination of infection from initial viral entry to mature neuronal dysfunction. Their stable and homogeneous differentiation into neuron-like cells under defined conditions provides high reproducibility—an essential feature for mechanistic dissection and pharmacological screening. Another major strength of the LUHMES model is its adaptability to both 2D and 3D culture systems [

30]. While 2D cultures facilitate high-throughput exploration of viral and host responses, 3D cultures more closely reproduce the spatial organization, cell–cell communication, and microenvironmental complexity of the human brain.

The LUHMES neuronal model also provides an effective human platform for studying how neurotropic viruses disrupt neuronal homeostasis. Previous studies have demonstrated that LUHMES neurons can be efficiently infected by HSV-1, supporting both lytic and latent infection modes in 2D systems [

27,

31]. Beyond HSV-1, LUHMES progenitors and differentiated neurons are also permissive to other neurotropic viruses, including hemorrhagic fever and Zika viruses [

26], further validating the model´s versatility for studying virus–neuron interactions.

One of the main goals of this study was to establish a model of lytic HSV-1 infection in 3D LUHMES neuronal cultures. Using an orbital shaking-based method originally developed for human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)-derived neurons [

30,

32], we generated uniform spheroidal aggregates that mimic key features of neuronal architecture. The results obtained from the evaluation of various viral parameters demonstrated the ability of HSV-1 to efficiently infect different types of LUHMES cultures, including both 2D proliferative and differentiated cells, as well as 3D neuronal aggregates. First, a dose-dependent increase in the expression of viral proteins was observed. Since these proteins are expressed at distinct stages of the viral replication cycle (ICP4 is an α gene expressed at the immediate-early stage; gB is a β gene expressed during the early phase; and gC and gD are “true late” γ2 genes whose expression strictly depends on viral DNA replication), these findings suggest that the virus is capable of completing its full replication cycle in 3D aggregates. Second, qPCR analysis revealed the presence of HSV-1 DNA in the 3D neuronal cultures, confirming the replicative capacity of the virus. Finally, immunofluorescence assays detected the expression of ICP4 and the viral glycoproteins gC and gB/gD throughout the entire 3D aggregates. Collectively, these data demonstrate the ability of HSV-1 to efficiently infect and replicate in 3D cultures of LUHMES-derived neurons, underscoring the model´s potential for studying virus–induced neurodegeneration.

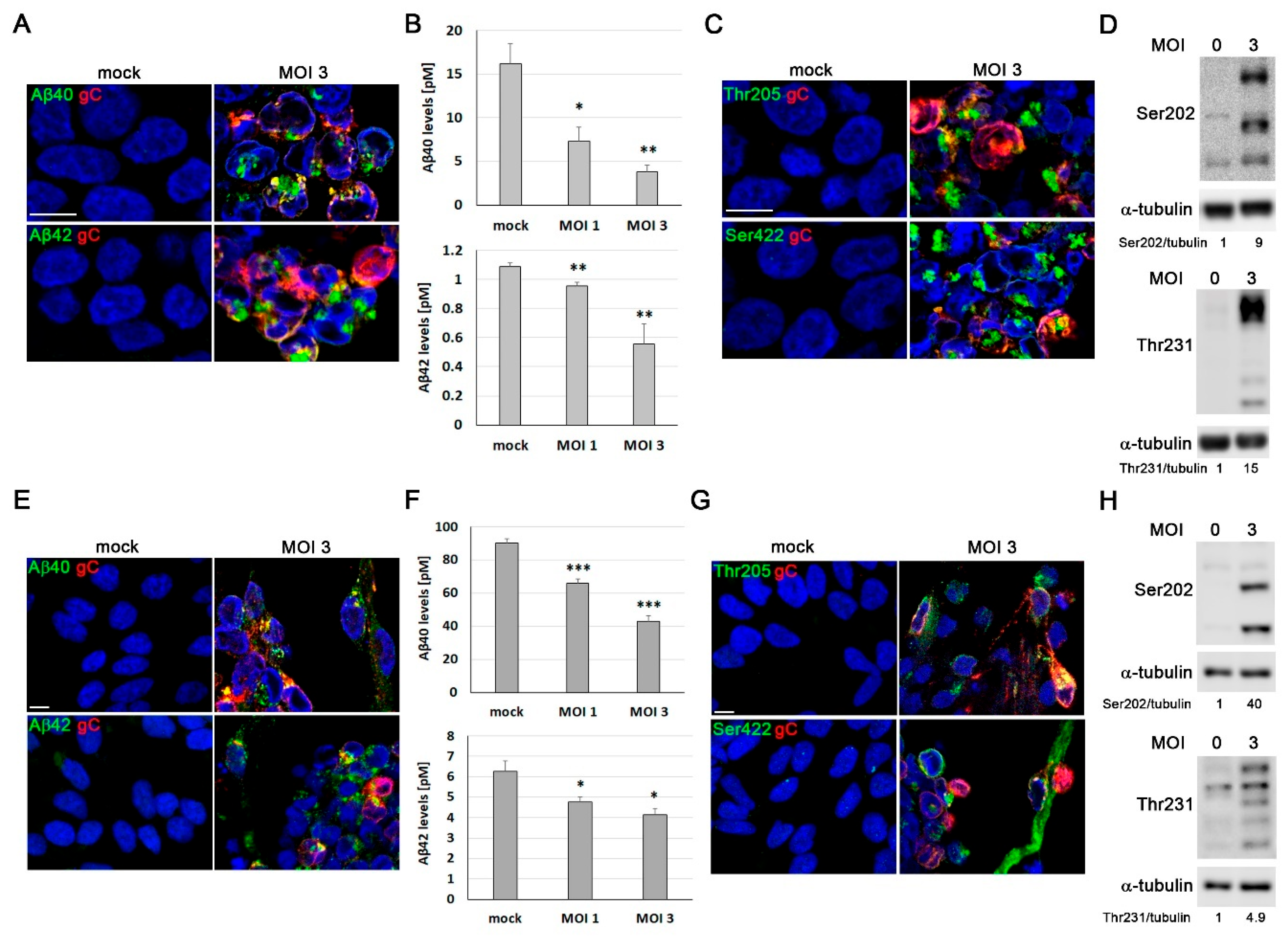

We further show that HSV-1 infection elicits hallmark AD-like alterations in proliferative and differentiated LUHMES cells across both 2D and 3D culture systems, including intracellular Aβ accumulation and robust tau hyperphosphorylation. These findings extend our previous observations in other neuronal cell systems [

12,

13,

29,

33], and strengthen the concept that HSV-1 can simultaneously disrupt Aβ metabolism and tau regulation—two central drivers of AD pathology. These observations are consistent with epidemiological studies and neuropathological analyses identifying HSV-1 DNA in brain regions significantly affected by AD [

11,

34]. The accumulation of Aβ peptides accompanied by a reduction in their extracellular secretion, suggests that HSV-1 interferes with the proteolytic processing of APP, potentially through the modulation of -, β- and γ-secretase activity. The inhibition of A secretion could underlie the intracellular accumulation of A induced by HSV-1 infection. Given the proposed antimicrobial function of Aβ [

35], this buildup may initially reflect an innate antiviral response that, if chronically activated, could contribute to neurotoxicity and plaque formation.

In parallel, the marked increase in tau phosphorylation at multiple AD-related epitopes (Ser202, Thr205, Thr231, and Ser422) highlights the ability of HSV-1 to disturb tau homeostasis. This extensive pattern of hyperphosphorylation suggests broad dysregulation of kinase activity, possibly through HSV-1-induced activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK3β), cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5), or p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK)—enzymes known to target these residues [

36]. Notably, our group previously demonstrated that inhibitors of several CDKs were able to reverse tau phosphorylation at Ser409, Ser396, and Ser404 epitopes in an HSV-1 infection model using the human neuroblastoma cell line SK-N-MC [

13], further supporting the involvement of CDK-related pathways in HSV-1–induced tau dysregulation. Similar phosphorylation profiles in both proliferative and differentiated LUHMES cells indicate that this disruption is independent of maturation stage, reflecting a generalized perturbation of tau regulation by HSV-1.

Beyond classical neuropathological markers, our results reveal HSV-1-induced impairment of autophagy-lysosome function, evidenced by LC3-II accumulation, impaired lysosomal burden, and reduced cathepsin activity. These data suggest a block in autophagosome maturation and lysosomal acidification/enzymatic function. Consistent with this, our group previously reported that HSV-1 infection in human neuroblastoma cells leads to inhibition of late stages of the autophagic process and profound dysfunction of the lysosomal pathway, reinforcing the notion that this virus profoundly interferes with cellular degradative systems [

33,

37]. Such alterations are known to occur early in AD and provide a mechanistic link between defective proteostasis, Aβ accumulation, and tau dysregulation [

19]. Thus, HSV-1 may not only mimic but also accelerate the neurodegenerative cascade through sustained impairment of cellular clearance pathways.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that HSV-1 can reproduce core AD-like pathological signatures across different stages of neuronal differentiation. The ability of the virus to modulate both APP processing and tau phosphorylation highlights its potential role as a multifactorial driver of neurodegeneration. These data support the growing body of evidence linking latent or recurrent HSV-1 infection to the molecular events underlying sporadic AD [

38,

39,

40]. Further investigation using 3D LUHMES-based cultures and single-cell transcriptomic approaches will help elucidate the cellular pathways and signaling networks through which HSV-1 contributes to neurodegenerative processes in the human brain.

To date, only a few studies have employed LUHMES cells to investigate HSV-1 infection, and most of these have focused on establishing and characterizing latent infection in conventional 2D cultures [

27,

28,

31]. Consequently, the effects of productive HSV-1 infection and its impact on neuronal integrity, protein homeostasis, and AD-like pathological hallmarks have not been explored. Although several 3D models of HSV-1 infection have been previously reported in different human neuronal systems [

41,

42,

43], to our knowledge, this work reports for the first time the establishment of a 3D LUHMES model of HSV-1 infection, which recapitulates major AD-related features in a human neuronal context. This represents a key advance toward reproducing virus-induced neurodegeneration under physiologically relevant conditions. A priority for future work in our group is to expand this system to model HSV-1 latency and reactivation. HSV-1 latency has been successfully established in 2D LUHMES neuronal cultures [

27]. Although a few studies have described latent HSV-1 infection in 3D brain organoids derived from human iPSCs [

42,

44], these models often display high complexity and heterogeneity, which may limit mechanistic analyses. To our knowledge, no 3D model of latent HSV-1 infection has yet been developed using LUHMES-derived neurons, to investigate the latent state or to evaluate how reactivation contributes to neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration. The implementation of such a 3D latency model would represent a valuable tool for elucidating the molecular mechanisms by which HSV-1 persistence leads to progressive neuronal damage and AD-related pathology.

In conclusion, our study underscores the potential of LUHMES-derived neuronal models as a translational platform to elucidate the interplay between HSV-1 infection and AD pathology. The ability to simulate key neuropathological features of AD in response to HSV-1 infection within these human-derived neuronal cells provides a powerful framework for future research. Ultimately, insights derived from these models may significantly advance our understanding of virus-induced neurodegeneration, uncover potential therapeutic targets, and guide the development of effective interventions to mitigate HSV-1-associated neurodegenerative processes.

4. Materials and Methods

LUHMES human neuronal precursor cells (BioCat GmbH) were cultured as previously described [

21]. Briefly, cells were maintained in Nunclon Delta-treated culture plates (ThermoFisher Scientific) pre-coated with 50 μg/mL poly-L-ornithine (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 μg/mL fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were cultured in proliferation medium composed of Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with GlutaMAX

TM (Gibco), 1% N2 supplement (Gibco), 50 μg/ml gentamicin and 40 ng/mL recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; R&D Systems). Cell passages were performed every 3–4 days.

Neuronal differentiation of LUHMES cultures was performed following previously established protocols [

24,

30]. For 2D differentiation, cells were switched to differentiation medium containing Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with GlutaMAX

TM, 1% N2 supplement, 50 μg/ml gentamicin and 2 μg/mL tetracycline (Sigma-Aldrich), and maintained for 7 days with medium changes every 2–3 days. For 3D differentiations, 5 x 10

5 LUHMES cells were seeded in 6-well non-treated plates (Falcon) containing differentiation medium and cultured under orbital agitation at 90 rpm (Celltron shaker system; INFORS HT). The medium was renewed every 2–3 days. To inhibit residual proliferation, taxol (10 nM; paclitaxel, Sigma-Aldrich) was added on day 3 of differentiation and removed two days later. 3D neuronal aggregates were maintained in differentiation medium for 14 days. After 7 days in 2D cultures and 14 days in 3D cultures, neuronal maturation was assessed by phase-contrast microscopy and by evaluating marker expression using RT-qPCR, Western blotting, and immunofluorescence assays.

All LUHMES cultures were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂.

- HSV-1

Infection

2D LUHMES cultures were infected with the wild-type HSV-1 strain KOS 1.1 (kindly provided by Dr. L. Carrasco) at different MOI and for various time points as indicated in each experiment. Cells were incubated in a viral solution for 1 hour at 37º C. Then, the unbound virus was removed and replaced with fresh culture medium. Cells were maintained at 37º C until their collection. Differentiated 2D cultures were infected after 7 days of differentiation.

3D LUHMES aggregates were infected after 14 days of differentiation using different viral doses and incubation times, as specified in each experiment. A fluorescent HSV-1 strain expressing GFP fused to the UL46 tegument protein (UL46-GFP) [

45] was also used in selected assays. At 18 hpi, the culture medium was replaced to remove residual extracellular virus, and samples were collected at 4 days post-infection.

Control cultures (mock) were incubated with virus-free suspensions and processed using identical procedures. Both HSV-1 strains were propagated and purified from Vero cells, as previously described [

46]. Viral titers in cell culture supernatants were determined by plaque assays as previously described [

47].

Total DNA was purified using the NZY Tissue gDNA Isolation kit (NZYtech) following the manufacturer’s instructions. HSV-1 DNA levels were quantified by real-time qPCR using a CFX-384 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad) and a custom-designed TaqMan assay targeting the US12 viral gene (forward primer: 5’-CGTACGCGATGAGATCAATAAAAGG-3’; reverse primer: 5’-GCTCCGGGTCGTGCA-3’; TaqMan probe: 5’-AGGCGGCCAGAACC-3’). Viral DNA content was normalized to the amount of human genomic DNA using a predesigned TaqMan assay for the 18S rRNA gene (Hs9999991_s1; Applied Biosystems). Data were analyzed using Bio Rad CFX maestro 2.2. software. Quantification results are expressed as the number of HSV-1 DNA copies per ng of genomic DNA.

2D cultures. Cells grown on glass coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and permeabilized with blocking solution containing 2% foetal calf serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 in phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Coverslips were then incubated with the corresponding primary antibodies followed by Alexa Fluor-coupled secondary antibodies, both diluted in blocking solution (

Table 1). Finally, nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Merck) in PBS and mounted on glass slides using Mowiol mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich). All procedures were carried out at room temperature (RT) with samples protected from light.

3D cultures. LUHMES 3D aggregates were collected in 1.5 mL tubes, and immunofluorescence analysis was performed as previously described [

30]. Briefly, aggregates were washed once with cold PBS and fixed with 2% PFA for 1 hour at 4 °C. After fixation, samples were permeabilized with blocking buffer containing 10% foetal calf serum, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.15% saponin in PBS for 1 hour at 4 °C under gentle agitation. Primary antibody incubation was performed in 4-well or 24-well plates for 96 hours at 4 °C under agitation, using antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. Then, samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor-coupled secondary antibodies for 72 hours at 4 °C under the same conditions. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI for 1 hour at RT with agitation. Finally, for sample clearing and mounting, RapiClear 1.49 (Sunjin Lab) was used. Aggregates were mounted using 0.25 mm iSpacers (Sunjin Lab) adhered to microscope slides. Aggregates were placed within the iSpacers with minimal PBS, and the chamber was filled with RapiClear 1.49 before sealing with a coverslip. Slides were left to dry overnight at RT and stored at 4 °C in the dark until imaging.

Fluorescence and confocal microscopy. Sample visualization was carried out using an inverted Axiovert 200M widefield microsope (ZEISS) coupled to a PCO edge 4.2 bi camera and a laser scanning ZEISS LSM900 confocal vertical system coupled to an Axio Imager 2 upright microscope (ZEISS). Images were acquired using 40x or 63x oil immersion objectives for cellular visualization and a 20x objective to capture complete 3D aggregates. For 3D cultures, images at 20x magnification were obtained from the central optical plane after acquiring a complete z-stack through the aggregate. Immunofluorescence images were acquired using Metamorph 7.10.5.476 or ZEN Blue 3.4 imaging software and subsequently processed with Fiji/ImageJ v1.54r and Adobe Photoshop 22.1.1.

Cell lysates were prepared by incubating samples in the radioimmunoprecipitation assay (enzymaticRIPA) buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), and 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with protease (CompleteTM Mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Roche) and phosphatase (PhosSTOPTM, Roche) inhibitors. Protein concentrations in the cell lysates were determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal amounts of protein were resolved by Laemmli discontinuous SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with either 3% BSA and 0.2% Tween 20 in PBS or 5% non-fat milk and 0.2% Tween 20 in PBS. Incubations with primary and peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies (

Table 1) were performed for 1 hour at RT. Finally, protein bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (ECL, Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Densitometric quantification of protein bands was performed using Image Lab 6.0.1 software (Bio-Rad).

mRNA expression levels were determined by RT-qPCR. Total RNA was isolated using the NZY Total RNA Isolation kit (NZYtech). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from total RNA using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems). cDNAs were amplified by PCR using primers specific for neural progenitor and neuronal genes (

Table 2). Gene expression values were normalized to β-actin, used as a reference gene due to its stable expression across experimental conditions. Real-time qPCR assays were performed in a CFX-384 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad), and data were analyzed using Bio Rad CFX maestro 2.2. software.

Conditioned media from control and HSV-1-infected samples were assayed for human Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels using commercial sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Wako), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Culture media were first collected and inactivated by ultraviolet exposure. After centrifugation, supernatants were stored at −70 °C until use. Prior to analysis, samples were concentrated by lyophilization and resuspended in PBS. An 8-fold concentration was applied for LUHMES 2D cultures and a 4-fold concentration for 3D LUHMES aggregate media. Detection was based on a colorimetric reaction generated by the anti-Aβ detection antibody, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Model 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad). Final concentrations of Aβ40 and Aβ42 were expressed as picomoles per liter (pM) of culture medium.

Lysosomal load was assessed using the acidotropic probe LTR (ThermoFisher Scientific), which freely diffuses across cell membranes and accumulates in acidic organelles. One hour before the end of the treatment period, cells were incubated with 0.5 µM LTR in culture medium for 1 hour at 37º C and subsequently washed with PBS. Cells were then lysed in RIPA buffer and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min. Protein concentration in the lysates was determined using the BCA assay. LTR fluorescence intensity in the cell lysates was measured using a FLUOstar OPTIMA microplate reader (BMG LABTECH) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 560 nm and 590 nm, respectively.

The enzymatic activity of cathepsins was determined as previously described, with minor modifications [

48]. Briefly, cells were lysed under gentle shaking in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) containing 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.2% Triton X-100. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation, and the supernatants were immediately used for the determination of proteolytic activity. A total of 25 µg (cathepsin D/E assay) or 100 µg (cathepsin S assay) of protein from each lysate was incubated for 30 minutes at 37º C with the following fluorogenic substrates (Enzo Life Sciences): Z-VVR-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Z-VVR-AMC; 20 µM), a specific substrate for cathepsin S, and Mca-GKPILFFRLK(Dnp)-D-Arg-NH₂ (10 µM), a fluorogenic substrate for cathepsins D and E. Fluorescence resulting from substrate cleavage was measured using a Spark® multimode microplate reader (Tecan) with excitation/emission wavelengths of 360/430 nm for cathepsin S substrate and 320/400 nm for the cathepsin D/E substrate.

Statistical differences between groups were analyzed pairwise using a two-tailed Student’s t-test, or a one-sample t-test when data were expressed as relative values. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***). The statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad software.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A. and M.J.B.; methodology, M.M., J.A. and M.J.B.; validation, J.A and M.J.B.; formal analysis, M.M. and J.A.; investigation, M.M., J.A., B.S., I.B. and I.S.; resources, J.A and M.J.B.; data curation, J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. and J.A.; writing—review and editing, M.M., B.S., J.A. and M.J.B.; visualization, M.M. and J.A.; supervision, J.A and M.J.B.; project administration, J.A and M.J.B.; funding acquisition, M.J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

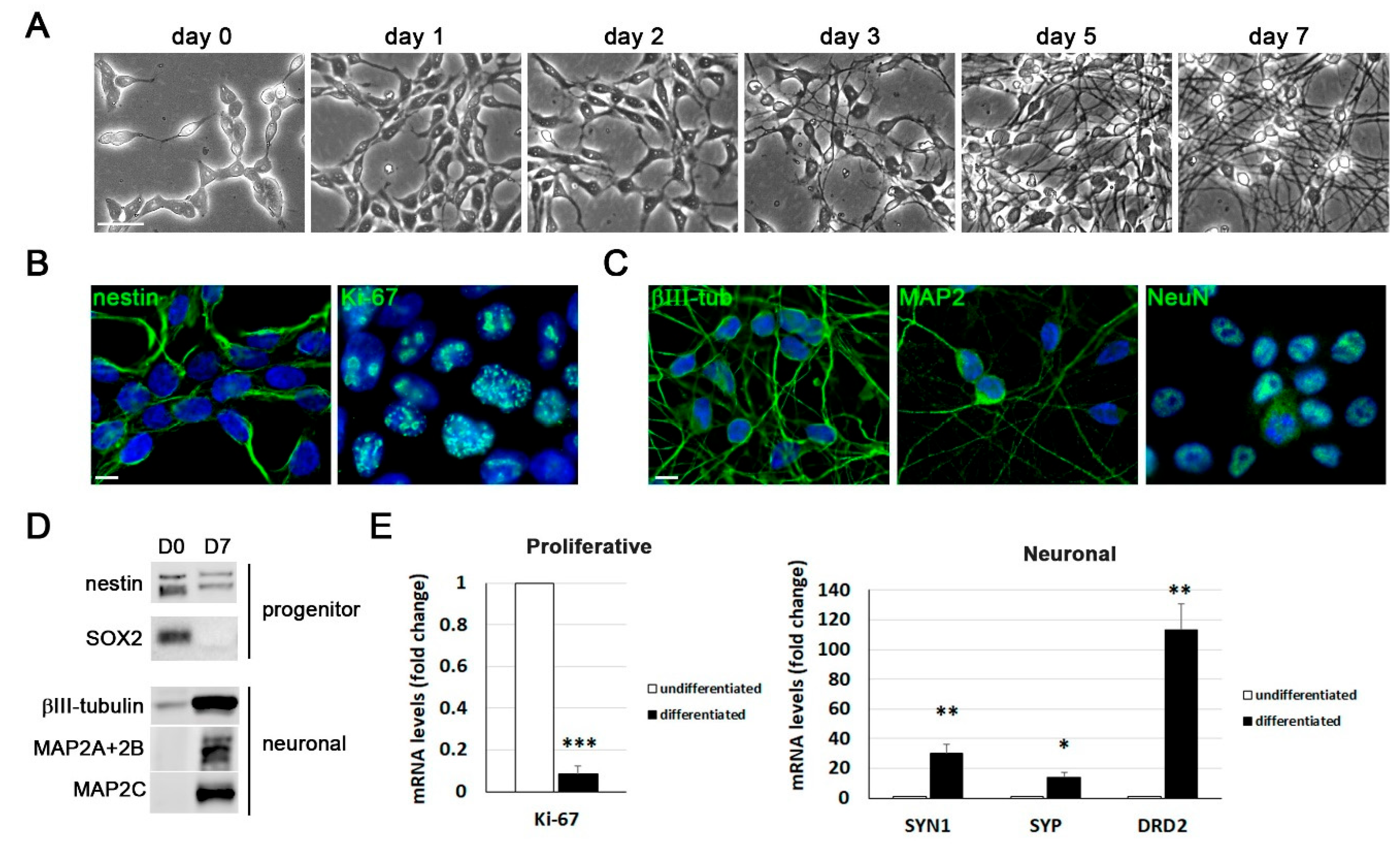

Figure 1.

Differentiation of LUHMES cells into post-mitotic neurons in 2D cultures. A) Representative phase-contrast images of LUHMES cells at different days of differentiation. Scale bar: 50 m. B) Immunofluorescence staining of the proliferation marker Ki-67 and the neural progenitor marker nestin in proliferative LUHMES cells. Scale bar: 10 µm. C) Immunofluorescence images of neuronal markers (-tubulin (III-tub), MAP2 and NeuN) in 7 day-differentiated LUHMES cells. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 m. D) Western blot analysis of neural progenitor (nestin and SOX2) and neuronal (III-tub and MAP2 isoforms) marker levels in undifferentiated (D0) and 7 day-differentiated (D7) LUHMES cells. E) Analysis of gene expression of proliferation (MKI67) and neuronal (synapsin I (SYN1), synaptophysin (SYP) and D2 dopamine receptor (DRD2)) markers by reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) in undifferentiated and 7-day differentiated cells. Graph data show the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 5 independent experiments performed in triplicate (one sample t-test; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Differentiation of LUHMES cells into post-mitotic neurons in 2D cultures. A) Representative phase-contrast images of LUHMES cells at different days of differentiation. Scale bar: 50 m. B) Immunofluorescence staining of the proliferation marker Ki-67 and the neural progenitor marker nestin in proliferative LUHMES cells. Scale bar: 10 µm. C) Immunofluorescence images of neuronal markers (-tubulin (III-tub), MAP2 and NeuN) in 7 day-differentiated LUHMES cells. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 m. D) Western blot analysis of neural progenitor (nestin and SOX2) and neuronal (III-tub and MAP2 isoforms) marker levels in undifferentiated (D0) and 7 day-differentiated (D7) LUHMES cells. E) Analysis of gene expression of proliferation (MKI67) and neuronal (synapsin I (SYN1), synaptophysin (SYP) and D2 dopamine receptor (DRD2)) markers by reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) in undifferentiated and 7-day differentiated cells. Graph data show the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 5 independent experiments performed in triplicate (one sample t-test; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

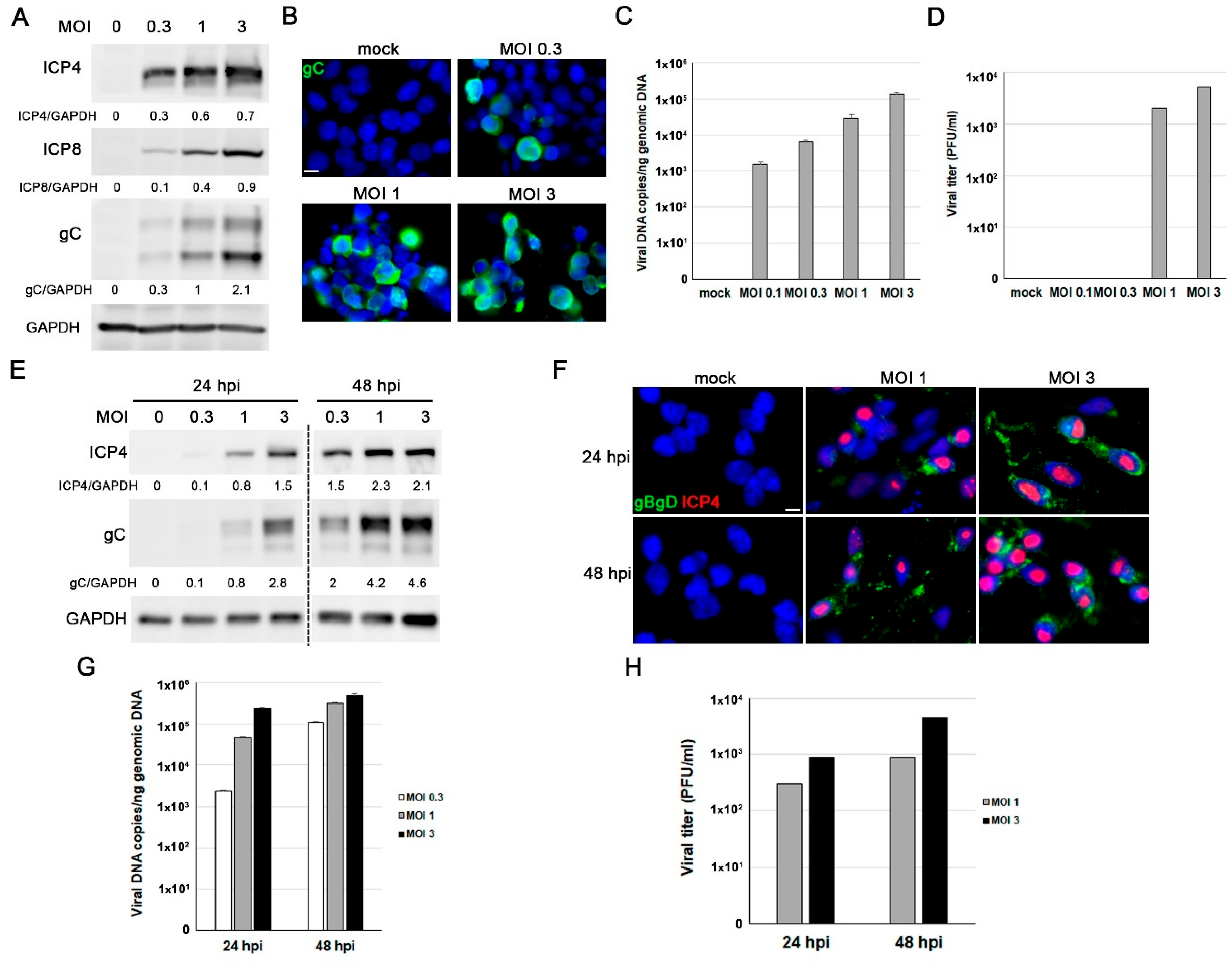

Figure 2.

Characterization of Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection in proliferative LUHMES cells and differentiated LUHMES neurons in 2D cultures. (A-D) Proliferative LUHMES cells were uninfected (mock) or infected with HSV-1 at different multiplicities of infection (MOI) for 18 hours (hpi) and the infection efficiency was monitored. A) Analysis of ICP4, ICP8 and gC viral protein levels by Western blot. A GAPDH blot to ensure equal loading is also shown. The ratio of viral proteins to GAPDH, obtained by densitometry analysis, is shown below the blots. B) Immunofluorescence images of gC viral protein. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. C) Viral DNA levels were determined by qPCR. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of two experiments performed in triplicate. D) Extracellular viral titers were determined by plaque assays. Graph shows the data of a representative experiment. (E-H) LUHMES neurons differentiated for 7 days were infected with HSV-1 at different MOI for 24 and 48 hours and the infection efficiency was evaluated. E) Western blot analysis of ICP4 and gC levels. A GAPDH blot to ensure equal loading is also shown. The ratio of viral proteins to GAPDH is shown below the blots. F) Immunofluorescence analysis using antibodies that recognize ICP4 and glycoproteins B and D. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. G) Quantification of viral DNA levels using qPCR. The data represent the mean ± SD of two experiments performed in triplicate. H) Extracellular viral titers were quantified by plaque assays. Graph shows the data of a representative experiment.

Figure 2.

Characterization of Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection in proliferative LUHMES cells and differentiated LUHMES neurons in 2D cultures. (A-D) Proliferative LUHMES cells were uninfected (mock) or infected with HSV-1 at different multiplicities of infection (MOI) for 18 hours (hpi) and the infection efficiency was monitored. A) Analysis of ICP4, ICP8 and gC viral protein levels by Western blot. A GAPDH blot to ensure equal loading is also shown. The ratio of viral proteins to GAPDH, obtained by densitometry analysis, is shown below the blots. B) Immunofluorescence images of gC viral protein. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. C) Viral DNA levels were determined by qPCR. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of two experiments performed in triplicate. D) Extracellular viral titers were determined by plaque assays. Graph shows the data of a representative experiment. (E-H) LUHMES neurons differentiated for 7 days were infected with HSV-1 at different MOI for 24 and 48 hours and the infection efficiency was evaluated. E) Western blot analysis of ICP4 and gC levels. A GAPDH blot to ensure equal loading is also shown. The ratio of viral proteins to GAPDH is shown below the blots. F) Immunofluorescence analysis using antibodies that recognize ICP4 and glycoproteins B and D. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. G) Quantification of viral DNA levels using qPCR. The data represent the mean ± SD of two experiments performed in triplicate. H) Extracellular viral titers were quantified by plaque assays. Graph shows the data of a representative experiment.

Figure 3.

HSV-1 infection induces Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-like neurodegeneration markers in LUHMES cells. (A-D) Proliferative LUHMES cells were infected with HSV-1 at MOI 1 or 3 for 18 hours and the beta-amyloid (Aβ and phosphorylated tau levels were assessed. A) Immunofluorescence analysis of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in HSV-1–infected and control cultures. Infection was monitored by gC staining. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. B) Quantification of extracellular Aβ40 and Aβ42 by ELISA. The graph data represent the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments (Student’s t-test; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01). C) Immunostaining of phosphorylated tau using the phosphorylation-sensitive antibodies Thr205 and Ser422. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. D) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated tau (Ser202 and Thr231) levels. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. Densitometry values showing the ratio of phosphorylated tau to α-tubulin is shown below the blots. (E-H) 7 day-differentiated LUHMES cells were infected with HSV-1 at MOI 1 or 3 for 24 hours and the A and phosphorylated tau levels were monitored. E) Immunofluorescence staining of A40 and A42. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 m. F) Quantitative analysis of secreted Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in conditioned medium by ELISA assays. The graph data represent the mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments (Student’s t-test; * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001). G) Tau phosphorylated levels were assessed by immunofluorescence using the phosphorylation-sensitive antibodies Thr205 and Ser422. Infected cells were stained with a gC antibody. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. H) Analysis of phosphorylated tau levels by Western blot using antibodies specific for the phosphorylated epitopes Ser202 and Thr231. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. Densitometric ratios of phosphorylated tau to α-tubulin are shown below the blots.

Figure 3.

HSV-1 infection induces Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-like neurodegeneration markers in LUHMES cells. (A-D) Proliferative LUHMES cells were infected with HSV-1 at MOI 1 or 3 for 18 hours and the beta-amyloid (Aβ and phosphorylated tau levels were assessed. A) Immunofluorescence analysis of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in HSV-1–infected and control cultures. Infection was monitored by gC staining. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. B) Quantification of extracellular Aβ40 and Aβ42 by ELISA. The graph data represent the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments (Student’s t-test; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01). C) Immunostaining of phosphorylated tau using the phosphorylation-sensitive antibodies Thr205 and Ser422. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. D) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated tau (Ser202 and Thr231) levels. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. Densitometry values showing the ratio of phosphorylated tau to α-tubulin is shown below the blots. (E-H) 7 day-differentiated LUHMES cells were infected with HSV-1 at MOI 1 or 3 for 24 hours and the A and phosphorylated tau levels were monitored. E) Immunofluorescence staining of A40 and A42. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 m. F) Quantitative analysis of secreted Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in conditioned medium by ELISA assays. The graph data represent the mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments (Student’s t-test; * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001). G) Tau phosphorylated levels were assessed by immunofluorescence using the phosphorylation-sensitive antibodies Thr205 and Ser422. Infected cells were stained with a gC antibody. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. H) Analysis of phosphorylated tau levels by Western blot using antibodies specific for the phosphorylated epitopes Ser202 and Thr231. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. Densitometric ratios of phosphorylated tau to α-tubulin are shown below the blots.

Figure 4.

Lysosomal alterations induced by HSV-1 in proliferative and differentiated LUHMES cells. (A-D) LUHMES proliferative cells were infected with HSV-1 for 18 hours. A) Immunofluorescence images of intracellular LC3 accumulation in infected cells (MOI 3) are shown. Infection was monitored by gC staining. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. B) Western blot analysis of LC3-II in LUHMES cell lysates after HSV-1 infection at different viral doses. An α-tubulin blot to ensure equal loading is also shown. The ratio of LC3-II to tubulin, obtained by densitometric analysis, is shown below the blots. C) Analysis of lysosomal load by quantification of the LysoTracker Red (LTR) fluorescence in LUHMES cells infected with HSV-1 at MOI 3. The graph data show the mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments (one sample t-test; *** p < 0.001). D) The relative enzymatic activities of cathepsins D/E and S were quantified in LUHMES cells after HSV-1 infection (MOI 3). Graph data show the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments (one sample t-test; ** p < 0.01). (E-G) LUHMES neurons, differentiated for 7 days, were infected with HSV-1 at a MOI 3 for 24 hours and lysosomal alterations were analyzed. E) Immunofluorescence images of intracellular LC3. Infection was monitored with an antibody specific for gC. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. F) Lysosomal load was determined quantifying LTR fluorescence. The graph data show the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments (one sample t-test; *** p < 0.001). G) Lysosomal activity of cathepsins D/E and S was measured. The graph data show the mean ± SEM of 6 independent experiments (one sample t-test; ** p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Lysosomal alterations induced by HSV-1 in proliferative and differentiated LUHMES cells. (A-D) LUHMES proliferative cells were infected with HSV-1 for 18 hours. A) Immunofluorescence images of intracellular LC3 accumulation in infected cells (MOI 3) are shown. Infection was monitored by gC staining. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. B) Western blot analysis of LC3-II in LUHMES cell lysates after HSV-1 infection at different viral doses. An α-tubulin blot to ensure equal loading is also shown. The ratio of LC3-II to tubulin, obtained by densitometric analysis, is shown below the blots. C) Analysis of lysosomal load by quantification of the LysoTracker Red (LTR) fluorescence in LUHMES cells infected with HSV-1 at MOI 3. The graph data show the mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments (one sample t-test; *** p < 0.001). D) The relative enzymatic activities of cathepsins D/E and S were quantified in LUHMES cells after HSV-1 infection (MOI 3). Graph data show the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments (one sample t-test; ** p < 0.01). (E-G) LUHMES neurons, differentiated for 7 days, were infected with HSV-1 at a MOI 3 for 24 hours and lysosomal alterations were analyzed. E) Immunofluorescence images of intracellular LC3. Infection was monitored with an antibody specific for gC. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. F) Lysosomal load was determined quantifying LTR fluorescence. The graph data show the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments (one sample t-test; *** p < 0.001). G) Lysosomal activity of cathepsins D/E and S was measured. The graph data show the mean ± SEM of 6 independent experiments (one sample t-test; ** p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Characterization of three-dimensional (3D) LUHMES neuronal cultures. A) The two-dimensional (2D) differentiation protocol was adapted for 3D culture by maintaining the single-cell suspension under continuous gyratory shaking. The infection with HSV-1-UL46-GFP was added at day 14 of differentiation and we process them at 96 hpi. B) Phase-contrast microscopy images of 3D LUHMES neuronal cultures at different days of differentiation. Scale bar: 200 m. C) Quantification of the diameter of 3D aggregates at days 4, 7, 10 and 14 of differentiation. Graph shows the mean ± SD of the diameter of at least 50 3D aggregates per condition. D) Immunofluorescence analysis of 3D neuronal cultures showing Ki-67–positive cells at differentiation days 4, 7, 10, and 14. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 100 μm. E) Analysis of gene expression of progenitor (MKI67) and neuronal (DRD2, SYN1 and SYP) genes by RT-qPCR in undifferentiated (day 0) and 7 and 14-day LUHMES differentiated cells. Graph data show the mean ± SD of a representative experiment performed in triplicate. F) Immunofluorescence images of 3D LUHMES cultures at differentiation days 4, 7, 10 and 14, stained with an antibody against the neural progenitor cell marker nestin. Scale bar: 100 μm. G) Immunofluorescence images showing neuronal markers (MAP2, NF200, and βIII-tub) in 14-day differentiated 3D LUHMES cultures. Higher-magnification micrographs are also shown. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bars: 100 μm (20x) and 10 μm (63x).

Figure 5.

Characterization of three-dimensional (3D) LUHMES neuronal cultures. A) The two-dimensional (2D) differentiation protocol was adapted for 3D culture by maintaining the single-cell suspension under continuous gyratory shaking. The infection with HSV-1-UL46-GFP was added at day 14 of differentiation and we process them at 96 hpi. B) Phase-contrast microscopy images of 3D LUHMES neuronal cultures at different days of differentiation. Scale bar: 200 m. C) Quantification of the diameter of 3D aggregates at days 4, 7, 10 and 14 of differentiation. Graph shows the mean ± SD of the diameter of at least 50 3D aggregates per condition. D) Immunofluorescence analysis of 3D neuronal cultures showing Ki-67–positive cells at differentiation days 4, 7, 10, and 14. DAPI-stained nuclei are also shown. Scale bar: 100 μm. E) Analysis of gene expression of progenitor (MKI67) and neuronal (DRD2, SYN1 and SYP) genes by RT-qPCR in undifferentiated (day 0) and 7 and 14-day LUHMES differentiated cells. Graph data show the mean ± SD of a representative experiment performed in triplicate. F) Immunofluorescence images of 3D LUHMES cultures at differentiation days 4, 7, 10 and 14, stained with an antibody against the neural progenitor cell marker nestin. Scale bar: 100 μm. G) Immunofluorescence images showing neuronal markers (MAP2, NF200, and βIII-tub) in 14-day differentiated 3D LUHMES cultures. Higher-magnification micrographs are also shown. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bars: 100 μm (20x) and 10 μm (63x).

Figure 6.

Analysis of HSV-1 infection in LUHMES neuronal aggregates. A) Fluorescence microscopy images of LUHMES 3D cultures infected for 24 hours with increasing doses of the fluorescent HSV-1 strain UL46-GFP. Scale bar: 200 μm. (B and C) LUHMES 3D neuronal cultures differentiated for 14 days were infected for 96 hours with increasing doses of UL46-GFP strain. B) Analysis of ICP4, UL42 and gC viral protein levels by Western blot. An α-tubulin blot to ensure equal loading is also shown. The ratio of viral proteins to α-tubulin is shown below the blots. C) Viral DNA levels were quantified by qPCR. Data represent the mean ± SD of a representative experiment performed in triplicate. D) 14 day-differentiated 3D LUHMES cultures were infected with 5 x 106 plaque forming units (PFU) of UL46-GFP strain for different time periods. Confocal microscopy images corresponding to the center of the 3D aggregates illustrate the time-dependent penetration of HSV-1 infection. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 100 μm. E) Immunofluorescence analysis using antibodies against ICP4 and viral glycoproteins B, D and C in 14 day-differentiated 3D LUHMES cultures infected with 5 x 106 PFU for 96 hours. Higher-magnification images show the nuclear localization of ICP4 and the cytosolic distribution of viral glycoproteins. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bars: 100 µm (20x) and 10 m (63x).

Figure 6.

Analysis of HSV-1 infection in LUHMES neuronal aggregates. A) Fluorescence microscopy images of LUHMES 3D cultures infected for 24 hours with increasing doses of the fluorescent HSV-1 strain UL46-GFP. Scale bar: 200 μm. (B and C) LUHMES 3D neuronal cultures differentiated for 14 days were infected for 96 hours with increasing doses of UL46-GFP strain. B) Analysis of ICP4, UL42 and gC viral protein levels by Western blot. An α-tubulin blot to ensure equal loading is also shown. The ratio of viral proteins to α-tubulin is shown below the blots. C) Viral DNA levels were quantified by qPCR. Data represent the mean ± SD of a representative experiment performed in triplicate. D) 14 day-differentiated 3D LUHMES cultures were infected with 5 x 106 plaque forming units (PFU) of UL46-GFP strain for different time periods. Confocal microscopy images corresponding to the center of the 3D aggregates illustrate the time-dependent penetration of HSV-1 infection. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 100 μm. E) Immunofluorescence analysis using antibodies against ICP4 and viral glycoproteins B, D and C in 14 day-differentiated 3D LUHMES cultures infected with 5 x 106 PFU for 96 hours. Higher-magnification images show the nuclear localization of ICP4 and the cytosolic distribution of viral glycoproteins. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bars: 100 µm (20x) and 10 m (63x).

Figure 7.

HSV-1 infection triggers Aβ accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and lysosomal dysfunction in 3D LUHMES neuronal cultures. LUHMES 3D neuronal cultures were infected with 5 x 10⁶ PFU of HSV-1 for 96 hours, and Aβ levels, tau phosphorylation, and lysosomal alterations were assessed. A) Immunofluorescence analysis of Aβ40 and Aβ42 accumulation in HSV-1–infected and control cultures. Infection was monitored by ICP4 staining. Higher-magnification images show A staining in infected cells. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. B) Quantification of extracellular Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels by ELISA. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments (Student’s t-test; * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001). C) Immunostaining of phosphorylated tau using phosphorylation-sensitive antibodies Thr205 and Ser422. Higher-magnification images show phosphorylated tau staining in infected cells. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. D) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated tau (Ser202 and Thr231) levels. An α-tubulin blot is shown as a loading control. Densitometry values showing the ratio of phosphorylated tau to α-tubulin is shown below the blots. E) Immunofluorescence images of intracellular LC3 accumulation. Infection was monitored with an antibody specific for ICP4. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. F) Lysosomal load was determined quantifying LTR fluorescence. The graph data show the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments (one sample t-test; * p < 0.05). G) Lysosomal activity of cathepsins D/E and S was measured. The graph data show the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments (one sample t-test; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

HSV-1 infection triggers Aβ accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and lysosomal dysfunction in 3D LUHMES neuronal cultures. LUHMES 3D neuronal cultures were infected with 5 x 10⁶ PFU of HSV-1 for 96 hours, and Aβ levels, tau phosphorylation, and lysosomal alterations were assessed. A) Immunofluorescence analysis of Aβ40 and Aβ42 accumulation in HSV-1–infected and control cultures. Infection was monitored by ICP4 staining. Higher-magnification images show A staining in infected cells. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. B) Quantification of extracellular Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels by ELISA. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments (Student’s t-test; * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001). C) Immunostaining of phosphorylated tau using phosphorylation-sensitive antibodies Thr205 and Ser422. Higher-magnification images show phosphorylated tau staining in infected cells. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. D) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated tau (Ser202 and Thr231) levels. An α-tubulin blot is shown as a loading control. Densitometry values showing the ratio of phosphorylated tau to α-tubulin is shown below the blots. E) Immunofluorescence images of intracellular LC3 accumulation. Infection was monitored with an antibody specific for ICP4. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. F) Lysosomal load was determined quantifying LTR fluorescence. The graph data show the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments (one sample t-test; * p < 0.05). G) Lysosomal activity of cathepsins D/E and S was measured. The graph data show the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments (one sample t-test; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

Table 1.

List of antibodies used in Western blot (WB) and immunofluorescence (IF) analysis.

Table 1.

List of antibodies used in Western blot (WB) and immunofluorescence (IF) analysis.

| Target |

Dilution |

Reference |

| WB |

IF |

| 2D |

3D |

Primary

antibodies

|

NF200 |

|

|

1:1000 |

Sigma N4142 |

| βIII-Tub |

1:10000 |

1:1000 |

1:1000 |

Abcam ab18207 |

| MAP2 (2A+2B) |

1:250 |

1:250 |

1:500 |

Sigma M 1406 |

| MAP2 (2A+2B+2C) |

1:250 |

|

|

Santa Cruz sc-74421 |

| NeuN |

|

1:250 |

|

Abcam ab104224 |

| Nestin |

1:1000 |

1:250 |

1:500 |

BioLegend 656801 |

| P-Tau Thr205 |

|

1:100 |

1:250 |

Invitrogen 44-738G |

| P-Tau Ser422 |

|

1:100 |

1:250 |

Invitrogen 44-764G |

| P-Tau Ser202 |

1:250 |

|

|

Sigma ab9674 |

| P-Tau Thr231 |

1:250 |

|

|

Invitrogen 44-746G |

| Aβ40 |

|

1:250 |

1:500 |

Invitrogen 44-348A |

| Aβ42 |

|

1:250 |

1:500 |

Invitrogen 44-344 |

| ICP4 |

1:1000 |

|

1:1000 |

Abcam ab6514 |

| ICP8 |

1:1000 |

|

|

Santa Cruz sc-51906 |

| UL42 |

1:1000 |

|

|

Santa Cruz sc-53329 |

| gC |

1:3000 |

1:1000 |

1:1000 |

Abcam ab6509 |

| gB/gD |

|

|

1:1000 |

Provided by Dr. Tabares |

| LC3/LC3-II |

1:1000 |

1:250 |

1:500 |

Sigma L7543 |

| Ki-67 |

|

1:500 |

1:500 |

Abcam ab16667 |

| SOX2 |

1:1000 |

|

|

Abcam ab79351 |

| GAPDH |

1:1000 |

|

|

Santa Cruz sc-51906 |

| ⍺-tubulin |

1:10000 |

|

|

Sigma T5168 |

| Secondary antibodies |

Anti-Mouse-POD |

1:25000 |

|

|

Vector PI-2000 |

| Anti-Rabbit-POD |

1:25000 |

|

|

Nordic GAR/IgG (H+L)/PO |

| Alexa-488 anti-mouse |

|

1:1000 |

1:500 |

ThermoFisher A-21202 |

| Alexa-555 anti-mouse |

|

1:1000 |

1:500 |

ThermoFisher A-31570 |

| Alexa-647 anti-mouse |

|

1:1000 |

1:500 |

ThermoFisher A-31571 |

| Alexa-488 anti-rabbit |

|

1:1000 |

1:500 |

ThermoFisher A-21206 |

| Alexa-555 anti-rabbit |

|

1:1000 |

1:500 |

ThermoFisher A-31572 |

| Alexa-647 anti-rabbit |

|

1:1000 |

1:500 |

ThermoFisher A-31573 |

Table 2.

List of primers used in RT-qPCR analysis of LUHMES cells differentiation. .

Table 2.

List of primers used in RT-qPCR analysis of LUHMES cells differentiation. .

| Genes* |

Forward Primer |

Reverse Primer |

| Proliferation |

MKI67 |

5′ -ATCGTCCCAGGTGGAAGAGTT-3′ |

5′ -ATAGTAACCAGGCGTCTCGTGG-3′ |

Neuronal

differentiation

|

SYN1 |

5′ -TCAGACCTTCTACCCCAATCA-3′ |

5′ -GTCCTGGAAGTCATGCTGGT-3′ |

| SYP |

5′-CGAGGTCGAGTTCGAGTA CC-3′ |

5′-AATTCGGCTGACGAGGAGTA-3′ |

| DRD2 |

5′-GCCGGGTTGGCAATGATGCA-3′ |

5′-ACGGCGAGCATCCTGAACTT-3′ |

| Reference |

ACTB |

5′ -AGTGTGACGTGGACATCCGCAAAG-3′ |

5′ -ATCCACATCTGCTGGAAGGTGGAC-3′

5′ -GTCCACCTTCCAGCAGATGTGGAT-3′ |